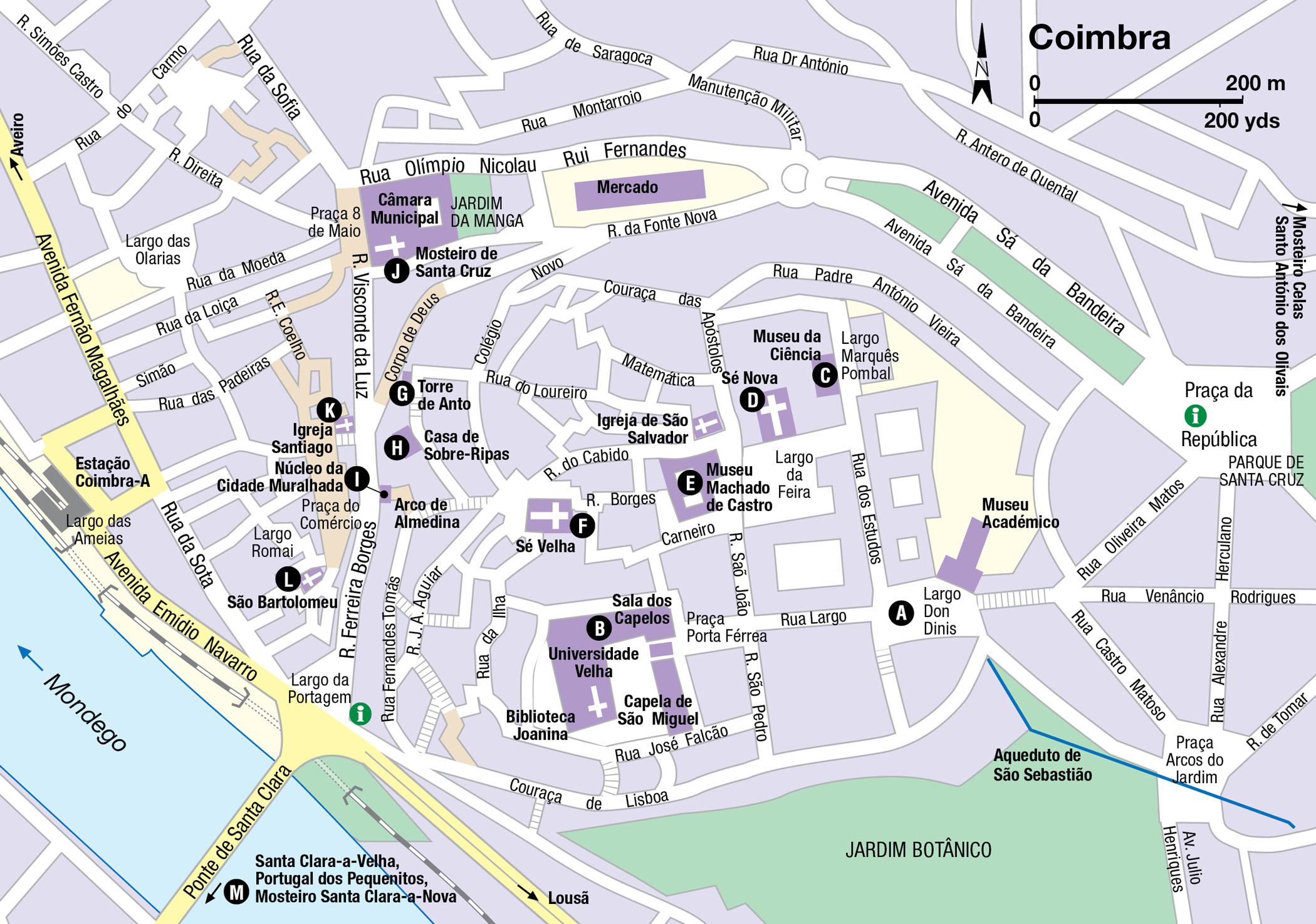

Coimbra

Coimbra grows old but never grows up. University freshers arrive each year to revitalise traditions and pour their souls into fado. For visitors it is a great mix of history and youthful exuberance.

Main Attractions

Perched on a hill overlooking the Rio Mondego, Coimbra 1 [map] is surrounded by breathtakingly beautiful countryside. The city itself is a mixture of ancient and new, rural and urban. The tourist office in the centre of the lower town, in Largo da Portagem, will provide you with a good map of the city.

The university is the most stalwart guardian of Coimbra’s colourful past. Students clad in black capes, the traditional academic dress, resemble oversized bats as they flit around town. The hems of the capes are often ripped, a declaration – at times – of romantic conquest. But these capes have only come back into style relatively recently, as for a time they were associated with Salazar’s New State, and therefore not worn in the years after the 1974 revolution.

The University of Coimbra.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

In May each year, the university celebrates the Queima das Fitas, the “burning of the ribbons”, when graduating students burn the ribbons they have been wearing, the colour of which signifies their faculty – yellow for medicine, and so on. The celebrations last a week, and their grand finale is a long drunken parade.

Another Coimbra tradition is fado, a more serious cousin of the Lisbon variety. The sombre Coimbra fado theoretically requires you to clear your throat in approval after a rendition, and not applaud. It is performed only by men, often cloak-wrapped graduates of the university.

The country’s third-largest city, Coimbra lies at the centre of an agricultural region and has a large market. The students are not the only ones in black: it is the traditional dress of many of the rural women who come into town as well. Coimbra also has a considerable manufacturing industry.

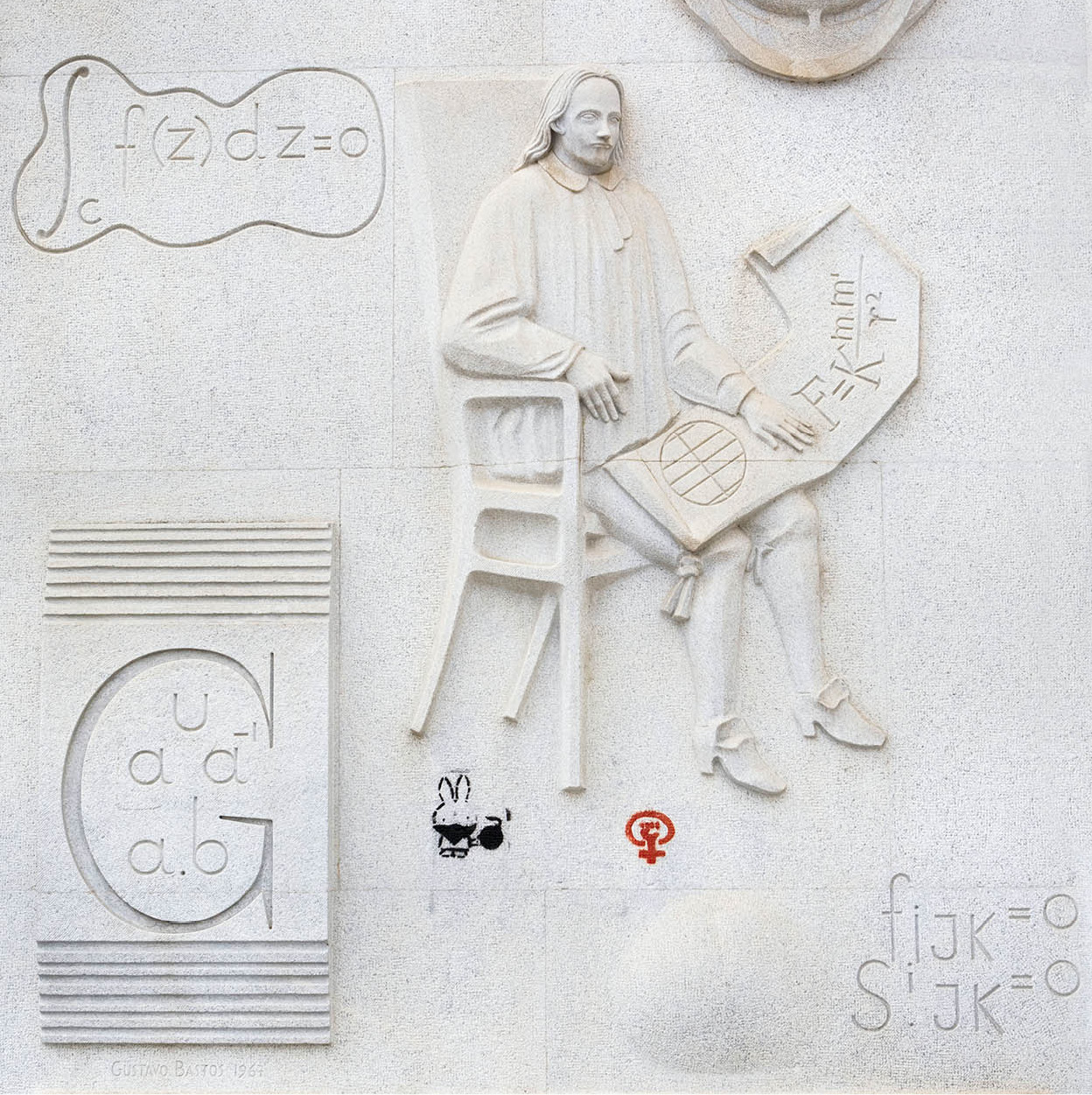

Scientific decorations at the University of Coimbra.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The city’s history

Coimbra traces its roots to the Roman municipality of Aeminium. It gained in importance when the nearby city of Conímbriga (for more information, click here) proved vulnerable to invasion. Convulsions in the empire and various invasions brought an end to Roman rule in the city. The Moors took over in 711, ushering in 300 years of Islamic rule, with a few interruptions. One such occurred in 878 when Afonso III of Asturias and León captured the city. Coimbra was not permanently retaken by Christian forces until 1064. It then became a base for the reconquest, and the city was walled. From 1139 to 1385 Coimbra was the capital of Portugal.

The 12th century was an age of considerable progress for Coimbra – including the construction, which began in 1131, of the city’s most important monastery, Santa Cruz, still standing today. A lively commercial centre, the city included both Jewish and Moorish quarters. Division was not only by religion, but also by class. Nobles and clergy lived inside the walls in the upper town, while merchants and craft workers lived outside in what is today known as the Baixa, the lower area, down by the river, and heart of the modern town.

The university, founded in 1290 in Lisbon, moved to Coimbra in 1308, only to return to Lisbon nearly 70 years later. It was not until 1537 that the university settled permanently in Coimbra. A few years later, it moved to its present site at the top of the hill.

Most areas of interest are easily reached on foot. There is also a handy elevator which rises from Avenida Sá da Bandeira to Rua Padre António Vieira. Don’t try to drive within the city. The old city and the university crown Coimbra’s central hill, and the Baixa, which is the main shopping and eating district, lies at the foot of the hill along the Rio Mondego. Santa Clara lies across the river, while the tourist office, Turismo, is conveniently located at the northern end of the road bridge. Linking the two banks of the river, too, is a hi-tech footbridge with bright zigzag railings, and there are plenty of picturesque riverside restaurants.

A mosaic welcomes you to the university at Coimbra.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The old city and university

Once enclosed within walls, the old city is a tangle of narrow streets and alleys, lined by ancient buildings and filled with squares and patios. The university buildings are a compelling mix of styles, from the odd Baroque Torre, a clocktower, to bleakly Salazarist faculty blocks. The modern centre of the university is the statue of King Dinis, its founder, on the site of an earlier castle in Largo Don Dinis A [map], also home to the Museu Académico (Academic Museum; Mon–Fri 10am–12.30pm, 2–5pm), where the displays include historic university capes and posters. Nearby stand the buildings that house the faculties of science and technology, medicine and letters and the New Library.

Of more historical interest than these stolidly functional buildings is the Pátio das Escolas (Patio of the Schools), within the Universidade Velha B [map], the Old University. To enter the patio, pass through the 17th-century Porta Férrea, a large portal decorated in the Mannerist style, to a large, dusty courtyard that is used for parking. Here are some of the oldest and stateliest buildings of the university. The figure of João III, who installed the university in Coimbra, still reigns from the centre of the patio. Behind him, there is a magnificent view of the river.

Fact

Trains from Lisbon (Oriente) take 1.5–2 hours and stop at Coimbra B station 3km (2 miles) north of the centre, where passengers take a linking train to Coimbra A, the delightful little station in the middle of town. You don’t need a separate ticket.

The building in the furthest corner from the Porta Férrea is the Biblioteca Joanina (daily Mar–Oct 9am–7.30pm, Nov–Feb 9.30am–1pm, 2–5.30pm), among the world’s most resplendent Baroque libraries. The three sumptuous 18th-century rooms were built during the reign of João V, whose portrait hangs at the far end. Bookcases, decorated in gilded wood and oriental motifs, reach gracefully to an upper galleried level; even the ladders are intricately decorated. Note the fine frescoes on the ceilings. More than 300,000 books fill the cases and are still consulted by scholars.

Museu da Ciência

Several small university museums were merged to form the impressive Museu da Ciência C [map] (Science Museum; www.museudaciencia.pt; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), located in Largo Marquês de Pombal. One of Europe’s most important science collection, this award-winning museum has some 250,000 objects on display. Categories include botany, mineralogy, geology, palaeontology, astronomy and medicine, with information provided in both English and Portuguese.

This museum is a great choice for families as there are plenty of child-friendly interactive displays, including the key “Secrets of Light and Matter”, and some fascinating visual exhibits, such as a bed of flowers seen from the perspective of a bug-eyed insect.

Next door is the Capela de São Miguel (St Michael’s Chapel), begun in 1517, and remodelled in the 17th and 18th centuries. The chapel is notable for its carpet-style tiles, the painted ceilings, the altar and the Baroque organ. Beside the chapel is a small museum of sacred art.

The arcaded building to the right of the Porta Férrea on the Via Latina houses the Sala Grande dos Actos (Mon–Fri 9am–1pm, 2–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 10.30am–4.30pm), where degrees are conferred and academic ceremonies take place. Portraits of Portugal’s kings hang from its walls. Other rooms that you may enter are the rectory and, right by the bell tower, the Sala do Exame Privado, the Private Exam Room.

The Old Cathedral of Coimbra, built in the 12th century.

Mark Read/Apa Publications

Old and New cathedrals

A short walk down from the university takes you to the Sé Nova D [map] (New Cathedral; Mon–Sat 9am–6.30, Sun 10am-12.30pm; free), whose sand-coloured facade presides over a rather uninteresting square. Built for the Jesuits in 1554, it became a cathedral in 1772. Inside, the altar and much else is of lavishly gilded wood. Many of the paintings around the altar are copies of works by Italian masters.

Museu Machado de Castro.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The Museu Machado de Castro E [map] (daily Apr–Sept 10am–6pm, Oct–Mar 10am–12.30pm, 2–6pm) is housed in the old Episcopal palace and the neighbouring 12th-century church of São João de Almedina. Constructed over the city’s Roman forum and cryptoporticus (underground galleries), the palace was the residence of Coimbra’s early bishops. The museum is named after Portugal’s greatest sculptor Joaquim Machado de Castro (1732–1822), who was born in Coimbra. It holds an extensive and varied collection of medieval sculpture, as well as superb later pieces.

The Sé Velha F [map] (Old Cathedral; Sun–Thu 10am–6pm, Fri 10am–4pm; free except for the cloisters), renovated in the 20th century, was built between 1162 and 1184. It served as a cathedral until 1772, when the episcopal see was moved to the Sé Nova. The fortress-like exterior is relieved by an arched door with an arched window directly above. The intricate Gothic altar within is of gilded wood, created by two Flemish masters in the 15th and 16th centuries. Sancho I was crowned king here in 1185, and João I in 1385. There are several tombs in the cathedral, including those of the 13th-century Bishop Dom Egas Fafe (to the left of the altar) and Dona Vetaça, a Byzantine princess who was a governess in the Coimbra court in the 14th century. Construction of the early Gothic cloister began in 1218.

Work on the Colégio de Santo Agostinho, on Rua Colégio Novo, was started in 1593. The ecclesiastical scholars and monks who first occupied it would probably be astonished by its present-day purpose, for this pleasant building, lined with pretty azulejos, is now home to the university’s Psychology Department.

Nearby, on Rua Sobre-Ripas, the medieval Torre de Anto G [map] (Anthony’s Tower) was once part of the 12th-century city walls. Much later it was the home of the poet António Nobre (1867–1900) during his days as an undergraduate student.

The Casa de Sobre-Ripas H [map], on the same street, is an aristocratic 16th-century mansion. Note the archetypal Manueline door and window, but don’t bother knocking: it is the Faculty of Archaeology, and not open to the public. Here, it is believed, Maria Teles was murdered by her husband João (eldest son of the tragic Inês de Castro) who had been convinced by the jealous Queen Leonor Teles that his wife – the queen’s sister – was unfaithful to him.

The Arco de Almedina, an entrance to the old city just off Rua Ferreira Borges, was also part of the medieval walls that encircle the old town hill. Housed in the tower here is the Núcleo da Cidade Muralhada I [map] (Tue–Sat 10am–1pm, 2–6pm), a model display of the town with its original town plan and defensive towers, plus details of its history. Head upstairs for superb views and to spy down through the holes carved into the stone floor. In times of war or invasion, boiling oil was poured through these holes to thwart potential aggressors.

The Baixa is the busy shopping district, and Rua Ferreira Borges, with many fashionable shops, is the busy, principal street. Although this district lay outside the walls of the old city, it dates back to almost the same time.

The Mosteiro de Santa Cruz J [map] (Tue–Fri 9am–5pm, Sat 9am–noon, 2–5pm, Sun 4–5.30pm; free) in Praça 8 de Maio (a continuation of Rua Ferreira Borges) was founded in 1131 by the St Augustine fathers. In the 14th century a grim scene was enacted when Dom Pedro had the body of his murdered lover exhumed, crowned and propped on a throne here, forcing his courtiers to pay homage to her corpse and kiss her decomposing hand. The facade and portal of the church date from the 16th century. Inside, the small church is light and spacious. Eighteenth-century azulejos adorn the walls: the right side depicts the life of St Augustine of Hippo; on the left, scenes relate to the Holy Cross.

Another striking work by a major 16th-century artist is the exquisite pulpit on the left-hand wall, by sculptor Nicolau Chanterène. The sacristy (charge) contains several interesting paintings including The Pentecost by the 16th-century Grão Vasco, a silverwork collection, and some clerical vestments. You can see the tombs of the first two kings of Portugal, Afonso Henriques and Sancho I, ensconced in regal monuments. The chapterhouse and the lovely Cloister of Silence may also be visited.

Behind the church of Santa Cruz lies the Jardim da Manga (Garden of the Sleeve), so named because Dom João III reputedly drew this oddity of a garden on his sleeve – although the design has also been attributed to João de Ruão, a French sculptor working in Portugal in the 16th century. Curiously modernistic, this monumental garden was completed in 1535, and intended as a representation of the fountain of life. Beside the church is an atmospheric café in an ecclesiastic setting that was clearly part of the church.

If you wander down Rua da Sofia, which turns off 16th-century Praça 8 de Maio, you may be struck by the fact that it is extraordinarily wide for a street of that period. It was the original base for several colleges of the university before they were moved to new homes.

Praça do Comércio, off Rua Ferreira Borges, is an oddly shaped square lined with 17th- and 18th-century buildings. At the north end stands the sturdy Igreja Santiago K [map], a church dating from the end of the 12th century. The capitals are decorated with animal and bird motifs. At the square’s south end is the Igreja de São Bartolomeu L [map], built in the 18th century.

Tip

To find the boisterous student nightlife, head for the restaurants around Rua la Sota, one street back from the river in Baixa Coimbra. And try the chanfana – goat stewed in wine – a dish from the Beira Litoral, to the north.

Exploring Portugal dos Pequeninos.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Santa Clara

The Santa Clara section of town lies across the river. Mosteiro Santa Clara-a-Nova M [map] (New Santa Clara Monastery; Tue–Sun winter 9am–5pm, summer 9am–6.30pm) is worth a visit if only for the view over Coimbra. Inside is the tomb of Queen Isabel, who was canonised in 1625 and became the city’s patron saint. Closer to the river, too close for its own comfort in fact, is Santa Clara-a-Velha, the old Santa Clara Monastery. This 12th-century edifice is simpler and more lovely than its replacement, for which it was abandoned in 1677. Waterlogged for centuries, it has been successfully restored.

Nearby Quinta da Lágrimas is where Inês de Castro is believed to have been murdered (for more information, click here). The family home is now a luxurious hotel and the grounds contain the Fonte das Lágrimas, the spring which is said to have risen on the spot where the luckless Inês cried for the last time and met her violent end.

To the east of the city, the Mosteiro Celas is notable for its cloister, and the pretty church of Santo António dos Olivais was once an old Franciscan convent.

Shops, parks and boats

The lanes of the Baixa have some delightfully old-fashioned shops. The covered market on Rua Olimpio Nicolau is open daily.

Coimbra has numerous parks: the Jardim Botânico (Botanical Garden, Apr–Sept Tue–Fri 9am–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 2–8pm; Oct–Mar Tue–Fri 9am–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 11am–5.30pm; free except for greenhouses), on Alameda Dr Júlio Henriques, next to the 16th-century Aqueduto de São Sebastião, is a lovely garden, laid out in the 18th century.

The Portugal dos Pequeninos (www.portugaldospequenitos.pt) is an outdoor theme park displaying small-scale reproductions of traditional Portuguese houses and monuments, which children love to clamber over and explore.

Other parks are Santa Cruz, off Praça da República, and Choupal, west of the city – a larger green space that is good for walks and bicycle rides. Tiny Penedo da Saudade has a nice view.

If you want some physical exercise, and a complete change from historical monuments, there are canoes and pedaloes for hire on the river. Basófias (Tue–Sun) offer river cruises lasting an hour.

A stroll in the Jardim Botânico.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Hotel Buçaco Palace.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications