Does the Government Help or Hurt?

Overproduction and marketing drive excessive consumption: The food is available; we’re bombarded with “information” about why we should be craving it, or why we’ll be healthier or sexier or smarter or richer if we eat it, and we respond by purchasing and eating more.

But why processed food? Why not whole food, real food, basic food? Why not corn instead of corn chips? Yogurt instead of yogurt bars? Chicken instead of McNuggets? Water instead of Coke or Gatorade?

It’s easy enough to scorn Big Food or specific individuals who—compelled by greed or simply opportunity—have exploited land, air, water, animals, and humans in order to make their fortune.

But societies evolved to provide mutual protection. And in theory at least, a democratic government exists to protect the citizens who elect it—not just from external threats but from internal ones. This makes looking at our government’s role in food policy especially painful. Much of the blame goes to the Department of Agriculture (USDA), which is responsible for administering the farm bill, the common name for a well-established group of laws that set agricultural policy. (The most recent version is “The Food Conservation and Energy Act of 2008.”) This sweeping legislation largely determines what food is grown and also—in theory—provides us with nutritional guidance.

The USDA has consistently favored individual and corporate profits over public health.

There’s a serious conflict of interest there, and it costs the public plenty. For something like 70 years the USDA has consistently favored corporate profits over public health, producers over consumers, and—in effect—lies over truth. Public food policy has not been all bad, but by and large the USDA has not done right by the majority of the citizens.

It’s no exaggeration to say that public health has been sacrificed at the altar of profits, and that current food policy, although not quite the worst it’s ever been, is sorely lacking. (The current farm bill, just passed by Congress as of this writing, is not much better than its predecessors. Perhaps by the next go-round—in 2012 or 2017, depending on what’s determined now—we’ll have another shot, and by then public opinion may be strong enough to bring about real changes.)

A very short history of American nutrition advice

Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, when the British government mandated that seamen be given lime juice (hence the nickname “limeys”) to prevent scurvy, there have been attempts by government to set dietary guidelines. The USDA published its first recommendations in 1894; the author, W. O. Atwater, advised moderation: “The evils of overeating may not be felt at once, but sooner or later they are sure to appear—perhaps in an excessive amount of fatty tissue, perhaps in general debility, perhaps in actual disease.”

Smart guy; things went backward from there. By 1916, the USDA had divided foods into five groups: milk and meat, cereal, fruit and vegetables, fats and fatty foods, and sugars and sugary foods. In the 1930s, the USDA was studying the nutritional requirements of Americans, and came out with the precursor of today’s recommended dietary allowances (RDAs). The USDA added 50 percent to what it believed was the average requirement for “normal adult maintenance,” and thus set the stage for recommending what became a national habit: overeating. By the mid-1950s, we were presented with the classic “basic four” food groups: milk, meat, fruit and vegetables, and grains.

We take this grouping for granted now, but in fact it was arbitrary. (Why, for example, are dairy and meat different, but not meat and fish and not fruit and vegetables?) By giving equal weight to these four groups, the USDA was assuring all farmers that their interests would be promoted; and by making distinct categories for milk and meat, the agency made certain not only that the two biggest lobbies would be satisfied but that Americans would “understand” the “importance” of consuming plenty of each. Evidently no one important was making money from fishing.

The USDA declined to address the single most destructive element in the American diet: sugar.

And by ignoring sugar (did you notice?) the USDA declined to address what has become the single most destructive element in the American diet. By lumping together fruits and vegetables, by making no distinctions among carbohydrates (whole grains, cookies, and white bread were all the same as far as the USDA was concerned), it downplayed the critical differences among these kinds of carbohydrates, and ignored the distinctions among carbohydrates, meat, and dairy products.

Less than 20 years later, the government blew it again. In the 1970s, the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs convened to eliminate malnutrition and declared that there was also a need to confront excess in the American diet. That mission was met and aggressively opposed, as you might guess, by the agricultural and food industries, whose interest lay not in confronting excess but rather in promoting it.

The kind of fat we eat is far more important than the overall amount.

So in 1977, when the committee released “Dietary Goals for the United States,” the battle lines were clear. The committee found—or seemed to have found—that eating too much of certain foods, specifically meat, was linked to chronic illness. It intended to report this, and to recommend an overall reduction in meat eating.

No sooner had the recommendations been written than the lobbyists came out in force, and before the recommendations could even be made public they were revised. So what the committee reported, in what appeared to be a compromise but has since proved to be a victory for Big Food and a defeat for public health, was that Americans should avoid fat in general and saturated fat in particular. Thus the committee created the now familiar mantra: Keep total fat to less than 30 percent of caloric intake; concentrate on polyunsaturated fat; decrease cholesterol intake, and so on.

Thirty years later, it seems safer to say this:

- We need fat to live, and the kind of fat we eat is far more important than the overall amount.

- It’s not entirely clear that either saturated fat or cholesterol on its own is harmful.

- When polyunsaturated fat is hydrogenated, as it is in margarine and shortening, it’s dangerous to our health.

- Monounsaturated fats, like those in olive oil, are accepted as the best ones to consume for heart health.

- The only foods whose value seems unquestioned, and which can do you no harm (unless they’re bathed in pesticides, of course), are what we think of as plants—vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, and grains.

Nutrition advice meets food policy

At the same time as the Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs was working on its report, changes in government farm policy encouraged boosting meat production as well as that of the grains that were increasingly used to feed livestock. Grain could be much more easily raised for profit than grass, even though cattle are natural grazers (“graze” and “grass” have the same root) and their stomachs cannot easily digest grain.

Back in the 1930s, the Roosevelt administration established a program to help people who made their living off the land cope with the falling prices that resulted from overproduction. The Commodity Credit Corporation, as it was called, set a target price based on the cost of production for corn and other storable commodities. When the market fell below the target price, farmers could take out a loan for the value of the crop, using the crop as collateral. They would then store the corn until the market rebounded, and use the proceeds to repay the loan. If the market didn’t improve, the government bought the grain and sold it when prices recovered.

Changes in government farm policy have encouraged increased meat production for at least 35 YEARS.

In theory, the program had several benefits. It regulated production to prevent surpluses, and it created a national grain reserve that could stabilize prices during droughts or other disasters. It also kept farmers from abandoning their land as had happened widely during the early 1930s, when a couple of bumper years that lowered prices were followed by a series of droughts in which crops could barely be grown.

Fast-forward to 1973, when President Nixon made a deal to sell grain to the Soviet Union just when a bad growing season was about to produce domestic shortages. The result was prices so high that many consumers boycotted meat. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz, in an attempt to drive prices down again, encouraged farmers to plant “fence row to fence row” while replacing some loans with direct payments. In other words, farmers were encouraged to grow wheat, feed crops, cotton, and other designated commodities, then guaranteed payment for them.

Agricultural subsidies cost taxpayers $19 billion a year and benefit only 3100 farmers.

Thanks to this complicated system of price supports, loans, and deficiency payments (the government even paid producers the “balance” when market prices fell below preset levels) subsidies have evolved beyond their original intent into farm bills that require months of congressional haggling every few years.

This was a recipe not only for overproducing like mad but for making some farmers rich. Today, this program costs taxpayers about $19 billion a year, and benefits only about 3,100 farmers, mostly big growers of—guess what—corn, soy, and other subsidized crops.

The force-feeding of America

Someone had to eat all that food, and it wasn’t the Russians. In fact, it wasn’t being offered to them, because producers found that the way to make the most money possible was to grow grain that would not be eaten directly (we don’t eat much grain anyway) but processed into profitable and easily transportable things like animal feed, white flour, high fructose corn syrup, and oil. (Michael Pollan, in a depressing, amusing, and brilliant article written for The New York Times Magazine in 2003, reminds us that surplus grain was once converted to alcohol; now, in a nation that would rather eat than drink, much of it is converted to sugar and oil.)

Thus commodity foods have remained artificially cheap. As a result, we’re eating about 25 percent percent more calories per day than we were in 1970. We’re also eating about 10 percent more meat, 45 percent more grains (mostly refined), and about 23 percent more sugar.

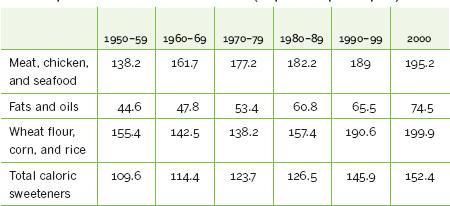

Consumption Rates of Various Foods (in pounds per capita)

None of this should surprise anyone. We’re simply eating more, and though people may argue among themselves that the type of calories matters, not a single expert will question that excess calories incline you to gain weight.

We have looked at some of the factors behind this phenomenon—oversupply and marketing chief among them—and there are others, all of which surged in the 1970s:

- The decline of home cooking, accompanied by a dramatic upswing in restaurant dining. According to the USDA, during the 1970s 18 percent of Americans’ daily calories came from food eaten outside the home. By the mid-1990s this number was 32 percent—nearly double.

- Thanks to USDA recommendations, people who grew up without ever eating a fresh vegetable (unless you count French fries) thought Snackwells were healthy because they were low-fat.

- Meat has become a convenience food (there are barely bones anymore).

- Precooked food from supermarkets and restaurants has become prevalent.

- With masses of women entering the workforce since the 1970s—and cooking not enough of a priority for men to begin sharing the burden—ease and speed of preparation has taken precedence in choosing what to cook and eat.

By the seventies home cooking was in such a sad state that fast food was more flavorful.

Who sees meals with home-cooked breads, desserts, and soups, for example? All these can instead be bought reliably at any store. (Not that they’re good, but they’re there.) Even salads and precooked main courses are now common take-out foods.

It’s worth noting that by the 1970s home cooking was in such a sad state that fast food was considerably more flavorful than what most people were cooking at home. The high fat, salt, and spice content of fast food made it all the more appealing.

The USDA did little to stop these trends. In fact, it was one of the arms of the government that actively participated—whether intentionally or not—in their promotion.

The evolution of the food pyramid

All along, the USDA has walked a tightrope, subsidizing and supporting Big Food on the one hand and trying to fulfill its obligations to American citizens on the other. In 1992, its dietary guidelines (Congress mandated that these be updated every five years, and approved by a panel that includes representatives of the food industry) took the now familiar shape of a pyramid, the implication being that one would eat more from the broad base and less from the narrow top. (It is shown on the next page.)

The pyramid was attacked immediately. Those who maintained that fat intake was too high were outraged that up to six servings of meat and dairy per day were recommended. Those who thought vegetable and fruit intake was too low were incredulous that as few as five servings per day were considered adequate.

And almost every expert outside the industry that would profit from the recommendation found the carbohydrate grouping insane. Nowhere did the pyramid suggest that any of the servings of bread, cereal, rice, and pasta contain whole grains. Every serving could—at least in theory—be highly refined, so that they’d eventually be metabolized just like the sweets that were to be eaten “sparingly.”

As it happened, this was one of those “Our government would never do this, would it?” situations, in which the answer, sadly, is often “Yes.” The pyramid had been shanghaied from its original designer, a nutrition expert at New York University, Luise Light, who consulted on its development for the USDA.

The current food pyramid is so vague and confusing as to be nearly worthless.

Ms. Light’s original pyramid stressed high consumption of vegetables and a low intake of starchy foods. It recommended, for example, two to four servings of whole grain breads and cereals per day, placing them at the top of the pyramid. The USDA panel changed that, increasing the maximum number of servings from four to 11, eliminating any reference to whole grain, and making these the foundation of the diet. Ms. Light has since exposed the corruption and hypocrisy of the people behind the pyramid (unfortunately, though, with not much effect).

A look at today’s pyramid

The current food pyramid, released in 2005, is in some ways more sensible; but it is so vague and confusing as to be nearly worthless, even if you are motivated enough to go online and follow all its links (www.mypyramid.gov). It doesn’t discriminate among fats; it lumps meat and fish together, along with beans, as if eating a steak were the same thing, health-wise, as eating a piece of flounder or a bowl of chickpeas; it doesn’t recommend that any food should be avoided or even minimized; it suggests that half the grains you consume be whole grains, which is the same as saying half should be refined, the kind of carbohydrates that increase the risk of diabetes and heart disease.

And it’s about as anti-intuitive as could be imagined. For example, if you seek advice on how much is needed from the “meat and beans” group, you will read:

The amount of food from the Meat and Beans Group you need to eat depends on age, sex, and level of physical activity. Most Americans eat enough food from this group, but need to make leaner and more varied selections of these foods. Recommended daily amounts are shown in the chart.

When I go to the chart I find that a man my age should be eating about 2.5 ounces of meat per day. Not bad; it’s probably about a third of what most of us currently eat. You’d think that a government agency recommending that Americans cut their meat consumption by more than half would be raising quite a row; but not this government agency, because the USDA doesn’t really want this to happen.

The pyramid recommends a higher intake of dairy (including ice cream) than of vegetables.

Now when I look at dairy, I see that a man my age should be eating three cups of dairy “equivalent” a day (including, if I like, one and a half cups of ice cream), more than my recommended amount of two and a half cups of vegetables.

We would have to look quite hard to find an independent nutritionist or nutrition scientist who believes Americans need to eat more dairy than vegetables, especially in the light of recent findings that plants are probably the most beneficial foods you can eat, and that too much dairy at any age, including childhood (with the exception of breast milk), is worse than not enough. Furthermore, up to 50 million Americans cannot tolerate any dairy in their diet at all.

The pyramid can be picked apart for many other reasons. There are some non-USDA pyramids that actually make sense—see, for example, the one for the Okinawa Diet on www.okinawaprogram.com—but none is available to anyone without a strong motivation to search. Also, the USDA chose the global public relations company Porter Novelli, which has worked for McDonald’s and the Snack Food Association, to design the pyramid itself. In addition, if you’re not computer-savvy the pyramid is virtually impossible to find. And most recently, the USDA has announced that food companies can apply for permission to use the logo on their packaging and marketing materials.

But such sniping is futile: the USDA is simply too easy a target. Even assuming that the science behind the pyramid was accurate, and that nutrition guidance by committee can work, none of this would matter—because the committee’s thirteen members include seven who have ties to food or drug companies (or both) or have received funding from such companies. (One member has petitioned the FDA to exclude refined sugars from food labels!)

The result is that despite the undoubtedly hard work of its more well-intentioned creators—who have at least encouraged us to limit our intake of sugar, meat, and overall calories and have emphasized the benefits of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains—the food pyramid has evolved into a wildly confusing graphic, generating a flood of criticism.

And this is the major public health vehicle—with a paltry $55 million budget—to counter the billions spent by Big Food in its marketing efforts.

Wait. There’s more.