Saints, Miracles and Shrines

Religion in Portugal touches all aspects of life. Every town and village has its own saint, which is a cause for celebration at least once a year.

In the middle of the 6th century a young monk named Martin arrived in Mondoñedo, in northwest Spain, where he founded the abbey of Dume. His mission then took him to Braga, the former Roman city that had become the political and religious stronghold of the Suevi, a barbarian tribe that had adopted Arianism, a heretical form of Christianity. Martin, who had been inspired at the shrine of St Martin at Tours, was determined to convert their leaders to true Christianity.

In 559, he converted the Suevi king, Theodomirus. Within a decade, Martin was appointed archbishop of Braga. He found a further challenge, however, among the general population. Catholics since their conversion under the Roman Empire, they had incorporated many local beliefs and customs into their religion. To Martin, this was unacceptable, and in a written sermon entitled De Correctione Rusticorum (On the Correction of Peasants), he called for an end to the use of charms, auguries and divination, of the invocation of the devil, and of the cults of the dead, of fountains and stars.

Watching the Easter procession.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

St Martin did not succeed, nor have 14 centuries of similarly inclined zealots and reformers. Yet, though frowned upon by the orthodox Church, spontaneous, independent Catholicism should not be seen as a form of superstition or magic; rather, it is evidence of a vigorous religious tradition.

Many unorthodox elements linger to this day as an obstinate strain within Catholic traditions – naturally, there is much wrestling over the issues between the Church hierarchy and the parishes.

In the past, when a newborn child proved healthy, it was said that it was conceived when the moon was waxing. The states of the moon were believed to be very influential in the way all living things grow: vegetables, animals and human beings. Similarly, certain fountains were reputed to have particular healing powers. And under many of these, Moorish princesses were said to be hiding, watching over treasures.

Street party during the Festas dos Santos Populares.

Alamy

Around midnight

One of the more dramatic folk practices was the midnight baptism. This developed during the 17th century, and occurred when a pregnant woman was prone to miscarriages or when her previous child was stillborn. The “baptism” used to take place at midnight in the middle of a bridge that divides two municipalities – a powerful spot that is neither one place nor another, at the moment that is neither one day nor the next. Certain bridges, such as the Ponte da Barca in the Minho, were famous for this.

When everything was ready, the child’s father and a friend, armed with sticks, used to stand guard at the ends of the bridge. They are there to ward off cats and dogs – potentially witches or the devil in disguise. The first person who passes after the church bells strike midnight was charged with performing the rite. He or she would pour river water over the expectant mother’s belly and baptise the child “in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost” but the final “Amen” would not be uttered; this would wait until the child was born and properly baptised by a priest in church.

The Easter processional features children of all ages.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Such practices may now be consigned to history, but religious passion still governs behaviour in Portugal, and the church is the central meeting place of the whole parish. At Easter, the cross that represents the resurrection of Christ is taken from the church and carried to all the households. It is kissed as it enters each house, and when it is returned to the church, it is a symbol of the new life shared by the whole community.

Similarly, on All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day (1 and 2 November), the celebrations at the parish cemetery are attended by everyone. Lamps are lit, tombs are cleaned and decorated with flowers. The whole parish celebrates this strongly felt sense of continuity with the past, praying together for their dead.

Perhaps the strongest evidence that the feeling of community extends beyond this life is the common belief in the “procession of the dead”. Certain people claim that they have the power to hear or see a procession of the ghosts of those parishioners who have recently died. This procession is seen leaving the cemetery, with a coffin in its centre. When it returns, the ghost of the parishioner who will be the next to die will be in the coffin. Thus, it is said, these seers can predict how many people are going to die imminently – but they cannot reveal the names to anybody if they themselves want to remain alive.

Easter procession in Obidos.

Alamy

Patron saints

The use of religion to establish a communal identity is most clearly shown by the celebrations for the local patron saint. An organising committee busies itself all year collecting money, planning decorations, arranging events. The importance of these celebrations is immense. They represent and solidify local pride. The festa is a joyful occasion heralded by firecrackers and by music blaring from loudspeakers placed on the church tower. The pivotal event is the procession after Mass, when the image of the patron saint is carried with great pomp on a brightly decorated stand in a traditional, roughly circular path.

After that, the secular celebrations begin. These usually involve dancing to traditional brass bands, folk-dance groups and, nowadays, rock and pop bands as well. A great deal of wine is consumed and the festivities are a popular social focus for young people. Not surprisingly, it is this aspect of the celebration that some priests oppose.

Popular attitudes to saints differ from church doctrine not so much in content as in emphasis. The people place great importance on material benefits and personal, reciprocal relationships with saints. They pray to specific saints for specific problems – St Lawrence if they have a toothache, St Brás if suffering from a sore throat, St Christopher when going on a journey. Our Lady of the Conception, naturally, helps with problems of infertility, and the Holy Family is asked to intervene in family problems, and so on. People will also address personal prayers to particular saints. If the believer’s prayer is answered, this proves that the particular image is a singularly sacred one, a favoured line of communication. In this way shrines develop, whether individual, family, or even national, with images famous for their miraculous powers.

The notion of the miracle in popular religion is more loosely interpreted than in the Church. Essentially, a miracle is considered to have taken place every time a specific prayer is answered.

Wax offerings

When a prayer to St Anthony asks for a specific favour – that a loved one, or even a pig or sheep, recover from a bout of ill health, or an offer of marriage be accepted – a promise is made to give the saint something in return. A wax heart might be given for a successful engagement, or a wax pig if the animal has fully recovered. But if the promise is not fulfilled, punishment may follow.

If you visit churches in northern Portugal, you will often see these ex voto offerings hanging on the walls alongside other gifts such as bridal dresses, photographs, written testimonies or braids of women’s hair. Shrines of great importance such as Bom Jesus and Sameiro, near Braga, have large displays. At Fátima (see box page page 154), the best-known shrine in the country, wax gifts accumulate so quickly that special furnaces have been installed to burn them.

There is also another kind of gift: a personal sacrifice. The church has been strongly critical of this, but until the late 1960s, it was firmly encouraged. If you visit the shrine of São Bento da Porta Aberta (St Benedict of the Open Door), in the beautiful mountain landscape of Gerês near the dam of Caniçada on 13 August, you will find men and women laboriously circumambulating the church on their knees.

This scene is even more striking because these people are surrounded by others celebrating the day with singing, dancing, eating and drinking. But those on their knees are celebrating, too – because the saint has answered their prayers – you will see the same scene at the Fátima shrine at any time of year.

Another kind of payment to patron saints has all but disappeared, due to strong Church opposition. In the parish of Senhora da Aparecida in Lousada, for example, before the main procession leaves the church there is another one in which 20 or more open coffins – containing living people, their faces covered with white handkerchiefs – are carried through the streets. Those who ride in the coffins are offering a false burial to the saint who saved them from having to participate in a real one. The occasion, therefore, is a joyful one, although it sounds macabre. There is plenty of light-hearted banter, and the “dead” participants mingle with the other parishioners afterwards, drinking and dancing.

Surviving cults

The cult of the dead, another morbid religious tradition and one of the targets of St Martin during the 6th century, remains an object of popular fascination in the north. Very occasionally, a body is buried but does not undergo the normal process of decay. Such people are often considered to be saints and there are a number of grim shrines where the corpses are exposed. The Church nearly always opposes these cults at first, but eventually tolerates them as they grow in popularity: three such shrines are the Infanta Santa Mafalda in Arouca, the São Torcato near Guimarães, and the Santinha de Arcozelo near Porto. Even in an unlikely spot like the small urban cemetery of the elegant Foz neighbourhood in Porto, a shrine to one of these “saints” can be found.

Along rural roads one will frequently find pretty little shrines, but these are intended to protect travellers, and are not connected with the cult of the dead. They contain images of Christ or the Virgin or a popular saint. At the base, little moulded flames surround figures that represent the souls of sinners suspended in Purgatory.

Shrine outside Ferraguda church in the Algarve.

Alamy

Compromise and coexistence

Portuguese history is full of examples of the continuing conflict between the spontaneous and all-embracing religiosity of the less educated classes, and the more restrictive attitudes of the theologically minded – and the ways in which the two have learned to coexist. From the early days of the Western Crusade in the 12th century, and the power of military-religious orders like the Knights Templar and the Hospitallers, to the dark days of the Inquisition, religious and secular authorities have vied with each other for power, and used each other to the best advantage. In more recent years imperialism, like the early exploration and discoveries, was seen as a form of religious crusade: each victory along the way was considered a miracle. And Salazar’s regime actively encouraged the cult of Our Lady of Fátima, even managing to present its policy of neutrality during World War II as being based on the soothsayings of the Virgin.

Our Lady of Fátima

Fátima, near the town of Leiria, is one of the largest shrines in Western Europe (for more information, click here). On 13 May 1917, the Virgin is supposed to have appeared to three children. The event is said to have been repeated on the 13th of the subsequent five months, and each time the Virgin spoke about peace in the world. Fátima became a rallying point for the revival of Catholicism in the 1930s and 1940s. Today, from May to October the roads around Leiria are lined with pilgrims, many of whom have come great distances on foot to “pay” the Virgin for her favours.

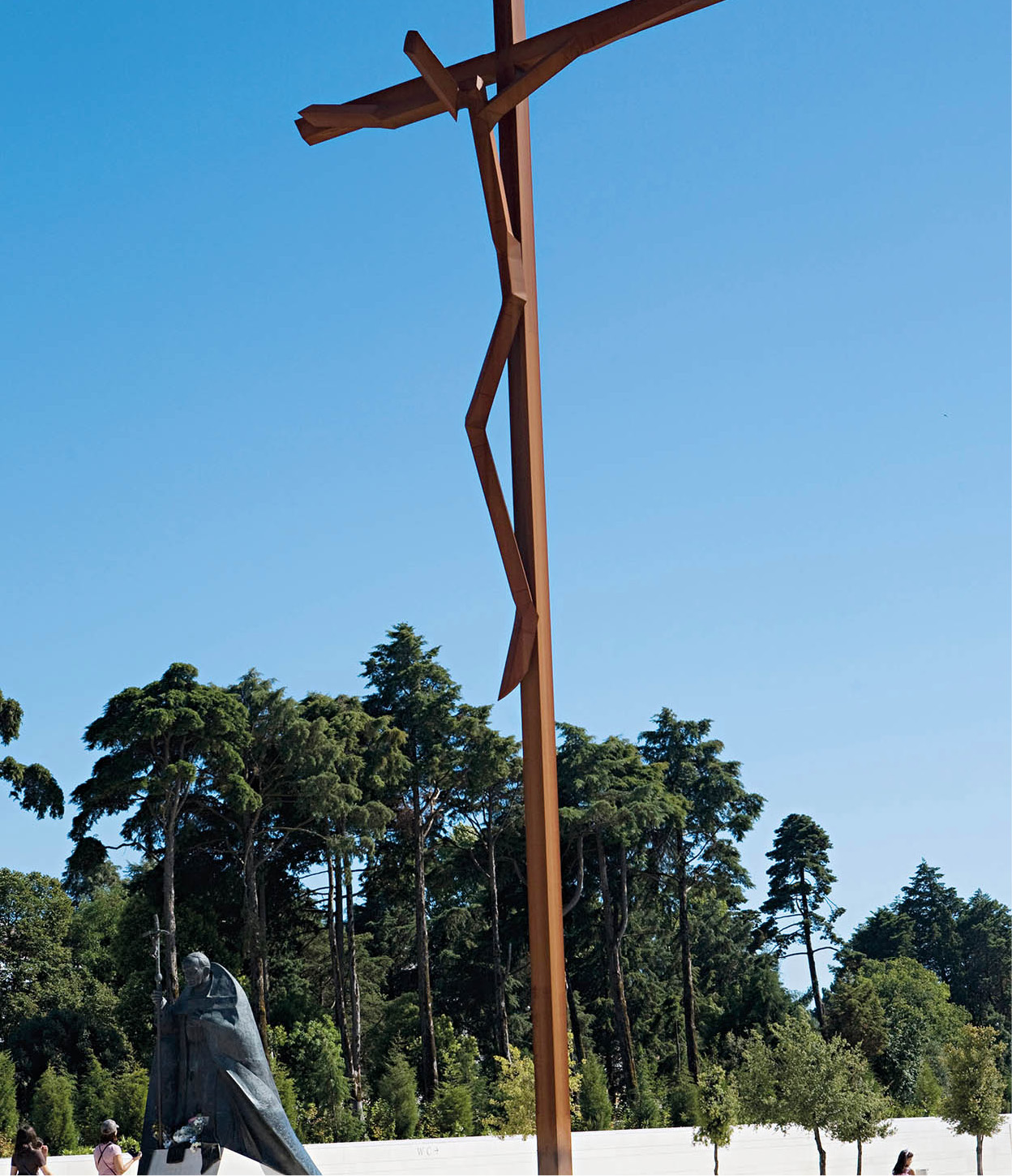

The High Cross at Fátima, designed by Robert Schad.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications