Chapter 9

Mythological Thresholds of the Paleolithic

I. The Stage of Australopithecus

(3.3–2.1 million b.c.)

“The quest of Adam,” as Herbert Wendt has termed the long search of science for the homeland of the human race, [Note 1] has led now to Africa — and recently with spectacular results. Three types of theory hold the field with regard to the way in which the family tree of our race should be construed. Most of the authorities believe that mankind emerged from the stage of the higher primates along one line of evolution. Those holding this view are known as “monophyletists”: advocates of one (mono) line of descent (phyletikos: “tribe”). A second group, however, the polyphyletists” — advocates of many (poly) lines of descent (phyletikoi) — believe that our race is constituted of a number of independently developed strain which, in the course of the millenniums, became fused. And finally a third group, of recent origin (dating from c. 1925), [Note 2] which as far as I know has not yet received its Greek appellation, stands for the probability of what they term a “zone of hominization,” i.e., a limited yet sufficiently broad area of the earth’s surface, relatively uniform in character, where a large population of closely related individuals (some Tertiary species of higher primate) became affected simultaneously by a series of genetic mutations conducing to the appearance of a considerable variety of manlike forms. [Note 3] Both the evidence of modern genetics and the recent discoveries in South and East Africa of an astonishing variety of early manlike creatures, ranging in stature from pygmies (Plesianthropus*) to giants (Paranthropus robustus), tend to support this latest view. And so the primates that we have now to accept as our first cousins are the higher apes of Africa, the gorilla and chimpanzee, not the orangutan and gibbon of Southeast Asia, who are more remote from the human line, or zone, of hominization. [Note 4]

There are two amusing reports of the behavior of chimpanzees that seem to me worth noting at this point. They appear in Dr. Wolfgang Köhler’s volume on The Mentality of Apes.

Köhler found that his chimpanzees would conceive inexplicable attachments for objects of no use to them whatsoever and carry these for days in a kind of natural pocket between the lower abdomen and upper thigh. An adult female named Tschengo became attached in this way to a round stone that had been polished by the sea. “On no pretext could you get the stone away,” says Köhler, “and in the evening the animal took it with it to its room and its nest.” [Note 5]

Köhler’s second observation is of a social nature. Tschengo and another chimpanzee named Grande invented a game of spinning round and round like dervishes, which was then taken up by all the rest. “Any game of two together,” Dr. Köhler writes,

was apt to turn into his “spinning-top” play, which appeared to express a climax of friendly and amicable joie de vivre. The resemblance to a human dance became truly striking when the rotations were rapid, or when Tschengo, for instance, stretched her arms out horizontally as she spun round. Tschengo and Chica — whose favorite fashion during 1916 was this “spinning” — sometimes combined a forward movement with the rotations, and so they revolved slowly round their own axes and along the playground.

The whole group of chimpanzees sometimes combined in more elaborate motion patterns. For instance, two would wrestle and tumble near post; soon their movements would become more regular and tend to describe a circle round the post as a center. One after another, the rest of the group approach, join the two, and finally march in an orderly fashion round and round the post. The character of their movements changes; they no longer walk, they trot, and as a rule with special emphasis on one foot, while the other steps lightly, thus a rough approximate rhythm develops, and they tend to “keep time” with one another….

“It seems to me extraordinary,” Köhler concludes, “that there should arise quite spontaneously, among chimpanzees, anything that so strongly suggests the dancing of some primitive tribes.” [Note 6]

These two notations will suffice to suggest a spiritual plane for the history of our subject lower than which we need not go in imagining the ritual activities of the first societies. The psychological crisis that we have termed “seizure” is already present, and the joy in group motion patterns that underlies both public ritual and the art of the dance is also in evidence. We note, furthermore, the surprising detail of the central pole, which in the higher mythologies becomes interpreted as the world-uniting and supporting Cosmic Tree, World Mountain, axis mundi, or sacred sanctuary, to which both the social order and the meditations of the individual are to be directed. And finally, we have the wonderful sense of play, without which no mythological of ritual game of “make believe” whatsoever could ever have come into being. One can see already that in play fascinating new energy-evoking stimulae are discovered, which unite groups in the way not of economics but of freely patterned action — that is to say, of art. The observation is worth noting because no actual objects of human art have been found earlier that the Aurignacian period, when the female figurines abruptly appear.

The African finds that have most recently stirred the halls of science are roughly (very roughly) dated at the commencement of the Piacenzian Age, circa 3,300,000 B.C.;*

and at the Fifth International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, held at the University of Pennsylvania in 1956, Dr. Raymond Dart of Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg, South Africa, showed a convincing series of slides in which the implements of this pre-lithic (pre-Stone Age) culture were illustrated. These included the lower jaws of large antelopes, which had been cut in half to be used as saws and knives; gazelle horns with part of the skull attached, which showed distinct signs of wear and use, possibly as digging tools; and a great number of ape-man palates with the teeth worn down — human palates being used to this day as scrapers by some of the natives of the area. But the really sensational slides were those showing a number of baboon and ape-man skulls that had been fractured by the blow of a bludgeon of a certain specific type. All the fractures showed that they had been caused by an instrument having two numbs or processes at the hitting end; and it had required only a little thought on the part of Professor Dart and his collaborators for them to surmise that the probable cause of this double dent was the knob at the end of the leg bone of a gazelle. But apes do not use weapons; ergo, the culprit was a man — or at least some kind of proto-man.

The animal remains found among the bones of these little fellows of about 3 million B.C. have been chiefly antelopes, horses, gazelles, hyenas, and other beasts of the plains — swift runners, so that the art of the hunt must have been considerably developed. Professor Dart, furthermore, has found abundant evidence of a practice of removing the heads and tails of certain of the animals killed, and suggests that the tails may have been used for signaling in the chase. Perhaps so! But what of the removal of the heads? Were the animals flayed, perhaps, and their whole skins, with heads and tails attached, then used in some magical rite to avert the danger of blood revenge? Do we hear an echo at the bottom of the well?

II. The Stage of Homo erectus

(1,890,000–70,000 b.c.)

The first evidence of the use of fire was found about as far from South Africa as one could wish, in the now famous Choukoutien Cave, some thirty-seven miles from Peiping. Here, through a series excavations extending from 1921 to 1939, there was unearthed an impressive assortment of stone tools, cracked skulls, split bones, and fireplaces in what had been the haunt of a sort of ape-man with a brain capacity of about 900 cubic centimeters; that is to say, midway between the men of today (1400-1500 cc. average) and the brainiest ape (600 cc.). The way some of the skulls were opened showed that someone had been knocking holes in them and lapping out the brains. In the cave were the remains, furthermore, of thousands of animals that had also been eaten by the inhabitant, or inhabitants; and the tools of stone were crude choppers and large flakes, such as must have been used for knives.

The unwholesome cannibal of this chilly,

fire-heated den, Sinanthropus Pekinensis, Peking Man (or, as

we may term him, Prometheus the Great), was a contemporary of the

celebrated Java Man and Trinil Man* — who, when his remains were

found in 1891, was hailed by Haeckel and the other

nineteenth-century prophets of evolution as the very figure of

Darwin’s “Missing Link.” But the

remarkable thing about the Chinese find was the evidence of fire in

the cave. For although a number of proto-human remains of this

general period have been found elsewhere in the world, Choukoutien

is unique in its evidence of fire.

We have to think of the period in the vast terms of geological reckoning as falling somewhere between the Early and Late Pleistocene — about 1,890,000 b.c. - 70,000 b.c., in the great ranges of the second glacial period (Mindel) and second interglacial (Mindel-Riss). The chief remains now assigned to this stage in the development of mankind are those, firstly, of Java Man and his like, which now include, in addition to the original find, a massive, brutal skull discovered by Ralph von Koenigswald in the 1930s, as well as a huge lower jaw, also found in Java by the same researcher. Likewise to be classed in this period are the remains of a skull from East Africa that has been dubbed Africanthropus. And then, of course, we have the classic relics of the early paleolithic in Europe, with which every schoolboy is now familiar; most notable Heidelberg Man (Homo heidelbergensis),* whose mighty jaw was discovered in 1907 in a deposit that is now assigned to the first interglacial period (Günz-Mindel) — an age in which the bear, lion, wildcat, wolf, and bison shared with man the fields and forests, along with the wild boar, the Mosbach horse, the broad-faced moose, Etruscan rhinoceros, and straight-toothed ancient elephant. Perhaps also from this period are the interesting Swanscombe skull from the Thames, which was found in 1935 and is probably to be dated in the second interglacial; the Fontechevade skull, found in France in 1947, which appears to belong to the early part of the third interglacial (Riss-Würm); and the skull of a young woman found in a cave at Steinheim, Germany, in 1933, which likewise appears to be from the third interglacial. these latter three, however, have aroused considerable controversy, since they approach far more closely than the Oriental finds the figure of modern man. One side of the argument holds that skulls of this advanced type belong to later periods than those to which their position when found appeared to assign them. The other side contends that two separate strains of evolution are indicated: one developing in the less favorable Pleistocene climates of southeast and far eastern Asia, and the other in the milder spheres of North Africa and Europe. This argument is still unresolved.

What is perfectly clear, however, is that the race of man, by the middle of the second interglacial period (Mindel-Riss), had spread from Africa both northward, into Europe, and eastward (remaining south of the Elburz-Himalayan mountain line) into Southeast Asia, turning then northward up the far eastern coast. Father Wilhelm Schmidt has even suggested the possibility of a continuation of this migration into America. For, as he points out, during the glacial ages the level of the sea was so much lower than now that a land bridge as wide as the nation of France stretched form Siberia to Alaska, across which grazing animals passed — herds of horses, cattle, elephants, and camels. But if animals, then why not their hunters? The land bridge, holding back the icy waters of the Arctic, permitted the warmer currents of the south to flow unhindered up the coast, so that the climate both of Northeast Asia and of Northwest America must have been considerably warmer than today. and Father Schmidt cites to this effect the geologist Dr. W. Krickeberg: “An abundant forest and steppe flora flourished then, where today barren grounds give to the landscape the basic character of a hopeless desert; and this we know since the immigrating Asiatic animal world of the second half of the Ice Age — in whose train, according to this hypothesis, men also come — consisted only to a minor degree of arctic types. The greatest number were the beasts of the northern forests and steppes; among others, the mammoth, whose contemporary, man, must likewise have entered the North American sphere.” [Note 7]

No evidence yet found of paleolithic man in America can be dated, even recklessly, earlier than the third interglacial period (Riss-Würm); but new discoveries during the past few years have been pressing the date line steadily back. In 1925 Dr. Aleš Hrdlicka was suggesting something like 1000 b.c. as a likely date for man’s arrival in the New World. Now we have a date of 6688 +/- 450 b.c. for man in Tierra del Fuego. In 1926 a paleolithic type of spear point (the Folsom Point) was discovered in New Mexico in association with an extinct species of bison. The favored date for this point is c. 10,000 b.c. But two earlier types of point (Sandia and Clovis Flutes) have been found associated with mammoth remains, calling for a date of at least c. 15,000 b.c. The conservative estimates now run up to 35,000 b.c., [Note 8] and some are even prophesying “that the next few years will show the presence man on this continent long before ‘the end of the Pleistocene.’” [Note 9]

All of which, of course, is still a long way indeed from the 400,000 b.c. of Peking; and I am not trying to suggest that the gap will ever be bridged. But what is of interest to our study is the opening, in Father Schmidt’s suggestion, of a possible channel of paleolithic influence from Southeast Asia and the Austro-Melanesian zone, up the coast into the New World. A number of careful scholars of the subject have pointed to signs of an extremely early continuity uniting, not only culturally but also racially, certain peoples of the Southeast Asian area and the most primitive groups in America. The Argentinian anthropologist Jose Imbelloni, for example, recognizes a Tasmanoid (Tasmanian-like) strain in the Yahgans and Alacaloof of Tierra del Fuego; a Melanesian strain among the Indians of the Matto of the Amazon forest; and a semi-Australoid among the nomadic huntsmen of both North and South America. [Note 10] Harold S. Gladwin writes of Australoid skulls discovered all the way from Lower California to the Texas Gulf coast, as well as in Ecuador and Brazil. [Note 11] And Paul Rivet even suggests the possibility of an Australoid migration by way of the ice of Antarctica to Tierra del Fuego. [Note 12] The point to be noticed here is that if any such early paleolithic Southeast Asia-to-Tierra del Fuego continuity should ever be demonstrated, then the last possibility of anything like a pure case for parallel development, even on the simplest level of culture, will have been removed.

On the face of the evidence, it would surely seem that our ponderous Prometheus with the heavy brows was the world’s perfect model of an economic materialist (which is about what one should have expected, considering the size of the brain); for there is not the sign or hint of an artwork to be found in the whole three hundred thousand years of his existence. He was Homo faber, man the tool-maker, par excellence. And the manner in which hes skill increased in the not too easy task of chipping flints, from the days of his first crude pebble tools to those of his finest fist axes, reveals that, for all his rude and even ghoulish habits, he was no unmitigated lout. The high center of human culture was still Africa. Here an incredible abundance of paleolithic tools have been found. Indeed, some excavations (for example, those of L.S.B. Leakey at Olduvai Gorge in the north of Tanzania) have revealed in perfect sequence every stage of the evolution of the hand ax from the pebble tools of man’s first beginnings to the finely finished, really elegant axes of the period of Neanderthal. [Note 13] And if the view into the depth of the well of time that we obtained in the South of France was great, this of Olduvai is simply beyond speech. But what is even more amazing than the profundity of the prehistoric past here illustrated is the broad diffusion over the face of the earth of exactly the same ax forms as those of paleolithic East Africa. As Dr. Carleton S. Coon has remarked: “During the quarter of a million years when man made these tools, the styles changed very little, but what changes were made are to be seen everywhere….This means that human beings who lived half a million years ago were able to teach their young skills that they had learned from their fathers in most minute detail, as living Australians and Bushmen do. Such teaching requires both speech and a firm discipline, and the uniformity of hand-ax styles over wide areas means that members of neighboring groups must have met together at stated intervals to perform together acts that required the use of these objects. In short, human society was already a reality when the hand-ax choppers of the world had begun to turn out a uniform product.” [Note 14]

All of which speaks volumes for the force and reach of diffusion in the primitive world.

Moreover, what is perhaps more remarkable still is that some of the most beautiful of the symmetrically chipped hand axes of this period are as much as two feet long, a size too cumbersome for practical use; the only possible conclusion being that they must have served some ceremonial function. Professor Coon has suggested that such axes were not practical tools but sacred objects, comparable to the ceremonial tools and weapons of later days. “used only seasonally, when wild food was abundant enough to support hundreds of persons at one place and one time. Then the old men,” he supposes, “would cut the meat for the assembled multitude with some of these heavy and magnificent tools,” after which, like the magically powerful tjurungas of the Australians, the sacred implements would be stored in some holy place. [Note 15]

III. That Stage of Neanderthal Man

(c. >200,000–23,000 b.c.)

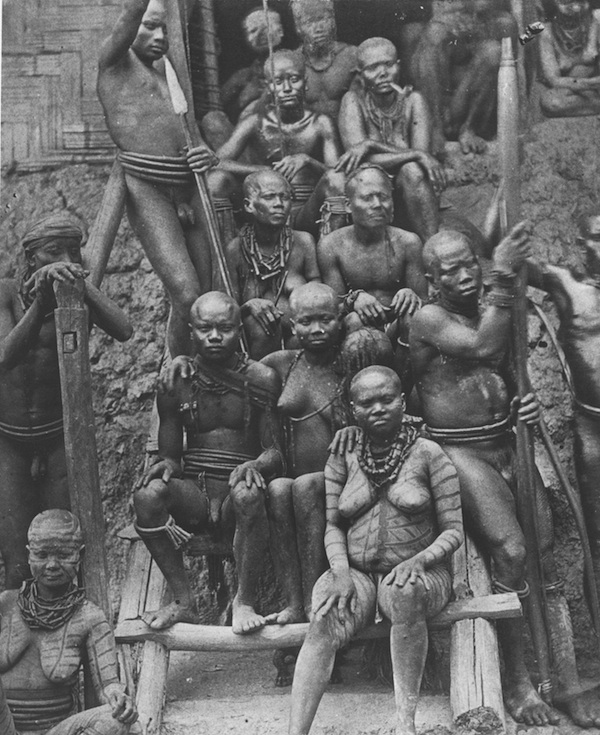

Figure 24. Andaman Islanders

The pygmoid Negritos inhabiting the Andaman archipelago in the Bay of Bengal, some 250 miles south of the last headlands of Burma, had such a reputation for savagery that they were studiously avoided by the sea captains of the Arab, Chinese, and Indian fleets. Unfortunates shipwrecked on their coasts were killed, sliced up, and incinerated. The report was that they were eaten. And since the wealth of the islands was hardly worth appropriating anyhow — consisting of a species of pig, a civet cat, a few kinds of bat and rat, a tree shrew, and a prolific monitor lizard that could swim in the water, walk of land, and climb trees, and so supplied an excellent theriomorphic prototype of the mythological “master of the three worlds” but was of little use for anything else- — the inhabitants survived into the twentieth century a.d. on the cultural level of about the two hundredth b.c.

The eight or then open-fronted thatch shelters of a local group of some forty or fifty men, women, and children are still placed around an elliptical cleanly swept dance area, with a sounding log at one end to be struck by the foot, where, at night, when the daily chores are done, the women sit on the ground and sing, clapping their thighs, while their little men dance round and round.

“In the dance of the Southern tribes,” writes Dr. Radcliffe-Brown, whose fine monograph on this society is a classic of modern anthropological research, “each dancer dances alternately on the right foot or on the left. When dancing on the right foot, the first movement is a slight hop with the right foot, then the left foot is raised and brought down with a backward scrape along ht ground, then another hop on the right foot. These three movements, which occupy the time of two beats of the song, are repeated until the right leg is tired, and the dancer then changes the movement to a hop with the left foot, followed by a scrape with their right and another hop with the left.” [Note 16] If the reader will now test himself, first with the dance step of Köhler’s apes and then with that of Radcliffe-Brown’s Andamanese, he will agree, I think, that we are not being overbold in suggesting that something about of this order can have served to express mankind’s “amicable joie de vivre” through the millenniums of those first and hardest millions of years.

Among the Andamanese there is no organized government of any kind. The affairs of the community are regulated by the elder men and women. But in each local group there was usually found also one younger man who by his genial character, skill in the hunt, kindness, and generosity had won regard of his friends to such a degree that they looked up to him for leadership and advice. And finally, there were those men and women who exerted an influence because they were credited with supernatural powers; such powers, according to Radcliffe-Brown, having been acquired through converse with the spirits, either through death and recovery, through meeting spirits in the jungle, or through dreams. The myths, furthermore, were in the particular charge of these supernaturally endowed men and women.

And so, once, we find in this living museum of the Andaman archipelago a circumstance that must represent — at least approximately — the elementary level of the order of human life: the force of the wisdom of the elders; the tact, grace, and competence of socially oriented individuals; and the interior depth-experiences of the “tender minded.” Add the inevitable “child’s concept of the world,” represented in such a society by the considerable fraction of its population under seven years of age, and you will have an elementary diagram of the structuring force centers from which the constellations of the mythological kaleidoscope have everywhere been constituted — showing shifts of emphasis, indeed, according to circumstance; showing, also, greatly differing ranges and powers of amplification; but always playing out of these four inevitable, ever-present centers of creative force. Furthermore , since there is no excessive emphasis among the Andamanese either on the male or on the female, the contributions from both poles flow freely into the common fund and there is little of the negative, compensatory, and malignant in their mythology and folklore, save where it has been derived from experiences of the malignancies of nature itself in cyclones, sudden death, disease, and other “acts of God.”

The chief personage in the mythology of these little people is the northwest monsoon, Biliku, who is sometimes pictured as a spider and whose character, in keeping with that of the monsoon itself, is tricky and temperamental, being both beneficent and dangerous. Biliku is usually said to be a female, and we cannot but recognize in this hardly surprising designation a probable projection of the infantile “mother imprint” as well as a comment on das Ewig-Weiblich. For, according to what we know of the workings of the modern psyche, such a projection would be perfectly natural — indeed, inevitable — and need anyone doubt that the same basic psychological laws apply to the Andamanese? The southwest monsoon, Tarai, which is milder than Biliku, is pictured as her husband, and their children are the sun, the moon, and the birds. The sun, furthermore, is the moon’s wife, and their children are the stars; the moon can sometimes turn into a pig.

The mythology has not been systematized, and so a number of versions can be accepted of one event. For example, Biliku, either in a male or in a female form, made the world and then made a man named Tomo, the first of the human race, who was black, like the present Andamanese, but much taller and bearded. Biliku taught Tomo how to live and what to eat. and then Tomo had a wife, Lady Crab. According to one view, Biliku created Lady Crab after teaching Tomo how to live. According to another, Tomo saw her swimming near his home and called to her; she came ashore and became his wife. According to still another account. Lady Crab, already pregnant, come ashore and gave birth to several children who became progenitors of the present race. A different series gives us Lady Dove as Tomo’s wife; another, the moon — who, it will be recalled, is also the husband of the sun. Tomo himself is sometimes the sun. But the reader may recall, too, that in the Andamanese myth already given of Kingfisher’s theft of fire, Biliku caused Kingfisher, the fire-bringer, to lose his wings, so that it was he who became the first man.

Sir Monitor Lizard also is the first man; and his wife is Lady Civet Cat. In the days before his marriage, and when he had just completed his initiation ceremonies, he went into the jungle to hunt pig, climbed up a Dipterocarpus tree, and got caught up there in some way by his genitals. Lady Civet Cat, seeing him in that sorry plight, released him and the two then married and became the progenitors of the Andamanese. [Note 17]

Now the dying and resurrected god of the archaic high civilizations of the Near East, Tammuz-Adonis, for whom the women wept in the Temple of Jerusalem (Ezekiel 8:14) and whose Egyptian counterpart was Osiris, was actually out hunting a wild boar when he was gored in the loin and rendered impotent; he descended in death then to the lower world, and was resurrected only when the goddess, Ishtar- Aphrodite, whose animal is not indeed the civet cat but the lion, descended to the underworld and released him. How are we to explain this correspondence? The answer is to be found in the kitchen middens. Lidio Cipriani in 1952 excavated a series of huge Andamanese kitchen middens, which must have been accumulating for a period of some five or six thousand years. And he found: (1) to a depth of about six inches from the top, European imports, chips of broken bottles, rifle-bullets, pieces of iron, etc.; (2) going deeper for many feet, crab legs that had been used as smoking pipes, the bones of pigs, pottery shards, and well-preserved clam shells; (3) within about three feet from the bottom, no crab-leg pipes, no pig bones, no pottery, and clamshells heavily calcinated, showing that they had been exposed directly to the fire. Conclusion: “The Andamanese,” writes Cipriani, “on their arrival, did not know pottery. Previous to its introduction, food was roasted in the fire or in hot ashes; later, it was boiled in pots…. The first Andamanese pottery is of good make, with clay well worked and well burned in the fire. The more we approach the upper strata, the more it undergoes a degeneration….Bones of Sus andamanensis (the Andamanese pig) begin to appear later than pottery. They become more frequent, the more we approach the top levels. The inevitable conclusion would seem to be that the ancient Andamanese knew neither pottery nor the hunting of pigs. It is likely that both pottery and a domesticated Sus were introduced by one and the same people.” [Note 18] Thus, once again, diffusion even here, and regression: regressed neolithic, along with the great neolithic myth of Venus and Adonis, Ishtar and Tammuz, now transformed by the principle of land-nāma into Lady Civet Cat and Sir Monitor Lizard.

The animals most prominent in the tales of the Andamanese have no social value whatsoever. They are the little neighbors in the forest, and during the mythological age, when Biliku lived on the earth, they were of the company of the ancestors. But they were separated from man by the discovery of fire — which is true enough, since man is protected form the animals at night by his fires, which they fear. Some of the their markings, in fact, were caused by painful contact with the first fire.

Pleasant little animals tales of this kind are known to all the hunting and food-gathering peoples of the world, and are, in fact, spontaneously invented even by children. I should think it safe to assume, therefore, that the category is of immense antiquity. The plots, however, enacted by the various local stock-companies of familiar beasts and birds, greatly vary; and so, if we are to take seriously the warning in the case just cited of the rescue of Sir Monitor Lizard by Lady Civet Cat, we shall have to remember that though the genre of the animal tale is certainly of paleolithic age, the cultural influences represented in the plots may be derived from centers of civilization of a very much higher order than anything visible in the local scene would have led one to expect.

Among the Andamanese a number of the animals used for food are represented as having originally been men. A canoe upset and its occupants became turtles; Lady Civet Cat turned some of the ancestors into pigs; some of the pigs jumped into the sea and became dugongs. The animals killed and eaten, clearly, have a different psychological import for the islanders from those that are simply man’s neighbors in the woods. One thinks of Róheim’s observation, quoted earlier, that “whatever is killed becomes father.” The Andamanese rites of initiation are concerned largely with protecting the initiate against the powers of these food animals. The youngster, whether boy or girl, must abstain from eating the animal for a certain time, and then take his first meal under ceremonial protection. The girl’s initiation begins with her first menstruation, when she must spend three days sitting in a hut, again under ceremonial protection. Other crises requiring protection are the usual ones of birth, marriage, and death. On all such occasions the individuals involved are defended from the powers of the moment by various types of ceremonial ornamentation — red paint, white clay, incised (scarified) designs, decorative plant fibers, shells, etc. — as well as by ceremonial dancing, ceremonial weeping, and the recitation of myths.

And so here we are given our primary view of the force and function of myths and rites. At moments of psychological danger they magically conjure forth the life energies of the individual and his group to meet and surpass the dangers. These may be such as are met by all in the course of their lives at the various in evitable thresholds, or they may be such as are met only occasionally or by very few. A man who has killed another has to be decorated and ceremonially protected. A man who has met ghosts in the forest, in dreams, or in death, requires the protection of myth. The chief sources of danger to an Andamanese, according to Professor Radcliffe-Brown, are spirits: the ghosts of the dead and the hidden powers animating nature. And the chief sources of protection to the individual against these dangers are the rites and folkways, the ceremonials, of the group. [Note 19] “The function of the myths and legends of the Andamanese,” he writes, “is exactly parallel to that of the ritual and ceremonial”; [Note 20] they are “the means by which the individual is made to feel the moral force of the society acting upon him.” [Note 21] But the ultimate origin of all these folkways, ceremonials, myths, and rites, by which the moral force of the society is expressed? Here the authorities differ. I have saved my own ruminations on the problem for my final chapter.

The picture of the Andamanese can be taken as a likely norm for the social situation of the early, semi-nomadic, food- gathering and small-game-hunting societies of the tropical and semi-tropical areas of the primary paleolithic diffusion. A new situation developed, however, when the northern, bitterly cold regions north of the Elburz-Himalayan mountain line were entered, about 200,000 b.c., by our sturdy friends of the Neanderthal race. Apparently the possession of fire and the idea of wearing animal skins to keep out the cold made it possible for the tribes of men to brave in number the rigors of the lands of the north, which offered to those who could enter them the advantage of abundant meat. Moreover, the brain power of the species had considerably increased; for, whereas the range in the period of Pithecanthropus had been from about 900 to about 1200 cc., that of Neanderthal was from 1250 to about 1725 — considerably greater at the upper range, that is to say, than the norm for man today, which, as we have said, is a mere 1400 to 1500 cc. The picture is no longer that of a lot of scattered families of moronic ape-men, but of an extraordinarily sturdy race of human beings, perhaps of a slightly higher mental order than ourselves, fighting it out, at the dawn of what may be considered to be our properly human history, in a landscape calling for every bit of wit and spunk at their disposal.

We do not know what the hunting methods of these Neanderthalers can have been. There was a great disparity between the size of their weapons and the animals that were their prey. The bow and arrow had not yet been invented, but the boomerang, or throwing stick, apparently had. The chase was pursued with wooden, flint-pointed spears, throwing stones, and boomerangs, while the animals sought and slain were the mammoth, rhinoceros, wild horse, bison, wild cattle, reindeer and deer, the brown bear, and the cave bear. These beasts were pursued afoot and met face to face, at close quarters. It is not difficult to see why the courage and stamina of the male in these circumstance should have redounded to his considerable advantage.

However, it is likely, too, that the power of woman’s magic was recognized and accorded something of its due. We have seen how, in the Pygmy rite reported by Frobenius from Africa, the woman’s lifted arms and cry to the sun were essential. And we know that among the circumpolar hunters to this day female shamans are numerous and highly regarded. For, as Ruth Underhill has pointed out, the mysteries of childbirth and menstruation are natural manifestations of power. The rites of protective isolation, defending both the woman herself and the group to which she belongs, are rooted in a sense and idea of mysterious danger, whereas the boys’ and men’s rites are, rather, a social affair. The latter become rationalized in systems of theology. But the natural mysteries of birth and menstruation are as directly convincing as death itself, and remain to this day what they must also have been in the beginning, primary sources of a religious awe. [Note 22]

It would have been toward the close of the period of Neanderthal Man that the first migration into America occurred, if the earliest dates now being suggested are correct; i.e., about 35,000 b.c.

We have already viewed the earliest unmistakable archaeological evidences of man’s religious thought, in the burials and bear sanctuaries of Homo neanderthalensis. We now add, to complete the picture, the observation that a number of the Neanderthal skulls found at Krapina and Ehringsdorf provide evidence also of his ritual cannibalism. They had been opened in a certain interesting way. Furthermore, every one of the unearthed skulls of Neanderthal’s Javanese contemporary, Solo Man (Ngangdong Man), had also been opened. And finally, when skulls opened by the modern headhunters of Borneo for the purpose of lapping up the brains are compared with those of Solo and Neanderthal — the skulls having served, handily, as the bowls for their own contents — they are found to have been opened in precisely the same way. [Note 25]

Remarkable indeed — we might observe in passing — how far cultural patterns can survive beyond the periods of the races among whom they first appear!

What rites were associated with the early headhunt we do not know; but that its spirit was comparable to the head- worship of the bear is likely — particularly in view of the fact that at the five-chambered grotto of Guattari, near San Felice Circeo, on the coast of Italy, some eighty miles southeast of Rome, a Neanderthal skull was recently discovered that had been treated much like the skull of a sacrificed bear. The head having been removed, a hole had been tapped in it for the removal of the brain; the remains of sacrificed animals were preserved in receptacles round about the grotto, and the skull itself, placed on the floor of the cave, was surrounded by a circle of stones.

“O noble Divinity!” We can almost hear the prayer: “Precious Divinity, we adore you. We are about to send you back to your father and mother. When you come to them, please speak well of us and tell them how kind we have been. Please come to us again and we shall again do you the honor of a sacrifice.”

Of interest, furthermore, is the fact that on the summit of Monte Circeo itself stand the ruins of a Roman temple supposed to have been dedicated to Circe, the sorceress who not only transformed Odysseus’ men into swine but also introduced the great voyager himself to the cavernous entrance to the Land of the dead. And the name of the promontory is itself a reference to this belief; for the folk memory has it that the vivid headland — high and beautiful, and nearly surrounded by the sea — was Circe’s Isle.

IV. The Stage of Cro-Magnon Man

(circa 38,000 b.c.–7,000 b.c.)

The dating of the Aurignacian period varies dramatically according to whether the new Carbon-14 estimates are accepted or rejected. The Abbé Breuil rejects them, declaring that they lead to “absurd results” and spans of time “notoriously insufficient.” “We must still wait,” her writes, “until we learn the limits of this technique, which seems less accurate when the material is more that fifteen or twenty thousand years old.” [Note 26] Herbert Kühn holds to a date for the period of c. 60,000 b.c.; [Note 27] the Abbé Breuil, c. 40,000 b.c. Carleton S. Coon, on the other hand, accepting the new evidence, suggests c. 20,000 b.c. [Note 28] A fair norm, considering the fact that the Würm Glaciation was at its peak about 35,000 b.c., whereas the Aurignacian almost certainly followed this peak, would seem to be about 30,000 b.c.

The typical figure of the time — the “signature” of the time, as Weinert terms him — is Cro-Magnon man, straight and tall, with a brain capacity of from 1590 to something like 1880 cc (somewhat greater than the modern average); [Note 29] but a number of other racial strains also appear. Some of these (Chancelade Man, Combe Capelle Man) have been said to resemble the modern Eskimo; others (Grimaldi) suggest types of Italian. In the continent of Africa, where Cro-Magnon remains have been discovered down the whole east coast as far as the Cape, other forms suggest the Bushman. [Note 30]

Four major divisions of the upper paleolithic, the culminating age of the Great Hunt, have been generally recognized: the Aurignacian, the Solutrean, the Magdalenian, and the Capsian.

The Aurignacian

This is the high period of the paleolithic female figurines and of the earliest rock-engraving and painting styles. The mural art is linear and somewhat stiff, though by no means crude or incompetent: one thinks of the tension of the archaic. The bone, ivory, and stone figurines, on the other hand, are boldly stylized — some, indeed, with consummate elegance and in a manner remarkably “modern.”

On the walls of a number of the caves claw marks of the cave bear have been found, and it has been observed that engravings and paintings usually appear near these spots. Thus we may say that the Master Bear was the first teacher of this animal art and where he touched was a proper place for animal magic. The stenciled or colored imprints of human hands likewise appear on the walls, many with mutilated fingers. Thus finger-joint offerings are indicated, like those of the North American buffalo plains. The hand imprints were perhaps placed on the walls in imitation of the imprints of the bear.

The caves were the sites of animal magic and of the men’s rites. They are the underworld itself, the realm of the herds of the underworld, from which the herds of the upper world proceed and back to which they return. They are of the realm and substance of night, of darkness, and of the night sky, their animals being comparable to the stars, which are slain by the sun yet reappear. The mythologies of the animal masters and shamanism, the journey to the other world by way of a ceremonial burial, men’s threshold rites, rebirth, and the masked dance inspired the liturgies of this brilliant age.

The female figurines indicate, furthermore, that a mythology of the goddess existed also, which can have been either complementary or alien to the finger-chopping system of the men’s dancing rites. The goddess suggests a context more closely associated than that of the caves, however, with the tropical areas of the primary diffusion, where a planter’s mythology — or at least the prelude to a planter’s mythology — must by now have come into form.

The classical area of the cavern art is southwestern France and northern Spain; that of the figurines extends, on the other hand, from the Pyrenees to Lake Baikal. Moreover, migrations to America in pursuit of game — roughly, from the Baikal region — were almost certainly in progress before the close of this age.

The Solutrean

The Solutrean was a cold, dry period, when the protecting grottos and rock shelters were abandoned for the grassy plains, which now, replacing the tundra, became the scene of a broadly ranging world of grazing herds and nomadic hunting bands. From the Dordogne to the Mississippi the mammoth hunt was at its peak.

We no longer find images of the goddess in the West European sites, but she is prominent still in the hunting stations of the broad loess lands from eastern Europe to the Baikal zone. Moreover, it has been noted that the female figurines of Predmost in Moravia, Mezin in the Ukraine, and Mal’ta in remote Siberia — which some authorities assign to this period, others, however, to the Aurignacian — bear close comparison with one another. [Note 31] The common hunting ground, by this time, was enormous in extent and freely traversed.

Among the skeletal remains a new race of men, arriving apparently from the east, through Hungary and the Danube basin, and pressing as far as to the Dordogne, is revealed in a series of remains well represented at Brunn, Brux, and Predmost; and the particular talent of these new arrivals was for the fashioning of beautiful spear points. Their skulls, however, suggest a certain drop in the mental niveau, going down as low as to a capacity of about 1350 cc. Animal figurines in the mammoth ivory, as well as figurines of the goddess, and a particular clarity of decorative geometrical design, distinguish many of the sites associated with this race. One of the Brunn skeletons was lavishly adorned with cowrie shells and perforated stone disks, bone ornaments form the ribs of the rhinoceros or mammoth, and mammoth teeth. (A badly damaged ivory figurine, apparently of a male, was also found in this grave, and many of the objects were tinted red.) [Note 32] The race was surely one of vigorous hunting nomads and appears to have continued the cult of the goddess into Solutrean times.

In the type station of the period, at Solutre, in central France, near the Saone, a great open-air camp site has been found, sheltered on the north by a steep ridge and having a fine sunny exposure toward the south, with immense fireplaces and the remains of abundant feasts. Wild cattle and horses, the woolly mammoth, the reindeer, and the stag were abundant; likewise the cave and brown bear, badger, rabbit, wolf, hyena, and fox. The jackal, too, now appears — which in form and character is a precise counterpart of America’s coyote.

All these beasts must have figured prominently in the animal tales of the period, told at night around the fires — some perhaps already in the roles that they are playing to this day, not only in the folklore of hunting tribes but also in our children’s nursery lore and dreams.

The Magdalenian

Another cold, wet period arrived, and the grassy steppes began to give place in Europe to forests of pine. The great herds of the hoofed animals therewith moved toward northern Asia, and with them went many of the hunters; yet in the temple-caves of southern France and northern Spain a firm continuity can be recognized, uniting the Magdalenian with the Aurignacian, as though the intervening Solutrean had been but a passing episode.

The animal forms of the mural art now are masterfully rendered in a powerful, painterly style, with fluent lines and rich coloration, through eyes that had looked at animals in a way that has not been known since, and by hands perfectly trained. this art was magic. And its herds are the herd of eternity, not of time — yet even more vividly real and alive than the animals of time, because their ever- living source. At Altamira the great bulls — which are almost breathing, they are so alive — are on the ceiling, reminding us of their nature; for they are stars. And we recall the mythology of Frobenius’s Congo Pygmies: how the rays of the rising sun slew the herds of the sky. The hunt itself is a heavenly adventure, rendering in time eternal forms. And the ritual of the cave is, so to say, its transubstantiating sacrament.

And so here they are, these heavenly herds, in the primal abyss of the night sky. For according to the logic of this sort of dream, this game of myth, where A is B and B is C, this cave is the timeless abyss of the night, and these paintings are the prototypes, Platonic ideas, or master forms of those temporal herds of earth, which — together with the people — are to play the play of the animal master, the willing death, and the sacramental hunt.

The Magdalenian is the period of the male and female bison of the sanctuary of the Tuc d’Audoubert, the dancing shaman of Trois-Frères, the shamanistic trance and bison sacrifice of Lascaux, and the bear sacrifice of Montespan. The mythology of the Great Hunt is in perfect flower.

But the new animals of an encroaching forest have already begun to appear among the remains — the red deer, the forest horse, the moose, and the fallow deer — so that the great days of the plains are passing. The hunters are turning to the rivers and the sea; harpoons of bone are made for whale and seal. Curiously, too, the stature of the Cro-Magnon hunters themselves has now considerably diminished: 5' 1" and 5' 3" are their typical measurements; no longer 6' and 6' 4". And the brain is down to the capacity of our own today, 1500 cc. [Note 33]

A number of interesting motif discovered in the graves deserve remark. At the Grotto of Les Hoteaux, Ain: a skeleton overlaid with Magdalenian implements, resting on its back, covered with red ochre, and with its thigh bones inverted. At the Grotto of Placard, Charente: seven skulls separated from their bodies for burial; a woman’s skull surrounded by snail shells, many of which were perforated; and two skull tops, fashioned into bowls. At the Grotto of Duruthy, at Sorde, Landes: a skeleton with a necklace and girdle of lion teeth and bear teeth. At Chancelade: the Eskimo-like skeleton already mentioned, legs comparatively short, height not more that 4' 7", covered with several layers of Magdalenian artifacts, and the limbs so tightly flexed that they must have been enveloped in bandages. And, then, finally, at Oberkassel, near Bonn: Two skeletons a yard apart, one female, about twenty years old, and the other male, about forty or fifty; respectively 5' 2" and 5' 3". They were covered with great slabs of basalt, and red coloring matter extended completely over the skeletons and surrounding stones. The bones of animals were present, also a finely carved small bone horse head and a polished bone tool of beautiful workmanship carved with the head of some small animal resembling a marten.

We may recognize in these, besides honor and sacrifice, the hope that the ghost will stay abroad and leave the living alone: the reversed thighs, the separated skulls, the bandaged crouch, and the heavy basalt slabs. The bear and lion teeth are interesting, because these two animals, in the northern bear and African lion-panther rites, respectively, are, as we have seen, equivalent in form. Both animals have their eyes in front, they look ahead, as men do, whereas the other animals have their eyes at the side. The shaman of Trois-Frères is shown staring full face at the viewer. And in North Africa, in the Sahara-Atlas range, there is again a lion staring full-face at the viewer, in a posture suggesting that of the shaman dancer of the French cave and placed in such a way as to be struck by the first rays of the rising sun. Like the dancer, furthermore, he is in a position of mastery over a great field of engraved grazing herds. [Note 34] A mythological association is thus suggested of the bear and lion with the sun, solar eye, slaying eye, and evil eye, as well as with the animal master and the shaman. This must have been for millenniums one of the dominant mythological equations underlying the magic of the paleolithic hunt.

V. The Capsian-Microlithic Style

(c. 30,000-4000 b.c.)

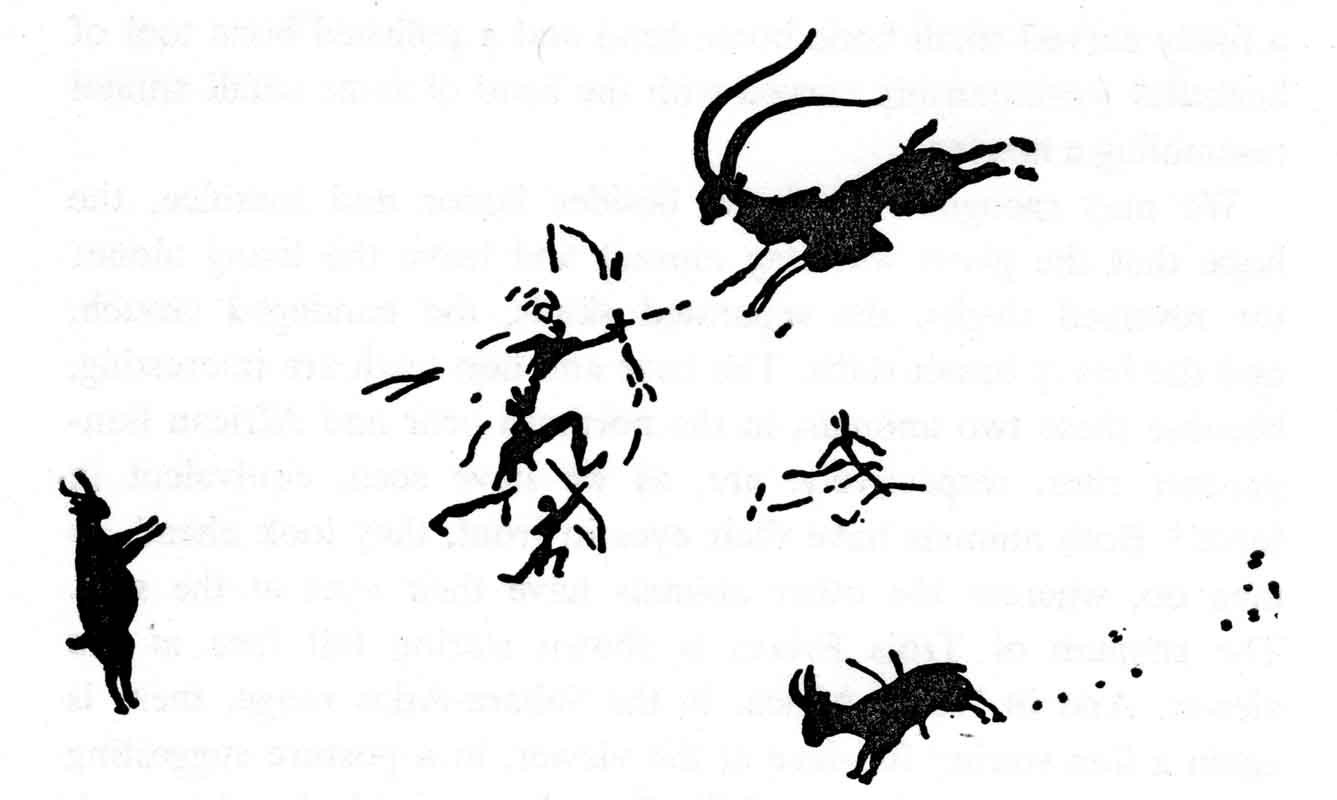

Figure 25. Capsian hunting scene, Castellon.

A hurly-burly of folk movements, new

technologies, mythological orientations, and vivid art forms now

breaks upon the scene, and we are at the opening of a new age. The

bow and arrow have appeared, the hunting dog, and an art of rock

painting alive with vivid forms: bowmen hunting and fighting,

ritual scenes, dancers, sacrificial scenes. whereas the paintings

of the caves specialized in the forms of the animals of the hunt,

here we discover a lively dance of human figures in a wonderfully

vivid stickman style, developed with a sense for the composition of

the scenes and the rendition of movement. And whereas the art of

the caves gave the magical, timeless atmosphere of the realm of

myth, the happy hunting ground of eternity, and the operations

therein of the archetypal shamans, here we have an atmosphere of

life on earth and the ritual acts of living communities.

Figure 26. Three women, Castellon.We note, too, that women

are prominent in the scenes, with elegantly rendered ample hips and

legs, and willowy bodies, gracefully poised. The scenes are vibrant

with the rhythms of the concerted action of groups. Not the shaman

now, but the group is the vehicle of the holy power.

The heartland of this new style was the grassy hunting ground of North Africa, where today there is only desert, and the type station is Capsa (Gafsa) in Tunisia. From there a diffusion westward, turning north into Spain, is to be imagined: Europe’s monuments of the period are in eastern Spain/ But the field extends across the whole of North Africa to the Nile, the Jordan, Mesopotamia, India, and Ceylon. Its characteristic artifact is a tiny geometric flint, chiefly in trapezoid, rhomboid, and triangular forms, commonly known as a microlith, which has been found distributed from Morocco to the Vindhya Hills in India, and form South Africa to Northern Europe. In contrast to this broad diffusion of the tools and weapons, however, the chief reported sites of the art, besides those of eastern Spain, are confined to the Sahara, which of old was a great park and pasture land, full of game. In the rock pictures we see herds of elephants and giraffes, rhinos and running ostriches, monkeys, wild cattle, sheep and gazelles, giant human forms with the heads of jackals or of asses, the ion high on the cliff, struck by the sun, and then, also men standing in postures of adoration, with uplifted arms, before great bulls or before a standing ram with the sign of the sun-disk between its horns. [Note 35]

Figure 27. Man with a dart, Castellon

We know practically nothing of the early history of this culture; not even how far into the past it should be traced. But the earliest forms, known as Lower Capsian, take us back at least as far, it would appear, as the Aurignacian. The break-through into Spain and thence into northern Europe did not occur, however, until about 10,000 b.c., where it is termed, variously, Final Capsian, Tardenoisian, Azilian, microlithic, mesolithic, proto-neolithic, or epipaleolithic. Let us not become confused, however, by names!

The Capsians of North Africa appear to have been a folk of moderate stature, averaging about five to five and a half feet tall, having long heads with retreating foreheads. They hunted with boomerangs, clubs, and bows, speared fish with delicate harpoons, collected berries and roots, and made a great thing of snails and shellfish. They wore beads, disk-shaped, of ostrich-egg shell, feathers, bracelets and girdles of perforated shells. The males — like many innocents of the woman-dominated equatorial zone — instead of concealing, decorated their genitals, while the women wore long stylish skirts. The Natufians of the Mount Carmel caves, on whose appearance, c. 12,500 b.c., we based our dating of the proto-neolithic, were a people of this Capsian culture style. Furthermore, with the progressive desiccation of the Sahara and departure of the teeming game, during the fourth millennium b.c., the Capsians and their painting art moved south, where their influence can be seen in the various styles of South Rhodesia: The graceful hunting scenes of the Bushmen of Basutoland; the now famous, more mysterious “White Lady” of Damaraland (who, it appears, however, is actually a man — “a king.” they say, but no doubt, then, a god-king); and finally, the curious murals of Rusafe, where the sacred regicide and resurrection of the moon-king are celebrated.

And so we are brought back, once more, to our problems of the ritual sacrifice, the dawn of the neolithic, and the mysteries of the monster serpent and the maiden.