Chapter 5 The Ritual Love-Death

I. The Descent and Return of the Maiden

A rite similar in conception to that of the young couple of the vestal fire, though functioning in the context of a more primitive mythology, is reported from the opposite margin of the Indian Ocean zone, seven or eight thousand miles from East Africa and the Sudan, among the Marind-anim of Dutch South New Guinea. The Swiss ethnologist Paul Wirz, in a two-volume work on the myths and customs of these head-hunting cannibals, [Note 1] tells of their gods — the Dema — who appear in the ceremonies, fabulously costumed, to enact again (or rather, not “again,” because time collapses in “ceremonial time” and what was “then” becomes “now”) the world-fashioning events of the “time of the beginning of the world.” The rites are performed to the tireless chant of many voices, the boom of slit-log drums, and the whirring of the bull-roarers, which are the voices of the Dema themselves, rising form the earth. The ceremonies continue for many nights, many days, uniting the villagers in a fused being that is not biological, essentially, but a living spirit — with numerous heads, many eyes, many voices, numerous feet pounding the earth — lifted even out of temporality and translated into the no-lace, no-time, no-when, no-where of the mythological age, which is here and now.

The particular moment of importance to our story occurs at the conclusion of one of the boys’ puberty rites, which terminates in a sexual orgy of several days and nights, during which everyone in the village except the initiates makes free with everybody else, amid the tumult of the mythological chants, drums, and the bull-roarers — until the final night, when a fine young girl, painted, oiled, and ceremonially costumed, is led into the dancing ground and made to lie beneath a platform of very heavy logs. With her, in open view of the festival, the initiates cohabit, one after another; and while the youth chosen to be last is embracing her the supports of the logs above are jerked away and the platform drops, to a prodigious boom of drums. A hideous howl goes up and the dead girl and boy are dragged from the logs, cut up, roasted, and eaten. [Note 2]

But what can be the sense of such a cruel game? and who are this annihilated girl and boy? What is the background of such rites, which are not frequent merely, but typical among the cannibal gardeners of the widely dispersed, equatorial villages?

As Professor Adolf Jensen of Frankfurt has pointed out, developing the broadly reaching cross-cultural theory first announced by Leo Frobenius in 1895-97, these rites are but the renditions in act of a mythology inspired by the model of death and life in the plant world. And they are the basal sacrament of a precisely definable prehistoric culture stratum still represented in tropical Africa and America, as well as in India, Indonesia, and Oceania. The unity of the broken field has not been explained; nor is it easy to imagine how it should be. Yet neither was it easy to understand the distribution of the animal known as the tapir (which is found both in the Malay region and in South and Central America, but nowhere between) until fossil forms in Miocene, Pliocene, and Pleistocene formations were found in Europe, China, and the United States of America, which made possible a reconstruction of the history of the animal’s diffusion. No biologist, previous to the discovery of these fossils, would have dreamed of suggesting that the New and Old World tapirs might have developed separately through parallel lines of evolution. And in the field of comparative mythology too, perhaps, it would be well not to formulate “scientific” conclusions before a full accounting is made.

The contemporary representatives of the prehistoric culture stratum of the cannibal gardeners dwell in tropical, usually jungle regions, sparsely populated, where the natural abundance of the plant world affords a convenient supply of food: coconuts, the pith of the sago palm, bananas and other fruits, and in California a variety of acorn. In addition, there is generally practiced an orderly, and often highly ritualized, cultivation of tubers: yams, for example, taro, and the sweet potato (rice and the other grains belonging, almost certainly, to a later stratum of culture). In general, the architecture is elaborately developed, usually set on piles, and frequently includes gigantic structures (two hundred yards or more in length) sheltering whole communities — which may number as many as a hundred persons. Bamboo is prominent and variously used. Among the beasts domesticated are the dog, the chicken (turkey, in America), and often the pig (throughout Melanesia and Indonesian) or the goat (in Africa). The arts of metalwork, weaving, and usually pottery are unknown, though imports of these goods are highly prized. And politically there are no great state confederations, kings, professional priests, or significant differentiations of labor (except, of course, along sexual lines); while the village as a cult community usually ranks higher than any tribal organization.

The prehistoric period to which the development of this particular style of life and thought should be assigned cannot be precisely identified. The archaeology of the problem is vague and has not been pressed very far. The characteristic artifacts are of extremely perishable materials: bamboo, pandanus leaves, shell and bone, feathers, palm fronds and logs, withies and beaten bark. Furthermore, the greater part of the region occupied has been the home of man for at least half a million years: the bones of Pithecanthropus erectus (c. 400,000 b.c.) were turned up in Java, and in Africa even earlier remains have been found in abundance. The cultural life of the area stands, indeed, as a kind of enduring though vanishing counterpoise to the more durably registered stone and metal ages of the temperate north. It is a culture-world in which the forms endure but not the materials in which they are rendered, whereas in the world of stone tools and metal it is the materials that last. The prehistoric origin of this primitive gardening syndrome must float enigmatically, therefore, in a loose relationship to the comparatively firm schedule of our various paleolithic, mesolithic, and neolithic ages. Jensen is inclined to refer it to the early neolithic, or perhaps even one step back, to the mesolithic. And if his vie is correct, we are viewing here a form of culture not far removed, in time of origin, from the proto-neolithic villages of the Near East.

It was in the course of an expedition to West Ceram (the next major island westward of New Guinea) that Professor Jensen discovered the myth that I present here as our first example from this cannibalistic culture stratum: that of the maiden Hainuwele, whose name means “Frond of the Cocopalm,” and who is one of three virgin Dema, highly revered among the tribes of West Ceram. The myth is this:

Nine families of mankind came forth in the beginning from Mount Nunusaku, where the people had emerged from clusters of bananas. And these families stopped in West Ceram, at a place known as the “Nine Dance Grounds,” which is in the jungle between Ahiolo and Varoloin.

Now there was a man among them whose name was Ameta, meaning “Dark,” “Black,” or “Night”; and neither was he married nor had he children. He went off, one day, hunting with his dog. And after a little, the dog smelt a wild pig, which it traced to a pond into which the animal took flight; but the dog remained on the shore. And the pig, swimming, grew tired and drowned, but the man, who had arrived meanwhile, retrieved it. And he found a coconut on its tusk, though at that time there were no cocopalms in the world.

Returning to his hut, Ameta placed the nut on a stand and covered it with a cloth bearing a snake design, then lay down to sleep. And in the night there appeared to him the figure of a man, who said: “The coconut that you placed upon the stand and covered with a cloth you must plant in the earth; otherwise it won’t grow.” So Ameta planted the coconut the next morning, and in three days the palm was tall. Again three days and it was bearing blossoms. He climbed the tree to cut the blossoms, from which he wished to prepare himself a drink, but as he cut he slashed his finger and the blood fell on a leaf. He returned home to bandage his finger and in three days came back to the palm to find that where the blood on the leaf had mingled with the sap of the cut blossom the face of someone had appeared. Three days later, the trunk of the person was there, and when he returned again in three days he found that a little girl had developed from his drop of blood. That night the same figure of a man appeared to him in dream. “Take your cloth with the snake design,” he said, “wrap the girl of the cocopalm in the cloth carefully, and carry her home.” So the next morning Ameta went with his cloth to the cocopalm, climbed the tree, and carefully wrapped up the little girl. He descended cautiously, took her home, and named her Hainuwele. She grew quickly and in three days was a nubile maiden. But she was not like an ordinary person; for when she would answer the call of nature her excrement consisted of all sorts of valuable articles, such as Chinese dishes and gongs, so that her father became very rich.

And about that time there was to be celebrated in the place of the Nine Dance grounds a great Maro dance, which was to last nine full nights, and the nine families of mankind were to participate. Now when the people dance the Maro, the women sit in the center and from there reach betel nut to the men, who from, in dancing, a large ninefold spiral. Hainuwele stood in the center at this Maro festival, passing out betel nut to the men. And at dawn, when the performance ended, all went home to sleep.

The second night, the nine families of mankind assembled on the second ground; for when the Maro is celebrated it must be performed each night in a different place. and once again, it was Hainuwele who was placed in the center to reach betel nut to the dancers; but when they asked for it she gave them coral instead, which they all found very nice. The dancers and the others, too, then began pressing in to ask for betel and she gave them coral. And so the performance continued until dawn, when they all went home to sleep.

The next night the dance was resumed on a third ground, with Hainuwele again in the center; but this time she gave beautiful Chinese porcelain dishes, and everyone present received such a dish. The fourth night she gave bigger porcelain dishes and the fifth, great bush knives; the sixth, beautifully worked betel boxes of copper; the seventh, golden earrings; and the eighth, glorious gongs. The value of the articles increased, that way, from night to night, and the people thought this thing mysterious. They came together and discussed the matter.

They were all extremely jealous that Hainuwele could distribute such wealth and decided to kill her. The ninth night, therefore, when the girl was again placed in the center of the dance ground, to pass out betel nut, the men dug a deep hole in the area. In the innermost circle of the great ninefold spiral the men of the Lesiela family were dancing, and in the course of the slowly cycling movement of their spiral they pressed the maiden Hainuwele toward the hole and threw her in. A loud, three voiced Maro Song drowned out her cries. They covered her quickly with earth, and the dancers trampled this down firmly with their steps. They danced on till dawn, when the festival ended and the people returned to their huts.

But when the Maro festival ended and Hainuwele failed to return, her father knew that she had been killed. He took nine branches of a certain bushlike plant whose wood is used in the casting of oracles and with these reconstructed in his home the nine circles of the Maro Dancers. Then he knew that Hainuwele had been killed in the Dancing Ground. He took nine fibers of the cocopalm leaf and went with these to the dance place, stuck them one after the other into the earth, and with the ninth came to what had been the innermost circle. When he stuck the ninth fiber into the earth and drew it forth, on it were some of the hairs and blood of Hainuwele. He dug up the corpse and cut it into many pieces, which he buried in the whole area about the Dancing Ground — except for the two arms, which he carried to the maiden Satene: the second of the supreme Dema-virgins of West Ceram. At the time of the coming into being of mankind Satene had emerged from an unripe banana, whereas the rest had come from ripe bananas; and she now was the ruler of them all. But the buried portions of Hainuwele, meanwhile, were already turning into things that up to that time had never existed anywhere on earth — above all, certain tuberous plants that have been the principal food of the people ever since.

Ameta cursed mankind and the maiden Satene was furious at the people for having killed. So she built on one of the dance grounds a great gate, consisting of a ninefold spiral, like the one formed by the men in the dance; and she stood on a great log inside this gate, holding in her two hands the two arms of Hainuwele. Then, summoning the people, she said to them: “Because you have killed, I reuse to live here any more: today I shall leave. And so now you must all try to come to me through this gate. Those who succeed will remain people, but to those who fail something else well happen.”

They tried to come through the spiral gate, but not all succeeded, and everyone who failed was turned into either an animal or a spirit. That is how it came about that pigs, deer, birds, fish, and many spirits inhabit the earth. Before that time there had been only people. Those, however, who came through walked to Satene; some to the right of the log on which she was standing, others to the left; and as each passed she struck him with one of Hainuwele’s arms. Those going left and to jump across five sticks of bamboo, those to the right, across nine, ad from these two groups, respectively, were derived the tribes known as the Fivers and the Niners. Satene said to them: “I am departing today and you will see me no more on earth. Only when you die will you again see me. Yet even then you shall have to accomplish a very difficult journey before you attain me.”

And with that, she disappeared from the earth. She now dwells on the mountain of the dead, in the southern part of West Ceram, and whoever desires to go to her must die. But the way to her mountain leads over eight other mountains. And ever since that day there have been not only men but spirits and animals on earth, while the tribes of men have been divided into the Fivers and the Niners. [Note 3]

A related myth tells of the remaining divine maiden, Rabia, who was desired in marriage by the sun-man Tuwale. But when her parents placed a dead pig in her place in the bridal bed, Tuwale claimed his bride in a strangely violent manner, causing her to sink into the earth among the roots of a tree. The efforts of the people to save her were in vain: they could not prevent her from sinking even deeper. And when she had gone down as far as to the neck, she called to her mother: “It is Tuwale, the sun-man, who has come to claim me. Slaughter a pig and celebrate a feast; for I am dying. But in three days, when evening comes, look up at the sky, where I shall be shining upon you as a light.” That was how the moon-maiden Rabia instituted the death feast. And when her relatives had killed the pig and celebrated the death feast for three days, they saw for the first time the moon, rising in the east. [Note 4]

II. The Mythological Event

The leading theme of the primitive-village mythology of the Dema is the coming of death into the world, and the particular point is that death comes by way of a murder. The second point is that the plants on which man lives derive from this death. The world lives on death: that is the insight rendered dramatically in this image. Moreover, as we learn from other myths and mythological fragments in this culture sphere, the sexual organs are supposed to have appeared at the time of this coming of death. Reproduction without death would be a calamity, as would death without reproduction.

We may say, then, that the interdependence of death and sex, their import as the complementary aspects of a single state of being, and the necessity of killing — killing and eating — for the continuance of this state of being, which is that of man on earth, and of all things on earth, the animals, birds, and fish, as well as man — this deeply moving, emotionally disturbing glimpse of death as the life of the living is the fundamental motivation supporting the rites around which the social structure of the early planting villages was composed.

As Professor Jensen has observed, “Killing holds a place of paramount significance in the way of life both of animals and of men. Every day men must kill, to maintain life. They kill animals, and, apparently, in the culture here being considered the harvesting of plants also was regarded — quite correctly — as a killing….

“In this culture,” he continues,

killing is not an act of heroism, conceived in a spirit of warlike manliness. All of the details of the headhunt speak to thee contrary. in fact, if the actions of the headhunter were to be judged by heroic standards we should have to call him a coward. Nor, on the other had, is either the mythological first killing that was perpetrated on the holy moon-being or the repetition of that killing in the cult — whether in the village ceremonials or in the actions of the headhunt — “murder,” in the sense of a criminal act meriting punishment, as Cain’s slaying of Abel would appear to have been. It is true that the first killing brought about a complete transformation of human life in the time of the beginning, and that in the myths this is occasionally represented in terms of a crime and its punishment: for, psychologically, a certain sense of guilt cannot be separated from the act of killing, any more that from that of begetting. Yet the mere fact that a repetition of the deed is a sacred obligation placed upon mankind makes it impossible to call it murder in the full sense of the word. Guilt and heroism do indeed appear in some of the mythological representations of the episodes, but are certainly not essential to the basic context — which cannot but have been much more elementary. The closest analogy is to be found, according to my opinion (he then suggests), in the world of the beasts f prey. We do not think either of heroism or of murder when considering their manner of killing, but only of the primal force of nature. And there is actually an indication of this parallelism in the appearance of spirits resembling beasts of prey in the ceremonies of the men’s secret societies and puberty rites, as well as in the express statement of the people of West Ceram that they derived their ritual of the headhunt from a bird of prey.

But all of this touches only the problem of the psychological attitude toward killing. that killing should have assumed such a prominent position in the total view of the world in this culture sphere, I should like to refer quite specifically to the occupation of these people with the world of the plants. There was here revealed to mankind, in some measure, a new field of illumination. For the plants were continually being killed through the gathering of their fruits, yet the death was extraordinarily quickly overcome by their new life. Thus there was made available to man a synthesizing insight, relating his own destiny to that of the animals, the plants, and the moon. [Note 5]

And so, once again, as in the instance of the cosmic imagery of the hieratic city state, we have an intellectual, emotionally toned insight as the fundamental inspiration of a cult that became basic to a sociology. There is no way, in sheerly economic terms, to account for the phenomenology of a primitive social system in which a tremendous proportion of the time and energy is given to activities of an elaborate ritual nature. The rites are expected to afford economic well-being and social harmony; that is true. Yet their inception cannot be attributed to an economic insight or even to a social need. Groups of a hundred souls or so do not require the murder of their own finest sons and daughters to enable them to cohere. This flowering of rites derived from a cosmic insight — and one of such force that the whole sense, the formal structuring principle of the universe, seemed for a certain period of human history to have been caught in it.

The rites were representations of this accord, in a way comparable to those formulae of modern physics through which the modes of operation of inscrutable cosmic forces become not only accessible to the mind but also susceptible to control. They function both for man’s enlightenment and for the furtherance of his aims. they are physical formulae; written, however, not in the black on white of, say, an E = mc2, but in human flesh. And the individuals rendering it are not individuals any more but epiphanies of a cosmic mystery and, as such, taboo — hence ceremonially decorated, and symbolically, not humanly, regarded and treated.

The harmony and well-being of the community, its coordination with the harmony and ultimate nature of the cosmos of which it is a part, and the integration of the individual, in his thought, feeling, and personal desires, with the sense and essential force of this universal circumstance, can be said, therefore, to be the fundamental aim and nature of the ceremonial. And in a society of the sort here being considered everyone is more or less deeply implicated in the context of the ceremonial in every moment and phase of his life.

Let us say, then, to summarize, that a mythological image, the mythological formula, is rendered present, here and now, in the rite. Just as the written formula, E = mc2, here on this page, is not merely a reference to the formula that Dr. Einstein wrote on another piece of paper somewhere else, but actually that formula itself, so likewise are the motifs of the rite experienced not as references but as presences. They render visible the mythological age itself. For the festival is an extension into the present of the world- creating mythological event through which the force of the ancestors (those eternal ones of the dream) became discharged into the rolling run of time, and where what then was ever present in the form of a holy being without change now dies and reappears, dies and reappears — like the moon, like the yam, like our animal food, or like the race.

The divine being (the Dema) has become flesh in the living food-substance of the world: which is to say, in all of us, since all of us are to become, in the end, food for other beings. This is the nuclear idea of the killed Dema, who is the source of our good and of our food. A number of infantile motifs have been enlisted in the rendition, but the idea itself cannot be called infantile. It is, in fact, a new insight, fostering not a return to infancy but a willed affirmation of man’s fate and of the ruthless nature of being, to which we, today, with our much more sensitive, humanized, and humanistic responses of revulsion, may be said to be reacting in the more childish way. The qualm before the deed of life — which is that of dealing death — is precisely the human crisis here overcome. The beast of prey deals death without knowledge. Man, however, has knowledge, and must overcome it to live. Among the primitive hunting societies the way was to deny death, the reality of death, and to go on killing as willing victims the animals that one required and revered. But in the planting societies a new insight or solution was opened by the lesson of the plant world itself, which is linked somehow to the moon, which also dies and is resurrected and moreover influences, n some mysterious way still unknown, the lunar cycle of the womb.

Through modern science mythology has been refuted in practically all its details; yet in its primary insight into the presence and operation of common laws including human life as well as the kingdoms of the animals, plants, and heavenly spheres — it announced not only the main theme but also the child source of the fascination of science, and perhaps of life itself. Moreover, when the will of the individual to his own immortality has been extinguished — as it is in rites such as these — through an effective realization of the immortality of being itself and of its play through all things, he is united with that being, in experience, in a stunning crisis of release from the psychology of guilt and mortality. Among the tropical planters the rendition of this fundamentally religious experience was effected through rites of the kind that we have observed.

And I think it may be said that if one of the chief problems of man, philosophically, is that of becoming reconciled, in feeling as well as in thought, to the monstrosity of the just-so of the world, no more telling initiatory lesson than that of these rites could have been imagined. As Professor Jensen has pointed out, the number of lives offered up in such rites is far less, proportionately to the population, than that sacrificed in our own cities in the traffic accidents. However, among ourselves such deaths are thought of and experienced generally as a consequence of human fallibility, even though their incidence is statistically predictable. In the primitive species rather that on that of the individual, what for us is “accident” is placed in the center of the system — namely, sudden, monstrous death — and this becomes therewith a revelation of the inhumanity of the order of the universe. And in addition, what is thus revealed is not simply the monstrosity of the just-so of the world, but this just-so as a higher reality than that normally sensed by our unalerted faculties: a god-willed monstrosity in being, and retaining its form of being only because a divinity (a Dema) is actualizing itself in the entire display. [Note 6]

Mythology, we may conclude, therefore, is a verification and validation of the well-known — as monstrous. It is conceived, finally, not as a reference either to history or to the world-texture analyzed by science, but as an epiphany of the monstrosity and wonder of these; so that both they and therewith ourselves may be experienced in depth.

And in the sacrifices through which the major themes of such a mythology are made manifest and present there is no sense of do ut des: “I give that thou mayest give.” These are not gifts, bribes, or dues rendered to God, but fresh enactments, here and now, of the god’s own sacrifice in the beginning, through which he, she or it became incarnate in the world process. Moreover, all the ritual acts around which the village community is organized, and through which its identity is maintained, are functions and partial revelations of this immortal sacrifice. And finally, its would seem evident that something of this primitive yet profoundly conceived mythology must underlie the larder, celestially oriented constellation that we have already noted in tour view of the hieratic city state.

In a mythologically oriented primitive society, such as those of the Marind-anim and West Ceramese, every aspect of life and of the world is linked organically to the pivotal insight rendered in the mythology and rituals of the age of the Dema. Those pre-sexual, pre-mortal ancestral beings of the mythological narrative lived the idyl of the beginning, an age when all things were innocent of the destiny of life in time. But there occurred in that age an event, the “mythological event” par excellence, which brought to an end its timeless way of being and effected a transformation of all things. Whereupon death and sex came into the world as the basic correlates of temporality.

Furthermore — and in contrast to our contemporary evolutionary view of the unfolding of forms in time — the mythological notion was of a single, unique, and critical moment of definitive precipitation at the close of the paradisial age and opening of the present, when all things were given precisely the forms in which we see them today: the animals, the fish, the birds, and the plants in their various species, as well as the spirits and the ritual customs of the group. In the Book of Genesis we find much the same idea. But in the primitive version of the mythological event (which is represented in the Book of Genesis in inverted order, Cain’s murder of Abel following, instead of preceding, our first parents’ eating of the fruit) one does not feel that mankind was cut off as a result of the killing of the Dema Hainuwele. On the contrary, the Dema, through man’s act of violence, was made the very substance of his life.

Something of the sort can be felt in the Christian myth of the killed, buried, resurrected, and eaten Jesus, whose mystery is the ritual of the altar and communion rail. But here the ultimate monstrosity of the divine drama is not stressed so much as the guilt of man in having brought it about; and we are asked to look forward to a last day, when the run of this cosmic tragedy of crime and punishment will be terminated and the kingdom of God realized on earth, as it is now in heaven. The Greek rendition of the mythology, on the other had, remains closer to the primitive view, according to which there is to be no end, or even essential improvement, for this tragedy (as it will seem to some) or play (as it appears to the gods). The sense of it all — or rather, nonsense of it all — is to be made evident forever in the festivals and monstrous customs of the community itself; but is evident also — and forever — in every part and moment of the universe, for those who have been taught by way of the rites to see and to know the world as it truly is.

III. Persephone

The number of details shared by the Greek mythology of Demeter, Hekate, and Persephone with the Indonesian myths and rites of Satene, Rabia, and Hainuwele is too great to have been the consequence either of chance or of what Sir James G. Frazer has plausibly called “the effect of similar causes acting on the similar constitution of the human mind in different countries and under different skies.” [Note 7] Like her child, the killed and eaten yet resurrected god of bread and wine, Dionysos (whose mythology we have already compared with the boys’ rites of Central Australia). Persephone — who was known also as Kore, “the maiden” — was conceived of Zeus. Her mother was Demeter, the Cretan goddess of agriculture and the fruitful soil. And the maiden was playing, we are told, [Note 8] in a meadow, culling flowers with the daughters of Okeanos, god of the all-embracing sea, when she spied a glorious plant with a hundred blossoms spreading its fragrance all about, which had been sent up expressly to seduce her by the goddess Earth (Gaia), at the behest of Hades, the lord of the underworld. So that when she hurried to pluck its flowers the earth gaped and a great god appeared in a chariot of gold, who carried her down into his abyss despite her cries. The god was Hades, lord of the underworld, and in the land of the dead she became his queen.

Persephone’s cries had been heard only by Demeter, her mother, and Hekate, a goddess of the moon. But when the mother, bereaved, sought to trace her daughter, she found that her footprints had been obliterated by those of a pig. For it had chanced — most curiously — that at the time of Persephone’s abduction a herd of pigs had been rooting in the neighborhood; and the swineherd’s name, Eubouleus, means “the giver of good counsel” and was in earlier times an appellation of the god of the underworld himself. Furthermore, when the earth opened to receive Persephone those pigs fell into the chasm too, and that, we are told, is why pigs play such a role in the rites of Demeter and Persephone. “Originally, we may conjecture,” Grazer comments in his discussion of this matter, “the footprints of the pig were the footprints of Persephone and of Demeter herself.” [Note 9]

In a festival celebrated in memory of the sorrows — and later joy — of Demeter and Persephone, suckling pigs were offered in a manner suggestive not only of an earlier human sacrifice but of one precisely of the gruesome kind that we have observed in Africa and among the Marind-anim of Melanesia. The Greek festival, called Thesmophoria, was exclusively for women, and, as Jane Harrison has demonstrated in her Prolegomena to the study of Greek Religion, [Note 10] such women’s rites in Greece were pre-Homeric; that is to say, survivals of the earlier, so-called Pelasgian period, when the hieratic bronze-age civilizations of Crete and Troy were in full flower and the warrior gods, Zeus and Apollo, of the later patriarchal Greeks had not yet arrived to reduce the power of the great goddess. The women fasted for nine days in memory of the nine days of sorrow of Demeter as she wandered over the earth, holding a long, staff-like torch in either had. Demeter met the moon-goddess Hekate, and together they proceeded to the sun-god, Phoebus, who had seen the maid abducted and could tell them where she was; after which Demeter, in wrath and grief, quit the world of the gods. As an old woman, heavily veiled, she sat for days by a well known as the Well of the Virgin. She served as nurse in a kingly household near Eleusis, which city then became the greatest sanctuary of her rites in Greece. and she cursed the earth to bear no fruit, either for man or for the gods, for a full year — until, when Zeus and all the deities of Olympus had come to her in vain, one after another, begging her to relent, Zeus at last caused Persephone to be released. She had eaten, however, a seed of the pomegranate in the world below and, as a consequence, would now have to spend one-third of each year with Hades. embraced and accompanied by both her mother and the goddess Hekate, she returned to Olympus in glory, and, as though by magic, the fields were covered again with flowers and the life-giving grain.

The seed-time festival of the Thesmophoria lasted three days, and the first day was named the Kathodos (downgoing) and Anodos (upcoming), the second Nesteia (fasting), and the last Kalligeneia (fair-born or fair-birth); and it was during the first day that the suckling pigs were thrown, probably alive, into an underground chamber called a megara, where they were left to rot for a year, the bones from the year before being carried up to the earth again and placed upon an altar. Figures of serpents and human beings made of flour and wheat were also thrown into the chasm, or “chamber,” at this time. “And they say,” writes the ancient author to whom we owe our knowledge of this matter, [Note 11] “that in and about the chasms are snakes which consume the most part of what is thrown in; hence a rattling din is made when the women draw up the remains and when they replace the remains by those well-known images, in order that the snakes which they hold to be the guardians of the sanctuaries may go away.”

The rites were secret; hence little has been told of them. However, in the widely celebrated and extremely influential mysteries of Eleusis, where the Kathodos-and-Anodos of the maiden Persephone was again the central theme, pigs were again important offerings. And there, moreover, a new motif appeared; for the culminating episode in the holy pageant performed in the “hall of the mystics” at Eleusis, representing the sorrows of Demeter and the ultimate Anodos or return of the maiden, was the showing of an ear of grain: “that great and marvelous mystery of perfect revelation, a cut stalk of grain,” as the early Christian bishop Hippolytus described it [Note 12] — forgetting for the nonce, apparently, that the culminating revelation of his own holy mass was a lifted wafer of bread made of the same grain.

Figure 7. Kore as a sheaf of grain

What could have been the meaning of such a simple act as the lifting of a cut stalk of grain?

What is the meaning of the elevated host of the mass?

As in the play-logic, or dream-logic, of any traditional religious pageant, the sacred object is to be identified, at least for the moment of the ceremony, with the god. The cut stalk is the returned Persephone, who was dead but now liveth, in the grain itself.

A bronze gong was struck at this moment, a young priestess representing Kore herself appeared, and the pageant terminated with a paean of joy. [Note 13]

Between the primitive Indonesian cycle and this cherished, highly regarded classical mystery, through which the Greek initiate learned (as a grave-inscription lets us know) that “death was not an evil, but a blessing,” [Note 14] the range of accord includes not only a number of surprisingly minute details, but also every one of the major themes. In fact, at every turn a fresh constellation of correspondences appears.

At the heart of both mythologies there is a trinity of goddesses identified with the local food plants, the pig, the underworld, and the moon, whose rites insure both a growth of the plants and a passage of the soul to the land of the dead. In both the marriage of the maiden goddess or Dema is equivalent to her death, which is imaged as a descent into the earth and is followed, after a time, by her metamorphosis into food: in the primitive cycle, the yam; in the classical, the grain. The women of the Greek Thesmophoria, furthermore, placed figures of flour and wheat, representing snakes and human beings, in the megara, together with the pigs; the pigs being left until the flesh rotted, when their bones were brought up and revered as relics, while the figures of wheat were consumed by snakes. And a clatter of noise, rationalized as a ruse to drive away the serpents, accompanied the placement of the pigs and cakes underground.

The ritual is related, trait by trait, to that of the youths and maidens murdered amid an uproar of drums, but has been revised to accord with the new attitude toward human sacrifice that in “The Legend of the Destruction of Kash” was seen to have reached from Greece even to the Sudan, by way of the long finger of the Nile. Frazer, in The Golden Bough, supplies many instances of substitutions of just this kind, and shows, moreover, that cakes in human form have been sacramentally consumed at planting and harvest festivals wherever grain has been ground into flour and baked. [Note 15] So that, in addition to the rest, it would now appear that the sacramental cannibalistic meal must have been, at one time, still another element common to the two cycles.

But why, along with the little pigs and the cakes in human form, were there also cakes in the form of a serpent? Why not living serpents? Or why not pigs of flour?

Greek mythology knew many stories of the maiden given to the serpent — or saved by a timely heroic appearance. For example, when Perseus, flying back on his winged sandals from his conquest of Medusa, was speeding through the air over Ethiopia, he spied, below, a lovely princess chained by her arms to a rough cliff beside the sea; “and save that her hair gently stirred in the breeze,” we read in Ovid’s account of the event, “and that warm tears were trickling down her cheeks, he would have thought her a marble statue.” [Note 16] There came, however, a loud roar from the sea, a monstrous serpent loomed, breasting the waves, and the princess shrieked. But when the great beast, coming toward the maiden like a swift ship, was as far from the cliff as the space through which a Balearic sling can send its whizzing bullet, lo! like an eagle Perseus swooped down with his sword and there ensued a prodigious tumult — the monster rearing, striking, plunging, and belching water mixed with purple blood, until the sword dealt, finally, the blow of the matador and the serpent died.

The name of this rescued princess was Andromeda, and her kingly father, Cepheus, governed Ethiopia, which, as we know from “The Legend of the destruction of Kash,” was the kingdom eastward of Napata, not far from the seat of the rescue of the maiden Sali by the magic of the tongue of Far-li-mas; or from the villages of the present Shilluk of the upper Nile, whose kings were ceremonially strangled and buried with living virgins at their sides, and when the flesh of the two bodies rotted, the bones were gathered into the hide of a bull.

Could Persephone ever have been pictured in this manner, as offered to a serpent, so that the figures of wheaten flour might have represented such a version of her tale? Indeed she could and indeed they might! For have we not already been told that she was playing in a meadow, culling flowers with the daughters of Okeanos, god of the all-embracing sea? But Okeanos, precisely, is the great serpent, Ocean, biting his tail, who surrounds the world. He supports it, also, in the form of the waters of the abyss and consequently is a counterpart of Hades — who, however, in the later, anecdotal developments of Greek mythology has acquired a separate character of his own. The serpent and human figures of wheaten flour not only may have been but simply must have been Hades and Persephone. And we must notice also that since Persephone was the great serpent’s bride she must have been able to assume the form of a serpent as well as that of a pig. Such metamorphoses are all part of the game of goddesses. We all know well enough the classical motif of the two serpents intertwined, which has become the symbol of the medical profession, the priesthood of the well-being that is the boon of the waters of the abyss, which waters flow as sap in the health-giving herbs and as the blood of life in our own healthy bodies.

The figures of wheaten flour, therefore, represent the personages of the myth; and the sacrificed pigs, sacrificed instead of human beings, represent the participation of the living in the mystery, which, though it was one of the mythological age, in the lives and rites of men is many. Consequently the victim is simultaneously one and many: one in its character as Dema, the mythological maiden; but many in the personal life-offerings of each. The logical principle involved is that of the logic of dream and play, where as we have already remarked, A is B and B is C: the Dema is the pig and the pig is man, true god and true man.

The legend of Hainuwele too, contains an unmistakable hint of an earlier version, featuring the serpent, in the painted snake on the cloth in which the little girl, “Frond of the Cocopalm,” was wrapped when carried from the tree, and in which the coconut taken from the dead boar had earlier been left standing overnight. The incongruous device of the boar’s leap into and drowning in the lake, followed by Ameta’s discovery of a coconut hooked to its tusk, as well as the unexplained mystery of the voice that spoke to Ameta in his dream, letting him know what he was to do, suggest very strongly that some earlier form of the myth has been adjusted to a secondary reading, in which a sacrificed pig, and not a supernatural snake, should preponderate, very much as in the mythology of Persephone and Demeter.

The structure of the earlier formula is examined in the next section; we may say here only, in summary of the foregoing findings, that the Greek and Indonesian myths examined have revealed not only a shared body of ritualized motifs but also signs of a shared past, an earlier stratum of their common story, in which a snake and not a pig played the animal part. And the fact that (one way or another) the two cycles were not merely linked remotely by a long, tenuous thread, but established on a broad, common base is made evident by a baffling series of further likenesses.

For example, in both mythologies the numbers 3 and 9 were prominent. We know, also, that is the Greek rites of the goddess — and of her dead and resurrected daughter Persephone, as well as of her dead and resurrected grandson Dionysos — the choral chant, the boom of the drum, and the hum of the bull-roarer were used just as in the rites of the cannibals of Indonesia. We recognize the labyrinth theme in both traditions, associated with the underworld and rendered in the figure of a spiral: in Greece, as well as Indonesia, choral dances were performed in this pattern. The reference in the Indonesian myth to Ameta’s desire to prepare a drink for himself from the blossoms of the cocopalm suggests a moon-animal complex that would correspond nicely with the formula in the archaic Mediterranean culture. And finally, is not the figure of Demeter, at the time of her departure in wrath from Olympus, bearing in each had a long, staff-like torch, comparable to Satene standing at the labyrinthine gate, telling the people of the mythological age that she is about to leave them, and holding in each hand an arm of Hainuwele?

There can be no doubt that the two mythologies are derived from a single base. The fact was recognized some time ago by the classical scholar Carl Kerenyi, [Note 17] and his argument has been supported since by Professor Jensen, the ethnologist chiefly responsible of the collection of the Indonesian material. [Note 18]

Are we to think, then, of the early grain-growing, stock- breeding villages of the Near east as adaptations to a temperate climate of a plant and animal economy derived, in principle, from the tropics? Or shall we say that the influence ran the other way: that the myths and rites of Indonesia represent transformations and regressions from a higher, less brutal system of thought originating in the proto- or basal neolithic villages of the Near East?

The argument is not yet closed; nor is all the evidence in. For the present, we can note simply that a continuum has been established, with its earliest firmly dated marker in the basal-neolithic stratum (c. 7500-3500 b.c.) in the Near East; a second field in the myths and rituals of the planting tribes of South and east Africa and the Sudan; a third (possibly) in Hadramaut; a fourth (certainly) in Malabar; and still another in Indonesia and, as we have seen, Melanesia and Australia. We must now range even farther and measure the reach of this mythological zone into the Pacific — and even, perhaps, the New World beyond.

IV. The Monster Eel

East in Indonesia, Melanesia, and Australia, throughout the island-studded triangle of Polynesia — which has Hawaii at its apex, New Zealand at one angle, and Easter Island at the other — the mythological image of the murdered divine being whose body became a food plant has been adjusted to the natural elements of an oceanic environment. Snakes, for example, are unknown in the islands. The role of the serpent has to be played, therefore, by the closest possible counterpart of the serpent, a monster eel. And the force of the role has been greatly increased — or rather, there is further evidence that in the myths of Hainuwele and Persephone the force of the role must have been greatly reduced. Paradoxically, then, it would appear that although we are moving eastward into the Pacific we are also coming closer to the biblical version of the mythological event through which death came into the world; and something rather startling is beginning to appear, furthermore, concerning the relationship of Mother Eve to the serpent, and of the serpent to the food tree in the Garden. The voluptuous atmosphere of the lush Polynesian adventure will be different, indeed, from the grim holiness of the rabbinical Torah; nevertheless, we are certainly in the same old book — of which, so to say, all the earliest editions have been lost.

The hero of the following version of the origin of the coconut is not the firs parent of mankind but the favorite trickster hero of Polynesian, Maui, who is roughly a counterpart of Hercules. He is generally known as the youngest of a company of brothers, who may vary in number from three (in Rarotonga) to six (in some of the versions form New Zealand); and among the best known of his many magical exploits were the fishing up of the islands form the bottom of the sea, snaring of the sun to slow it down in its passage, lifting of the sky to give his friends more room on earth, and theft of fire for his mother’s kitchen. Maui’s wife, the heroine of our story, is the passionate, completely unashamed beauty Hina (for, indeed, of what should she be ashamed?), who can be seen to this day in the markings of the moon, where she is sitting beneath a big ovava tree, beating out tapa cloth from its bark. [Note 19]

Here is the Tuamotuan version of Hina’s adventure: [Note 20]

Hina was originally the wife of the Monster Eel, Te Tuna (whose name means frankly, the Phallus), and the two lived together in their land beneath the sea until a day when Hina thought she had been there long enough. The place was intensely cold; and besides, she wanted now to be rid of Te Tuna. So she said to him: “You just stay here at home! I am going off to forage for us both.”

“And when shall you return?” he asked.

She answered: “I shall be gone for quite a while; because today and tonight will be spent traveling, tomorrow looking for food, and the next day and night cooking the food; but the following day and night will see me on the way home.”

“Then go,” he told her, “and stay away as long as necessary.”

So she set out on her journey. And she never paused to look for food, but went on to forage for a new lover. She went as far as to the land of the Male-principle (Tane) Clan, and when she had reached their place called out: “The eel-shaped creature dwelling in this inland region rides manfully to passion’s consummation: Te Tuna dwelling in the sea out there is but insipid food. I am a woman to be possessed by an eel-shaped lover; a woman come all the long way hither to unite in the struggle of passion upon the shores of Raro-nuku (the Land-below) and of Raro-vai-i-o (the Land-of-penetrating waters); the first woman thus to come utterly without shame seeking the eel- shaped rod of love. I am the dark pubic patch pursuing the assuagement of desire. For the fame of your manly prowess, O men of the Clan of the Male Principle, reached me even in the world below. I have come to you by way of unnumbered shores — along sandy beaches. Arise, O Detumescent Staff! Be plunged in the consummation of love. I am this woman from afar, desiring you ardently, O men of the Male-principle Clan!”

But the men of the clan only shouted at her in answer: “There is the road: follow it, and deep going! We shall never take the woman of the Monster Eel, Te Tuna, lest we be slain. He would be here in less that a day.”

she continued on her way, and when she arrived at the land of the Penetrating-embrace (Peka) Clan, called out again, using the same words; but the men replied as had the others. She went on to the land of the Erect (Tu) Clan, and once again all happened as before. She came to the land of the Wonder-worker (Maui) Clan, where the call and response were again repeated. And then she approached the home of Maui’s mother, Hua-hega.

When Hua-hega saw Hina approaching, she said to her son, Maui: “Take that woman for yourself!”

And so Maui-tikitiki-a-Ataraga (Wonder-worker, the Tu-mid, begotten of Ascending Shadow) took Hina to wife; and they all lived in that place together. But very soon, everybody round about realized that Te Tuna’s wife had been taken by Maui, and they went to Te Tuna and told him.

“Your wife,” they said, ” has been carried off by Maui.”

“Oh, let him have that woman to lie upon!” Te Tuna answered

However, they returned to him so often, always harping on the same theme, that finally Te Tuna was roused to anger. He said to the people who kept coming to him with this chatter: “What, then, is this man Maui like?”

“He is actually a very small fellow,” they replied, “and the end of his phallus is quite lopsided.”

“Well — just let him get one glimpse of the soiled strip of loincloth between my legs,” Te Tuna boasted, “and he’ll go flying out of the way!” Then he said: “Go tell Maui that I am coming on an expedition of vengeance!” And he chanted a melancholy song of lamentation for his wife.

The people listened to the song and went to Maui. “Te Tuna,” they said, “is coming to get you on an expedition of vengeance.”

“Just let him come!” Maui said. But then he asked, “What sort of creature is he?”

“Ho!” they said. “A gigantic monster!”

“Is he as sturdy and strong as a tall, straight coconut tree?”

The people, wishing to mislead him, answered: “He is like a leaning coconut tree.”

Maui asked: “Is he always weak and bending?”

They answered: “His weakness is inherent.”

“Oho!” cried Maui. “Just let him catch one glimpse of the lopsided end of my phallus, and he’ll go flying out of the way!”

The days passed, and patiently Maui waited — he and his household, living all together. And on a certain day when the skies grew dark, thunder rolled and lightning flashed, the people were filled with fear; for they knew that this now must be the coming of Te Tuna: and they all blamed Maui. “This,” they said, “is the first time that one man has stolen the woman of another. We shall all be slain.”

Maui reassured them. “Just keep close together and we shall not be slain.”

Te Tuna presently appeared, and there were with him four companions: Pupu- vac-noa (Tuft-in-the-center), Maga-vai-i-e-rire (Noose-existing-in-woman), Porporo-tu-a-huaga (Testicles-set-in-the-scrotum), and Toke-a-kura (Clitoris- continuously-suffused). The Monster Eel stripped off his soiled loincloth and held it up in the sight of all, when at once a vast billowy surge reared up and roared landward from the sea. It came sweeping on, towering above the land, and Hua-hega shouted to her son Maui: “Be quick! Let your phallus be seen!”

Maui obeyed, and immediately the huge wave receded until the bed of the sea was laid bare and the monsters were piled high and dry on a reef. Then he proceeded to the place where they were stranded and struck down three. Toke- a-kura got away with a broken leg, while Te Tuna, himself, Maui spared.

Together, Maui and Te Tuna went to Maui’s home, where they lived in harmony until a day when Te Tuna said to Maui: “We shall have to fight a duel, and when one of us has been killed the other will take the woman for himself.”

“What sort of duel would you like it to be?” Maui asked.

And Te Tuna said: “We shall first engage in a contest in which each goes completely into the body of the other, and when that is over, I am going to kill you, take my woman, and return with her to my own land.”

“Let it be as you wish,” Maui agreed. Then he asked: “And who is to be the first?”

“I’ll begin,” the Monster Eel replied, and when Maui consented, Te Tuna stood up and commenced chanting his incantation:

The Orea-eel swings and sways,

The Orea-eel balances his head lower and lower:

He is a mighty monster who has come hither across the ocean from his distant isle.

Your phallus will urinate from fright!

The monster contracts, becoming smaller and smaller.

It is I, Te Tuna who now enter, O Maui, into you body!

And Te Tuna disappeared completely into Maui’s body, where he disposed himself to remain. However, after a long while, he came out again.

Maui had not been disturbed in the least. “Well, now it is my turn,” Maui said.

Te Tuna agreed and the Wonder-worker began to chant his own spell, thus:

The Orea-eel swings and sways,

The Orea balances his head lower and lower —

A small man stands erect upon the land —

Your phallus will urinate from fright!

The man contracts — becoming smaller and smaller.

It is I, Maui, who now enter, O Te Tuna, into your body!

Maui disappeared into Te Tuna’s body, and at once all the sinews of the Monster Eel were rent apart, so that he died. Whereupon Maui stepped forth and, cutting off Te Tuna’s head, bore it away, intending to give it to his grandfather. But his mother, Hua-hega, got hold of it and refused to give it up. She said to Maui: “Take the head and bury it beside the post in the corner of our house.” And so he took it, buried it as she had directed, and never gave it another thought.

Maui continued to go about his usual daily tasks and they all went on living together as before, until, one evening, when they were sitting in the corner of the house where the head of Te Tuna had been buried, Maui perceived that a new shoot had sprung up from the sand. He was amazed. Hua-hega, noticing his surprise, said to him: “Why are you surprised?” to which he answered: “the head of Te Tuna that I buried here in this corner of our house: why has it sprouted?”

Hua-hega then told him: “The plant growing beside you is a kind of coconut known as ‘husk of the sea-green color from the region of the gods,’ because it has arisen from the depths of the sea, to reveal to us the color of its own land. Take care of your precious coconut tree and you will find that it will provide us all with food.”

Maui plucked the fruit when it matured. The meat within was eaten by all, and the shell then was fashioned by Maui into a couple of bowls, to serve as drinking cups. And when all was done he danced and sang a boastful song in celebration of his own prowess and of the superiority in magic through which the Monster Eel’s head had become transformed into his food:

No more than a woman’s belt strap,

No more that a scurrying cockroach,

Was Tuna the Ancient One!

Bewitched with a sprig of mohio fern,

A leaf casting its spell upon a mere simpleton in the arts of enchantment!

What, indeed, did he bring against me?

Nothing at all!

“And that,” the tale concludes, “is the way the coconut was acquired as food for all the people of this Earth-world here above.”

The adventure, as here narrated, was taken down from the lips of Fariua-a- Makitua, an old chieftain of the island of Fagatu in the Tuamotu Archipelago, which is in the very middle of the Pacific, just east of the Society Islands and Tahiti. The old man had been a disciple in his youth of an earlier teacher, Kamake, who in his time had been regarded as the greatest of all the Tuamotuan sages. [Note 21] And I have presented this unadulterated version of the legend of Hina and the monster eel in extenso, not only because it renders authentically the moral atmosphere of the ancient Polynesian epics, but also because it may serve as an introduction to our later studies of magic the force of magic, and the power of erotic elements in primitive conjuring.

The narrative, as here recounted, is translated from a style of Polynesian recitative that suggests very strongly both the form and the atmosphere of the archaic ceremonials from which the Greek tragedy and comedy were developed in the sixth century b.c. Just as the Greek satyr-chorus sang and danced its strophe and antistrophe, turning and whirling in a labyrintine dance while the legend of the god or hero was being sung — so here. Captain Cook and the other early voyagers in the Pacific have described the great religious festivals where literally hundreds of dancers, in orderly files and rows, performed sacred hulas to the boom of drums, sonorous gourds, and organ-pipe bamboos thumped upon the ground, while the sacred chants of the heroes and the gods were sung in strophe and antistrophe by soloists and choruses of many voices. [Note 22] For example, Te Tuna’s melancholy chant of lament for the loss of Hina, when the people had convinced him that he should go to win her back, appeared, in the original, as follows:

I. First Voice

Kua riro

My loved one has been stolen from

me.

Second Voice

Te aroha i te

Grieving love for the

hoa ki roto i

wife stirs within

te manava;

the heart;

Chorus

— kua riro

— for she has become the mistress of another.

Matagi kavea mai e

The winds have brought the word

Kua riro.

That she has been stolen from me.

Ho atu….

We now set out….

II. First Voice

Ho atu matou ki Vavau,

We now set out for Vavau.

Second Voice

Kia higo i to hoa —

To see the loved one —

Chorus

— ku riro.

— who has become the mistress of another.

Matagi i aue e

Wailing, the very winds lament

Kua riro.

Her who has been stolen from me.

Te aroha….

Grieving love….

III. First Voice

Te aroha i to vahine

Grieving love for the wife

ki roto i to manava.

wells within the breast.

Second Voice

Kia kite taku mata

Would that my eyes

i te ipo —

again beheld the loved one —

Chorus

— kua riro.

— who has been stole from me; now clasped in the arms of another

Matagi i aue e.

Even the winds lament.

Te aroha i-i-i-i-e!

Bitter is my anguish and despair.

Farther along in this chapter we must look again at the highly complex but gradually clearing problem of the relationship of the early Pacific to the archaic Mediterranean traditions; but first let us enlarge our spectrum of the myths and tales of the Polynesian monster eel. We shall then be in a better position not only to analyze the variant versions of the myth in the Bible, but also to comprehend the reduced role of the serpent in the Greek Persephone and Indonesian Hainuwele version of the myth, with their stress on the ritual sacrifice of a pig. For one of the most important as well as illuminating aspects of the prehistoric perspective opened by a comparative study of myth rests in the problem of the pig’s taking on the role of the serpent as the sacred animal of the labyrinth — and after the pig the bull, and after the bull the horse.

In the course of its long history and longer prehistory of diffusion, the mythologem (or nuclear mythological image) of the origin of the food plant generated a broad series of mutually clarifying, yet strikingly different variants, each seeming to reveal some essential quality or aspect of what must once have been the primal form, yet none being definitely more eligible to be its representative than any of the rest. The picture can perhaps be compared to that of a number of sister and brothers, all representing a family type, yet none more authentically than the rest. And the more numerous the gathered examples, the more fascinating and tantalizing the comparison.

For instance: In the Friendly Islands (Tonga), it is told that a male child, Eel, was born to a human couple, who had also a pair of human daughters. Eel, living in a pool, sprang toward his sisters in eager affection, but they fled, and when he pursued they jumped into the sea and became two rocks that may be seen to this day off the shore of Tongatabu. Eel went on swimming, to Samoa, where he again took up life in a pool. But when a virgin, bathing there, became pregnant because of his presence, the people decided to kill him. He told the girl to ask the people to give her his head when he had been killed, and to plant it, which she did. And it grew into a new sort of tree, the coconut tree. [Note 23]

In Mangaia, one of the Cook Islands, the maiden’s name was Ina (a dialect variant of Hina), and she liked to bathe in a certain pool. But there was a great eel that swam past and touched her; this occurred again and again, and one time he grew off his eel form and stood before her as she bathed, a beautiful youth named Tuna (once again — Te Tuna_. Ina accepted Tuna as her lover, and he would always visit her in human form but become an eel when he went away. And then, one day, he told her that the time had come when he would have to depart form her forever. He would make one final visit the next day, in a great flood of water, in the form of an eel; when she should decapitate him and bury the head. Tuna came; Ina did as she had been told. And every day thereafter she visited the place of the buried head, until, at length, a green shoot appeared, which grew into a beautiful tree that i the course of time produced fruits, the first coconuts. And every nut, when husked, still shows the eyes and face of Ina’s lover. [Note 24]

Plant-origin stories conforming to this stereotype are common for the other food plants of Polynesia also. The breadfruit tree first appeared, for example, according to a legend told in Hawaii, when a man named Ulu, dwelling near the present city of Hilo, died of famine. He and his wife and a sickly baby boy whose life was endangered by the general scarcity of food, and the man, distracted, had gone in prayer to the temple at Puueo, to learn from the god what should be done.

Now the god of that temple was of a type known in Hawaiian as the mo’o: which is a word meaning “lizard,” or “reptile.” But the only reptile in Hawaii is a harmless, even affectionately regarded little lizard that scurries up and down the walls of people’s houses and clings like a fly to ceilings, trapping insects with its quick tongue. The manner in which the mythological system of the islands has magnified this innocuous creature to the proportions of a greatly dangerous divine dragon supplies one of the most graphic illustrations I know of a mythological process — seldom mentioned in the textbooks of our subject but of considerable force and importance nevertheless — to which the late Dr. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy referred as land-nāma, “land naming” or “land taking,” [Note 25] the features of a newly entered land are assimilated by an immigrant people to its imported heritage of myth. We have already noted the case of the role of the serpent assumed by an eel. We are now considering that of the same serpent role assumed by a harmless lizard. We might also have considered the manner in which the Pilgrim Fathers and pioneers of America established their New Canaans, Nazareths, Sharons, Bethels, and Bethlehems wherever they went. The new land, and all the features of the new land, are linked back as securely as possible to the archetypes — the spiritually, psychologically, and sociologically significant archetypes — of whatever mythological system the people carry in their hearts. And through this process the land is spiritually validated, sanctified, and assimilated to the image of destiny that is the fashioning dynamism of the people’s lives. We shall have plenty of occasion, throughout the following chapters, to observe the force of this principle in the shaping of symbols. The process has now been clearly announced to us by the monster eel and the noble mo’o of the mythologies of remote Polynesia.

To proceed, then, with the legend of the origin of the breadfruit: When the man, Ulu, returned to his wife from his visit to the temple at Puueo, he said, “I have heard the voice of the noble Mo’o, and he has told me that tonight, as soon as darkness draws over the sea and the fires f the volcano goddess, Pele, light the clouds over the crater of Mount Kilauea, the black cloth will cover my head. And when the breath has gone from my body and my spirit has carefully near our spring of running water. Plant my heart and entrails near the door of the house. My feet, legs, and arms, hide in the same manner. Then lie down upon the couch where the two of us have reposed so often, listen carefully throughout the night, and do not go forth before the sun has reddened the morning sky. If, in the silence of the night, you should hear noises as of falling leaves and flowers, and afterward as of heavy fruit dropping to the ground, you will know that my prayer has been granted: the life of our little boy will be saved.” And having said that, Ulu fell on his face and died.

His wife sang a dirge of lament, but did precisely as she was told, and in the morning she found her house surrounded by a perfect thicket of vegetation.

“Before the door,” we are told in Thomas Thrum’s rendition of the legend, [[Note 26]

on the very spot where she had buried her husband’s heart, there grew a stately tree covered over with broad, green leaves dripping with dew and shining in the early sunlight, while on the grass lay the ripe, round fruit, where it had fallen from the branches above. And this tree she call Ulu (breadfruit) in honor of her husband. The little spring was concealed by a succulent growth of strange plants, bearing gigantic leaves and pendant clusters of long yellow fruit, which she named bananas. The intervening space was filled with a luxuriant growth of slender stems and twining vines, of which she called the former sugar-cane and the latter yams; while all around the house were growing little shrubs and succulent roots, to each one of which she gave a appropriate name. Then summoning her little boy, she bade him gather the breadfruit and bananas, and, reserving the largest and best for the gods, roasted the remainder in the hot coals, telling him that in future this should be his food. with the first mouthful, health returned to the body of the child, and from that time he grew in strength and stature until he attained to the fulness of perfect manhood. He became a mighty warrior in those days, and was known throughout all the island, so that when he died, his name Mokuola, was given to the islet in the bay of Hilo where his bones were buried; by which name it is called even to the present time.

An important system of such myths and rites, folktales and folk customs, deriving from a nuclear concept of the reciprocities of death and life (both in the way of killing and consuming and in that of propagating and dying) has been identified throughout the broad belt of the tropical equatorial zone, from the West African Sudan, across the Indian Ocean, deep into Polynesia — indeed, all the way to Easter Island, where the concept is rendered in the image of a caught and eaten fish.

“Were is our ancient queen?” we read, for example, in a text supplied by a native informant, who was reading (or at least professing to read) one of the mysterious hieroglyphic tablet of Easter Island that are supposed to have been preserved there for generations. “I is known,” the reading continued, “that she was transformed into a fish that was finally caught in the still waters….Away, away, if you cannot name the fish: that lovely fish with the short gills that was brought for food to our Great King and was laid upon a dish that rocked this way and that.” [Note 27]

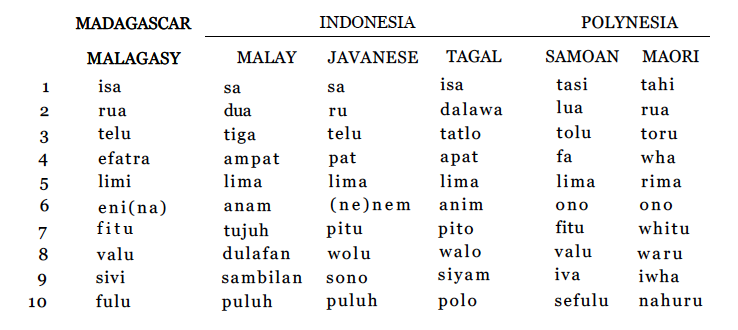

Many variants of the constellation are known, ranging from cannibalistic rites to poetical tales of parental love; but their kinship is clear. Nor is the vast diffusion difficult to credit. The Indian Ocean basin has been the watery highway for millenniums of cultural exchanges, back and forth, while Polynesia received its population largely from the Indonesian zone. A single language family, the Malayo-Polynesian, extends, in fact, all the way from Madagascar (just off the coast of southeast Africa) eastward to Easter Island (off the coast of Peru), and from New Zealand north to Formosa, and northeast to Hawaii. [Note 28] Such linguistic affinities indicate not only cultural and historic relationship, but also psychological homologies — and to such a degree that not even the most passionate supporter of a theory of parallel development would presume (I should think) to explain according to his cherished principles such a coincidence as that represented by the following ways of naming the numbers from one to ten: [Note 29]

The next step in this comparative study is to follow our theme to the shore of Peru and Mexico, the jungles of the Amazon, and the North American Plains.

IV. Parallelism or Diffusion?

The archaeology and ethnography of the past half-century have made it clear that the ancient civilizations of the Old World — those of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Crete, and Greece, India and China — derived from a single base, and the this community of origin suffices to explain the homologous forms of their mythological and ritual structures. As already noted, the beginnings of this epochal flowering have been traced to a neolithic base in the Near East, the first signs of which have been identified c. 7000-5500 b.c., and to the sudden appearance in approximately the same area, c. 3200 b.c., of a syndrome of priestly discoveries and crafts, including an astronomical calendar, the art of writing, a science of mathematics applied to and attempting to coordinate the measurements of space and time, and the conception of the wheel. Nowhere else in the world have any of the elements either of the neolithic assemblage or of higher civilization been identified at levels of anything like these depths; and the probability of a worldwide diffusion from the Near East of the basic arts, not only of all higher civilization, but also of all village living based on agriculture and stock-breeding, has consequently been argued with bountiful documentation, by a group of scholars of which Professor Robert Heine-Geldern of Vienna is today the leader.

As we have observed, there is still some question, however, as to the ultimate backgrounds of the neolithic. One has certainly to concede that the basic arts of higher civilization were derived, as far as the Afro-Eurasian hemisphere is concerned, from the now well established Near Eastern matrix. Nevertheless, with respect to the arts of planting and stock-breeding, the earliest neolithic villages of the Near East may represent simply one province of a considerably larger zone. The earliest horizon for the domestication of the pig in what may be termed, roughly, the Malayo-Polynesian sphere mas not yet been established; nor do we know how far back the primitive cultivation of the coconut, banana, and tuberous food plants should be placed. Therefore, though it may, on one hand, ultimately be found that most of the myths and rituals of the Malayo-Polynesian area should be interpreted as provincial to the Near Eastern proto-or basal neolithic, it may, on the other hand, ultimately appear that the reading should be run the other way. But in either case (and this point, I believe, no one acquainted with the facts now assembled would deny) the two developments were not separate; so that the progress of human culture in the Old World from the level of food-collection (hunting and root-gathering) to that of food-cultivation (planting and stock- breeding) has now to be studied as one very broadly spread yet single process.

With respect, however, to the New World there is still raging a violent, and even cantankerous scholarly conflict of opinion. For example, in a firm presentation of the point of view that has been favored by the majority of our North American schools of anthropology, we read:

In both hemispheres, man started from cultural scratch, as a nomadic hunter, a user of stone tools, a paleolithic savage. In both he spread over great continents and shaped his life to cope with every sort of environment. Then, in both hemispheres, wild plants were brought under cultivation; population increased; concentrations of people brought elaboration of social groupings and rapid progress in the arts. Pottery came into use, fibers and wools were woven into cloth, animals were domesticated, metal working began — first in gold and copper, then in the harder alloy, bronze. systems of writing were evolved.

Not only in material things do the parallels hold. In the New World as well as in the Old, priesthoods grew and, allying themselves with temporal powers, or becoming rulers in their own right, reared to their gods vast temples adorned with painting and sculpture. The priests and chiefs provided for themselves elaborate tombs richly stocked for the future life. In political history it is the same. In both hemispheres group joined group to form tribes; coalitions and conquests brought pre-eminence; empires grew and assumed the paraphernalia of glory.

These are astonishing similarities. And if we believe, as most modern students do,* that the Indian’s achievement was made independently, and their progress was not stimulated from overseas, then we reach a very significant conclusion. We can infer that human beings possess an innate urge to take certain definite steps toward what we call civilization. And that men also possess the innate ability, given proper environmental conditions, to put that urge into effect. In other words, we must consider that civilization is an inevitable response to laws governing the growth of culture and controlling the man-culture relationship. [Note 30]

Leo Frobenius, however, as early as 1903 was taking a precisely contrary view, one that has since been represented and developed chiefly by the European and South American scholars of the subject. Believing that the primitive planting villages of equatorial America were extensions eastward from Polynesia of a cultural style that he had already identified from the Sudan to Easter Island, he argued that the basic American hunting-culture continuum — which had been carried into the continent from northwestern Siberia, across Bering Strait, and had spread downward vertically from Alaska to Cape Horn — must have been struck horizontally by sea voyagers fro Polynesia and cut through, as by a wedge. “In our study of Oceania,” her wrote, “it can be shown that a bridge existed, and not a chasm, between America and Asia. It would be a contradiction to all the laws of the local culture of Oceania for us to assume that the Polynesians called a halt and turned back at Easter Island. And from Hawaii, furthermore, an often traveled bridge of wind currents leads to the Northwest Coast.” [Note 31]

The strongest and usual reply of the isolationists to every argument of the diffusionists was that the Polynesian migrations were late, far too late, to account for the invention of agriculture and the flowering of high civilization in the New World. The period of the great Polynesian migrations they placed between the tenth and fourteenth centuries a.d., and the earliest possible entry of man into that far-flung island world of the South Pacific not earlier that the fifth century a.d. [Note 32] Whereas all sorts of ancient dates were proposed for the earliest agricultural horizon in the New World: Spinden’s date, for example, of c. 4000 b.c., or Kroeber’s, c. 3000 b.c. [Note 33]

Actually, however, the earliest well-established date for American agriculture is only c. 1016 +/- 300 b.c., at a site on the northern coast of Peru called Huaca Prieta.* There, at the mouth of the Chicama Valley, a number of mounds excavated in the late 1940s yielded a beautiful series of stratified remains, four extremely significant samplings of which have been dated by the new radiocarbon (C-14) method as follows:

1. Sample No. 598: charcoal from bedrock-level fireplaces, 2348 +/- 230 b.c.

There was no evidence of agriculture on this level. The associated remains indicated the presence only of a primitive hunting, fishing, and food-gathering community.