Chapter Three

The Culture Province of the High Civilizations

One of the most interesting of the many recent developments in the field of archaeological research has been the steady progress of the excavations in the Near East, which now are bringing into focus the centers of origin and path of diffusion of the earliest neolithic culture forms. To introduce the main results of the work pertinent to our present theme, it may be noted, first, that the arts of grain agriculture and stock-breeding, which are the basic forms of economy supporting the high civilizations of the world, now seem to have made their first appearance in the Near East somewhere between 7500 and 4500 b.c., and to have spread eastward and westward from this center in a broad band displacing the earlier, much more precariously supported hunting and food-collecting cultures, until both the Pacific coast of Asia and the Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa were attained by about 2500 b.c., which yielded all the basic elements of the archaic high civilizations — writing, the wheel, mathematics, the calendar, kingship, priestcraft, the symbolism of the temple, taxation, etc. — and the mythological themes specific to this second development were then diffused comparatively rapidly, together with the technological effects, along the ways already blazed, until once again the coasts of the Pacific and Atlantic were attained.

I. The Proto-Neolithic: c. 12,500-7000 b.c.

The first phase of this crucial transformation of society appears to be represented by a series of discoveries made in the middle nineteen-twenties by Dorothy Garrod at the so-called Mount Carmel caves in Palestine. [Note 1] Artifacts similar to those she found have since been discovered as far south as Helwan, Egypt, as far north as Beirut and Yabrud, and as far east as the Kurdish hills of Iraq. The industry is known to archaeology as the Natufian, and may have flourished anywhere from the eighth to fifth milenniums b.c.; the dating is still extremely obscure. We may term its vaguely defined era the proto-neolithic and its stage of development “terminal food-gathering.” The materials suggest a congeries of nomadic, or semi-nomadic, hunting tribes with a rich variety of flint and bone implements of a late paleo- microlithic type, not yet dwelling in villages yet supplementing their food supply with some variety of grainlike grass; for sickle blades made of stone have been found among the remains, and theses suggest a harvest. Numerous bones of the pig, goat, sheep, ox, and of an equid of some sort let us know, furthermore, that if the Natufians were not yet domesticating, they were nevertheless slaughtering, the same beasts that would later constitute the basic barnyard stock of all the higher cultures. Their style of life was transitional, between the stages of food collecting and cultivation.* The real crux of the archaeological problem of the origin of the basic arts of the food-cultivators, however, rests in the question, still unanswered, as to whether such Near Eastern remains actually represent the first steps toward agriculture and stock-breeding taken anywhere in the world, or may not, rather, represent merely an area of peripheral acculturation, the superficial adoption by nomadic hunters of ideas and elements derived from somewhere else.

According to a view that has been gaining force in recent decades, the latter is the more likely case. The first plantings should be sought, according to this conjecture, in that broad equatorial zone where the vegetable world has supplied not only the food, clothing, and shelter of man since time out of mind, but also his model of the wonder of life — in its cycle of growth and decay, blossom and seed, wherein death and life appear as transformations of a single, superordinated, indestructible force. Today we find throughout this immense area a well-developed style of village life based on a garden economy of yams, coconuts, bananas, taro, etc., as well as a characteristic cultural assemblage including rectangular gabled huts, drums made of split logs and a way of communicating by drum beats, a galaxy of distinctive musical instruments, secret societies of a particular kind, tattooing, a type of bow and feathered arrow, such forms of burial and skull cult as have just been described for South or East Africa, bird-, snake-, and crocodile-worship, spirit posts and huts, particular methods of making fire, and a way of fashioning cloth of palm fiber and of bark. [Note 2] Add to these an elaborate ritual lore culminating in communal rites of animal and human sacrifice, a mythology of the journey to the land of the dead in many particulars resembling that of the Malekulan guardian of the labyrinth, an astonishing community of folklore motifs, and the spread of a single linguistic complex (the Malayo- Polynesian) from Madagascar, off the coast of Southeast Africa, to Easter Island, [Note 3] and you have a considerable base from which to argue for a common sphere. Furthermore, when it is observed (and this point is of particular moment) that it was just beyond the eastern finger of this sphere that a highly developed system of agriculture appeared in Peru and Middle America, based largely n maize but including also some fifty-odd other crops and associated with the breeding of llamas and alpacas (in Peru and turkeys (in Mexico), whereas midway in the same vast zone (the Southeast Asian neighborhood of Indo-China and Indonesia) rice agriculture, the soybean, the water-buffalo, and domestic fowl first appear, it cannot be surprising that a number of scholars have developed the concept of a single culture realm, out of which, or in association with which, three major matrices of grain agriculture matured, namely: Southeast Asia (rice), the Near East (wheat and barley), and Peru and Middle America (maize).

The archaeologists spading up the Near East, stage by stage, however, tend to believe that they are fathoming there the ultimate reach of the problem of the origins of the neolithic village — at least for the Afro-Eurasian hemisphere. In their view, the Southeast Asian complex would represent, then, the local adaptation of a system of arts carried thither by diffusion. And comparably, many of those now exploring the origins of the high civilizations of Peru and Middle America believe that these too developed independently of the primitive gardening complex of the Madagascar-to Easter-Island axis. The question is extremely complex and, for some reason, tends to involve scholars emotionally. I return to it in the following chapters, and meanwhile focus attention on a brief reconstruction of the Near Eastern chapter of this intricate story.

II. The Basal Neolithic: c. 7000-3500 b.c.*

The second phase of the crucial Near Eastern development can be assigned schematically to the millennium between 7500 and 3500 b.c. and termed the basal neolithic. Settle village life on the basis of an efficient barnyard economy now becomes a well-established pattern in the nuclear region, the chief grains being wheat and barley, and the animals the pig, goat, sheep, and ox (the dog having joined the human family much earlier as an aid to the hunters of the late paleolithic, perhaps c. 30,000 b.c).* Pottery and weaving have been added to the sum of human skills; likewise the arts of carpentry and housebuilding. And the role of women has perhaps already been greatly enhanced, both socially and symbolically; for whereas in the hunting period the chief contributors to the sustenance of the tribes had been the men and the role of the women had been largely that of drudges, now the female’s economic contributions were of firs importance. She participated — perhaps even predominated — in the planting and reaping of the crops, and , as the mother of life and nourisher of life, was thought to assist the earth symbolically in its productivity.

However, no one can speak with certainty of the social and religious place of woman in this period, for the meager evidence of the bones and coarse pottery shards reveals nothing of her lot. One has to read back, hypothetically, from the evidence of the following millennium (4500-3500 b.c.), when a multitude of female figurines appear among the potsherds. These suggest that the obvious analogy of woman’s life-giving and nourishing powers with those of the earth must already have led man to associate fertile womanhood with an idea of the motherhood of nature. We have no writing form this pre-literate age and no knowledge, consequently, of its myths or rites. It is therefore not unusual for extremely well-trained archaeologists to pretend that they cannot imagine what services the numerous female figurines might have rendered to the households for which they were designed. However, we know well enough what the services of such images were in the periods immediately following — and what they have remained to the present day. They give magical psychological aid to women in childbirth and conception, stand in house shrines to receive daily prayers and to protect the occupants form physical as well as from spiritual danger, serve to support the mind in its meditations on the mystery of being, and, since they are frequently charming to behold, serve as ornaments in the pious home. They go forth with the farmer into his fields, protect the crops, protect the cattle in the barn. They are the guardians of children. They watch over the sailor at sea and the merchant on the road.

A number of the typical and apparently perennial roles of this mother-goddess can be learned, furthermore, by simple perusing the Roman Catholic “Litany of Loreto,” which is addressed to the Virgin Mother Mary. She is there called the Holy Mother of God, the Mother of Divine Grace and Mother of Good Counsel; the Virgin most renowned, Virgin most powerful, Virgin most merciful, Virgin most faithful; and she is praised as the Mirror of Justice, Seat of Wisdom, Cause of our Joy, Gate of Heaven, Morning Star, Health of the Sick, Refuge of Sinners, Comforter of the Afflicted, and Queen of Peace; Tower of David, Tower of Ivory, and House of Gold.

Among the symbols associated with the great goddess in the archaic arts of the Mediterranean we find the mirror, the kingly throne of wisdom, the gate, the morning and evening star, and a column flanked by lions rampant. Moreover, among the numerous neolithic figurines of her we see her standing pregnant, squatting as though in childbirth, holding an infant to her breast, clutching her breasts with her two hands, or one breast while pointing with the other hand to her genitals (the posture modified in the Roman period in the celebrated image of the same goddess found in the porticus of Octavia and now in Florence, the Medicean Venus). Or again, we may see her endowed with the head of a cow, bearing in her arms a bull-headed child; standing naked on the back of a lion; or flanked by animals rampant, lions or goats. Her arms may be opened to the sides, as though to receive us, or extended, holding flowers, holding serpents. She may be crowned with the wall of a city. Or again, she may be seen sitting between the horns, or riding on the back, of a mighty bull.

III. The High Neolithic: c. 5000-3500 b.c.

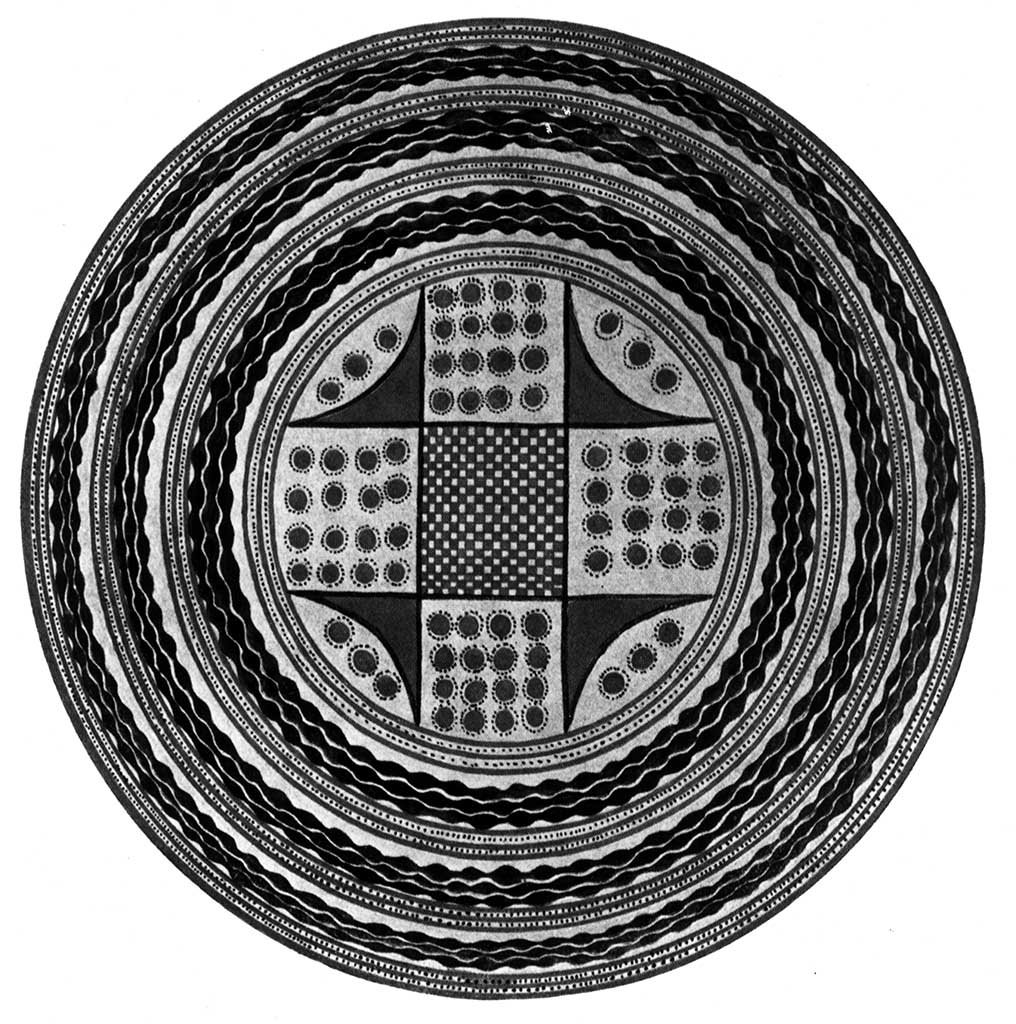

In the period in which this neolithic constellation of naked female figurines first appears, and which may be called the high neolithic, the pottery becomes suddenly — very suddenly — extraordinarily fine and beautifully decorated; showing, moreover, a totally new concept of ornamental art and of the organization of aesthetic forms, one such as had never before appeared in the history of the world. In the earlier, paleolithic art of the great caves of southern France and northern Spain — of which we treat in Part Three — -one finds no evidence of any concept of the geometrical organization of an aesthetic field. In fact, the painted or incised surfaces of the cave walls were so little regarded as fields of aesthetic interest that the animals frequently overlap each other in great tangles. Nor do we find anything like a geometrically organized aesthetic field in the works surviving from the later, terminal stages of the paleolithic. Many of the petroglyphs in the later stages of the hunting age have lost their earlier impressionistic beauty and precision; some have even deteriorated into mere geometrical scrawls or abstractions. Furthermore, on certain flat painted pebbles that have bee found in what were apparently religious sanctuaries of the hunters, geometrical devices appear: the cross, the circle with a dot in the center, a line with a dot on either side, stripes, meanders, and something resembling the letter E. However, we do not find, even in this latest stage of the hunting period, anything that could be termed a geometrical organization, anything suggesting the concept of a definitely circumscribed field in which a number of disparate elements have been united or fused into one aesthetic whole by a rhythm of beauty. Whereas suddenly — very suddenly — in the period that we are now discussing, which coincides with the appearance in the world of well-established, strongly developing settled villages, there breaks into view an abundance of the most gracefully and consciously organized circular compositions of geometrical and abstract motifs, on the pottery of the so-called Halaf and Samarra styles.

Figure 5. Pottery designs, c. 4000 b.c. Halaf ware (left), Samarra ware

(right)]

And we find certain symbols in the centers of these designs that have remained characteristic of such organizations to the present day. In the Samarra ware, for example, there occurs the earliest known association of the swastika with the center of a circular composition (there is, in fact, only one earlier known occurrence of the swastika anywhere: on the under-wings of an outstretched flying bird carved of mammoth ivory and found in a paleolithic site not far from Kiev). We find the Maltese cross, too, in the centers of these earliest known geometrical designs — occasionally modified in such a way as to suggest stylized animal forms emerging from the arms; and in several examples the figures of women appear, with their feet or heads coming together in the middle of the circular design, to form a star. Again, the forms of four gazelles may circumambulate a tree. A number of the bowls show lovely wading birds catching fish.

The archaeological site after which this superb series of decorated vessels has been named, Samarra, is located in Iraq, on the river Tigris, some seventy miles above Baghdad; and the area over which the ware has been diffused extends northward to Nineveh, southward to the head of the Persian Gulf, and eastward, across Iran, as far as the border of Afghanistan. The Halaf ware, on the other had, is scattered through an area northward of this, with its chief center in northern Syria, just south of the so-called Taurus, or Bull, Mountains of Anatolia (now Turkey), where the river Euphrates and its tributaries descend from the foothills to the plain. And what is most remarkable is the prominence in this beautifully decorated northwestern ware of the bull’s head (the so-called bucranium), viewed from the front and with great curving horns. The form is rendered both naturalistically and in variously stylized, very graceful designs. Another prominent device in this series is the double ax. We find the Maltese cross once again, as in Samarra, but no swastika, nor those graceful gazelle designs. Furthermore, in association with the female statuettes (which are numerous in this context) clay figures of the dove appear, as well as of the cow, humped ox, sheep, goat, and pig. One charming fragment represents the goddess standing, clothed, between two goats rampant — that on her left a male, the other a female giving suck to a young kid. And all the symbols are associated in this Halafian culture complex with the so-called beehive tomb.

But his is precisely the complex that appeared a full millennium later in Crete, and from there was carried by sea, through the Gates of Hercules, northward to the British Isles and southward to the Gold Coast, Nigeria, and the Congo. It is the basic complex, also, of the Mycenaean culture, from which the Greeks, and thereby ourselves, derived so many symbols. And when the cult of the dead and resurrected bull- god was carried from Syria to the Nile Delta, in the fourth or third millennium b.c., these symbols went with it. Indeed, I believe that we may claim with a very high degree of certainty that in this Halafian symbology of the bull and goddess, the dove, and the double ax, we have the earliest evidence yet discovered anywhere of the prodigiously influential mythology associated for us with the great names of Ishtar and Tammuz, Venus and Adonis, Isis and Osiris, Mary and Jesus. From the Taurus Mountains, the mountains of the bull-god, who may already have been identified with the horned moon, which dies and is resurrected three days later, the cult was diffused, with the art of cattle-breeding itself, practically to the ends of the earth; and we celebrate the mystery of that mythological death and resurrection to this day, as a promise of our own eternity. But what experience and understanding of eternity, and what of time, gave rise in that early period to this constellation of eloquent forms? And why in the image of the bull? The Sumerians

An important development, full of meaning and promise for the history of mankind in civilization t come, took place in the latter part of this same period (c. 4000 b.c.) when certain of the peasant villages began to assume the size and function of market towns and there was an expansion of the culture area southward onto the mud flats of riverine Mesopotamia. This is the period in which the mysterious race of Sumerians first appears on the scene, to establish on the torrid Tigris and Euphrates delta flats sites that were to become presently the kingly cities of Ur, Kish, Lagash, Eridu, Sippar, Shuruppak, Nippur, and Erech. The only natural resources there were mud and reeds. Wood and stone had to be imported from the north, and very soon little copper beads would begin appearing among the imports, for the age of metal was about to dawn. But the mud was fertile, and the fertility annually refreshed. Furthermore, the mud could be fashioned into sundried bricks, which now appear for the first time in history, and these could be used for the construction of temples — which likewise now appear for the first time i the history of the world. Their typical form is well known; it was that of the ziggurat in its earliest stages — a little height, artificially constructed, with a sanctuary on its summit for the ritual of the world- generating union of the earth-goddess with the lord of the sky. And if we may judge form the evidence of the following centuries, the queen or princess of each city was in those earliest days identified with the goddess, and the king, her spouse, with the god.

The painted pottery from the earliest level of these south Mesopotamian riverine sites is known to archaeology as Obeid ware, after an excavated mound, Tell el-Obeid, just south of the southern reach of the river Euphrates and not far from the ancient city (soon to rise) of Ur, from which Father Abram and his wife Sarai are supposed to have departed (Genesis 11:31). And this again is a fine, geometrically ornamented ware, somewhat less graceful, perhaps, and less colorful than the products of the rich Halaf and Samarra styles, but remarkably beautiful nevertheless. Its designs, with few exceptions, are not polychromatic, but painted on a light background in one color only, black or brown. and the period is dated circa 4000-3500 b.c. [Note 4]

IV. The Hieratic City State: c. 5400–2500 b.c.

We have taken note of : the proto-neolithic period of the Natufians, which is to be dated somewhere between 12,500 and 9500 b.c., when the first signs of an incipient grain agriculture appeared in widely scattered parts of the Near East; the basal neolithic of the earliest settled villages, circa 7000-3500 b.c., centered apparently in regions neighboring the upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates river systems, but extending eastward into Iran, westward into Anatolia (now Turkey), and southward, along the Mediterranean, into Egypt; and then, finally, the high neolithic of the Halaf and Samarra pottery styles, circa 4500-3500 b.c., when the abstract concept of a geometrically organized esthetic field and certain abstract and stylized symbols (the Maltese cross, swastika, rosette, double ax, and bucranium) first appear in our documentation of human thought, together with the earliest examples of a neolithic series of naked female figurines, representing functions of the fertility goddess of a well-established, land-rooted peasantry.

This last was the period when the earliest signs of human habitation began appearing in the mud flats of riverine Mesopotamia. Furthermore, over the whole area, from Anatolia to Egypt and from the Mediterranean to Iran, the more strategically situated villages began developing into market towns, while some of the smaller villages seem to have begun specializing in particular crafts. For example, in a small but extremely interesting site known to archaeology s Arpachiya, in northern Iraq, not for from the larger, walled settlement of Nineveh, there was found in the center of the community the large shop of an extraordinarily competent potter, who appears to have been the headman of the village. He had set out many of his bowls on display on shelves around the walls of his comparatively large adobe dwelling; so that we get the impression of a community of peasant potters, tilling their own fields and breeding their cattle, but fashioning their beautiful Halaf ware not for themselves alone but for an elite market somewhere else as well; possibly Nineveh, the nearby larger town. For trade was developing in this period no less than agriculture and the arts — the arts of pottery, stone carving, jewelry, and weaving. [Note 5]

It was, moreover, in the larger market towns of this period, as we have see, that the earliest ziggurats appeared in the course of the fourth millennium b.c., symbolizing, apparently, the pivot of the universe, where the life- generating union of the powers of earth and heaven was consummated in a ritual marriage. Perhaps the ritual was enacted by a divine queen and her souse, if kings and queens can be assumed to have come into being already in this early day. We know exactly nothing of the social and political structure of the high neolithic market town.

However, in the period immediately following — that of the heiratic city state, which may be dated for the south Mesopotamian riverine towns, schematically, circa 3500-2500 b.c. — we encounter a totally new and remarkable situation. For at the level of the archaeological stratum known as Uruk A. which is immediately above the Obeid and can be roughly placed at circa 3500 b.c., the south Mesopotamian temple areas can be seen to have increased notably in size and importance; and then, with stunning abruptness, at a crucial date that can be almost precisely fixed at 3200 b.c. (in the period of the archaeological stratum known as Uruk B), there appears in this little Sumerian mud garden — as though the flowers of its tiny cities were suddenly bursting into bloom — the whole cultural syndrome that has since constituted the germinal unit of all of the high civilizations of the world. And we cannot attribute this event to any achievement of the mentality of simple peasants. Nor was it the mechanical consequence of a simple piling up of material artifacts, economically determined. It was actually and clearly the highly conscious creation (this much can be asserted with complete assurance) of the mind and science of a new order of humanity, which had never before appeared in the history of mankind; namely, the professional, full-time, initiated, strictly regimented temple priest.

The new inspiration of civilized life was based, first, on the discovery, through long and meticulous, carefully checked and rechecked observations, that there were, besides the sun and moon, five other visible or barely visible heavenly spheres (to wit, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) which moved in established courses, according to established laws, along the ways followed by the sun and moon, among the fixed stars; and then, second, on the almost insane, playful, yet potentially terrible notion that the laws governing the movements of the seven heavenly spheres should in some mystical way be the same as those governing the life and thought of men on earth. The whole city, not simply the temple area, was now conceived as an imitation on earth of the cosmic order, a sociological “middle cosmos,” or mesocosm, established by priestcraft between the macrocosm of the universe and the microcosm of the individual, making visible the one essential form of all. The king was the center, as a human representative of the power made celestially manifest either in the sun or in the moon, according to the focus of the local cult; the walled city was organized architecturally in the design of a quartered circle (like the circles designed on the ceramic ware of the period just preceding), centered around the pivotal sanctum of the palace or ziggurat (as the ceramic designs around the cross, rosette, or swastika); and there was a mathematically structured calendar to regulate the seasons of the city’s life according to the passages of the sun and moon among the stars — as well as a highly developed system of liturgical arts, including music, the art rendering audible to human ears the world-ordering harmony of the celestial spheres.

It was at this moment in human destiny that the art of writing first appeared in the world and that scriptorially documented history therefore begins. Also, the wheel appeared. And we have evidence of the development of the two numerical systems still normally employed throughout the civilized world, the decimal and the sexigesimal; the former was used mostly for business accounts in the offices of the temple compounds, where the grain was stored that had been collected as taxes, and the latter for the ritualistic measuring of space and time as well. Three hundred and sixty degrees, then as now, represented the circumference of a circle — the cycle of the horizon — while three hundred and sixty days, plus five, marked the measurement of the circle of the year, the cycle of time. The five intercalated days that bring the total to three hundred and sixty-five were taken to represent a sacred opening through which spiritual energy flowed into the round of the temporal universe from the pleroma of eternity, and they were designated, consequently, days of holy feast and festival. Comparably, the ziggurat, the pivotal point in the center of the sacred circle of space, where the earthly and heavenly powers joined, was also characterized by the number five; for the four sides of the tower, oriented to the points of the compass, came together at the summit, the fifth point, and it was there that the energy of heaven met the earth.

This early Sumerian temple tower with the hieratically organized little city surrounding it, where everyone played his role according to the rules of a celestially inspired divine game, supplied the model of paradise that we find, centuries later, in the Hindu-Buddhist imagery of the world mountain, Sumeru, whose jeweled slopes, facing the four directions, peopled on the west by sacred serpents, on the south by gnomes, on the north by earth giants, and on the east by divine musicians, rose from the mid-point of the earth as the vertical axis of the egg-shaped universe, and bore on its quadrangular summit the palatial mansions of the deathless gods, whose towered city was known as Amaravati, “The Town Immortal.” But it was the model also of the Greek Olympus, the Aztec temples of the sun, and Dante’s holy mountain of Purgatory, bearing on its summit the Earthly Paradise. For the form and concept of the City of god conceived as a “mesocosm” (and earthly imitation of the celestial order of the macrocosm) which emerged o the threshold of history circa 3200 b.c., t precisely that geographical point where the rivers Tigris and Euphrates reach the Persian Gulf, was disseminated eastward and westward along the ways already blazed by the earlier neolithic. the wonderful life-organizing assemblage of ideas and principles — including those of kingship, writing, mathematics, and calendrical astronomy — reached the Nile, to inspire the civilization of the First Dynasty of Egypt, circa 3100 b.c.; it spread to Crete on the one hand, and, on the other, to the valley of the Indus, circa 2600 b.c.; to Shang China, circa 1600 b.c.; and , according to at least one high authority, Dr. Robert Heine-Geldern, from China across the Pacific, during the prosperous seafaring period of the late Chou Dynasty, between the seventh and fourth centuries b.c., to Peru and Middle America. [Note 6]

It the last fact be true as well as the rest (and its likelihood is considered in the following chapters), then it can be said without exaggeration that all the high civilizations of the world are to be thought of as the limbs of one great tree, whose root is in heaven. And should we now attempt to formulate the sense or meaning of that mythological root — the life-inspiring monad that precipitated the image of man’s destiny as an organ of the living cosmos — we might say that the psychological need to bring the parts of a large and socially differentiated settle community, comprising a number of newly developed social classes (priests, kings, merchants, and peasants_, into an orderly relationship to each other, and simultaneously to suggest the play through all of a higher, all-suffusing, all- informing, energizing principle — this profoundly felt psychological as well as sociological requirement must have been fulfilled with the recognition, some time in the fourth millennium b.c., of the orderly round-dance of the five visible planets and the sun and moon through the constellations of the zodiac. This celestial order then became the model for mankind in the building of an earthly order of coordinated wills — a model for both kings and philosophers, inasmuch as it seemed to show forth the supporting law not only of the universe but of every particle within it. In our normal earthly way of knowledge, we may become distracted by the multiplicity of the world’s effects, as well as by our misdirected desires for personal power and pleasure, and, losing touch with the inward order of our being, go astray. But the law of heaven now shall set us aright; for, as we read — once again — in the words of Plato: “The motions akin to the divine part in us are the thoughts and revolutions of the universe; these, therefore, every man should follow, and correcting those circuits in the head that were deranged at birth, by learning to know the harmonies and revolutions of the world, he should bring the intelligent part, according to its pristine nature, into the likeness of that which intelligence discerns, and thereby win the fulfillment of the best in life set by the gods before mankind both for this present time and for the life to come.” [Note 7]

The Egyptian term for this universal order was ma’at; in India it is dharma; and in China, tao.

And if we now try to convey in a sentence the sense and meaning of all the myths and rituals that have sprung from this conception of a universal order, we may say that they are its structuring agents, functioning to bring the human order into accord with the celestial. “The will e done on earth, as it is in heaven.” The myths and rites constitute a mesocosm — a mediating, middle cosmos, through which the microcosm of the individual is brought into relation to the macrocosm of the all. And this mesocosm is the entire context of the body social, which is thus a kind of living poem, hymn, or icon of mud and reeds, and of flesh and blood, and of dreams, fashioned into the art form of the hieratic city state. Life on earth is to mirror, as nearly perfectly as is possible in human bodies, the almost hidden — yet now discovered — order of the pageant of the spheres.