The Portuguese

A passion for coffee and cakes is a national characteristic to which visitors can instantly relate. Other traits are a little more complex.

Characterised as easy-going, smiling, patient, good-natured but imbued with an inner saudade, a tricky-to-define quality that equates to nostalgia or melancholy, the Portuguese tend to come across as a gentle, cordial people. They certainly offer a relaxed welcome to foreign visitors, whether they are seeking sunny beaches, medieval architecture, the beauties of the countryside, or the local food and wines. In addition, generations of international exploration, connections with former colonies, and immigration from abroad have made this a much more cosmopolitan country than you might expect – in Lisbon and the Algarve, at least.

A night out in Bairro Alto.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Infinite variety

It remains that the Portuguese population is one of the most homogeneous in Europe; however the country displays surprising variations from region to region, and in particular between north and south. There are also some physical differences in the people: in the north the basic Iberian strain – dark, thick-set – has been leavened with Celtic blood, while in the south, Jewish, Moorish and African ancestors are evident. The more sparsely populated north is generally more conservative, both politically and culturally, and is the bastion of Portuguese Catholicism. The south has a tradition of liberalism and adaptation. The two different temperaments – the warm Mediterranean and cool Atlantic – wash over each other. The people are as varied as their land. There is a saying that “Coimbra studies while Braga prays, Porto works while Lisbon plays”.

Of its 10.8 million-strong population, around two-thirds of the Portuguese live in the coastal areas, with the north far less populated.

Traditional folk dancing at Viana do Castelo.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Internal differences

There are other internal differences, too. Portugal had the fastest expanding economy in the European Union 10 years after joining, but in the last decade, it has been one of the least healthy economies in the EU sickroom. Like other countries in Europe, Portugal is attempting a tricky balancing act between decreasing the budget deficit, avoiding discontent, and promoting growth, and all while inflation and unemployment rise and wages fall. It seems that all the Portuguese have to look forward to at the moment is more austerity and an uncertain future.

There’s a greater sense of certainty, however, in the bucolic backways of Trás-os-Montes and the Beiras, among the windmills, the cobbled roads, and horse-drawn farmers’ carts. These rural communities remain almost defiantly untouched, with the men in their flat caps chatting in the town square. Venturing here you may well feel that you have stepped back in time. Rural people generally distrust Lisbon and all that it stands for: social turmoil, taxes, bureaucracy, centralised education. They would rather keep their distance. Able to sustain themselves by their harvests, they have little interest in inflation or trade deficits. They are self-reliant. Religious festivals are taken very seriously and can last for several days, especially in the Minho province and the Azores Islands, with celebrations including solemn processions, traditional dances and fireworks.

This was once an extremely patriarchal society, where women only gained the vote in 1975, and there has been great progress in terms of the position of women. Some urban women hold important jobs, and the lifestyle of many of the younger ones in the cities is similar to that of their counterparts in other European countries, but despite legal equality, attitudes are slow to change, particularly in rural areas, where most people live.

If in many ways the rhythm of Portuguese life is slow and habits cautious, this is less to do with Latin temperament or the climate than with the effects of the Salazar era and its aftermath; many people returning from the colonies had a deeply traumatic time in the clashes between new left and old right.

Fado in Tasca di Chico, Bairro Alto.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

However, there’s a more forward-looking feel to Portugal’s cities. Cutting-edge architecture has changed the face of Lisbon and Porto, and the cities are also significantly multicultural. Portugal has long been notable for emigration, with Portuguese people living all over the world, in South America, Africa, India and China. More than four million Portuguese citizens still live abroad, most of whom emigrated in the early and mid-20th century, settling mainly in France, Germany, Switzerland, Luxembourg (curiously, 15 percent of the population there are of Portuguese descent), United States, Canada, Brazil, and Venezuela. The majority of the Portuguese population in the United States is from the Azores islands, as are the Portuguese who settled in Canada.

In the 1970s the tide turned, and there was an influx of people from the former Portuguese colonies, especially Brazil, Angola and Cape Verde, bringing their influence to bear, particularly in and around Lisbon and Algarve. Other minority communities include Goans from India and Chinese from Macau. The African clubs in Lisbon are some of the capital’s funkiest venues; this is one of the best places in Europe to hear African music and experience its nightlife. Mariza, the current queen of fado, was born in Mozambique, and one of her most emotional songs is O Gente da Minha Terra (Oh People of my Country) – which expresses a very Portuguese sentiment in a very bittersweet, Portuguese way: the love of this staunchly patriotic land, a place of poets and sailors.

With the economic crisis and biting austerity of recent years, once again the flow has turned outwards. Young Portuguese are heading abroad – in many cases reversing the trend and making their way to Portugal’s former colonies in Angola and Brazil – in search of opportunities and a brighter future.

Coming Home

Traditionally Portugal was a country of emigration, where the very young and the old were left behind while wage-earners went abroad to work and send money home. However, in the 1990s, as Portugal boomed and EU capital brought new life to the country, many professional workers – doctors, lawyers and so on – arrived from Brazil and elsewhere, bringing with them their different tastes and lifestyles. Portugal also received an influx of migrant workers from Eastern Europe in an interesting reversal of earlier times. But with the economic crisis the situation has reversed once again, with 2 percent of the population leaving between 2011 and 2013, the majority being young graduates.

Portuguese farmer tilling his field.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Work

Unfortunately for the entire Portuguese population, and in keeping with the slowdown of the global economy and conditions elsewhere in the world, unemployment has been rising steadily over the last decade, and is at its highest among the under-24 age group. As people move to find work in the cities, and the birth rate remains low, villages are rapidly depopulating – some appear to be inhabited only by elderly widows. The urban population accounts for more than 50 percent of the national total, which is a considerable shift.

In industry and commerce there are a few conglomerates; the large majority of companies are small- and medium-sized businesses employing, for the most part, fewer than 10 people; textiles and shoes are the top manufactured products and excellent value for tourists. There are no local huge shopping chains, and the biggest department stores in Lisbon, malls apart, are the French-owned Fnac and Spanish-owned El Corte Inglés.

With a long coastline, fishing remains strong but it is not a high-paying industry. Agriculture has never been more than basically productive, despite the country’s rustic image. Portugal’s olive oil production, for example, just meets its own needs. About 10 percent of the workforce is in agriculture, which produces less than 4 percent of the GDP. Despite appalling annual fires, forestry is profitable, with cork still a major harvest. Port wine from the Douro valley is among Portugal’s most famous products, but table wines from many newly designated areas are reaching new peaks of quality. Tourism contributes a high proportion of foreign earnings and around two-thirds of the workforce is in the service sector.

Family ties

The family unit is a bedrock of Portuguese society, but this is now also beginning to change, with a decline in the birth rate (1.5 is now the national average) resulting in an ageing population. However, the Portuguese adore babies and small children, as you will notice out and in restaurants.

Portugal is a predominantly Roman Catholic country (around 97 percent), with a few Protestant communities, and a few Jewish and Muslim ones as well. One interesting group is the so-called Marranos, Jews who converted during the 16th- and 17th-century persecutions, and who retain some Jewish rituals, sometimes in combination with a nominal Catholicism. Catholicism in Portugal tends towards the colourful and mystical, bound up with local superstitions, ancient traditions and pre-Christian practices. Popular beliefs involve the phases of the moon and the threat of the evil eye. It is the tradition that older rural women dress in black after the death of their husbands for about seven years, and many wear it for the rest of their lives.

Shopping for hats.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

A changing society

As you travel around Portugal, it becomes increasingly obvious that this is a country that hangs in the balance between the old ways and the new. You can go from the graceful formality and strict religious conformity of a traditional village, where life seems to have remained unchanged for hundreds of years, to a sleek modernist art gallery or a nightclub that flings its doors open at 5am so that punters can dance their way through to the following afternoon. You can wander from an ironic and arty bar in Lisbon’s Bairro Alto, to a nearby hole-in-the-wall drinking den selling cherry brandy to gnarled old-timers.

This is a nation that is fiercely proud of its identity and traditions, but is not averse to change. Considering that Portugal was a country living under a dictatorship until 1973, it is extraordinary to think that it is one of the few places worldwide where the policy on illegal drugs is aimed at rehabilitation rather than retribution – drugs were decriminalised here in 2001, and the problem is regarded as a public health issue (those found in possession of less than 10 days supply are offered treatment rather than incarcerated).

These elements – of worldliness versus the parochial, of great exploration overseas versus the timelessness of life in a tiny whitewashed village – point to some of the contradictions in the Portuguese soul, contradictions that will remain part of the beguiling complexity of this mesmerising country.

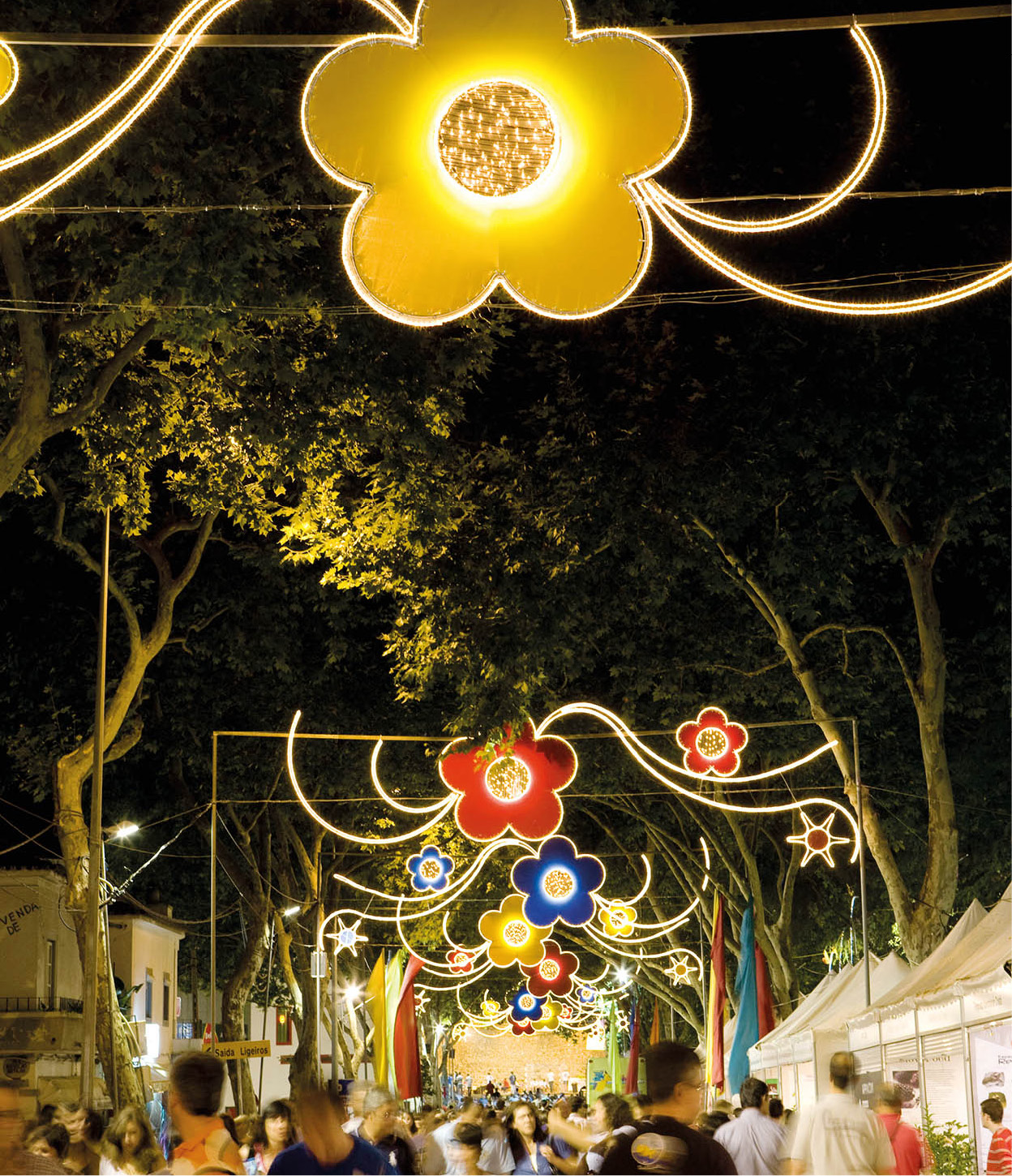

Celebrating the Festa de São João.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications