Portuguese Architecture

Some of Portugal’s finest architecture is found in its religious buildings, but the wealth from the Age of Discoveries also left a legacy of fine palaces.

Portugal’s unusual geographical position, cut off from Europe by Spain on one side, facing the New World on the other, is reflected in its architecture. The country’s architects have always looked outside for influence and affirmation, and local traditions have blended harmoniously with imported ideas.

The Old Cathedral in Coimbra.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Romanesque

The story of Portuguese architecture really begins in the Romanesque period of the 12th century, when nearly all buildings of any importance were religious ones. This was the time when the kingdom was founded, when Portugal was (largely) reconquered from the Moors, and Christianity was strongly felt.

In the north, Romanesque-style churches continued to be built well into the 14th century, when the Gothic style was already spreading throughout the rest of the country. Portuguese Romanesque is an architecture of simple, often dramatically stark forms, whose sturdiness is frequently explained by the need for fortification against the continued threat of Moorish or Castilian invasion. This fortified appearance is enhanced in the cathedrals of Lisbon and Coimbra by the crenellated facade towers.

Most of these buildings are of granite. The hardness of this material renders detailed carving impossible, thus favouring a simplicity of form. In areas where the softer limestone abounds, such as the central belt of the country (including Coimbra, Tomar and Lisbon), carved decorations are more common.

The Romanesque period saw the construction of cathedrals follow the path of reconquest from Braga to Porto, southwards to Coimbra, Lamego, Lisbon and Évora.

Lisbon’s cathedral.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

These Romanesque churches share a certain robustness; a method of construction based on semicircular arches and barrel vaults; a cruciform plan; and a solid, almost sculptural sense of form in the interior which allows for a play of light and shade. This sobriety is accentuated by the paucity of decoration, which is frequently reduced to the capitals of columns and the archivolts surrounding the portals. When the tympana are not bare, the simplified carvings are usually stylised depictions of Christ in Majesty, or the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God), or simply of a cross. In some cases, animals and serpents climb the granite columns, as in the Sé Velha (Old Cathedral) of Coimbra or the richly decorated principal portal of the early 13th-century São Salvador, in Bravães in the Minho.

Gothic

In France, new methods of construction involving pointed arches and ribbed vaults allowed for lighter, taller architectural forms. As the main weight of the building was now borne outside at fixed points by flying buttresses, the walls could be pierced at frequent intervals. The light filtering into these Gothic interiors became a metaphor for Divine Light, replacing the Romanesque emphasis on Mystery.

Building Batalha

Batalha’s construction can be divided into three distinct stages.

1. During the first phase (1388–1438) the central nave, with simple ribbing supporting the vault, was built. The Founder’s Chapel and the chapterhouse vault have a greater refinement and elegance, influenced by English Gothic. Contact with England was close at this time as João I’s wife, Philippa of Lancaster, was the daughter of John of Gaunt.

2. During the second stage, which lasted until 1481, a second cloister was built.

3. The Manueline phase culminated in the Arcade of the Unfinished Chapels and the Royal Cloister.

The first building in Portugal to use these new construction methods was the majestic church of the abbey of Alcobaça, commissioned by Afonso Henriques. With its great height and elegant, unadorned white interior bathed in a milky light, Alcobaça is one of the most serene and beautiful churches in Portugal. Begun in 1178 and consecrated in 1222, it is almost purely French in inspiration: its plan echoes that of Clairvaux, the seat of the Cistercian Order in Burgundy – a nave and two side aisles of almost the same height, a two-aisled transept, and an apse whose ambulatory fans out into chapels.

The apogee of the national Gothic style came after the Portuguese armies defeated the invading Castilians at the Battle of Aljubarrota. In fulfilment of a religious vow João I commissioned the construction in 1388 of the Dominican Monastery of Santa Maria da Vitória (St Mary of the Victory), better known as Batalha, which simply means battle.

The stylistic influence of Batalha is seen in various churches throughout the country, such as the cathedral at Guarda and the now-ruined Carmo church in Lisbon, which were both begun at the end of the 14th century.

Generally speaking, Portuguese Gothic leaned towards temperance rather than flamboyance, a reflection of the austerity imposed by the mendicant orders and, perhaps, the sombre streak in the national character.

A portal in the lovely Gothic abbey at Alcobaça.

Mark Read/Apa Publications

The exhilaration of Portugal’s overseas discoveries had a marked effect on art, architecture and literature. The term “Manueline’’ was first used in the 19th century to refer to the reign of Manuel I (1495–1521), during which Vasco da Gama reached the coast of India (1498), and Afonso de Albuquerque conquered the Indian city of Goa (1510). The term is now used more often to refer to certain stylistic features predominant during the Avis dynasty (1383–1580), especially in architecture.

Manueline architecture does not have major innovative structural features – the twisted columns, such as those at the Church of Jesus in Setúbal, perform the same function as do plain ones. Rather, Manueline can be seen as heterogeneous late Gothic, its real innovation lying in its stone decoration, the exuberance of which reflects the optimism and wealth of the period. Inspired by the voyages to the New World, it is ornate and imposing, uniting naturalistic maritime themes with Moorish elements and heraldic motifs: during the reign of Manuel I, the king’s own emblems are usually included – as they were in the churches built in the newly discovered overseas territories.

The graceful cloister of Jerónimos Monastery.

Fotolia.com

The Monastery of Santa Maria de Belém in Lisbon, better known as Jerónimos, is one of the great hall churches of the period – that is, a church whose aisles are as high as its nave. Perhaps the most notable feature of Manueline architecture is the copious carving that surrounds portals and semicircular windows. The imposing southern portal of Jerónimos, together with the window of the chapterhouse at the Convent of Christ in Tomar, well deserve the acclaim they both receive. Construction on the Tomar window began much earlier, in the 12th century, along with the Templar Charola – a chapel with a circular floor plan. During the 16th century, the convent buildings, including four cloisters, were added. The lavish Manueline decoration of the church culminates in the famous window, designed with two great ship’s masts on either side, covered with carvings, topped, like the southern portal at Jerónimos, by the cross of the Order of Christ.

Manueline architecture also adopted and modified certain Moorish (morisco) features. At the Palácio Nacional at Sintra, restored during Manuel’s reign, morisco features include the use of tiles, merlons, and windows divided in two by columns. Another important morisco feature is the horseshoe arch, as in the chapterhouse of the Convent of Lóios in Évora. In Alentejo, many provincial palaces have morisco decoration, including latticework ceilings and chimneys.

Renaissance and Mannerism

The Renaissance has been described as a narrow bridge crossed the moment it was reached. This was certainly the case in Portugal. In their art and architecture, the Portuguese shied away from Renaissance rationalism, instead inclining towards naturalism or the drama of the Baroque.

The Renaissance in Portugal, then, was best represented by foreign artists. Foreign sculptors were frequently invited to decorate the portals and facades of Manueline buildings, introducing elements of Renaissance harmony and order within the general flamboyance of the Manueline decorative scheme. The coincidence of Manueline and Renaissance influences, and later of Renaissance and Mannerist forms, explains the hybrid style prevalent during this period. Mannerism uses elements of Renaissance classicism but the sense of an ordered, harmonious whole gives way to an exaggeration of these elements.

The Spaniard Diogo de Torralva is thought to have been responsible for one of the finest examples of Renaissance design in the Iberian peninsula – the Chapel of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of the Conception) in Tomar (c. 1530–40), with its simple exterior and diffusely lit, barrel-vaulted interior. Also in Tomar, Torralva’s Great Cloister at the Convent of Christ evokes the balance and harmony of Palladian classicism. Many years after Torralva’s death in 1566, this majestic cloister was completed by the prestigious Italian architect Filippo Terzi, a specialist in military architecture who had been invited by Felipe II of Spain (who became king of Portugal in 1581).

Azulejos adorn a facade in Alfama, Lisbon.

Mark Read/Apa Publications

Painted ceramic tiles called azulejos are a major feature of Portuguese architecture, with their use reaching its apex in the 17th century (for more information, for more information, click here).

Baroque

The Baroque is considered to be the stylistic range which, although it uses a basic classical vocabulary, strives for dissolution of form rather than definition. Emphasis is given to motion, to the state of becoming rather than being. This obliteration of clear contours – whether by brushstrokes in painting or as an optical illusion in sculpture and architecture – is further enhanced by a preference for depth over plane. These features all stress the grand, the dynamic and the dramatic.

The first truly Baroque Portuguese church is Santa Engrácia in Lisbon, with its dome and undulating interior walls. This building, begun in 1682, was not completed until 1966. The richness of the coloured marble lining the walls and floor, the dynamic interior space, and the general sumptuousness of the edifice are typical of construction during the reign of João V (1706–50), known as João o Magnânimo.

The wealth from Brazil and the extravagance of João V made the early 18th century a period of great opulence. He was the king who commissioned the Chapel of St John the Baptist at the Church of São Roque in Lisbon. The entire chapel was built in Rome, blessed by the Pope, shipped to Lisbon and reassembled in the church, where it shines with bronzes, mosaics, rare marble and precious stones.

In the north of the country the major centres for the development of the Baroque were Porto and Braga. Here, the influence of the Tuscan architect-decorator Nicolau Nasoni, who came to Portugal in 1725, predominated. He introduced a greater buoyancy and elegance, and rich contrasts of light and shade, and incorporated local characteristics as well. His elliptical-naved Church of Clérigos in Porto had no successor but his secular buildings, such as the Freixo Palace in the same city, with their interplay of whitewash and granite, established a large following.

The gleaming Basilica da Estrêla in Lisbon, dating from the 1780s and commissioned by Maria I, was the last church to be built in the Baroque Grand Style. By then, architectural styles had moved on and, with the dissolution of the monastic orders in 1834, religious architecture lost its privileged position in Portugal.

The entrance to Bom Jesus de Braga.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Rococo

In the rococo style, drama was replaced by fantasy, and an emphasis on flourish, sensuality and ornamentation. The chapel of Santa Madalena in Falperra is a good early example of the style. Rococo was also marked by a growing interest in landscaping. The type of church represented by Bom Jesus in Braga became popular: surrounded by gardens, it sits on the top of a hill and is reached by a sweeping succession of stairways which from a distance seem to cascade downward.

In Lisbon the rococo was more sober than in the north. After the earthquake of 1755, Carlos Mardel designed many of the city’s public fountains in a toned-down version of rococo, including those of Rua do Século and Largo da Esperança. Mardel was also responsible for part of the Aguas Livres Aqueduct, which withstood the earthquake, and is still a familiar landmark.

Grand arch in the Baixa of “Pombaline Lisbon”.

Phil Wood/Apa Publications

Neoclassicism

Although it took place at much the same time, the Pombaline style of the reconstruction of Lisbon (see box, click here) is closer in many respects to classical models than to the rococo constructions in the north. The neoclassical style proper, with its emphasis on Greco-Roman colonnades and porticoes, was introduced to Lisbon in the last decade of the 18th century. It received court approval when used for the Royal Palace of Ajuda (begun in 1802 and never completed), after a fire destroyed the wooden building that had been the temporary royal residence since the earthquake.

After this, perhaps the only noteworthy public building to be built in Lisbon in the first half of the 19th century was the Theatre of Dona Maria II (1843), with its white Greco-Roman facade. The dissolution of the monasteries had a negative effect on the development of public buildings, as well as on religious architecture.

The middle-class ambience of Porto proved fertile ground for conservative neoclassicism. It was favoured by the English community connected with the port industry, perhaps because of affinities with the work of Scottish architect Robert Adam (1728–92). British consul Sir John Whitehead commissioned the Feitoria Inglesa in Porto and the Hospital of Santo António, perhaps the finest neoclassical buildings in the country.

Pombal’s Project

The reconstruction of Baixa, the lower city of Lisbon, which the Marquês de Pombal embarked on after the devastating earthquake of 1755, was the most ambitious urban planning scheme ever seen in Europe, and serves as the statesman’s lasting memorial. “Pombaline Lisbon”, as it is known, is built on a grid system, with clean, uncluttered lines. The area is epitomised by the Praça do Comércio, the huge square bounded on three sides by neoclassical arcades. In the centre stands a large equestrian statue to José I, erected in 1755. The majestic triumphal arch, however, was not completed until the 1870s, long after Pombal’s death.

Romanticism

If neoclassical art and architecture represented an escape from the turmoils of the present into a restrained, harmonious classical ideal, another form of escapism was an important ingredient of Romanticism. It was typified by flights into medievalism and orientalism, or into altered states of dreams and madness.

The most extraordinary architectural manifestation of this was the Pena Palace in Sintra (commissioned around 1840 by Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the consort of Maria II). The building is a strange mix of medieval and oriental forms, including Manueline, Moorish, Renaissance and Baroque, and incorporating parts of the site’s original structure – a 16th-century monastery. The result is a pastiche of English Gothic revivalism.

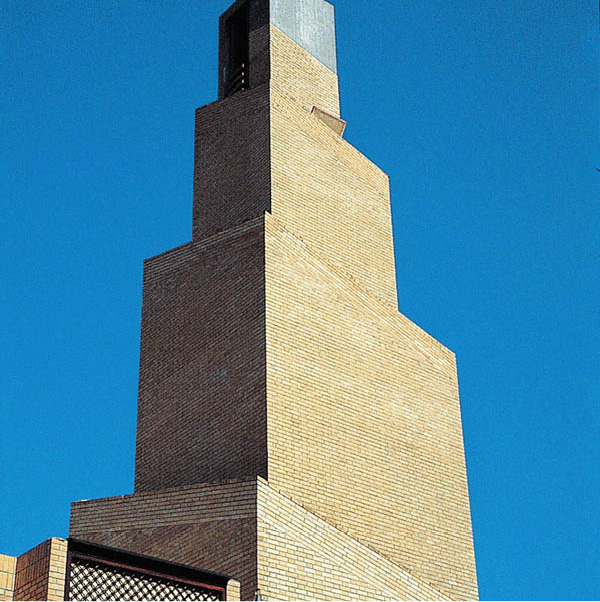

Portugal has modern landmarks, too, such as the mosque in Lisbon’s Avenidas Novas.

Phil Wood/Apa Publications

Modern styles

One of the best examples of Portuguese architecture from the first half of the 20th century is the Art Deco Casa Serralves in Porto (now a museum), but there are also many gorgeous Art Nouveau cafés in Lisbon and Porto. Under Salazar, the fashion was for brutalist Soviet-style blocks, with exceptions such as the pared-down aesthetic of the Gulbenkian Museum. More recently, Porto architects such as Fernando Távora and Alvaro Siza Viera have established solid reputations: the rebuilding of the Chiado district after Lisbon’s 1988 fire was entrusted to the latter, who also designed Porto’s beautiful Museu de Arte Contemporânea (for more information, click here).

The postmodernist work of Tomás Taveira is also notable in Lisbon, particularly his office towers at the Amoreiras (for more information, click here). And Expo ’98 was a launching pad not only for some stunning modern pavilions and Europe’s longest bridge, the Ponte Vasco da Gama (for more information, click here), but also a clear, uncluttered building style across Portugal. A prime example is Rem Koolhaas’ Casa da Música in Porto, which mixes minimalist Modernism with traditional elements, such as azulejos. Close to Obídos, the spectacular Bom Sucesso development is a collection of villas and leisure facilities designed by star architects including Alvaro Siza Viera. The most breathtaking new addition to the contemporary architecture landscape is the Museu do Côa, in the Douro, a monolithic triangular block, all concrete walls and sharp angles, designed by Porto architects Pedro Tiago Pimentel and Camilo Rebelo.

Sumptuous carvings at Lisbon’s Estação do Rossio train station.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications