The English Connection

A much-loved English queen for Portugal, firm military alliances, and mutually beneficial trade have all helped cement the Anglo-Portuguese relationship over the centuries.

In 1147 a band of crusaders – English, German, French and Flemish – broke their journey in Porto en route to the Holy Land (some by choice, while others may have been shipwrecked). They were persuaded by the new king of Portugal, Afonso Henriques, to join him in an expedition to seize Lisbon from the Moors. Chronicles of the time praised the beauties of Lisbon as seen by the English crusaders. Its fertile countryside, lush with figs and vines, epitomised the seductive pleasures of the south, and encouraged many Englishmen to settle there. The first Bishop of Lisbon, Gilbert of Hastings, was English.

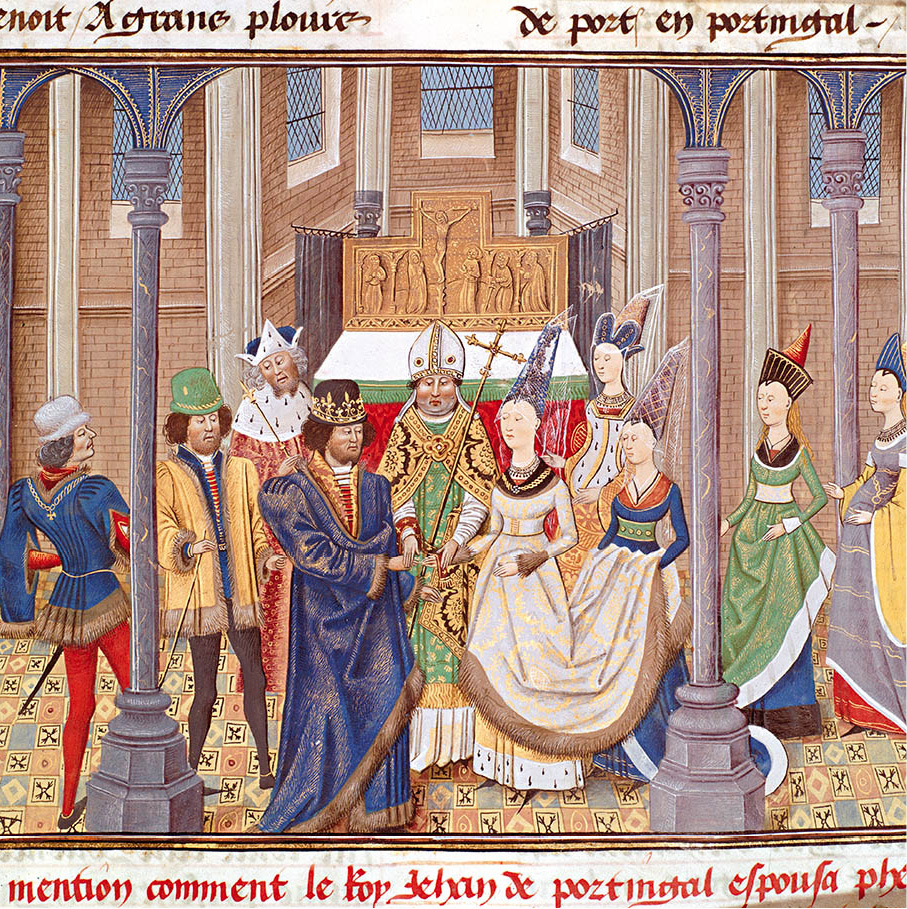

John I, King of Portugal marries Philippa of Lancaster.

Art Archive

The 17-week siege of the city ended in victory for the Christian forces, and was much celebrated. Much later it became the subject of a poem by William Mickle, the 18th-century translator of Luís de Camões (for more information, click here), who is considered Portugal’s greatest poet:

The hills and lawns to English valour given

What time the Arab Moors from Spain were driven,

Before the banners of the cross subdued,

When Lisbon’s towers were bathed in Moorish blood

By Gloster’s Lance – Romantic days that yield

Of gallant deeds a wide luxuriant field

Dear to the Muse that loves the fairy plains

Where ancient honour wild and ardent reigns.

The Portuguese themselves had less happy memories of the crusaders from the north, whom they considered a loud and drunken lot, given more to piracy than to piety. But the English, with their superior numbers and martial skills, would long feel a condescending pride in their Portuguese achievement, expecting gratitude and deference from their southern allies.

Treaties and alliances

Kingdoms were there for the taking. In 1371, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, hoped to ensure one for himself by marrying the ex-Infanta Constance, the elder of two surviving daughters of the murdered King Pedro the Cruel of Castile. Gaunt then firmly believed himself to be the rightful king of Castile. To double the family’s claim, his brother married Constance’s younger sister. But there remained one problem: the incumbent king of Castile needed to be convinced. John of Gaunt enlisted the help of Fernando of Portugal, and after rounds of courtship, lavish entertaining and the bestowal of favours, an alliance was signed in 1373 by which the two nations agreed to help one another against all enemies.

In 1385, the youthful Dom João ascended the Portuguese throne with English help, and John of Gaunt felt the time was right to go to Castile to establish his royal claims. Along with his wife Constance and two daughters – 26-year-old Philippa from his first marriage, and Katherine – a couple of his illegitimate children and an army, John of Gaunt set up court in the north, in Santiago de Compostela. He met the king and the earlier alliance was formalised as the Treaty of Windsor. In return King João was offered the hand of the devout and virtuous Philippa. They married in Porto and the city celebrated lavishly.

The English queen

Philippa was a remarkable queen. By surrounding herself in court with an English retinue, she encouraged merchants from England to come in pursuit of trade. Children were born of the marriage at regular intervals, six in all, alternately named after their English and Portuguese families. All five princes were highly gifted and excelled during their lifetimes. Henry, known later as Henry the Navigator, became the most famous of them all through his contribution to Portuguese exploration of the world. Philippa died of the plague in 1415, at the age of 51, and was mourned throughout the country.

Wellington and Sir William Carr Beresford at Salamanca in July of 1812.

Art Archive

Admired by the Portuguese, generous, kind, high-minded Philippa slowly transformed the king. João, a notorious womaniser, strayed no more and ended his days translating religious books.

Wellington rides in

Contact between these two Atlantic nations remained close. Following the period of Spanish domination of Portugal, the old alliance with England was reinstated, with Charles I (1642), Oliver Cromwell (1654) and finally by the Treaty of 1661, by which Charles II married Catherine of Bragança. Combined Anglo-Portuguese armies were not unusual: they were in action on a number of occasions, fighting each other’s battles. The most heavily recorded is the Peninsular War in the Napoleonic era. Sir Arthur Wellesley, who became the Duke of Wellington, commanded the British troops and built the famous defensive Lines of Torres Vedras, which effectively repelled the French and won the war for Portugal.

The wine trade

Throughout the history of trade between these two countries, textiles made their way to Lisbon and Porto, but there was usually wine in the hold on the return trip. During the second half of the 17th century, increasing factors of British firms settled in Viana do Castelo, Monção and Porto, and selected the wines for shipping home. Porto soon became the centre of the wine trade (for more information, click here). Names like Taylor, Croft, Cockburn, Symington, Sandeman and Graham became established, and by the 19th century these families were busy buying their own quintas (manor houses) along the banks of the Douro.

The trade in port wine flourished through wars, civil dissent and fierce regulation, and the British made a valuable contribution, especially through people like Baron Joseph James Forrester, who helped improve port safety standards, and also mapped the Rio Douro, in which he eventually drowned in 1862.

Born out of mutual need, the Anglo-Portuguese friendship has been touched by romance, passion, piety, greed, hope and despair, and yet has endured intact for almost a millennium.