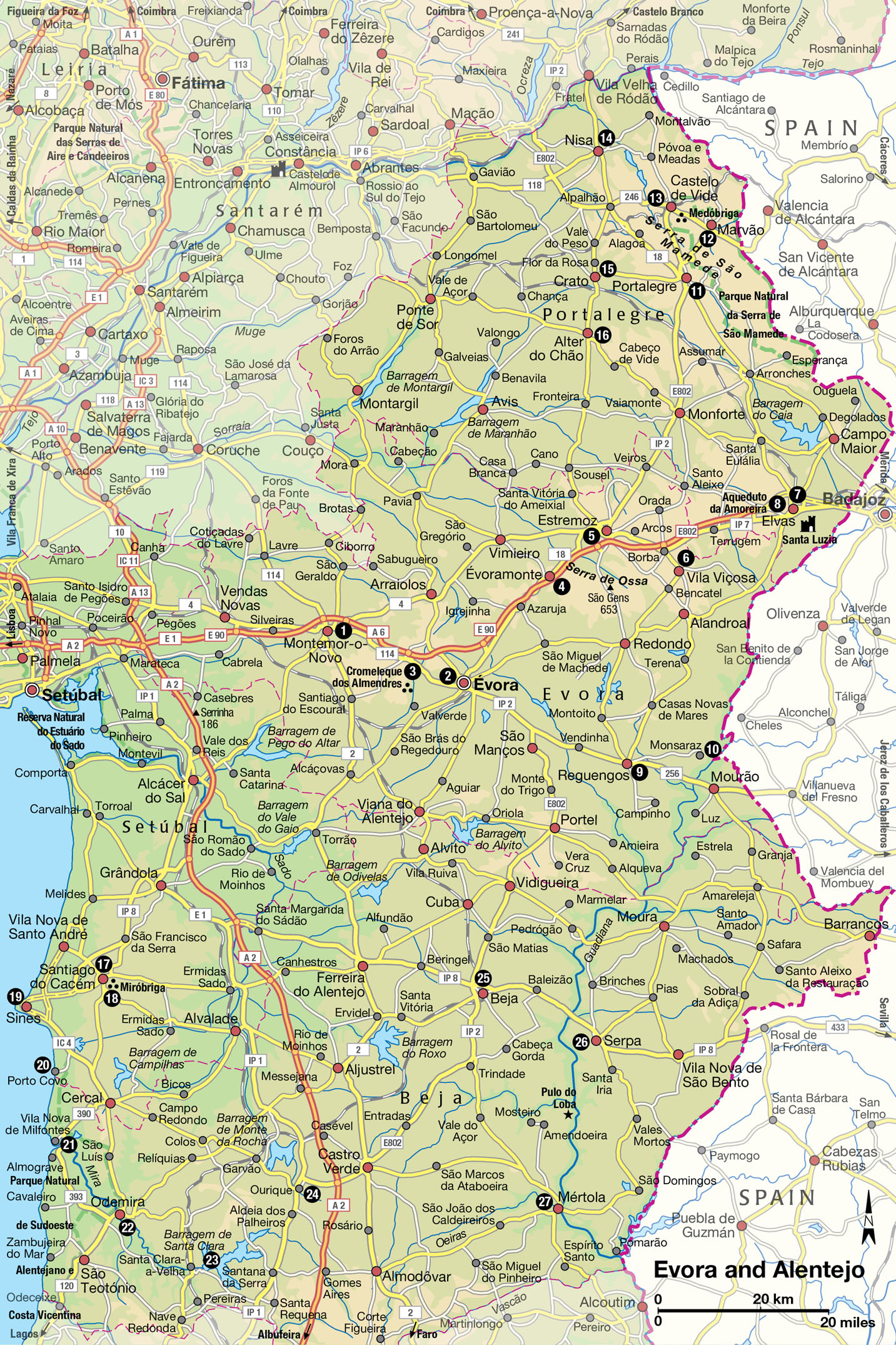

Évora and Alentejo

The Romans left more than a few footprints here, and there are historic towns and castles around almost every corner. Alentejo is one of the country’s grandest landscapes.

Main Attractions

Alentejo, literally “beyond the Tejo” (the River Tagus), has a distinctive character and beauty unlike that of any other Portuguese province. Its vast plains, coloured burnt ochre in summer, are freckled with cork oaks and olive trees, which provide the only shade for the small flocks of sheep and herds of black pigs. Nicknamed terra do pão (land of bread) because it is covered with field upon field of wheat and oats, Alentejo supports acres of grape vines, tomatoes, sunflowers and other crops.

The largest and flattest of the Portuguese provinces, about the size of Belgium, Alentejo occupies one-third of Portugal’s total area yet has only six percent of its population. It stretches from the west coast east to the Spanish border and separates Ribatejo and Beira Baixa in the central regions from Algarve in the south. The open countryside is punctuated by picturesque whitewashed towns and villages, many built on the low hills that dot the horizon.

Alentejo is rich in handicrafts. Rustic pottery with naive, colourful designs can be found everywhere. In addition, certain towns specialise in particular crafts or products: hand-stitched rugs come from Arraiolos, loom-woven carpets from Reguengos, cheese from Serpa, tapestries from Portalegre, and sugar plums from Elvas.

Cobbled streets lead to the sea in Estremoz.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Getting familiar

Geographically the province is split into two regions, Upper (Alto) and Lower (Baixo) Alentejo. Évora is the capital of the former and Beja of the latter. To the east are two low mountain ranges, the serras of São Mamede and Ossa. Some of the towns in these ranges, particularly Marvão, have breathtaking, even precipitous, settings. Portugal’s third-longest river, the Guadiana, flows through the province and in places forms the border between Portugal and Spain. This is by no means the only waterway, however. The region is criss crossed by a network of small rivers and dams.

Painted chairs for sale in Alentejo.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Roads that connect the towns are excellent. Most of the traffic is local and slow moving. You will need to equip yourself with a reliable road map; signposting is limited, and without a map you could drive many kilometres before discovering you have taken a wrong turn.

The Portuguese in general are not renowned for their tidiness but the Alentejanos are the exception. The towns are litter-free and there is always a dona de casa in view whitewashing her already pristine home. Cool and simple is the theme for Alentejo architecture: low, single-storey buildings are painted white to deflect the sun’s glare, and given a traditional blue or yellow skirting. Large domed chimneys indicate chilly winters. This practical style is followed from the humblest cottage to the large hacienda-style homes of the wealthy landowners; ornate and impressive architecture is reserved for cathedrals and churches.

Inland, Alentejo’s temperature in the summer can reach inferno level: what little wind there is blows hot and dry from the continental landmass – no cooling sea breezes here. Temperatures can drop dramatically in winter, resulting in bitterly cold nights.

Heading home from market.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Alentejo’s history

Alentejo is steeped in history, which goes back to the days of Roman colonisation. Later, it was the seat of the great landed estates (latifundia) of the Portuguese nobility and home to former kings. Even as late as 1828, Évora – the capital of the Alto Alentejo – was considered the second major Portuguese city, an honour that was first bestowed on it by King João I (1385–1433).

Estremoz, whose ancient castle has been converted into a comfortable pousada, was a nerve centre of medieval Portugal. Vila Viçosa was the seat of the dukes of Bragança, whose royal dynasty began in 1640 with the coronation of João IV and ended in 1910 with the fall of the monarchy.

Fact

To find out about the Rota dos Vinhos do Alentejo (www.vinhosdoalentejo.pt; Mon 2–7pm, Tue–Fri 11am–7pm, Sat 10am–1pm), visit the Alentejo Wine Route Support Office, at 20–1 Praça Joaquim António de Aguiar in Évora. There is a tasting room here as well so you can acquaint yourself with the region’s different grape varieties.

Politics, pastimes and popular song

Modern Alentejo is a far cry from the days of aristocratic domination, although farming techniques in the smallholdings have changed little. The greatest change is political: after the restoration of democracy in 1974 Alentejo became the heartland of Portuguese Communism. Many of the great estates – so vast that they included villages, schools and even small hospitals – were taken over by the farm workers during the revolution. Some of the landowning families were forcibly ejected, but the majority were absentee landlords anyway, living in properties nearer Lisbon or Porto. There is now a new landowning generation with a modern approach to agriculture and skilled at effective farm management.

Farming is the pulse of Alentejo, and the lives of its people revolve around the seasons. Aside from Évora the towns are small and the population is scattered in hamlets linked to farms. Secondary schools are restricted to the larger towns; in the more remote areas the general practice among young people is to leave school early to work in the fields, or, as in so many rural regions, to head to the cities.

One of the main pastimes for menfolk is hunting birds, small prey or wild boar (today heavily controlled). During the season (roughly October to February) you will often see men out with their shotguns, pouches and a pack of dogs.

Singing and dancing are popular across the length and breadth of Portugal, and Alentejo does its share. Here, the folk songs are the domain of the men. These songs are slow, rather melancholic, but of a completely different style from the haunting fado that is heard elsewhere. A slow tempo is set by the stamping of the men’s feet as they sing in chorus, swaying to the rhythm by the time they reach the end of the song. A performance is well worth listening to; ask at an Alentejo tourist office about where to hear these songs, known as ceifeiros.

Évora, the capital of the Alto Alentejo, is the largest and the most important of all Alentejana towns. It is a superb city, full of fascinating sights, all of which are in a good state of preservation. Fortunately, they are likely to remain so, as the entire city has been proclaimed a World Heritage Site by Unesco.

It takes about two and a half hours to drive from Lisbon to Évora, and a tour could comfortably be managed as a day trip. But that would be a pity as it would not leave time to see the lovely towns and villages along the way. To base yourself in Évora is easy; there are plenty of small guesthouses and hotels.

The route from Lisbon

To reach Évora from Lisbon, cross the Tagus via the Ponte 25 de Abril and head south and east, bypassing Setúbal on the A6 (IP7). You will not need a welcome billboard to tell you when you reach the Alentejo; suddenly you will find yourself at the edge of the rolling plains. Look for the jumbled twigs on top of high chimneys and buildings – homes to the storks that flourish in the province. As you drive further inland you will also notice the waning breeze and the gradual increase in temperature.

Short detours off the main road lead to small Alentejo towns. Pegões, rather dry and dusty, is typical. Further along, Vendas Novas is shady and neat with an air of affluence.

Montemor-o-Novo 1 [map] can be seen from quite a long way off, its ruined medieval castle crowning its low monte (hill). The castle ramparts are thought to date from Roman times. The town is divided into the upper old town and lower new town. As you might expect, the old town is more interesting. It was here that St John of God (São João de Deus) was born in 1495. He was baptised in the parish church, of which only the granite Manueline portal is still intact. In the square outside the church is a statue commemorating the saint, a Franciscan monk of great charity and humility. Although it does not have the population to support them, the town has five churches, three convents and two monasteries.

Tip

Visit Arraiolos, 20km (12 miles) north of Évora, to see women at work on the town’s famous hand-stitched carpets, based on Persian ones introduced in the 13th century. You can buy your own sample, large or small, to take home, and there’s a fine pousada nearby if you want to stay over.

Lights decorate the Évora streetscape for Festa de São João.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Évora: Alentejo’s city

As you enter Évora 2 [map] on the main Lisbon road, there is a small tourist office just before the Roman walls, where you can pick up a street map marked with suggested walks that take in the most important sights. The best place to park is outside the walls, then walk to Praça do Giraldo A [map] at the centre of the city where the main tourist office is located (www.cm-evora.pt; daily May–Sept 9am–7pm, Oct–Apr 9am–6pm). This large square is arcaded on two sides and has a 16th-century church and fountain at the top. From here you can explore the inner city with ease.

The city’s history can be traced back to the earliest civilisations on the Iberian peninsula. Évora derives its name from Ebora Cerealis, which dates from the Luso-Celtic colonisation. The Romans later fortified the city, renamed it Liberalitas Julia, and elevated it to the status of municipium, which gave it the right to mint its own currency. Its prosperity declined under the Visigoths, but was rekindled under Moorish rule (711–1165). Much of the architecture, with arched, twisting alleyways and tiled patios, reflects the Moorish presence. Évora was liberated from the Moors by a Christian knight, Geraldo Sem-Pavor (the Fearless), in 1165, in the name of Afonso Henriques I, Portugal’s first king.

For the next 400 years Évora enjoyed great importance and wealth. It was the preferred residence of the kings of the Burgundy and Avis dynasties, and the courts attracted famous artists, dramatists, humanists and academics. Great churches, monasteries, houses and convents were also built. The splendour peaked in 1559, when Henrique, the last of the Avis kings (and also Archbishop of Évora), founded a Jesuit university. In 1580, following the annexation of Portugal by Spain, Évora’s glory waned. The Castilians paid little attention to it, except as an agricultural and trading centre, and even after Portuguese independence was restored in 1640, it did not regain its former brilliance.

The ruins of a Roman temple – the temple of Diana – at Évora.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Roman remains

The oldest sight in Évora is the Templo Romano B [map] (Temple of Diana), at the top of the lanes opposite the tourist office in Praça do Giraldo. It dates from the 2nd or 3rd century AD and is presumed to have been built as a place of imperial worship. The Corinthian columns are granite, their bases and capitals hewn from local marble. The facade and mosaic floor have disappeared completely, but the six rear columns and the four at either side are still intact. The temple was converted into a fortress during the Middle Ages, then used as a slaughterhouse until 1870, an inelegant role but one that nevertheless saved the temple from being torn down.

From a good viewpoint in the shady garden just across from the rear of the temple, you can look down over the lower town and across the plains: the tiny village of Evoramonte is just visible to the northeast. To the right of the temple is the Convento dos Lóios C [map] and the adjacent church of São João Evangelista. The convent buildings have been converted into an elegant pousada but the church is open to the public. Founded in 1485, its style is Romano-Gothic, although all but the doorway in the facade was remodelled after the 1755 earthquake. The nave has an ornate vaulted ceiling and walls lined with beautiful tiles depicting the life of St Laurence Justinian, archbishop of Venice, dated 1771 and signed by António de Oliveira Bernardes. The sacristy and wax room behind the altar contain paintings and part of the Roman wall, and beneath the nave you can see an ossuary and Moorish cistern. The church is privately owned, as is the neighbouring palace of the dukes of Cadaval, a wonderful building sometimes open for exhibitions.

Carvings on the Cathedral in Évora.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The cathedral

The nearby Sé D [map] (Cathedral; daily 9am–12.20pm, 2–4.50pm) is a rather austere building. Its granite, Romano-Gothic-style facade was built in the 12th century, while its main portal and the two grand conical towers – unusual in that they are asymmetric, with one tower adorned with glittering blue tiles – were added in the 16th century. Before going inside, take a close look at the main entrance, which is decorated with magnificent 14th-century sculptures of the Apostles. With three naves stretching for 70 metres (230ft), the cathedral has the most capacious interior in Portugal, and the vast broken barrel-vaulted ceiling is quite stunning.

Once you have seen the cathedral, it is worth paying the nominal sum to see the cloisters, choir stalls and Museu de Arte Sacra (Tue–Sun 9–11.30am, 2–4pm). The latter, in the treasury within one of the towers, contains a beautiful collection of ecclesiastical gold, silver and bejewelled plates, ornaments, chalices and crosses. The Renaissance-style choir stalls, tucked high in the gallery, are fashioned with a delightful series of wooden carvings with motifs both sacred and secular. From the choir stalls you get a good bird’s-eye view of the cathedral. The marble cloisters are 14th-century Gothic, large and imposing, more likely to inspire awe than meditative contemplation.

Next door to the cathedral is the Museu de Évora E [map] (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), which has works by Josefa de Óbidos (1630–84), one of a small number of women painters of the time.

More Évora landmarks

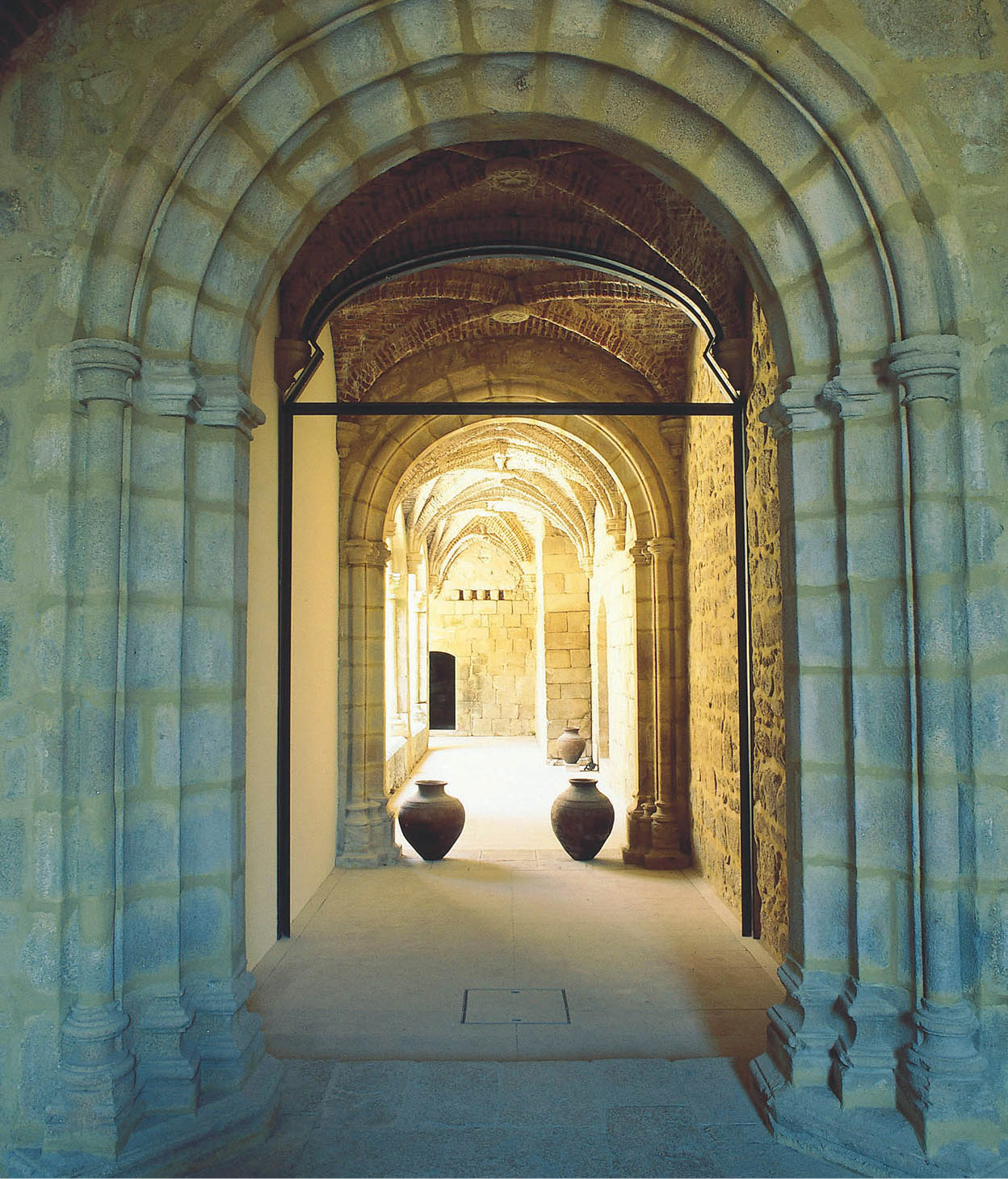

At the old Jesuit University F [map], some elegant and graceful cloisters are visible. You have to follow a short road down to the east of the city to reach it. The marble of the broad cloisters seems to have aged not at all since the 16th century, and there is still the peaceful atmosphere of the serious academic.

The classroom entrances at the far end of the cloister gallery are decorated with azulejos representing each of the subjects taught. If you take a slow walk back up the hill and head for the Igreja São Francisco, you will pass by another church, the Misericórdia G [map], noted for its 18th-century tiled panels and Baroque relief work. Behind it is the Casa Soure, a 15th-century Manueline house that was formerly part of the Palace of the Infante Dom Luís.

Tip

If you’re visiting Évora during the summer and want to cool off, go to one of the open-air municipal swimming pools (www2.cm-evora.pt/piscinasmunicipais) on the edge of town. Although well patronised because they are inexpensive, they are spotlessly clean, with plenty of lawn on which to stretch out and dry off.

As you walk along, have a good look at the houses. Nearly all of them have attractive narrow wrought-iron balconies at the base of tall rectangular windows. An odd tradition in Évora, as elsewhere in Portugal, is that visiting dignitaries are welcomed by a display of brightly coloured bedspreads hung from the balconies.

When you reach the Misericórdia church, take a brief detour to Largo das Portas de Moura H [map]. The gates mark the fortified northern entrance to the city, which was the limit of construction and safety in medieval times. This picturesque square is dominated by a Renaissance fountain, which dates from 1556.

Heading west along the Rua Miguel Bombarda, keep an eye out for the church of Nossa Senhora da Graça I [map] (Our Lady of Grace), just off the Rua Miguel Bombarda. Built in granite, it is a far cry from the austerity of the cathedral. A later church (16th-century), its influence is strongly Italian Renaissance. Note the four huge figures supporting globes which represent the children of grace.

The macabre Capela dos Ossos.

Fotolia

The most interesting thing about the Igreja de São Francisco J [map] is the Capela dos Ossos (daily 9am–12.45pm, 2.30–5.45pm; free; for more information, click here), but the chapterhouse is worth seeing too. It is lined with azulejos depicting scenes from the Passion and contains an altar dos promessas (altar of promises) on which are laid ex votos, wax effigies of various parts of the body given in thanks for cures. The church also has an interesting Manueline porch.

A Mother’s Curse

The church of São Francisco (for more information, click here) dating from the late 15th or early 16th century, has a remarkable chapel, the Capela dos Ossos. This bizarre and macabre room is entirely lined and decorated with the bones of some 5,000 people. It was created in the 16th century by Franciscan monks, when a large number of monastic cemeteries in the town were occupying valuable land. The skulls and bones have not merely been stored here in a random fashion; a lot of creative thought has gone into their placement. At the entrance you will see the inviting inscription: “Nós ossos qui estamos, pelos vossos esperamos” – “We bones lie here waiting for yours.”

Most gruesome of all are the corpses of a man and a small child hanging at the far end of the chapel. These centuries-old bodies are said to be the victims of the curse of a dying wife and mother. Father and son were supposed to have made her life a misery and their ill-treatment eventually killed her. On her death bed she cursed them, swearing that their flesh would never fall from their bones. The corpses are far from fleshy, but there is plenty of leathery substance attached to their bones.

Braids of human hair dating from the 19th century are hung at the entrance of the chapel – votive offerings placed there by young brides.

Évora’s public gardens – the Jardim Público – near the church provide a very pleasant walk; if you’re lucky you may catch the band playing on the park’s old-fashioned wrought-iron bandstand. The delightful Paláçio de Dom Manuel K [map] (1495–1521), or what remains of it, stands in the park. It has paired windows in horseshoe arches, typical of the style that gained its name from Dom Manuel. Exhibitions are held in the long Ladies’ Gallery.

If you’re not intent on going inside Évora’s monuments, a night stroll reveals its exterior architecture admirably. Nearly all the monuments are floodlit until midnight, and the winding narrow streets are extremely inviting on a balmy evening.

During the last week of June, Évora is filled with visitors who come to enjoy the annual Feira de São João (24–30 June). This huge fair fills the grounds opposite the public gardens. There’s a local handicraft market, an agricultural hall, a display of local light industry, and the general hotchpotch of open-air stalls, as well as folk singing and dancing, and the restaurants serve typical local food.

Évoramonte Castle boasts fantastic views.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Évoramonte and Estremoz

Alentejo has a number of megalithic monuments scattered across its plains, and some of the most important are just outside Évora (the tourist office will give you a map). The best preserved and most significant stone circle, or cromlech, on the Iberian peninsula is 12km (7 miles) west of the city. Close to the hill of Herdade dos Almendres, the Cromeleque do Almendres 3 [map] has 95 standing stones.

Near to the agricultural department of the University of Évora in Valverde, just southwest of Évora, is the largest dolmen on the peninsula. The Zambujeiro Dolmen stands some 5 metres (17ft) high with a 3-metre (10ft) diameter and dates from about 3000 BC.

On the road from Évora to Estremoz lies Évoramonte 4 [map], a village at the foot of a 16th-century castle. It was here that the convention ending Portugal’s civil war was signed on 26 May 1834. A commemorative plaque is placed over the house where the historic event took place. Évoramonte Castle perches high on a hill and offers remarkable views, well worth the clamber up to the top. Built in Italian Renaissance style with added Manueline knots, it grew out of a Roman fort.

The castle in Estremoz.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Estremoz: steeped in history

About 22km (14 miles) northeast, in the centre of the marble-quarrying region, lies the lovely town of Estremoz 5 [map]. Although much smaller than Évora, it has some fascinating monuments, and a pinky glow, courtesy of the local marble from which many buildings are constructed. The old part of town, crowned by a castle now converted into a pousada, was founded by King Afonso III in 1258, but is most often associated with King Dinis, whose residence it was in the 14th century. His wife, the saintly Queen Isabel of Aragon, is honoured by a statue in the main square, and a chapel dedicated to her can be seen in one of the castle towers (ask at the pousada).

The chapel is at the top of a narrow staircase; small, and highly decorated, it is where Isabel is said to have died, although some say that she died in the nearby King’s Audience Chamber. The chapel walls are adorned with 18th-century azulejos and paintings depicting scenes from the queen’s life. Behind the altar is a tiny plain room bearing a smaller altar, on which the Estremoz faithful have placed their ex votos, or offerings.

The most impressive part of the castle is the wonderful 13th-century keep, which is entered via the pousada. To get to the top you need to be fairly fit – or make a slow and steady ascent. The second floor has an octagonal room with trefoil windows. From the top platform there is a breathtaking view. The red rooftops contrast beautifully with the whitewashed houses and the green plains beyond, much of which are planted with rows of olive trees.

Across the square from the pousada is King Dinis’s palace. It must once have been a beautiful place, but all that remains standing after a gunpowder explosion in the palace arsenal in 1698 is the Gothic colonnade and star-vaulted Audience Chamber. It is used nowadays for exhibitions of work by local artists.

Having survived the narrow roads and hairpin bends on the drive up to the castle, the descent seems easy. The upper town is connected to the lower by 14th-century ramparts and modern buildings; the wrought-iron balconies are decorated with coloured tiles.

Estremoz is known for the small clay figures known as bonecas, which can be seen in the little municipal museum in Largo Dom Dinis.

If you like Portuguese wines then you may be familiar with the name Borba, where a cooperative produces a good red wine. The ancient village of Borba (about 11km/6 miles from Estremoz), which is said to date back to the Gauls and Celts, does not have much to show except for a splendid fountain, the Fonte das Bicas, built in 1781 from local white marble.

The overgrown castle ruins at Vila Viçosa.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Vila Viçosa: the Braganças’ base

Down the road from Borba is Vila Viçosa 6 [map], the seat of the dukes of Bragança, an entire town built of shimmering white marble. Because the surrounding area is pocked by marble quarries, the usually expensive stone is in abundance. It is a place completely different in style from the Moorish-influenced towns perched on the hilltops. It is cool and shady, its large main square (Praça da República) is filled with orange trees, and elsewhere there are lemon trees and lots of flowers everywhere. Viçosa means lush, and its luxuriant boulevards are a pleasure to walk along.

A lovely, if rather overgrown, medieval castle overlooks the town square. It is very peaceful there, the only sound being the cooing of the white fantail doves that nest in the ramparts. The drawbridge is lowered across the (dry) moat and the first floor has become a modest archaeological museum (Oct–Mar daily 9.30am–1pm, 2–5pm, Apr–Sept Tue–Fri 9.30am–1pm, 2.30–5.30pm, Sat–Sun to 6pm).

Vila Viçosa is best known for the Paço Ducal (the Ducal Palace of the Braganças; daily 10am–6pm), a three-storey building with a long facade, which is open to the public for guided tours. Its furniture, paintings and tapestries are very fine, and well worth seeing. The palace also contains an excellent collection of 17th- to 19th-century coaches.

The medieval arches of Monsaraz.

Fotolia

The palace overlooks a square in which stands a bronze statue of João IV, the first king of the Bragança dynasty. To the north of the square is a striking gateway, the Manueline Porta do Nó (Knot Gate), a stone archway that appears to be roped together, and is part of the 16th-century town walls.

From Elvas to Monsaraz

Heading east for about 28km (17 miles) from Estremoz, along the main road to the Spanish border, you will come to the strongly fortified town of Elvas 7 [map]. Founded by the Romans, it was long occupied by the Moors and finally liberated from them in 1230 – about 100 years later than Lisbon. The town was of great strategic importance during the wars of independence in the mid-1600s. The fortress of Santa Luzia, south of town, was built by a German, Count Lippe, for the purpose of repelling the Spanish. The older castle above the town was originally a Roman fortress, rebuilt by the Moors and enlarged in the 15th century.

If you walk around the ramparts that once encircled the town you can’t fail to be impressed by the effective engineering. The town itself is very attractive, from the triangular “square” of Santa Clara, with its 16th-century marble pillory, to the main Praça da República, with geometric mosaic paving.

The Aqueduto da Amoreira 8 [map], just outside the town, was designed by a great 15th-century architect, Francisco de Arruda. Its 8km (5-mile) length and 843 arches took nearly 200 years to complete. The cost was borne by the people of Elvas under a special tax named the Real de Agua.

Handwoven rugs used to be manufactured throughout Alentejo, but nowadays the small town of Reguengos 9 [map] is the only place where they are still made, in a factory that has been using the same looms for the past 150 years. To reach it, return to Borba then travel south for about 60km (38 miles). Reguengos is a nucleus of megalithic stones and dolmens, found at several sites near the town, and is known for its wine.

About 16km (10 miles) northeast of Reguengos is the delightful walled town of Monsaraz ) [map], so small it can easily be explored on foot – leave your car at the gate. It was fortified by the Knights Templar when the Moors were the enemy. In time, Reguengos became more influential and Monsaraz less so, which helped it become the relaxed and peaceful village it is today. Its main street, Rua Direita, is all 16th- and 17th-century architecture, yet the town maintains a medieval atmosphere. In one Gothic house is a famous 15th-century fresco, an allegory on justice, O Bom e o Mau Juiz (The Good and the Bad Judge). From the ramparts there are great views over to the Alqueva dam.

Alqueva Dam

The Alqueva dam on the Guadiana River, close to the Spanish border, is Europe’s largest artificial lake, with a surface area of 250 sq km (96 sq miles). The idea was first mooted in 1957 under Salazar, but the controversial project stalled and was only completed in 2006. A Roman fort was encased in concrete before being submerged, and the village of Aldeia da Luz, which lay in the flood zone, was moved stone by stone and rebuilt. The commendable purpose of the dam project was to irrigate farmland, produce hydroelectric power, and provide a huge reservoir, but dams are rarely constructed without some destruction, and here the disadvantage was that waters submerged 160 rocks covered with Stone Age drawings and flooded the habitats of rare flora and fauna.

The Portalegre Avenue.

Superstock

Portalegre

The lush countryside that surrounds Portalegre ! [map] is rather different from that in the low-lying lands. This area is in the foothills of the Serra de São Mamede, and the cooler and slightly more humid climate makes the landscape much greener. To get there, return to Estremoz and take the N18/E802 north – half of the route is now the IP2, a good road.

Quite a large town by Alentejo standards, Portalegre is unusual in that it is not built on top of a hill, but on the site of an ancient ruined settlement called Amaya. In the mid-13th century, King Afonso III issued instructions that a new city was to be built. He called it Portus Alacer: Portus for the customs gate which was to process Spanish trade and Alacer (álacre means merry) because of its pleasing setting. King Dinis ensured that the town was fortified in 1290 (although only a few of the ruined fortifications can be seen today) and João III gave it the status of a city in 1550.

The lofty 16th-century interior of the Sé (Cathedral; Tue 8.15am–noon, Wed–Sat 8.15am–noon, 2.30–6pm) is late-Renaissance in style. The side altars have fine wooden retábulos and 16th- and 17th-century paintings in the Italian style. The sacristy contains lovely blue-and-white azulejo panels from the 18th century, depicting the life of the Virgin Mary and the Flight to Egypt. The cathedral’s facade is also 18th century, and is dominated by marble columns, granite pilasters and wrought-iron balconies.

Portalegre’s affluence began in the 16th century, when its tapestries were in great demand. Continued prosperity followed in the next century with the establishment of silk mills. One tapestry workshop remains, the Fábrica Real de Tapeçarias, in the former Jesuit Monastery in Rua Fernandes, where looms are still worked by hand. Examples of the town’s handiwork can be seen in the Museu da Tapeçaria de Portalegre Guy Fino (Tue–Sun 9.30am–1pm, 2.30–6pm), housed in an 18th-century mansion in Rua da Figueira.

Portalegre was home to one of Portugal’s major writers: poet, dramatist and novelist José Régio (1901–69). His house has been opened as a museum. Of particular interest is his collection of regional folk art and religious works. Also of note is the 17th-century Yellow Palace, where the 19th-century radical reformer Mouzinho da Silveira lived. The ornate ironwork here is quite remarkable.

The white houses of Marvão.

Dreamstime

Spectacular Marvão

Marvão @ [map] is one of the most spectacular sights of Alentejo. About 25km (15 miles) north of Portalegre, it is a medieval fortified town perched on one of the São Mamede peaks. Its altitude (862 metres/2,830ft) affords it an uninterrupted view across the Spanish frontier. The precipitous drop on one side made it inaccessible to invaders and an ideal defensive barrier.

At this height the land is barren and craggy. The seemingly impenetrable castle was built in the 13th century from the local grey granite. Clinging to the foot of the castle is the tiny village, just a few twisting alleyways flanked by red-roofed whitewashed houses. Close to the church of Espírito Santo, on the street of the same name, is a Baroque granite fountain. On the same street is the sober-looking Governor’s House, its only decoration two magnificent 17th-century wrought-iron balconies.

On the road to Castelo de Vide are the ruins of the Roman settlement of Medóbriga. Many artefacts from here are now in Lisbon.

The Fonte Da Vila, a 16th-century fountain in the historic town of Castelo de Vide.

Pictures Colour Library

Castelo de Vide: fort and spa

Completing the triangle of noteworthy upper Alentejo towns is Castelo de Vide £ [map], a delightful town built in the shadow of an elongated medieval castle situated on the summit of a foothill on the northern serra. The town was originally a Roman settlement. Alongside it ran the major Roman road that traversed the Iberian peninsula. The settlement was sacked by the Vandals at the beginning of the 4th century, occupied by the Moors during their domination of the southern part of the peninsula, and eventually fortified by the victorious Portuguese in 1180.

Castelo de Vide is a spa town. You can drink its curative waters from plastic bottles, which are sold in the supermarkets, or sip from one of the numerous fountains located in and around the town. Perhaps its prettiest outlet is the quadrangled, covered fountain (Fonte da Vila), set in the small square below the Jewish Quarter. The Baroque fountain has a pyramid roof supported by six marble columns. The central urn is carved with figures of boys, and the water spills from four spouts.

As in nearly all fortified Alentejo towns, Castelo de Vide has two very distinct faces. The first is the older one, situated next to the castle, and the most interesting and picturesque part of it is the medieval Judiaria (Jewish Quarter). This host of back alleys, cobbled streets and whitewashed houses is liberally splashed with green, as potted plants sprout their tendrils from every available niche, windowsill and step.

The picturesque Jewish Quarter in Castelo de Vide.

Mark Read/Apa Publications

Notice the doors: this section of Castelo de Vide has the best-preserved stone Gothic doorways in Portugal. It also has the oldest synagogue, dating from the 13th century, although little remains of it now. The majority of the inhabitants of the neighbourhood appear to be elderly people who sit in the doorways of their homes calmly watching the world go by.

Further down the hill is the newer part of town: essentially 17th- and 18th-century buildings with wider, less steep streets, more space, more order and more elegance. On the main square, Praça Dom Pedro V, stand the grandiose 18th-century parish church and the old town hall, Paços de Concelho, remarkable for its huge 18th-century wrought-iron gate securing the main entrance.

Near the town you will find still more megalithic stones, including the 7-metre (22ft) Menhir da Meada. These pedras talhas seem to be everywhere, standing in fields, in open scrubland or in villages, inscrutable and ageless.

The hotel Flor da Rosa, Crato.

Turismo de Portugal

Portalegre’s neighbours

Nisa $ [map] is a small, rather rambling town northwest of Castelo de Vide. It has the mandatory medieval castle, walls and an unusual squat, round-towered chapel. Home-made cheese is Nisa’s speciality.

Some 24km (15 miles) south of Nisa on the road back to Estremoz is Flor da Rosa, where you may be able to buy local pots. But the most interesting place to see is the Convento de Flor da Rosa, dating from 1356 and founded by the Order of Knights Hospitallers of St John. An eclectic building, with a solid Gothic cloister, it was in use as a monastery right up until the end of the 19th century, and is now a pousada.

Fact

Flor da Rosa used to be a thriving pottery centre. The trade has dwindled in recent years, but pots are still made in the traditional way, and you may be able to see the craftsmen at work. Once fired, the finished pieces are know for their strong heat resistance. Unfired pots and pitchers are used to keep water cool.

Two royal marriages took place in Crato % [map], a couple of kilometres down the road. The first was that of Manuel I, who married Leonor of Spain in 1518 (his third marriage); the second was seven years later when King João III married Catarina of Spain. The main square is dominated by a splendid 15th-century stone veranda, the Varanda do Grão-Prior, which is all that survives of the priors’ residence.

Some 13km (8 miles) further south, in countryside filled with olive groves, is Alter do Chão ^ [map], a medieval town with equine traditions. It is from here that the Alter Real horse, closely related to the Lusitano breed, takes its name. The state-owned Alter Stud Farm (Coudelariade de Alter; tours mid-Sept–mid-May Tue–Sun 11.30am, 3pm, mid-May–mid-Sept 11.30am, 3.30pm) was founded in 1748 by José I (as he became two years later). Based on Andalusian stock, the animals thrived until the Napoleonic Wars when the best of them were stolen and the royal stables abolished. Happily, the breed, which excels in dressage, has been revived to a highly respected standard.

Milfontes, a village along the Mira river.

Fotolia

Unspoiled beaches

If you like unspoiled cliffs and beaches, quiet roads and villages, then you will delight in the Alentejo coast, although more and more tourists are discovering it. It borders on the open Atlantic and the ocean is therefore much rougher than on the south coast. There are plenty of sheltered bays for swimming, although the water is chilly.

Alentejo’s coast is not renowned for its nightlife. Bars, discos and fancy restaurants hardly exist; nor do large hotels, except at Vila Nova de Milfontes. There are campsites, however, and all the villages have at least one pensão. You’d better bring along your phrase book. Where tourists are relatively few, so are local people who speak English.

Most people approach the coast from Lisbon, from where access is easy thanks to the extended motorway network. Heading south, the IP8 branches southwest just before Grândola to Santiago do Cacém & [map], crowned by a castle built by the Knights Templar, which gives good views over the town and coast.

Anyone interested in things Roman should consider making a trip to nearby Miróbriga * [map] (Tue–Sat 9am–12.30pm, 2.30–5.30pm, Sun 9am–noon, 2.30–5.30pm). This Iron Age and Roman site is quite extensive and has been well excavated. There is also an interesting little Museu Regional nearby, concentrating mainly on the local cork industry.

Now it’s just a short hop to Alentejo’s largest coastal town, Sines ( [map], which is famous for being the birthplace of Vasco da Gama in 1460. It’s not what you would call a beauty spot. The old part and the harbour are still picturesque, but the nearby oil refinery and power station are hard to ignore.

Leaving Sines to the south, you can clear your lungs at the village of Porto Covo ‚ [map]. Though development has begun at the back of the village, it remains an intimate place, with cobbled streets swept scrupulously clean. The main square, grandly named Largo Marquês de Pombal, is very small, bordered by houses and the tiny parish church. A few small trees and plentiful benches surround the square. Down by the sea you can find shops, cafés and restaurants. Nearby secluded coves are easy to walk to.

Just off the coast of Porto Corvo is the fortified Ilha do Pessegeiro (Peach Tree Island), which in bygone days provided protection from raids by Dutch and Algerian pirates.

Returning to the main road, some 15km (9 miles) south of Porto Corvo is the small town of Cercal, beyond which you reach Vila Nova de Milfontes ⁄ [map], the loveliest and most popular of Alentejo’s resorts. The only time it gets really busy is in high summer when many Alentejanos and Lisboetas come for their annual holiday at the large campsite. There are a few bars, some seafood restaurants and a range of accommodation that includes the lovely up-market Castelo de Milfontes (tel: 283 998 231), converted from an ivy-clad fortress – drawbridge and all – which overlooks the estuary of the River Mira.

The river estuary provides long golden beaches and a calm sea. Park out at the headland overlooking the ocean, and you can turn back to see the town to your left, the winding river and the hills beyond – all very idyllic. If you are planning a day or two on this coast, then this is the place to stay. In early August it hosts the four-day Festival do Sudoeste, which could be described as Portugal’s Glastonbury, and attracts top names.

Almograve and Zambujeira do Mar offer more stunning, often deserted beaches and some fine clifftop viewpoints across the basalt cliffs to the sea. Of the two very small villages, Almograve is by far the nicer. Between these two beaches is another, Cabo do Girão, but it is naval property and access is prohibited.

Odemira, set on the banks of the Mira.

Fotolia

Southern Alentejo

You may well choose to start an exploration of the Lower Alentejo from a base in Lisbon, but you could start from here by going inland to the pretty town of Odemira ¤ [map], set on the banks of the Rio Mira, after which it is named. It is full of flowers and trees, so green that you are apt to forget that it is in Alentejo at all. Nearby is Barragem de Santa Clara ‹ [map], a huge dam on the Mira, where water sports are popular.

Ourique › [map] is an agricultural town north of the dam. In its surrounding fields (Campo do Ourique), fruit, olives and cork trees grow. These fields, however, have seen far more than mere farming in their time. In the nearby hamlet of Atalaia, archaeologists have excavated an extraordinary Bronze Age burial mound. And it was on the site of a battle called Ourique in 1139 (which may or may not have been here) that a fateful encounter was fought between the Portuguese and the Moors. Afonso Henriques had just become the first king of Portugal, and the victory on this battlefield strengthened his determination to expel the Moors from all Portuguese soil, and gave a tremendous boost to the flagging morale of his battle-weary forces.

A church in Beja.

Fotolia

Beja: a hot place

The capital of Lower Alentejo, Beja fi [map], is the hottest town in Portugal during the height of summer. It is a three-hour drive from Lisbon and an hour or so from Évora, or, if you are following the route from Ourique, it is about 60km (38 miles) on the IP2 (the old N123) or the N391.

A town existed on the present-day site as early as 48 BC, and when Julius Caesar made peace with the Lusitanians the settlement was named after this event, Pax Julia. During the 400-year Moorish occupation the name was adulterated to Baju, then Baja, until it finally became Beja.

It is now a fairly prosperous town, its income derived from the production of olive oil and wheat. A long-term German Air Force base here, dating from the 1960s, was turned over to the Portuguese in 1990. Beja is not a beautiful town, but it does have some interesting sights.

Pousada de São Francisco, Beja.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

One of them is the 15th-century Convento da Conceição, a fine example of the the transition between Gothic and Manueline architecture. The Baroque chapel is lined with carved, gilded woodwork. The chapterhouse, which leads to the cloisters, is tiled with superb Hispano-Arabic azulejos dating back to the 1500s. Their quality is rivalled only by those to be found in the Royal Palace at Sintra.

Legend has it that in the 17th century a nun at the convent fell in love with a French soldier, and when he returned to France she wrote him a number of love letters that were later published in Paris, and became something of a literary sensation.

Dissolved in 1834, the convent building also houses a notable Museu Regional (Tue–Sun 9.30am–12.30pm, 2–5.15pm; charge).

The small and modest Santo Amaro is the oldest church in Beja. It is thought to date back to the 7th century and is a rare example of Visigothic architecture. The Misericórdia church in the Praça da República is also worth a look. Beja’s 13th-century castle (Tue–Sun May–Sept 10am–1pm, 2–6pm, Oct–Apr 9am–noon, 1–4pm; free) still stands, and its castellated walls run around the town perimeter. The tall keep contains a military museum, and a narrow balcony on each side from which you can enjoy a remarkable view across the plains.

Fact

José Maria Eça de Queiroz, a diplomat and a graduate of Coimbra University, wrote passionate, biting novels that attacked the upper-class mores of his day. He spent 15 years in England, which he detested, but while there wrote some of his famous works, including Os Maias (The Maias).

Sunset on the Senhora da Guadalupe chapel, Serpa.

Turismo de Portugal

Driving in to Serpa fl [map] (about 30km/18 miles east of Beja) is – as with so many small Alentejo towns – like driving into a time warp. The castle and fortified walls were built at the command of King Dinis. A significant difference here from other 13th-century walls is that these have an aqueduct built into them.

A well-preserved gateway is the Portas de Beja; the gates, along with the rest of the walls, were almost sold by the town council in the latter half of the 19th century. Cooler heads prevailed and the walls were saved, although a great part of them had been destroyed in 1707 when the Duke of Ossuna and his army occupied the town during the War of the Spanish Succession.

There are several churches worth seeing (notably the 13th-century Santa Maria), as well as the delightfully cool and elegant palace belonging to the counts of Ficalho, the Paço dos Condes de Ficalho. It was built in the 16th century and has a majestic staircase and lovely tiles. The present lady of the house, Dona Maria das Dores, Condessa de Ficalho, incidentally, is the granddaughter of José Maria Eça de Queiroz (1845–1900), one of Portugal’s great 19th-century novelists (see margin).

The Rio Guadiana is considered the most peaceful of Portugal’s three big rivers (the others being the Tagus and Douro), but an exception is at Pulo do Lobo (Wolf’s Leap) between Serpa and Mértola. This is a stretch of high and wild rapids, which can be reached by road and is worth a visit if you are in the area – you will probably find you are the only tourist there.

Pork stew with clams.

Alamy

Mértola

Mértola ‡ [map], an ancient fortified town set in the confluence between the Guadiana and the Oeiras rivers, is one of Alentejo’s hidden gems. To get here from Serpa you can either take a secondary road to the south, or return to Beja, then take the main road south and turn off to the left. Whichever way you approach, the sight of the town’s strongly built walls crowned by a sturdy castle (daily 9.30am–5.30pm; free) is as impressive as it is unexpected.

Mértola has a long history, reaching back to Roman times. For five centuries under the Romans it was an important port on the then navigable Guadiana for exporting mineral ores from the nearby Minas de São Domingos, near the Spanish border. Its importance continued under the Visigoths, whose handiwork can be seen in the castle tower, and later the Moors. Twice in the 11th and 12th centuries it was capital of a kingdom which included Beja. With the growth of agricultural produce in the region Mértola was active in exporting grain to North Africa. When the river eventually silted up, the town slipped quietly into oblivion.

Leave plenty of time to explore the astonishing remains of the Roman port, the parish church, the castle and several museums (a single ticket covers all the sites), as well as the Igreja Matriz. Outwardly a Christian church, this pristine white building was originally a mosque, one of the few in Portugal to have survived virtually intact.

The exhibition of Islamic pottery in the Museu Islâmico (Tue–Sun 9am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm) is not enormous, but it is the finest in Portugal; and the Museu Romano (daily 9am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm) is very sophisticated. The town hall here burned down some years ago, and during the clearing-up operation the remains of a Roman villa were discovered. After finishing an excavation, the town hall was rebuilt and the Roman villa turned into an elegant basement museum.

Food and Drink

Alentejo’s culinary specialities should not be missed. Try sopa Alentejana – a filling soup of bread, with lots of fresh coriander (a herb used a great deal in Alentejo cooking), garlic and poached eggs. One of the classic meat dishes is carne de porco à Alentejana – chunks of pork seasoned in wine, coriander and onions and served with clams. Two much heavier but delicious stewed dishes are ensopada de cabrito – kid boiled with potatoes and bread until the meat is just about falling off the bone, and favada de caça, a game stew of hare, rabbit, and partridge or pigeon, with broad beans. The best Alentejo cheese comes from Serpa. Made from sheep’s and goat’s milk, it has a creamy texture and a strong, slightly piquant flavour. Évora has its own goat’s cheese, which is hard, salty and slightly acid. It is preserved in jars filled with olive oil.

Alentejo is a região demarcada – a demarcated wine region. Most towns have their own cooperative winery from which you can buy stocks at rock-bottom prices, and most restaurants have a low-priced cooperative house wine. In Lisbon, Alentejo reds are often drunk with bacalhau, instead of the more usual white. Try the reds from the Reguengos cooperative or those from Borba (for more information, click here), and white wines from the Vidigueira cooperative (www.adegavidigueira.com.pt).