XII

THE LONGER WINTER TAKES A-DYING, THE MORE spectacular will be the spring. On the last of the days of bitter cold, the land awakens to the morning chorus of the songbirds, and from the bottom of its heart yearns for the rebirth now approaching. There is not long to wait; soon we shall be welcoming the purest of colors, smells, tastes, forms, and combinations, which may yet, in spite of everything, make the world a better place. At times like this it almost seems that nature is trespassing on the territory of art.

In Budapest everyone had a more favorable opinion of Henryk than he had of himself. His lanky form could have been quite manly if he had not been so hunched up and obviously lacking in self-confidence. When he spoke, a few uncertain errrm or hhhhh noises came out first, hopefully harbingers of more meaningful words. If he was excited he chewed his lips incessantly and tore the skin from the surface of his thumb until it bled, and sometimes beyond. Though he strove to speak his father-tongue flawlessly, he often, almost unconsciously, used English expressions in his Hungarian. Most of his statements ended up curling into questions, even if he was 100 percent sure of what he was saying, which was rare.

In company he would sit in the corner, with an offended expression, eyeing those who managed to relax. Very common, that sort of behavior, he said, or rather thought, though not very secretly he envied them. On his Macintosh Classic computer he opened a file in which he wrote diarylike notes, quite unsystematically, whenever the spirit seized him. In Hungary he did this in a Hungarian that was at first strewn with errors. He clung fiercely to his out-of-date computer, and if anyone suggested that he replace it, he would be shocked: “But this is an industrial classic!” pointing out that one of the prototypes had been placed in the Museum of Science and Technology in Washington, D.C.; he had seen it with his very own eyes. He had read three books about the rise of the Macintosh empire: he imagined the two teenagers as, in the garage of the parents of one of them, they put together the user-friendly computer, whose success had laid the foundations of the worldwide megacorporation.

This miraculous tale reminded him of the tales he had been told as a child. At night his father would sit by his bed and, eyes half shut, launch into “once upon a time,” and the littlest boy would set off into the wide, wide world to seek his fortune, a trusty stick in his hand and a satchel on his shoulder, always filled with the ash-baked scone. After exciting adventures he would be rewarded with half the kingdom and the hand of the princess, just as the Macintosh boys won fame and billions of dollars. So—it seems miracles can, and do, still happen.

Henryk was educated at undistinguished public schools. Flatbush Community School and Lee High School had barely any white students apart from himself. In the lower school, black was the typical skin color; in the upper school, it was yellow. He was well versed in their talk, as fluent in black slang as in the nasal drone of the yellow-skinned population. The teachers were glad if they managed to survive the classes without fighting breaking out. Most of them carried weapons or defensive sprays in their pocket or bag.

It was thought that Henryk was a little weak in the head. When asked to solve a problem at the whiteboard he could often only croak; in vain did the teachers chain the felt-tip marker to the board, someone always stole it. The more discerning teachers brought their own, the less discerning gave up using the whiteboard altogether. But the number of discerning teachers in those schools was few. Henryk had three times to endure the disgrace of repeating a year, but somehow, over twelve years, he managed to overcome the tribulations of compulsory school attendance. None of his teachers noticed that he was basically a lad with a good brain and it was only his memory that failed him. Even material he had crammed with utmost attention simply did not stick: by the time his turn came, the numbers and names had become hopelessly confused in his head, though he could remember with crystal clarity on which page of the book the text in question occurred and in what type, color, and layout. He could see it; he just couldn’t read it. At the age of ten he had been given spectacles that he had hoped would help, but they merely enlarged the lines of letters and figures—he still could not read them.

His absent-mindedness was already legend when he was very small. If his grandmother—whom he called Grammy, because of the award—sent him down to the Chinese grocery, where their purchases were put on their account, Henryk nearly always forgot what he was supposed to be buying. His requests to Mr. Shi Chung, whose grandchildren were often his fellow students, were pure guesswork. If Grammy gave him a list, he would leave it at home or lose it. Once in school he had to fill in a form and he left both parents’ names blank, as he could not recall them. His excuse—that they were long dead—was not accepted by Mrs. Marber: “A white Anglo-Saxon Protestant lad should always know of which family he is the scion!”

Henryk would have been glad if he had understood even the word scion, a Middle English word that his teacher had first encountered in Shakespeare. He blinked desperately behind his glasses, as he always did when an answer was expected of him. The unreliability of his memory did not improve with time; in fact, it worsened. He was too scared to utter the names of close acquaintances, lest he get them wrong. He was right; he often did. Even more insurmountable were the barriers presented by numbers. If he had to go to 82 Harvey Avenue, he was bound to wind up at No. 28. In vain did he want to write everything down, because as soon as the figure 82 was uttered in his head it turned into 28 (or 39, or 173), and this was what came to the tip of his pen. He hated to make phone calls, because the integers he read out of his address book disintegrated the moment he lifted the receiver. He would look up the number again, but his memory, like a magnet without strength, dropped the number well before he had to dial. He had to prop the book open and lean it against the phone to ensure that he scanned the right line all the way to the number’s end.

But he could remember images and tunes flawlessly; so he became the pillar of the mezzo section of the school choir. Grammy would have liked him to study music, but there was no money for tuition. The singing teacher at Lee High, Mr. Mustin, sometimes took him in hand, and taught him to play the flute, but Henryk lacked the patience to read music. At the age of ten he scored quite a hit with his freehand drawings and in the pottery class of the high school his jugs and jars made a mark, but he gave up pottery quite soon after Miss Lobello remarked on his thick glasses. There was no denying that by the end of primary school he had reached pebble-glass stage: in the huge lenses his pupils looked like restless fish.

Despite Grammy’s efforts, Henryk did not apply to college upon graduating from high school. He was sure his results would not get him into any but the most mediocre state universities, whose degrees were worth little more than toilet paper. He had two plans of action: 1. He would apply to join the Navy, where they take everyone who can take the strain; a career in the military is not so bad in peacetime. 2. He would apply to work in the lawyer’s office on Roosevelt Avenue (47, or was it 74?), where he liked the look of the well-endowed secretary. In summer he delivered pizzas for Domino’s Pizza, where the basic rule was that if they failed to deliver within thirty minutes of the order being placed, the customer got his pizza free. In the lawyer’s office the secretary nearly always welcomed him with the words “The thirty minutes are up!”—but she was usually joking. Henryk, however, invariably responded: “In that case, your pizza is free … Enjoy your meal, ma’am.” And backed out of the premises, not for a moment lifting his gaze from the woman’s ample cleavage. In his wet dreams he would nuzzle those warm peaks.

Plan A fell through quickly, his pebble glasses causing his rejection. Plan B seemed to be working, however: the secretary passed on his offer to her employer and the firm’s owner called him in for a job interview. “And why have you picked on us to apply to for work?”

“I am attracted by the truth.”

The square-built lawyer gave a nod and offered him the post of bicycle messenger, taking effect on September 15, with two months’ trial, absurd weekly wages, and support of a very low order: “Then we’ll see.”

Henryk accepted. Grammy will be pleased that I’ve got a job, he thought. Anyway, there’s a whole long exciting summer ahead.

He made friends with two boys at school: Koreans of small build, they barely came up to his chin. The two Koreans were planning a backpacking tour of Europe. Henryk worked on Grammy until she agreed to him taking out his savings from the bank, savings built up over several pizza summers, so that he could go with his friends. They crossed the pond on a charter run by a low-cost airline, a student-only flight on which was served neither food nor drink. The Koreans had brought large supplies of food, which they gladly shared with Henryk, though the over-spiced dumplings gave him stomach cramps and he had to line up every half-hour for the toilet in the tail of the plane.

Their route was largely determined by the Youth Hostel Guide: they tried to visit towns where, on the basis of the youth hostel’s price, location, and cleanliness, the editors of the guide gave a high number of points. Not a single hostel in Eastern Europe earned the maximum ten points. The one in Prague was awarded eight, Budapest seven; the latter was available only in the summer, as the rest of the year it was a residence hall. The two Koreans were not interested in Eastern Europe. “Now that there is no Iron Curtain, it must be like Western Europe, only poorer,” said one of them.

Henryk told them that he was of Hungarian origin and would like to see the old country. When the other Korean heard this, he backed off, but in the end he saw that South Tyrol and Italy were also attractive. At this point they were still in Vienna and agreed to meet ten days later in Venice, which, though it lacked a good youth hostel, could not be missed.

Henryk crossed the border from Austria into Hungary in the cab of a German lorry. He thought that he would feel a surge of emotion—but nothing happened. Undistinguished customs buildings, indifferent uniformed guards, similar to other crossing points in Europe; only the lines were longer.

He had mixed fortunes hitchhiking to Budapest. This form of transport, which had been unknown to him, he had read about in the Brooklyn Public Library, in a publication entitled Europe on $25 a Day. In the Netherlands he experienced for the first time how complete strangers would stop and actually give a lift to hitchhikers. He loved it. He could not understand why aging hippies, who were there alongside him thumbing, moaned that the golden days of hitchhiking were over, that drivers were now afraid of hitchhikers. It wasn’t like that in the Seventies! The final leg he did in a car shaped rather like a brick, oddly rounded at the front and back, which gave off a terrible smell. The driver, T-shirted, perhaps only a little older than himself, could manage a few words of English. When Henryk asked about the car, he began to explain it was a Warburg. “East German make.”

“But there is no East Germany now. Or is there?”

“Iz nat. Bat ven dis one made, still wars. Iz two … rhythm.”

“Rhythm?”

“Togeder cam benzin end oil.”

Henryk smiled and nodded vaguely, as if he understood.

When the sign for Budapest first appeared on the motorway, the driver asked him where he was headed. Henryk pointed to the address of the youth hostel in his book.

“Lucky. Heer vee are bifore it.”

The cement block of the hostel in Budaörs reminded Henryk of the public hospital at Queens. The same day in the downstairs café he met a couple of dozen Americans. They took him to the brand-new pubs of the capital, where the punters spoke almost only English. “This is the gold-rush time here,” explained Jeff McPherson, in a strong Irish accent. “Pay a bit of attention and you can make your fortune here!”

Henryk paid a bit of attention. A week later he wrote to Grammy to say he would be staying in Hungary until the end of the summer. He asked her to send him his Macintosh Classic by UPS, which had opened an office in Budapest.

It is fascinating for me to visit the land of my ancestors. I am sorry you are not here with me. Don’t you feel like coming over now? I can send you a plane ticket.

It turns out my Hungarian is a lot better than I thought. Grammy, why don’t we speak Hungarian together? After all, you’re Hungarian too, aren’t you?

Mama and Papa would be open-mouthed: now you can get almost anything here. In places they will even accept my credit card. It’s a shame they never lived to see this.

He often thought of the two little Koreans, wondering how long they had waited for him in St. Mark’s Square by the arcades. He hoped it was not too long.

Grammy’s long reply arrived with unusual speed.

My dear Henryk,

I’m glad you’re enjoying yourself in Budapest. To me, you know, it’s almost a foreign city, for as you know we hail from Szekszárd, in the south of the country, as I told you.

Szekszárd? He could have sworn that he had never heard this before. Is that still inside Hungary? He checked the map.

Szekszárd …

From somewhere in the dust-covered years of his early childhood a little ditty rose to the surface of his consciousness. Szekszárd’s my birthplace, a stage-star’s my lovegrace!—Papa used to say it to Mama when things were still OK. They would laugh at this appropriation of a line from the poet Mihály Babits. He, Henryk, the toddler, tried to repeat after them: Sixard! Sixard!—which Papa liked so much that he would grab him and toss him in the air, with Henryk squealing, Mama squealing, even Grandma squealing. Papa would toss him up again and again, higher and higher as he rhythmically roared: Szek-szárd’s my birth place, a stage-star’s my lovegrace!

Only once did my parents take me up to Budapest, when I was ten, as they were trying to arrange my emigration papers. We stayed in the Hotel Hungária, by the Danube. Go and take a look, and think of me.

Henryk could not fulfill this request. He found no Hotel Hungária on the Danube: its place had been taken by the Forum Hotel and the Intercontinental.

My crazy husband always planned to take us on a grand tour of Europe, the high point of which would have been a trip to Hungary, taking in Szekszárd, which he pronounced Sixard, just as you did when you were small. But he was never able to realize his plan. Like most Indians, he lived in a dream world, not on the ground. I think you don’t even know what he was called. Although I have told you before, you never pay attention. Am I right? You don’t know, do you? Ganesh Kupar. That was his name—may the soil lie light upon him—when I met him in an eatery on Lee Avenue, Brooklyn. I was a dishwasher there and he a waiter. Yes, my dear little Henryk, that’s how our life began. He was a restless man, continually driven by his hot blood, and I could not hold him back from doing anything he wanted to. Before I knew it we were in Delhi, flat broke, in a filthy alleyway, where 70 percent of the inhabitants used the street both as toilet and bedroom. I had to get away from the danger that he signified, back to the U.S. and to my parents. I never married again.

Henryk had a feeling that he had heard his grandfather was from India, but he had never put two and two together and thus realized that this meant he had Indian blood coursing in his veins and that was why his skin was so dark. Most of the cabbies in New York are Indian. Sikh, to be more precise: that is to say, from the military caste. Some even wear their turbans while driving. They are like … at the end of this train of thought the penny finally dropped: So, that’s why … Some days before in a restaurant in Buda the fiddler had asked him: “Are you a Rom?”

“I beg your pardon?”

The bulky fellow nodded significantly as he returned to his band: “The bugger denies it.”

Henryk didn’t know this word.

It’s very kind of you to invite me to come, but I have no wish to stir up in my soul everything that I put the seal on long ago. I doubt if I could speak Hungarian. If Magyar words come into my head, each has some painful memory attached, so I would rather not force the issue. You wouldn’t really understand. Have a good time over there, enjoy life, then come home!

By then Henryk was a salesman in the newly opened showroom of Macintosh Hungary. By August he had advanced to journalist, writing reports for the first English-language weekly, in the “Scenes from the Life of the Capital” column. Of the seven-man team, four were Americans, and of these he spoke the best Hungarian. The cultural column was in the hands of Ann, a blonde with legs reaching up to her armpits, who wrote nearly all the articles. She had two hobbyhorses. She insisted on spelling her name without a final e, unlike most bearers of it; and she insisted with the same intensity on her American colleagues not behaving like dumb assholes in Hungary, but taking an interest in the art, literature, and customs of this small population. As soon as it became clear that Henryk was basically Magyar, she immediately regarded him as a fellow spirit and took him under her wing.

Since I have been living in Budapest, I have every reason to feel satisfied. Everything that did not succeed at home is working out here, better than I could have imagined. Here my shyness and unusual behavior is accepted, including my less than perfect knowledge of the language. My finances are also in order. Without my having to make a particular effort, things are working out by themselves.

Ann crafted his application for a work permit, attaching the recommendation of the chief editor. She also got him a room to rent, though this soon proved superfluous, as he moved in with her. Ann lived out in the Csillaghegy area, renting the loft of a large detached house with a garden. The loft had been converted into a single large space with a gallery kitchen, with only the tiny bathroom hived off in one corner. When Henryk first climbed up the narrow hen-run-like ladder, he could not believe his eyes. While the lower two levels of the building looked very much like those of detached houses in the outer suburbs, in the loft space part of a Scottish castle had been constructed. In the generously sized fireplace, the U-shaped iron arms holding the logs, the bellows, the poker, and the fire tongs could all have come straight from the time of Shakespeare. The oak-paneled, uneven walls were decorated with old firearms and country scenes. There was furniture to match, notably the dining table for twelve with ramrod-straight chairs.

The family whose hospitality Ann enjoyed had built their home by themselves, with their own bare hands, one might say, and when she rented their summer kitchen, there was as yet no roof on the house. The man had been broken down by the many years’ effort he had put into the house, and had retired on health grounds. “That is, he was forced to take early retirement.” Seeing their sad plight, Ann proposed that she would finish off the house, including the loft, in return for living there rent-free until she recouped her costs.

“So how long can you live here without having to pay?”

“Seventy or eighty years for sure.”

Ann’s fellow lodger received Henryk with a warning rumble. The mongrel Bond, James Bond, was pitch-black and the size of a sheep.

“Don’t worry, he won’t hurt you!” Ann reassured him as the dog planted a heavy foreleg on each of Henryk’s shoulders and panted directly in his face. She was right; the dog wanted only to be loved, its massive tail thumping the floor like a flail.

Henryk became fond of the creature, though he was not best pleased when Bond, James Bond, insisted on joining them in bed when they made love. “I haven’t the heart to chase him off. He was a stray, you know, and strays take everything to heart. He has no one apart from me.”

This sentence struck Henryk like a sharp arrow. I, too, am a stray dog, he thought.

In the company of Ann he set off to find the Hungária. But it turned out that Ann was thinking of the old Hungária Café, which was now called the New York. Henryk was resigned to this, but the tall blonde never gave up. In an English book on the history of Budapest she picked up the trail. She read it out to Henryk. “The Hotel Hungária was one of the jewels on the Danube Corso, a much loved rendezvous for the local young people at the time. At the end of the war the Allies bombed it and the ruins were dismantled.”

Henryk did not want to send this news to his grandmother, with whom he exchanged letters once a week. Grammy inquired when her little grandson was coming home, and he replied that he was planning to stay and it would make more sense for Grammy to come to Budapest.

They took Bond, James Bond, for walks by the Danube, and the enormous dog soon became well known on the Csillaghegy stretch of the river. Despite his intimidating appearance, he never troubled other dogs or animals, and was roused to anger only if he thought Ann was in danger. But then he would attack without further ado.

One evening, as they took three-quarters of an hour for their walk, Ann related the story of her parents’ lightning divorce, since which she saw her father twice a year, at Thanksgiving and at Christmas. Her mother lived in Philadelphia; she was an illustrator of children’s books. The actual stories were written by her father, in Florida. Once they had made a great team. Ann was herself the heroine of some of the stories, in her own name, which she enjoyed as a child but later found irritating and even offensive. Since her university years she had drifted away from her parents. Her mother’s small-mindedness she found just as upsetting as her father’s thick-headed stubbornness. Her mother’s parents were Scots, her father’s of Dutch origin; from her she inherited her freckled skin and maize-stalk hair, from him the surname that broke a thousand lips: Schouflakkee.

“So you’re not really Ann Jagger?”

“Yes, I am now. I changed it.”

“Mick Jagger the inspiration?”

“Of course.”

“I would prefer to be Lennon. Henryk Lennon.”

“Go for it!”

When Ann asked him about his family background, Henryk told her the little he knew.

“Would you be interested in looking for your ancestors?”

“How?”

Ann explained that in Hungary it was now possible to go back through the parish registers up to about the middle of the nineteenth century. If you know when and where your father was born, you can find his birth certificate. That will contain some information about both parents, things like place and date of birth, perhaps their address at the time, maybe even their occupation. If you are sufficiently persistent, you can often find the grandparents’ marriage records (you make a guess about the likely wedding date and rifle through those years), in which you can find information about the father and mother of both husband and wife. And so on. “You only come to grief if you’re stuck for the place, because you must look in the district where they were born or married.”

“How do you know all this?”

“I wrote an article about it. The Hungarians have gone crazy about their past. Hordes of them are having their family trees reconstructed, looking for their noble coat-of-arms and their old property deeds.”

Henryk first took the train to Szekszárd. Having the data about Grammy’s birth to hand, he thought he had a pretty straightforward task. He had managed to make himself understood by the clerk in the office, when it turned out that he did not know Grammy’s maiden name. He decided to phone her. His grandmother gave a whoop of joy on hearing his voice. “Henryk! So you are here!”

“No, not yet. Grammy, what was your maiden name?”

“Pardon?”

“Your maiden name! Can you hear me?”

“Yes. Don’t shout.”

“All right, just tell me quickly, because my phone card is running …” The line went dead. He bought another in the shop. “Grammy, please, before it runs …”

“What do you need it for?”

“Complicated. I’ll tell you in a letter, just tell me what it was!”

“No … I’d rather not.”

“Why? Are you ashamed of it?”

“No … but …” Again they were cut off.

I was a little shocked to hear you asking about my maiden name. I am not a criminal to be hunted down (his grandmother wrote in her next letter). To cap it all, I have told you this, too, many times. I was born Rachel Steuer.

“Your grandmother is either German or Jewish,” Ann opined. “I thought as much.”

“Which did you think she was ‘as much’?”

“Jewish.”

“Why?”

“That’s what they’re like.”

“What are they like?”

The girl did not reply.

“You can’t say that sort of thing! That’s the beginning of fascism!”

“No, it’s the beginning of your unbearable oversensitivity!”

“Even an elephant would be offended by this!”

“The shit it would!”

They had such a row that Henryk almost moved out.

On his next trip to Szekszárd he discovered that there had been no fewer than three Rachel Steuers born in Szekszárd on Grammy’s day of birth. The clerk in the office was surprised: “Three Rachel Steuers on the same day in the same small town!” She had an excess of communicativeness and told how she came from Paks, but her parents’ house, where she had been born, was acquired by the state and razed to the ground. “They needed the space, you know, for the Paks nuclear power station.”

Henryk did not know. He hurried to fax the photocopy of the appropriate page of the register to Grammy in Brooklyn, via the Roosevelt Avenue post office. His grandmother’s reply was not long in coming.

As I’ve already told you, I have no interest in my past—thanks, but no thanks. But you were always as mad as a March hare. Have another look at my letter; what I wrote was Steiner—STEINER—not Steuer!

Henryk was ashamed. In his computer he copied this odd-sounding name a hundred times, one under the other, in New York Bold type, half an inch high. Despite this, he was unable to remember it. “Not Steuer, but Stouer!” he said, when Ann asked what his grandmother had written.

In Hungary it’s always third time lucky. It’s a folk saying, I heard it from the doorman. My third trip to Szekszárd had a resulting outcome. That is to say:

Rachel Steiner was born July 3, 1927, in Szekszárd at 6:30 in the morning. Father: Walter Steiner, farrier; mother Gabriella Duba. Both living at No. 18 Retek Street. Father R.C., mother’s religion not stated.

On the mother’s side this is as far as I have got.

Ann clapped her hands in joy: “Farrier, that’s fantastic! Congratulations! Put it on your CV.”

“What exactly is a farrier?” asked Henryk.

As soon as he was told, the scenario began to unfold before him: Walter Steiner, tall, muscular, bare-chested, the face of Marlon Brando, body like Arnold Schwarzenegger, brings the gigantic iron hammer down on an anvil incandescent with heat, pauses a second to take a breath, wipes the sweat from his brow, lowers the hammer, placing it by his feet, just like that statue Henryk saw on Dózsa György Way.

He was constantly sending his CV (in the end he did not put his farrier ancestor on it) to Budapest branches of the large multinationals, because he soon grew bored with journalism. But that was not all he grew bored with. At first he was unwilling to admit it, but his ardor towards Ann was cooling; it was only Bond, James Bond, who he continued to adore.

As the leaves began to fall, Grammy acknowledged that her grandson would not be visiting Brooklyn in the near future. “I’m arriving tomorrow,” she told him on the phone.

Henryk’s heart welled up with love for his grandmother, which he seemed to have forgotten in the recent feverish weeks. “Goody, goody, groovy Grammy’s coming soon”: he made up a little song as he danced around the loft flat.

Ann understood. “She’s coming here? You mean here?”

“Well …” he drooped. “Where else is she going to go?”

“But this is my home, only I can invite her to stay.”

“Yeah? Well, invite her.”

“How can I invite somebody I have never even met?”

Henryk stared at her and for a while they looked each other steadily in the eyes. Then Henryk started to pack. He called Jeff McPherson. The fellow knew at once who was on the line. His characteristic Irish brogue resonated in the receiver. “Hi, Henryk, long time no see. What’s new?”

“All sorts, Jeff. Jeff, would you put me up for a couple of nights?”

“Here’s the address.”

Jeff lived on the winding road up to Buda Castle, on the top floor of a four-story house, also a loft, or as the Americans liked to call it, a penthouse. Seems the Americans love these, thought Henryk as he hauled his gear up four flights, then another level, up the spiral staircase. No elevator.

He enjoyed the welcome drink by the kitchen bar and apologetically confessed that tomorrow they would be joined by Grammy. “Sorry!”

“No sweat! Perhaps she’ll make us paprika chicken.”

“If she manages to climb up.”

“Hey, we’ll bring her up ourselves!” Jeff’s good mood was a ray of sunshine that lit up the darkest corners of life. By midnight Henryk knew that the flat was Jeff’s own, as it was now possible for foreigners to buy property in Hungary. By two in the morning he had heard that Jeff bought and sold property, buying run-down houses, renovating them, and selling them on at a hefty profit. By four in the morning, that Jeff preferred men, but there was no problem, he only went for men like Doug, his partner, who was on a business trip to Romania. “He likes to travel, I don’t. We make a good pair.”

Black-and-white photos of Doug were everywhere. Doug in the Palatinus Lido. Doug in Venice. Doug at Lake Balaton. Doug in Ibiza. Generally in swimming trunks but at least half-naked. Henryk thought he looked like he imagined his farrier grandfather to be.

They drove out to meet Grammy in Jeff’s ivy-green sports car. At the last minute Jeff managed to conjure up a cellophane-wrapped bouquet for the old girl. “I can’t help it, flowers are my fatal weakness.”

Grammy was bowled over by Jeff. “A fine strapping fellow, your friend!” she whispered to him in Hungarian, so only he understood, from the rumble seat. Her sparse hair was tied in a girlish ponytail and fluttered in the slipstream.

“What does strapping mean?”

“Nice. Decent. Substantial. Don’t they say that any more?”

Henryk didn’t know.

Jeff made them dinner, Chinese. “Canard laque!” he declared with some ceremony as he whipped the ornate lid off what looked like a silver dish.

Grammy was spellbound. “And what do you do?” she asked Henryk. The conversation was in English.

“I’m in between jobs just now.”

“He’s joining us,” said Jeff with an encouraging smile. “We’re in property, that’s the going thing at the moment.”

Henryk’s grandmother left after three weeks, secure in the knowledge that her grandson had rounded the corner. Jeff showed them the country house whose renovation was next on the agenda. The old lady burst into tears. The building reminded her of her childhood in Szekszárd. Jeff offered to drive her down to Szekszárd, especially as he had never been to the area, but Grammy declined. “There is nothing left there of what’s in here,” she said, tapping one temple.

Jeff insisted throughout that Henryk was a business partner. As Grammy’s plane rose into the sky Henryk thanked him for this white lie. Jeff shook his head. “No lie, sonny Jim, we need new blood … If it works out, you can have a share in the company … You’ll be working for Doug.”

Henryk soon rose in status to partner with the right to vote in the limited liability company, whose name—originally JED (Jeff & Doug)—was for his benefit changed to HEJED, which came out almost as YOURPLACE in English. HEJED made successful property deals not only in Hungary but also in Transylvania and Slovakia. They were especially good at converting medium-size lodges and country houses. Doug, the Canadian giant, proved unequaled in resourcefulness in his dealings with builders and craftsmen, many of whom were scared of him. He bounded about the scaffolding like a mountain goat, in a white plastic helmet bearing the legend EASY.

Jeff negotiated with buyers and did the paperwork, while Henryk’s brief was the internal refurbishing. He bought period furniture on his trips around the villages, and had them restored either by experts or, sometimes, with his own hands. He had never derived as much pleasure from any job as came to him from this. He was particularly thrilled by fresh wood shavings and the smell of glue.

In the evening they would sit around at Jeff’s (Henryk had moved into a flat of his own a couple of streets away) and drank historic Hungarian wines as they browsed through books and albums of art history. Henryk acquired serious specialist knowledge of furniture, carpets, and especially lamp styles; in the Lamp Museum at Zsámbék he was the only regular visitor. The nouveaux riches treated the phone number of HEJED Ltd. as if it were the password to enter the circle of the top hundred thousand.

Henryk’s first car in Hungary was a ten-year-old ATV, a Cherokee Jeep, bought from one of Jeff’s drinking pals. He gave it a test drive to Pécs. In the county archives he was received much more cordially than he expected; they accept ed his solemn word that he wanted to carry out scholarly research and gave him a temporary reader’s ticket. In the place that seemed like a school hall, an elderly archivist attended to the researchers’ requests. Henryk confessed to him that he was searching for his ancestors.

“What is the name of the family?”

“Csillag.”

“Echt Pécs folk?”

Henryk did not understand the word echt, and nodded uncertainly.

“What was their line of business?”

“Unfortunately, I don’t know.”

A few weeks earlier he had visited the state registry in Budapest and on the basis of the date of birth they were able to supply him with a document about his father. Vilmos Csillag, b. Feb. 5, 1950. Father: Dr. Balázs Csillag (1921), Mother: Mrs. Balázs Csillag, née Mária Porubszky (1929). Both resident in Pécs.

It was this trail that had led him to Pécs. He showed the document to the archivist. He read it carefully and then suggested: “Choose one name, and on the basis of the year of birth, start looking at the year.”

“Which should I choose?”

“I would try Dr. Balázs Csillag.”

Nothing. Henryk thumbed through 1920 and 1922 as well, just in case … His hands turned black, but in vain. No sign of grandfather. Or grandmother.

“Are you sure they were born in Pécs?”

“No.”

“Because if they were, they must be here. Ah, just a minute, could it be …” and he leaned closer, almost whispering, “that they were Jews?”

“Yes. Could be.”

“You don’t know.” It sounded like a statement, not a question.

“They have all been dead for many years.”

“Fortunately, we hold a certified copy of the Jewish registers, from ’49 onwards.”

In the Jewish register Henryk at once found Dr. Balázs Csillag—he was born on New Year’s Day. Nice, he thought. Every New Year they could drink to the memory of grandfather as well. In the OTHER REMARKS column he found the following note: UB 238/1945. The above-named, on the basis of document number 67/1945 from the First Pécs Parish Office, has this day, August 25, 1945, converted from the Israelite religion to the Roman Catholic faith.

He read it over four times, word by word, before he managed to fully grasp its meaning. The old archivist leaned over from the far side of the narrow table, their heads almost meeting above the brick of a book. He lowered his wizened finger onto the rubric. “To be quite honest, I have never seen such a note in a register of births.”

“So this means my grandfather was a Jew at first, but then later he …” He did not complete the sentence.

“The family suffered a lot in the hard times, didn’t they?”

“That’s just it … I don’t know. I don’t know anything about it! Let me try Mária Porubszky.”

“Go ahead.”

No Mária Porubszky.

“It seems she was born elsewhere,” said the archivist.

“So that’s it, is it?”

Henryk’s American accent made the old archivist smile. This hurt Henryk and so he did not ask his questions, though to some of them he might have received a reply. The archivist suspected that the young man should head for the Jewish cemetery, for if a family is from Pécs, there is a chance of finding an uncle or two or a great-grandparent, and if he were to return with a year found engraved on the gravestone, he might have more luck in his search. But in America Henryk had been brought up to do things himself and he did not ask for advice. He managed to reach the Jewish cemetery anyway, though he had set off for the main cemetery. At the office there he was told that they could check the old registers for his Csillags only if he knew the exact dates of death.

“Take a look in the Jewish cemetery!” suggested one of the officials.

He had trouble finding it and twice drove past it in his Cherokee Jeep. The entrance was up a narrow side street: an iron gate painted black in the middle of a yellow brick fence with a handwritten sign in pencil: RING LONG AND HARD! He did so, but no one came. He returned some hours later to find the gate wide open.

Dr. Balázs Csillag, Mária Porubszky, he kept repeating the words to himself, like the first line of a prayer. Will they be here?

My grandfather was a Jew but he did not want to be. Because the Jews were persecuted here during the war. But the war ended on August 25, 1945. What is the point of becoming a Roman Catholic then, if he remained a Jew all the way through the dangerous times? I don’t understand.

Another question presents itself. Does this mean my father was a Jew? And that I am a Jew as well? At the Jewish Community office they said that it was the mother that counts. My mother was half Indian, half Hungarian. Jeff says Grammy is highly suspect, a Steiner, particularly a Rachel, is obviously Jewish. Grammy says no, she says a farrier could not be Jewish and was more likely to be a Swabian, that is to say, a German settled in Hungary. But then why would a German family have to flee from here? I don’t understand this either.

According to the archivist, just because someone was a Roman Catholic, he or she could easily have been a Jew. Confusing. He says those who converted were nonetheless hounded by the Arrow Cross (Nazis). So in the end what am I, with all these ancestors? Indian, Swabian, certainly Jewish, perhaps Jewish, converted Jewish, and of course America is in there too … A cocktail. A genuine, proper, thoroughly shaken cocktail.

How great it would be to know what happened when I was not yet born. How great it would be if once, just once, I could look into the past. How great it would be if I could fly back on the Back to the Future time machine! But it cannot be, everyday life is not like Hollywood.

But it’s truly a tale of adventure, this disappearance of my father without a trace. All that’s certain is that he flew back to the U.S., as they found his name on a Swissair passenger list. And that’s all. At the Federal Bureau of Investigation they said that he probably left for a new life in another state, perhaps in another country, Mexico, or somewhere in South America, presumably under another name, so he would be impossible to trace.

It’s a shame and thoroughly reprehensible that my father took the entire history of our family with him, into the void. He lost it. I’d like to find it. I’ve opened a new file, with the name “Father et cetera,” and I’m copying into it everything that I can find out about our family. I will print out several copies. At least what little we know should not be lost. So that if I ever have a child, I can hand it to him. Or her. He (or she) should not have to start from scratch.

Pécs cemetery seemed neglected, with most of the gravestones standing at drunken angles. Henryk was not sure if it was appropriate to enter in jeans, Teva sandals, and Ray-Bans, and he went in timidly. He tried to read the German (Yiddish) and Hungarian inscriptions, the Hebrew characters he could only caress. Isn’t there some office here, with someone to help? The building next to the entrance, several stories high, had all its doors closed. The steps at the back suggested a flat: a baby’s bath and a rocking horse indicated that there were small children here. What can it be like to grow up in a cemetery—a Jewish cemetery?

He set off at random down one of the rows. He knew that Dr. Balázs Csillag was born in 1921 and his wife Mária Porubszky in 1929. The question was: when did they die?

He paused at those graves where he could read the names.

Ignác Koller and his wife Hédy.

Béla Weiss. Robert Weiss. Alexander Weiss. Izabella Weiss. Vilma Weiss.

Albert Weiss and his wife Aranka Skorka.

Lipót Stern.

Mihály Stern.

József Stern.

Dr. Jenö Schweizer and Judit Wieser.

Imre Walser.

Máté Rotj.

Mojzes Roth and Eszter Holatschek.

Ernö Moohr.

Miksa Straub.

Ottó Rusitschka.

And … his head was reeling … the vault of the Csillag family!

Two structures the size of phone booths rose high above all the others, with a cupola recalling the Turkish dome of the church in the main square of Pécs. Unbelievable! … These are my ancestors! he thought. He began to perspire.

Here lay Dr. Antal Csillag, who died in 1933, Dr. Bencze Csillag, died 1904, Dr. Ervin Csillag, died 1877.

Heavens! Here they are! His knees shook. It was plain that Dr. Antal Csillag was the father of Dr. Balázs Csillag, Antal’s father was Dr. Bencze Csillag, and the latter’s father was Dr. Ervin Csillag. Fantastic! He scribbled down the names. Doctors? Or lawyers, like grandfather? And where are the wives? Perhaps all will be revealed in the archives.

Only as he was leaving did he notice a grassy area, the size of a small garden in the corner by the entrance, where a row of gray gravestones of uniform size and shape stood, leaning against the fence. They seemed very old: the wind, the rain, the snow had all but worn them smooth. By the side there was a metal plate, like a road sign: BEREMEND. He had no idea what that could mean. I’ll ask someone. He wrote it down, otherwise he’d forget. He stood a long time on the parched grass. The afternoon began to smell ever more sweet. The buzzing of the wild bees tickled his eardrums.

“You staying?”

An old woman, brightly dressed, was standing behind him, a faded muslin kerchief tied about her head, a worn pair of clogs on her feet. Henryk did not understand.

“Excuse me?”

“Because I would like to lock up.”

“Oh, right …” and he moved to go.

“No rush, mind!” said the old woman barring his way. “Stay as long as you like.”

“Please could you tell me what is Beremend?”

“Beremend?” The old woman blinked fiercely as if caught out doing something naughty.

Henryk pointed to the metal sign.

“Ah, Beremend! That’s a village, not far from Pécs, further down.”

“What’s the sign doing here?”

“Dunno really. I was doing them a favor … They left the key with me while they all went off to a wedding in Baja.”

“Well, thank you,” said Henryk and went out into the street.

The old woman followed him and immediately locked the iron gate from outside. “Farewell.”

He hurried back to the archives but there was no trace in the parish registers of Dr. Antal Csillag, or of Dr. Bencze Csillag, or of Dr. Ervin Csillag.

“Doesn’t prove anything,” said the archivist. “There are always documents gone astray. If I were you, I’d believe the gravestones.”

From Pécs Henryk drove to a little village in County Somogy, where Jeff and Doug were waiting for him in a camper van, with a celebratory meal. They ate in the open air. Henryk gave a detailed account of how far he had got.

The HEJED Co. had bought two run-down properties in County Somogy. Jeff had already secured firm buyers for them. In Somogyvámos it seemed virtually impossible to imagine that in place of the ruins heavily used by the cooperative there could arise a country house similar to that of the original owners, the Windisch family, in the eighteenth century. This family of Austrian nobles had put down roots in several areas of Hungary; in Somogyvámos there lived one of the more impoverished branches. What remained of their shrinking lands had been taken over in 1950 by the Red Star Agricultural Cooperative: the grander rooms were used as offices, while the outhouses became grain stores. Since the dissolution of the cooperative it had stood derelict, the weeds waist-high in almost every room.

Henryk had not lost any of the impetus he had gained in Pécs and early in the evening he walked to the village cemetery. He passed under the rusting curlicues of the sign RESURREXIT! and began to examine the crosses and the gravestones. The better-off families had had monuments raised to them here that he thought were large enough to live in. Mechanically, his ran his eyes over the names. The most monumental crypt, almost a mausoleum, housed the dead of the Counts Windisch and the family Illés.

As the sun disappeared behind the hills, the air turned gradually colder. Henryk had the curious notion that he would lie down on one of the bed-shaped crypts to see if he could sense the presence of the dead at rest beneath him, or the presence of death itself. Newly planted trees lined the path, their branches arching over him. As the evening breeze brushed through the trees their leaves touched and sighed. Woolly clouds flitted across the sky. Henryk closed his eyes and not for the first time felt how the majesty and beauty of nature could actually hurt. He imagined what it might be like when you could not experience even this. If you cease to exist in this world. What becomes of you? Where do you go? If anywhere …

“Bíró?” queried a woman’s voice, obviously pleased.

Henryk opened his eyes. A blonde though graying woman with a broad face was staring down at him, a metal watering-can in her hand. She smiled as if he were an old acquaintance.

“Excuse me, but …” Henryk sat up.

“Bíró?” the woman repeated, with a beatific smile. “Jóska Bíró!”

Henryk cleared his throat. He noticed, now, that the grave on which he lay was the resting place of Mihály Bíró and his wife, mourned eternally by their adoring sons and daughters. He stood up and shamefacedly dusted himself down.

“Oh, it’s such a long time since we’ve seen you in these parts!” the woman said, shaking him vigorously by the hand.

“Actually …”

“Yes, I know how busy it must be in Pécel too.”

“In Pécel?”

“Or have you moved on?”

Henryk found it more and more difficult to own up. But he was spared this, as the woman unexpectedly gave a shriek:

“Oh no, what am I saying? You’re not Jóska Bíró at all, you’re the other one, his friend, who stayed just for the summer, … little Vilmos … Vilmos Csillag! What brings you to these parts?”

“You knew my dad? Vilmos Csillag was my dad …”

“Heaven preserve us!” The woman clapped her hand to her face, which bore many signs of having worked in the fields. “Of course … How could I have … it’s been so long! But it feels like it was yesterday.”

Art is rarely able to surpass life. It was sheer chance that I lay down on a grave in Somogyvár Cemetery that turned out to be the final resting place of Mihály Bíró. Who would believe that just then there appears old Mrs. Palóznaki, maiden name Ági Mandell, who was a childhood friend of Mihály Bíró’s son. It was with these Bírós that Papa stayed in the Fifties, because they offered country holidays to city children for payment, taking in as many as three or four at a time. Ági Mandell said Papa was the only one to come back year after year.

Absolutely incredible!

I asked her to describe what sort of a child Papa was. She said delicate. He was reclusive, not as loud-mouthed as the village kids. She also recalls that the color of his eyes changed all the time, depending on his mood: sometimes it was gray, at others green, or even light brown. I thought I could detect that Ági Mandell had a soft spot for Papa, but she denied it—she had fallen for Jóska Bíró (“head over heels,” as she put it).

I discovered that the Arrow Cross had taken Mihály Bíró because he was Jewish; he returned from one of the German Lagers and became a corn exchanger. Since their village did not have a mill of its own, the peasants would take the corn to Mihály Bíró, who would exchange it for flour using a complicated formula that factored in weight and quality; he would then take the corn to the nearest mill himself. That was how he made his living. Until serious illness (cancer) forced him to give up. After his death the children sold his house, which became the agricultural cooperative’s nursery. Now it stands empty. Jóska Bíró became a stonemason and to the best of Ági Mandell’s knowledge he moved to Pécel.

My grandfather was supposedly in the Ministry of the Interior as a “backroom boy” (Ági Mandell’s phrase). The minister was László Rajk, who was hanged. What happened to my grandfather she does not know. I wrote down her address and the phone number of the bakery where she works in the office, and I gave her my details too.

Henryk spent several weeks in the village, during which Ági Mandell invited him over for dinner more than once. Her roast pork was so succulent that Henryk had thirds, not just seconds. He was under the weather for days afterwards, but still considered that he had never in his life eaten anything so delicious.

The Somogyvámos estate had been sold to a distant kinsman of the Windisches, a Viennese business lady called Frau Rosa Windisch. She was approaching forty, but the turkey-like wattle under her chin made her seem much older. This not especially attractive part of her body she assiduously tried to conceal with chains of silver and gold and rows of pearls, which therefore constantly drew attention to it. Frau Rose Windisch spoke English with a dog-like bark and was never happy with anything. She strode up and down the half-ready building with eyebrows arched and head continually shaking: “I can’t believe this!” Her intonation was a tribute to the meticulousness of the Berlitz method.

“What is it now that she can’t believe?” Jeff asked Henryk, quietly.

“She’ll let you know, don’t worry.”

Frau Rosa Windisch wanted to establish a stud-farm here, with a Gasthof for Austrian and German visitors, the main attraction to be daily horse-riding. She thought that the quality represented by the HEJED Co. did not come up to Western standards. But it soon turned out that hers did not either: her taste was that of the petty bourgeois Austrian, and she would have much preferred brand-new garden gnomes to the nineteenth-century reliefs that Jeff and his team were restoring with such care.

The three of them could hardly wait to be rid of the testy lady, and could not be bothered to take her on for retaining 10 percent of the contractually agreed price on the grounds of alleged shortcomings in quality.

“Good riddance!” said Jeff.

They left the estate in Henryk’s Jeep. Stopping at the sign that marked the end of the village, they took great satisfaction jointly and severally in urinating on it.

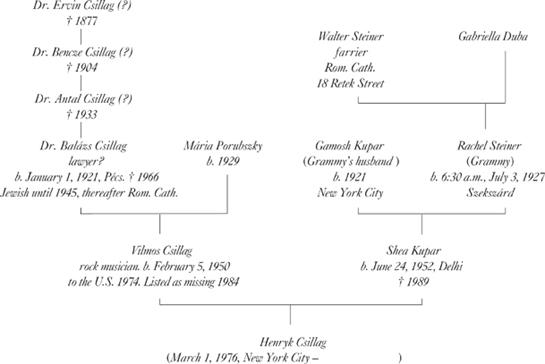

Jeff and Doug took two weeks off and went on vacation to Malta. Henryk went into the office quite often—it now consisted of three interconnected rooms on the Bem Quay, by the Danube—and chatted with the office girls and the bookkeeper. Having no work, he realized how lonely he was. He tinkered with the “Papa et cetera” file. He gathered what information he had into a family tree on the computer, printed it out on the all-in-one used for photocopying the blueprints of the HEJED Co., and pinned it up on the wall of his flat.

I’ll add to it, as and when I have something to add, he thought.

He often thought of Ann and even more often of Bond, James Bond. These were two rare examples of names that he remembered even in his dreams, perhaps because they often featured in them. He had to remind himself how lukewarm his feelings for Ann had become by the end. But Bond, James Bond, he loved unreservedly (the last person he embraced with the keenness he felt for this sheep-sized dog had been his mother). Bond, James Bond, generously tolerated this and would sometimes lick Henryk’s face, his tongue rough, warm, and wet.

Maybe I should get myself a dog … a big one.

In the absence of his two friends, however, he decided that what he needed was a two-legged friend. Though he was quite certain he was not interested in men, in his heart of hearts he was not quite so certain that he was interested in women. However intimate he came to be with Ann, they had never come close to that melting into one another he had read about in novels. He hadn’t ever, so far, felt anything like that. Which was to say that he had never been in love. That, or the novelists were pulling a fast one.

His evenings would generally begin in restaurants and end in nightclubs, mostly in the ZanziBar, frequented by a lot of English-speakers, chiefly Brits, on account of the wide selection of beers on offer. Henryk never got drunk, but a couple of pints of Guinness loosened his limbs sufficiently for the stroll to his house, which was nearby. Dog-walkers often walked past, and Henryk would eye up the dogs no less than the women. The dogs would generally amble over to him, pressing and sniffing, their tails windscreen-wiping furiously, while he was always happy to hunker down and stroke their backs. He would inquire after the dog’s name, age, breed, if the owner or walker was not in a hurry. His sieve-like memory instantly lost this information, so he would put the same questions to the same owner the next time they met. The bigger the dog, the more Henryk liked it. Not far away there lived a Great Dane that always made him melt inside. And he greeted the four black Labradors with the same joy every time; he already knew they were mother and three pups, the latter seven-month-old males who had already caught up with their mother in size.

“What are they called?”

“They’re still called Milady, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis,” said the brunette holding the four leads not in her hand but wound around her neck.

“Sorry, but those are strange names.”

“Haven’t you read The Three Musketeers?”

“I’m American, we don’t read books, we just watch TV all the time,” said Henryk. He meant it as a joke. His pronunciation of the Magyar consonants brought a smile to the girl’s lips. Henryk brought out his notebook with his list of recently learned Hungarian words, and started to write the names down: “Milady, Athos, Porthos … what was the fourth one?”

“Aramis.” The girl had faint freckles on her cheeks.

Henryk swallowed hard. “May I walk you home?”

“Easily done. I live right here. Ciao!” The girl herded the black Labradors through the gate. Henryk could not take his eyes off the muscular legs, hidden by her skirt to mid-calf.

The following evening he hung about that part of the road, in the hope of bumping into the girl and the dogs again, but in vain. The third day he decided he would wait around by the gate until they turned up. Ten minutes later the girl and the dogs came down. “Waiting for us?”

“How did you know?”

“Saw you from the window.”

Henryk introduced himself. The girl’s name was Mária Zenthe. Her hand shook Henryk’s firmly. He asked if they could meet on purpose, as it were. Mária gave him a long look. “Difficult.”

“Because of someone?”

“Yes.” She pointed to the dogs. “Because of them.” She explained that they could not be left alone for any length of time, as the pups would certainly trash the flat.

They were quickly on first-name terms. Henryk suggested a weekend trip north to the Danube Bend. Mária was hesitant: this number of dogs is too many for a car. Henryk insisted that there was plenty of room in the Cherokee Jeep.

They set out for Szentendre, towards the Danube Bend. The girl spread some old towels on the back seat and gave the dogs the signal “in you go!” and they obediently hopped in. Henryk could see in the rear-view mirror that they were looking around with faintly bored expressions, like Madison Avenue ladies in their limos.

Mária joked that she was a rag-and-bone woman. The bone referred to the dogs, but the rag was genuine: she designed, sewed, and wove carpets, curtains, wall-hangings, and cushions. She had recently graduated in applied arts. She was a native of Hódmezövásárhely and had come up to Budapest to take her degree. She had had a serious relationship and was now poring over its ruins. Milady had originally belonged to her ex, József, but she was so fond of Mária that after the split they agreed Milady would be hers. József was a sculptor in metal. They lived in his workshop-cum-flat. Mária could stay until she found a flat of her own and make a living, that was the agreement. József had meanwhile moved back to his mother’s. Hardly had he removed himself from her life than Milady became pregnant and gave birth to eight pups from a father unknown, which Mária had seen only from a distance, a German Shepherd possibly, or a cross of some sort. When József heard of the mésalliance he seemed to turn on Milady. Since then he had taken no interest in her at all. The newborn pups had looked like little black rats; five she managed to give away, three remained with her. “I don’t mind. I’ve grown very fond of them.”

“I can see why,” he said, the hot breath of the four dogs on his neck.

It was as they were passing the new estate at Békásmegyer that there was the first sign of problems. Aramis started quietly to retch, his head and neck in spasm.

“Whoa!” said Mária. “Better stop, he’s going to throw up.”

Henryk, however, could not move over in time, and Aramis emptied the contents of his stomach on the seat and the car floor, with plenty left for Henryk’s back. Mária was all profuse apology as she tried to limit the damage with Kleenex. As soon as they set off again, it was the turn of Porthos to vomit. And so it went on. The dogs threw up steadily, one after the other, and the inside of the Cherokee Jeep was pervaded by the acrid smell of the acid from the dogs’ stomachs. Mária tried desperately to calm the dogs down, pleading with them and shouting at them by turns, but they just stared at her balefully, as if all their sad, dark pupils reflected the same thought: Sorry, but we have no choice but to submit to the call of nature.

Mária would gladly have turned back but Henryk said it was a shame to let this spoil their day. “Anyway, I don’t think there can be anything left to bring up now.”

In Szentendre and then in Visegrád they made quite a stir with the four black dogs. Henryk behaved as if he were the owner. They got back about ten in the evening, the dogs asleep on the back seat.

“Thanks for everything,” said Mária. “Wait a moment. I’ll just take the herd up and then I’ll come down to help clean up the car.”

“Come, come … I’ll see to it tomorrow. But do come back … for at least an hour or so.”

The four dogs stayed locked in the workshop until three in the morning and chewed up everything that they could sink their teeth into. Henryk saw Mária up to the flat. She surveyed the battlefield but did not despair. “Well, it’s time for a spring-cleaning anyway.”

Henryk stayed. When Jeff and Doug came back, he introduced Mária as his fiancée.

“Indeed?” Mária seemed dubious.

“I don’t get it,” said Jeff, thought Doug. Henryk repeated: “My fiancée.”

“Are you sure about this?” asked Mária again.

“Congratulations!” said Doug, nodded Jeff.

Mária later pointed out that he might have discussed the matter with her first.

“Well … I’m sorry. So what do you think?”

“Not so fast. First we have to get to know each other better.”

“But I’ve got to know you already!”

Mária shook her head. “There are many things about me that you don’t know. Important things.”

“So tell me.”

“I can’t do it just like that. In due course. All in good time.”

Henryk had to resign himself to a wait.

Dear Grammy,

I’m still doing fine. The firm HEJED Co. continues to expand, but this time I want to write about something else. I think that perhaps this is my HEJEM, my place, forever.

I have met someone, a girl, and if it were up to me we would get married tomorrow. I’d be delighted if you could meet her. Could you not come over again? Let me send you a ticket!

His grandmother telephoned at once. “I will come, but let’s wait with this a little. Don’t rush things. First you should really get to know each other well.”

“That’s what she said, too.”

“Clever girl.”

These were busy times for Mária. She was making wall-hangings, an insurance company having ordered four large ones. She sat at her loom from the crack of dawn and stopped only to take the dogs out the regulation three times a day. If Henryk wanted to see her, it was during these walks that he could do so. They went on the wider pavement of the upper quayside, following the frisky little herd and apologizing to the more easily frightened pedestrians.

“Tell me, do you believe in reincarnation?” asked Mária.

Henryk was at a loss. He had never asked himself this question and so had no answer. When he was small he had attended church, and his grandmother would certainly have liked him to become a proper white Anglo-Saxon Protestant, but as no one around him took God seriously, he too thought religion was just empty ceremonial which he gave up as soon as he could, just as he did the scouts.

Reincarnation was the cornerstone of Mária’s view of the world. Death is also, simultaneously, birth or rebirth. After the decay of the body, the soul lingers on for about a century and a half, following various paths by way of purification; only after this can it begin its next life. Someone who was born a man in a previous life generally becomes a woman, and vice versa.

For Henryk the prospect that after his death his soul could have a second helping in another being was new, exciting and tempting; nevertheless, he found it difficult to believe.

“You don’t have to believe it,” said Mária. “When the time comes you will find it as natural as the fact that the sky is blue.”

Henryk was not convinced that this would happen, much as he might long for it. In the course of further conversations he discovered that Mária shared the views of a German philosopher called Rudolf Steiner, who was well known at the beginning of the twentieth century. “He was a spiritual visionary. There are people possessed of the ability to see on a higher plane, that is to say, they can see things that others can’t. They say you can be born with this ability, but it can also be achieved by self-education. In our time, the path of self-education is more common. Man today has lost his ability to see within. We possess what are called spiritual senses, but these cannot operate of themselves and have to be developed by the individual. I have many books on this; if you’re interested, I can lend them to you.”

The vast majority of the books were, however, in German. Henryk knew no foreign languages; he had English as his mother tongue and Hungarian as his father tongue.

Spiritual vision and self-education: so many unknown spheres. Just as hard to believe as reincarnation and at the same time just as attractive.

It turned out that Mária spoke English, German, and French very well, and even some Danish. A lover of opera, she could also manage some Italian.

It’s true, thought Henryk, I really don’t know her well.

“Why did you never go to college?” asked Mária.

“I came here instead. This is my university.”

“Aha. So you didn’t have the courage to take on a degree.”

“That’s not what I said.”

“But it’s true anyway, isn’t it?”

Henryk thought about it a while and then admitted it was. “How did you know?”

“It’s typical of Pisces.”

“Pie seas?”

“The astrological sign. You are Pisces, aren’t you?”

Henryk had no idea. Mária asked when he was born and when she heard the date, nodded: “Yes, that’s Pisces.”

Mária was well versed in the art of casting a horoscope, something she had learned from her grandmother. She cast one for everyone she came into contact with and who gave their permission.

“You ask for permission?”

“Of course. It’s a very intimate matter. Things can be revealed that the natives … the person concerned won’t perhaps be happy about. Or they won’t be happy that I’m the one to have revealed them. So … can I cast yours?”

“Yes.”

“Do you know the exact time of your birth? Hours and minutes. I need it for the ascendant.”

“I’ve no idea.”

He called his grandmother to ask, but Grammy did not know. “In those days we were not on smiling terms.”

“Smiling terms?”

“Yes. You know, we were not very pleased that she had married your father … In fact, not in the least pleased.”

“And why have you never mentioned this before?”

“Did you ask about it?”

“How can I ask about something that I have no idea about?”

There was silence at the other end of the line, then a quiet sniff or two.

Henryk changed the subject. “You haven’t asked about Mária …”

“How can I ask about somebody I know nothing about?”

They both put down the receiver offended.

Mária said that she could calculate the ascendant only on the basis of the exact place, day, hour, and minute of the birth, though she had heard of astrologers who were somehow able to calculate it from the subject’s most important life events. She wrote to such an astrologer in Szeged, giving her the dates of the death of Henryk’s mother, the disappearance of his father, his arrival in Hungary, and the date the two of them had first met. She was not satisfied with the answer (which had cost an astronomical ten thousand forints). “She says your ascendant is Aries. But I see nothing of Aries in you. Aries are fiery, liable to set their home ablaze, repeatedly dashing their heads against brick walls. Of course, you may be Aries nonetheless, but the planets in the twelve houses are so arranged that your ascendant is less typical of you than your Sun, that is, Pisces.”

“Well, now, is that good or bad?”

“I can’t put it like that. How interested are you in this?”

“Very.”

Mária nodded and launched into a detailed explanation. She did not tell fortunes from the stars, she only drew conclusions about the subject’s personality. That is, certain basic traits, with which the subjects can do what they wish and are able to. In her view one’s horoscope influences the nature of one’s fate no more than some 25 percent; the rest is down to genes, family background, upbringing, and self-development. Be that as it may, those born under the sign of Pisces have some difficulty in negotiating the boundary between themselves and the world. They are often lonely. Being the twelfth sign, the most complex, it yields the most sophisticated personalities. Pisces generally evince some sensitivity to art, perhaps even some artistic ability; there are, for example, many musicians among them. “They put on the pounds easily … though you show no sign of that yet. Have you heard of Enrico Caruso?”

“No.”

“He was a world-famous opera singer. Some say the greatest tenor of all time. He is a Pisces. I mean his Sun is. Then there is Elizabeth Taylor. Or Zorán. Have you heard of him?”

“No.”

“He’s a Hungarian rock singer. Then there is, let me see, Sharon Stone. You must know who she is.”

“How come you know so many people’s sign?”

“I’ve looked them up in Who’s Who. These days I can sometimes tell just from the face. Especially Scorpios, Virgos, and Geminis.”

Henryk took extensive notes from Dane Rudhyar’s The Astrology of Personality, which he found on Mária’s bookshelves. He still found it easier to read English than Hungarian. Astrology was again something that he reveled in, which made his spine tingle, though his doubts were never allayed. How can one claim that a person’s character could, even in part, depend on where and when he was born? Well … surely you can’t. At the same time it was beyond doubt that the Moon is implicated in the movement of the tides and the menstrual cycle, yet it is one of the smallest planet-like objects of all. Can one then say for certain that the heavenly bodies do not have any influence over us? Well … surely you can’t.

He tried hard to memorize the order of the signs of the zodiac, to master them like a poem: Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer … Here he always got stuck and had to sneak a look at his notes to continue: Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio … Again he needed help: Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces. He could not understand why he was unable to hammer into his brain these twelve words, let alone the dates of each. He envied Mária and her memory of cast iron: whatever that girl once set eyes on, or heard, or experienced, it was forever seared on her brain. Before the sculptor József, Mária had been in love with a Danish boy and had learned Danish for his sake—in effect in two months (the list of rarer verb forms was still pinned to the toilet door). Henryk failed to make any inroads even on the Magyar vocabulary he targeted.

“If you are so troubled by your poor memory, why don’t you develop it?” asked Mária. “You can improve every aspect of yourself, it’s just a question of willpower.”

On her instructions, Henryk started by memorizing lists of numbers, and then progressed to names. He began to feel he was making some headway.

Mária did not move in with him, nor did she let him share the workshop-cum-flat with her. “It would be a bad omen.”

“Amen?”

“Omen. Sign, premonition. I think it’s Greek. Or Latin.”

“But surely we know each other now!”

“Not well enough. I still don’t know what the most import ant thing in life is for you.”

“You.”

“Don’t be silly! I’m serious.”

“Only you could ask a question like that. And right away you make me feel like some stupid toddler.”

“A toddler would be able to answer on his or her level. Think about it.”

Eventually what I came up with was that you should be happy. Whereupon she says: who is the “you”? I replied: “Me.” Whereupon she: “A selfish view, but OK. So what is needed to make you happy?”

This again was a typical Mária question. I gave her the list: “Money, then good health, a secure family background, I guess that’s about it. Now what about you?”

She looked grave. Because we don’t agree on anything. The things I mentioned are, in her view, cliché ideals of petty bourgeois life. Health is like the air: it doesn’t make you happy as long as you can breathe it, in fact you barely notice it. She would not put a secure family background here either, because in the end you must count on yourself.

In her view it’s not these sorts of thing that you need for happiness, but abstract things, for example: firm and consistently followed moral principles, then knowledge, willpower, endurance. And good fortune. She was sorry that I hadn’t learned even that much yet. She could hardly marry me.

When she said this to my face, I ran home and wept. I knew she was right, in a way. But I also knew I wanted her as much as I ever wanted anything or anyone. I turned on my heels and went back. I bounded up to the fifth floor to knock on the workshop door. I knew what I wanted to say to her.

“If I have not learned enough, teach me; if I am not perfect, love me!” Henryk practiced the words as the black iron door opened.

Mária let him in.

“Now do you know me well enough to …?” Henryk asked at breakfast.

“Maybe. But you don’t know me well enough yet. You idealize me, although I have many bad qualities.”

“For instance?”

“Excessive self-assurance. The firm conviction that I must continually educate everyone. A degree of pedantry. Poor time management. But I am an Aquarius, not very practical, as you know.”

Henryk loved Mária’s faults, too, even if these sometimes annoyed him. He had occasion to discover that Mária’s bad qualities were just the same as her good ones. The self-assurance was handy when it came to dealing with officials and businesses. Her enthusiasm for teaching people was what made it possible for Henryk to learn from her. Pedantry and knowledge were fruits of the same tree. With the lack of practicality came the purity of her soul.

Following this train of thought he came to realize that probably everyone’s faults are the same as their virtues. He tried to look at himself in this light. He was relatively slow (i.e., thorough and determined). His self-confidence was low (i.e., modest and careful). He was not well educated (i.e., had a thirst for knowledge). His memory was rubbish (i.e., quick to forgive).

He felt his relationship to Mária was growing ever closer, despite the fact that she continued to keep him very much at arm’s length. Most worryingly, Mária insisted on spending two nights out of four, on average, in her workshop-flat, and on those nights Henryk had to sadly tramp home alone. At the mere mention of the word marriage her eyes flashed fire: “No. Not yet.”

Once, in bed, Henryk asked her: “If you became pregnant, would you marry me?”

“It would guarantee that I wouldn’t.”

“Oh, my … Now that I really don’t get!”

“But it’s simple. If we have a child and are married, in case of divorce we would fight over the child. If we are not married, it can’t happen. You could not do anything to me.”

“But why would I want to do anything to you?”

“In your case, that’s really hairy. You might one day decide to go back to America, you’d take the child with you …”

“Oh, Mária, what a weird view you have of things!”

“A realistic view. It may be hard to imagine now, but all my girlfriends are divorced and I have seen how it reduces people to the level of animals.”

“But look at the many pluses of marriage: the security, the sharing of everything we have; even in the case of divorce, under Hungarian law half of everything is yours!”

“I told you I am not materialistic.”

Henryk thought his head would burst, like an over-inflated football. What a setup! Every girl longs to get married, the only exception being the girl whom fate had brought him together with. He guessed it would be pointless to argue; he would just bounce off Mária’s iron will. There was nothing for it but to accept her as she was.

The ease with which Mária gave birth to my son almost suggested she had been practicing. Konrád Csillag came into the world on April 14, 1996, weighing two and a half kilos and measuring forty-eight centimeters in length. In the MÁV (Railwaymen’s) Hospital the consultant thought it would be advisable to place him in an incubator. But Mária refused her consent, saying it was unnecessary. She was right. Little Konrád flourished and ten days later we were allowed to take him home. By then Grammy had safely arrived and joyfully embraced her great-grandson, admitting that she had not thought she would live to see this day.

We notified Mária’s parents, too, but they did not come. They are as angry with Mária for not getting married as I am. Although I am no longer angry. I have accepted that nothing involving her is straightforward. Only her grandmother Erzsi came up from Hódmezövásárhely. Grammy was still with us. I thought they would get on well, but they avoided each other in some hostility. Erzsi was constantly checking my son’s horoscope (Aries, with Taurus in the ascendant); she perhaps devoted more time to this than to little Konrád.

By then they were living in Üröm, in a detached house that was three-quarters ready. Mária’s studio was to be in the loft, Henryk’s office in the basement, but these were still at the blueprint stage. The regulars of HEJED Co. were supposed to finish the work in the house, but the firm was so inundated with work that work on their home was continually put back. In the ground-floor lounge Henryk built a fireplace of undressed stone, a carbon copy of the one in Mária’s flat. He thought he would not be able to get hold of a genuine bellows, poker, and fire tongs in Hungary, but was amazed to spot a set at Budapest’s Ecseri flea-market. Some enterprising Hungarian was (re)producing them by the dozen.

The colder half of the year was nearly over, but Henryk was glad to light a fire in the evenings. It pleased him to show Mária how well the flue was working. He could watch for hours as the flames encroached upon the logs of crackling wood. A joyful end, to turn into light and warmth, he reflected.

The dogs took possession of the garden, digging out and chewing up the flora. Mária was not bothered too much. “We’ll sort out the garden when we have time.”

But they didn’t have time for quite a while, as the newcomer took up their every moment. For the moment, Henryk neglected HEJED Co., but Jeff and Doug took it in their stride. They preferred to throw a few one-liners at him: “When we have a child, neither of us will come in to work for a bit!”

Mária wanted Konrád baptized. Henryk did not understand. “But you are constantly on at the church!”

“Doesn’t mean he should be denied holy water.”

“What’s the point?”

“What’s the point of brushing your teeth?”

Again, Henryk gave up on this debate. But he insisted that either Jeff or Doug should be his godfather. Mária raised no objection. “But which of them?”

“Let them decide.”

“Both of us!” Jeff decided.

So my son had two godfathers in the persons of my dear friends and business partners. As for a godmother, we asked Mária’s childhood friend Olga to do the honors.