CHAPTER 2

THE

MASTER CARPENTER

The late Tsunekazu Nishioka was a gentle man. With an eventful eight plus decades of life behind him, he sat arguably at the apex of the world of Japanese carpentry. He oversaw a major reconstruction at Hōryūji, Japan’s oldest Buddhist temple. He accomplished the better half of the reconstruction of Yakushiji, which is only slightly younger than its illustrious predecessor at 1,300 years of age. In the process, Nishioka was showered with virtually every major cultural prize bestowed in Japan, both public and private.

Part of his achievement was due to fate, for the position of master carpenter of a major temple or shrine is virtually hereditary, and in 1908 Nishioka was born into the family that had produced master carpenters for Hōryūji temple for five or six generations. Those bearing the Nishioka name represent only one branch of a larger family which claims as an ancestor the builder of Osaka Castle in the early seventeenth century. Hideyoshi, the lord for whom the castle was built, ordered the builder killed because of his knowledge of the castle’s secrets, but Katsumoto Katagiri, a high-ranking warrior, helped him escape, whereupon he found a quieter life for himself as a carpenter at Hōryūji.

Figure 15 Tsunekazu Nishioka at his desk at the Yakushiji work site, 1986. Hanging on the wall are numerous wooden drawing templates for plotting roof curves, etc.

Nishioka’s father was actually a farmer who had been adopted into the carpentry family as a precaution against starvation at the end of the nineteenth century, which were lean years for Hōryūji. But Nishioka’s grandfather was the temple’s master carpenter, and he permitted Nishioka to frequent the workshop from the age of three or four. After entering elementary school in 1915, Nishioka helped out with the sweeping, the fetching of tea, and such during his summer vacation. His grandfather insisted, against Nishioka’s expectations and his father’s wishes, that the boy be further educated at an agricultural school, which he entered in 1921. Grandfather Nishioka reasoned that the family should have at least one person capable of farming in times of shortage, and that, in addition, a carpenter should learn as much as possible about wood. As a result, Nishioka devoted four years to absorbing the latest scientific knowledge about earth, fertilizer, forestry, and husbandry.

After finishing school in 1924, Nishioka expected to begin carpentry work immediately, but was told to first spend one year growing rice. Only then, under his grandfather’s supervision, was he allowed to handle tools, beginning with learning how to sharpen them. At the same time, he was taught how to conduct relationships with other carpenters, and at night he listened to explanations of the carpenters’ kokoroe, or rules of thumb. These oral teachings, as transmitted by his grandfather, formed the core of Nishioka’s values and ethic.

Nishioka worked as an apprentice for about a decade, with an interruption for military service beginning in 1929. His early projects included minor repairs on various buildings at Hōryūji, the complete dismantling and restoration of other temples in the Nara area, construction of a new Shintō shrine, and the erection of a gate for a new palace for an imperial prince. In 1931, he made a detailed 1/10-scale study model of the Hōryūji five-story pagoda (now in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum). On some smaller projects, he acted as master carpenter; at other times, he was assistant master. In 1934, he assumed the responsibilities of master carpenter for major dismantling and reconstruction work at Hōryūji, a maintenance operation that is usually carried out every 200 years. This project, called the Hōryūji Shōwa-Era Great Reconstruction, was Nishioka’s major formative experience as a master temple carpenter.

Figure 16 In the last decades of his life, Nishioka’s main roles were as a planner and teacher.

During the reconstruction of Hōryūji, Nishioka discovered that the original builders had cut all of their hinoki from the hills in the Yamato area (the region surrounding Nara), and that their use of lumber—the matching of a tree’s natural qualities with its ultimate placement in a building—was in keeping with the oral precepts that had been handed down to him. “Different mountains make different wood,” he said, adding that “building is a matter of matching the individual personalities [of trees as well as carpenters].” Traditional carpenter’s wisdom provides innumerable guidelines for exploiting the unique characteristics of different trees, utilizing twists so that they counteract each other, making sure that trees which grew on the southern face of the mountain are used in the southern side of the building, and so on. “Coming from a family of craftsmen, I had learned these principles already,” he said, “but it was only when I took the buildings to pieces that I discovered that all of Hōryūji was constructed in this way. I was extremely moved. The oral tradition had been applied without exception.” But the ancient standards were not always maintained, he said, and the results could be seen in repair work carried out some six centuries ago. “They simply matched good-looking trees with good-looking trees. When I rebuilt, I reverted to the old ways, perceiving the nature of individual trees, matching them north and south” (“After 51 Years, a Temple Is Restored,” Washington Post, 26 December 1985).

Thus, fortune was smiling when it fell to Nishioka to oversee this rare dismantling and repair work at Hōryūji, to check up on, so to speak, the work of his predecessors of a millennium past. “The old builders were people of art who approached their work with religious devotion,” he said. “They had no way to know how their creation would fare over the span of thirteen centuries. The privilege of finding out fell to me. I felt like a highest level doctor of anatomy” (Washington Post). In his consummately informed opinion, the buildings at Hōryūji were good for at least another 2,000 years, provided they received regular checkups and proper maintenance.

It was during the early stages of the Hōryūji restoration that he fully realized the benefit of his agricultural education. On one occasion he was called upon to examine the soil under the foundations of the temple’s eastern precinct, an analysis which won him the respect and recognition of his colleagues. He often maintained that his education had served him well: “These are the things a person needs to know in order to make a house.... If he is going to make a wall, he needs to know what kind of earth is good. If he is going to make tiles for a roof, the same holds true.... And, of course, if he uses wood, he should know how and why it grows like it does” (Teiji Itō, ed., Dōkyū no Shokunin, Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1985, p. 57).

“The Hōryūji five-story pagoda and the Yakushiji eastern pagoda are both constructed of wood which had been growing for 1,000 to 1,300 years.... That means, altogether, each of those trees has been standing for 2,600 years!” He gave as an example: “Hinoki is strongest 200–300 years after cutting.... This is traditional wisdom, so I was extremely pleased that recent research by Professor Jirō Kohara [a forestry specialist] confirmed it” (Dōkyū no Shokunin, p. 66). A sparkle would come into Nishioka’s eyes when he talked about hinoki (cypress), his favorite wood. “There are six species of hinoki in the world, but Japan’s is the best quality. That is why shiraki zukuri [bare wood construction] began here. The six types are Japanese hinoki—which was called ma-ki, or ‘true wood,’ by the ancients—sawara, an inferior species found in Japan, tai-hi [Taiwanese cypress], and three species of North American cypress.... The cell structure of Japanese hinoki,” of which the very best comes from the Yoshino region where it is favored by particularly fine soil, he said, “is very tight. It has a straight grain, nice color, and a delicate aroma. It is stable and easily planed, but it is unforgiving, so one must work it with only the best tools. If a sculptor tries hinoki just once, he will never want to touch any other wood” (Jirō Kohara, Nihonjin to Ki no Bunka, Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, 1984, pp. 100–1).

Temple construction requires high-grade logs of large girth, which means of great age—ideally the 1,000 or more years that went into the columns of Hōryūji and Yakushiji. But such trees have become extremely scarce in periodically deforested Japan. As a result, Nishioka had to make several trips to Taiwan to select wood for the reconstruction of Yakushiji, begun in 1970. One of the carpenters’ sayings, he related, is: “Don’t buy trees; buy a mountain.” Thus, the temple purchased large forested tracts in Taiwan for use in the restoration project. Taiwanese hinoki is very similar to the Japanese variety, but somewhat less elastic, a feature which at times requires structural members—particularly roof beams, which fortunately are hidden—to be made larger in section than traditional design dictates. But age is not always an assurance of quality, he observed. “I saw some 2,000-year-old hinoki growing in Taiwan, but their leaves were lighter than those of other trees only 200 years old. Dark leaves are a better sign. The branches of the trees with the paler leaves were sagging because they were rotten inside” (Tsunekazu Nishioka, Ki ni Manabe, Tokyo: Shōgakkan, 1988, p. 200).

Although Nishioka valued the contribution his formal education made to his development, he regarded it as something which, while helpful, was not essential, especially when it came to training one’s sense of perception. “Academics,” he said, “can be very foolish. They take simple things and make them difficult.... Japanese society today measures people by their educational credentials, with the lamentable result that other equally valid ways of learning are being forgotten, even though they’re backed by 1,300 years of experimental observation in Japan alone. And this has happened so quickly: in a mere 100 years, thirteen centuries of accumulated knowledge has been allowed to leak out of our culture, not just in architecture, but everywhere.”

Because the craftsman’s knowledge is based on experience, on endless repetition and refinement, and on direct imitation of a master’s methods, a technique or attitude disappears with its possessor if not passed on through use. After the demise of a living tradition, one can analyze its artifacts for clues to their creation or try to reconstruct the methodology based on writings or oral traditions, but something essential is inevitably lost. During the premodern era, there was an active dialogue among Japanese carpenters and a sense of competition which resulted in constant innovation and perceptible improvement in skills for the craft as a whole, all done while struggling against a progressively diminishing quality of available wood. But at that time, wood construction represented the only technology available for building in Japan; nowadays, it is used extensively only in prefabricated houses, and in a manner which is increasingly automated. In the face of interlocking industries which have settled upon steel and concrete as the most practical and profitable means of construction, wood has become something of a luxury. Likewise, the traditional means of training carpenters, which had long produced a steady stream of highly skilled craftsmen through a self-regulating apprenticeship system, has now been almost completely dismantled in favor of universal standardized education geared toward the production of office workers and technicians. Carpentry, even temple carpentry, is far from being a lucrative occupation, partly because the Japanese value system has come to disdain manual labor. “Young people? No, they don’t want to do this kind of work anymore,” observed Nishioka wryly. Most carpenters seem to agree that actual development, in the sense of positive innovation and improvement, is no longer possible in the field. “It is impossible to improve on the ancients,” Nishioka insisted. “They were incomparably better. The most I can do is to keep a small fraction of their knowledge alive.”

Some may be able to accept this decline, this cultural deskilling, without feeling any sense of loss. In fact, many Japanese regard it as regrettable but inevitable. Others, however, feel that it is neither inevitable nor inconsequential, but rather a case of painful and unwarranted negligence. The carpenters themselves, including the younger apprentices, carry themselves with the esprit that marks the last of a great breed. To share their life is to share their pain, which they generally keep well hidden except when drunk. One young carpenter, near the end of a long day of intoxicated celebration, turned to me with a grave countenance and pleaded, “You said it’s painful to see how few of us are left. Suffer more, please. Then you might learn how we feel.”

Needless to say, crafts are inseparable from the culture in which they are found; they are products of a complex set of interactions, a mirror of social relations. The vigor of any one part is a sign of the vigor of the entire organism, like the color of the leaves on a tree. For instance, Japanese carpenters are dependent upon the finely wrought tools that evolved concurrently with their craft. What happens when the makers of these tools begin to disappear as demand for their work declines? This has been occurring for decades. Carpenters cannot work without adequate supplies of wood, but such supplies are now dwindling throughout the world. Other crafts vital to temple building are suffering similar fates, among them traditional sculpture, painting, and metalworking. During their premodern heyday, these crafts formed a coherent whole, a dynamic and interdependent living system not unlike a temple itself.

The master carpenter is the crucial peg in this system. His primary task is to bring together the necessary people and act as the center. He must have extremely broad knowledge, embracing all the related crafts, and a comprehensive viewpoint that holds everything together. If this central peg is removed, the entire system collapses.

In order to maintain continuity with the past, one of the master carpenter’s most vital functions is that of education: training those who work under him. In real terms, this means providing them with the best possible example and allowing them to learn through observation and experience. Rarely is anything explained fully to the apprentice; he must draw his own conclusions and develop his own instincts. The reasons behind given instructions become evident in time, and no amount of prior speculation or analysis is as effective a learning tool as witnessing an actual process in an alert frame of mind. Some factors, such as the natural settling and movement of wooden structural members over time, can be grasped only after several years of observation, and then only if the carpenter has his original actions continually in mind. Nishioka, for his part, lived in close contact with the entire body of his work, which spanned six decades. He was continually forced to assess his successes and failures, seeing where the wood had taken unforeseen twists, where he had been hasty or distracted while working.

Figure 17 Nishioka checking his inkpot and line (sumitsubo).

Consequently, Nishioka was a strict teacher, seeking to form carpenters from the heart outward, as it were. Priority was given to instilling in the young apprentice a sense of respect and humility, not merely toward his superiors but, more importantly, toward the wood and the work. The first tasks are deceptively simple: sweeping the shop floor, fetching tea, helping to lift heavy members. Yet, even these seemingly mindless tasks have the potential to teach concentration, exactitude, and teamwork, all of which are absolutely essential for the more complicated work ahead. Once an apprentice has begun to develop the proper attitude, he is gradually introduced to tools and begins to assist the senior carpenters with their individual responsibilities. In about seven years, he will be capable of shaping a complex piece from shop drawings and templates; after fifteen years or so, he will know how to make the templates himself from the master’s drawings.

A major project, such as that at Yakushiji, involved, during its busiest periods, about two dozen carpenters of widely varying ages and experience. The core of this crew was composed of seven or eight workers who had been associated with Nishioka as apprentices for a number of years. Other experienced carpenters were taken on for a year or so. At times, even senior carpenters would leave to work on other projects for a few months, or even years, returning to Nishioka’s workshop when they were needed. The result was a loose network of carpenters, sometimes far-flung (but generally within the Kansai area), who formed a pool of well-trained labor. And all had been molded in some way by the philosophy that Nishioka expressed so lucidly. While most of the carpenters, and the senior assistants in particular, were wary of verbalizing their intentions, occasionally philosophical observations did emerge. One day, a thirty-year-old assistant master, seemingly frustrated by my insistent questions about aspects of design related to wood movement, blurted out, “Only three things are important: sun, wind, and rain. If you understand these things, you can understand wood. If you understand wood, you can be a carpenter.” On another occasion, a much older carpenter, while walking to lunch, for no apparent reason pointed to a puddle left by the previous day’s rains and said, “It’s moving. It’s all moving,” a statement rendered even pithier by its brevity in Japanese.

At Yakushiji, Nishioka spent almost all of his time on design work, leaving the day-to-day training of apprentices to the senior carpenters. Nonetheless, he periodically checked on everyone’s progress, offering his criticism and encouragement. When actually supervising some aspect of the work, he had the bearing of a general in the field, barking orders and accepting no questions. Because of his well-earned status and uncanny perception, even the most senior apprentices were awed in his presence, some of them trembling at the thought of the reprimand he would deal should some barely perceptible flaw be discovered in their work.

On one occasion, a relatively new apprentice related a not so traumatic but memorable criticism he had received. “I was planing a block of wood and I hadn’t quite gotten the hang of it. For some reason, it wasn’t going smoothly. Nishioka was walking across the shop floor about 20 feet away, too far away to see what I was doing, but he called out, ‘You’re bearing down too hard on the back of the plane. I can tell by the sound.’ Sure enough, I adjusted my grip, and the problem was solved.” Another carpenter related how he was taught to distinguish the region in which a particular piece of Japanese hinoki was grown on the basis of its smell, with that of northern species being palpably sharper. On another occasion, I watched four senior carpenters standing at attention, silently accepting a stiffrebuke from the master. Their crime: someone had miscalculated a few millimeters on a hip rafter. The difference was hardly noticeable, even close up, but since the beam was designed to achieve its perfect form only after several years of sagging and shrinking, this small error would be magnified and possibly distort the whole. Fumed Nishioka, “They’ll laugh at me. They’ll say, ‘That’s not the way a hip rafter should look!’ And I won’t be around to defend myself.”

Figure 18 Nishioka inspecting his tools.

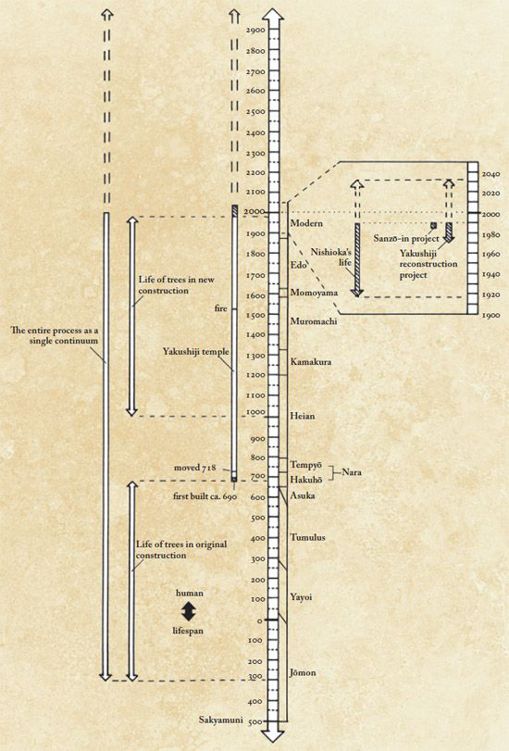

Indeed, the most remarkable thing about Nishioka was his sense of time, time as measured in centuries and millennia (Fig. 19). His viewpoint was purely Buddhist: time is cyclical, the universe is constantly being destroyed and remade, over countless eons, throughout all of which our spirits are intact. Life is painful, especially when compared with the intervals between death and rebirth. “If a carpenter dedicates himself spiritually to the construction of a temple, and that temple lasts a thousand years, then he will have a thousand-year interval between this life and the next. Consequently, that thousand years really isn’t very long. And when you think that a tree takes a thousand years to grow large enough to use for a temple column, and that the temple may stand for a millennium or more, even a decade spent in its construction is infinitesimal.” Nishioka believed that one should take as much time as necessary. One should concentrate completely all the while, and be in good spirits, because a craftsman’s frame of mind permeated every aspect of his work, and the work would bear the imprint of its creator as long as it existed.

Admittedly, it is difficult for most of us to consider a thousand years as a brief period, or to believe we can delay our rebirth by dint of diligent work. Nishioka, however, was convinced that the ancient Japanese temples, several of which are over a thousand years old, were built in the spirit he described, and that the same spirit can be maintained today. This is what he attempted at Yakushiji.

Figure 19 A temple carpenter’s timetable.