Chapter 9 — EUROPE RESURGENT

I. The Isle of Saints

When Ireland then had first and vaguely heard Christ’s name the disposition of Christian devotion had its first origin in Kieran; his parents and every other one marveling at the extent to which all his deeds were virtuous. Before she conceived Kieran in her womb his mother had a dream: as it were a star fell into her mouth; which dream she related to the magicians and to the knowledgeable ones of the time, and they said to her: “Thou wilt bear a son whose fame and whose virtues shall to the world’s latter end be great.” Afterward that holy son Kieran was born; and where he was brought forth and nursed was on the island which is called Clare. Verily God chose him in his mother’s womb. He was mild in his nature, and of converse sweet; his qualities were attended with prosperity, his counsel was instruction, and so with all else that appertained to a saintly man.

One day that he was in Clare there it was that, he being at the time but a young child, he made a beginning, of his miracles; for in the air right over him a kite came soaring and, swooping down before his face, lifted a little bird that sat upon her nest. Compassion for the little bird took Kieran, and he deemed it an ill thing to see it in such plight; thereupon the kite turned back and in front of Kieran deposited the bird half dead, sore hurt; but Kieran bade it rise and be whole. The bird arose, and by God’s favor went whole upon its nest again.

A score and ten years now before ever he was baptised Kieran spent in Ireland in sanctity and in perfection both of body and of soul, the Irish being in that time all non-Christians. But the Holy Spirit being come to dwell in His servant, in Kieran, he for that length lived in devotion and in perfect ways; then he heard a report that the Christian piety was in Rome and, leaving Ireland, went thither, where he was instructed in the Catholic faith. For twenty years he was there: reading the Holy Scripture, collecting his books and learning the rule of the Church; so that when the Roman people saw our Kieran’s wisdom and cunning, his devotion and his faith, he was ordained into the Church. Afterwards he reached Ireland again; but upon the way from Italy Patrick had met him, and when they (God’s people) saw each other they made much rejoicing and had great gladness.

Now at that time Patrick was not a bishop, but was made one later on. Pope Celestinus [422–432] (Compare, The Cross and the Crescent) it was that made a bishop of him and then sent him to preach to the Irish; for albeit before Patrick there were saints in Ireland, yet for him God reserved her magistracy and primacy until he came; nor till his advent did their kings or their lords believe by any other’s means.

Said Patrick to Kieran: “Precede me into Ireland; and in the meeting of her northern with her southern part, in her central point, thou shalt find a well. At such well (the name of which is Uaran) build thou a monastery; there shall thine honor abide for ever and thy resurrection be.”

Kieran answered and said: “Impart to me the spot where the well is.”

Patrick said to him: “The Lord will be with thee: go thou but straight before thee; take to thee first my little bell, which until thou reach the well that we have mentioned shall be speechless; but when thou attainest to it the little bell will with a clear melodious voice speak out: so shalt thou know the well, and at the end of nine years and a score I will follow thee to that place.”

They blessed and kissed each other, and Kieran went his way to Ireland; but Patrick tarried in Italy. Kieran’s bell was without uttering until he came to the place where was the well of which Patrick spoke: Uaran namely; for when Kieran was come into Ireland God guided him to that well, which when he had reached, straightway the little bell spoke with a bright clear voice: barcán Ciárdin ’tis called, and for a token is now in Kieran’s parish and in his see. …

And touching that well of which we have spoken: the very spot in which it is is in the mearing betwixt two parts of Ireland, Munster being the southernmost part and Ulster the northern; howbeit in Munster actually the country is which men call Ely. In that place Kieran began to dwell as a hermit (for at that time it was all encircled with vast woods) and for a commencement went about to build a little cell of flimsy workmanship (there it was that later he founded a monastery and metropolis which all in general now call Saighir Chiaráin).

When first Kieran came hither he sat him down under a tree’s shade; but from the other side of the trunk rose a wild boar of great fury which, when he saw Kieran, fled and then turned again as a tame servitor to him, he being by God rendered gentle. Which boar was the first monk that Kieran had there; and moreover went to the wood to pull wattles and thatch with his teeth by way of helping on the cell (human being there was none at that time with Kieran, for it was alone and away from his disciples that he came on that eremite-ship). And out of every quarter in which they were of the wilderness irrational animals came to Kieran: a fox, namely, a brock, a wolf, and a doe; which were tame to him, and as monks humbled themselves to his teaching and did all that he enjoined them.

But of a day that the fox (which was gross of appetite, crafty, and full of malice) came to Kieran’s brogues he e’en stole them and, shunning the community, made for his own cave of old and there lusted to have devoured the brogues. Which thing being shown to Kieran he sent another monk of the monks of his familia (the brock to wit) to fetch the fox and to bring him to the same spot where all were. To the fox’s earth the brock went accordingly, and caught him in the very act to eat the brogues themselves (their lugs and thongs he had consumed already). The brock was instant on him that he should come with him to the monastery; at eventide they reached Kieran, and the brogues with them. Kieran said to the fox: “Brother, wherefore hast thou done this thievery which was not becoming for a monk to perpetrate? seeing thou needest not to have committed any such; for we have in common water that is void of all offence, meat too we have of the same. But and if thy nature constrained thee to deem it for thy benefit that thou shouldst eat flesh, out of the very bark that is on these trees round about thee God would have made such for thee.” Of Kieran then the fox besought remission of his sins and that he would lay on him a penance; so it was done, nor till he had leave of Kieran did the fox eat meat; and from that time forth he was righteous as were all the rest.*Note 1

The coming of Patrick to Ireland is traditionally set at 432 a.d.; but the date is suspect, and particularly so since when multiplied by 60 (the old Sumerian sexagesimal soss) it yields the number 25,920, which is precisely the sum of years of a so-called “Great” or “Platonic year,” i.e., the sum of years required for the precession of equinoxes to complete one cycle of the zodiac. I have discussed this interesting figure in Oriental Mythology,Note 3 where it appeared that in the Germanic deity Odin’s warrior hall there were 540 doors through each of which 800 warriors fared to the “war with the Wolf” at the end of the cosmic eon. 540 × 800 = 432,000, which is the sum of years ascribed, also, in India to the cosmic eon. The earliest appearance of this number in such an association, however, was in the writings of the Babylonian priest Berossos, c. 280 b.c., where it was declared that between the legendary date of the “descent of kingship” to the cities of Sumer and the date of the mythical deluge, ten kings reigned for 432,000 years. I have remarked that in Genesis, between the creation of Adam and the time of Noah’s deluge, there were ten Patriarchs and a span of 1656 years. But in 1656 years there are 86,400 seven-day (i.e., Hellenistic-Hebrew) weeks, while if the Babylonian years be reckoned as days, 432,000 days constitute 86,400 five-day (i.e. Sumero-Babylonian) weeks. And, finally, 86,400 ÷ 2 = 43,200: all of which points to a long-standing relationship of the number 432 to the idea of the renewal of the eon; and such a renewal, from the pagan to the Christian eon is exactly what the date of Patrick’s arrival in Ireland represents.

Patrick’s actual life span seems to have been c. 389–461 a.d.,* and we note that Pope Celestine I, by whom he is supposed to have been appointed, did in fact die in the year 432. Thus the period of Patrick’s life was that of, on the one hand, the end of Classical paganism at the hands of Theodosius I (r. 379–395) and, on the other hand, the breakthrough of the German tribes and the fall to them of much of Europe. Ireland, however, was not invaded at this time, so that there a distant colony of Christ remained intact, cut off from Rome, while England and the Continent fell prey to contending Germanic tribes.

Now Patrick’s life was, of course, ornamented with miracles. “Just born,” we read in an Old Irish version of his biography,

he was brought to be baptized to the blind flat-faced boy named Gomias; but Gomias had no water wherewith to perform the baptism. So with the infant’s hand he made the sign of the cross over the earth, and a wellspring of water broke forth therefrom. Gomias put the water on his own face and it healed him at once, and he understood the letters of the alphabet though he had never seen them before. So that here, at one time, God wrought a threefold miracle for Patrick, the well-spring of water out of the earth, his eyesight to the blind youth, and skill in reading aloud the order of baptism without knowing the letters beforehand. Thereafter Patrick was baptized.Note 4

When Patrick fared as primate to Ireland, twenty-four men were of his number, and he found a light sailing craft in readiness before him on the strand of the sea of Britain.

But when he had come into the boat, a leper asked him for a place and there was no empty place therein. So he put out before him to swim in the sea the portable stone altar whereon he used to make offering every day. Sed tamen, God wrought a great miracle here, to wit, the stone went not to the bottom, nor did it stay behind them; but it swam round about the boat with the leper on it until it arrived in Ireland.

Then Patrick saw a dense ring of demons around Ireland, to wit, a six days journey from it on every side.Note 5

Now the fierce heathen High King of Ireland in those days was Laeghaire (Leary) son of Niall (r. 428–463), and it came to pass that when Patrick had been for some time there, preaching, he brought his ship, one Easter Eve, into the estuary of the Boyne. There was just then a feast in progress at the royal residence in Tara, during the period of which no fire was permitted to be lighted. Nevertheless, Patrick left his vessel and went along the land to Slane, where he pitched his tent and kindled a Paschal fire that lighted up the whole of Mag Breg; and the folk at Tara saw that fire from afar.

The king said: “That is a breach of the ban of our law; go find out who has done that.” And his wizards said: “We too have remarked the fire. Furthermore, we know that unless it be quenched on the night on which it has been made, it will not be quenched till doomsday; and he who kindled it, moreover, unless he be forbidden, will have the kingdom of Ireland forever.”

The king, hearing that, was mightily disturbed; and he said: “That must not be. We shall go and kill him.” His chariots and horses were yoked, and he and his men, at the end of the night, proceeded toward the fire.

Said his wizards: “Go not thou to him, lest it be a token to him of honor; but let him come to thee, and let none rise up before him: and we shall argue in thy presence.” Thus, therefore, it was done. And when Patrick saw the chariots and horses being unyoked, he chanted: “Some in chariots, some in horses trust, but we in the name of the Lord our mighty God.”

They were all sitting before him with the rims of their shields against their chins, and none rose up, save only one, in whom there was a nature from God; namely Ere, later Bishop Ere, who is venerated at Slane. Patrick bestowed a blessing upon him, and he believed in God, confessed the Catholic Faith, and was baptized. Patrick said to him: “Thy city on earth will be high, will be noble.”

Patrick and Laeghaire then asked tidings, each of the other; and one of the wizards, Lochru to wit, went angrily and noisily, with contention and questions against Patrick, and went astray into blaspheming the Trinity. Patrick thereupon looked upon him wrathfully and called with a great voice unto God, and he cried: “Lord, who canst do all things, and on whose power dependeth all that exists, and who hast sent us hither to preach Thy name to the heathen: let this ungodly man, who blasphemeth Thy name, be lifted up, and be destroyed in the presence of all.”

Swifter than speech, at Patrick’s word, demons uplifted the wizard in the air, and they let him down against the ground; his head struck a stone on which his brains were scattered and dust and ashes were made of him before all. And the heathen hosts that were biding there were adread.

King Laeghaire thereupon was greatly enraged at Patrick and desired at once to kill him. He said to those about him: “Slay the cleric!” And when Patrick perceived the onfall of heathen upon him, he exclaimed again with a great voice: “Let God arise, and let his enemies be dispersed: let these that hate him flee before him. As smoke vanishes, so let them. And as wax melts at a fire, so let the ungodly before God!” Immediately darkness came over the sun, a great earthquake and trembling of arms took place: it seemed the sky dropped on the earth; horses fled in fright and the wind whirled the chariots through the fields. And all in the assembly turned against each other, so that each was after slaying the other, and there were left along with the king but four persons only in that place, to wit, himself, his queen, and two of his wizard priests.

And the queen, namely, Angas, daughter of Tassach, son of Liathan, came in terror to Patrick. She said to him: “O just and mighty man, do not destroy the king. He shall come to thee and do thy will and kneel and believe in God.” So Laeghaire went and knelt to Patrick, and pledged to him a false peace; some little time after which, he said to him: “Come, O cleric, follow me to Tara, that I may recognize thee in the presence of the men of Ireland.” And he had set an ambush on every path.

Yet Patrick and his company of eight, along with his gillie (his boy servant) Benen, went together past all these ambushes in the form of eight deer and, behind them, one fawn with a white bird on its shoulder: that is, Benen with Patrick’s writing tablets on his back.Note 6

The most famous deed of the conversion was Patrick’s confrontation on the hillock at Mag Slecht of the large stone image known as Cenn or Cromm Cruach, the “Head” or “Crooked One of the Mound,” which was surrounded by twelve smaller idols, all of stone. It has been said that at Halloween (Samhain) the Irish offered a third of their children to this god — who was probably an aspect of that Dagda of the Tuatha De Danann, whose caldron never lacked food, whose trees were always laden with fruit, and whose swine (one living, one always ready for the cooking) were the inexhaustible banquet of the ever-living ones of his sidhe (For the Dagda, compare Great Rome: c. 500 b.c.–c. a.d.). The legend of Patrick tells that he went by water to Mag Slecht, where there was that chief idol of Ireland covered with gold and silver, and the other twelve around it covered with brass. And when he saw that thing from the water and drew nigh to it, he raised up his hand to put his staff upon it and, though his staff was not long enough, nevertheless it smote its side. The mark of the staff still remains on its left side, yet the staff did not move out of Patrick’s hand. And the earth swallowed up the other twelve as far as to their heads, where they still stand in token of the miracle. He cursed the demon and expelled him into hell; then founded a church in that stead, namely Domnach Maige Slecht, where he left Mabran, who was his relative and a prophet. And there, too, is Patrick’s well, wherein many were baptized.Note 7

However, the most important aspect of the Christianization of Ireland for our study is not the conflict but the ultimate accord that was reached between the older mysteries of the fairy forts and the new of the Roman Catholic Church. The magic of King Laeghaire’s wizards was surpassed by that of Patrick’s mighty God, and the island, even in the lifetime of the saint, was turned to Christ, with all the necessary machinery of cloisters, churches, relics, and the voice of bells. However, a culture historian today surely has a right to ask the meaning of such a mass conversion as takes place when a pagan king submits to baptism and all his people follow. And the question is compounded when the doctrines of the new religion are still in the process of being hammered out in conventions held two thousand miles away.

We have already had occasion to remark the heresy of the Donatists, combated, first by the monarch Constantine (r. 324–337), and then by Saint Patrick’s North African contemporary, Saint Augustine (354–430) (See Great Rome c. 500 b.c.–c. 500 a.d. here and here). The argument turned on the question as to whether a sacrament depends for its validity on the spiritual state of the human being who administers it, and the orthodox reply was that it did not: the Church (in the words of Augustine’s predecessor, Optatus of Mileum) is an institution “whose sanctity is derived from the sacraments, and not estimated from the pride of persons. … The sacraments are holy in themselves and not through men.”Note 8 So much for the doctrine! What, however, of the Celtic natives who received it? Surely it is permissible (indeed, in a work such as this, necessary) to ask: How, exactly, was this Levantine institution with its supporting myth received and understood by the recently pagan, hyperborean population, to whose well-being in the yonder world its magic now was to be applied?

One important clue to the temper of the north may be seen in the heresy of two Irishmen, contemporaries of Patrick, Pelagius and his chief disciple Caelestius. In their essentially Stoic doctrine of free will and the innate goodness of nature, which is not corrupted but only modified by sin, they opposed diametrically their great antagonist Augustine, for whom (as for the Church), nature, though created good, was so corrupted by the sin of Adam that virtue is impossible without grace: grace proceeds only from the sacraments by virtue of Jesus Christ: without grace, man’s free will can will only vice, and therewith hell: and, consequently, man (fallen man) cannot redeem himself but is rendered virtuous only by that incorruptible Levantine dispensary which Augustine had already manfully defended against the Donatists. Man’s sins, that is to say, could not corrupt the Church, nor man’s merely human virtues restore man. Against what Pelagius decried as the Manichaeism of his North African adversary, the Irish heretics proclaimed the following six doctrines, for which they were formally condemned:

- That Adam would have died even if he had not sinned;

- That the sin of Adam injured himself alone, not the human race;

- That newborn children are in the same condition in which Adam was before the Fall; corollary: that infants, though unbaptized, have eternal life;

- That the whole human race does not die because of Adam’s death or sin, nor will it rise again because of Christ’s resurrection;

- That the Old Testament Law, as well as the New Testament Gospel, gives entrance to heaven; and

- That even before the coming of Christ there were men who were entirely without sin.

According to this heresy, it follows from the goodness and righteousness of God that everything created by him is good. Human nature is indestructibly good and can be modified only accidentally. Sin, which consists in actively willing to do what righteousness forbids, is such a modification: it is always a momentary self-determination of the will and can never pass into nature so as to give rise to an evil nature. But if this cannot happen, so much the less can evil be inherited. Moreover, the will, which is thus uncorrupted, is always of itself capable of willing good. And Christ works by his example, the sacraments functioning not as power but as teaching. All of which adds up, in sum, to a variant of the Oriental and Stoic doctrine of self-reliance (Japanese, jiriki: “own strength”) (See The Masks of God: Oriental Mythology, and Hellenism 331 b.c.–324 a.d.), or in Pelagian phrase: homo libero arbitrio emancipatus a deo: man, created free, is with his whole sphere independent of God and of the Church, the Living Body of Christ — though Christ, Church, and sacraments mightily teach and help.Note 9

A second clue to the temper of the north may be seen in the Irish Neoplatonic philosopher — “the most learned and perhaps also the wisest man of his age,” Professor Adolph Harnack has termed himNote 10 — Johannes Scotus Erigena (c. 815–c. 877 a.d.), who, when he was about thirty-two years of age, was invited by Charles the Bald to France to conduct the Carolingean court school. His basic work, De divisione naturae (c. 865–870), views nature as a manifestation of God, in four aspects, which are not forms of God but forms of our thought. These are, namely: I. The Uncreated Creating, II. The Created Creating, III. The Created Uncreating, and IV. The Uncreated Uncreating. The first is God conceived as the source of all things. The second is nature in the aspect of those immutable divine acts of will, primordial ideas or archetypes, that are the Forms of forms. The next is nature in the aspect of individual things, or forms, in time and space. And the fourth is God conceived as the final end of all things. No student of Schopenhauer will have the least difficulty here. It is impossible to know God as he is. The same predicate may rightly be both affirmed and denied of God: however, the affirmation (e.g., God is Good) is only metaphorical, whereas the denial is literal (God is not Good), since God is beyond all predicates, categories, and oppositions (Compare Introduction) Moreover, God does not know what he is, since he is not a what: this “divine ignorance” surpasses all knowledge, and true theology, therefore, must be negative. Nor does God know evil; if he knew it, evil would exist, whereas evil is an effect merely of our own misknowledge (the Created Uncreating). All apparent differences in time and space, of quality and quantity, of birth and death, male and female, etc., are effects of this misknowledge. All that God creates, on the other hand, is immortal; and the incorruptible body, which is our God-created Form, is hidden, as it were, in the secret recesses of our nature, and will reappear when this mortality is put away from our mind. Sin is the misdirected will and is punished by the finding that its misjudgments are vain. Hell is but the inner state of a sinning will. And the Paradise and Fall of Genesis, consequently, are allegorical of states of mind, not to be understood as episodes in the prehistoric past. Correction of the mind is facilitated by philosophy (reason) and religion (authority), but the criterion of the latter is the former, not vice versa. It follows that the Living Body of Christ is not the Church but the world; for God is in all things, and all things, therefore, both are and are not.

Needless to say, Erigena’s Neoplatonic philosophy was condemned by Rome; and there is, furthermore, a possibly true story (not unlikely of a great teacher) of his students’ having stabbed him to death with their pens.Note 11

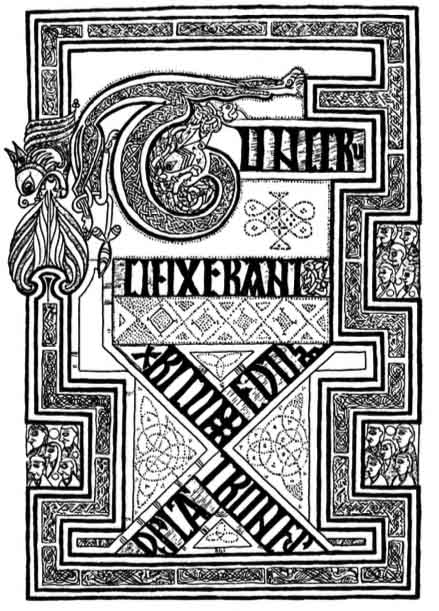

As a final clue to the manner of thought of the minds of the north, let me call attention to the curious illuminations of the Irish Book of Kells, which are of the period of Scotus Erigena (Following Sir Edward Sullivan, The Book of Kells (London: The Studio, Limited, 4th edition, 1933), p. vii: “the latter end of the ninth century.”) and of which I reproduce in Figure 30 (The figure has been very kindly drawn for me by Mr. John Mackey, from Sullivan, op. cit., plate XI.) the so-called Tunc-page, bearing the words of the Gospel according to Matthew: “Then there were crucified with him two thieves” (Tunc cru/cifixerant/xpi cum eo du/os la/trones).Note 12

Figure 30. “Then There Were Crucified with Him Two Thieves”

We recognize the cosmic self-consuming, self-renewing serpent, whose lion-head recalls the old Sumerian lion-bird, while the T of the word Tunc is a lion with serpentine attributes, either swallowing or emitting (or both) a tangled pair-of-opposites. The serpent, as we have learned, is generally symbolic of both the self-consuming and self-renewing powers of life; that is to say, the lunar mystery of time, while the lion is the solar power, the sun door to eternity. The circumscribing serpent, therefore, is the demiurgic, world-creating and -maintaining principle, or, in the Gnostic-Christian view, the God of the Old Testament, while the lion of the T is the road of escape from this vale of tears: the “way and the light,” that is to say the Redeemer.

The Greek letters XPI, inserted in the text after crucifixerant, are the signa of Christ (Greek χριστός). The same three letters furnish the base of the whole design, as appears when the page is turned clockwise, to lie on its right side. In this position, the great initial unites with the central bar to form P: the middle letter of the sign, symbolizing the Savior between the two thieves, which latter now are represented by the X and I, and are thus one with — indeed parts of — XPI, or Christ. Compare the Dadophors of the Mithra sacrifice, discussed above.

Moreover, on the fifteenth day of each lunar month, the setting full moon (lunar bull: sacrifice) confronts the blaze of the rising sun (Mithra Tauroctonus), which strikes it directly across the plane of the earth, and the moon thereafter wanes. We note in the border formed by the serpent’s body three groups of five men, which is to say, fifteen. Easter is now celebrated the first Sunday after the full moon on or following the vernal equinox; and, according to the reckoning of the Synoptic Gospels, the crucifixion took place on the fifteenth day of the Jewish month of Nisan (March-April: first month of the Jewish year). It looks as though a reference to this lunar theme of death and resurrection were intended here. Furthermore, it may be relevant to remark that the letter T is one of the forms and symbols of the cross, the cross being a traditional sign, moreover, of the earth, or principle of space, while the word Tunc, of which T is the initial, meaning “then,” is a word of time: spacetime being the field of phenomenality, the field, that is to say, of the mystery of the Incarnation and Crucifixion. Finally, the flame is the normal Christian symbol of the Paraclete, the Holy Spirit, as well as of that state of Gnostic Illumination (Sanskrit, bodhi; Greek, gnosis) by which the World Illusion is destroyed. And so, as a considered guess, it might be suggested that in the circumscribing serpent the powers symbolized are the Father and Holy Spirit (possibly associated with Erigena’s Uncreated Creating and Uncreated Uncreating), while in the lion we have the Son in the field of space and time — which interpretation may (or may not) be supported by the fact that in the Irish Lebar Brecc, where Patrick’s biography is recorded, Christ, the Son, is represented not as second but as third person of the Trinity.Note 13

In any case, the symbols of this important page are certainly not mere scrimshaw but a commentary on the text, suggesting, moreover, an association of the Christian with earlier symbolic forms. And the background of their statement, equally certainly, was a form of Christianity not yet in accord with the Augustinian orthodoxy of the Byzantine Church councils. Sir Edward Sullivan, from whose beautiful publication of twenty-four color plates of The Book of Kells our figure has been drawn, has remarked that in the orthodox Latin Vulgate translation of the Gospel according to Matthew the passage here illuminated does not read Tunc crucifixerant, but Tunc crucifixi sunt; which is another sign, among many, of a differing line of communication.Note 14

The main point that I would bring out through all this, however, is simply that in the remote, recently pagan Irish province there was not such a radical rejection by the monks either of the virtues of natural man or of the symbols of pagan iconography as was to be characteristic of the later missionizing of the German tribes. In the words of Professor T. G. E. Powell in his recent study of The Celts:

Whereas in the early Teutonic kingdoms of Post-Roman Europe, the Church found but the most rudimentary machinery for rule and law, in Ireland the missionaries were confronted by a highly organized body of learned men with specialists in customary law, no less than in sacred arts, heroic literature, and genealogy. Paganism alone was supplanted, and the traditional oral schools continued to flourish, but now side by side with the monasteries. By the seventh century, if not earlier, there existed aristocratic Irish monks who had also been fully educated in the traditional native learning. This led to the first writing-down of the vernacular literature, which thus became the oldest in Europe next after Greek and Latin. … The continuity of native Irish traditional learning, and literature, from Medieval times backwards into prehistory is a matter of great significance, and one that has been little appreciated.Note 15

The old druidic training of the filid, or bards, by which they learned not only the entire native mythological literature by heart but also the laws according to which mythological analogies were to be recognized and symbolic forms interpreted, was applied in the early Christian period both to a reading of the symbolism of the Christian faith and to the recognition of analogies between this and the native pagan myths and legends. The dates of the birth and death of Cuchullin’s uncle, King Conachar, for example, were made to coincide with those of Christ’s nativity and crucifixion. Moreover, he was declared to have died as a result of learning, through the clairvoyance of a druid, of the crucifixion of Christ. And the soul of Cuchullin, after his death at the hand of Lugaid (when he had strapped himself to a pillar-stone so that he might die standing, not seated or lying down), was seen by thrice fifty queens who had loved him, floating in his spirit chariot, chanting a song of the Coming of Christ and the Day of Doom. He returned, furthermore, from his pagan Irish otherworld to converse cordially with Saint Patrick, as did, also, numerous other grand old heroes. And according to all accounts (all penned, it must be born in mind, by clerics), Patrick blessed the old pagans, delighted by their tales, all of which his scribe recorded in the work known to us as The Colloquy with the Ancients.

For instance, there was the giant Caeilte, who appeared with a company of his kind and their huge wolfdogs just when Patrick, lauding the Creator, was blessing an ancient fort in which Finn MacCumhaill (Finn McCool) once had dwelt. The clerics saw the big men draw near and fear overcame them; for those were not people of the same time or epoch of these clergy. Then Patrick, apostle to the Gael, rose and took his spergillum, to sprinkle holy water on the old heroes, floating over whom there were a thousand legions of demons. Into the hills and skalps, into the outer borders of the region and country, the demons thereupon departed in all directions; after which the great men sat down.

“Good now,” Patrick said to Caeilte; “what name hast thou?”

“I am Caeilte,” said he, “son of Crundchu son of Ronan.”

The clergy marveled greatly as they gazed; for the largest man of them reached but to the waist, or else to the shoulder, of any given one of the old pagans, and they sitting.

Patrick said: “Caeilte, I am fain to beg of thee a boon.” Who replied: “If I have but that much strength or power, it shall be had: at all events, enunciate the same.” “To have in our vicinity here a well of pure water,” Patrick said, “from which we might baptize the people of Bregia, of Meath, and of Usnach.” Said the giant: “Noble and righteous one, that I have for thee.” And they, crossing the fort’s circumference, came out. In his hand the big man took the saint’s, and in a little while they saw a loch-well right in front of them, sparkling and translucid. …

Patrick said: “Was not he a good lord with whom ye were; Finn MacCumhaill that is to say?” Upon which Caeilte uttered the following tribute of praise:

“Were but the brown leaf which the wood sheds from it gold, Were but the white billow silver:

Finn would have given it all away.”

“Who or what was it that maintained you so in your life?” Patrick asked; and the other answered: “Truth, which was in our hearts, strength in our arms, and fulfillment in our tongues.”

Many days they passed together, and on one of those days Patrick baptized them all, whereupon Caeilte reached across to the rim of his shield, from which he tore off a ridgy mass of gold in which there were three times fifty ounces, saying: “That was Finn the Chief’s last gift to me and now, Patrick, take it for my soul’s sake, and for my commander’s soul.”

And the extent to which that mass of gold reached on Patrick was from his middle finger’s tip to his shoulder’s highest point, while in width and in thickness it measured, as they say, a man’s cubit. And this gold was then bestowed upon the mission’s canonical hand bells, on psalters, and on missals.

But finally, after many days of strolling conversation, when the time came for the big men to be off and on their way, Caeilte addressed the saint. “Holy Patrick, my soul,” said he; “I hold that tomorrow it is time for me to go.”

“And wherefore goest thou?” Patrick asked.

“To seek out the hills and bluffs and fells of every place in which my comrades and my foster-fellows and the Fian-chief were along with me,” he answered; “for I am wearied with being in one place.”

They abode that night; the next day all arose; Caeilte laid his head on Patrick’s bosom, and the saint said to him: “By me to thee, and whatsoever be the place — whether indoors or abroad — in which God shall lay hand on thee, Heaven is assigned.”

Then the Christian King of Connaught, who had joined them, went his way to exercise royal rule; Patrick also went his way, to sow faith and piety, to banish devils and wizards out of Ireland, to raise up saints and righteous, to erect crosses, station stones and altars, also to overthrow idols and goblin images, and the whole art of sorcery. And touching Caeilte now: on he went northward, to the wide plain of the plains of Boyle, across the waterfall of Nera’s son, northward yet into the Curlieu mountains, in Keshcorann, and out upon the Corann’s level lands… ,Note 16

II. The Weird of the Gods

The Roman, P. Cornelius Tacitus (c. 55–c. 120 a.d.), in his Germania, has given the earliest known account of the life and religion of the German tribes beyond the Danube and the Rhine, who in his day were already threatening Rome and in the next three hundred years were to become its ruin.

In their ancient songs [states Tacitus], their only form of recorded history, the Germans celebrate the earth-born god Tuisto. They assign to him a son, Mannus, the author of their race, and to Mannus three sons, their founders, after whom the people nearest Ocean are named Ingaevones, those of the center Herminones, the remainder Istaevones. The remote past invites guesswork, and so some authorities record more sons of the god and more national names, such as Marsi, Gambrivii, Suebi and Vandilici; and the names are indeed genuine and ancient. As for the name of Germany, it is quite a modern coinage, they say. The first people to cross the Rhine and oust the Gauls are now called Tungri, but were then called Germans. It was the name of this tribe, not that of a nation, that gradually came into general use. And so, in the first place, they were all called Germans after the conquerors because of the terror these inspired, and finally adopted and applied the new name to themselves.

Hercules, among others, is said to have visited them, and they chant his praises before those of other heroes on their way into battle. …Note 17 They also carry into the fray figures taken from their sacred groves. …Note 18

Above all gods they worship Mercury, and count it no sin to win his favor on certain days by human sacrifices. They appease Hercules and Mars with the beasts normally allowed. Some of the Suebi sacrifice to Isis also. I cannot determine the origin and meaning of this foreign cult, but her emblem, made in the form of a light war-vessel, proved that her worship came in from abroad. They do not, however, deem it consistent with the divine majesty to imprison their gods within walls or represent them with anything like human features. Their holy places are the woods and groves, and they call by the name of god that hidden presence which is seen only by the eye of reverence… ,Note 19

The oldest and noblest of the Suebi, so it is said, are the Semnones, and the justice of this claim is confirmed by a religious rite. At a set time all the peoples of this blood gather, in their embassies, in a wood hallowed by the auguries of their ancestors and the awe of ages. The sacrifice in public of a human victim marks the grisly opening of their savage ritual. In another way, too, reverence is paid to the grove. No one may enter it unless he is bound with a cord. By this he acknowledges his own inferiority and the power of the deity. Should he chance to fall, he must not get up on his feet again. He must roll out over the ground. All this complex of superstition reflects the belief that in that grove the nation had its birth, and that there dwells the god who rules over all, while the rest of the world is subject to his sway. Weight is lent to this belief by the prosperity of the Semnones. They dwell in a hundred country districts and, in virtue of their magnitude, count themselves chief of all the Suebi.

The Langobardi, by contrast, are distinguished by the fewness of their numbers. Ringed round as they are by many mighty peoples, they find safety, not in obsequiousness but in battle and its perils. After them come the Reudigni, Aviones, Anglii, Varini, Eudoses, Suarini and Nuitones behind their ramparts of rivers and woods. There is nothing particularly noteworthy about these people in detail, but they are distinguished by a common worship of Nerthus, or Mother Earth. They believe that she interests herself in human affairs and rides through their peoples. In an island of Ocean stands a sacred grove, and in the grove stands a car draped with a cloth which none but the priest may touch. The priest can feel the presence of the goddess in this holy of holies, and attends her, in deepest reverence, as her car is drawn by kine. Then follow days of rejoicing and merry-making in every place that she honors with her advent and stay. No one goes to war, no one takes up arms; every object of iron is locked away; then, and then only, are peace and quiet known and prized, until the goddess is again restored to her temple by the priest, when she has had her fill of the society of men. After that, the car, the cloth and, believe it if you will, the goddess herself are washed clean in a secluded lake. This service is performed by slaves who are immediately afterwards drowned in the lake. Thus mystery begets terror and a pious reluctance to ask what that sight can be which is allowed only to dying eyes. …Note 20

In the territory of the Naharvali one is shown a grove, hallowed from ancient times. The presiding priest dresses like a woman; the gods, translated into Latin, are Castor and Pollux. That expresses the character of the gods, but their name is Alci. There are no images, there is no trace of foreign cult, but they are certainly worshiped as young men and as brothers. …Note 21

Turning to the right shore of the Suebian sea, we find it washing the territories of the Aestii, who have the religion and general customs of the Suebi, but a language approximating to the British. They worship the Mother of the Gods. They wear, as emblem of this cult, the masks of boars, which stand them in stead of armor or human protection and ensure the safety of the worshiper even among his enemies. They seldom use weapons of iron, but cudgels often. They cultivate grain and other crops with a patience quite unusual among lazy Germans. Nor do they omit to ransack the sea; they are the only people to collect the amber — glaesum is their own word for it — in the shallows or even on the beach. Like true barbarians, they have never asked or discovered how it is produced. For a long time, indeed, it lay unheeded like any other jetsam, until Roman luxury made its reputation. They have no use for it themselves. They gather it crude, pass it on unworked and are astounded at the price it fetches.Note 22

The Germans believe that there resides in women an element of holiness and prophecy, and so they do not scorn to ask their advice or lightly disregard their replies. In the reign of our deified Vespasian we saw Veleda long honored by many Germans as a divinity, whilst even earlier they showed a similar reverence for Aurinia and others, a reverence untouched by flattery or any pretence of turning women into goddesses… ,Note 23

There is no pomp about their funerals. The one rule observed is that the bodies of famous men are burned with special kinds of wood. When they have heaped up the fire they do not throw robes or spices on the top; but only a man’s arms, and sometimes his horse, too, are cast into the flames. The tomb is a raised mound of turf. They disdain to show honor by laboriously rearing high monuments of stone; they would only lie heavy on the dead. Weeping and wailing are soon abandoned — sorrow and mourning not so soon. A woman may decently express her grief in public; a man should nurse his in his heart.Note 24

Notable is the prominence given here to female divinities and their association with the soil, with planting, with the pig, with human sacrifice, and with such a festival car procession as may be witnessed to this day in any part of the world in which the cult of the goddess still prevails. The Aestii, whose language resembled the Celtic tongue of the Britain of that time, cultivated grain, held the boar sacred, and worshiped the mother of the gods. With this syndrome we are already familiar. The Anglii (Angles, the future English) worshiped the goddess Nerthus, Mother Earth, whose image was honored in a car procession and bathed — after which those who had bathed the image were drowned in a lake on her sacred isle. One thinks of the legend of the Greek hunter Actaeon. who, chancing upon Artemis bathing in her forest pool, was transformed by her into a stag, to be slain by his own hounds; and one thinks, too, of the impudent young adept in the temple of the goddess in Egyptian Sais, who, when he made bold to lift the veil of her image was struck so with amaze that his tongue was thereafter ever dumb. For it was she who had declared: “There is none who has lifted my veil” (οὐδεὶς ἐμὸν πέπλον ἀνεῖλε); that is to say: none who has lived to reveal the secret of my divine motherhood of the world.Note 25

The priest of the Naharvali, furthermore, garbed as a woman, supervising the sacred grove where twins resembling Castor and Pollux were revered, suggests the eunuch priests of the great Syrian goddess Cybele. And finally, the goddess whom Tacitus identified with Isis — honored like her as a goddess of the sea and of ships — may or may not have been the late import he supposed. For the evidence given by these Germanic forms, of an ancient continuity from as far back as the earliest neolithic infiltration of Europe, is strong enough to support almost any theory of dating that one might wish to propose. In fact, these various goddesses of the German tribes of the first century a.d. are exactly what one should have expected to find in a zone of numerous strains of neolithic diffusion. The tribal genealogies from the god Tuisto, born of the goddess Earth, resembling as they do the Earth-born genealogies of Hesiod, lend to this picture additional support. And so it appears that we may safely assert that whether in the early Greek and Celtic, or in the later Roman and Germanic zones, the European neolithic heritage produced largely homologous mythic forms, derived from and representing the old order of the great Age of the Goddess: and it was upon this basic stratum that the later layerings of high culture myth were superimposed.

The question remains then as to what these later layerings may have been; and germane to this question is Tacitus’s naming of Hercules, Mercury, and Mars as the Latin counterparts of three important German deities to whom, in his time, sacrifices were addressed. These have been identified unquestionably as Thor, Wodan, and Tiu — after whom, as we have seen, our Thursday, Wednesday, and Tuesday have been named. In the brilliant literature of the Icelandic Eddas and Middle High German Nibelungenlied, from which Wagner drew his mighty Ring, they are among the most prominent male divinities. And just as in the period of Tacitus’s account, so also in the Eddie period, one long millennium later, the figure of Wodan-Mercury was the god paramount, above all.

The figure of Thor, however, shows signs of being the eldest of the pantheon, even going back, possibly, to the paleolithic age, when his celebrated hammer would have been properly a characteristic weapon. He is never equipped with a sword or lance, or mounted on a steed, like Wodan, but walks against his foes. And as a clever giant-killer, he has counterparts in the monster-killers of practically every primitive hunting mythology on record.Note 26 Heracles, among the Greeks, belonged to this primitive hero-type as well. But in the outrageously grotesque humor of the victories of Thor — which in many ways bear comparison with the legendry of the Dagda of the Celts — there is more of the primary mythic flavor of the old shaman-deeds of the heroes of the peoples of the Great Hunt than there is to be found among even the most bizarre of the epic hero tales of the Greeks.

For instance, when he was at one time full of wrath against the entire race of the giants, having just been tricked into playing the fool in their city, Jotunheim, he set forth to wreak revenge upon the most notable of their race, namely the Midgard Worm, the Cosmic Serpent, whose dwelling was the world-surrounding ocean. Thor assumed the unimpressive form of a mere lad and, walking so, came, one evening, at the edge of the world, to the dwelling of the giant named Hymir, of whom he asked shelter for the night. The following dawn, Hymir, the giant, got up quickly and dressed, with the idea of rowing out alone to sea, to fish; but Thor, perceiving, got up as quickly and dressed to go along. Hymir rebuffed him, saying that he would be of no help, being puny and a mere lad, and that he would freeze sitting out so far and long as the giant always sat; and the lad Thor became so angry at this insult that he withheld the fling of his hammer, Mjollnir, only because he intended a far greater feat at sea. Thor replied merely that he could row as far and sit as long as he pleased, and that it was not certain who would be the first out there to want home. He asked what bait they would be using and Hymir bade him fetch his own bait, whereat the lad turned and, setting out in his wrath to where he saw the giant’s herd of oxen, grabbing the largest bull, who was named “He Who Bellows to Heaven,” he tore off the animal’s head. Then he came lunging with this to the sea, where Hymir had already shoved out the boat.

The visitor boarded, sat on the bottom, took up two oars, and rowed; and to Hymir it seemed they made speed. The giant himself was rowing in the bow, and they made such speed that soon he could declare they had reached his fishing grounds for halibut. The guest said, however, that he wished to go on, so they pulled another stretch, until Hymir called out that they had come so far it would be dangerous to fare farther, because of the Worm. The lad, however, said again that he would go on, which he did; and the giant now was afraid.

Thor laid up the oars and made ready a strong line, nor was the hook that he had brought with him small, thin, or inadequate. He fixed the ox-head to this hook and flung it out to sea. To the bottom it descended, and the Midgard Worm, perceiving it, was fooled. The serpent struck at the ox head: the hook caught in his upper jaw: and when he felt that, he jerked back with such force that Thor’s two fists smacked on the gunwale. Angered, the god put forth then every bit of his strength, planting his feet so hard upon the bottom of the boat that when he pulled they went right through, and he was standing with them on the floor of the sea as he drew his catch up the side.

And it may be said that no more fearful sight was ever seen in the world than that which appeared when Thor’s eyes flashed upon the serpent, and the serpent, glaring up from below, let blow at him its venom. Then Hymir, the giant, grew pale, became yellow, and was afraid: when he saw the Midgard Worm itself there, and how the sea was rushing in and out through his boat. Thor reached for his hammer and raised it for the blow; but Hymir, snatching up his fish-knife, cut the line at the gunwale and the serpent sank into the sea. Thor flung his hammer at it and, some say, lopped off its head against the bottom. Others believe, however, that the Midgard Worm still lives and lies in the abyss of the all-embracing ocean. But the god, incensed, doubled his fist and drove rt against Hymir’s ear, who went overboard, head first. And Thor then waded back to land.Note 27

Thor is called, in Scandinavia, The Defender of the World, and amulet miniatures of his hammer have for centuries been worn to afford protection. At Stockholm, the museum holds one of amber from a late paleolithic date; and from the early metal ages fifty or more tiny T-shaped hammers of silver and gold have been collected. In fact, even to the present — or, at least, to the first years of the present century — Manx fishermen have been accustomed to wear the T-shaped bone from the tongue of a sheep to protect them from the sea; and in German slaughterhouses workers have been seen with the same bone suspended from their necks.Note 28

An unforeseen, somewhat startling overtone is added by this observation to the T-motif that has already been discussed in connection with the Celtic Christian Tunc-page (which is of a date when the Celtic and Viking spheres of influence were in many ways interlaced); and, of course, then vice versa: the apparently merely grotesque fishing episode acquires a new range of possible significance when the T of the Celtic page is identified with Thor’s hammer as well as with Christ’s cross. We might, in fact, even ask whether in Manx and German folklore the T-shaped bone of the sheep — the sacrificial lamb — may not have been consciously identified with the world-redeeming cross of the man-god Christ, as well as with the world-defending hammer of the native, far more ancient, even possibly paleolithic, man-god Thor.

In Tacitus’s day, as we have seen, Thor was identified with Hercules; but in later Germano-Roman times, the analogy was rather with Jove. Jove’s Day in the Latin world (giovedi in Italian; jeudi in French) became Thor’s Day (Thursday) among the Germans. Thor’s hammer, accordingly, was identified with the fiery bolt of Zeus — and with this analogy a vast range of new associations opens into the sphere of Hellenistic syncretistic thought.

Let us consider, first, the association of Jove and his planet Jupiter with the principle of justice and law. Scandinavian assemblies generally were opened on Thursday — Thor’s Day. The gavel of order is still Thor’s hammer. And at the Icelandic Things (court assemblies) the god invoked in testimony of oaths, as “the Almighty God,” was Thor.Note 29

The bolt of Jove, moreover, is cognate both in meaning and in origin with the vajra, “diamond,” “lightning bolt,” of the Mahāyāna Buddhist and Tantric Hindu iconographies. For, as already remarked, the lightning bolt is the irresistible power of truth by which illusions, lies, are annihilated; and again, more deeply read, the power of eternity through which phenomenality is annihilate. Like a flash of initiatory knowledge, lightning comes of itself and is followed by the roar and tumult of awakening life and rain — the rain of grace. And the idea of the diamond, too, has point in this connection; for as the lightning shatters all things, so does the diamond cut all stones, while the hard, pure brilliance of the diamond typifies the adamantean quality both of truth and of the true spirit.

The two ideas of lightning and diamond, then, which are combined in the Indian vajra, may be readily applied to the hammer of Thor. We have already noted a relationship between this sign and the great Mithraic lion-serpent man, Zervan Akarana (Figure 24). It is the weapon of Śiva and of the Solar Buddha Vairochana, the fiery bolt of Jove, and now, the mighty hammer of Thor. It is also the Cretan double ax of the Bull Sacrifice, and the knife in the hero Mithra’s hand with which he slew the World Ox.

Let us look once again at Thor’s fishhook — at its bait — and turn to Figure 23, where the World Serpent comes to the Mithraic sacrifice. Let us look once again, as well, at the Tunc-page of The Book of Kells and recall that, in the Christian view, Christ, the sacrifice who appeased the Father’s wrath, was by analogy the bait by which the Serpent Father was subdued. As the priest at Mass consumes the consecrated host, so did the Father consume the Willing Victim, his ever-dying, ever-living Son, who was finally, of course, his very Self.

How much of all this was rendered in the mythologies of the Germans of Tacitus’s day no one can know. There can be no doubt, however, of the period of the Eddas, Sagas, and Nibelungenlied. Nor is it even difficult to identify the paths and ways by which the great Hellenistic, syncretistic style of mythic communication penetrated beyond Roman reach, into the ramparts of the German rivers and woods.

First of all, we have the evidence of the runic script, which appeared among the northern tribes directly after Tacitus’s time. It is now thought to have been developed from the Greek alphabet in the Hellenized Gothic provinces north and northwestward of the Black Sea. Thence it passed — possibly by the old trade route up the Danube and down the Elbe — to southwestern Denmark, where it appeared about 250 a.d. and whence the knowledge of it was soon carried to Norway, to Sweden, and to England. The basic runic stave was of 24 (3 × 8) letters, to each of which a magical — as well as a mystical — value was attributed. In England the number of letters was increased to 33; in Scandinavia, reduced to 16. Monuments and free objects throughout the field of the German Völkerwanderung bear inscriptions in these various runic scripts, some telling of malice, others of love. For instance, on a late seventh-century stone standing in Sweden: “This is the secret meaning of the runes: I hid here power-runes, undisturbed by evil witchcraft. In exile shall he die by means of magic art who destroys this monument.” And on a sixth-century metal brooch from Germany: “Boso wrote the runes — to thee, Dallina, he gave the clasp.”Note 30

The invention and diffusion of the runes mark a strain of influence running independently into the barbarous German north, from those same Hellenistic centers out of which, during the same centuries, the mysteries of Mithra were passing to the Roman armies on the Danube and the Rhine. We do not know what “wisdom” was carried with the runes at that early date, but that in later times their mystic wisdom was of a generally Neoplatonic, Gnostic-Buddhist order is hardly to be doubted. Othin’s (Wodan’s) famous lines in the Icelandic Poetic Edda, telling of his gaining of the knowledge of the runes through self-annihilation, make this relationship perfectly clear:

I ween that I hung on the windy tree,

Hung there for nights full nine;

With the spear I was wounded, and offered I was

To Othin, myself to myself.

On the tree that none may ever know

What root beneath it runs.

None made me happy with loaf or horn,

And there below I looked;

I took up the runes, shrieking I took them,

And forthwith back I fell.

Then began I to thrive and wisdom to get,

I grew and well I was;

Each word led me on to another word,

Each deed to another deed.Note 31

No one knows who wrote these lines. They occur in the precious manuscript known as Codex Regius, in the Royal Library in Copenhagen, which appears to have been written c. 1300 a.d., and of which the contents (judging from the form of the language) must have been composed between c. 900 and 1050 a.d.Note 32 That is to say, the period of composition was that of the great Viking expeditions out of Scandinavia against the coasts and lands of France and the British Isles — on to Iceland, to Greenland, to Nova Scotia, and to Massachusetts; the age, as well, of the Viking kings and princes of Novgorod and Kiev, from whose appellation, Rhos or Rus (from the Old Norse, rodr, “rowing road”?),Note 33 the name of Russia is derived: years when to the prayers of the European Christian litanies the aspiration was added “From the fury of the Norsemen, deliver us!”

Much had come to pass since the period of Tacitus’s primitive account. In the first place, the impact of the Hunnish raids from Asia had set the entire German constellation in movement, so that tribes had been tossed from east to west, north to south, and back and forth from all sides. Secondly, a continuing stream of influence had come pouring into this caldron, first from Byzantium in the southeast, commencing strongly in the sixth century, and then, suddenly, from Islam in Sicily and in Spain. The Irish, meanwhile, largely from St. Columba’s island monastery of Iona (founded 563 a.d.) — whose missionaries, shaved from ear to ear across the front of the head and with long flowing locks behind, bearing in their hands long staves and with leathern water-bottles hanging from their backs together with food-wallets, writing-tablets, and relic-casesNote 34 — were diligently bearing the message of Christ back to the lands from which they themselves had received it, penetrating as far south as to Lake Constance and Milan. By the time the Viking period opened, c. 750 a.d., the Germans of the earlier phase of movement were already settled members of an established, crude but Christian, European culture province, marked off, on the one hand, from the Moors of the southwest and, on the other, from the now tottering Byzantine Christian Empire of the southeast: not in any sense a mere continuation or after-civilization of the earlier, worn-out Roman order, but the new and rapidly forming promise of a Gothic order, soon to be. And the Vikings of the marginal north were not the primitive tribesmen of Tacitus’s account seven centuries before, but developed, powerful barbarians, building and sailing great sea-craft, elegantly decorated, that were sent to sea in fleets of up to six hundred vessels, many of them twenty-five yards in length and of a register of some thirty tons.

“The number of ships grows,” wrote a chronicler of about 800 a.d.

The endless stream of Vikings never ceases to increase. Everywhere the Christians are victims of massacres, burnings, plunderings: the Vikings conquer all in their path, and no one resists them: they seize Bordeaux, Perigueux, Limoges, Angouleme and Toulouse. Angers, Tours and Orleans are annihilated and an innumerable fleet sails up the Seine and the evil grows in the whole region. Rouen is laid waste, plundered and burnt: Paris, Beauvais and Meaux taken, Melun’s strong fortress levelled to the ground, Chartres occupied, Evreux and Bayeux plundered, and every town besieged. Scarcely a town, scarcely a monastery is spared: all the people fly, and few are those who dare to say, “Stay and fight, for our land, children, homes!” In their trance, preoccupied with rivalry, they ransom for tribute what they ought to defend with the sword, and allow the kingdom of the Christians to perish.Note 35

And from the other side of the fiery scourge we have the following boyhood poem of the great Viking skald and warrior-magician, Egil Skallagrimsson (fl. c. 930 a.d.):

This did say my mother:

that for me should be bought

a ship and shapely oars,

to share the life of Vikings —

to stand up in the stem and

steer the goodly galley,

hold her to the harbor

and hew down those who meet us.Note 36

If the god Thor retains in his character something of the crude dawn memories of his people — the paleolithic hammer and the bold works of the primitive giant-killer — in the character of Wodan {Othin, Odin), primitive traits have all but disappeared, giving place to a steely-bright symbolic figure, highly fashioned and of great surface brilliance, but also of astounding depth. Wodan is the all-father of a securely structured, vastly conceived cosmology, inspired, like all of the great orders that we have studied, by the system of the priestly minds of ancient Sumer: developed, however, under influences from Zoroastrian, Hellenistic, and possibly, also, Christian thought; with the force of a type of warrior-mysticism that has already been represented to us in the military mysteries of Mithra and with a particular sense of destiny that is epitomized in the awesome old Anglo-Saxon word wyrd — from which our own word “weird,” as meaning “fate,” derives: the weird of the Weird Sisters of Macbeth.

We have already remarked that in Wodan’s heavenly warrior ball 432,000 warriors reside,Note 37 who, at the end of the cosmic eon, are to rush forth to the “war with the Wolf,” the battle of mutual slaughter of the gods and giants. On the dawn of that day the watchman of the giants, Eggther, would strike his harp, and above him the cock would crow, namely Fjalar, red and fair. To the gods would crow the cock Gollinkambi; and below the earth another cock would crow, rust-red, in the bowels of the goddess Hel. And then, as we read in the fate-laden verses, the hellhound Garm before its cave would howl, the fetters would burst and the wolf run free: “Much do I know,” states the prophetess of these lines, “and more can see of the weird of the gods”:

Brothers shall fight and fell each other,

And sisters’ sons shall kinship stain;

Hard is it on earth, with mighty whoredom;

Ax-time, sword-time, shields are sundered,

Wind-time, wolf-time, ere the world falls;

Nor ever shall men each other spare.

Yggdrasil shakes, and shiver on high

The ancient limbs, and the giant is loose.

How fare the gods? how fare the elves?

All Jotunheim groans, the gods are at council;

Loud roar the dwarfs by the doors of stone,

The masters of the rocks: Would you know yet more?Note 38

Another apocalypse thus appears before us.

From eastward come the giants faring in their ship Naglfar, formed of fingernail parings, steered by the giant Hrym with his shield held high. Alongside swims the Midgard Worm, and a giant eagle screams above. From the north there sails another ship, filled with the people of Hel, the shape-shifter Loki in control. And from the south appears a third ship, having Surt, the ruler of the fire-world at its helm, with a scourge of branches. Othin comes to engage the Wolf. The god Freyr seeks out Surt. Othin falls and his son Vithar avenges him, thrusting his sword to the Wolf’s heart. Thor confronts the Worm again. The bright snake gapes to heaven above and Thor in anger slays him, but turning walks nine paces and falls dead.Note 39

The sun turns black, earth sinks in the sea,

The hot stars down from heaven are whirled;

Fierce flows the steam and the life-feeding flame,

Till fire leaps high about heaven itself.

But then, behold!

Now do I see the earth anew

Rise all green from the waves again;

The cataracts fall, and the eagle flies,

And fish he catches beneath the cliffs.

Then fields unsowed bear ripened fruit,

All ills grow better, and Baldr comes back;

Baldr and Hoth dwell in Hropt’s battle-hall,

And the mighty gods: Would you know yet more?Note 40

There is no need to argue. The entire system of images of the cosmic tree of life and runic wisdom, the four cosmic directions with their companies of powers, the great eon of 432,000 years terminating in a cosmic battle, dissolution and renewal, accords perfectly with the pattern with which we are by now familiar. In this case, a point of great interest is the powerful sense of an impersonal cosmic process that infects the entire myth, while, at the same time, there is an insistence on the interplay of opposites that has suggested to some scholars a Persian, Zoroastrian source. The giant ship Naglfar, made of fingernail parings, suggests Persia also, where it was regarded as a fault to fail to make proper disposition of such parings. However, in the Eddie mythology the opposites in play are not conceived of in ethical terms; nor is it expected that in the future round the conflict of opposites will have ceased.

The old Germanic concept of the world beginning and rebeginning was of an essentially physical, not moral, conflict or interaction. As Snorri Sturluson tells in his Prose Edda:

In the beginning, there was but a Yawning Gap. In the north, then, the frigid Mist-World appeared, in the midst of which there was a well, from which the world rivers flowed.

In the south appeared the world of heat, glowing, burning, and impassable to such as have not their holdings there. And those frigid streams from the north, pressing toward the south, sent up a yeasty venom that hardened to ice, which halted, and the mist congealed to rime. And when the breath of southern heat met the rime, it melted, dripped, and life was quickened from the yeast drops in the form of a great sleeping giant Ymir.

A sweat came over Ymir and there grew under his left hand a male and female, one of his feet begat a son with the other, and thus the Rime Giants appeared. Moreover, there condensed from the rime a cow, her name Audumla, four streams of milk flowing from her udder; and she nourished Ymir. She licked the ice-blocks, which were salty, and the first day she licked, hair appeared on the blocks; the next day, a man’s head; and the next, the whole man was there. His name was Buri, fair of feature, great and mighty.

Buri begat Borr, who married the daughter of a giant and had three sons: Othin, Vili, and Ve, who slew the giant Ymir and fashioned of his body the earth: of his blood the sea and waters, land of his flesh, crags of his bones, gravel and stones from his teeth and broken bones; heaven they made of his skull, set over the earth, and under each corner they set a dwarf; fire and sparks from the south they scattered, some to wander in the sky, others to stand fixed, and so were made the sun, moon, and stars. And the earth was circular, with the deep sea round about. They assigned the outer edge of the earth to the giants; for the inward part they made a great citadel round about the world: and they called this Midgard. Of Ymir’s brain they made the clouds. And they fashioned man and woman of two trees, to which they gave spirit and life, wit and feeling, and then form, speech, hearing, and sight, clothing and names. Moreover, in the middle of the world they fashioned a city for themselves, of which there are many tidings and tales. Othin sat there on high, his wife was Frigg; and their race is the race known as Aesir. All-father he is called, because he is the father of all the gods and of men, and of all that was fulfilled of him and of his might.Note 41

The gods give judgment every day at the foot of the Ash Yggdrasil, the greatest of all trees and best; its limbs spread over all the world, and it stands upon three roots: one is among the Aesir, one among the Rime Giants where formerly was the Yawning Void, and a third stands over the Mist World, beneath which last is the great worm Nidhoggr who gnaws the root from below (Compare The Consort of the Bull). Under the root among the Rime Giants lies Mimir’s well of wisdom, of which Mimir is the watcher; and he is full of ancient lore, since he ever drinks of the well. But the root among the Aesir is in heaven, where there is the very holy well known as Urdr, whereby the gods hold tribunal. Atop the Ash sits an eagle and between his eyes sits a hawk, at the root is the gnawing worm, and a squirrel, Ratatoskr, runs up and down the trunk of the Ash, bearing envious words between Worm and Eagle. Four harts, moreover, run among the limbs and bite the leaves. …

As we have seen, All-father Othin hung upon that tree and, like Christ upon the cross, was pierced by a lance: the lance, his own; and he, a sacrifice to himself (his self to his Self) to win the wisdom of the runes. The analogy to be made, however, is rather to the Buddha at the Bodhi-tree than to Christ upon the cross, for the aim and achievement here was illumination, not the atonement of an offended god and the procurement thereby of grace to redeem a nature bound in sin. But on the other hand, in contrast to the Buddha, the character of this Man of the Tree is entirely with the world, and, specifically, in heroic-poetic disposition. Every day, in his great warrior hall, the champions at dawn arise, put on armor, go into the court, and fight and fell each other. That is their sport. And at evening they return to be served by Valkyries an inexhaustible mead, to sit later with them in love. And of the mead of poesy, as well, this god is the possessor and dispenser. For it was in the arts of war, in the arts of skaldic verse, and in the wisdom of the runes, that the power and glory of the Viking fleets consisted.

Poetry itself was Othin’s ale, and in poetry of his sort resided the power of life. But of himself there are so many forms and names that, as a bewildered royal candidate for his wisdom once complained: “It must indeed be a goodly wit that knows all the lore and the examples of what chances have brought about each of these names.” To which the god himself, in the disguise of a mystic teacher, made reply: “It is truly a vast sum of knowledge to rake into rows. But it is briefest to say, that most of his names have been given him by reason of this chance: there being so many branches of tongues in the world, all people believed that it was needful for them to turn his name into their own tongue, by which they might the better invoke him and entreat him on their own behalf. But some occasions for those names arose, also, in his wanderings; and that matter is recorded in tales. Nor canst thou ever be called a wise man if thou canst not tell of those great events.”Note 42

Perhaps of all Othin’s wonders the most remarkable, however, is the fact that the last of his poets, to whom we owe the passage of his knowledge to ourselves, were professing Christians. Both Saemund the Wise (1056–1133), to whom the compilation of the Poetic Edda is credited, and Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241), the great warrior chieftain, skaldic poet, and author of the Prose Edda, prefigure something of the spirit of those poets of the Renaissance for whom the gods of the Greeks supplied the mystic language of an order of revelation antecedent to that of the Church. The Eddie system was — for those who knew how to read — eloquent of the same Stoic and Neoplatonic themes out of which the noblest minds of Europe had for centuries gathered strength; and for those of a Pelagian conviction of heart, for whom nature could never be convincingly traduced, the old gods were not unfitting associates of the angels. They were, in fact, the northern counterparts of the very gods of those Hellenistic mysteries of the noughting of the self, out of whose iconographies the ritual lore and setting of the gospel of Christianity itself had been derived. Thus in the Eddas, no less than in the Celtic hero tales, we have, as it were, the serpent-lions of The Book of Kells without the Gospel text: the setting (one of faith might say) without the jewel of price. However, to those who had learned the reading of the runes — for which Othin gave himself in gage — nature itself revealed the omnipresent jewel.

III. ROMA

The following authoritative formulation of the Christian myth was set forth by the mighty Pope Innocent III (1198–1215) at the Fourth Lateran Council, November 1215. Its purpose was to fix for all time the ultimate Procrustean bed to which all thinking men were thenceforth to be trimmed. And they were being trimmed to it indeed in the time of this shining statesman of the Church, from whose elegant pen no less than 4800 masterfully composed personal letters have survived. Historians name him “the greatest of the popes.” In the annals of religion the Fourth Lateran Council, which he summoned and over which he presided, marked the consummation of the most awesome victory over heresy by an orthodox consensus that the world had yet beheld, and therewith the apogee of papal power in its implementation of a gospel that has been venerated for two thousand years as the purest statement known to mankind of the principle of love.

“We firmly believe and simply confess,” wrote this great inheritor of Peter’s keys,

that there is only one true God, eternal, without measure and unchangeable; incomprehensible, omnipotent, and ineffable, the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit: three persons indeed, but one simple essence, substance, or nature altogether; the Father of none, the Son of the Father alone, and the Holy Spirit of both alike, without beginning, always and without end; the Father begetting, the Son being born, and the Holy Spirit proceeding; consubstantial, and co-equal, and co-omnipotent, and co-eternal; one principle of all things; the creator of all things visible and invisible, spiritual and corporal; who by His omnipotent virtue at once from the beginning of time established out of nothing both forms of creation, spiritual and corporal, that is the angelic and the mundane, and afterwards the human creature, composed as it were of spirit and body in common. For the devil and other demons were created by God; but they became evil of their own doing. But man sinned by the suggestion of the devil.

This Holy Trinity, undivided as regards common essence, and distinct in respect of proper qualities of person, at first, according to the perfectly ordered plan of the ages, gave the teaching of salvation to the human race by means of Moses and the holy prophets and others His servants.

And at length the only-begotten Son of God, Jesus Christ, incarnate of the whole Trinity in common, being conceived of Mary ever Virgin by the cooperation of the Holy Spirit, made very man, compounded of a reasonable soul and human flesh, one person in two natures, showed the way of life in all its clearness. He, while as regards His divinity He is immortal and incapable of suffering, nevertheless, as regards His humanity, was made capable of suffering and mortal. He also, having suffered for the salvation of the human race upon the wood of the cross and died, descended to hell, rose again from the dead, and ascended into heaven; but descended in spirit and rose again in flesh, and ascended to come in both alike at the end of the world, to judge the quick and the dead, and to render to every man according to his works, both to the reprobate and to the elect, who all shall rise again with their own bodies which they now wear, that they may receive according to their works, whether they be good or bad, these perpetual punishment with the devil, and those everlasting glory with Christ.

There is moreover one universal Church of the faithful, outside which no man at all is saved, in which the same Jesus Christ is both the priest and the sacrifice, whose body and blood are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the species of bread and wine, the bread being transubstantiated into the body and the wine into the blood by the divine power, in order that, to accomplish the mystery of unity, we ourselves may receive of His that which He received of ours. And this thing, the sacrament to wit, no one can make but a priest, who has been duly ordained, according to the keys of the Church, which Jesus Christ Himself granted to the apostles and their successors.

But the sacrament of baptism, which is consecrated in water at the invocation of God and of the undivided Trinity, that is of the Father, and of the Son and Holy Spirit, being duly conferred in the form of the Church by any person, whether upon children or adults, is profitable to salvation. And if anyone, after receiving baptism, has fallen into sin, he can always be restored by true penitence.

Not only virgins and the continent, but also married persons, deserve, by right faith and good works pleasing God, to come to eternal blessedness.Note 43