Chapter 2

The Imprints of Experience

I. Suffering and Rapture

James Joyce, in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, supplies an excellent structuring principle for a cross- cultural study of mythology when he defines the material of tragedy as “whatsoever is grave and constant in human sufferings”; [Note 1] for it is from the “grave and constant” that the imprints common to the mythologies of the world must be derived. And of such imprints, suffering itself — the raw material of tragedy — is surely the most general, since it is, in a preliminary sense at least, the sum and effect of all.

Moreover, tragedy — the Greek tragedy — was a poetic inflection of mythology, the tragic catharsis of emotion through pity and terror of which Aristotle wrote being precisely the counterpart, psychologically, of the purgation of spirit [Greek word] effected by a rite. Like the rite, tragedy transmutes suffering into rapture by altering the focus of the mind. The tragic art is a correlate of the discipline termed, in the language of religion, “spiritual cleansing,” or “the stripping of the self.” Released from attachment to one’s mortal part through a contemplation of the grave and constant in human sufferings — “correcting,” to use Plato’s felicitous phrase, “those circuits of the head that were deranged at birth, by learning to know the harmonies of the world” [Note 2] — one is united, simultaneously, in tragic pity with “the human sufferer” and in tragic terror with “the secret cause,” Plato’s “likeness of that which intelligence discerns.” Whereupon, one day, with a cry of joy, leaving both humanity and intelligence behind, the soul may leap to what it then suddenly recognizes beyond the mask. Finis tragoediae: incipit comoedia. The mode of the tragedy dissolves and the myth begins.

“O Lord, how marvelous is Thy face,” wrote Nicholas of Cusa,

The face, which a young man, if he strove to imagine it would conceive as a youth’s; a full-grown man, as manly; an aged man as an aged man’s! Who could imagine this sole pattern, most true and most adequate, of all faces — of all even as of each — this pattern so very perfectly of each as if it were of none other? He would have need to go beyond all forms of faces that may be formed, and all figures. And how could he imagine a face when he must go beyond all faces, and all likenesses and figures of all faces and all concepts which can be formed of a face, and all color, adornment and beauty of all faces? Wherefore he that goeth forward to behold Thy face, so long as he formeth any concept thereof, is far from Thy face. For all concept of a face falleth short, Lord, of Thy face, and all beauty which can be conceived is less than the beauty of Thy face; every face hath beauty yet none is beauty’s self, but Thy face, Lord, hath beauty and this having is being. ‘Tis therefore Absolute Beauty itself, which is the form that giveth being to every beautiful form. O face exceedingly comely, whose beauty all things to whom it is granted to behold it, suffice not to admire! In all faces is seen the Face of faces, veiled, and in a riddle; howbeit unveiled it is not seen, until above all faces a man enter into a certain secret and mystic silence where there is no knowledge or concept of a face. This mist, cloud, darkness, or ignorance into which he that seeketh Thy face entereth when he goeth beyond all knowledge or concept is the state below which Thy face cannot be found except veiled; but that very darkness revealeth Thy face to be there, beyond all veils. [Note 3]

Here is the secret cause — known not in terror but in rapture. And its sole beholder is the perfectly purified spirit, gone beyond the normal bounds of human experience, thought, and speech. “There the eye goes not,” we read in the Indian Kena Upaniṣad, “speech goes not, nor the mind.” [Note 4] And yet the impact has been experienced by a great many on this earth. It has been rendered (though seldom as wonderfully as in this inspired utterance of Cusanus )in many mythologies and many paeans of the mystics, in many times and many lands. Without question, it is an available experience, and should even, perhaps, be counted paramount among the “grave and constant” in human suffering and joy. Furthermore , the images rendering it must be classified in our science as of one order, no matter how alien they may be to our local forms of religious symbolization.

The Fifth Danish Thule Expedition (1921-1924) across arctic North America, from Greenland to Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, was conducted by the seasoned scholar and explorer Knud Rasmussen, who, in the course of this extraordinary journey, met and won the confidence of a number of Eskimo shamans: first, a generous-hearted, warmly hospitable, sturdy old man named Aua at Hudson Bay; next, in the harsh Baker Lake area, among the so-called Caribou Eskimo (who are as primitive as any people on earth), a ruthless, highly intelligent, strongly independent savage named Igjugarjuk, who, when as a youth he had wished to take to wife a girl whose family objected, went with his brother to lie in wait not far from the entrance to the young woman’s hut and from there shot down her father, mother, brothers, and sisters — seven or eight in all — until only the girl that he wanted remained; and finally, at Nome, an old scalawag named Najagneq, who had just been released from a year in jail for having killed seven or eight members of his community. In his distant village, Najagneq had made a fortress of his house and from there, alone, had waged war with the whole of his tribe — and against the whites too — until he had been taken by stratagem by the captain of a ship and brought to Nome. He was held in jail there until ten witnesses of his killings could be fetched from his settlement; but when these were confronted with him they dropped their charges, much as they would have liked to see him done away with. His small piercing eyes roamed about wildly, and his jaw hung in a bandage that was much too slack, a man who had tried to kill him having injured his face. And when the ten men who would have accused him met his look in the witness box, they lowered their eyes in shame.

It is worth considering for a moment the character of these rugged shamans, lest we suppose that the highest religious realizations are vouchsafed only to the saintly.

Dr. H. Ostermann, in his report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, wrote:

Najagneq’s powers of imagination had been stimulated in the big town of Nome. Although knowing of nothing except earth huts, sledges ad kayaks, he was not at all impressed by the large houses, the steamers and the motor-cars, but he had been fascinated by the sight of a white horse hauling a big lorry. So he now told his astonished fellow villagers that the white men in Nome had killed him ten times that winter, but that he had had ten white horses as helping spirits, and he had sacrificed them one by one and thus saved his life.

This man of “ten-horse-power” had authority in his speech, and he completely swayed those to whom he spoke. He had conceived a curious feeling of mild goodness for Dr. Rasmussen, and when they were alone together he was not afraid to admit that he had pulled the legs of his countrymen somewhat. He was no humbug, but a solitary man accustomed to hold his own against many and therefore had to have his little tricks. But whenever his old visions and his ancestral beliefs were mentioned, his replies, which were brief and to the point, bore the impress of imperturbable gravity. When Dr. Rasmussen asked him if he believed in any of all the powers he spoke of, he answered: “Yes, a power that we call Sila, one that cannot be explained in so many words. A strong spirit, the upholder of the universe, of the weather, in fact all life on earth — so mighty that his speech to man comes not through ordinary words, but through storms, snowfall, rain showers, the tempests of the sea, through all the forces that man fears, or through sunshine, calm seas or small, innocent, playing children who understand nothing. When times are good, Sila has nothing to say to mankind. He has disappeared into his infinite nothingness and remains away as long as people do not abuse life but have respect for their daily food. No one has ever seen Sila. His place of sojourn is so mysterious that he is with us and infinitely far away at the same time.”

And Dr. Rasmussen adds [Dr. Ostermann is quoting from the notes found in Rasmussen’s posthuma]: “Najagneq’s words sound like an echo of the wisdom we admired in the old shamans we encountered everywhere on our travels — in harsh King William Land or in Aua’s festive snow hut at Hudson Bay, or in the primitive Eskimo Igjugarjuk, whose pithy maxim was:

“‘The only true wisdom lives far from mankind, out in the great loneliness, and it can be reached only through suffering. Privation and suffering alone can open the mind of a man to all that is hidden to others.’” [Note 5]

We shall return in a later chapter to Igjugarjuk and his story of the sufferings through which he learned true wisdom. The present point is that from the great Cusanus to the great Igjugarjuk we have a considerable span of human character and experience, as well as of cultural inheritance; yet, unless I am deceived, the ultimate reference of their mutually independent statements is the same. Nor is this the last that we shall learn of the hidden wisdom achieved through suffering, “in the great loneliness,” which is “beyond all forms of faces that may be formed, and all figures,” or as Najagneq put it, “cannot be explained in so many words.”

The “grave and constant” in human suffering, then, leads — or may lead — to an experience that is regarded by those who have known it as the apogee of their lives, and which is yet ineffable. And this experience, or at least an approach to it, is the ultimate aim of all religion, the ultimate reference of all myth and rite. Moreover, those by whom the mythological traditions of the world have been developed and maintained have been the shamans, sages, prophets, and priests, many of whom have had an actual experience of this ineffable mystery and all of whom have revered it. One of the ironies of our subject is that much of the research and collecting among primitive tribes has been conducted either by scientists whose minds are sterilized to this experience and for whom the word “mystic” is a term of abuse, or else by missionaries for whom the only valid approach to it is in their own tradition of spiritual metaphor. Yet occasionally a scholar of Rasmussen’s stature appears and the truth is out.

The first point to be noticed is that a primitive wizard is perfectly capable not only of uttering as profound a statement concerning the relationship of man to the mystery of his being as any that will be found in the annals of the higher religions, but also of wantonly producing parodies of his own mythology to intimidate and impress his simpler fellows. The fact that valid mythological motifs (for example, death and resurrection) have been used in this way for deception does not mean that in proper context they are still, necessarily, the “opiate of the people.” Yet they certainly may become just that; for since the ultimate reference of religion is ineffable, many of those who live most sincerely by its mythology are the most deceived — this deception itself being part of the suffering and darkness through which the mind must pass before the Face-that-is-no- face becomes known.

There is a word in Sanskrit, Upadhi, which means “deceit, deception, disguise,” but also, “limitation, idiosyncrasy, or attribute.” The ultimate truth, being without attributes, cannot be contemplated by the mind. As Igjugarjuk says, it “lives far from mankind, out in the great loneliness.” Therefore, in rites and meditations designed to ready the mind for an experience of the beauty that is Absolute Beauty, “attributes” (upadhis) are assigned to it; for example, in the meditation of Cusanus, the property of being a face — and of being beautiful.

Gerhart Hauptmann has somewhere said that poetry is the art of causing the Word to resound behind words (Dichten heißt, hinter Worten das Urwort erklingen lassen). [Note 6] In the same sense, mythology is a rendition of forms through which the formless Form of forms can be known. An inferior object is presented as the representation, or habitation, of a superior. The love or attachment felt for the inferior is a function actually of one’s potential establishment in the superior; yet it must be sacrificed (therein the suffering!) if the mind is to pass on to its proper end.

The science of comparative mythology is, then, a comparative study of upadhis: the deceptive attributes of being, through which the human mind, in the various eras and areas of its domain, has been united with the secret cause in tragic terror, and with the human sufferer (the self being stripped away) in tragic pity. And these upadhis are of two orders: those inevitably deriving from the primary conditions of all human experience whatsoever (la condition humaine), and those particular to the various areas and eras of human civilization (die Völkergedanken). Of the first we treat in the present chapter; of the others, in the remaining sections of the work.

But all, certainly, will not be of suffering, the tragic upadhi (or deception) of suffering; for the paramount theme of mythology is not the agony of quest but the rapture of a revelation, not death but the resurrection: Hallelujah!

“I am she,” declared the great goddess of the universe, Queen Isis, when she appeared to Lucius Apuleius, her devotee, at the conclusion of the ordeal described allegorically in his novel, The Golden Ass:

I am she that is the natural mother of all things, mistress and governess of all the elements, the initial progeny of worlds, chief of the powers divine, queen of all that are in hell, the principal of them that dwell in heaven, manifested alone and under one form of all the gods and goddesses. At my will the planets of the sky, the wholesome winds of the seas, and the lamentable silences of hell are disposed; my name, my divinity is adored throughout the world, in divers manners, in variable customs, and by many names.

For the Phrygians that are the first of all men call me the Mother of the gods of Pessinus; the Athenians, which are sprung from their own soil, Cecropian Minerva; the Cyprians, which are girt about by the sea, Paphian Venus; the Cretans, which bear arrows, Dictynian Diana; the Sicilians, which speak three tongues, infernal Proserpine; the Eleusians their ancient goddess Ceres; some Juno, others Bellona, others Hecate, others Ramnusie, and principally both sort of the Ethiopians, which dwell in the Orient and are enlightened by the morning rays of the sun; and the Egyptians, which are excellent in all kind of ancient doctrine, and by their proper ceremonies accustomed to worship me, do call me by my true name, Queen Isis.

Behold I am come to take pity of thy fortune and tribulation; behold I am present to favor and aid thee; leave off thy weeping and lamentation, put away all thy sorrow, for behold the healthful day which is ordained by my providence. [Note 7]

Suffering itself is a deception (upadhi); for its core is rapture, which is the attribute (upadhi) of illumination.

The imprint of the rapture enclosed in suffering, then, is the foremost “grave and constant” of our science. Compassed in the life wisdom of perhaps but a minority of the human race, it has nevertheless been the matrix and final term of all the mythologies of the world, yielding its radiance to the whole festival of those lesser upadhis — or imprints — to which we now must turn.

II. The Structuring Force of Life on Earth

Certainly one force that can never have been absent from human experience, as Adolf Portmann has pointed out in a suggestive paper on “The Earth as the Home of Life,” [Note 8] is gravity, which no only works continuously on every aspect of human affairs, but has fundamentally conditioned the form of the body and all its organs. The diurnal alternation of light and dark is another ineluctable factor of experience, to which, indeed, considerable dramatic value accrues as a result of the fact that at night the world sleeps, dangers lurk, and the mind plunges into a realm of dream experience, which differs in its logic from the world of light. In dream, objects shine of themselves, without illumination from without, and moreover, are of a subtle substance that is capable of magical and rapid transformation, appalling effects, and non-mechanical locomotion. The can be no doubt but that the world of myth has been saturated by dream, or that men were dreaming even when they were little more than apes. And, as Géza Róheim has observed, “there cannot be several ‘culturally determined’ ways of dreaming, just as there are no two ways of sleeping.” [Note 9]

Dawn, and awakening from this world of dream, must always have been associated with the sun and sunrise. The night fears and night charms are dispelled by light, which has always been experienced as coming from above and as furnishing guidance and orientation. Darkness, then, and weight, the pull of gravity and the dark interior of the earth, of the jungle, or of the deep sea, as well as certain extremely poignant fears and delights, must for millenniums have constituted a firm syndrome of human experience, in contrast to the luminous flight of the world-awakening solar sphere into and through immeasurable heights. Hence a polarity of light and dark, above and below, guidance and loss of bearings, confidence and fears (a polarity that we all know from our own tradition of thought and feeling and can find matched in many parts of the world) must be reckoned as inevitable in the way of a structuring principle of human thought. It may or may not be fixed within us as an “isomorph”; but, in any case, it is certainly a general and very deeply known experience. The moon, furthermore, and the spectacle of the night sky, the stars and the Milky Way, have constituted, certainly from the beginning, a source of wonder and profound impression. But there is actually a physical influence of the moon upon the earth and its creatures, its tides and our own interior tides, which has long been consciously recognized as well as subliminally experienced. The coincidence of the menstrual cycle with that of the moon is a physical actuality structuring human life and a curiosity that has been observed with wonder. It is in fact likely that the fundamental notion of a life-structuring relationship between the heavenly world and that of man was derived from the realization, both in experience and in thought, of the force of the lunar cycle. The mystery, also, of the death and resurrection of the moon, as well as of its influence on dogs, wolves and foxes, jackals and coyotes, which try to sing to it: this immortal silver dish of wonder, cruising among the beautiful stars and racing through the clouds, turning waking life itself into a sort of dream, has been a force and presence even more powerful in the shaping of mythology than the sun, by which its light and its world of stars, night sounds, erotic moods, and the magic of dream, are daily quenched.

The contrast in physical form and spheres of competence of the male and female surely is another universal of human experience; and we must reckon also, in this context, with the “instinct crossing” between the two, which makes possible — or rather, inevitable, and sometimes even against better judgment — the awakening of the two bodies in synchronization to that curious mutual engagement which the Freudians like to call a “re-enactment of the primal scene,” and which many have found to be the one consummation of appetite most difficult to resist. In a number of meticulous studies of animal behavior it has been shown that a trimly meshed sequence of sign stimuli, flashed from the male organism to the female and from the female to the male, can be identified as releasers of the sometimes exceedingly complicated performances that must be undertaken in perfect synchronization before the species can be reproduced; and I do not know anyone outside of the most carefully schooled scientific circles who would suppose for a moment that a comparable criss-cross of isomorphs might not safely be assumed to exist on the human level as well. But since nothing is to be assumed recklessly on the basis of merely personal experience, and no one has yet been able to raise two young human beings in absolute isolation from social conditioning and introduce them to each other when the moon is full, we shall not presume to say how much of what everyone knows about this matter is due to imprint, or how much to inherited image. Let us remark only that the perfumes of flowers, the beautification of the body, night, secret meetings, music, token exchanges, anguish, remorse, rivalry, jealousy, murder, and the whole opera, can be identified in human history as far as our eyes can see.

And we have the voluminous literature of the Freudian school to assure us that the covert as well as obvious analogies, puns, and inflections by which sex, the sex organs, and the sexual act are implicated in our thoughts are known to every tradition in the world, whether oral or literate. In mythology, of course, the image of birth from the womb is an extremely common figure for the origin of the universe, and the sexual intercourse that must have preceded it is represented in ritual action as well as in story. Furthermore, the mysterious (one might even say, magical) functioning of the female body in its menstrual cycle, in the ceasing of the cycle during the period of gestation, and in the agony of birth — and the appearance, then, of the new being; these, certainly, have made profound imprints on the mind. The fear of menstrual blood and isolation of women during their periods, the rites of birth, and all the lore of magic associated with human fecundity make it evident that we are here in the field of one of the major centers of interest of the human imagination. In the earliest ritual art the naked female form is extremely prominent, whereas the male is usually ornamented, or masked, as shaman or hunter in the performance of some act. The fear of woman and the mystery of her motherhood have been for the male no less impressive imprinting forces that the fears and mysteries of the world of nature itself. And there may be found in the mythologies and ritual traditions of our entire species innumerable instances of the unrelenting efforts of the male to relate himself effectively — in the way, so to say, of antagonistic cooperation — to these two alien yet intimately constraining forces: woman and the world.

Still another profoundly important structuring system of experiences that can be said, without question, to constitute a pattern of imprints on our own readiness for life is that of the normal stages of human growth and emotional susceptibility, from the moment of birth to that of death and the stench of decay. A great deal of excellent writing on this subject has been produced recently by the various authorities on child psychology and psychoanalysis, so that to review the whole matter in detail would be only to repeat what is already very well known. However, I am not aware of any work that has yet drawn attention in systematic series to the mythological motifs developed from the imprints of this sociologized biology of human growth.

As we have noted, it requires twenty years of the human organism to mature, and during the greater part of this development it is dependent, utterly, upon parental care. There follows a period of another twenty years or so of maturity, after which the signs of age begin to appear. But the human being is the only animal capable of knowing death as the end inevitable for itself, and the span of old age for this human organism, consciously facing death, is a period of years longer than the whole lifetime of any other primate. So we see three — at least three — distinct periods of growth and susceptibility to imprint as inevitable in a human biography: (1) childhood and youth, with its uncouth charm; (2) maturity, with its competence and authority; and (3) wise old age, nursing its own death and gazing back, either with love or with rancor, at the fading world.

It has been the chief function of much of the mythological lore and ritual practice of our species to carry the mind, feelings, and powers of action of the individual across the critical thresholds from the two decades of infancy to adulthood, and from old age to death; to supply the sign stimuli adequate to release the life energies of the one who is no longer what he was for his new task, the new phase, in a manner appropriate to the well-being of the group. And so we find, on the one hand, as a constant factor in these “rites of passage,” the inevitable, and therefore universal, requirements of the human individual at the particular junctures, and on the other hand, as a cultural variable, the historically conditioned requirements and beliefs of the local group. This gives that interesting quality of seeming to be ever the same, though ever changing, to the kaleidoscope of world mythology, which may charm our poets and artists but is a nightmare for the mind that seeks to classify. And yet, with a steady eye, even the phantasmagoria of a nightmare can be catalogued — to a degree.

The remaining sections of the present chapter develop, therefore, in the way of a tentative, preliminary sketch, the main lines and phases of what would appear to have been — up to the present moment, at least — the chief sources of imprint in the course of the archetypal biography of man.

III. The Imprints of Early Infancy

Certain imprints impressed upon the nervous system in the plastic period between birth and maturity are the source of many of the most widely known images of myth. Necessarily the same for all mankind, they have been variously organized in the differing traditions, but everywhere function as potent energy releasers and directors.

The first indelible imprints are those of the moment of birth itself. The congestion of blood and sense of suffocation experienced by the infant before its lungs commence to operate give rise to a brief seizure of terror, the physical effects of which (caught breath, circulatory congestion, dizziness, or even blackout) tend to recur, more or less strongly, whenever there is an abrupt moment of fright. So that the birth trauma, as an archetype of transformation, floods with considerable emotional effect the brief moment of loss of security and threat of death that accompanies any crisis of radical change. In the imagery of mythology and religion this birth (or more often rebirth) theme is extremely prominent; in fact, every threshold passage — not only this from the darkness of the womb to the light of the sun, but also those from childhood to adult life and from the light of the world to whatever mystery of darkness may lie beyond the portal of death — is comparable to a birth and has been ritually represented, practically everywhere, through an imagery of re-entry into the womb. This is one of those mythological universals that surely merit interpretation, rather from a psychological than from an ethnological point of view.

The water image in mythology is intimately associated with this motif, and the goddesses, mermaids, witches, and sirens that often appear as guardians or manifestations of water (wells, water courses, youth-renewing caldrons), Ladies of the Lake and other water nixies, may represent either its life-threatening or its life-furthering aspect.

The Late Classical story of Actaeon, for example, as rendered in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, [Note 10] tells of a hunter, a vigorous youth in the prime of his young manhood, who, when stalking deer with his dogs, chanced upon a stream that he followed to its source, where he broke upon the goddess Diana bathing, surrounded by a galaxy of naked nymphs. And the youth, not spiritually prepared for such a supernormal image, had only the normal look in his eye; whereupon the goddess, perceiving this, sent forth her power and transformed him into a stag, which his own dogs then immediately scented, pursued, and tore to bits.

On the simple level of a typical Freudian reading, this mythical episode represents the prurient anxiety of a small boy discovering Mother; but according to a more sophisticated, “sublimated” vein of reference, more appropriate to the post-Alexandrian atmosphere of Ovid’s elegant art, Diana was a manifestation of that goddess-mother of the world whom we have already met as Queen Isis, and who, as she herself has told us, was known to the cultures of the Mediterranean under many names. The case, surely, is that of an upadhi: an inferior object (mother image) serving as symbol of a superior (the mystery of life). Meditating, we may emphasize the superior, in which case we are performing what in India is termed sampad upāsāna, ” accomplished, or perfected, meditation” ; or we may emphasize the inferior, which is termed adhyāsa upāsāna, “superimposed, or false, meditation.” The first elevates to the supernormal; the second leaves one about as Actaeon: to be psychoanalyzed, finally, to bits and returned to the womb.

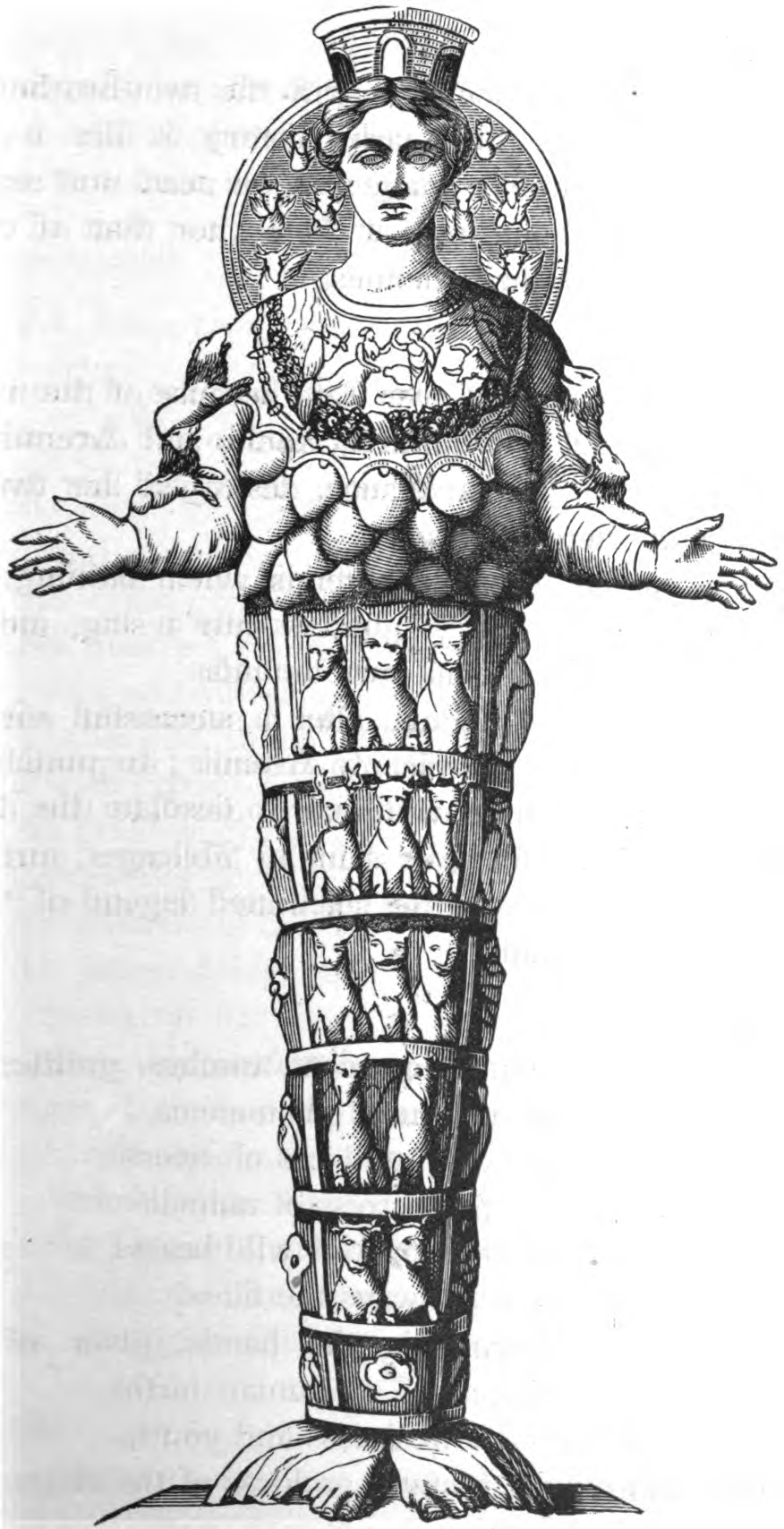

Figure 2. Artemis of Ephesus

At her greatest temple city in Asia Minor, at Ephesus (where, in a.d. 431, the Virgin Mary would be declared to have been truly “the Godbearer”), the great goddess, the mother of all things, was represented as Artemis (Diana) with a multitude of breasts. Innumerable figurines, furthermore, of naked goddesses (or rather, in the spirit of her own perfected teaching, we should say, of the Naked Goddess) have been found throughout the excavated ruins of the ancient world. As Heinrich Zimmer observed in his commentary on a Hindu version of her story:

If one inquires to know her ultimate origin, the oldest textual remains and images can carry us back only so far, and permit us to say: “Thus she appeared in those early times; so-and-so she may have been named; and in such-and-such a manner she seems to have been revered.” But with that we have come to the end of what can be said; with that we have come to the primitive problem of her comprehension and being. She is the primum mobile, the first beginning, the material matrix out of which all comes forth. To question beyond her into her antecedents and origin, is not to understand her, is indeed to misunderstand and underestimate, in fact to insult her. And anyone attempting such a thing well might suffer the calamity that befell that smart young adept who undertook to unveil the veiled image of the Goddess in the ancient Egyptian temple of Sais, and whose tongue was paralysed forever by the shock of what he saw. According to the Greek tradition the Goddess has declared of herself: [Greek terms], “no one has lifted my veil.” It is a question not exactly of the veil, but of the garment that covers her female nakedness — the veil is a later misinterpretation for the sake of decency. The meaning is: I am the Mother without a spouse, the Original Mother; all are my children, and therefore none has ever dared to approach me; the impudent one who should attempt it shames the Mother — and that is the reason for the curse. [Note 11]

In the tale of Actaeon we have this same religious theme rendered in a comparable image. “And though Diana would fain have had her arrow ready,” Ovid tells us, “what she had she took up, the water, and flung it into the young man’s face. And as she poured the avenging drops upon his hair, she spoke these words, foreboding his coming doom: ‘Now you are free to tell that you have seen me unrobed — if you can tell.’” [Note 12]

The water is the vehicle of the power of the goddess; but equally, it is she who personifies the mystery of the waters of birth and dissolution — whether of the individual or of the universe. For in the vein of myth the elemental mode of representation may alternate with that of personification. At the opening of the Book of Genesis is it not written, for example, that “the Spirit [or wind] of God was moving over the face of the waters”? Water and wind, matter and spirit, life and its generator: these pairs of opposites are fused in the experience of life; and their world-creating juncture may be represented elementally, as in this opening of the Bible, or on the other hand, as in the art of the Tantric Buddhism, in the image of a divine male and female in sexual embrace. The mystery of the origin of the “great universe” or macrocosm is read in terms of the procreation of the “little universe,” the microcosm; and the amniotic fluid is then precisely comparable to the water that in many mythologies, as well as in the pre-Socratic philosophy of the Greek sage Thales of Miletus (c. 640-546 b.c.), represents the elementary substance of all things.

This manner of homologizing the personal and the universal, which is a basic method of mythological discourse, has made it possible for Freudian psychoanalysts, whose training in the language of symbols has been derived from a study primarily of neurotics, to translate the whole cultural inheritance of mankind back into nursery rhymes. But the problem of the neurotic is, precisely, that instead of accomplishing the passage of the difficult threshold of puberty, dying as infant to be reborn as adult, he has remained with a significant fraction of his personality structure fixed in the condition of dependency. Rejecting emotionally the reorganization of his childhood imprints through the myths and rites of a maturely functioning community, he can read the picture language of his civilization only in terms of the infantile sources of its developed and manipulated figures; whereas in the mythology and rites these have been applied to a cultural and simultaneously metaphysical context of allusions. Freud theoretically devaluated such culturally and philosophically inspired repatternings, terming them mere “secondary elaborations” — which is perhaps appropriate when the case in question is the nightmare of some forty-year-old sub- adolescent, weeping on a couch. But in the reading of myth such a reductive method commits us to the monotony of identifying in every symbolic system only the infantile sources of its elements, neglecting as merely secondary the historical problem of their reorganization: pretty much as though an architect, viewing the structures of Rome, Istanbul, Mohenjo-Daro, and New York, were to content himself with the observation that all are of brick. In the present chapter we are examining bricks. Hereafter we may take bricks for granted and concern ourselves with their employment. For, as a Jungian friend of mine once epitomized the problem: “It is the predicament of the neurotic that he translates everything into the terms of infantile sexuality; but if the doctor does so too, then where do we get?”

The state of the child in the womb is one of bliss, actionless bliss, and this state may be compared to the beatitude visualized for paradise. In the womb, the child is unaware of the alternation of night and day, or of any of the images of temporality. It should not be surprising, therefore, if the metaphors used to represent eternity suggest, to those trained in the symbolism of the infantile unconscious, retreat to the womb.

The fear of the dark, which is so strong in children, has been said to be a function of their fear of returning to the womb: the fear that their recently achieved daylight consciousness and not yet secure individuality should be reabsorbed. In archaic art, the labyrinth — home of the child-consuming Minotaur — was represented in the figure of a spiral. The spiral also appears spontaneously in certain stages of meditation, as well as to people going to sleep under ether. It is a prominent device, furthermore, at the silent entrances and within the dark passages of the ancient Irish kingly burial mound of New Grange. These facts suggest that a constellation of images denoting the plunge an dissolution of consciousness in the darkness of non-being must have been employed intentionally, from an early date, to represent the analogy of threshold rites to the mystery of the entry of the child into the womb for birth. And this suggestion is reinforced by the further fact that the paleolithic caves of southern France and northern Spain, which are now dated by most authorities circa 35,000–11,000 b.c.*, were certainly sanctuaries not only of hunting magic but also of the male puberty rites. A terrific sense of claustrophobia, and simultaneously of release from every context of the world above, assails the mind impounded in those more than absolutely dark abysses, where darkness no longer is an absence of light but an experienced force. And when a light is flashed to reveal the beautifully painted bulls and mammoths, flocks of reindeer, trotting ponies, woolly rhinos, and dancing shamans of those caves, the images smite the mind as indelible imprints. It is obvious that the idea of death-and-rebirth, rebirth through ritual and with a fresh organization of profoundly impressed sign stimuli, is an extremely ancient one in the history of culture, and that everything was done, even in the period of the paleolithic caves, to inspire in the youngsters being symbolically killed a reactivation of their childhood fear of the dark. The psychological value of such a “shock treatment” for the shattering of a no longer wanted personality structure appears to have been methodically utilized in a time-tested pedagogical crisis of brainwashing and simultaneous reconditioning of the IRMs, for the conversion of babes into men, dependable hunters, and courageous defenders of the tribe.

The concept of the earth as both bearing and nourishing mother has been extremely prominent in the mythologies both of hunting societies and of planters. According to the imagery of the hunters, it is from her womb that the game animals derive, and one discovers their timeless archetypes in the underworld, or dancing ground, of the rites of initiation — those archetypes of which the flocks on earth are but temporal manifestations sent for the nourishment of man. Comparably, according to the planters, it is in the mother’s body that the grain is sown: the plowing of the earth is a begetting and the growth of the grain a birth. Furthermore, the idea of the earth as mother and of burial as a re-entry into the womb for rebirth appears to have recommended itself to at least some of the communities of mankind at an extremely early date. The earliest unmistakable evidences of ritual and therewith of mythological thought yet found have been the grave burials of Homo neanderthalensis, a remote predecessor of our own species, whose period is perhaps to be dated as early as >200,000–23,000 b.c.* [Note 13] Neanderthal skeletons have been found interred with supplies (suggesting the idea of another life), accompanied by animal sacrifice (wild ox, bison, and wild goat), with attention to an east-west axis (the path of the sun, which is reborn from the same earth in which the dead are placed), in flexed position (as though within the womb), or in a sleeping posture — in one case with a pillow of chips of flint. [Note 14] Sleep and death, awakening and resurrection, the grave as a return to the mother for rebirth; but whether Homo neanderthalensis thought the next awakening would be here again or in some world to come (or even both together) we do not know.

So much, then for the imagery of birth.

The next constellation of imprints to be noted is that associated with the bliss of the child at the mother’s breast; and here again we have a context of enduring force. The relationship of suckling to mother is one of symbiosis: though two, they constitute a unit. In fact, as far as the infant is concerned — who is still far from having conceived even the first notion of a dissociation between subject and object, inside and outside — affective aspect of its own experience and those external stimuli to which its feeling, needs, and satisfactions correspond are exactly one. Its world, as Jean Piaget has clearly shown in his study of The Child’s Conception of the World, is a “continuum of consciousness,” [Note 15] at once physical and psychic. Whatever impinges upon its unpracticed senses is uncritically identified with the attendant tonalities of its own interior, so that between the external and internal poles of its world there is no distinction. And this undefined, undefining experience of continuity is only emphasized by the readiness of the mother to respond to, or even to anticipate, its requirements. [Note 16] The whole tiny universe of this self- centered mite is ” a network of purposive movements, more or less mutually dependent,” [Note 17] and all tending toward the good of — itself.

But the mother cannot anticipate everything. There are moments, consequently, when the universe does not correspond exactly to experienced need. whereupon the imprints of that first terrifying shock of separation, the birth trauma, which afflicted the whole organism in its initial experience of the assault of life, are more or less forcefully reactivated. The mother is absent; the universe, absent; the bliss of the blessed infant imbibing forever the ambrosia of the madonna’s body is gone forever. Melanie Klein, who has devoted particular attention to this very early chapter of our universal biography, has suggested that at such moments an impulse to tear “good body content” from the mother is immediately and simultaneously identified by the child with the danger of its own bodily destruction. [Note 18] Hence, when the mother image begins to assume definition in the gradual dawn of the infantile consciousness, it is already associated not only with the sense of beatitude, but also with fantasies of danger, separation, and terrible destruction.

Figure 3. Devouring Kālī

We all know the fairy tale of the witch who lives in a candy house that would be nice to eat. Indeed, we have seen already what a scare she gave to a child who conjured her up in play. She is kind to children and invites them into her tasty house only because she wants to eat them. She is a cannibal. (And for some six hundred thousand years of human experience cannibals, it should be born in mind — and even cannibal mothers — were grim and gruesome, ever-present realities.) Cannibal ogresses appear in the folklore of peoples, high and low, throughout the world; and on the mythological level the archetype is even magnified into a universal symbol in such cannibal-mother goddesses as the Hindu Kālī , the “Black One,” who is a personification of “all-consumming Time”; or in the medieval European figure of the consumer of the wicked dead, the female mouth and belly of Hel.

In a myth of the Melanesian island of Malekula in the New Hebrides, which describes the dangers of the way to the Land of the Dead, it is told that when the soul has been carried on a wind across the waters of death and is approaching the entrance of the underworld, it perceives a female guardian sitting before the entrance, drawing a labyrinth design across the path, of which she erases half as the soul approaches. The voyager must restore the design perfectly if he is to pass through it to the Land of the Dead. Those who fail, the threshold guardian eats. One may understand how very important it must have been, then, to learn the secret of the labyrinth before death; and why the teaching of this secret of immortality is the chief concern of the religious ceremonials of Malekula.

According to a number of authorities cited by W.F. Jackson Knight in a highly interesting and suggestive article on “Maze Symbolism and the Trojan Game,” the labyrinth, maze, and spiral were associated in ancient Crete and Babylon with the internal organs of the human anatomy as well as with the underworld, the one being the microcosm of the other. “The object of the tomb-builder would have been to make the tomb as much like the body of the mother as he was able,” he writes, since to enter the next world, “the spirit would have to be re-born,” [Note 19] “The maze form — which is an elaborated spiral — gives a long and indirect path from the outside of an area to the inside, at a point called the nucleus, generally near the center. Its principle seems to be the provision of a difficult but possible access to some important point. Two ideas are involved: the idea of defence and exclusion, and the idea of the penetration, on correct terms, of this defence.” [Note 20] “The maze symbolism,” he states further, “seems somehow to be associated with maidenhood….The overcoming of difficulties by a hero frequently precedes union with some hidden princess.” [Note 21]

In the celebrated story of Theseus, the labyrinth, and the princess Ariadne, the Cretan labyrinth was difficult to enter and as difficult to leave, but Ariadne’s thread supplied the clue. And when the legendary founder of Rome, the hero Aeneas, arrived, in the course of his journey from Troy, at the cavern-entrance of the underworld, he found engraved there, upon the rocky face, a figure of the Cretan labyrinth. And when he and his company had made sacrifice of abundant beeves and lambs to the ultimate deities of that abyss, “Lo! about the first rays of sunrise the ground moaned underfoot, and the woodland ridges began to stir, and dogs seemed to howl through the dusk as the terrible guardian, the Sibyl, arrived. ‘Away! Depart, you unsanctified!” she cried. ‘Retire from the grove! But thou, Aeneas, come, unsheath thy steel; now is need of courage, now of strong resolve!’ Whereupon she plunged in ecstasy into the cavern opening, and he, unflinching, depth pace with his advancing guide.” [Note 22]

We have already noted that in the early Irish kingly burial mound of New Grange (which is to be dated somewhere in the second millennium b.c.) labyrinthine spirals are prominent, not only within the narrow passages to the “nucleus” but also, and most conspicuously, on the great threshold-stones at the entrances, where they guard the four gates, one facing in each of the four directions. In ancient Egypt the structure known as the Labyrinth (mentioned by Herodotus and Strabo, and excavated by Flinders Petrie in 1888) was a vast complex of buildings beside an artificial lake, with the tombs of kings and sacred crocodiles in the basement. The relationship (if any) of such megalithic structures and the rituals of their use in Egypt, Crete, and Ireland to the mortuary customs of remote Melanesia, which are also associated both with megaliths and with the symbolism of the spiral and the labyrinth, as well as with animal sacrifice (the sacrificial animal there, however, being the pig), we shall consider when we come to the problem of the origins and diffusion of the mythological motifs of the neolithic and equatorial culture spheres. For the present, it will suffice to remark that in Malekula, when the voyager to the Land of the Dead has proved himself qualified to enter the cave by completing the labyrinth-design of the dangerous guardian, he discovers therein a great water, the Water of Life, on the shore of which grows a tree, which he climbs, and from which he dives into the waters of the subterranean sea. [Note 23]

The Hindu mother-goddess Kālī is represented with her long tongue lolling to lick up the lives and blood of her children. She is the very pattern of the sow that eats her farrow, the cannibal ogress: life itself, the universe, which sends forth beings only to consume them. And yet she is simultaneously the goddess Annapurna (anna meaning “food,” and pūrnā, “abundance”), India’s counterpart of Egyptian Isis with the sun-child Horus at her breast, or of Babylonian Ishtar, nursing the moon-god reborn, the archaic prefigurements in Mediterranean mythology and art of the Madonna of the Middle Ages.

And so, in mythology and rite, as well as in the psychology of the infant, we find the imagery of the mother associated almost equally with beatitude and danger, birth and death, the inexhaustible nourishing breast and the tearing claws of the ogress. The heavenly realm, where the paradisial meal is served forever, and Olympus, the mountain of the gods, where ambrosia flows — these, certainly, are but versions fit for adult saints and heroes of the bliss of the well-nursed child. And the primary imprint of which the fury and fright of the disemboweling maw of hell is the adult amplification is no less certainly the child’s own fantasies of its raging body — its whole universe — torn apart.

A third system of imprints that can be assumed to be universal in the development of the mentality of the infant is that deriving from its fascination with its own excrement, which becomes emphatic at the age of about two and a half. In many societies the infant experiences the first impact of severe discipline in the matter of when, where, and how it may permit itself to respond to nature; the worst of it being that for the child, at this period of its life, defecation is experienced as a creative act and its own excrement as a thing of value, suitable for presentation as a gift. In societies in which this pattern of interest and action is regarded as unattractive, a socially determined reorganization of response is imposed sharply and absolutely, the spontaneous interest and evaluations of the earlier period of the child’s thought being then strictly repressed. But they cannot be erased. They remain as subordinated, written-over imprints: forbidden images, apt on occasion, or under one disguise or another, to reassert their force.

Throughout the higher mythologies there is abundant evidence of dualistic systems of imagery deriving from this circumstance. They are to be recognized in the prevalence of an association of filth with sin and cleanliness with virtue. Hell is a foul pit and heaven a place of absolute purity, whether in the Buddhist, Zoroastrian, Hindu, Moslem or Christian organization of the afterworld. Furthermore, there has been a suggestion from Dr. Freud to the effect that the infantile urge to manipulate filth and assign it value survives in our adult interest in the arts — painting, smearing of all kinds, sculpture, and architecture — as well as in the urge to collect precious stones, gold, or money, and in the pleasures derived from the giving and receiving of gifts. The aim of the sixteenth-and seventeenth-century alchemists to sublimate “base matter” (filth and corruption) into gold (which is pure and therefore incorruptible) would represent perfectly, according to this view, an urge to carry the energies locked in the first system of interests into the sphere of the superimposed second, so that, instead of suppression and therewith division, there should be effected a sublimation, or vital fusion, of the two socially opposed systems of the psyche, or, to use the phrase of the poet Blake, a Marriage of Heaven and Hell. And the fact that it was precisely at the time of the collapse (for many) of the authority of the medieval dualism of God and devil that the greatest flowering not only of alchemy but also of the Occidental arts took place may tend to confirm this psychoanalytical reading of the urge that brought them forth. The value of gold, of the marble and clay of the sculptor, and of the materials of the painter may be supposed, furthermore, to have been the greater inasmuch as all were derived from the bowels of the earth — which, according to the system of the saints, had long received an emphatically negative interpretation as the seat of hell.

And it may be noted further, in this connection, that in practically every primitive society ever studied the smearing of paint and clay on the body is thought to give magical protection as well as beauty; that in India, where cowdung is revered as sacred and the ritual distinction between the left hand (used at the toilet) and the right (putting food into the mouth) is an issue of capital moment, a ritual smearing of the forehead and body with colored clays and ash is a prominently developed religious exercise; and, finally, that among many advanced as well as primitive peoples the sacred clowns — who in religious ceremonies are permitted to break taboos and always enact obscene pantomimes — are initiated into their orders by way of a ritual eating of filth.

Among the Jicarilla Apache of New Mexico the members of the clown society are actually called “Striped Excrement.” [Note 24] They are smeared with a white clay and have four black horizontal stripes crossing their legs, body, and face [Note 25] In our own circuses the clown is garishly painted, breaks whatever taboos the police permit, and is a great favorite of the youngsters, who perhaps see reflected in his peculiar charm the paradise of innocence that was theirs before they were taught the knowledge of good and evil, purity and filth.

A fourth constellation of imprints engraved on the maturing psyche of the infant appears (at east in those provinces of our own civilization that have been studied for these effects) at about the age of four, when the physical difference between the sexes becomes a matter of keen concern. The petite différence leads the girl to believe (we are told) that she has been castrated, and the boy that he is liable to be. Thereafter, in the masculine imagination all fear of punishment is freighted with an obscurely sensed castration fear, while the female is obsessed with an envy that cannot be quite quenched until she has brought forth from her own body a son. Hence the value, from the female point of view, of the madonna image and the whole system of religious references imputing cosmic significance to her womb and breasts. But in the male the sense of her dangerous envy is ever present. Hence the negative estimate of the woman as a potential spiritual, if not physical, castrator, which in the mind of the child tends to become associated with the image of the ogress and cannibal witch, and in religious traditions where a monastic spirit prevails is an extremely prominent trait.

In this connection it should be noted that there is a motif occurring in certain primitive mythologies, as well as in modern surrealist painting and neurotic dream, which is known to folklore as “the toothed vagina” — the vagina that castrates. And a counterpart, the other way, is the so-called “phallic mother,” a motif perfectly illustrated in the long fingers and nose of the witch. According to Freud, [Note 26] the capacity of the sight of a spider to precipitate a crisis of neurotic anxiety — whether in the nursery rhyme of Miss Muffett or in the labyrinths of modern life — derives from an unconscious association of the spider with the image of the phallic mother; to which, perhaps, should be added the observation that the web, the spiral web, may also contribute to the arachnid’s force as a fear-releasing sign.

There is a myth of the Andamanese, according to which there were at first no women in the world, only men. Sir Monitor Lizard (whom we shall later meet at leisure) captured one of these, cut off his genitals, and took him to wife. Their progeny became the ancestors of the only race in the world with which the Andamanese and their mythology are concerned — to wit, the Andamanese. [Note 27]

According to another myth — told in New Mexico by the Jicarilla Apache Indians [Note 28] — there once was a murderous monster called Kicking Monster, whose four daughters at that time were the only women in the world possessing vaginas. They were “vagina girls.” And they lived in a house that was full of vaginas. “They had the form of women,” we are told, “but they were in reality vaginas. Other vaginas were hanging around on the walls, but these four were in the form of girls with legs and all body parts and were walking around.” As may be imagined, the rumor of these girls brought many men along the road; but they would be met by Kicking Monster, kicked into the house, and never returned. And so Killer-of-Enemies, a marvelous boy hero, took it upon himself to correct the situation.

Outwitting Kicking Monster, Killer-of-Enemies entered the house, and the four girls approached him, craving intercourse. But he asked, “Where have all the men gone who were kicked into this place?” “We ate them up,” they said, “because we like to do that”; and they attempted to embrace him. But he held them off, shouting, “Keep away! That is no way to use the vagina.” and then he told them, “First I must give you some medicine, which you have never tasted before, medicine made of sour berries; and then I’ll do what you ask.” Whereupon he gave them sour berries of four kinds to eat. “The vagina,” he said, “is always sweet when you do like this.” The berries puckered their mouths, so that finally they could not chew at all, but only swallowed. “They liked it very much, though,” declared the teller of the story. “It felt just as if Killer-of-Enemies was having intercourse with them. They were almost unconscious with ecstasy, though really Killer-of-Enemies was doing nothing at all to them. It was the medicine that made them feel that way.

“When Killer-of-Enemies had come to them,” the story-teller then concluded, “they had had strong teeth with which they had eaten their victims. But his medicine destroyed their teeth entirely.” [Note 29] And so we see how the great boy hero, once upon a time, domesticated the toothed vagina to its proper use.

Now it must have occurred to the reader during the preceding review of a series of imprints that, although a number of the images discussed are no doubt impressed upon our “open” IRMs from without, certain others can be the products only of the nervous structure itself. For where in the world would the cannibal ogress be? Or where the phallic mother and toothed vagina? Judging from the power of such images to release affects in children, as well as in many adults, we should call them sign stimuli of considerable force. Yet they are not in nature, but have been created by the mind. Whence then? Whence the images of nightmare and of dream?

Perhaps a suggestive analogy is to be seen in the case of the grayling moth, which prefers darker mates to those actually offered by its present species. For if human art can offer to a moth the supernormal sigh stimulus to which it responds more eagerly than to the normal offerings of life, it can surely supply supernormal stimuli, also, to the IRMs of man — and not only spontaneously, in dream and nightmare, but even more brilliantly in the contrived folktales, fairy tales, mythological landscapes, over-and underworlds, temples and cathedrals, pagodas and gardens, dragons, angels, gods, and guardians of popular and religious art. It is true, of course, that the culturally developed formulations of these wonders have required in many cases centuries, even millenniums, to complete. But it is true also (and this, I believe, is what the present review is showing) that there is a point of support for the reception of such images in the déjà vu of the partially self-shaped and self-shaping mind. In other words, whereas in the animal world the “isomorphs,” or inherited stereotypes of the central nervous structure, which for the most part match the natural environment, may occasionally contain possibilities of response unmatched by nature, the world of man, which is now largely the product of our own artifice, represents — to a considerable extent, at least — an opposite order of dynamics; namely, that of a living nervous structure and controlled response system fashioning its habitat, and not vice versa; but fashioning it not always consciously, by any means; indeed, for the most part, or at least for a very considerable part, fashioning it impetuously, out of its own self-produced images of rage and fear.

A fifth and culminating syndrome of imprints of this kind, mixed of outer and inner impacts, is that of the long and variously argued Oedipus complex, which, according to the orthodox Freudian school, is normally established in the growing child at the age of about five or six, and thereafter constitutes the primary constellating pattern of all impulse, thought and feeling, imaginative art, philosophy, mythology and religion, scientific research, sanity and madness. The claim for the universality of this complex has been vigorously challenged by a number of anthropologists; for example, Bronislaw Malinowski, who in his work on Sex and Repression in Savage Society declares, “The crux of the difficulty lies in the fact that to psychoanalysts the Oedipus complex is something absolute, the primordial source…the fons et origo of everything….I cannot conceive of the complex as the unique source of culture, of organization and belief,” he goes on then to say; “as the metaphysical entity, creative, but not created, prior to all things and not caused by anything else.” [Note 30] Géza Róheim, on the other had, replied in defense of Freud in a strong rebuttal, [Note 31] to which, as far as I know, there has been no response. However, since our problem for the present is not that of the ultimate force or extent in time and space of this imprint, but that simply of the possibility of its derivation from infantile experience, we may say that whether it is quite as universal as strict Freudians believe, or significantly modified in force and character according to the sociology of the tribe or family in question, the fact remains that at about the age of five or six the youngster becomes implicated imaginatively (in our culture world, at least) in a ridiculous tragi-comedy that we may term “the family romance.”

In its classical Freudian structuring, this Oedipal romance consists in the more or less unconscious wish of the boy to eliminate his father (Jack-the-Giant-Killer motif) and be alone with his mother; but with a correlative fear, which is also more or less unconscious, of a punishing castration by the father. And so here, at last, the imprint of the Father has entered the psychological picture of the growing child — in the way of a dangerous ogre. As Róheim represents the case in his study of the psychology of primitive warfare, the father is the first enemy, and every enemy i symbolic of the father; [Note 32] indeed, “whatever is killed becomes father.” [Note 33] Hence certain aspects of the headhunting rites, to which we shall presently be turning; hence, too, the rites of the paleolithic hunters in connection with the killing and eating of their totem beasts.

For the girl, the corresponding Freudian formula is that of the legend of Electra. She is her mother’s rival for the father’s love, living in fear that the ogress may kill him and draw herself back into the web of the nightmare of that presexual cannibal feast (formerly paradise!) of the bambino and madonna. for times have changed, and it is now the little girl herself who is to play the madonna — to a brood of dolls.

Since the following chapters furnish abundant instances of this romance of a Lilliputian and Two giants, we need not pause to document it here, but observe, simply, that one example has already been supplied in the episode of Killer-of-Enemies (the boy hero), Kicking Monster (the father-ogre), and the Four Vagina Girls (who are dangerous in the father’s service but susceptible of domestication). Four is ritual number in American Indian lore, referring to the four directions of the universe, and appears in this story because the figures have no personal, or historical, but rather a cosmic mythological reference. The girls ar personifications of an aspect of the mystery of life.

And so, finally, to conclude this brief sketch of the Freudian notion of the family romance and its variations, the reaction of the very young male who vaguely senses that his mother is a temptress, seducing his imagination to incest and parricide, may be to hide his feelings from his own thoughts by assuming the compensatory, negative attitude of a Hamlet — a mental posture of excessive submission to the jurisdiction of the father (atonement theme), together with a fierce rejection of the female and all the associated charms of the world (the fleshpots of Egypt, whore of Babylon, etc.):

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past,

That youth and observation copied there;

And thy commandment all alone shall live

Within the book and volume of my brain,

Unmixed with baser matter: yes, by heaven!

O most pernicious woman!

O villain, villain, smiling, damned villain! [Note 34]

Here we are on the way to the worship of the omnipotent father alone, monkdom, puritanism, Platonism, celibate clergies, homosexuality, and all the rest. And there is much of this, too, to be found in the chapters to come.

For as long as the nuclear unit of human life has been a man, woman, and child, the maturing consciousness has had to come to a knowledge of its world through the medium of this heavily loaded, biologically based triangle of love and aggression, desire and fear, dependency, command, and the urge for release. It is a cooky-mold competent to shape the most recalcitrant dough. So that, even should it finally be shown, somehow, that the human nervous system is without innate form, we should still not be surprised to find in all mythology an order of sign stimuli derived from the engrams of these inevitables.

IV. The Spontaneous Animism of Childhood

It is during the years between six and twelve that youngsters in our culture, and apparently in most others, develop their personal skills and interests, moral judgments, and notions of status. The differentiating factors of the various natural and social environments now begin to preponderate to such a degree that further talk of common modes of thought and action might seem to be out of place. Yet all the new, structuring impressions, derived form the greatly differing local scenes, whether accidental in their impact or pedagogically systematized in imposed routines of training, are received in terms of the mentality not of adulthood but of growing childhood, which has certain common traits throughout the world.

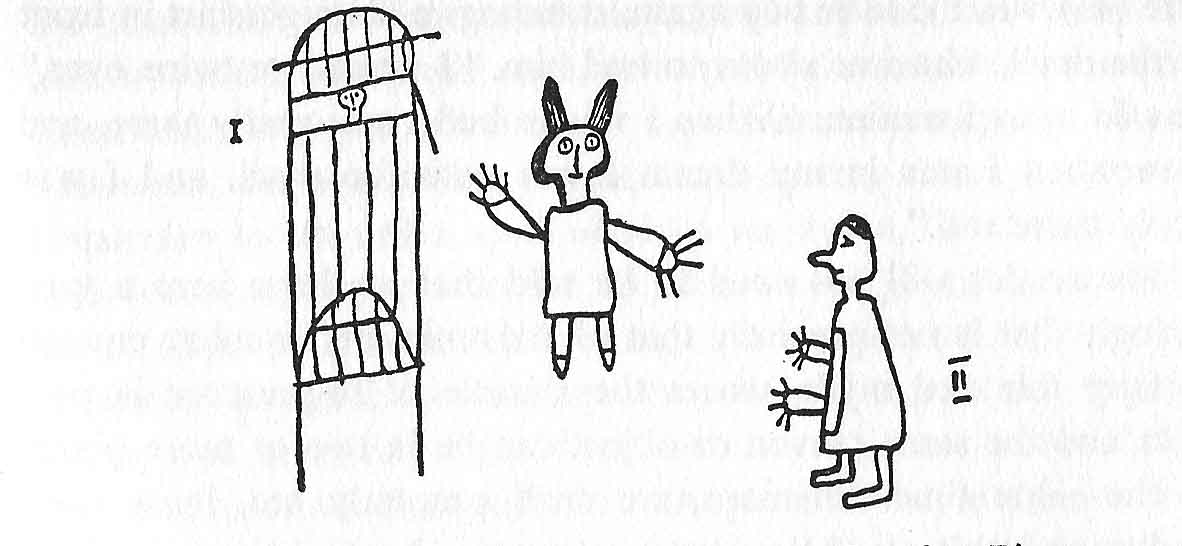

Figure 4. A child’s drawing of his dream of the devil. After

Piaget

The enigma of the dream, for example, is at first interpreted as in no sense mental: it is external to the dreamer, even though invisible to others. And the memory of the dream is confused with ordinary memories, so that the two worlds are mixed. [Note 35] A little boy of five years and six months was asked, “Is the dream in your head?” and he answered, “I am in the dream, it is not in my head. When you dream you don’t know you are in bed. You know you are walking: you are in the dream. You are in bed, but you don’t know you are.” [Note 36] Even at the age of seven or eight, when dreams can be recognized as arising in the head instead of coming from outside — from the moon, from the night, from the lights in the room or in the street, or from the sky — they are still regarded as in some way external. “I dreamt that the devil wanted to boil me,” said a little fellow of seven, explaining a picture that he had drawn (figure above). On the left (I) was the child himself, in bed. “That’s me,” he said. “It was specially my eyes that stayed there — to see.” In the center was the devil. And on the right of the picture (II) was the little boy again, standing in his nightshirt in front of the devil, who was about to boil him. “I was there twice over,” he said in explanation. “When I was in bed I was really there, and then when I was in my dream I was with the devil, and I was really there too.”

The reader will not need to be told that we have here a type of logic that is not precisely that of Aristotle, but familiar enough in fairy tale and myth, where the miracle of bi-presence is possible and the same person or object can be in two or more places at the same time. Shamans, we shall presently see, leave their bodies and ride on their drums or mounts beyond the bounds of the visible world, to engage in adventures with devils and gods, or with other shamans, all of whom, likewise, can be in more that one place at a time. Or we may think of the Roman Catholic dogma of the multipresence of Christ in the sacrament of the altar. “There are not as many bodies of Christ as there are tabernacles in the world, or as there are Masses being said at the same time,” it is declared in a Catholic catechism of Christian doctrine, “but only one body of Christ, which is everywhere present, whole and entire in the Holy Eucharist, as God is everywhere present, while he is but one God.” [Note 37] Or one may think of the multipresence of the Hindu savior, Kṛṣṇa, when he was dancing with the many milkmaids of Vrindavan; and the charming explanation of the religious experience of multipresence that was given by the maids of Vrindavan to one of their number. “I see Kṛṣṇa everywhere,” the beautiful Radha had said, and they replied, “Darling, you have painted your eyes with the collyrium of love; that is why you see Kṛṣṇa everywhere.” [Note 38]

We have noted that in the world of the infant the solicitude of the parent conduces to a belief that the universe is oriented to the child’s own interest and ready to respond to every thought and desire. This flattering circumstance not only reinforces the primary indissociation between inside and out, but even adds to it a further habit of command, linked to an experience of immediate effect. The resultant impression of an omnipotence of thought — the power of thought, desire, a mere nod or shriek, to bring the world to heel — Freud identified as the psychological base of magic, and the researches of Piaget and his school support this view. The child’s world is alert and alive, governed by rules of response and command, not by physical laws: a portentous continuum of consciousness, endowed with purpose and intent, either resistant or responsive to the child itself. And as we know, this infantile notion (or something much like it) of a world governed rather by moral than by physical laws, kept under control by a super-ordinated parental personality instead of impersonal physical forces, and oriented to the weal and woe of man, is an illusion that dominates men’s thought in most parts of the world — or even most men’s thoughts in all parts of the world — to the very present. We are dealing here with a spontaneous assumption, antecedent to all teaching, which has given rise to, and now supports, certain religious and magical beliefs, and when reinforced in turn by these remains as an absolutely ineradicable conviction, which no amount of rational thought or empirical science can quite erase.

And so now it must be observed that, just as the imprints discussed in Section III of the present chapter are susceptible of either infantile or adult interpretation, so too are these experiences of indissociation. For even from the point of view of a strictly biological observation it can be shown that in a certain sense the indissociation of the child has a deeper validity than the adult experience of individuation. Biologically, the individual organism is in no sense independent of its world. For society is not, as Ralph Linton assumed, “a group of biologically distinct and self-contained individuals.” Nor is society, indeed, apart from nature. Between the organism and its environment there exists what Piaget has termed “a continuity of exchanges.” [Note 39] An internal and an external pole have to be recognized, “but each term is in a relation of constant equilibrium and natural dependence with respect to the other.” And it is only relatively slowly that a notion of individual freedom and sense of independence are developed — which then, however, may conduce not only to a manly sense of self- sufficiency and an order of logic in which subjective and objective are rationally kept apart, but to a deterioration of the unity of the social order as well, and to a sense of separateness, which may end in a general atmosphere of anxiety and neurosis.

It has been one of the chief aims of all religious teaching and ceremonial, therefore, to suppress as much as possible the sense of ego and develop that of participation. Such participation, in primitive cults, is principally in the organism of the community, which itself is conceived as participating in the natural order of the local environment. But to this there may be added the larger notion of a community including the dead as well — as, for example, in the Christian idea of the Church Militant, Suffering, and Triumphant: on earth, in purgatory, and in heaven. And finally, in all mystical effort the great goal is the dissolution of the dewdrop of the self in the ocean of the All: the stripping of self and the beholding of the Face.

“And when Thou didst approach my unworthiness with Thy greatly desired face, which bestows all bliss,” wrote Saint Gertrude of Helfta (1256-1302), “I felt that a light, ineffably vivifying, proceeded from Thy divine eyes into mine. Penetrating my entire inner being, it produced in every member a most marvelous effect, inasmuch as it dissolved my flesh and bones to the very marrow; so that I had the feeling that my whole substance was nothing but that divine splendor which, playing upon itself in an indescribably delightful way, was communicating to my soul incomparable serenity and joy.” [Note 40]

A like sentiment appears in the well-known verse of the Indian Brhadaranyaka Upaniṣad (c. 800 b.c.): “Just as a man, when in the embrace of a beloved wife, knows nothing within or without, so does this being, when embraced by the Supreme Self, know nothing within or without.” [Note 41]

Among the treasures of the Buddhist mystics of Japan we find the following in the journal of the sandal-maker Saichi (c. 1850-1933):

My heart and Thy heart —

The oneness of hearts —

“Homage to Amida Buddha!” [Note 42]

And once again, in the words of Omar Khayyam (1048?-1126):

My being is of Thee, and Thou art mine,

And I am Thine, since I am Lost in Thee! [Note 43]

In childhood the earliest questions asked concerning the origins of things betray the spontaneous assumption that somebody made them. “Who made the sun?” asks the child of two years and a half. “Who puts the stars in the sky at night?” asks another of three and a half. [Note 44] In these early ruminations the first point of focus is the problem of origin of the child itself, the second, the origin of mankind, and the last, the origin of things; but the compass of the search presents even learned parents with more than they can handle in the way of scientific and metaphysical challenge. One little boy, for example, presented his scholarly father with the following recorded series:

At two years and three months: “Where do eggs come from?” And when told: “Well, what do mummies lay?”

At two years and six months: “Papa, were there people before us?” Yes. “How did they come there?” They were born, like us. “Was the earth there before there were people on it?” Yes. “How did it get there if there were no people to make it?”

At three years and seven months: “Who made the earth?”

And at four years and five months: “Was there a mummy before the first mummy?”

At four years and nine months: “How did the first man get here without having a mummy?”

And only then, but shortly following: “How was water made?” “What are rocks made of?” [Note 45]

The first notion entertained by the majority of the youngest children seems to be that babies are not born or made, but found. “Mamma, where did you find me?” asked a youngster of three years and six months. “Mamma, where did I come from?” asked another, of three and eight. “Where is the baby now that a lady is going to have next summer?” asked one little genius of four years and ten months; and, when told: “Has she eaten it, then?” Another: “Do people turn back into babies when they get very old?” Or again, at an age of five years and four months: “When you die, do you grow up again?” [Note 46]

As Professor Piaget observes, in this first stage of theorization babies are thought to pre-exist; however, it is realized that parents must have something to do with the mystery. The reader will have noted that the various explanations on this level come very close to certain well- known primitive and archaic ideas; for example, that of conception through eating, which is found in myths and folktales throughout the world; or the idea of rebirth, which is perhaps already suggested even in the burial, circa 100,000 b.c., of Neanderthal Man.

The second type of infantile question concerning birth involves the problem not only of the whence but also that of the how. But this time the child’s interest in his own acts of creation, liquid and solid, has suggested at least two possibilities, which he is not usually willing to formulate, yet may be covertly testing through his questions. The queries just cited concerning the origins of water and rocks are manifest examples. Some sort of mysterious fabrication by the parents is supposed, either outside of their bodies or within, and these vaguely conceived processes then are taken to be possible models for the creation of other things in the world as well. The child begins by assuming that adults were the makers of all things; for they are thought to be omniscient and omnipotent until events make is all too evident that they are neither. Whereupon the cherished image of an all-knowing, all-potent, manually or otherwise creating parent is simply transferred to the vague figure of an anthropomorphic though invisible God, which has already been furnished by parental or other instruction.

The figure of a creative being is practically, if not absolutely, universal in the mythologies of the world, and just as the parental image is associated in childhood not only with the power to make all things but also with the authority to command, so also in religious thought the creator of the universe is commonly the giver and controller of its laws. The two orders — the infantile and the religious — are at least analogous, and it may well be that the latter is simply a translation of the former to a sphere out of range of critical observation. Piaget has pointed out that although the little myths of genesis invented by children to explain the origins of themselves and of things may differ, the basic assumption underlying all is the same: namely, that things have to be made by someone, and that they are alive and responsive to the commands of their creators. The origin myths of the world’s mythological systems differ too; but in all except the most rarefied the conviction is held (as in childhood), without proof, that the living universe is the handiwork or emanation — psychical or physical — or some father-mother or mother-father God.