Chapter 10

Mythological Thresholds of the Neolithic

I. The Great Serpent of the Earliest Planters

(c. 12,500 b.c.?)

A young woman — we are told — went into the forest. The serpent saw her. “Come!” he said. But the young woman answered, “Who would have you for a husband? You are a serpent. I well not marry you.” He said, “My body is indeed that of a serpent, but my speech is that of a man. Come!” And she went with him, married him, and presently bore a boy and girl; after which the serpent husband put her away, saying, “Go! I shall take care of them and give them food.”

The serpent fed the children and they grew. One day the serpent said to them, “Go, catch some fish!” They did so and returned, and he said, “Cook the fish!” but they replied, “The sun has not yet risen.” When the sun rose and warmed the fish with its rays, they consumed the food, still raw and bloody.

And the serpent said, “You two are spirits; for you eat your food raw. Perhaps you will eat me. You, girl, stay here! You, boy, crawl into my belly!” The boy was afraid and said, “What shall I do?” But the snake said, “Come!” and he crept into the serpent’s belly. The serpent said to him, “Take the fire and bring it out to your sister! Come out and gather coconuts, yams, taro, and bananas!” So the boy crept out again, bringing the fire form the belly of the serpent.

Then, having gathered roots and fruit, as told, they lit a fire with the brand the boy had brought forth, and cooked their food; and when they had eaten, the serpent asked, “Is my kind of food or yours the better?” To which they answered, “Yours! Our kind is bad.” [Note 1]

Here is a legend of the planting world such as might have been told practically anywhere along the tropical arc of the primary migration, from Africa eastward (south of the Elburz-Himalayan mountain line) to southeast Asia, Indonesia, and Melanesia; whereas, actually, its place along the arc was a primitive enclave at the remote eastern end of this great tropical province: the Admiralty Islands, just off the northern coast of New Guinea.

Now the archaeology of the paleolithic periods of Southeast Asia has, unfortunately, hardly been broached; but the bit that we know indicates that the region was far behind Africa in its development of Stone Age tools. Furthermore, as Professor Robert Heine-Geldern has observed: “The paleolithic seems to have lasted here into a very late period. Apparently paleolithic cultures maintained themselves in large parts of the area, particularly in western Indonesia, well into the second millennium b.c., and in places even into much later times.” [Note 2]

Of mythologies open to study in that extremely interesting area, many are undoubtedly of great age. But, as we have seen in the Andaman Island legend of Sir Monitor Lizard and Lady Civet Cat playing the roles of Tammuz and Ishtar, traits from the higher culture spheres can be absorbed even by the most primitive traditions. And yet, on the other hand, as we have seen in the case of the Solo (Ngandong) skulls from c. 70,000 b.c. – 40,000 b.c. treated in the manner of the modern Borneo headhunt, the most amazing conservatism can also be represented in these societies.* Coming across such a trait, therefore, as that of the serpent and the maiden among primitive Papuans, are we to think it a regressed, or a primitive, form of the Fall in the Garden? Or does anyone know, indeed, where this mythological theme first arose?

It is reasonably clear that the widely known mythological theme of the serpent and the maiden first appeared somewhere along the arc of the primary tropical diffusion from Africa through Arabia and the Near East, to India, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, and Melanesia. As we have learned from the evidence of the paleolithic tools, a broad and even fairly rapid diffusion along this arc can be readily demonstrated; however, two major provinces are to be distinguished: (a) that from Africa to India; and (b) that from North-Central India, through southeast Asia, to Indonesia and Melanesia. In the first, a number of developed varieties of the paleolithic hand ax have been found as well as earlier and cruder “pebble tools”; but in the second, only relatively crude types of chopping tool. Furthermore, in the first we have found the vigorous microlithic-Capsian diffusion, which did not extend into the second. So that Province a would appear not only to have been the earlier of the two, but also to have retained the cultural lead at least until the end of the paleolithic.

No one has yet determined where the first steps were taken toward plant cultivation. Menghin has suggested tropical South Asia; [Note 3] Heine-Geldern has termed this idea unlikely, without suggesting an alternative. [Note 4] The only possible alternative, however, is some more westerly part of Province a; which, indeed, would seem to have been the sector — and therewith the likely sector also for our myth of the serpent and the maiden, which, as we have seen, is linked to the idea of the cultivated plant.

We have already spoken of the biological theory of a “zone of hominization”: a limited yet sufficiently broad area of the earth’s surface, relatively uniform in character, where a large population of closely related individuals became affected simultaneously by a series of genetic mutations conducing to the appearance of a considerable variety of manlike forms. I should like now to propose a comparable theory for the origin both of our myth and of the art of cultivating plants, with which it is affiliated. For we can be certain that from one end to the other of Province a there was an effective communication of though and techniques; slow, indeed, according to modern standards — requiring centuries instead of seconds — yet eventually effective, nevertheless. And so we may think of this broad area as a continuum in which a fairly uniform state of human affairs prevailed and which, consequently, was characterized by a fairly uniform state of psychological readiness for the reception of an imprint — a readiness, that is to say, for precisely such “seizures” as that described in our account of the professor’s little girl and the witch. The whole province might therefore be described as a limited yet sufficiently broad area of the earth’s surface, relatively uniform in character, where a large population of closely related individuals (to wit, the members of the relatively recent species Homo sapiens) became affected simultaneously by roughly comparable imprints, and where, consequently, “seizures” of like kind were everywhere impending and, in fact, became precipitated in a ritualized procedure and related myth. We may term such a zone a “mythogenetic zone,” and it should be the task of our science to identify such zones and clearly distinguish them from “zones of diffusion,” as well as from zones of later development and further crisis.

In the case of our present myth, we do not know where, on the great arc of Province a, the idea occurred to some of the women grubbing for edible roots that it would be sensible to concentrate their food plants in gardens; nor do we know whether the idea stemmed from a concept of economy or from some “seizure” and related ritual play. All that is certain is that the functions of planting and of this myth are related and that the myth flourishes among gardeners; moreover, that it can have appeared spontaneously within a broad zone of readiness in more than one place at once; and finally, that within a period which in terms of paleolithic reckoning need not have been long (say, a thousand years) the myths and rites, together with their associated gardening techniques, can have filled the arc. We may guess the date, therefore, to have been somewhere in the neighborhood of 12,500 b.c.

But since we know that a mythology of the goddess was already flourishing earlier than this — having shown itself in the Aurignacian figurines, practically with the first appearance of Homo sapiens on the prehistoric scene — we must recognize that the myth of the serpent and the maiden represents only a development from an earlier base. In the rickety child’s grave at the Mal’ta site, where some twenty female figurines were found, there was an ivory plaque bearing on one side a spiral design and on the other three cobralike snakes. Another spiral was stippled on the side of an ivory fish. The child was in the fetal position, facing east. And there were some ivory birds in the grave.

Now an extremely primitive Papuan tribe, the Baining of New Britain, declare that the sun one day called all things together and asked which desired to live forever. Unfortunately, man disobeyed the summons, and that is why the stones and snakes now live forever, but not man. Had man obeyed the sun, he would have been able to change his skin, from time to time, like a snake. [Note 5]

This symbolism of the serpent of eternal life appearing in the paleolithic period on the reverse of a plaque bearing on its obverse the labyrinth of death; a fish in the same assemblage bearing the labyrinth on its side; the birds, suggesting a flight of the soul in death, as in shamanistic trance; the orientation to the rising sun; and the fetal posture of the little skeleton — these, in a single grave in a site where twenty statuettes of the goddess were discovered as well as a number of ceremonially buried beasts, speak for the presence of a developed mythology in the late paleolithic, in which the goddess of spiritual rebirth was already associated with the symbols of the very much later neolithic cult of Ishtar-Aphrodite: the bird, the fish, the serpent, and the labyrinth.

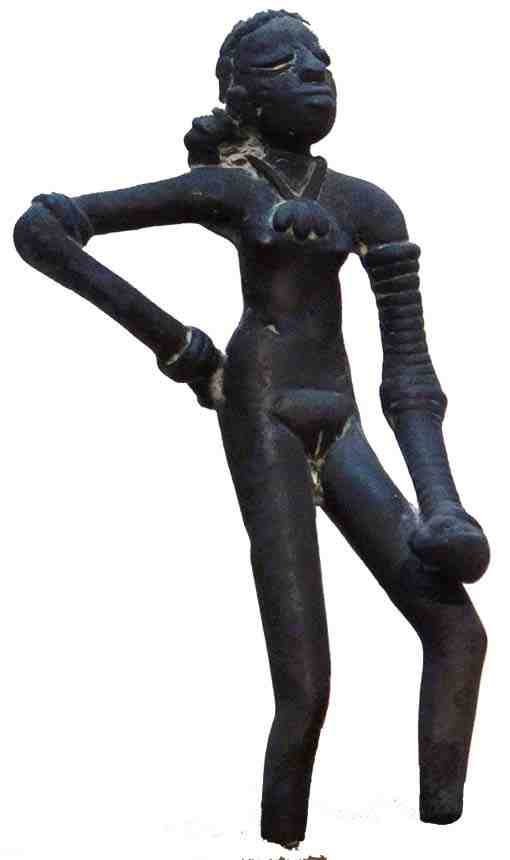

And so we are brought, once again, as always through myth, to the problem of permanence in change, or, as James Joyce says, to what is “ever the same yet changing ever.” And the permanent presence in this particular context is obviously woman, both in her way of experiencing life and in her character as an imprint — a message from the world — for the male to assimilate. The Neanderthal graves and bear sanctuaries, our earliest certain evidences of religious ritual, point to an attempt to cope with the imprint of death. But the mystery of the woman is no less a mystery than death. Childbirth is no less a mystery; nor the flow of the mother’s milk; nor the menstrual cycle — in its accord with the moon. The creative magic of the female body is a thing of wonder in itself. And so it is that, whereas the men in their rites (as initiates, tribal dignitaries, shamans, or what not) are invariable invested with magical costumes, the most potent magic of the womanly body inheres in itself. In all her primary epiphanies, therefore, whether in the paleolithic figurines or in the neolithic, she is typically the naked goddess, with an iconographic accent on the symbolism of her own magical form.

Woman, as the magical door from the other world, through which lives enter into this, stands naturally in counterpoise to the door of death, through which they leave. And no theology need be implied in this, but only mystery and the wonder of a stunned mind before an apprehended segment of the universe — together with a will to become linked to whatever power may inhabit such a wonder. Let us recall the charge of the Blackfoot conductor of the buffalo to his two wives, that they should remain in the lodge that day and pray. “Pray,” is perhaps merely the word of the modern interpreter; better might have been the phrase, “perform their magic,” for, as we have seen, the men’s role in the hunt had to be supported by the magic of their women. However, in the regions of the Great Hunt, where an essentially unbroken masculine psychology prevailed, supported by tokens of prestige, skillful achievement, and the firm establishment of a courageous ego, the feminine principle could be only ancillary to the purposes conceived and executed by the males. The goddess and her living counterparts could give magical support to the men’s difficult tasks but not touch their ruling concept of the nature of being. In the mythologies of that world, or conceived in the spirit of that world, therefore, the fundamental theme is always achievement: achievement of eternal life, magical power, the kingdom of God on earth, illumination, wealth, a good-natured woman, or something else of the kind. The dominant principle is do ut des: “I give so that thou mayest give” — “I give to Thee, O God, so that Thou, in turn, mayest give something nice to me — whether in this life or in the next.”

In the milder regions of the plant-dominated tropics, on the other hand, the feminine side was not simply ancillary but could even establish — out of its own mode of experience- — the the dominant pattern of the culture and its myth. And this is the force that comes to view in the myth of the serpent and the maiden, where the basic elements are: (1) the young woman ready for marriage (the nymph), associated with the mysteries of birth and menstruation, these mysteries (and the womb itself, therefore) being identified with the lunar force; (2) the fructifying masculine semen, identified with the waters of the earth and sky and imaged in the phallic, waterlike, lightning like serpent by which the maiden is to be transformed; and (3) an experience of life as change, transformation, death, and new birth.

The analogy of death and resurrection with the waning and waxing of the moon; the analogy of the water’s disintegration and fructification of the seed with the shadow swallowing and releasing the moon, and therewith, as it were, the moon’s sloughing of its skin of death; furthermore the resemblance of both of these cycles, plant and lunar, to the passing and rising of the generations, as well as to certain spiritual experiences of melancholy and rapture intrinsic to the psyche — these perceived analogies must have constituted then, as they do still, a source both of fascination and of inspiration to at least the more thoughtful members of the species, who at that time may well have constituted an even larger proportion of the population than today.

A diffusion of this mythology and its ritual enactment of the mystery of the monster serpent and the maiden from the mythogenetic zone of Province a must have carried it in due course to Province b, and then eastward into the circum-Pacific area, as well as northwestward from Province a to the Mediterranean. So that the curious myth at the opening of our chapter, of the young woman whose serpent husband gave fire to their children, is almost certainly a descendant of the same tradition that in the Mediterranean sphere produced the legends of Persephone and Eve.

The amazing fact, however, is that in the Admiralty Island version, which is a comparatively primitive variant remaining on a proto-neolithic level, the antithesis that gave Nietzsche so much to think about, between the myths of the feminine Fall and masculine fire-theft, is dissolved — in a single image, full of seeming import, which contains both themes.

It is through just such shifts of emphasis that primitive myth, and the myths of alien worlds, enable us to read anew the once pliant images in our own tradition, which the centuries have embalmed.

II. The Birth of Civilization in the Near East

(c. 12,500 b.c. – 2,500 b.c.)

The concept of the “mythogenetic zone” applied to the stages of our subject already viewed will clarify the main outlines of this natural history of the gods.

Stage I we have termed the Stage of Australopithecus. There can be no question as to where myths and rites arose during this period, if at all. Whatever part of the earth the students of paleontology may ultimately recognize as having been the “zone of hominization” — the part of the earth in which our species stepped away from its less playful, more grown-up, more serious-minded, economically oriented fellows, and began to play games of its own invention instead of only those of nature’s — we shall recognize as our primary “mythogenetic zone.”

The brain capacity of Australopithecus does not promise much in the way of stimulating ideas; nor is the evidence rich enough to give us more than clues for romantic guesses. Yet both the pygmoid and the gigantic hominids of that time must have responded — as all animals do — to the sign stimuli not only of their environments but also of their own bodies and social situations. Also, no less than Köhler’s chimpanzees, they must have enjoyed the playful invention of new situations, games, and organizations. Such games, it is true, are not yet rites. But if the brain of Australopithecus was capable of playing with patterns of thought as well as with patterns of movement, the ground was present for a “seizure” on this level. An individual “seizure” — comparable, on the mental plane, to the chimpanzee’s “seizure” by the round polished stone — would have been a pointer, already, toward the mentality of shamanism, while a group “seizure” — again on the mental plane, but comparable to the fascination of the chimpanzees for their dervish dance of for their dance around the pole — would have produced something like a popular cult. The game, if communicated, would then have established a tradition. And the endurance of the tradition would have depended upon the force of its appeal — that is to say, its power to evoke and organize life energy. In short, if, besides inventing patterns of movement, Australopithecus was capable also of patterns of thought (mythological associations to go along with his ritual games), the first chapter of our science would have begun.

The only tangible evidence of anything of the kind, however, is that curious separation of heads and tails from animal skeletons observed and described by Professor Dart. Theorizing on the basis of this evidence, one might suggest, hypothetically, that the cult of the animal offering with its game of “life beyond death and a pleasant journey home” had already opened its prodigious career. The psychological force of such a play is epitomized in Róheim’s formula: “Whatever is killed becomes father.” The veneration of the food animal, according to this formula, is simply inevitable in a hunting community — provided the inhabitants are actually hominids, not beasts. And that Plesianthropus was a kind of man seems to be indicated by the fact that he brained his prey with a club — with a tool, that is to say — instead of his empty hands and naked teeth.

Stage II, that of Homo erectus (c. 1,890,000 b.c. – 70,000 b.c.), reveals a two-pronged diffusion from the “zone of hominization” (which was probably South and East Africa): (1) northward into Europe (Heidelberg Man), and (2) eastward through the tropical arc to Java, and then northward up the Pacific coast to Peking I. For the primitive mythology of the animal-head cult (if such existed), zones (1) and (2) would thus have been “zones of diffusion.”

However, two new phenomena now appear, and these would seem to indicate the emergence of two new “mythogenetic zones.” The first phenomenon is the elegant development of the hand ax in the western sector of the tropical arc (Africa to western India) and in Europe; the second, the appearance of fire in the gruesome den of Peking Man. Professor J.E. Weckler has observed that throughout much of the early glacial period the eastern end of the tropical arc was cut off from the west by desert and ice, and that, consequently, two separate provinces of human evolution were delineated. [Note 6] In the west, as we have already noted, stone tools developed into beautiful, symmetrically balanced forms, some of which are so large and elegant as to suggest implements for ritual use. In the east, on the other hand, stone tools remained in a relatively primitive state — but fire was discovered and put to use. The mythology and ritual lore of the hand ax, which in later myth and cult became linked to the idea of thunder (Thor’s hammer, the bolt of Zeus, Indra, etc.), would have begun, then in the west, while the mythologies and ritual practices associated with fire would have sprung — like the sun — from the east. We do not know what the early mythologies may have been; but I think it interesting that the bolt in later myth is generally associated with a god, whereas fire in the east is frequently the gift, or even the very body, of a goddess. We have already spoken of the Ainu goddess of the hearth, and have remarked also that the Ainu name of this goddess, Fuji, appears in the name of the sacred volcano Fujiyama. In Hawaii the goddess Pele is the goddess of the dangerous yet beloved volcano Kilauea, where the old chieftains dwell forever, playing their royal games in the flames. And in Malekula, in Melanesia, the journey of the dead leads to and through the goddess guardian of the path to a volcano. In Japan the sun is a goddess and the moon a god; so too in Germany, where the sun is female (die Sonne) and the moon a male (der Mond) — while in France, beyond the Rhine, the sun is le soleil, and the moon, la lune.

There is, in fact, a great mythological area east of the Rhine, where the myth of the moon brother and sun sister is told. Briefly, the tale is of a young woman who at night was visited by a lover whom she never saw. But one night, determining to learn his identity, she blackened her hands in the coals of the fire before he came and, embracing him, left the imprint of his back. In the morning she saw the marks of her own palms on her brother and, screaming with horror, ran away. She is the sun, he the moon. And he has been pursuing his sister ever since. One can see the hand marks on his back, and when he catches her there is an eclipse. This myth was known to the North American Indians, as well as to the northern Asian tribes, and may indeed be of immense age.

It would surely be ridiculous to press the contrast of the feminine fire and the masculine bolt on back to a couple of hypothetical mythogenetic zones of about 400,000 b.c. — but a polarity of some kind is surely indicated in the evidence, and who will say that in the deepest levels of our two culture worlds of east and West (which harbor even greater differences than anyone today cares to think) the dialogue could not still be in progress of the God of the Bolt and the Goddess Fire?

Stage III, that of Neanderthal Man (c. >200,000–75,000/25,000 b.c.), reveals in Central Europe the earliest dependable evidence found anywhere of an establishment of myth and rite: ceremonial burials with grave gear, and bear- skull sanctuaries in high mountain peaks. Professor Weckler has suggested that Homo neanderthalensis may have come from the Oriental zone, pressing west across the tundras into Europe, where he was the first to use fire. [Note 7] Peking Man, it will be recalled, who had already captured fire as early as c. 400,000 b.c., was a cannibal; so also Neanderthal Man: we have mentioned the evidence of the opened skulls at Krapina and Ehringsdorf. But in Java too a number of such opened skulls have been found among the remains of Solo (Ngandong) Man, Neanderthal’s Oriental contemporary; and these were opened precisely in the way of the skulls of the present-day headhunters of Borneo. Neanderthal and Solo Man, therefore, may have practiced some form of ritual cannibalism in connection with an early version of the head hunt; and if so , the formula should perhaps be carried back even to the period of Plesianthropus, who killed and beheaded men as well as beasts — in which case, this grim cult might reasonably be proposed as the earliest religious rite of the human species.

But now, with respect to the earliest employment of fire, a curious problem arises when it is realized that although the heavy-browed family of Peking Man crouched around its hearth as early as c. 400,000 b.c. and that of Neanderthal Man c. 200,000 those lusty brutes gobbled their meals of fresh meat and brains — whether human or animal — absolutely raw. For it was not until the period of the far more highly developed races of the temple caves, c. 35,000 b.c. — 12,500 b.c., that the art of roasting was invented.

But then, why the hearths?

It has been suggested that they were used to heat the caves, [Note 8] and this, indeed, would seem to have been the only practical end to which they were turned. However, even if this were the case, one would still have to ask by what accident Peking Man could have learned that the blast of a forest, prairie, or volcanic fire could have been turned to such congenial use.

A possible answer is provided by the Ainu ritual of the mountain bear ceremonially entertained during his night-long conversation with the goddess of the hearth; for the fire in that context was not a mere device for the provision of heat but the actual presence of a divinity. The earliest hearths, too, could have been shrines, where fire was cherished in and for itself in the way of a holy image or primitive fetish. The practical value of such a living presence, then, would have been discovered in due time.

The suggestion is rendered the more likely, furthermore, when it is considered that throughout the world the hearth fire remains to this day a sacred as well as secular institution. In many lands, at the time of a marriage, the kindling of the hearth in the new home is a crucial rite, and the domestic cult comes to focus in the preservation of its flame. Perpetual flames and votive lights are known practically everywhere in the developed religious cults. The vestal fire of Rome, with its attendant priestesses, was neither for cooking nor for the provision of heat. And we have already learned of the holy fire made and extinguished at the times of the installation and murder of the god-king.

The hearth, then; the mountain sanctuary of the bear; and the ceremonial burial with grave fear, animal sacrifice, and perhaps occasional ritual cannibalism — these, in the period of Neanderthal Man, supply our chief clues to the religious life of a broad middle paleolithic province, documented from the Alps to the arctic Ocean, eastward to Japan and south to Indonesia. But where the mythogenetic zone and where the diffusion zones within this vast area may have been we do not know — though, surely, the earliest points of reference thus far discovered are the bear-skull sanctuaries of the Central European peaks.

And finally, as to the question of other possible mythogenetic zones and ritual syndromes developed during the course of this long period, whether in Africa, western Europe, or Southwest Asia, nothing has yet been found that could be read as evidence. However, it is entirely possible that the cults of the female statuettes and temple caves, which appear abruptly in the following period, were in the process of formation during this earlier, darker day, but have left no evidence; for where wood is abundant as a material for sculpture, and leaves, bark, feathers, etc., for ritual masks, no remains survive. Some part of the great primary field of the tropics, therefore, may have been the mythogenetic zone for the earlier stages of the cults that abruptly appear, already fully formed, in the documented late paleolithic areas of the golden age of the Great Hunt.

Stage IV, then (c. 35,000-10,000 b.c.), reveals the mythology of the naked goddess and the mythology of the temple-caves. The richest finds of the first of these two complexes have turned up in the Ukraine, though the range extends westward to the Pyrenees and eastward to Lake Baikal. Provisionally, therefore, the Ukraine may be designated as the mythogenetic zone; and this likelihood is rendered the more evident when it is considered that many of the basic elements of the complex were to reappear in the neolithic goddess-cults of the fifth millennium b.c., directly to the south, on the opposite flank of the Black Sea.

The relationship of these two goddess-cults to that of the Ainu fire-goddess is probably extremely remote: they appear to have stemmed from different mythogenetic zones. Nevertheless, in the areas of their diffusion they undoubtedly met and possibly were amalgamated. and finally, of course, both represent the imprint of the “permanent presence” previously discussed, namely, woman.

The second mythology of this important era, that of the great temple-caves is definitely centered in northern Spain and southern France — the so-called Franco-Cantabrian zone — and though the cult may have commenced as a provincial form of some earlier masked ritual of the men’s dancing grounds developed in areas to the south, it achieved here a character and ritual investment of such force that the area must be regarded as our first precisely pin-pointed mythogenetic zone; one, furthermore, from whose truly marvelous amplifications of the symbology of the labyrinthine chambers of the soul every one of the high religions and most of the primitive, also, have received instruction.

What a coincidence of nature and the mind these caves reveal! And what an evocation it must have been that drew forth these images! Apparently the cave, as literal fact, evoked, in the way of a sign stimulus, the latent energies of that other cave, the unfathomed human heart, and what poured forth was the first creation of a temple in the history of the world. A shrine is one thing, a temple another. A shrine is a little place for magic, or for converse with a divinity. A temple is the projection into earthly space of a house of myth; and as far as history and archaeology have yet shown, these paleolithic temple-caves were the first realizations of this kind, the first manifestations of the fact that there is a readiness in man’s heart for the supernormal image, and in his mind and hand the capacity to create it. Here, therefore, nature supplied the catalyst, a literal, actual presentation of the void. And when the sense of time and space was gone, the visionary journey of the seer began.

The fashioning of an image is one thing, the

fashioning of a mythological realm another. And the remarkable

fact, it seems to me, is that, for all their complication, these

caves — or at least a number of them — are conceived as units, with

outer and inner chambers of increasing power. Consider, for

example, the composition of the upper cave at Lascaux, with its

scenes of the happy hunting ground and its curious wizard beast

with the pointing-stick horns; and then below, in the crypt, the

shaman and Master Bull, upon whose magical accord the whole happy

hunt above depends. Or consider at Trois-Frères the long flume of

the difficult approach — the difficult journey — leading to the

great chamber of the animals, where the only form with emphasizing

paint upon it was the dancing shaman. In this latter case we are

dramatically confronted by a new thing in the world: the use of a

change of art technique to render a magnification of power. and

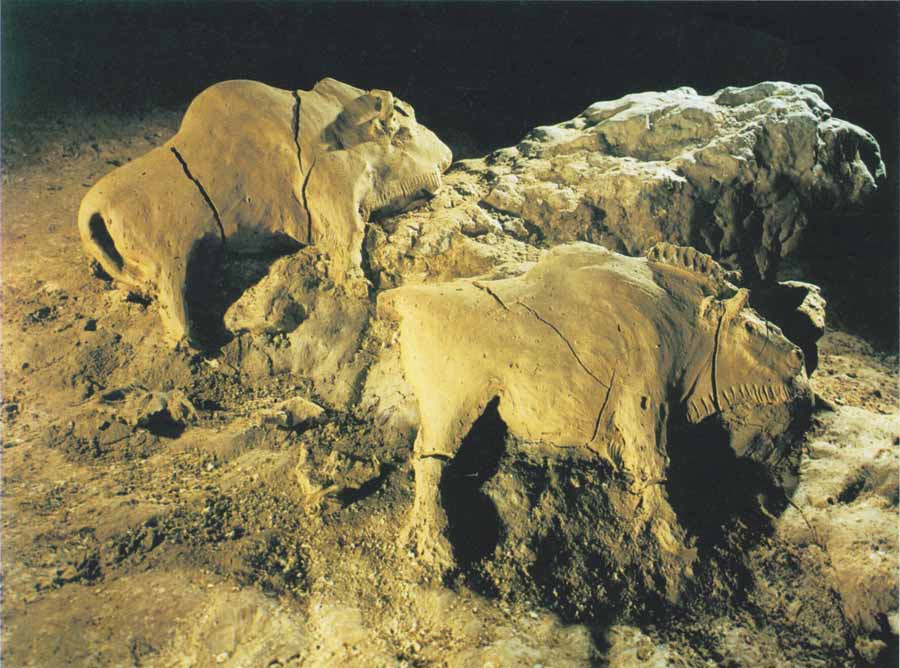

then finally, at the cavern of Tuc d’ Audoubert, the visitor

passes, first, through beautifully painted chambers and then,

clambering through a very small entrance — -which the boys who

discovered the cave called “the cat’s hole,” and going through

which their father, the Count Begouen, got stuck and had to forfeit

both his shirt and his trousers — one arrives in the sanctuary of

the connubium of the two divine bison,

Figure 28. Bison who are rendered not in paint but in bas

relief, not in two dimensions but in three; so that here, once

again, the possibilities of art were being exploited, in a way

never known before, to communicate the sense of a heightening of

the spiritual power sphere. The placement of the shaman in the

crypt of Lascaux, the emphasized form of the dancing shaman of

Trois-Frères, and the plastic rendition of the bison pair of Tuc

d’Audoubert speak volumes for the degree of esthetic sensibility of

the artists of these caves, who were greater men by far than mere

primitive magicians, conjuring animals. They were mystagogues,

conjuring the minds of men.

And so it is, I believe, that we can say that in the mythogenetic zone of the Franco-Cantabrian caves the rendition in art of the mythological realm itself was achieved for the first time in the history of the world. all cathedrals, all temples since — which are not mere meeting houses but manifestations to the mind of the magical space of God — derive from these caves. And I would say, also, that we have here our first certain sign of the operation of the fertilized masculine spirit, the upbeat to La Divina Commedia and to all those magical temples of the Orient wherein the heart and mind are winged away from earth and reach first the heavens of the stars, but then beyond. Though within the earth in these caves, we have left it, on the wings of dream. And this, already, is the wondrous flight so beautifully rendered in Gregory of Nyssa’s image of the “wings of the dove,” as the primary symbol of the Holy Spirit, whereby our nature, “transforming itself from glory to glory,” moves on without bound or ultimate term toward no limit. “For the soul turned toward God, fully committed to its desire for incorruptible beauty, is moved by a desire for the transcendent ever anew, and this desire is never filled to satiety. That is why the dove never ceases to move on toward what is before, going on from where it now is, to penetrate that further to which it has not yet come.” [Note 9] It flies into the shadows, and the shadows continually recede, yet are ever there; for the shadows through which the dove is flying — now and forever — are neither more nor less that “the incomprehensibility of the essence or being of the divine.”

Stage V is represented by the Capsian. The vast diffusion of the microliths, from Morocco to Ceylon and from South Africa to northern Europe, charts the horizon of this new influence. But a much more limited center of creative force is indicated by the distribution of the art works of the period, the chief centers of which are in North Africa and eastern Spain — though with echoes of diffusion southward to the Cape and eastward into those regions that were soon to become the matrices of the next great mythopoetic transformation. The Capsian art, as we have said, is in clear contrast to the Magdalenian. In its passage from north to south, the paleolithic tradition renounced the task of projecting magical realms. Instead, it now is presenting the earthly scenes of a mythologically inspired community almost on the level, we might say, of women’s gossip, or of ethnology. We see the exterior, not so much the interior, of that long-forgotten period of mankind’s spiritual as well as physical development.

Can it be said, then, that we have the evidence here of an impact from the north upon the south? I believe it can. And I would say also that in Stage IV of our sketchy history we had the evidence of an impact from the south upon the north. For it is surely remarkable that in precisely those areas on either side of the Mediterranean where a possibility of cross-fertilization existed in that period of no sailing craft — that is to say, on either side of the comparatively narrow barrier of Gibraltar — the two most impressive heightenings of the paleolithic world of thought and performance come into view.

North Africa, in any case, can be provisionally regarded as the mythogenetic zone of the Capsian rites illustrated on its open-faced rock walls. And if we may judge from the evidence of a number of the scenes, the underlying mythology was almost exactly that which we have already seen represented also in the ritual of the Congo Pygmies. Their picture of a gazelle struck by the rays of the sun and the magical cry of the woman with her lifted arms were vestiges in the twentieth century a.d. of the world’s most advanced thinking of the tenth century b.c.

But in this art we are on the brink of a prodigious transformation, certainly the most important in the history of the world. For among the beasts represented we can identify precisely those types of cattle and sheep that are about to appear as the barnyard stock of the neolithic. Indeed, an only slightly later level of engravings on the same North African rock walls — in the same sites — shows the same animals domesticated. Furthermore, on several of the older engravings of the Capsian period appear superimposed engravings of planetary symbols; for example, on a rock wall in the Sahara-Atlas range, at Jebel Bes Seba, the disk of the sun superimposed upon the head of a ram [Note 10] — reminding us that in Egypt the sun-god Ammun presently would be represented as a ram.

In the broadest terms, the apogee of the Capsian phase of the epipaleolithic, mesolithic, proto-neolithic stage of development (however one may like to name it) we can associate with a time, about 10,000 b.c., “when,” as Dr. Henri Frankfort declares, “the Atlantic rain storms had not yet followed the retreating ice cap northward; when grasslands extended from the Atlantic coast of Africa up to the Persian mountains; and when, in this continuum, the ancestors of both the Hamitic- and the Semitic-speaking peoples roamed with their herds.” [Note 11]

The herds were followed by hunters first, we may imagine, precisely as were the bison of the North American plains, and the first step toward domestication can have been taken when- — as sometimes happened on the plains — a hunting band remained close to a single herd for some time, as if it were a kind of living larder, fighting off alien groups wishing to poach upon it, and killing only a few of its number from day to day. When the possibility of corralling such a herd then dawned on some bright mind — or number of minds — the idea would have spread like wildfire from one extreme of the herding continuum to another — just as, in the tropical arc, the idea of domesticating plants must have spread.

And now, it seems to me extremely significant that the neolithic came into being almost precisely at the point where the hunting continuum described by Dr. Frankfort (“from the Atlantic coast of Africa up to the Persian mountains”) and the tropical arc of our primary diffusion (from South and East Africa, through Arabia, Palestine, Mesopotamia and Iran, to India and Southeast Asia) intersect; namely, the area that old Professor James Henry Breasted used to call “the Fertile Crescent.” It is entirely possible that the idea of domestication passed form one of these two spheres to the other — form the herders to the planters, or vice versa. But in any case, it is surely no accident that the neolithic dawned — and with it civilization — in the Near East, and precisely at the point where the semi-primitive, proto- neolithic arts of plant and cattle cultivation would have met.

Stage VI, the birth of civilization in the Near East, we have outlined in Part Two, Chapter 3. The mythogenetic zone is the Fertile Crescent and its flanking mountains, from the Nile up the cast to Syria, then down to the Persian Gulf. And the phases of the development, sketched in the broadest lines, are four:

1. The proto-neolithic (c. 12,500–7000 b.c.), the phase of the Natufians, which can now be described as an advance form the Capsian, with the promising, highly significant addition of a grain or grass harvest to the provisions of the hunt.

As I have observed, we do not know whether a planting had preceded the harvest or whether the animals killed were yet domesticated. But if the Natufians were not domesticating, they were nevertheless slaughtering the pig, goat, sheep, ox, and an equid of some sort, the same beasts that were later to constitute the basic barnyard stock of all the higher cultures. and if they were not planting, they were nevertheless harvesting some variety of wild or primitive grain. As we have said, the first discoveries of their remains were made in the Mount Carmel caves in Palestine. But similar finds have turned up since, from Helwan in Egypt to Beirut and Yabrud, and as far west as the Kurdish hills of Iraq.

2. The basal neolithic (c. 7000–3500 b.c.), when the foundations of a well-established barnyard economy based on grain agriculture and stock-breeding were already a firmly established pattern and the new style of village living had already begun to spread from the primary zone.

The chief crops were wheat and barley, and the animals domesticated were the pig, goat, sheep, and ox, the dog having already joined the human tribes by the time of the Capsian period, as a companion of the hunt. Pottery and weaving had been added to the sum of human skills; likewise the arts of carpentry and house-building. And then suddenly — very suddenly — the evidence of a new great leap ahead appears in the pottery, the finely fashioned, very beautiful painted pottery of the next phase:

3. The high neolithic (c. 5000–3500 b.c.), when the elegant geometrically organized designs of the pottery styles of Halaf, Samarra, and Obeid appear.

As we observed in Part Two, Chapter 3, this sort of geometrical organization of a field was a new thing in the world at that time and its appearance poses a psychological problem For why should it have been that just when a settled style of village life came into being, an art of abstract forms geometrically organized came into being too? The answer, I believe, is that in the period of the earlier hunting societies there was no differentiation of social functions except along sexual or age lines, every individual was technically a master of the whole cultural inheritance, and the communities were therefore constituted of practically equivalent individuals; whereas in the larger, more greatly differentiated communities of the high neolithic, there had already begun that tendency toward specialization which in the next period was to reach a climax. On the level of a primitive society adulthood consists in being a whole man. In the later, differentiated type of society, on the other hand, adulthood consists in acquiring, first, a certain special art or skill, and then the ability to support or sustain the resultant tension — a psychological as well as sociological tension — between oneself (as merely a fraction of a larger whole) and others of totally different graining, powers, and ideals, who constitute the other necessary organs of the body social. The sudden appearance in the high neolithic of a geometrically composed art form, wherein disparate elements were brought and held together as a balanced whole, seems to me to indicate that some such psychological problem must already have begun to emerge.

We have already noted, too, that in the pottery styles of this period various symbols appear: in the Halaf style of the northwestern area, just southward of the Taurus (Bull) Mountains of Anatolia (now Turkey), the form of a bull’s head in association with figurines of the goddess, and with clay figures of the dove, cow, humped ox, sheep, goat, and pig. It was just to the north of this fruitful area, beyond the Black Sea, in the Ukraine, that a great number of paleolithic figurines of the goddess had appeared in the Aurignacian. That a connection must be supposed would seem to be clear.

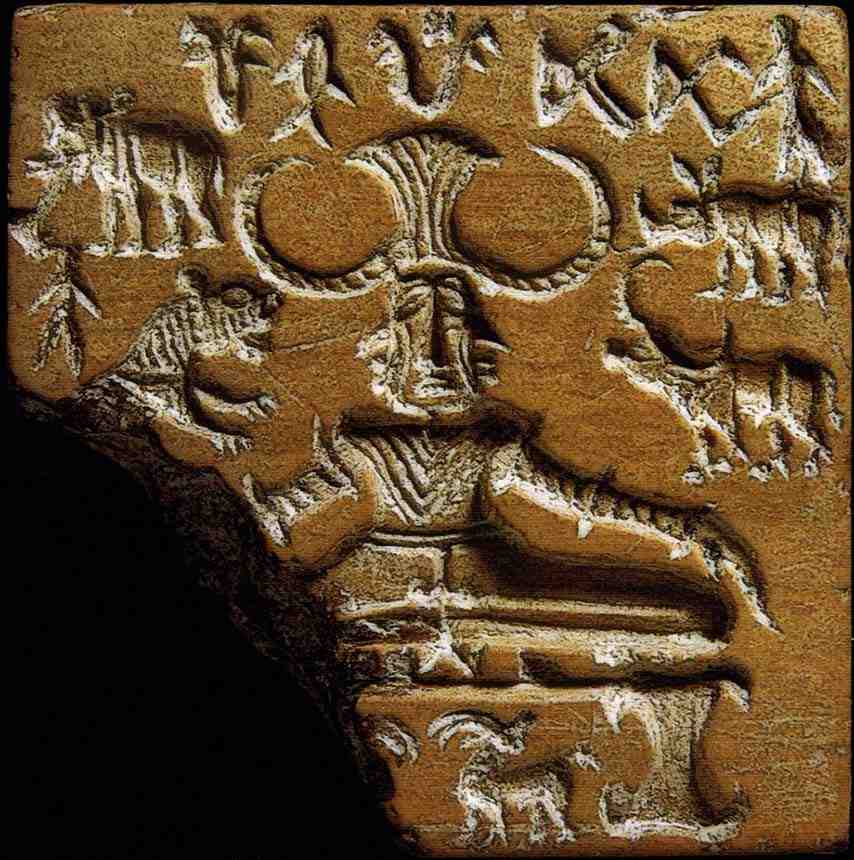

Furthermore, we have noted that the symbols stressed in the Halaf ware are not quite the same as those of the Samarra style, which, with its chief area of distribution farther south and eastward, extended into Iran. The obvious conclusion to be drawn is that a number of mythological systems had been caught in the vortex of the new mythogenetic zone, and this conclusion is supported by the evidence of the later, literate period, when the earliest written documents appear, first in Sumer and then in neighboring Egypt. The impression one gets form these is of a considerable hodge- podge of differing mythologies being coordinated, synthesized, and syncretized by the new professional priesthoods. And how could the situation have ben otherwise, when it was the serpent of the jungle and the bull of the steppes that were being brought together? They were soon to become melted and fused — recompounded — in such weird chimeric creatures as the bull-horned serpents, fish-tailed bulls, and lion-headed eagles that form now on would constitute the typical apparitions of an extremely sophisticated new world of myth.

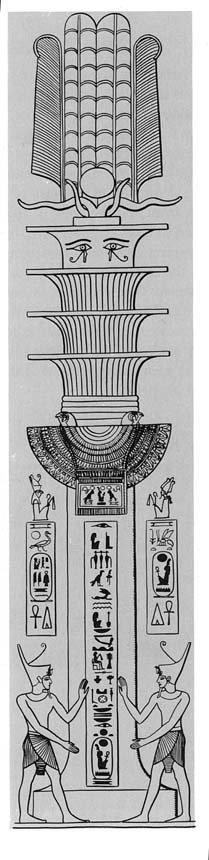

4. In the epoch of the hieratic city state (5400–2500 b.c.), the basic cultural traits of all the high civilizations that have flourished since (writing, the wheel, the calendar, mathematics, royalty, priestcraft, a system of taxation, bookkeeping, etc.) suddenly appear, prehistory ends, and the literate era dawns.

The whole city now, and not simply the temple compound, is conceived of as an imitation on earth of the cosmic order, while a highly differentiated, complexly organized society of specialists, comprising priestly, warrior, merchant, and peasant classes, is found governing all its secular as well as specifically religious affairs according to an astronomically inspired mathematical conception of a sort of magical consonance uniting in perfect harmony the universe (macrocosm), society (mesocosm), and the individual (microcosm). A natural accord of earthly, heavenly, and individual affairs is imagined; and the game is no longer that of the buffalo dance or metamorphosed seed, but the pageant of the seven spheres — Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the moon, and the sun. These in their mathematics are the angelic messengers of the universal law. For there is one law, one king, one state, one universe. And beyond the walls of our little city state is darkness; but within is the order intended form all eternity for man, supported by the pivot of the king, who in his saintly imitation of the moon has purged from his heart all deviant impulse and been transubstantiated. He is the earthly moon, according to that magical law wherein A is B. His queen is the sun. The virgin priestess who will accompany him in death and be the bride of his resurrection is the planet Venus. And his four chief ministers of the state — the lords of the treasury and of war, prime minister, and lord executioner — incarnate the powers, respectively, of the planets Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Sitting about him in his throne room — when the moon is full and he therefore reveals himself, wearing, however, the veil that protects the world from his full radiance — the king and his court are the heavens themselves on earth.

What a marvelous game!

In the neighboring pinpoint on the map, perhaps, the king would be the sun, his queen the moon, and the virgin priestess the planet Jupiter; the game would go by a different set of rules. But no matter what the local rules, wherever this mad dream was played to the limit, the mesocosm of the local state, conceived as a reflection of the universe, was actually a reflection of something from deep within man himself, pulled form his heart as the paintings were in the great caves, evoked now by the void of the universe itself — the labyrinth of the night and its treading adventurers on their mysterious journeys, the planets and the moon.

Moreover, in the symbolism of this new and larger play of destiny, the earlier themes were all subsumed — those of both the monster serpent and the animal master — to produce a far more sophisticated, multidimensional symbolic play, qualitatively different and far more potent, both to evoke and to order the multifarious energies of the psyche, than anything the primitive world had ever produced.

Perhaps the most amazing revelation that has ever come to us of what mythology meant in that remote, heaven-guided age, when the awesome mystery of the planets was enacted on earth by divine kings who at death took with them — back into the night sea — the whole cast of characters of their pageant, has been that of the “royal tombs” of Ur in the cemetery of the sacred Sumerian city of the moon-god Nanna. The excavated graves, as Sir Leonard Woolley, their discover, declares, included burials of two sorts: those of commoners and those of kings — or perhaps, as certain others now suggest, not of kings but of their substitutes, the priests who assumed their roles when their moment came to die. And it was noted that whereas the older of the private graves, though clustered around the royal tombs, were respectful of their sanctity, the newer graves invaded the royal burials, as though, their memory having faded, there had been left in later ages only a vague tradition that this was holy ground. [Note 12]

The first of the royal tombs discovered had been plundered by grave robbers, so that little remained for the twentieth century a.d.; however, something more than even the boldest imagination might have conceived soon came to light. Wrote Sir Leonard Woolley, describing the course of his dramatic discovery:

We found five bodies lying side by side in a shallow sloping trench; except for the copper daggers at their waists and one or two small clay cups they had none of the normal furniture of a grave, and the mere fact of there being a number thus together was unusual. Then, below them, a layer of matting was found, and tracing this along we came to another group of bodies, those of ten women carefully arranged in two rows; they wore head-dresses of gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian, and elaborate bead necklaces, but they too possessed no regular tomb furnishings. At the end of the row lay the remains of a wonderful harp, the wood of it decayed but its decoration intact, making its reconstruction only a matter of care; the upright wooden beam was capped with gold, and in it were fastened the gold-headed nails which secured the strings; the sounding-box was edged with a mosaic in red stone, lapis lazuli; across the ruins of the harp lay the bones of the gold-crowned harpist.

But this time we had found the earth sides of the pit in which the women’s bodies lay and could see that the bodies of the five men were on the ramp which led down to it. Following the pit along, we came upon more bones which at first puzzled us by being other than human, but the meaning of them soon became clear. A little way inside the entrance to the pit stood a wooden sledge chariot….In front of the chariot lay the crushed skeletons of two asses with the bodies of the grooms by their heads, and on the top of the bones was the double ring, once attached to the pole, through which the reins had passed; it was of silver, and standing on it was a gold “mascot” in the form of a donkey most beautifully and realistically modele.

Close to the chariot were an inlaid gaming-board and a collection of tools and weapons,…more human bodies, and then the wreckage of a large wooden chest adorned with a figured mosaic in lapis lazuli and shell which was found empty but had perhaps contained such perishable things as clothes. behind this box were more offerings….The objects were removed and we started to clear away the remains of the wooden box, a chest some 6' long and 3' across, when under it we found burnt bricks. They were fallen, but at one end some were still in place and formed the ring-vault of a stone chamber. The first and natural supposition was that here we had the tomb to which all the offerings belonged, but further search proved that the chamber was plundered, the roof had not fallen from decay but had been broken through, and the wooden box had been placed over the hole as if deliberately to hide it. Then, digging round the outside of the chamber, we found just such another pit as that 6' above. At the foot of the ramp lay six soldiers, orderly in two ranks, with copper spears by their sides and copper helmets crushed flat on the broken skulls; just inside, having evidently been backed down the slope, were two wooden four-wheeled wagons each drawn by three oxen — one of the latter so well preserved that we were able to lift the skeleton entire; the wagons were plain, but the reins were decorated with long beads of lapis and silver and passed through silver rings surmounted with mascots in the form of bulls; the grooms lay at the oxen’s heads and the drivers in the bodies of the cars….

Against the end wall of the stone chamber lay the bodies of nine women wearing the gala head-dress of lapis and carnelian beads from which hung golden pendants in the form of beech leaves, great lunate earrings of gold, silver “combs” like the palm of a hand with three fingers tipped with flowers whose petals are inlaid with lapis, gold, and shell, and necklaces of lapis and gold; their heads were leaned against the masonry, their bodies extended onto the floor of the pit, and the whole space between them and the wagons was crowded with other dead, women and men, while the passage which led along the side of the chamber to its arched door was lined with soldiers carrying daggers and with women….

On the top of the bodies of the “court ladies” against the chamber wall had been placed a wooden harp, of which there survived only the copper head of a bull and the shell plaques which had adorned the sounding-box; by the side wall of the pit, also set on the top of the bodies, was a second harp with a wonderful bull’s head in gold, its eyes, beard, and horn-tips of lapis, and a set of engraved shell plaques not less wonderful; there are four of these with grotesque scenes of animals playing the parts of men….

Inside the tomb the robbers had left enough to show that it had contained bodies of several minor people as well as that of the chief person, whose name, if we can trust the inscription on a cylinder seal, was A-bar-gi; overlooked against the wall we found two model boats, one of copper now hopelessly decayed, the other of silver wonderfully well preserved; some 2' long, it has high stern and prow, five seats, and amidships an arched support for the awning which would protect the passenger, and the leaf-bladed oars are still set in the thwarts; it is a testimony to the conservatism of the East that a boat of identical type is in use today on the marshes of the Lower Euphrates, some 50 miles from Ur.

The king’s tomb-chamber lay at the far end of this open pit; continuing our search behind it we found a second stone chamber built up against it either at the same time, or more probably, at a later period. This chamber, roofed like the king’s with a vault of ring arches in burnt brick, was the tomb of the queen to whom belonged the upper pit with its ass-chariot and other offerings: her name, Puabi, was given us by a fine cylinder seal of lapis lazuli which was found in the filling of the shaft a little above the roof of the chamber and had probably been thrown into the pit at the moment when the earth was being put back into it. The vault of the chamber had fallen in, but luckily this was due to the weight of earth above, not to the violence of tomb-robbers; the tomb itself was intact.

At one end, on the remains of a wooden bier, lay the body of the queen, a gold cup near her hand, the upper part of the body was entirely hidden by a mass of beads of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, agate, and chalcedony, long strings of which, hanging from a collar, had formed a cloak reaching to the waist and bordered below with a broad band of tubular beads of lapis, carnelian, and gold: against the right arm were three long gold pins with lapis beads and three amulets in the form of fish, two of gold and one of lapis, and a fourth in the form of two seated gazelles, also of gold.

Figure 29. Headdress of Queen PuabiThe head-dress whose remains covered the crushed skull was a more elaborate edition of that worn by the court ladies: its basis was a broad gold ribbon festooned in loops round the hair — and the measurement of curves showed that this was not the natural hair but a wig padded out to an almost grotesques size….By the side of the body lay a second head- dress of a novel sort. Onto a diadem made apparently of a strip of soft white leather had been sewn thousands of minute lapis lazuli beads, and against this background of solid blue were set a row of exquisitely fashioned gold animals, stages, gazelles, bulls, and goats, with between them clusters of pomegranates, three fruits hanging together shielded by their leaves, and branches of some other tree with golden stems and fruit or pods of gold and carnelian, while gold rosettes were sewn on at intervals, and from the lower border of the diadem hung palmettes of twisted gold wire.The bodies of two women attendants were crouched against the bier, one at its head and one at its foot, and all about the chamber lay strewn offerings of all sorts, another gold bowl, vessels of silver and copper, stone bowls, and clay jars for food, the head of a cow in silver, two silver tables for offerings, silver lamps, and a number of large cockle- shells containing green paint…, presumably used as a cosmetic.[Note 13]

“Clearly,” writes Sir Leonard at the conclusion of this vivid description of his truly astounding discovery, “when a royal person died, he or she was accompanied to the grave by all the members of the court: the king had at least three people with him in his chamber and sixty-two in the death- pit; the queen was content with some twenty-five in all.” [Note 14]

Several more such tombs were discovered, some even larger than the dual burial of King A-bar-gi and his queen Puabi — he and his court having been buried first and she and hers above, as when the moon sets and the planet Venus follows. In the largest tomb the bodies of sixty-eight women were found, “disposed in regular rows across the floor, every one lying on her side with legs slightly bent and hands brought up near her face, so close together that the heads of those in one row rested on the legs of those in the row above.” [Note 15] Twenty-eight of these women had worn hair-ribbons of gold, and all but one of the rest precisely the same type of ribbon of silver. All had been clothed in red cloaks, having beaded cuffs and shell-ring belts, and they had been adorned with great lunate earrings and multiple necklaces of blue and gold. Four were harpists, and these were grouped together with a copper caldron beside them, which Woolley associates with the manner of their death, suggesting that it contained the drink that bore this multitude through the winged gate to the other world.

“Clearly,” he writes,

these people were not wretched slaves killed as oxen might be killed, but persons held in honor, wearing their robes of office, and coming, one hopes, voluntarily to a rite which would in their belief be but a passing form one world to another, from the service of a god on earth to that of the same god in another sphere….Human sacrifice was confined exclusively to the funerals of royal persons, and in the graves of commoners, however rich, there is no sign of anything of the sort, not even such substitutes, clay figurines, etc., as are so common in Egyptian tombs and appear there to be reminiscent of an ancient and more bloody rite. In much later times Sumerian kings were deified in their lifetime and honored as gods after their death: the pre-historic kings of Ur were in their obsequies so distinguished from their subjects because they too were looked upon as superhuman, earthly deities; and when the chroniclers wrote in the annals of Sumer that “after the Flood kingship again descended from the gods,” they meant no less than this. If the king, then, was a god, he did not die as men die, but was translated; and it might therefore be not a hardship but a privilege for those of his court to accompany their master and continue in his service. [Note 16]

“It is safe to assume,” he says in conclusion, “that those who were to be sacrificed went down alive into the pit. That they were dead, or at least unconscious, when the earth was flung in and trampled down on the top of them is an equally safe assumption…, they are in such good order and alignment that we are driven to suppose that after they were lying unconscious someone entered the pit and gave the final touches to their arrangement….It is most probable that the victims walked to their places, took some kind of drug — opium or hashish would serve — and lay down in order; after the drug had worked, whether it produced sleep or death, the last touches were given to their bodies and the pit was filled in.” [Note 17]

And what of the one young lady without a ribbon either of gold or of silver? Actually, she had had a ribbon of silver on her person. It was discovered among the bones of her skeleton at about the level of the waist: “carried apparently in the woman’s pocket, it was just as she had taken it from her room, done up in a tight coil with the ends brought over to prevent its coming undone.” [Note 18] She had been late, apparently, for the ceremony and had not had time to put it on.

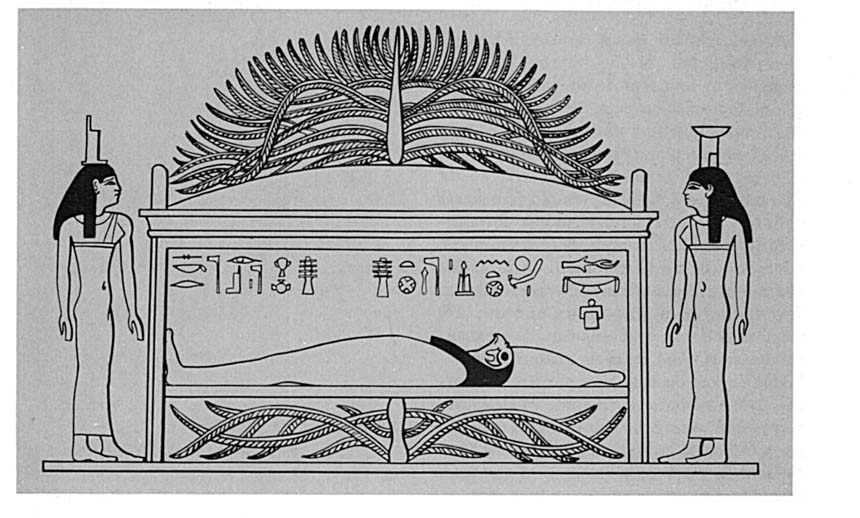

Here, then, is the prototype of the miserable little Shilluk affair of the king buried with a living virgin, whose bones then would be gathered with his into the hide of a bull. For it was the moon-bull, the symbol of the lunar destiny of all things and the mathematics of the universe, that sang to these people their song of dreams. A magical equation had been conceived: the bull and the cow (as in the cavern of Tuc d’Audoubert) :: the monster serpent and the maiden (as in the ritual of the Dema) :: the moon and the planet Venus (which as evening and as morning star is the herald both of night-sleep-death and of dawn-rebirth) :: the fertilizing waters of the abyss and the seed that is to bear much fruit:: the king and the queen.

Among the cylinder seals of Mesopotamia, where many of the basic motifs of the earliest mythology of this dawning age were aphoristically illustrated, there is an image, more than once encountered, in which, on a fleece-covered couch having legs shaped like those of a bull, a male and female lie extended with a priest officiating at their feet. “It seems certain,” Dr. Henri Frankfort observes, “that we have here the ritual wedding of the god and goddess.” [Note 19] But in the period of the hieratic city state (though not in the later periods of Mesopotamia) the god and goddess were incarnate in the king and queen. In the queen’s chamber of the royal tomb, as we have seen, there was “the head of a cow in silver.” The king’s chamber had been plundered, but there were harps fashioned in such a way that their bodies terminated in beautiful heads of gold — the heads of bulls with lapis lazuli beards: mythological bulls (supernormal images) from which the music of the myth and this ritual of destiny derived. It is not known by what means the kings were killed (or the priests who may have been serving by this time as their substitutes, about 2500 b.c.; but the manner of Puabi’s death is perfectly clear. “On the remains of a wooden bier lay the body of the queen, a gold cup near her had.” [Note 20] Her court was interred above his, but her own tomb had been sunk to the level of A-bar-gi’s and placed beside it. The myth being enacted in this mad rite was that of the ever-dying and resurrected god, “The Faithful Son of the Abyss,” or “The Son of the abyss who Rises,” Damuzi-absu, or Tammuz (Adonis). The queen of heaven, the daughter of God, goddess of the morning and evening star, the hierodule or slave-girl dancer of the gods — who, as the morning star, is ever-virgin, but, as evening star, is “the divine harlot,” and whose names in a later age were to be Ishtar, Aphrodite, and Venus — “from the ‘great above’ set her mind toward the ‘great below,’ abandoned heaven, abandoned earth, and to the nether world descended,” to release her brother and spouse from the land of no return.

By chance a fragment of her legend from the period of the tombs of Ur survives; and we have, also, just such a hymn as the tongues of the women of the gold and silver ribbons sang to the harps of the moon-bull that were found still in the grasp of the girl-harpists’ skeleton arms:

Mayest thou go, thou shalt cause him to rejoice,

O valorous one, star of Heaven, go to greet him.

To cause Damu to repose, mayest thou go,

Thou shalt cause him to rejoice.

To the shepherd Ur-Nammu mayest thou go,

Thou shalt cause him to rejoice.

To the man Dungi mayest thou go,

Thou shalt cause him to rejoice.

To the shepherd Bur-Sin mayest thou go,

Thou shalt cause him to rejoice.

To the man Gimil-Sin mayest thou go,

Thou shalt cause him to rejoice.

To the shepherd Ibi-Sin mayest thou go,

Thou shalt cause him to rejoice. [Note 21]

The five last titles are the names, in order, of the last kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur (about 2150-2050 b.c.) * and express will the fundamental concept of this whole archaic world, which was that the reality, the true being, of the king — as of any individual — is not in his character as individual but as archetype. He is the good shepherd, the protector of cows; and the people are his flock, his herd. Or he is the one who walks in the garden, the gardener; the one who gives life to the fields, the farmer of the gods. Again, he is the builder of the city, the culture-bringer, the teacher of the arts. and he is the lord of the celestial pastures, the moon, the sun. The five kings — Ur-Nammu, Dungi, Bur-Sin, Gimil-Sin, and Ibn-Sin — are the same, namely, Damu, the ever-living, ever-dying god; just as the Queen is Inanna, the naked goddess, whom we have known since the beginning of time.

From the “great above” she set her mind toward the “great below,”

The goddess, from the “great above” she set her mind toward the “great below,”

Inanna, from the “great above” she set her mind

toward the “great below.”

My lady abandoned heaven, abandoned earth,

To the nether world she descended,

Inanna abandoned heaven, abandoned earth,

To the nether world she descended,

Abandoned lordship, abandoned ladyship,

To the nether world she

descended.

The seven divine decrees she fastened at her side,

The shugurra, the crown of the plain, she put upon her head,

Radiance she placed upon her countenance,

The rod of lapis lazuli she gripped

in her hand,

Small lapis lazuli stones she tied about her neck,

sparkling stones she fastened to her breast,

A gold ring she gripped in her hand,

A breastplate she bound about her

breast.

All the garments of ladyship she arranged about her body,

Ointment she put upon her face.

Inanna walked toward the nether world. [Note 22]

Thus our precious fragment begins. the goddess is walking to the nether world, which is ruled by the dark side of her own self, her sister-goddess Ereshkigal. And she comes to the first gate.

When Inanna had arrived at the lapis lazuli palace of the nether world,

At the door of the nether world she acted evilly,

In the palace of the nether world she spoke evilly:

“Open the house, gatekeeper, open the house,

Open the house, Neti, open the house, all alone I

would enter.”

Neti, the chief gatekeeper of the nether world, answers the pure Inanna:

“Who, pray, art thou?”

“I am the queen of haven, the place where the sun

rises.”

“If thou art the queen of heaven, the place where the sun rises,

Why, pray, hast thou come to the land of no return?

How has thy heart led thee to the road whose

traveler does not return?”

The pure Inanna answers him:

“Ereshkigal, my elder sister,

The lord Gugalanna, her husband, has been killed:

I have come to attend the funeral.”

The chief gatekeeper of the nether world, Neti, answers the pure Inanna:

“Stay, Inanna, let me speak to my

queen.”

He goes, and returns. The chief gatekeeper of the nether world, Neti, speaks to the pure Inanna:

“Come, Inanna, enter.”

And the following dialogue then comes to pass.

Upon her entering the first gate,

The shugurra, the “crown of the plain” of her head, was removed.

“What, pray, is this?”

“Extraordinarily, O Inanna, have the decrees of the nether world been perfected,

O Inanna, do not question the rites of the nether

world.”

Upon her entering the second gate,

The rod of lapis lazuli was removed.

“What, pray, is this?”

“Extraordinarily, O Inanna, have the decrees of

the nether world been perfected.

Upon her entering the third gate,

The small lapis stones at her neck were removed.

“What, pray, is this?”

“Extraordinarily, O Inanna, have the decrees of the nether world been perfected,

O Inanna, do not question the rites of the nether

world.”

Upon her entering the fourth gate,

The sparkling stones of her breast were removed.

“What, pray, is this?”

“Extraordinarily, O Inanna, have the decrees of the nether world been perfected,

O Inanna, do not question the rites of the nether

world.”

Upon her entering the fifth gate,

The gold ring of her hand was removed.

“What, pray, is this?”

“Extraordinarily, O Inanna, have the decrees of the nether world been perfected,

O Inanna, do not question the rites of the nether

world.”

Upon her entering the seventh gate,

All the garments of her body were removed.

“What, pray, is this?”

“Extraordinarily, O Inanna, have the decrees of the nether world been perfected,

O Inanna, do not question the rites of the nether

world.”

Thus, naked, the goddess came before her sister and the seven judges of the nether world, Ereshkigal and the Anunnaki.

The pure Ereshkigal seated herself upon her throne,

The Anunnaki, the seven judges, pronounced judgement before her,

They fastened their eyes upon her, the eyes of death,

At their word, the word that tortures the spirit,

The sick woman was turned into a corpse,

And the corpse was hung from a stake. [Note 23]

But death, as we are taught in all the mythological traditions of the world, is not the end. The lesson of the moon-god, three days dark, is still to be told. Inanna’s corpse remained on the stake.

After three days and three nights had passed,

Her messenger Ninshubur,

Her messenger of favorable winds,

Her carrier of supporting words,

Filled the heaven with complaints for her,

Cried for her in the assembly shrine,

Rushed about for her in the house of the gods,

Like a pauper in a single garment he dressed for her,

To the Ekur, the house of Enlil, all alone he directed his step.

Ninshubur, known too as Papsukkal, “chief messenger of the gods,” and Ilabrat, “the god of wings,” was told by the goddess before her departure that if she did not return he should “Weep before Enlil (the air-god), weep before Nanna (the moon-god), and if these failed to respond, then weep before Enki, the lord of Wisdom (the serpent), who knows the food of life and the water of life. He,” she said, “will surely bring me to life.”

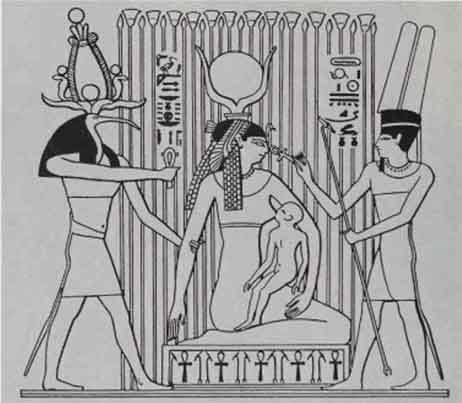

The clay figurines of Ninshubur, the messenger, found in foundation boxes beneath the doors of temples, show him without wings but bearing a staff or wand in his right hand. [Note 24] He is the prototype of Hermes (Mercury), the Olympian messenger of the gods and the guide of souls to the underworld, who also brings souls to be born again and so is regarded as the generator both of new lives and of the New Life. Hermes’ staff, it will be recalled, is the caduceus, with entwined serpents. But the meaning of these serpents is precisely the same as that of the ritual and myth we are now discussing: namely, it is a reference to the divine, world- renovating connubium of the monster serpent with the naked goddess in her serpent form.

Wishing to be certain of the reference of the sign of the caduceus, Dr. Henri Frankfort once sent an inquiry to the British Museum of Natural History. “The symbol in which you are interested may well represent two snakes pairing,” Mr. H.W. Parker, Assistant Keeper of Zoology, replied. “As a general rule the male seizes the female by the back of the neck and the two bodies are more or less intertwined….Vipers are said to have the bodies completely intertwined.” “This then,” comments Dr. Frankfort, “explains most satisfactorily why the caduceus should have become the symbol of our god, who is thus characterized as the personification of the generative force of Nature.” [Note 25] Hermes, the Greek carrier of the serpent staff — which is both beautiful and terrible and both bestows sleep and awakens — is the inventor of the lyre and of the art of making fire with the fire-sticks. He is, furthermore, the archetypal trickster god of the ancient world. We think of the bull-voiced lyres of the graves of Ur and of the Greek orgies where “bull-voices roared from somewhere out of the unseen” (Aeschylus, Fragment 57). We think of the young boy and girl of the fire-sticks in Africa, and their shocking rite. And we think, too, of Coyote-trickster, who turned himself into a girl and became pregnant. Hermes, too, is androgyne, as one should know from the sign of his staff.

When the messenger, Ninshubur, then Hermes’ prototype, had wept to no effect first before Enlil and then before the moon-god, Nanna, of the city of Ur, he turned to Enki, “Lord of the Waters of the Abyss,” who, when he had heard, cried out:

“What now has my daughter done! I am troubled,

What now has Inanna done! I am troubled,

What now has the queen of all the lands done! I am troubled,

What now has the hierodule of heaven done! I am troubled.”

He brought forth dirt and fashioned two sexless creatures, two angels. To the one he gave the food of life; to the other he gave the water of life. k and then he issued his commands.

“Upon the corpse hung from a stake direct the fear of the rays of fire,

Sixty times the food of life, sixty time the water of life, sprinkle upon it,

Verily Inanna will arise.”

Upon the corpse hung from a stake they directed the fear of the rays of fire,

Sixty times the food of life, sixty times the water of life, they sprinkled upon it,

Verily, Inanna arose.

Inanna ascended from the nether world,

The Anunnaki fled,

And whoever of the nether world had descended peacefully to the nether world;

When Inanna ascended from the nether world,

Verily the dead hastened ahead of her.

Inanna ascends from the nether world,

the small demons like reeds,

The large demons like tablet styluses,

Walk at her side…. [Note 26]

The conclusion of the piece is missing. But the import of the image is clear enough. It is a theme that has been given many turns in the course of the centuries since. One thinks, for example, of Mary Magdalene at the tomb, weeping outside the tomb; and as she wept she stooped to look within. But she saw two angels sitting in white where the body of Jesus had been, one at the head and one at the feet, and they said to her, “Woman, why are you weeping?” She answered, “Because they have taken away my Lord, and I do not know where they have laid him.” Saying which, she turned around and saw Jesus standing, but did not know that it was Jesus. He said to her: “Woman, why are you weeping? Whom do you seek?” And supposing him to be the gardener, she said, “Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have laid him, and I will take him away.” He said to her, “Mary!” She turned, and she said to him in Hebrew, “Teacher!” Jesus said to her, “Do not hold me; for I have not yet ascended to the Father; but go to my brethren and say to them, I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.” Then Mary Magdalene went and said to the disciples, “I have seen the Lord.” [Note 27]

III. The Great Diffusion

Huizinga, in his highly suggestive study of the play element in culture, Homo Ludens, points out that the Dutch and German words for “duty,” Plicht and Pflicht, are related etymologically to our English “play,” the words being derived from a common root. [Note 28] English “pledge,” too, is of this context, as well as the verb “plight,” meaning “to put under a pledge, to engage” (as in “to plight troth,” “a plighted bride”). We may recall here Huizinga’s reference to the Japanese “play language,” or “polite language” (asobase- kotoba), where it is not said that “you arrive in Tokyo,” but that “you play arrival”; not that “I hear you father is dead,” but that “I hear your father has played dying.”[Note 29] “The play-concept as such is of a higher order than seriousness,” Huizinga declares. “For seriousness seeks to excluded play, whereas play can very well include seriousness.” [Note 30]

The royal tombs of Ur illustrate the capacity and spirit of the world’s first aristocracy for play: pledging in play and then playing out the pledge. And it was in their utterly wonderful nerve for this particular game that the world was lifted from savagery to civilization. In such a performance the question of belief is of secondary moment and effect. The principle is that of the masque, the dance, the pageant, the motion pattern through the form of which a new power for life is evoked. An image is conceived, a supernormal image, surpassing in scope the requirements of food, clothing, shelter, sex, and a pleasant hobby for one’s leisure time. Nerve is required to move into such a game and to play out the fraction of one’s part in the picture. But then, behold! A transformation of life, an increment such as before had not been even imagined, and therewith a new horizon, both for man and for his gods. It was in the marvelous talent of the Sumerians for their function of an aristocracy of spirit. And it was continued as such in many parts of the world up to a very recent date.

Now, as Sir Leonard Woolley has already shown, the effigies of servants at their tasks in certain Egyptian tombs indicate that at one time the courts of the Nile too went with their kings into the underworld. Likewise, in the royal tombs of ancient China ceramic effigies have been found. In fact, in China the practice of human sacrifice at royal entombments persisted until well into the twelfth century a.d.; and in the neighboring island empire of Japan an impressive instance of the custom of voluntary “dead following” (jinchū, “loyalty”) came to the notice of the world as late as 1912, when the general Count Nogi, the hero of Port Arthur, put himself to death at the precise hour of the burial of his shōgun, Meijitenno, and the Countess Nogi then killed herself to accompany her spouse.

It is clear from the evidence that the ritual of “dead following” was a generally honored social and religious practice, not only in the cities of the Near East, where the epochal transition was fade from savagery to civilization, but also wherever the earliest carriers of the new game of destiny settled in their astonishingly broad and rapid conquest of new fields. The diffusion of their influence can be readily traced in the four directions — or rather, to the points between — somewhat as follows.

The Southwestward Diffusion