The End of the Line

A few years ago Daina Taimina was reclining on the sofa at home in Ithaca, New York, where she teaches at Cornell University. A family member asked her what she was doing.

‘I’m crocheting the hyperbolic plane,’ she replied, referring to a concept that has mystified and fascinated mathematicians for almost two centuries.

‘Have you ever seen a mathematician do crochet?’ came the dismissive response.

The rebuff, however, made Daina even more determined to use handicraft in the course of scientific advancement. Which is just what she did, inventing what is known as ‘hyperbolic crochet’, a method of looping yarn that produces objects as intricate and beautiful as anything produced by the WI, and that has also contributed to an understanding of geometry in a way that mathematicians once never thought possible.

I’ll come shortly to a detailed definition of hyperbolic and the insights gleaned by Daina’s crochet models, but for the moment all you need to know is that hyperbolic geometry is an utterly counterintuitive type of geometry that emerged in the early nineteenth century in which the set of rules that Euclid laid out so carefully in The Elements are taken as being false. ‘Non-Euclidean’ geometry was a watershed for mathematics in that it described a theory of physical space that totally contradicted our experience of the world, and therefore was hard to imagine, but nevertheless contained no mathematical contradictions, and so was as mathematically valid as the Euclidean system that came before.

Later that century an intellectual breakthrough of similar significance was made by Georg Cantor, who turned our intuitive understanding of the infinite on its head by proving that infinity comes in different sizes. Non-Euclidean geometry and Cantor’s set theory were gateways into two strange and wonderful worlds, and I’ll visit them both in the following pages. Arguably, together they marked the beginning of modern mathematics.

Hyperbolic crochet.

The Elements, to recap from much earlier, is easily the most influential maths textbook of all time, having set out the basics of Greek geometry. It also established the axiomatic method, by which Euclid began with clear definitions of the terms to be used and the rules to be followed, and then built up his body of theorems from them. The rules, or axioms, of a system are the statements that are accepted without proof, so mathematicians always try to make them as simple and self-evident as possible.

Euclid proved all 465 theorems of The Elements with only five axioms, which are more commonly known as his five postulates:

1. There is a straight line from any point to any point.

2. A finite straight line can be produced in any straight line.

3. There is a circle with any centre and any radius.

4. All right angles are equal to one another.

5. If a straight line falling on two given straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two given straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which the angles are less than the two right angles.

When we get to number 5, something does not feel right. The postulates start briskly enough. The first four are easy to state, easy to understand and easy to accept. Yet who invited the fifth to the party? It is long-winded, complicated and not especially, if at all, self-evident. And it is not even as clearly fundamental: the first time The Elements requires it is for Proposition 29.

Despite their love of Euclid’s deductive method, mathematicians loathed his fifth postulate; not only did it go against their sense of aesthetics, they felt that it assumed too much to be an axiom. In fact, for 2000 years many great minds attempted to change the status of the fifth postulate by trying to deduce it from the other postulates so that it could be reclassified as a theorem instead of remaining as a postulate or axiom. But none succeeded. Perhaps the greatest evidence of Euclid’s own genius was that he understood that the fifth postulate had to be accepted without proof.

Mathematicians had more success with restating the postulate in different terms. For example, the Englishman John Wallis in the seventeenth century realized that all The Elements could be proved by keeping the first four postulates as they were but by replacing the fifth postulate with the following alternative: given any triangle, the triangle can be blown up or shrunk to any size so that the lengths of the sides stay in the same proportion to each other and the angles between the sides remain unaltered. While it was quite an insight to realize that the fifth postulate could be rephrased as a statement about triangles rather than a statement about lines, it did not resolve mathematicians’ concerns: Wallis’s alternative postulate was perhaps more intuitive than the fifth postulate, though perhaps only marginally so, but it still wasn’t as simple or self-evident as the first four. Other equivalents for the fifth postulate were also discovered; Euclid’s theorems still held true if the fifth postulate was substituted by the statement that the sum of angles in a triangle is 180 degrees, that Pythagoras’s Theorem is true, or that for all circles the ratio of the circumference to diameter is pi. Extraordinary as it might sound, each of these statements is mathematically interchangeable. The equivalent that most conveniently expressed the essence of the fifth postulate, however, concerned the behaviour of parallel lines. From the eighteenth century mathematicians studying Euclid began to prefer using this version, which is known as the parallel postulate:

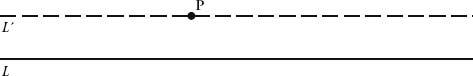

Ga line and a point not on that line, then there is at most one line that goes through the point and is parallel to the original line.

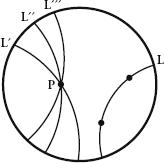

It can be shown that the parallel postulate refers to the geometry of two distinct types of surface, hinging on the phrase ‘at most one line’ – which is mathspeak for ‘either one line or no lines’. In the first case, illustrated by the diagram, for any line L and point P, there is only one line parallel to L (which is marked L’) that goes through P. This version of the parallel postulate applies to the most obvious type of surface, a flat surface, such as a sheet of paper on your desk.

The parallel postulate.

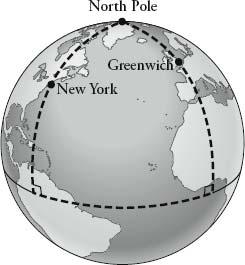

Now let’s consider the second version of the postulate, in which for any line L and point P not on that line there are no lines through P and parallel to L. At first it is hard to think on what type of surface this might be the case. Where on Earth…? On Earth is exactly where! Imagine, for example, that our line L is the equator, and imagine that point P is the North Pole. The only straight lines through the North Pole are the lines of longitude, such as the Greenwich Meridian, and all lines of longitude cross the equator. So, there are no straight lines through the North Pole that are parallel to the equator.

The parallel postulate provides us with a geometry for two types of surface: flat surfaces and spherical surfaces. The Elements was concerned with flat surfaces, so for 2000 years this was the main focus of mathematical enquiry. Spherical surfaces like the Earth were of less interest to theoreticians than they were to navigators and astronomers. It was only at the beginning of the nineteenth century that mathematicians found a wider theory that encompassed flat and spherical surfaces – and this happened only after they encountered a third kind of surface, the hyperbolic one.

One of the most determined aspirants in the quest to prove the parallel postulate from the first four postulates, and therefore show that it is not a postulate at all but a theorem, was Janós Bolyai, an engineering undergraduate from Transylvania. His mathematician father Farkas knew the scale of the challenge from his own failed attempts and implored his son to stop: ‘For God’s sake, I beseech you, give it up. Fear it no less than sensual passions because it too may take all your time and deprive you of your health, peace of mind and happiness in life.’ But Janós stubbornly ignored his father’s advice, and that was not his only rebellion: Janós dared to consider that the postulate might be false. The Elements was to mathematics what the Bible was to Christianity, a book of unchallengeable, sacred truths. While there was debate about whether the fifth postulate was an axiom or a theorem, no one had the temerity to suggest that it might actually not be true. As it turned out, doing so was the key to a new world.

The parallel postulate states that for any given line and a point not on that line there is at most one parallel line through that point. Janós’s audacity was to suggest that for any given line and a point not on the line, more than one parallel line passes through that point. Even though it was not at all clear how to visualize a surface for which this statement was true, Janós realized that eometry created by this statement, together with the first four postulates, was still mathematically consistent. It was a revolutionary discovery, and he recognized its momentousness. In 1823 he wrote to his father announcing that ‘Out of nothing I have created a new universe’.

Janós was probably helped by the fact that he was working in isolation from any major mathematical institution, and so was less indoctrinated by traditional views. Even after making his discovery, he opted not to become a mathematician. On graduating, he joined the Austro-Hungarian army, where he was reportedly the best swordsman and dancer among his colleagues. He was also an outstanding musician, and it is said that he once challenged thirteen officers to duels on the condition that upon victory he could play the loser a piece on his violin.

Unbeknownst to Janós, another mathematician in an outpost even more distant from the hubs of European academia than Transylvania was making similar advances independently, but he had his work rejected by the mathematical establishment. In 1826 Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, a professor at Kazan University in Russia, submitted a paper that disputed the truth of the parallel postulate to the internationally renowned St Petersburg Academy of Sciences. It was turned down, so Lobachevsky then decided to submit it for publication in the local newspaper Kazan Messenger, and consequently no one took any notice.

The greatest irony about the toppling of Euclid’s fifth postulate from the plinth of inviolable truth, however, is that several decades beforehand someone at the very heart of the mathematical establishment had indeed made the same discovery as Janós Bolyai and Nikolai Lobachevsky, yet this man had withheld his results from his peers. Quite why Carl Friedrich Gauss, the greatest mathematician of his day, decided to keep his work on the parallel postulate secret is not understood, although the received view is that he wanted to avoid getting embroiled in a feud about the primacy of Euclid with faculty members.

It was only on reading about Janós’s results, which were published in 1831 as an appendix in a book by his father Farkas, that Gauss revealed to anyone that he had also considered the falsity of the parallel postulate. Gauss wrote a letter to Farkas, an old university classmate, in which he described Janós as a ‘genius of the first order’, yet added that he was unable to praise his breakthrough: ‘For to praise it would be to praise myself. The entire content of the essay…coincide[s] with my own discoveries, some of which date back 30 to 35 years…I had intended to write all this down later so that at least it would not perish with me. It is therefore a pleasant surprise for me that I am spared this trouble, and I am especially glad that it is just the son of my old friend who takes precedence to me in this matter.’ Janós was distressed when he learned that Gauss had got there first. And when, years later, Janós learned that Lobachevsky had also preceded him, he became haunted by the ludricrous notion that Lobachevsky was a fictional character invented by Gauss as a cunning ruse in order to deprive him of the credit for his work.

Gauss’s final contribution to research on the fifth postulate came shortly before he died, when, already seriously ill, he set the title for the probationary lecture of one of his brightest students, 27-year-old Bernhard Riemann: ‘On the hypotheses that lie at the foundations of geometry’. The cripplingly shy son of a Lutheran pastor, Riemann at first had some kind of breakdown struggling with what he would say, yet his solution to the problem would revolutionize maths. It would later revolutionize physics too, since his innovations were required by Einstein to formulate his general theory of relativity.

Riemann’s lecture, given in 1854, consolidated the paradigm shift in our understanding of geometry resulting from the fall of the parallel postulate by establishing an all-embracing theory that included the Euclidean and non-Euclidean within it. The key concept behind Riemann’s theory was the curvature of space. When a surface has zero curvature, it is flat, or Euclidean, and the results of The Elements all hold. When a surface has positive or negative curvature, it is curved, or non-Euclidean, and the results of The Elements do not hold.

The simplest way to understand curvature, continued Riemann, is by considering the behaviour of triangles. On a surface with zero curvature, the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees. On a surface with positive curvature, the angles of a triangle add up to more than 180 degrees. On a surface with negative curvature, the angles of a triangle add up to less than 180 degrees.

A sphere has positive curvature. We can see this by considering the sum of the angles of the triangle in the following diagram, which is made by the equator, the Greenwich Meridian and the line of longitude 73 degrees west of Greenwich (which goes through New York). Both angles where the longitude lines meet the equator are 90 degrees, so the sum of all three angles must be more than 180. What type of surface has negative curvature? In other words, where are there triangles whose angles add up to less than 180 degrees? Pop open a pack of Pringles, and you’ll see. Draw a triangle on the saddle part of the potato crisp (possibly with some fine French mustard) and the triangle looks ‘sucked in’ compared to the ‘puffed out’ triangle we see on a sphere. Its angles are clearly less than 180 degrees.

Triangle on a sphere: sum of angles greater than 180 degrees.

Triangle on a Pringle: sum of angles less than 180 degrees.

A surface with negative curvature is called hyperbolic. So, the surface of a Pringle is hyperbolic. The Pringle, however, is only an hors d’oeuvre in understanding hyperbolic geometry since it has an edge. Show a mathematician an edge and he or she will want to go over it.

Consider it this way. It is straightforward to imagine a surface with zero curvature and no edge: for example, this page, flattened on a desk, and extended infinitely in all directions. If we lived on such a surface and we started walking in a straight line in any direction, we would never reach an edge. Likewise, we have an obvious example of a surface with positive curvature and no edge: a sphere. If we lived on the surface of a sphere, we could walk for ever and ever in one direction and never reach an edge. (Of course, we do live on a rough approximation of a sphere. If the Earth were totally smooth, with no oceans or mountains to block our way, for example, and we started walking, we would return to our point of departure and continue going in circles.)

Now, what does a surface with negative curvature and no edge look like? It cannot lSo, theike a Pringle, since if we lived on an Earth-sized Pringle and we started walking in one direction, we would always eventually fall off it. Mathematicians have long wondered what an ‘edgeless’ hyperbolic surface might look like – one on which we could walk as far as we wished without coming to the end of it and without it losing its hyperbolic properties. We know it must be always curving like a Pringle, so what about sticking lots of Pringles together? Sadly, this wouldn’t work since Pringles don’t fit together neatly, and if we filled in the gaps with another surface these new areas would not be hyperbolic. In other words, the Pringle allows us to envisage only a local area with hyperbolic properties. What is incredibly difficult to envisage – and stretches even the most brilliant mathematical minds – is a hyperbolic surface that goes on for ever.

Spherical and hyperbolic surfaces are mathematical opposites, and here is a practical example that shows why. Cut a piece out of a spherical surface, such as a basketball. When we squash the piece on the ground to make it flat it will either stretch or rip, since there is not enough material to spread out in a flat way. Now imagine we had a rubber Pringle. When we try to flatten it, the Pringle would have too much material and some of it would fold on itself. Whereas the sphere closes in on itself, the hyperbolic surface expands.

Let’s return to the parallel postulate, which provides us with a very concise way of classifying flat, spherical and hyperbolic surfaces.

For any given line and a point not on that line:

On a flat surface there is one and only one parallel line through that point.

On a spherical surface there are zero parallel lines through that point.*

We can understand intuitively the behaviour of parallel lines on a flat or on a spherical surface, because we can easily visualize a flat surface that goes on for ever and we all know what a sphere is. It is much more challenging to understand the behaviour of parallel lines on a hyperbolic surface, since it is not at all clear what such a surface might look like as it spreads to infinity. Parallel lines in hyperbolic space get further and further apart from each other. They do not bend away from each other, since for two lines to be parallel they must also be straight, but they diverge because a hyperbolic surface is constantly curving away from itself, and as the surface curves away from itself it creates more and more space between any two parallel lines. Again, this idea is totally mind-boggling, and it’s hardly surprising that, despite his genius, Riemann did not come up with a surface that had the properties he was describing.

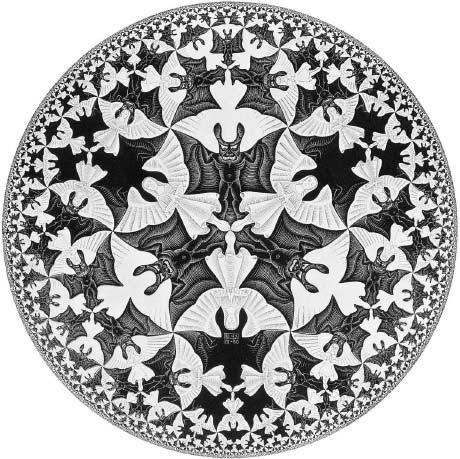

The challenge of visualizing the hlic plane galvanized many mathematicians in the final decades of the nineteenth century. One attempt, by Henri Poincaré, caught the imagination of M.C. Escher, whose famous Circle Limit series of woodcuts was inspired by the Frenchman’s ‘disc model’ of a hyperbolic surface. In Circle Limit IV, a two-dimensional universe is contained on the circular disc in which angels and devils get progressively smaller the closer they get to the circumference. The angels and devils, however, are not aware that they are getting smaller since as they shrink, so too do their measuring tools. As far as the inhabitants of the disc are concerned, they are all the same size and their universe goes on for ever.

Circle Limit IV.

The ingenuity of Poincaré’s disc model is that it illustrates beautifully how parallel lines behave in hyperbolic space. First, we need to be clear what straight lines are in the disc. In the same way that straight lines on a sphere look curved when represented on a flat map (for example, flight paths are straight, but look curved on a map), lines that are straight in the discworld also look to us like they are curved. Poincaré defined a straight line in the disc as being a section of a circle that enters the disc at right angles. Figure 1 overleaf shows the straight line between A and B, which is made by finding the circle that goes through A and B and that enters the disc at right angles. The hyperbolic version of the parallel postulate states that for every straight line L and a point P not on that line, there is an infinite number of straight lines parallel to L that pass through P. This is shown in figure 2, where I have marked three straight lines – L', L' ' and L' '' – that pass through P but are all parallel to L. (Two lines are parallel if they are both straight and never meet.) Each of the lines L', L' ' and L' '' are parts of different circles that enter the disc at right angles. By looking at the disc we can now see how it must be the case that there is an infinite number of straight lines that are parallel to L and that pass through P, since we can draw an infinite number of circles that enter the disc at right angles and pass through P. Poincaré’s model also helps us understand what it means for two parallel lines to diverge: L and L' are parallel but become further and further apart the closer they get to the circumference of the disc.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Poincaré’s discworld is illuminating, but only up to a point. While it provides us with a conceptual model of hyperbolic space, distorted through a rather strange lens, it does not reveal what a hyperbolic surface looks like in our world. The search for more realistic hyperbolic models, which had looked promising in the last decades of the nineteenth century, was dealt a blow by the German mathematician David Hilbert in 1901, when he proved that it was impossible to describe a hyperbolic surface using a formula. Hilbert’s proof was accepted by the mathematical community with resignation, since they concluded that if there was no way of describing such a surface with a formula, then such a surface must not actually exist. Interest in coming up with models for hyperbolic surfaces waned.

Which brings us back to Daina Taimina, whom I met at the South Bank, a riverside promenade of theatres, art galleries and cinemas in London. She gave me a brief summary of the history of hyperbolic space, which is a subject she has taught in her position as adjunct associate professor at Cornell. A consequence of Hilbert’s proof that hyperbolic space cannot be generated by a formula, she said, is that computers are unable to create images of hyperbolic surfaces because computers can only create images based on formulas. In the 1970s, however, the geometer William Thurston found a low-tech approach to be much more fruitful. He had the idea that you didn’t need a formula to make a hyperbolic model – all you needed was paper and scissors. Thurston, who in 1981 was awarded the Fields Medal (the supreme prize in maths) and who is now a colleague of Daina’s at Cornell, came up with a model made from sticking together horseshoe-shaped slivers of paper.

Daina used a Thurston model with her students but it was so fragile that it always fell apart, and she had to make a new one each time. ‘I hate gluing paper. It drives me crazy,’ she said. Then she had a brainwave. What if it were possible to knit a model of the hyperbolic plane instead?

Her idea was simple: start with a line of stitches, and then for each subsequent line add a fixed amount relative to the number of stitches on the line before. For example, adding an extra stitch for every two stitches on the line before. In this case, if you started with a line of 20 stitches, the second line would have 30 stitches (adding 10), the third line 45 stitches (adding 15), and so on. (The fourth line should have an extra 22.5 stitches, but since you can’t do half stitches you have to round up or down.) This, she hoped, would create a piece of fabric that became wider and wider – as if expanding out from itself hyperbolically. However, the knitting was too fiddly, since after any mistake she needed to unravel the whole line. So she swapped the knitting needles for a crochet hook. With crochet, there is no chance of unravelling, as you progress one stitch at a time. She got the knack pretty quickly. It helped that Daina was a demon at craftwork, a consequence of a childhood in 1960s Soviet Latvia.

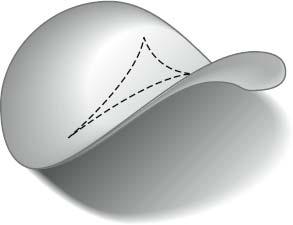

For her first crochet model she added an extra stitch for every two stitches on the previous line. The result, however, was a piece of material with many tight ruffles. ‘It was too curly,’ she said. ‘I couldn’t see what was going on.’ So for her next attempt, she changed the ratio, adding an extra stitch only for every five on the previous line. It worked better than she had expected. The material was now properly folding in on itself. She picked it up and followed straight lines in and out of the expanding flaps, and quickly realized that she could see parallel lines that diverged. ‘It was the picture I always wanted to see,’ she beamed. ‘That was my excitement. It was also a quick thrill to make something with my hands that cannot be made by computer.’

Daina showed the hyperbolic crochet model to her husband – and he was as excited as she was. David Henderson is professor of geometry at Cornell. His specialism is topology, which Daina claims to know nothing about. He explained to her that topologists have long known that when an octagon is drawn on the hyperbolic plane it can be folded together in such a way as to resemble a pair of pants. ‘We have to construct that octagon!’ he told her, which is just what they did. ‘No one had seen a hyperbolic pair of pants before!’ Daina exclaimed, and opened a sports bag she had with her, took out a crocheted hyperbolic octagon and folded it to show me the model. It looked liht liery cute pair of woollen toddler’s shorts:

Word spread around the Cornell maths faculty about Daina’s threaded creations. She told me she showed it to one colleague who is known for writing about hyperbolic planes. ‘He looked at the model and started playing with it. Then his face lit up. “This is what a horocycle looks like!” he said,’ having recognized a very complicated type of curve that he had never been able to picture before. ‘He had been writing about them all his career,’ added Daina, ‘but they were all in his imagination.’

It is no exaggeration to say that Daina’s hyperbolic models have given important new insight into a conceptually punishing area of maths. They give a visceral experience of the hyperbolic plane, allowing students to touch and feel a surface that was previously understood only in an abstract way. The models are not perfect, however. One problem is that the thickness of the stitches makes the crocheted models only a rough approximation of what in theory should be a smooth surface. Still, they are a great deal more versatile and accurate than a Pringle. If a piece of hyperbolic crochet had an infinite number of lines, it would theoretically be possible to live on that surface and walk for ever in one direction without ever coming to an edge.

One of the charms of Daina’s models is that they are unexpectedly organic-looking for something conceived so formally. When the relative line-by-line increase in stitches is small, the models look like leaves of kale. When the increase is greater the material naturally folds itself into pieces that look like coral. In fact, the reason Daina came to London was for the opening of the Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef, an exhibition inspired by her models to promote awareness of marine destruction. Thanks to her mathematical innovation, she has unwittingly spawned a global movement of crochet activism.

Over the last decade, Daina has crocheted more than a hundred hyperbolic models. She brought her largest to London. It is pink, uses 5.5km of yarn, weighs 4.5kg and took her six months. Finishing it was an ordeal. ‘As it got bigger it took a lot of energy to turn.’ A remarkable property of the model is that it has an incredibly large surface area – 3.2 square metres, which is twice as much surface area as Daina herself. Hyperbolic surfaces maximize area with minimal volume, which is why they are favoured by some plants and marine organisms. When an organism needs a large surface area – to absorb nutrition, as is the case with coral – it grows in a hyperbolic way.

It is unlikely that Daina would ever have thought up the idea of hyperbolic crochet had she been born a man, which makes her inventions a noteworthy artefact in the cultural history of mathematics, where women have long been under-represented. Crochet, in fact, is just one example of a traditionally female craft inspiring mathematicians in recent years to explore new techniques. Together with mathematical knitting, quilt-making, embroidery and weaving, the academic discipline is now known as Math and the Fiber Arts.

When hyperbolic space was first conceived it appeared to go against any sense of reality, yet it has become accepted as equally ‘real’ as flat or spherical surfaces. Every surface has its own geometry, and we need to choose the one that best applies, or, as Henri Poincaré once said: ‘One geomtry cannot be more true than another; it can only be more convenient.’ Euclidean geometry, for example, is the most appropriate for schoolchildren armed with rulers, compasses and flat pieces of paper, while spherical geometry is the most appropriate for airline pilots navigating flight paths.

Physicists are also interested in which geometry is most appropriate for their purposes. Riemann’s ideas about the curvature of surfaces provided Einstein with the equipment to make one of his greatest breakthroughs. Newtonian physics assumed that space was Euclidean, or flat. Einstein’s theory of general relativity, however, stated that the geometry of space-time (3-D space plus time considered as the fourth dimension) was not flat but curved. In 1919 a British scientific expedition in Sobral, a town in the northeast of Brazil, took images of the stars behind the sun during a solar eclipse and found that they had shifted slightly from their real positions. This was explained by Einstein’s theory that the light from the stars was curving a round the sun before it reached Earth. While the light appeared to bend around the sun when seen in three-dimensional space, which is the only way we can see things, it was actually following a straight line according to the curved geometry of space-time. The fact that Einstein’s theory correctly predicted the position of the stars vindicated his general theory of relativity and it is what made him a global celebrity. The London Times headline blazoned: ‘Revolution in Science, New Theory of the Universe, Newtonian Ideas Overthrown’.

Einstein was concerned with space-time, which he showed to be curved. What about the curvature of our universe without considering time as a dimension? In order to see which geometry best fits the behaviour of our three spatial dimensions on a large scale, we need to see how lines and shapes behave over extremely large distances. Scientists are hoping to discover this from the data that is being gathered by the Planck satellite, launched in May 2009, which is measuring cosmic background radiation – the so-called ‘afterglow’ of the Big Bang – to a higher resolution and sensitivity than ever before. Considered opinion is that the universe is either flat or spherical, although it is still possible that the universe might be hyperbolic. It is wonderfully ironic to think that a geometry originally thought to be nonsensical might actually reflect the way things really are.

At around the same time that mathematicians were exploring the counter-intuitive realm of non-Euclidean space, one man was turning upside-down our understanding of another mathematical notion: infinity. Georg Cantor was a lecturer at Halle University in Germany, where he developed a trail-blazing theory of numbers in which infinity could have more than one size. Cantor’s ideas were so unorthodox that they initially provoked ridicule from many of his peers. Henri Poincaré, for example, described his work as ‘a malady, a perverse illness from which some day mathematics would be cured’, while Leopold Kronecker, Cantor’s former teacher and professor of maths at Berlin University, dismissed him as a ‘charlatan’ and a ‘corruptor of youth’.

This war of words probably contributed to Cantor’s nervous breakdown in 1884, aged 39, the first of many mental-health episodes and hospitalizations. In his book on Cantor, Everything and More, David Foster Wallace writes: ‘The Mentally Ill Mathematician seems now in some ways to be what the Knight Errant, Mortified Saint, Tortured Artist, and Mad Stist have been for other eras: sort of our Prometheus, the one who goes to forbidden places and returns with gifts we can all use but he alone pays for.’ Literature and film are guilty of romanticizing a link between maths and insanity. It’s a cliché that suits the narrative requirements of a Hollywood script (exhibit A: A Beautiful Mind ) but is, of course, an unfair generalization. The great mathematician, however, for whom the archetype could have been invented is Cantor. The stereotype fits him especially well since he was grappling with infinity, a concept that links mathematics, philosophy and religion. Not only was he challenging mathematical doctrine, but he was also setting out a brand-new theory of knowledge and, in his mind, of human understanding of God. No wonder he upset a few people along the way.

Infinity is one of the most brain-mangling concepts in maths. We saw earlier, in our discussion of Zeno’s paradoxes, that envisaging an infinite number of ever-decreasing distances is full of mathematical and philosophical pitfalls. The Greeks tried to avoid infinity as much as they could. Euclid expressed ideas of infinity by making negative assertions. His proof that there is an infinite number of prime numbers, for instance, is actually a proof that there is no highest prime number. The ancients shied away from treating infinity as a self-contained concept, which is why the infinite series inherent in Zeno’s paradoxes were so problematic for them.

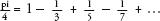

By the seventeenth century, mathematicians

were willing to accept operations involving an infinite number of

steps. The work of John Wallis, who in 1655 introduced the symbol 8

for infinity for the purpose of his work on infinitesimals (things

that become infinitely small), paved the way for Isaac Newton’s

calculus. The discovery of useful equations that involved an

infinite number of terms, such as  …showed that infinity was not

an enemy, yet even so, it was still to be treated with care and

suspicion. In 1831 Gauss stated the received wisdom when he said

that infinity was ‘merely a way of speaking’ about a limit that one

never reached, an idea that simply expressed the potential to carry

on and on for ever. Cantor’s heresy was to treat infinity as an

entity in itself.

…showed that infinity was not

an enemy, yet even so, it was still to be treated with care and

suspicion. In 1831 Gauss stated the received wisdom when he said

that infinity was ‘merely a way of speaking’ about a limit that one

never reached, an idea that simply expressed the potential to carry

on and on for ever. Cantor’s heresy was to treat infinity as an

entity in itself.

The reason why mathematicians pre-Cantor were nervous about treating infinity like any other number was that it contained many conundrums, the most famous of which Galileo wrote about in Two New Sciences, and is known as Galileo’s paradox:

1. Some numbers are squares, such as 1, 4, 9 and 16, and some are not squares, such as 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, etc.

2. The totality of all numbers must be greater than the total of squares, since the totality of all numbers includes squares and non-squares.

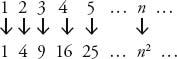

3. Yet for every number, we can draw a one-to-one correspondence between numbers and their squares, for example:

4. So, there are, in fact, as many squares as there are numbers. Which is a contradiction, since we have said, in point 2, that there are more numbers than squares.

Galileo’s conclusion was that, when it comes to infinityostmerical concepts ‘more than’, ‘equal to’ and ‘less than’ do not make sense. These terms may be understandable and coherent when discussing finite amounts, but not with infinite ones. It is meaningless to say there are more numbers than there are squares, or that there is an equal number of numbers and squares, since the totality of both numbers and squares is infinite.

Georg Cantor devised a new way to think about

infinity that made Galileo’s paradox redundant. Rather than

thinking about individual numbers, Cantor considered collections of

numbers, which he called ‘sets’. The cardinality of any set is the

number of members in the collection. So {1, 2, 3} is a set with a

cardinality of three and

{17, 29, 5, 14} is a set with cardinality four. Cantor’s ‘set

theory’ gets the pulse racing when considering sets with an

infinite number of members. He introduced a new symbol for

infinity,  , (pronounced aleph-null), using the first letter of the

Hebrew alphabet with the subscript 0, and said that this was the

cardinality of the set of natural numbers, or {1, 2, 3, 4, 5…}.

Every set whose members can be put in a one-to-one correspondence

with the natural numbers also has cardinality

, (pronounced aleph-null), using the first letter of the

Hebrew alphabet with the subscript 0, and said that this was the

cardinality of the set of natural numbers, or {1, 2, 3, 4, 5…}.

Every set whose members can be put in a one-to-one correspondence

with the natural numbers also has cardinality  . So, because there is a

one-to-one correspondence between the natural numbers and their

squares, the set of squares {1, 4, 9, 16, 25…} has cardinality

. So, because there is a

one-to-one correspondence between the natural numbers and their

squares, the set of squares {1, 4, 9, 16, 25…} has cardinality

.

Likewise, the set of odd numbers {1, 3, 5, 7, 9…}, the set of prime

numbers {2, 3, 5, 7, 11…} and the set of numbers with 666 in them

{666, 1666, 2666, 3666…}, all have cardinality

.

Likewise, the set of odd numbers {1, 3, 5, 7, 9…}, the set of prime

numbers {2, 3, 5, 7, 11…} and the set of numbers with 666 in them

{666, 1666, 2666, 3666…}, all have cardinality  . If you have a set with

an infinite number of members, and it is possible to count its

members one by one so that eventually every member will be reached,

then the cardinality of the set is

. If you have a set with

an infinite number of members, and it is possible to count its

members one by one so that eventually every member will be reached,

then the cardinality of the set is  . For this reason,

. For this reason,  is also known as

a ‘countable infinity’. The reason this is exciting is because

Cantor went on to show that we can go higher. Large though it may

be,

is also known as

a ‘countable infinity’. The reason this is exciting is because

Cantor went on to show that we can go higher. Large though it may

be,  is

merely the baby in Cantor’s family of infinities.

is

merely the baby in Cantor’s family of infinities.

I’ll introduce you to an infinity larger than

with the

help of a story David Hilbert is said to have used in his lectures

that concerns a hotel with a countably infinite, or

with the

help of a story David Hilbert is said to have used in his lectures

that concerns a hotel with a countably infinite, or  , number of rooms.

This well-known establishment, much loved by mathematicians, is

sometimes called the Hilbert Hotel.

, number of rooms.

This well-known establishment, much loved by mathematicians, is

sometimes called the Hilbert Hotel.

In the Hilbert Hotel there is an infinite number of rooms and they are numbered 1, 2, 3, 4…One day a traveller arrives at reception only to find that the hotel is full. He asks if there is any way a room can be found for him. The receptionist replies that of course there is! All the management needs to do is to reassign guests to different rooms in the following way: moving the guest in Room 1 to Room 2, moving the guest in Room 2 to Room 3, and so on, moving everyone in Room n to Room n + 1. If this is done, then every guest still has a room, and Room 1 is freed up for the new arrival. Perfect!

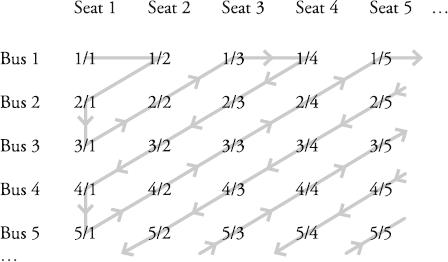

The following day a more complicated situation presents itself. A bus arrives, with all the passengers needing rooms. This bus has an infinite number of seats, numbered 1, 2, 3 and so on, all of which are occupied. Is there any way that a room can be found for each and very one of the passengers? In other words, even though the hotel is full, can the receptionist reshuffle the guests into different rooms in a way that leaves an infinite number of free rooms for the bus passengers? Easy peasy, comes the reply. All the management needs to do this time is to move every guest to the room numbered double the room he or she is already in, which takes care of Rooms 2, 4, 6, 8…This leaves all the rooms with odd numbers empty, and the bus passengers can be given the keys for those. The passenger on the first seat gets Room 1, the first odd number, the passenger on the second seat gets Room 3, the second odd number, and so on.

On the third day, even more buses arrive at the Hilbert Hotel. In fact, an infinite number of buses arrives. The buses are lined up outside, with Bus 1 next to Bus 2, which is next to Bus 3, and so on. Each bus has an infinite number of passengers, like the bus that arrived the day before. And, of course, every passenger needs a room. Is there a way to find every passenger in every bus a room in the (already full) Hilbert Hotel?

No problem, says the receptionist. First, he needs to clear an infinite number of rooms. He does this by the trick he used the day before – move everyone to a room with twice the room number. This leaves all the odd-numbered rooms free. In order to fit in the infinite coach parties, all he needs to do is find a way of counting all the passengers, since once he has found a method, he can assign the first passenger to Room 1, the second to Room 3, the third to Room 5, and so on.

He does it like this: for each bus, list the passengers by seat, as in the table below. Each passenger is therefore represented by the form m/n where m is the number of the bus they are on and n is their seat number. If we start at the passenger in the first seat in the first bus (person 1/1), and then form the zigzag pattern below, by letting the second person be the passenger who is in the second seat of the first bus (1/2), and the third be the first passenger on the second (2/1), we will eventually count every single passenger.

Now let’s translate what we have learned with the Hilbert Hotel into some symbolic mathematics:

When one person was found a room, this was the equivalent of showing that 1 +

=

When a countably infinite number of people could be found a room, we saw that

×

=

When a countably infinite number of buses, each containing a countably infinite number of passengers could be found a room, this revealed that

×

=

These rules are what we expect from infinity: add infinity to infinity and we get infinity, multiply infinity by infinity and we get infinity.

Let’s stop here a second. We have already

reached an amazing result. Look again at the table of seats and

buses. Consider each thenn denoted m/n as the fraction  . The table, when extended

infinitely, will cover every single positive fraction, since the

positive fractions can also be defined as

. The table, when extended

infinitely, will cover every single positive fraction, since the

positive fractions can also be defined as  for all natural numbers

m and n. For example, the fraction

for all natural numbers

m and n. For example, the fraction  will be covered

on the 5628th row and 785th column. The zigzag counting method that

counted every passenger in every bus can, therefore, also be used

to count every positive fraction. In other words, the set of all

positive fractions and the set of natural numbers have the same

cardinality, which is

will be covered

on the 5628th row and 785th column. The zigzag counting method that

counted every passenger in every bus can, therefore, also be used

to count every positive fraction. In other words, the set of all

positive fractions and the set of natural numbers have the same

cardinality, which is  . It seems intuitive that there should be more

fractions than there are natural numbers, since between any two

natural numbers there is an infinite number of fractions, yet

Cantor showed that our intuition is wrong. There are as many

positive fractions as there are natural numbers. (In fact, there

are as many positive and negative fractions as there are natural

numbers, since there are

. It seems intuitive that there should be more

fractions than there are natural numbers, since between any two

natural numbers there is an infinite number of fractions, yet

Cantor showed that our intuition is wrong. There are as many

positive fractions as there are natural numbers. (In fact, there

are as many positive and negative fractions as there are natural

numbers, since there are  positive fractions and

positive fractions and  negative fractions and, as

seen above,

negative fractions and, as

seen above,  ×

×  =

=  .)

.)

We can appreciate how strange this result is by considering the number line, which is a way of understanding numbers by considering them as points on a line. Below is a number line starting at 0 and heading off towards infinity.

Every positive fraction can be considered as a

point on this number line. From a previous chapter, we know that

there is an infinite number of fractions between 0 and 1, as there

is between 1 and 2, or between any two other numbers. Now imagine

holding a microscope up to the line so that you can see between the

points representing the fractions  and

and  . As we also showed earlier,

there is an infinite number of points representing fractions

between these two points. In fact, wherever you place your

microscope on the line, and however tiny the interval between two

points that your microscope can see, there will always be

infinitely many points representing fractions in this interval.

Since there are infinite numbers of points representing fractions

wherever you look, it comes as a bewildering surprise to realize

that it is, in fact, possible to count them in an ordered list that

will cover every single one without exception.

. As we also showed earlier,

there is an infinite number of points representing fractions

between these two points. In fact, wherever you place your

microscope on the line, and however tiny the interval between two

points that your microscope can see, there will always be

infinitely many points representing fractions in this interval.

Since there are infinite numbers of points representing fractions

wherever you look, it comes as a bewildering surprise to realize

that it is, in fact, possible to count them in an ordered list that

will cover every single one without exception.

Now for the big event: proof that there is a

cardinality larger than  . Back we go to the Hilbert Hotel. On this

occasion, the hotel is empty when an infinite number of people show

up wanting rooms. But this time the travellers have not come in

buses; they are in fact a rabble, with each wearing a T-shirt

displaying a decimal expansion of a number between 0 and 1. No two

people have the same decimal expansion on their chest and every

single decimal expansion between 0 and 1 is covered. (Of course,

the decimal expansions are infinitely long and so the T-shirts

would need to be infinitely wide to display them, yet since we have

suspended our disbelief in order to imagine a hotel with an

infinite number of rooms, I figure it is not asking too much to

envisage these T-shirts.)

. Back we go to the Hilbert Hotel. On this

occasion, the hotel is empty when an infinite number of people show

up wanting rooms. But this time the travellers have not come in

buses; they are in fact a rabble, with each wearing a T-shirt

displaying a decimal expansion of a number between 0 and 1. No two

people have the same decimal expansion on their chest and every

single decimal expansion between 0 and 1 is covered. (Of course,

the decimal expansions are infinitely long and so the T-shirts

would need to be infinitely wide to display them, yet since we have

suspended our disbelief in order to imagine a hotel with an

infinite number of rooms, I figure it is not asking too much to

envisage these T-shirts.)

A few of the arrivals charge into reception and ask if there is a way the hotel can accommodate them. For the receptionist to achieve this all he needs to do is find a way of listing every single decimal between 0 and 1, since once he has listed them, he can assign them rooms. This seems like a fair challenge, since, after all, he was able to find a way to list an infinite number of passengers from an infinite number of buses. This time, however, the task is impossible. There is no way to count every single decimal expansion between 0 and 1 in such a way that we can write them all down in an ordered list. To prove this I will show that for every infinite list of numbers between 0 and 1 there will always be a number between 0 and 1 that is not on the list.

This is how it’s done. Let’s imagine the first arrival has a T-shirt with the expansion 0.6429657…, the second has 0.0196012…, and the receptionist assigns them rooms 1 and 2. And say he carries on assigning rooms to the other arrivals, thus creating the infinite list that begins (remember, each of these expansions goes on for ever):

|

Room 1 |

0.6429657… |

|

Room 2 |

0.0196012… |

|

Room 3 |

0.9981562… |

|

Room 4 |

0.7642178… |

|

Room 5 |

0.6097856… |

|

Room 6 |

0.5273611… |

|

Room 7 |

0.3002981… |

|

Room… |

0… |

|

… |

… |

Our aim, stated earlier, is to find a decimal expansion between 0 and 1 that is not on this list. We do this using the following method. First, construct the number that has the first decimal place of the number in Room 1, the second decimal place of the number in Room 2, the third decimal place of the number in Room 3 and so on. In other words, we are selecting the diagonal digits that are underlined here:

0.6429657…

0.0196012…

0.9981562…

0.7642178…

0.6097856…

0.52736b>11…

0.3002981…

This number is:

0.6182811…

We’re almost there. We now need to do one final thing to construct our number that is not on the receptionist’s list: we alter every digit in this number. Let’s do this by adding 1 to every digit, so the 6 becomes a 7, the 1 becomes a 2, the 8 becomes a 9, and so on, to get this number: 0.7293922…

And now we have it. This decimal expansion is the exception that we were looking for. It cannot be on the receptionist’s list because we have artificially constructed it so it cannot be. The number is not in Room 1, because its first digit is different from the first digit of the number in Room 1. The number is not in Room 2 because its second digit is different from the second digit of the number in Room 2, and we can continue this to see that the number cannot be in any Room n because its nth digit will always be different from the nth digit in the expansion of Room n. Our customized expansion 0.7293922…therefore cannot be equal to any expansion assigned to a room since it will always differ in at least one digit from the expansion assigned to that room. There may well be a number in the list whose first seven decimal places are 0.7293922, yet if this number is on the list then it will differ from our customized number by at least one digit further down the expansion. In other words, even if the receptionist carries on assigning rooms for ever and ever, he will be unable to find a room for the arrival with the T-shirt marked with the number we created beginning 0.7293922…

I chose a list starting with the arbitrary numbers 0.6429657…and 0.0196012…but equally I could have chosen a list starting with any numbers. For every list that it is possible to make, it will always be possible to create, using the ‘diagonal’ method opposite, a number that is not on the list. The Hilbert Hotel may have an infinite number of rooms, yet it cannot accommodate the infinite number of people defined by the decimals between 0 and 1. There will always be people left outside. The hotel is simply not big enough.

Cantor’s discovery that there is an infinity

bigger than the infinity

of natural numbers was one of the greatest mathematical

breakthroughs of the nineteenth century. It is a mind-blowing

result, and part of its power is that the result really was quite

straightforward to explain: some infinities are countable, and they

have size  , and some infinities are not countable, and hence

bigger. These uncountable infinities come in many different

sizes.

, and some infinities are not countable, and hence

bigger. These uncountable infinities come in many different

sizes.

The easiest uncountable infinity to understand is called c and is the number of people who arrived at the Hilbert Hotel with T-shirts containing all the decimal expansions between 0 and 1. Again, it is instructive to interpret c by looking at what it means on the number line. Every person with a decimal expansion between 0 and 1 on his T-shirt can also be understood as a point on the line between 0 and 1. The initial c is used since it stands for the ‘continuum’ of points on a number line.

And here217;s where we come to another strange

result. We know that there are c points between 0 and 1, and yet we know

that there are  fractions on the totality of the number line. Since we

have proved that c is

bigger than

fractions on the totality of the number line. Since we

have proved that c is

bigger than  , it must be the case that there are more points on a

line between 0 and 1 than there are points that represent fractions

on the entire number line.

, it must be the case that there are more points on a

line between 0 and 1 than there are points that represent fractions

on the entire number line.

Again, Cantor has led us to a very counter-intuitive world. Fractions, though they are infinite in number, are responsible for only a tiny, tiny part of the number line. They are much more lightly sprinkled along the line than the other type of number that makes up the number line, the numbers that cannot be expressed as fractions, which are our old friends the irrational numbers. It turns out that the irrational numbers are so densely packed that there are more of them in any finite interval on the number line than there are fractions on all of the number line.

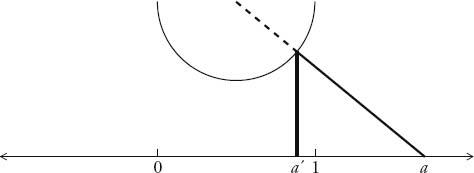

We introduced c above as being the number of points on a number line between 0 and 1. How many points are there between 0 and 2, or between 0 and 100? Exactly c of them. In fact, between any two points on the number line there are exactly c points in between, no matter how far or close they are apart. What’s even more amazing is that the totality of points on the entire number line is also c, and this is shown by the following proof, illustrated opposite. The idea is to show that there is a one-to-one correspondence between the points that lie between 0 and 1, and the points that lie on the entirety of the number line. This is done by pairing off every point on the number line with a point between 0 and 1. First, draw a semicircle suspended above 0 and 1. This semicircle acts like a matchmaker in that it fixes the couplings of the points between 0 and 1 and the points on the number line. Take any point on the number line, marked a, and draw a straight line from a to the centre of the circle. The line hits the semicircle at a point that is a unique distance between 0 and 1, marked a', by drawing a line vertically down until it meets the number line. We can pair up every point marked a to a unique point a' in this way. As our chosen point a heads to plus infinity, the corresponding point between 0 and 1 closes in on 1, and as the chosen point heads to minus infinity, the corresponding point closes in on 0. If every point on the number line can be paired off with a unique point between 0 and 1, and vice versa, then the number of points on the number line must be equal to the number of points between 0 and 1.

The difference between  and c is the difference between the number of

points on the number line that are fractions and the total number

of points, including fractions and irrationals. The leap between

and c is the difference between the number of

points on the number line that are fractions and the total number

of points, including fractions and irrationals. The leap between

and

c, however, is so immense

that were we to pick a point at random from the number line, we

have 0 percent probability of getting a fraction. There just aren’t

enough of them, compared to the uncountably infinite number of

irrationals.

and

c, however, is so immense

that were we to pick a point at random from the number line, we

have 0 percent probability of getting a fraction. There just aren’t

enough of them, compared to the uncountably infinite number of

irrationals.

Difficult as Cantor’s ideas were to accept at first, his invention of the aleph has been vindicated by history; not only is it now almost universally accepted into the numerical fold, but the zigzag and diagonal proofs are generally hailed as among the most dazzling in the whole of mathematics. David Hilbert said: ‘From the paradise created for us by Cantor, no one will drive us out.’

Unfortunately for Cantor, this paradise came at the expense of his mental health. After he recovered from his first breakdown, he began to focus on other subjects, such as theology and Elizabethan history, becoming convinced that the scientist Francis Bacon wrote the plays of William Shakespeare. Proving Bacon’s authorship became a personal crusade, and a focus for increasingly erratic behaviour. In 1911, giving a lecture at St Andrews University, where he had been invited to talk about mathematics, he instead discussed his views on Shakespeare, much to the embarrassment of his hosts. Cantor had several more breakdowns and was frequently hospitalized until his death in 1918.

A devout Lutheran, Cantor wrote many letters to clergymen about the significance of his results. He believed that his approach to infinity showed that it could be contemplated by the human mind, and therefore bring one closer to God. Cantor had Jewish ancestry, which – it has been argued – may have influenced his choice of the aleph as the symbol for infinity, since he may have been aware that in the mystical Jewish tradition of Kabbalah, the aleph represents the oneness of God. Cantor said he was proud he chose the aleph since, as the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, it was a perfect symbol for a new beginning.

The aleph is also a perfect place for an end to our journey. Mathematics, as I wrote in the opening chapters of this book, emerged as part of man’s desire to make sense of his own environment. By making notches on wood, or counting with fingers, our ancestors invented numbers. This was helpful for farming and trade, and ushered us into ‘civilization’. Then, as mathematics developed, the subject became less about real things and more about abstract ones. The Greeks introduced concepts such as a point and a line, and the Indians invented zero, which opened the door to even more radical abstractions like negative numbers. While these concepts were at first counter-intuitive, they were assimilated quickly and we now use them on a daily basis. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the umbilical cord linking mathematics to our own experience snapped once and for all. After Riemann and Cantor, maths lost its connection to any intuitive appreciation of the world.

After finding c Cantor kept going, proving that there are even bigger infinities. As we saw, c is the number of points on a line. It is also equal to the number of points on a two-dimensional surface. (That’s another surprising result, which you’ll have to trust me on.) Let’s call d the number of all possible curves, lines and squiggles that can be drawn on a two-dimensional surface. Using set theory, we can prove that d is bigger than c. And we can go one step further, showing that there must be an infinity larger than d. Yet no one has so far been able to come up with a set of things that has a cardinality larger than d.

Cantor led us beyond the imaginable. It is a rather wonderful place and one that is amusingly opposite to the situation of the Amazonian tribe I mentioned at the beginning of this book. The Munduruku have many things, but not enough numbers to count them. Cantor has provided us with as many numbers as we like, but there are no longer enough things to count.