Chapter 8

The Paleolithic Caves

I. The Shamans of the Great Hunt

It is a profoundly moving human experience to visit the vast underground natural temples of the paleolithic hunters that abound in the beautiful region of the Dordogne, in southern France. One drives over the highways of the most recent period of man’s self-transformation so comfortable that even when one tries very hard to imagine what human life must have been during the closing millenniums of the Ice Age- — when sturdy tribesmen, not yet possessing even the bow and arrow, ran down and slaughtered with pointed sticks and chipped stones the musk ox, reindeer, woolly rhinoceros, and mammoth that ranged in this region over a frozen arctic tundra — the contrast of that fabulous vision of the past with the gentle humanity of the present is so great that the likelihood of its ever having actually existed on this earth seems remote indeed. One has perhaps paused on the way southward from Paris at the cathedral of Chartres, where the sculptured portals and glowing twelfth-and thirteenth-century stained glass bear into the present the iconography of the remote Middle Ages. Or perhaps one has come around by way of the cities of the Rhone — Avignon, Orange, Nimes, and Arles — -where temples, aqueducts, and colosseums in a totally different style, of the most durably cemented brick, testify to a period of European civilization older than that of cathedrals: that of Rome, two thousand years ago, when Ovid was composing his mythological history of the world, the Metamorphoses, and Christ, a Roman subject, was born in Bethlehem — according to tradition, in a cave associated by the local pagans with the mythological birth of their annually sacrificed-and resurrected deity Adonis. One is not prepared in any way by such touristic, literary, and archaeological experiences of the comparatively recent past, however, for the great leap, the real leap backward that the mind and heart must take, and do take, in the sacred caverns of the Dordogne.

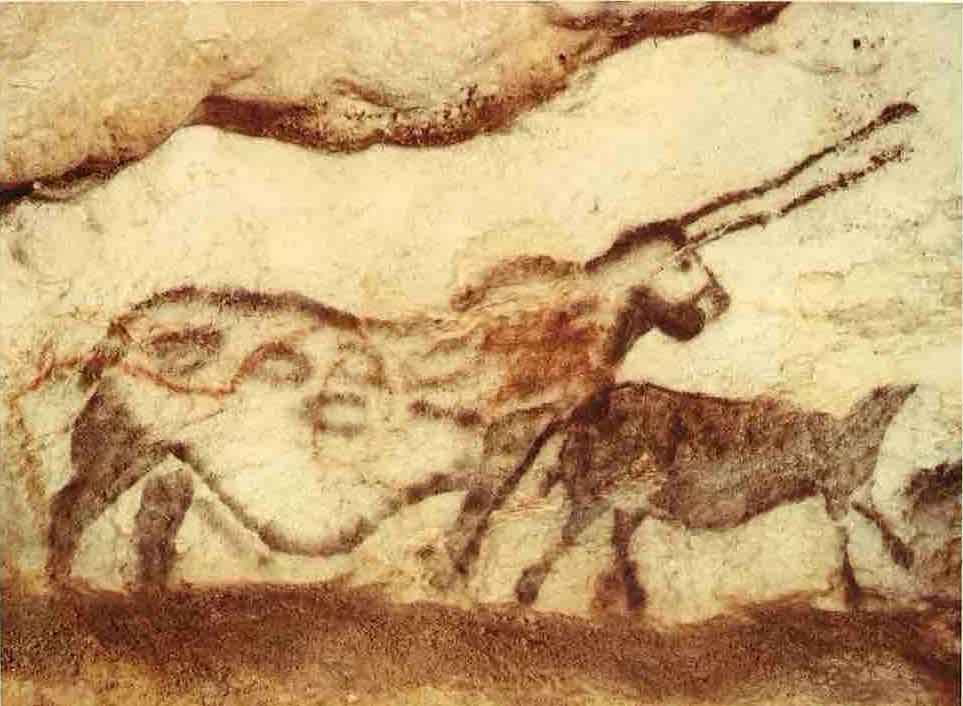

In the vast, multi-chambered hunting-age sanctuary of Lascaux — which has been termed “the Sistine Chapel of the paleolithic” — an experience of divinity has been made manifest, not, as at Chartres or in the Vatican, in human (anthropomorphic) figurations, but in animal (theriomorphic). Overhead, on the domed ceilings, are wondrous leaping bulls, and the rough walls abound in animal scenes that transmute the huge grotto into the vision of a teaming happy hunting ground: a herd of stags, apparently swimming a stream; droves of trotting ponies of a chunky, woolly sort, their females pregnant, full of movement and life; bisons of a kind that has been extinct in Europe for thousands of years. And among these magnificent herds there is one very curious, arresting figure: and animal form such as cannot have lived in the world even in the paleolithic age. Two long, straight horns point directly froward from its head, like the antennae of an insect or a pair of poised banderillas; and the gravid belly hangs nearly to the ground. It is a wizard-beast, the dominant manifestation of this whole miraculous vision. [Note 1]

Figure 13. The wizard-beast of Lascaux

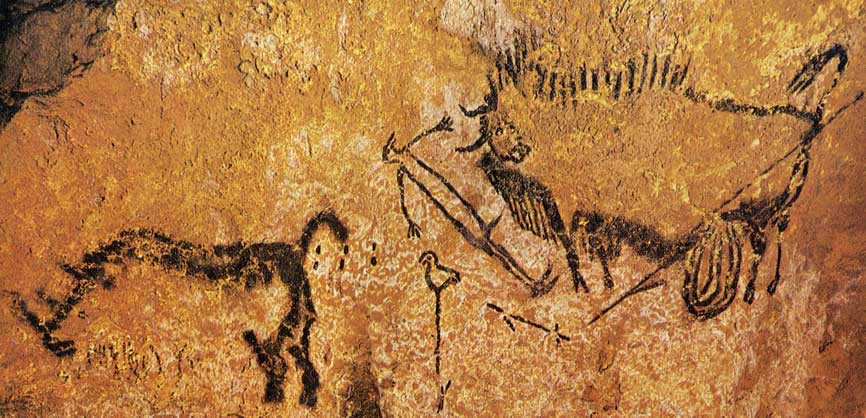

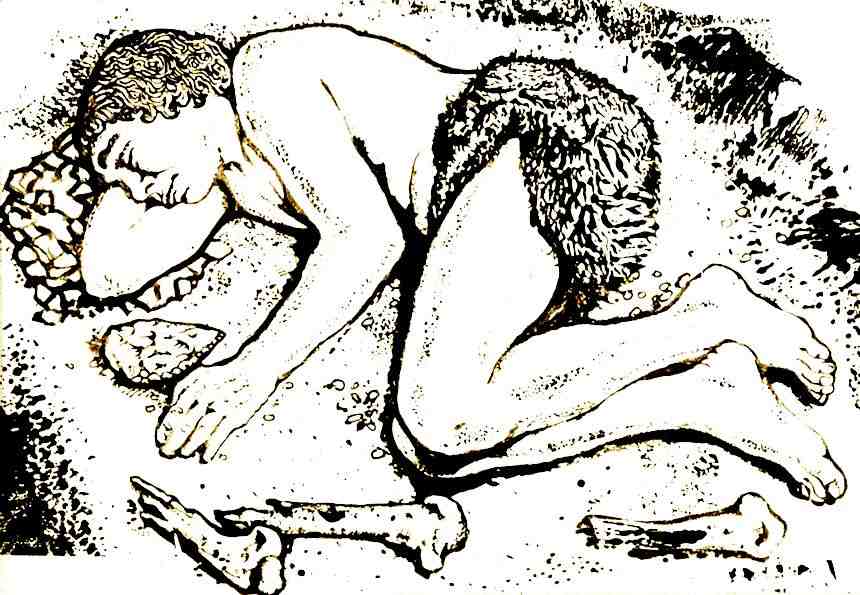

Moreover, there is another uncanny painting, even more suggestive of the mystery of this Stone age cathedral of hunting magic, at the bottom of a deep natural shaft or crypt, below the main level of the floor of the cave — a most difficult and awkward place to reach. Down there a large bison bull, eviscerated by a spear that has transfixed its anus and emerged through its sexual organ, stands before a prostrate man. The latter (the only crudely drawn figure, and the only human figure in the cave) is rapt in a shamanistic trance. He wears a bird mask; his phallus, erect, is pointing at the pierced bull; a throwing-stick lies on the ground at his feet; and beside him stands a wand or staff, bearing on its tip the image of a bird. And then, behind this prostrate shaman, is a large rhinoceros, apparently defecating as it walks away. [Note 2]

Figure 14. Figures in the crypt of Lascaux

There has been a good deal of discussion of this painting among the scholars, and the usual suggestion is that it may represent the scene of a hunting accident. No less an authority that the Abbé Breuil himself has supported this opinion, suggesting that the rhino may have been the cause of the disaster. [Note 3] It seems to me certain, however, that, in a cave where the pictures are magical and consequently were expected to bring to pass such situations as they represent, a scene of disaster would not have been placed in the crypt, the holy of holies. The man wears a bird mask and has birdlike instead of human hands. He is certainly a shaman, the bird costume and bird transformation being characteristic, as we have already seen, of the lore of shamanism to this day throughout Siberia and North America. Furthermore, in our Polynesian story of Maui and the monster eel we have learned something of the power of a magician’s phallus; and there is still practiced in Australia a lethal phallic rite of magic known as the “pointing bone,” one variety of which has been described by Géza Róheim, who writes:

Figure 15. Ceremonial mask: the horns are pointing sticks. After

Spencer and Gillen.

Black or hostile magic is predominantly phallic in Australia….If a man has been “boned.” his dream will show it. First he sees a crack, an opening in the ground, and then two or three men walking toward him within the opening. When they are near they draw a bone out of their own body. It comes from the flesh between the scrotum and the rectum. The sorcerer, before he actually “bones” his victim, makes him fall asleep by strewing in the air some semen or excrement which he has taken from his own penis or rectum. The man who uses the bone holds it under his penis, as if a second penis were protruding from him.

The Pindupi refer to black magic in general as erati, and a special type of described as kujur-punganyi (“bad-make”). Several men hold a string or pointing bone with both hands and, bending down, point backward, passing the magical bone just beside the penis. The victim is asleep, and the bone goes straight into his scrotum.

Figure 16. Australians in ceremonial attire with pointing- stick

horns. After Spencer and Gillen.

“Women also make evil magic,” Dr. Róheim continues, “through the agency of their imaginary penis. Luritja women cut their pubic hair and make thereof a long string. They take a kangaroo bone and draw blood from their vagina. The string becomes a snake which penetrates into the heart of their victims.” [Note 4] A further example comes from the women of the Pindupi tribe. “They cut the hair from their pubes and make a string. Then they send the string from one woman to another till it gets to the medicine woman. First she dances with the string (tultujananyl) and then she swallows it. In her stomach it is transformed into a snake. Then she vomits it and puts it into water. In the water the snake grows till it is wanapu puntu (‘big dragon’). The dragon undergoes another transformation, becoming a long cloud flying in the air with many women seated on it. The cloud becomes a snake again, it catches the woman’s soul while she is asleep.” [Note 5]

These examples suffice to suggest a plausible symbolic context for the pointing penis of the prostrate shaman of Lascaux — as well as for the defecation of the passing rhino, who may well be the shaman’s animal familiar. The position of the lance, furthermore, piercing the anus of the bull and emerging at the penis, spills the bowels from the area between — which is precisely the region effected by the “pointing bone” of the Australians. And finally it should be noted that the curious horns of the weird wizard beast in the upper chamber of the great cave, among the wonderful animals of the happy hunting ground, are exactly the same in form as the pointing sticks worn in the manner of horns by the performers in many of the Australian ceremonies of the men’s dancing ground. [Note 6]

Frobenius in North Africa, years before the discovery of Lascaux in 1940, noted three late paleolithic wall paintings that bear comparison with that in the crypt of Lascaux. One, from the face of a rock wall at Ksar Amar, in the Sahara-Atlas Mountains, shows a man with upraised arms before a buffalo; the second, from Fezzan, in southwest Libya, shows a couple dancing before a bull (two more dancing couples have been added in a later style); and a third, from the Nubian desert, shows three figures with upraised arms before a great ram. “It is to be noted,” writes Frobenius, “that in almost all pictures of this kind the representation of the animals has been carried out with great care, while the human figures are exceptionally sketchy.” But his observation holds true for the picture at Lascaux as well as for those that Frobenius had seen. “I think that what is shown in these pictures is on no account a ceremony,” states Frobenius; “for we have pictures of similar postures of adoration before elephants an giraffes. It is much more likely that, as in the Luebo Pygmy rite and rock pictures in general, what was undertaken was a consecration of the animal, effected not through any real confrontation of man and beast but by depiction of a concept in the mind.” [Note 7]

Adding up the evidence of the Pygmy rite, the paleolithic North African pictures, the concepts of the willing victim, animal master, ritual of the returned blood, magic of the pointing bone, and signs of shaman power on the sketchily rendered human figure, we can surely say that we know, in general, what the function of the Lascaux picture must have been, and why, of all in the cave, this is the one in the holy of holies.

The prostrate figure with the bird’s head and the curious questing beast of the upper cave, furthermore, are by no means the only evidences of the presence and importance of shamans in the paleolithic period of the great caves. In Lascaux itself there is a third figure, which the Abbé Breuil has compared to an African practitioner of magic. [Note 8] Indeed, no less than fifty-five figures of the kind have been identified among the teeming herds and grazing beasts of the various caves. These make it practically certain that in that remote period of our species the arts of the wizard, shaman, or magician were already well developed. In fact, the paintings themselves clearly were an adjunct of those arts, perhaps even the central sacrament; for it is certain that they were associated with he magic of the hunt, and that, in the spirit of that dreamlike principle of mystic participation — or, to use Piaget’s term, “indissociation” — which we have already discussed, their appearance on the walls amounted to conjuration of the timeless principle, essence, noumenal image, or idea of the herd into the sanctuary, where it might be acted upon by a rite.

A number of the animals are shown with darts in their sides or as though struck by boomerangs and clubs. Others, engraved on softer walls, are actually pitted with the holes made by javelins that must have been hurled at them with force. [Note 9] One thinks of the wax images of popular witchcraft, into which a name is conjured, and which then are pierced by needles or set to melt by a fire, so that the person may die.

It is also interesting to note that in most of the caves the animals are inscribed one on top of the other, with no regard for aesthetic effect. Obviously the aim was not art, as we understand it, but magic. And for reasons that we now cannot guess, the necromantic pictures were thought to be effective only in certain caves and in certain parts of those caves. They were renewed there, year after year, for hundreds of centuries. And without exception these magical spots occur far from the natural entrances of the grottos, deep within the dark, wandering, chill corridors and vast chambers; so that before reaching them one has to experience the full force of the mystery of the cave itself. Some of the labyrinths are more than half a mile in depth; all abound in deceptive and blind passages, and dangerous, sudden drops. Their absolute, cosmic dark, their unmeasured inner reaches, and their timeless remoteness from every concern and requirement of the normal, waking field of human consciousness can be felt even today — when the light of the guide goes out. The senses, suddenly, are wiped out; the millenniums drop away; and the mind is stilled in a recognition of the mystery beyond thought that asks for no comment and was always known (and feared) though never quite so solidly experienced before. And then, suddenly, a surprise, a visual shock, a never-to-be-forgotten imprint — as follows.

Let us enter the great system of initiatory passages and chambers, discovered a few before the outbreak of the First World War, sixty feet below the surface soil of the property of Count Henri Begouen and his three sons, at Montesquieu-Avantes (Ariège), in the Pyrenees. The count has named the labyrinth “Trois-Frères” (The Three Brothers), in honor of his boys, who found it. The corridors, drops, ascents, and vast halls contain some four or five hundred rock paintings and engravings, reproductions of many of which have not yet been published. But the patient work, year after year, of the Abbé Breuil, tracing, deciphering, and disentangling the figures, interpreting and photographing them, has already brought forth such a gallery that we may think of this cave as the richest single treasury of clues to the ritual experience and mythological lore of the late paleolithic period yet broached. It is cut off by a fall of rock underground from the adjoining grotto of Tuc d’Audoubert, whose sanctuary of the bull and cow of the buffalo dance we have already described. Tuc d’ Audoubert the count and his sons had discovered only two years before they entered the Alice’s Wonderland of Trois-Frères; and these two underground systems together, comprising at least a mile of labyrinthine ways, must have constituted, in the very long period of their use, one of the most important centers of magic and religion- — if not, indeed, the greatest — in the world. The period of their use, by the way, was at least some twenty thousand years.

The count and his sons, on July 20, 1914, were on their way across a broad meadow to pay a visit to the cave that they had discovered two years before, when they sought the shade of a tree, to rest from the heat; and a passing peasant, noticing their distress, suggested that they should go to the trou souffleur, where a cool wind came out of the ground even on the hottest day. With caves in mind, they followed his direction and found the “blow hole” behind a clump of bushes. The boys enlarged it, and one descended, tied to a rope that they had brought for their other adventure. Down, down he went, and some sixty feet were paid out before he stopped. He had brought a ball of twine, which he let out behind him, like Theseus in the labyrinth of the Minotaur, and a miner’s lamp to illuminate the corridors, which had not been entered for more than ten thousand years. His father and two brothers, waiting, became nervous when he had been gone for over an hour; but then there was a tug at the rope and they hauled him up, bursting with excitement. “A completely new cave! With hundreds of pictures!” he told them. However, the war came within a month, and it was not until 1918 that the exploration of the cave could be completed and the Abbé Breuil invited to commence his study. [Note 10]

“The ground is damp and slimy,” wrote Dr. Herbert Kühn, describing his visit to the cave in the summer of 1926;

we have to be very careful not to slip off the rocky way. It goes up and down, then comes a very narrow passage about ten yards long through which you have to creep on all fours. And then again there come great halls and more narrow passages. In one large gallery are a lot of red and black dots, just these dots.

How magnificent the stalactites are! The soft drop of the water can be heard, dripping from the ceiling. There is now other sound and nothing moves….The silence is eerie….The gallery is large and long and then there comes a very low tunnel. We placed our lamp on the ground and pushed it into the hole. Louis (the count’s eldest son) went ahead, then Professor van Giffen (of Groningen, Holland), next Rita (Mrs. Kühn), and finally myself. The tunnel is not much broader than my shoulders, nor higher. I can hear the others before me groaning and see how very slowly their lamps push on. With our arms pressed close to our sides we wriggle forward on our stomachs, like snakes. The passage, in places, is hardly a foot high, so that you have to lay your face right on the earth. I felt as though I were creeping through a coffin. You cannot lift your head; you cannot breathe. And then, finally, the furrow becomes a slightly higher. One can at last rest on one’s forearms. But not for long; the way again grows narrow. And so, yard by yard, one struggles on: some forty-odd yards in all. Nobody talks. The lamps are inched along and we push after. I hear the others groaning, my own heat is pounding, and it is difficult to breathe. It is terrible to have the roof so close to one’s head. And it is very hard: I bump it, time and gain. Will this thing never end? Then, suddenly, we are through, and everybody breathes. It is like a redemption.

The hall in which we are now standing is gigantic. We let the light of the lamps run along the ceiling and walls: a majestic room — and there, finally, are the pictures. From top to bottom a whole wall is covered with engravings. The surface had been worked with tools of stone, and there we see marshaled the beasts that lived at that time in southern France: the mammoth, rhinoceros, bison, wild horse, bear, wild ass, reindeer, wolverine, musk ox; also, the smaller animals appear: snowy owls, hares, and fish. And one sees darts everywhere, flying at the game. Several pictures of bears attract us in particular; for they have holes where the images were struck and blood is shown spouting from their mouths. Truly a picture of the hunt: the picture of the magic of the hunt! [Note 11]

The Abbé Breuil has published a beautiful series of tracings and photographs from this important sanctuary. [Note 12] The style is everywhere firm and full of life — with a spirit, as Professor Kühn has remarked, comparable to the best Impressionist sketches. Actually and most amazingly (and, of course, this was one of the features that made the discovery of this art so momentous) they seem very much closer to us than the hieratic, stiffly stylized masterworks of archaic Egypt and Mesopotamia, which are so much closer to us in time.

Figure 17. The Sorcerer of Trois FrèresIn this awesome

subterranean chamber of Trois-Frères the beasts are not painted on

the walls, but engraved — fixing for millenniums the momentary

turns, leaps, and flashes of the animal kingdom in a teeming tumult

of eternal life. And above them all, predominant — at the far end

of the sanctuary, some fifteen feet above the level of the floor,

in a craggy, rocky apse — watching, peering at the visitor with

penetrating eyes, is the now famous “Sorcerer of Trois-Frères.”

Presiding impressively over the animals collected there in

incredible numbers, he is poised in profile in a dancing movement

that is similar, as the Abbé Breuil has suggested, to a step in the

cakewalk; but the antlered head is turned to face the room. The

pricked ears are those of a stag; the round eyes suggest an owl;

the full beard descending to the deep animal chest is that of a

man, as are likewise the dancing legs; the apparition has the bushy

tail of a wolf or wild horse, and the position of the prominent

sexual organ, placed beneath the tail, is that of the feline

species — perhaps a lion. The hands are the paws of a bear. The

figure is two and a half feet high, fifteen inches across. “An

eerie, thrilling picture,” wrote Professor Kühn. [Note 13] Moreover, it is the only picture

in the whole sanctuary bearing paint — black paint — which gives it

an accent stronger than all the rest.

But who or what is this man — if man he is — whose image is now impressed upon us in a way that we shall not forget?

The Count Begouen and the Abbé Breuil first supposed it to represent a “sorcerer,” but the Abbé now believes it to be the presiding “god” or “spirit” controlling the hunting expeditions and the multiplication of game. [Note 14] Professor Kühn suggests the artist-magician himself. [Note 15] To the anthropologically practiced eye of Professor Carleton S. Coon of the University of Pennsylvania, on the other hand, “this is just a man ready to hunt deer. Perhaps he is practicing. Perhaps he is trying to induce the spirit of the forest that controls the deer to make a fat buck walk his way.” And Professor Coon concludes: “Whatever the artist’s overt motive in painting it, he did it because he felt a creative urge and liked to express himself, as every artist does, whether he is painting a bison on the wall of a cave or a mural in the main hall of a bank.” [Note 16]

There must be some scientific way of supporting the romantic hypothesis of a man crawling on his belly through a tube forty or fifty yards long to relieve a creative urge; otherwise, I am sure, the professor would not have made this suggestion. But for myself, I prefer the simpler course of assuming that this chamber, and the whole cave, was an important center of hunting magic; that these pictures served a magical purpose; that the people in charge here must have been high-ranking highly skilled magicians (powerful by repute, at least, if not in actual fact); and that whatever was done in this cave had as little to do with an urge to self-expression as the activity of the Pope in Rome celebrating a Pontifical Mass.

Between the two guesses of the Abbé Breuil, however, it is extremely difficult to decide — but perhaps not as important to make a choice as a modern man might suppose: for if the vivid, unforgettable lord of the animals in the hunters’ sanctuary of Trois-Frères is a god, then he is certainly a god of sorcerers, and if a sorcerer, he is one who has donned the costume of a god; and, as we know, and see amply illustrated in the ritual lore of modern savages, when the sacred regalia has been assumed the individual has become an epiphany of the divine being itself. He is taboo. He is a conduit of divine power. He does not merely represent the god, he is the god; he is a manifestation of the god, not a representation.

But a picture, too, is such a manifestation. And so, perhaps, the most likely interpretation is, after all, the second by the Abbé Breuil, namely, that the so-called “Sorcerer of Trois-Frères” is actually a god, the manifestation of a god — who, indeed, may also have been embodied in some of the shamans themselves, during the course of the rites, but here is embodied for us, forever, in this wonderful icon.

First among the features of the great caves that are of paramount importance to our study is the fact that these deep, labyrinthine grottos were not dwellings but sanctuaries, comparable in function to the men’s dancing grounds of the Aranda; and there is evidence enough to assure us that they were used for similar purposes: the boys’ puberty rites and the magical increase of the game. And just as every shrine and ceremony in the ancient world, as well as among the primitive tribes whose customs we know, had its origin legend, so must these sanctuaries of the Old Stone Age have had theirs. The enigmatic figures painted into the crypts and deepest recesses of the caves almost certainly hold in their silence the myths of the ultimate source of the magical efficacy of these magnificent shrines.

The dwellings of the people, on the other hand, were either in shallow caves and under ledges, or out on the open plains, in various kinds of shelter. A number of the paintings suggest the forms of their shacks or houses, while under many ledges abundant remains have been found of Old stone age life. In fact, in the beautiful valleys of the Dordogne people are dwelling under those same ledges to this day. They are great ledges, left by the wash of mighty glacial rivers; and the same rivers now being much smaller and lower than they were, they have left a beautiful grassy area between their present banks and the tall cliffs into which the ledges curve. One has to climb a little to reach the comfortable French homes that nestle against the overhanging walls. And just beneath the earth of these modern homes there is to be found a stratum of Gallo-Roman remains, from the period of Vercingetorix and Julius Caesar; below that, remains of the earlier Gallic culture world; still lower, the neolithic of c. 2500-1000 b.c. — and then the paleolithic, level after level: Azilian, Magdalenien, Solutrean, Aurignacian, even Mousterian; some fifty thousand years of human living in one amazing cross-sectional view. On the topmost level you may find a broken bicycle chain; on the bottom a cave-bear tooth two inches long. And the concierge who is showing you the cut is herself living in a house with the slid rock of the cliff for its back wall, and she will tell you what the advantages are of a building with such a wall: it is cool in summer and warm in winter. The rock, sheer mother rock, affords good protection. Meanwhile, out in front, there is to be seen the graceful sweep of grass down to the lovely river, and one cannot but recognize and feel that for millenniums this has been a fine place for the raising of children. Paleolithic men hunted for their food instead of growing it, and they walked or ran from place to place instead of bicycling or riding in a car. But otherwise? They had their youngsters, and their wives sewed clothes — not of cloth, but of leather. The men and their workshops for the chipping of flint, and their men’s clubs in the their secret caves. They were living, in the main, just about as people do now. And so it has been for some fifty thousand years. The tick of time in such a situation does not sound quite as loudly as it once did.

II. Our Lady of the Mammoths

Now whereas in the mural paintings of the paleolithic caves animal forms preponderate, the chief subject of interest among the sculptured remains of the same period was the human female; and whereas the comparatively rare figures of men appearing among the painted animals are masked or otherwise modified in such a way as to suggest mythological beings and magical enterprises, the female figurines, carved in bone, stone, or mammoth ivory, are nude, and simply standing. Many are extremely obese, and of these some are radically stylized in a remarkably “modern” manner to give dramatic — and, no doubt, symbolically intended — emphasis to the great loins, the pubic triangle, and the nourishing breasts. In contrast to the male forms in the paintings, they are never masked or otherwise modified to suggest animals, while of the hundred and thirty-odd that have been found, only two appear to be clothed in anything like a shamanistic attire. The others simply are. Indeed, a few scholars have interpreted the bold little “Venuses” as paleolithic erotica. [Note 17] But since several have been found set up in shrines, it is now certain that they were the objects of a cult. Without exception, they lack feet, for they were stuck in the ground upright; a few have been discovered actually in situ. And so we can say that in the paleolithic period, just as in the much later age of the early agricultural societies of the Near East, the female body was experienced in its own character as a focus of divine force, and a system of rites was dedicated to its mystery.

Were these the rites, however, of a women’s cult, of a men’s cult, or of both? Were they complementary to, incompatible with, or simply dissociated from, the rites of the grottos? Were they derived from the same province or stratum of Old Stone Age life as the rituals of the caves, or did they represent some totally alien system?

Leo Frobenius was the first, I believe, to suggest — on the basis of his fundamental distinction between the provinces of the tropical forest, where every kind of wood abounds and the art of wood sculpture flourishes in strength to this day, and the temperate steppe and desert lands. where the chief material is stone and the normal art that of lines engraved or scratched on two-dimensional surfaces — that the Aurignacian glyptic art of the figurines must have received its original impulse from the wood-and ivory- carving areas of the south. [Note 18] Professor Menghin too, in his World History of the Stone Age, [Note 19] sees a probable relationship between these female figurines and the realm of the tropical planters. They represent, he suggests, that same mother-goddess who was to become so conspicuous in the later agricultural civilizations of the Near East and has been everywhere celebrated as the Magna Mater and Mother Earth. Should it be shown that there is indeed ground for such suggestions, then the beginnings of that mythological system of the planting world at which we glanced in our study of the sacrifice of the maiden are of much greater age than any dating from the proto- or basal neolithic would allow, and we may perhaps think of these Aurignacian statuettes as a prelude or up-beat to the symphony of hymns that we have already heard, and shall hear again, to the great goddess.

But there is another approach to the same elementary idea, which does not invoke the ethnic ideology of the planters. For are mothers not mothers of the banks of the Yenisei as well as on the Congo? As Franz Hancar has pointed out in his article “On the Problem of the Venus Statuettes in the Eurasian Upper Paleolithic,” [Note 20] human figures of larch and aspen wood are carved to this day among the Siberian reindeer hunters — the Ostyaks, Yakuts, Goldi, etc. — to represent the ancestral point of origin of the whole people, and they are always female. The hut is entrusted to the little figure when its occupants leave for the hunt; and when they return they feed her with groats and fat, praying, “Help us to keep healthy! Help us to kill much game!” “The psychological background of the idea,” Dr. Hancar suggests, “derives from the feeling and recognition of woman, especially during her periods of pregnancy, as the center and source of an effective magical force.” [Note 21] “And from the point of view of the history of thought,” he then observes, “these Late Paleolithic Venus figurines come to us as the earliest detectable expression of that undying ritual idea which sees in Woman the embodiment of the beginning and continuance of life, as well as the symbol of the immortality of that earthly matter which is in itself without form, yet clothes all forms.” [Note 22]

There can be no doubt that in the very earliest ages of human history the magical force and wonder of the female was no less a marvel than the universe itself; and this gave to woman a prodigious power, which it has been one of the chief concerns of the masculine part of the population to break, control, and employ to its own ends. It is, in fact, most remarkable how many primitive hunting races have the legend of a still more primitive age than their own, in which the women were the sole possessors of the magical art. Among the Ona of Tierra del Fuego, for example, the idea is fundamental to the origin legend of the lodge or Hain of the men’s secret society. Here is Mr. Lucas Bridges’ summary of the legend:

In the days when all the forest was evergreen, before Kerrhprrh the parakeet painted the autumn leaves red with the color from his breast, before the giants Kwonyipe and Chashkilchesh wandered through the woods with their heads above the tree-tops; in the days when Krren (the sun) and Kreeh (the moon) walked the earth as man and wife, and many of the great sleeping mountains were human beings: in those far-off days witchcraft was known only to the women of Ona-land. They kept their own particular Lodge, which no man dared approach. The girls, as they neared womanhood, were instructed in the magic arts, learning how to bring sickness and even death to all those who displeased them.

The men lived in abject fear and subjection. Certainly they had bows and arrows with which to supply the camp with meat, yet, they asked, what use were such weapons against witchcraft and sickness? This tyranny of the women grew from bad to worse until it occurred to the men that a dead witch was less dangerous than a live one. They conspired together to kill off all the women; and there ensued a great massacre, from which not one woman escaped in human form.

Even the young girls only just beginning their studies in witchcraft were killed with the rest, so the men now found themselves without wives. For these they must wait until the little girls grew into women. Meanwhile the great question arose: How could men keep the upper hand now they had got it? One day, when these girl children reached maturity, they might band together and regain their old ascendancy. To forestall this, the men inaugurated a secret society of their own and banished for ever the woman’s Lodge in which so many wicked plots had been hatched against them. No woman was allowed to come near the Hain, under penalty of death. To make quite certain that its decree was respected by their womenfolk, the men invented a new branch of Ona demonology: a collection of strange beings — drawn partly from their own imaginations and partly from folk-lore and ancient legends — who would take visible shape by being impersonated by members of the Lodge and thus scare the women away from the secret councils of the Hain. It was given out that these creatures hated women, but were well-disposed towards men, even supplying them with mysterious food during the often protracted proceedings of the Lodge. Sometimes, however, these beings were short-tempered and hasty. Their irritability was manifested to the women of the encampment by the shouts and uncanny cries arising form the Hain, and , it might be, the scratched faces and bleeding noses with which the men returned home when some especially exciting session was over.

Most direful of the supernatural visitors to the Hain were the horned man and two fierce sisters….The name of the horned man was Halahachish or, more usually, Hachai. He came out of the lichen-covered rocks and was as gray in appearance as his lurking-place. The white sister was Halpen. She came from the white cumulus clouds and shared a terrible reputation for cruelty with her sister, Tanu, who came from the red clay.

A fourth monster of the Hain was Short. He was a much more frequent participator in Lodge proceedings than the other three. Like Hachai, he came from the gray rocks. His only garment was a whitish piece of parchment-like skin over his face and head. This had holes in it for eyes and mouth and was drawn tight round the head and tied behind. There were many Shorts, and more than one could be seen at the same time. There was a great variation in coloring and pattern of the make-up. One arm and the opposite leg might be white or red, with spots or stripes (or both) of the other color superimposed. The application to the body of gray down from young birds gave Short a certain resemblance to his lichen-covered haunts. Unlike Hachai, Halpen and Tanu, he was to be found far from the Hain and was sometimes seen by women when they were out in the woods gathering firewood or berries. On such occasions they would hasten home with the exciting news, for Short was said to be very dangerous to women and inclined to kill them. When he appeared near the encampment, the women would bolt for their shelters, where, together with their children, they would lie face downward on the ground, covering their heads with any loose garments they could lay their hands on.

Besides those four, there were many other creatures of the Hain, some of whom had not appeared, possibly, for a generation. There was, for instance, Kmantah, who was dressed in beech bark and was said to come out of, and return to, his mother Kualchink, the deciduous beech tree. Another was Kterrnen. He was small, very young and reputed to be the son of Short. He was highly painted and covered with patches of down; and was the only one of all the creatures of the Lodge to be kindly disposed towards the women, who were even allowed to look up when he passed.

“I wondered sometimes,” states Mr. Bridges, who was himself an initiated member of the Hain, “whether these strange appearances might be the remains of a dying religion, but came to the conclusion that this could not be so. There was no vestige of any legend to suggest that any of these creatures impersonated by the Indians had ever walked the earth in any form but fantasy.” [Note 23]

Among the Yahgans (or Yamana) too — the southern neighbors of the Ona, but a very different folk, much shorter in stature and devoted not to hunting guanaco in the hills but to fishing and sealing along the dangerous shores — there was the legend that formerly their women had ruled by witchcraft and cunning. “According to their story,” states Mr. Bridges, “it was not so very long ago that the men assumed control. This was apparently done by mutual consent; there is no indication of a wholesale massacre of the women such as took place — judging from that tribe’s mythology — among the Ona. There is, not far from Ushuaia, every sign of a once vast village where, it is said, a great gathering of natives took place. Such a concourse was never seen before or since, canoes arriving from the farthest frontiers of Yahgan-land. It was at that momentous conference that the Yahgan men took authority into their own hands.” And Mr. Bridges concludes: “This legend of leadership being wrested from the women, either by force or coercion, is too widely spread throughout the world to be lightly ignored.” [Note 24]

Among the Australians, as Spencer and Gillen have noted, [Note 25] “in past times the position of women in regard to their association with sacred objects and ceremonies was very different from that which they occupy at the present day.” At Emily Gap, one of the most important sacred spots of the Aranda, for example, there in a drawing on the rocks that is supposed to have sprung up spontaneously to mark the place where the altjeringa women of the mythological age adorned themselves with ceremonial paint and stood peering up, watching, while the men performed those ceremonies of animal increase (intichiuma) from which the women today are absolutely excluded. “One of the drawings is supposed to represent a woman leaning on her elbow against the rocks and gazing upwards.” [Note 26] Other observers, also, have noted evidences in Australia of an age when the role of women in the mythological lore and ceremonial life was more prominent than that accorded them today. Father E.F. Worms, of Broome, for example, has described a cluster of archaic petroglyphs in the northwestern desert, at a site in the upper Yule River area known as Mangulagura, “Woman Island,” where all the engravings are representations of women. From their prominent vulvas three lines proceed, which may represent magical emanations of some kind, and above them is a curving picture of the Rainbow Snake. [Note 27]

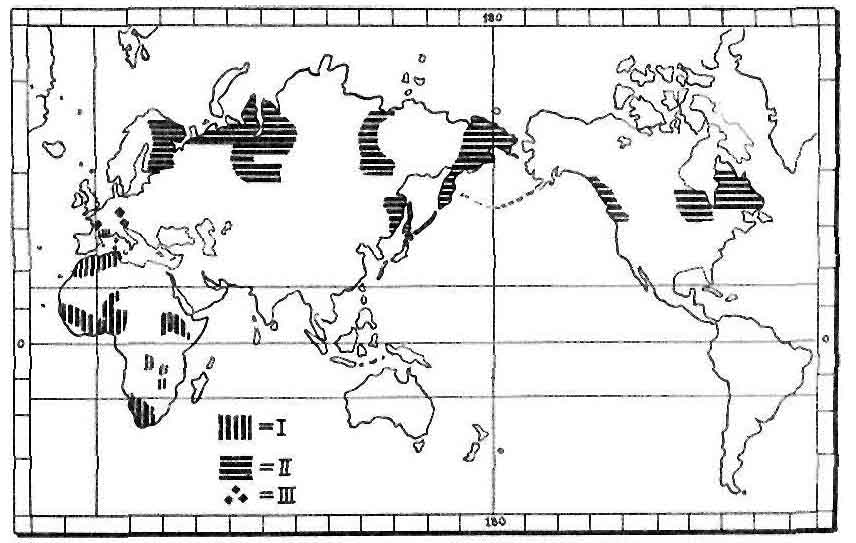

One is tempted to surmise that there may have taken place in the human past either some crisis of which these legends would be the widely distributed report, or a number of such crises in various parts of the world; and according to the view of the culture-historical school represented by the monumental, twelve-volume work of Father W. Schmidt on The Origin of the Idea of God, [Note 28] there is actually evidence enough to justify a historical hypothesis of this kind. Father Schmidt and his colleagues have found it necessary to distinguish three basic types or stages of primitive society. The first is that of the simplest peoples known to the science of ethnology: the little Yahgans (or Yamana) of the southernmost channels and coves of rugged Tierra del Fuego, a number of extremely primitive, scattered tribes of Patagonia and Central California, the Caribou Eskimo of northern Canada, the Pygmies of the Congo and of the Andaman Islands, and the Kurnai of Southeastern Australia. The ethnological circumstances of these humble hunting, fishing, and collecting peoples do not give rise to either a strong patriarchal or a strong matriarchal emphasis; rather, an essential equality prevails between the sexes, each performing its appropriate tasks without arrogating to itself any special privileges or peculiar rights to command. The ceremonies of initiation at puberty are not confined to the boys and men, nor separated into male and female rites, but are nearly identical for the two sexes. Nor do the rites involve any physical deformation or the communication of mystical secrets. They are simply concentrated courses of education for adolescents, to the end of making good fathers and mothers of the initiates. Special tribal or group interests do not stand in the foreground of the teaching, since the tribal feeling in such groups is not greatly developed — the typical social unit being merely a cluster of twenty to forty parents and children, whose main social problem is hardly more than that of living harmoniously together, gathering food enough to eat during the day, and inventing pleasant games together after dark.

The second stage or type of primitive society recognized by this culture-historical school of ethnology is that of the large, totemistic hunting groups, with their elaborately developed clan systems, age classes, and tribal traditions of ritual and myth. Examples of such peoples are abundant on the plains of North America and the pampas of South America, as well as in the deserts of Australia. Their rites of initiation, as we have seen, are secret. Women are excluded; physical mutilations and ordeals are carried sometimes to almost incredible extremes, and they culminate generally in circumcision. Moreover, there is considerable emphasis placed on the role and authority of the men, both in the religious and in the political organization of the symbolically articulated community. Not infrequently, the circumcision of the boys is matched by comparable operations on the girls (artificial or ceremonial defloration, enlargement of the vagina, removal of the labia minora, partial or complete clitoridectomy, etc.), but in such cases the two systems of ceremonial — the male and the female — are kept separate, and the women do not gain through their rites any social advantage over the men. On the contrary, there is a distinct one-sidedness in favor of the male in these highly organized hunting societies, the influence of the women being confined — when it exists at all — to the domestic sphere.

According to the hypothesis of Father Schmidt and his colleagues, the puberty initiations of this second stage or type of primitive society have stemmed from those of the first, with, however, a bias in favor of the males and therewith an emphasis on the sexual aspect of the rites and particularly on circumcision. A very different course of development is to be traced, however, in the sphere of the tropical gardening cultures, where a third type or stage of social organization matured that was almost completely antithetical to that of the hunting peoples. For in these areas it was the women, not the men, who enjoyed the magico-religious and social advantage, they having been the ones to effect the transition from plant-collecting to plant-cultivation. [Note 29] In the simple societies of the first sort, the males, in general, are the hunters and the women the collectors of roots, berries, grubs of various kinds, frogs, lizards, bugs, an other delicacies. Societies of the second type evolved in areas where an abundance of large game occasioned a herculean development of the dangerous art of the hunt; while those of type three took form where the chief sources of nutriment were the plants. Here it was the women who showed themselves supreme: they were not only the bearers of children but also the chief producers of food. By realizing that it was possible to cultivate, as well as to gather, vegetables, they had made the earth valuable and they became, consequently, its possessors. Thus they won both economic and social power and prestige, and the complex of the matriarchy took form.

The men, in societies of this third type, were within one jot of being completely superfluous, and if, as some authorities claim, [Note 30] they can have had no knowledge of the relationship of the sexual act to pregnancy and birth, we may well imagine the utter abyss of their inferiority complex. Small wonder, furthermore, if, in reaction, their revengeful imaginations ran amok and developed secret lodges and societies, the mysteries and terrors of which were directed primarily against the women! According to the view of Father Schmidt, the ceremonials of these secret lodges are to be distinguished radically from those of the hunting-tribe initiations, their psychological function being different and their history different too. Admission to them is through election and is generally limited: they are not for all. Moreover, they tend to be propagandistic, reaching beyond the local tribe, seeking friends and members among alien peoples, and thus bringing it about that, for example, in both West Africa and Melanesia the chapters of certain lodges are to be found dispersed among greatly differing tribes. As already noted, a particular stress is given in these secret men’s societies to a skull cult that is often associated with the headhunt. Ritual cannibalism and pederasty are commonly practiced, and there is a highly elaborated use made of symbolic drums and masks. Ironically (yet by no means illogically), the most prominent divinities of these lodges are frequently female, even the Supreme Being itself being imagined as a Great Mother; and in the mythology and ritual lore of this goddess a lunar imagery is developed — as we have also already seen.

In considering such extreme initiation rites among hunters as those of the Central Australians, which we reviewed briefly in Part One, Father Schmidt calls attention to the secondary influences that can readily be shown to have entered the hunting areas of Australia from the gardening cultures of Melanesia and New Guinea; and comparably, when dealing with Mr. Lucas Bridges’ friends, the Yahgans and Ona of Tierra del Fuego, he explains the Hain, with its anti-feminine antics, as an alien institution, ultimately derived, through Patagonia, from the planting cultures of the South American tropical zone.

“Whereas the aim of their puberty initiations,” he writes in his discussion of the primitive hunting tribes of Tierra del Fuego,

was that of turning boys and girls into competent human beings, parents, and tribal members — their teachings and examples being based on the firm foundation of a Supreme being, both powerful and good, reposing in eternity — the men’s festivals not only were addressed to an ignoble, and immoral means. The aim was to undo the harmonious state of equal privilege and mutual reliance of the two sexes that originally had prevailed in their simple society, supported by economic circumstance, and to establish through intimidation and the subjection of the women, a cruel ascendancy of the males. The means were Hallowe’en burlesques, in which the players themselves did not believe, and which, consequently, were lies and impostures from beginning to end. And the ill effects that issued from all this were not only disturbances of the social balance of the sexes, but also a coarsening and self-centering of the males, who were striving for such ends by such means.

The exoneration of their action, which the men felt called upon to advance in their myth, namely that it was the women who had done these things first and that, consequently, the performances of the men’s lodge were justified, was actually an indefensible plea; for there had never been any such practice of agriculture in their community as could have given rise to the matriarchal supremacy reported in the myth. The whole story must have been imported from some other region, where a matriarchy based on horticulture had incited a reaction of the males and their development of men’s societies, which then, together with their system of men’s festivals, were carried to Tierra del Fuego. [Note 31]

The mythological apologia offered by the men of the Ona tribe for their outrageous lodge was marvelous close, as the reader may have noted, to that attributed to Adam by the patriarchal Hebrews in their Book of Genesis; namely, that, if he had sinned, it was the woman who had done so first. And the angry Lord of Israel — conceived in a purely masculine form — is supposed to have allowed a certain value to this excuse; for he then promptly made the whole race of woman subject to the male. “I well greatly multiply your pain in childbearing,” the Lord God is declared to have announced; “in pain you shall bring forth children, yet your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.” [Note 32]

This curious mythological idea, and the still more curious fact that for nearly two thousand years it was accepted throughout the Western World as the absolutely dependable account of an event supposed to have taken place about a fortnight after the creation of the universe, poses forcefully the highly interesting question of the influence of consciously contrived, counterfeit mythologies and inflections of mythology upon the structure of human belief and the consequent course of civilization. We have already noted the role of chicanery in shamanism. It may well be that a good deal of what has been advertised as representing the will of “Old Man” actually is but the heritage of a lot of old men, and that the main idea has been not so much to honor God as to simplify life by keeping woman in the kitchen.

Some such flowery battle in the continuing war of the sexes, translated into and supported by mythology, must underlie the complete disappearance of the female figurines from the European scene at the close of the Aurignacian. We have already remarked that in the mural art of the men’s temple-caves, which developed during the Aurignacian and reached its height in the almost incredibly wonderful happy-hunting-ground visions of the Magdalenian age, animals preponderate and the human figures are male, costumed as shamans, whereas in the Aurignacian cult of the figurines, whatever its reference and function may have been, the central form was the female nude, with great emphasis placed on the sexual parts. Was the revolution the consequence of an invasion of some kind — a new race, or one of those missionizing “men’s society” movements of which Father Schmidt has written? Or was it the consequence of a natural transformation of the social conditions with a transfer of power and prestige naturally to the male?

The climate of Europe and the great sweep of plains to Lake Baikal was moist and extremely cold during the Aurignacian, when the vast icefields of the fourth glaciation (Würm), though in recession, still held a line at about the latitude of Oslo (60 degrees north). The landscape was arctic tundra, and the animals foraging upon it were the musk ox, woolly rhinoceros, reindeer, and woolly mammoth. The arctic fox, hare, wolverine and ptarmigan were also present. [Note 33] However, with the further retreat of the ice, the climate, though remaining cold, became dry, and steppe conditions began to preponderate over tundra. This brought, in addition to the animals just named, the great grazing herds of the bison, wild cattle, steppe horse, antelope, wild ass, and kiang. The alpine chamois, ibex, and argali sheep also challenged the masters of the hunt. [Note 34] As a result, the modes and conditions of human life greatly changed. In the earlier period of the mammoth, the hunting stations appear to have ben widely scattered but comparatively stationary; within the protection of the dwellings the force and value of the feminine part of the community had a sphere in which to make itself felt. In the later period of the great herds, however, a shift to a more continuously ranging style of nomadism took place, and this reduced the domestic role of woman largely to the packing, bearing, and unpacking of luggage, while the men developed that fine sense of their own superiority that always redounds to their advantage when the jobs to be done require more of the running-muscles than of the sitting-fat. In the western portions of the broad hunting range of which we have been speaking, this more mobile style of the hunt developed along with the mural art of the men’s temple-caves. Eastward, however, in the colder reaches of southern Russian and Siberia, the mammoth remained, and therewith also the little figurines of Our Lady of the Mammoth, until a much later day. And with this contrast in the historical development of the two areas during the late paleolithic, we have perhaps touched the first level of the profound psychological as well as cultural contrast of East and West.

We have already taken note of the Venus of Laussel and have suggested that the Blackfoot legend of the buffalo dance may be a remote outrider of the late Aurignacian tradition of which she is a representative. In her day the bison had already supplanted the mammoth as the main object of the hunt, but among the tribes for whom she was carved the naked female had apparently not yet been supplanted, in her magical role, by the costumed shaman. We have observed that in the same sanctuary of Laussel, in southern France, three other female forms were found (one, apparently, in the act of giving birth), as well as a number of representations of the female organs. The rock shelter, furthermore, was a habitable retreat. The cult involved was not that of the great, deep temple-caves; and the fact that most of the figures at the site were shattered to such a degree that they could not be reconstructed may point to an actual attack designed to break their power. Other examples have been found of such attacks on the magical objects of paleolithic camps; the suggestion is not fanciful in the least. But whether by some milder process of cultural transformation, or by such violence as the Ona legend of the massacre that broke up the age of woman’s magic would suggest, the fact remains that at the western pole of the broad paleolithic domain of the Great Hunt, which stretched form the Cantabrian hills of northern Spain to Lake Baikal in southeast Siberia, the earliest races of the species Homo sapiens of which we have any record made a shift from the vagina to the phallus in their magic, and therewith, perhaps too, from an essentially plant-oriented to a purely animal-oriented mythology.

The female figurines are the earliest examples of the “graven image” that we possess, and were, apparently, the first objects of worship of the species Homo sapiens; for on the level below theirs we break into the field of an earlier stage in the evolution of our species — that of Homo neanderthalensis, a short-legged, short-armed, barrel-chested brute, short-necked, chinless, and heavy browed, with highly arched, broad nose and protruding muzzle, who walked with bent knees on the outer edges of his feet. [Note 35] In contrast, the women represented in our figurines, for all their bulk, are definitely of the species Homo sapiens, and are such, indeed, as may well be met to this day, opening another box of candy, in Polynesia, Moscow, Timbuktu, or New York.

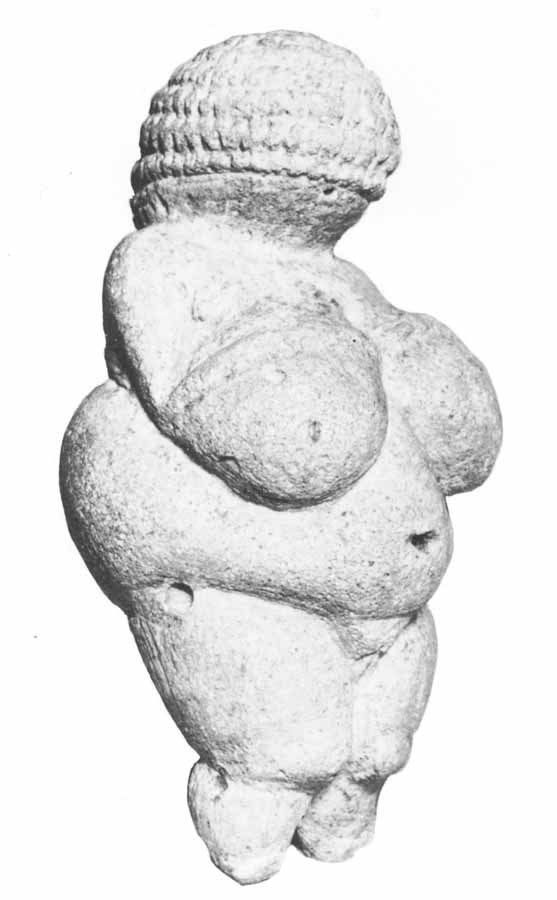

Figure 18. Venus of Willendorf]

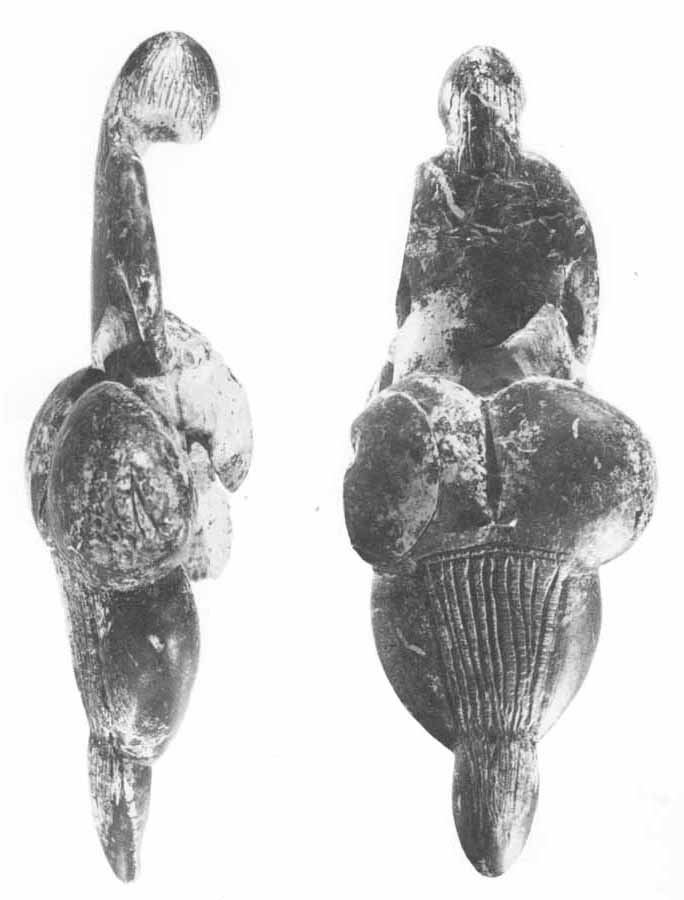

The celebrated Venus of Willendorf (Lower Austria) is an extremely corpulent little female, about 4 3/8" high, standing on pitifully inadequate legs, with her thin, ribbonlike arms resting lightly on ballooning breasts. An equally celebrated example of the subject is an elegantly carved, highly stylized figure from the Grottes de Grimaldi, near Menton (on the Mediterranean shore, about five miles west of Monaco), whose form suggests the modern work of Archipenko or Brancusi; while a fabulous little masterpiece in mammoth ivory, 5 3/4" high, from Lespugue, Haute-Garonne, still bolder in its stylization, presents a figure with trimly sloping shoulders but extravagant breasts reaching even to the groins. A second example from the Grottes de Grimaldi, again carved in the “modern” style, is both steatopygous and prominently pregnant. However, as already noted, not all the figurines are of the portly type. Some are little better than splinters of mammoth tusk with the signs of their feminine gender scratched upon them.

Figure 19. The Venus of Lespugue

An important discovery was made in 1930 in the Dnieper region, at a site known as Yeliseevici, on the right bank of the river Desna, between Bryansk and Mglin. It consisted of an accumulation of mammoth skulls arranged in the form of a circle, and among them a number of tusks, some plaques of mammoth ivory scratched with geometrical patterns suggesting the forms of dwellings, other with the figures of fish and symbolic signs, and finally a Venus statuette, which, even without its lost head, was about six inches tall: [Note 36] Our Lady of the Mammoths, actually in situ.

At another site nearby — Timovka — about two and a half miles south of Bryansk and on a high terrace overlooking the river, where six large dwelling sites, four storage bins, and two workshops for the fashioning of flints were clustered, there was found a piece of the tusk of a young mammoth shaped as a phallus and bearing the figure of a geometrically stylized fish. Another bit of the tusk carried a rhomboid design. [Note 37] And once again, still farther south and still on the right bank of the Desna, about halfway between Bryansk and Kiev, an exceptionally rich excavation known as Mezin yielded, besides some mammoth ivory bracelets engraved with meander and zigzag designs and a pendant of mammoth ivory in the form of a tooth, two roughly carved little sitting animals, six extraordinarily beautiful mammoth-ivory birds, ranging from 1 1/2 to 4" long, and ten curiously stylized figurines, also of mammoth ivory, that have been variously identified as female nudes (Abbé Breuil), the heads of long-beaked birds (V.A. Gorodcov), and phalli (F.K. Volkov, the discoverer of the site).

It is impossible not to feel, when reviewing

the material of these mammoth-hunting stations of the loess plains

north of the Black and Caspian seas, that we are in a province

fundamentally different in style and mythology form that of the

hunters of the great painted caves. The richest center of this more

easterly style would appear to have been the area between the

Dnieper and Don river systems — at least as far as indicated by the

discoveries made up to the present. The art was not, like that of

the caves, impressionistic, but geometrically stylized, and the

chief figure was not the costumed shaman, at once animal and man,

master of the mysteries of the temple-caves, but the perfectly

naked, fertile female, standing as guardian of the hearth. And I

think it most remarkable that we detect in her surroundings a

constellation of motifs that remained closely associated with the

goddess in the later epoch of the neolithic and on into the periods

of the high civilizations: the meander (as a reference to the

labyrinth), the bird (in the dovecotes of the temples of

Aphrodite), the fish (in the fish ponds of the same temples), the

sitting animals, and the phallus.

Figure 20. Gaja-Lakṣmī (Who, furthermore, reading of the

figure amid the mammoth skulls, does not think of Artemis as the

huntress, the lady of the wild things; or of the Hindu protectress

of the home and goddess of good fortune, Lakshmi, in her

manifestation as Lakshmi of the Elephants (Gaja-Lakṣmī), where she is shown

sitting on the circular corolla of a lotus, flanked by two mighty

elephants that are pouring water upon her, either directly from

their trunks or from water jars that they have lifted above her

head?

But we must now observe, also, that on the underwings of one of the six beautiful birds of mammoth ivory discovered in this site appears the engraved swastika of which I have already spoken, the earliest swastika yet found anywhere in the world. Moreover, it is no mere crudely scratched affair, but an elaborately organized form suggesting a reference to the labyrinth, the organization, furthermore, being counter-clockwise. C. von den Steinen, long before the discovery of this site, suggested that the swastika might have been developed from the stylization of a bird in flight, above all of the stork, the enemy of the serpent, and therewith the victorious representative, of the principle of light and warmth. [Note 38] And V.A. Gorodcov, developing this idea in connection with the context of Mezin, suggests that in the geometrical motifs of the swastika, rhombus, and zigzag band or meander we may recognize a mythological constellation of “bird (specifically stork), nest, and serpent.” [Note 39]

The same motifs, it will be recalled, appeared as a fully developed ornamental syndrome in the much later ceramic art of the Samarra style, c. 4500-3500 b.c., which was developed in one of the chief areas of the high neolithic — directly southward of the Ukraine and just across the Black Sea.

And was it merely by chance that when, finally, in 1932, a household shrine was found containing female images, the number present within the shrine was precisely three? The site of this important discovery was on the right bank of the river Don, at Kostyenki, some twenty miles south of Voronesh. And in all, there were found in the same station seven fairly well preserved female figurines made of mammoth ivory, limestone, and marl, besides a large number shattered to bits; a plaque of stone engraved with the figure of a woman; a few medallions bearing representations of the female genitals; and some little animals made of marl. The figurines in the niche were: a badly preserved figure in mammoth ivory, without its head, but with well-engraved indications of a large necklace hanging from the shoulders to the breast; a large, perhaps unfinished figurine (the largest of the Russian series, we are told, but its precise dimensions were not given in the rough and ready Russian report; [Note 40] H. Kühn has estimated its height to be about one foot), [Note 41] made of limestone, but intentionally broken and the four pieces then apparently thrown into the niche; and an ill-made figure with a round head, either of mammoth tusk or of bone. The niche itself was in the northeastern corner of a dwelling, about six feet away from the fireplace, a rounded area, about two feet, eight inches across, one foot, eight inches high, and some five feet deep, within which there was nothing but these three enigmatic statuettes. [Note 42]

The most fascinating and tantalizing site of all, however (which suggests more questions that I can even enumerate in the present chapter) is at Mal’ta, in the Lake Baikal region, about fifty-five miles northwest of Irkutsk, on the Byelaya River. Just here, we recall, are the chief centers of shamanism today — whence we have already learned of the animal mother, by whom the shaman is nourished during his mysterious period of initiation. Here, too, is the center from which a considerable part of the arts and some of the races of pre-Columbian North America were derived — including the Algonquins, of whom both the Blackfeet and Ojibway are representative examples. One Soviet school of anthropology has classified the Vogul and Ostiak of the nearby Yenisei River basin as Americanoid; [Note 43] and the former Curator of Primitive and Pre-historic Art at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, Dr. Herbert Spinden, placed precisely here the mesolithic-neolithic culture center from which he derived what he termed “the American Indian Culture Complex” (c. 2500-2000 b.c.), [Note 44] a complex the main traits of which would now seem best represented by the recently studied mound-builder remains of the so-called Adena People (fl. c. 800 b.c.-700 a.d.) of the Ohio Valley [Note 45] and to the earliest signs of which — in the Red Lake Site, New York a C-14 dating of 2450 +/- 260 b.c. has just been tentatively assigned. [Note 46] We are surely, therefore, one way or another, at the crucial center of an archaic cultural continuum, running, on the one hand, back to the Aurignacian rock shelter of Laussel, on the other, forward to the Blackfoot buffalo dance of the nineteenth century a.d., and then again to the modern shamanism of the Tungus, Buriats, Ostyaks, Voguls, Tatars, even Lapps and Finns.

Here were found no less than twenty female statuettes of mammoth ivory, from 1 1/4" to 5 1/4" tall, one represented as though clothed in a cave-lion’s skin, the others nude. But in India and the Near east the usual animal-mount of the goddess was the lion; in Egypt, Sekhmet was a lioness; and in the arts both of the Hittites and of the modern Yoruba of Nigeria the goddess stands poised on the lion, nursing her child.

Some fourteen animal burials were found in Mal’ta: six of the arctic fox (do we think of Reynard and Coyote?); six of deer, in each case with the hindquarters and antlers missing (suggesting that the animals must have been flayed before burial, perhaps to furnish shamanistic attire); one of the head and neck of a large bird; and one of the foot of a mammoth. Six flying birds, and one swimming, of mammoth ivory — all representing either geese or ducks — were also found, along with an ivory fish with a spiral labyrinth stippled upon its side; an ivory baton, suggesting a shaman’s staff; and finally — most remarkably — the skeleton of a rickety four-year-old child with a copious accompaniment of mammoth-ivory ornamentation.

The little skeleton was found lying on its back in the crouch of fetus posture, but with its head turned to the left and facing the east, the point of the rising, or rebirth, of the sun. Over the grave was curved a large mammoth tusk, and within were many signs of a highly ceremonious burial. There was a great deal of red coloring matter in the grave — a common finding in paleolithic sites, as well as in the burial mounds of the North American Adena complex — and encircling the head was a delicate crown or forehead band of mammoth ivory. The child had worn, also, a bracelet of the same material and a fine necklace of six octagonal and one hundred and twenty flat ivory beads, from which a birdlike ornamental pendant hung. A second pendant, also in the form of a flying bird, lay in the grave, as well as two decorated medallions. One of the latter seems to have served as a buckle; the other, somewhat larger, showed on one side three cobralike wavy serpents, scratched or engraved, and on the other a stippled design showing a spiral of seven turns, with three spiraling S-forms enclosing it — the earliest spirals known to the history of art.

We are clearly in a paleolithic province where the serpent, labyrinth, and rebirth themes already constitute a symbolic constellation, joined to the imagery of the sunbird and the shaman flight, with the goddess in her classic role of protectress of the hearth, mother of man’s second birth, and lady of the wild things and of the food supply. She is here a patroness of the hunt, just as among planter she is the patroness of fields and crops. We cannot yet tell from the evidence whether we are to think, with Frobenius and Menghin, of a plant-oriented people that had moved up into a difficult but rewarding northern terrain of the hunt, or vice versa, of a northern hunting race, some of whose symbols were later to penetrate to the south. But what is surely clear is that a firm continuum has been established form Lake Baikal to the Pyrenees of a mythology of the mammoth-hunters in which the paramount image was the naked goddess.

Moreover, an idea can be gained of the possible relationship of the shamanistic imagery of the mammoth-ivory birds to the character of this goddess from a glance at the Eskimo mythology of the “old woman of the seals.”

Whence the earliest Eskimos came, or when they reached their circumpolar habitat, we do not know, but some part of northeast Siberia, strongly colored by the culture of the Lake Baikal zone, would now seem to have been their likely homeland, and circa 300 b.c. would be about the earliest possible date for their arrival. In the walrus-ivory carving of the Punuk period of the Bering Strait and Alaskan Eskimo (c. 500-1500 a.d.), where the naked female form and a fine sense of geometric ornamentation are prominent features, likewise in the shamanism of the Eskimos, their stone lamps, bone harpoons, tailoring of skins, and half-subterranean lodges, we recognize what must have been a more or less direct inheritance of the arts and mythologies of the paleolithic Great Hunt.

The old woman of the seals (arnarkuagssak) sits in her dwelling, in front of a lamp, beneath which there is a vessel to receive the dripping oil. She is known also a Pinga, Sedna, and the “food dish” (nerrivik). And it is either from the lamp or from the dark interior of her dwelling that she sends forth the food animals of the people: the fish, the seals, the walruses, and the whales; but when it happens that a certain filthy kind of parasite begins to fasten itself in numbers about her head, she becomes angry and withholds her boons. The word for the parasite is agdlerutt, which also means abortion or still-born child. Pinga is offended, it is said, by the Eskimo practice of abortion; but also, as Igjugarjuk has told us, “she looks after the souls of animals and does not like to see too many of them killed….The blood and entrails must be covered up after a caribou has been killed.” A seal or caribou not returned to life through proper attention to the hunting ritual is no less an “abortion,” a “still-born child” of the old woman herself, than a human baby prematurely delivered. And so, when these agdlerutt begin to afflict her, the people presently notice that their food supply has begun to fail, and it becomes the task of some highly competent shaman to undertake in trance the very dangerous journey to her dwelling, to relieve the old woman, the “food dish,” of her pain.

On the way, the shaman first must traverse the land of the happy dead, arsissut, the land of “those who live in abundance,” after which he must cross an abyss, in which, according to the earliest authors, there is a wheel, as slippery as ice, which is always turning. Next he must traverse a great boiling kettle, full of dangerous seals; after which he arrives at the old woman’s dwelling, which, however, is guarded by terrible beasts, ravenous dogs, or ravenously biting seals. And finally, when he has entered the house itself, he must cross an abyss by means of a bridge as narrow as the edge of a knife. [Note 47]

We are not told by what art his deed of assuaging the old woman is accomplished, but in the end she is relieved both of the parasites and of her wrath; the shaman returns and, presently, so do the seals.

The title of W. Somerset Maugham’s novel, The Razor’s Edge, which is drawn from a verse of the Hindu Katha Upaniṣad, wherein the mind is exhorted to enter upon the path to liberation from death, yet warned of the dangers and difficulties of the way:

Arise! Awake!

Approach the high boons and comprehend them:

The sharpened edge of a razor, hard to traverse,

A difficult path is this: so say the wise! [Note 48]

should suffice to suggest something of the general context of spiritual experience to which the Eskimo figure of a shaman crossing an abyss of the blade of a knife refers.

We may think, also, of the gallant Sir Lancelot, in Chrétien de Troyes’ courtly twelfth-century romance, Le Chevalier de la charrette, “The Knight of the Cart,” crossing the very painful “Sword Bridge” to the rescue of his Lady Guinevere, the Queen, from the land of death. “And if anyone asks of me the truth,” says Chrétien, “there never was such a bad bridge, nor one whose flooring was so bad: a polished, gleaming sword across the cold stream, stout and firm, and as long as two lances.” The water cascading beneath, furthermore, was a “wicked-looking stream, as swift and raging, black and turgid, fierce and terrible, as if it were the devil’s stream; and it is so dangerous and bottomless that anything falling into it would be as completely lost as if it fell into the salt sea.” Two lions or leopards were tied to a great rock at the farther end of this bridge; and the water and the bridge and lions were so terrible to behold that anyone standing before them all would tremble with fear. [Note 49]

We have noticed that among the earliest remains in India of the culture complex of the hieratic city state, dating from c. 2000 b.c., representations have been found of figures in yoga posture. There is also a little scene from that period showing an apparition of the goddess among the boughs of a tree. And in the much later monuments of Indian Buddhist art, these same two themes of “the path of yoga” and “the goddess” are presented in the Great Gates of the Sanchi stupas (c. 200 b.c.), where they are represented, respectively, by “the Sun-wheel of the Buddha’s Law” and “the Goddess of the Elephants,” Gaja-Lakṣmī.

But we have here broached another abyss, which lures us beyond even our longest archaeological fathom-line. For the goddess who now has shown herself at the very dawn of the first day of our own species, already attended by her well-known court (her serpents and her does and swans; the lion, the fish ponds, and the razor’s edge by which her shaman-lover is to come to her to relieve her of her sterile wrath and make her fruitful again; the little child in its confirmation clothes, in the grave-womb, well prepared for rebirth and watching for the sun-day of unquenched Sol invictus, arising form the mother womb), is still the one who can truly say ουδεις εμον πεπλον ανειλε: “No one has lifted my veil.”

III. The Master Bear

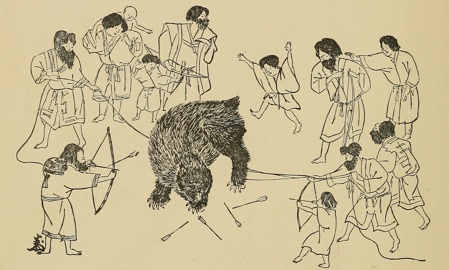

Figure 21. Ainu bear sacrificeThe Ainus of the northern

islands of Japan — Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuriles — who once

also occupied the northern part of the main island of Honshu,

constitute for the science of anthropology a fascinating problem;

for, although their body form resembles the Japanese and five

thousand miles of Mongolians separate them from the nearest native

white population, their skins are white, their eyes caucasoid, and

their hair wavy and abundant. They have been termed the hairiest

people on earth, yet they are not more so than any a Russian

muzhik. Indeed, their proud and sturdy old chieftains, copiously

bearded, with their broad noses, bushy brows, and spirited eyes,

look very much like the author of War and Peace, or a child’s

vision of Santa Claus, while their women, many of whom are shamans,

have had their natural charms embellished with natty slate-blue

mustaches, tattooed upon their upper lips at the age of thirteen to

make them elegible for marriage. Professor A.L. Kroeber classifies

this race, who now number about sixteen thousand, as “a generalized

Caucasian or divergent Mongoloid type” — if such a statement can be

called a classification; [Note 50]

but A.C. Haddon more confidently tells us that “they undoubtedly

are the relics of the eastward movement of an ancient mesocephalic

(round-headed) group of white cymotrichi (wavy-haired people, in

contrast to leiotrichi,

straight-haired, and ulotrichi, wooly-haired), who have not

left any other representatives in Asia.” [Note 51] Their language is unclassified and

apparently unique, though one of the archaic components of Japanese

must have been a dialect of the same stock. Furthermore a number of

their basic mythological and ritual forms bear a close comparison

with Shinto.

The Ainus are a semi-nomadic, paleo-Siberian fishing and hunting people, but at the same time a neolithic planting people, with the wonderful idea that the world of men is so much more beautiful than that of the gods that deities like to come here to pay us visits. On all such occasions they are in disguises. Animals, birds, insects, and fish are such visiting gods: the bear is a visiting mountain god, the owl a village god, the dolphin a god of the sea. Trees, too, are gods on earth; and even the tools that men make become gods if properly wrought. Swords and weapons, for example, may be gods; and to wear such a one as guardian gives strength. But all these, the most important divine visitor is the bear. [Note 52]

When a very young black bearcub is caught in the mountains, it is brought in triumph to the village, where it is suckled by one of the women, plays about in the lodge with her children, and is treated with great affection. As soon as it becomes big enough to hurt and scratch when it hugs, however, it is put into a strong wooden cage and kept there for about two years, fed on fish and millet porridge, until one fine September day, when the time s judged to have come to release it from its body and speed it happily back to its mountain home. The festival of this important sacrifice is called iyomande, which means “to send away,” and though a certain cruelty and baiting is involved, the whole spirit of the feast is of a joyous send-off, and the bear is supposed to be extremely happy — though perhaps surprised, if this should happen to be the first time that he has visited the Ainus — to be thus entertained.

The man who is to give the feast calls out to the people of his village, “I, so-and-so (perhaps, for example, Kawamura Monokute), am about to sacrifice the dear little divine thing from among the mountains. My friends and masters, come to the feast! Let us enjoy together the delights of the ‘sending away’! Come! Come all!”