Chapter 7 — GREAT ROME: 500 b.c.–500 a.d.

I. The Celtic Province

Caesar’s Gallic wars, commencing in 58 b.c., opening Europe to the empire of Rome as Pompey’s wars had opened the Levant, broke the power of the Celts, who for centuries had been harassing the cities of the south. Spain they had entered and occupied in the fifth century b.c., as far as to Cadiz, and their seven-month siege of Rome itself in the year 390 b.c. had been but one of numerous inroads into Italy. Eastward, in 280 b.c., Thessaly was overrun, Greece invaded, Delphi sacked, and the following year the uplands of Asia Minor, which are known to this day as Galatia, became a center out of which war parties ranged even into Syria, until 232 b.c., when King Attalos I of Pergamon subdued the Galatians. The famous Hellenistic victory statue of the “Dying Gaul” depicts one of their handsome fair-haired warriors, wearing a typical Celtic torque or collar of gold.

The earliest matrix of the Celtic culture complex was the Alpine and South German area; and the centuries of its development were those of the early Iron Age in Europe, in two phases: 1. The Hallstatt Culture, c. 900-400 b.c., and 2. the La Tène, c. 550-15 b.c. The first was characterized at the outset by a gradual introduction of iron tools among bronze, fashioned by a class of itinerant smiths, who in later mythic lore appear as dangerous wizards — for instance, in the German legend of Weyland the Smith. The Arthurian theme of the sword drawn from the stone suggests the sense of magic inspired by their art of producing iron from its ore. Professor Mircea Eliade, in a fascinating study of the rites and myths of the Iron Age, has shown that a leading idea of this mythology was of the stone as a mother rock and the iron, the iron weapon, as her child, brought forth by the obstetric art of the forge.Note 1 Compare the savior Mithra born from a rock with a sword in his hand.

“Smiths and shamans are from the same nest,” declares a Yakut proverb cited by Eliade.Note 2 The allegedly indestructible body of the shaman who can walk on fire is analogous to the quality of a metal brought forth through the operation of fire. And the power of the smith at his fiery forge to produce such immortal “thunderbolt” matter from the crude rock of the earth is a miracle analogous to that of spiritual (viz. Mithraic or Buddhist) initiation, whereby the individual learns to identify himself with his own immortal part. In certain Buddhist temples of Japan there is to be seen the image of a strenuously meditating sage, Fudo, “Immovable” (Sanskrit, Acalanātha, “Lord Immovable”), seated, grim-faced, amidst a roaring blaze, holding a sword upright in his right hand with adamantine stability, like Mithra rising from the rock. And in the biblical idea of the remnant, which appeared first in Isaiah 10:21–22 (c. 740-700 b.c.), we have an application of the idea to the concept of the hero not as a clarified individual but as a purged people, a tried and true consensus, bearing the purpose of Yahweh through all time.

We may surmise, then, that the iron implements found among the earliest Hallstatt remains (c. 900 b.c.) must represent an entry into Europe of the ritual lore of drawing swords from stones, both in the smithy of the soul and in the fires of the forge. Hallstatt itself, the type site, is in Austria, about thirty miles southeast of Salzburg. Pigs, sheep, cattle, dogs, and the horse were the beasts domesticated. Log cabins and corduroy log roads testify to the crude physical circumstances; and the ornamentation of ceramic and metallic wares, weapons, horse and chariot harness, brooches, etcetera, was inelegant as well: lifeless, crudely symmetrical, geometrical, and stiff. The European peasant smock and a kind of pointed skullcap seem to have been the normal dress. And the usual funeral rite was cremation, though burial also was practiced. The earliest locus of the culture was Bohemia and South Germany, but it spread, in its final century, as far as to Spain and Brittany, Scandinavia and the British Isles, to furnish a base upon which the subsequent Celtic flowering of the La Tène period then appeared, c. 550-15 b.c.

The type site of La Tène, the brilliant second Iron Age of Central and Western Europe, is in Switzerland, some five miles from the town of Neuchâtel. Found here were a ten-spoked chariot wheel, three feet in diameter, bound with an iron tire; two yokes, each for a pair of horses; parts of a pack saddle, and numerous smaller equestrian trappings; oval shields, parts of a long bow, 270 spearheads, and 166 swords — several of the latter being in bronze sheaths, gracefully decorated in the typical high Celtic curvilinear style.

It was during this period that Rome was besieged by the Celts and Asia Minor was entered. The tide spread eastward into southern Russia, but the main trend was to the west, where it overflowed the earlier Hallstatt sites. In the late fifth century b.c. the Rhineland and Elbe areas were occupied, and in the early fourth the Channel was crossed, bearing the tribes known as Brythons to what now is England, and the Goidels to Ireland — who then, by invasion, entered Scotland, Cornwall, and Wales. Gaul and Spain also were occupied by tribal groups of the La Tène complex, and until Caesar, in the year 52 b.c., defeated Vercingetorix and the Helvetic confederacy, a vigorous common civilization flourished throughout the European north and west, bearing influences from Etruria, Greece, and the centers of the Near East, but, in the main, of a barbaric brilliance all its own.

“Throughout Gaul,” wrote Julius Caesar in the sixth book of his Gallic War,

there are two classes of persons of definite account and dignity. As for the common folk, they are treated almost as slaves, venturing nothing of themselves, never taken into counsel. The greater part of them, oppressed as they are by debt, by the heavy weight of tribute, or by the wrongs of the more powerful, commit themselves in slavery to the nobles, who have, in fact, the same rights over them as masters over slaves. Of the two classes above mentioned one consists of Druids, the other of Knights. The former are concerned with divine worship, the due performance of sacrifices, public and private, and the interpretation of ritual questions: a great number of young men gather about them for the sake of instruction and hold them in great honor. In fact, it is they who decide in most all disputes, public and private; and if any crime has been committed, or murder done, or there is any dispute about succession or boundaries, they also decide it, determining rewards and penalties: if any person or people does not abide by their decision, they ban such from sacrifice, which is their heaviest penalty. Those that are so banned are reckoned as impious and criminal; all men move out of their path and shun their approach and conversation, for fear they may get some harm from their contact, and no justice is done if they seek it, no distinction falls to their share.

Of all these Druids one is chief, who has the highest authority among them. At his death, either any other that is preeminent in position succeeds, or, if there be several of equal standing, they strive for the primacy by the vote of the Druids, or sometimes even with armed force. These Druids, at a certain time of the year, meet within the borders of the Carnutes,* whose territory is reckoned as the center of all Gaul, and sit in conclave in a consecrated spot. Thither assemble from every side all that have disputes, and they obey the decisions and judgments of the Druids. It is believed that their rule of life was discovered in Britain and transferred thence to Gaul; and today those who would study the subject more accurately journey, as a rule, to Britain to learn it.

The Druids usually hold aloof from war, and do not pay war taxes with the rest; they are excused from military service and exempt from all liabilities. Tempted by these great rewards, many young men assemble of their own motion to receive their training; many are sent by parents and relatives. Report says that in the schools of the Druids they learn by heart a great number of verses, and therefore some persons remain twenty years under training. And they do not think it proper to commit these utterances to writing, although in almost all other matters, in their private and public accounts, they make use of Greek letters. I believe that they have adopted the practice for two reasons — that they do not wish the rule to become common property, nor those who learn the rule to rely on writing and so neglect the cultivation of the memory; and, in fact, it does usually happen that the assistance of writing tends to relax the diligence of the action of the memory. The cardinal doctrine which they seek to teach is that souls do not die, but after death pass from one to another; and this belief, as fear of death is thereby cast aside, they hold to be the greatest incentive to valor. Besides this, they have many discussions concerning the stars and their movement, the size of the universe and of the earth, the order of nature, the strength and powers of the immortal gods, and hand down their lore to the young men.

The other class are the Knights. These, when there is occasion, upon the incidence of a war — and before Caesar’s coming this would happen well-nigh every year, in the sense that they would either be making attacks themselves or repelling such — are all engaged therein; and according to the importance of each of them in birth and resources, so is the number of liegemen and dependents that he has about him. This is the one form of influence and power known to them.

The whole nation of the Gauls is greatly devoted to ritual observances, and for that reason those who are smitten with the more grievous maladies and who are engaged in the perils of battle either sacrifice human victims or vow to do so, employing the Druids as ministers for such sacrifices. They believe, in effect, that, unless for a man’s life a man’s life be paid, the majesty of the immortal gods may not be appeased; and in public, as in private, life they observe an ordinance of sacrifices of the same kind. Others use figures of immense size, whose limbs, woven out of twigs, they fill with living men and set on fire, and the men perish in a sheet of flame. They believe that the execution of those who have been caught in the act of theft or robbery or some crime is the more pleasing to the immortals; but when the supply of such fails they resort to the execution even of the innocent.

Among the gods, they most worship Mercury.* There are numerous images of him; they declare him the inventor of all arts, the guide for every road and journey, and they deem him to have the greatest influence for all money-making and traffic. After him they set Apollo, Mars, Jupiter, and Minerva. Of these deities they have almost the same idea as all other nations: Apollo drives away diseases, Minerva supplies the first principles of arts and crafts, Jupiter holds die empire of heaven, Mars controls wars. To Mars, when they have determined on a decisive battle, they dedicate as a rule whatever spoil they may take. After a victory they sacrifice such living things as they have taken, and all the other effects they gather into one place. In many states heaps of such objects are to be seen piled up in hallowed spots, and it has not often happened that a man, in defiance of religious scruple, has dared to conceal such spoils in his house or to remove them from their place, and the most grievous punishment, with torture, is ordained for such an offense.

The Gauls affirm that they are all descended from a common father, Dis, and say that this is the tradition of the Druids. For that reason they determine all periods of time by the number, not of days, but of nights [because Dis is the lord of the underworld], and in their observance of birthdays and the beginnings of months and years day follows night. In the other ordinances of life the main difference between them and the rest of mankind is that they do not allow their own sons to approach them openly until they have grown to an age when they can bear the burden of military service, and they count it a disgrace for a son who is still in his boyhood to take his place publicly in the presence of his father.Note 3

There being no Celtic literature from the Hallstatt, La Tfene, or even Roman periods, we have to rely, first, on the accounts of Caesar, Strabo, Pliny, Diodorus Siculus, and a few others;Note 4 next, on certain monuments in stone from the Roman period; and finally — but best — an abundance of clues from the late Celtic literatures of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, to which the fairy lore of modern Ireland and the basically Celtic wonderland of Arthurian romance are to be added.

There is, for instance, a curious poetic charm supposed to have been recited by the chief poet, Amairgen, of the invading Goidelic Celts, when their ships scraped to beach on the Irish shore:

I am the wind that blows o’er the sea;

I am the wave of the deep;

I am the bull of seven battles;

I am the eagle on the rock;

I am a tear of the sun;

I am the fairest of plants;

I am a boar for courage;

I am a salmon in the water;

I am a lake in the plain;

I am the word of knowledge;

I am the head of the battle-dealing spear;

I am the god who fashions fire [= thought] in the head.

Who spreads light in the assembly on the mountain?*

Who foretells the ages of the moon?†

Who tells of the place where the sun rests?‡

Much has been written around this poem and certain others of its kind, suggesting affinities of Druidic thought with Hinduism, Pythagoreanism, and the later philosophy of the Irish Neoplatonist Scotus Erigena (d.c. 875 a.d.). The text of the charm is from the Irish “Book of Invasions” (Lebor Gabala), which, though preserved only in manuscripts of late medieval date, is a compendium of ancient matters put together no later than the eighth century a.d., and may contain material from as early, indeed, as the first arrivals in Ireland of the Goidels.Note 5 Caesar’s observation that the Celts were not afraid to die because they believed that they would live again has seemed to some to support the claim of this poem to antiquity, although others hold it to be a late composition of the high period of the courts of Tara and Cashel, the fourth and early fifth centuries a.d.Note 6

In either case, what the poem renders in the way of a world philosophy is a form rather of pan-wizardism than of developed mystical theology.Note 7 As one authority has put it, the comparison to be made is with “the bragging utterances of savage medicine-men”;Note 8 and another: “what is claimed for the poet is not so much the memory of past existences as the capacity to assume all shapes at will; this it is which puts him on a level with and enables him to overcome his superhuman adversaries.”Note 9 Such ideas are basic to shamanistic practice.Note 10 However, they can be readily developed into something higher, as in India, where the shaman became the yogi and the realization was attained of one’s self as the cosmic Self and therewith the essence of all things. Compare, for instance, with Amairgen’s chant the stanza already cited of the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad:

You are the dark-blue bird and the green parrot with red eyes.

You have the lightning as your child. You are the seasons and the seas.

Having no beginning, you abide with all-pervadingness,

Wherefrom all beings are born.

It is not possible to separate categorically the shaman from the mystic. Furthermore, from primitive shamanism to the highest orders of archaic and Oriental thought, where the microcosm and macrocosm unite and are transcended, there is not so great a step as from these to the way of thought of the man for whom God is without and apart. In fact, throughout the history of European myth, the tendency of the later mystic modes to unite with, and to find support in, the modes of both Celtic and Germanic myth has been decisive for the development of much that in our literature is of the highest spiritual strain.

The Irish mythological cycles tell of a number of waves of invaders entering Ireland from the Continent, of which the last was that of the people of the poet Amairgen, the so-called Sons of Mil, or Milesians. However, the diligent Christian monks to whose pens we owe the preservation of these texts were at pains to link their characters with the no less mythic figures of the Bible, and so what has come down to us, finally, is a kind of camelopard combined of two lineages of nonsense, which no amount of scholarship has yet been able to relate firmly to any portion of the actual history of mankind.

For example, the first arrivals in Ireland were Banba and two other daughters of Cain, who came by sea with a company of fifty women and three men, but then died there of the plague. Next, three fishermen arrived, who “with hardihood took possession of the island of Banba of Fair Women.” However, having returned home to fetch their wives, they perished in the Deluge.Note 11 The granddaughter of Noah, Cessair to wit, arrived with her father, her husband, and a third gentleman, Ladru, “the first dead man of Erin,” again with fifty damsels; but their ship was wrecked, and all but Finntain, her spouse, who survived for centuries, perished in the Deluge.Note 12

Banba, the reader must know, is the name of a goddess after whom Ireland itself is affectionately named; and the meaning of the word is “pig”; so that we are again on familiar ground: the island of a northern Circe. An Irish folktale recounted in Primitive Mythology tells of the daughter of the king of the Land of Youth, who appeared on earth as a maid with the head of a pig — which, however, could be kissed away.Note 13 Classical authors have written of islands in the Celtic fastnesses inhabited by priestesses. Strabo describes one near the mouth of the Loire, devoted to orgiastic cults, where no man was allowed to set foot, and another, near Britain, where the sacrifices resembled those to Demeter and Persephone at Samothrace.Note 14 The Roman geographer Mela (fl. c. 43 a.d.) tells of nine virgins on the tiny Isle of Sein, off Pont du Raz on the western coast of Brittany, who were possessed of marvelous powers and might be approached by those sailing especially to consult them.Note 15 Pigs figured prominently in the myths and rites of Demeter and Persephone, who themselves might appear as pigs.Note 16 The pig is linked, furthermore, to cults of the dead. Hence, in discussion of the Celtic isles of women, scholars have remarked that important pre-Celtic cemeteries have been excavated on the small Channel islands Alderney and Herm, as well as on Er Lanic in the Morbihan Gulf. “The graves,” states one authority, “take us back to pre-Celtic peoples and, therefore, encourage the belief that the island-cults represented a deeply rooted faith of the indigenous folk and were not necessarily of Celtic origin. Indeed, if we accept the stories of these communities of women, we can scarcely avoid admitting at the same time that they probably existed in addition to, and not as part of, the druidic religious system, and thus must have continued the observances of a pre-druidic faith.”Note 17

Following the antediluvian series of Banba, the company of fishermen, and the granddaughter of Noah, there came to the Emerald Isle a grotesque race called Fomorians, some of whom were footless; some had only one side, and all were descendants of the biblical Ham. They were giants, yet were defeated by the next arrivals, the race of Partholan from Spain, who were “no wiser one than the other.” All but one of these died of a plague, however — and it was that one, Tuan mac Caraill by name, who, surviving into Christian times, communicated the whole history of ancient Ireland to Saint Finnen.Note 18

Next to arrive were the people of Nemed, further descendants of Noah, who, like the Partholanians, came by way of Spain. They were subdued by the Fomorians, who had recovered from defeat and were governing the land from a tower of glass on Tory Island, off the northwest coast of Donegal. The Nemedians thereafter had to pay every year, on Halloween, two-thirds of the year’s harvest and of children born.

Now came the Firbolgs. A number of scholars have thought that these might represent the actual pre-Celtic population of Ireland and that the Fomorians were their gods. Among the latter were a god of war named Net, his dangerous grandson, Balor of the Evil Eye, and a god of knowledge, Elatha. The Firbolgs came from Greece, by way of Spain, like the builders of the megaliths, and were supposed to have been governed by a queen, Taltiu by name. According to the chronicles, they overcame the Fomorians but were themselves defeated by the race next to arrive, the shining Tuatha De Danann, the People (Tuatha) of the goddess Dana — who, in turn, were overcome by the last of this legendary series: the race of the poet Amairgen, the Milesians, who are thought by some to have been the Celts. Whereupon the conquered Tuatha withdrew from view into fairy hills, invisible as glass, where they dwell throughout Ireland to this day.

A few of the outstanding traits of the colorful mythology of the Tuatha De Danann may be noted here. The first is the prominence of a constellation of goddesses who in many ways are counterparts of both the great and lesser goddesses of Greece. Dana (genitive, Danann), who gives her name to the entire group, is called the mother of the gods and is the counterpart of Gaea. She is the Earth Mother, bestower of fruitfulness and abundance, and may have been one of the deities to whom human sacrifices were presented. Two hills in Kerry are called “the Paps of Anu,” Anu being a variant of her name associated with the verbal root an, “to nourish.”

Brigit or Brig (Irish brig, “power”; Welsh bri, “renown”), the patroness of poetry and knowledge, represents another aspect of the goddess and was the Celtic Minerva named by Caesar. The popular cult of Saint Brigit, which carried her worship into Christian times, was represented in Kildare by a sacred fire that was not to be approached by any male and was watched daily by nineteen vestal nuns in turn and on the twentieth day by the saint herself. Brigit, furthermore, was the giver of civilization. As Professor John A. MacCulloch remarks: “She must have originated in the period when the Celts worshiped goddesses rather than gods, and when knowledge — leechcraft, agriculture, inspiration — were women’s rather than men’s.”Note 19

The great father figure of this pantheon was the underworld god equated by Caesar with Dis, Pluto, or Hades. His Gallic name was Cemunnos, perhaps meaning “horned,” from cerna, “horn,”Note 20 and in the Irish epics he is called the Dagda, from dago devos, “the Good God.” In the Gallic monuments he is represented with horns or antlers and wearing a Celtic torque (as in the altar from Reims reproduced in Oriental Mythology, Figure 20), or with three heads, heavily bearded (as in a statue found at Condat, France); and he may carry on his arm a sack of abundance from which a river of grain proceeds.

On the monuments he is a figure of imposing mien. In the Irish epics, on the other hand, he is a kind of clown — and here we touch upon one of the most profound traits of all of the North European mythologies, whether Celtic or Germanic: for even the greatest of their gods and goddesses appear in manifestations that to sober eyes suggest no relation whatsoever to religion.

The Dagda was the father both of Banba and of Brigit and possessed, moreover, a caldron from which “no company ever went unthankful,” whose contents both restored the dead and produced poetic inspiration. Such a caldron suggests, however, derivation from a goddess; and the assignment to a god of the fatherhood of earlier goddesses also betrays the appropriation by a patriarchal deity of matriarchal themes — in the manner of the victories of Zeus, Apollo, and Perseus over the Bronze Age goddesses and priestesses of the Aegean.

We shall not be surprised to learn, therefore, that on a certain day the Dagda met and lay with the great war goddess Morrigan: the same who in later romance was to become the fateful sister of King Arthur, Fata Morgana, Morgan la Fée. He spied her when she was washing in a river, with one foot at Echumech in the north and the other at Loscuinn in the south. But he, that very day, had been challenged by the Fomorians to drink a certain broth. They had filled the prodigious caldron of their own king, Balor of the Evil Eye, with four times twenty gallons of milk, four times twenty of meal and fat, and had put in goats, sheep, and pigs besides: all of which they had boiled together and then poured into a vast hole in the ground. But the Dagda, a mighty god, took a ladle large enough for a man and woman to lie in the bowl of it, and he went on putting the full of the ladle into his mouth until the entire hole was empty; after which he put his hand down and scraped up all that remained amidst the earth and gravel.

Sleep then overcame the Dagda, and the Fomorians all were laughing; for his belly was the size of the caldron of a great house. But he presently got up, and, heavy as he was, made his way away. And indeed his dress was in no way sightly either; for he wore a cape to the hollow of his elbows and a brown coat, long before but short behind; the brogues on his feet were of horsehide, hair without; and he held in his hand a wheeled fork it would take eight men to carry, so that the track he left behind him was deep enough for the boundary ditch of a province. And it was while he was on the way home in this state that he chanced upon the Morrigan, the old Battle Crow, prodigious at her bath.Note 21

But as already the pillow colloquy of Queen Meave and her Celtic spouse Ailill has let us know, the pre-Celtic goddesses, though subjugated in Ireland, were by no means out of power. The grotesque epic of the war of the Brown Bull of Cooley, precipitated by the brazen action of Meave, when she sent for the bull and offered herself in part payment, is filled with a sense of the force of female powers over the destinies even of war — considerably in contrast to the spirit of the Greek epic, where, though Aphrodite and Helen were the true and deeper fates, the gods and heroes for the most part usurped the scene.

Cuchullin, for example, the Irish Achilles of this curious Irish Iliad, awoke one night to a terrible cry sounding in the north, so suddenly that he fell out of his bed and hit the ground like a sack. He rushed out of the east wing of his house without weapons, gaining the open air; and Emer, his wife, pursued with his armor and his garments. Across the great plain he ran, following the sound, and presently, hearing the rattle of a chariot from the loamy district of Culgaire, he saw before him a car harnessed with a chestnut horse.

The animal had but one leg, and the pole of the chariot passed through its body, so that the peg in front met the halter passing over its forehead, and within the car there sat a woman, eyebrows red, and with a crimson mantle around her. The mantle fell behind, between the wheels, so that it swept along the ground. And a big man walked beside. He too wore a crimson coat, and he carried on his back a forked staff, while he drove before him a cow.

“That cow,” said Cuchullin to the man, “is not pleased to be driven on by you.” To which the woman said: “She does not belong to you; nor to any of your associates or friends.” Cuchullin turned to her. “The cows of Ulster in general belong to me,” he said. She retorted: “You would give a decision, then, about the cow? You are taking too much on yourself, O Cuchullin!” He asked: “Why is it the woman who accosts me, and not the man?” She said: “It was not the man to whom you addressed yourself.” He answered: “Oh yes it was. But it was you who answered in his stead.” “He is Uar-gaeth-sceo Luachair-sceo,” said the woman.

“Well, to be sure,” Cuchullin said, “the length of the name is astonishing. Speak to me then yourself; for the fellow does not talk. What is your own name?”

“The woman to whom you are speaking,” said the man, “is called Faebor beg-beoil cuimdiuir folt scenb-gairit sceo uath.”

Said Cuchullin: “You are making a fool of me.” And he made a leap into the chariot, put his two feet on her shoulders and his spear on the parting of her hair. She warned: “Do not play your sharp weapons upon me.” “Then tell me your true name,” he said. “Go further off me then. I am a female satirist,” she answered. “And he is Daire son of Fiachna of Cuailgne. Moreover, I carry off this cow as reward for a poem that I made.” “Let us hear your poem,” said Cuchullin. “Only move further off,” she told him. “Your shaking over my head is not going to influence me at all.”

Cuchullin stepped away, until he stood between the two wheels, and she sang to him a song of insult. Whereat he prepared to leap again upon her; but horse, woman, chariot, man, and cow, all had disappeared. Then he perceived that she had transformed herself into a black bird, close by, on a branch.

“A dangerous enchanted woman you are!” said Cuchullin.

She answered: “Henceforth this place shall be called, the Enchanted Place.” And so it was, indeed.

Cuchullin said: “If I had only known it was you, we should not have parted thus.”

“Whatever you would have done,” she said, “it would have brought you ill luck.”

“You cannot harm me,” said Cuchullin.

“Certainly I can,” said she. And it was then that the old Battle Crow let him know what she held in store. “Indeed,” she said, “I am guarding now your deathbed, and shall be guarding it henceforth. This cow I have brought out from the Fairy Hill of Cruachan, so that she might breed by the bull of Daire son of Fiachna, which is named the Brown of Cuailgne. So long as her calf is not yet a year old, so long shall your life be. And it is this that is to be the cause of the Cattle Raid of Cuailgne.”

The two exchanged a lively series of threats, touching the battle ahead, in which he was to die, when, as she said, he would be in combat with a man as strong, victorious, dexterous, terrible, untiring, noble, great, and brave as himself, when she would become an eel and throw a noose around his feet in the ford, so that heavy odds would be against him.

“I swear,” said Cuchullin, “by the gods by whom Ultonians swear, that I will bruise you against a green stone of the ford.”

“I will become a gray wolf for you,” she said, “and take the flesh from your right hand as far as to your left arm.”

“I will encounter you with my spear,” he said, “until your left or right eye is forced out.”

“I will become a white red-eared cow,” she said, “and I will go into the pond beside the ford in which you are in combat, with a hundred white red-eared cows behind me. And I and all behind me will rush into the ford, and the Fair Play of Men that day shall be brought to a test, and your head shall be cut off from you.”

“Your right or your left leg,” he said, “I will break with a cast of my sling, and you shall never have any help from me, if you leave me not.”

Thereupon the Morrigan departed into the Fairy Hill of Cruachan in Connacht, and Cuchullin returned to his bed.Note 22

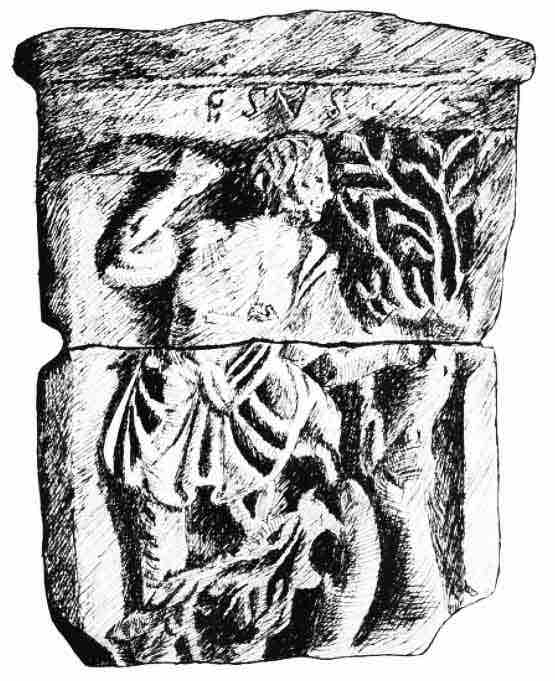

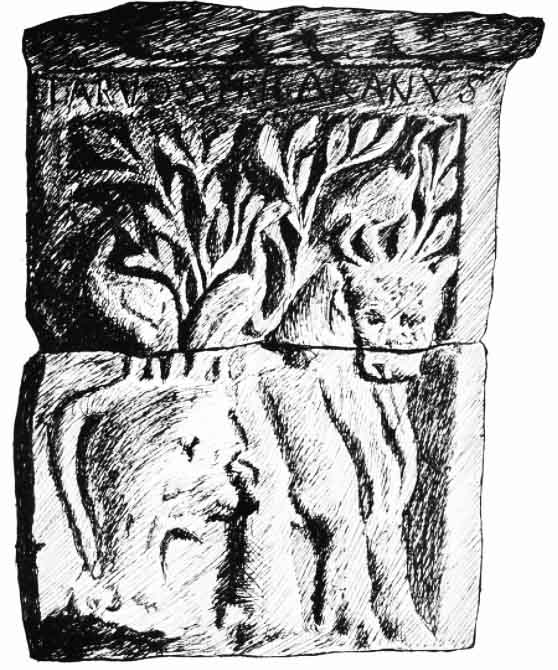

The goddess Morrigan, as an apparition of fate from the Fairy Forts of the Tuatha De Danann, is known as Badb, the crow or crane of battle, and, like the other goddesses of the Celtic, Germanic, Greek, and Roman worlds, she appears commonly in triplicate. Figures 27 and 28 are from two sides of a Celtic altar found in Paris at the site of Notre Dame, now preserved in the Cluny Museum. In the first is a figure in woodman’s clothes cutting down a tree, with his name, Esus, above. On the other is a bull beneath an extension of the tree that seems actually to be growing from his body, and with three cranes standing on his back. Above, we read the words, Tarvos Trigaranos, “The Bull with the Three Cranes.”

Figure 27. Esus

Figure 28. The Bull with Three Cranes

The great Celtic scholar of a generation past, H. D’Arbois de Jubainville, associated the bull of this Gaulish altar with the Brown Bull of the Irish epic, Esus with Cuchullin, the cranes with the goddess Morrigan, and the episode depicted with the passage we have just reviewed.Note 23 Professor MacCulloch suggests that the Brown Bull’s calf, whose life was to be the measure of the hero’s life, was the animal counterpart of Cuchullin; and since the Gallic Esus seems to have been a god of vegetation, to whom human sacrifices were hung on trees, the myth may have been associated with a bull sacrifice for the furtherance of vegetation.Note 24 Analogies with the Mithra mythology are indicated: the bull slain with vegetation springing from his flesh, and the sacrifice as an act performed by the human counterpart of the bull (see above, Figure 23). In the Gallo-Roman period, to which these altar panels belong, such cross-cultural analogies could not possibly have been missed. And so we now must recognize that, in the wildly grotesque hero deeds of this epic of the north, the goddess of the Fairy Hill, who appears variously as earth-mother, culture-giver, muse, and a goddess of fate and war, in human or in animal form, is ultimately analogous with the great goddesses of the nuclear Near East; while the Celtic warrior heroes, with Cuchullin as supreme example, carry in their mythic deeds motifs that have come down from the old Bronze Age serpent-son and consort of the Great Mother, Dumuzi-Tammuz.

II. Etruria

On the fair plain of Tuscany westward of the Apennines, situated between the Celts of the north and the rising power of Rome, were the twelve autonomous cities of the old Etruscan Confederation, symbolically centered around the sacred lake Bolsena. The origins of their culture date from the Villanova period, c. 1100–700 b.c., which overlaps the northern Hallstatt and represents in the south about the same level of development. A great number of curious funerary urns, buried close together in great fields, suggest not only an abiding concern for the dead, but also a certain idea of the purging and transforming power of fire in relation to the future state of the soul. Dr. Otto-Wilhelm von Vacano has interpreted the symbolism of these urns.

“When the bones,” he writes, “were gathered up from the funeral pyre as it ceased to glow, the remains of the ashes were all put into the cavity of the urn, to ensure that even the smallest piece of bone should be included.” Many of the urns were of human form and were even set upon ceramic thrones; others were in the forms of huts.

Underlying all this [von Vacano goes on to explain] is a belief that the dead will be transformed in the grave into beings of new and enhanced power, the idea that they are for the time being helpless as newborn babes, and must therefore in this interim period depend on the care of the survivors, while they are, as it were, germinating in the womb of the earth in order to sprout into a new life. …

Conceptions of this kind swept in waves over Europe at this time, and were also influential in Asia. Possibly their birthplace was the Caucasus or Persia. … In the sphere of influence of these early iron cultures the urn is a sort of hermetic vessel, in which a mysterious process of transformation and creation takes place. …

“One notable special feature in all this,” he then points out in a statement that corroborates very nicely our own observations in relation to the Celtic Iron Age,

is the belief in the purifying and transforming power of fire. Such conceptions have found expression in countless tales and legends of smiths, in the stories of the “little man who was burned till he became young,” the reviving cauldron boiling over the fire, the Medea-Pelias myth. On the other hand it is in the initiation rites of the shamans that we hear of a certain dream process whereby the novice is torn apart and cut to pieces by the spirit of one of his ancestors and his bones cleaned of all blood and flesh. Only his skeleton is preserved and is then clothed in new flesh and blood and thus transformed into a creature that is lord over time and space.Note 25

The high period of the confederation of the cities of Tuscany extended from c. 700 b.c. to the year 88 b.c., which they themselves regarded as their last. Repeatedly harried from the north by the barbaric La Tène Celts, and gradually undone from the south by the growing power and realistic politics of Rome, they remained in their time an enclave of provincial, colonial conservatism, preserving the sense of style and holiness of an age in full decline. Professor von Vacano has pointed out that the number twelve of the cities of their confederation was a holy, symbolic sum, determined by religious, not practical, considerations. “Like constellations round the Pole Star these hallowed places grouped themselves around the grove of the god Voltumna, the site of which has not yet been located but which lay in the territory of Bolsena, called Volsinii by the Romans and Velzna by the Etruscans themselves.”Note 26

Figure 29. The Driving of the Year Nail

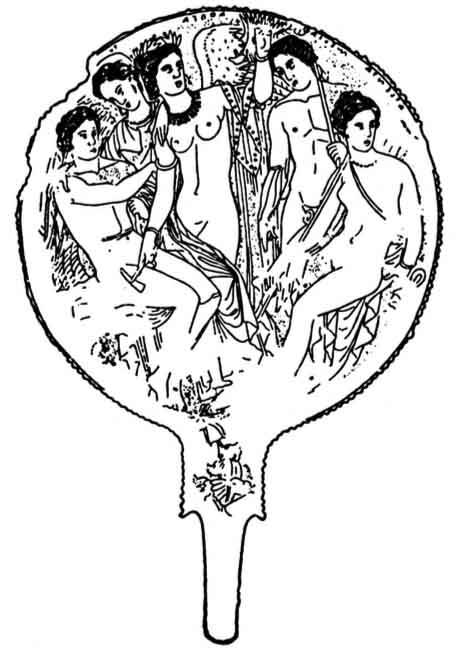

The god of this grove, Voltumna, was androgynous — beyond the pairs of opposites. Annually, at a festival celebrated in the grove amid the usual Classical festival events of athletic and artistic competition, the Year Nail was driven into the wall of the temple of the goddess Nortia (Fortuna), symbolizing the inevitability of fate.Note 27 Figure 29 is from the back of an Etruscan mirror, dating c. 320 b.c. The winged goddess in the center with a hammer in her right hand is holding the Year Nail in her left. Her name, inscribed above, is Athrpa, related to the Greek Atropos. And we note the boar’s head associated with the hand holding the nail, as well as the posture of the hammer, precisely at the genitals of the young man at the goddess’s right. He is Adonis (Etruscan Atune), who was gored, slain, and emasculated by the boar. The female at his side is Aphrodite, his beloved. And the opposite lovely couple, the writing tells, are Atalanta and Meleager, whose destiny, too, was sealed by a boar.

The old story goes that at the birth of Meleager the Fates appeared to his mother, and the first of them, Clotho, prophesied that he would be a man of noble spirit, the second, Lachesis, that he would be a hero, and the last, Atropos, that he would live as long as the log burning then on the hearth was not consumed. The mother, Althaia, springing from her bed, caught the brand from the fire and hid it in a chest. Meleager grew and became devoted to the hunt. But the goddess Artemis of the Wild Things, who had been offended when his father, King Oineus of Calydon, had failed to honor her with an offering at a great sacrificial feast, released a boar so mighty that no one could destroy it. In the words of the Roman poet Ovid, re-rendered by our own poet Horace Gregory:

Both blood and fire wheeled in his great eyes;

His neck was iron; his bristles rose like spears,

And when he grunted, milk-white foaming spittle

Boiled from his throat and steamed across his shoulders. …

Only an elephant from India

Could match the tusks he wore, and streams of lightning

Poured from wide lips, and when he smiled or sighed

All vines and grasses burnt beneath his breath.Note 28

The troubled King Oineus invited all the heroes of the lands of Greece to compete in the killing of this boar, and all the great names arrived: Castor and Pollux, Idas and Lynceus, Theseus, Admetus, Jason, Peleus, and many more. But of interest beyond all was the beautiful maid Atalanta, whose skill in many arts had already been exhibited when she had slain a pair of centaurs who had tried one day to ravish her, and when, at the funeral games of a certain prince, she had thrown in wrestling Peleus, the father of Achilles.

Many were killed by the boar in the course of that celebrated hunt. The first spear to graze the beast was Atalanta’s; Meleager’s felled him. But the youth had already been more gravely struck by the beauty of the fair huntress (who engaged in all these manly sports stripped naked like a male) than the boar had been by her lance; and when the beast was killed, he bestowed on her its hide.

This act was gravely resented by his uncles, the brothers of his mother, who wished the prize to be kept within the matriarchal family, and a brawl ensued of almost Irish magnitude, in the course of which the uncles tore the prize from the girl, whereupon Meleager slew them. And his mother, in a rage at the murder of her kin (but also, perhaps, rankled by the brazenness of the hoyden who had brought this all about), took the charred brand from its hiding and threw it into the fireplace, and her son died while still carving up the boar.Note 29

Once again the pig emerges focally in the symbolism of death, destiny, the underworld, and immortality! Of the personages represented on the mirror, Adonis, slain by a boar, was a god; Meleager, a prince. Both gods and men, that is to say, are governed by the power of the goddess, symbolized by the boar.

It is amazing, but now undeniable, that the vocabulary of symbol is to such an extent constant through the world that it must be recognized to represent a single pictorial script, through which realizations of a tremendum experienced through life are given statement. Apparent also is the fact that not only in higher cultures, but also among many of the priests and visionaries of the folk cultures, these symbols — or, as we so often say, “gods” — are not thought to be powers in themselves but are signs through which the powers of life and its revelations are recognized and released: powers of the soul as well as of the living world. Furthermore, as in the case of this Etruscan composition, the signs may be arranged to make fresh poetic statements concerning the great themes of ultimate concern; and from such a pictorial poem new waves of realization ripple out through the whole range of the world heritage of myth. So that a polymorphic, cross-cultural discourse can be recognized to have been in progress from perhaps the dawn of human culture, opening realizations of the import inherent both in the symbols themselves and in the mysteries of life and thought to which they bring the mind to accord.

The Disciplina Etrusca continued to a late date the spirit of the old Bronze Age cosmology of the ever-revolving, irreversible cycles; and the image of space also was of the orthodox traditions: four quarters and the points between, each presided over by a deity, with a ninth, supreme Tinia, the lord of heaven, whom the Romans equated with Jupiter. The kings of the separate cities, who were Tinia incarnate, each wore a cloak symbolizing heaven, embroidered with stars. Each colored his face red, bore a scepter topped by an eagle, and rode in a chariot drawn by white steeds. At each quarter of the moon the king displayed himself ceremonially to his people, offering sacrifices to learn the will of destiny; and on the field of battle he rode before his men. As among the Celts, the king may have been sacrificed at the expiration of a term of eight or twelve years. The magnitude of the tumuli of these kings and the luxury of the furnishings bear witness to a royal death cult, while the custom of the grove at Nemi, analyzed by Frazer in The Golden Bough, makes it almost certain that this cult retained to a late date the old rite of the regicide.

With the fall of the city of Veii to Rome in the year 396 b.c., the fate of Etruria was sealed. But though the military might and secular laws of the growing empire prevailed and the people of Etruria, in 88 b.c., were granted Roman citizenship, authority in priestly affairs nevertheless remained with the old Etruscan masters. As late as 408 a.d. Etruscan conjurers offered their advice and aid to the Romans, who were then being threatened by Alaric and his Goths, and there is even a report that Pope Innocent I, who was then bishop of the city, allowed them to give a public demonstration of their skill in the conjuring of lightning.Note 30

“This,” wrote the Roman Stoic Seneca, “is what distinguishes us from the Tuscans, masters in the observation of lightning. We think that lightning arises because clouds bump against each other; they on the other hand hold the belief that the clouds bump only in order that lightning may be caused. For as they connect everything with God they have the notion that lightning is not significant on account of its appearance as such, but only appears at all because it has to give divine signs.”Note 31

And so we pass, at last, from the ancient to the modern world.

III. The Augustan Age

Plutarch relates of Romulus and Remus that they were twins of a young virgin of the royal line of Aeneas, who had been forced by her father Amulius, the brother of King Numitor of Alba, to become a Vestal Virgin. Shortly following her assumption of the vow, she was found to be with child, and would have been buried alive had not her cousin, daughter of the king, pleaded for her life. Confined, she brought forth two boys of more than human size and beauty, whom her father, alarmed, turned over to a servant to be cast away. But the man put them in a small trough, which he carried to the river and left upon the bank; and the river, rising, bore the little boat downstream to a smooth place where a large wild fig tree grew. A she-wolf came and nursed them; a woodpecker brought them food: which two creatures, being esteemed holy to Mars, gave credit — as Plutarch states — to the mother’s claim that Mars, the god, had been their father; whereas some declared the father to have been her own father, Amulius, who had come to her disguised in armor as the god.

Following a period of being cared for by animals, the twins were discovered by Amulius’s swineherd, who brought them up in secret; though, as others tell, with the knowledge and assistance of the king: for it is said they went to school and were instructed well in letters. They were called Romulus and Remus from the word ruma, “dug” — of the wolf. And in their growing they proved brave. To their comrades and inferiors they were dear, but the king’s overseers they despised; and they engaged themselves in study, as well as in running, hunting, repelling thieves, and delivering the oppressed.

A quarrel arose between two cowherds, one of the king, the other of his brother, in the course of which Remus fell into the hands, first of the brother, then of the king. Romulus attacked the city, released his twin, slew the tyrant king and brother; and the twins, then bidding their mother farewell, departed to build a city of their own in the place where they had spent their infancy. A quarrel arose as to where this city should stand, which they agreed to settle by divination. But when Remus saw six vultures and Romulus claimed twelve, they came to blows and Remus was slain.

Plutarch reports that when Romulus set about founding Rome he sent for men of Tuscany to direct the ceremonies according to the Disciplina Etrusca.

First [Plutarch declares] they dug a circular trench around what is now the comitium, or Court of Assembly, and into this they solemnly threw the first fruits of all things sanctioned either by custom as good or by nature as necessary. Then, every man bearing a small portion of the earth of his native land, they all threw these in together. They call this trench, as they do the heavens, Mundus; and taking this as center, they described the city in a circle around it. Whereupon the founder, having fitted to a plow a brazen plowshare, and having yoked to it a bull and a cow, he himself drove a deep line of furrow, circumscribing the bounds, while the task of those that followed him was to see that whatever earth was thrown up should be turned inward, toward the city, and that no clod should lie outside. With this line they laid the course of the wall … and where they proposed to have a gate, they lifted the plow out of the ground and left a space; for which reason they regard the whole wall as holy, except where the gates are: for had they deemed these also sacred, they could not, without offense to religion, have given free entrance and exit to those necessities of life that are of themselves unclean.Note 32

Romulus stocked his city with women through his famous raid and rape of the Sabines, who became thereby first relatives, then citizens, of Rome. Other wars enlarged the realm. And presently he died, or rather disappeared — in a manner of interest to all who might like to think about the mythological air of the Roman Empire in the century of the birth and death, resurrection and disappearance of Christ.

For the life span of Plutarch, our biographer (c. 46–c. 120 a.d.), includes the years both of the mission of Saint Paul (d. c. 67 a.d.) and of the writing of the Gospels (c. 75–c. 120 a.d.); while the contrast of the Roman’s “modern” attitude toward miracles with the “religious” of the saints of the Levant is of relevance both to our present theme and to any general understanding of the scientific/religious schizophrenia of the modern Occidental “church.” Let me quote my author, word for word.

Plutarch has just told of the Roman conquest of Etruria and the fall of its chief city, Veii.

When Romulus [he continues] of his own accord then parted among his soldiers the lands that had been acquired by war and restored to the city of Veii the hostages he had taken, without asking the Roman senate either to consent or to approve, it seemed that he had put upon his senate a great affront. Consequently, on his sudden and strange disappearance a short time later, the senate fell under suspicion and calumny. Romulus disappeared on the Nones of July, as they call the month that was then Quintilis, leaving nothing of certainty to be related of his death except the time, as just mentioned; for on that day many ceremonies are still performed in representation of what happened.

Nor is this uncertainty to be thought strange, seeing that the manner of the death of Scipio Africanus, who died at his own home after supper, has been found capable neither of proof nor of disproof: for some say he died a natural death, being of sickly habit; others, that he poisoned himself; others again, that his enemies, breaking in upon him in the night, stifled him. Yet Scipio’s dead body lay open to be seen of all, and any one, from his own observation, might form his suspicions and conjectures, whereas Romulus, when he vanished, left neither the least part of his body, nor any remnant of his clothes to be seen.

So that some fancied, the senators, having fallen upon him in the temple of Vulcan, cut his body into pieces, and took each a part away in his bosom; others think his disappearance was neither in the temple of Vulcan, nor with the senators only by, but that it came to pass that, as he was haranguing the people without the city, near a place called the Goat’s Marsh, on a sudden strange and unaccountable disorders and alterations took place in the air; the face of the sun was darkened, and the day turned into night, and that, too, no quiet, peaceable night, but with terrible thunderings, and boisterous winds from all quarters; during which the common people dispersed and fled, but the senators kept close together. The tempest being over and the light breaking out, when the people gathered again, they missed and inquired for their king; the senators suffered them not to search, or busy themselves about the matter, but commanded them to honor and worship Romulus as one taken up to the gods, and about to be to them, in the place of a good prince, now a propitious god. The multitude, hearing this, went away believing and rejoicing in hopes of good things from him; but there were some, who, canvassing the matter in a hostile temper, accused and aspersed the patricians, as men that persuaded the people to believe ridiculous tales, when they themselves were the murderers of the king.

Things being in this disorder, one, they say, of the patricians, of noble family and approved good character, and a faithful and familiar friend of Romulus himself, having come with him from Alba, Julius Proculus by name, presented himself in the forum; and, taking a most sacred oath, protested before them all, that, as he was traveling on the road, he had seen Romulus coming to meet him, looking taller and comelier than ever, dressed in shining and flaming armor; and he, being affrighted at the apparition, said, “Why, O King, or for what purpose have you abandoned us to unjust and wicked surmises, and the whole city to bereavement and endless sorrow?” and that he made answer, “It pleased the gods, O Proculus, that we, who came from them, should remain so long a time amongst men as we did; and having built a city to be the greatest in the world for empire and glory, should again return to heaven. But farewell; and tell the Romans, that, by the exercise of temperance and fortitude, they shall attain the height of human power; we will be to you the propitious god Quirinus.” This seemed credible to the Romans, upon the honesty and oath of the relater, and indeed, too, there mingled with it a certain divine passion, some preternatural influence similar to possession by a divinity; nobody contradicted it, but, laying aside all jealousies and detractions, they prayed to Quirinus and saluted him as a god.Note 33

Who, on reading this passage, can have failed to recall that other meeting on the road, recounted in the twenty-fourth chapter of Luke?

That very day two of them were going to a village named Emmaus, about seven miles from Jerusalem, and talking with each other about all these things that had happened. While they were talking and discussing together, Jesus himself drew near and went with them. But their eyes were kept from recognizing him. And he said to them, “What is this conversation which you are holding with each other as you walk?” And they stood still, looking sad. Then one of them, named Cleopas, answered him, “Are you the only visitor to Jerusalem who does not know the things that have happened there in these days?” And he said to them, “What things?” And they said to him, “Concerning Jesus of Nazareth, who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, and how our chief priests and rulers delivered him up to be condemned to death, and crucified him. But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel. Yes, and besides all this, it is now the third day since this happened. Moreover, some women of our company amazed us. They were at the tomb early in the morning and did not find his body; and they came back saying that they had even seen a vision of angels, who said that he was alive. Some of those who were with us went to the tomb, and found it just as the women had said; but him they did not see.” And he said to them, “O foolish men, and slow to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Was it not necessary that Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself.

So they drew near to the village to which they were going. He appeared to be going further, but they constrained him, saying, “Stay with us, for it is toward evening and the day is now far spent.” So he went in to stay with them. When he was at table with them, he took the bread and blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. And their eyes were opened, and they recognized him; and he vanished out of their sight.Note 34

Let us now return to the other.

“This,” wrote the sober Roman, commenting on the apparition of Romulus,

resembles certain Greek fables of Aristeas the Proconnesian, and Cleomedes the Astypalaean; for they say Aristeas died in a fuller’s workshop, and his friends, coming to look for him, found his body vanished; and that some presently after, coming from abroad, said they met him traveling toward Croton. And that Cleomedes, being an extraordinarily strong and gigantic man, but also wild and mad, committed many desperate freaks; and at last, in a school-house, striking a pillar that sustained the roof with his fist, broke it in the middle, so that the house fell and destroyed the children in it; and being pursued, he fled into a great chest, and, shutting the lid to, held it so fast, that many men, with their united strength, could not force it open; afterwards, breaking the chest to pieces, they found no man in it alive or dead; in astonishment at which, they sent to consult the oracle at Delphi; to whom the prophetess made this answer:

“Of all the heroes, Cleomedes is last.”

They say, too, the body of Alcmena, as they were carrying her to her grave, vanished, and a stone was found lying on the bier. And many such improbabilities do your fabulous writers relate, deifying creatures naturally mortal; for though altogether to disown a divine nature in human virtue were impious and base, so again, to mix heaven with earth is ridiculous. Let us believe with Pindar, that

All human bodies yield to Death’s decree,

The soul survives to all eternity.

For that alone is derived from the gods, thence comes, and thither returns; not with the body, but when most disengaged and separated from it, and when most entirely pure and clean and free from flesh: for the most perfect soul, says Heraclitus, is a dry light, which flies out of the body as lightning breaks from a cloud; but that which is clogged and surfeited with body is like gross and humid incense, slow to kindle and ascend. We must not, therefore, contrary to nature, send the bodies, too, of good men to heaven; but we must really believe that, according to their divine nature and law, their virtue and their souls are translated out of men into heroes, out of heroes into demi-gods, after passing, as in the rite of initiation, through a final cleansing and sanctification, and so freeing themselves from all that pertains to mortality and sense, are thus, not by human decree, but really and according to right reason, elevated into gods and admitted thus to the greatest and most blessed perfection. …

It was in the fifty-fourth year of his age and the thirty-eighth of his reign that Romulus, they tell us, left the world.Note 35

The Romans employed two words to designate divine presences or powers, namely deus, which we generally translate “god,” and numen, for which we have no proper term. The root nv-, from which the latter is derived, means (curiously enough) “nod,” whence the connotation “command or will,” and then, “divine will or power, divine sway.”Note 36 Anthropologists have found for this Roman term a number of primitive counterparts; for instance, Melanesian mana, Dakotan wakon, Iroquoian orenda, and Algonquian manitu, all of which refer to an immanent magical force infecting certain phenomena. The “nod,” therefore, would have been experienced as coming not from without, but from within the object contemplated. Thus, whereas the Latin word deus, from the root div-, “shine,” is related to the Sanskrit deva, “god,” and suggests a being with defined personality, numen suggests, rather, the impulse of a will or force of no personal definition. We may recall here the Japanese sense of divine presences — kami — discussed in Oriental Mythology, under Shinto.Note 37 For, as in Japan, so in early Rome: the living universe was regarded, both in its great and in its lesser aspects, with a sense of wonder before its sheer existence. There is a pertinent passage in one of Seneca’s letters:

When you find yourself within a grove of exceptionally tall, old trees, whose interlocking boughs mysteriously shut out the view of the sky, the great height of the forest and the secrecy of the place together with a sense of awe before the dense impenetrable shades will awaken in you the belief in a god. And when a grotto has been hewn into the hollowed rock of a mountain, not by human hands but by the powers of nature, and to great depth, it pervades your soul with an awesome sense of the religious. We honor the sources of great rivers. Altars are raised where the sudden freshet of a stream breaks from below ground. Hot springs of steaming water inspire veneration. And many a pond has been sanctified because of its hidden situation or immeasurable depth.Note 38

Most important of the Roman numina were those of the home, where the leading celebrant was the pater familias. The family cult was concerned, first, with the mystery of its own continuity in time, as represented in rituals honoring the ancestors (manes) and in festivals of the general dead (parentes). The numina of the household also were revered: those of the larder (penates) and of household effects (lares). The guardian of the hearth, Vesta, was personified as a goddess, and that of the door, Janus, as a god. There was the idea also of a numen of the procreating power of each male, his genius, and of the conceiving and bearing power of the female, her juno. Genius and juno came into being and expired with the individual. They stood beside him in life as protecting spirits and could be represented as serpents. Under Greek influence the power of the juno later became developed into the goddess Juno, as the guardian of childbirth and motherhood, who was identified then with the Greek Hera. A series of numina of the various phases of the agricultural process also were celebrated: Sterculinius, the power effective in the fertilizing of the fields; Vervactor, the first plowing of the soil; Redarator, the second; Imporcitor, the third; Sator, the sowing of the field … and so on, to Messia, the reaping; Convector, the harvest home; Noduterensis, the threshing floor; Conditor, the storing of the grain in the barn; Tutilina, its resting there; and Promitor, its removal to the kitchen.Note 39

Other numina, of more constant presence, acquired more substantial character, as Jupiter, lord of the brilliant heavens and of storm, later identified with Zeus; Mars, the war god, equated with Ares; Neptune, the god of waters, identified with Poseidon; Faunus, the patron of animal life; Silvanus, god of the woods. Comparably, of the female forces, Ceres became identified with Demeter; Tellus Mater, with Gaea; Venus, originally a market goddess, with the Cyprian Aphrodite; and Fortuna with Moira. We hear too of Flora, goddess of flowers; Pomona, goddess of fruits; Carmenta, a goddess of springs and of birth; Mater Matuta, first a goddess of dawn, then of birth.Note 40

In the larger sphere of the cult of the state the counterpart of the pater familias was the king, originally a god-king. His palace was the chief sanctuary; his queen was his goddess spouse. We have remarked that in the home the numen of the hearth was the goddess Vesta. In the larger family of the state, the same holy principle was honored throughout the history of pagan Rome in a circular temple, where a pure flame was attended by six highly revered women. The flame was extinguished at the end of each year and relighted in the primitive way, with firesticks. The dress of the Vestal Virgins resembled the gown of a Roman bride; and on assuming her vow, the dedicated nun was solemnly clasped by the Pontifex Maximus, the chief priest of the city, who said to her: Te, Amata, capio! “My Beloved, I take possession of thee!” The two were symbolically man and wife. And if the Vestal broke her vow of chastity, she was buried alive.

The correspondence of this Vestal Fire context, in every single detail, with the rites of the regicide and relighting of the holy fire described in Primitive MythologyNote 41 could hardly be more exact. The mythology of such rites was of the neolithic and Bronze ages. Hence, although no written matter has come down to us from the earliest centuries of the city, it is evident that the same great mythology of the cycling eons, years, and days that shaped every one of the other civilizations of the world, shaped also that of Rome — both spatially, in the city plan itself, as described in the legend of Romulus’s foundation ceremony, and calendrically, in the disciplines of its life.

At an early date, the latter part of the sixth century b.c., an Etruscan royal house, the Tarquins of Tarquinia (now Cometo), governed Rome. They were expelled about 509 b.c., and it was then that the epochal process of the Hellenization of the Roman religion began, which brought its local, archaic customs into accord with the new humanism of the rapidly growing chief centers of civilization. In the decades of Etruscan rule temples had been constructed and cult images fashioned of stucco; but for stone, Rome had to wait for the coming of Greek artisans in the second century b.c., at which time the Sibylline Books also arrived from Cumae in the south: an ancient holy site, some twelve miles west of Naples, founded by the Greeks as early as the eighth century b.c., and celebrated particularly for its oracular cave, where the Sibyl prophesied of whom Virgil wrote in Eclogue IV. The old woman incumbent visited the city with a bundle of nine prophetic books, of which three were purchased and buried for safekeeping in the temple of Jove, where at intervals they were consulted until they perished in the fire of 82 b.c.

As Plutarch tells, their prophecies were of “many mirthless things … many revolutions and transportations of Greek cities, many appearances of barbarian armies and deaths of leading men.”Note 42 They seem also to have divided the history of the world into ages to which various metals and deities were assigned.Note 43 And, as we may judge from Virgil’s celebrated words, the Sibylline round, declining to its end, was to be followed — as everywhere in such mythic cycles — by a golden age of rebeginning.

Now is come [he wrote] the last age of the Cumaean prophecy: the great cycle of periods is born anew. Now returns the Maid, returns die reign of Saturn: now from high heaven descends a new generation. And O holy goddess of childbirth Lucina, do thou be gracious at that boy’s birth in whom the Iron Race shall begin to cease and the Golden to arise all over the world. …Note 44

This poem, with its wonderful Boy, was taken in the Christian Middle Ages to have been a prophecy of Christ, and Virgil was honored, therefore, as a kind of pagan prophet. His thought of the coming Golden Age somewhat resembles the eschatology of the Jewish Apocalyptic writers, and his dates, 70-19 b.c., fall perfectly within the period of the Essenes of Qumran. However, in the gentle Roman poem there is no tumult of any War of the Last Days. The image is of a return of the Golden Age in the natural course of an ever-revolving cycle, not the epochal passage in a “day of the Messiah” to an everlasting terminal state of the universe. And the Boy in question, finally, was not a Messiah of any kind, but a normal human child, born to a distinguished family of the poet’s acquaintance at a time that Virgil regarded, properly, as the dawn of a universal age of peace (for those willing to enjoy it) under the empire of Rome. Nor is the sense of Virgil’s imagery to be taken literally and concretely, but poetically, as a Classical figure of speech.

About the year 100 b.c. the Roman Pontifex Maximus, Q. Mucius Scaevola, in the spirit of a Stoic sage, proposed a theory of a threefold order of gods: the gods of poets, of philosophers, and of statesmen; of which the first two were unfit for the popular mind and only the second true. However, a fourth and far more potent order of gods than any of those of which he had taken thought was already becoming known to Rome in his day: those, namely, of the Near East, whose appeal was, in the Greek sense, neither poetic nor philosophic, and whose force, furthermore, would ultimately effect not the preservation but the undoing of the moral order of Rome and its civilization.

The first occasion for the introduction of these highly charged alien powers had occurred in the year 204 b.c., when the Carthaginian army of Hannibal was still a threat within Italy. Repeated storms and hail had produced the impression that the gods themselves, for some reason, were at odds with the people of Rome, and the Sibylline Books were consulted. Their reply was that the enemy would be expelled only when the cult of the Great Goddess of the Phrygian city of Pessinus was introduced into Rome. This Magna Mater was Cybele, the mother-bride of the ever-dying, ever-resurrected savior Attis; and these two were simply the local forms of the pair that we have come to know so well: Inanna and Dumuzi, Ishtar and Tammuz. In the high Etruscan age, as Figure 29 shows, the cognate myth of Aphrodite and her dead and restored lover Adonis had been introduced into Italy. Now, on the advice of the Sibylline Books, Cybele Magna Mater, under the aspect of a large black stone, was imported and set up in a temple on the Palatine. We have already commented on the influence of the Mithra cult within the empire. A third religion of this order, derived from Alexandria, was that of the now Hellenized Isis, and her spouse, now called Serapis (from the name Osiris-Apis). All these formerly local cults had in the Hellenistic age been syncretized with the related Greek traditions of the Dionysian, Orphic, and Pythagorean movements — to which a modicum of late Chaldean-Hellenistic astrology had been added, to form a compound of macro-microcosmic lore that was to remain dominant in the Occident, one way or another, until the science of the Renaissance undid the old cosmology of a geocentric universe and opened marvels beyond anything dreamed of by the sages of the ancient mystic ways.

Outstanding figures in this development were the Greek Stoic Posidonius, already mentioned (c. 135–50 b.c.), his eloquent pupil Cicero (106–43 b.c.), Cicero’s friend, Publius Nigidius Figulus (c. 98–45 b.c.), and then Virgil (70-19 b.c.), Ovid (40 b.c.-17 a.d.), Apollonius of Tyana (fl. first century a.d.), Plutarch (c. 46–120 a.d.), Ptolemy (fl. second century a.d.), and Plotinus (c. 205–270 a.d.). In the works of all these there is sounded a certain modern note; for the sciences of their time, like those of our own, were disclosing facts of the natural order that could not be absorbed by the old cosmologies, so that the problem of the day was to retain the substantial spiritual insights of the past even while pressing on to new horizons.

Perhaps the most lucid single instance of the manner in which the ancient lore was being translated into terms congenial to the new is to be seen in Cicero’s “Dream of Scipio Africanus the Younger,” with which he concluded the argument of his Republic. The youth whom he selected to be the subject of this work had lived c. 185–129 b.c. and was supposed to have seen his grandfather in vision, Scipio Africanus the Elder (237–183 b.c.), who many years before had invaded Africa and defeated Hannibal. The Elder is represented as revealing to his grandson, besides something of the future before him, a new spiritual view both of the universe and of man’s place within it.

“I fell into a deeper sleep than usual,” the youth is supposed to have reported; “and I thought that Africanus stood before me, taking the shape that was familiar to me from his bust rather than from his person.”

The psychological inflection is already interesting. The vision is subjectively disposed. We are not asked to believe in it as an actual case of revenance from the dead. The atmosphere is of poetic, not religious myth.

Africanus said: “How long will your thoughts be fixed upon the lowly earth? Do you not see what lofty regions you have entered?” And he pointed to the marvels of a universe of nine celestial spheres. “The outermost, heaven, contains all the rest,” he said, “and is itself the supreme God, holding and embracing within itself all the other spheres. In it are fixed the eternal revolving courses of the stars, and beneath it are seven other spheres, which revolve in the opposite direction to that of heaven.” Africanus named these in order: Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, and the Sun, Venus, Mercury, and the Moon. “Below the moon,” he said, “there is nothing but what is mortal and doomed to decay, except the souls given to men by the bounty of the gods, whereas above the moon all is eternal. And the ninth or central sphere, which is the earth, is immovable, lowest of all, and toward it all ponderable bodies are drawn by their own natural tendency downward.”

The cosmology is that of Hellenistic science, which was later systematized by Ptolemy and carried on to Dante. It is derived ultimately from the astrology of the ziggurat, but the earth has become a sphere poised in the midst of a sort of Chinese box of concentric spheres; not the flat disk of yore, surrounded by a cosmic sea.

Said the dreamer: “What is this loud and agreeable sound that fills my ears?” And the vision answered:

That is produced by the onward rush and motion of the spheres themselves; the intervals between them, though unequal, being exactly arranged in a fixed proportion, by an agreeable blending of high and low tones various harmonies are produced. For such mighty motions cannot be carried on so swiftly in silence; and Nature has provided that one extreme shall produce low tones while the other gives forth high. Therefore this uppermost sphere of heaven, which bears the stars, as it revolves more rapidly, produces a high, shrill tone, whereas the lowest revolving sphere, that of the moon, gives forth the lowest tone. For the earthly sphere, the ninth, remains ever motionless and stationary in its position in the center of the universe; but the other eight spheres, two of which move with the same velocity, produce seven different sounds — a number that is the key of almost everything.

Learned men, by imitating this harmony on stringed instruments and in song, have gained for themselves a return to this region, as others have obtained the same reward by devoting their brilliant intellects to divine pursuits during their earthly lives. Men’s ears, ever filled with this sound, have become deaf to it; for you have no duller sense than that of hearing. … But this mighty music, produced by the revolution of the whole universe at the highest speed, cannot be perceived by human ears, any more than you can look straight at the sun, your sense of sight being overpowered by its radiance.

The number theory of Pythagoras, in relation to the principle of harmony in the universe, in the arts, and in the soul, is here set forth in terms of the new image of the universe and a modern, secularized mode of life. The archaic order of the hieratic state with its castes, sacrifices, and all, and of the arts as serving largely to illuminate such a state, is of the past. The arts and those other “divine pursuits” of “brilliant intellects” here touched upon are conceived in Hellenized, humanistic terms. Yet nothing has been lost of the essence of the doctrine.

The apparition continued, referring now to the sphere of the earth, its poles, and its torrid and temperate zones.

You will notice [he remarked] that the earth is surrounded and encircled by certain zones, of which the two that are most widely separated, and are supported by the opposite poles of heaven, are held in icy bonds, while the central and broadest zone is scorched by the heat of the sun. Two zones are habitable. Of these, the southern (the footsteps of whose inhabitants are opposite to yours) has no connection with your zone. Examine this northern zone which you inhabit, and you will see what a small portion of it belongs to the Romans. For that whole territory which you hold, being narrow from north to south, and broader from east to west, is really only a small island surrounded by that sea which you on the earth call the Atlantic, the Great Sea, or the Ocean. Now you see how small it is in spite of its proud name!

In surprising contrast to all mythological arguments up to this time, the native land with its local value system and circle of horizon is here diminished, not augmented, in importance. The view is of a reasonable human intellect, aware of the magnitude of the world, and greeting, not resisting, the opening vistas to which the new science, politics, and possibilities of life were inviting it. Statecraft and politics now were to be of a secular, not pseudoreligious stamp; yet, as the following portions of the discourse show, neither statecraft nor the spirit of man was to suffer one whit thereby.

The spirit is the true self [said Africanus], not that bodily form which can be pointed to by the finger. Know, therefore, that you are a god, if a god be that which lives, feels, remembers, and foresees, and which rules, governs, and moves the body over which it is set, just as the supreme God above us rules this universe. And just as the eternal God moves the universe, which is partly mortal, so an immortal spirit moves the frail body. …

For that which is always in motion is eternal; but that which communicates motion to something else, but is itself moved by another force, necessarily ceases to live when this motion ends. Therefore, only that which moves itself never ceases its motion, because it never abandons itself; nay, it is the source and first cause of motion in all other things that are moved. But this first cause has itself no beginning, for everything originates from the first cause, while it can never originate from anything else: for that would not be a first cause which owed its origin to anything else. And since it never had a beginning, it will never have an end. …

Therefore, now that it is clear that what moves of itself is eternal, who can deny that this is the nature of spirits? For whatever is moved by an eternal impulse is spiritless; but whatever possesses a spirit is moved by an inner impulse of its own; for that is the peculiar nature and property of a spirit. And as a spirit is the only force that moves of itself, it surely has no beginning and is immortal. Use it, therefore, in the best pursuits!

We are brought thus to the question of the best pursuits for man, and the answer again is of a man of reason.

“The best pursuits,” said the old soldier statesman, “are those undertaken in defense of your native land. A spirit occupied and trained in such activities will have a swifter flight to this, its proper home and permanent abode. And this flight will be still more rapid if, while still confined in the body, it looks abroad, and, by contemplating what lies outside itself, detaches itself as much as it may from the body.”