Revolution and Evolution

Republicanism failed to restore Portugal’s former glory. Political turmoil followed by dictatorship hindered growth and modernisation until the 1980s.

The end of the 19th century saw Portugal’s finances in complete disarray. The havoc wrought by the Peninsular and Miguelist wars, on top of the loss of Brazil, was insurmountable. In 1889, Carlos I became king, setting African expansion as his primary goal, but his efforts were unsuccessful. In 1892, Portugal declared bankruptcy.

Still dreaming of restoring the empire, Carlos could do little to defuse the growing anti-monarchical sentiment. Socialism and trade unionism were growing influences. The legislative cortes had degenerated into a powerless assembly full of obstructive and self-promoting debate. Corruption and inefficiency were rampant.

In 1906, struggling to maintain some form of control, Carlos appointed João Franco as prime minister, endowing him with dictatorial powers. He quickly dissolved the useless legislature. In 1908 unknown parties, either members of a republican secret society or isolated anti-monarchical fanatics, assassinated Carlos and his son, Luís Filipe, heir to the throne. In the assault on the royal carriage, Manuel, the king’s second son, was wounded but survived.

Over the next two years Manuel II tried to save the monarchy, offering various concessions, but the assassination had fortified the republican movement. The long-decrepit House of Bragança finally crumbled to dust.

An allegory of the 1908 elections.

Museu da Marinha, Belem

The rise of republicanism

The rising tide of republicanism could not be stopped. The democratic ideal was combined with a nationalistic vision, a shift it was hoped would return Portugal to its long-lost glory. The national anthem adopted in 1910 echoed the theme: “Oh sea heroes, oh noble people… raise again the splendour of Portugal… may Europe claim to all the world that Portugal is not dead!”

The assassination of Carlos sealed the victory of republicanism, but it took time for the various parties and coalitions to sort themselves into a workable government – practically speaking, they never did. Between 1910 and 1926 there were 45 different governments, with most of the changes brought about by military intervention rather than parliamentary procedures. The early leadership pressed their radical anti-Church and social reforms too hard, causing a reaction that revived the influence of the Catholic Church. Labour movements sprang up with the best intentions, but often paralysed industry. First and foremost, the republicans were unable to deliver promised financial reforms and stability, both through their own ineptitude and, later, because of the international depression of the 1920s. It was their economic failure that most significantly eroded their popular support.

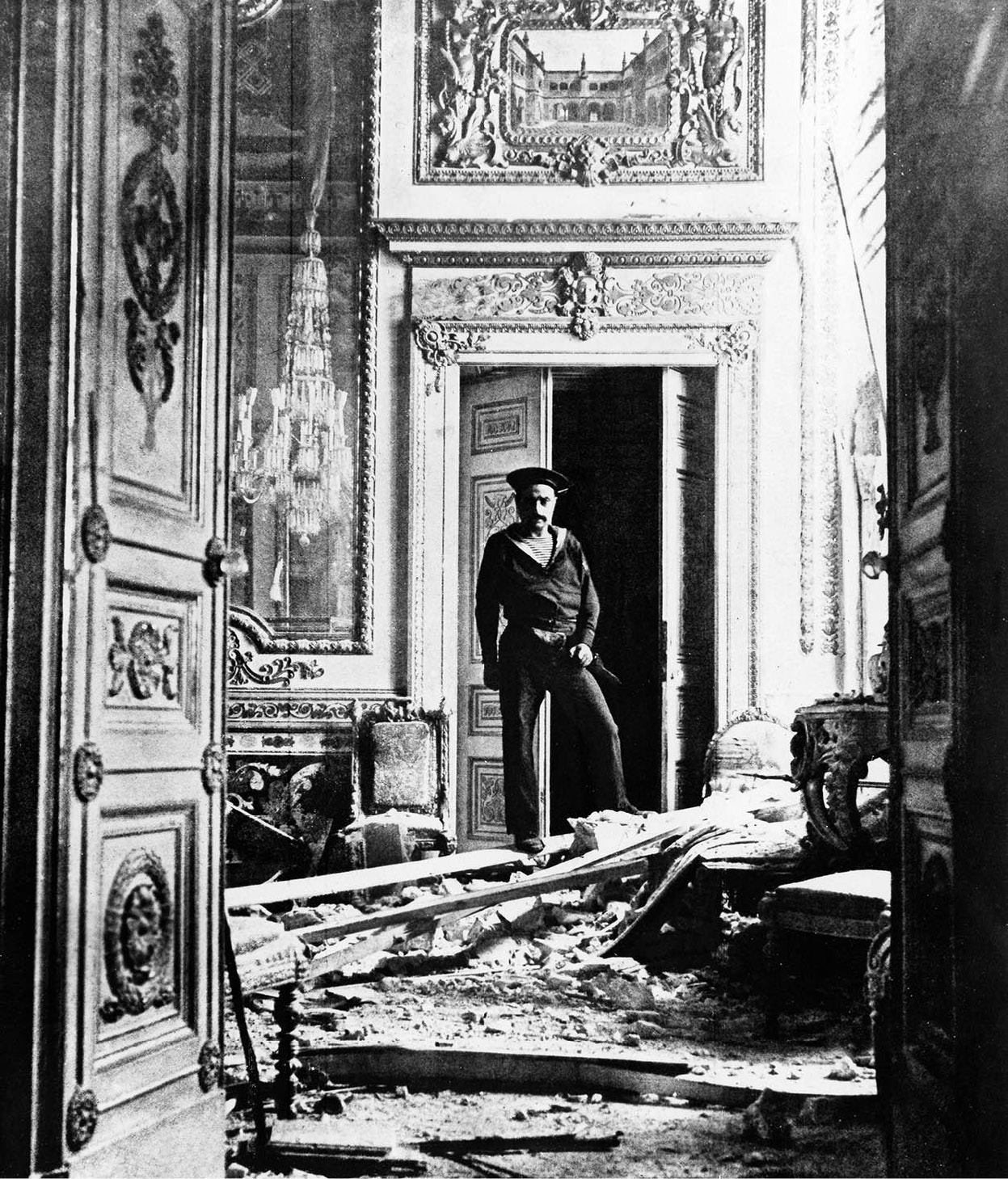

A sailor of the revolution troops in Necessidades Palace Emmanuel II in 1910.

TopFoto

Afonso Costa rose to leadership of the republican factions, but the hard stance of his anti-clericalism caused too much ill feeling to allow stability. Coups became standard. General Pimenta de Castro grabbed control briefly, but democratic forces deposed him.

Portugal, initially neutral, joined the Allies under Britain’s influence in 1916. The causes behind World War I meant little to the nation but cost thousands of lives, in Europe and Africa, and brought further financial upheaval and political unrest. Sidónio Pais formed a dictatorial government in 1917, but was assassinated in Lisbon the following year. Three years later, António Machado Santos suffered the same fate. In 1926, the democratic government of Bernardino Machado was overthrown by military forces and the constitution suspended. Leadership passed through various hands and finally to General Oscar Carmona. He remained president until 1951, but it was not his leadership but that of his most influential appointee that made stability possible. In 1928, Carmona appointed António de Oliveira Salazar to the post of finance minister, with wide-ranging powers. By 1932, Salazar was effectively prime minister.

Salazar’s New State

Salazar immediately set about reorganising the country’s disastrous financial morass, mostly through the narrow-minded austerity which reflected his own character. Having achieved what no leader had been able to do for a century, Salazar used his political capital to form a dictatorship, taking Mussolini’s Italy as his model for national order and discipline.

The “New State”, though nominally a corporative economic system under a republican government, was a fascist regime, with the National Union its only political party. It was authoritarian, pro-Catholic and imperialist. A state police organisation, the PIDE, was notorious in its suppression of subversion. A rigid and effective censorship settled like a thick fog over art, literature and free speech. Nothing negative or critical could find its way into print. A formerly lively journalism withered away. In blatant doublespeak, the government often referred to itself as a dictatorship without a dictator.

There was some resistance. In reaction to the powerful militaristic control there were numerous attempted coups and an underground Communist party that grew in power, leading the clandestine opposition. However, Salazar’s leadership was never strongly challenged.

Putting self-preservation ahead of ideology, Salazar pretended to adhere to the League of Nations’ non-intervention policy during the Spanish Civil War (1936–9) because he could not afford international censure, but actually sent a legion of some 20,000 soldiers to aid General Franco’s Nationalist forces. Franco’s victory served to validate the authority of Salazar’s own regime.

The republican era had seen a minor cultural resurgence, when democratic ideals encouraged efforts at mass education, a proliferation of journalism, and a few writers of modern fiction and poetry. But this was slowed by political upheavals, and effectively quelled by the New State. The greatest writer of the period, the poet Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935), had one major work, Mensagem, published in 1934, but it was not until after World War II that most of his works were in print. Few others transcended the romantic nationalism of the era, as formidable barriers to the larger currents of European culture were created. The censorship of the New State slowed original thinking to a trickle, and most of that was devoted to political subversion rather than artistic endeavour.

General Craveiro Lopes, Portugal’s twelfth president (1951–58), before the crowds.

Corbis

After World War II

During World War II, the New State concentrated on self-preservation. Though Salazar admired Hitler, Portugal’s traditional political and economic ties with Britain demanded neutrality, at least. However, Portugal did supply the Axis with much-needed wolfram (the ingredient necessary to alloy tungsten steel), almost until the end of the war. On the other hand, the Allies were granted strategic bases in the Azores. In fact, the war’s main effect – though it was not widely advertised – was to replenish Portugal’s coffers, as the government did business with both sides.

The defeat of the fascists should have given a signal to Salazar, a warning to mute his totalitarianism, but he was by now firmly entrenched. The changes over the next decade served primarily to protect the dictatorship still further from democratic insurgency.

In the 1950s, opposition to the New State solidified into two blocs. The legal bloc took advantage of the relaxed censorship in the month preceding the 1951 elections (the state’s way of giving the impression of some democratic freedom) to run independent candidates. Members of the other, furtive, bloc organised various protest actions and engaged in what propaganda they could. These means kept resistance alive, forcing Salazar’s hand and provoking new rounds of repression, deceit and constitutional changes, which eroded both Salazar’s authority and popularity.

Censorship was nothing new to a country dominated for so long by the Inquisition. In the 500-year history of publishing in Portugal, little more than 80 years have been free of censorship.

In 1958, General Humberto Delgado, a disenchanted member of the regime, stood for president, announcing that he would use the constitutional power of that position to dismiss Salazar. Despite mass demonstrations in his support, the official count declared that Admiral Américo Tomás, a Salazar loyalist, had been elected. Afterwards, constitutional decrees were enacted to prevent the repetition of such an event. The president was to be elected not by popular vote, but by an electoral college of the National Assembly, which was Salazar-controlled. Delgado was assassinated in 1965 by state police, while attempting to cross the Spanish border back into Portugal.

Salazar reviewing the Portuguese troops in 1940.

Getty Images

The empire strikes back

Portugal’s entry into the United Nations was prevented by the Soviet bloc and by opponents of Salazar’s imperial colonialism, until 1955. Membership was finally granted not because of any real change, but by a successful diplomatic effort to whitewash his despotism. Salazar would not change his policies because, despite the increasing cost of maintaining military rule in the colonies, they were very profitable for the homeland. Subsistence crops were increasingly neglected in favour of products like cotton, which fed the mills of Portugal while the Africans went hungry. The policy of assimilado – claiming that the goal was to assimilate the ethnic culture into the Portuguese one – allowed Portugal to exploit these “citizens” as virtually free labour.

Salazar’s imperial intransigence led to serious consequences in the post-war world, where old empires were rapidly crumbling. The violent 1961 Angolan uprising, brutally crushed by the Portuguese, ignited an explosion of African nationalism. Throughout the 1960s, the government became more and more involved in maintaining the colonies, which were renamed “provinces” in a 1951 decree that underscored the insistence on a permanent Portuguese settlement.

As many young men were conscripted for the wars in Africa, popular support waned rapidly. Angola continued to be an economic boon, but the other colonies were a drain. Salazar trusted ever fewer members of his regime, taking on more direct responsibilities himself for continuing the wars. He also relaxed his policy of fiscal austerity, and increasingly relied on foreign credit to finance the overseas operations.

An Unwilling Retreat

Despite international pressure, and increasing agitation within the colonies, Salazar’s regime fiercely resisted any incursions on its colonial outposts. In 1961, the territory of São João da Ajuda, a tiny enclave surrounded by the country of Dahomey, consisted only of a decrepit fortress and the governor’s estate. When Dahomey became independent from France, and delivered an ultimatum to Lisbon to return Ajuda, the Portuguese governor was forced to comply, but he waited until the last possible moment to surrender, then spitefully burned down the buildings before departing.

The end of an era

In 1968, the 79-year-old dictator suffered an incapacitating stroke; the long-awaited succession had arrived. Because Salazar – who was unwilling to face his own mortality – had made no provision for a successor, major upheavals were expected. But the transition to power of “Acting Prime Minister” Marcelo Caetano was relatively smooth. Salazar lived his final years in seclusion and died in 1970.

Caetano, once a protégé of Salazar, had resigned seven years earlier over conflicts with his superior. Called upon to resolve the national crisis, he saw the need for balanced change and stability, but was not bold enough. Many of the gravest injustices of the old regime were righted, but other changes were superficial, and the colonial issue was not confronted. When his early efforts at liberalisation failed to appease opposition unrest, Caetano returned to oppressive hostility.

Discontent among all ranks of the military over the continued ineffective colonial wars led to the formation of the Armed Forces Movement (MFA) in 1973. The following year, General António de Spínola published Portugal and the Future, a stinging critique of the current situation, which recommended a military takeover to save the country. The book’s messages had been voiced before but never by so powerful a source. Many factors built towards the revolution, but this publication, whose importance Caetano himself said he had profoundly felt, lit the fuse.

Two months later, on 25 April 1974, after a handful of premature uprisings, a near-bloodless coup began in Lisbon. Involving General Spínola and his fellow General Costa Gomes, it was conducted by angry “young captains” who commanded the 27 rebel units that seized key points throughout the city. Caetano and other government officials took refuge in the barracks of the National Republican Guard. The formal surrender came after a young officer threatened to crash a tank through the gates. The rebel takeover was quickly accepted throughout the country. The revolution, taking the red carnation as its symbol, sparked nationwide celebration culminating in joyful demonstrations on 1 May.

The initial government was a National Salvation group of military men, designed to give way to a constituent assembly as soon as it was practical. A provisional government was soon in place, and negotiations with African liberation movements went ahead. There were divisions about overseas policies, and an odd coup-within-a-coup developed, with Spínola attempting to wrest control from his opponents. It was unsuccessful and liberal forces continued to divest Portugal of its colonies. Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, the Cape Verde Islands, São Tomé and finally Angola were granted independence. One result of de-colonialisation was a mass return of Portuguese nationals to their homeland – as many as 500,000 people. Angola and Mozambique were abandoned to civil wars, East Timor devoured by Indonesia.

As the economy careered into an abyss, the political pendulum swung the other way, and there was huge social unrest. In 1976 the socialist leader Mário Soares became prime minister, but over the following decade governments frequently came and went. Socialist experiments were attempted as an antidote to years of Salazar. Land reforms were initiated, breaking up látifundios, the vast and long-established agricultural estates, particularly in the Alentejo, but these reforms have not proved successful.

In 1982, a long-awaited revision of the new constitution arrived. The democratic alliance and the far right were determined to rid the document of its Marxist taint. They were partially successful, but only after a period of nationwide demonstrations, strikes and resignations. The Council of the Revolution was eliminated, and the hope for a truly classless society remained an unrealised goal.

In the next few years, the country witnessed a shift away from socialism towards capitalism. Although the veteran socialist leader Mário Soares was elected president in 1986 (the first civilian to hold the post in over 60 years) and re-elected by a landslide in 1991, the capitalistic social democrats, under youthful economist Aníbal Cavaco Silva, won an overall majority in July 1987. In 1991, after a campaign based largely on his own forceful personality and his claims that his government had wrought nothing less than an economic miracle, Cavaco Silva won another resounding electoral victory.

General Antonio Spínola exits Queluz Palace after being nominated President of the Republic, 15 May 1974.

Corbis

Joining the EU

Such stability allowed Portugal to emerge from being the most backward economy in Europe to becoming, by the early 1990s, one of the most buoyant. In 1986, it joined the European Community and in 1992 took its turn at assuming presidency of the EEC. Among Cavaco Silva’s most successful programmes was the re-privatisation of many companies and industries nationalised by the Communists after the revolution.

In 1997, the Portuguese economy, then one of the fastest growing in Europe, met the requirements for the country to join the single currency, along with 10 other qualifying European Union states. Major public works projects such as a second bridge over the Tejo in Lisbon had already culminated in the successful hosting of Expo ’98, and this, even more than monetary union, was seen by many Portuguese as the final confirmation of their country’s arrival as a modern, thriving European economy, poised to meet the challenges of the new millennium.

Ex-Portuguese president José Manuel Barrosso is now president of the European Commission.

Corbis

However, a slowing down of the economy had wrong-footed the socialist government elected in 1995, and in 2002 Durão Barroso became prime minister of a centre-right government. In July 2004, he accepted the post of European Commission president. Former Lisbon mayor Pedro Santana Lopes became prime minister. In February 2005 a displeased electorate voted in the Socialist Party, now led by little-known José Sócrates, with its first ever overall majority. Restoring balance, the presidential election in January 2006 was won by a familiar social democrat, former prime minister Cavaco Silva. In 2007 the Portuguese experienced their most significant social change in years when they voted to legalise abortion. The same year, Prime Minister Sócrates assumed the EU presidency. In 2009, as leader of the re-elected Socialist Party, he formed a minority government.

Hit by the global recession, Portugal’s economic problems are profound. Like Greece, it suffers feeble growth, hampered by debt, low productivity and an ageing population, although its funding requirements are not as severe. In 2010, the government implemented austerity measures in an attempt to reduce the budget deficit; now comes the task of meeting the needs of its people while improving its economic outlook.

The Portuguese continue to seek their fortunes abroad. Around 4.3 million Portuguese live abroad, 10 times the number of foreigners living in Portugal. Their remittances make up 10 percent of the GDP.

Salazar

António de Oliveira Salazar, who led the country for 40 years, was the dominant figure of 20th-century Portugal.

António de Oliveira Salazar was a country boy, born in 1889, who took the strict conservative values of his father far beyond the small rural world that formed them, ultimately transforming the whole nation into his image of what it should be. As a professor of economics at Coimbra, Salazar was an active polemicist for the right. He made his first political impact as the youthful leader of the Centro Académico da Democracia Cristã (Academic Centre for Christian Democracy), a Catholic intellectual group that opposed the anti-clerical and individualistic philosophy of the republic. He made a brief foray into national politics but only accepted a political position when he could be assured of complete control.

This came in 1928, when the prime minister, General Carmona, offered Salazar the role of finance minister with absolute power over national finance. In 1932, he was appointed president of the Council of Ministers – another name for prime minister. Although there was opposition, dissent, and various plots against his life, Salazar’s pervasive influence on Portugal would not truly lift until the April revolution of 1974, six years after a disabling stroke, and four years after his death.

Salazar’s Portugal

Salazar imposed his own character upon the nation. He was austere, introverted, and seldom travelled outside Portugal. He steered his country through international affairs with as much neutrality as possible. Portugal accepted Salazar’s fascism as a kind of defensive posture in the face of the worldwide technological explosion of the 20th century. His conservative and at times reactionary attitudes towards industrialisation, agricultural reform, education and religion kept Portugal apart from the turbulence of the age. His attitude that Portugal was a naturally poor country – good for living in but not for producing anything – was widely held. Catholic cults, like that of Our Lady of Fátima, were encouraged and turned into propaganda.

Salazar also drew upon the romanticised history of Portuguese exploration and trade, inculcating a generation of schoolchildren with the self-aggrandising idea of Portugal’s manifest destiny as an empire. The country turned inwards, though still holding on to its colonies for as long as possible, and tried to ignore the changing face of world politics. It was a comforting but debilitating attitude.

Salazar lived quietly, taking modest vacations by the sea or in his beloved Beira countryside. He remained unmarried, though he had a close but apparently celibate relationship with his lifelong housekeeper, Dona Maria de Jesus Caetano.

On 3 August 1968, in his fortress sanctuary in Estoril, Salazar suffered a stroke that left him an invalid. He left no designated heir, but with surprisingly little turmoil, Marcelo Caetano, a brilliant lecturer but a rather weak politician, was made prime minister. For the remaining two years of Salazar’s life, he received few visitors and was given very little public attention. Those close to him chose not to tell him the truth about the succession of Caetano. Instead, they fabricated an image of Portugal still led by the old dictator.

When Dona Maria tried to convince him to retire, he refused and, in a last pathetic boast, claimed that he had no choice but to remain, because there was no one else. He died, aged 81, believing that he was still in control.

Salazar in 1958.

Getty Images

The shrine of Fátima draws thousands of pilgrims and worshippers.

Alamy