Estremadura and Ribatejo

Although ribboned with silver sand, the coast is not the major attraction in this region. It is inland that you will find some of the country’s finest and best-loved monuments.

Main Attractions

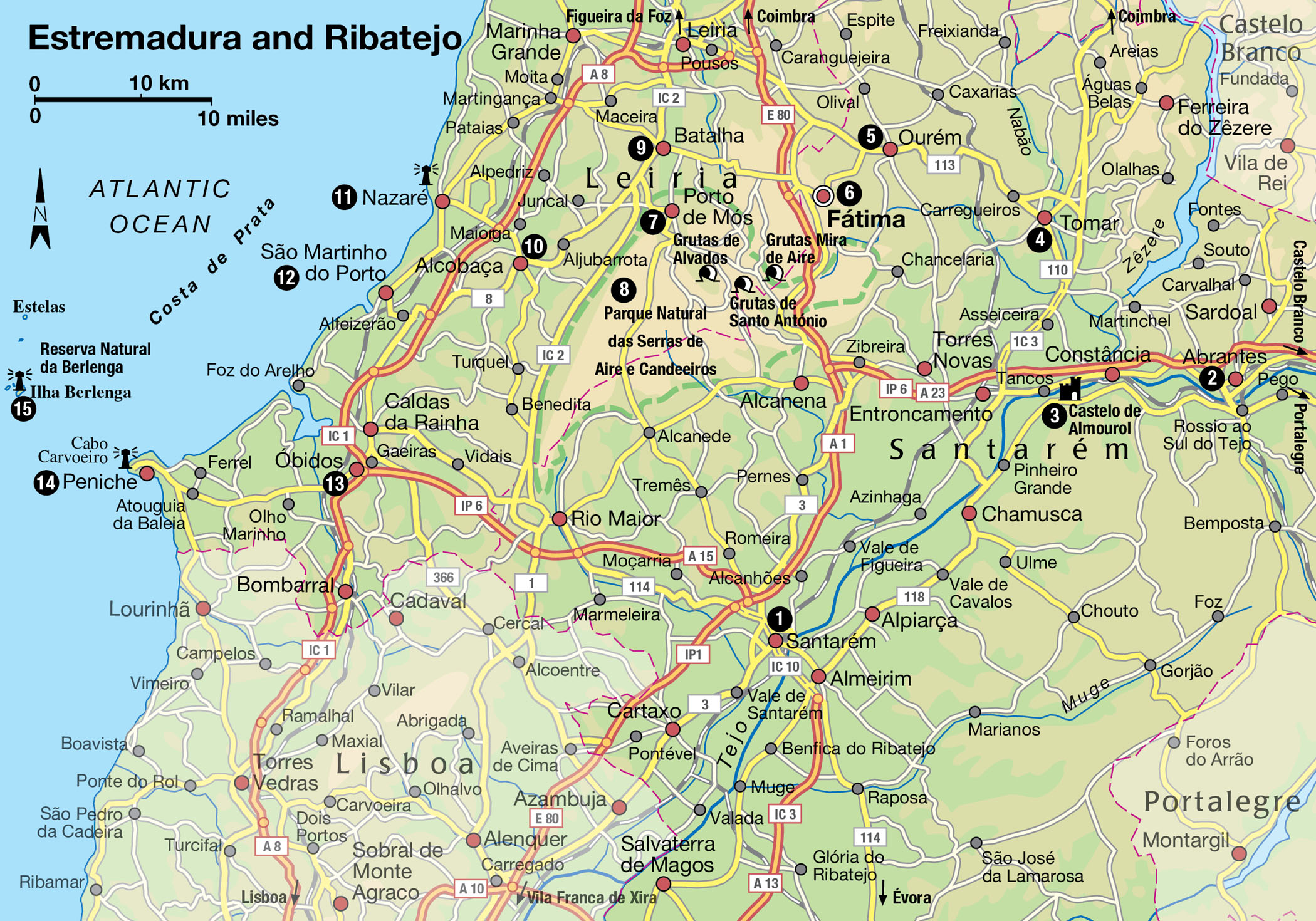

The region north of Lisbon reaching up towards Coimbra has not managed to establish itself as a major travel destination in spite of its many attractions. Bordered by an endless ribbon of silvery sand, the Costa de Prata – the Silver Coast – Nazaré apart, still only has small resorts. Most of the region’s attractions, the monasteries at Alcobaça, Batalha and Tomar, the religious sanctuary at Fátima and the spectacular deep caves in the limestone serras are inland.

With its points of interest fairly widespread, it is an area tailor-made for a rambling tour. Allow around three days to take in most of the major sites and longer if you want to savour everything the region offers. The circular route described here goes anticlockwise from Lisbon up to Batalha and back.

Alcobaça Abbey.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

North from Lisbon

The quickest ways to escape Lisbon are either by the A1 or the A8 heading north. Alternatively, for a slower but more interesting journey, cross the Rio Tejo on the Ponte Vasco da Gama and take the road on the eastern side of the river. The A1 will take you to the modest town of Vila Franca de Xira, the centre of Portuguese bullfighting. Every July and October the town comes alive with the bullfighting festival, known as the Festas do Colete Encarnado (Festival of the Red Waistcoat) after the costumes of the campinos, traditional herdsmen.

Óbidos lacemaker at work.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Santarém 1 [map] is the central town of Ribatejo. It was named after Santa Iria, a young nun who was accused of being unchaste, and martyred in 653 near Tomar. Her body, thrown into the river, washed ashore here. A river-bank shrine has a statue whose feet act as a sacred gauge to the water level – if they are touched by floods, even Lisbon is in danger.

Among several fine churches, the Romanesque-Gothic church of São João de Alporão contains a good archaeological museum (Tue–Sun 9.30am–12.30pm, 2–6pm), as well as the beautifully carved tomb of Duarte, a son of Pedro I who died in battle in 1458. It contains just one of Duarte’s teeth, the sole relic that was delivered to his wife.

In northeastern Santarém is the church of Santa Clara (Tue 2–6pm, Wed–Sun 9.30am–12.30pm, 2–6pm; free), originally part of a 13th-century convent, containing the elaborate tomb of Dona Leonor, daughter of Afonso III. The church of Nossa Senhora da Graça (Wed–Sun 9am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm; free), a Gothic structure with a beautiful nave, holds several tombs, among them that of Pedro Alvares Cabral, discoverer of Brazil.

In Alpiarça, across the river, look for the 19th-century architectural gem of the Casa dos Patudos (Tue–Sun 10am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm, summer to 6.30pm), today a wonderfully eclectic museum containing paintings by Portuguese artists including acclaimed naturalist painter Silva Porto, ceramics and more.

A diversion to Abrantes 2 [map] is worthwhile, if only to see the nearby Castelo de Almourol, romantically located on an island in the middle of the Tejo. The road on the east side of the river offers the most interesting route. Abrantes itself has little to offer visitors except perhaps for the castle of Santa Maria do Castelo.

Turn back along the north bank just before Tancos and look for the sign to Castelo de Almourol 3 [map] (daily Nov–Mar 10am–5pm, Apr–Oct 10am–7pm; free). It crowns a rocky island in the river and the ferryman (Sr João; tel: 914 506 562), who normally operates between 9am and 5pm, will row visitors across for €1.50. A trip around the island will cost more.

The Romans recognised the importance of the site on this key communication route and built a castle, although there may have been an earlier settlement. Later, the castle was occupied by the Visigoths, the Moors and finally the Christians. Afonso Henriques entrusted it to the Knights Templar in 1147 for help in fighting the Moors. The Grand Master Gualdim Pais rebuilt the castle leaving an inscription over the door, and it remained garrisoned for a time. When the Moors were expelled from Portugal the strategic importance of the castle declined and it eventually fell into disuse. It takes only a few minutes to wander around the walls of the fortress.

Tomar

From the castle it is a fairly short run north to Tomar 4 [map], a delightful town with a host of good points: a setting on the banks of the Rio Nabão; the splendid Convento do Cristo, which is a Unesco World Heritage Site; and medieval streets paved with stone and fancifully patterned with exuberant flowers. With its pleasing ambience and rich culture, its ancient legends and appealing daily life, Tomar is a town in which to linger and explore for a couple of days.

Tomar was the headquarters of the Knights Templar in Portugal, an order that was formed in 1119, during the crusades. The order spread quickly throughout Europe, gaining extraordinary wealth. It also made powerful enemies, and in the early 1300s, amid accusations of heresy and foul practices, and finally the suppression of the order altogether, the Knights took refuge in Tomar, where Grand Master Gualdim Pais had built a castle back in 1162. They re-emerged in 1320, reincarnated as the Order of Christ, whose proud symbol, the Cross of Christ, became the banner of the Age of Discoveries.

In Tomar they left behind the marvellous ruins of the old castle and, within its walls, the still-intact church and cloisters. The castle (Tue–Sun June–Sept 9am–6.30pm, Oct–May 9am–5.30pm; free) is set on a hill above the city, a 10-minute walk away, and commands a view over the rooftops of the old town.

The Convento do Cristo was built as part of a defensive system against the Moorish invaders.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Monastery and synagogue

The Convento do Cristo (www.conventocristo.pt; daily Apr–Sept 9am–6.30pm, Oct–Mar 9am–5.30pm) is a maze of staircases and passages, nooks and crannies. The seven cloisters (just four are open to the public) have been added at irregular angles and over several centuries, and even the beautiful main entrance is oddly tucked into a corner. The original Templar church is on the right, just inside the entrance. Begun in 1162, the octagonal temple was modelled on Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Here, the knights would hear services while seated on their horses, and pray for victory in battle.

The chapterhouse and Coro Alto, added much later, provide a sharp contrast to the original temple, as does the adjoining 16th-century cloister with 17th-century tiles where some of the tombs of the knights are found. From here there is access to the upper level and then into the other cloisters. From the terrace of the small Claustro de Santa Bárbara, there is a view of the amazing, ornate Manueline window, structured around two deep relief carvings of ships’ masts, knots, cork, coral and seaweed. The whole is topped by a shield, crown and cross, symbol of the union of church and king.

From the opposite side of the building you can see the castle yard where the knights trained their horses and spent their off-duty hours. Also on this side lies an unfinished chapel: bad luck during construction persuaded the superstitious knights to abandon it.

Tomar’s synagogue in Rua Joaquim Jacinto is now the Museu Luso-Hebraico de Abraão Zacuto (daily July–Sept 10am–1pm, 2–7pm, Oct–June 10am–1pm, 2–6pm; free). Although a high percentage of Portuguese people have Jewish ancestry, and Tomar was once the home of a thriving Jewish community, there are very few Jews left. When King Manuel I married Isabella of Castile in 1497, a condition of the marriage contract was the expulsion of the Jews. They were allowed to remain if they converted, although laws governing fair treatment were not closely monitored. Later, the Inquisition legitimised brutal discrimination against them. The synagogue/museum is simple and moving, decorated with gifts from all over the world.

Other Tomar sights

The church of São João Baptista has a dark wood ceiling and a sombre atmosphere. Sixteenth-century wood-panel paintings on the walls depict scenes such as the Last Supper and Salome with the head of John the Baptist. On the left is a delicately carved pulpit.

Standing alone on the edge of town, Santa Maria dos Olivais is a simple church dating from the 12th century and containing many Templar tombs. The town’s tourist office is on Avenida Dr Cândido Madureira, near the road to the castle, and there is a regional tourist office at 1 Rua Serpa Pinto.

En route from Tomar to Fátima, it is well worth a stop at Ourém 5 [map], or more particularly at Ourém Velha, the fortified site on top of an easily defended hill. The history of the castle is known only from the time it was recovered from the Moors in 1148 by King Afonso Henriques. Little was attempted in the way of restoration until King Dinis (1279–1325) arrived on the scene. He rebuilt this as he did many other castles in Portugal.

Fátima, a place for pilgrims.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The Lourdes of Portugal

Fátima 6 [map], some 12km (8 miles) from Ourém, is not a place for non-believers, and there is even a notice to advise you of this. It is a place for pilgrims – of which there are up to 2 million a year. On 13 May 1917, three shepherd children had a vision of the Virgin here. Thereafter, she appeared before the children and, on one occasion, as a shining light to the townspeople who gathered with them on the 13th of the subsequent months (for more information, click here). The two younger children died shortly after the apparitions, but one, Lucia de Jesus Santos, lived well into her eighties in a convent near Coimbra (she died in 2005). The processions that take place on the anniversaries of the visions – 13 May and 13 October – draw thousands of people from around the world.

Fact

The Virgin revealed three “secrets” to Lucia. The first two were messages of peace, but it was not till June 2000 that the Vatican revealed the third, which prophesied the assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II on 13 May 1981; at the time the Pope declared that Our Lady of Fátima had helped him survive.

Fátima statuary.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Surrounded by acres of car parks is the vast white basilica (May–Oct Mon–Sat 9am–6.30pm, Sun 9am–6pm, Nov–Apr Mon–Sat 9am–6pm, Sun 9am–5.30pm), consecrated in 1953. In front of it is a huge esplanade large enough to hold 100,000 worshippers, and the Chapel of Apparitions, which Our Lady of the Rosaries ordered to be built in her sixth and final appearance on this spot. Inside the basilica lie the tombs of the two visionary children who died, Jacinta and Francisco Marto. Close by is a new church, congress and study centre dedicated to Pope John Paul II (hours as basilica).

Castles and caves

West of Fátima, along scenic well-paved roads, lies the pleasant town of Porto de Mós 7 [map], worth a brief stop even if only to look at the castle (Tue–Sun Oct–Apr 10am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm, May–Sept 10am–12.30pm, 2–6pm), capped with green cones and standing on a hill. The castle has a fairly long pedigree and still contains some original Roman stonework. As with Ourém castle, King Afonso Henriques recovered it from the Moors in 1148. After several restorations, it remained in military use at least until the Battle of Aljubarrota in 1385, when João I is said to have rested his troops here before the fight. Afterwards the king rewarded his captain, Nuno Alvares Pereira, with the gift of this fortress for leading his troops so bravely. It was his grandson, Afonso, a cultured and much-travelled man, who endeavoured to convert the castle into a palace and disguise the strong military lines.

As a change from monuments, a diversion into the Parque Natural das Serras de Aire e Candeeiros 8 [map] offers fine limestone scenery and a chance to visit Portugal’s largest caves. Take the N243 towards Torres Novas to find Grutas Mira de Aire (www.grutasmiradaire.com; daily Apr–May 9.30am–6pm, June, Sept 9.30am–7pm, July–Aug 9.30am–7.30pm, Oct–Mar 9.30am–5.30pm), Grutas de Santo António (www.grutassantoantonio.com) and Grutas de Alvados (www.grutasalvados.com). The latter two lie on a spur off the main road. All three are different enough to be worth visiting. If you only have time for one, then perhaps Grutas Mira de Aire is the best choice. The caves are reached down more than 600 steps through well-illuminated caverns with imaginative and descriptive names, to the underground river. Fortunately, there is a lift for the return to the surface.

Portugal’s largest cave in Parque Natural de Serras de Aire e Candeeiros.

Dreamstime.com

Batalha: an essential stop

Batalha 9 [map] is one of Portugal’s most beautiful monuments, and another Unesco World Heritage Site. The origins of Mosteiro de Santa Maria da Vitória (www.mosteirobatalha.pt; daily Apr–Sept 9am–6.30pm, Oct–Mar 9am–5.30pm), to use its full name, lie in Portugal’s struggle for independence from Castile. One of the decisive battles for independence was fought at Aljubarrota, not far from Batalha. The Castilian king, Juan, who based his claim to the throne on his marriage to a Portuguese princess, invaded Portugal in 1385. The 20-year-old Dom João, Master of the Order of Avis and illegitimate son of Pedro I, promised to raise a monastery to the Virgin Mary if the Portuguese won. With his young general, Nuno Alvares Pereira, João defeated the Castilians, and became João I. The monastery was constructed between 1388 and 1533.

The exterior of Batalha Abbey.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

On the other side of the building you may enter the Claustro Real (Royal Cloister). Arches filled with Manueline ornamentation surround a pretty courtyard and are patterned with intricate designs. The chapterhouse is the first room off the cloister. It has an unusual and beautiful ceiling and its window is filled with a stained-glass Christ on the Cross, remarkably rich in colour. This chamber holds the tombs of two unknown soldiers, whose remains were returned to Portugal from France and Africa after World War I, a war that claimed 8,145 Portuguese soldiers’ lives. The sculpture of “Christ of the Trenches” was given by the French Government, and a photograph of its extraordinary discovery on the battlefields of Flanders can be seen in the refectory opposite, where there is a small World War I museum.

To reach the Capelas Imperfeitas (Unfinished Chapels), go outside the monastery. This octagonal structure is attached to the outside wall and its rooflessness is a shock. Ordered by King Duarte I to house the tombs of himself and his family, the chapel was begun in the 1430s but construction was never finished – no one is quite certain why. The shell contains simple chapels in each of seven walls. The chapel opposite the door holds the tomb of the king and Leonor, his wife. The eighth wall is a massive door of limestone, with endless layers of beautifully detailed ornamentation in carved Manueline style.

The main entrance to Alcobaça Abbey.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Alcobaça

Twelve km (8 miles) south of Batalha is the town of Alcobaça ) [map], named after two rivers, the Alcoa and the Baça. At its heart is the magnificent Cistercian Abbey (www.mosteiroalcobaca.pt; daily Apr–Sept 9am–7pm; Oct–Mar 9am–5pm), yet another Unesco World Heritage Site. The first king of Portugal, Afonso Henriques, founded it to commemorate the capture of Santarém from the Moors. He laid the foundation stone himself in 1148.

The arches of Alcobaça Abbey.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The abbey’s Cistercian monks were energetically productive. Numbering, it is said, 999 (“one less than a thousand” according to records), they diligently tilled the land around the abbey, planting vegetables and fruit. In Sebastião I’s reign, the exceedingly wealthy and powerful Santa Maria Abbey, as it is also known, was declared by the Pope the seat of the entire Cistercian order. The monks here were particularly known for their lively spirits and lavish hospitality. They ran a school, perhaps the first public school in Portugal, and a sanctuary and hospice as well. In 1810, however, the abbey was sacked by French troops. In the liberal revolution of 1834, when all religious orders were expelled from Portugal, the abbey was again pillaged.

The long Baroque facade, added in the 18th century, has twin towers in the centre, below which are a Gothic doorway and rose window surviving from the original facade. Directly inside the serene and austere church, the largest in Portugal, three tall aisles and plain walls emphasise the clean lines. In the transepts are the two well-known and richly carved tombs of Pedro I and Inês de Castro (for more information, click here). Off the south transept are several other royal tombs, including those of Afonso II and Afonso III, and a sadly mutilated 17th-century terracotta of the Death of St Bernard. To the east of the ambulatory there are two fine Manueline doorways that were designed by João de Castilho.

An entrance in the north wall of the church leads to the 14th-century Claustro de Silencio (Cloister of Silence). Several rooms branch off the cloister, including the chapterhouse and a dormitory. There is a kitchen, with an enormous central chimney and a remarkable basin through which a rivulet runs: it supposedly provided the monks with a constant supply of fresh fish. Next door is the refectory, with steps built into one wall leading to a pulpit. To the left of the entrance is the Sala dos Reis, with statues of many of the kings of Portugal, probably carved by monks themselves. The panel in the same room, which tells the history of Alcobaça Abbey, is a rare example of a manuscript azulejo panel.

Alcobaça today is the centre of a porcelain and pottery industry. There are numerous shops around the central square, and some factories welcome visitors.

Powerful waves rock the shore at Costa de Prata.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

The Silver Coast

From Alcobaça, it is a relatively short drive out to the coast to reach the fishing port Nazaré ! [map], which nestles along a sweeping bay. In summer, thousands of holiday-makers pack the beach in rows of peaked, brightly striped canvas tents that create a striking image.

Nazaré, named after a statue of the Virgin that a 4th-century monk brought to the town from Nazareth, lives literally on two levels. In the lower part of town, small, white-walled fishermen’s cottages line the narrow alleyways. High above on the cliff that towers 109 metres (360ft) over the old town is the quarter known as Sítio. Reached by a funicular that climbs the tallest cliffside in Portugal, Sítio is dominated by a large square, and on its edge a tiny chapel, built to commemorate a miracle in 1182, when the Virgin saved the local lord by stopping his horse plunging off the cliff as he pursued a deer.

The 17th-century Nossa Senhora da Nazaré on the other side of the square is the focus of festivities during the second week of September that include processions and bullfights in the Sítio bullring. The steep, narrow pathway and steps from the lighthouse west of the church afford stirring views of Atlantic breakers.

The abundance of tourists vitiates some of Nazaré’s charm, but it also assures that all the visitor’s desires will be catered to. Pleasant seafood restaurants and small hotels line the sandy bay; esplanade cafés, bars and souvenir shops abound. But the life of the hardy fishermen goes on.

Because they had no natural harbour, the fishermen used to launch their boats from the beach. They managed this by pushing their craft down log rollers into the sea then clambering aboard and rowing furiously till they overrode the incoming breakers. When they arrived home again, the boats were winched ashore by oxen and later by tractors. The building of a modern anchorage to the south of the beach has relieved the Nazaré fishermen of this arduous task.

The Nazaré fisherfolk’s traditional dress is today seen more in souvenir shops than on the street. Some women still wear coloured petticoats under a wide black or coloured skirt and cover their heads with a black scarf; the men still favour woollen shirts in traditional plaids, but few wear the distinctive black stocking bonnets.

The medieval market of Óbidos.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications

Calm waters and a walled town

The road south out of Nazaré leads first past the new fishing harbour and then down the coast to São Martinho do Porto @ [map]. Here a huge encircling sandbank creates a virtual lagoon, although there is a small opening to the sea. These calm, shallow waters are readily warmed by the sun but, with only a limited exchange of water, the risk of pollution in the bay is high. Moving south again, the road sweeps grandly by the university town of Caldas de Rainha (Queen’s Spa) – where there is a regular morning fruit market and the charming Museu de Cerâmica (Tue–Sun 10am–12.30pm, 2–5pm; free), which contains local and international ceramics dating from the 17th century. The road then continues on to Óbidos.

A gilded statue in Óbidos church.

Mark Read/Apa Publications

A picture-postcard view of town walls crowned by a castle announces Óbidos £ [map]. The old walled town, its streets tumbling with bougainvillea, presents a well-groomed appearance to the steady influx of day-trippers. The pretty town retains some authenticity, as no new building has been permitted, and only the existing structures within the walls can be used as tea shops, residences and gift shops. Everything in the narrow jumbled streets is painted white, with blue or yellow trimmings, and there are some colourful window boxes.

The town has a long history: it was occupied by the Moors before falling into Christian hands. King Dinis, the indefatigable castle-builder, tidied it up and restored the castelo early in the 14th century. Damaged in the great earthquake of 1755, the castle was subsequently restored and has been converted into a delightful pousada. It is the place where everyone wants to stay, and gets booked up well in advance (tel: 262 955 080).

Apart from wandering around unprotected town walls and enjoying the ambience of the town, there is little to see in the way of monuments. The 17th-century Igreja de Santa Maria (1634–84) dominating the market square attracts the most attention, chiefly for the religious paintings by Josefa de Óbidos, the female artist born in the town in the 17th century.

Fact

Between Óbidos and Peniche some delightful coastal scenery and excellent restaurants make it worth taking a short detour to Baleal, a tiny island joined to the mainland by a causeway. For golfers, the Praia d’El Rey course offers a splendid challenge.

Back to the coast

Like many of Portugal’s coastal towns, Peniche $ [map] has no natural harbour, only a bay sheltered by the rocky promontory of Cabo Carvoeiro, the second most westerly point in Europe. A sea wall has been built to protect the bay. Peniche is a town of around 27,000 people. Here, the spare white houses cling to the slopes for shelter from the sweeping northwesterly winds. Too stark and exposed for tourism to have taken hold, the town typifies life in Portuguese fishing communities.

The Fortaleza physically dominates the town. The veteran leader of Portugal’s Communist Party, Alvaro Cunhal, escaped from this notorious prison in 1960 by climbing down the cliffs to a waiting boat that reportedly took him to a Soviet-bloc submarine. Today, the building serves as a local museum (Tue–Fri 9am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 10am–12.30pm, 2–5.30pm).

You can get a powerful sense of the Atlantic swell that is the fisherman’s constant companion by taking the ferry from Peniche out to Ilha Berlenga % [map], 7km (4 miles) offshore. The ferry runs from June to September and the journey takes an hour (for more on the island, see the box).

The return to Lisbon is best made via the new highway from Óbidos, entering Lisbon via the IC2.

Ilha Berlenga

It’s an adventure to discover Portugal’s beautiful Ilha Berlenga, a rocky chunk of island that looks as if part of the Hebrides drifted out into the Atlantic. Visiting the island, once out of the shelter of the peninsula, powerful currents rock the boat with unexpected force, but the destination is worth the discomfort. A 17th-century fortress, now converted to an inn, a lighthouse and a few fishermen’s cottages are the only buildings.

The entire island has been designated a national bird sanctuary, and seagulls and eider ducks are everywhere. Officials patrol the makeshift paths to ensure that visitors do not disturb the birds. The greatest excitement lies in taking a trip around the reefs, caves and smaller islands, past a breathtaking sea tunnel called the Furado Grande.

Fort of St John the Baptist in Berlenga island.

Fotolia

A mural map of Portuguese exploration.

Lydia Evans/Apa Publications