A Nation is Born

With the final expulsion of the Moors, Portugal steadily established a kingdom under the House of Burgundy.

For a century after the death of Afonso Henriques in 1185, the first order of business was the slow riddance of the remaining, and still feisty, Moors. The Reconquista, now virtually sanctioned by the Church with various papal bulls and indulgences as a “western crusade”, was still very much under way.

The Knights Templar had arrived in Portugal when they stopped on their way to Palestine in 1128. They were soon followed by other military-religious orders – the Hospitallers and the Knights of Calatrava and Santiago – who all clung to the religious justification for their war-mongering and for their massive accumulation of land and loot.

King Dinis, depicted in a 17th-century screen.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon

However, the western crusade remained controversial. In Palestine the dividing line between Christians and infidels was clearly drawn, but southern Iberia had intermingled Muslim, Christian and Jewish people in economic, cultural and political spheres. In 1197, papal indulgences were even promised in a war against Alfonso IX of León, a Christian, though at that time an ally of the Muslims.

The war proceeded steadily, if slowly. The first kings of the Burgundian line after Afonso Henriques continued to press the borders southwards. Under Sancho II, the eastern Algarve and Alentejo were incorporated in the burgeoning nation. By 1249, during the reign of Afonso III, the western Algarve and Faro had fallen. By 1260 Afonso had moved the capital south from Coimbra to Lisbon. These boundaries – much like today’s – were finally recognised by Castile in the Treaty of Alcañices in 1297.

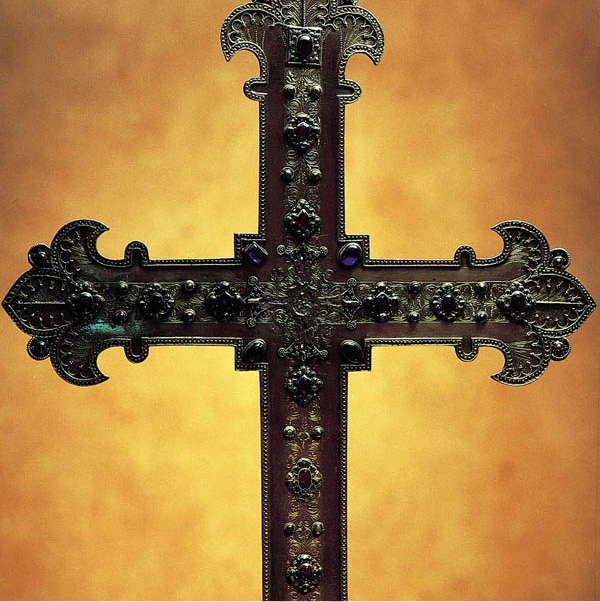

The 13th-century cross of Sancho I.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon

Social transformation

The Reconquista brought Portugal fundamental social transformation. The lands of the south, having been reclaimed, now had to be populated. In order to do this, the Burgundian kings needed to balance their centralised, essentially military power with popular and financial support. The need for such support forced successive kings to consult the cortes, local assemblies of nobles, clergy and, later, mercantile classes. At the cortes of Leiria (1254), Afonso III conceded the right of municipal representation in taxation and other economic issues. For the most part, the cortes were gathered whenever the king needed to raise money. When later monarchs used trade and their own military orders to reap independent profits, the cortes fell into disuse.

Another result of the Reconquista, with the expansion of properties and the need for labourers, was an increase in social mobility among the lower classes. Distinctions fell away among various levels of serfs as farm workers became a scarcer and more valuable commodity. Another effect was the early amalgamation of the divergent cultures of north and south. The south was a culture of tolerance, marked by refinement and urbanity, while the northern culture had a certain arrogance, the attitude of invaders. Differences between the two remain today.

Tomar’s Convento do Cristo.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The Church rode the Reconquista to riches. The various military-monastic orders were granted vast areas of land in return for military assistance. Furthermore, Church and clergy were free from taxation, and were granted the right to collect tithes from the population. Their power was such that it soon threatened the monarchy. Afonso II was the first ruler to defy the Church by attempting to curb its acquisition of property. His efforts generally failed, as did those of his successor, Sancho II, who was finally excommunicated and dethroned in 1245 for his insistence on royal prerogatives.

The poet king

It was the reign of Dinis, known both as “the farmer king” and “the poet king”, that truly cemented Portuguese independence and the power of the monarchy. After briefly joining Aragon in war against Castile, Dinis ushered in a long period of peace and progress. He encouraged learning and literature, establishing the first university in 1288, initially in Lisbon, then transferred to Coimbra. Portuguese, having distinguished itself from its Latin roots and from Castilian (which became Spanish), was established as the language of the troubadour culture, and the official language of law and state.

The troubadour culture – poetry and music spread by peripatetic minstrels – was greatly influential. Drawing on French tradition and Moorish influences, Portuguese troubadours created a native literature. These song-poems of love and satire were often written by nobles, among them, of course, Dinis himself. Other forms of literary expression lagged far behind.

Dinis’s rule also brought political progress. Landmark agreements were made to seal peace with Castile (the Treaty of Alcañices, 1297) and the clergy (the Concordat of 1289). The latter agreement was a major victory for royal jurisdiction in matters of property. Dinis also fortified the frontier, building some 50 castles.

In his role of “farmer king” Dinis reformed the agricultural system and initiated programmes that encouraged the export of olive oil, grain, wine and other foodstuffs.

Economic advances

By now a monetary economy was well established, internally as well as for international trade. Agricultural production was more and more geared towards markets, although self-sufficient farming did not disappear. Dinis encouraged the expansion of the economic system with large fairs, trading centres that encouraged internal trade – he chartered 48 such fairs, more than all the other Portuguese kings combined. This concentration of trade also, not coincidentally, allowed for more systematic taxation.

The only section of the economy to lag behind was industrial production. Dinis, and later kings, were counter-productive in resisting the idea of corporations. Craftsmen tended to work on their own, and thus confined themselves to local markets and limited quantities, although some goldsmithing, shipbuilding, and pottery was done in commercial quantities.

Perhaps the most significant of Dinis’s accomplishments was the disbanding of the Knights Templar in 1312. The order was under fire throughout Europe, and its demise was imminent. Dinis’s triumph was to retain its wealth within the country and prevent the Church from appropriating it. In 1317 he founded the Order of Our Lord Jesus Christ, which was granted all the former possessions of the Knights Templar, under royal control.

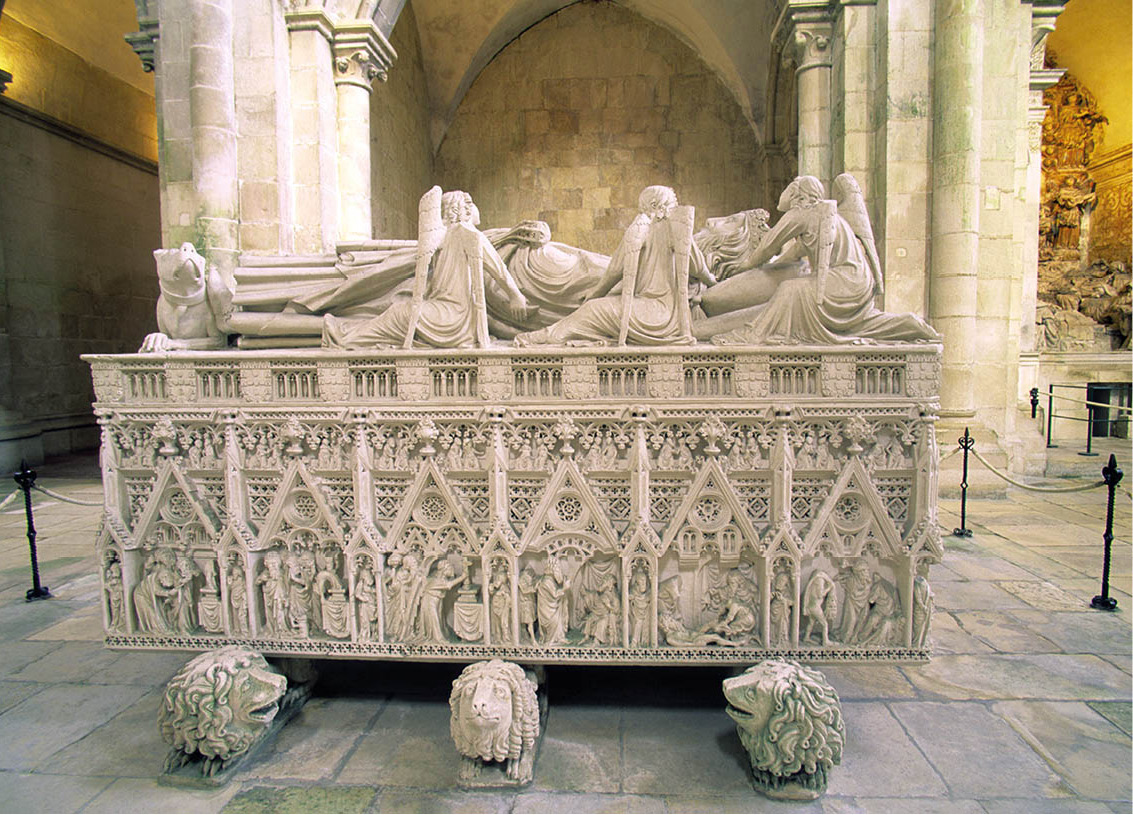

The tomb of Pedro I in the monastery at Alcobaça.

Alamy

Plagues and crises

Afonso IV succeeded Dinis. His administration was less secure and hostilities with Castile waxed and waned. More significantly, his reign was burdened with the Black Death. The first bout devastated the country, particularly the urban centres, in 1348–9. Throughout the next century the pestilence returned again and again, causing depopulation and despondency. Concurrently, various demographic and economic crises were undermining the nation. The attraction of urban centres left the interior underpopulated, causing inflation in food prices. Successive monarchs tried to regulate population movements but were ineffectual. Economic stagnation, whose dreary influence extended to literature, religion, and every element of daily life, dragged on until the coming of the maritime empire.

The reign of Pedro I was marked by peaceful coexistence with Castile. Social and political growth flourished as the country recovered from the convulsions of the Black Death. However, the increasing power of the nobles, the clergy and the emergent bourgeoisie, all represented in the cortes, would later break loose in active social discontent during the reign of his son, Fernando I. It was this social unrest, coupled with Portuguese commitment to total independence from Castile, that would finally bring down the House of Burgundy.

The Story of Pedro and Inês

Betrothed to Constanza, a Spanish princess, Pedro, son of Afonso IV, fell in love with her lady-in-waiting, Inês de Castro, a member of a powerful Castilian family. She was banished in 1340, but returned upon the death of the princess in 1345. The threat of a Castilian heir was intolerable to Afonso, so, under pressure from three of his noblemen, he agreed to her assassination, then immediately withdrew consent. In 1355, taking matters into their own hands, the nobles murdered Inês in the grounds of what is now Quinta da Lágrimas (House of Tears) in Coimbra (for more information, click here).

Pedro was inconsolable. Two years later, when he assumed the throne on his father’s death, he tracked down his lover’s assassins, caught two of them, and had their hearts torn out. He then ordered the exhumation of Inês, whose body was dressed in royal robes and placed next to him on the throne. Each member of the court was forced to pay homage by kissing her decomposed hand. She was finally entombed in Alcobaça Monastery along with Pedro, who insisted their tombs were placed foot to foot so that, on the Day of Judgement, the first thing they would see would be each other. Both tombs carry the same inscription Até o Fim do Mundo – “Until the End of the World”.

This dramatic and touching story of love and revenge has been an inspiration to generations of Portuguese writers and poets.

Fernando tried to unite Portugal and Castile, engaging the country in a series of unpopular and unsuccessful wars. France and England joined the turmoil, using the Iberian peninsula as a theatre for the Hundred Years’ War. In 1373, Fernando signed an Anglo-Portuguese alliance with John of Gaunt, who had married a Spanish princess (for more information, click here). The same year, Enrique II of Castile attacked Lisbon, burning and pillaging the city. To add to the confusion, the ‘‘Great Schism’’ divided the Catholic Church under opposing popes from 1378, and Fernando changed loyalties frequently. Wars ravaged the country, leaving the populace tired and angry.

The carved figures of Batalha Abbey.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Fernando further alienated his subjects with his unpopular marriage to Leonor Teles, who was perceived to represent the landed gentry. Riots broke out at the wedding and again in 1383 when Fernando died, leaving his widow (aided by her lover, the Galician count João Fernandez Andeiro) to rule as queen mother.

Andeiro was assassinated within weeks by João, illegitimate son of Pedro I. In the ensuing civil war, Leonor had the support of most of the nobles and clergy, while João relied upon that of the middle class. He depended upon the deepening resentment the people felt towards Castile – where Leonor had fled after Andeiro’s death – and rode this growing wave to victory. The final military conflict was the Battle of Aljubarrota (1385), a decisive victory for João’s troops, despite being outnumbered.

The Battle of Aljubarrota

Many stories surround the Battle of Aljubarrota. Nuno Alvares Pereira, captain of João’s army, was ravaged by thirst when leading his forces into battle, and swore no traveller would ever go thirsty there again. Since 1385 a pitcher of water has been placed daily in a niche of the Aljubarrota chapel of São Jorge. João, too, made a vow: to build a church in the Virgin’s honour if his outnumbered army was victorious. As the enemy fled, João hurled his lance into the air to pick the spot where the monastery of Batalha would be built. He must have had a very strong arm, because the battlefield is 16km (10 miles) from the monastery.

The subsequent rule of João I, founder of the House of Avis, one of the military-religious orders, represented a new political beginning. The disputes with Castile continued, but they were winding down. The unsteady Anglo-Portuguese alliance was cemented by the Treaty of Windsor in 1386, a document cited as recently as World War II, when Britain invoked it to gain fuelling stations in the Azores. João I brought stability, but the change of order was not a social revolution. New political representation was established by the mercantile class, but it soon became clear that only the names had changed. The landed aristocracy still held the real power, and the new dynasty was much like the old.

Castles in the Air

It is said that there are 101 castles in Portugal. In fact there are many more.

Most of Portugal’s many castles were either built or rebuilt between the 12th and 14th centuries. King Dinis (1279–1325) alone began the construction or expansion of more than 50 fortresses. Perhaps he should have been called “the king of the castle” along with his other titles: “the poet king” and “the farmer king”. His labours can be seen throughout Portugal, but he concentrated his efforts along the eastern boundary. He strengthened the towns of Guarda, Penedo, Penamacor, Castelo Mendo, Pinhel and others, attempting to secure the area from the threat posed by Castile. He was well rewarded: the Treaty of Alcañices, signed in 1297, initiated a period of peace and stability between the two countries.

Dinis provided the money for the castles, and even specified the exact measurements of walls and towers. They were of a particularly fine construction, with designs not found on other buildings. Some of the towers were slender and elegant; many balconies were elaborate, with detailed machicolations. Dinis often gave a specific character and grandeur to the structures, as in the 15 towers he had built at Numão, or the Torre do Galo (Cockerel Tower) at Freixo de Espada à Cinta, with its beautiful seven faces.

Preparing for war

Many castles were on the sites of earlier forts: Moorish, Visigothic, Roman, or even earlier. It is interesting to note the developments in warfare as they are reflected in physical features of Portugal’s castles. Long wooden verandahs, for example, were attached to the castles’ walls in early days. Later these verandahs were covered with animal hides to prevent, or at least inhibit, them being burned by flaming arrows, but these too were abandoned at the end of the 13th century.

By this time, the carved stone balconies were being used for defensive purposes, with machicolations which allowed the defending forces to repel attackers as they attempted to scale the castle walls. (Machicolation is the name given to a space between corbels, or in the floor of a balcony, from which boiling oil or other substances could be poured or dropped onto the enemy.)

The most significant change came with the advent of gunpowder and artillery. The heavy cannons required thicker walls, sloped to resist the more powerful projectiles. Thicker walls also meant that the ramparts, running along the tops of the walls, could be wider, and enabled the heavy artillery to be perched on top. Arrow slits, a common feature in castles, were rounded to accommodate the new artillery, then abandoned as impractical.

All Portugal’s castles – many still sound, some in semi-ruin – are dramatically sited. Among the best are Lamego, in the Douro Valley (for more information, click here); Almourol, perhaps the most romantic of all, set on its own tiny island in the Rio Tejo (Tagus) and the subject of many myths (for more information, click here); and, of course, Guimarães, the birthplace (c. 1110) of Portugal’s first king, Afonso Henriques. Guimarães is one of Portugal’s oldest castles, having been built in the 10th century, and restored many times since. Early in the 19th century the castle was used as a debtors’ prison. It underwent extensive renovation in the 1940s (for more information, click here).

Most castles are open to visitors; some have been converted to hotels, while others stand ignored in empty fields. Solid though their construction may have been, do be careful when visiting the semi-ruined ones; it wouldn’t do to end your visit under a piece of falling masonry.

Almourol Castle stands on Almourol island.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications