CHAPTER 6

EVERYONE’S AFRAID OF

SOMETHING:

Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is the fear of long

words.

In a feeble attempt to impress his insult-prone father, Garrison had insisted on riding the bus alone. While Mrs. Feldman thought it was too dangerous for a thirteen-year-old boy to travel alone, Mr. Feldman pointedly said that the boy needed to adhere to the strict guidelines of both the NBA and NFL: “No Babies Allowed” and “No Freaking Losers.” These two tidbits, according to Mr. Feldman, were words of wisdom to live your life by, and he shared them with Garrison at least three times a day. He saw it as his parental duty to toughen the boy up, because success never came to babies or losers, on the field or in life.

Garrison savored the notion of a sports-acronym, insult-free summer while quietly reading his Baseball Today magazine on the bus. Mr. Masterson, a few rows behind Garrison, couldn’t help but watch the boy as he read. Next to him, Mrs. Masterson fought the desire to sleep, desperately trying to keep her eyes from closing. Every few seconds her eyelids would descend slowly, covering half her eyes, before the sharply dressed woman would snap back awake. As Mrs. Masterson roused back to consciousness, Mr. Masterson leaned in to whisper in his wife’s ear.

“Do you think that boy is heading to the place?”

“I can’t imagine any other reason for being on a bus in the Pitts at this ungodly hour,” Mrs. Masterson responded.

“He looks so normal,” Mr. Masterson continued while inspecting the blond boy’s exterior.

“Darling, fears don’t always manifest themselves in such overt manners like our Maddie,” Mrs. Masterson said as her eyelids once again descended.

“Quite right,” Mr. Masterson said, peering over at his veiled daughter.

Garrison, oblivious to the conversation behind him, continued reading and eating the tuna sandwich his mother had made for him. As he absorbed players’ batting averages, he heard the rattle of the bus crossing a metal grate. Instinctively, Garrison looked out his window. From the view, he could tell the bus was on a bridge. His palms sweated profusely while his tuna-filled stomach churned and cramped. Bridges usually span breadths of water, but not always.

Garrison prayed for a dry ravine or, better yet, that he could resist looking altogether. His anxiety increased rapidly, moving him closer to the window, directing his eyes downward. Garrison saw blue. And lots of it. There was, of course, a window and at least one hundred feet protecting Garrison from the water, but it didn’t matter. The unraveling of reason was instantaneous.

“No,” Garrison mumbled aloud.

Sweat patches formed on his face, dripping off his eyebrows, clouding his already blurred vision. Spots of light further obstructed his sight as panic arrested his lungs. Garrison’s wheezing caught the Mastersons’ attention, but before they could ask if he was all right, he screamed. His voice hit a decibel rarely heard outside of rock concerts.

“Wwwwwwaaaaaaattttteeeerrrr!”

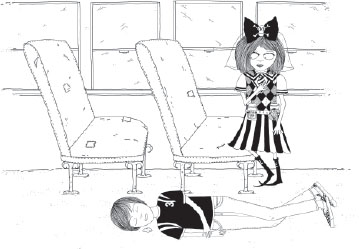

The surreal sensation of drowning took hold, forcing Garrison to gasp for air while flailing his arms. He was sure his face was a crimson mess. However, before he could check, it went black. The young boy fainted facedown in the aisle, and not a very clean aisle at that. His beautiful tanned face landed right between a putrid-looking green stain and an old piece of chewing gum.

Mr. Masterson ran to Garrison, checked his pulse, and dabbed his damp and dust-covered forehead. He promptly lifted Garrison onto a seat, placing his head across Mrs. Masterson’s lap. She gently brushed his moist hair off his face as Madeleine stared dreamily at the boy.

“Mummy, can we keep him?” Madeleine asked with the wide eyes of a burgeoning crush.

“Darling, little boys make terrible pets,” Mrs. Masterson offered with a wink.

“That’s not true at all, Mummy. They’re hypoallergenic, much easier than dogs,” Madeleine said cheekily, “and they almost never have fleas.”

Madeleine stepped closer to Garrison, pressing her veiled face against his flushed cheek. Starstruck and utterly enamored, she could have spent hours digesting the boy’s features, but the soft tickle of her netting stirred Garrison back to consciousness. As Garrison cracked his groggy eyes open, uncertainty and confusion quickly flashed across his face. He wasn’t sure what had happened, but there was a peculiar head pressed against his, and it was freaking him out.

“Ugh!” Garrison mumbled, and he jerked away from Madeleine.

Much as a police officer would his gun, Madeleine drew her repellent and prepared to shoot. Clearly, she had come to think of her spray as a viable means of protection against anything. Garrison stared curiously, unsure what to make of the girl with a veil and belt of repellents.

“I assume you’re also en route to,” Mrs. Masterson then whispered, “School of Fear.”

“Yeah. As you can tell, I don’t really like water,” Garrison mumbled while returning Madeleine’s intense gaze.

“I’m terrified of spiders, bugs, and all such creatures,” Madeleine shyly chimed in, attempting to relate.

Madeleine continued to stare, making Garrison even more uncomfortable and self-conscious than he already was. After all, two minutes ago, he’d woken up with his head in a stranger’s lap and a veiled face pressed against his own. All in all, it had been a rather uneasy series of events. Madeleine zealously maintained her gaze, prompting Garrison to divert his eyes. While taking in the empty bus, it occurred to him that he could simply return to his seat to escape the rampant awkwardness.

“Well, I better …” Garrison stumbled over his words as he started back to his seat.

“Do you have any other fears? Besides water?” Madeleine asked, desperate to keep the young man in conversation.

“Nope.”

“Oh, shame,” Madeleine said with disappointment before realizing she had said it aloud. “In London ‘shame’ means great,” she poorly covered.

“Darling?” Mrs. Masterson said with a confused look. “What on Earth are you talking about?”

“Mummy,” she said sternly, pleading with her eyes for her mother to go along with the ruse.

“It was a shame to meet you, young man,” Mrs. Masterson said with a mischievous expression.

Madeleine turned to her mother, cheeks scarlet red, and giggled.

While Garrison may have been embarrassed, he was also overwhelmingly relieved that his father was not present for his freak-out. He imagined the chorus of advice on life: NBA and NFL. In short, life doesn’t reward babies or losers, and considering what had just transpired, Garrison felt like both. He was so preoccupied by his feelings that he hardly noticed Madeleine watching him with the steady eye of an owl.

Madeleine was enraptured by Garrison’s tan complexion, which greatly differed from the pale boys of London. It wasn’t actually the boys’ fault, as the whole of the United Kingdom was under a cloud for much of the year. But at that moment, Madeleine decided that boys, like bread, were better toasted.

Close behind Madeleine and Garrison on Route 7 were Theo and his mother. Mr. Bartholomew had requested to join them on the trip but was flatly denied by Theo.

“Dad, if you come and there’s a car accident, you both could die and I could live. Then what? How would I go on? How would my brothers and sisters continue without the love and guidance of a parent? I mean really, Dad! How can you be so selfish?”

“Theo, nothing is going to happen to your mother or me. I promise.”

“You promise? Dad, you are so naïve. Life is unpredictable. I’m sorry, but we simply cannot take this chance. You will remain at home.”

“But, Theo,” Mr. Bartholomew grumbled.

“No buts! My decision is final,” Theo retorted.

“Okay, Theo. Whatever you say.”

Once safely on the road, Theo scrutinized his mother, looking for any perceptible signs of fatigue. It was much harder than he expected, for riding in cars had always made him drowsy. As he stared at his mother’s face, his eyelids weighed heavily, closing for seconds at a time.

His head bobbed back and forth as he blubbered, “What if you doze off and kill both of us?”

“Theo, I’m fine.”

“Do you know how many people die in sleep-related accidents each year?”

Before Theo could tell his mother that according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, drowsy driving was responsible for a minimum of 100,000 accidents each year, he drifted to sleep. This was just one of the oodles upon oodles of statistics Theo used to validate his many neuroses.

Only a couple miles behind Theo and his mother on Route 7 was the Punchalower family, who had hired a black town car to ferry them to Farmington. Mrs. Punchalower and Lulu tried to sleep but found it impossible with Mr. Punchalower’s rapid typing on his BlackBerry. It was nothing short of a miracle that the man hadn’t developed BBT (BlackBerry thumb), which causes the thumbs to freeze in a bent position. According to The Institute of BBT, if the BlackBerry trend continues, opposable thumbs could be obsolete within a century. Lulu held her throbbing left eye as she listened to her father type, all the while worrying that she would be forced to partake in “exercises” involving small, cramped spaces without windows.

“How do you know this camp isn’t going to torture me? Lock me in closets?” Lulu asked with an unsteady voice.

“Lucy Punchalower, I expect rational thinking from my children. Don’t disappoint me,” Mr. Punchalower said sternly without looking up from his BlackBerry.

“Do you guys know anyone who has gone to this strange school?” Lulu demanded.

“This institution comes highly recommended by Dr. Guinness. It’s extremely exclusive,” Mrs. Punchalower said with pride. “Your father and I expect you to do your best. Is that understood, young lady?”

“Whatever,” Lulu huffed with frustration.

“What did I tell you about that word?” Mrs. Punchalower asked angrily.

“Are you saying that I am not allowed to say the words ‘what’ and ‘ever’ or just when they’re together?” Lulu asked sarcastically.

“Any more lip and I will personally request they lock you in a closet,” Mr. Punchalower said without an ounce of humor.

Lulu closed her eyes in an attempt to block out her parents. She tuned out her father’s typing and focused on the sound of air pounding against the speeding car. While Lulu didn’t have any problem blocking out her parents, her fears were quite another story.

Questions stormed her mind, intensifying the thumping behind her eye. What if the bathroom didn’t have a window? What if her bedroom was a converted closet? What if there was an elevator? Lulu longed to be back in her bedroom in Providence. When Lulu stayed home, she forgot entirely that she was claustrophobic.

The Punchalower family drove down Farmington’s idyllic Main Street, a scene akin to a Norman Rockwell painting. The black town car stopped in front of the bus station at exactly 8:57 AM. As Lulu exited the car, she noticed a young boy hysterically crying and hugging his mother. It was a desperate, emotion-filled hug most often seen in dramatic love stories. Lulu was shocked by the display. As a byproduct of her rigid parents, Lulu never cried. In fact, she loathed crying altogether, prompting her to recoil as she passed the blubbering boy.

“Don’t leave me here!” Theo screamed. “They could be criminals!”

Lulu paused at the word “criminal,” realizing that the weeping boy had a point: she didn’t have a clue what she was walking into.