Chapter Four

The Province of the Immolated Kings

I. The Legend of the Destruction of Kash

A legend throwing a beam of light into the past of the now largely Mohammedan Sudan was told in 1912, in the marketplace of the capital of Kordofan, by a proud graybeard, Arach-ben-Hassul, captain of the camel-boys of the Frobenius Kordofan Expedition. The little city of El Obeid, some 240 mile southwestward of Khartoum (not to be confused with the Tell-el-Obeid of Chapter 3, which is in Iraq), was teeming with tribesmen from every quarter of the bleak and sparsely populated countryside — Berbers, Arabs, Nubians, forgotten tribesmen from the fastnesses of the outlying hills — who had come streaming in to shout welcome to the new consul general, Lord Kitchener. The period was a delicate one politically. Italy had opened war on Turkey, bombarding Prevaza without warning and occupying Tripoli, Cyrenaica, and the Dodecanese Islands; so that Kitchener, to keep his charges occupied with their own affairs, had instituted a broad program of economic reform: the opening of cotton markets throughout the country, village schools, savings banks, cantonal courts, and a heightening of the Aswan dam. It was a fortunate moment for the science of comparative mythology that set the German pencils to work among the squatting clusters of camel- keepers, cattle nomads, and chivalrous bandits who were listening everywhere to the story-tellers rehearsing the old legends of the great past of Kordofan, of Darfur to the west. Ethiopia eastward, Nubia to the north, and Darnuba to the south. Arach-ben-Hassul, from the province of Darfur, was a descendant of one of the last surviving families of the old guild of the coppercraftsmen of Kordofan, and he to sat listening. For seven days he sat in silence behind his beard. And when he had listened for seven days, on the eighth day Arach-ben-Hassul stood up, passed his hand across his eyes, down his face, and to his beard, and said, “I speak.”

His tale was “The Legend of the Destruction of Kash,” of a time — not once upon a time,” but in a period long past — when this region, which today is a cultural as well as a physical desert, was green and great.

“Four kings at that time ruled an empire in this realm,” he told the squatting cluster of scions of the great past:

and the first king dwelt in Nubia, the second in Ethiopia, a third in Kordofan, and the fourth in Darfur; but the richest of the four was the Nap of Napata in Kordofan, whose capital stood near the site of the village now call Hophrat- en-Nahas. The Nap of Napata was the possessor of all the copper and gold of the region. His gold and copper were carried to Nubia, to be sent to the great kings of the West. Also, envoys arrived in his court from eastward, from over sea, by ship. And to the south he held domain over many peoples: these forged for him iron weapons and furnished slaves by the many thousand for his court.

But now, although this king was the richest man on earth, his life was the saddest and shortest of all mankind; for each Nap of Napata could rule but a brief span of years. Throughout his reign the priests every night observed the stars, made offerings, kindled sacred fires; and they were not to miss a night of these prayers and offerings, lest they should lose track of the stars and not know when, according to practice, the king was to be killed. The custom had come down from time out of mind. Night by night, year after year, the priests were to keep watch for the day when the king should be killed.

And so, once again, as so many times before, that day arrived. The hind legs of sacrificial bulls were slashed; the fires of the land were extinguished; women were locked indoors; and the priests kindled the new fire. They summoned the new king. He was the son of the sister of the one just killed, and his name, this time, was Akaf: but Akaf was the king in whose period the ancient customs of the land were changed — and people say that this change was the cause of the destruction of Napata.

Now the first official act of every Nap of Napata was that of deciding what persons should accompany him on the path of death. They were to be chosen from those dearest to him, and the first named would be the one to lead the rest. A slave named Far-li-mas, celebrated for his story-telling art, had arrived in the court some years before from over sea, sent as a gift by a king of the distant East. and the new Nap of Napata said: “This man shall be my first companion. He well entertain me until the time for my death; and make me happy after death.”

When Far-li-mas heard, he was not afraid. He only said to himself: “I is God’s will.”

And it was, moreover, the custom at that time in Napata that a flame should be dept burning perpetually, just as today in certain secluded places in Darfur; and for its maintenance the priests were to designate a young boy and girl. These should watch the fire, be absolutely chaste throughout their lives, and be killed, not together with the king, but immediately after, at the moment of the kindling of the new flame. And so, now, when the new fire had been established for Akaf, the priests chose as vestal for the coming term the youngest sister of the new king. Her name was Sali — Sali-fu-Hamr. But she was afraid of death and, when she heard how the choice had fallen, was appalled.

The king lived, for a while, happily, in great delight, enjoying the wealth and majesty of his domain. He spent each evening with his friends and with whatever visitors may have come as envoys to the court. But one fateful night God allowed him to realize that with each of these joyous days he was moving one step closer to certain death; and he was filled with fear. He was unable to turn the dreadful thought away and became depressed. Whereupon God sent him a second thought: that of letting Far-li-mas tell a story.

Far-li-mas, therefore, was summoned. He appeared, and the king said: “Far-li-mas, today the day has arrived when you must cheer me. Tell me a story.” “The performance is quicker than the command,” said Far-li-mas, and began. The king listened; the guests also listened. The king and his guests forgot to drink, forgot to breathe. The slaves forgot to serve. They, too, forgot to breathe. For the art of Far- li-mas was like hashish, and, when he had ended, all were as though enveloped in a delightful swoon. The king had forgotten his thoughts of death. Nor had any realized that they were being held from twilight until dawn; but when the guests departed they found the sun in the sky.

Akaf and his company, that day, could hardly wait till evening; and thereafter, every day, Far-li-mas was summoned to perform. The report of his tales spread throughout the court, the city, the land, and the king presented him, each day, with the gift of a beautiful garment. The guests and envoys gave him gold and jewels. He became rich. and when he now went through the streets he was followed by a troop of slaves. The people loved him. they began to bare their breasts to him, in sign of honor.

Sali, hearing of the wonder, sent a message to her brother. “Let me,” she asked, “just once, hear Far-li-mas tell a story!”

“The fulfillment goes before the wish,” the king replied.

And Sali came.

Far-li-mas saw Sali and for a moment lost his senses. All that he saw was Sali.

All that Sali saw was Far-li-mas.

The king said: “But why do you not begin your story? Do you not know any more?”

Removing his eyes from Sali, the story-teller began. and his tale was first like the hashish that induces a gentle stupefication, but then like the hashish that carries men through unconsciousness to sleep. After a time the guests were sleeping; the king was sleeping. They were hearing the story only in dream, until they were carried entirely away, and only Sali remained awake. Her eyes were fixed on Far-li- mas. She was filled completely with Far-li-mas. And when he had finished the tale and arose, she, too, arose.

Far-li-mas moved toward Sali: Sali toward far-li-mas. He embraced her: she embraced him, and she said: “We do not want to die.” He laughed into her eyes. “It is yours to command,” he said. “Show me the way.” And she answered: “Leave me now. I shall think of a way, and when the way has been found shall call you.” They parted. And the king and his guests lay there asleep.

That day, Sali went to the high priest. “Who is it determines the tie when the old fire is put out,” she asked, “and the new one kindled?”

“That is decided by God,” answered the priest.

Sali asked; “But how does God communicate his will to you?”

“Every night we keep watch on the stars,” the priest said. “We do not let them out of our sight. Every night we observe the moon and we know, from night to night, which stars are approaching the moon and which moving away. It is by this that we know.”

Sali said: “And you must do that every night? What happens of a night when nothing can be seen?”

The priest said: “On such a night we make many offerings. If a number of nights should pass when nothing could be seen, we should not be able to find our stars again.”

Sali said: “Would you then not know when the fire should be extinguished?”

“No,” said the priest, “we should not be in a position, then, to fulfill our office.”

Whereupon Sali said to him: “God’s works are great. The greatest, however, is not his writing in the sky. His greatest work is our life on earth. This I learned last night.”

“What do you mean?” said the priest.

And Sali answered: “God gave Far-li-mas the gift of telling tales in a way that has never before been equaled. It is greater than his writing in the sky.”

The priest retorted: “You are wrong.” But Sali said to him: “The moon and stars, these you know. But have you heard the tales of Far-li-mas?”

“No,” said the priest, “I have not heard them.”

She asked: “How, then, can you pronounce a judgment? I assure you that even you priests, when listening, will forget to keep watch of the stars.”

“Sister of the king, are you quite sure?”

She answered: “Only prove to me that I am wrong and that the writing in the sky is greater and stronger than this life on earth.”

“That is just what I shall prove,” said the priest.

And the priest then sent word to the young king. “Allow the priests to come to your palace tonight and listen to the tales of Far-li-mas from the setting to the rising of the sun.”

The king consented, and Sali sent word to Far-li-mas: “Tonight you must do as you did before. This will be the way.”

And so, when the sun was approaching the hour of its setting and the king, his guests, and the envoys were assembling, they were joined by all the priests, who bared the upper parts of their bodies and prostrated themselves on the ground. The high priest said: “It has been declared that the tales of Far-li-mas are the greatest of God’s works.” the king said to him: “you may decide for yourselves.” “You will pardon us, O King,” prayed the high priest, “if we depart from your palace at the rising of the moon, to fulfill the duties of our office.” And the king replied: “Act according to God’s will.”

Whereupon the priests took their places. The guests and the envoys took their places. The hall was filled with people and Far-li-mas made a way between them. “Begin,” said the king. “Begin, my dear Companion in Death.” Far-li-mas looked at Sali, Sali at Far-li-mas; and the king said: “But why do you not begin your story? Do you not know any more?”

Removing his eyes from Sali, the story-teller began.

And his tale commenced as the sun was going down. It was like the hashish that beclouds and transports. It was like the hashish that induces faintness. It was like the hashish that sends one into a dead faint. So that when the moon rose, the king, his guests, and the envoys lay asleep, and the priests too lay in a sound sleep. Only Sali was awake, drawing in with her eyes sweet words from the lips of Far-li- mas.

The tale was ended, Far-li-mas rose and moved toward Sali; she toward him, and she said: “Let me kiss these kips, from which come words that are so sweet.” She pressed close to his lips, and Far-li-mas said to her: “Let me embrace this form that has given me the power.” They embraced, entwining arms and legs, and lay awake among those that slumbered, knowing such happiness as breaks the heart. Rejoicing, Sali asked: “Do you see the way?” “Yes,” the other replied, “I do.” And they left the hall. So that in the palace there remained only those that slept.

Sali came to the high priest the next morning. “So now tell me,” she said, “whether you were right in your condemnation of my judgment.”

He answered: “I shall not give my reply today. We must listen once more to Far-li-mas; for yesterday we were not prepared.”

And so, the priests attended to their prayers and offerings. The fetlocks of many bullocks were slashed, and throughout the day, without pause, prayers were recited in the temple. When evening came they arrived in the palace.

Sali sat again beside the king, her brother, and Far-li-mas commenced his tale. So that once again, before the dawn had come, all slept — the king, his guests, the envoys, and the priests — enwrapt in rapture. But Sali and Far-li-mas were awake among them and sucked joy from each other’s lips. And they embraced again, entwining arms and legs. And thus it continued, from day to day, for many days.

But if there had gone out among the people, at first, the news of Far-li-mas’ tales, now there went out among them the rumor that the priests were neglecting their offerings and prayer. Uneasiness began to spread abroad, until, one day, a distinguished gentleman of the city paid a visit to the high priest.

“When do we celebrate the next festival of the season?” he asked. “I am planning a voyage and wish to return for the feast. How long have I got?”

The priest was embarrassed; for it had been many nights since he had seen the moon and stars. He replied: “wait only one day; then I shall tell you.”

“My thanks,” said the man. “I shall return tomorrow.”

The priests were summoned and their chief inquired: “Which of you, recently, has observed the course of the stars?”

They were silent. Not a single voice replied; for all had been listening to the tales of Far-li-mas.

“Is there not one among you that has observed the course of the stars and position of the moon?”

They sat perfectly still, until one, who was very old, arose and spoke. “We were enchanted,” he said, “by Far-li- mas. Not one of us can tell you when the feasts are to be celebrated, when the fire is to be quenched, and when the new fire is to be kindled.”

The high priest was terrified. “How can this be?” he cried. “What shall I tell the people?”

The very old priest replied: “It is the will of God. But if Far-li-mas has not been sent by God, let him be killed; for as long as he lives and speaks, everything will listen.”

“What, however, shall I tell the man?” the high priest demanded.

Whereat all were silent. And the company, then silently dispersed.

The high priest went to Sali. “What was it,” he asked, “that you said to me on that first day?”

She answered, “I said, ‘God’s works are great. The greatest, however, is not his writing in the sky, but the life on earth.’ You rejected my word as untrue. But now, today, tell me whether I lied.”

The priest said to her: “Far-li-mas is against God. He must die.”

But Sali answered: “Far-li-mas is the Companion in Death of the king.”

The priest said: “I shall speak with the king.”

And Sali answered: “God dwells in my brother. Ask him what he thinks.”

The high priest proceeded to the palace and addressed himself to the king, whose sister, Sali, now sat beside him. The high priest bared his chest before the king, and, throwing himself on the ground, prayed: “Pardon, Akaf, O my King!”

“Tell me,” said the king, “what is in your heart.”

“Speak to me,” the high priest said, “of Far-li-mas your Companion in Death.”

The king said to him: “God sent me, first, the thought of the approaching day of my death, and I was afraid. God sent me, next, the recollection of Far-li-mas, who was sent to me as a gift from the land eastward, beyond the sea. God confused my understanding with the first thought. With the second he enlivened my spirits and made me — and all others — -happy. so I gave beautiful garments to Far-li-mas. My friends gave him gold and jewels. He distributed much of this among the people. He is rich, as he deserves to be; and the people love him, as I do.”

“Far-li-mas,” the high priest said, “must die. Far-li-mas is disrupting the revealed order.”

Said the king, “I die before him.”

But the priest said: “The will of god will give the decision in this matter.”

“So be it! And to this,” the king replied, “the whole people shall bear witness.”

The priest departed, and Sali spoke to Akaf. “O my King! O my brother! The end of the road is near. The companion of your death will be the awakener of your life. However, I require him for myself, as the fulfillment of my destiny.”

“My sister Sali,” said Akaf, “then you may take him.”

Heralds went out through the city and cried in every quarter that Far-li-mas, that evening, would speak in the great square before all. A veiled throne for the king was erected in the large plaza between the royal palace an the buildings of the priests, and when evening came, the people streamed from all sides and settled everywhere, round about. thousands upon thousands assembled. The priests arrived and took their places. The guests and the envoys arrived and were seated. Sali sat beside her brother, Akaf, the veiled king; and Far-li-mas then was called.

He arrived. His entire retinue came behind him, all clothed in dazzling garments, and they placed themselves opposite the priests. Far-li-mas, himself, bowed before the veiled king, and assumed his seat.

The high priest arose. “Far-li-mas has destroyed our established order,” he said. “Tonight will show if this was by the will of God.” And he resumed his place.

Far-li-mas removed his eyes from Sali, gazed about over the multitude, glanced at the priests, and arose. “I am a servant of God,” he said, “and believe that all evil in the human heart is repugnant to God. Tonight,” said Far-li-mas, “God will decide.” And he commenced his tale.

His words were at first as sweet as honey, his voice penetrating the multitude as the first rain of summer the parched earth. From his tongue there went forth a perfume more exquisite than musk or incense: his head shone like a light, the only luminary in a black night. And his tale in the beginning was like the hashish that makes people happy when awake; then it became like the hashish of a dreamer. Toward morning he raised his voice, however, and his words swelled like the rising Nile in the hearts of the people: they were for some as pacifying as the entrance into Paradise, but as frightening for others as the Angel of Death. Joy filled the spirits of some, horror the hearts of others. And the closer the moment of dawn, the more powerful became his voice, the louder its reverberations within the people, until the hearts of the multitude reared against each other as in a battle; stormed against each other like the clouds in the heavens of a tempestuous night. Lightning bolts of anger and thunderclaps of wrath collided.

But when the sun rose and the tale of Far-li-mas closed, unspeakable astonishment filled the confused minds of all; for when those who remained alive looked about them their glances fell upon the priests — and the priests lay dead upon the ground.

Sali got up and prostrated herself before the veiled king. “O my King!” she said, “O my brother! Akaf! Throw from yourself the veil; show yourself to your people and offer up the offering, now, yourself! For these here have been mowed down by the angel of Death, Azrail, through God’s command.”

The servants removed the veil from around the royal throne and Akaf stood up. He was the first of their line of kings whom the people of Napata had ever seen. He was young, and as beautiful to look upon as the rising sun.

The multitude was jubilant. A white steed was brought, which the king mounted. At his left there walked his sister, at his right, the teller of tales, and he rode to the temple. The young king took up the mattock in the temple and hoed three holes in the holy ground. Far-li-mas tossed three seeds into these. The king then hoed two holes in the holy ground and Sali tossed two seeds into these. Immediately and simultaneously the five seeds sprouted, growing before the eyes of the people, and by noon the heads of grain of all five were ripe. In all the courts of the city the fathers of families slashed the fetlocks of great bulls. The king extinguished the fire in the temple, and all the fathers of the city extinguished the fires of their hearths. Sali kindled the new fire, and all of the young virgins in the city came and took fire from this flame. and since that day, there have been no more human sacrifices in Napata.

Thus Akaf became the first Nap of Napata to remain alive until it pleased God to take him in his old age, and when he died Far-li-mas succeeded to his throne. With that, however, the city of Napata reached the culmination of its fortune and the end. For Akaf’s renown as a wise and well-advised prince had spread abroad, through every land, and every king had sent to him men of intelligence, with gifts, to receive the benefit of his advice. Great merchants had settled in his capital and he had had many great ships upon the seas eastward, transporting the products of Napata throughout the world. His mines had not been able to yield gold and copper enough for the demand. and when he was succeeded by Far-li- mas, the fortune of the realm rose even higher, to its climax. The fame of Far-li-mas filled every land, from the sea in the east to that in the west. and with such fame there came so much envy into men’s hearts that, when Far-li- mas died, the neighboring countries broke their treaties, opening war on the kingdom of Napata, and Napata succumbed. Napata was destroyed. The empire fell apart. It was overwhelmed by savages and barbarians. The gold and copper mines were forgotten; the cities disappeared. And nothing remained of the great days but the memory of the tales of Far-li-mas — which he had brought with him from his own land eastward, beyond the sea.

This, then, is the story of the destruction of the land of Kash, the last of whose children now are dwelling in Darfur. [Note 1]

II. A Night of Shehrzad

Leo Frobenius, to whom we owe the recording and publication of this legend from the lips of the old captain of his camel- boys, has pointed out that in the Historical Library of the Sicilian annalist Diodorus Siculus, who visited Egypt between the years 60 and 57 b.c., there is an account of the practice of ritual regicide among the Nubian Kassites of the Upper Nile, in the province then known as Meroe-Napata. [Note 2] The priests would send a messenger to the king, declaring that the gods had revealed the moment to them through an oracle, and the kings, as Diodorus declares, submitted to this judgment through superstition. However, Diodorus goes on to say, in the period of the Alexandrian pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309-246 b.c.), the custom was disregarded by an Ethiopian monarch named Ergamenes, who had received a Greek education. Placing his trust rather in philosophy than in religion, and with a courage worthy of the tenant of a throne, Ergamenes walked with a body of soldiers into the hitherto solemnly feared sanctuary of the Golden Temple, slew the priests to a man, discontinued the tradition derived from the awesome past, and reorganized things according to his own taste. [Note 3]

Arach-be-Hassul’s tale itself, as Frobenius observes, suggests the Arabian Nights, not only in its narrative style and fabulous atmosphere but also in its theme. For, as all recall, in the frame story of that collection the clever bride, Shehrzad, through her fascinating story-telling art rescued from death both herself and all the maidens of her generation; whereas here we have the same art achieving a like result — rescuing now, however, the king too from death, as well as the clever young woman who, like Shehrzad, was the instigator of the whole operation.

The dates of the formation of the main body of the Arabian Nights lie between the eighth and fourteenth centuries a.d., though some of the tales appear to have been composed and added as late as the seventeenth century. [Note 4] The period is one to which the world owes a great many of its most fascinating wonder tales, since it was precisely in those centuries — throughout the Middle Ages, that is to say — that the custom of telling stories flourished most elegantly in the courts of Europe, India, and Persia, as well as in Arabia and Egypt. It must be recognized, therefore, that although our “Legend of the Destruction of Kash” may indeed be founded on some such act a s that recorded of Ergamenes in the third century b.c., when the humanism of Greece penetrated to the sanctuaries of ritual regicide in the Sudanese Upper Nile, the incident has been rendered in a style and mood of about the tenth century a.d.

No one who has studied the art of the fairy tale will doubt that such a folk-narrator of the twentieth century as Arach-ben-Hassul might faithfully communicate not only the plot but even the very style of a tale contrived in the Middle Ages. One need only read the folktales gathered by Jeremiah Curtin in the west of Ireland in the 1880s [Note 5] and compare them with Standish H. O’Grady’s translations of the tales of the Fianna and Irish saints from a series of fifteenth-century Irish manuscripts [Note 6] to be convinced. The ability of traditional story-tellers to hold their precious tales in mind to the minutest detail had already been noticed by the Brothers Grimm in the course of gathering their German collection. “Anyone believing that traditional materials are easily falsified and carelessly preserved, and hence cannot survive over a long period,” they wrote, “should hear how close the old story-teller always keeps to her story and how zealous she is for its accuracy; never does she alter any part i repetition, and she corrects a mistake herself, immediately she notices it. Among people who follow the old life-ways without change, attachment to inherited patterns is stronger than we, impatient for variety, can realize.” [Note 7]

It is entirely possible, therefore, that our tale of the destruction of Kash may stem from the period and genius of the great collection of Shehrzad.

But whence the tales of Shehrzad?

“The first who composed tales and made books of them,” wrote the tenth century Arab historian ‘Ali Abu-I Hasan ul- Mas’udi (d. c. 956 a.d.), “were the Persians. The Arabs translated them and the learned book them and composed others like them. The first book of the kind made,” his account continues, “was that called Hazār Afsāna (“Thousand Romances”), and its manner was on this wise. One of the kings of the Persians was wont, whenas he took a woman to wife and had lain one night with her, to put her to death on the morrow. Now he married a girl endowed with wit and knowledge, by name Shehrzad, and she fell to telling him tales and used to join the story, at the end of the night, with what should induce the king to spare her alive and question her next night of the ending thereof, till a thousand nights had passed over her. Meanwhile he lay with her, till he was vouchsafed a child by her, when she discovered to him the device she had practiced upon him. Her wit pleased him and he inclined to her and spared her life.” [Note 8]

It is usual to regard the nuclear idea of the Arabian Thousand Nights and One Night as Persian, even while recognizing that the collection was swollen to its present magnitude through contributions largely from Arabian Syria and Iraq, and Arabian Egypt. Frobenius, however, adds to this view a new and extremely interesting hypothesis based on his own collection of stories from the Sudan; namely, that there may have been a common source from which both the Persian tales and the Sudanese were derived, issuing from South Arabia, Hadramaut, that land “beyond the Eastern Sea” (the Red Sea) from which the fabulous slave Far-li-mas came to the court of the Nap of Napata.

“Is our Sudanese tale perhaps from an older rendition,” Frobenius asks, “not so worn at the edges and over-refined by a series of Indian, Persian, and late Egyptian transformations?” [Note 9]

Do we have, that is to say, in this elegant Sudanese narrative and in the celebrated Book of a Thousand Nights and One Night two variants of a single tradition, stemming from a land now largely a wilderness — but a wilderness with the ruins of ancient cities buried in its sands — today called properly Arabia deserta, but formerly Arabia felix?

“As we moved slowly along through the Red Sea in the year 1915,” Frobenius wrote in his account of the collection of his tales from Kordofan, “and I chatted by the hour with the Arab seamen, I learned of an apparently widely spread opinion, which may serve to clarify a number of problems in the present context. My informants maintained, stoutly and firmly, that all the tales of the Arabian Nights had first been told in Hadramaut and from there had been diffused over the earth. And the tale that they particularly stressed was ‘Sindbad the Sailor.’” [Note 10]

The question of the relationship of these two traditions has not — as far as I know — been resolved. It leads, however, to a second, no less fascinating question, which we are now able to answer i detail; and this, too, was proposed by Frobenius. It is the question, namely, of a possible historic or prehistoric background for this Sudanese Nights adventure. Can it be that the tale was not a sheer invention, but reflected in the glass of a late storytelling style some actual circumstance of the past?

The passage from Diodorus speaks for the possibility. Moreover, in the vast body of material assembled by Sir James G. Frazer in the twelve volumes of his monumental work The Golden Bough, we have evidence enough of the prevalence of a custom of ritual regicide throughout a large portion of the archaic world, associated — just as here — with a pattern of matrilineal descent. Among the Shilluk of the white Nile (a people now inhabiting precisely the region of our tale_ the custom of putting their king to death prevailed, according to Grazer, until only a few years ago. “It is said that the chiefs announce his fate to the king,” Frazer writes, citing the studies of C.G. Seligman, “and that afterwards he is strangled in a hut which has been specially built for the occasion.” [Note 11] Furthermore, in 1026 new evidence attesting to the nature of the destiny of the earliest kings and their courts was unearthed by Sir Leonard Woolley in his excavations of the so-called Royal Tombs of Ur, the city of the moon-god of ancient Sumer. His grim discovery is described in a later chapter. So, from what we now know, it can be said with perfect assurance that in the earliest period of the hieratic city state the king and his court were ritually immolated at the expiration of a span of years determined by the relationship of the planets in the heavens to the moon; and that our legend of Kash is, therefore, certainly an echo from that very deep well of the past, romantically reflected in a late story-teller’s art.

III. The King, and the Virgin of the Vestal Fire

The gruesome original sense of the relationship of the vestal virgin Sali’s role — as well as of Shehrzad’s in the Arabian Nights — to the archaic regicide comes out cruelly the moment we focus on the royal rituals traditionally practiced, until recently, in the Sudan.

Among the Shilluk, the priests, who were the only ones knowing the will of God (whom they called Nyakang), saw to it the king was killed after a term of seven years, or, if the crops or prosperity of the herds failed before that term, even earlier. The person of the king was sacred and could be seen by none but nobles. Not even his children could enter his dwelling. And when he stepped forth, surrounded closely by the nobles, criers sent the people flying to their huts. When the time arrived for his death, the high priest told the paramount noble, and the latter then assembled the members of his own class and apprised them, in silence, by a motion of his hand. The mystery had to be consummated on one of the dark nights that fall between the last and the first quarters of the moon, in the dry period before the first rain, and before the first seeds were sown. The charge was executed by the chief noble himself; none other should hear of it, know or speak of it; and there should be no weeping. The king was strangled and buried with a living virgin at his side. And, when the two bodies had rotted, their bones were gathered into the hide of a bull. A year later the new king was named, and on his predecessor’s grave cattle were speared to death by the hundred. [Note 12]

Of old, such customs were known to many peoples not only of the Upper Nile but of other parts of the Sudan as well; also in Mozambique, Angola, and Rhodesia. India and Indonesia too knew the rites; in fact, the most vivid example on record of an immolation of the sacred king is probably that in Duarte Barbosa’s Description of the Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century.

The god-king of the south Indian province of Quilacare in Malabar (and area having a strongly matriarchal tradition to this day) had to sacrifice himself at the end of the length of time required by the planet Jupiter for a circuit of the zodiac and return to its moment of retrograde motion in the sign of Cancer — which is to say, twelve years. When his time came, the king had a wooden scaffolding constructed and spread over with hangings of silk. And when he had ritually bathed in a tank, with great ceremonies and to the sound of music, he proceeded to the temple, where he paid worship to the divinity. Then he mounted the scaffolding and, before the people, took some very sharp knives and began to cut off parts of his body — nose, ears, lips, and all his members, and as much of his flesh as he was able — throwing them away and round about, until so much of his blood was spilled that he began to faint, whereupon he slit his throat. [Note 13]

“The essential motif lies in the timing of the death of the god,” writes Frobenius in his summary discussion of the archetype of the sacral regicide.

The great god must die; forfeit his life and be shut up in the underworld, within the mountain. The goddess (and let us call her Ishtar, using her later Babylonian title) follows him into the underworld and after the consummation of his self-immolation, releases him. The supreme mystery was celebrated not only in renowned songs, but also in the ancient new-year festivals, where it was presented dramatically: and this dramatic presentation can be said to represent the acme of the manifestation of the grammar and logic of mythology in the history of the world.

The whole idea was realized, furthermore, in a corresponding organization of the social institutions; the best preserved vestiges and echoes of which are to be found in Africa. Indeed, the ideas have been found preserved to this day in act, in the South African “Eritrean” zone (Mozambique, Angola, and Rhodesia). There, the king representing the great godhead even bore the name “Moon”; while his second wife was the Moon’s beloved, the planet Venus. And when the time arrived for the death of the god, the king and his Venus-spouse were strangled and their remains placed in a burial cave in a mountain, from which they were supposed then to be resurrected as the new, or “renewed,” heavenly spheres. And this, surely, must represent the earliest form of the mythological and ritual context. Already in ancient Babylon it had been weakened, in as much as the king at the New Year Festival in the temple was only stripped of his garments, humiliated, and struck, while in the marketplace a substitute, who had been ceremonially installed in all glory, was delivered to death by the noose….

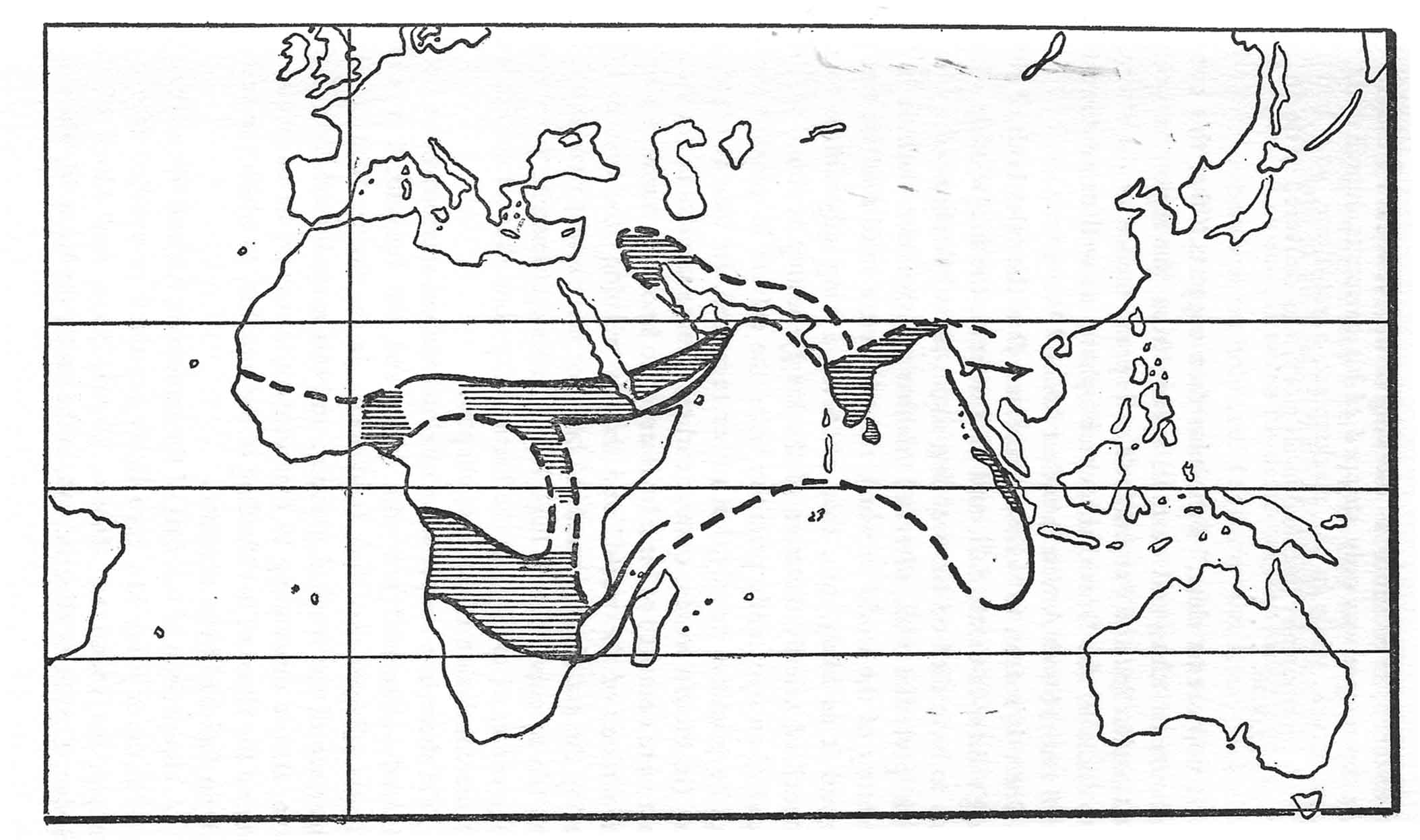

“It now seems clear,” Frobenius then suggests, “that this constellation of ideas and customs sprang from the region between the Caspian sea and Persian Gulf and spread thence southeastward into India in the Dravidian culture sphere, as well as southwestward across South Arabia into East Africa.” [Note 14]

Figure 6. Prevalence of ritual regicide. After Frobenius

There is reason to believe, therefore, that the tales both of the king’s sister-in-death, Sali, and of Shehrzad, the king’s bride who was to have died on her wedding night, must be echoes of a dim, dark past that was, after all, neither so dim nor dark in the memory of the world in which the tales were told. And we must regard it as likely, too, that whenever a king subordinate to a council of priestly dictators of the kingly destiny is found at the head of an apparently primitive tribe, the couture in question cannot be primitive exactly, but rather regressed. Its idea of correcting (in Plato’s words, quoted earlier) “those circuits in the head that were deranged at birth by learning to know the harmonies and revolutions of the world” and thereby winning “the best in life set by the gods before mankind both for this present time and for the life to come,” must have been derived, ultimately, from the high center of the idea of the hieratic city state that we considered at the conclusion of our last chapter.

Yet there is a deeper level of ritual human sacrifice to be considered — associated not with kings and the heavens, but with simple villagers and their food-plants, in the far-reaching culture province of the tropical gardens; and this may, indeed, be primitive. Before descending to that stratum, however, let us pause to attend the ritual of the kindling of the new fire, to which the vestal virgin Sali had been assigned.

A comparison of the rites of the numerous African tribes among whom the mystery has been lately practiced or recalled (for example, the Mundang, Haussa, Gwari, Nupe, and Mossi of the Sudan; Yoruba of Nigeria; and, in the south, the Ruanda, Wasegue, Wadoe, Wawemba, Walumbwe, Wahemba, Mambwe, Lunda, Kanioka, Bangala, and Bihe) reveals that when the king was dead all the fires in his domain were extinguished, and that during the period of no rule, between his death and the installation of his successor, there was no holy fire. The latter was ritually rekindled by a designated pubescent boy and virgin, who were required to appear completely naked before the new king, the court, and the people, with their fire-sticks; the two sticks being known, respectively, as the male (the twirling stick) and the female (the base). The two young people had to make the new fire and then perform that other, symbolically analogous act, their first copulation; after which they were tossed into a prepared trench, while a shout went up to drown their cries, and quickly buried alive. [Note 15]

We are entering, indeed, the realm of King Death, the great Chief Death.