Chapter 4 — GODS AND HEROES OF THE EUROPEAN WEST: 1500-500 b.c.

I. The Dialogue of North and South

Fortunately it will not be necessary to argue that Greek, Celtic, or Germanic myths were mythological. The peoples themselves knew that they were myths, and the European scholars discussing them have not been overborne by the idea of something uniquely holy about their topic. Not many studies comparing these myths with the biblical have been made; but within the European field itself so much first-rate, sober scholarship has been deployed that in the present chapter we are at last, so to say, on home ground.

Friedrich Nietzsche was the first, I believe, to recognize the force in the Greek heritage of an interplay of two mythologies: the pre-Homeric Bronze Age heritage of the peasantry, in which release from the yoke of individuality was achieved through group rites inducing rapture; and the Olympian mythology of measure and humanistic self-knowledge that is epitomized for us in Classical art. The glory of the Greek tragic view, he perceived, lay in its recognition of the mutuality of these two orders of spirituality, neither of which alone offers more than a partial experience of human worth.

Nietzsche was but twenty-eight when The Birth of Tragedy appeared in 1872 — the very year when his elder countryman Heinrich Schliemann was unearthing Troy, to reveal within Homer’s mythic world its core of historical fact. In his later years Nietzsche criticized his book as a work of youthful pessimism and aestheticism, composed within sound of the guns of the Franco-Prussian War, under a spell of Schopenhauer and Wagner. However, the justness of his insight has since been demonstrated by the findings of a century of archaeological research into fields of which not even the main outlines had appeared in his day.

As the record now stands, the earliest known population to enter Greece arrived c. 3500 b.c. There seem to have been no paleolithic or Mesolithic settlements on the peninsula. The immigrants arrived from Asia Minor by sea, bearing a developed agrarian-pastoral culture of high neolithic style: fine ceramic wares, polished stone tools and weapons, knives of obsidian (from Melos?), which they continued to import, and the usual female figurines. They settled chiefly on the plains of Thessaly, Phocis, and Boeotia, building small, rectangular, flat-roofed homes of brick on stone foundations. A few moved north, to the banks of the river Haliacmon in southernmost Macedonia; others moved south into Attica, broached the Peloponnese, and settled here and there in Argolis, Arcadia, Laconia, and Messenia; but there was little or no expansion of these people west.

Then, however, as the ruins let us know, c. 2500 b.c. one of the northernmost of their towns, at Servia on the Haliacmon, was destroyed by fire; and there appear in the ruins, dramatically, the artifacts of a totally different, crude, pastoral people from the north.

“The intrusive culture,” states Professor N. G. L. Hammond in his superb History of Greece to 322 b.c., “is marked by a different style of pottery which is cruder in technique; its ornamentation includes incised parallel zigzag lines and the moulding of beaded and arcaded patterns.”

Two burials [he continues] have been discovered in the layer which succeeds the destruction by fire. In the first the body was buried in a pit, in a contracted attitude with one hand held up to the face; beside it lay vases and an obsidian blade. In the second, which lay over the first burial, there were found beside the skeleton some fragments of a marble bracelet and lid, bone pins, and a clay phallus.

From Sérvia this intrusive culture, already influenced and enriched by contact with the Thessalian culture, spread eastwards into central Macedonia and Chalcidice and southwards into Thessaly. … The spread of the new culture is marked by incised pottery, spiral decoration, stone battle-axes, phallic emblems, and a new type of house. The phallic emblems, of which the first example occurs in the burial at Servia, indicate a worship of the masculine aspect of life, and are in marked contrast to the female statuettes of the Neolithic Thessalian culture. When the intruders settled at Dhimini and Sésklo in Thessaly, they fortified their villages with a ring-wall. Later they built houses with a porch, which was often supported on wooden pillars, and with an indoor hearth set towards one side. Such houses were probably the prototypes from which the typical Mycenaean house — the “Megaron” — developed centuries later.Note 1

The subsequent stages of the dialogue of these two prehistoric cultures in Greece may be summarized for our purpose in the following schedule.

PHASE 1: EARLY HELLADIC GREECE — TROY I TO V: c. 2500-1900 b.c.

Arrival and establishment of early Bronze Age forms: ready fusion with neolithic predecessors, impressive development of buildings.

Troy, controlling entrance to Dardanelles, grows from fishing village (Troy I) to large commercial port (Troy V).

In Greece, two regional pottery styles: 1. north of Isthmus, light figures on dark ground (trade with Troy and northwest Asia Minor), 2. south of Isthmus, dark figures on light ground (trade with Aegina and Cycladic Isles).

PHASE II: MIDDLE HELLADIC GREECE — TROY VI EARLY PHASE: c. 1900-1600 b.c.

Violent destructions in eastern Greece. Appearance of Megaron type of dwelling. Two new potteries: 1. matt-painted (developed from early Bronze Age styles), 2. gray “Minyan” ware (thrown on potter’s wheel, imitating metal forms).

Fall of Troy V, founding of fortified Troy VI. In Troy, the horse appears (Compare to Hurrian-Kassite contribution from East?).

New and powerful dynasty at Mycenae (Shaft Grave Dynasty I): skeletons in extended posture, some 5½ to 6 feet tall (far taller race than Minoan); elegant grave gear, excellent metalwork in gold, silver, and electrum (no resemblance to Minoan). Trade continues with Troy and Cycladic Isles. First direct contacts made with Crete.

From the remains of this stage it is evident that the Aryans, Nordics, or Indo-Europeans coming down from the north had already received a considerable cultural contribution from the “Painted Pottery” and other settled peoples of the Danube zone. They were not exactly paleolithic hunters, but developed pastoral nomads, comparable in culture — though not in temperament — to their contemporaries in the Near East, the Akkadians, who, under Sargon of Agade, had become the masters of the old Sumerian world. Having reached the southern shores of Greece and established contact with the elegant civilization of Crete, they were about to receive and submit to its cultural influence.

PHASE III: LATE HELLADIC I — TROY VI EARLY MIDDLE PHASE: c. 1600-1500 b.c.

Period of the apogee of Crete (Late Minoan IA): dominance of Knossos throughout the Aegean.

Start of Minoization of Mycenae: new dynasty (Shaft Grave Dynasty II): skeletons in contracted posture, horse-drawn chariots, elegant inlaid daggers with graceful hunting and war scenes (Mycenaean motifs, craftsmen probably Minoan), boar’s-tusk helmets (not Minoan), amber jewelry (Baltic amber unknown in Crete). In men’s graves: breastplates and death masks of gold (mask showing visage with beard and mustache), swords, daggers, gold and silver cups, gold signet rings; stone, clay, and metal vessels. In women’s graves: gold frontlets, toilet boxes, jewelry, and disks. A Theban fresco shows the women in Minoan dress.

Great extension of Mycenaean influence throughout Argolis and into Boeotia: similar dynasties appear at Thebes, Goulas, and Orchomenus. Trade meanwhile increasing with Troy.

PHASE IV: LATE HELLADIC II — TROY VI LATE MIDDLE PHASE: c. 1500-1400 b.c.

Rise of Mycenae over Crete (Late Minoan IB and II): new, very powerful Mycenaean dynasty (Tholos Tomb Dynasty I): large, circular, domed tombs carved directly into hillsides, covered with earth, faced with masonry, and closed by massive doors; approached by long, unroofed passages. Strong fusion of Mycenaean and Minoan art forms (Minoan dominant). Trade throughout Sea of Crete to detriment of Knossos.

c. 1450 b.c.: Cretan palaces destroyed (earthquake? attack?)

Mycenaean-Cretan connections interrupted

Mycenaean colony in Rhodes

c. 1425 b.c.: Mycenaean colony in Cos

High Bronze Age commerce now at apogee, circulating merchandise from Nubia (gold), Cornwall, Hungary, and Spain (tin), Sinai and Arabia (copper); Baltic amber; European hides, timber, wine, olive oil, and purple dye; Egyptian rope, papyrus, and linen.

Period of Egyptian Dynasty XVIII and Stonehenge III.

PHASE V: LATE HELLADIC III A — TROY VI FINAL PHASE: c. 1400-1300 b.c.

Hittite hegemony in Asia Minor, associated with Troy: Hittite King Mursilis II (c. 1345–1315) mentions kings of Ahhiyava (Achaeans). Achaeans now fighting as allies of Hittites and as mercenaries in Egypt. (Period of Ikhnaton, 1377–1358: Habiru are harassing Syria and Palestine.)

c. 1400 b.c.: Mycenaean conquest of Crete.

c. 1350 b.c.: Palace of Mycenae greatly enlarged: cyclopean walls, “Lion Gate,” etc.; vast tholos tombs (“Treasury of Atreus,” dome 40 feet high). Cretan cities revive under Achaeans: invention of Linear B (Mycenaean) script. Troy also flourishing within massive fortifications.

c. 1325 b.c.: A new type of slashing sword appears in Aegean area (first used in Hungary), requiring new type of armor: small circular shield on arm (replacing great bull-hide shield hung from shoulder), peaked or horned helmet, deflecting downward slash, c. 1300 b.c.: Troy VI destroyed by earthquake.

PHAST VI: HOMER’S TROY (TROY VII): c. 1300-c. 1184 b.c.

A mighty and wonderful city, exactly as in the Iliad, wealthy, and with flourishing trade. …

And so we arrive at the epic date of the deeds of Homer’s heroes: the date, as well, of those of the Book of Judges. The two heroic ages were simultaneous. In both domains there had been a long period of interplay and adjustment between settled agricultural and intrusive pastoral-warrior peoples, after which, very suddenly, overwhelming onslaughts of fresh pastoral-warrior folk (in Palestine the Hebrews, in Greece the Dorians) precipitated a veritable Götterdämmerung and the end of the world age of the people of bronze. The exploits of Homer’s “divine race of heroes” fall in the period c. 1250-1150, and following a lapse of about three centuries their epics took form, their dates coinciding approximately with the biblical; as follows:

c. 850 b.c.: Iliad — Yahwist (J) Text

c. 750 b.c.: Odyssey — Elohim (E) Text

It is all too neat for mere coincidence; and, as Freud has remarked, there is the further problem of why in the case of Greece what appeared was poetry, and of the Jews, religion.

II. The Marriages of Zeus

It is instructive to contrast the history of the early Bronze Age cities of the Indus Valley with those of the Aegean. The dates of the two developments were about the same, c. 2500-1500 b.c., and the ultimate source of the two cultures also was the same, the nuclear Near East. But when the neolithic and Bronze Age arts and mythologies of village and city life spread to the Indus, they entered a zone of undeveloped paleolithic and Mesolithic jungle villages: one of the major provinces of that tropical, timeless, equatorial “second kind of culture” that Leo Frobenius termed “the invisible counter-player in the history of the culture of mankind.”Note 2 And the influence of that environment on the subsequent history of Indian mythology and civilization was decisive.

The variously killed, cut-up, and rotting human corpses, buried portions of flesh, and other ritually handled remains of the grisly rites that are common to all tropical culture provinces are supposed, on the analogy of the slips of plants, to be generating fresh, continuing human social growth. “The people live,” as Frobenius states, “in the spirit of the plant world; they identify themselves with it and it with themselves.”Note 3 The leading mythological theme throughout the tropical, equatorial zone is of the killed and cut-up divine being out of whose body the food plants grow. And the primitive rites of the entire zone are counterparts of that myth.Note 4 But in the High Bronze Age mythologies, too, the leading theme was of death and resurrection, rendered in rites of human sacrifice, often on a lavish scale. Consequently, when these myths and rites reached primitive India, where they met and joined the tropical, a rich compound of high and low, sophisticated and unadorned, modes of ritual murder developed, of which the blood-soaked cult of the black goddess Kālī and the burning of widows on their husbands’ funeral pyres are the best-known illustrations.

The remoteness of India from the primary centers of Bronze Age civilization left the promising Indus cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa to expire, as it were, on the vine. No signs of local cultural evolution have appeared in the archaeology of their sites, but only of gradual devolution;Note 5 and the rest of the great subcontinent, meanwhile, remained at a level of development about comparable to that of Melanesia today — which is, perhaps, not too bad (it seems, indeed, to hold charm for anthropologists), but neither is it to be compared with the flourishing Mediterranean world trade of that time in copper, gold, silver, and bronze, uniting in one vast developing community Mesopotamia and Egypt, Nubia and Spain, Ireland, Hungary, Crete, and Arabia.

Moreover, when the Indo-Aryan chariot fighters, cattle-herders, and Vedic chanters with their pantheon of Aryan gods (Indra, Varuna, Mitra, Vayu, Agni, and the rest), shattered the Indus cities and passed on to the Gangetic plain, c. 1500-1000 b.c., they too were left on the vine; and their valor, as well as that of their gods, was presently absorbed into the timeless, all-absorbing and regenerating substance of the goddess-mother Kālī, to the dreamy drone of “Peace! Peace! Peace! Peace to all living beings!” while the blood of beheaded victims poured in peace, continuously, as ambrosia, into her maw.

In the Aegean, on the other hand, the new orders of civilization came into a zone within call of descendants of the paleolithic Great Hunt on the broadly spreading animal plains of the north; who, furthermore, had been receiving and assimilating for centuries unremitting influences from the chief creative centers of the nuclear Near East. The field was one of significantly heightened energy; and, as we have just seen, after the first of the Aryan or proto-Aryan waves struck south, c. 2500 b.c., there followed others, wave upon wave, until, in direct contrast to the Indian denouement, it was not the mythic order of the goddess that consumed the gods, but the other way around. And the order that was so consumed, furthermore, was not of Melanesian cannibal ogresses, but of those elegant, lovely Parisiennes whom we have learned to know from Crete.

We have already watched Olympian Zeus conquer the serpent son and consort of the goddess-mother Gaea. Let us now observe his behavior toward the numerous pretty young goddesses he met when he came, as it were, to gay Paree. Everyone has read of his mad turning of himself into bulls, serpents, swans, and showers of gold. Every Mediterranean nymph he saw set him crazy. And in consequence, when the Greeks became in time as civilized as the Cretans, the philanderings of their highest god proved embarrassing to theology — as they need not have done, however, since all of his goddesses were actually but aspects of the one, in a gown, so to speak, of changeable jade; while he in each of his epiphanies was as different from his last as was the goddess in the case from hers. The formula for such divine multiplicity in unity is given in the Christian doctrine of the Trinity: one divine substance, three (or more) divine personalities. Comparably, in the Old Testament the different “angels of Yahweh” that appeared, for example, to Jacob, to Moses, and to Gideon, both were and were not Yahweh. Gods throughout the world have a way of doing this sort of thing, which to a close student of their habits never is surprising; though one used only to the logic of Aristotle might suppose that something unusual had occurred and cry, “O Lord, thy ways are inscrutable to mankind!”

The particular problem faced by Zeus in that period was simply that wherever the Greeks came, in every valley, every isle, and every cove, there was a local manifestation of the goddess-mother of the world whom he, as the great god of the patriarchal order, had to master in a patriarchal way. And when all these conquests were brought together by the systematists of the Alexandrian age, they came to a vivid docket. One fortunate consequence of this supernatural scandal was that it ultimately relieved the Greeks of their elder theology altogether — an effect such as one could wish to have seen brought to pass in certain other provinces of archaic myth. However, in the palmy days of the god’s marriages, they were of serious social worth, even though in the late narratives through which we hear of them they are presented with a certain levity.

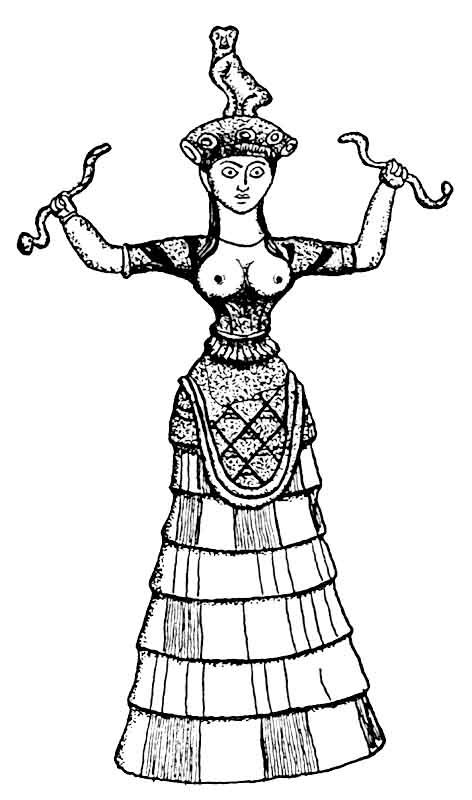

For instance, a prime example both of the humor and of the logic and function of this mythology may be seen in the legend of the birth of Pallas Athene. The name already appears on a Linear B tablet of c. 1400 b.c. from the Cretan palace city of Knossos. “A-ta-na Po-ti-ni-ja,” we read: “To the Lady of Athana.”Note 6 The word refers here to a place (as, for example, in the title “Our Lady of Chartres”), and is of pre-Hellenic speech. Professor Martin Nilsson believes the reference to be to a local goddess of the sort represented in the Cretan household and palace shrines (Figure 20 and Figure 21). “The [Cretan] palace goddess,” he writes, “was the personal protectress of the king, and such is the role assumed by Athene. … She is the guardian protectress of heroes.”Note 7 However, as the world knows, in the Classical pantheon Athene is represented not as an ancient Cretan divinity but as a young and fresh Olympian, born, literally, from the brain of Zeus.

Figure 20. The Serpent Goddess

For Zeus, at the start of his long career of theological assault through marriage, had taken as first wife the goddess Metis, daughter of the primal cosmic-water couple Oceanus and Tethys — who were exact counterparts of the Mesopotamian Apsu and Tiamat. And, as the eldest child of the Mesopotamian primal pair had been their first-begotten son Mummu, the Word, the Logos, Lord of Truth and Knowledge, so was Metis infinitely wise. She, in fact, knew more than all the gods. She knew, moreover, the art of changing shape, which she put to use whenever Zeus approached, until finally, by device, he made her his own and she conceived.

Figure 21. Aspects of the Serpent Goddess

But then Zeus learned that her second child, if born, would be the end of him; and so, inducing her to his couch (she pregnant still), he swallowed her at a gulp. And it was only some time later, while walking by a lake, that he began to feel an increasing headache. This grew until he howled; and, as some declare, Hephaestus, others say Prometheus, arrived with a double ax and gave his head a splitting blow: whereupon Athene, fully armed, sprang forth with a battle shout — and Zeus, thereafter, continued to claim that Metis, still sitting in his stomach, was giving him the benefit of her wisdom.Note 8

We have here, certainly, a graphic instance of what Freud has termed “sublimation”; applied, however, to a large historical (not merely individual) situation. The case resembles that of Adam giving birth to Eve, except that in the present case the woman is born of the deity himself. Furthermore, as Eve in her pre-Hebraic incarnation was the consort of the serpent, so in Crete the gifts presented to A-ta-na Po-ti-ni-ja were addressed to a serpent goddess; and on the Gorgoneum, the magically potent aegis of the Classical Athene, worn upon her chest, the Medusa head is affixed, with its terrible hair of tangled hissing snakes.

We have already spoken of Medusa and of the powers of her blood to render both life and death, We may now think of the legend of her slayer, Perseus, by whom her head was removed and presented to Athene. Professor Hammond assigns the historical King Perseus of Mycenae to a date c. 1290 b.c., as the founder of a dynasty;Note 9 and Robert Graves — whose two volumes on The Greek Myths are particularly noteworthy for their suggestive historical applications — proposes that the legend of Perseus beheading Medusa means, specifically, that “the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines” and “stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks,” the latter being apotropaic faces worn to frighten away the profane.Note 10 That is to say, there occurred in the early thirteenth century b.c. an actual historic rupture, a sort of sociological trauma, which has been registered in this myth, much as what Freud terms the latent content of a neurosis is registered in the manifest content of a dream: registered yet hidden, registered in the unconscious yet unknown or misconstrued by the conscious mind. And in every such screening myth — in every such mythology (that of the Bible being, as we have just seen, another of the kind) — there inheres an essential duplicity, the consequences of which cannot be disregarded or suppressed. Mother Nature, Mother Eve, Mother Mistress-of-the-World is there to be dealt with all the time, and the more sternly she is cut down, the more frightening will her Gorgoneum be. This may cause her matricidal son to achieve a lot of extremely spectacular escape work, and he may end by becoming master of the surface of the earth; but, oh, my! what a Sheol he will know — and yet not know — within, where his paradise should have been!

Well, anyhow: Medusa, in her lovelier, fresher, pre-Olympian centuries, had been one of the numerous granddaughters of Gaea, the goddess Earth, who, in the beginning, had brought forth of herself, without consort, Heaven (Uranus), the Hills (Urea), and the Sea (Pontus). Gaea had then conceived of her son Uranus the race of the Titans — which included Oceanus and Tethys, of whom Metis was born; also Cronus, Rheia, Themis, and, in a special manner, Aphrodite. Gaea, then conceiving of her son Pontus, gave birth to a second litter, amidst which Phorcys and Keto were numbered, who, in turn, became the parents of the Graeae, the Gorgons, and the serpent at the end of the world, who guards the golden apples of the Hesperides. Medusa’s name means “mistress,” “ruler,” “queen.” (We are on familiar ground, are we not?) And the god of the tides, Poseidon (whom we have also met before, as son and spouse of the Two Queens) had begotten twins upon her, to whom, however, she was unable to give birth: Chrysaor, the hero “of the golden sword,” and Pegasus, a winged horse.

Now, as we have seen, there is still a certain mystery about the coming of the horse to the Aegean. The arrival seems to have taken place between c. 2100 and 1800 b.c., with Troy an outstanding center; but whether from the north, by way of Macedon,Note 11 or from the east, through Anatolia, introduced from the Indo-Aryan context by the Hurrians and Kassites, seems not to be known. What we do know, however, is that in the Vedic-Aryan horse sacrifice, which in India became the high rite of kings,Note 12 the structure and symbology were largely adapted from the earlier bull sacrifice. And it further appears that the ritual of the bull sacrifice was in the Aegean preceded by that of the pig, which belongs to an extremely primitive, widely disseminated order of mythic lore, strongly evident in the myths and rites of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone of Eleusis. In Greece, furthermore, the myths and rites of the pig sacrifice show precise analogies with those of Melanesia and the Pacific, which, in turn, rested on a base of lunar-serpent thought. I have discussed all this in Primitive MythologyNote 13 and need not repeat the argument beyond noticing the moon-serpent-pig-bull-horse continuity and sequence.

Medusa and the other Greek goddesses of the old Titan generation, who were certainly at home in Greece and the Aegean long before the Hellenes appeared, exhibit every possible sign of an original relationship to an extremely early neolithic — perhaps even mesolithic — lunar-serpent-pig context that is represented in the myths and rites on one hand of Melanesia and the Pacific, and, on the other, of Celtic Ireland. In fact, the usual form in which Medusa is shown — squatting, arms raised, tongue lolling over the chin, eyes wide — is a pose that is characteristic of the guardian of the other world in the pig cults of Melanesia. There, she is a guardian demoness on the road to the yonder world, beyond whose ban the offering of a pig — offered in the way of a substitute for oneself — allows one to pass.Note 14 And Medusa is in exactly such a place in her cave beyond the edge of day, on the road to the golden apple tree. Compare, also, the sibyl Siduri of the Gilgamesh adventure.

But, at the same time, Medusa was linked in Classical Greece to the very much later mythic context of the sacrificial horse. She and Poseidon together, in fact, were associated with a mythology of horses that can have become attached to them only after c. 2000 b.c. In the Mycenaean Linear B tablets of c. 1400-1200 offerings are recorded to a god I-QO (hippo, “horse”); and we know that Poseidon was called Hippios in Classical times.Note 15 Poseidon in the form of a horse mated with Medusa as a mare, whence she conceived the winged Pegasus and his human twin Chrysaor. There is, moreover, as Robert Graves points out, “an early representation of the goddess with a Gorgon’s head and a mare’s body.”Note 16 Graves, therefore, reads the Perseus myth to mean in full: “The Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines, stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks, and took possession of the sacred horses.”

But now, just one more detail: Frazer, in The Golden Bough, has shown that there was a mythic association of the horse with Diana’s grove at Nemi, where the ritual regicide was enacted even in late Roman times. The princely youth Hippolytus, dragged to his death by his own chariot horses when they were frightened by a bull of Poseidon that came up at them from the sea, is supposed to have been revived by Diana and to have reigned at Nemi as her king, the King of the Wood. “And we can hardly doubt,” Frazer adds, “that the Saint Hippolytus of the Roman calendar, who was dragged by horses to death on the thirteenth of August, Diana’s own day, is no other than the Greek hero of the same name, who, after dying twice over as a heathen sinner, has been happily resuscitated as a Christian saint.”Note 17

So that we must now add to our view of the mythic context of Poseidon, Medusa, and the hero deed of Perseus, the mythology of the death and resurrection of the lunar king, and with that the ritual regicide. In an early chapter of Primitive Mythology I presented the record from Ethiopia of a Greek-educated king named Ergamenes, who, in the period of the Alexandrian pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus, 309–246 b.c., walked with a body of soldiers into the hitherto solemnly feared sanctuary of the Golden Temple, slew the priests who had been up to that time the readers of the oracle of the ritual regicide, discontinued the awesome old tradition, and reorganized things according to a new view of the destiny, function, and powers of a king.Note 18 By analogy, if Perseus was indeed the founder of a new dynasty at Mycenae, c. 1290 b.c., his violation of the neighboring goddess’s grove must have marked the end of an ancient rite — possibly of regicide — there practiced. The myth of his miraculous birth from the golden shower of Zeus then would have been of great moment, as validating his act in terms of a divine patriarchal order of belief that was now to supplant the old, of the mother-goddess in whom death is life.

Perseus, we are told, was conceived of Zeus miraculously by the princess Danae of Argolis, and sent floating with his mother in a water-worthy chest to sea. Drawn ashore on the isle of Seriphos by a fisherman, whose brother, Polydectes, was the local king, Danae with her child became the king’s slave — or, according to another version, his wife; or, according to still another, she remained with Dictys, the fisherman, his brother. But the king, like all monarchs in legends of this class, was a cruel ogre of a king, and to be rid of Perseus, so that he might enjoy his mother, he imposed upon the youth the very difficult — nay, impossible — task of procuring Medusa’s head.

This terrible monster had two sisters, and all three were endowed with golden wings, hands of brass, heads and bodies wreathed with snakes, and countenances with boar’s tusks, so dreadful to behold that anyone who saw them would be turned to stone. Perseus, on his way, passed through various mythic dangers, in the course of which adventures he received from the water nymphs a pair of winged sandals, a cap of invisibility, and a wallet in which to carry the captured head. With these he passed beyond the outermost sea, the outer rim of day, and, arriving in the realm of darkness into which stars and planets vanish for rebirth, he came first upon the curious triad of the Graeae. These were three old gray sisters, sharing a single tooth and eye, and when they were passing the eye, one to another, Perseus snatched and would not return it until they taught him the way to the Gorgons’ cave — which they were supposed to be guarding. After which, as Aeschylus tells, “boarlike, he passed into the cave.”Note 19

The Gorgons within were asleep, and while Perseus’s eyes were averted from the petrifying sight of Medusa, Athene, the patron goddess of heroes, gave guidance to his sword hand (or, as another telling has it, let him see his victim reflected in a shield). With a single stroke of his sickle-shaped blade, he took the trophy, stuffed it in his wallet, turned his back, and ran, while Pegasus and Chrysaor sprang from Medusa’s severed neck. The two sisters pursued. But Perseus reached home, where he produced his appalling prize, holding it high for all to see; and the tyrant king with his entire company at dinner became stone — which is why the isle of Seriphos today is so full of rocks.Note 20

III. The Night Sea Journey

The connotation of female personages in a patriarchal mythology is generally obscured by the device that Sigmund Freud termed, with reference to the manifest content of dream, “displacement of accent.” A distracting secondary theme is introduced, around which the elements of a situation are regrouped; revelatory scenes, acts, or remarks are omitted, reinterpreted, or only remotely suggested; and “a sense of something far more deeply interfused” consequently permeates the whole, which, however, rather baffles than illuminates the mind.

In the patriarchal cosmogonies, for example, the normal imagery of divine motherhood is taken over by the father, and we find such motifs as, in India, the World Lotus growing from the reclining god Viṣṇu’s navel — whereas, since the primary reference of the lotus in India has always been to the goddess Padma, “Lotus,” whose body itself is the universe, the long stem from navel to lotus should properly connote an umbilical cord through which the flow of energy would be running from the goddess to the god, mother to child, not the other way. Or in the Classical image of Zeus bearing Athene from his brain, where we have already recognized an example of “sublimation,” we now note that the “sublimation” has been rendered by means of an image of the type that Freud termed “transference upward”: as the woman gives birth from the womb, so the father from his brain. Creation by the power of the Word is another instance of such a transfer to the male womb: the mouth the vagina, the word the birth. And one extremely important consequence of this bizarre, but highly honored, aberration upward, is the notion, common to all Occidental spirituality — and particularly stressed by our numerous bachelor and homosexual great teachers — that spirituality and sexuality are opposed.

“By the displacement of the accent and regrouping of the elements,” Freud wrote in his elucidation of the censoring factor in dream, “the manifest content is made so unlike the latent thoughts that nobody would suspect the presence of the latter behind the former.”Note 21 And so it has been throughout all patriarchal mythologies. The function of the female has been systematically devalued, not only in a symbolical cosmological sense, but also in a personal, psychological. Just as her role is cut down, or even out, in myths of the origin of the universe, so also in hero legends. It is, in fact, amazing to what extent the female figures of epic, drama, and romance have been reduced to the status of mere objects; or, when functioning as subjects, initiating action of their own, have been depicted either as incarnate demons or as mere allies of the masculine will. The idea of an effective dialogue seems never to occur, where the male, with himself or his world shattered by one of those blazing demonesses (tragedy, alas!), should receive from her (in the underworld, as it were) some revelation beyond the bounds of his former horizon of thought and feeling (illumination, completion, rebirth). Throughout the literature images appear that obviously, in some earlier, pre-patriarchal context, must have pointed to initiations received by the male from the female side; but their accent is always so displaced that they appear on first glance — though not, indeed, on second — to support the patriarchal notion of virtue, arete, which they actually, in some measure, refute.

Even modern Classical scholarship has been collaborating largely in this patriarchal displacement. In fact, it required a female Classical scholar, the late and wonderful Jane Ellen Harrison, to remark the triviality and vulgarity of the episode from which the whole constellation of the glories and tragedies of the Trojan War was supposed to have derived: the Judgment of Paris.

The myth in its present form [she wrote] is sufficiently patriarchal to please the taste of Olympian Zeus himself, trivial and even vulgar enough to make material for an ancient Satyr-play or a modern opéra-bouffe.

“Goddesses three to Ida came

Immortal strife to settle there —

Which was the fairest of the three,

And which the prize of beauty should wear.”

The bone of contention is a golden apple thrown by Eris [“Strife”] at the marriage of Peleus and Thetis among the assembled gods. On it was written, “Let the fair one take it,” or, according to some authorities, “The apple for the fair one.” The three high goddesses betake them for judgment to the king’s son, the shepherd Paris. The kernel of the myth is, according to this version, a καλλιστεῖον, a beauty contest.Note 22

And the informing ethos of the myth, we might add, is that arete, or pride in excellence, which has been called the very soul of the Homeric hero — as it is the soul, also, of the Celtic and Germanic; or, indeed, everywhere, of the unbroken male.

But here it is represented as proper to the female soul as well — which is the rub. In this masculine dream world, the excellence of the female is supposed to reside in: a) her beauty of form (Aphrodite), b) her constancy and respect for the marriage bed (Hera), and c) her ability to inspire excellent males to excellent patriarchal deeds (Athene). Along with which, finally, of course, being a woman, the winner of the beauty contest cheats. Aphrodite promises Paris that if she is given the golden apple, she will procure for him the golden beauty Helen, who is already married to Menelaus. “A beauty contest,” states Miss Harrison in undisguised disgust, “vulgar in itself and complicated by bribery still more vulgar.”Note 23 Yet for generations this seems to have been accepted as the adequate mythic (i.e., unimportant) start of the world’s most noble epic of “excellence” (ἀρετἠ), and all that followed in its train.

What followed were the Nostoi, “Returns,” when the masters of excellence in the world of the outer deed returned to their neglected wives, who for ten years (or, in Odysseus’s instance, twenty) had been supposed to be sitting faithfully, in the manner of Griselda, at home (redemption by love, patriarchal style). However, as we know, one of the returning heroes, at least, received a formidable shock.

There is a principle of complementarity operating in the psyche, in society, in history, and in the symbolism of myth, which Dr. Carl G. Jung has discussed throughout his writings and illustrated from every quarter of the globe. “No matter how much we make conscious,” he once wrote, in discussion of the mechanics of this principle, “there will always be an indeterminate and indeterminable quantity of unconscious elements, which belong to the totality of the self.”Note 24 But these unconscious elements do not simply rest in the psyche, inert. As unrealized potentialities, they are invested with a certain readiness for activation in compensatory counterplay to the conscious attitude; so that whenever in the sphere of conscious attention a relaxation of demand occurs and the individual is no longer required to bring all of his energies to bear upon his one intended goal — as, for example, the winning of the Trojan War — the released, disposable energies turn back, as it were, and flow to the waiting centers of potential experience and development. “It does not lie in our power,” Jung declares, “to transfer ‘disposable’ energy at pleasure to a rationally chosen object.”Note 25 On the contrary, the transfer is inevitably not only out of control, but also complementary to the conscious will; for, as Jung observes, quoting Heraclitus, who, as he says, was indeed a very wise man, “everything tends sooner or later to go over into its opposite.”

The old Greek philosopher Heraclitus (c. 500 b.c.) called this process of psychological, historical, and cosmogonic overbalancing enantiodromia, “running the other way.” And as an example of the process no better instance could be sought than that supplied by the two contrasting epics of Homer on which Heraclitus and his whole generation were raised: on one hand, the Iliad, with its world of arete and manly work and, on the other, the Odyssey, the long return, completely uncontrolled, of the wisest of the men of that heroic generation to the realm of those powers and knowledges which, in the interval, had been waiting unattended, undeveloped, even unknown, in that “other mind” which is woman: the mind that in the earlier Aegean day of those lovely beings of Crete had made its sensitive statement, but in the sheerly masculine Heroic Age had been submerged like an Atlantis.

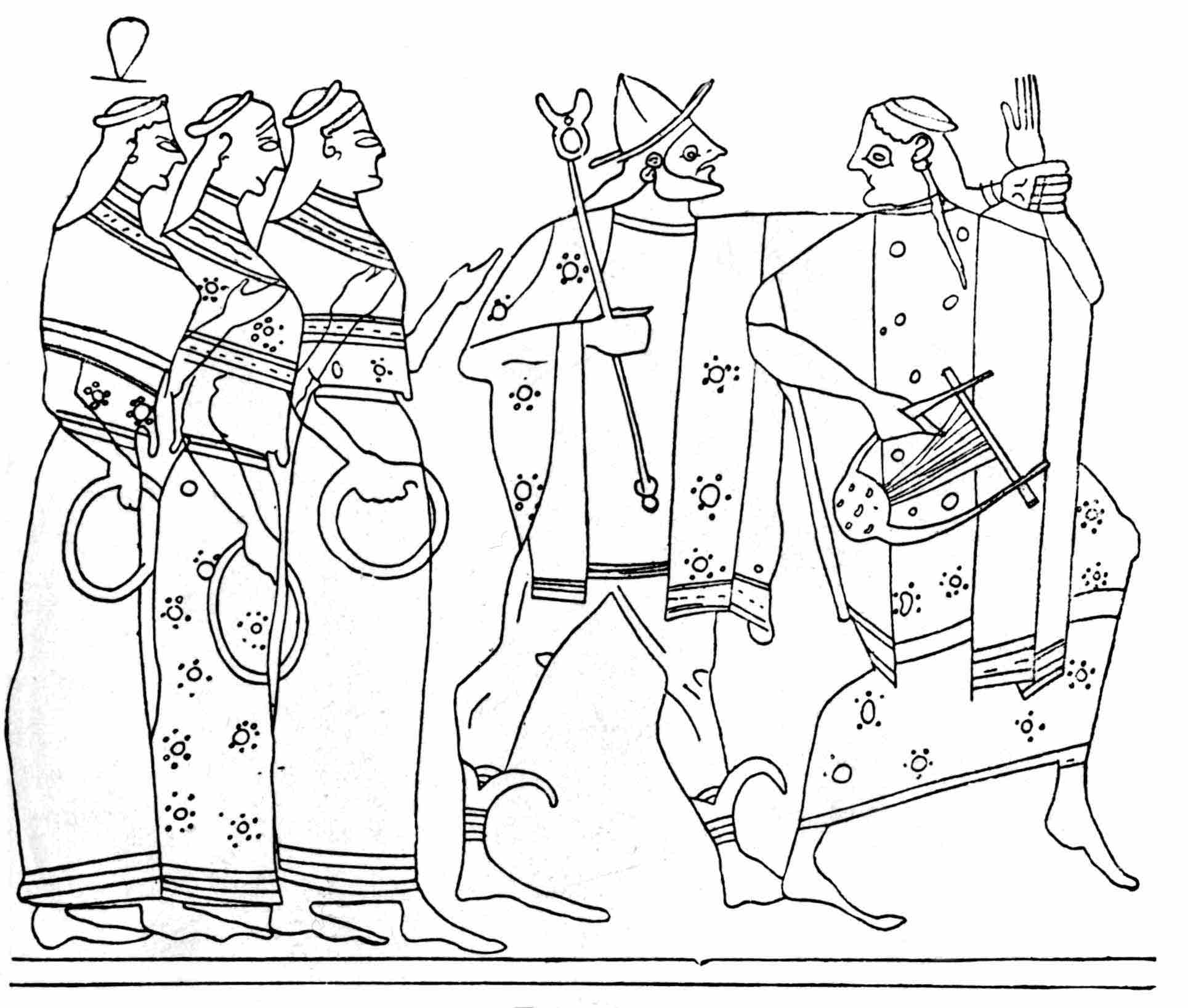

Figure 22. The Judgment of Paris

Jane Harrison shows an illuminating series of scenes derived, not from the literary Homeric side of the Greek tradition of the Judgment of Paris, but from the elder, wordless heritage of ceramic art. And there we see, as for example in Figure 22, not a youth in the usual languid pose of an accomplished boulevardier, but a Paris in manifest alarm, whom the god Hermes — guide of souls to the underworld — has actually had to seize by the wrist to compel attendance to his task. “There is here,” observes Miss Harrison, “clearly no question of voluptuous delight at the beauty of the goddesses.”Note 26 And in fact, as one looks, there is not.

Conveniently for my present theme, the direction of Paris’s flight in this picture is toward Troy, while the triad of the feminine principle, which he is obviously being required to face for some crisis in his own lot, not in theirs, stand on the side of the Greek homeland, where Agamemnon was to meet Clytemnestra, Menelaus his recaptured golden girl, and the great and wise Odysseus (who would be the only one up to the occasion) Penelope and her galaxy of suitors. I would suggest that we think of the short life full of deeds and fame, warcraft, arete, Zeus, and Apollo as off to the right, and on the left, besides the old goddesses of the time and tide of Mother Right, the mystic isles of Circe, Calypso, and Nausicaa, with Hermes in the role of the guide of souls to the underworld and to knowledges beyond death.

Heinrich Schliemann guessed correctly that there had actually been a Troy and Trojan War, and by following the lead of the epic found both Troy and the city of Mycenae. Likewise, Sir Arthur Evans unearthed Knossos and the palace of the labyrinth by following clues in the literature of Classical myth. “But,” as Professor Martin Nilsson has remarked, “in one case the lead of mythology failed — when Dorpfeld searched for Odysseus’ palace on Ithaca; and furthermore,” he adds, “we now know why. For the Odyssey is not a semi-historical heroic saga, but a sheer novel, built on the well-known theme of the wife who remains true to her long departed husband thought to be dead.”Note 27 Well, yes, in a way! So far, so good! But that particular way of reading this novel, my dear professor, is only from the displaced point of view of the patriarchal, secondary focus. There is a lot more depth to Penelope than that.

The patron god of the Iliad is Apollo, the god of the light world and of the excellence of heroes. Death, on the plane of vision of that work, is the end; there is nothing awesome, wondrous, or of power beyond the veil of death, but only twittering, helpless shades. And the tragic sense of that work lies precisely in its deep joy in life’s beauty and excellence, the noble loveliness of fair women, the real worth of manly men, yet its recognition of the terminal fact, thereby, that the end of it all is ashes. In the Odyssey, on the other hand, the patron god of Odysseus’s voyage is the trickster Hermes, guide of souls to the underworld, the patron, also, of rebirth and lord of the knowledges beyond death, which may be known to his initiates even in life. He is the god associated with the symbol of the caduceus, the two serpents intertwined; and he is the male traditionally associated with the triad of those goddesses of destiny — Aphrodite, Hera, and Athene — who, in the great legend, caused the Trojan War.

The war lasted ten years and Odysseus’s voyage ten. But as the grand old master of Classical lore, Professor Gilbert Murray, pointed out some decades ago in his volume on The Rise of the Greek Epic, in the Classical period the effort to coordinate the lunar and solar calendars (the twelve lunar months of 354 days plus a few hours, and the solar year of 364 days plus a few hours) culminated in the astronomer Meton’s “Grand Cycle of Nineteen Years,” according to which (to quote Murray’s statement): “On the last day of the nineteenth year, which was also by Greek reckoning the first of the twentieth, the New Moon would coincide with the New Sun of the Winter Solstice; this was called the ‘Meeting of Sun and Moon’ (Σύνοδος Ἡλίον Σελήνης) — a thing which had not happened for nineteen full years before and would not happen again for another nineteen.”Note 28

Odysseus, Murray notes, returned to Ithaca “just at the rising of that brightest star which heralds the light of the Daughter of Dawn” (Odyssey v 93). He rejoined his wife “on the twentieth year”; i.e., he came as soon as the twentieth year came, as soon as the nineteenth was complete (ψ 102, 170; ρ 327, β 175). He came at the new moon, on the day which the Athenians called “Old-and-New,” “when one month is waning and the next rising up” (τ 307, ξ 162). But this new moon was also the day of the Apollo Feast, or solstice festival of the sun (ν 156, ϕ 258), and the time was winter. Moreover, Odysseus had just 360 boars, of which one died every day (ξ 20); likewise, the cattle of the sun are in seven herds of fifty each, totaling 350. Odysseus goes under the world in the West, visits the realm of the dead, and comes up in the extreme East, “where the Daughter of Dawn has her dwellings and her dancing-floors and the Sun is uprising” (μ 3)Note 29 — whereas Penelope, as we all know, was sitting at home, weaving a web and unweaving, like the moon.

The nineteenth- and early twentieth-century scholars always liked to identify solar and lunar analogies in this way because they confirmed a point that was becoming clear in their time, which was that the imagery of our heritage of myth is in large part derived from the cosmological symbology of the Age of Bronze. But we now must add to this important insight the further realization that a fundamental idea of all the pagan religious disciplines, both of the Orient and of the Occident, during the period of which we are writing (first millennium b.c.), was that the inward turning of the mind (symbolized by the sunset) should culminate in a realization of an identity in esse of the individual (microcosm) and the universe (macrocosm), which, when achieved, would bring together in one order of act and realization the principles of eternity and time, sun and moon, male and female, Hermes and Aphrodite (Hermaphroditus), and the two serpents of the caduceus.

The image of the “Meeting of Sun and Moon” is everywhere symbolic of this instant, and the only unsolved questions in relation to its universality are: a) how far back it goes, b) where it first arose, and c) whether from the start it was read both psychologically and cosmologically.

In the Indian Kundalini yoga of the first millennium a.d., the two spiritual channels on either side of the central channel of the spine, up which the serpent power is supposed to be carried through a control of the mind and breath, are called the lunar and solar channels; and their relationship to the center is pictured precisely as the two serpents to the central staff in our Figure 1 — which is Hermes’ staff. In Figure 2, we see the meeting of sun and moon again in significant relation to the serpent and the axial staff, tree, or spine. The symbolism was known to Europe, China and Japan, the Aztecs and the Navaho: it is unlikely that it was unknown to the Greeks.

And so — to say the very least — the union of Odysseus and Penelope at the start of the twentieth year is to be seen as of somewhat greater interest than the lot of the merely patient Griselda. And to say just a little more: since Penelope is the only woman in the book who is not of a magical category, it is clear (to me, at least) that Odysseus’s meetings with Circe, Calypso, and Nausicaa represent psychological adventures in the mythic realm of the archetypes of the soul, where the male must experience the import of the female before he can meet her perfectly in life.

1. The first adventure of Odysseus, following his departure with twelve ships from the beaches of conquered Troy, was a pirate raid on Ismarus, a Thracian town. “I sacked their city and slew the people,” he reported of this act. “And from out the city we took their wives and much substance and divided them amongst us.”Note 30 The brutal deed was followed by a tempest sent by Zeus, by which the sails of the ships were torn to shreds. They were blown, thereafter, out of control, for nine days, and by that wind of God, carried beyond the bounds of the known world.

2. “On the tenth day,” as Odysseus related, “we set foot on the Land of the Lotus Eaters, who eat a flowery food.” But those of his men who ate of that fare had no more wish ever to return home (Lethe motif, forgetfulness: turn of the mind to the mythic, i.e., inward, realm); so that he dragged them weeping to their ships, bound them in the hulls, and rowed away.

3. Odysseus and his fleet were now in a mythic realm of difficult trials and passages, of which the first was to be the Land of the Cyclopes, “neither nigh at hand, nor yet afar off,” where the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, son of the god Poseidon (who, as we know, was the lord of tides and of the Two Queens, and the lord, furthermore, of Medusa), dwelt with his flocks in a cave.

“Yea, for he was a monstrous thing and fashioned marvelously, nor was he like to any man that lives by bread, but like a wooded peak of the towering hills, which stands out apart and alone from others.”

Odysseus, choosing twelve men, the best of his company, left his ships at shore and sallied to the vast cave. It was found stocked abundantly with cheeses, flocks of lambs and kids penned apart, milk pails, bowls of whey; and when the company had entered and was sitting to wait, expecting hospitality, the owner came in, shepherding his flocks. He bore a grievous weight of dry wood, which he cast down with a din inside the cave, so that in fear all fled to hide. Lifting a huge doorstone, such as two and twenty good four-wheeled wains could not have raised from the ground, he set this against the mouth of the cave, sat down, milked his ewes and goats, and beneath each placed her young, after which he kindled a fire and spied his guests.

Two were eaten that night for dinner, two the next morning for breakfast, and two the following night. (Six gone.) But the companions meanwhile had prepared a prodigious stake with which to bore out the Cyclops’ single eye; and when clever Odysseus, declaring his own name to be Noman, approached and offered the giant a skin of wine, Polyphemus, having drunk his fill, “lay back,” as we read, “with his great neck bent round, and sleep that conquers all men overcame him.” Wine and the fragments of the men’s flesh he had just eaten issued forth from his mouth, and he vomited, heavy with drink.

“Then,” declared Odysseus,

I thrust in that stake under the deep ashes, until it should grow hot, and I spake to my companions comfortable words, lest any should hang back from me in fear. But when that bar of olive wood was just about to catch fire in the flame, green though it was, and began to glow terribly, even then I came nigh, and drew it from the coals, and my fellows gathered about me, and some god breathed great courage into us. For their part they seized the bar of olive wood, that was sharpened at the point, and thrust it into his eye, while I from my place aloft turned it about, as when a man bores a ship’s beam with a drill while his fellows below spin it with a strap, which they hold at either end, and the auger runs round continually. Even so did we seize the fiery-pointed brand and whirled it round in his eye, and the blood flowed about the heated bar. And the breath of the flame singed his eyelids and brows all about, as the ball of the eye burnt away, and the roots thereof crackled in the flame. And as when a smith dips an ax or adze in chill water with a great hissing, when he would temper it — for hereby anon comes the strength of iron — even so did his eye hiss round the stake of olive. And he raised a great and terrible cry, that the rock rang around, and we fled away in fear, while he plucked forth from his eye the brand bedabbled in much blood. Then maddened with pain he cast it from him with his hands, and called with a loud voice on the Cyclopes, who dwelt about him in the caves along the windy heights. And they heard the cry and flocked together from every side, and gathering round the cave, called in to ask what ailed him. “What hath so distressed thee, Polyphemus, that thou criest thus aloud through the immortal night, and makest us sleepless? Surely no mortal driveth off thy flocks against thy will: surely none slayeth thyself by force or craft?”

And the strong Polyphemus spake to them again from out of the cave: “My friends, Noman is slaying me by guile, nor at all by force.”

And they answered and spake winged words: “If then no man is violently handling thee in thy solitude, it can in no wise be that thou shouldst escape the sickness sent by mighty Zeus. Nay, pray thou to thy father, the lord Poseidon.”

On this wise they spake and departed; and my heart within me laughed to see how my name and cunning counsel had beguiled them.

There remained, however, the problem of getting out of the blocked cave. The Cyclops, groaning, groping with his hands, lifted away the stone from the door, and himself then sat at the entry. And Odysseus cleverly lashed together three large rams of the flock, “well nurtured and thick of fleece, great and goodly, with wool as dark as violet.” And he prepared in all six triads of this kind. The middle ram of each set was to carry a man clinging beneath, while the side pair were to give protection. And as for himself, he laid hold of a goodly young ram, far the best of all, and curled beneath his shaggy belly; and as soon as early dawn shone forth, the nineteen rams, together with the flock, issued from the cave, bearing seven men.

To note: the symbolic penetration of the eye (“bull’s eye”: analogous to the sun door to the yonder world); the symbolic name Noman (self-divestiture at the passage to the yonder world: because he did not assert his secular character, his personal name and fame, Odysseus passed the cosmic threshold guardian, to enter a sphere of transpersonal forces, over which ego has no control); identification with the ram (symbolically a solar animal: compare Egyptian Amun).

4. The ships sailed to the Island of Aeolus, god of the wind (pneuma, spirit us, spirit): a floating island where the god and his twelve children, six daughters and six sons, abode in halls of bronze. “And behold, he gave his daughters to his sons to wife; and they feast evermore by their dear father and their kind mother, and dainties innumerable lie ready to their hands.”

“He gave me a wallet,” said Odysseus, “made of the hide of an ox nine seasons old, and therein he bound the ways of all the noisy winds. … And he made it fast in the hold of the ship with a shining silver thong, that not the faintest breath might escape. Then he sent forth the blast of the West Wind to blow for me, to bear our ships and ourselves upon our way.”

For nine days and nights the ships sailed on the winds proceeding from the wallet, and on the tenth were in sight of home. But while Odysseus slept, his men, to see what wealth was in the wallet, opened it, and a violent blast bore the flotilla back to Aeolus, who, however, refused, this time, to receive them.

One can recognize in this and the following adventure symbolic representations of a common psychological experience: first, elation (Jung’s term is “inflation”), then depression: the manic-depressive sequence common to sophomores and saints. Having achieved the first step — let us call it a threshold-crossing toward some sort of illumination — the company felt itself to be already at the goal; yet the enterprise had hardly begun. Phrased in terms of individual psychology: while Odysseus, the governing will, slept, his men, the ungoverned faculties, opened the wallet (the One Forbidden Thing). Phrased in sociological terms: the individual achievement was undone by the collective will. Or, putting the two sets of terms together: Odysseus had not yet released himself from identification with his group, group ideals, group judgments, etc.; but self-divestiture means group-divestiture as well. Hence, after enspirited social inflation, there followed:

5. Deflation, humiliation, the Dark Night of the Soul: “We sailed onward, stricken at heart. And the spirit of the men was spent beneath the grievous rowing by reason of our vain endeavor, for there was no more sign of a wafting wind.” And the seventh day, laboring thus, they arrived at the Land of the Laestrygons, a rich place of many flocks, where a scouting party went ashore.

They saw a town ahead and, before the town, fell in with a damsel drawing water. She was the daughter of the king and introduced them to her home, where they met her mother, huge as a mountain peak and loathly in their sight. The mother called the king, and he, also a giant, clutching up one of the company, readied him for eating, while the rest of the startled party ran. The king raising a war hoot, Laestrygons without number flocked from every side and, making for the shore, shattered with rocks all the ships but one.

6. Thus humbled, reduced, and battered, our great voyager, Noman, now was ready for his first fundamental encounter with the female principle, not in terms of arete, beauty, constancy, patience, or inspiration, but in terms to be dictated by Circe of the braided tresses, a nymph begotten upon a daughter of Ocean by the sim who gives light to all men.

The ship put in to Circe’s isle unknowing, and for two days and nights the men lay on the shore, consuming their hearts. But when the third day dawned, Odysseus, taking spear and sword, mounted a hill and spied smoke rising from the woodland beyond. Returning to his men, he slew a tall antlered stag, and they feasted, weeping for their lost companions. Then a party went off to reconnoiter, and in the forest glades they discovered the halls of Circe, built of polished stone.

And all around the palace mountain-bred wolves and lions were roaming, whom she herself had bewitched with evil drugs that she gave them. Yet the beasts did not set on the men, but lo, they ramped about them and fawned on them, wagging their long tails. And as when dogs fawn about their lord when he comes from the feast, for he always brings them the fragments that soothe their mood, even so the strong-clawed wolves and the lions fawned around them; but they were affrighted when they saw the strange and terrible creatures. So they stood at the outer gate of the fair-tressed goddess, and within they heard Circe singing in a sweet voice, as she fared to and fro before the great web imperishable, such as is the handiwork of goddesses, fine of woof and full of grace and splendor. Then Polites, a leader of men, the dearest to me and the trustiest of all my company first spake to them:

“Friends, forasmuch as there is one within that fares to and fro before a mighty web singing a sweet song, so that all the floor of the hall makes echo, a goddess she is or a woman; come quickly and cry aloud to her.”

He spake the word and they cried aloud and called to her. And straightway she came forth and opened the shining doors and bade them in, and all went with her in their heedlessness. But Eurylochus tarried behind, for he guessed that there was some treason. So she led them in and set them upon chairs and high seats, and made them a mess of cheese and barley-meal and yellow honey with Pramnian wine, and mixed harmful drugs with the food to make them utterly forget their own country. Now when she had given them the cup and they had drunk it off, presently she smote them with a wand, and in the styes of the swine she penned them. So they had the head and voice, the bristles and the shape of swine, but their mind abode even as of old. Thus were they penned there weeping, and Circe flung them acorns and mast and fruit of the cornel tree to eat, whereon wallowing swine do always batten.

Terrified Eurylochus having carried the news to the ship, Odysseus took up his great blade of bronze, slung his bow about him, and made off: but, as he proceeded, then did Hermes of the golden wand meet him on the way, in the likeness of a young man with the first down on his lip, the time when youth is most gracious, clasped his hand, and lo, gave him an herb of virtue, Moly the gods call it, to protect him against her magic, warned him of her procedure, and said: “When it shall be that Circe smites thee with her long wand, even then draw thou thy sharp sword from thy thigh, and spring on her, as one eager to slay her. And she will shrink away and be instant with thee to lie with her. Thenceforth disdain not thou the bed of the goddess, that she may deliver thy company and kindly entertain thee. But command her to swear a mighty oath by the blessed gods, that she will plan nought else of mischief to thine own hurt, lest she make thee a dastard and unmanned, when she hath thee naked.”

Hermes departed toward Olympus, up through the woodland isle, and Odysseus did as he was told. And when she had sworn and had done that oath, he at last went up into the beautiful bed of Circe, while her handmaids busied them in the halls, four maidens, born of the wells and of the woods and of the holy rivers that flow to the salt sea. The men who had been turned to swine were presently trotted in, and she went through their midst and anointed each one of them with another charm. “And so, from their limbs the bristles dropped away, wherewith the venom had erewhile clothed them that lady Circe gave them. And they became men again, younger than before they were, and goodlier far, and taller to behold.”

This “sacred marriage” of a hero who had 360 boars at home to a goddess who turns men into swine and back again, goodlier and taller than before, leads us to recall that in the mythology and rites of Demeter and Persephone of Eleusis and of the festival of the Anthesteria the pig was the sacrificial beast, representing a theme of death and rebirthNote 31 — as it is, also, in the Melanesian rites to which we have already referred. Odysseus on Circe’s isle, protected by the advice and power of Hermes, god of the caduceus, had passed to a context of initiations associated with the opposite side of the duplex Classical heritage from that represented by his earlier heroic sphere of life. In the Odyssey, as in the mythology of Melanesia, the goddess who in her terrible aspect is the cannibal ogress of the Underworld was in her benign aspect the guide and guardian to that realm and, as such, the giver of immortal life.

7. We learn next, therefore, that Circe has offered to guide Odysseus to the Underworld. “Son of Laertes, of the seed of Zeus, Odysseus of many devices,” she said, “ye must perform another journey and reach the dwelling of Hades and of dread Persephone, to seek to the spirit of Theban Tiresias, the blind soothsayer, whose wits abide steadfast. To him Persephone hath given judgment, even in death, that he alone should have understanding; but the other souls sweep shadowlike around.”

An extremely important point! Not all in the dwelling of Hades are mere shadows. Those who, like Tiresias, have seen and come into touch with the mystery of the two serpents and, in some sense at least, have been themselves both male and female, know the reality from both sides that each sex experiences shadowlike from its own side; and to that extent they have assimilated what is substantial of life and are, so, eternal.

There is a line of Sophocles, referring to the mysteries of Eleusis: “Thrice blessed are those among men, who, after beholding these rites, go down to Hades. Only for them is there life, all the rest will suffer an evil lot.”Note 32

This idea is basic to mature Classical thought and, in fact, is what distinguishes it from its echo in academic neo-Classicism. It is the expression of an organic synthesis of the two worlds of the Greek dual heritage and amounts, one might say, to an attainment of the second as well as first tree of the Garden — which to our sorry couple in the other school of virtue was denied.

Odysseus, following Circe’s lead, now sailed his craft to the limits of the world, where he came to the land and city of the Cimmerians, shrouded in mist and cloud, a land of eternal night. There he poured his offerings for the dead into a trench dug in the earth (in contrast to the upward direction of Olympian offerings) and the ghosts flocked from every side with a wondrous cry. He talked with those he knew: his mother, Tiresias, Phaedra, Procris, Ariadne, and many more, Agamemnon and Achilles. And he saw there, moreover, the Cretan King Minos, son of Zeus, holding in his hand a scepter and from his throne sentencing the dead.

Presently, taken with fear, however, lest Persephone should send to him the head of Medusa, the voyager, departing, returned to Circe, his mystagogue, and received from her the ultimate instruction.

8. The way and dangers of the way to the Island of the Sun: The dangers of the way were as follows: a) the Sirens, and b) the Clashing Rocks, or, by an alternate route, b´) Scylla and Charybdis. The first is symbolic of the allure of the beatitude of paradise, or, as the Indian mystics say, “the tasting of the juice”: accepting paradisial bliss as the end (the soul enjoying its object), instead of pressing through to non-dual, transcendent illumination. The other two represent alike the ultimate threshold of unitive mystical experience, leading past the pairs-of-opposites: a passage in experience beyond the categories of logic (A is not B, thou art not that), beyond all forms of perception, to a conscious participation in the consciousness inherent in all things. Odysseus chose the route between the pair-of-opposites Scylla and Charybdis and passed through.

However, on the Island of the Sun, to which they came, his men, with human appetite, slew, cooked, and ate a number of the cattle of the sun while Odysseus slept; and when they next set sail, “of a sudden came the shrilling West Wind with the rushing of a great tempest, and the blast snapped the two forestays of the mast.” The ship, foundering, sank with its entire company except Odysseus himself, who, clinging to a keel and mast, survived — alone at last.

And that was the climax of this spiritual voyage.

The analogy of this crisis to that of the first major threshold-crossing is manifest. And the contrast to the highest Indian ideal of illumination is apparent too. For had Odysseus been a sage of India, he would not now have found himself alone, floating at sea, on the way back to his wife Penelope, to put what he had learned into play in domestic life. He would have been united with the sun — Noman forever. And that, briefly, is the critical line between India and Greece, between the way of disengagement and of tragic engagement.

One can, in fact, compare the lesson of the two visits of Odysseus under the patronage of Circe, on the one hand to the Land of the Fathers and on the other to the Isle of the Sun, with “the two ways, of Smoke, and of Fire,” taught in the Indian Upaniṣads of c. 700–600 b.c.Note 33 In India, as in Greece, the tradition of these two ways had belonged originally not to the Aryan but to the pre-Aryan component of the compound heritages. Furthermore, it was communicated to the Brahmanical gods of the Aryan patriarchy (according to a myth preserved in the Kena Upaniṣad) by a goddess: Uma Haimavati, who was a most charming manifestation of the awesome Kālī.Note 34

In both Greece and India a dialogue had been permitted to occur between the two contrary orders of patriarchal and matriarchal thought, such as in the biblical tradition was deliberately suppressed in favor exclusively of the male. However, although in both Greece and India this interplay had been fostered, the results in the two provinces were not the same. In India the power of the goddess-mother finally prevailed to such a degree that the principle of masculine ego initiative was suppressed, even to the point of dissolving the will to individual life;Note 35 whereas in Greece the masculine will and ego not only held their own, but prospered in a manner that at that time was unique in the world: not in the way of the compulsive “I want” of childhood (which is the manner and concept of ego normal to the Orient), but in the way of a self-responsible intelligence, released from both “I want” and “thou shalt,” rationally regarding and responsibly judging the world of empirical facts, with the final aim not of serving gods but of developing and maturing man. For, as Karl Kerényi has well put it: “The Greek world is chiefly one of sunlight, though not the sun, but man, stands at its center.”Note 36

And so we come to the journey home, the return of Odysseus from the Underworld and the Island of the Sun.

9. Calypso’s Isle: Miraculously, Odysseus on his bit of flotsam came coursing back between Scylla and Charybdis and for nine days more was borne upon the sea, to be cast, on the tenth, upon the beaches of the isle Ogygia, of Calypso of the braided tresses. And the lovely goddess, dwelling there in a cave amid soft meadows, flowers, vines, and birds, singing with a sweet voice while faring to and fro before her loom, weaving with a shuttle of gold, restored him. He dwelt with her eight years (an octave, an eon), assimilating the lessons learned of the first nymph, Circe of the braided tresses. And when the time came, at last, for his departure, Zeus sent the guiding god Hermes to bid her speed her initiate on his way; which she did, reluctantly. He built a raft, and when she had bathed him and clothed him in fair attire, she watched him push out to sea and fade away.

10. But Poseidon, angry still for the blinding of his son, the Cyclops (we are returning, level by level, station by station, through the waters of this deep, dark night-sea of the soul) sent a blast of storm to wreck the raft, and, tossed again into the brine, Odysseus swam for two days and nights (Lucky for our athletic records that we do not take the myths of the Greeks as literally as we do the Bible!). He was presently flung ashore naked on the Isle of the Phaeacians. And there then followed the charming episode of the little princess, Nausicaa, with her company of maidens, coming to the beach, playing ball, the ball going into the water, the girls screaming, and the great man, prostrate in the bushes, waking to their cries. He appeared, holding a branch before him, and, after their moment of fright, the girls (the female principle again, but now in delightful childhood) gave him a cloth to wear and showed him the way to the palace.

That evening the great man from afar related to all, at dinner, the adventurers of his ten years; and the good and kind Phaeacians furnished both a ship and a fine crew to bear him home.

And they strewed for Odysseus a rug and a sheet of linen on the decks of the hollow ship in the hinder part thereof, that he might sleep sound. Then he too climbed aboard and laid him down in silence, while they sat upon the benches, every man in order, and unbound the hawser from the pierced stone. And so soon as they leant backwards and tossed the sea water with the oar blade, a deep sleep jell upon his eyelids, a sound sleep, very sweet, and next akin to death. …

11. “… and the goodly Odysseus awoke where he slept on his native land.”

Could it have been plainer said?

When, in the depths of the night, he had been approaching the palace of Circe, Hermes became Odysseus’s guide, and when the time arrived to leave Calypso, again Hermes was the messenger: the guide of souls, lord of the caduceus and of the goddesses three. Whereas now that the long voyager had emerged from the night sea of mythic forms and again was on the plane of waking life, with its world of social realities (domestic realities now), his guide was to be Athene. She appeared to him on the beach in the guise of a young man, “most delicate, such as are the sons of kings. And she was wearing a well-wrought mantle that fell in two folds about her shoulders, and beneath her smooth feet she had sandals bound, and a javelin was in her hands. And Odysseus rejoiced when he saw her, came over against her, and uttering his voice, spake to her winged words. …”

Athene had already caused his son Telemachus to go forth from his mother’s palace, which the visiting suitors suing for her hand, together with the maidservants, had been turning into a brothel and despoiling. She had come to the porch of the palace in the guise of a stranger; and the youth, who had been sitting with a heavy heart among the wooers, dreaming of his good father, saw the visitor and rose to greet her on the outer porch. After the dinner of that evening, she had advised him to go seek his father and had sent him on his way. She now, therefore, was to bring the two together.

And their meeting was to be in Odysseus’s swineherd’s hut.

So that, once again in this epic of departure, initiation, and return, we find that the archaic Eleusinian-Melanesian pig motif carries the great theme and frames the high moments of the merging of the two worlds of Eternity and Time, Death and Life, Father and Son.

The remaining episodes are as follows:

12. Odysseus’s arrival home: Transformed by Athene into the semblance of a beggar (Noman, still), the returned master of the house was recognized only by his dog and his old, old nurse. The latter spied above his knee the old scar of a gash received from the tusk of a boar. (Compare Adonis and the boar, Attis and the boar, and, in Ireland, Diarmuid and the boar.) Hushing the nurse, Odysseus watched for some time the shameless behavior of the suitors and maidservants in his house; whereafter, and at last:

13. Penelope, offering to marry any one of those present who could draw the powerful bow of her spouse, set up a target of twelve axes to be pierced. None of the suitors could even string the bow. Several tried manfully. The recently come beggar then offered and was mocked. However, as we read:

He already was handling the bow, turning it every way about, and proving it on this side and on that, lest the worms might have eaten the horns when the lord of the bow was away. … And Odysseus of many counsels had lifted the great bow and viewed it on every side, and even as when a man that is skilled in the lyre and in minstralsy, easily stretches a cord about a new peg, after tying at either end the twisted sheep-gut, even so Odysseus straightway bent the great bow, all without effort, and took it in his right hand and proved the bowstring, which rang sweetly at the touch, in tone like a swallow. Then great grief came upon the wooers, and the color of their countenance was changed, and Zeus thundered loud showing forth his tokens. And the steadfast goodly Odysseus was glad thereat, in that the son of deep-counselling Cronus had sent him a sign. Then he caught up a swift arrow which lay by his table, bare, but the other shafts were stored within the hollow quiver, those whereof the Achaeans were soon to taste. He took and laid it on the bridge of the bow, and held the notch and drew the string, even from the settle whereon he sat, and with straight aim shot the shaft and missed not one of the axes, beginning from the first ax-handle, and the bronze-weighted shaft passed clean through and out at the last.

The solar hero having thus demonstrated his passage of the twelve signs and his lordship of the palace, he proceeded masterfully to the shooting down of the suitors. “And they writhed with their feet for a little space, but for no long while.” After which, “Thy bed verily shall be ready,” said the wisely wifely Penelope. “Come tell me of thine ordeal. For methinks the day will come when I must learn it, and timely knowledge is no hurt.”

IV. The Polis

The leap from the dark age of Homer’s barbaric warrior kings to the day of luminous Athens — which in the fifth century b.c. had become suddenly present, like a rapidly opening flower, as the most promising new thing in the world — is comparable to a passage without transition from boyhood dream (life mythologically compelled) to self-governed young manhood. The mind, having dared at last to slay the jangling old gold-plated dragon “Thou shalt!” had begun to give forth, with a sense of the novelty, its own lion roar. And as the blazing roar of the rising sun scatters the herds of stars, so the new life blew out the old, not for Greece alone, but (when it will one day have learned to open its eyes) for the world.

“Our form of government does not enter into rivalry with the institutions of others,” declared Pericles (495?–429) in his celebrated funeral oration, extolling the life that the Athenians, in the Peloponnesian War, were at that time fighting to preserve.

We do not copy our neighbors, but are an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while the law secures equal justice to all alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognized; and when a citizen is in any way distinguished, he is preferred to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit. Neither is poverty a bar, but a man may benefit his country whatever be the obscurity of his condition. There is no exclusiveness in our public life, and in our private intercourse we are not suspicious of one another, nor angry with our neighbor if he does what he likes. …

And we have not forgotten to provide for our weary spirits many relaxations from toil; we have regular games and sacrifices throughout the year; at home the style of our life is refined; and the delight that we daily feel in all these things helps to banish melancholy. Because of the greatness of our city the fruits of the whole earth flow in upon us; so that we enjoy the goods of other countries as freely as our own.

Then, again, our military training is in many respects superior to that of our adversaries. Our city is thrown open to the world, and we never expel a foreigner or prevent him from seeing or learning anything of which the secret if revealed to an enemy might profit him. We rely not upon management or trickery, but upon our own hearts and hands. And in the manner of education, whereas they from early youth are always undergoing laborious exercises which are to make them brave, we live at ease, and yet are equally ready to face the perils that they face. …

An Athenian citizen does not neglect the state because he takes care of his own household; and even those of us who are engaged in business have a very fair idea of politics. We alone regard a man who takes no interest in public affairs, not as a harmless, but as a useless character; and if few of us are originators, we are all sound judges of a policy. The great impediment to action is, in our opinion, not discussion, but the want of that knowledge which is gained by discussion preparatory to action. For we have a peculiar power of thinking before we act and of acting too, whereas other men are courageous from ignorance but hesitate upon reflection. And they are surely esteemed the bravest spirits who, having the clearest sense both of the pains and pleasures of life, do not on that account shrink from danger.

In doing good, again, we are unlike others; we make our friends by conferring, not by receiving favors. Now he who confers a favor is the firmer friend, because he would fain by kindness keep alive the memory of an obligation; but the recipient is colder in his feelings, because he knows that in requiring another’s generosity he will not be winning gratitude but only paying a debt. We alone do good to our neighbors not upon calculation of interest, but in the confidence of freedom and in a frank and fearless spirit.Note 37