The Douro Valley

Renowned worldwide for the wine it produces, the Douro valley is graced by its centuries-old vineyards growing on steeply terraced hillsides.

Main Attractions

The romantic history of port wine has endowed the Douro region with unrivalled respect. Douro means “of gold” and the river, gleaming at sunset, does resemble a twisting golden chain as it winds through the narrow valley between the steep hills and terraced vineyards. The countryside is exceptionally beautiful, particularly in spring and autumn, and is enhanced by the neat rows of vines which grace the hillsides.

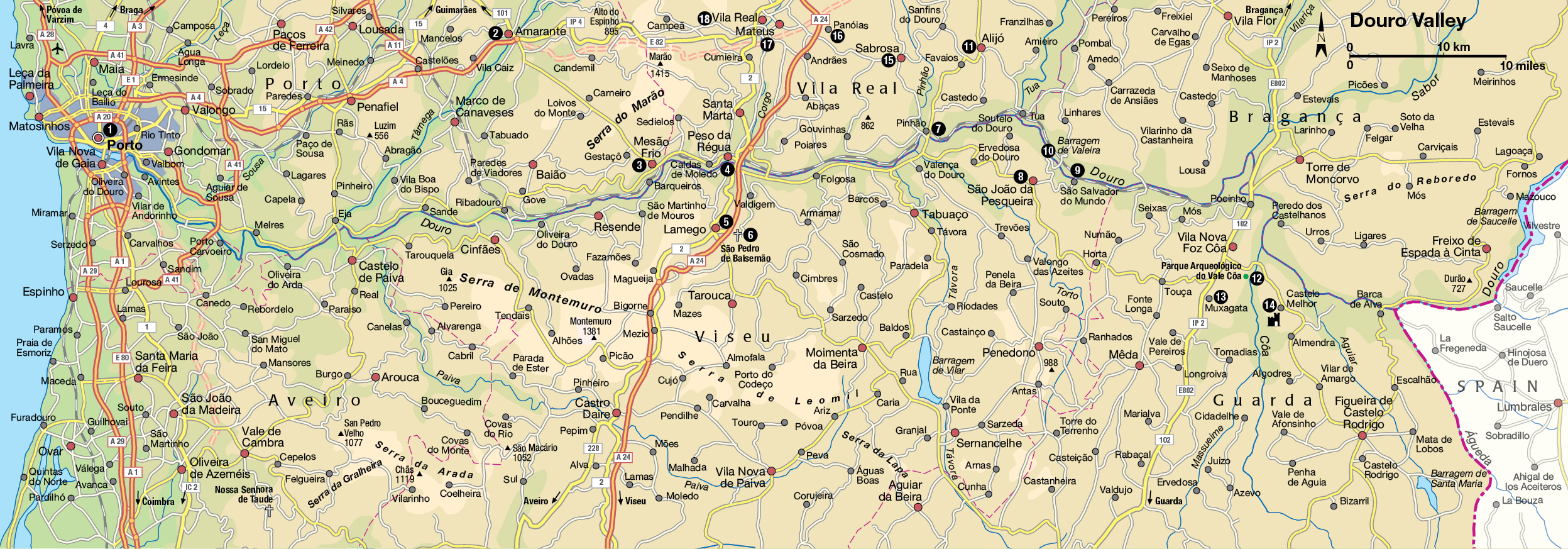

Although the Douro stretches from Spain to the Atlantic at Porto, only the inland part of the valley, the Alto Douro, is recognised for growing the grapes used for port wine. The demarcated region starts some 100km (60 miles) upstream from Porto at Barqueiros, just before Régua, and follows the river all the way to Spain. Some of the tributaries of the Douro – the Corgo, Torto, Pinhão and Tua – are included in the area. It was Portugal’s authoritarian Marquês de Pombal who staked out the Douro in 1756, making it the first officially designated wine-producing region in the world. Subsequent legislation designated the Upper Douro as the port-wine region.

Characteristically, the schistose soils are stony and impoverished and the climate extreme. Summers are very hot and dry, and made hotter by the direct rays of the sun reflected on the crystalline rock; winters are cold and wet. The large lumps of surface schist act as storage heaters, absorbing the sun’s heat in the day and releasing it throughout the night. The slopes nearest to the river grow the finest grapes and this land is highly prized.

Amarante’s historic bridge.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Amarante on the hillside.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Choosing a base

Peso da Régua (for more information, click here) is the capital of the Douro valley, with an office of the Port Wine Institute; it is also the headquarters of the port-growers’ association, which grades and certifies the wine travelling to Porto. The smaller town of Pinhão 25km (15 miles) further upstream is regarded as the centre of the wine industry, and this is where all the famous names have their farms. It is a handy place to stay although it is hardly bristling with hotels. Taylors have restored and extended a quinta on the banks of the Douro, now the Vintage House Hotel, providing quality accommodation. The area has a number of restored houses and farms that are part of the manor house system (for more information, click here), some of them in very fine locations.

Casa de Casal de Loivos, above Pinhão, has a fine overview of the Douro or, if you prefer to bury yourself in the country, Casa da Lavada, a restored 14th-century fortified manor house, provides modern comforts. It is high in the mountains of the Serra do Marão in a village where visitors are still a curiosity. Traditional hotels are found in the surrounding towns of Amarante, Vila Real or Lamego. Porto 1 [map] is a good base for organised trips into the surrounding area. Coach trips are well advertised but it is easy enough to catch a train from São Bento station on the Douro line. The end of the line is Pocinho, not too far from the Spanish border. There are branch lines to Amarante, Vila Real and Mirandela. The river is now navigable for much of its length and boat trips up the river are a regular feature and a pleasant way to see the countryside. One option is to go by boat as far as Pinhão and return by train.

Fact

Boat trips on the river are privately run and therefore not promoted through tourist offices. Trips last from a few hours to a few days, and most hotels and quintas will tell you what’s on offer.

Upriver from Porto

There is little to detain the motorist between Porto and Amarante so the fast A4 is the best way to travel. It speeds up what would otherwise be a very slow journey through vinho verde-growing countryside. The main area for vinho verde lies to the north in Costa Verde and Minho.

Amarante 2 [map], on the banks of the Rio Tâmega, is delightful, at least in the old part of town. Geese paddle contentedly among punts and trailing willow trees on the river, while afternoon tea-takers look on from overhanging wooden balconies. Dominant in the town is the three-arched Ponte de São Gonçalo, built in 1790. It became a battleground in the Peninsular War in 1809 when General Silveira, supported by Marshal Beresford’s troops, successfully fought off the French.

The bridge leads to the Convento de São Gonçalo (Mon–Sat 8am–7pm, Sun 8am–8.15pm; free), named after the local patron saint, and protector of marriages.

Amarante’s association with fertility rites reaches back into the mists of time, and some claim the town’s name is derived from amar, meaning “to love”. These ancient beliefs have empowered São Gonçalo, beatified in 1561, to assist believers in everything pertaining to love and marriage. He is honoured every June by a festival which, as you may imagine, is a particularly raucous occasion, with the local men out in the streets offering distinctly phallic-shaped cakes to any women prepared to accept them.

The convent, however, is much more sombre. It was begun in 1540 but not completed until 1620. Inside is the tomb of São Gonçalo, who died about 1260, and some lush gilded carved woodwork. Anyone aspiring to love and marriage need only touch the effigy of the saint to be blessed within the year. Sadly, the limestone effigy is now quite worn in places.

Above the rear cloister is the Museu Amadeo de Souza-Cardosa (Tue–Sun June–Sept 10am–12.30pm, 2–6pm, Oct–May 9.30am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm), which has some superb contemporary and Modernist Portuguese paintings – Souza-Cardosa was a Cubist artist who came from Amarante.

Nearby is the Quinta da Aveleda (tel: 255 718 200; www.aveleda.pt; daily visits at 10.30am, noon, 3pm and 4.45pm), seat of one of Portugal’s main wine empires and a leading exporter of the country’s famous vinho verde. A visit to the quinta includes a tour of the beautiful gardens, as well as the bottling plant. At the wine lodge you can taste two different types of vinho verde, accompanied by local cheese, and buy a bottle or a case from the old distillery, which has now been converted to a store. If you want to have lunch here or would like a more personalised tour, including a visit to the production facility, you must book in advance.

Beyond Amarante the road turns abruptly south to twist and climb through the Serra do Marão. Vinho verde vines climb the trees here and huge granite tors stand in the summit region. Beyond is a descent to the small village of Mesão Frio 3 [map], and a sweeping view of the Upper Douro winding peacefully through the gorges of the port-wine country.

The road follows the river’s north bank, passing through the small spa town of Caldas de Moledo before reaching Régua 4 [map] (its full name is Peso da Régua), a busy river port and the headquarters of the Casa do Douro, an organisation that has a great deal of power in the regulation of port-wine production. In this area lie some of the oldest British and Portuguese estates, and information about them can be had from both the Casa do Douro and the tourist office near the market. Here the road crosses the Douro and runs along the picturesque southern bank.

Nossa Senhora dos Remédios church.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Tip

The best time to visit the Douro valley is during the vindima, in September, when the grapes are being collected. Some vineyards give tourists the chance to participate in the grape harvest, joining in with the picking and then trampling the fruit barefoot in the pressing basins to release the juice.

South of the river

Before following along the south bank towards Pinhão, there is a worthwhile diversion to Lamego 5 [map], which is a city of historical importance. The Lusitanians arose in revolt against the occupying Romans, refusing to pay the heavy taxation, so the Romans burned the town to the ground. Fernando of León and Castile took the city, aided by the legendary El Cid, and allowed the Muslim wali to continue to govern Lamego, as long as he converted and paid tribute to the king. But the city’s most significant moment in Portugal’s history was in 1143, when the cortes met for the very first time. At this meeting, the nobles declared Afonso Henriques to be Afonso I, the first king of Portugal.

Lamego’s 12th-century castle, on one of the city’s two hills, preserves a fine 13th-century keep, with windows that were added later and a very old and unusual vaulted cistern. The cistern is possibly Moorish, with monograms of master masons.

The pilgrims’ stairway at Nossa Senhora dos Remédios.

Mark Read/Apa Publications

Pilgrimage Church

Atop Lamego’s other hill is the visually striking church of Nossa Senhora dos Remédios, crowning a vast stairway reminiscent of Braga’s Bom Jesus. The first chapel was founded by the Bishop of Lamego in 1361, and dedicated to St Stephen. In 1564, it was pulled down, and a new one built. From that time, there has been a steady stream of the faithful seeking cures. The first week in September is the time of the major pilgrimage, and there is a jolly accompanying festival which seems to have little to do with healing or piety. The present sanctuary was started in 1750, and was consecrated 11 years later – but the magnificent Baroque-style staircase leading up to it, begun in the 19th century, was completed only in the 1960s. Fountains, statues and pavilions decorate each level.

The Sé (Cathedral; daily 8am–1pm, 3–7pm), a Gothic structure, was built by Afonso Henriques in 1129. Only the Romanesque tower is left from the original building. The city museum, housed in the 18th-century Bishop’s Palace, has a collection that includes Flemish tapestries dating from the 16th century and works by Grão Vasco.

Historical re-enactors dress up for a medieval festival in Lamego.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Just outside Lamego (start on the Tarouca road), in the valley of the Rio Balsemão, is the tiny São Pedro de Balsemão 6 [map], a Visigothic church believed to be the oldest in Portugal, with parts of the structure dating back as far as the 6th century.

Following the south bank of the Douro towards Pinhão is a rewarding drive; you can enjoy the flowing lines of vineyards patterning the hillsides and broken only by signs displaying such well-known names as Sandeman, Barros and Quinta Dona Matilde.

Pinhão 7 [map], on the north side of the river, seems an unlikely town to lie at the heart of the port-wine region. There is little to visit but it is worth a stop at the railway station to see the azulejo panels depicting scenes of the Rio Douro or to taste some wine in the barrel-shaped café by the river. The tourist office (Rua António Manuel Saraiva; tel: 254 731 932) has information about the wine estates in the region.

Vineyards in the Douro River.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

A scenic circular tour

A tasty sampler of typical Douro scenery and traditional villages can be enjoyed on a short circular tour from Pinhão, taking around half a day. It starts on the south side of the river, along the road climbing the hillside to São João da Pasqueira 8 [map]. This village has some fine 18th-century houses mixed with surprisingly modern properties. Follow left-turns signposted Barragem de Valeira to drive through dilapidated, overgrown vineyards ravaged by the Phylloxera scourge in the 19th century and never replanted. Watch out on the descent towards the barragem (reservoir) for the pointed hill, São Salvador do Mundo 9 [map], which is littered with churches and chapels.

Around where the Barragem de Valeira ) [map] now stands is where Baron Forrester, the 19th-century English pioneer, lost his life in 1861: in those days the river here tumbled over dangerous rapids. Born in Hull in 1809, Joseph James Forrester came out to Portugal as a young man to work for his uncle in Porto. He was fascinated by the wine industry and spent many years boating up and down the river making a detailed map. His widely acclaimed work won him his title in 1855, the first foreigner to earn such an honour. It was the river that eventually claimed his life at the age of 51. He was out boating with Antónia Adelaide Ferreira and others when they ran into trouble at the Cachão de Valeira rapids. The boat capsized and Baron Forrester drowned, dragged down, it is said, by the weight of his money belt. Antónia Adelaide Ferreira survived, helped by the buoyancy of her crinoline dress.

Cross the barragem to regain the north shore and zigzag up the hillside towards Linhares. Vineyards make the patterns and create the scenery for much of the way towards Tua and Alijó. Alijó ! [map] is one of the bigger towns in the area and is the location of a pousada named after Baron Forrester. The route back heads through Favaios to Pinhão.

Rock art

Winding eastwards from Pinhão through São João da Pasqueira and along the hill contours, past quaint churches and villages, you will come to Vila Nova de Foz Côa and the valley of the Rio Côa. Work in the 1990s to build a dam in this remote region uncovered a remarkable collection of rock paintings.

In 1996 the Portuguese Government declared the Côa valley protected as the Parque Arqueológico do Vale Côa @ [map] (www.ipa.min-cultura.pt/coa; tel: 279 768 260; Tue–Sun 9am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm; visits must be reserved in advance). In 1998, the park, which has the largest area of palaeolithic engravings in Europe, was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site.

At present, only three rock-art sites in the valley can be visited, not by individuals, but on a guided tour with a vehicle. These are at Penascosa, Ribeira de Piscos, Canada do Inferno and Fariseu (seasonal). The tours all last around 90 minutes. Tours to Canada do Inferno start from the Museu do Côa; tours to Ribeira de Piscos start from the visitor centre at Muxagata £ [map], while tours to Penascosa leave from the reception centre in Castelo Melhor $ [map].

The stunning Museu do Côa (Tue–Sun 10am–1.30pm, 2–5.30pm) stands in the middle of nowhere like an installation in the landscape. The museum houses cutting-edge displays on the rock paintings, as well as temporary exhibitions, and has a restaurant with wonderful views over the park.

Fact

Pressure to stop the flooding of the Côa Valley included a rap song recorded by high-school students from Vila Nova de Foz Côa, with the line “Petroglyphs can’t swim”. Although the dam project was abandoned in 1995, many carvings had already been submerged by the construction of the Pocinho dam in 1982.

A bridge over the Douro Valley.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

North to Vila Real

Going from Pinhão to the north leads to Sabrosa % [map], the birthplace of Fernão de Magalhães, known in English as Ferdinand Magellan, the man who led the first circumnavigation of the world between 1519 and 1522 under the Spanish flag. Just before Constantim, look out on the right for a diversion to the sanctuary of Panóias ^ [map] where there is a field with a series of enormous carved stones, believed to have been used as altars for human sacrifice. Inscriptions in Latin invoke the ancient god Serapis, known to both Greek and Egyptian mythology.

Mateus Palace.

iStockphoto.com

Beyond Constantim but before Vila Real is the village and fantastical palace of Mateus & [map] (www.casademateus.com; May–Sept 9am–7.30pm, Nov–Apr 9am–6pm) with its celebrated gardens. It was built by Nicolau Nasoni in 1739–43 for António José Botelho Mourão. Today, an illustration of the palace graces the distinctive label of the popular rosé wine from this area, even though there is no formal connection. Mateus Rosé is still Portugal’s best selling wine export, with distribution in more than 150 countries. The exquisite building, with its striking Baroque facade, double stairway and huge coat of arms, frequently hosts musical events.

Vila Real

An ancient settlement in the Terra de Panóias, Vila Real * [map] was founded and renamed by King Dinis in 1289. Its name, “royal town”, is appropriate, as Vila Real once had more noble families than any city other than the capital. Walking through ancient streets, you will see many residences marked, often above the main entrance, with the original owners’ coats of arms. As likely as not, descendants of the family will still be living there.

The 19th-century writer Camilo Castelo Branco lived in Vila Real and wrote many of his most enduring works using the town as a backdrop.

Vila Real became a city proper only in 1925, but the importance of the region dates from 1768, when the vineyards were developed commercially: the area has good red and white wines, but it is the rosé that is best known – especially Mateus. Now a lively bustling industrial centre, Vila Real is one of the largest towns in the region.

The Sé (Cathedral) was originally the church of a Dominican convent. Although much of the present building dates from the 14th century, Romanesque columns still remain from an earlier structure. The oldest church is the ancient Capela de São Nicolau, on a promontory of high land behind the municipal hall, overlooking the valley of the Rio Corgo. Another church of note is São Pedro, whose Baroque touches were completed by Nicolau Nasoni (1691–1773), the Tuscan-born architect who designed the manor house in Mateus. Among fine houses dating from the 15th–18th centuries is the Casa de Diogo Cão, an Italian Renaissance-style building that was the birthplace of Cão, the navigator who discovered the mouth of the River Congo in 1482.

As far as local crafts are concerned, the Vila Real region is noted for the black pottery of Bisalhães and the woollen goods of Caldas do Alvão and Marão.

Selling baked goods at the market in Amarante.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications