Chapter 7

The Animal Master

I. The Legend of the Buffalo Dance

The lives of the Blackfoot Indians of Montana were bound up entirely with the comings and goings of the great buffalo herds; and one of their best devices for slaughtering a large number was to lure the animals over a cliff and butcher them when they fell on the rocks below. This same device was used on the buffalo plains of Europe in the period of the great caves, c. 30,000-10,000 b.c.; and no one who has seen the paintings in those caves of the masked shamans luring bison with a lively dancing step will fail to marvel at the reaches of time and space implied in George Bird Grinnell’s descriptions of the hunts and drives in which he participated in the “Wild West” of the early 1870s — while the scholarship of that same Europe was trying to reconstruct the long-lost Aryan past of only 1500 b.c., and Wagner was building his cycle of The Ring.

In the evening of he day preceding a drive of buffalo into the pis’kun (the buffalo trap), a medicine man, usually one who was the possessor of a buffalo rock, In-is’-kim, unrolled his pipe and prayed to the Sun for success. Next morning the man who was to call the buffalo arose very early, and told his wives that they must not leave the lodge, nor even look out, until he returned; that they should keep burning sweet grass, and should pray to the Sun for his success and safety. Without eating or drinking, he then went up on the prairie, and the people followed him, and concealed themselves behind the rocks and bushes which formed the V, or chute. The medicine man put on a head-dress made of the head of a buffalo, and a robe, and then started out to approach the animals. When he had come near to the herd, he moved about until he had attracted the attention of some of the buffalo, and when they began to look at him, he walked slowly away toward the entrance of the chute. Usually the buffalo followed, and, as they did so, he gradually increased his pace. The buffalo followed more rapidly, and the man continually went a little faster. Finally, when the buffalo were fairly within the chute, the people began to rise up from behind the rock piles which the heard had passed, and to shout and wave their robes. This frightened the hindermost buffalo, which pushed forward on the others, and before long the whole herd was running at headlong speed toward the precipice, the rock piles directing them to the point over the enclosure below. When they reached it, most of the animals were pushed over, and usually even the last of the band plunged blindly down into the pis’kun. Many were killed outright by the fall; others had broken legs or broken backs, while some perhaps were uninjured. A barricade, however, prevented them from escaping, and all were soon killed by the arrows of the Indians.

It is said that there was another way to get the buffalo into this chute. A man who was very skilful in arousing the buffalo’s curiosity, might go out without disguise, and by wheeling round and round in front of the herd, appearing and disappearing, would induce them to move toward him, when it was easy to entice them into the chute. [Note 1]

Once upon a time — so a certain Blackfoot story goes — the hunters, for some reason, could not induce the animals to the fall, and the people were starving. When driven toward the cliff the beasts would run nearly to the edge, but then, swerving to right or left, go down the sloping hills and cross the valley in safety. So the people were hungry, and their case was becoming dangerous.

And so its was that, one early morning, when a young woman went to get water and saw a herd of buffalo feeding on the prairie, right at the edge of the cliff above the fall, she cried out, “Oh! If you will only jump into the corral, I shall marry one of you.”

This was said in fun, of course; not seriously. Hence, her wonder was great when she saw the animals begin to come jumping, tumbling, falling over the cliff. And then she was terrified, because a big bull with a single bound cleared the walls of the corral and approached her. “Come!” he said, and he took her by the arm.

“Oh no!” she cried, pulling back.

“But you said that if the buffalo would jump, you would marry one. See! The corral is filled.” And without further ado he led her up over the cliff and out onto the prairie.

When the people had finished killing the buffalo and cutting up the meat, they missed the young woman. Then her relatives were very sad, and her father took his bow and quiver. “I shall go find her,” he said; and he went up the cliff and over, out across the prairie.

When he had traveled a considerable distance he came to a buffalo wallow — a place where the buffalo come for water and to lie and roll. And there, a little way off, he saw a herd. Being tired, and considering what he should do, he sat down by the wallow; and while he was thinking, a beautiful black and white bird with a long, graceful tail, a magpie, came and lighted on the ground close by.

“Ha!” said the man. “You are a handsome bird! Help me! As you fly about, look everywhere for my daughter, and if you see her, say to her, ‘Your father is waiting by the wallow.’”

The magpie flew directly to the herd, and, seeing a young woman among the buffalo, he lit on the ground not far from her and began picking around, turning his head this way and that, and when close to her said, “Your father is waiting by the wallow.”

“Sh-h-h! Sh-h-h!” whispered the girl, frightened, and she glanced around; for her bull husband was sleeping close by. “Don’t speak so loudly! Go back and tell him to wait.”

Presently the bull woke and said to his wife, “Go and get me some water.”

The woman was glad and, taking a horn from his head, went to the wallow. “Father!” she said. “Why did you come? You will surely be killed.”

“I came to take my daughter home,” the man replied. “Come, let us hurry! Let us go!”

“No, no! Not now!” she said. “They would pursue and ill us. Let us wait until he sleeps again; then I shall try to slip away.”

She returned to the bull, having filled his horn with water. He drank a swallow. “Ha!” said he. “There is a person close by here.”

“No! No! No one!” the woman said. But her heart rose up.

The bull drank a little more; then got up and bellowed. What a fearful sound! Up stood the bulls, raised their short tails and shook them, tossed their great heads, and bellowed back. Then they pawed the dirt, rushed about in all directions, and, coming to the wallow, found the poor man who had come to seek his daughter. They trampled him with their hoofs, hooked him with their horns and trampled him again, so that soon not even a small piece of his body could be seen. Then his daughter wailed, “Oh, my father, my father!”

“Aha!” said the bull. “You are mourning for your father. And so, perhaps, you can now see how it is with us. We have seen our mothers, fathers, many of our relatives, hurled over the rock walls and slaughtered by your people. But I shall pity you; I shall give you just one chance. If you can bring you father to life again, you and he may go back to your people.”

The woman turned to the magpie. “Pity me! Help me now!” she said. “Go and search in the trampled mud. Try to find some little piece of my father’s body and bring it back to me.”

The magpie quickly flew to the wallow, looked in every hole and tore up the mud with his sharp beak, and then, at last, found something white. He picked the mud from around it and, pulling hard, brought out a joint of the backbone. And with this he returned to the young woman.

She place the particle of bone on the ground and, covering it with her robe, sang a certain song. Removing the robe, she saw her father’s body lying there, as though dead. Covering it with her robe again, she resumed her song, and when she next took the robe away her father was breathing; then he stood up. The buffalo were amazed. The magpie was delighted and, flying round and round, set up a clatter.

“We have seen strange things today,” the bull husband said to the others of his herd. “The man we trampled to death, into small pieces, is again alive. The people’s holy power is strong.”

He turned to the young woman. “Now,” he said, “before you and your father go, we shall teach you our dance and song. You must not forget them.” For these would be the magical means by which the buffalo killed by the people for their food should be restored to life, just as the man killed by the buffalo has been restored.

All the buffalo danced; and, as befitted the dance of such great beasts, the song was slow and solemn, the step ponderous and deliberate. And when the dance was over, the bull said, “Now go to your home and do not forget what you have seen. Teach this dance an song to your people. The sacred object of the rite is to be a bull’s head and buffalo robe. All those who dance the bulls are to wear a bull’s head and buffalo robe when they perform.”

The father and daughter returned to their camp. The people were glad when they beheld them and called a council of the chiefs. The man then told them what had happened and the chiefs selected a number of young men, who were taught the dance and song of the bulls.

And that was the way the Blackfoot association of men’s societies called I-kun-uh’-kah-tsi (All Comrades) first was organized. Its function was to regulate the ceremonial life and to punish offenses against the community. [Note 2] And it remained in force until the “iron horse” cut across the prairie, the buffalo disappeared, and the old hunters turned to farming and to various laboring jobs.

II. Paleolithic Mythology

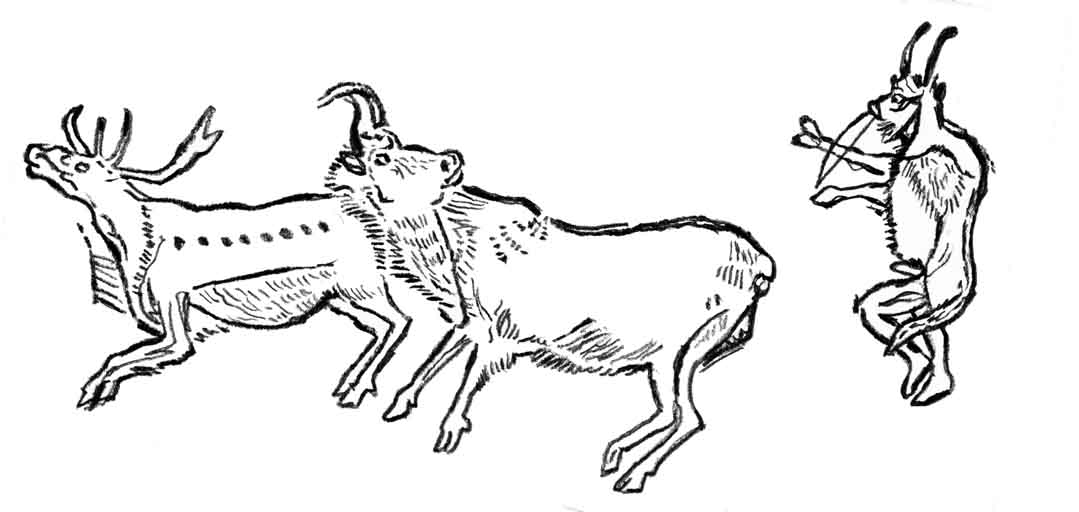

Figure 11. Figures in the sanctuary of Trois Frères

The picture in the huge paleolithic temple-cave known as Trois-Frères, in southern France, of a buffalo-dancer wearing precisely the ceremonial garb established in this legend, and functioning, apparently, in the way of the brave shaman whose power it was to lure the animals to their fall, gives a clue- — or more that a clue, I should say, a very strong suggestion — to the antiquity of the legend just told; or, at least, of its theme. Furthermore, in the neighboring cave, known as Tuc d’Audoubert, there is a chamber in which two bison are represented in bas-relief on a raised prominence, around which the footsteps of a dancer have been found. The bison represent a cow being mounted by a bull; and the dance was performed not on the full soles of the feet, but on the heels, in imitation of the hoofs of a beast. We have already said that Persephone and Demeter in their animal aspects were to be seen as pigs, and the Persephone as the bride of the monster serpent was a serpent. Here, comparably, as the bull’s wife, the maiden was, surely, a buffalo cow — so that this may well be an early representation of that same divine connubium by which the buffalo dance was given to mankind.

Figure 12. The Venus of LausselWe are reminded, also, of the

famous paleolithic figure known as the Venus of Laussel, which was

carved in bas-relief on the wall of a rock shelter in southern

France as the central figure of what was apparently a hunting

shrine. She has the great hips and breasts typical of the female

figures of the early Stone Age art, and is holding in her right

hand a bison’s horn, lifted to the level of her shoulder. The left

is placed upon her protruding belly. And sufficient traces of ocher

remained when she was found to show that she had once been painted

red. A number of other figures lay about on broken bits of rock

within the shelter: two females holding in their right hands

objects that have not been identified; a fourth in a curious

attitude, with the head and shoulders of another person upside down

beneath her, in such a position as to have suggested to dr. G.

Lalanne, its discoverer, a birth scene; [Note 3] a lithe male figure, head and arms

gone, but in an attitude suggesting the throwing of a javelin; and

finally, the fragments of a hyena and a horse, besides a number of

slabs and blocks incised with feminine genital symbols. The Abbé

Breuil, who is the world’s chief authority on the art of the French

caves, assigns these manifestations of the mythology of the hunt to

an extremely early period, namely Aurignacian and Perigordian,

which, according to the datings now generally recognized for this

art, would be c. 35,000 b.c. We do

not know the significance of the bison’s horn in the woman’s had;

but it surely was a bison’s horn and surely, too, the sanctuary

served the covenant of man and beast in connection with the hunting

rites — precisely such a relationship as that established by the

episode of our story. So that while I am not suggesting that these

findings of southern France from c. 35,000 b.c. are the illustration of a legend collected

c. 1870 a.d. on the buffalo plains

of the Wild West, it is worth remarking that a constellation of

shared motifs has begun definitely to emerge.

On the walls of many of the paleolithic caves, furthermore, the silhouetted handprints of participants in the rites have been discovered, and many of these show the same loss of finger joints that we have already remarked among the Indians of the plains.

“Old-woman’s Grandson,” ran the words of a Crow Indian’s prayer to the Morning Star, “I give you this joint (of my finger), give me something good in exchange….I am poor, give me a good horse. I want to strike one of the enemy and I want to marry a good-natured woman. I want a tent of my own to live in.” [Note 4] “During the period of my visits to the crow (1907-1916),” wrote Professor Lowie, to whom we owe the recording of this pitiful prayer, “I saw few old men with left hands intact.” [Note 5]

These are the maimed hands, then of the “honest hunters,” not the shamans; for the shamans’ bodies are indestructible and their great offerings are of the spirit, no the flesh. We are on the trail of the popular rites and myths of the earliest periods of human society of which we have record — myths and rites of an age far greater, apparently, than that of the sacrifice of the maiden, and no less great, surely, in their reach across the barriers of space. We have already remarked the vast span of the shamanistic tradition from pole to pole of the Americas, from Tierra del Fuego to the Yenisei, and from Australia to Hudson Bay. We must now begin to follow the forms of the general, exoteric hunting rites of the paleolithic sanctuaries, down into the dimmest, darkest reaches of the well of the past. The clues become fewer and more widely spaced as we proceed; and yet, throughout, we may readily recognize those that remain as suggesting at least the possibility, or even probability, of such rites as those of the buffalo dance, on back to the very beginnings of the race.

Before commencing the voyage, however, let us pause to examine the clues that our Blackfoot legend of the buffalo dance affords to the mythological atmosphere in which the paleolithic hunt was carried out. We have seven clues of particular importance.

1. As in the Ojibway legend of the origin of maize, so here, the action is not placed in the mythological age, but in a world like the present. For let us not be deceived by the speech and magic of the birds and beasts: such speech and magic are still possible to shamans, and all the chief characters in this legend are endowed with shaman power. The myths and rites of the Australians, to which we were introduced in Part One, Chapter 2, Section V, referred to a mythological time fundamentally different from our own, when the ancestors shaped the world. Such myths occur also in America. It is probable, however, that they represent a stage in the development of mythology later than do these personal adventure stories of men and women, animals and birds, endowed with shamanistic power. For where shamanism is involved, the mythological age and realm are here and now: the man or woman, animal, tree, or rock possessing shamanistic magic has immediate access to that background of dreamlike realty which for most others is crusted over.

Myths and rites referring to the mythological age, when the great mythological event took place that brought both death and reproduction into play and fixed the destiny of life-in-time through a chain reaction of significantly interlocked transformations, belong rather to the world system of the planters than to the shamanistically dominated hunting sphere. Whenever such myths are found in a hunting society, acculturation from some horticultural or agricultural center can be supposed. In the case of the Australians, the influence came from neighboring Melanesia. Likewise, among the North American tribes there were massive influences, both from the high civilizations of Middle America and from neolithic and post-neolithic China (after c. 2500 b.c.), whose influences can be traced no only south of the Yellow River into Indonesia, and from there westward to Madagascar and eastward to Brazil, but also north of the River Amur, into the very zones of northeastern Siberia from which the later North American migrations sprang. [Note 6] We are dealing, therefore, in these American myths, with an extremely complex and not a purely paleolithic inheritance. Yet many clues, as we have just observed, point to at least one important strain running back even to the period of the Aurignacian caves.

2. The rescuing hero and central figure of the legend was the magpie, without whose work as intermediary nothing could have been accomplished, and we readily recognize in him the bird form or metamorphosis (khubilgan) of the shaman- trickster. For the social function of the shaman was to serve as interpreter and intermediary between man and the powers behind the veil of nature; and this, precisely, is the function of the magpie in this tale.

3. The dead man’s return to life was made possible by the finding of a particle of bone. without this, nothing could have been accomplished. He would have passed into some other form, living for a time as a troublesome spirit, perhaps, and then returning as a buffalo, bird, or something else; but the particle of bone made it possible to bring him back just as he had been before.

We can regard this particle as our sign of the hunters’ way of thought in these matters, just as for the planting context we took the seed. The bone does not disintegrate and germinate into something else, but is the undestroyed base from which the same individual that was there before becomes magically reconstructed, to pick up life where he left it. The same man comes back; that is the point. Immortality is not thought of as a function of the group, the race, the species, but of the individual. The planter’s view is based on a sense of group participation; the hunter’s, on that sense of an immortal inhabitant within the individual which is announced in every mystical tradition, and which it has been one of the chief tasks of ontology to rationalize and define. The two views are complementary and mutually exclusive, and in their higher stages of development, in the higher religions, have yielded radically contrary views of the destiny and righteousness of man on earth.

For example, in the Hebrew cult, where the myths and rites of the earthbound, ancient civilizations of the Near East have been assimilated to a profoundly group-conscious tribal unit, the participation of the individual in the destiny of the group is stressed to such a degree that for any valid act of public worship not less that ten males above the age of thirteen are required, and the whole reference of the ceremonial system is to the holy history of the tribe; whereas in the yoga of India, where a powerful shamanistic influence from the great steppe-lands of the north has done its work, precisely the opposite is the case, and the proper place for a full experience of the ultimate reach of the mystery of being is the utter solitude of a Himalayan peak.

4. The game animals of the legend, refusing the fall and then going over it, were acting under the influence of the great bull, who represents a type of being that plays a prominent role in hunting myths, namely, the animal archetype or animal master. We may think of him as comparable to the first bird, whirled clockwise around the head of the Apache Hactcin, or the first quadruped, from which the others came. Or again, using a philosophical term not as remote from primitive thought as it may seem, we might say that the great bull represents the Platonic Idea of the species. He is a figure of one more dimension that the others of his herd: timeless and indestructible, whereas they are mere shadows (like ourselves), subject to the laws of time and space. They fell and were killed, whereas he was unharmed. He is a manifestation of that point, principle, or aspect of the realm of essence from which the creatures of his species spring.

For the fact that the animal species, in contrast to man, are comparatively stereotyped in their innate releasing mechanisms has made them excellent representatives of the mystery of permanence in change. Each kind has, so to say, its own group soul. No matter how many individual animals may be shot down, others keep pouring forth and are ever the same. The biblical notion, the Platonic-Aristotelean notion, for which conservative Christians have fought a valiant though losing battle, the notion of “fixed species” — with all of its pseudo-philosophical implications about the timeless will and plan of some master mind, some master puppeteer, and about fixed laws and realms of essence within or supporting this phantasmagoria of apparent change — we can regard as of paleolithic antiquity. For it holds a prominent place in all primitive thought.

5. Since it appears that when the animals went over the fall they did so according to the will of their animal master, their flesh is to be regarded as the willed gift of that master to the people, according to the magical order of nature. and this was the primary lesson of the legend for the Blackfeet themselves. Killing buffalo is not against the way of nature. On the contrary, according to the way of nature, life eats life; and the animal is a willing victim, giving its flesh to be the food of the people.

6. But there is a right and a wrong way to kill. The girl revived her father by means of the magic of the rescued piece of bone, and when the great bull saw that the people’s magic was strong enough to bring back to life those apparently dead, he communicated to them the magical dance and ritual chant of the buffalo, by which the animals killed in the buffalo drives might be returned to life. For where there is magic there is no death. And where the animal rites are properly celebrated by the people, there is a magical, wonderful accord between the beasts and those who have to hunt them. The buffalo dance, properly performed, insures that the creatures slaughtered shall be giving only their bodies, no their essence, no their lives. And so they will live again, or rather, live on; and will be there to return the following season.

The hunt itself, therefore, is a rite of sacrifice, sacred, and not a rawly secular affair. And the dance and chant received from the buffalo themselves are no less a part of the technique of the hunt than the buffalo drive and acts of slaughter. Human sacrifice, such as we found in the plant-dominated, equatorial domain, where an identification of human destiny with the model of the vegetable world conduced to rites of death, decay, and fruitful metamorphosis, we do not find among hunters unless there has been some very strong influence from the other zone (as, for example, in certain rituals of the Pawnee). The proper sacrifice for the hunter is the animal itself, which through its death and return represents the play of the permanent substance or essence in the shadow-world of accident and chance. One may hear in the chant of the dancing buffalo, therefore — slow and solemn, ponderous and deliberate, as is fitting to such great beasts — a paleolithic prelude to the great theme of the Hindu Bhagavad Gītā, the mystical song of the lord Viṣṇu, the cosmic dreamer of the cosmic dream: “Know that by which all of this is pervaded to be imperishable. Only the bodies, of which this eternal, imperishable, incomprehensible Self is the indweller, can be said to have an end”; [Note 7] or the words of the Greek sage Pythagoras: “All things are changing; nothing dies. The spirit wanders, comes now here, now there, and occupies whatever frame it pleases. From beasts it passes into human bodies, and from our bodies into beasts, but never perishes.” [Note 8]

Compare the Caribou Eskimo Igjugarjuk. “Pinga,” he said, naming the female guardian of the animals, to whose realm the powerful shamans go when they seek to increase a failing food supply, “looks after the souls of animals and does not like to see too many of them killed. Nothing is lost; the blood and entrails must be covered up after a caribou has been killed. So we see that life is endless. Only we do not know in what form we shall reappear after death.” [Note 9]

7. It is to be noted, finally, that the social organization of the Blackfoot tribe itself was based on the hierarchy of the All Comrades Society, which is supposed to have been founded following this adventure. Grinnell has given a list of the orders of this hierarchy, as they were known at the time of his visit:

- Little Birds

— boys from 15 to 20 years old

- Pigeons — men

who have been several times to war

- Mosquitoes —

men who are constantly going to war

- Braves —

tried warriors

- All Crazy

Dogs — men about forty years old

- Raven Bearers

— (not described)

- Dogs' Tails —

old men: two societies, but they dress alike and

dance together

- Horns; Bloods

— societies with peculiar secret ceremonies

- Soldiers —

(not described)

- Bulls — a

society wearing the bull’s heads and robes.

[Note

10]

And so it appears that, just as in the great creative period of the hieratic city state a game of identification with the round dance of the planets in the heavens led to an organization of society in which the notion of a macrocosmic, calendrically rendered, celestial order supplied the mythology according to which the “mesocosm” of the state was composed; and as in the tropical areas, where the plant world supplied the chief sustenance for mankind and the chief model of the mystery of life, a game in which young men and women, identified with the first victim of the mythological age, supplied the base and focal episode of a group-coordinating ceremonial structure; so here, the game of identification was played in relation to the animals — and in particular those upon which the life of the human society depended. And the game was that of a mutual understanding, supposed to exist between the two worlds, realized and represented in rites, upon the proper performance of which depended the well-being of both the animals and their companions and co-players, men. This game provided the basis for the idea of the totem, to which so much attention was given by anthropologists in the last years of the nineteenth century that every appearance of an animal anywhere in myth or rite was interpreted as a vestige of totemism — whereas, actually, totemism is but one aspect or inflection of a larger principle, which is represented equally well in the “animal master” and in the “animal guardian” or personal patron.

In a totemistically conceived society the various clans or groups are regarded as having semi-animal, semi-human ancestors, from which the animals species of like name is likewise descended; and the members of the clan are prohibited both from killing and eating the beasts who are their cousins and from marrying within their totem group. Many North American Indian tribes and most Australian are totemistic, and there is reason to believe that the idea goes far back into the past. However, it does no exhaust by any means the modes of relationship of the hunting world to that of their neighbors and companions in life, the beasts. For the animals are great shamans and great teachers, as well as co-descendants of the totem ancestors. They fill the world of the hunter, inside and out. And any beast that may pass, whether flying as a bird, trotting as a quadruped, or wriggling in the way of a snake, may be a messenger signalling some wonder — perhaps the transformation of a shaman, or one’s personal guardian come to bestow its warning or protection.

III. The Ritual of the Returned Blood

One of the most illuminating glimpses into the very deep will of past into which we are about to plunge, where in the long ages before mankind was struck by the principle of destiny of the vegetable kingdom it was the mystery of the deathless animal herd and the laws of the hunt that ruled his spirit, Frobenius records in one of his accounts of his journeys in Africa:

In the year 1905, in the jungle area between Kassai and Luebo (in the Belgian Congo), I encountered some representatives of those hunting tribes, driven from the plateau to the refuge of the Congo jungle, who have become known to the literature of Africa as “Pygmies.” Four of their number, three men and a woman, then accompanied the expedition for about a week. One day — it was toward evening and we had already begun to get along with each other famously — there was again a pressing need for replenishments in the camp kitchen and I asked the three little men if they would get us an antelope, which for them, as hunters, would be an easy task. They looked at me, however, in amazement, and one of them finally came out with the answer that, surely, they would be glad to do that little thing for us, but today it would of course be impossible, since no preparations had been made. The conclusion of what turned out to be the very long transaction was that the hunters declared themselves ready to make their preparations next morning at dawn. and with that, we parted. The men then began scouting about and finally settled upon a high place on a nearby hill.

Since I was very curious to know whereof the preparations of these people might consist, I got up before sunrise and hid in some bushes near the clearing that the little fellows had chosen the night before for their preparations. When it was still dark the men arrived; but not alone. They were accompanied by the woman. The men crouched on the ground and cleared the area of all bits of growth, after which they smoothed it flat. One of them then drew something in the sand with his finger, while the other men and the woman muttered formulae of some kind and prayers; after which silence fell, while they waited for something. The sun appeared on the horizon. One of the men, with an arrow in his drawn bow, stepped over to the cleared ground. In a couple of moments the rays of the sun struck the drawing and at the same instant the following took place at lightning speed: the woman lifted her hands as though reaching for the sun and uttered loudly some unintelligible syllables; the man released his arrow; the woman cried out again; then the men dashed into the forest with their weapons. The woman remained standing a few minutes and then returned to the camp. When she had left, I came out of my hiding and saw that what had been drawn on the ground was an antelope, some four feet long: and the arrow was stuck in its neck.

While the men were gone I wanted to return to the place to try to take a photograph, but the woman, who stayed close to me, kept me from doing so, and begged me earnestly to give up my plan. And so, the expedition went on. The hunters caught up with us that afternoon with a beautiful buck. It had been shot with an arrow through the neck. The little people delivered their quarry and went, then, with a few tufts of its hair and a calabash full of its blood back to their place on the hill. They caught up with us again only two days later and that evening, to the froth of palm wine, I brought myself to speak about the matter with the most trusting of my little trio. He was the oldest of the three. And he told me simply that he and the others had run back to plaster the hair and blood on their drawing of the antelope, pull out the arrow, and then erase the picture. As to the sense of the operation, nothing could be learned, except that he said that if they did not do this the “blood” of the antelope would be destroyed. And the erasure had to be effected at sunrise too.

He pleaded earnestly that I should not let the woman know that he had talked to me about these things. And he seemed, indeed, to be greatly worried about the consequences of his talk; for the next day our Pygmies left us without saying as much as good-bye — undoubtedly at his request, who had been the leader of the little team. [Note 11]

We need only recall the words of the Caribou Eskimo Igjugarjuk to understand the meaning, and therewith, also, the antiquity and durability of this ideology which is found to be the same, fundamentally, whether in the jungles of the Congo or on the tundras of Hudson Bay: “The blood and entrails must be covered up after a caribou has been killed. So we see that life is endless.”

“It takes a powerful magic,” is the comment of Frobenius, “to spill blood and not be overtaken by the blood-revenge.” [Note 12]

One thing more: the crucial point of the Pygmy ceremony was that the rite should take place at dawn, the arrow flying into the antelope precisely when it was struck by a ray of the sun. For the sun is in all hunting mythologies a great hunter. He is the lion whose roar scatters the herds, whose pounce at the neck of the antelope slays it; the great eagle whose plunge traps the lamb; he is the luminous orb whose rays at dawn scatter the herds of the night sky, the stars. One sees the evidence of this primitive hunting myth in the motif, so common in paleolithic art, of the lion pouncing on the neck of the antelope that has just turned its head to look behind it, as well as in that other motif, which is one of the first to appear in ancient Sumerian art, of the solar eagle, clutching an antelope in each claw.

The lesson reads, by analogy: The sun is the hunter, the sun’s ray is the arrow, the antelope is one of the herd of the stars; ergo, as tomorrow night will see the star return, so will tomorrow the antelope. Nor has the hunter killed the beast as a personal, willful act, but according to the provisions of the great Spirit. and in this way “nothing is lost.”