Chapter 6

Shamanism

I. The Shaman and the Priest

Among the Indians of North America two contrasting mythologies appear, according to whether tribes are hunters or planter. Those that are primarily hunters emphasize in their religious life the individual fast for the gaining of visions. The boy of twelve or thirteen is left by his father in some lonesome place, with a little fire to keep the beasts away, and there her fasts and prays, four days or more, until some spiritual visitant comes in dream, in human or animal form, to speak to him and give him power. His later career will be determined by this vision; for his familiar may confer the power to cure people as a shaman, the power to attract and slaughter animals, or the ability to become a warrior. And if the benefits gained are not sufficient for the young man’s ambition, he may fast again, as often as he likes. An Old Crow Indian named One Blue Bead told of such a fast. “When I was a boy,” he said, “I was poor. I saw war parties come back with leader in front and having a procession. I used to envy them and I made up my mind to fast and become like them. When I saw the vision I got what I had longed for….I killed eight enemies.” [Note 1] If a man has bad luck, he knows that his gift of supernatural power simply is insufficient; while, on the other had, the great shamans and war leaders have acquired power in abundance from their visionary fasts. Perhaps they have chopped off and offered their finger joints. Such offerings were common among the Indians of the plains, on some of whose old hands there remained only fingers and joints enough to enable them to notch an arrow and draw the bow.

Among the planting tribes — the Hopi, Zuni, and other Pueblo dwellers — life is organized around the rich and complex ceremonies of their masked gods. These are elaborate rites in which the whole community participates, scheduled according to a religious calendar and conducted by societies of trained priests. As Ruth Benedict observed in her Patterns of Culture: “No field of activity competes with ritual for foremost place in their attention. Probably most grown men among the western Pueblos give to it the greater part of their waking life. It requires the memorizing of an amount of word-perfect ritual that our less trained minds find staggering, and the performance of neatly dovetailed ceremonies that are chartered by the calendar and complexly interlock all the different cults and the governing body in endless formal procedure.” [Note 2] In such a society there is little room for individual play. There is a rigid relationship not only of the individual to his fellows, but also of village life to the calendric cycle; for the planters are intensely aware of their dependency upon the gods of the elements. One short period of too much or too little rain at the critical moment, and a whole year of labor results in famine. Whereas for the hunter — hunter’s luck is a very different thing.

We have already read one typical account of an American Indian’s quest for his vision in the legend of the origin of maize. The Ojibway tribe, from whom that version of this widely spread legend was derived, were on a cultural level, when Schoolcraft lived among them, approximately equivalent to that of the Natufians of the archaic Near East, c. 6000 b.c. They were a hunting and fighting people of Algonquin stock, and their main body of myths and tales was of a hunting, not a planting, tradition. Nevertheless, they had recently acquired from the agricultural peoples of the much more highly developed south the arts of planting, reaping, and preparing maize, which they were now using to supplement their gains from the chase. And with the maize had come the old, old myth of the wonderful plant-Dema, which we first encountered among the cannibals of Indonesia and saw as having crossed the Pacific with the cocopalm. In South America it has been applied by hundreds of tribes to the various food plants of that richly fruitful continent, and here, in North America, we have found it again, accommodated not only to the tall green growth and feathered crest of the maize, but also to an alien style of mythological thought, that of the vision. We do not hear in this tale of a great group, the “people” of the mythological age, but of a single youth — just such a boy as each would be in his own visionary quest in that great solitude of which our Eskimo shaman, Igjugarjuk, has already told, which “can open the mind of a man to all that is hidden to others.”

The contrast between the two world views may be seen more sharply by comparing the priest and the shaman. The priest is the socially initiated, ceremonially inducted member of a recognized religious organization, where he holds a certain rank and functions as the tenant of an office that was held by others before him, while the shaman is one who, as a consequence of a personal psychological crisis, has gained a certain power of his own, The spiritual visitants who came to him in vision had never been seen before by any other; they were his particular familiars and protectors. The masked gods of the Pueblos, on the other had, the corn-gods and the cloud-gods, served by societies of strictly organized and very orderly priests, are the well-known patrons of the entire village and have been prayed to and represented in the ceremonial dances since time out of mind.

In the origin legend of the Jicarilla Apache Indians of New Mexico there is an excellent illustration of the capitulation of the style of religiosity represented by the shamanism of a hunting tribe to the greater force of the more stable, socially organized and maintained priestly order of a planting-culture complex. The Apache, like their cousins the Navaho, were a hunting tribe that entered the area of the maize-growing Pueblos in the fourteenth century a.d. and assimilated, with characteristic adaptations, much of the local neolithic ceremonial lore. [Note 3] The myth in question is fundamental to their present concept of the nature and history of the universe and is clearly of southern derivation, associated with the rites and social order of a planting culture, and — as we shall see — concerned rather to integrate the individual in a firmly ordered, well- established communal context than to release him for the flights of his own wild genius, wheresoever they may lead.

“In the beginning,” we are told, “nothing was here where the world now stands: no earth — nothing but Darkness, Water, and Cyclone. There were no people living. Only the Hactcin existed. It was a lonely place. There were no fishes, no living things. But all the Hactcin were here from the beginning. They had the material out of which everything was created. They made the world first, the earth, the underworld, and then they made the sky. They made Earth in the form of a living woman and called her Mother. They made Sky in the form of a man and called him Father. He faces downward, and the woman faces up. He is our father and the woman is our mother.” [Note 4]

The Hactcin are the Apache counterparts of the masked gods of the Pueblo villages: personifications of the powers that support the spectacle of nature. The most powerful of their number, Black Hactcin — the myth continues — made an animal of clay and then spoke to it. “Let me see how you are going to walk on those four feet,” he said. Then it began to walk. “That’s pretty good,” said the Hactcin. “I can use you.” And then he said, “But you are all alone. I shall make it so that you shall have others from your body.” And then all sorts of animals came from that one body; for Black Hactcin had power: he could do anything. At that time all those animals could speak, and they spoke the Jicarilla Apache language.

The world creator, Black Hactcin, held out his hand, and a drop of rain fell into the palm. He mixed this with earth and it became mud. Then he fashioned a bird from the mud. “Let me see how you are going to use those wings to fly,” he said. The mud turned into a bird and flew around. “Well, that’s just fine!” said Black Hactcin, who enjoyed seeing the difference between this one and the ones with four legs. “But,” he said, “I think you need companions.” Then he took the bird and whirled it around rapidly in a clockwise direction. The bird grew dizzy, and, as one does when dizzy, saw many images round about. He saw all kinds of birds there, eagles, hawks, and small birds too, and when he was himself again, there were all those birds, really there. And birds love the air, dwell high, and seldom light on the ground, because the drop of water that became the mud out of which the first bird was made fell from the sky.

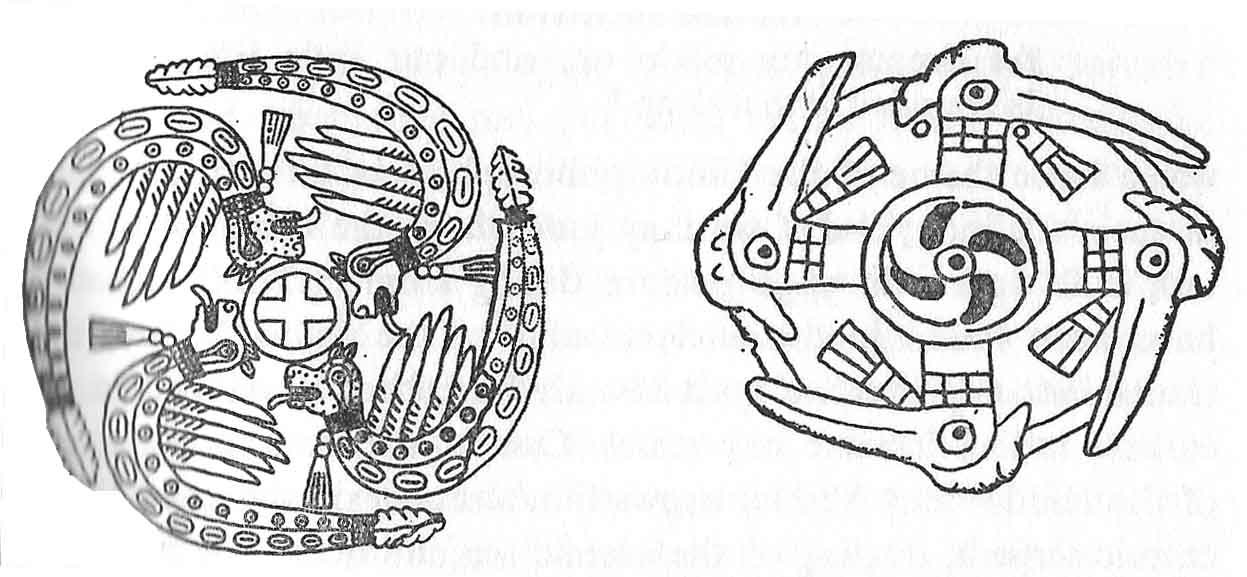

Figure 8. Designs from shell gorgets, Spiro Mound, Oklahoma

The clockwise whirling image form which the birds of the air were produced suggests those designs on the earliest Samarra pottery of the Mesopotamian high neolithic (c. 5000-4800 b.c.)* where the forms of animals and birds emerge from a whirling swastika, and it is surely by no mere accident or parallel development that similar designs — as those in the figures above — occur among the prehistoric North American mound-builder remains, or that in the ritual life and symbolism of the present Indians of the Southwest — the Pueblos, Navaho, and Apache — the swastika plays a prominent part. This circumstance, however, may supply us not only with additional evidence of a broad cultural diffusion, but also with a clue to the sense of the swastika in the earliest neolithic art and cult, both in the Old World and in the New.

The creator whirled the bird in a clockwise direction and the result was an emanation of dreamlike forms. But swastikas, counter-clockwise, appear on many Chinese images of the meditating Buddha; and the Buddha, we know, is removing his consciousness from just this field of dreamlike, created forms — reuniting it through yogic exercise with that primordial abyss or “void” from which all springs.

Stars, darkness, a lamp, a phantom, dew, a bubble,

A dream, a flash of lightning, or a cloud:

Thus should one look upon the world. [Note 5]

This we read in a celebrated Buddhist text, The Diamond-Cutter Sūtra, which has had an immense influence on Oriental thought.

Now I am not going to suggest that there has been any Buddhist influence on Apache mythology. There has not! However, the poignant thought that Calderon, the great Spanish playwright, expressed in his work La Vida es Sueno (“Life is a Dream”), and that his contemporary, Shakespeare, represented when he wrote,

We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep, [Note 6]

was a basic theme of the Hindu philosophers in the earliest phase of their tradition; and if we may judge from the evidence of certain little figures in yoga posture dating from c. 2000 b.c. that have been found in the ancient ruins of the Indus Valley, this trance-inducing exercise must already have been developed in the earliest Indian hieratic city states. One of the best-known forms of the Hindu deity Viṣṇu shows him sleeping on the coils of the cosmic serpent, floating on the cosmic sea and dreaming the lotus-dream of the universe, of which we all are a part. What I am now suggesting, therefore, is that in this Apache legend of the creation of the bird we have a remote cognate of the Indian forms, which must have proceeded from the same neolithic stock; and that in both cases the symbol of the swastika represents a process of transformation: the conjuring up (in the case of the Hactcin), or conjuring away (in the case of the Buddha), of a universe that because of the fleeting nature of its forms may indeed be compared to the substance of a mirage, or of a dream.

Well, the birds all presently came to their creator, Black Hactcin, and asked, “What shall we eat?” He lifted his hand to each of the four directions, and because he had so much power, all kinds of seeds fell into his had, and he scattered them. The birds went to pick them up, but the seeds all turned to insects, worms and grasshoppers, and they moved and hopped around, so that the birds, at first, could not catch them. The Hactcin was trying to tease them. He said, “Oh yes! It’s hard work to catch those files and grasshoppers, but you can do it.” And so they all chased the grasshoppers and other insects around; and that is why they are doing that to this day.

Now presently all the birds and animals came to Black Hactcin and told him that they wanted a companion; they wanted man. “You are not going to be with us all the time,” they said. and he said, “I guess that will be true. some day, perhaps, I shall go to a place where no one will see me.” And so he told them to gather objects from all directions. They brought pollen from all kinds of plants, and they added red ocher, white clay, white stone, jet, turquoise, red stone, opal, abalone, and assorted valuable stones. and when they had put these before Black Hactcin, he told them to withdraw to a distance. He stood to the east, then to the south, then to the west, then to the north. He took pollen and traced with it the outline of a figure on the ground, an outline just like that of his own body. Then he placed the precious stones and other objects inside this outline, and they became flesh and bones. The veins were of turquoise, the blood of red ocher, the skin of coral, the bones of white rock; the fingernails were of Mexican opal, the pupil of the eye of jet, the white of the eyes of abalone, the marrow in the bones of white clay, and the teeth too were of opal. He took a dark could and out of it fashioned the hair. It becomes a white cloud when you are old.

The Hactcin sent wind into the form that he had formed and made it animate. The whorls at the ends of our fingers indicate the path of the wind at that time of the creation. and at death the wind leaves the body from the soles of the feet, where the whorls at the bottom of the feet represent the path of the wind in its exit. The man was lying down, face downward, with his arms outstretched; and the birds tried to look, but Black Hactcin forbade them to do so. For now the man was coming to life. The man braced himself, leaning on his arms. “Do not look,” said Hactcin to the birds, who were now very much excited. And it is because the birds and animals were so eager to see that people are so curious today, just as you are eager to hear the rest of this story.

“Sit up,” Hactcin said to the man; and then he taught him to speak, to laugh, to shout, to walk, and to run. And when the birds saw what had been done they burst into song. as they do in the early morning.

But the animals thought this man should have a companion. and so Black Hactcin put him to sleep; and when the man’s eyes became heavy he began to dream. He was dreaming that someone, a girl, was sitting beside him. And when he woke up, there was a woman sitting there. He spoke to her, and she answered. He laughed, and she laughed. “Let us both get up,” he said, and they rose. “Let us walk,” he said, and he led her the first four steps: right, left, right, left. “Run” he said, and they both ran. And then once again the birds burst into song, so that the two should have pleasant music and not be lonesome.

Now all of this took place not on the level of the earth on which we now are living, but below, in the womb of the earth; and it was ark; there was neither sun nor moon at that time. So White and Black Hactcin together took a little sun and a little moon out of their bags, caused them to grow, and then sent them up into the air, where they moved from north to south, shedding light all around. This caused a great deal of excitement among the people — the animals, the birds, and the people. But there were a lot of shamans among them at that time, all kinds of shamans among the people — men and women who claimed to have power from all sorts of things. These saw the sun going from north to south and began to talk.

One said, “I made the sun”; another: “No, I did.” They began quarreling, and the Hactcin ordered them not to talk like that. But they kept making claims and fighting. One said, “I think I’ll make the sun stop overhead, so that there will be no night. But no, I guess I’ll let it go. We need some time to rest and sleep.” Another said, “Perhaps I’ll get rid of the moon. We really don’t require any light at night.” But the sun rose the second day and the birds and animals were happy. The next day it was the same. When noon of the fourth day came, however, and the shamans, in spite of what the Hactcin had told them, continued to talk, there was an eclipse. The sun went right up through a hole overhead and the moon followed, and that is why we have eclipses today.

One of the Hactcin said to the boastful shamans, “All right, you people say you have power. Now bring back the sun.”

So they all lined up. In one line were the shamans, and in another all the birds and animals. The shamans began to perform, singing songs and making ceremonies. They showed everything they knew. Some would sit singing and then disappear into the earth, leaving only their eyes sticking out, then return. But this did not bring back the sun. It was only to show that they had power. Some swallowed arrows, which would come out of their flesh at their stomachs. Some swallowed feathers; some swallowed whole spruce trees and spat them up again. But they were still without the sun and moon.

Then White Hactcin said, “All you people are doing pretty well, but I don’t think you are bringing the sun back. Your time is up.” He turned to the birds and animals. “All right,” he said, “now it is your turn.”

They all began to speak to one another politely, as though they were brother-in-law; but the Hactcin said: “You must do something more than speak to one another in that polite way. Get up and do something with your power and make the sun come back.”

The grasshopper was the first to try. He stretched forth his had to the four directions, and when he brought it back he was holding bread. The deer stretched out his hand to the four directions, and when he brought it back he was holding yucca fruit. The bear produced choke-cherries in the same way, and the groundhog, berries; the chipmunk, strawberries; the turkey, maize; and so it went with all. But though the Hactcin were pleased with these gifts, the people were still without the sun and moon.

Thereupon, the Hactcin themselves began to do something. They sent for thunder of four colors, from the four directions, and these thunders brought clouds of the four colors, from which rain fell. Then, sending for Rainbow to make it beautiful while the seeds that the people had produced were planted, the Hactcin made a sand-painting with four little colored mounds in a row, into which they put the seeds. The birds and animals sang, and presently the little mounds began to grow, the seeds began to sprout, and the four mounds of colored earth merged and became one mountain, which continued to rise.

The Hactcin then selected twelve shamans who had been particularly spectacular in their magical performances, and, painting six of them blue all over, to represent the summer season, and six white, to represent the winter, called them Tsanati; and that was the origin of the Tsanati dance society of the Jicarilla Apache. After that the Hactcin made six clowns, painting them white with four black horizontal bands, one across the face, one across the chest, one across the upper leg and one across the lower. The Tsanati and clowns then joined the people in their dance, to make the mountain grow. [Note 7]

It would be difficult to find a clearer statement of the process by which the individualistic shamans, in their paleolithic style of magical practice, were discredited by the guardians of the group-oriented, comparatively complex organization of a seed-planting, food-growing community. Lined up, fitted into uniform, they were given a place in the liturgical structure of a larger whole. The episode thus represents the victory of a socially annointed priesthood over the highly dangerous and unpredictable force of individual endowment. And the teller of the Jicarilla Apache story himself explained the necessity for incorporating the shamans in the ceremonial system. “These people,” he said, “had ceremonies of their own which they derived from various sources, from animals, from fire, from the turkey, from frogs, and from other things. They could not be left out. The had power, and they had to help too.” [Note 8]

I do not know of any myth that represents more clearly than this the crisis that must have faced the societies of the Old World when the neolithic order of the earth-bound villages began to make its power felt in a gradual conquest of the most habitable portions of the earth. The situation in Arizona and New Mexico at the period of the discovery of America was, culturally, much like that which must have prevailed in the Near and Middle East and in Europe from the fourth to second millenniums b.c., when the rigid patterns proper to an orderly settlement were being imposed on peoples used to the freedom and vicissitudes of the hunt. And if we turn our eyes to the mythologies of the Hindus, Persians, Greeks, Celts, and Germans, we immediately recognize, in the well-known, oft-recited tales of the conquest of the titans by the gods, analogies to this legend of the subjugation of the shamans by the Hactcin. The titans, dwarfs, and giants are represented s the powers of an earlier mythological age — -crude and loutish, egoistic and lawless, in contrast to the comely gods, whose reign of heavenly order harmoniously governs the worlds of nature and man. The giants were overthrown, pinned beneath mountains, exiled to the rugged regions at the bounds of the earth, and as long as the power of the gods can keep them there the people, the animals, the birds, and all living things will know the blessings of a world ruled by law.

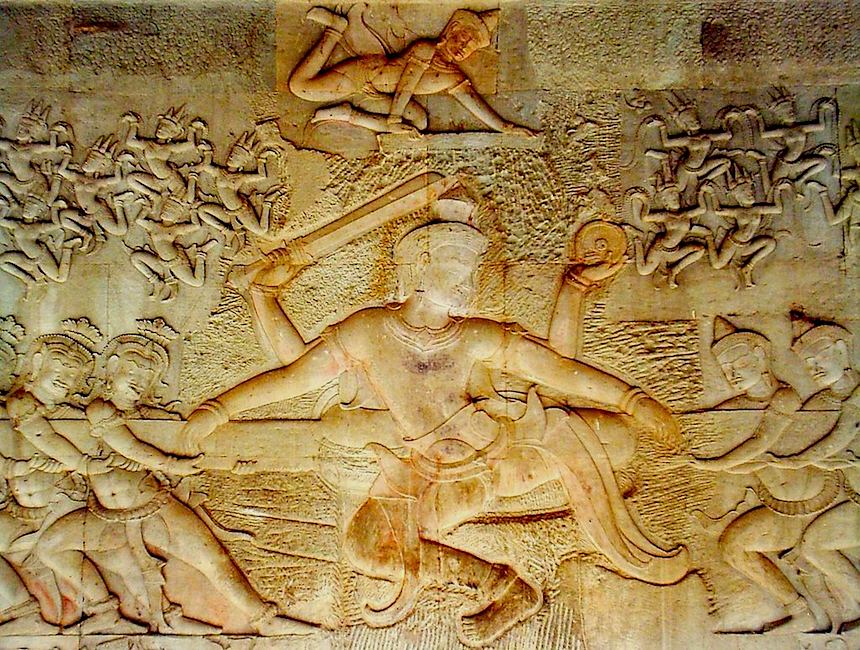

Figure 9. Churning the Milky Ocean

In the Hindu sacred books there is a myth that appears frequently, of the gods and titans cooperating under the supervision of the two supreme deities, Viṣṇu and Śiva, to churn the Milky Ocean for its butter. They took the World Mountain as a churning stick and the World Serpent as a twirling rope, and wrapped the serpent around the mountain. Then, the gods taking hold of the head end of the snake and the demons of the tail, while Viṣṇu supported the World Mountain, they churned for a thousand years and produced in the end the Butter of Immortality. [Note 9]

It is almost impossible not to think of this myth when reading of the efforts of the quarrelsome shamans and orderly people, under the supervison of the Apache Hactcin, to make the World Mountain grow and carry them to the world of light. The Tsanati and clowns, we are told, joined the people in their dance, and the mountain grew, until it top nearly reached the hole through which the sun and moon had disappeared; and it remained, then, only to construct four ladders of light of the four colors, up which the people could ascend to the surface of our present earth. The six clowns went ahead with magical whips to chase disease away and were followed by the Hactcin; and then the Tsanati came; after them, the people and animals. “And when they came up onto the earth,” said the teller of the story, “it was just like a child begin born from its mother. The place of emergence is the womb of the earth.” [Note 10]

The highest concern of all the mythologies, ceremonials, ethical systems, and social organizations of the agriculturally based societies has been that of suppressing the manifestations of individualism; and this has been generally achieved by compelling or persuading people to identify themselves not with their own interests, intuitions, or modes of experience, but with the archetypes of behavior and systems of sentiment developed and maintained in the public domain. A world vision derived from the lesson of the plants, representing the individual as a mere cell or moment in the larger process — that of the sib, the race, or, in larger terms, the species — so devaluates even the first signs of personal spontaneity that every impulse to self- discovery is purged away. “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.” [Note 11] This noble maxim represents the binding sentiment of the holy society — that is to say, the church militant, suffering, and triumphant — of those how do not wish to remain alone.

but, on the other hand, there have always been those who have very much wished to remain alone, and have done so, achieving sometimes, indeed, even that solitude in which the Great Spirit, the Power, the Great Mystery that is hidden from the group in its concerns if intuited with the inner impact of an immediate force. And the endless round of the serpent’s way, biting its tail, sloughing its old skin, to come forth renewed and slough again, is then itself cast away — often with scorn — for the supernormal experience of an eternity beyond the beat of time. Like an eagle the spirit then soars on its own wings. The dragon “Thou Shalt,” as Nietzsche terms the social fiction of the moral law, has been slain by the lion of self-discovery; and the master roars — as the Buddhists phrase it — the lion roar: the roar of the great Shaman of the mountain peaks, of the void beyond all horizons, and of the bottomless abyss.

In the paleolithic hunter’s world, where the groups were comparatively small — hardly more than forty or fifty individuals — the social pressures were far less severe than in the later, larger, differentiated and systematically coordinated long-established villages and cities. And the advantages to the group lay rather in the fostering than in the crushing out of impulse. We have already seen the Ojibway father introduce his son to the solitude on the initiatory fast — the shrine, so to say, of self-discovery, sheer emptiness, with no socially guaranteed image or concept of what the god to be found should be, and with the perfect understanding that whatever the boy should find there would be honored and accepted as the boy’s own divinely given way. And we have seen also the manner of the masked gods of the planters, binding everything into the compass of their own hieratically organized world-society; offering the power of the group as a principle finally and absolutely superior to any of those “ceremonies of their own” which the shamans had derived from the various sources of their own experience.

This, then is to be our first distinction between the mythologies of the hunters and those of the planters. The accent of the planting rites is on the group; that of the hunters, rather, on the individual — though even here, of course, the group does no disappear. Even among the hunters we have the people — the dear people — who bow to one another politely, like brother-in-law, but have comparatively little personal power. And these constitute, even on that level, a group from which the far more potent shamans stand apart. We have read of the Eskimo shaman Najagneq, who carried on a war against his whole village and then faced them out of countenance when they came to accuse him in a court of law. And we have read also of the more primitive Caribou Eskimo shaman Igjugarjuk, who, when he knew the girl he wished to marry, simply took his gun, shot her family from around her, and brought her home. In the villages and town of the planters, however, it is the group and the archetypal philosophy of the group — the philosophy of the grain of wheat that falls into the earth and dies but therein lives, the philosophy imaged in the rites of the monster serpent and the maiden sacrifice — that preponderate and represent perfectly the system of sentiments most conducive to group survival; in the hunter’s world, where the group was never large or strong enough to face down a man who had achieved in his own way his own full stature, it was the philosophy, rather, of the “lion roar” that prevailed.

As we have seen, in some areas (e.g., North America) this shamanistic, individualistic principle prevailed to such an extent that even the puberty rites had as their chief theme the personal quest for a vision. In others (e.g., Central Australia, where a powerful influence from the planting world of Melanesia had been assimilated), a greater emphasis on the age of the ancestors and disciplines of the men’s dancing ground left to the individual very little of his own. Nevertheless, in the main it can be said that in the world of the hunt the shamanistic principle preponderates and that consequently the mythological and ritual life is far less richly developed than among the planters. It has a lighter, more whimsical character, and most of its functioning deities are rather in the nature of personal familiars than of profoundly developed gods. And yet, as we have also seen, there have been depths of insight reached by the mind in the solitude of the tundras that are hardly to be matched in the great group ecstasies of the bull-roarers, borne on the air, heavy with dread.

II. Shamanistic Magic

“From Wakan-Tanka, the Great Mystery, comes all power,” said an old chieftain of the Oglalla Sioux, Chief Piece of Flat Iron, to Natalie Curtis when she was collecting material for The Indians’ Book in the first decade of the twentieth century.

It is all from Wakan-Tanka that the Holy Man has wisdom and the power to heal and to make holy charms. Man knows that all healing plants are given by Wakan-Tanka; therefore they are holy. So too is the buffalo holy, because it is the gift of Wakan-Tanka. The Great Mystery gave to men all things for their food, their clothing, and their welfare. And to man he gave also the knowledge how to use these gifts — how to find the holy healing plants, how to hunt and surround the buffalo, how to know wisdom. For all comes from Wakan-Tanka — all.

To the Holy Man comes in youth the knowledge that he will be holy. The Great Mystery makes him know this. Sometimes it is the Spirits who tell him. The Spirits come not in sleep always, but also when man is awake. When a Spirit comes it would seem as though a man stood there, but when this man has spoken and goes forth again, none may see whither he goes. Thus the Spirits. With the Spirits the Holy Man may commune always, and they teach him holy things.

The Holy Man goes apart to a lone tipi and fasts and prays. Or he goes into the hills in solitude. When he returns to men, he teaches them and tells them what the Great Mystery has bidden him to tell. He counsels, he heals, and he makes holy charms to protect the people from all evil. Great is his power and greatly is he revered; his place in the tipi is an honored one. [Note 12]

Knud Rasmussen received from the Caribou Eskimo shaman Igjugarjuk a full account of the ordeal through which he had acquired his shamanistic power. When young, he had been visited constantly by dreams that could not understand.

Strange unknown beings came and spoke to him, and when he awoke, he saw all the visions of his dream so distinctly that he could tell his fellows all about them. Soon it became evident to all that he was destined to become an angakoq (a shaman) and an old man named Perqanaoq was appointed his instructor. In the depth of winter, when the cold was most severe, Igjugarjuk was placed on a small sledge just large enough for him to sit on, and carried far away from his home to the other side of Hikoligjuag. On reaching the appointed spot, he remained seated on the sledge while his instructor built a tiny snow hut, with barely room for him to sit cross- legged. He was not allowed to set foot on the snow, but was lifted from the sledge and carried into the hut, where a piece of skin just large enough for him to sit on served as a carpet. No food or drink was given him; he was exhorted to think only of the Great Spirit and of the helping spirit that should presently appear — and so he was left to himself and his meditations.

After five days had elapsed, the instructor brought him a drink of lukewarm water, and with similar exhortations, left him as before. He fasted now for fifteen days, when he was given another drink of water and a very small piece of meat, which had to last him a further ten days. At the end of this period, his instructor came for him and fetched him home. Igjugarjuk declared that the strain of those thirty days of cold and fasting was so severe that he “sometimes died a little.” During all that time he thought only of the Great Spirit, and endeavored to keep his mind free from all memory of human beings and everyday things. Toward the end of the thirty days there came to him a helping spirit in the shape of a woman. She came while he was asleep and seemed to hover in the air above him. After that he dreamed no more of her, but she became his helping spirit. For five months, following this period of trial, he was kept on the strictest diet, and required to abstain from all intercourse with women. The fasting was then repeated; for such fasts at frequent intervals are the best means of attaining to knowledge of hidden things. As a matter of fact, there is no limit to the period of study; it depends on how much one is willing to suffer and anxious to learn. [Note 13]

Women to became shamans. In the same Eskimo community was Kinalik: “still a young woman,” as Dr. Rasmussen describes her, “very intelligent, kind hearted, clean and good looking, who spoke frankly and without reserve.”

Igjugarjuk was her brother-in-law and had himself been her instructor in magic. Her initiation had been severe. She was hung up to some tent poles planted in the snow and left there for five days. It was midwinter, with intense cold and frequent blizzards, but she did not feel the cold, for the spirit protected her. when the five days were at an end, she was taken down and carried into the house, and Igjugarjuk was invited to shoot her, in order that she might attain to intimacy with the supernatural by visions of death. The gun was to be loaded with real powder, but a stone was to be used instead of the leaden bullet, in order that she might still retain connection with earth. Igjugarjuk, in the presence of the assembled villagers, fired the shot, and Kinalik fell to the ground unconscious. On the following morning, just as Igjugarjuk was about to bring her to life again, she awakened from the swoon unaided. Igjugarjuk asserted that he had shot her through the heart, and that the stone had afterward been removed and was in the possession of the old mother. [Note 14]

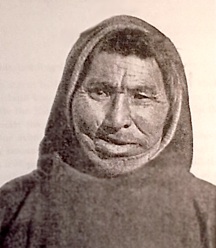

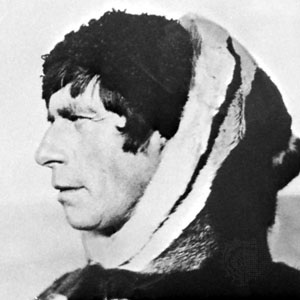

Figure 10a & b. Najagneq and Rasmussen

One gets the impression, however, that, although these Saint Anthonys of the wilderness must truly have suffered in their youthful years of austerity, they have had a tendency to pull the long bow when telling of their trials, or perhaps, rather, to confuse dream reality with daytime events. We have already heard of the ten deaths and resurrections of Rasmussen’s other Eskimo shaman, Najagneq. In the same community with Igjugarjuk there was still another practicing shaman, a young man whose name was Aggjartoq, “who,” as Dr. Rasmussen declares, without the hint of a smile, “had also been initiated into the mysteries of the occult with Igjugarjuk as his teacher; and in his case a third form of ordeal had been employed; to wit, that of drowning. He was lashed to a long pole and carried out onto a lake, a hole was cut in the ice, and the pole with its living burden thrust down through the hole, in such a fashion that Aggjartoq actually stood on the bottom of the lake with hes head under water. He was left in this position for five days and when at last they hauled him up again, his clothes showed no sign of having been in the water at all and he himself had become a great wizard, having overcome death.” [Note 15]

The Caribou Eskimos, dwelling in the cruel arctic wastes west of the northern reaches of Hudson bay, are among the most primitive people on earth; and their counterparts at the other extreme of the New World, on the no less bleak and difficult rocky tip of the southern continent, Tierra del Fuego, are likewise specimens of a type of life that was already out of fashion in the later millenniums of the paleolithic, 35,000–11,000 b.c. It is not known when the people how inhabiting the southern tip of South America — that “uttermost part of the earth” — first arrived in their rocky refuge, pressed down by the later, more highly developed societies of the north; but their ancestors must have crossed to the New World from Siberia many millenniums ago. When first explored by Europeans, the area was found divided among four tribes; the Yahgans (or Yamanas) of the southern coasts, a short and sturdy people who lived largely on fish and limpets, handled canoes with skill, and could occasionally manage to harpoon a seal, porpoise, or even diminutive whale; a considerably taller and comparatively handsome mountain-dwelling people, known as the Ona, in the inland area north of the Yahgans, who lived by the hunt; and to the west and east of these, respectively, the Alacaloof and the Aush, the former, like the Yahgans, a canoe people, and the latter, like the Ona (to whom they were related), a race of hunters. In the year 1870 a mission was established at the site since known as Ushuaia by a courageous young clergyman, Thomas Bridges, whose son Lucas, born at Ushuaia in 1874, has given an account of his long life among his friends the Yahgans and the Ona.

“Some of these humbugs,” he says, describing the medicine men, or joon, of the Ona,

were excellent actors. Standing or kneeling beside the patient, gazing intently at the spot where the pain was situated, the doctor would allow a look of horror to come over his face. evidently he could see something invisible to the rest of us. His approach might be slow or he might pounce, as though afraid that the evil thing that had caused the trouble would escape. with his hands he would try to gather the malign presence into one part of the patient’s body — generally the chest — where he would then apply his mouth and such violently. Sometimes this struggle went on for an hour, to be repeated later. At other times the joon would draw away from his patient with the pretense of holding something in his mouth with his hands. Then, always facing away from the encampment, he would take his hands from his mouth, gripping them tightly together, and, with a guttural shout difficult to describe and impossible to spell, fling, this invisible object to the ground and stamp fiercely upon it. Occasionally a little mud, some flint or even a tiny, very young mouse might be produced as the cause of the patient’s indisposition. I myself have never seen a mouse figure in one of these performances, but they were quite common. Perhaps when I was there the doctor had failed to find a mouse’s nest. [Note 16]

An occasion to observe a considerably more puzzling manifestation of power occurred when a highly celebrated joon named Houshken, who had never seen a white man before, was induced to put on a brief performance for Mr. Bridges, who writes:

Our conversation — as was always the case at such meetings — was slow, with long pauses between sentences, as though for deep thought. I told Houshken that I had heard of his great powers and would like to see some of his magic. He did not refuse my request, but answered modestly that he was disinclined, the Ona way of saying that he might do it by and by.

After allowing a quarter of an hour to elapse, Houshken said he was thirsty and went down to the nearby stream for a drink. It was a bright moonlight night and the snow on the ground helped to make the scene of the exhibition we were about to witness as light as day. On his return, Houshken sat down and broke into a monotonous chant, which went on until suddenly he put his hands to his mouth. When he brought them away, they were palms downward and some inches apart. We saw that a strip of guanaco hide, about the thickness of a leather bootlace, was now held loosely in his hands. It passed over his thumbs, under the palms of his half-closed hands, and was looped over his little fingers so that about three inches of end hung down from each hand. The strip appeared to be not more than eighteen inches long.

Without pulling the strip tight, Houshken now began to shake his hands violently, gradually bringing them farther apart, until the strip, with the two ends still showing, was about four feet long. He then called his brother, Chashkil, who took the end from his right hand and stepped back with it. From four feet, the strip now grew out of Houshken’s left hand to double that length. Then, as Chashkil stepped forward, it disappeared back into Houshken’s hand, until he was able to take the other end from his brother. with the continued agitation of his hands, the strip got shorter and shorter. Suddenly, when his hands were almost together, he clapped them to his mouth, uttered a prolonged shriek, then held out his hands to us, palms upward and empty.

Even an ostrich could not have swallowed those eight feet of hide at one gulp without visible effort. Where else the coil of hide could have gone to I do not profess to know. It could not have gone up Houshken’s sleeve, for he had dropped his robe when the performance began (and, like all male Onas without their robes, was naked). There were between twenty and thirty men present, but only eight or nine were Houshken’s people. The rest were far from being friends of the performer and all had been watching intently. Had they detected some simple trick, the great medicine-man would have lost his influence; they would no longer have believed in any of his magic.

The demonstration was not yet over. Houshken stood up and resumed his robe. Once again he broke into a chant and seemed to go into a trance, possessed by some spirit not his own. Drawing himself up to his full height, he took a step towards me and let his robe, his only garment, fall to the ground. He put his hands to his mouth with a most impressive gesture and brought them away again with fists clenched and thumbs close together. He held them up to the height of my eyes, and when they were less than two feet from my face slowly drew them apart. I saw that there was now a small, almost opaque object between them. It was about an inch in diameter in the middle and tapered away into his hands. It might have been a piece of semi-transparent dough or elastic, but whatever it was it seemed to be alive, revolving at great speed, while Houshken, apparently from muscular tension, was trembling violently.

The moonlight was bright enough to read by as I gazed at this strange object. Houshken brought his hands further apart and the object grew more and more transparent, until, when some three inches separated his hands, I realized that it was not there any more. It did not break or burst like a bubble; it simply disappeared, having been visible to me for less than five seconds. Houshken made no sudden movement, but slowly opened his hands and turned them over for my inspection. They looked clean and dry. He was stark naked and there was no confederate beside him. I glanced down at the snow, and, in spite of his stoicism, Houshken could not resist a chuckle, for nothing was to be seen there.

The others had crowded round us and, as the object disappeared, there was frightened gasp from among them. Houshken reassured them with the remark:

“Do not let it trouble you. I shall call it back to myself again.”

The natives believed this to be an incredibly malignant spirit belonging to, or possibly part of the joon from whom it emanated. It might take physical form, as we had just witnessed, or be totally invisible. It had the power to introduce insects, tiny mice, mud, sharp flints of even a jelly-fish or baby octopus, into the anatomy of those who had incurred its master’s displeasure. I have seen a strong man shudder involuntarily at the thought of this horror and its evil potentialities. It was a curious fact that, although every magician must have known himself to be a fraud and a trickster, he always believed in and greatly feared the supernatural abilities of other medicine-men. [Note 17]

When this account of the functioning of a joon of the Ona is compared with what we have learned of his counterparts in the north, a number of interesting points emerge. Drawn, it will be recalled, from two of the most primitive hunting communities on earth, at opposite poles of the world, and out of touch, certainly for millenniums, with any common point of traditional origin — if such there ever was — the two groups have nevertheless the same notion of the role and character of the shaman, while the shamans themselves have had the same types of experience and face practically the same orders of problem in relation to their practice among their simpler fellows. “He was no humbug,” said Dr. Ostermann in the judgment quoted earlier of the Alaskan ten-horse-power Najagneq, “but a solitary man accustomed to hold his own against many and therefore had to have his little tricks.” And Mr. Bridges, while retaining the view, suitable to the son of a clergyman, that shamans were indeed humbugs, nevertheless recognized that they feared one another’s power. And this element of fear, real fear, is a characteristic reaction wherever men and women of shamanistic power and skill have appeared.

But, reciprocally, the shamans themselves have always lived in fear of their communities. “Medicine men,” wrote Mr. Bridges, “ran great dangers. When persons in their prime died form no visible cause, the ‘family doctor’ would often cast suspicion, in an ambiguous way, on some rival necromancer. Frequently the chief object of a raiding party, in the perpetual clan warfare on the Ona, was to kill the medicine man of an opposing group.” [Note 18] The shaman, as he puts it, “was a creature apart from the honest hunters.” And we have already seen the signs of this separation, not only in the war of the Eskimo Najagneq with the rest of his community, but also in the way of lining the people and the shamans in two rows in the Jicarilla Apache myth.

The shaman has an occult power over nature, which he can use either to harm or to benefit his fellows. Moreover, the shaman need not appear as a human being. Mr. Bridges tells of a mountain hear Ushuaia that was thought to be a witch: to show her ill will, she could conjure up a storm. [Note 19] And he tells also of a solitary guanaco (a kind of wild llama) that he shot high in the mountains, which he and his Indian companions then discovered to have been dwelling, solitary, in a small cave. “These guanaco recluses, braving the long winter in the mountains alone,” writes Mr. Bridges, “were very rare….That night, discussing the matter round our camp-fire, I suggested that the hermit might have remained there alone in the cave to study guanaco magic. Instead of laughing, my companions agreed, with serious expressions on their faces, that this was quite likely.” [Note 20]

The shamanistic affinity with nature, which these two anecdotes of the witch-mountain and the shaman-guanaco suggest, is of a deeper, more occult kind than that of the “honest hunters” of the tribe, no matter how skillful and amazing to the white man the woodcraft of the latter may seem to be. Mr. Bridges — himself no mean woodsman — describes with wonder the almost incredible sensitivity of the Ona to the presences around them in the deep forest; but these same Ona hunters observed with wonder the power over nature of their shaman. For, whereas they could function expertly in relation to its outer aspect, he could work in the manner of a cause, reaching behind the veil and touching those hidden centers that break the normal, natural circuits of energy and create transformations. He could cause ectoplasmic emanations to appear between his violently trembling palms; take the form of a mountain; appear as a beast; conjure up or dispel a storm, and tell, as though reciting tales of his own intimate knowledge and experience, the mythological lore and legends of the tribe.

For in every society in which they have been known, the shamans have been the particular guardians and reciters of the chants and traditions of their people. “Being a joon of repute” wrote Mr. Bridges of his shaman friend, “Tininisk preferred chanting or instructing us in ancient lore to work and drudgery.” [Note 21]

And why not?

The realm of myth, from which, according to primitive belief, the whole spectacle of the world proceeds, and the realm of shamanistic trance are one and the same. Indeed, it is because of the reality of the trance and the profound impression left on the mind of the shaman himself by his experiences that he believes in his craft and its power — even though, for a popular show, he may have to put on a deceptive external performance, imitating for the honest hunters some of the wonders that his spirits have shown him in the magical realm beyond the veil.

This relationship of the shaman’s inner experiences to myth is a supremely important theme and problem of our subject. For if the shaman was the guardian of the mythological lore of mankind during the period of some five or six hundred thousand years when the chief source of sustenance was the hunt, then the inner world of the shaman must be assumed to have played a considerable role in the formation of whatever portion of our spiritual inheritance may have descended from the period of the paleolithic hunt. We must consider, therefore, what the visions within, and springing from, the shamanistic world of experience may have been.

III. The Shamanistic Vision

The inward experiences through which the power of the shaman is attained and from which the motifs of his shamanistic rites derive may be surmised from a survey of autobiographies gathered in recent years from the Buriat, Yakut, Ostyak, Vogul, and Tungus shamans of that vast quadrangle of Siberia — bounded on the west by the Yenisei River, east by the Lena River, south by Lake Baikal, and north by the Taimyr Peninsula — which has been from paleolithic times a classical academy of shamanism and is today its strongest surviving center.

“A person cannot become a shaman if there have been no shamans in his sib,” the Tungus shaman Semyonov Semyon declared, when questioned at his home on the Lower Tunguska River, in the spring of 1925, by the Russian folklorist G.V. Ksenofontov, who was himself a full-blooded Yakut. “Only those who have shaman ancestors in their past receive the shamanistic gift,” said the shaman; “whence the gift descends from generation to generation. My oldest brother, Ilya Semyonov, was a shaman. He died three years ago. My grandfather on my mother’s side was a shaman too. My grandmother on the mother’s side was a Yakut from Chirindi, of the Yessei Yakut sib, Jakdakar.”

“It is to be understood,” Ksenofontov comments, “that these shamans, in their turn, received their shamanistic gift from further representatives of the family line, whose names they knew; so that an unbroken chain of shamanistic tradition has come down from the depth of the centuries. The Yessei Yakut,” he adds, “are most probably Yakutized Tungus.”

“When I shamanize,” the shaman continued,

the spirit of my deceased brother Ilya comes and speak through my mouth. My shaman forefathers, too, have forced me to walk the path of shamanism. Before I commenced to shamanize, I lay sick for a whole year: I became a shaman at the age of fifteen. The sickness that forced me to this path showed itself in a swelling of my body and frequent spells of fainting. When I began to sing, however, the sickness usually disappeared.

After that, my ancestors began to shamanize with me. They stood me up like a block of wood and shot at me with their bows until I lost consciousness. They cut up my flesh, separated my bones, counted them, and ate my flesh raw. When they counted the bones they found one too many; had there been too few, I could not have become a shaman. And while they were performing this rite, I ate and drank nothing for the whole summer. But at the end the shaman spirits drank the blood of a reindeer and gave me some to drink, too.

The same thing happens to every Tungus shaman. Only after his shaman ancestors have cut up his body in this way and separated his bones can he begin to practice. [Note 22]

As Professor Mircea Eliade has shown in his cross-cultural study of shamanism, [Note 23] the overpowering mental crisis here described is a generally recognized feature of the vocational summons. Its counterparts have been registered wherever shamans have appeared and practiced; which is to say, in every primitive society of the world. And though the temporary unbalance precipitated by such a crisis may resemble a nervous breakdown, it cannot be dismissed as such. For it is a phenomenon sui generis; not a pathological but a normal event for the gifted mind in these societies, when struck by and absorbing the force of what for lack of a better term we may call a hierophantic realization: the realization of “something far more deeply interfused,” inhabiting both the round earth and one’s own interior, which gives to the world a sacred character; and intuition of depth, absolutely inaccessible to the “tough minded” honest hunters (whether it be dollars, guanaco pelts, or working hypotheses they are after), but which may present itself spontaneously to such as William James has termed the “tender minded” of our species, [Note 24] and who, as Paul Radin shows in his work on Primitive Man as Philosopher, exist no less in primitive than in higher societies. [Note 25]

The force of such a hierophantic realization is the more compelling for the mind dwelling in a primitive society, inasmuch as the whole social structure, as well as the rationalization of its relationship to the surrounding world of nature, is there mythologically based. The crisis, consequently, cannot be analyzed as a rupture with society and the world. It is, on the contrary, an overpowering realization of their depth, and the rupture is rather with the comparatively trivial attitude toward both the human spirit and the world that appears to satisfy the great majority.

It has been remarked by sensitive observers that, in contrast to the life-maiming psychology of a neurosis (which is recognized in primitive societies as well as in our own, but not confused there with shamanism), the shamanistic crisis, when properly fostered, yields an adult not only of superior intelligence and refinement, but also of greater physical stamina and vitality of spirit than is normal to the members of his group. [Note 26] The crisis, consequently, has the value of a superior threshold initiation: superior, in the first place, because spontaneous, not tribally enforced, and in the second place, because the shift of reference of the psychologically potent symbols has been not from the family to the tribe but from the family to the universe. The energies of the psyche summoned into play by such an immediately recognized magnification of the field of life are of greater force than those released and directed by the group-oriented, group-contrived, visionary masquerades of the puberty rites and men’s dancing ground. They give a steadier base and larger format to the character of the individual concerned, and have tended, also, to endow the phenomenology of shamanism itself with a quality of general human validity, which the local rites — of whatever community — simply do not share. And finally, since the group rites of the hunting societies are, au fond, precipitations into the public field of images first experienced in shamanistic vision, rendering myths best known to shamans and best interpreted by shamans, the painful crisis of the deeply forced vocational call carries the young adept to the root not only of his cultural structure, but also of the psychological structures of every member of his tribe.

In a profound sense, then, the shaman stands against the group and necessarily so, since the whole realm of interests and anxieties of the group is for him secondary. And yet, because he has gone through — in some way, in some sense — to the heart of the world of which the group and its ranges of concern are but manifestations, he can help and harm his fellows in ways that amaze them. But how, then, does he come to such power?

We note first that, just as in the puberty rites, so also in Semyonov’s vision, the structuring theme was an adventure of death and resurrection. We have already mentioned the infantile image of the parent as a cannibal ogre. The point of the shamanistic vision is that, though the victim indeed was eaten, there was a power of restitution inherent in his bones that brought him back to life. He is stronger than death.

Spencer and Gillen have described the corresponding event in the lives of the medicine men of the Aranda. When a man of this Australian tribe feels that he has the power to become a shaman, he leaves the camp alone and proceeds to the mouth of a certain cave, where, with considerable trepidation, not venturing to go inside, he lies down to sleep. At the break of day a spirit comes to the mouth of the cave and, finding the man asleep, throws at him an invisible lance, which pierces his neck from behind, passes through his tongue, and emerges from his mouth. The tongue remains throughout life perforated in the center with a hole large enough to admit the little finger; and, when all is over, this hole is the only visible and outward sign remaining of the treatment. A second lance then thrown by the spirit pierces his head from ear to ear, and the victim, falling dead, is immediately carried into the depths of the cave, within which the spirits live in perpetual sunshine, among streams of running water. The cave in question is supposed to extend far under the plain, terminating at a spot beneath what is called the Edith Range, ten miles away. The spirits there remove all the man’s internal organs and provide him with a completely new set, after which he presently returns to life, but in a condition of insanity. This does not last very long, however. When he has become sufficiently rational, the spirits of the cave — who are invisible to all except a few highly gifted medicine men and to dogs — conduct him back to his own people. He continues to look and behave queerly until, one morning, it is noticed that he has painted with powdered charcoal and fat a broad band across the bridge of his nose. Every sign of insanity has now disappeared, and the new medicine man has graduated. But he must not practice for another year, and if, during this period of probation, the hole in his tongue closes, he will know that his power has departed and will not practice at all. Meanwhile, consorting with the local masters of his profession, he learns the secrets of his craft, “which consist,” as Spencer and Gillen declare, “principally in the ability to hide about his person and to produce at will small quartz pebbles and bits of stick; and, of hardly less importance than this sleight of hand, the power of looking preternaturally solemn, as if he were the possessor of knowledge quite hidden from ordinary men.” [Note 27]

The new intestines of the shaman are composed of quartz crystals, which he is now able to project into people, either for good or for ill. [Note 28] And so here again we see a theme of death and restitution, but with a new body that is adamantine. The Oriental counterpart, which plays a considerable role in both Hindu and Buddhist mystical literature, is the “diamond” or “thunderbolt” body (vajra), which the yogi achieves. On the primitive level it may be proper to read such an idea psychoanalytically, as a reparation fantasy defending the infantile psyche against its own body-destruction anxieties. [Note 29] I do not think, however, that such a reading quite does justice to the reach of Hindu and Buddhist thought, or indeed, to the generally known metaphysical concept of a principle of permanence underlying the phenomenology of temporal change. It is not easy to know how far back into the primitive situation one can press the idea, universal to all the higher traditions of mysticism, of the changing of “our lowly bodies to be like His glorious body” (Philippians 3:21); but I should say, judging from what we have already been told by our Eskimo shamans, that it should be possible to run it back all the way. Nor do I know how tenaciously the reader is going to cling to the idea, advertised by Dr. Freud, that all higher thought, except psychoanalysis, is a function of infantile anxiety. But either way, we have certainly struck here a level or point of experience that would seem to represent precisely what Bastian was referring to when he wrote of elementary ideas. The introversion of the shamanistic crisis and the break, temporarily, from the local system of practical life lead to a field of experience that in the deepest sense transcends provincialism and opens the way at least to a premonition of something else. Indeed, I suspect that we are approaching here the ultimate sanctuary and wellspring of the whole world and wonder — all the magic — of the gods.

Said the Tungus shaman, Semyonov Semyon:

Up above there is a certain tree where the souls of the shamans are reared, before they attain their powers. And on the boughs of this tree are nests in which the souls lie and are attended. The name of the tree is “Tuuru.” The higher the nest in this tree, the stronger will the shaman be who is raised in it, the more he will he know, and the farther will he see.

The rim of a shaman’s drum is cut from a living larch. The larch is left alive and standing in recollection and honor of the tree Tuuru, where the soul of the shaman was raised. Furthermore, in memory of the great tree Tuuru, at each seance the shaman plants a tree with one or more cross-sticks in the tent where the ceremony takes place, and this tree too is called Tuuru. This is done both among us here on the Lower Tunguska and among the Angara Tungus. The Tungus who are connected with the Yakuts call this planted tree “Sarga.” It is made of a long pole of larch. White cloths are hung on the cross-sticks. Among the Angara Tungus they hang the pelt of a sacrificed animal on the tree. The Tungus of the Middle Tunguska make a Tuuru that is just like ours.

According to our belief, the soul of the shaman climbs up this tree to God when he shamanizes. For the tree grows during the rite and invisibly reaches the summit of heaven.

God created two trees when he created the earth and man: a male, the larch; and a female, the fir. [Note 30]

The vision of the tree is a characteristic feature of the shamanism of Siberia. The image can have been derived form the great traditions of the south; it is applied, however, to a distinctly shamanistic system of experience. Like the tree of Wotan, Yggdrasil, it is the world axis, reaching to the zenith. The shaman has been nurtured in this tree, and his drum, fashioned of its wood, bears him back to it in his trance of ecstasy. As Eliade has pointed out, the shaman’s power rests in his ability to throw himself into a trance at will. Nor is he the victim of his trance: he commands it, as a bird the air in its flight. The magic of his drum carries him away on the wings of its rhythm, the wings of spiritual transport. The drum and dance simultaneously elevate his spirit and conjure to him his familiars — the beasts and birds, invisible to others, that have supplied him with his power and assist him in his flight. And it is while in his trance of rapture that he performs his miraculous deeds. While in this trance he is flying as a bird to the upper world, or descending as a reindeer, bull, or bear to the world beneath.

Among the Buriat, the animal or bird that protects the shaman is called khubilgan, meaning “metamorphosis,” from the verb khubilku, “to change oneself, to take another form.” [Note 31] The early Russian missionaries and voyagers in Siberia in the first part of the eighteenth century noted that the shamans spoke to their spirits in a strange, squeaky voice. [Note 32] They also found among the tribes numerous images of geese with extended wings, sometimes of brass. [Note 33] And as we shall soon see, in a highly interesting paleolithic hunting station known as Mal’ta, in the Lake Baikal area, a number of flying geese or ducks were found, carved in mammoth ivory. Such flying birds, in fact, have been found in many paleolithic stations: and on the under-wings of an important example found near Kiev, in the Ukraine, in a site called Mezin, there appears the earliest swastika of which we have record — a symbol associated (as we have already remarked) in the later Buddhist art of nearby China and Tibet with the spiritual flight of the Buddha. Furthermore, in the great paleolithic cavern of Lascaux, in southern France, there is the picture of a shaman dressed in bird costume, lying prostrate in a trance and with the figure of a bird perched on his shaman staff beside him. The shamans of Siberia wear bird costumes to this day, and many are believed to have been conceived by their mothers from the descent of a bird. In India, a term of honor addressed to the master yogi is Paramahaṁsa: paramount or supreme (parama) wild gander (haṁsa). In China the so-called “mountain men” or “immortals” (hsien) are pictured as feathered, like birds, or as floating through the air on soaring beasts. The German legend of Lohengrin, the swan knight, and the tales, told wherever shamanism has flourished, of the swan maiden, are likewise evidence of the force of the image of the bird as an adequate sign of spiritual power. And shall we not think, also, of the dove that descended upon Mary, and swan that begot Helen of Troy? In many lands the soul has been pictured as a bird, and birds commonly are spiritual messengers. Angels are but modified birds. But the bird of the shaman is one of particular character and power, endowing him with an ability to fly in trance beyond the bounds of life, and yet return.

Something of the world in which these wonder-workers move and dwell may be gathered from the legend of the Yakut shaman Aadja. His fabulous triple-phased biography commences with a tale of two brothers, whose parents had died when they were very young; and when the elder was thirty and the younger twenty, the latter married. “In the same year,” we then are told,

a red piebald stallion foal was born, and the signs all pointed to this foal’s becoming a beautiful steed. But that same fall the younger of the two brothers — the one who had married — fell sick and died. And although he lay there dead, he could hear everything that was said around him. He felt as though he had fallen asleep. He could neither move a limb nor speak, yet could distinctly hear them making his coffin and digging his grave. And so there he lay, as though alive, and he was unhappy that they should be getting together to bury him when he might very well have come back to life. They placed him in the coffin, put the coffin in the grave, and shoveled in the dirt.

He lay in the grave, and his soul, his heart, cried and sobbed. But suddenly, then, he heard that someone up there had begun to dig. He was glad to think that his elder brother, believing that he might still be alive, wished to disinter him. However, when at last the cover of his coffin was removed, he saw four black people whom he did not know. They took up his body and stood him upright on his coffin with his face turned toward his house. Through the window he could see a fire burning and smoke was coming from the chimney.

But then he heard, from somewhere, far in the depths of the earth, the bellowing of a bull. The bellowing came nearer, nearer; the earth began to tremble, and he was terribly afraid. From the bottom of the grave the bull emerged. It was completely black and its horns were close together. The animal took the man, sitting between its horns, and went down again through the opening from which it had just emerged. And they reached a place where there was a house, from within which there came the voice of what seemed to be an old man, who said: “Boys, it is true! Our little son has brought a man. Go out and relieve him of his load!” A number of black, withered men came hopping out, grabbed the arrival, carried him into the house and set him on the flat of the old man’s hand. The old man held him to estimate his weight; then said: “Take him back! His fate predestines him to be reborn up there!” Whereupon the bull again took him on its horns, bore him back along the old way, and set him down where he had been before.

When the living corpse came to his senses, night had descended and it was dark. Shortly thereafter, a black raven appeared. It shoved its head between the man’s legs, lifted him, and flew with him directly upward. In the zenith he saw an opening. They went through this to a place where both the sun and moon were shining and the houses and barns were of iron. All the people up there had the heads of ravens, yet their bodies were like those of human beings. And there could be heard inside the largest house something like the voice of an old man: “Boys! Look! Our little son has brought us a man. Go out and bring him in!” A number of young men dashed out and, seizing the newcomer, bore him into the house, where they set him on the flat of the hand of a gray-haired old man, who first tested his weight and then said: “Boys, take him along and place him in the highest nest!”

For there was a great larch up there, whose size can hardly be compared to anything we know. Its top surely reached heaven. And on every branch there was a nest, as large as a haystack covered with snow. The young men laid their charge in the highest of these, and when they had set him down, there came flying a winged white reindeer, which settled on the nest, and its teats entering his mouth, he began to suck. There he lay three years. And the more he sucked from the reindeer the smaller his body became, until finally he was no bigger than a thimble. Thus reposing in his lofty nest, he one day heard the voice of the same old man, who now was saying to one of his seven raven-headed sons: “My boy, go down to the Middle World, seize a woman, and bring her back!” The son descended, and presently returned with a brown-faced woman by the hair. They were all delighted, and arranging for a celebration, danced. But the one lying in the nest then heard a voice that said: “Shut this woman in an iron barn, so that our son, who lives in the Middle World, may not come up and carry her away!”

They locked the woman in a barn, and from his nest, in a little while, the nestling heard the sound of a shaman drum coming up from the Middle World; also, the sound of a shaman’s song. These sounds gradually grew, coming nearer — nearer — till finally, from below, there appeared, in the exit-opening, a head, and from the nest could then be seen a man of moderate stature and nimble mien, with hair already gray. Hardly had he fully appeared, however, when pressing the drumstick, crosswise, to his forehead, he was immediately transformed into a bull with a single horn that grew forward from the middle of his forehead. The bull shattered with a single blow the door of the barn in which the woman was locked and galloped off with her, down, and away. [Note 34]

What is being witnessed here — the reader may need to be told — is the arrival in the upper world of an earthly shaman, coming to rescue the soul of a woman who has passed away. For sickness, according to a shamanistic theory, can be caused either by the entrance of an alien element into the body, as in Mr. Bridges’ account of the magic of the Ona (a little mouse, pebble, worm, or some less substantial shamanistic projectile), or by the departure of the soul from the body and its imprisonment in one of the spirit regions: above, below, or beyond the rim of the world. The shaman called to a sickbed must first decide, therefore, what sort of disease is to be treated. and if what is required is massage, purgative herbal treatment, or the sucking away of some intrusive element, he will set to work in appropriate style; but if the soul has flown his clairvoyant vision must discover its lurking place. Then, riding — as they say — on the sound of his drum, he must sail away, on the wings of trance, to whatever spiritual realm may harbor the soul in question, overwhelm the guardians of that celestial, infernal, or tramontane place, and work swiftly his shamanistic deed of rescue. This latter is the classic shamanistic miracle and, particularly when the patient is already dead, it is an act requiring the greatest physical stamina and spiritual courage.

We shall presently view these affairs from a terrestrial standpoint, but for the present, let us return to the celestial region of our tale. A master shaman has arrived, transformed himself into a bull, shattered the bolts of an iron storage house, and galloped away with his prize, the soul of a woman whom the gods had thought to let die.

Following him, there went up cries and shouts, laments and mourning, and the son of the old man went down again to the Middle World. He returned with another, a white-faced woman, who was first transformed into a little insect and then perfectly hidden in the main, or middle, structural pole of the yurt; but soon again, the drum and song of a shaman could be heard. And this time, again, the one who arrived discovered his patient. He broke the pole in which she was hidden and carried her off.

Whereupon the son of the old man went his way a third time, returning with the same white-faced woman as before. But now the raven-headed spirit-people in the upper world made better arrangements for her protection. They set fire to a pile of wood at the exit hole, took glowing brands in their hands, and stood about the aperture, alert and waiting. Then, when the shaman appeared, they struck him with the firebrands and drove him back to the earth.

At last, the little watcher in the nest, at the end of his three years, once again heard the voice of the old man. “His hears are up,” the voice said. “Throw our child down to the Middle Earth. He is to go into a woman, to be born. And with the name, Shaman Aadja, which we have given him, he shall become famous: no one shall take this name in vain in the holy month!”

Intoning songs and blessings, the seven hurled him down to the Middle World, where he immediately lost consciousness and could not recall by what means he had come to be where he was. It was only when he was five that this recollection returned — and then he knew how he had been born before; how he had lived on the earth; and how he had been born above and there had seen with his own eyes the arrival of a shaman.

Seven years after his new birth he was seized by the spirits, forced to sing, and cut to pieces. At eight he began to shamanize and to perform the ritual dance. At nine he was already famous. And at twelve he was a great shaman.

It turned out that he had come into the world this time, fifteen versts [about ten miles] from the place of his former residence. and when he paid a visit to his former brother he found that his wife had married again and that the colorful stallion foal, born the year of his death, was now a famous steed. But his relatives failed to recognize him and he told them nothing. One summer day, however, when a man of property was celebrating the so-called Isyach Festival — the blessing of the sacred kumiss [an intoxicant fermented or distilled from mare's milk] — which is accompanied by a ritual called the Lifting Up of the Soul of the Horse, the young shaman there met the same shaman whom he had seen entering the Upper World while he had been lying in his nest. the older man immediately recognized him and said in a voice loud enough for others to hear: “When I cone was helping another shaman recover the soul of a sick woman, I saw you in the nest on the ninth, the uppermost, bough, sucking the teats of your animal mother. You were looking out of the nest.” and the younger shaman, Aadja, hearing these words, immediately became furious. “Why do you bring out before everybody the secret of my birth?” he asked. To which the other answered: “If you are planning evil against me, destroy me, eat me! I formerly was nurtured on the eighth bough of the same larch on which you were nurtured. I am to be born again and nurtured by the black Raven, Chara-Suorun.”

“And they say,” concluded the Yakut narrator, Popov Ivan, “that the young shaman, that same night, killed the elder. The shaman spirits swallowed him and thus committed him to death — and no one saw. — This ancient tale was told to me by a very old man.” [Note 35]

Spirits initiate the shamans of Australia in a cave; those of Siberia in a tree. Yet do we doubt that the sense of the two experiences is the same? In Siberia the shaman’s flesh is eaten and restored; in Australia his intestines are removed and replaced by quartz crystals. But are these not two versions of the same event? We note that in both cases two inductions are required: one by the spirits; one by living masters. But these two are characteristic of shamanism wherever it appears. In the various provinces the visions differ, likewise the techniques of ecstasy and magic traditionally taught; for the cultural patterns through which the shamanistic crisis moves and is realized have local histories and are locally conditioned. Yet the morphology of the crisis (it can no longer be doubted) remains the same wherever the shamanistic vocation has been experienced and cultivated.

The main point that has here been so vividly illustrated is that in the phenomenology of mythology and religion two factors are to be distinguished: the non-historical and the historical. In the religious lives of the “tough minded,” too busy, or simply untalented majority of mankind, the historical factor preponderates. The whole reach of their experience is in the local, public domain and can be historically studied. In the spiritual crises and realizations of the “tender minded” personalities with mystical proclivities, however, it is the non-historical factor that preponderates, and for them the imagery of the local tradition — no matter how highly developed it may be — is merely a vehicle, more or less adequate, to render an experience sprung from beyond its reach, as an immediate impact. For, in the final analysis, the religious experience is psychological and in the deepest sense spontaneous; it moves within, and is helped, or hindered, by historical circumstance, but is to such a degree constant for mankind that we may jump from Hudson Bay to Australia, Tierra del Fuego to Lake Baikal, and find ourselves well at home.