Algarve

Moorish arches drenched in sunshine and spectacular coves of golden sand: Algarve offers a touch of the exotic that attracts visitors by the million.

Main Attractions

If one region of Portugal stands alone, it is Algarve. Its history under long Moorish control, its climate – more typically Mediterranean – and its abundance of fine sandy beaches endow Algarve with a character so different that it could easily be taken as a separate country. In the minds of many visitors, it is.

Separated from the rest of Portugal by rolling hills, Algarve, the southernmost province, seduced the ancient Phoenicians with its abundance of sardines and tuna, which they salt-cured for export almost 3,000 years ago. Four centuries later, around 600 BC, the Carthaginians and Celts arrived, followed in turn by the Romans, who adopted the Phoenician practice of curing and exporting fish – the precursor of Portugal’s large sardine tinning industry. They built roads, bridges and spas, such as that in Milreu.

But Algarve really blossomed under Moorish rule, which began in the early 8th century. The province’s name comes from the Moorish Al-Gharb, meaning “The West”. The Moorish period was one of vibrant culture and great scientific advances. Moorish poets sang of the beauty of Silves, its principal city, while the more practical settlers introduced orange crops, and perfected the technique of extracting olive oil, which is still an important Portuguese product. The blossoming almond trees in January and February are one of the most beautiful sights of Algarve thanks, according to folklore, to the passion a Moorish king once felt for a northern princess.

Praia da Rocha.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Legend has it that the princess, pining for the snows of her homeland, slowly began to waste away. Distraught, the king ordered thousands of almond trees to be planted across the region, then one February morning carried her to the window where she saw swirling white “snow flakes” carpeting the ground – the white almond blossoms. She quickly recuperated, and the two lived happily ever after.

Festival decorations in Tavira.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Moorish legacy

King Afonso Henriques led the Portuguese conquest southwards in the 12th century, and later his son, Sancho I, with the help of a band of crusaders, was to spearhead the siege of Silves and its estimated population of 20,000 people. It took 49 days before the Moors of Silves were forced to surrender. But in 1192 they reconquered the city and remained there for another 47 years. It was Sancho II, supported by military-religious orders under Paio Peres Correia, who finally crushed them. The last major city to fall was Faro, in January 1249.

The Arabic influence is visible even today: in many of the town names, in words beginning with the “al” prefix, in the so-called “North African blue” used for trimming the whitewashed houses, in the roof terraces used for the drying of fruit, and the white-domed buildings still popular in many towns. Algarvian sweets made of figs, almonds, eggs and sugar called morgados or Dom Rodrigos are yet another reminder of the area’s ancient heritage.

For centuries almond, fig, olive and carob trees represented a major part of Algarve’s agriculture, as they are suited to dry inland areas. The carob, whose beans are now fed to cattle but which also produce a variety of oil, are said to have sustained the Duke of Wellington’s cavalry during the Peninsular War. Thanks to the gentle climate, Algarve also produces pears, apples, quinces, loquats, damask plums, pomegranates, tomatoes, melons, strawberries, avocados and grapes.

Regional specialities

Wine critics regard all Algarve wines as undistinguished, and even in quite modest restaurants the house wine is usually from the better Alentejo range, or perhaps from even further to the north. But many local wines are quite palatable and should not be written off completely.

You will find good beer, the preference of most young Algarvios, widely available. Older men passing the time in tavernas and tascas drink medronho, a clear firewater with the kick of a mule, distilled from the fruit of the strawberry tree, Arbutus unedo. Another individual drink in Algarve is Brandymel, a type of honey brandy.

The pleasant market town of Loulé (for more information, click here), with its central tree-shaded walkway, is the crafts centre of Algarve, but local handicrafts are widely sold everywhere. Among them are baskets, hats, mats and hampers of rush or straw, which are made by local women who pick and dry the esparto grass in spring, then shred it into thin strips before they weave and plait it. You will see mats of grass, and of cotton and wool (although some of those on sale come from Alentejo). Cane basketry is almost always the work of men in the eastern towns of Odeleite, Alcoutim and Castro Marim. Despite the modern prevalence of cardboard boxes, baskets are still used to carry eggs, to display golden smoked sardines, and as fish traps.

Lagos, Loulé and Tavira – as well as numerous stores along the main N125 highway – are good places to find pottery, from big pitchers, plant pots, hand-painted plates and tiles, to the distinctive, lace-like chimney tops that embellish Algarve’s skyline. You will find a considerable range of copper pots and bowls – one such shop is on a street corner beside the market in Loulé. If you walk down the avenue you will see – and hear – coppersmiths at work in tiny workshops.

Woodwork is also a regional craft, from spoons made in Aljezur, to the brightly coloured mule-drawn carts you still see on the roads. Handmade lace is a skill that is being kept alive in such places as Azinhal. Up in the hills of Monchique (where a small craft shop has grown to an extensive display) you will find wooden furniture and woollen weaves.

Ilha de Tavira rescue equipment.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Key routes and places

The southern coastline, so richly endowed with golden sandy beaches in spectacular settings, is the region’s prime asset. At the onset of mass tourism in the 1960s it attracted developers, and much of the central region, around Albufeira, is now well developed. Those looking for smaller, quieter coastal resorts can still find them by travelling out to the west beyond Lagos and, to a lesser extent, east of Faro. Inland Algarve has its share of pretty villages and remains largely unspoilt countryside, although it is rapidly becoming the preferred dormitory area for expatriate settlers.

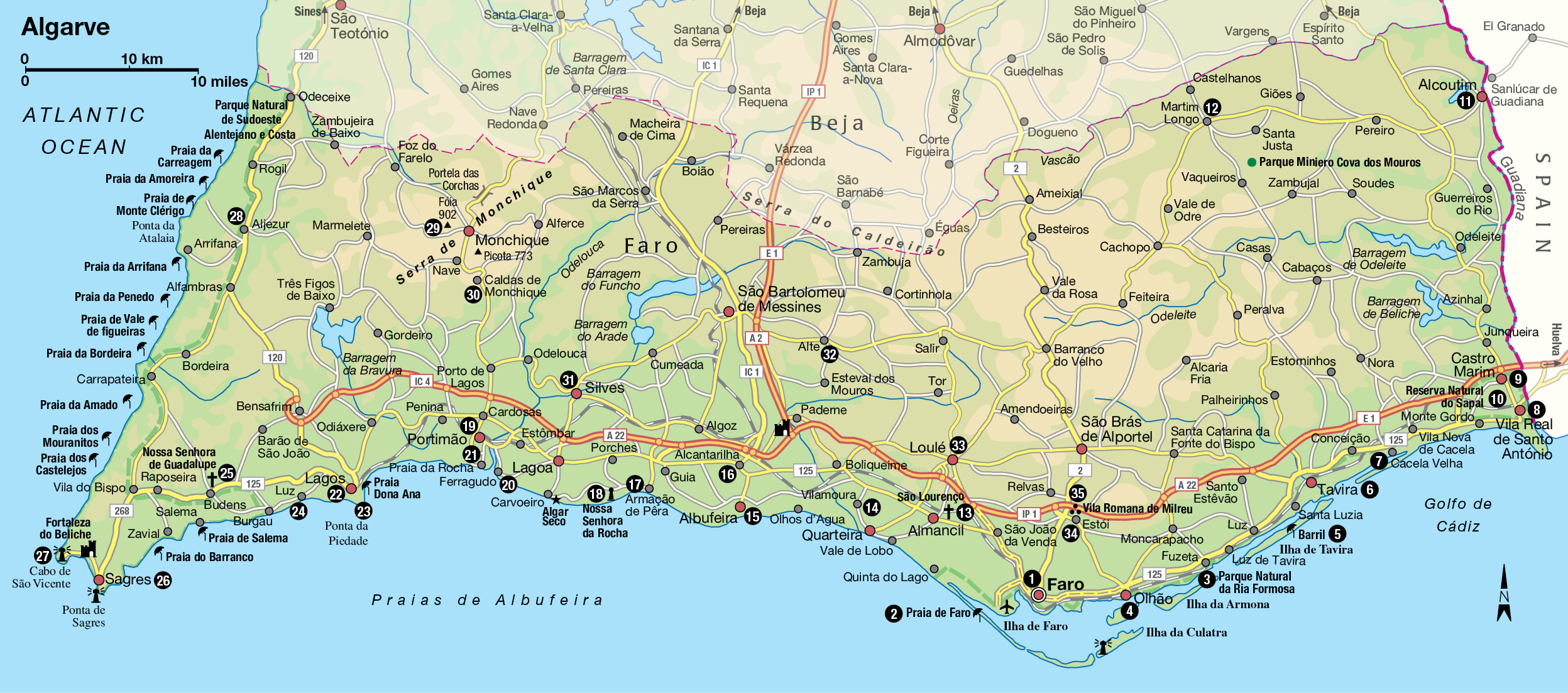

Driving around Algarve is not difficult. The N125 travels the length of the coast, while the A22 motorway (tolls payable) shadows it just inland. It is possible to drive from Spain in the east to Sagres in the west in a little over two hours.

An old building in the town of Faro is lit up at night.

Fotolia

Faro: the hub of Algarve

The roots of Faro 1 [map], the capital of Algarve, are ancient but not well documented, although it is certain that it was used by Greeks and Romans as a trading post before it became a flourishing Moorish town. Largely devastated by the 1755 earthquake, the city now has an architectural hotchpotch of styles and eras.

The centre of Faro is walkable, its character changing as you wander through streets of tiny houses, 19th-century mansions, modern villas and shops. It’s a bustling capital and has considerable charm. The main pedestrianised street, Rua de Santo António, is in the middle of the Moorish quarter (Mouraria), which lies between the old city (Vila-Adentro) and the 19th-century Bairro Ribeirinho, all of which lead from the port.

The exterior of Faro’s Igreja do Carmo.

Dreamstime

On the south side of the little harbour, through the 18th-century Arco da Vila that penetrates the old city walls, lies a peaceful and historic inner town, the Vila Adentro. At its centre is the Renaissance Sé (Cathedral; Apr–Sept Mon–Fri 10am–6pm, Oct–Mar Mon–Fri 10am–5pm, Sat all year-round 10am–1pm) with its 13th-century tower. Eighteenth-century polychrome tiles are an impressive feature in its chapels as well as in the body of the church. The red chinoiserie organ is also 18th century, and the choir stalls are a notable trophy from Silves Cathedral, installed when the seat of the diocese was moved to Faro in the 16th century.

In the square behind the cathedral a former convent with strikingly beautiful Renaissance cloisters is now the Museu Municipal (Apr–Sept Tue–Fri 10am–7pm, Sat–Sun 11.30am–6pm, Oct–Mar Tue–Fri 10am–6pm, Sat–Sun 10.30am–5pm), with a selection of Roman mosaics and stonework from Faro and from the important Roman site at Milreu, 12km (7 miles) to the north (for more information, click here).

On Praça da Liberdade, the Museu Regional do Algarve (Mon–Fri 10am–1.30pm, 2.30–6pm) displays some interesting relics of Algarve peasant life.

Beside the harbour, in the Port Authority building in the Bairro Ribeirinho, the Museu Marítimo (Maritime Museum; Mon–Fri 2.30–4.30pm) is worth a visit to see the broad range of Algarve fishing methods. Among the exhibits are model boats and a vivid depiction of the old way of trapping tuna in the bloody “bullfight of the sea”.

Faro’s most bizarre and macabre sight is the Capela dos Ossos (Chapel of Bones), reached through the Baroque Igreja do Carmo with its impressive facade and twin towers. The little chapel was built in 1816, its walls entirely covered with bones and skulls (allegedly 1,245 of them) from the church cemetery. Some find this grim display of mortality less depressing than the high-rises that contrast with the church’s fine facade.

Lighthouse and lagoon

Faro is protected on the seaward side by a huge lagoon dotted with sandbanks, with the airport on the western edge. Some of the sandbanks are large, especially the outer barrier islands, and the southernmost point is marked by the Cabo de Santa Maria lighthouse (faro means lighthouse in Portuguese).

The sand spit that starts near the airport and extends out as a long crescent, Ilha de Faro, can be reached by car and is the location of Praia de Faro 2 [map], a sandy resort much loved by the local people. Ilha da Culatra is the only other inhabited sand spit and can only be reached by ferry from Olhão. The whole of this natural lagoon and the adjacent area, stretching some 50km (30 miles) from Anção in the west to Cacela in the east, has been protected since 1987 as the Parque Natural da Ria Formosa 3 [map] (see margin tip for visitor centre details). This lagoon system provides 90 percent of Portugal’s harvest of clams and oysters. It is also an important bird sanctuary, especially for waders such as egrets and oystercatchers, and some rare species, including the purple gallinule.

Tip

Get a taste of the Parque Natural da Ria Formosa at the park headquarters (Centro de Educação Ambiental de Marim) at Quelfes, 3km (2 miles) east of Olhão (tel: 289 704 134; www.icnf.pt/portal). The park combines lagoons, marsh and islands and is great for birdwatching, as well as harbouring other rare creatures such as the European chameleon.

East of Faro

Travelling eastwards out of Faro takes you to the busy 17th-century town of Olhão 4 [map], built in the Moorish style, with a large fishing port. On the seafront by the leisure boats’ pontoons are the town’s modern (1998) market halls. Arrive at the fish market early and be prepared to use your elbows to reach the slithery hills of fish that the women hawk at the tops of their voices, poking them to prove their freshness. The best buys are gilt-head bream (dourada), bass (robalo) and sole (linguado). The other halls sell fruit and vegetables.

If you are not catching the ferry out to beautiful Culatra beach, move on to Fuzeta, where there is a sandy beach and a boat that can take you out to uninhabited Ilha da Armona (summer ferries also run here from Olhão) for a spot of sunbathing. Almost next door to Fuzeta is Pedras del Rei, the starting point for an exciting little journey by train over to the beach of Barril 5 [map] on the Tavira sandbank, the Ilha de Tavira. There is a footpath by the track, should the train be full.

A café or restaurant along the broad palm-lined promenade of Santa Luzia, a colourful fishing village overlooking the lagoon, is the place to sit and watch the fishermen stacking up encrusted octopus pots (alcatruzes) after removing their catch.

Tavira garden.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Tempting Tavira

One of the larger towns on the eastern side, Tavira 6 [map] is a delightful spot that has avoided the excesses of development and lost none of its grace. It elegantly borders both sides of the Rio Sequa, which becomes the Gilão as it slides under the seven-arched Roman-style bridge, the Ponte Romana, towards the sea. With its estuary and outlying island, Tavira flourished in the 16th century. But trade dwindled as the fish disappeared, and this lovely town, composed of narrow streets, pastel-coloured patricians’ houses, miniature towers, domes, unusual four-sided roofs and minarets, today leads a quieter life.

There are more than two dozen churches and chapels in Tavira, of which the most interesting are the Igreja da Misericórdia, built in 1541 but remodelled after the 1755 earthquake, with some lovely azulejo decorations; and the church of Santa Maria, rebuilt on the site of the town’s old mosque. Many of the churches are closed, but information about access to the major ones, as well as maps of the area, is available from the tourist office, to be found up the steps from the town hall in the main square.

A short ferry journey from the town will take you to the long white beaches of Ilha de Tavira, an unspoilt paradise (see box).

Ilha de Tavira

Tavira Island is a well-kept Algarve secret – a long, thin slick of land just off the coast, accessible via boat from Tavira. It is 11km (6 miles) long and 150 metres–1km (150yds–0.5 miles) wide, and is lined by some of the region’s loveliest beaches, with powder-soft sand lapped by Mediterranean waters. It is part of the Natural Reserve of Ria Formosa, and so retains its unspoilt beauty. There is a campsite here and several cafés, but that’s about it.

The most popular beach on the island is Praia do Barril. To the east of it, the island narrows into a thin sandy strip no more than 50 metres/yds wide, which is the site of the beautiful and aptly named Praia da Terra Estreita (Narrow Land Beach), also known as Praia de Santa Luzia.

Atmospheric fortified hamlets where time appears to have stood still are not what you expect to find along the southern coast of Algarve, but there is one at Cacela Velha 7 [map]. It has a miniature 18th-century fortress and a gleaming white church. The whole village clings tightly to a perch looking over a lagoon.

The border with Spain is reached at the Rio Guadiana. Facing Spain is Vila Real de Santo António 8 [map], its grid of geometric streets bearing the stamp of the Marquês de Pombal – the man who was responsible for redesigning old Lisbon in the 18th century. Pombal intended this town to be a model administrative, industrial and fishing centre, and he founded the Royal Fisheries Company here, but he lost favour with the court, and his plans never really took off. All the same, fishing remains an important activity.

Just west of Vila Real is the largest touristic development this side of Faro, Monte Gordo. The clutch of high-rise buildings lining broad tree-lined streets and overlooking a vast flat beach as yet remains fairly compact.

Castro Marim.

Dreamstime

Moors, mines and marshlands

Further inland along the Guadiana lies the architecturally appealing Castro Marim 9 [map]. This little town is also one of the oldest and historically most important areas of Algarve. Once a major Phoenician settlement, it also played host to the Greeks and Carthaginians before the Moors and Romans invaded. Portugal’s kings later used it as a natural point from which to fight the infidel to the east.

The huge castle built by King Afonso III after he dispelled the Moors in 1249 is still standing, overlooking the surrounding valley. In 1319, it was the first headquarters of the Order of Christ. The fort on the hill opposite dates from 1641.

Surrounding the town is the Castro Marim fen or marsh, wetland home of many migratory birds including storks, cranes and flamingos, and a hundred different species of plant life. An area of 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) is now protected as the Reserva Natural do Sapal ) [map].

Among the least-travelled routes in Algarve is the peaceful road along the Rio Guadiana. It is a soothing meander through golden, furze-covered hills dotted with corks, olive and fig trees. (Road numbers are N122 and 1063 for the riverside drive.) Alcoutim ! [map] is the northernmost Algarve town, and here it often seems as if time has stood still. Sunning dogs in the only square in town have priority, so you will have to park around them.

From the promenade that extends along the edge of the Guadiana River you can see the nearby Spanish town of Sanlucar de Guadiana reflected in the slow-moving water. Signs to the “castle” are a little misleading, as they lead to an empty shell of walls – but the view from here is worth the short walk.

An inland return route will take you through Martim Longo @ [map], where it is possible to make a diversion to the open-air copper mine at Vaqueiros, now transformed into the Parque Cova dos Mouros (http://minacovamouros.sitepac.pt; possible to join visiting groups if you call ahead), with a Neolithic settlement, gold prospecting and donkey rides. Continue through Cachopo to reach Faro.

West of Faro

The coastal route out to the west heads towards the main area of tourist development and to some of the most picturesque beaches. First stop outside Faro is at São Lourenço £ [map] for the small 18th-century church of the same name. Inside it is tiled, from top to bottom, in beautiful blue azulejos (tiles) depicting the life and martyrdom of São Lourenço himself.

Nearly all the well-known golf courses, more than 30 of them, lie west of Faro, each one an exclusive development with luxury accommodation (for more information, click here). Among them are Quinta do Lago, Vale do Lobo, which has a 16th hole, originally a famous seventh, above a coastal ravine, and Vila Sol at Vilamoura $ [map]. They take up a huge area on the edge of the Ria Formosa reserve, presenting a neat face of colourful flowerbeds and well-manicured lawns.

Just to the west of Vilamoura is the small resort and fishing village of Olhos d’Agua. The bonus here is that it is too small to attract the large tour operators. Tucked into a small cleft, the fishing village is as picturesque as any in Algarve, with sculptured rock stacks decorating the beach.

The beach at Albufeira.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Albufeira

Once a small fishing village favoured by the Romans and the Moors, Albufeira % [map] today is enduringly pretty, but also overwhelmingly touristy – rather like the Algarve version of the Costa del Sol in Spain – but has retained its character slightly better than some other Algarve resorts. It has a lively nightlife, scores of noisy bars, plenty of restaurants ranging from pizza joints to those serving more typical regional fare, and late-night discos. The steep streets descending into the old part of town are still very attractive, as are the rock-protected beaches where the fishermen keep their boats, traditionally painted with large eyes to ward off evil, as well as with stars and animals.

There is a bustling fish market near the Pescadores (fishermen’s) beach and a fruit, meat and vegetable market in the main square. Although development has been intense in this region, the coast westwards is a delightful symphony of eroded cliffs, stacks, gullies, grottoes and arches reaching a crescendo at Lagos. It is still possible to follow your nose and divert off to quiet beaches.

Fact

Algarve has many spectacular beaches but Praia da Marinha, south of Porches, is one of the most photogenic, its red sandstone cliffs eroded into arches and stacks. For a large expanse of sand backed by colourful cliffs, try Falésia just west of Quarteira.

Whichever route you take towards the west, it is likely you will end up in Alcantarilha ^ [map]. It’s worth a stop here if only to look in on the parish church, and especially the Capela de Ossos around the corner, which is packed with a chilling array of skulls. For family fun, visit nearby Aqualand (www.aqualand.pt; daily June 10am–5pm, July–6 Sept 10am–6pm; advance tickets can be purchased online), a large water park, with chutes and slides aplenty. Head south from here into Armação de Pêra & [map]. This mundane resort is rescued by an attractive promenade and beach, and it is a good place to eat fish.

All the grandeur and cragginess return to the coastline here and it is quite a descent to reach the beach at Rocha da Pena. Sitting on a bluff between two sandy coves is the simple white church of Nossa Senhora da Rocha * [map], dedicated to fishermen. Inland from here is Porches, which is famous for its painted pottery.

At the next roundabout on the N125 is Lagoa, increasingly commercial and with a lively morning market. This is also where farmers bring their grapes to the central cooperative wine cellar. A left turn at this roundabout leads down to Carvoeiro, a craggy coastline of isolated beaches, like that of Algar Seco. Praia de Carvoeiro, which is a lively tourist spot itself, has a pleasant little beach framed by cliffs studded with villas.

Albufeira beach rock formations.

Dreamstime

Portimão ( [map] (once a Roman harbour, Portus Magnus) lies west of Carvoeiro. An important fishing port, it is also one of the best shopping towns on the coast. Built on the west bank of the Arade estuary, Portimão is famous for its grilled sardines – have lunch beside the river to try some – and for its pastry shops. Facing it is the pretty fishing village of Ferragudo ‚ [map], with cobbled streets, pavement cafés and a good fish market. Close by is ocean-fronted Praia da Rocha ⁄ [map], which has a superb, much-photographed beach characterised by strange towering rock formations standing in the blue-green sea. The town itself, however, is a bit of a concrete jungle, although it does have all the facilities that visitors could ask for.

Albufeira slopes down to the sea.

Dreamstime.com

Lagos

Moving west from here you will come to Lagos ¤ [map], with a fine maritime tradition and a safe harbour beside a river estuary. Founded by the Carthaginians, it was taken by the Romans in the 5th century BC, when it was called Lacobriga (Fortified Lake). The Moors took it over in the 8th century and renamed it Zawaia (Lake). The city finally fell to the Portuguese during the reign of Afonso III. In 1434 Gil Eanes left from Lagos and became the first sea captain to round Cape Bojador, off northwest Africa, south of the Canary Islands – which was then the limit of the known world.

Most of Lagos was rebuilt in the 18th century, but some evidence of its darker past still stands in the columns and semicircular arches of Portugal’s first slave market in the Praça da República. Nearby stands a statue of Henry the Navigator, who sent ships from here off into the unknown. Note, too, the modern monument by João Cutileiro recording King Sebastião’s departure to the disastrous battle of Alcácer-Quibir in 1578.

A walk through the city’s attractive streets will lead you to the Igreja de Santo António, on the outside a sober-looking church, but inside an extraordinarily beautiful example of gilded carving. The nave has an impressive painted wooden barrel vault and Baroque paintings on the walls.

The church can only be visited through the Museu Municipal (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), which has a delightful collection of exhibits on local life in Algarve. Its eclectic collection of local finds, dating from the Bronze Age and Roman times, is layered over with fascinating glimpses of local life, and though the layout may at first seem old-fashioned, it is one of the most intriguing museums in the country.

Lagos has several pretty coves and beaches, especially Praia Dona Ana. Don’t miss the rock formations at Ponta da Piedade ‹ [map]. From the foot of the cliffs you might also hire a boat from a local fisherman to explore the grottoes, with their cathedral-like natural skylights.

Beyond Lagos lie three relatively unspoilt fishing villages, each of a different character and each worth a visit. Luz › [map] is the first of these, and perhaps the most developed, and is followed by Burgau and Salema. The countryside changes drastically, particularly after Salema, to a rockier and more undulating landscape. The trees look smaller and squatter, permanently bent from the unrelenting wind. Improved roads make driving in this area easier than it once was, but the new road actually bypasses the Knights Templar church of Nossa Senhora de Guadalupe fi [map] , where Henry the Navigator is said to have worshipped. It is easier to spot it when travelling west and to visit it on the return.

The lighthouse guards the coast at Cape São Vincente.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Sagres

Sagres fl [map] is a small fishing town, with Baleeira Bay as its port. The attraction to visitors is Fortaleza de Sagres, the fortress at Ponta de Sagres, used by Henry the Navigator early in the 15th century. He invited the most renowned cartographers, astronomers and mariners of his day to work here, and thus formed a fund of knowledge unsurpassed at the time, although modern historians believe he did not found a formal School of Navigation. Nothing that Prince Henry built is left, so it is hard to be sure. But you can see clues – notably a huge, 43-metre (140ft) compass rose on the stone ground of the fortress. There is a modern exhibition hall and tourist facilities in the fort, and a 1km (0.5-mile) walk along the top of the cliff.

Fact

It was to Sagres that seafarers returned in 1419 with the news that they had discovered an uninhabited island they called Porto Santo, which was later found to be part of the Madeiran archipelago.

All that remains now is to continue driving through this windswept terrain passing the small Fortaleza de Beliche, now a small pousada and restaurant, to reach Cabo de São Vicente ‡ [map], known to ancient mariners as O Fim do Mundo, the End of the World. From within the walls enclosing the lighthouse you can look down upon St Vincent’s rocky throne.

Legend has it that in medieval times Christian followers of the martyred St Vincent defied the Moors and buried his body on the cape, with a shrine to honour him. Sacred ravens were said to have maintained vigil over the spot and over the ship that carried the bones of the saint to Lisbon. Here, even on a calm day, waves crash against the cliffs with spray-tossing violence. In spring, the smell of the sea competes with the scent of cistus, the rock-rose bush whose perfumed leaves were once supposedly used by the Egyptians for embalming.

The wild west coast

Algarve’s west coast is virtually a continuous vista of cliff and sand, frequently pounded by a restless ocean and almost constantly under surf and spray. Although there are endless beaches, there are few towns of significance. Odeceixe, the most northerly town on this stretch of Algarvian coastline, is a small Moorish-style, windmill-topped village. A road follows the river for 3km (2 miles) to a beautiful sandy beach beneath towering cliffs at Praia de Odeceixe.

The most popular west coast circuit starts from Cabo de São Vicente and continues north through the vast, dune-backed Carrapateira to the attractive village of Aljezur ° [map]. The 10th-century castle was the last to be taken from the Moors. Directly to the west are the great sweeps of the Monte Clérigo and Arrifana beaches, the best on this coast. Heading inland from Aljezur towards Monchique leads back into the heart of Algarve.

The Serra de Monchique.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Mountains and springs

Towering above rolling hills, the granite mountains of Serra de Monchique attract streams of visitors to enjoy the views from the summit. In spring, Monchique is covered in flowering mimosa, and wild flowers bloom in the valleys between the Fóia and Picota peaks. Fóia · [map] is the highest point of Algarve, reaching 902 metres (2,960ft) above sea level. It is easily accessible along a winding road lined with cheerful restaurants selling roast chicken. The summit is heavily forested with transmitter aerials and the promised views are revealed only on clear days. Picota (774 metres/2,539ft) presents a different challenge and can be reached only on foot.

Fact

The eucalyptus trees which now grow in profusion in the Serra de Monchique smell lovely but are unpopular with environmentalists since they are bad for the soil and highly flammable.

The town of Monchique is rather disappointing if you merely drive through, but park the car and walk the steep streets and you get a better feel for the place. Worth visiting is Caldas de Monchique º [map], off to the right heading south, hidden in a deep valley and surrounded by chestnut, cork, pine, orange and eucalyptus trees. The spa has been in use since Roman times and the waters are believed to cure a number of ailments, from convulsions to rheumatism. The springs pour out an estimated 20 million litres (4 million gallons) of water a year.

A bridge leads to the town of Silves in Algarve.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Rural villages

Descending from the heights, but away from the coastal tourist zone, a more rural lifestyle is found in the towns and villages. Here, locals have managed to shrug off the effects of regular visitors and continue their traditional ways. One of the most interesting places is Silves ¡ [map], between Albufeira and Portimão. Silves was already populated by the 4th century BC and reached its greatest splendour under the Moors, who made it the capital of Algarve.

In its glory days Silves was the home of some of the greatest Arab poets. They recorded its ruin when the city fell to Portugal’s King Sancho I in 1189: “Silves, my Silves, once you were a paradise. But tyrants turned you into the blaze of hell. They were wrong not to fear God’s punishment. But Allah leaves no deed unheeded,” wrote one. Two years later the Moors occupied Silves again, before it was finally reconquered by the Portuguese.

Yemenite Arabs built the walled city, but the castle (daily May–Sept 9am–7pm, Oct–Apr 9am–5.30pm) – atop a Roman citadel, itself built on Neolithic foundations – and the defensive towers were rebuilt in the later Almohad period (12th–13th centuries) and heavily restored in modern times. The Moorish castle and the Christian cathedral dominate the city, the dark-red sandstone contrasting with the soft pinks and faded blues of the older surrounding houses. A sense of history still permeates Silves and the castle.

A bronze statue of King Don Sancho in Silves.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The Moorish cistern to the north once supplied the city’s water, and is architecturally similar to 13th-century cisterns found in Palestine and in Cáceres, Spain. Built by both the Romans and the Moors, the advanced irrigation system transformed Algarve into the garden of Portugal.

The Cathedral in Silves was formerly a mosque.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The Sé (Cathedral; Mon–Sat 9am–1pm, Mon–Fri 2–6pm) is 13th-century Gothic, restored in the 14th century and almost destroyed by the earthquake of 1755. Its apse is decorated with square arches, pyramidal battlements and fanciful gargoyles. The inner chapel of João de Rego dates from the 1400s. Various tombs here are said to be those of crusaders who helped capture Silves from the Moors in 1244. Here, too, for four years lay the remains of João II, who died in nearby Alvor in 1495, aged 40 – from dropsy, according to some doctors, from poisoning according to others.

From Alte to Estói

Northeast of Albufeira on the N124 is Alte ™ [map], a graceful village lying at the foot of hills and huddled around its parish church. Nossa Senhora da Assunção dates from the 16th century and has magnificent 18th-century tile panels. The tiles in the chapel of Nossa Senhora de Lurdes, among the best in Algarve, are of 16th-century Sevillian origin. Alte is a typical village of the province with its simple houses, delicate white laced chimneys, and timeless serenity.

A nearby stream has transformed the area into an oasis amid the region’s arid landscape. It’s a lush garden of oleanders, fig and loquat trees and rose bushes. The blue-and-white tile panels at Fonte Santa (Holy Fountain) are inscribed with verses by a local poet, Cândido Guerreiro. This area is perfect for picnics, or a walk up the Pena hill where you can visit the Buraco dos Mouros (Moors’ Cave). Further up the mountain is the Rocha dos Soidos, a cave filled with stalactite and stalagmite formations.

Heading back towards Faro you reach Loulé # [map], a small town whose old quarter – Almedina – is a maze of narrow streets, reminiscent of a North African casbah. The interior of the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (near the tourist office) is tiled with attractive 17th-century azulejos, and the Igreja da Misericordia has a fine Manueline doorway.

One of Loulé’s greatest attractions is the Saturday market, held in the onion-domed market halls, selling food of every kind, from home-grown fruit to live chickens. It draws visitors in from all over the Algarve. Loulé also has an extremely lively carnival in February, one of the best in the country.

The interiors of Palácio dos Condes de Carvalha.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Take a very slight detour east before you reach Faro and you will come to Estói ¢ [map], a pleasant village with a fine parish church, but best known for its 18th-century Palácio dos Condes de Carvalha, which has been turned into a luxurious pousada. The highly ornamental gardens of this “Queluz of the south”, with their statues and rococo fountains, and a splendid tiled staircase, are well worth seeing.

The town has a huge market – more of a country fair, held on the second Sunday of the month. It is a lively affair where you can buy a horse, sell a few sheep, stock up with fruit and vegetables or just buy sugared cakes to eat as you mingle with the crowds.

Vila Romana de Milreu

Close by is the Roman Vila Romana de Milreu ∞ [map] (Tue–Sun Apr–Sept 9.30am–12.30pm, 2–6pm, Oct–Mar 9.30am–12.30pm, 2–5pm), a site discovered in the late 1800s. There are some lovely mosaics here, the remains of thermal baths, and a well-preserved villa dating from the 2nd century. The largest structure, a temple, was consecrated as a Visigothic basilica in the 3rd century.

Algarve On A Plate

Heaps of crustaceans, and other seafood, fresh-from-the-sea fish, eel and octopus are major elements of Algarve’s culinary specialities, but it is also a region that is rich in fresh fruit and vegetables, ripened in the baking sunshine of the south. A much-loved dish is amêijoas na Cataplana, clams cooked in a copper pan of Arab origin, but other delights include slow-grilled sardines, sea bream or red mullet, razor clams or octopus, squid cooked in its ink, and bean stew with whelks. The rolling wooded hills of the interior mean that game and pork dishes are on the menu too. You can also discern the Arabic influence on cuisine here, particularly through the local sweets, usually created using nuts and dried fruits from Algarve’s orchards.

The countryside of the Alentejo.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications