Fado

The Portuguese blues, fado (which comes from the Latin fatum, meaning fate), presents elegiac songs about love, loss, the sea, poverty and beauty.

The unique musical tradition of fado has grown out of Portugal’s cocktail of culture – a result of the country’s early exploration and connections with places overseas. Like the blues, flamenco and tango, it was a music that grew out of hardship and poverty, but became the soundtrack to a nation.

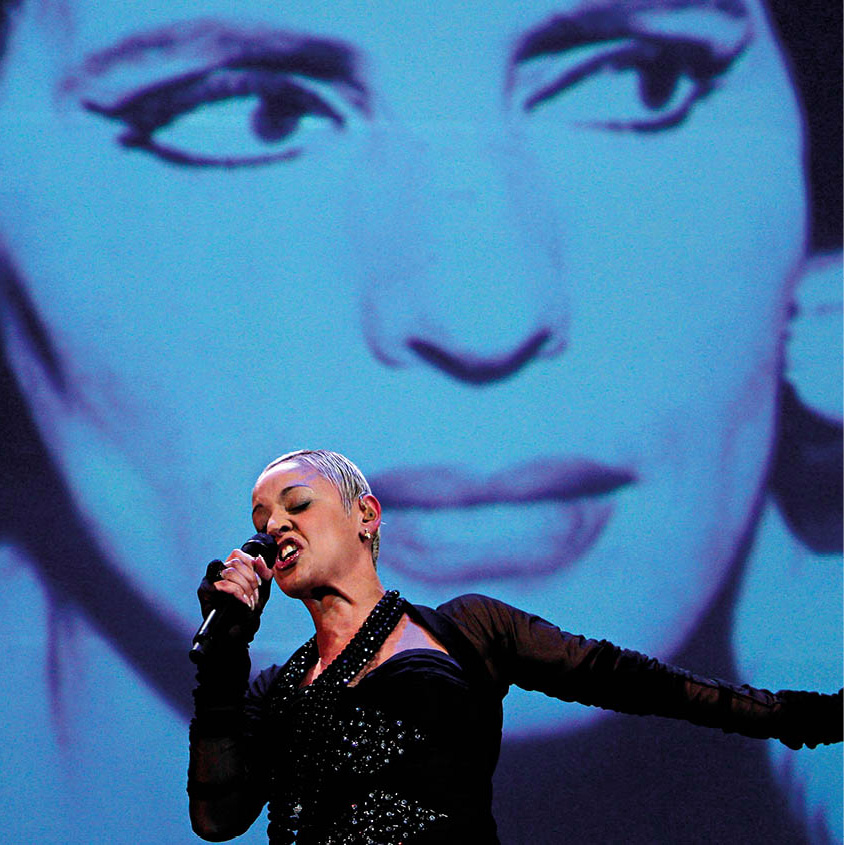

Portuguese fado singer, Katia Guerreiro, performs at The Bahrain International Music Festival in Manama.

Corbis

Fado’s sad, distinctively Portuguese songs are thought to have developed from the music of the Moors, who influenced the country in many ways, and the Lundum music of the Brazilian slaves, who would arrive in Portugal after long sea voyages in the early 19th century. One famous fado song, called The Black Boat, talks specifically of a senzala (place where the slaves were kept). Many early songs are related to the sea, to faraway lands, and longing for home – subjects unsurprising in such a seafaring nation.

Historic entertainment in a café.

Getty

The other major source for the songs is believed to have been the verses of the minstrels and jesters in the middle ages, which share similar themes to those of fado. These included the cantigas de amigo (songs about a boyfriend), love songs that are sung solely by women, and satirical songs making jibes about the government and politicians.

Fado seems to have first taken off in the working-class districts of Alfama and Mouraria in Lisbon, and, rapidly gaining in popularity, later spread to the university of Coimbra, where it took on a quite different character. The fado in Coimbra is sung only by men, praising the beauty of women, and often takes the form of serenades.

Fadistas at first came from the working class – this was not the music of the bourgeoisie. Its musicians and singers mixed with the edgier elements of society – the criminals and prostitutes. The most famous fadista of the 19th century, Maria Severa, was a prostitute, who sang in her mother’s tavern in Alfama. She attracted the attention of the aristocratic Conde di Vimioso with her singing, and they embarked on a scandalous love affair which crossed class barriers in a hitherto unacceptable way.

The conde’s influence saw fado reach the court, but Maria Severa died aged just 26, either from tuberculosis or suicide. She always sang wrapped in a black shawl, which female fado singers still do today in her memory.

During the mid-20th century, the dictator Salazar (in power from 1932 to 1968) insisted that fado singers become professional and only sing in specially designated fado houses. This was the “golden age” of fado. During this period the famous names were Alfredo Marceneiro and Maria Teresa de Noronha, and the guitar players Armandinho and Jaime Santos, but most famous of all was Amália Rodrigues (see panel), whose rise to international superstardom saw the status of fado change forever.

Amália Rodrigues

Portugal’s most famous fadista, Amália, was born in 1920 into a poor family, and as a child sold fruit on the Lisbon docks. Her remarkable voice was noted by local people, who often asked her to sing for them, and after years of amateur performances she had her first professional engagement aged 19. Her career quickly took off, and she became Portugal’s most revered star. Amália appeared in films and became an international icon and a national treasure, continuing to perform in public until 1990. When she died in 1999 there were more than three days’ mourning in Alfama. Her house in Lisbon now houses the Museu de Amália Rodrigues.

Fado singer, Mariza, performs during a concert in homage to legendary singer Amália.

Corbis

The singers and the song

The fadista, a powerfully voiced singer, is usually backed by a guitar – the twelve-stringed Portuguese version – and a classic guitar, which is called a viola in Portugal. The male fado singer usually wears a black suit; he sings about love affairs, the city, life’s misery, bullfighting, politicians, and about the past. The female singer will also wear black, and sings heart-rendingly about love and death, love lost, and tragic romance.

The Portuguese say that it takes more than a good voice to become a true fadista – it takes soul.

All fado is linked with the concept of saudade. This difficult-to-translate term is a kind of nostalgic longing and yearning for something that is lost. It is an emotion that has a peculiar resonance in the Portuguese make-up.

Fado is a performance, not a sing-song, and you are expected to be quiet and listen. The fado of Coimbra is usually taken even more seriously than that of Lisbon, which means it is very serious indeed.

For a while after the 1974 Carnation Revolution, fado lost some currency in Portugal, as it was associated with the old regime. However, it crept back, becoming even more widely sung than before. Modern fadistas have brought the sound up to date (see panel, page page 171).

Singers in the Bairro Alto.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Where to find it

There are plenty of places where visitors can experience fado for themselves. It is best to hear it sung at its source, in Alfama, Bairro Alto and Mouraria in Lisbon or in Coimbra, although there are fado houses in other towns across Portugal. Finding true, earthy fado has some similarities with seeking out authentic Spanish flamenco. There are smart and formal venues, with famous singers, but these tend to work out very expensive when you combine admission charges and the accompanying drinks and meals, and they don’t have the same intimate atmosphere.

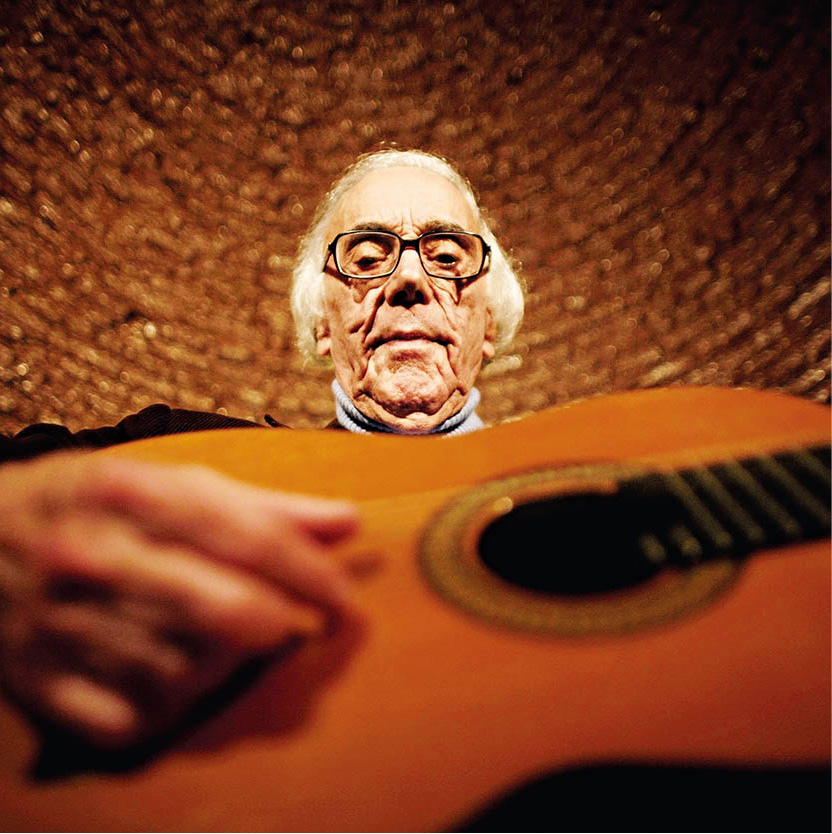

Portuguese fado singer and former judge Fernando Machado Soares.

Corbis

Alternatively, there are scruffier backstreet bars where the experience feels more spontaneous and earthy. These offer fado vadio (street fado), which means anyone can stand up and have a go, and some local people come back to do so week after week. The singers might not be of quite the same quality, but the immediacy of the passion and atmosphere may far exceed the more refined version.

Modern Fadistas

The new wave of fadistas is still dominated by women: Mariza, Mizia, Ana Moura, Katia Guerreiro and Cristina Branco. Of the male new guard, there is Pedro Moutinho, born into a well-known family of fadistas in Oeiras. The most natural successor to Amália is Mariza, instantly recognisable with her bleached blonde hair. She was born Marisa dos Reis Nunes in Mozambique, then a Portuguese colony, in 1973, of Portuguese-African parentage. At the age of three, the family moved to Mouraria in Lisbon, and she began singing at the age of five in her parents’ restaurant.

Mariza moved away from fado in her teens, experimenting with other types of music, and travelling in Brazil when she was in her twenties, but she came back to fado, and her powerful, theatrical, yet awesomely emotional performances make her a natural star. Her background, with elements of German, Spanish, French, African and Indian ancestry, in some ways represents the story of Portugal, and a particularly emotional song in her repertoire is Oh Gente do Minho Terra (Oh People of my Country).

Mariza performs in sell-out concerts all over the world, in venues such as the Carnegie Hall in New York and the Royal Festival Hall in London, and has twice received Latin Grammy nominations. In 2002 she sang the Portuguese national anthem at the FIFA World Cup, when the home team (South Korea) played against Portugal.

Chestnut street seller, Lisbon.

Dreamstime