Lisbon

With cafés, culture and a castle, Lisbon is a vibrant city, mixing old-world charm, local colour and modern amenities. A good local transport system will help you discover the best of it.

Main Attractions

Lisbon (Lisboa) is a bewitching city. It is remarkably picturesque, draped across its seven hills and overlooking the wide blue expanse of the River Tagus (Tejo), with wonderful miradouros (viewpoints). It is not only a cultural feast, with more than 30 museums, but has a thriving nightlife, with the charismatic districts of Alfama and Bairro Alto coming alive after dark, with buzzing restaurants, fado houses, and, later, bars and clubs to keep you going until daylight if you are so inclined.

A flavour of what Lisbon has to offer can be sampled in a crowded one-day visit, but that is barely enough to scratch the surface of the city’s complexities. Three days allows time to absorb the atmosphere, and city lovers will probably find a week too short. Lisbon’s climate of hot summers and mild winters makes it an ideal place to visit for most of the year, although spring and autumn are good times to enjoy the city at its best.

Climbing the hills of Lisbon on the Elevador da Bica.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

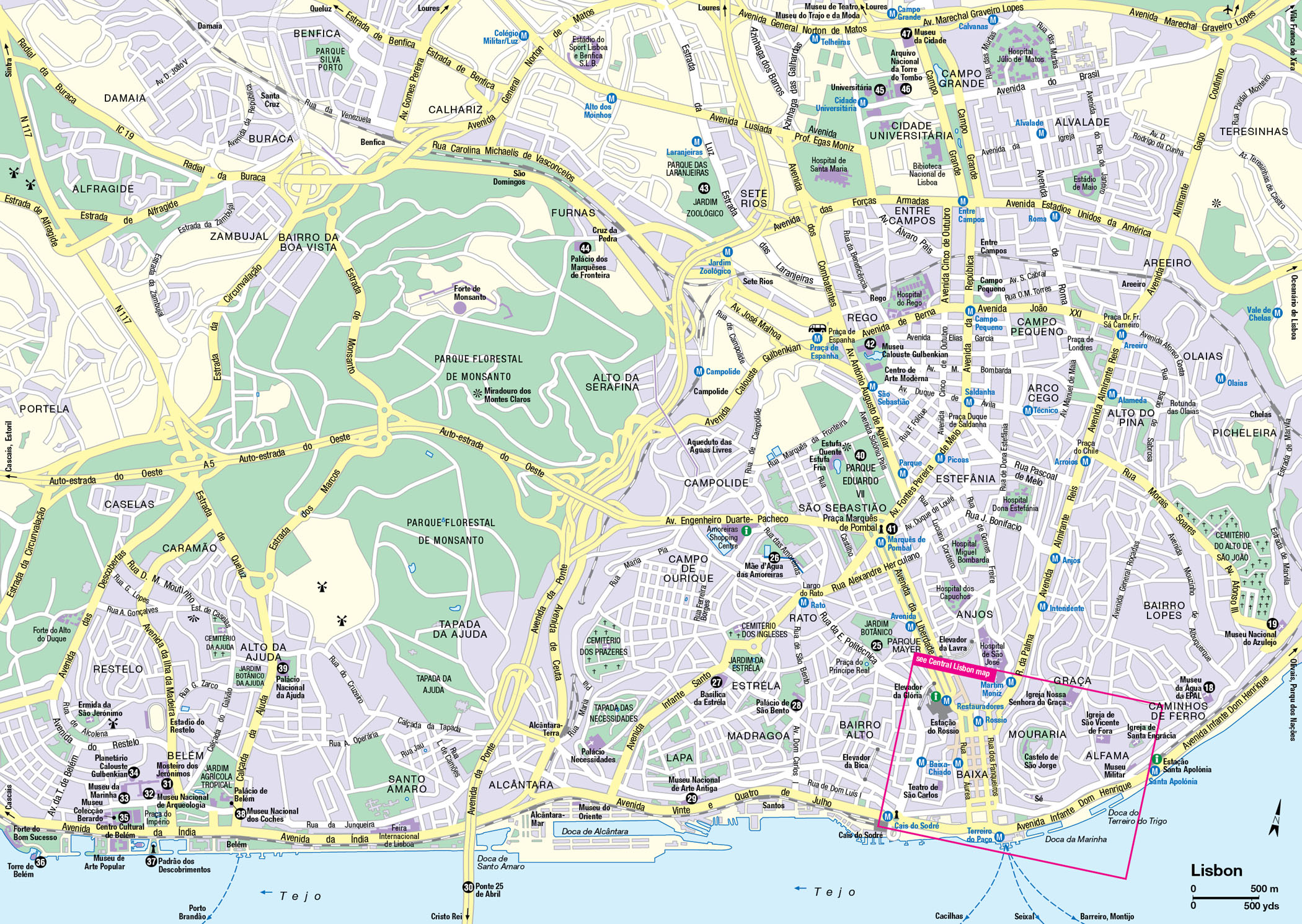

Many of the highlights of a visit to Lisbon are conveniently concentrated in three main areas, the heart of the city centred around the Baixa, and a significant cluster out along the riverside at Belém. Baixa is the hub of the city centre, watched over by Castelo São Jorge, below which cling the narrow streets and alleys of Alfama. To the west lies the hill of Bairro Alto, entered through the Chiado area. North, beyond Rossio, the main thoroughfare, Avenida da Liberdade, leads to Praça Marquês de Pombal and Parque Eduardo VII. East is the new neighbourhood of Parque das Nações with many pleasures of its own to offer.

Café life, commemorated.

Pictures Colour Library

Building Bridges

Most architecture in the city is post-1755, after the great earthquake, except for Alfama and Belém, which escaped virtually unscathed. There has been an upsurge in the restoration of old buildings and many dilapidated palaces and mansions have been tastefully renovated. Many have become elegant restaurants, fashionable boutiques, art galleries and even discotheques. Crumbling houses in the old quarters are also being restored, and in outlying neighbourhoods there are new hotels, vast and popular shopping malls, office complexes, cinemas and museums.

Visitors usually arrive by air and enter the city from the northeast, but a spectacular entrance is over the Ponte 25 de Abril from the south. Completed in 1966, the Ponte de Salazar was renamed in 1974 when democracy was restored to Portugal. A second bridge, Ponte Vasco da Gama, further up the river, was built for Expo ’98, which was sited on the river front nearby and has become the Parque das Nações.

View of Alfama from Largo das Portas do Sol.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

A touch of history

The mythical founding of the city on seven hills is attributed to Ulysses (Odysseus) and his encounter with the nymph Calypso. Left behind when he departed, the heartbroken nymph turned herself into a snake whose coils became the seven hills. In reality, there has been a settlement on the site at least since prehistoric times. Its advantageous geographical position caught the attention of Phoenician traders in search of safe anchorage who developed a port, Alis Ubbo (Serene Port), around 1200 BC. The Greeks, then the Carthaginians, subsequently laid claim to the site. In 205 BC Olisipo (as it was then known) was incorporated into the Roman province of Lusitania. Julius Caesar elevated the status of the city to a municipium in 60 BC and renamed it Felicitas Julia. What little remains of the Roman occupation today is from this period of relative prosperity and growth. As the Roman Empire crumbled, the city was left unprotected and vulnerable to attacks by a succession of barbaric Germanic tribes.

After the arrival of the Moors in the 8th century, the city enjoyed 400 years of stability and increasing prosperity, which came to an end in 1147, when the first king of the newly formed nation of Portugal, Dom Afonso Henriques, captured Lisbon. Around 1260 the Moors were finally vanquished and the capital moved here from Coimbra. A university was established in 1290 by King Dinis but transferred to Coimbra in 1308. A power struggle between the Church and the Crown over the next 200 years saw the university shunted between the two cities. In the end, Coimbra won that particular battle and Lisbon was left without a university until 1911.

The dawn of the “Age of Discoveries’’ at the end of the 15th century turned Lisbon into an important trading centre. Wealth from the opening up of the sea route to India by Vasco da Gama flowed into the country and the city entered a golden age that lasted for a century. A 60-year period of Spanish rule then saw a decline in fortunes, and for a while after the Spanish were ousted Lisbon suffered economically as maritime trade declined. The discovery of gold in Brazil ensured a return to former prosperity but most of this fortune was squandered by Dom João V on lavish building projects that were destroyed in the massive earthquake of 1755. The Marquês de Pombal was on hand to oversee the rebuilding of the city (for more information, click here).

Since then, Lisbon has witnessed the end of the monarchy, gunned down in its main square, and endured a long period of dictatorship under Salazar, which kept the city free of modern development, perhaps the only thing we can thank him for.

The vast Praça do Comércio.

Fotolia

Tip

Walking is the best way to see the city, but there is a good transport system of trams (eléctricos), buses, taxis, lifts (elevadors) and the metro. You can buy a 24-hour pass (€6), that covers buses, trams, funiculars and the metro, or invest in a Viva Viagem card (€0.50), which you charge up as you go; a single journey costs €1.25, compared with a normal price of €1.40.

Baixa and the city centre

Baixa (the lower quarter) covers the level area in between the hills of Alfama and Bairro Alto. It slopes gently to the banks of the Rio Tejo (Tagus) from Rossio and down through Pombal’s famous grid system of streets. City life centres around the vast expanse of the Praça do Comércio 1 [map] by the riverside. The earlier name of the square, Terreiro do Paço, is still used and dates back to the time before the earthquake when the 16th-century royal palace stood on the site. Behind the elegant Pombaline neoclassical arcades are municipal and judicial offices, and on the west side of the square is the city tourist office, the Lisboa Welcome Centre. You can also visit the new Lisboa Story Centre (www.lisboastorycentre.pt; daily 10am–8pm) here, a playful audiovisual exhibition that vividly immerses the visitor in the city’s history, and includes a dramatic cinematic recreation of the 1755 earthquake. Lisbon’s former Stock Exchange is to the east. In splendid isolation in the middle of the square stands a bronze statue of the ruler at the time of the earthquake, Dom José I, which gave rise to the English name of Black Horse Square. The riverside serves as a quay for ferry boats along the Tagus and across to the Outra Banda, the communities on the southern shore of the river. Completely overshadowing the delicacy of the arcaded buildings is the impressive triumphal Arco Rua Augusta. The arch is a late 19th-century addition to the square. Near here, the former colonial bank headquarters has been turned into the colossal eight-storey Museu do Design e da Moda 2 [map] (Rua Augusta 24; www.mude.pt; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm, Fri–Sat 10am–10pm), which opened in 2009 (see box).

Mude

MUDE (Museu do Design e da Moda; www.mude.pt) means “change” in Portuguese. This fantastic museum combines Lisbon’s former Design Museum – perhaps the world’s best collection of modern design – with works from the priceless collection of art mogul Francisco Capelo. The Design Museum collection is a roll call of modern design classics, featuring furniture and household objects by anyone who’s anyone in design: Charles Eames, Frank Gehry, Verner Panton, Philippe Starck, and many more. Ex-stockbroker Capelo’s contribution is a breathtaking collection of fashion, which includes 1,200 couture pieces, such as a Jean Dessé’s gown that Renée Zellweger wore to the 2001 Oscars, and Christian Dior’s landmark 1947 New Look.

A short walk along the road, from the northeast corner of the square, is the notable Manueline doorway of the church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição Velha 3 [map]. Further along, the unusual pyramidal stone facade of the 16th-century Casa dos Bicos 4 [map] (House of the Pointed Stones) seems almost modernistic. There is a clear distinction between the lower storeys, which survived the 1755 earthquake, and the top two storeys, which were faithfully reproduced from old engravings during the 1980s. A short distance further along the road lies the little-noticed 13th-century fountain Chafariz do Rei, once the major source of the city’s water supply.

Leaving the square from the northwest corner you pass the spot where, in 1908, Carlos I and his heir, Luís Felipe, were assassinated. Close by is the Praça do Municipio 5 [map], with an 18th-century pelourinho (pillory) and the Câmara Municipal (Town Hall), where Portugal was declared a republic in 1910. Further west, trains arrive from Estoril and Cascais at the Cais do Sodré railway station close to the city’s main market, Mercado da Ribeira 6 [map]. This is a colourful place selling an amazing array of fresh produce, including fish landed at the nearby Ribeira dock.

Back in the Praça do Comércio, make a grand entrance through the Arco Rua Augusta into the neat grid of streets which form the main area of Baixa, the lower town. Pedestrianised Rua Augusta provides plenty of diversions along the way as it sweeps up towards Rossio. Shops are definitely the main attraction but, at busy times, street entertainers and balloon sellers lend a carnival atmosphere and pavement cafés bring a relaxed but buzzy feel to the scene. At one time, the streets of the grid represented various crafts, hence names such as Rua da Prata (silver), Rua do Ouro (gold) and Rua dos Franqueiros (haberdashers). Today, many of these streets are home to banks and offices as well as shops.

The neo-Manueline Rossio Station.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Rua Augusta opens into Praça Dom Pedro IV 7 [map], better known by its common name of Rossio, and the focus of major city events for 500 years, until the 18th century. This was where citizens gathered to enjoy carnivals and bullfights or to witness public executions, particularly the autos-da-fe of the Inquisition. Now, cafés, flower sellers, shops, kiosks and traffic create a swirl of activity and colour in a square, which is a great place for a coffee or early evening drink, at rooftop bars such as the eponymous Rossio.

The grand artifice of the Teatro Nacional in Lisbon.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

At the northern end of the square, the Teatro Nacional (Dona Maria II Theatre), built in the 1840s, overlooks the two fountains brought from Paris in 1890, which flank the statue of Dom Pedro IV. They are rather more authentic than the statue, which is a cobbled version of a statue of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico. A ship carrying it from Marseilles to Mexico docked in Lisbon just as news came of the emperor’s assassination. Pressed for cash, the city council snapped it up as the bargain of the day and attempted some remodelling in the hope that no one would notice.

Paço dos Condes de Almada (Palace of the Counts of Almada), just to the east of the theatre, is where the Restauradores (Restorers) conspired in 1640 to wrest power back from the occupying Spaniards. The Igreja de São Domingos nearby oversaw the sentencing of victims of the Inquisition, who had been tried in the palace that once stood on the Teatro Nacional site. South of the church the Praça da Figueira (Fig Tree Square), with its statue of João I, has a quieter ambience.

To the northwest of Rossio is the Estação do Rossio (Rossio Station), with its lovely neo-Manueline facade. Trains from Sintra arrive on the fourth floor, at the level of Bairro Alto (the upper part of town), from where an escalator takes passengers down to Baixo level. They emerge not far from Praça dos Restauradores 8 [map], named in honour of the Restorers. In this square stands the 18th-century Palácio Foz, now used by Turismo de Lisboa as the Ask Me Lisboa tourist information centre. Until 1821, access to the square was closed off to keep out the rabble inhabiting Rossio Square and thereby create a peaceful haven for the gentry. After that it was opened up to the general public and used for celebrations and dances.

The canons and view from Castelo São Jorge.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

East to Alfama

Alfama is the oldest part of the city, and clings tenaciously around the feet of the Castelo de São Jorge. The steep, narrow streets and alleys of this old Moorish quarter spill down to the riverside, and a succession of conquerors over the millennia has left vestiges of their occupation. A tapestry of life unfolds around every corner: drink it all in, but keep a tight hold on your valuables. The area really comes alive on 12 and 13 June for the feast of St Anthony of Padua (1195–1231), the unofficial patron saint of Lisbon, who was born in the area (he acquired his title after a sojourn in Italy).

Head up from Baixa past the Igreja de Madalena, dating from the late 18th century but preserving a Manueline porch from an earlier church. On the left, as the Romanesque facade of the Sé comes into view, is the small church of Santo António da Sé, built on the alleged site of St Anthony’s birthplace.

Tip

Head to Rua dos Bacalhoeiros in Alfama, to find a wonderful shop full of stuck-in-time design, the Conserveira de Lisboa, which specialises in canned fish.

The Museu Escola de Artes Decorativas.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Seeing the Sé

Dom Afonso Henriques, the first king of Portugal, ordered the Sé 9 [map] (Cathedral; Tue–Sat 9am–7pm, Mon & Sun 10am–5pm; free) to be built soon after banishing the Moors from Lisbon. The first incumbent was an Englishman, Gilbert of Hastings, who fared rather better than the 14th-century Bishop Martinho Anes, who was flung from the north tower for harbouring Spanish sympathies. Today the cathedral’s fortress-like facade stands testament to the turbulent times in which it was constructed. There has been much restoration over the centuries but the two original crenellated towers, softened by the large rose window in between, remain the most striking feature.

Inside, the barrel-vaulted ceiling leads to a low lantern, and to the left, on entry, is the baptismal font where St Anthony was christened in 1195. Further along, in the first chapel on the left, is a beautifully detailed crèche – Nativity scene – by the sculptor Joaquim Machado de Castro. The chancel is 18th century and the ambulatory was remodelled in the 14th century. In the third chapel from the south side of the ambulatory are the tombs of Lopo Fernandes Pacheco and his wife. He was a companion in arms to Afonso IV (1325–57), and responsible for much of the cathedral’s remodelling during those years.

The ruined cloisters are worth the modest entrance fee to view the excavations in what were once the gardens. Vestiges of Moorish buildings overlay Roman remains, and beneath those is evidence of an Iron Age settlement.

In the sacristy is the cathedral treasury (Mon–Sat 10am–5pm) where numerous sacred objects are on view. Of most importance is the casket containing the remains of St Vincent, the official patron saint of Lisbon, which were brought here by the order of Afonso Henriques from Sagres in Algarve. Legend relates how ravens accompanied the boat that carried his remains from Spain and again on the journey from Algarve to Lisbon. To this day, the raven is a feature of Lisbon’s coat of arms.

Still heading uphill, you will reach the Miradouro de Santa Luzia which is a good vantage point to look down over Alfama. The church of the same name is decorated externally with some interesting azulejo panels, one showing the heroic soldier Martim Moniz, who died keeping the city gate open – an act that enabled Afonso Henriques to capture Lisbon.

A little further up is Largo das Portas do Sol ) [map] (Sun Gate), where one of the original city gates once stood. A statue of St Vincent looks out over the city from this popular viewpoint. Terrace cafés provide an excuse to linger, and the 17th-century palace of the counts of Azurara, now the Museu Escola de Artes Decorativas ! [map] (Museum of Decorative Arts; Wed–Mon 10am–5pm), is certainly worth a visit. The museum is a showcase for the work of Portugal’s master craftsmen.

The mighty walls of Lisbon’s Castelo São Jorge.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The Castelo de São Jorge

Perhaps the most beautiful view of the city is from the ramparts of Castelo de São Jorge @ [map] (daily Mar–Oct 9am–9pm, Nov–Feb 9am–6pm), which crowns the first hill east of the city centre. If you want to take the hard work out of the climb up to the castle, you could take a taxi or catch the No. 28 Graça tram to Portas do Sol, then visit the Sé and surrounding sites on the walk down. The castle can be seen from nearly anywhere in Lisbon, serving as an apt and romantic reminder of the capital’s ancient roots. Many of the castle walls and towers are from the Moorish stronghold, although there were earlier fortifications on this site.

After the Portuguese drove out the Moors in 1147, the residence of the Moorish governor, Paço de Alcáçova, became the royal palace of Dom Dinis (1279–1325). It remained a royal residence until Dom Manuel (1495–1521) decided to build a more comfortable abode down by the river. Except for a short period, when Dom Sebastião preferred the military fortification of the castle to the graceful splendour of the palace, it served its time as a barracks and prison until 1939, when it was freed from any official duties.

All that is left now are walls, 10 towers and the remnants of the palace, but shaded gardens, fountains, cafés and a restaurant, presided over by a statue of Afonso Henriques, make it an ideal spot to escape the heat of summer. The miradouro (lookout spot) provides a marvellous panorama of the city, and from here it is possible to pick out many of the city’s landmarks. Further good viewpoints lie to the north at the Baroque Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Graça £ [map] and, beyond that, the even higher Senhora do Monte.

Back down the hill, the Museu do Fado (Largo do Chafariz de Dentro; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm) tracks the development of Portugal’s saudade-charged musical soul.

The Aqueduto das Aguas Livres.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Outside the city walls

A short walk from the castle leads to the Igreja de São Vicente de Fora $ [map] (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm; free). De fora describes the church’s position outside the city walls. It was built on the site of a 12th-century monastery dedicated to St Vincent to commemorate the battle fought by the crusaders to capture Lisbon. The white limestone building, with short twin towers, was designed by Italian architect Filippo Terzi; construction began in 1582, and took more than 40 years.

Of more interest than the church interior are the cloisters (daily; charge), which are covered with 18th-century azulejos depicting La Fontaine’s Fables. The former refectory, off the cloisters, has served as the Pantheon of the Royal House of Bragança since the mid-19th century. Portuguese kings, queens, princes and princesses, the earliest being João IV (who died in 1656), are entombed here.

A flea market, Feira da Ladra % [map] – literally, the Thieves’ Market – takes place on Tuesday and Sunday morning in the Campo de Santa Clara. You must cross this square to reach the Baroque Igreja de Santa Engrácia ^ [map], now the Panteão Nacional (National Pantheon; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm), containing monuments to many of Portugal’s non-royal heroes. Work on this church started in 1682 but was not completed until 1966, giving rise to the Portuguese idiom for a project that is never finished: “obras [works] de Santa Engrácia”. Although the building is in the compact, satisfying shape of a Greek cross, with a central dome, the stamp of Salazar on its eventual completion has left it a somewhat sterile monument.

Back down towards the riverside, opposite Estação Santa Apolónia, the station for international arrivals, is the Museu Militar & [map] (Tue–Sun 10am–5pm). This museum charts Portugal’s military history in paintings and extensive collections of armour and weapons in a building which was, until 1851, the national arsenal.

Head eastward, along the coastal route, paralleling the railway lines, then turn left up Calçada dos Barbadinhos to the Museu da Agua da EPAL * [map] (Water Museum; Mon–Sat 10am–5.30pm; free). Named after the engineer of the Aqueduto das Aguas Livres (for more information, click here), it was the first steam pumping station of its kind in Portugal. The building, in a surprisingly tranquil oasis, records the history of Lisbon’s water supply from Roman times and includes the story of the aqueduct.

Further east stands the tile museum, the Museu Nacional do Azulejo ( [map] (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm). Again, the easiest route runs parallel to the railway track, but you may find it worth taking a taxi. The building was originally part of the Convento da Madre de Deus, founded in 1509 by the widow of João II, Dona Leonor of Lancaster. All that remains of the original exterior is the Manueline doorway, but the 18th-century interior of the main church provides the perfect foil for the national collection of azulejos, in a breathtaking combination of gilded woodwork, blue-and-white Dutch azulejos and superbly painted walls and ceilings. One of the most outstanding tile scenes is a 1730 panorama of Lisbon, some 37 metres (120ft) long. Besides tiles and architecture, there are paintings to admire, a bookshop in which to browse, and a very pleasant café/restaurant.

Looking down from the Elevador de Santa Justa.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Heading east out of the city, 5km (3 miles) upriver, beside the Oriente Metro station, is the Parque das Nacões, the Expo ’98 site, stretching along 2km (1.25 miles) of waterfront. Its attractions include one of the largest sea-life centres in Europe, the Oceanário de Lisboa (daily summer 10am–8pm, winter 10am–7pm), the huge Atlantic Pavilion, the Camões Theatre, a waterside cable-car ride, the Pavilhão do Conhecimento (Tue–Fri 10am–6pm, Sat–Sun 11am–7pm) interactive science museum (lots of fun for children), and the Vasco da Gama Tower, which has a viewing platform with amazing views, and also houses a luxury hotel.

Tip

Save money at Parque das Nacões (www.portaldasnacoes.pt) by buying the Cartão do Parque, which offers admission to the key attractions here, plus 20 percent off bike and audioguide rental.

Looking up at the Elevador de Santa Justa.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Through Bairro Alto

Bairro Alto (the upper quarter) rises to the west of Baixa. This area is renowned for its shops and restaurants. Shoppers can approach via the fashionable Chiado district, looking in at the popular French-owned FNAC department store, built after the 1988 Chiado fire; or have a great coffee in A Brasileira in Rua Garrett, a café favoured by generations of artists and politicians, now rather more by tourists.

The walkway into the Chiado from the top of Raoul Mesnier de Ponsard’s Elevador de Santa Justa ‚ [map] is accessible, and you can take the lift to the top of the tower to the café and viewing platform (daily 7am–9pm, till 11pm in summer).

The walkway, alongside the roofless Convento do Carmo ⁄ [map], used to connect the lift with the Largo do Carmo and entrance to the Museu Arqueológico do Carmo (Tue–Sun June–Sept 10am–7pm, Oct–May 10am–6pm). This remarkable ruin is one of Lisbon’s most poignant sights. It was built by Nuno Alvares Pereira, João I’s young general at the Battle of Aljubarrota (1385), who spent the last eight years of his life here. Left unrestored after the 1755 earthquake, the remains of the nave give the most eloquent reminder of that tumultuous event. Gothic arches soar skywards over a grassy nave, a venue for occasional concerts, while the part that survived serves as an archaeological museum with some curious tombs and an eclectic mixture of exhibits from as far afield as South America and England.

From the convent, turn right on Rua Garrett, then left on Rua Serpa Pinto, to reach Lisbon’s opera house, the Teatro de São Carlos ¤ [map]. La Scala in Milan and the San Carlos theatre in Naples were the inspiration behind the theatre’s construction in 1792, and the Italian influence is obvious.

A short walk to the northwest, along Rua Nova da Trindade, brings you to Igreja São Roque ‹ [map] (St Rock Church; Mon 2–6pm, Thu 9am–9pm, Tue–Wed, Fri–Sun 9am–6pm; free). Behind an unremarkable post-1755 facade lies an opulent interior. The ceiling has been painted to give a beautiful trompe l’oeil effect, and the eight chapels are all individual works of art. There are notable azulejos by Francisco de Matos and an excellent canvas, Vision of St Rock, painted by Gaspar Dias around 1584.

The main draw is the Capela de São João Baptista, said to be the costliest chapel in the world and commissioned in 1742 by João V. Luigi Vanvitelli and Niccolo Salvi designed and built it in Rome, where it was blessed by the Pope, then dismantled and transported to Lisbon. Gold, silver and bronze decorate the extravagant confection of lapis lazuli, alabaster, marble and ivory, central to which is a mosaic of St John. Adjoining the church is the Museu de Arte Sacra, a small but impressive collection of vestments and ecclesiastical furnishings in rich Baroque designs.

The Basilica da Estrela.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Wine and water

If you continue up Rua Dom Pedro V, you will reach the Solar do Instituto do Vinho do Porto › [map] (Port Wine Institute; Mon–Fri 11am–midnight, Sat 2pm–midnight; free). A vast selection of ports can be sampled in the cosy bar of this former 18th-century palace. Virtually opposite is the shady São Pedro de Alcântara miradouro (viewpoint), which offers an admirable panorama of the city.

Retro Recipes

Try retro Portuguese drinks at Lisbon’s ultra-cool, renovated kiosks. These were operational originally in the 19th century, but had gradually closed down, only to be reopened, complete with vintage-style tipples and snacks in 2004. The lovely, ornate wrought-iron, circular kiosks are to be found in central locations such as Camões Square, Jardim do Principe Real and Praça das Flores. They don’t serve fizzy drinks or beer, but traditional drinks such as orchata (a chilled almond concoction), lemonade, iced tea, port wine, and some with long-forgotten recipes, such as sweet, refreshing capilé, made with spleenwort (a type of fern) and orange blossom, along with traditional Portuguese snacks, such as cod-fish or olive sandwiches.

The Portuguese delight in gardens, so naturally Lisbon is laced with green spaces. Perhaps the finest of them all is the Jardim Botânico fi [map] (daily summer 9am–8pm, winter 9am–6pm), to the right of the Praça do Príncipe Real, one of the richest such gardens in Europe. Created in 1873, it has a magnificent wall of 100-year-old palm trees, banana trees, bamboo and water lilies, and many tropical plants.

Northwest, up the Rua das Amoreiras, beyond Largo do Rato, is a large, simple building, the Mãe d’Agua das Amoreiras fl [map] (Mon–Sat 10am–6pm), which once stored the city’s water supply, brought in along the Aqueduto das Aguas Livres (enquire at the water museum, click here, about visits).

South from Amoreiras (head down Rua Ferreira Borges into Domingo Sequeira) are the attractive Jardim da Estréla and the splendid late 18th-century Basílica da Estrela ‡ [map], with its great dome and multi-hued marble interior. Close by is the British Hospital, the little English Church of St George, and the adjacent Cemitério dos Ingleses (English Cemetery) where Henry Fielding (1707–54), the author of Tom Jones, was buried, after a trip to the warmer climes of Lisbon failed to cure his gout or asthma.

Guarding the Palácio de São Bento.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Special permission is required to visit nearby Palácio de São Bento ° [map] (east along Calçada da Estréla), now the Portuguese Houses of Parliament. Originally built as a monastery, the palace was transformed into the parliament building at the end of the 19th century and was renovated in 1935.

On the docks at Alcãntara, the Museu do Oriente (Doca de Alcãntara; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm, Fri 10am–10pm), housed in a former fish warehouse, has an interesting collection examining Portugal’s historical links with Asia.

Fact

The towerblock Amoreiras Shopping Centre (daily 10am–11pm) is a popular destination in Lisbon, centrally located and with more than 300 shops covering every category from haute couture to pet supplies. There are also numerous food outlets, a play centre, cinemas, post office and a church.

Down by the river is the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga · [map] (Museum of Ancient Art; http://mnaa.imc-ip.pt; Wed–Sun 10am–6pm, Tue 2–6pm). This, one of Lisbon’s most important museums, is located in a fine 17th-century palace (property of the Counts of Alvor), with a tasteful modern extension. The term “ancient” may be misleading, as most of the exhibits are only a few centuries old, but there are fine displays of 16th-century porcelain, brought back by Portuguese sailors from India, Japan and Macau, and displays of furniture, sculpture and glass.

Perhaps of most interest, the museum’s galleries also hold a wide selection of paintings by Nuno Gonçalves and other artists of the 15th–16th-century Portuguese School (for more information, click here), as well as works by Hieronymus Bosch, Brueghel the Younger, Hans Memling, Giambattista Tiepolo, José de Ribera and other great masters.

The doorway to the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Belém

In a green spacious zone by the river, on the western side of town beyond the Ponte 25 de Abril º [map] and the restaurants and nightclubs around the renovated dock at Alcântara, a number of monumental buildings stand as testimony to Portugal’s maritime past. Belém means Bethlehem, and reflects the country’s involvement with the crusades.

It is here that you will find arguably Lisbon’s most glorious monument, the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos ¡ [map] (www.mosteirojeronimos.pt; Tue–Sun May–Sept 10am–6.30pm, Oct–Apr 10am–5.30pm), built to honour Vasco da Gama and his successful journey to India in 1498, and now a Unesco World Heritage Site. This vast, opulent limestone building, a masterpiece of Manueline (or late Gothic) architecture (for more information, click here), took 70 years to complete.

The main body of the church is breathtakingly high-ceilinged and elegant. Ribbed vaulting, supported by polygonal columns, becomes an eye-catching star-shaped feature where the transepts cross, and elephant-supported tombs are a reminder of India. The delicacy of the sculpting makes the double-storey cloisters well worth a visit.

Built on the western side of the monastery, in the latter part of the 19th century, is a wing that houses the Museu Nacional de Arqueologia ™ [map] (National Museum of Archaeology; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), with an interesting collection of folk art dating from the Stone and Bronze ages. Part of the same wing, the Museu da Marinha # [map] (Maritime Museum; Tue–Sun Apr–Sept 10am–6pm, Oct–Mar until 5pm) tells the story of Portugal’s seafaring discoveries, with redundant royal barges and fishing vessels on display in a separate building.

The Planetário Calouste Gulbenkian ¢ [map] (Planetarium; http://planetario.marinha.pt) behind it gives regular presentations, two or three times a day, mainly in Portuguese, but with some shows in English, Spanish or French.

Nearby stands the huge Centro Cultural de Belém ∞ [map] (www.ccb.pt), opened in 1992; exhibitions and events here are usually excellent. It also contains the ultra-minimalist Museu Colecção Berardo (www.museuberardo.com; Tue–Sun 10am–7pm; free), which contains a dazzling array of modern art, with works by Picasso, Magritte, Warhol, Bacon, Pollock and many more, along with sculpture, photography and installations.

On the bank of the Rio Tejo, on the far side of the broad Avenida da India and a small park, stands the Torre de Belém § [map] (daily May–Sept 10am–6.30pm, Oct–May 10am–5.30pm), on the site where Vasco da Gama and other navigators set out on their explorations. This exquisite little 16th-century fortress is another fine example of the Manueline style, with its richly carved niches, towers and shields bearing the Templar cross.

On the waterfront a short distance away, you can’t miss the impressive Padrão dos Descobrimentos ¶ [map] (Monument of the Discoveries; May–Sept daily 10am–7pm, Oct–Apr Tue–Sun 10am–6pm). Erected in 1960, the monument is a stylised caravel, with Prince Henry the Navigator at the fore gazing seawards and other leading figures of the age behind him.

East of the monument, on the Calçada da Ajuda, rises the ornate rose-coloured Palácio de Belém, which once served as a royal retreat but is now the official residence of the president of the Republic. Adjacent, in what was once the royal riding school, is the Museu Nacional dos Coches • [map] (Coach Museum; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), which houses one of the finest collections of coaches in Europe.

Up the hill to the side of the palace is the magnificent Palácio Nacional da Ajuda ª [map] (Thu–Tue 10am–7pm, Sat 10am–9pm), built after the great earthquake as a royal palace but never completed. It is now used for exhibitions and concerts, and numerous rooms are open to the public.

Tip

The giant Centro Comercial Colombo – with more than 360 shops, including a hypermarket – is opposite the Benfica Football Stadium (Estadio da Luz), the site of the 2004 Euro final. It is open daily 9am–midnight. Colegio Militar Metro.

The manicured gardens of Parque Eduardo VII.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The northern hills

Travelling northeast and crossing the Avenida da Ponte again (all but the most hardy will do this by public transport or taxi), you will find that the Parque Eduardo VII q [map] provides an immediate escape from the clamour of the city and offers magnificent views back down to the Tejo. The park was named to mark the state visit of King Edward VII of England in 1903, which was the first he made to a foreign country after his coronation. In the top left-hand corner of the park, but reached from Rua Castilho, are two greenhouses, the Estufa Quente (Hothouse), originally built to house exotic orchids, and the better-known Estufa Fria (Cold house).

At the southeast corner of the park is the Praça Marquês de Pombal w [map], or the Rotunda, as it is more commonly known. From his lofty perch in the centre, a statue of the Marquês looks out over the city he rebuilt. From here, the Avenida da Liberdade sweeps southwards, linking the Rotunda with the Baixa area. The avenida was developed as a dual carriageway in 1879 and became the epitome of style, with palm trees and water features lining the route. It’s now the best place in Lisbon to shop for big name labels, such as Gucci and Prada. The little Parque Mayer, about two-thirds of the way down, is an enclave of restaurants and theatres, the latter specialising in popular comedy known as revistas, satirical variety shows commenting on current political events.

Long legs at the Jardim Zoológico de Lisboa.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Gulbenkian’s legacy

Instead of returning to Baixa, leave the Parque Eduardo VII by the northern exit and walk northeast for a short way to a large landscaped complex containing the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian e [map] (Avenida de Berna 45; www.museu.gulbenkian.pt; Tue–Sun 10am–5.45pm). The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation was set up by the Turkish-Armenian oil magnate, who was born in Istanbul in 1869 and became very attached to Portugal after being harassed and hounded by the Allies in World War II, and seeking refuge in neutral Portugal. The foundation is the most important funding source for the arts in the country, and there are Gulbenkian libraries and museums throughout the country. When Calouste Gulbenkian died in 1955 his collection, one of the richest private collections in the world, was bequeathed to the nation.

The museum’s contents include displays of Middle Eastern and Islamic art, Chinese porcelain, Japanese prints and gold and silver Greek coins. Among magnificent exhibits from the West are paintings by 17th-century masters like Rubens and Rembrandt, and by Impressionists such as Renoir, Manet and Monet. There are also rich Italian tapestries, and a whole room dedicated to the Art Nouveau creations of René Lalique.

A pleasant walk through the park-like complex leads to the Centro de Arte Moderna (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), which displays the work of 20th-century Portuguese artists, including Paula Rego (for more information, click here).

For a rather different form of entertainment, you can take the Metro one stop northwest to the zoo, or Jardim Zoológico de Lisboa r [map] (www.zoo.pt; daily summer 10am–8pm, winter 10am–6pm), which is set in the attractive Parque das Laranjeiras (Orange Tree Park).

Just southwest of the zoo, on the edge of the Parque Florestal de Monsanto, you will find an unexpected gem in the form of the glorious, pink-washed Palácio dos Marquêses de Fronteira t [map] (guided tours Mon–Sat 10.30am, 11am, 11.30am, noon), built as a hunting villa for the first Marquês de Fronteira in 1640. The house and beautiful formal gardens are decorated with some unusual and captivating azulejos.

The bullring at Campo Pequeno.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Campo Grande: north and south

On Campo Grande you will find the group of pleasant modern buildings that make up the Cidade Universitária y [map] (University), although the nearby Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo u [map], a fort-like building that holds the national archives, is architecturally more striking. In an 18th-century palace at the end of Campo Grande is the Museu da Cidade i [map] a (City Museum; Tue–Sun 10am–1pm, 2–6pm), with an interesting collection of archaeological pieces and engravings that trace the history of the city, housed in the charming Palácio Pimenta.

Heading south along Avenida da República, the large 19th-century bullring, Campo Pequeno, is hard to miss, and is not a bad place to witness one of Portugal’s relatively animal-friendly bullfights.

If you head in the opposite direction, north from Campo Grande up Avenida Padre Cruz, you will reach Parque do Monteiro-Mór. Located in old manor houses in these gardens is the Museu do Trajo e da Moda (Costume and Fashion Museum; www.museudotraje.imc-ip.pt; Tue 2–6pm, Wed–Sun 10am–6pm).