Something about Nothing

Every year the Indian seaside town of Puri fills with a million pilgrims. They come for one of the most spectacular festivals in the Hindu calendar – the Rath Yatra, in which three chariots the size of carnival floats are pulled through the town. When I visited, the streets were crowded with cymbal-crashing, mantra-chanting devotees, barefoot holy men with long beards and middle-class Indian tourists with fashionable T-shirts and neon saris. It was midsummer, the beginning of the monsoon season, and in between downpours festival-workers sprayed the faces of passers-by with water to cool them down. Smaller Rath Yatra processions take place simultaneously all over India, although Puri’s is the focal event and its chariots the biggest.

The festival gets under way only when the local holy man, the Shankaracharya of Puri, stands in front of the crowds and blesses them. The Shankaracharya is one of Hinduism’s most important sages, the head of a monastic order that dates back more than a thousand years. He was also the reason I had travelled to Puri. As well as being a spiritual leader, the Shankaracharya is a published mathematician. I was also a pilgrim in search of enlightenment.

Right away in India, I noticed something unfamiliar about their use of numbers. In my hotel reception I picked up a copy of The Times of India. With the paper’s corners flapping from gusts of competing metal fans, the front-page headline caught my eye:

5 crore more Indians

than govt thought

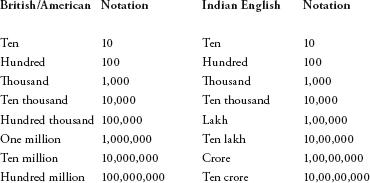

Crore is the Indian-English word for ten million, so the article was saying that India had just discovered 50 million citizens it never knew it had – a number roughly comparable to the population of England. It was startling that a country could overlook such a large number, even if it represented less than 5 percent of the overall population. Yet I was more puzzled by the word crore. Indian English has different words for high numbers than British or American English. For example, the word ‘million’ is not used. A million is instead expressed as ten lakh, where lakh is 100,000. Since ‘million’ is unheard of in India, the Oscar-winning film Slumdog Millionaire was released there as Slumdog Crorepati. A very rich person is someone who has a crore of dollars or rupees, not a million of them. The table of Indian equivalents for British/American number words is as follows:

Note that above a thousand, Indians introduce a comma after every two digits, while in the rest of the world the convention is every three.

The use of lakh and crore is a legacy of the mathematics of ancient India. The words come from the Hindi lakh and karod, which in turn came from the Sanskrit words for those numbers, laksh and koti. In ancient India coining words for large numbers was a scientific and religious preoccupation. For example, in the Lalitavistara Sutra, a Sanskrit text that dates from the beginning of the fourth century at the latest, the Buddha is challenged to express numbers higher than a hundred koti. He replies:

One hundred koti are called an ayuta, a hundred ayuta make a niyuta, a hundred niyuta make a kankara, a hundred kankara make a vivara, a hundred vivara are a kshobhya, a hundred kshobhya make a vivaha, a hundred vivaha make a utsanga, a hundred utsanga make a bahula, a hundred bahula make a nâgabala, a hundred nâgabala make a titilambha, a hundred titilambha make a vyavasthânaprajñapati, a hundred vyavasthânaprajñapati make a hetuhila, a hundred hetuhila make a karahu, a hundred karahu make a hetvindriya, a hundred hetvindriya make a samâptalambha, a hundred samâptalambha make a gananâgati, a hundred gananâgati make a niravadya, a hundred niravadya make a mudrâbala, a hundred mudrâbala make a sarvabala, a hundred sarvabala make a visamjñagati, a hundred visamjñagati make a sarvajña, a hundred sarvajña make a vibhutangamâ, a hundred vibhutangamâ make a tallakshana.

Just as in contemporary India, the Buddha went up the list in multiples of a hundred. Since a koti is ten million, the value of a tallakshana is ten million multiplied by a hundred 23 times, which works out as 10 followed by 52 zeros, or 1053. This is a phenomenally large number, so large, in fact, that if you measure the entire universe from end to end in metres, and then square that number, you are roughly around 1053.

But Buddha didn’t stop there. He was just warming up. He explained that he had described only the tallakshana counting system, and above it there was another one, the dhvajâgravati system, made up of the same number of terms. And above that, another one, the dhavjâgranishâmani, again with 24 number words. In fact, there were another six systems to go – which the Buddha, of course, listed perfectly. The last number in the final system is equivalent to 10421: one followed by 421 zeros.

It is worth taking a breath to consider the view. There are an estimated 1080 atoms in the universe. If we take the smallest measurable unit of time – known as Planck time, which is a second divided into 1043 parts – then there have been about 1060 units of Planck time since the Big Bang. If we multiply the number of atoms in the universe by the number of Planck times since the Big Bang – which gives us the number of unique positions of every particle since time began – we are still only on 10140, which is way, way smaller than 10421. The Buddha’s big number has no practical application – at least not for counting things that exist.

Not only was the Buddha able to fathom the impossibly large, he was also proficient in the realm of the impossibly tiny, explaining how many atoms there were in the yojana, an ancient unit of length around 10km. A yojana, he said, was equivalent to:

Four krosha, each of which was the length of

One thousand arcs, each of which was the length of

Four cubits, each of which was the length of

Two spans, each of which was the length of

Twelve phalanges of fingers, each of which was the length of

Seven grains of barley, each of which was the length of

Seven mustard seeds, each of which was the length of

Seven poppy seeds, each of which was the length of

Seven particles of dust stirred up by a cow, each of which was the length of

Seven specks of dust disturbed by a ram, each of which was the length of

Seven specks of dust stirred up by a hare, each of which was the length of

Seven specks of dust carried away by the wind, each of which was the length of

Seven tiny specks of dust, each of which was the length of

Seven minute specks of dust, each of which was the length of

Seven particles of the first atoms.

This was, in fact, a pretty good estimate. Just say that a finger is 4cm long. The Buddha’s ‘first atoms’ are, therefore, 4cm divided by seven ten times, which is 0.04m×7–10 or 0.0000000001416m, which is more or less the size of a carbon atom.

The Buddha was by no means the only ancient Indian interested in the incredibly large and the unfeasibly small. Sanskrit literature is full of astronomically high numbers. Followers of Jainism, a sister religion to Hinduism, defined a raju as the distance covered by a god in six months if he covers 100,000 yojana in each blink of his eye. A palya was the amount of time it takes to empty a giant yojana-sized cube filled with the wool of newborn lambs if one strand is removed every century. The obsession with high (and low) numbers was metaphysical i nature, a way of groping towards the infinite and of grappling with life’s big existential questions.

Before Arabic numerals became an international

lingua franca, humans had many other ways of writing down numbers.

The first number symbols that emerged in the West were notches,

cuneiform bird tracks and hieroglyphics. When languages developed

their own alphabets, cultures began to use letters to represent

numbers. The Jews used the Hebrew aleph ( ) to mean one, bet (

) to mean one, bet ( ) to be two and so

on. The tenth letter, yod (

) to be two and so

on. The tenth letter, yod ( ), was ten, after which each letter went up in

tens, and on reaching 100 went up in hundreds. The twenty-second

and final letter of the Hebrew alphabet, tav (

), was ten, after which each letter went up in

tens, and on reaching 100 went up in hundreds. The twenty-second

and final letter of the Hebrew alphabet, tav ( ), was 400. Using letters for

numbers was confusing and also encouraged a numerological approach

to counting. Gematria, for example, was the practice of adding up

the numbers of the letters in Hebrew words to find a value and

using this number for speculations and divinations.

), was 400. Using letters for

numbers was confusing and also encouraged a numerological approach

to counting. Gematria, for example, was the practice of adding up

the numbers of the letters in Hebrew words to find a value and

using this number for speculations and divinations.

The Greeks used a similar system, with alpha

( ) being

one, beta (ß) being two, and so on to the twenty-seventh letter of

their alphabet, sampi (

) being

one, beta (ß) being two, and so on to the twenty-seventh letter of

their alphabet, sampi ( ), which was 900. Greek mathematical culture, the

most advanced in the classical world, did not share the Indian

hunger for jumbo numbers. The highest-value number word they had

was myriad, meaning

10,000, which they wrote as a capital M.

), which was 900. Greek mathematical culture, the

most advanced in the classical world, did not share the Indian

hunger for jumbo numbers. The highest-value number word they had

was myriad, meaning

10,000, which they wrote as a capital M.

Roman numerals were also alphabetic, although their system had more ancient roots than those of either the Greeks or the Jews. The symbol for one was I, probably a relic of a notch on a tally stick. Five was V, maybe because it looked like a hand. The other numbers were X, L, C, D and M for 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000. All the other numbers were generated using these seven capital letters. The Roman system’s provenance from the tally stick made it a very intuitive way of writing out numbers. It was also efficient – using just seven symbols compared to 22 in Hebrew and 27 in Greek – and Roman numerals were the predominant number system in Europe for well over a thousand years.

Roman numerals, however, were very poorly suited to arithmetic. Let’s try to calculate 57×43. The best way to do this is with a method known as Egyptian or peasant multiplication, because it dates back at least to ancient Egypt. It is an ingenious method, though slow.

You first decompose one of the numbers being multiplied into powers of two (which are 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 and so on, doubling each time) and make a table of the doubles of the other number. So, for the example 57×43, let us decompose 57 and draw up a table of doubles of 43. I’m using Arabic numerals to show how it’s done, and will translate into Roman numerals afterwards.

Decomposition: 57 = 32 + 16 + 8 + 1

Table of doubles:

|

1×43 = |

43 |

|

2×43 = |

86 |

|

4×43 = |

172 |

|

8×43 = |

344 |

|

16×43 = |

688 |

|

32×43 = |

1376 |

The multiplication of 57×43 is equivalent to the addition of the numbers in the table of doubles that correspond to amounts in the decomposition. This sounds like a mouthful but is fairly straightforward. The decomposition contains a 32, a 16, an 8 and a 1. In the table, 32 corresponds to 1376, 16 corresponds to 688, 8 corresponds to 344 and 1 corresponds to 43. So, we can rewrite the initial multiplication as 1376 + 688 + 344 + 43, which equals 2451.

Now for the Roman numerals: 57 is LVII and 43 is XLIII. The decomposition and the table becomes:

LVII = XXXII + XVI + VIII + I

and

XLIII

LXXXVI

CLXXII

CCCXLIV

DCLXXXVIII

MCCCLXXVI

so,

LVII×XLIII = MCCCLXXVI + DCLXXXVIII + CCCXLIV + XLIII = MMCDLI

Oof! By breaking down the calculation into digestible morsels involving only doubling and adding, Roman numerals are just about up to the task. Still, we did much more work than we needed to. I mentioned earlier that the Roman system was intuitive and efficient. I’m taking that back. The Roman system quickly becomes counter-intuitive since the length of the number is not dependent on value. MMCDLI is larger than DCLXXXVIII, but uses fewer numerals, which goes against common sense. And any efficiency gained by using only seven symbols is forfeited by the inefficiency of how they are used. Often long strings are required to signify small numbers: LXXXVI uses six symbols, compared to the Arabic equivalent, 86, which uses two.

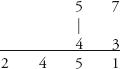

Compare the calculation above with the method of ‘long’ multiplication we all learned at school:

There is a very simple reason why our method is easier and quicker. Neither the Romans nor the Greeks or Jews had a symbol for zero. When it comes to sums, nothing makes all the difference.

The Vedas are Hinduism’s sacred texts. They have been passed down orally for generations until being transcribed into Sanskrit about 2000 years ago. In one of the Vedas a passage about the construction of altars lists the following number words:

|

Dasa |

10 |

|

Sata |

100 |

|

Sahasra |

1000 |

|

Ayuta |

10,000 |

|

Niyuta |

100,000 |

|

Prayuta |

1,000,000 |

|

Arbuda |

10,000,000 |

|

Nyarbuda |

100,000,000 |

|

Samudra |

1,000,000,000 |

|

Madhya |

10,000,000,000 |

|

Anta |

100,000,000,000 |

|

Parârdha |

1,000,000,000,000 |

With names for every multiple of ten, large numbers can be described very efficiently, which provided astronomers and astrologers (and, presumably, altar builders) with a suitable vocabulary for referring to the enormous quantities required in their calculations. This is one reason why Indian astronomy was ahead of its time. Consider the number 422,396. The Indians started at the smallest digit, at the right, and enumerated the others successively from right to left: Six and nine dasa and three sahasra and two ayuta and two niyuta and four prayuta. It is not too much of a step to realize that you can leave out the names for the powers of ten, since the position of the number in the list defines its value. In other words, the number above could be written: six, nine, three, two, two, four.

This type of enumeration is known as a ‘place-value’ system, which we discussed earlier. An abacus bead has a value dependent on which column it is in. Likewise, each number in the above list has a value dependent on its position in the list. Place-value systems, however, require the concept of a ‘place-holder’. For example, if a number has two dasa, no sata and three sahasra it cannot be written two, three since that refers to two dasa and three sata. A place-holder is needed to maintain the correct positions, to make it clear that there are no sata, and the Indians u a e word shunya – meaning ‘void’ – to refer to this place-holder. The number that is just two dasa and three sahasra would be written as two, shunya, three.

The Indians were not the first to introduce a place-holder. That honour probably went to the Babylonians, who wrote their number symbols in columns with a base 60 system. One column was for units, the next column was for 60s, the next for 3600s and so on. If a number had no value for that column, it was initially left blank. This, however, led to confusion, so they eventually introduced a symbol that denoted the absence of a value. This symbol, however, was used only as a marker.

After adopting shunya as a place-holder, the Indians took the idea and ran with it, upgrading shunya into a fully fledged number of its own: zero. Nowadays, we have no difficulty in understanding that zero is a number. But the idea was far from obvious. The Western civilizations, for example, failed to come up with it even after thousands of years of mathematical enquiry. Indeed, the scale of the conceptual leap achieved by India is illustrated by the fact that the classical world was staring zero in the face and still saw right through it. The abacus contained the concept of zero because it relied on place value. For example, when a Roman wanted to express 101, he would push a bead in the first column to signify 100, move no beads in the second column, indicating no tens, and push a bead in the third column to signify a single unit. The second, untouched column was expressing nothing. In calculations, the abacist knew he had to respect untouched columns just as he had to respect ones in which the beads were moved. But he never gave the value expressed by the untouched column a numerical name or symbol.

Zero took its first tentative steps as a bonafide number under the tutelage of Indian mathematicians such as Brahmagupta, who in the seventh century showed how shunya behaved towards its number siblings:

A debt minus shunya is a debt

A fortune minus shunya is a fortune

Shunya minus shunya is shunya

A debt subtracted from shunya is a fortune

A fortune subtracted from shunya is a debt

The product of shunya multiplied by a debt or fortune is shunya

The product of shunya multiplied by shunya is shunya

If ‘fortune’ is understood as a positive number, a, and ‘debt’ as a negative number, –a, Brahmagupta has written out the statements:

–a – 0 = –a

a – 0 = a

0 – 0 = 0

0 – (–a) = a

0 – a = –a

0× a = 0, 0

×– a = 0

0×0 = 0

Numbers had emerged as tools for counting, as abstractions that described amounts. But zero was not a counting number in the same way; understanding its value required a further level of abstraction. Yet the less that maths was tied to actual things, the more powerful it became.

Treating zero as a number meant that the place-value system that had made the abacus the best way to calculate could be properly exploited using written symbols. Zero would enhance mathematics in other ways too, by leading to the ‘invention’ of negative numbers and decimal fractions – concepts we learn effortlessly at school and are intrinsic to our needs in daily life, but which were in no way self-evident. The Greeks made fantastic mathematical discoveries without a zero, negative numbers or decimal fractions. This was because they had an essentially spatial understanding of mathematics. To them it was nonsensical that nothing could be ‘something’. Pythagoras was no more able to imagine a negative number than a negative triangle.

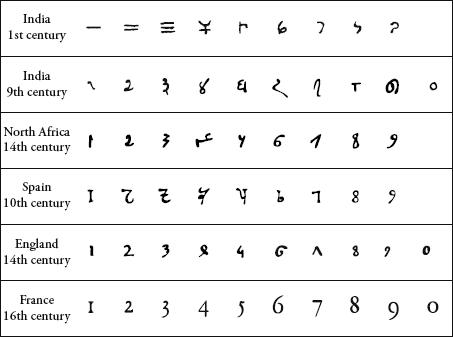

Evolution of modern numerals.

Of all the innovative ways that numbers were treated in ancient India, perhaps none was more curious than the vocabulary used to describe the numbers from zero to nine. Rather than each digit having a unique name, there was a colourful lexicon of synonyms. Zero, for example, was shunya, but it was also ‘ether’, ‘dot’, ‘hole’ or the ‘serpent of eternity’. One could be ‘earth’, ‘moon’, ‘the pole star’ or ‘curdled milk’. Two was interchangeable with ‘arms’, three with ‘fire’ and four with ‘vulva’. The names that were chosen depended on context and conformed to Sanskrit’s strict rules of versification and prosody. For example, the following verse is a piece of number-crunching from an ancient astrological text:

The apsides of the moon in a yuga

Fire. Vacuum. Horsemen. Vasu*. Serpent. Ocean, and of its waning node

Vasu. Fire. Primordial Couple. Horsemen. Fire. Twins.

The translation is:

[The number of revolutions] of the apsides of the moon in a [cosmic cycle is]

Three. Zero. Two. Eight. Eight. Four, [or 488,203] and of its waning node

Eight. Three. Two. Two. Three. Two. [or 232,238]

While at first it might seem confusing to have flowery alternatives for each digit, it actually makes perfect sense. During a period in history when manuscripts were flimsy and easily spoiled, astronomers and astrologers needed a backup method to remember significant numbers accurately. Strings of digits were more easily memorized when described in verse with varied names, rather than when using the same number names repeatedly.

Another reason why numbers were passed down orally was that the numerals that were emerging in different regions of India for the numbers from one to nine (zero, I will come to later) were not the same. Two people who did not understand each other’s number symbols could at least communicate numbers using words. By 500 CE, however, there was greater uniformity in the numerals used, and India had the three elements that were required for a modern decimal number system: ten numerals, place value, and an all-singing, all-dancing zero.

Owing to its ease of use, the Indian method spread to the Middle East, where it was embraced by the Islamic world, which accounts for why the numerals have come to be known, erroneously, as Arabic. From there they were brought to Europe by an enterprising Italian, Leonardo Fibonacci, his last name meaning ‘son of Bonacci’. Fibonacci was first exposed to the Indian numerals while growing up in what is now the Algerian city of Béjaïa, where his father was a Pisan customs official. Realizing that they were much better than Roman ones, Fibonacci wrote a book about the decimal place-value system called the Liber Abaci, published in 1202. It opens with the happy news:

The nine Indian figures are:

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

With these nine figures, and with the sign 0, which the Arabs call zephyr, any number whatsoever is written, as will be demonstrated.

More than any other book, the Liber Abaci introduced the Indian system to the West. In it Fibonacci demonstrated ways to do arithmetic that were quicker, easier and more elegant than the methods the Europeans had been using. Long multiplication and long division might seem dreary to us now, but at the beginning of the thirteenth century they were the latest technological novelty.

Not everyone, however, was convinced to switch immediately. Professional abacus operators felt threatened by the easier counting method, for one thing. (They would have been the first to realize that the decimal system was essentially the abacus with written symbols.) On top of that, Fibonacci’s book appeared during the period of the Crusades against Islam, and the clergy was suspicious of anything with Arab connotations. Some, in fact, considered the new arithmetic the Devil’s work precisely because it was so ingenious. A fear of Arabic numerals is revealed through the etymology of some modern words. From zephyr came ‘zero’ but also the Portuguese word chifre, which means ‘[Devil] horns’, and the English word cipher, meaning ‘code’. It has been argued that this was because using numbers with a zephyr, or zero, was done in hiding, against the wishes of the Church.

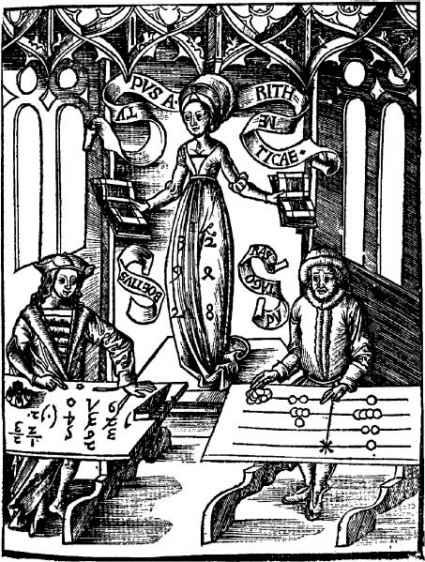

Arithmetica, the spirit of arithmetic, adjudicates between Boethius, who is using Arabic numerals, and Pythagoras, who has a counting board. Her adoring gaze and the numbers on her dress give away which method she prefers. From a woodblock engraving in Greorius Reisch’s Margarita Philosophica (1503).

In 1299 Florence banned Arabic numerals because, it was said, the slinky symbols were easier to falsify than solid Roman Vs and Is. A 0 could easily become a 6 or 9, and a 1 morph seamlessly into a 7. As a consequence, it was only around the end of the fifteenth century that Roman numerals were finally superseded, though negative numbers took much longer to catch on in Europe, gaining acceptance only in the seventeenth century, because they were said to be used in calculations of illegal money-lending, or usury, which was associated with blasphemy. In places where no calculation is needed, however, such as legal documents, chapters in books and dates at the end of BBC programmes, Roman numerals still live on.

With the adoption of Arabic numbers, arithmetic joined geometry to become part of mathematics in earnest, having previously been more of a tool used by shopkeepers, and the new system helped open the door to the scientific revolution.

A more recent Indian contribution to the world of numbers is a set of arithmetical tricks collectively known as Vedic Mathematics. It was discovered at the beginning of the twentieth century by a young swami, Bharati Krishna Tirthaji, who claimed to have found them in the Vedas, which was rather like, say, a vicar announcing he had found a method for solving quadratic equations in the Bible. Vedic Mathematics is based on the following list of 16 aphorisms, or sutras, which Tirthaji said were not actually written in any passage of the Vedas, instead being detectable only ‘on the basis of intuitive revelation’.

- By one more than the one before

- All from 9 and the last from 10

- Vertically and Cross-wise

- Transpose and Apply

- If the Samuccaya is the Same it is Zero

- If One is in Ratio the Other is Zero

- By Addition and by Subtraction

- By the Completion or Non-Completion

- Differential Calculus

- By the Deficiency

- Specific and General

- The Remainders by the Last Digit

- The Ultimate and Twice the Penultimate

- By One Less than the One Before

- The Product of the Sum

- All the Multipliers

Was he serious? Yes, and very much so too. Tirthaji was one of the most respected holy men of his generation. A former child prodigy, graduating in Sanskrit, philosophy, English, maths, history and science at the age of 20, he was also a talented orator who, it became clear early into adulthood, was destined to take a prominent role in Indian religious life. In 1925 Tirthaji was indeed made a Shankaracharya, one of the senior positions in traditional Hindu society, in charge of a nationally important monastery in Puri, Orissa, on the Bay of Bengal. This is the town thatI was visiting, the focus of the Rath Yatra chariot festival, where I was hoping to meet the incumbent Shankaracharya, who is the current ambassador for Vedic Mathematics.

In his role as Shankaracharya in the 1930s and 1940s, Tirthaji regularly toured India, giving sermons to crowds of tens of thousands, usually dispensing spiritual guidance but also promoting his new way of calculation. The 16 sutras, he taught, were to be used as if they were mathematical formulae. While they might have sounded ambiguous, like chapter titles in an engineering book or numerological mantras, they in fact referred to specific rules. One of the most straightforward is the second, All from 9 and the last from 10. This is to be implemented whenever you are subtracting a number from a power of ten, such as 1000. If I want to calculate 1000 – 456, for example, then I subtract 4 from 9, 5 from 9 and 6 from 10. In other words, the first two numbers from 9 and the last from 10. The answer is 544. (The other sutras are applications for other situations, more of which I will introduce later.)

Tirthaji promoted Vedic Mathematics as a gift to the nation, arguing that maths that usually took schoolchildren 15 years to learn could, with the sutras, be learned in just eight months. He even went as far as claiming that the system could be expanded to cover not just arithmetic but algebra, geometry, calculus and astronomy. Due to Tirtharji’s moral authority and charisma as a public speaker, audiences loved him. The general public, he wrote, were ‘highly impressed, nay, thrilled, wonder-struck and flabbergasted!’ at Vedic Mathematics. To those who asked whether the method was maths or magic, he had a set reply: ‘It is both. It is magic until you understand it; and it is mathematics thereafter.’

In 1958, when he was 82 years old, Tirthaji visited the United States, which caused much controversy back home because Hindu spiritual leaders are forbidden from travelling abroad, and it was the first time that a Shankaracharya had ever left India. His trip provoked great curiosity in the US. The West Coast would later become a focus for flower power, gurus and meditation, but back then no one had seen anyone like him. When Tirthaji arrived in California the Los Angeles Times called him ‘one of the most important – and least-known – personages in the world’.

Tirthaji had a full schedule of talks and TV appearances. Though he spoke mostly about world peace, he devoted one lecture entirely to Vedic Mathematics. The venue was the California Institute of Technology, one of the most prestigious scientific institutions in the world. Tirthaji, who weighed not much more than seven stone and was wearing traditional robes, sat in a chair at the front of a wood-panelled classroom. In a quiet voice, but with a commanding presence, he told his audience: ‘I have been, from my childhood, equally fond of metaphysics on the one side and mathematics on the other. And I’ve found no difficulty at all.’

He went on to explain exactly how he had found the sutras, asserting that there was a wealth of hidden knowledge in the Vedic texts that came from the many double meanings of words and phrases. These mystical ‘puns’, he added, had been totally lost on Western Indologists. ‘The supposition is that mathematics was not part of the Vedic literature,’ he said, ‘but when I was able to find it, well, it was easy sailing.’

Tirthaji’s opening trick was to demonstrate how to multiply 9×8 without using a multiplication table. This uses the sutra All from 9 and the last from 10, although why it does so only becomes clear later.

First, he drew a 9 on the blackboard, followed by the difference of 9 from 10, which is –1. Underneath he drew 8 and next to it the difference of 8 from 10, which is –2.

|

9 |

–1 |

|

8 |

–2 |

The first number of the answer can be derived in four different ways. Either add the numbers in the first column and subtract ten (9 + 8 – 10 = 7). Or add the numbers in the second column and add ten (–1 – 2 + 10 = 7) or add either of the diagonals (9 – 2 = 7, and 8 – 1 = 7). The answer is always seven.

The second part of the answer is calculated by multiplying the two numbers in the second column (–1×–2 = 2). The complete answer is 72.

I find this trick immensely satisfying. Writing out a single-digit number next to its difference from ten is somehow like pulling it apart to reveal its inner personality, lining up the ego and alter ego. We get a deeper understanding of how the number behaves. A sum such as 9×8 is about as mundane as they come, yet scratch the surface and we see unexpected elegance and order. And the method works not just for 9×8 but for any two numbers. Tirthaji chalked up another example: 8×7.

Again, the first digit can be derived in any one of the four ways: 8 + 7 – 10 = 5, or –2 – 3 + 10 = 5, or 8 – 3 = 5 or 7 – 2 = 5. The second digit is the product of the digits in the second column, –2×–3 = 6.

Tirthaji’s tactic reduces the multiplication of two single-digit numbers to an addition and the multiplication of the differences of the original numbers from ten. In other words, it reduces the multiplication of two single digit numbers larger than five to an addition and the multiplication of two numbers less than five. Which means that it is possible to multiply by six, seven, eight and nine without going higher than our five-times table. This is useful to people who find learning their times tables difficult.

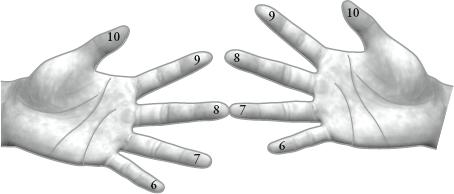

In fact, the technique explained by Tirthaji is the same as a method of finger calculation used at least since the Renaissance in Europe, and still used by farmhands in parts of France and Russia as late as the 1950s. On each hand the fingers are assigned the numbers from 6 to 10. To multiply two numbers together, say 8 and 7, touch the 8 finger to Weinger. The number of digits above the linking fingers on one side is subtracted from the linking finger on the other side (either 7 – 2 or 8 – 3) to give 5. The number of digits above the linking fingers on each side, 2 and 3, are multiplied to make 6. The answer, as above, is 56.

How to calculate 8 ×7 with ‘peasant’ finger multiplication.

Tirthaji continued his talk by demonstrating that the method also works when multiplying two-digit numbers, this time using the example 77×97. He wrote on the board:

77

97

Then, instead of writing the difference of 77 from 10, he wrote the difference of each number from 100. (This is where the second sutra comes in. When subtracting a number from 100, or any larger power of 10, all the digits of the number are subtracted from 9 apart from the last one, which is subtracted from 10, as I showed on chapter 3):

|

77 |

–23 |

|

97 |

–3 |

As before, in order to get the first part of the answer there are four options. He chose to show the two diagonal additions: 77 – 3 = 97 – 23 = 74.

The second part is derived by multiplying both digits in the right-hand column: –23×–3 = 69.

The answer is 7469.

Tirthaji then proceeded to an example with three figures: 888×997. This time the difference is calculated from 1000.

Diagonal addition gives 885 for the first part, and multiplication of the right column gives 336 for the second, for an answer of 885,336.

‘Equations are rendered much easier by these formulae,’ Tirthaji commented. The students reacted with spontaneous hearty laughter. Perhaps the chuckles came from the absurdity of an 82-year-old guru in a robe teaching basic arithmetic to some of the smartest maths students in the US. Or perhaps it was in appreciation of the playfulness of Tirthaji’s arithmetical tricks. Arabic numerals are a mine of hidden patterns, even at such a simple level as multiplying two single digits together. Tirthaji then tinued his talk with techniques for squaring, dividing and algebra. The response seems to have been enthusiastic, judging by a transcription made of the lecture notes: ‘Immediately following the end of the demonstration, one student was heard to ask his friend beside him, “What do you think?” His friend’s reply, “Fantastic!”’

On his return to India, Tirthaji was summoned to the holy city of Varanasi, where a special council of Hindu elders discussed his breach of protocol in leaving the country. It was decided that his trip was to be the first and last time that a Shankaracharya was allowed to travel abroad, and Tirthaji undertook a purification ritual just in case he had consumed unHindu food while on his travels. Two years later, he passed away.

In my hotel in Puri I met up with two leading proponents of Vedic Mathematics to learn more about it. Kenneth Williams is a 62-year-old former maths teacher from southern Scotland who has written several books about the method. ‘It is so beautifully presented and so unified as a system,’ he told me. ‘When I first found out about it I thought this is the way mathematics ought to be.’ Williams was a subdued, gentle man with a priestly forehead, trim salt-and-pepper beard and heavy-lidded blue eyes. With him was the much more talkative Gaurav Tekriwal, a 29-year-old stockbroker from Kolkata, who was wearing a crisp white shirt and Armani shades. Tekriwal is president of the Vedic Maths Forum India, an organization that runs a website, arranges talks and sells DVDs.

Tekriwal had helped me secure an audience with the Shankaracharya, and he and Williams wanted to accompany me. We hailed a motor rickshaw and set off to the Govardhan Math, an auspicious name but one that, unfortunately, has nothing to do with maths. It means monastery, or temple. We passed the seafront and small streets lined with stalls selling food and patterned silk. The Math is a plain brick and concrete building the size of a small country church, surrounded by palm trees and a sand garden planted with basil, aloe vera and mango. In the courtyard is a banyan tree, its trunk decorated with ochre cloth, where Shankara, the eighth-century Hindu sage who founded the order, is believed to have sat and meditated. The only modern touch was a shiny black frontage on the first floor – a bullet-proof façade that was installed to protect the Shankaracharya’s room after the Math received Muslim terrorist threats.

The current Shankaracharya of Puri, Nischalananda Sarasvati, inherited the position from the man who inherited it from Tirthaji. He is proud of Tirthaji’s mathematical legacy, and has published five books on the Vedic approach to numbers and calculation. On reaching the Math we were ushered into the room the Shankaracharya uses for his audiences. The only pieces of furniture were an antique sofa with deep red upholstery and, immediately in front of it, a low chair with a large seat and wooden back covered in a red shawl: the Shankaracharya’s throne. We sat facing it, cross-legged on the floor, and waited for the holy man to arrive.

Sarasvati entered the room, wearing a faded pink robe. His senior disciple stood up to recite some religious verses, and then Sarasvati clasped his hands in prayer, touching the image of Shankara on the back wall. He had blue eyes, a white beard and a light-skinned, bald pate. Sitting down in a half lotus on his throne, he assumed an expression between serene and glum. As the session was about to begin, a man in blue robes dived in front of me, throwing himself prostrate before the throne with outstretched hands. Sighing like an exasperated grandfather, taracharya nonchalantly shooed him away.

Religious procedure requires the Shankaracharya to speak Hindi, so I used his senior disciple as an interpreter. My first question was ‘How is maths linked to spirituality?’ After several minutes the reply came back. ‘In my opinion, the creation, the standing and the destruction of this whole universe happens in a very mathematical form. We do not differentiate between mathematics and spirituality. We see mathematics as the fountainhead of Indian philosophies.’

Sarasvati then told a story about two kings who met in a forest. The first king told the other that he could count all the leaves on a tree just by looking at it. The second king doubted him and started tearing off the leaves to count them one by one. When he had finished he arrived at the precise number given by the first king. Sarasvati said the story was evidence that the ancient Indians had the ability to count large numbers of objects by looking at them as a whole instead of enumerating them individually. This and many other skills from that era, he added, had been lost. ‘All these lost sciences can be regained by the help of serious contemplation, serious meditation and serious effort,’ he said. The process of studying the ancient scriptures with the intention of rescuing ancient knowledge, he added, is exactly what Tirthaji had done with mathematics.

During the interview the room filled up with about 20 people, who sat silently as the Shankaracharya spoke. As the session drew to a close, a middle-aged software consultant from Bangalore asked a question about the significance of the number 1062. The number was in the Vedas, he said, so it had to mean something. The Shankaracharya agreed. It was in the Vedas and, yes, it had to mean something. This prompted a discussion about how the Indian government is neglecting the country’s heritage, and the Shankaracharya lamented that he spent most of his energy in trying to protect traditional culture so he could not devote more time to maths. This year he had managed only 15 days.

Over breakfast the next day I asked the computer consultant about his interest in the number 1062, and he answered with a lecture on the scientific achievements of ancient India. Thousands of years ago, he said, Indians understood more about the world than what is known today. He mentioned that they flew aeroplanes. When I asked if there was any proof of this, he replied that stone engravings of millennia-old aircraft have been found. Did these planes use the jet engine? No, he said, they were powered using the Earth’s magnetic field. They were made from a composite material and flew at a low speed, between 100 and 150kmph. He then became increasingly annoyed by my questions, interpreting my desire for proper scientific explanations as an affront to Indian heritage. Eventually, he refused to speak to me.

While Vedic science is fantastical, occultist

and barely credible, Vedic Mathematics stands up to scrutiny, even

though the sutras are mostly so vague as to be meaningless and to

accept the story of their origin in the Vedas requires the

suspension of disbelief. Some of the techniques are so specific as

to be nothing more than curiosities – such as a tip for calculating

the fraction  in decimal. But some are very neat indeed.

in decimal. But some are very neat indeed.

Consider the example of 57× 43 from earlier. The standard method of multiplying these numbers is to write down two intermediary lines, and then add them:

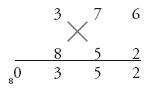

Using the third sutra, Vertically and Cross-wise, we can find the answer quite handily as follows.

Step 1: Write the numbers on top of each other:

|

|

|

|

Step 2: Multiply the digits in the right-hand column: 7×3 = 21. The final digit of this number is the final digit of the answer. Write it below the right-hand column, and carry the 2.

Step 3: Find the sum of the cross-wise products: (5 × 3) + (7 × 4) = 15 + 28 = 43. Add the 2 that is carried from the previous step to get 45. The final digit of this number, the 5, is written underneath the left-hand column, with 4 carried.

Step 4: Multiply the digits in the left-hand column, 5×4 = 20. Add the 4 that has been carried to make 24, to give the final answer:

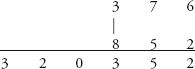

The numbers have been multiplied vertically and cross-wise, as the sutra said on the tin. This method can be generalized to multiplications of numbers of any size. All that changes is that more numbers need to be vertically and cross-multiplied. For example, 376×852:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Step 1: We start with the right column: 6×2 = 12

Step 2: Then the sum of the cross-products between the units and the tens column, (7 × 2) + (6 × 5) = 44, plus the 1 carried above. This is 45.

Step 3: Now we move to the cross-products between the units and the hundreds column, and add them to the vertical product of the tens column, (3 × 2) + (8 × 6) + (7 × 5) = 89, plus the 4 carried above. This is 93.

Step 4: Moving leftwards, we now cross-multiply the first two columns: (3 × 5) + (7 × 8) = 71, plus the 9 carried above. This is 80.

Step 5: Finally, we find the vertical product of the left column, 3 × 8 = 24, plus 8 carried above. This is 32. The final answer: 320,352.

Vertically and Cross-wise, or ‘cross-multiplication’, is faster, uses less space and is less laborious than long multiplication. Kenneth Williams told me that whenever he explains the Vedic method to school pupils they find it easy to understand. ‘They can’t believe they weren’t taught it before,’ he said. Schools favour long multiplication because it spells out every stage of the calculation. Vertically and Cross-wise keeps some of the machinery hidden. Williams thinks this is no bad thing, and may even help less bright pupils. ‘We have to steer a path and not insist that kids have to know everything all of the time. Some kids need to know how [multiplication] works. Some don’t want to know how it works. They just want to be able to do it.’ If a child ends up not being able to multiply because the teacher insists on teaching a general rule that he or she cannot grasp, he said, then the child is not being educated. For the smarter kids, added Williams, Vedic Maths brings arithmetic alive. ‘Mathematics is a creative subject. Once you have a variety of methods, children realize you can invent your own and they become inventive too. Maths is a really fun, playful subject and [Vedic Maths] brings out a way to teach it that way.’

My first audience with the Shankaracharya had not covered all intended topics of discussion, so I was granted a second one. At the beginning of the session, the senior disciple had an announcement to make: ‘We would like to say something about zero,’ he said. The Shankaracharya then spoke for about ten minutes in Hindi in an animated manner, with the disciple then translating: ‘The present mathematical system considers zero as a non-existent entity,’ he declared. ‘We want to rectify this anomaly. Zero cannot be considered a non-existent entity. The same entity cannot be existing in one place and non-existing somewhere else.’ The thrust of the Shankaracharya’s argument was, I think, the following: people consider the 0 in 10 to exist, but 0 on its own not to exist. This is a contradiction – either something exists or it does not. So zero exists. ‘In Vedic literature zero is considered as the everlasting number,’ he said. ‘Zero cannot be annihilated or destroyed. It is the indestructible base. It is the basis of everything.’

By now I was used to the Shankaracharya’s distinctive mix of mathematics and metaphysics. I had given up asking him to clarify certain points since by the time my comments had been translated into Hindi, discussed and then translated back, the answers inevitably added to my confusion. I decided to stop concentrating on the details of his speech, and let the translated words just float over me. I looked at the Shankaracharya closely. He was wearing an orange robe today, tied with a big knot behind his neck, and his forehead had been daubed with beige paint. I wondered what it would be like to live the way he did. I had been told that he sleeps in an unfurnished room, eats the same bland curry every day, and that he has no need or desire for possessions. Indeed, at the beginning of the session a pilgrim had approached him to give him a bowl of fruit, and as soon as he received it, he had given the fruit away to the rest of us. I got a mango, which was by my feet.

Trying to experience the Shankaracharya’s wisdom in a different way, I thought of the phrase ‘zero is an existent entity’ and repeated it like a mantra in my head. I let go. Suddenly I am lost in my thoughts. And it all makes sense. ‘Zero is an existent entity’ is not just the Shankaracharya’s mathematical point of view, but a pithy phrase of self-description. Sitting in front of me is Mr Zero himself, the embodiment of shunya in flesh and bone.

It was a moment of clarity, maybe even of enlightenment. Nothing was not nothing in Hindu thought. Nothing was everything. And the monastic, self-abnegating Shankaracharya was a perfect ambassador for this nothingness. I thought about the deep connection between Eastern spirituality and mathematics. Indian philosophy had embraced the concept of nothingness just as Indian maths had embraced the concept of zero. The conceptual leap that led to the invention of zero happened in a culture that accepted the void as the essence of the universe.

The symbol that emerged in ancient India for zero perfectly encapsulated the Shankaracharya’s overriding message that mathematics cannot be separated from spirituality. The circle, 0, was chosen because it portrays the cyclical movements of the face of heaven. Zero means nothing, and it means eternity.

Pride in the invention of zero has helped make mathematical excellence an aspect of Indian national identity. Schoolchildren must learn their times tables up to 20, which is twice as high as I was taught growing up in the UK. In previous decades Indians were required to learn their tables up to 30. One of India’s top non-Vedic mathematicians, S.G. Dani, attested to this: ‘As a child I did have this impression of mathematics being extremely important,’ he told me. It was always common for elder people to set children mathematical challenges, and it was greatly appreciated if they got the answers right. ‘Irrespective of whether it is useful or not, maths is something that is valued in India by one’s peer group and friends.’

Dani is senior professor of mathematics at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Bombay. He has an academic’s comb-over frizz, rimmed tortoiseshell glasses and a moustache that frames the length of his upper lip. And he is no fan of Vedic Mics; he neither believes that Tirthaji’s arithmetical methods can be found in the Vedas nor does he believe it is particularly helpful to say that they do. ‘There are many better ways to bringing interest into mathematics than resorting to inputting them into ancient texts,’ he said. ‘I don’t believe that they are making mathematics interesting. The selling point is that these algorithms make you fast, not that it makes it interesting, not that it makes you internalize what is going on. The interest is in the end, not the process.’ He is doubtful they do make calculation quicker, since real life does not throw up such perfectly formed problems as finding the decimal breakdown of 1/19. At the end of the day, he added, the conventional method is more convenient.

So, I was surprised that Dani spoke empathetically of Tirthaji’s mission with Vedic Maths. Dani related to Tirthaji on an emotional level. ‘The dominant feeling that I had for him is that he had this inferiority complex that he was trying to conquer. As a child I also had this kind of attitude. In India in those days [shortly after Independence] there was a strong feeling that we needed to get back [from the British] what we lost by hook or by crook. It was mostly in terms of artefacts, stuff that the British might have taken away. Because we lost such a lot, I thought we should have the equivalent back of what we lost.

‘Vedic Mathematics is a misguided attempt to claim arithmetic back for India.’

Some of the tricks of Vedic Mathematics are so simple that I wondered if I might come across them anywhere else in arithmetical literature. I thought that Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci would be a good place to start. When I got back to London I found a copy at the library, opened the chapter on multiplication and Fibonacci’s first suggested method is none other than…Vertically and Cross-wise. I did some more research and discovered that multiplication using All from 9 and the last from 10 was a favoured technique in several books from sixteenth-century Europe. (In fact, it has been suggested that both methods might have influenced the adoption of×as the multiplication sign. When×made its first appearance as a notation for multiplication in 1631, books had already been published illustrating the two multiplication methods with large ×s drawn as cross-lines.)

Tirthaji’s Vedic Mathematics is, it would seem, at least in part, a rediscovery of some very common Renaissance arithmetical tricks. They may or may not have come from India originally, but whatever their provenance, the charm of Vedic Mathematics for me is the way it encourages a childlike joy in numbers and the patterns and symmetries they hold. Arithmetic is essential in daily life and important to do properly, which is why we are taught it so methodically at school. Yet in our focus on practicalities we have lost sight of quite how amazing the Indian number system is. It was a dramatic advance on all previous counting methods and has not been improved upon in a thousand years. We take the decimal place-value system for granted, without realizing how versatile, elegant and efficient it is.