Ancient Lusitania

For centuries, successive waves of invaders swept over the peninsula. The Moors held on longest, even after Afonso Henriques became Portugal’s first king.

Portugal, with borders already established by the 13th century, is one of the oldest nations in Europe. Despite its small size, its impact on global history has been powerful and its influences visible in many places across the world. Over the centuries it has discovered and lost an empire, relinquished and regained its cherished autonomy and, since the 1974 revolution that ended decades of dictatorship, has formed new ties with some of its former possessions.

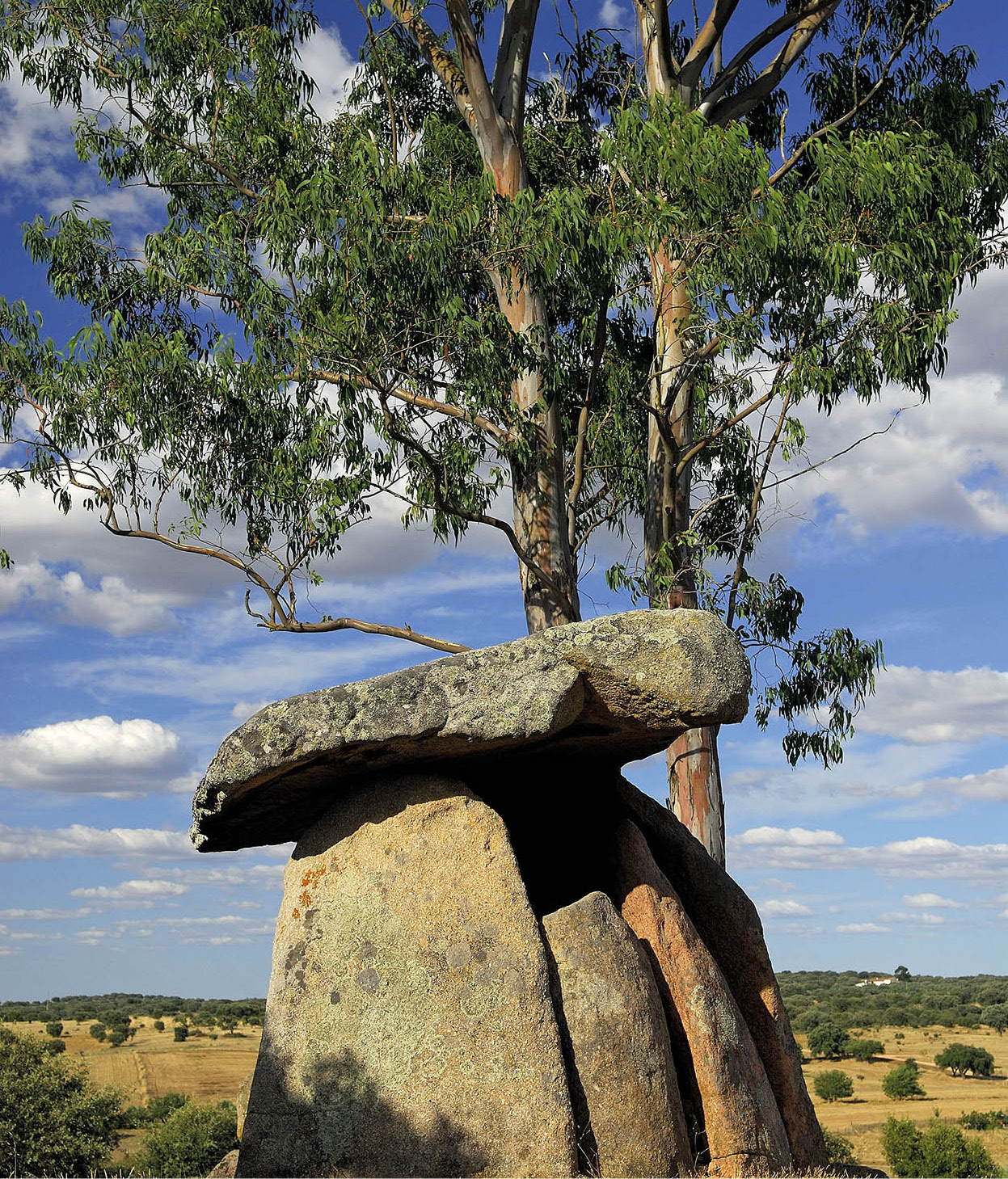

Anta da Coutada dolmen in Barbacena, in the Alentejo region.

Superstock

Cultural diffusion

A rich prehistoric culture has left its traces throughout Portugal. There is evidence of the earliest stages of human evolution and a large number of megalithic sites. The variety and quantity of these finds have led many scholars to a theory that cultural diffusion came primarily from overseas. Opponents of this notion point out that this is unlikely, as most of the megalithic sites are far from the coastline. They think the population grew via natural land routes of settlement which, unsurprisingly, correspond to the paths invaders have taken throughout Portugal’s history: across the Rio Minho from the north and over the Alentejo flatlands from the south.

The ancient standing stones at Almendres, Évora, is the largest existing group of structured menhirs in the Iberian Peninsula.

AWL Images

In any case, by the 2nd millennium BC, social organisation consisted of scattered castros – garrisoned hilltop villages that suggest warfare between tribes. The people subsisted on goat-herding and primitive agriculture, and clad themselves in woollen cloaks.

Evidence of 2nd millennium BC Portuguese society can be seen in the form of the constructions that still stand, for example at the Citânia de Briteiros near Guimarães.

In the south, tribes came under the influence of Phoenician trade settlements in the 9th century BC, and Greek ones in the 6th century BC, both on the coast and inland, where metals were mined. Only at this late point is there evidence of a significant fishing economy among the indigenous people. Perhaps before then the rough-hewn and storm-beaten Atlantic coast was too intimidating for their small boats. During the 5th century BC, the Carthaginians wrested control of the Iberian peninsula from these earlier traders, but lost it to the Roman Empire in the Second Punic War.

Wars of conquests

The Romans called the peninsula Hispania Ulterior. Here, as elsewhere in the empire, they combined their economic exploitation with cultural upheaval. They were not traders, after all, but conquerors, who set about the business of founding cities, building roads and reorganising territories. They also implemented governmental and judicial systems.

The locals resisted. The largest and most intransigent group were the Lusitani, who lived north of the Rio Tejo (Tagus), and after whom the region was given its name, Lusitania. Bitter guerrilla fighting was intermittent for two centuries. The most renowned rebel was a shepherd named Viriathus, who led uprisings until he was assassinated in 139 BC by three treacherous comrades who had been bribed by the Romans. It was during these wars of conquest that Roman troops are said to have refused to cross the Rio Lima, believing it to be the Lethe, the mythical River of Forgetfulness. Their commander, the story goes, had to cross the river alone, then call each soldier by name to prove that the dip had not affected his memory. The death of Viriathus took the heart out of the revolt, although the Lusitanian uprisings were not finally quelled until 72 BC.

In 61 BC, Julius Caesar governed the province from Olisipo (as Lisbon was then called). Cities were established and colonised at Évora, Beja, Santarém and elsewhere. Roads linked the north and south, and Lisbon became an important administrative centre, at the hub of the Romans’ local road network linking the major population centres. These centres and routes have waned in importance, but many – most notably the capital, Lisbon – are still geographic focal points.

Before their empire eventually fell, the Romans had infused the area with their language, legal system, currency, agriculture and, eventually, with Christianity. The organisation of latifundios – great, landed estates – was particularly significant as it brought large-scale farming to the area for the first time.

The Temple of Diana at Évora.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

With the conversion of the late Roman emperors (Constantine, who issued an Edict of Tolerance in AD 331, was the first Christian emperor), the tenets and organisation of Christianity spread throughout the fading empire. Bishoprics were established in a number of cities, Braga and Évora among them. As the church expanded, it usurped the administrative power that had been developed by the empire at the height of its strength.

Heretical Christian doctrines held sway in Portugal during the 3rd and 4th centuries. In the early 5th century various groups of barbarians occupied the land. The Alani and Vandals each settled for a short time, but by 419 the Suevi were in sole, if not steady, possession of Galicia, and from there they conquered Lusitania and most of the Iberian peninsula. The Suevi apparently assimilated easily with the existing Hispano-Roman population, but the tide turned with the fall of Rome and the arrival of the Visigoths.

For the next half century, military conquest inevitably meant religious conversion. In 448, Rechiarius, the king of a diminished Suevi empire, converted to Catholicism, perhaps hoping to elicit aid from Rome in battling against the Visigoths, who were nominally Christian but clung to vestiges of heretical beliefs. When Rechiarius was killed in 457, the Suevi kingdom survived, led by his son, Masdra. The latter’s son, Remismund, succeeded him and in 465 renounced Christianity, probably hoping to appease the Visigoths. But by 550, the growing power of the Catholic Church had produced a new round of conversions, led by St Martin of Dume. The remnants of the Suevi were politically extinguished in 585.

Invaders from the south

Visigoth rule, under an elective monarchy, was not seriously challenged until the Moors – Muslims from North Africa – arrived on the south coast in 711 and began their expansion northwards. The Moors were following the instructions of their leader, the Prophet Mohammed (who died in 632), to wage a holy war (jihad) against non-believers. However, like the Christian Crusades that followed (for more information, click here), their advances were increasingly concerned with empire building.

The Visigoths were defeated at the Battle of Jerez, and Lisbon soon fell into Muslim hands. Southern Portugal became part of Muslim Spain, loosely organised under the Córdoba caliph – caliphs were successors of the Prophet, regional rulers created under the Umayyad dynasty (650–749).

To the Moors, this land was known as Al-Gharb (the West), from which was derived the modern name Algarve. The Moors soon ruled all Portugal, and Christianity was forced north of the Minho, where it lay gathering strength for the reconquest – the Reconquista.

A nation in prospect

Stirrings of the Reconquista were believed to have started as early as 718 at Covadonga. Here in Asturias, the Christians defeated a small force of Moors. Galicia became a battleground over the next century and a half. The kings of Asturias-León made ever-increasing excursions into Galicia and beyond. Slowly, towns fell before the Christian armies: Porto in 868, Coimbra in 878, and by 955 the King of León, Ordona III, had engineered a raid on Lisbon. Most of the victories below the Douro, however, were transient ones, amounting to nothing more than successful raids, as the territory was seldom held for more than a season or two. Under the Emir of Córdoba, Muslims in Portugal lived in relative peace, introducing irrigation systems and water mills as well as wheat, rice, oranges and saffron. Shipbuilding was active, copper and silver mines were exploited, Roman roads expanded and towns were planned. There was religious tolerance and the arts flourished. Muslim stuccowork and glazed tiles, called azulejos, were a lasting contribution to the nation’s architectural style.

Although the local culture was strong, the authority of Córdoba began to wear thin and small kingdoms called taifas gained local control. Decentralisation led to internal dissent, partly caused by the rise of the Sufi religious sect. Sufism was considered a subversive and heretical kind of mysticism, but it gained popularity in reaction to the rationalism of conventional Islamic beliefs. These internal divisions allowed Christian forces to push the frontier lines down from the north, but they also permitted radical Muslim military groups such as the Almoravids and the Almohads to rise rapidly to power.

The Almoravids, who had built an empire in Africa, spread northwards. After helping the Islamic rulers in the peninsula to force the Christians back, they unified the taifas under their own rule. By 1095 they had succeeded in installing an austere military system and harsh government. They were soon followed by the still more fanatical Almohads and the simmering Reconquista took on the aspect of a Holy War for both Christians and Muslims.

Military Orders

The crusades produced an unusual kind of soldier – that is, those belonging to the military orders created by St Bernard of Clairvaux in 1128. The Knights Templar was the first such order, based in Jerusalem, which had been captured in the First Crusade (1096–99). They were followed by the Knights of St John (the Hospitallers), established in Rhodes, and by the Teutonic Order and the Spanish Knights of Calatrava. Originally, their role was to fight for the true faith while obeying monastic rules of poverty, chastity and obedience. Soon, however, the spoils of war became more important than the spread of Christianity.

The split with Spain

Portugal’s separateness from Spain, with which it shares a border, has been attributed to various causes, from the original borders between indigenous tribes to the land held by the Suevi against the Visigothic advances. However, it was during the Christian reconquest of Iberia that Portugal first truly asserted its independent stance and its leaders gained their sense of national destiny.

Late in the 9th century, the area between the Lima and Douro rivers, a territory which became known as Portucale, was divided under unstable feudal states, and came under the control of the Kingdom of León.

Fernando I of León was the great consolidating force in northern Spain during the 11th century. As part of his policy of centralising authority, he tried to diminish Portugal’s power by dismantling it and dividing it into different provinces under separate governors. When Fernando’s successor Alfonso VI took over the kingdoms of León, Castile, Galicia and Portugal, he declared himself “emperor”, putting himself above kings. It may have been the lure of the title “king”, which the emperor had unwittingly made available, that inspired Afonso Henriques, in the 12th century, to battle, deal and connive for the autonomy of his particular terra, Portugal.

The most famous Sufi poet was Omar Khayyám (1048–1120), whose Rubaiyat, in which women and wine are given mystical significance, was translated into English by the Victorian poet Edward Fitzgerald.

Feuding cousins

Afonso Henriques was the son of Henri of Burgundy and his wife Teresa. Henri was among a number of French knights who had arrived in the late 11th century to fight the infidels. They were mostly second and third sons, who, under the prevailing system of male primogeniture – which meant that the eldest son inherited property and titles – were left with no real inheritance. If they wanted land and riches, they usually had to travel abroad to win them.

Henri’s cousin Raymond, who, like Henri, was a fourth son, also came south. After proving his heroism in battle, Raymond married Alfonso VI’s eldest daughter Urraca, and was granted the territories of Galicia and Coimbra. When Henri married Teresa, who was Alfonso’s favourite (although illegitimate) daughter, he was given the territory of Portugal. With the death of Raymond and Alfonso VI, Urraca inherited that crown, but her second marriage, to Alfonso I of Aragon, also set in motion a complex round of civil wars.

During this period, Henri of Burgundy made significant strides towards gaining autonomy for the state of Portugal. The most important of these was the support he offered to the archbishops of Braga in a dispute with those of Toledo, the principal see of Spain.

In 1126 Urraca died and her son, Alfonso Raimundez, became Emperor Alfonso VII. When Henri died, his widow, Teresa, ruled Portugal as regent for her son, Afonso Henriques. Without wasting much time in mourning, she took a Galician count, Fernão Peres, as a lover, displeasing some of the nobility as well as her son. Continuing her husband’s policies, Teresa schemed successfully to maintain Portugal’s independence, but in 1127 she submitted to Alfonso VII’s dominion after her army’s defeat. A year later 18-year-old Afonso Henriques led a rebellion against his mother, ending her rule at the battle of São Mamede, near their castle in Guimarães.

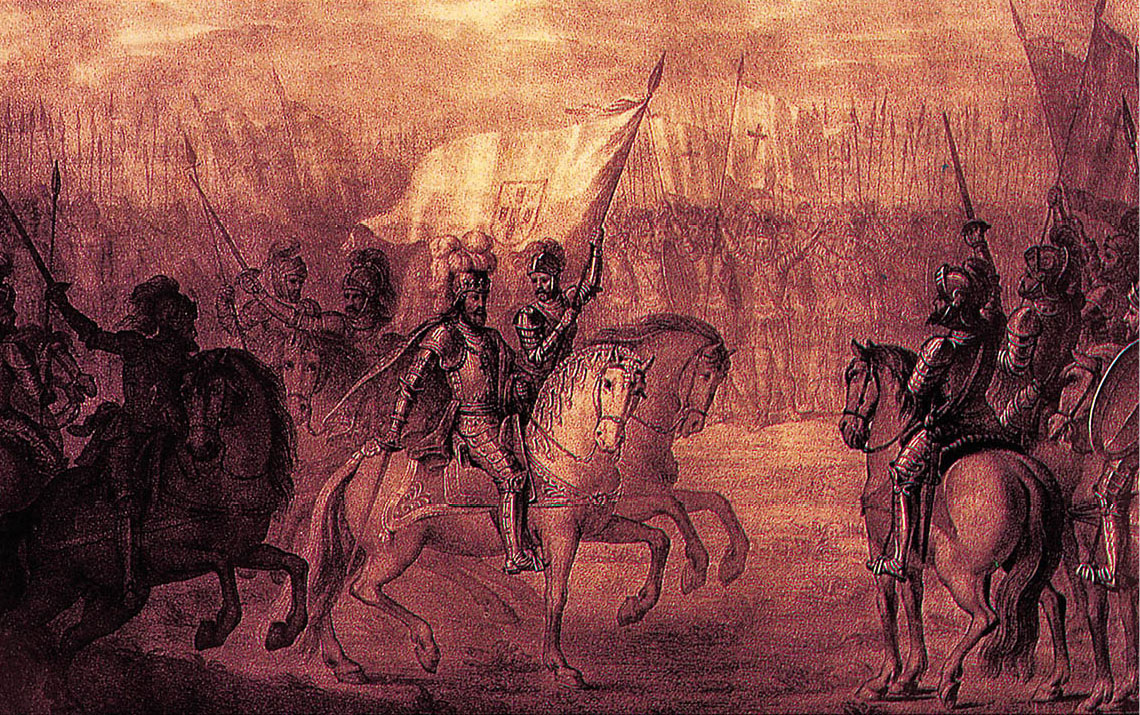

An 18th-century engraving showing Afonso rallying his troops at the conquest of Lisbon in 1147.

Museu da Cidade, Lisbon

A king is crowned

Over the next decade, Afonso Henriques vied with his emperor cousin for ultimate control of Portugal. After a brilliant military victory over the Moors in the Battle of Ourique in 1139, he began to refer to himself as king. In 1143, the Treaty of Zamora was signed between the two cousins, wherein Alfonso VII gave Afonso Henriques the title of King of Portugal in exchange for feudal ties of military aid and loyalty.

Afonso Henriques sought to fix the title more firmly by seeking recognition from Rome. Pope Lucius II refused, keeping to a policy of supporting Iberian union in the hope of stemming the tide of Islam. It was only in 1179 that Pope Alexander III, in exchange for a yearly tribute and various other privileges, finally granted recognition of the Portuguese kingdom. By that late date, papal acceptance served only to formalise an entity that was not only well established but growing. Afonso Henriques had enlisted the aid of crusaders and beaten back the Moors, adding his conquests to the emerging nation. Santarém and Lisbon were both taken in 1147; the first by surprise attack, the second in a siege that was supported by French, English, Flemish and German crusaders who were passing through Portugal on their way to the Holy Land, to fight what we now know as the Second Crusade.

The inestimable assistance of these 164 shiploads of men was extremely fortuitous; it very nearly fell through when Afonso Henriques pronounced that he expected them to fight only for Christianity and not for earthly rewards. This was not the way the crusaders believed holy wars should be fought. The English and Germans walked out, and the king quickly compromised, offering loot and land in exchange for military service.

Azulejo in the Sala dos Reis (King’s Hall), Alcobaça Abbey.

Getty Images

The western crusade

The Bishop of Braga also offered aid in recruiting foreign crusaders, providing theological assurance that their enemies in the south would be heathens, and therefore no different from those they would be fighting in the Holy Land – convincing crusaders that one batch of infidels was as good as another was crucial to the Reconquista. However, Afonso Henriques’s confessor questioned the diversion of troops from the crusade, and the story is told that on the way to Santarém – with crusaders in tow – the king, believing his confessor to be right, was besieged by guilt. He was also, understandably, anxious because of the Moorish stronghold’s reputation for impregnability.

To soothe his torment, he vowed that he would build an abbey at Alcobaça (some 90km/55 miles southwest of Coimbra) in honour of the Virgin if the attack was successful. The battle was won, and Afonso Henriques laid the foundation stone of the promised building the following year. The imposing abbey still stands (for more information, click here).

In 1170, Afonso Henriques fought his last battle, at Badajoz. The powerful Almohads had enlisted the aid of Fernando II of León, who felt that the Portuguese were recapturing not only the Moorish-held land, but territory that was by right a part of León.

The most renowned of Afonso Henriques’ military cohorts was Geraldo Geraldes, a local adventurer dubbed O Sem Pavor (The Fearless) for his brilliant raids into Muslim territory. This popular hero had won a string of epic victories, but at Badajoz the combination of Moorish and Leonese forces was too much for both Geraldes and his king. The ageing Afonso Henriques broke his leg and was captured. His release came only after he had surrendered hard-won castles and territories to enemy parties. His retreat allowed the Moors to entrench their forces along the battle zone.

The founding king of Portugal’s days of victory were over, with the Reconquista still a century away. Yet, with Henriques’ monarchy, a country was born. Whether it was through an act of political will or not, the independence and individuality of the Portuguese nation was forever determined.

One result of the crusades – which began in 1096 and lasted for more than 150 years – was the founding of powerful military-religious organisations such as the Knights Templar and the Hospitallers (for more information, click here).

Azulejos depicting the vision of Afonso Henriques in which Jesus assured him victory in the Battle of Ourique (1139).

Getty Images