The x-factor

Mathematicians tend to like magic tricks. They can be fun and often conceal interesting theory. Here’s a classic trick that’s also a neat way of appreciating the virtues of algebra. Start by choosing any three-digit number in which the first and last digits differ by at least two – for example, 753. Now, reverse this number to get 357. Subtract the smaller from the larger: 753 – 357 = 396. Finally, add this number to its reverse: 396 + 693. The sum you get is 1089.

Try it again, with a different number, say 421.

421 – 124 = 297

297 + 792 = 1089

The answer is the samIn fact, no matter what three-digit number you start with, you always end up with 1089. As if by magic, 1089 is conjured out of nowhere, a rock in the shifting sands of randomly chosen numbers. Though it is perplexing to think that we get to the same result from any starting point after only a few simple operations, there is an explanation, and we’ll get to it shortly. The mystery of the recurrent 1089 is almost instantly unravelled when the problem is written in symbols rather than in numbers.

While using numbers for the purposes of entertainment has been a consistent theme of mathematical discovery, maths only properly got started as a tool for solving practical problems. The Rhind Papyrus, which dates back to around 1600 bc, is the most comprehensive surviving mathematical document from ancient Egypt. It contains 84 problems covering areas such as surveying, accounting, and how to divide a certain number of loaves among a certain number of men.

The Egyptians stated their problems

rhetorically. Problem 30 of the Rhind Papyrus asks, ‘If the scribe

says, What is the heap of which  will make ten, let him hear.’

The ‘heap’ is the Egyptian term for the unknown quantity, which we now refer to as

x, the fundamental and

essential symbol of modern algebra. Nowadays we would say that

Problem 30 is asking: What is the value of x such that

will make ten, let him hear.’

The ‘heap’ is the Egyptian term for the unknown quantity, which we now refer to as

x, the fundamental and

essential symbol of modern algebra. Nowadays we would say that

Problem 30 is asking: What is the value of x such that  multiplied by

x is 10. To put it more

concisely: What is x such

that (

multiplied by

x is 10. To put it more

concisely: What is x such

that ( )

x = 10?

)

x = 10?

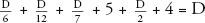

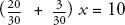

Because the Egyptians didn’t have the symbolic tools that we have now, such as brackets, equal signs, or xs, they solved the above question using trial and error. Estimating for the heap, they then worked out the answer. The method is called the ‘rule of false position’ and is rather like playing golf. Once you are on the green, it’s easier to see how to get the ball into the hole. Similarly, once you have an answer, even a wrong answer, you know how to get closer to the right one. By comparison, the modern method of solution is to combine the fractions in the equation with the variable x, so that:

x = 10

x = 10

Which is the same as:

Or:

Which further reduces to:

And finally:

Symbolic notation makes life so much easier.

The Egyptian hieroglyph for addition was

, a pair

of legs walking from right to left. Subtraction was

, a pair

of legs walking from right to left. Subtraction was  , a pair of legs

walking from left to right. As number symbols evolved from tally

notches to numerals, so the symbols for arithmetical operations

also evolved.

, a pair of legs

walking from left to right. As number symbols evolved from tally

notches to numerals, so the symbols for arithmetical operations

also evolved.

Still, the Egyptians had no symbol for the

unknown quantity, and neither did Pythagoras or Euclid. For them,

maths was geometric, tied to what was constructible. The unknown

quantity required a further level of abstraction. The first Greek

mathematician to introduce a symbol for the unknown was Diophantus,

who used the Greek letter sigma,  . For the square of the

unknown number he used

. For the square of the

unknown number he used  Y, and for the cube

he used KY. While his notation was a

breakthrough in its time, since it meant problems could be

expressed more concisely, it was also confusing since, unlike the

case with x,

x2 and x3, there was

no obvious visual connection between

Y, and for the cube

he used KY. While his notation was a

breakthrough in its time, since it meant problems could be

expressed more concisely, it was also confusing since, unlike the

case with x,

x2 and x3, there was

no obvious visual connection between  and its powers

and its powers  Y and KY. Despite

his symbols’ shortcomings, however, he is nevertheless remembered

as the father of algebra.

Y and KY. Despite

his symbols’ shortcomings, however, he is nevertheless remembered

as the father of algebra.

Diophantus lived in Alexandria sometime between the first and the third centuries ce. Nothing else is known of his personal life except for the following riddle, which appeared in a Greek collection of puzzles and is said to have been inscribed on his tomb:

God vouchsafed that he should be a boy for the sixth part of his life; when a twelfth was added, his cheeks acquired a beard; He kindled for him the light of marriage after a seventh, and in the fifth year after his marriage He granted him a son. Alas! Late-begotten and miserable child, when he had reached the measure of half his father’s life, the chill grave took him. After consoling his grief by the science of numbers for four years he reached the end of his life.

The words are perhaps less an accurate description of Diophantus’s family circumstances than they are a tribute to the man whose innovative notation presented new methods for solving problems like the one above. The ability to express mathematical sentences clearly, devoid of confusing verbiage, opened the doors to new techniques. Before I show how to solve the epitaph, let’s look at some of them.

Algebra is the generic term for the maths of equations, in which numbers and operations are written as symbols. The word itself has a curious history. In medieval Spain, barbershops displayed signs saying Algebrista y Sangrador. The phrase means ‘Bonesetter and Bloodletter’, two trades that used to be part of a barber’s repertoire. (This is why a barber’s pole has red and white stripes – the red symbolizes blood, and the white symbolizes the bandage.)

The root of algebrista is the Arabic al-jabr, which, in addition to referring to crude surgical techniques, also means restoration or reunion. In ninth-century Baghdad, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi wrote a maths primer entitled Hisab al-jabr w’al-muqabala, or Calculation by Restoration and Reduction. In it, he explains two tich, iques for solving arithmetical problems. Al-Khwarizmi wrote out his problems rhetorically, but here, for ease of understanding, they are expressed in modern symbols and terminology.

Consider the equation A = B – C.

Al-Khwarizmi described al-jabr, or restoration, as the process by which the equation becomes A + C = B. In other words, a negative term can be made positive by resetting it on the other side of the equal sign.

Now, consider the equation A = B + C.

Reduction is the process that turns the equation into A – C = B.

Thanks to modern notation, we can now see that both restoration and reduction are examples of the general rule that whatever you do to one side in an equation, you must do to the other as well. In the first equation we added C to both sides. In the second equation we subtracted C from both sides. Because by definition the expressions on either side of an equation are equal, they must continue to be equal when another term is simultaneously added to or subtracted from either side. It follows that if we multiply one side by an amount, we must multiply the other by the same amount, and the same applies for division and other operations.

The equals sign is like a picket fence separating the gardens of two very competitive families. Whatever the Joneses do to their garden, the Smiths next door will do exactly the same.

Al-Khwarizmi wasn’t the first person to use restoration and reduction – these operations could also be found in Diophantus; but when Al-Khwarizmi’s book was translated into Latin, the al-jabr in the title became algebra. Al-Khwarizmi’s algebra book, together with another one he wrote on the Indian decimal system, became so widespread in Europe that his name was immortalized as a scientific term: Al-Khwarizmi became Alchoarismi, Algorismi and, eventually, algorithm.

Between the fifteenth and seventeenth

centuries mathematical sentences moved from rhetorical to symbolic

expression. Slowly, words were replaced with letters. Diophantus

might have started letter symbolism with his introduction of

for the

unknown quantity, but the first person to effectively popularize

the habit was François Viète in sixteenth-century France. Viète

suggested that upper-case vowels – A, E, I, O, U – and Y be used

for unknown quantities, and that the consonants B, C, D, etc., be

used for known quantities.

for the

unknown quantity, but the first person to effectively popularize

the habit was François Viète in sixteenth-century France. Viète

suggested that upper-case vowels – A, E, I, O, U – and Y be used

for unknown quantities, and that the consonants B, C, D, etc., be

used for known quantities.

Within a few decades of Viète’s death, René Descartes published his Discourse on Method. In it, he applied mathematical reasoning to human thought. He started by doubting all of his beliefs and, after stripping everything away, was left with only certainty that he existed. The argument that one cannot doubt one’s own existence, since the process of thinking requires the existence of a thinker, was summed up in the Discourse as I think, therefore I am. The statement is one of the most famous quotations of all time, and the book is considered a cornerstone of Western philosophy. Descartes had originally intended it as an introduction to three appendices of his other scientific works. One of them, La Géométrie, was equally a landmark in the history of maths.

In La Géométrie Descartes introduces what has become standard algebraic notation. It is the first book that looks like a modern maths book, full of as, bs and cs and xs, ys and zs. It was Descartes’s decision to use lower-case letters from the beginning of the alphabet for known quantities, and lower-case letters from the end of the alphabet for the unknowns. When the book was being printed, however, the printer started to run out of letters. He enquired if it mattered if x, y or z was used. Descartes replied not, so the printer chose to concentrate on x since it is used less frequently in French than y or z. As a result, x became fixed in maths – and the wider culture – as the symbol for the unknown quantity. That is why paranormal happenings are classified in the X-Files and why Wilhelm Röntgen came up with the term X-ray.

Were it not for issues of limited printing stock, the Y-factor could have become a phrase to describe intangible star quality and the African-American political leader might have gone by the name Malcolm Z.

With Descartes’ symbology, all traces of rhetorical expression had been expunged.

The equation that Luca Pacioli in 1494 would have expressed as: 4 Census p 3 de 5 rebus ae 0

and Viète would have written in 1591 as: 4 in A quad – 5 in A plano + 3 aequatur 0

in 1637 Descartes had nailed as: 4x2 – 5x + 3 = 0

Replacing words with letters and symbols was more than convenient shorthand. The symbol x may have started as an abbreviation for ‘unknown quantity’, but once invented, it became a powerful tool for thought. A word or an abbreviation cannot be subjected to mathematical operations in the way that a symbol such as x can. Numbers made counting possible, but letter symbols took mathematics into a domain far beyond language.

When problems were expressed rhetorically, as in Egypt, mathematicians used ingenious, but rather haphazard, methods to solve them. These early problem-solvers were like explorers stuck in a fog with few tricks to help them move about. When a problem was expressed using symbols, however, it was as though the fog lifted to reveal a precisely defined world.

The marvel of algebra is that once a problem is restated in symbolic terms, often it is almost solved.

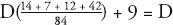

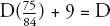

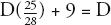

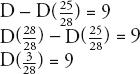

For example, let’s re-examine Diaphantus’s epitaph. How old was he when he died? Translating that statement, using the letter D to symbolize his age when he died, the epitaph says that for D—6 years he was a boy, that another D—12 years passed before he sprouted facial hair, and that he wed after another D—7. Five years after that he had a son, who lived for D—2 years, and four years later Diophant us himself breathed his last. The sum of all these time intervals adds up to D, since D is the number of years Diophantus lived. So:

The lowest common denominator of the fractions is 84, so this becomes:

Which can be rearranged as:

Or:

Which is:

Moving the Ds to the same side:

Multiplying out:

The father of algebra died aged 84.

We can now return to the trick at the start of the chapter. I asked you to name a three-digit number for which the first and last digits differed by at least two. I then asked you to reverse that number to give you a second number. After that, I asked you to subtract the smaller number from the larger number. So, if you chose 614, the reverse is 416. Then, 614 – 416 = 198. I then asked you to add this intermediary result to its reverse. In the above case, this is 198 + 891.

As before, the answer is 1089. It always will be, and algebra tells you why. First, though, we need to find a way of describing our protagonist, the three-digit number in which the first and last digits differ by at least two.

Consider the number 614. This is equal to 600 + 10 + 4. In fact, any three-digit number written abc can be written 100a + 10b + c (note: abc in this case is not a×b×c). So, let’s call our initial number abc, where a, b and c are single digits. For the sake of convenience, make a bigger than c.

The reverse of abc is cba which can be expanded as 100c + 10b + a.

We are required to subtract cba from abc to give an intermediary result. So abc – cba is:

(100a + 10b + c) – (100c + 10b + a)

The two b terms cancel each other out, leaving an intermediary result of:

99ac, or

99(a – c)

At a basic level algebra doesn’t involve any special insight, but rather the application of certain rules. The aim is to apply these rules until the expression is as simple as possible.

The term 99(a – c) is as neatly arranged as it can be.

Since the first and last digits in abc differ by at least 2, then a – c is either 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 or 8.

So, 99(a – c) is one of the following: 198, 297, 396, 495, 594, 693 or 792. Whatever three-figure number we started with, once we have subtracted it from its reverse, we have an intermediary result that is one of the above eight numbers.

The final stage is to add this intermediary number to its reverse.

Let’s repeat what we did before and apply it to the intermediary number. We’ll call our intermediary number def, which is 100d + 10e + f. We want to add def to fed, its reverse. Looking closely at the list of possible intermediary numbers above, we see that the middle number, e, is always 9. And also that the first and third numbers always add up to 9, in other words d + f = 9. So, def + fed is:

100d + 10e + f + 100f + 10e + d

Or:

100(d + f ) + 20e + d + f

Which is:

(100 × 9) + (20 × 9) + 9

Or:

900 + 180 + 9

Hey presto! The total is 1089, and the riddle is laid bare.

The surprise of the 1089 trick is that from a randomly chosen number we can always produce a fixed number. Algebra lets us see beyond the legerdemain, providing a way to go from the concrete to the abstract – from tracking the behaviour of a specific number to tracking the behaviour of any number. It is an indispensable tool, and not just for maths. The rest of science also relies on the language of equations.

In 1621, a Latin translation of Diophantus’s masterpiece Arithmetica was published in France. The new edition rekindled interest in ancient problem-solving techniques, which, combined with better numerical and symbolic notation, ushered in a new era of mathematical thought. Less convoluted notation allowed greater clarity in descrig problems. Pierre de Fermat, a civil servant and judge living in Toulouse, was an enthusiastic amateur mathematician who filled his own copy of Arithmetica with numerical musings. Next to a section dealing with Pythagorean triples – any set of natural numbers a, b and c such that a2 + b2 = c2, for example 3, 4 and 5 – Fermat scribbled some notes in the margin. He had noticed that it was impossible to find values for a, b and c such that a3 + b3 = c3. He was also unable to find values for a, b and c such that a4 + b4 = c4. Fermat wrote in his Arithmetica that for any number n greater than 2, there were no possible values a, b and c that satisfied the equation an + bn = cn. ‘I have a truly marvellous demonstration of this proposition which this margin is too narrow to contain,’ he wrote.

Fermat never produced a proof – marvellous or otherwise – of his proposition even when unconstrained by narrow margins. His jottings in Arithmetica may have been an indication that he had a proof, or he may have believed he had a proof, or he may have been trying to be provocative. In any case, his cheeky sentence was fantastic bait to generations of mathematicians. The proposition became known as Fermat’s Last Theorem and was the most famous unsolved problem in maths until the Briton Andrew Wiles cracked it in 1995. Algebra can be very humbling in this way – ease in stating a problem has no correlation with ease in solving it. Wiles’s proof is so complicated that it is probably understood by no more than a couple of hundred people.

Improvements in mathematical notation enabled the discovery of new concepts. The logarithm was a massively important invention in the early seventeenth century, thought up by the Scottish mathematician John Napier, the Laird of Merchiston, who was, in fact, much more famous in his lifetime for his work on theology. Napier wrote a best-selling Protestant polemic in which he claimed that the Pope was the Antichrist and predicted that the Day of Judgement would come between 1688 and 1700. In the evening he liked to wear a long robe and pace outside his tower chamber, which added to his reputation as a necromancer. He also experimented with fertilizers on his vast estate near Edinburgh, and came up with ideas for military hardware, such as a chariot with a ‘moving mouth of mettle’ that would ‘scatter destruction on all sides’ and a machine for ‘sayling under water, with divers and other strategems for harming of the enemyes’ – precursors of the tank and the submarine. As a mathematician, he popularized the use of the decimal point, as well as coming up with the idea of logarithms, coining the term from the Greek logos, ratio, and arithmos, number.

Don’t be put off by the following definition: the logarithm, or log, of a number is the exponent when that number is expressed as a power of 10. Logarithms are more easily understood when expressed algebraically: if a = 10b, then the log of a> is b.

|

So, log 10 = 1 |

(because 10 = 101) |

|

log 100 = 2 |

(because 100 = 102) |

|

log 1000 = 3 |

(because 1000 = 103) |

|

log 10,000 = 4 |

(because 10,000 =104) |

Finding the log of a number is self-evident if the number is a multiple of 10. But what if you’re trying to find the log of a number that isn’t a multiple of 10? For example, what is the logarithm of 6? The log of 6 is the number a such that when 10 is multiplied by itself a times you get 6. However, it seems completely nonsensical to say that you can multiply 10 by itself a certain number of times to get 6. How can you multiply 10 by itself a fraction of times? Of course, the concept is nonsensical when we imagine what this might mean in the real world, but the power and beauty of mathematics is that we do not need to be concerned with any meaning beyond the algebraic definition.

The log of 6 is 0.778 to three decimal places. In other words, when we multiply 10 by itself 0.778 times, we get 6.

Here is a list of the logarithms of the numbers from 1 to 10, each to three decimal places.

log 1 = 0

log 2 = 0.301

log 3 = 0.477

log 4 = 0.602

log 5 = 0.699

log 6 = 0.778

log 7 = 0.845

log 8 = 0.903

log 9 = 0.954

log 10 = 1

So, what’s the point of logarithms? Logarithms turn the more difficult operation of multiplication into the simpler process of addition. More precisely, the multiplication of two numbers is equivalent to the addition of their logs. If X × Y = Z, then log X + log Y = log Z.

We can check this equation using the table above.

3×3 = 9

log 3 + log 3 = log 9

0.477 + 0.477 = 0.954

Again,

2×4 = 8

log 2 + log 4 = log 8

0.301 + 0.602 = 0.903

The following method can therefore be used in order to multiply two numbers together: convert them into logs, add them to get a third log, and then convert this log back into a number. For example, what is 2×3? We find the logs of 2 and 3, which are 0.301 and 0.477, and add them, which is 0.788. From the list above, 0.788 is log 6. So, the answer is 6.

Now, let’s multiply 89 by 62.

First, we need to find their logs, which we can do by putting the number into a calculator or Google. Until the late twentieth century, however, the only way of doing this was done by consulting log tables. The log of 89 is 1.949 to three decimal places. The log of 62 is 1.792.

So, the sum of the logs is 1.949 + 1.792 = 3.741.

The number whose log is 3.741 is 5518. This is again found by using the log tables.

So, 89×62 = 5518.

Significantly, the only piece of calculation we have done to work out this multiplication was a fairly simple addition.

Logarithms, wrote Napier, were able to free mathematicians from the ‘tedious expense of time’ and the ‘slippery errors’ involved in the ‘multiplications, divisions, square and cubical extractions of great numbers’. Using Napier’s invention, not only could multiplication be made into the addition of logs, but division was made into the subtraction of logs; calculating of square roots was made into the division of logs by two; and calculating cube roots, into the division of logs by three.

The convenience that logarithms brought made them the most significant mathematical invention of Napier’s time. Science, commerce and industry benefited massively. The German astronomer Johannes Kepler, for example, used logs almost immediately to calculate the orbit of Mars. It has recently been suggested that he might not have discovered his three laws of celestial mechanics without the ease of calculation offered by Napier’s new numbers.

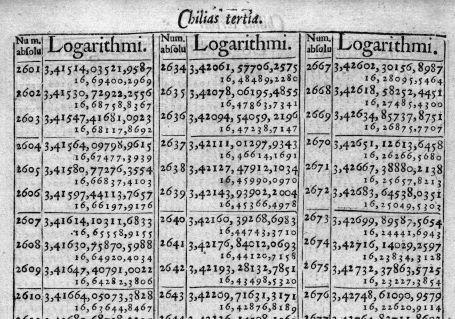

In his 1614 book A Description of the Admirable Table of Logarithmes, Napier used a slightly different version of logarithms than those used in modern mathematics. Logarithms can be expressed as a power of any number, which is called the base. Napier’s system used an unnecessarily complicated base of 1 – 10–7 (which he then multiplied by 107). Henry Briggs, England’s top mathematician in Napier’s day, visited Edinburgh to congratulate the Scot on his discoveries. Briggs went on to simplify the system by introducing base-ten logarithms – which are also known as Briggsian logarithms, or common logarithms, because ten has been the most popular base ever since. In 1617 Briggs published a table of the logs of all numbers from 1 to 1000 to eight decimal places. By 1628 Briggs and the Dutch mathematician Adriaan Vlacq had extended the log table to 100,000, to ten decimal places. Their calculations involved laborious number-crunching – although, once the sums were done correctly, they never needed to be done again.

Page of Briggs’s log tables from 1624.

That is, until 1792, when the young French republic decided to commission ambitious new tables – the log of every number to 100,000 to 19 decimal places,nd rom 100,000 to 200,000 to 24 decimal places. Gaspard de Prony, the man who headed the project, claimed that he could ‘manufacture logarithms as easily as one manufactures pins’. He had a staff of nearly 90 human calculators, many of whom were former servants or wig dressers whose pre-revolutionary skills had become redundant (if not treasonous) in the new regime. Most of the calculations were finished by 1796, but by then the government had lost interest, and de Prony’s gigantic manuscript was never published. Today it is housed in the Paris Observatory.

Briggs’s and Vlacq’s tables remained the basis for all log tables for 300 years, until the Englishman Alexander J. Thompson in 1924 began work manually on a new set accurate to 20 places. Yet instead of giving an old concept a modern sheen, Thompson’s work was already outdated when he finished it, in 1949. By then computers could generate the tables easily.

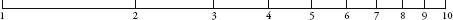

When you plot the digits 1 to 10 on a ruler positioned to their log values, you get the following pattern:

We can carry on like this, say, up to 100.

This is what is known as a logarithmic scale. In the scale, numbers get progressively closer together the higher they are.

Some scales of measurement are logarithmic, which means that for every unit you go up on the scale, it represents a tenfold change in what it is measuring. (In the second scale above, the distance between 1 and 10 is equal to the distance between 10 and 100.) The Richter scale, for example, which measures the amplitude of waves recorded by seismographs, is the most commonly used logarithmic scale. An earthquake that registers 7 on the Richter scale triggers an amplitude that is ten times more than an earthquake that registers a 6.

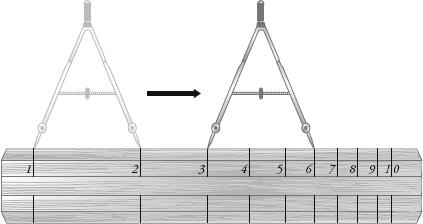

In 1620 the English mathematician Edmund Gunter was the first person to mark the logarithmic scale on a ruler. He noticed that he could multiply by adding lengths of this ruler. If a compass was placed with the left spike at 1, and the right at a, then when the left spike was moved to b, the right spike pointed to a × b. The diagram below shows the compass set to 2 and then positioned with the left spike at 3, putting the right spike at 2×3 = 6.

Gunter multiplication.

Not long afterwards William Oughtred, an Anglican minister, improved on Gunter’s idea. He dispensed with the compasses, instead placing two wooden log scales next to each other to create a device known as the slide-rule. Oughtred devised two styles of slide-rule. One version used two straight rulers and the other used a circular disc with two cursors. But Oughtred, for unknown reasons, didn’t publish news of his invention. In 1630, however, one of his students, Richard Delamain, did. Oughtred was outraged, accusing Delamain of being a ‘pickpurse’, and the feud over the slide-rule’s origins continued until Delamain’s death. ‘This scandall,’ complained Oughtred at the end of his life, ‘hath wrought me much prejudice and disadvantage.’

The slide-rule was a calculating machine of fantastic ingenuity, and while it may now be obsolete it still has fanatical devotees. I visited one of them, Peter Hopp, in Braintree, Essex. ‘Between the 1700s and 1975 every single technological innovation was invented using a slide-rule,’ he told me when he picked me up at the station. Hopp, a retired electrical engineer, is an extremely affable man with wispy eyebrows, blue eyes, and luxurious jowls. He was taking me to see his slide-rule collection, one of the world’s largest, which contains more than a thousand of these forgotten heroes of our scientific heritage. On the drive to his home we chatted about collecting. Hopp said the best stuff was auctioned directly on the internet, where competition inevitably pushed prices higher. A rare slide-rule, he said, can easily cost hundreds of pounds.

When we arrived at his house, his wife made us a cup of tea and we retired to his study, where he presented me with a wooden 1970s Faber-Castell slide-rule with a magnolia-coloured plastic finish. The rule was the size of a normal 30cm ruler and had a sliding middle section. On it, several different scales were marked in tiny writing. It also had a transparent movable cursor marked with a hairline. The shape and feel of the Faber-Castell were deeply evocative of a kind of post-war, pre-computer-age nerdiness – when geeks had shirts, ties and pocket protectors rather than T-shirts, sneakers and iPods.

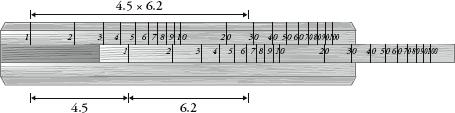

I went to secondary school in the 1980s, by which time slide-rules were no longer used, so Hopp gave me a quick tutorial. He recommended that as a beginner I should use the log scale from 1 to 100 on the main ruler and adjacent log scale from 1 to 100 on the sliding middle section.

Multiplication of two numbers using a slide-rule – which also used to be called a slipstick in the US – is performed by lining up the first number marked out on one scale with the second number marked out on the other scale. You don’t even need to understand what logs are – you just need to slide the middle ruler to the correct position and read the scale.

For example, say I want to multiply 4.5 by 6.2. I need to add the length that is 4.5 on one ruler to the length that is 6.2 on the other. This is done by sliding the 1 on the middle ruler to the point where 4.5 is on the main ruler. The answer to the multiplication is the point on the main ruler adjacent to where 6.2 is on the middle ruler. The diagram below makes this clear:

How to multiply with a slide-rule.

Using the hairline cursor, it is easy to see where one scale meets the other. Moving up from 6.2 on the middle ruler, I can see that it crosses the main ruler at just under 28, which is a correct answer. Slide-rules are not precise machines. Or rather, we are imprecise in our use of them. In reading a slide-rule, we are estimating where a number is on an analogue scale, rather than finding a clear result. Yet despite their inherent imprecision, Hopp said that – for his purposes as an engineer, at least – slide-rules were accurate enough for most uses.

The log scale on the slide-rule I used went from 1 to 100. There are also scales that go from 1 to 10, which are used for greater accuracy because there is more space between the numbers. For this reason, whenever you use a slide-rule it’s always best to convert the original sum into numbers between 1 and 10 by moving the decimal point. For example, in order to multiply 4576 by 6231, I would turn this into the multiplication of 4.576 by 6.231. Once I have the answer, I will move the decimal point six places back to the right. When I put in 4.576 and line it up with 6.231 I get around 28.5, meaning that the answer to 4576×6231 is about 28,500,000. The precise answer, as calculated above, using logs, is 28,513,056. Not a bad estimate. Usually, a slide-rule like the Faber-Castell will give you accuracy to three significant figures – which is often all that is required. What I lost in accuracy, however, I gained in speed – this sum took me under five seconds to do. Using log tables would have taken me ten times longer.

The oldest item in Peter Hopp’s collection was a wooden slide-rule from the early eighteenth century, used by taxmen for making calculations on alcohol volume. Before meeting Hopp, I had been sceptical as to how interesting slide-rule collecting could be as a pastime. At least stamps and fossils can be pretty! Slide-rules, on the other hand, are proudly functional tools of convenience. Hopp’s antique slide-rule, however, was beautiful, with elegantly crafted numbers on fine wood.

Hopp’s vast collection reflected the small improvements that were made over the centuries. In the nineteenth century new scales were added. Peter Roget – whose compulsive list-making (as a coping mechanism for mental illness) resulted in his timeless, classic, definitive Thesaurus – invented the log-log scale, which enabled calculation of fractions of powers, such as 32.5, and square roots. As manufacturing techniques improved, new devices of increasing ingenuity, precision and splendour were designed. For instance, Thacher’s Calculating Instrument looks like a rolling pin on a metal mount, and Professor Fuller’s Calculator has three concentric, hollow brass cylinders and a mahogany handle. A 41ft-helix spirals around the cylinder, giving an accuracy of five significant figures. The Halden Calculex, on the other hand, looks like a timepiece and is made of glass and chromed steel. Slide-rules, I decided, are indeed objects of surprising appeal.

Professor Fuller’s Calculator.

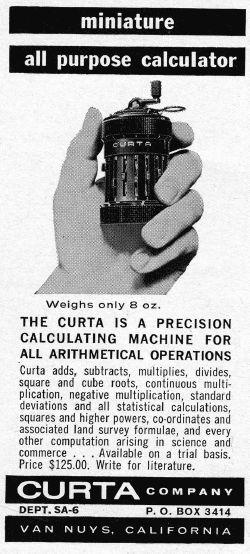

Among these others, I spotted a contraption on Hopp’s shelf that looked like a pepper-grinder, and enquired what it was. He said it was a Curta. The Curta is a black, palm-sized cylinder with a crank handle on the top, and was a unique invention – the only mechanical pocket calculator ever produced. Demonstrating how it worked, Hopp cranked the handle round for one rotation, which reset the machine to zero. Numbers are input by adjusting knobs positioned on the Curta’s side. Hopp set the numbers to 346 and turned the handle once. He then reset the knobs to 217. When he turned the handle again, the sum of both numbers – 563 – was displayed on the top of the machine. Hopp said that the Curta could also subtract, multiply, divide and perform other mathematical operations. It used to be very popular with sports-car enthusiasts, he added. Navigators were able to calculate driving times by cranking it without taking their eyes off the road for too long. It was easier to read than a slide-rule, and less susceptible to bumps in the road.

Although the Curta is not a slide-rule, its ingeniousness at calculating has endeared it to collectors of mathematical instruments. Immediately upon using it, it was my favourite item in Hopp’s collection. For a start, it was a literal take on number-crunching – in went the numbers, and with a crank of the handle, the result appeared. The notion of grinding out an answer, however, was too crude a way to describe a gadget made up of 600 mechanical parts that moved with the precision of a Swiss watch.

Curta advert from 1971.

Even more intriguing, the Curta has a particularly dramatic history. Its inventor, Curt Herzstark designed the prototype for the device while a prisoner at the Buchenwald concentration camp during the final years of the Second World War. Herzstark, an Austrian whose father was Jewish, was given special dispensation to work on his calculating machine because he was known to the camp authorities as an engineering genius. Herzstark was told that if it worked, it would be given to Adolf Hitler as a present – after which he would be declared Aryan, and his life would be spared. When the end of the war came, and Herzstark was freed, he left with his nearly finished plans folded inside his pocket. After several attempts to find an investor, he eventually managed to convince the Prince of Liechtenstein – where the first Curta was manufactured in 1948. From then until the early 1970s, a factory in the principality produced about 150,000 of them. Herzstark lived in an apartment in Liechtenstein until he died, aged 86, in 1988.

Throughout the 1950s and the 1960s the Curta was the only pocket calculator in existence that could produce exact answers. But both the Curta and the slide-rule were all but rendered extinct by an event in the history of arithmetical paraphernalia as cataclysmic as the meteorite that is said to have annihilated the dinosaurs: the birth of the electronic pocket calculator.

It is hard to think of an object that has disappeared so quickly after such a long period of dominance than the slide-rule. For 300 years it reigned supreme until, in 1972, Hewlett-Packard launched the HP-35. The device was promoted as a ‘high precision portable electronic slide-rule’, but it wasn’t like a slide-rule at all. It was the size of a small book with a red LED display, 35 buttons, and an on-off switch. Within a few years it was impossible to buy a general-purpose slide-rule except second-hand, and the only people interested in them were collectors.

Even though the electronic calculator killed off his beloved slipstick, Peter Hopp bears no grudge. He likes to collect early electronic calculators too. When our conversation moved to them, he showed me his HP-35, and started reminiscing about the time he first saw one in the early 1970s. At the time, Hopp was beginning his career at Marconi, the electrical communications firm. One of his colleagues had bought an HP-35, which had cost him £365 – at the time, about half the annual salary of a junior engineer. ‘It was so valuable he kept it locked in his desk and never let anyone use it,’ Hopp said. The colleague, however, had another reason for his secrecy. He believed he had found a way of using the calculator that could save the company 1 percent of its expenditure. ‘He had top-secret meetings with the bosses. It was all hush, hush,’ said Hopp. In fact, though, his colleague had made a mistake. Calculators aren’t perfect instruments – type in 10 and divide by 3. You get 3.3333333. Multiply the result by 3, however, and you do not get back to where you started; rather, you get 9.9999999. Hopp’s colleague had used what was an anomaly in digital calculators to create something from nothing. Hopp recalled the incident with a smile: ‘When the plan was peer-reviewed by someone who used a slide-rule, the improvements were judged illusory.’

The story demonstrates why Hopp laments the demise of the slide-rule. The device provided the user with a visual understanding of numb which meant that even before he had worked out the answer he had a rough idea of what it would be. Nowadays, Hopp said, people plug numbers into a calculator without any intuitive sense of whether the answer is correct.

Still, the digital electronic calculator was an improvement on the analogue slide-rule. The pocket calculator was easier to use, gave precise answers and by 1978 was priced under £5, making it accessible to the general public.

It is now more than three decades since the slipstick slipped away, which means it is surprising to discover that there is, in fact, one situation in the modern world where they are still commonly used. Pilots use them to fly planes. A pilot’s slide-rule is circular, called a ‘whizz wheel’, and measures speed, distance, time, fuel consumption, temperature and air density. In order to qualify as a pilot, you must be proficient with a whizz wheel, which seems utterly strange, bearing in mind the high-end computer technology now used in cockpits. The slide-rule requirement is because pilots must also be able to fly small planes without onboard computers. Yet often pilots flying the most modern jets prefer to use their whizz wheels. Having a slide-rule at hand means you can work out estimates very quickly, and also have a more visual understanding of the numerical parameters of the flight. Flying jets is safer because of pilots’ dexterity with an early seventeenth-century calculating machine.

The astronomically high prices of the early electronic calculators made them luxury business products. The inventor Clive Sinclair called his first product the Executive. One marketing idea involved using geishas to target high-rolling businessmen in Japan. After a night of entertaining, the geisha would whip out a Sinclair Executive from under her kimono so that the host could add up the bill. He would then feel obliged to buy it.

As prices dropped, calculators were seen not

only as arithmetical aides but also as versatile toys.

The Pocket Calculator Game

Book, published in 1975, suggested many recreational

activities for the high-tech electronic marvel. ‘Pocket calculators

are new to our lives. Unknown five years ago, they are becoming as

popular as televisions or hi-fi sets,’ it said. ‘Yet they are

different in that they are not a passive entertainment but require

intelligent input and definite intention for their use. We are not

so much interested in what the pocket calculator can do as we are

in what you can do with your pocket calculator.’ In 1977 the

bestselling Fun & Games with Your

Electronic Calculator included a dictionary of words

that can be made using only the letters O, I, Z, E, h, S, g, L and

B, which are the LED digits  and

and  when turned upside-down. The longest words

are:

when turned upside-down. The longest words

are:

Seven letters:

OBELIZE

ELEgIZE

LIBELEE

OBLIgEE

gLOBOSE

SESSILE

LEgIBLE

BESIEgE

BIggISh

LEgLESS

ZOOgEOg

Eight letters:

ISOgLOSS

hEELLESS

EggShELL

Nine letters:

gEOLOgIZE

ILLEgIBLE

EISEgESIS

Surprisingly, the list does not include ‘BOOBLESS’ – the word whose use by teenage boys to their flat-chested female classmates is probably responsible for turning a generation of girls off mathematics. Still, Fun & Games with Your Electronic Calculator is probably the only numbers book that improves your English more than your arithmetic.

Enthusiasm for playing with one’s calculator was quickly extinguished as more enjoyable electronic games were introduced to the market. It soon became clear that instead of inspiring love of numbers, calculators would have the opposite effect – bringing about a decline in mental arithmetic skills.

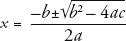

Whereas the logarithm was a brand-new invention made possible by advances in notation, the quadratic equation was an ancient mathematical staple that was spruced up by new symbology. In modern notation, we say that a quadratic equation is one that looks like this:

ax2 + bx + c = 0, where x is the unknown and a, b and c are any constants.

For example, 3x2 + 2x – 4 = 0.

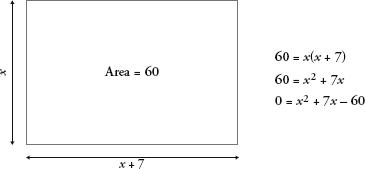

Quadratics, in other words, are equations with an x and an x2. They occur most basically in calculations involving area. Consider the following problem from a Babylonian clay tablet: a rectangular field with area 60 units has one side that is 7 units bigger than the other. How big are the sides of the field? To find the answer we need to sketch the problem, as in the diagram below. The problem reduces to solving the quadratic equation x2 + 7x – 60 = 0.

A convenient feature of quadratic equations is that they can be solved by substituting the values for a, b and c in this one-size-fits-all formula:

The ± means that there are two solutions, one for the formula with a + and one with a –. In the Babylonian problem, a = 1, b = 7 ad c = –60, which gives the two solutions 5 and –12. The negative solution is meaningless when describing area, so the answer is 5.

Quadratics are used in calculations other than those analysing area. Physics was essentially born with Galileo Galilei’s theory of falling bodies, which he supposedly discovered by dropping cannonballs from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The formula he derived to describe the distance of a falling object was a quadratic equation. Since then, quadratics have become so crucial to the understanding of the world that it is no exaggeration to say that they underpin modern science.

Even so, not every problem can be reduced to equations in x2. Some require the next power of x up the scale: x3. These are called cubic equations, and are of the form:

ax3 + bx2 + cx + d = 0, where x is the unknown and a, b, c and d are any constants.

For example, 2x3 – x2 + 5x + 1 = 0.

Cubic equations often emerge with calculations involving volumes, in which one may need to multiply the three dimensions of a solid object. Even though they are just one level up from quadratics, cubic equations are much more difficult to solve. Whereas the quadratic was cracked thousands of years ago – the Babylonians, for example, were able to solve them before algebra had been invented – at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the cubic was still beyond the abilities of mathematicians. All that would change in the year 1535.

In Renaissance Italy the unknown quantity, or x, was called the cosa, or ‘thing’. The science of equations was known as the ‘cossick art’, and the specialist professionals who solved them were ‘cossists’, literally, ‘thingists’. The thingists were not just ivory-tower academics, but also tradesmen who hired out their mathematical skills to a burgeoning commercial class that needed help with sums. Dealing in unknowns was a competitive business, and like master craftsmen, cossists kept their best techniques close to their chests.

Despite their secrecy, however, in 1535 a rumour circulated through Bologna that two cossists had discovered how to solve the cubic equation. For the cossick community, the news was pretty damn exciting. Conquering the cubic would elevate an equation professional above his peers and allow him to charge higher rates.

In modern academia the announcement of the proof of a famous unsolved problem would be presented through the publication of a paper, perhaps at a press conference, but back in the Renaissance the thingists agreed to a public mathematical duel.

On 13 February crowds gathered at the University of Bologna to see Niccolò Tartaglia and Antonio Fiore fight it out. The rules of the contest were that each man would challenge the other with 30 cubic equations. For each equation solved correctly, the solver would win a banquet paid for by his opponent.

The contest ended in a knockout victory for Tartaglia. (His name translates as ‘Stammerer’, and was a nickname he gained thanks to a sabre wound that had left him facially disfiured and with a severe speech impediment.) Tartaglia solved all of Fiore’s problems in two hours, while Fiore was unable to solve even one of Tartaglia’s. As the first person to discover a method of solving cubic equations, Tartaglia was the envy of mathematicians across Europe, but he wouldn’t tell anyone how he did it. In particular, he resisted the entreaties of Girolamo Cardano, who was probably history’s most colourful mathematician of significance.

Cardano was a doctor by profession, and he was internationally known for his cures – he once travelled to Scotland to treat the asthma of the country’s archbishop. He was also a prolific writer. In his autobiography he lists 131 printed books, 111 unprinted books, and 170 manuscripts he rejected himself as not good enough. Consolation, his compendium of advice to the sorrowful, was a bestseller throughout Europe, and is understood by literary scholars to be the book that Hamlet has in his hands during his ‘to be or not to be’ soliloquy. He was also a professional astrologer and claimed to have invented ‘metoposcopy’, the reading of character from the irregularities of one’s face. In mathematics, Cardano’s major contribution was the invention of probability, which I will return to later.

Cardano was desperate to know how Tartaglia had solved the cubic equation, so wrote to him, asking if he could include his cubic solution in a book he was writing. When Tartaglia refused, Cardano asked again, this time promising that he wouldn’t tell anyone else. Again, Tartaglia refused.

Extracting the cubic formula from Tartaglia became an obsession of Cardano’s. He eventually thought up a ruse – he invited Tartaglia to Milan on the pretext of setting up an introduction to a potential benefactor, the governor of Lombardy. Tartaglia accepted the offer, but once he arrived, discovered that the governor was out of town. Instead, he encountered only Cardano. Worn out from Cardano’s incessant pestering, Tartaglia relented, telling Cardano that if he could keep the formula to himself, he would reveal it to him. But when he passed over the information to Cardano, the crafty Tartaglia wrote the solution in a deliberately abstruse way: as a bizarre poem of 25 lines.

Despite this impediment, the multi-talented Cardano deciphered the method, and he almost kept his promise. He told the solution to only one person, his personal secretary, a young boy named Lodovico Ferrari. This turned out to be problematic, not because Ferrari was indiscreet, but because he improved on Tartaglia’s method to find a way to solve quartic equations. These are equations that require the power of x4. For example, 5x4 – 2x3 – 8x2 + 6x + 3 = 0. A quartic may arise when multiplying one quadratic with another.

Cardano was in a fix – he couldn’t publish Ferrari’s discovery without betraying Tartaglia’s word, but neither could he deny Ferrari the public acclamation that he deserved. Cardano, however, managed to find a clever way out. It turned out that Antonio Fiore, the man who lost the cubic duel against Tartaglia, did in fact know how to solve the cubic, and he had learned the method from an older mathematician, Scipione del Ferro, who had told Fiore from his deathbed. Cardano discovered this after approaching del Ferro’s family and going through the late mathematician’s unpublished notes. Cardano thus felt morally justified in publishing the result, crediting del Ferro as the original inventor, and Tartaglia as the reinventor. The method was included in Cardano’s Ars Magna, the most important book on algebra of the sixteenth century.

Tartaglia never forgave Cardano, and died an angry and bitter man. Cardano, however, lived until he was nearly 75. He died on 21 September 1576, the date he had predicted when casting his horoscope years before. Some maths historians claim he was in perfect health and drank poison just to ensure his prediction would come true.

Rather than just looking at equations with higher and higher powers of x, we can also increase complexity by adding a second unknown number, y. The school algebra favourite that is known as simultaneous equations is usually the task of solving two equations that each have two variables. For example:

y = x

y = 3x – 2

To solve the two equations, we substitute the value of the variable in one equation with the value from the other. In this case, since y = x, then:

x = 3x – 2

Which reduces to 2 x = 2

So x = 1, and y = 1

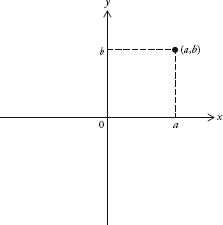

It’s also possible to understand any equation in two variables visually. Draw a horizontal line and a vertical line that intersect. Define the horizontal line as the x-axis, and the vertical line as the y-axis. The axes intersect at 0. The position of any point in the plane can be determined by referencing a point on both axes. The position (a,b) is defined as the intersection of a vertical line through a on the x-axis and a horizontal line through b on the y-axis.

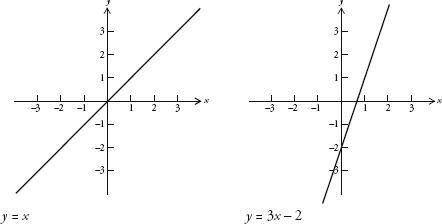

For any equation in x and y, the points where (x,y) has values for x and y that satisfy the equation describe a line on a graph. For example, the points (0,0), (1,1), (2,2) and (3,3) all satisfy our first equation above, y = x. If we mark, or plot, these points on a graph, it becomes clear that the equation y = x generates a straight line, as in the figure below. Likewise, we can draw the second equation, y = 3x – 2. By assigning x a value and then working out what y is, we can establish that the points (0,–2), (1,1), (2,4) and (3,7) are on the line described by this equation. It is also a straight line, which crosses the y-axis at –2, below right:

If we superimpose one of these lines over the other, we see that they cross at the point (1,1). So, we can see that the soluon of simultaneous equations is the coordinates of the point of intersection of the two lines described by those equations.

The idea that lines can represent equations was the major innovation of Descartes’ La Géométrie. His ‘Cartesian’ coordinate system was revolutionary because it forged a thus-far uncharted path between algebra and geometry. For the first time, two separate and distinct areas of study were revealed not only to be linked but also to be alternate representations of each other. One of Descartes’ motivations was to make both algebra and geometry easier to understand because, as he said, independently ‘they extend to only very abstract matters which seem to be of no practical use, [geometry] is always so tied to the inspection of figures that it cannot exercise the understanding without greatly tiring the imagination, while…[algebra] is so subjected to certain rules and numbers that it has become a confused and obscure art which oppresses the mind instead of being a science which cultivates it’. Descartes was no fan of overexertion. He was one of history’s late risers, famously staying in bed until midday whenever he could.

The Cartesian marriage of algebra and geometry is a powerful example of the interplay between abstract ideas and spatial imagery, a recurring theme in mathematics. Many of the most impressive proofs in algebra – such as the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem – rely on geometry. Likewise, now that they could be described algebraically, 2000-year-old geometrical problems were given a new lease of life. One of the most exciting characteristics of maths is how seemingly different topics are interrelated, and how this in itself leads to vibrant new discoveries.

In 1649 Descartes moved to Stockholm to be personal tutor to Queen Christina of Sweden. She was an early bird. Unaccustomed to both the Scandinavian winter and to waking up at 5 a.m., he caught pneumonia shortly after arriving and died.

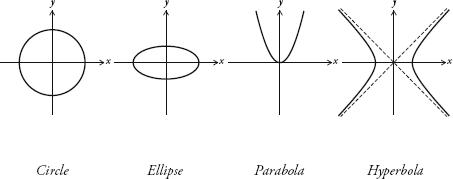

One of the most obvious corollaries of Descartes’ insight that equations in x and y can be written as lines was the recognition that different types of equation produce different types of line. We can start classifying them here:

Equations such as y = x and y = 3x – 2, in which the only terms are x and y, always produce straight lines.

By contrast, equations with quadratic terms – ones that include values for x2 and/or y2 – always produce one of the following four types of curve: circle, ellipse, parabola or hyperbola.

The fact that every circle, ellipse, parabola and hyperbola that can be drawn can be described by a quadratic equation in xs and ys is helpful for science because all these curves are found in the real world. The parabola is the shape that describes the trajectory of an object flying through the air (ignoring air resistance and assuming a uniform gravitational field). When a soccer player kicks a ball, for example, it traces a parabola. The ellipse is the curve that describes how planets orbit around the sun, and the path followed by the shadow of the tip of a sundial during a day is a hyperbola.

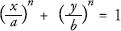

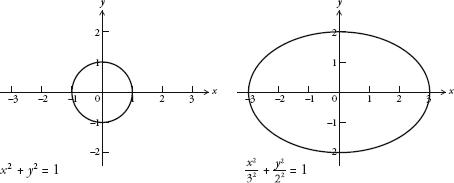

Consider the following quadratic equation, which is like a machine for drawing s and ellipses:

, where a and

b are constants

, where a and

b are constants

The machine has two knobs, one for a and one for b. By adjusting the values of a and b we can create any circle or ellipse with centre 0 that we want.

For example, when a is the same as b the equation is a circle with radius

a. When a = b = 1, the equation is x2 +

y2 = 1 and produces a circle with radius 1, also

called the ‘unit circle’, as shown below left. And when

a = b = 4, the equation is  and this is the circle with

radius 4. If, on the other hand, a and b are different numbers, then the equation

is an ellipse that crosses the x-axis at a, and the y-axis at b. For example, the curve below right is the

ellipse when a = 3 and

b = 2.

and this is the circle with

radius 4. If, on the other hand, a and b are different numbers, then the equation

is an ellipse that crosses the x-axis at a, and the y-axis at b. For example, the curve below right is the

ellipse when a = 3 and

b = 2.

In 1818 the French mathematician Gabriel Lamé started to play around with the formula for the circle and ellipse. He wondered what would happen if he started to tweak the exponent, or power, rather than the values of a and b.

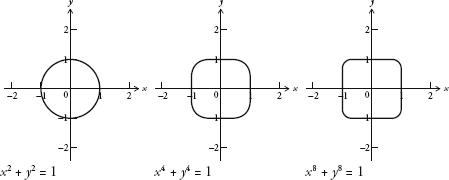

The effect of this adjustment was fascinating. For example, consider the equation xn + yn = 1. When n = 2, this creates the unit circle. Here are the curves produced by n = 2, n = 4 and n = 8:

When n is 4, the curve looks like an aerial view of a Babybel cheese squashed in a box. Its sides have become flattened and there are four rounded corners. It’s as if the circle is trying to become a square. When n is 8, the curve is even more like a square.

In fact, the higher you push n, the closer the curve is to a square. In the limit, when x8 + y8 = 1, the equation is a square. (If anything deserves to be called the squaring of the circle, surely this is it.)

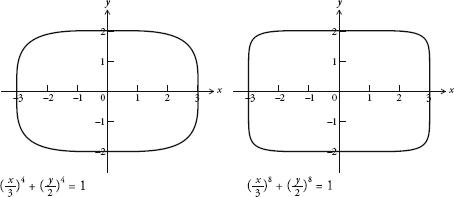

The same thing happens to an ellipse. If we take the ellipse described by ( )n + ( )n = 1, then by increasing the values of n, the ellipse will eventually turn into a rectangle.

In downtown Stockholm there is a main public plaza called Sergels Torg. It’s a large rectangular space, with a pedestrian lower level and a traffic circle on top. It’s the place activists choose to hold political rallies, and where sports fans congregate when Sweden’s national teams win a major event. The plaza’s dominant feature is a cetral section with a sturdy 1960s sculpture that locals love to hate – a 37m-high glass and steel obelisk that lights up at night.

During the late 1950s, when city planners were designing Sergels Torg, they encountered a geometrical problem. What, they asked themselves, is the best shape for a roundabout in a rectangular space? They didn’t want to use a circle because that would not use the rectangular space fully. But nor did they want to use an oval or an ellipse – which do fill the space – because the pointed ends of either shape would hinder the smooth flow of traffic. Searching for an answer, the architects on the project looked abroad, and consulted Piet Hein, a man once described as the third-most famous person in Denmark (after the physicist Niels Bohr and the writer Karen Blixen). Piet Hein was the inventor of the grook, a style of short aphoristic poem that he published in Denmark during the Second World War as a form of passive resistance against Nazi occupation. He was also a painter and mathematician, so possessed the right combination of artistic sensibilities, lateral thinking and scientific understanding to give fresh ideas to Scandinavian planning problems.

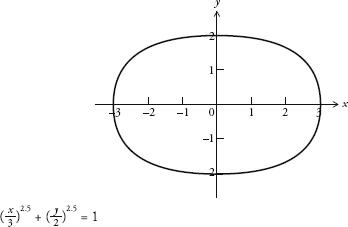

Piet Hein’s solution was to find a shape that was halfway between an ellipse and a rectangle, using simple mathematics. To achieve this, he used the method described on the previous page. He adjusted the exponent in the equation for the ellipse to get a shape that would fit inside the rectangular plaza at Sergels Torg. In algebraic terms, he did what Lamé did by playing around with the n in the ellipse equation:

As I showed previously, increasing the n from 2 to infinity takes you from a circle to a square, or from an ellipse to a rectangle. Piet Hein judged that the value of n such that the curve was the most aesthetic compromise between round and right-angled was when n = 2.5. He could have called his new shape a ‘squircle’. Instead, he called it a superellipse.

More than just an elegant piece of maths, Piet Hein’s superellipse touched on a deeper human theme – the ever-present conflict in our surroundings between circles and straight lines. As he wrote, ‘In the whole pattern of civilization there have been two tendencies, one toward straight lines and rectangular patterns and one toward circular lines.’ His piece continued, ‘There are reasons, mechanical and psychological, for both tendencies. Things made with straight lines fit well together and save space. And we can move easily – physically or mentally – around things made with round lines. But we are in a straitjacket, having to accept one or the other, when often some intermediate form would be better. The superellipse solved the problem. It is neither round nor rectangular, but in between. Yet it is fixed, it is definite – it has a unity.’

Stockholm’s superelliptical roundabout was copied by other architects, most notably in the design for the Azteca stadium in Mexico City – which held the World Cup final in 1970 and 1986. In fact, Piet Hein’s curve spread to fashion, becoming a feature of 1970s Scandinavian furniture design. It’s still possible to buy superelliptic plates, trays and door-handles from the company run by Piet Hein’s son.

Piet Hein’s playful mind did not stop at the superellipse, however. F his next project, he wondered what a three-dimensional version of the shape would look like. The result was halfway between a sphere and a box. He could have called it a ‘sphox’. Instead, he called it a ‘superegg’.

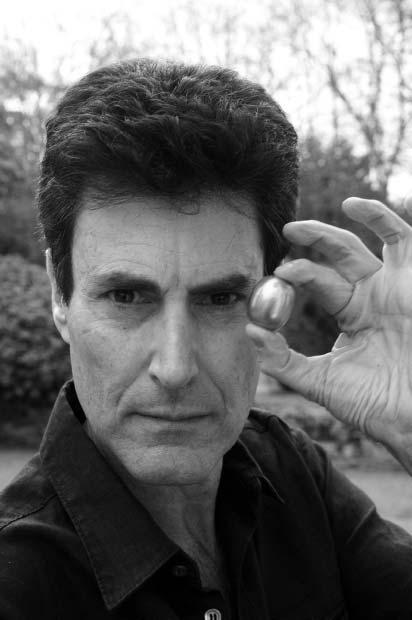

Supereggstatic: Uri Geller.

One unexpected feature of the superegg was that it could stand on its end without falling. In the 1970s Piet Hein marketed super-eggs made out of stainless steel as a ‘sculpture, novelty or a charm’. They are beautiful, curious objects. I have one on my mantelpiece. Uri Geller also has one. John Lennon gave it to him, explaining that he had received the egg from aliens who visited him in his New York apartment. ‘Keep it,’ Lennon told Geller. ‘It’s too weird for me. If it’s my ticket to another planet, I don’t want to go there.’