Chapter 1 — THE SERPENT’S BRIDE

I. The Mother Goddess Eve

No one familiar with the mythologies of the goddess of the primitive, ancient, and Oriental worlds can turn to the Bible without recognizing counterparts on every page, transformed, however, to render an argument contrary to the older faiths. In Eve’s scene at the tree, for example, nothing is said to indicate that the serpent who appeared and spoke to her was a deity in his own right, who had been revered in the Levant for at least seven thousand years before the composition of the Book of Genesis. There is in the Louvre a carved green steatite vase, inscribed c. 2025 b.c. by King Gudea of Lagash, dedicated to a late Sumerian manifestation of this consort of the goddess, under his title Ningizzida, “Lord of the Tree of Truth.” Two copulating vipers, entwined along a staff in the manner of the caduceus of the Greek god of mystic knowledge and rebirth, Hermes, are displayed through a pair of opening doors, drawn back by two winged dragons of a type known as the lion-bird (Figure l).Note 1

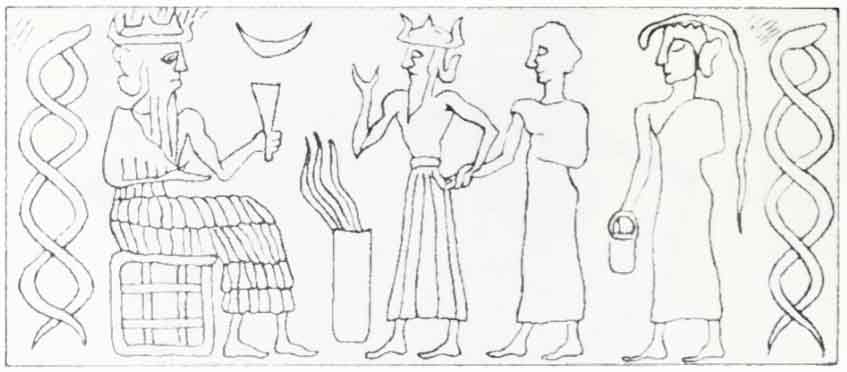

Figure 1. The Serpent Lord

The wonderful ability of the serpent to slough its skin and so renew its youth has earned for it throughout the world the character of the master of the mystery of rebirth — of which the moon, waxing and waning, sloughing its shadow and again waxing, is the celestial sign. The moon is the lord and measure of the life-creating rhythm of the womb, and therewith of time, through which beings come and go: lord of the mystery of birth and equally of death — which two, in sum, are aspects of one state of being. The moon is the lord of tides and of the dew that falls at night to refresh the verdure on which cattle graze. But the serpent, too, is a lord of waters. Dwelling in the earth, among the roots of trees, frequenting springs, marshes, and water courses, it glides with a motion of waves; or it ascends like a liana into branches, there to hang like some fruit of death. The phallic suggestion is immediate, and, as swallower, the female organ also is suggested; so that a dual image is rendered, which works implicitly on the sentiments. Likewise a dual association of fire and water attaches to the lightning of its strike, the forked darting of its active tongue, and the lethal burning of its poison. When imagined as biting its tail, as the mythological ouroboros, it suggests the waters that in all archaic cosmologies surround — as well as lie beneath and permeate — the floating circular island Earth.

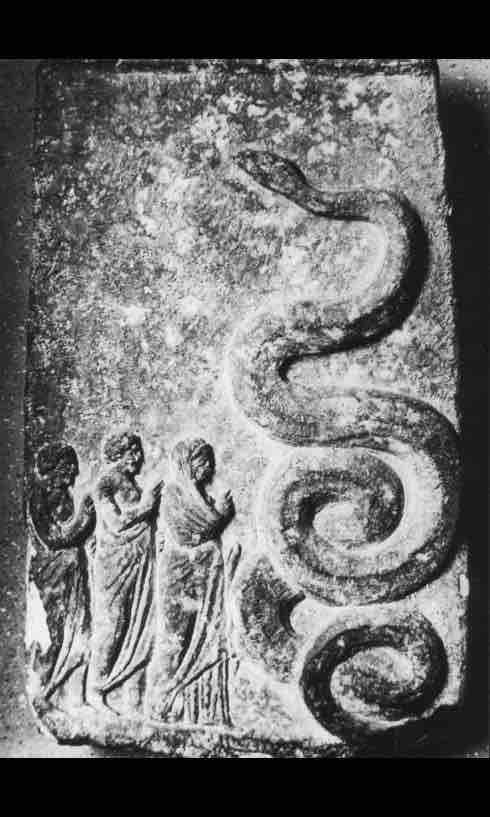

Figure 2. The World Tree

Figure 2, from an Elamite painted bowl of the late Sassanian period (226–641 a.d.), shows again the ancient guardian of the World Tree, up the trunk of which it coils.Note 2 In this form the dangerous, warning aspect of the presence is apparent. However, like the serpent in the Garden, Ningizzida is generally favorable to those who, with due respect, approach the boon of his sanctuary. Figure 3, from an early Akkadian seal of c. 2350-2150 b.c., displays the deity in human form, enthroned, with his caduceus emblem behind and a fire altar before.Note 3 Being conducted into his presence by a crowned divinity is a devotee, the owner of the seal, followed by a figure bearing a pail, with a serpent dangling from his head, who is an attendant of the god enthroned and corresponds to the lion-bird porters of Gudea’s cup. The moon, the source of the waters of life, hangs above the cup elevated in the god’s hand, whence the introduced initiate is now to imbibe.

Figure 3. The Serpent Lord Enthroned

Here an association of the serpent lord, the cup of immortality, and the moon is obvious; equally so a motif common to all antique mythologies, namely, the multiple appearance of a god simultaneously in higher and lower aspects. For the porter at the gate, admitting or excluding aspirants, is a reduced manifestation of the power of the deity itself. He is the aspect first experienced by anyone approaching the presence; or, phrased another way, the testing aspect of the god. Moreover, the god — and his testing aspect, too — may appear in any one or more of a number of forms together: anthropomorphic, theriomorphic, vegetal, heavenly, or elemental; as, in the present instance: man, snake, tree, moon, and the water of life — which are to be recognized as aspects of a single polymorphous principle, symbolized in, yet beyond, all.

Figure 4. Axis Mundi

A series of three further seals will suffice to bring these symbols into relationship with the Bible. The first is the elegant Syro-Hittite example of Figure 4,Note 4 which shows the Mesopotamian hero Gilgamesh in dual manifestation, serving as the guardian of a sanctuary, in the way of the lion-birds of Gudea’s cup. But what we find within this sanctuary is of neither human, animal, nor vegetal form; it is a column made of serpent-circles, bearing on its top a symbol of the sun. Such a pole or perch is symbolic of the pivotal point around which all things turn (the axis mundi), and so is a counterpart of the Buddhist Tree of Enlightenment in the “Immovable Spot” at the center of the world.Note 5 Around the symbol of the sun, atop the column, four little circles are to be seen. These, we are told, symbolize the four rivers that flow to the quarters of the world.Note 6 (Compare the Book of Genesis 2:10-14.) Approaching from the left is the owner of the seal, conducted by a lion-bird (or cherub, as such apparitions are termed in the Bible) bearing in its left hand a pail and in its right an elevated branch. A goddess follows in the role of the mystic mother of rebirth, and below is a guilloche — a labyrinthine device that in this art corresponds to the caduceus. So that, again, we recognize the usual symbols of the mythic garden of life, where the serpent, the tree, the world axis, sun eternal, and ever-living waters radiate grace to all quarters — and toward which the mortal individual is guided, by one divine manifestation or another, to the knowledge of his own immortality.

Figure 5. The Garden of Immortality

In the next seal, Figure 5, where the bounty of the mythic garden is shown, all the personages are of the female sex. The two attending the tree are identified as a dual apparition of the underworld divinity Gula-Bau, whose classical counterparts are Demeter and Persephone.Note 7 The moon is directly above the fruit being offered, as in Figure 3 above the cup. And the recipient of the boon, who is already holding one branch of fruit in her right hand, is a mortal woman.

Thus we perceive that in this early mythic system of the nuclear Near East — in contrast to the later, strictly patriarchal system of the Bible — divinity could be represented as well under feminine as under masculine form, the qualifying form itself being merely the mask of an ultimately unqualified principle, beyond, yet inhabiting, all names and forms.

Nor is there any sign of divine wrath or danger to be found in these seals. There is no theme of guilt connected with the garden. The boon of the knowledge of life is there, in the sanctuary of the world, to be culled. And it is yielded willingly to any mortal, male or female, who reaches for it with the proper will and readiness to receive.

Figure 6. The Goddess of the Tree

Hence the early Sumerian seal of Figure 6Note 8 cannot possibly be, as some scholars have supposed, the representation of a lost Sumerian version of the Fall of Adam and Eve.Note 9 Its spirit is that of the idyll in the much earlier, Bronze Age view of the garden of innocence, where the two desirable fruits of the mythic date palm are to be culled: the fruit of enlightenment and the fruit of immortal life. The female figure at the left, before the serpent, is almost certainly the goddess Gula-Bau (a counterpart, as we have said, of Demeter and Persephone), while the male on the right, who is not mortal but a god, as we know from his horned lunar crown, is no less surely her beloved son-husband Dumuzi, “Son of the Abyss: Lord of the Tree of Life,” the ever-dying, ever-resurrected Sumerian god who is the archetype of incarnate being.

Figure 7. Demeter

A fitting comparison would be with the Greco-Roman relief shown in Figure 7,Note 10 where the goddess of the Eleusinian mysteries, Demeter, is seen with her divine child Ploutos, or Plutus (not the same as Plouton or Pluto, god of the netherworld, though frequently identified with him by assimilation of the names), of whom the poet Hesiod wrote:

Happy, happy is the mortal who doth meet him as he goes,

For his hands are full of blessings and his treasure overflows.Note 11

Plutus, on one plane of reference, personifies the wealth of the earth, but in a broader sense is a counterpart of the god of mysteries, Dionysus. In Primitive Mythology and Oriental Mythology I have discussed a number of such deities who are at once the consorts and sons of the Great Goddess of the Universe. Returning to her bosom in death (or, according to another image, in marriage), the god is reborn — as the moon sloughing its shadow or the serpent sloughing its skin. Accordingly, in those rites of initiation with which such symbols were associated (as in the mysteries of Eleusis), the initiate, returning in contemplation to the goddess mother of the mysteries, became detached reflectively from the fate of his mortal frame (symbolically, the son, who dies), and identified with the principle that is ever reborn, the Being of all beings (the serpent father): whereupon, in the world where only sorrow and death had been seen, the rapture was recognized of an everlasting becoming.

Compare the legend of the Buddha. When he placed himself on the Immovable Spot beneath the Tree of Enlightenment, the Creator of the World Illusion, Kāma-Mara, “Life-Desire and Fear of Death,” approached to threaten his position. But he touched the earth with the fingers of his right hand and, as the legend tells, “The mighty Goddess Earth thundered with a hundred, a thousand, a hundred thousand roars, declaring: ‘I bear you witness!’; and the demon fled.”Note 12 The Blessed One that night achieved Enlightenment, and for seven times seven days remained absorbed in rapture, during which time a tremendous tempest arose. “And a mighty serpent king named Mucalinda,” we then read,

emerging from his place beneath the earth, enveloped the body of The Blessed One seven times with its folds, spreading his great hood above his head, saying “Let neither cold nor heat, nor gnats, flies, wind, sunshine, nor creeping creatures come near The Blessed One!” Whereafter, when seven days had elapsed and Muchalinda knew that the storm had broken up, the clouds having dispersed, he unwound his coils from the body of The Blessed One and, assuming human form, with joined hands to forehead, did reverence to The Blessed One.Note 13

In the lore and legend of the Buddha the idea of release from death received a new, psychological interpretation, which, however, did not violate the spirit of its earlier mythic representations. The old motifs were carried to an advanced statement and given fresh immediacy through association with an actual historical character who had illustrated their meaning in his life; yet the sense of accord remained between the questing hero and the powers of the living world, who, like himself, were ultimately but transformations of the one mystery of being. Thus in the Buddha legend, as in the old Near Eastern seals, an atmosphere of substantial accord prevails at the cosmic tree, where the goddess and her serpent spouse give support to their worthy son’s quest for release from the bondages of birth, disease, old age, and death.

In the Garden of Eden, on the other hand, a different mood prevails. For the Lord God (the written Hebrew name is Yahweh) cursed the serpent when he knew that Adam had eaten the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil; and he said to his angels: “ ‘Behold, the man has become like one of us, knowing good and evil; and now, lest he put forth his hand and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever’ — therefore Yahweh sent him forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from which he was taken. He drove out the man; and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim [i.e., lion-birds], and a flaming sword which turned every way, to guard the way to the tree of life.”Note 14 The first point that emerges from this contrast, and will be demonstrated further in numerous mythic scenes to come, is that in the context of the patriarchy of the Iron Age Hebrews of the first millennium b.c., the mythology adopted from the earlier neolithic and Bronze Age civilizations of the lands they occupied and for a time ruled became inverted, to render an argument just the opposite to that of its origin. And a second point, corollary to the first, is that there is consequently an ambivalence inherent in many of the basic symbols of the Bible that no amount of rhetorical stress on the patriarchal interpretation can suppress. They address a pictorial message to the heart that exactly reverses the verbal message addressed to the brain; and this nervous discord inhabits both Christianity and Islam as well as Judaism, since they too share in the legacy of the Old Testament.

However, the Bible is not the only source in the West of such ambivalence of teaching. There is a like inversion of sense in the legacy of Greece.

II. The Gorgon’s Blood

Jane Ellen Harrison demonstrated over half a century ago that in the field festivals and mystery cults of Greece numerous vestiges survived of a pre-Homeric mythology in which the place of honor was held, not by the male gods of the sunny Olympic pantheon, but by a goddess, darkly ominous, who might appear as one, two, three, or many, and was the mother of both the living and the dead. Her consort was typically in serpent form; and her rites were not characterized by the blithe spirit of manly athletic games, humanistic art, social enjoyment, feasting and theater that the modem mind associates with Classical Greece, but were in spirit dark and full of dread. The offerings were not of cattle, gracefully garlanded, but of pigs and human beings; directed downward, not upward to the light; and rendered not in polished marble temples, radiant at the hour of rosy-fingered dawn, but in twilight groves and fields, over trenches through which the fresh blood poured into the bottomless abyss. “The beings worshiped,” Miss Harrison wrote, “were not rational human, law-abiding gods, but vague, irrational, mainly malevolent δαίμονες, spirit-things, ghosts and bogeys and the like, not yet formulated and enclosed into god-head.”Note 15 The atmosphere of the rituals, furthermore, was not of a shared feast, in the simple spirit of do ut des, “I give, so that thou shouldst give,” but of riddance: do ut abeas, “I give, so that thou shouldst depart”; to which, however, there was always joined the idea that if the negative aspect of the daemon were dispelled, health and well-being, fertility and fruit, would issue of themselves from their natural source.

Figure 8. Zeus Meilichios

Figure 8 is from a votive tablet found in the Piraeus, dedicated to a form of Olympian Zeus known as Zeus Meilichios.Note 16 But that heavenly Zeus — of all gods! — should have assumed the form of a serpent is amazing; for, as Miss Harrison points out: “Zeus is one of the few Greek gods who never appear attended by a snake.”Note 17 Her explanation of the anomaly is that both the name and the figure belonged originally to a local daemon, the son-husband of the mother-goddess Earth, whose cult site in the Piraeus was taken over by the conquering high god of the Aryan pantheon from the north. To Zeus’s name that of the local earth-spirit then was added as an epithet. And the annual spring rites of the daemon’s cult also were assumed, together with their un-Olympian type of sacrifice — a holocaust of pigs — carried out, as one Greek commentator observed, “with a certain element of chilly gloom.”Note 18

Chilly gloom, however, is not the atmosphere that one associates with the Bronze Age civilizations of pre-Homeric, Minoan Crete and the contemporary Cycladic Isles, from which most of these un-Hellenic cults appear to have been derived. The atmosphere suggested in their lovely works of art, on the contrary, is of a graceful accord with the majesty of the cosmic process. Nor can it be claimed that even in later Classical times the old mother-goddess, amid her entourage of serpents, lions, fishponds, dovecotes, turtles, squids, goats, and bulls, was always a personage feared and abhorred. Sir James G. Frazer, in The Golden Bough, it is true, has shown that her cult in the now famous grove at Lake Nemi, near Rome, was indeed dark and ominous enough.

“In this sacred grove,” as he has described the site in the opening pages of his great work,

there grew a certain tree round which at any time of the day, and probably far into the night, a grim figure might be seen to prowl. In his hand he carried a drawn sword, and he kept peering warily about him as if at every instant he expected to be set upon by an enemy. He was a priest and a murderer; and the man for whom he looked was sooner or later to murder him and hold the priesthood in his stead. Such was the rule of the sanctuary. A candidate for the priesthood could only succeed to office by slaying the priest, and having slain him, he retained office till he was himself slain by a stronger or a craftier. The post which he held by this precarious tenure carried with it the title of king; but surely no crowned head ever lay uneasier, or was visited by more evil dreams, than his. For year in, year out, in summer and winter, in fair weather and in foul, he had to keep his lonely watch, and whenever he snatched a troubled slumber it was at the peril of his life.Note 19

A somber scene, indeed! And we have others too from the annals of Greece and Rome that produce the same atmosphere of dread: the oft-told tale, for example, of Queen Pasiphae of Crete, her love for a bull from the sea; and their child, the terrible Minotaur, pacing to and fro in the labyrinth built to cage him. However, still other pre-Hellenic ritual scenes suggest an idyll, rather, of harmony and peace, wisdom and a power of prophecy, for those in whose heart there is no fear of spooks. In a treatise “On the Nature of Animals” the Roman author Aelian (d. 222 a.d.) described a serpent sanctuary at Epirus that was said in his time to be of the god Apollo, but was actually — like the serpent shrine of Zeus Meilichios — the vestige of an earlier, pre-Hellenic Aegean mythology.

The people of Epirus sacrifice in general to Apollo, and on one day of the year they celebrate to him their chief feast, a feast of great magnificence, much reputed. There is a grove dedicated to the god, with a circular enclosure, within which are snakes — playthings, surely, for the god. And they are approached only by the maiden priestess. She is naked, and she brings to the snakes their food. These snakes are declared by the people of Epirus to be descended from the Python at Delphi. And now, if when the priestess approaches them the snakes are seen to be gentle, and if they take to their food kindly, that is said to mean that there will be a plentiful year and free from disease; but if they frighten her and do not take the honey cakes she offers, they portend the reverse.Note 20

Figure 9. The Tree of the Hesperides

Or let us regard the vase painting of Figure 9, which, in essentially the same spirit, shows the mythic tree of the golden apples in the sunset-land of the Hesperides.Note 21 An immense horned snake coils up around the tree, and from a cave in the earth at its root water wells from a spring with double mouth, while the lovely Hesperides themselves — a family of nymphs known to antiquity as daughters born without father to the cosmic goddess NightNote 22 — are in attendance round about. And all is precisely as things would have remained in Eden, too, if the recently installed patriarch of the estate (who was developing his colorable claim to priority not only of ownership but even of being) had not taken umbrage when he learned what things were going on.

For it is now perfectly clear that before the violent entry of the late Bronze and early Iron Age nomadic Aryan cattle-herders from the north and Semitic sheep-and-goat-herders from the south into the old cult sites of the ancient world, there had prevailed in that world an essentially organic, vegetal, non-heroic view of the nature and necessities of life that was completely repugnant to those lion hearts for whom not the patient toil of earth but the battle spear and its plunder were the source of both wealth and joy. In the older mother myths and rites the light and darker aspects of the mixed thing that is life had been honored equally and together, whereas in the later, male-oriented, patriarchal myths, all that is good and noble was attributed to the new, heroic master gods, leaving to the native nature powers the character only of darkness — to which, also, a negative moral judgment now was added. For, as a great body of evidence shows, the social as well as mythic orders of the two contrasting ways of life were opposed. Where the goddess had been venerated as the giver and supporter of life as well as consumer of the dead, women as her representatives had been accorded a paramount position in society as well as in cult. Such an order of female-dominated social and cultic custom is termed, in a broad and general way, the order of Mother Right. And opposed to such, without quarter, is the order of the Patriarchy, with an ardor of righteous eloquence and a fury of fire and sword.

Hence, the early Iron Age literatures both of Aryan Greece and Rome and of the neighboring Semitic Levant are alive with variants of the conquest by a shining hero of the dark and — for one reason or another — disparaged monster of the earlier order of godhood, from whose coils some treasure was to be won: a fair land, a maid, a boon of gold, or simply freedom from the tyranny of the impugned monster itself.

The chief biblical example was Yahweh’s victory over the serpent of the cosmic sea, Leviathan, of which he boasted to Job. “Can you draw Leviathan out with a fishhook, or press down his tongue with a cord? Can you put a rope into his nose, or pierce his jaw with a hook? Will he make many supplications to you? Will he speak to you soft words? Will he make a covenant with you to take him for your serpent for ever? Will you play with him as with a bird, or will you put him on leash for your maidens? Will traders bargain over him? Will they divide him up among the merchants? Can you fill his skin with harpoons, or his head with fishing spears? Lay hands on him; think of the battle; you will not do it again.”Note 23

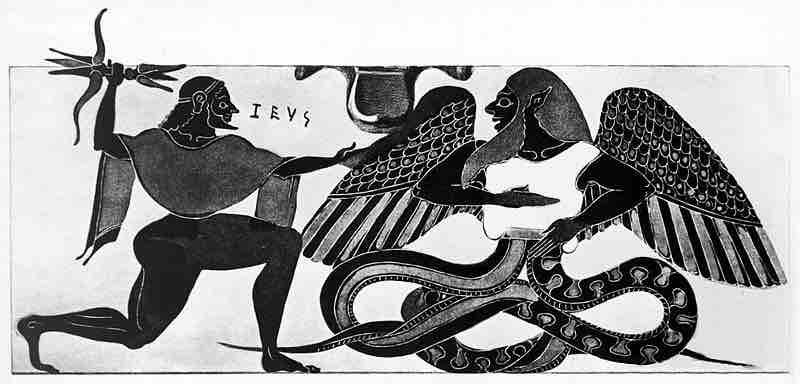

Figure 10. Zeus against Typhon

The counterpart for the Greeks was the victory of Zeus over Typhon, the youngest child of Gaea, the goddess Earth — by which deed the reign of the patriarchal gods of Mount Olympus was secured over the earlier Titan broods of the great goddess mother. The Titan’s form, half man, half snake, we are told, was enormous. He was so large that his head often knocked against the stars and his arms could extend from sunrise to sunset (Figure 10). From his shoulders, according to Hesiod’s account, there reared a hundred serpent heads, all flashing fiery tongues, while flames darted from the many eyes. Within could be heard voices, sending out sounds the gods could understand; but also bellowing like bulls, roaring like lions, baying like dogs, or hissing, so loudly that the mountains echoed. And this terrible thing would have become the master of creation had not Zeus gone against him in combat.

Beneath the feet of the father of the gods Olympus shook as he moved, the earth groaned; and from the lightning of his bolt, as well as from the eyes and breath of his antagonist, fire was bursting over the dark sea. The ocean boiled; towering waves beat upon all promontories of the coast; the ground quaked; Hades, lord of the dead, trembled; and even Zeus himself, for a time, was unstrung. But when he had summoned again his strength, gripping his terrific weapon, the great hero sprang from his mountain and, hurling the bolt, set fire to all those flashing, bellowing, roaring, baying, hissing heads. The monster crashed to earth, and the earth-goddess Gaea groaned beneath her child. Flames went out from him, and these ran along the steep mountain forests, roaring, so hot that much of the earth dissolved, like iron in the flaming forge within the earth of the lame craftsman of the gods, Hephaestus. And then the mighty king of the gods, Zeus, prodigious in storming wrath, heaved the flaming victim into gaping Tartarus — whence to this day there pour forth from his titan form all those winds that blow terribly across seas and bring to mortal men distress, scatter shipping, drown sailors, and ruin the beloved works of dwellers on the land with storm and dust.Note 24

The resemblance of this victory to that of Indra, king of the Vedic pantheon, over the cosmic serpent Vṛtra is beyond question.Note 25 The two myths are variants of a single archetype. Furthermore, in each the role of the anti-god has been assigned to a figure from an earlier mythology — in Greece, of the Pelasgians, in India, of the Dravidians — daemons that formerly had symbolized the force of the cosmic order itself, the dark mystery of time, which licks up hero deeds like dust: the force of the never-dying serpent, sloughing lives like skins, which, pressing on, ever turning in its circle of eternal return, is to continue in this manner forever, as it has already cycled from all eternity, getting absolutely nowhere.

Against the symbol of this undying power the warrior principle of the great deed of the individual who matters flung its bolt, and for a period the old order of belief — as well as of civilization — fell apart. The empire of Minoan Crete disintegrated, just as in India the civilization of the Dravidian twin cities, Harappa and Mohenjo-daro. However, in India the old mythology of the serpent power presently recovered strength, until, by the middle of the first millennium b.c., it had absorbed the entire pantheon and spirit of the Vedic gods — Indra, Mitra, Vayu, and the rest — transforming all into mere agents of the processes of its own, still circling round of eternal return.Note 26 In the West, on the other hand, the principle of indeterminacy represented by the freely willing, historically effective hero not only gained but held the field, and has retained it to the present. Moreover, this victory of the principle of free will, together with its moral corollary of individual responsibility, establishes the first distinguishing characteristic of specifically Occidental myth: and here I mean to include not only the myths of Aryan Europe (the Greeks, Romans, Celts, and Germans), but also those of both the Semitic and Aryan peoples of the Levant (Semitic Akkadians, Babylonians, Phoenicians, Hebrews, and Arabs; Aryan Persians, Armenians, Phrygians, Thraco-Illyrians, and Slavs). For whether we think of the victories of Zeus and Apollo, Theseus, Perseus, Jason, and the rest, over the dragons of the Golden Age, or turn to that of Yahweh over Leviathan, the lesson is equally of a self-moving power greater than the force of any earthbound serpent destiny. All stand (to use Miss Harrison’s phrase) “first and foremost as a protest against the worship of Earth and the daimones of the fertility of Earth.”

“A worship of the powers of fertility which includes all plant and animal life is broad enough to be sound and healthy,” she adds, “but as man’s attention centers more and more on his own humanity, such a worship is an obvious source of danger and disease.”Note 27

Well, so it is! And yet, one cannot help feeling that there is something forced and finally unconvincing about all the manly moral attitudes of the shining righteous deedsmen, whether of the biblical or of the Greco-Roman schools; for, in revenge or compensation, the ultimate life, and therewith spiritual depth and interest, of the myths in which they figure continues to rest with the dark presences of the cursed yet gravid earth, which, though defeated and subdued, are with their powers never totally absorbed. A residue of mystery remains to them; and this, throughout the history of the West, has ever lurked within, and emanated from, the archaic symbols of the later, “higher” systems — as though speaking silently, to say, “But do you not hear the deeper song?”

In the legend of Medusa, for instance, though it is told from the point of view of the classic Olympian patriarchal system, the older message can be heard. The hair of Medusa, Queen of Gorgons, was of hissing serpents; the look of her eyes turned men to stone: Perseus slew her by device and escaped with her head in his wallet, which Athene then affixed to her shield. But from the Gorgon’s severed neck the winged steed Pegasus sprang forth, who had been begotten by the god Poseidon and now is hitched before the chariot of Zeus. And through the ministry of Athene, Asclepius, the god of healing, secured the blood from the veins of Medusa, both from her left side and from her right. With the former he slays, but with the latter he cures and brings back to life.

Thus in Medusa the same two powers coexisted as in the black goddess Kālī of India, who with her right hand bestows boons and in her left holds a raised sword. Kālī gives birth to all beings of the universe, yet her tongue is lolling long and red to lick up their living blood. She wears a necklace of skulls; her kilt is of severed arms and legs. She is Black Time, both the life and the death of all beings, the womb and tomb of the world: the primal, one and only, ultimate reality of nature, of whom the gods themselves are but the functioning agents.

Or let us take the curious legend of the blind sage Tiresias, to whom even Zeus and Hera turned once for a judgment. “I insist,” the king of the gods had playfully said to his spouse, “you women have more joy in making love than men do.” She denied it. And so they called upon Tiresias; for, in consequence of a strange adventure, he had experienced both sides of love.

“One day, while in the green wood,” as Ovid tells the tale,

Tiresias offended with a stroke of his stick two immense serpents, mating, and (O wonder!) was changed from man to woman. Thus he lived for seven years. In the eighth, he saw the same two again and said: “If in striking you there be such virtue that the doer of the deed is changed into his opposite, then I shall now strike once more”; which he did, and his former shape returned, so that again he had the gender of his birth.Note 28

When required to resolve the quarrel of the father of the gods and his queen, therefore, Tiresias knew the answer — and he took the part of Zeus. The goddess, in a pique, struck him blind; but the god, in compensation, bestowed on him the gift of prophecy.

In this tale the mating serpents, like those of the caduceus, are the sign of the world-generating force that plays through all pairs of opposites, male and female, birth and death. Into their mystery Tiresias blundered as he wandered in the green wood of the secrets of the ever-living goddess Earth. His impulsive stroke placed him between the two, like the middle staff (axis mundi) of Figure 1; and he was thereupon flashed to the other side for seven years — a week of years, a little life — the side of which he formerly had had no knowledge. Whence, with intent, he again touched the living symbol of the two that are in nature one, and, returning to his proper form, was thereafter the one who was in knowledge both: in wisdom greater than either Zeus, the god who was merely male, or his goddess, who was merely female.

The patriarchal point of view is distinguished from the earlier archaic view by its setting apart of all pairs-of-opposites — male and female, life and death, true and false, good and evil — as though they were absolutes in themselves and not merely aspects of the larger entity of life. This we may liken to a solar, as opposed to lunar, mythic view, since darkness flees from the sun as its opposite, but in the moon dark and light interact in the one sphere. The blinding of Tiresias was an effect, then, a communication to him of lunar wisdom. It was a blindness merely to the sunlight world, where all pairs of opposites appear to be distinct. And the gift of prophecy was the correlative vision of the inward eye, which penetrates the darkness of existence. Hence Tiresias comes like a visitant from the deepest subliminal stratum of the Greek heritage, to move as a mysterious presence among the characters of the upper, secondary sphere of those gods and myths of Olympus by which the other had been overcast — yet not entirely suppressed.

For have we not already seen the serpent Zeus Meilichios? And was it not in such a form that Zeus had intercourse with his daughter Persephone when the earth-goddess Demeter, of whom she had been born, left her in a cave in Crete, guarded by the two serpents normally harnessed to her chariot?

The reader recalls, perhaps, the Orphic legend cited in Primitive Mythology,Note 29 of how, while the maiden goddess sat there, peacefully weaving a mantle of wool on which there was to be a representation of the universe, her mother contrived that Zeus should learn of her presence; he approached in the form of an immense snake. And the virgin conceived the ever-dying, ever-living god of bread and wine, Dionysus, who was born and nurtured in that cave, tom to death as a babe, and resurrected.

Comparably, in the Christian legend, derived from the same archaic background, God the Holy Ghost in the form of a dove approached the Virgin Mary and she — through the ear — conceived God the Son, who was born in a cave, died and was resurrected, and is present hypostatically in the bread and wine of the Mass. For the dove, no less than the serpent, was an attribute and companion of the Great Goddess of the pre-Homeric, pre-Mosaic East. In Figure 11 she is seen as Aphrodite, surrounded by worshiping Erotes, holding a dove in her left hand.Note 30 Thus, in the world panorama of mythology, God the Father of the Christian Trinity, the father-creator of Mary, God the Holy Ghost, her spouse, and God the Son, her slain and resurrected child, reproduce for a later age the Orphic mystery of Zeus in the form of a serpent begetting on his own daughter Persephone his incarnate son Dionysus.

Figure 11. Aphrodite with Erotes

The victory of the patriarchal deities over the earlier matriarchal ones was not as decisive in the Greco-Roman sphere as in the myths of the Old Testament; for, as Jane Harrison has shown, the earlier gods survived, not only peripherally in such aberrant forms as Zeus Meilichios, but also in the rites of the popular field and women’s cults, and particularly in the mysteries of Demeter and the Orphics, whence numerous elements of the heritage were passed on to Christianity — most obviously in the myths and rites of the Virgin and the Mass. For in Greece the patriarchal gods did not exterminate, but married, the goddesses of the land, and these succeeded ultimately in regaining influence, whereas in biblical mythology all the goddesses were exterminated — or, at least, were supposed to have been.

However, as we read in every chapter of the books of Samuel and Kings, the old fertility cults continued to be honored throughout Israel, both by the people and by the majority of their rulers. And in the very text of the Pentateuch itself the signs remain, carried silently in symbols, of the wisdom of the old earth mother and her serpent spouse.

The Lord Yahweh said to the woman, “What is this that you have done?” The woman said, “The serpent beguiled me and I ate.” Yahweh said to the serpent, “Because you have done this, cursed are you above all cattle and above all beasts of the field. Upon your belly you shall go, and you shall eat dust all the days of your life. I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed; he shall bruise your head and you shall bruise his heel.”

Thus Yahweh cursed the woman to bring forth in pain and be subject to her spouse — which set the seal of the patriarchy on the new age. And he cursed, also, the man who had come to the tree and eaten of the fruit that she presented. “In the sweat of your face, you shall eat bread,” he said, “till you return to the ground; for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Genesis 3:13–19).

But the ground, the dust, out of which the punished couple had been taken, was, of course, the goddess Earth, deprived of her anthropomorphic features, yet retaining in her elemental aspect her function of furnishing the substance into which the new spouse, Yahweh, had breathed the breath of her children’s life. And they were to return to her, not to the father, in death. Out of her they had been taken, and to her they would return.

Like the Titans of the older faith, Adam and Eve were thus the children of the mother-goddess Earth. They had been one at first, as Adam; then split in two, as Adam and Eve. And the man, rebuked, replied to Yahweh’s challenge in a way entirely appropriate to his Titan character. “The man,” we read, “called his wife’s name Eve, because she was the mother of all living.” As the mother of all living, Eve herself, then, must be recognized as the missing anthropomorphic aspect of the mother-goddess. And Adam, therefore, must have been her son as well as spouse: for the legend of the rib is clearly a patriarchal inversion (giving precedence to the male) of the earlier myth of the hero born from the goddess Earth, who returns to her to be reborn. See again Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Moreover, as in the early Bronze Age seals of Ningizzida and his serpent porter, we have clear and adequate evidence throughout the biblical text that the Lord Yahweh was himself an aspect of the serpent power, and so himself properly the serpent spouse of the serpent goddess of the caduceus, Mother Earth. Let us recall, first, the magical serpent rod by which Moses was to frighten Pharaoh. Yahweh said to him, “What is that in your hand?” And Moses said, “A rod.” Yahweh said, “Cast it on the ground.” So he cast it on the ground and it became a serpent; and Moses fled from it. But Yahweh said to Moses, “Put out your hand and take it by the tail.” So he put out his hand and caught it, and it became a rod in his hand.Note 31 The same rod later produced water from the rock in the desert.Note 32 And when the people in the desert presently murmured against Yahweh, as we read:

Yahweh sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. … So Moses prayed for the people. And Yahweh said to Moses, “Make a fiery serpent, and set it on a pole; and every one who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.” So Moses made a bronze serpent, and set it on a pole; and if a serpent bit any man, he would look at the bronze serpent and live.Note 33

We are informed in II Kings that the people continued to revere this bronze serpent idol in Jerusalem until the time of King Hezekiah (719–691 b.c.), who, as we are told, “broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the people of Israel had burned incense to it: it was called Nehushtan.”Note 34 Shall we be astonished, then, to learn that the name of the priestly tribe of Levi, the chief protagonists of Yahweh, was derived from the same verbal root as the word Leviathan?Note 35 or that when pictures did at last appear of the unpicturable god, his form was of a god with serpent legs? (See Figure 25 and Figure 26)

III. Ultima Thule

We turn now to Ireland, where the magic of the goddess of the land of youth survives in fairy lore to this day. In the Middle Ages the mystic spell of her people of the fairy hills poured over Europe in the legends of the Table Round of King Arthur, where Gawain, Tristan, and Merlin brought the old Celtic Fianna and Knights of the Red Branch to life again in the armor of the Crusades. And a bit further back in time, in a period little studied, c. 375–950 a.d., the epic narratives themselves from which those heroes came were fashioned from mythic tales already old.

The first inhabitants of Ireland of whom trace remains arrived on its beaches during that obscure prehistoric time between the Old Stone Age and the New that is known as the mesolithic. The glaciers had retreated; but a chill, dank, misty air remained, through which gulls flew across gray-green waters whereon icebergs sailed like ships: and the life therein was of the seal, the walrus, and the whale. The great age of the paleolithic hunt was already of the long past, when the wonderful painted caves of southern France and northern Spain had been the chief religious sanctuaries of the world. There had been nothing in their time, anywhere on earth, to match or even to approach them: c. 30,000-15,000 b.c. But as the ice continued to retreat during the final stages of the Würm glaciation, there had ensued an irreversible deterioration of the conditions of the hunt. The semi-arctic tundra landscape, which had supported the woolly mammoth and rhinoceros, musk ox, and reindeer, gave way at first to grassy plain on which immense herds of bison, wild cattle, horses, and antelope ran; but then the plains gave way to forest, and the meat supply decreased dramatically. Many of the hunting folk followed their quarry northward, to become in time, as their province decreased in wealth, ancestors of those scattered hunting and fishing tribes that still populate thinly the farthest north. Others, however, remained to cull sustenance not only from the forest but also from the sea and shores. Already in the Magdalenian period, during the final prosperous millenniums, the fishing spear, fishhook, and harpoon had appeared among the weaponries of the chase, and the pursuit of the whale, the walrus, and the seal, in perilous coracles, had been developed — which has continued to the present among the last cultural inheritors, the Eskimos. But in the sequel both man’s zeal for life and the conditions of the European field so declined that the area became merely an outland of grubbing, residual forest folk.

The vital centers of cultural life had shifted south and to the southeast, where the grazing plains of North Africa and Southwest Asia, which today are largely desert, still supported mighty herds. A world of action flourished there that is vividly depicted in the rock paintings (not in caves now, but on the surfaces of cliffs) of the Capsian style of North Africa and southern Spain. The bow and arrow appear for the first time in this art, together with the dog as a companion of the hunt. And whereas the paintings of the earlier north had been primarily of beasts, those of this later Capsian art, c. 10,000-4000 b.c., were largely of human scenes, in a vigorously fluent narrative style. Moreover, the life depicted in these scenes was at first of hunters but then of herding tribes. For it was during the final stages of this terminal phase of the paleolithic that the arts of cattle-breeding and agriculture were developed in that Levantine part of its broad range that is known to historians today as the nuclear Near East.

Leo Frobenius was the first to use the terms West-East Pendulation and East-West Pendulation to represent the two successive trends of diffusion, respectively, of the paleolithic (hunting) and neolithic (agricultural) ages. “We can say,” he wrote in his inexhaustibly suggestive little book, Monumenta Terrarum,

that, by and large, the pendulation of the transfer of culture in prehistoric times proceeded in the paleolithic from a starting point in Western Europe, along the southern shore of the Mediterranean, eastward, across Egypt, to Asia. In the Old Stone Age, that is to say, the tide of culture moved from West to East, south of the regions formerly covered by the great glaciers. Then followed [in Europe] a cultural hiatus — until, presently, from eastward, there came the tide of a High Bronze Age, infinitely richer than anything before. This arrived both overland, through eastern Europe, and by sea, along the northern Mediterranean shores. From Asia Minor it came across the Aegean (Greek culture) to Italy (Rome); whence, faring westward still, it flowered in the Gothic (in France, Belgium, and Spain), culminating at its western extreme (in rationalistic England) with the preparation of the present age of world economy. In other words: separated from the earlier West-East Pendulation by a hiatus, a later East-West Pendulation brought the tide of the higher cultures.Note 36

And in a subsequent work on Africa Frobenius pressed the observation further.

Geographically as well as historically [he wrote], the Mediterranean Sea is divided by the land bridge of Italy and Sicily into a western and an eastern basin. Assigning to each of these the name of the large island in its midst, we may term them, respectively, the Sardinian Sea and the Cretan. The destiny of Northwest Africa has been determined, both from inward necessity and from without, by events in the regions around the Sardinian Sea, while the destiny of Levantine Africa has been shaped by those of the lands around the Cretan. … During the late paleolithic period the center of gravity of European culture was in the west: Spain during the Capsian period stood in close relationship to Northwest Africa, while in the greatly earlier Chellean age Northwest Africa and all of Western Europe constituted a single immense culture zone. — And now, in exactly the same way, the dependency can be noted of Levantine, Northeast Africa upon events around the Cretan Sea; so that, as the Sardinian to Western Europe, the Cretan Sea was related to Western Asia.Note 37

In sum, therefore: Throughout the almost endless period of the paleolithic hunt, Northwest Africa and Western Europe were a single immense culture province — the paleolithic fountainhead, as Frobenius termed it — whence a broad West-to-East pendulation carried the arts of Old Stone Age man to Asia; whereas in the later, much briefer period of rapid cultural transformation that we know as the neolithic or New Stone Age, Southwest Asia and Northeast Africa became the creative culture hearths, and the tide flowed back to Europe, East-to-West. Furthermore, whereas the earliest European mythological records of importance date from the paleolithic caves of c. 30,000-15,000 b.c., those of the Levant are of the neolithic age, c. 7500-3500 b.c. In the European spirit the structuring force lives on of the long building of its races to the activities of the hunt, and therewith the virtues of individual judgment and independent excellence; while, in contrast, in the younger, yet culturally far more complex, Near East the virtues of group living and submission to authority have been the ideals bred into the individual — who, in such a world, is actually no individual at all, in the European sense, but the constituent of a group. And, as we are to see, throughout the troubled history of the interplay of these two culture worlds in their alternating pendulations, the irresoluble conflict of the principles of the paleolithic individual and the neolithic sanctified group has created and maintained even to the present day a situation of both creative reciprocity and mutual disdain.

But to return to Ireland.

IV. Mother Right

The particular force and character of the contributions of Ireland to the early development of the West derived from the fact that, although throughout the paleolithic period the island had been uninhabited, at the very start of the West European Age of Bronze, c. 2500 b.c., it became suddenly — and for good reason — one of the most productive fountainheads of the Occidental scene. Britain during paleolithic times had been of a piece with the mainland, but Ireland, not. Hence, it was only when the dangerous, late paleolithic adventure of the sea hunt of the walrus, seal, and whale developed that the island could be reached at all. But even then no permanent settlement was achieved.

The only remains from that remote time are those already mentioned, of the Mesolithic age. They were discovered along the northeast Antrim coast, on “raised beaches” (now some twenty-five feet above the sea), notably at Larne, Kilroot, and Portrush, and on Island Magee. And what is already strange is the fact that, whereas the artifacts of the first three sites exhibit affinities with the Mesolithic cultures of the Baltic and North Seas, those of Island Magee, which is within sight of Larne, are linked rather with the industries of northern Spain. These contrary associations were to continue to contribute to the destiny of the island. However, the early Mesolithic visitors were not themselves in any sense the founders of that destiny. Who they were, what brought them to Ireland, when, or how — or why they disappeared — we do not know. In the words of Professor R. A. S. Macalister, of University College, Dublin, for many years President of the Royal Irish Academy and of the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland, “their memorial has perished with them. Their lives, their loves, their hates, their speech, their manners, customs, and scheme of society, their deaths, their gods, all have faded as in a dream.”Note 38 The dating of their ephemeral settlements can be reckoned only vaguely, as somewhere — anywhere — between the end of the glacial ages in the north, c. 7800 b.c., and the appearance, c. 2500 b.c., of the earliest Copper and Bronze Age remains, with which the high history not of Ireland alone, but of the entire northwest of Europe, properly begins.

The motive force of this sudden Bronze Age development is to be seen in what Professor Macalister has termed the chief “impulsive,” as distinct from “expulsive,” cause of the colonization of a land so difficult of access. “There are,” he states, “impulsive as well as expulsive reasons for colonization. Expulsive causes arc those which make the original home temporarily or permanently uninhabitable — the pressure of an inrush of enemies, of adverse climatic conditions, or what not. Impulsive causes are those which make the new home attractive; and undoubtedly gold, of which Ireland was understood to possess great stores, was the chief attraction which the country offered to invaders or to settlers.”Note 39 Gold lay twinkling in the beds of the rivers, much as in the days of panning gold in our own American Wild West. “The large collection of gold ornaments in the National Museum,” Professor Macalister continues, “shows that the gold of the river-gravels was industriously collected: in fact, the Bronze Age goldsmiths seem to have exhausted the supply.”Note 40 Stores of copper, too, were to be found in many parts of the island, and this was a metal likewise of incalculable value. Tin, however, the other ingredient of bronze, was not at first available, the nearest resource being in neighboring British Cornwall. But this was presently discovered and mined by the Irish. So that even in the period of the flowering of Babylon, Middle Kingdom Egypt, Troy, and Minoan Crete, there was a remote secondary hearth, beyond the wilderness of the farthest northwest, from which flowed an export of lunate ornaments of gold, a particular type of flat copper ax and, later, when the tin had been discovered, a characteristic bronze halberd.

But the point of particular interest for the student of mythology, and of continuing force for the importance of Ireland in all the later developments of European mythic and legendary lore, is that the period of this foundation of the culture style of the island was intermediate in time between the twilight of the great European paleolithic ages and dawn of the still greater patriarchal ages of the Aryan Celts, Romans, and Germans. The culture was of a radically different order from either of the two between which it arose. Nor was its period brief, for it endured from c. 2500 to as late as c. 500-200 b.c., when the first of the iron-bearing Celtic tribes arrived, of whose religious lore the druids were the masters. Its order of mythology and morality was of the Bronze Age, of the mother-goddess and Mother Right, and its relationship to the later, patriarchal, Celtic system was about the same as that of the early Creto-Aegean to the classic Olympian of Greece.

In fact, even in the late Celtic legends many startling traits are revealed of brazen dames who preserved the customs of that age up to early Christian times. They were in no sense wives in the patriarchal style. For even at the height of the Celtic heroic age, c. 200 b.c. to c. 450 a.d., many of the most noted Irish noblewomen still were of pre-Celtic stock; and these bore themselves in the imperious manner of the matriarchs of yore.

There is, for example, the episode of the pillow colloquy of Queen Meave of Connaught with her Celtic spouse, Ailill of Leinster, in the bizarre epic known as “The Cattle Raid of Cooley.”

The couple were at peace in their fort of Cruachan, having just spread the royal couch, when “Woman,” said Ailill, “it is true indeed, the saying that a good man’s wife is good.” She replied, “Yes; but of what relevance to you?” He answered, “Because you are a better woman now than you were the day I married you.” She said, “I was good before ever I saw you.” “Curious, then,” he responded, “that we never heard anything of the kind, but only that you placed trust in your woman’s wiles, whereas the enemies on your borders were freely plundering you of your plunder and your prey.”

And then it was that Meave gave the retort of a true queen matriarch, no bartered bride of any man, but the mistress of her own realm — and of the king himself, besides, with all the rights reserved to herself that in the patriarchy belong to males:

“I was not as you declare, [she told him,] but I dwelt with my father Eochaid, King of Ireland, who had six daughters, and the noblest and most worshiped of us all was I. For as regards largess, I was the best; and as regards battle, strife, and combat, again I was the best. I had before and around me twice fifteen hundred royal mercenaries, all chieftains’ sons; with ten men for each, and for each of these, eight men; for each of these, seven; for each of these, six; for each of these, five; for each of these, four; for each of these, three; for each of these, two; and for each of these, one. These I had to my standing household; for which reason, my father gave me one of his provinces of Ireland; namely this of Cruachan, wherein we are now; whence I am known by the designation, Meave of Cruachan.”

That Queen Meave was a mistress not only of her own castle but also of the Irish art of poetic magnification appears from the fact, as Professor Macalister has pointed out, that the retinue here specified amounts to 40,478,703,000 persons, “or rather more than three times the whole population of modern Dublin crowded upon every single square mile of Ireland.”Note 41 Having made this point, the Queen continued.

“Thereupon, [she said to her spouse,] there came an embassage to sue for me from Finn mac Rosa Rua, King of Leinster; another from Cairpre Niafer mac Rosa, King of Tara; one from the King of Ulidia, Conachar mac Fachtna; and yet another from Eochu Beg. But I rejected them; for I was she that required a strange bride gift, such as no woman had ever demanded from any man of the men of Erin; namely that my husband should be a man not the least niggardly, without jealousy, and without fear.

“For should the man that I had be niggardly, that were not well, since I should outdo him in liberality. And were he timorous, that were not well, since I alone should have the victory in battles, contests, and affrays. And were he jealous, neither would that be well; for I have never been without one man in the shadow of another. And I have gotten myself, indeed, just such a husband, namely yourself: Ailill mac Rosa Rua of Leinster. For you are not niggardly, jealous, or a coward. Moreover, I presented you with wedding gifts of such worth as become a woman; to wit, cloth for the raiment of twelve men, a battle car of the value of three times seven slave girls, your face’s width of ruddy gold, and white bronze to the weight of your left forearm. So that if anyone should disparage, maim, or cheat you, there is no insurance or compensation for your damaged honor, but what is mine: for a petticoat pensioner is what you are.”Note 42

One of the foremost of the generation of pioneer Celtic scholars of the late nineteenth century, Professor H. Zimmer, Senior (not to be confused with his son of the same name, the distinguished Indologist, whom I have cited in Oriental Mythology; to prevent confusion, I designate the elder as H. Zimmer and the younger as Heinrich Zimmer), points out in his discussion of this tirade of Queen Meave, that, among the Celts of the British Isles, a bride was “compensated for her violated honor” by a “morning gift” from her husband,Note 43 and that for a king the compensation for violated honor was “a platter of gold as broad as his face” — which would have been caused to redden for shame.Note 44 Consequently, the sharp point of Meave’s final thrust resided — as Dr. Zimmer observes — in its “complete reversal of the conditions that prevail under an uncorrupted system of Father Right.”

Meave [he writes further] takes to herself a spouse, not at all as under the patriarchy a maiden accepts her husband; and he is not a mere good for nothing either … but a king’s son, a brother of kings, whose possessions are not, in fact, inferior to her own. She counts out the stipulated marriage donation; bestows on him the morning gift as Pretium virginitatis; and just as the man under the patriarchy reserves to himself the right to take concubines, so does Meave claim as her right, and as condition to her marriage contract, “House-friends”: one man in the shadow of another. What her words represent is not an exaggeration uttered in the heat of argument, but a proclamation of the ground rules, openly understood on her part, tacitly recognized by Ailill, and clearly illustrated in her actsNote 45

— as we are now to see.

For when Ailill had been thus abused, he called for a comparative count of properties, and before the eyes of the two there were paraded, first, their mugs and vats, iron vessels, urns, brewers’ troughs and chests; rings and bangles, various clasped ornaments, thumb-rings and apparel, as well crimson, blue, black, and green, as yellow, checkered, and buff, pale-colored, pied, and striped. Then all their numerous flocks of sheep were driven in from the greens, lawns, and open country, found to be in number equal, and dismissed: likewise their steeds; likewise their herds of grunting swine. However, when the cattle lumbered past, it was noticed that, though they were in multitude the same, there was among those of the king a certain bull named The White-horned, which had been a calf among Meave’s cows but, not desiring to be governed by a woman, had departed and taken his place among the cattle of the king. His match for size and majesty could not be discovered among the master bulls of her lot, and when this inequality came to light the queen felt as though she did not possess a pebble’s worth of stock.

Queen Meave inquired of her herald, Mac Roth, whether in any province of Ireland there was a bull of worth equivalent to The White-horned; and “Why, indeed!” he answered; “a fellow in double measure better and more excellent I know; namely, of Daire mac Fachtna’s herd in Cooley, which is known as The Brown of Cooley.”

“Be off,” then ordered Meave; “and of Daire crave for me one year’s loan of that bull; at the end of which year the loan fee to be paid to him shall be, besides The Brown of Cooley himself, fifty heifers; and if any of that country should think ill of giving up even for a time that extraordinarily precious thing, well, then let Daire come along with his bull and I shall settle on him an estate of a size equal to that of his present land, besides a chariot of the value of three times seven slave girls, and he shall have, in addition, the friendship of my own upper thighs.”

An embassy of nine, therefore, with Mac Roth crossed the island from Connaught in the west to Cooley in the northeast, and when Daire was told that if he arrived with the bull he would have an estate of a size equal to his own now in Cooley, besides a chariot worth twenty-one slave girls, and the friendship, moreover, of Meave’s own upper thighs, “he was so well pleased,” we read, “that he threw himself in such wise that the seams of the mattresses beneath him burst asunder.”Note 46

The rest of the tale can wait; for the only point to be made now is that both the archaeology and the ancient literature of Ireland demonstrate that the patriarchal, iron-bearing Celts, who gained the mastery during the last three or four centuries b.c., overcame but did not extinguish an earlier, Bronze Age civilization of Mother Right. The circumstance resembled that of the overthrow by the iron-bearing Dorian Greeks of the Bronze Age order of the Cretan-Aegean world — the myths and rites of which, however, lingered on. And as the work of Miss Harrison, already cited, has disclosed, not only were many of the best-known Homeric myths actually fragments of pre-Homeric mythology reinterpreted, but also in the field festivals, women’s rites, and mystery cults of the Classic world there survived beneath (and even not far beneath) the sunny Olympian surfaces a dark, and to us even appalling, stratum of archaic ritual and custom. Comparably, in the epics of ancient Ireland, the Celtic warrior kings and their brilliant chariot fighters move in a landscape beset with invisible fairy forts, wherein abide a race of beings of an earlier mythological age: the wonderful Tuatha De Danann, children of the Goddess Dana, who retired, when defeated, into wizard hills of glass. And these are the very people of the sídhe or Shee, the Fairy Host, the Fairy Cavalcade, of the Irish peasantry to this day.

“Who are they?” asks the poet Yeats. And he gives a trilogy of answers: “‘Fallen angels who were not good enough to be saved, nor bad enough to be lost,’ say the peasantry. ‘The gods of the earth,’ says the Book of Armagh. ‘The gods of pagan Ireland,’ say the antiquarians, ‘the Tuatha De Danān, who, when no longer worshiped and fed with offerings, dwindled away in the popular imagination, and now are only a few spans high.’ ” But he adds: “Do not think the fairies are always little. Everything is capricious about them, even their size.”Note 47