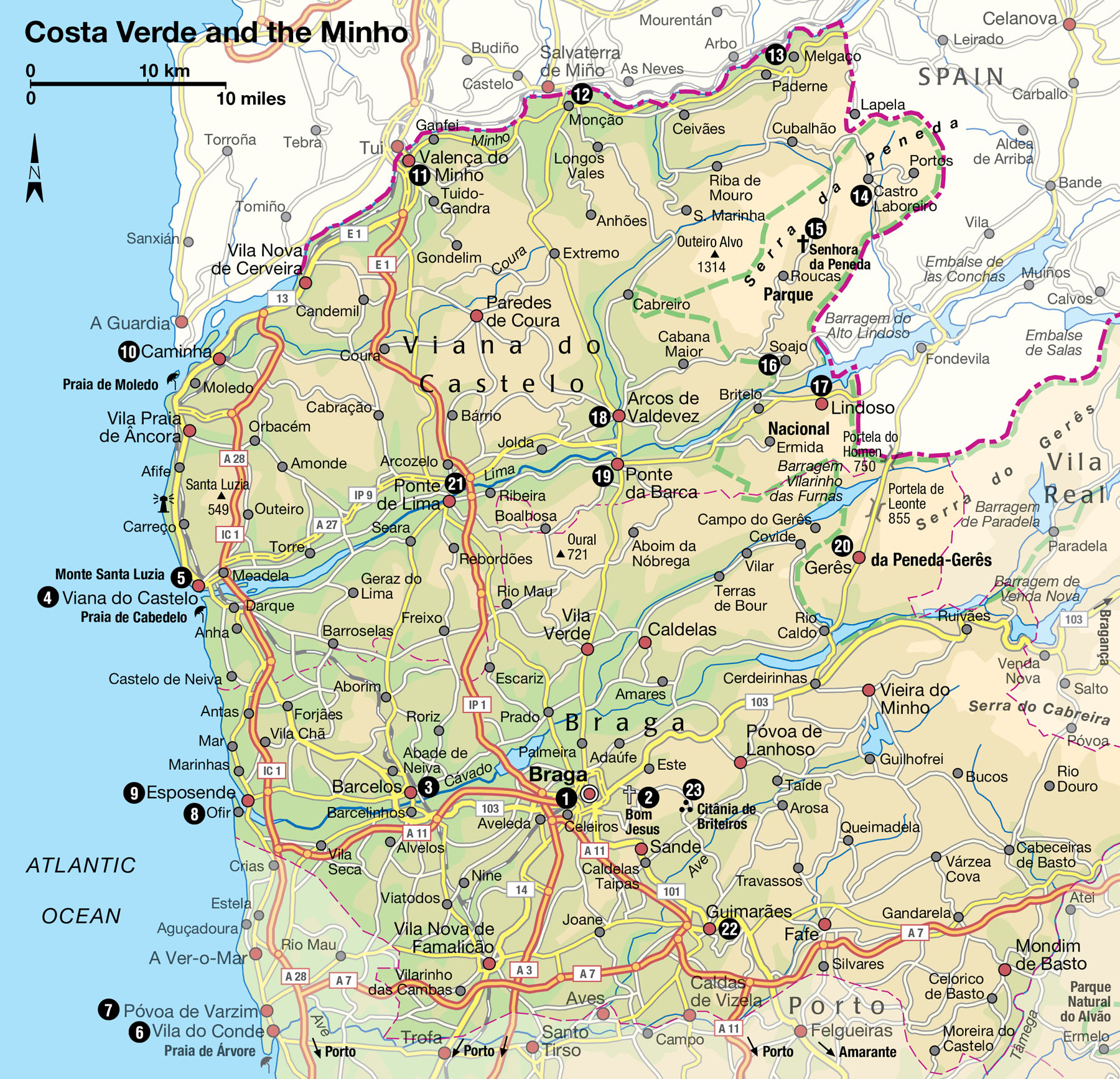

Costa Verde and the Minho

Verdant and lush, this is a land of vineyards, tranquil riverside towns, busy markets, and a great European wilderness: the Peneda-Gerês National Park.

Main Attractions

The Minho region north of Porto is often described as Costa Verde, or the Green Coast, a reference to the vineyards and lush green of its well-watered landscape. In reality it is a much larger area than just the coast. It extends northwards to the Rio Minho, the boundary with Spain, eastwards to include the Parque Nacional da Peneda-Gerês and south to encompass Braga and Guimarães. It is a region of great natural beauty, especially the verdant Lima Valley and the wild and mountainous Peneda-Gerês, where farming techniques and lifestyles pass from generation to generation with relatively little change.

Grapes are grown everywhere. They hang from trees, pergolas and porches, and climb along slopes and terraces. They grow in poor rocky soil where little else flourishes. To get the most out of the land, the Minhotos train their vines to grow upwards, on trees, houses and hedges, leaving ground space for cabbages, onions and potatoes. This freewheeling system made it difficult to modernise grape production, but for many years the larger vineyards have been using a system of wire-supporting crosses called cruzetas.

The vindima, or grape harvest, is still done by hand and is a wonderful sight to behold. Harvesting takes place in September and October and lasts until early November. It can be a hazardous task, requiring towering 30-rung ladders to get at the elusive treetop grapes, although most vines now are trained at tractor height. In the hilly country, men still carry huge baskets of grapes weighing as much as 50kg (110lb) on their backs. On some back roads, squeaky ox-carts transport the grapes to wine-presses. In these modern times, however, the fruit is generally transported in trucks.

Decorations for the Braga folklore festival.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

While harvest is still a festive occasion, it no longer involves quite the unbridled merrymaking of yore. In the old days, workers used to perform a kind of bacchanalian dance, their arms linked, stamping on the grapes with their bare feet. It was said that this was the only way to crush the fruit without smashing the pips and spoiling the flavour of the wine. This was often accompanied by music and clapping, glasses of spirits and a good deal of sweat. Nowadays, mechanical extractors often remove the pips, and presses are generally used to crush the grapes, although treading still takes place in a few vineyards.

There is a second style of agriculture here which is even more distinctive and unique to this region of Portugal. It is known as dune agriculture, and involves digging small depressions in the actual sand dunes, which then capture the moisture from the sea mist and protect the crops from the sometimes strong winds. These sandy allotments are traditionally fertilised by dried seaweed, which many people believe contributes to the consistently high quality of the produce that is grown here. The seaweed is harvested in early autumn, collected by enormous nets and then spread out to dry in the sunshine.

Tip

The Comissão de Viticultura da Região dos Vinhos Verdes in Porto can provide information on vinho verde wine routes and estates to visit (tel: 226 077 300; http://rota.vinhoverde.pt).

Grapevines growing in Minho.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Braga

Some people still refer to Braga 1 [map] somewhat wistfully, as “the Portuguese Rome”. In Roman times, as Bracara Augusta, it was the centre of communications in north Lusitania. In the 6th century two synods were held here. Under Moorish occupation, Braga was sacked and the cathedral badly damaged, but in the 11th century the city was largely restored to its former eminence by Bishop Dom Pedro and Archbishop São Geraldo. The archbishop claimed authority over all the churches of the Iberian peninsula, and his successors retained the title of Primate of the Spains for six centuries.

Like a Renaissance prince, one of his successors, Archbishop Dom Diogo de Sousa, encouraged the construction of many handsome Italian-style churches, fountains and palaces in the 16th century. Zealous prelates restored many of these works in the subsequent two centuries, but often with unfortunate results. Braga lost its title as ecclesiastical capital in 1716, when the patriarchate went to Lisbon. But it is still an important religious centre, and the site of Portugal’s most elaborate Holy Week procession.

A visit to Braga usually begins at the Sé (Cathedral; daily Apr–Oct 8.30am–6.30pm, Nov–Mar 8.30am–5.30pm), which was built in the 11th century on the site of an earlier structure destroyed by the Moors. Of the original Romanesque building there remains only the southern portal and the sculpted cornice of the transept. Although it has been greatly modified by various restorations, the cathedral is still imposing. The interior contains some fine tombs, including those of the founders, Count Henri and his wife Teresa, a granite sculpture of the Virgin, an 18th-century choir loft and organ case, and richly decorated chapels and cloister.

Of particular interest is the Tesouro da Catedral (Cathedral Treasury; Tue–Sun Apr–Oct 9am–12.30pm, 2–6.30pm, Nov–Mar 9am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm), with a fine collection of 15th-century vestments and silver chalices and crucifixes dating from the 10th and 12th centuries.

Nearby, with plain west walls set off by an 18th-century fountain, is the Palácio de Arzobispo (Archbishop’s Palace), built in the 14th century and reconstructed several times. The palace now houses the Public Library, with city archives dating back to the 9th century, 300,000 volumes and 10,000 manuscripts. On the western side of Praça Agrolongo stands one of Braga’s Rome-inspired churches, Nossa Senhora do Pópulo, built in the 17th century and remodelled at the end of the 18th. It is decorated with azulejos depicting scenes from the life of St Augustine.

The Palácio dos Biscainhos (Tue–Sun 10am–12.15pm, 2–5.30pm) just across the way is a 17th-century mansion with lovely gardens and fountains. It houses the municipal museum with an impressive collection that includes 18th-century tiles, ceramics, jewellery and furniture.

The city has been digging into its past in recent years and uncovered such riches as Roman baths, a sanctuary called Fonte do Idolo and the remains of a house: Domus de Santiago. An archaeological museum, the Museu Dom Diogo de Sousa (http://mdds.imc-ip.pt; Tue–Sun 10am–5.30pm) displays the finds, with fascinating exhibits, including mosaic flooring dating from the 1st century AD. The museum is a short walk from the ruins of the above-mentioned Termas Romanas (Tue–Fri 9am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 11am–5pm), dating from the 2nd century AD.

On the northern side of the city, the church of São João de Souto was completely rebuilt in the late 18th century. But here you will find the superb Capela do Conceição, built in 1525, with crenellated walls, lovely windows and splendid statues of St Anthony and St Paul.

The grand stairway of Bom Jesus.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Bom Jesus

There are many other churches and chapels of interest in the centre, but the best known is Santuário Bom Jesus 2 [map] (daily 8am–8pm; free) which is conspicuously set on the wooded Monte Espinho, about 5km (3 miles) outside Braga. This popular pilgrimage centre is remarkable for its grandiose Baroque stairway and the view from its terrace of the Rio Cávado valley with the mountains in the distance. The double flight of stairs is flanked by chapels, fountains and often startlingly bizarre figures at each level, representing the Stations of the Cross.

If you don’t wish to climb the steps, there is a funicular (daily 8am–8pm) and a winding road to the top. There, among oak trees, eucalyptus, camellias and mimosa, stands the 15th-century church, rebuilt in the 18th century. In its Capela dos Milagres (Chapel of Miracles) are votive offerings and pictures left by past pilgrims. Several hotels, souvenir shops and restaurants are also located in the vicinity of the sanctuary.

Barcelos: cock and bull

Just northwest of Braga is the charming market town of Barcelos 3 [map], on the north bank of the Rio Cávado. Barcelos has 15th-century fortifications, a 13th-century church and a 16th-century palace, but more than that, it has one of the best markets in the country. Every Thursday, traders and artisans display their crafts, textiles and other goods in the centre of town. There are also plenty of food stalls to ensure you won’t go hungry.

It was here that the late Rosa Ramalho, the most famous folk-art sculptress in Portugal, created her world of fanciful ceramic animals and people – a style that has been continued by her granddaughter. Head to the Centro de Artesanato de Barcelos (Rua Dom Diogo Pinheiro 25) to browse local crafts. It displays copperware, handmade rugs, wooden toys, bright cotton tableware, and, of course, the galo de Barcelos – the ubiquitous Barcelos cockerel.

An old gate in Braga.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

A monument, the so-called Senhor do Galo cross, is the most apt reminder of the extraordinary legend that lies behind the rooster’s elevation to Portugal’s unofficial national emblem (for more information, click here). There is an excellent pottery museum, the Museu de Olaria (www.museuolaria.org; Tue–Sun 9.30am–noon, 2–5pm), featuring traditional ceramics and pottery from all over the country, including the Azores.

Traditional dancing in Viana do Castelo.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Viana do Castelo

A lively fishing and shipbuilding port at the mouth of the Rio Lima, Viana do Castelo 4 [map] was called Diana by the Romans. This was the centre of Portugal’s wine trade until the port declined in the 18th century and Porto became pre-eminent. There is a good deal to see in the centre of Viana, as well as beyond: the town is home to several of the region’s most enticing sweeps of sand. In the central Praça da República there is a beautiful 16th-century fountain and the remarkable Misericórdia hospital, with a three-tiered facade supported by caryatids. There is also a museum here, the Museu do Traje (Costume Museum; Tue–Sun June–Sept 10am–1pm, 3–7pm, Oct–May 10am–1pm, 2–6pm), with two floors of colourful traditional costumes. Nearby stands the handsome 15th-century parish church with a Gothic portal and Romanesque towers.

Capela das Malheiras chapel, Viana do Castelo.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The town is dominated by Monte Santa Luzia 5 [map] , with a large and inappropriate modern basilica. To get here, hop on the funicular railway (daily 8am–dusk). Alternatively, energetic souls can climb the stairs just past the hospital. To the west of the town, the Baroque Nossa Senhora da Agonia church is the site of a popular pilgrimage each August. Dancers, musicians and other celebrants, wearing vivid embroidered traditional costumes, come from all over the Minho to take part in the three-day festa, which is among Portugal’s most spectacular.

Moving to the waterfront you come to the Gil Eannes (www.fundacaogileannes.pt; Apr–Sept 9am–7pm, Oct–May 9am–5.30pm), a former naval hospital ship, now a floating museum dedicated to the ship’s former function, which was mainly servicing the cod fishermen in Greenland and Newfoundland. Part of the ship is now also used as an unusual youth hostel.

Across the river is the enticing Praia de Cabedelo beach, accessible via a five-minute ferry ride from the harbour (hourly May–Sept). There are more good beaches nearby, including at the small resort of Carreço, just 5km (3 miles) to the north.

Coastal route from Porto

An alternative route into the Minho is by driving up the coast from Porto and returning by the inland route. The Atlantic beaches are generally broad, with fine sand, but the sea is cold and rough. A fishing town and resort, Vila do Conde 6 [map] , is the site of the vast Convento de Santa Clara, which was founded in 1318, the 16th-century parish church of São João Baptista and a lovely 17th-century fortress. Travellers are welcome to watch how fishing boats are made and to visit the lace-making school and museum, the Museu das Rendas de Bilros (Tue–Sun 10am–noon, 2–6pm; free). Nearby, Póvoa de Varzim 7 [map] is another popular fishing port-resort, with an 18th-century fort and a parish church. There is also a casino and a modern luxury hotel, the Axis Vermar, with heated swimming pools and tennis courts. Further north, Ofir 8 [map] is a delightful seaside resort set amid pine forests. Just across the Rio Cávado lies the town of Esposende 9 [map] with the remains of an 18th-century fortress. There are many new, often garishly painted, houses in towns and villages along the way, which have often been built by emigrants returned from France, Germany and elsewhere.

Fact

Walk or cycle along the Ecopista, heading east from Valença to Cortes (13km/8 miles). This former railway track has been converted to a signposted paved pathway and is flanked by beautiful countryside, including bubbling streams, vineyards and mountains.

Along the Rio Minho

Continuing northwards, beyond Viana do Castelo, the road leads to Caminha ) [map] on the banks of the Rio Minho, an attractive town with echoes of its past as a busy trading port. The church, dating from the 15th century, has a beautiful ceiling of carved wood. There are several lovely 15th- and 16th-century buildings near the main square.

At the estuary of the Minho, the road turns inland and follows the river, which forms the border with Spain. Valença do Minho ! [map] is a bustling border town with shops and markets. Spaniards come here regularly to purchase items that include table linen and crystal chandeliers. The Portuguese, on the other hand, cross the border to Tui or Vigo to buy canned goods such as asparagus and artichokes, as well as clothing. The old town of Valença is still fairly intact, with cobbled streets and stone houses with iron balconies, surrounded by 17th-century granite ramparts. The ancient convent, with a splendid view of the Minho and of Spain, is now a pousada.

From Monção @ [map] , a fortified town known for its spring water and classy vinho verde, you can either take the road south through the heart of the Minho, or continue along the riverside and cross over the mountains of Serra da Peneda and sense the isolation. Either way, the routes meet at Ponte da Barca.

The unusual grain stores of Soajo.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The mountain route

Follow the river as far as Melgaço £ [map] , another fortified town, and turn inland for Castro Laboreiro $ [map] , an ancient settlement with an 11th-century castle, which is most renowned for a large breed of working dog that was introduced to protect the villagers from marauding wolves.

Take the road from here to Senhora da Peneda % [map] to find an amazing Bom Jesus-style church, in the middle of nowhere. A long flight of steps ascending to the church is adorned with 14 chapels, each containing a tableau depicting a major event in the story of Christ.

Dramatic mountain scenery opens up as you pass through a number of villages, including Rouças and Adrão, to meet the road outside the village of Soajo ^ [map] , where there is a colourful market on the first Sunday of the month. Of particular interest here are the communal espigueiros, granite grain stores built on mushroom-shaped legs, and grouped around a threshing floor.

The road onward leads southeast to Lindoso & [map] (the name comes from lindo meaning beautiful) and a finely situated border castle keeping watch for invaders from Spain. Below the castle ramparts lies another cluster of espigueiros. Return from Lindoso on the road to Ponte da Barca. You will see lush countryside, crisscrossed by rivers with medieval stone bridges; simple white churches with elaborate granite doorways and windows; and, of course, unending vineyards. Due to the high population density, the land has been divided and subdivided for generations, so the average property now consists of just a hectare or two.

The road now passes Arcos de Valdevez * [map] , an attractive hillside town built on the banks of the Rio Vez, with a magnificent view of the valley. Just to the south, Ponte da Barca ( [map] , on the south bank of the Rio Lima, has a lovely 15th-century parish church and an old town square, but the principal attraction is the fine arched bridge, after which the town is named, built in 1543 and often restored.

Enjoying watersports in the national park.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

This is a possible starting point for a visit to the stunning Peneda-Gerês National Park (for more information, click here for a suggested route). Covering a vast 703 sq km (272 sq miles), the park encompasses wild plains with grazing cattle, pine-clad mountain ranges and lush forests. It is the wettest region of Portugal, and there are streams and rivers and a flourishing plant life with some 17 species found nowhere else, as well as extensive forests of oak and pine. Wild ponies, deer, wolf, golden eagles, wild boars and badgers also live within the boundaries.

The park encompasses fascinating ancient villages with stone houses, cobbled streets and a predominance of elderly women dressed in black. You may fish, go horse riding, hike and mountain climb amid the breathtaking scenery. There are also dolmens, perhaps 5,000 years old, and milestones that once marked the old Roman road to Braga.

Parque Nacional da Peneda-Gerês

It is easy to make a round trip of the Peneda-Gerês National Park by car, taking in some of the most spectacular scenery on both sides of the border. From Ponte da Barca take the road east towards Lindoso, past the hydro scheme to the border at Madaleina. Cross into Spain – there are no formalities – and continue alongside the reservoir until you come to a right turn signposted Lobios and Portela do Homen. Take this turn and you eventually cross back into Portugal.

On the Portuguese side you have a choice: continue straight down the “main” road to the old spa town of Caldas do Gerês then towards Braga, or, shortly after crossing back into Portugal, take the right turn down the road which follows the Vilarinho reservoir to Campo do Gerês, which has an excellent visitor centre portraying traditional life in Vilarinho das Furnas, the village submerged by the reservoir. Then drive towards Covide, passing a well-stocked craft shop, then west to Vila Verde. Of the two options, the latter is the more interesting. Roads can get very busy at weekends in summer, and at peak times the park authority may impose traffic restrictions.

If you plan on camping in the national park, be sure to use a designated site, or you could be faced with a hefty fine. Tourist offices have lists of official sites which are, generally, of a very high standard.

The bustling, central little spa town of Vila do Gerês ‚ [map] (also called Caldas do Gerês) has plenty of places to stay and a popular spa centre (May–Oct). There are also some good hiking trails surrounding the town; detailed maps are available at the tourist office. Nearby, tiny Rio Caldo is the park’s centre for water sports, including kayaking, waterskiing and rowing.

The Roman bridge at Ponte de Lima.

Pictures Colour Library

The Lima valley and the south

Here you might turn westwards, along the beautiful valley of the Lima River, which the Romans believed to be the Lethe, the mythical River of Forgetfulness. The area has numerous great estates or solares, which stand as a tangible reminder of the glories of the old empire. Some are now guesthouses, and arrangements to visit or stay in these manors should be made beforehand, if possible (for more information, click here).

Ponte de Lima ⁄ [map] is one of the loveliest towns in Portugal, mainly because of its location on the south bank of the Lima and its picturesque historic centre. There is a popular market, held every other Monday, resembling a splendidly colourful “tent city” on the river bank. It sells everything from local cheese to cotton underwear.

The town faces a magnificent Roman bridge with low arches, and remains of the old city wall still stand. A 15th-century palace with crenellated facade now serves as the town hall. Across the river, the 15th-century Convento de Santo António has beautiful woodwork, including two Baroque shrines.

Continuing towards Viana do Castelo, you pass more manor houses, such as the Solar de Cortegaça, with its great 15th-century stone tower. This is a working manor, with wine cellars, a flour mill and stable. Guests are welcome to take part in the farm life (tel: 258 971 639).

Guimarães is famous for its medieval historic monuments.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Guimarães: birthplace of a nation

A busy manufacturing town noted mainly for textiles, shoes and cutlery, Guimarães ¤ [map] ill possesses many reminders of its past glory as birthplace of the Portuguese nation. Around the year 1128, an 18-year-old boy named Afonso Henriques proclaimed independence for the region of Portucale from the kingdom of León and Castile. In the field of São Mamede, near Guimarães, the young Afonso Henriques defeated his mother’s army, which was battling on behalf of Alfonso VII, king of León and Castile.

Guimarães has long been the centre of the Portuguese linen industry. It still produces high-quality, coarse linen from home-grown flax naturally bleached by the sun. The region is also known for its hand embroidery.

A good place to begin a tour is at the 10th-century castelo (daily 10am–6pm), on the northern side of town. It is believed that Afonso Henriques was born here in 1110, the son of Henri of Burgundy, Count of Portucale, and his wife Teresa. The castle is a large mass of walls and towers on a rocky hill with a magnificent view of the mountains. The dungeon and fortifications were restored many times. Early in the 19th century, the castle was used as a debtors’ prison; it was restored again in 1940. At the entrance stands the small Romanesque chapel of São Miguel do Castelo with the font where Afonso Henriques was baptised in 1111.

Fact

Guimarães’ Festival of St Walter, the Festas Gualterianas, dates from the middle of the 15th century. This three-day celebration, on the first weekend in August, includes a torchlight procession, a fair with traditional dances, and a medieval parade.

Heading into town, you pass the 15th-century Gothic Paço dos Duques de Bragança (daily 10am–6pm), now occasionally used as an official residence by the president of the Republic. This massive granite construction consists of four buildings set around a courtyard and has been completely restored. Outside stands a fine statue of Afonso Henriques by Soares dos Reis. Visitors may also view the splendid chestnut ceiling of the Banquet Hall, the Persian carpets, French tapestries, ancient portraits and documents.

The Rua de Santa Maria, with its cobblestones and 14th- and 15th-century houses, leads to the centre of town. On the left lies the Convento de Santa Clara, built in the 1600s and now used as the town hall.

The church of Nossa Senhora de Oliveira, dating from the 10th century, was rebuilt by Count Henri in the 12th century and has undergone several restorations. Still visible are the 16th-century watchtower and 14th-century western portal and window. The church takes its name from a 7th-century legend of an old Visigoth warrior named Wamba who was tilling his field nearby when a delegation came to tell him he had been elected king. Refusing the office, he drove his staff into the ground, declaring that not until it bore leaves would he become king. It turned into an olive tree and the church was later built on the spot.

Adjacent to the church of Oliveira, the convent now holds the Museu de Alberto Sampaio (http://masampaio.imc-ip.pt; Tue–Sun July–Aug 10am–midnight, Sept–June 10am–6pm), displaying the church’s rich treasury of 12th-century silver chalices and Gothic and Renaissance silver crucifixes, as well as 15th- and 16th-century statues, paintings and ceramics.

The busiest square in Guimarães is the Largo do Toural. Just beyond, the Igreja São Domingos was built in the 14th century and still has the original transept, rose window and lovely Gothic cloister. The latter houses the Museu Arqueologico Martins Sarmento (Tue–Sat 9.30am–noon, 2–5pm, Sun 10am–noon, 2–5pm), named after the man who was responsible for the excavation of the Citânia de Briteiros (for more information, click here) and displaying objects from that site and other citânias (ancient Iberian fortified villages) of northern Portugal, as well as collections of Roman inscriptions, ceramics and coins.

Continuing along the broad garden called the Alameda da Resistência ao Fascismo, you reach the Igreja São Francisco, founded in the 13th century. There is little left of the original Gothic structure, but the sacristy has impressive 17th-century gilt woodwork and ceiling, as well as some striking azulejos.

High on the outskirts of the city stands Santa Marinha da Costa, founded as a monastery in the 12th century and rebuilt in the 18th century. The church functions regularly and may be visited. The cells of the monastery, which were badly damaged by fire in 1951, have been restored and turned into a luxury pousada (one of two pousadas in the town; for details, check www.pousadas.pt). A 10th-century Mozarabic arch and vestiges of a 7th-century Visigothic structure are visible in the cloisters, and the veranda is decorated with magnificent 18th-century tile scenes and a fountain.

Restored houses of the ancient settlement Citânia de Briteiros.

Alamy

Citânia de Briteiros

After the Briteiros exhibit at the Martins Sarmento museum, you could visit the original site, 11 km (7 miles) north of Guimarães. At first, the Citânia de Briteiros ‹ [map] (daily 9.30am–6.30pm) appears to be nothing more than piles of stones on a hillside, but it is in fact one of Portugal’s most important archaeological sites. Here are the remains of a prehistoric fortified village said to have been inhabited by Celts. It was discovered in 1874 by archaeologist Francisco Martins Sarmento.

Near the summit, two round houses have been reconstructed. Also visible are the remains of defensive walls, ancient flagstones and the foundation walls of more than 150 houses. The houses were circular with stone benches running around the walls. A large rock in the centre supported a pole which would in turn have held up a thatched roof. Several of the houses are larger, with two or more rectangular rooms, presumably the homes of prominent members of society. The town evidently had an efficient water system: spring water flowed downhill through gutters carved in the paving stones to a cistern and a public fountain.

Traditional farming.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications