ERASMUS, THE SON of a priest, was a fastidious insomniac who spent much of his life in monasteries. Throughout the coming turmoil he remained an orthodox Catholic, never losing his love of Christ, the Gospels, and rites that comforted the masses. In his Colloquia familiaria he wrote: “If anything is in common use with Christians that is not repugnant to the Holy Scriptures, I observe it for this reason, that I may not offend other people.” Public controversy seemed to him an affront; though his doubts about clerical abuses were profound, he kept them to himself until he was well into his forties. “Piety,” he wrote in a private letter, “requires that we should sometimes conceal truth, that we should take care not to show it always, as if it did not matter when, where, or to whom we show it. … Perhaps we must admit with Plato that lies are useful to the people.”

These were reassuring words in the College of Cardinals, where, in 1509, Erasmus, then in his early forties, was a guest. His hosts yearned for serenity; they were weary of the bellicose Pope Julius II, who was forever invading this or that nearby duchy, on one pretext or another, and they had become troubled by the increase in indiscretions of humanists who were more aggressive and more outspoken than Erasmus. Among the first to arouse the Vatican’s displeasure had been Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, whose father, the ruler of a minor Italian principality, had hired tutors to give his precocious son a thorough humanist education.

The mature Pico developed a gift for combining the best elements from other philosophies with his own work, and his scholarship had been widely admired until he argued that the Hebrew Cabalistic doctrine, an esoteric Jewish mysticism, supported Christian theology. Greek and Latin scholarship were fashionable in Rome; but the suggestion of an affinity between Jewish thought and the Gospels was unwelcome. Pico drew up nine hundred theological, ethical, mathematical, and philosophical theses which Christianity had drawn from Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, and Latin sources and, in 1486, proposing to defend his position against any opponent, invited humanists from all over the continent to Rome to debate them. No one arrived. They weren’t allowed to enter the city. The pope had intervened. A papal commission denounced over a dozen of Pico’s theses as heretical, and he was ordered to publish an Apologia regretting his forbidden thoughts. Even after he had complied, he was warned of further trouble. Fleeing to France, he was arrested, briefly imprisoned, and, on his release—another sign of the age—was poisoned by his secretary.

Pico’s ordeal had been followed by the even more awkward Reuchlin affair. Johannes Reuchlin, a Bavarian humanist, had become fluent in Hebrew and taught it to his Tübingen students.

Then, in 1509, Johannes Pfefferkorn, a Dominican monk who was also a converted rabbi, published Judenspiegel (Mirror of the Jews), an anti-Semitic book proposing that all works in Hebrew, including the Talmud, be burned. Reuchlin, dismayed by the possibility of such desecration, formally protested to the emperor. Jewish scholarship should not be suppressed, he argued. Rather, two chairs in Hebrew should be established at every German university. Pfefferkorn, he wrote, was an anti-intellectual “ass.” Furious, the rabbi who had become a monk struck back with Handspiegel (Hand Mirror), accusing Reuchlin of being on the payroll of the Jews. Reuchlin’s riposte, Augenspiegel (Eyeglass), so outraged the Dominicans that the order, supported by the obscurantist clergy throughout Europe, lodged a charge of heresy against him with the tribunal of the Inquisition in Cologne. The controversy raged for six years. Five universities in France and Germany burned Reuchlin’s books, but in the end he was triumphant. Erasmus and Ulrich von Hutten, Maximilian’s new poet laureate, were among those who rallied to his side. An episcopal court acquitted him, Pfefferkorn’s fire was canceled, and the teaching of Hebrew spread, using Reuchlin’s grammar, Rudimentia Hebraica, as the universities’ basic text.

Because Erasmus was in Rome when this dispute broke out, his opinion was solicited. His mild reply—that he believed the issue could be solved by quiet compromise—endeared him to his hosts. They first urged him to prolong his stay, then offered him an ecclesiastical sinecure, suggesting that he settle among them permanently. Because of his eminence he had been courted in every other European capital. This seemed the ultimate opportunity, however, and he was at the point of accepting it when word arrived that the king of England had just died. Erasmus had known the new monarch, Henry VIII, since Henry’s boyhood. Both were ardent Catholics, and while he was debating his future a personal letter from Henry reached him, proposing that “you abandon all thought of settling elsewhere. Come to England, and assure yourself of a hearty welcome. You shall name your own terms; they shall be as liberal and honourable as you please.”

That decided Erasmus; he packed his bags. The offer was irresistible—for private reasons. In Rome, even if he became a cardinal, his manuscripts would be carefully scrutinized for possible heresy, but in England he would be free, protected by a powerful sovereign. This was important because there were certain unorthodox reflections Erasmus wanted to put on paper and then publish. Had his hosts at the Vatican known of them, it is likely that he would never have left the city. Given the morality of the time, it is even possible that his body, like so many thousands before it, would have been washed up by the waters of the Tiber.

IN REASONING that truth must sometimes be concealed in the name of piety, Erasmus had been completely sincere. He had, in fact, done exactly that with the sacred college. Safe in England, he intended to attack the entire Catholic superstructure. But he was no hypocrite. Nor, by his lights, was he guilty of treachery; betrayal as we know it was so common in that age that it carried few moral implications and aroused little resentment, even among sovereigns, prelates, and the learned. Furthermore, he was moved by a higher loyalty. He had always assigned absolute priority to principles and was baffled by those who didn’t. “We must not look to Erasmus for any realistic conception of human nature,” writes an intellectual historian. Brilliant, an accomplished linguist, familiar with all the capitals of Europe, he was nevertheless ignorant of, and indifferent to, the secular world.

He never pondered, for example, the dilemma which was troubling Machiavelli in these years: whether a government can remain in power if it practices the morality it preaches to its people. Nor had he ever coped with the vulgar tensions of everyday life—sexual tension (he was a celibate), for example, or the need to earn a living. Others had always handled money matters for him. It was no different in England. On his arrival there, the bishop of Rochester endowed him with $1,300 a year, a Kentish parish awarded him its annual revenues, and friends and admirers provided him with cash gifts. He was spared any concern about lodgings by Sir Thomas More, who, taking him into his own home, provided him with a servant. Erasmus scarcely noticed. He said: “My home is where I have my library.”

His, in short, was the peculiar naïveté of the isolated intellectual. As an ecclesiastic, he had an encyclopedic knowledge of clerical scandals, including the corruption in Rome. Other humanists had withdrawn from this squalor and found solace in the Scriptures. Not Erasmus; by force of reason, he believed, he could resolve the abuses of Catholicism and keep Christendom intact.

He miscalculated. Because the press as we know it had not even reached an embryonic stage, his knowledge of the world around him, like that of his contemporaries, was confined to what he saw, heard, was told, or read in letters or conversation. And because those around him were all members of the learned elite, he had no grasp of what the masses, the middle class, or most of the nobility knew and thought. His appeal was to his peers. Once he took his stand, they would find him immensely persuasive. But since his message would be incomprehensible to the lower clergy, where it counted, his appeals for reform would be impotent, his triumph literally academic.

Had that been the sum of it, he would have been unheard. But he was a man of many gifts, and one of them altered history. He possessed the extraordinary talent of making men laugh at the outrageous. Medieval men had known laughter—it is hard to see how they could have got through the day without it—but their expression of merriment had been the guffaw, mirth for its own sake; as Rabelais had written in his prologue to Gargantua, that kind of laughter is almost a man’s birthright (“Pour ce que rire est le propre de l’homme”). Erasmus, instead, wrote devastating satire. If the guffaw is a broadsword, satire is a rapier. As such, it always has a point. Erasmus’s points were missed by the common people, lay as well as clerical, but the coming religious revolution was not going to be a mass movement. It would be led by the upper and middle classes, which were gaining in literacy every day, and his brilliant thrusts had the unexpected effect of convulsing them and then arousing them.

In the beginning his intentions were very different. He meant to reach a small, elite audience which would be moved to act behind the scenes, within the existing framework of their faith. Instead his works became best-sellers. The first of them, written during his first year in England, was Encomium moriae (The Praise of Folly). Its Latinized Greek title was partly a pun on his host’s name, but moros was also Greek for “fool,” and moria for “folly.”

His postulate for the work was that life rewards absurdity at the expense of reason.

COMING FROM A MAN OF GOD, it was an astonishing volume. Some passages might have been written by a radical, atheistic German humanist, and had the author been a man of lesser renown, he would certainly have been condemned by the inquisitors. Being Erasmus, he laughed at them, daring them to “shout ‘heretic’ … the thunderbolt they always keep ready at a moment’s notice to terrify anyone to whom they are not favorably inclined.”

He opened his argument by declaring that the human race owed its very existence to folly, for without it no man would submit

Desiderius Erasmus (1466?–1536)

to lifelong monogamy and no woman to the trials of motherhood. Bravery was foolish; so were men who pursued learning; and so, he added slyly, were theologians, whom he mocked for defending the absurdity of original sin, for spreading the myth that “our Saviour was conceived in the Virgin’s womb,” for presuming, during holy communion, to “demonstrate, in the consecrated wafer … how one body can be in several places at the same time, and how Christ’s body in heaven differs from His body on the cross or in the sacrament.”

Next he went after the clergy, his targets running up the ecclesiastical scale from friars, monks, parish priests, inquisitors, to cardinals and popes. To him, curative shrines, miracles, and “such like bugbears of superstition” were “absurdities” which merely served as “a profitable trade, and [to] procure a comfortable income to such priests and friars as by this craft get their gain.” He mocked “the cheat of pardons and indulgences.” And “what,” he asked, “can be said bad enough of others who pretend that by the force of … magical charms, or by the fumbling over their beads in the rehearsal of such and such petitions (which some religious impostors invented, either for diversion, or, what is more likely, for advantage), they shall procure riches, honors, pleasure, long life, and lusty old age, nay, after death, a seat at the right hand of the Saviour?” As for the pontiffs, they had lost any resemblance to the Apostles in “their riches, honors, jurisdictions, offices, dispensations, licenses … ceremonies and tithes, excommunications and interdicts.” Erasmus, the intellectual, could find only one explanation for their success: the stupidity, ignorance, and gullibility of the faithful.

Encomium moriae was translated into a dozen languages. It enraged the priestly hierarchy. “You should know,” one of them wrote him, “that your Moria has excited a great disturbance even among those who were formerly your most devoted admirers.” But few academic writers, having tasted popular success, can turn away from it, and he was no exception. His faith in the wisdom of his cause was now confirmed. Indeed, his next satire, which appeared three years later, turned out to be even more startling. This time he assailed a specific pontiff, “the warrior pope,” Julius II.

Julius had been a strong pope and is remembered, deservedly, for his patronage of Michelangelo. But like all the pontiffs in that troubled age, he was more sinner than sinned against. He was also a Della Rovere—hot-tempered, flamboyant, and impetuous; Italians spoke of his terribilità (awesomeness). For five years he and his allies fought Venice. This campaign was successful; he recovered Bologna and Perugia, papal cities which the Venetians had seized during the misrule of the Borgia pope. In his second war, an attempt to expel the French from Italy, he was less fortunate, though by all accounts he cut a spectacular figure in combat, taking command at the front, white bearded, wearing helmet and mail, swinging his sword and always on horseback.

In satirizing this formidable pontiff Erasmus neither sought notoriety nor welcomed it; he had tried to deflect personal controversy by presenting his new work anonymously, but that was a doomed hope. He had shown it to too many colleagues. Sir Thomas More stripped his friend’s disguise away in a careless moment, and the responsibility was fixed. Within the Catholic hierarchy, resentment against the author was deepened by what, even today, would be considered questionable taste. The year before the presentation of Erasmus’s work in Paris—it was a dialogue—Julius had died. Thus the Church was actually in mourning for the victim of Iulius exclusus. Yet this did not dampen the hilarity of the Parisian audience, to whom it was first presented as a skit, or the multitude of readers in the months and years to come. In his onslaught on the papacy, Erasmus had struck a nerve; his followers thought the blow long overdue.

Julius is one character in the dialogue; Saint Peter is the other. Both stand at the gates of heaven, where the pope has presented himself for admittance. Peter won’t let him in. Beneath the applicant’s priestly cassock he notes “bloody armor” and a “body scarred with sins all over, breath loaded with wine, health broken by debauchery.” To him the waiting pontiff is “the emperor come back from hell.” What, he asks, has Julius “done for Christianity?”

Heatedly the applicant replies that he has “done more for the Church and Christ than any pope before me.” He cites examples: “I raised the revenue. I invented new offices and sold them. … I set all the princes of Europe by the ears. I tore up treaties, and kept great armies in the field. I covered Rome with palaces, and left five millions in the treasury behind me.”

To be sure, he concedes, “I had my misfortunes.” Some whore had afflicted him with “the French pox.” He had been accused of showing one of his sons favoritism. (“What?” asks Peter, astounded. “Popes with wives and children?” Julius, equally surprised, replies, “No, not wives, but why not children?”) Julius acknowledges that he had also been accused of simony and pederasty, but is evasive when asked if his plea is Not guilty, and after Peter, bearing in, inquires, “Is there no way of removing a wicked pope?” Julius snorts: “Absurd! Who can remove the highest authority of all? … He cannot be deposed for any crime whatsoever.” Peter asks: “Not for murder?” Julius replies: “Not for murder.” Under questioning he adds that a pontiff cannot lose his miter even if guilty of fornication, incest, simony, poisoning, parricide, and sacrilege. Peter concludes that a pope may be “the wickedest of men, yet safe from punishment.” The audience howled, knowing that was precisely Rome’s position.

There is no way Peter is going to let this man into paradise. Julius, apoplectic, tells him that the world has changed since the time “you starved as a pope, with a handful of poor hunted bishops about you.” When that line of reasoning is rejected, he threatens to excommunicate Peter, calling him “only a priest … a beggarly fisherman … a Jew.” Peter, unimpressed, replies, “If Satan needed a vicar he could find none fitter than you. … Fraud, usury, and cunning made you pope. … I brought heathen Rome to acknowledge Christ; you have made it heathen again. … With your treaties and your protocols, your armies and your victories, you had no time to read the Gospels.” Julius asks, “Then you won’t open the gates?” Peter firmly replies, “Sooner to anyone else than to such as you.” When the pontiff threatens to “take your place by storm,” Peter waves him off, astounded that “such a sink of iniquity can be honored merely because he bears the name of pope.”

LIKE ITS PREDECESSOR, Iulius exclusus was a succès fou; an Antwerp humanist wrote the author that it was “for sale everywhere here. Everyone is buying it, everyone is talking of it.” The Curia, alarmed now, urged Erasmus to lay his pen aside and spend the rest of his life in repentant piety. It was too late. That same year, 1514, saw the appearance of Familiarium colloquiorum formulae in the first of its several editions. Eventually the Colloquia familiaria, as it came to be called, became the bulkiest and most loosely organized of his works, and it is the most difficult to characterize. Essentially it was a miscellaneous collection of random thoughts; the full title, Forms of Familiar Conversations, by Erasmus of Rotterdam, Useful Not Only for Polishing a Boy’s Speech But for Building His Character, suggests his lack of a theme. Written in idiomatic, chatty Latin, these colloquies included a peculiar blessing to be bestowed on pregnant women—“Heaven grant that the burden you carry may have as easy an exit as it had an entry”—together with encouragement of circumcision, advice on the proper response when someone sneezed, paeans to piety, discouragement of the burning of heretics, and an endless, tedious colloquy between “The Young Man and the Harlot,” at the end of which the prostitute, perhaps exhausted, agrees to abandon her calling. There were off-color jokes, droll observations on the irrationality of human behavior, an endorsement of the institution of marriage, et cetera, et cetera.

Had that been all, his public, disappointed, would have left the work unread. But Erasmus had not finished savaging the Church and her clergy. An eighteenth-century Protestant translator later wrote that he knew of “no book fitter to read which does, in so delightful and instructing a manner, utterly overthrow almost all the Popish Opinions and Superstitions.” Certainly that seemed the author’s intent. He attacked priestly greed, the abuse of excommunication, miracles, fasting, relic-mongering, and lechery in the monasteries. Women were urged to keep a safe distance from “brawny, swill-bellied monks. … Chastity is more endangered in the cloister than out of it.”

Once more, however, he leveled his heaviest artillery on the Vatican. His contempt for Julius’s wars was venomous—“as if the Church had any enemies as pestilential as impious pontiffs who by their silence allow Christ to be forgotten, enchain [him] by their mercenary rules … and crucify him afresh by their scandalous life!” Depravity and corruption still outraged him: “As to these Supreme Pontiffs, who take the place of Christ,” he wrote, “were wisdom to descend upon them, it would inconvenience them! … It would lose them all that wealth and honor, all those possessions, triumphal progresses, offices, dispensations, tributes and indulgences,” requiring instead vigils, prayer, meditation, “and a thousand troublesome tasks of that sort.” In a private letter he wrote, “The monarchy of Rome, as it is now, is a pestilence to Christendom.”

In the first rush after publication, twenty-four thousand copies of the colloquies vanished from bookshops, and between then and midcentury only the Bible outsold it. There was a continuing demand for all his popular works. In 1520 an Oxford bookseller noted that a third of all the volumes he sold were written by Erasmus. Forty editions of Encomium moriae were published in the author’s lifetime, and as late as 1632 Milton found the book “in everyone’s hand” at Cambridge. It was this popularity, not the barbs themselves, which outraged those ecclesiastics who saw themselves as enforcers of the holy faith. Like every writer who has reached a large audience, he was dismissed for pandering to the masses, telling them what they wanted to hear, motivated solely by the base desire to make money. The impact of his successes on Christendom’s establishment may be judged by an edict from the Holy Roman emperor. Any teacher found using the Colloquia in a classroom, he ordered, was to be executed on the spot. Martin Luther agreed. “On my deathbed I shall forbid my sons to read Erasmus’ ‘Colloquies.’ ” But Luther was then still professor of biblical exegesis at Wittenberg, an eminent member of the Catholic establishment. Within three years he would change his mind and, with it, the history of Western civilization. And Erasmus, though he denied it on his own deathbed, had sounded the claxon of religious revolution.

OF COURSE, “the great apostasy,” as it came to be called in the Vatican, was no more the work of humanist scholars than it was an achievement of those godless descendants of Goths who had amused themselves by forging obscene propositions from the Blessed Virgin. The forces which fractured the unity of Christendom were enormously complex, and humanism, though a prime mover, was merely one current in the mighty wave which had just begun to form far out in the deep. One of its contributions was the revelation that art and learning had flourished before the birth of Jesus, when, it had been thought, such accomplishments were impossible. But men also wondered why God had allowed the triumph of the Muslims and the fall of Constantinople. And explorers returning from Asia and the Western Hemisphere reported thriving cultures which had either rejected Christ or never heard of him, thus discrediting those European Christian leaders who had held that belief in the savior was universal. It was an omen that Marguerite of Angoulême, the lovely Perle des Valois, sister of the king of France and herself queen of Navarre, became a skeptic. Once a woman of ardent faith, she now became a lapsed Catholic. In Le miroir de I’âme pécheresse, she acknowledged that she despised the religious orders, approved of attacks on the pope, thought God cruel, and doubted the Scriptures. Marguerite was accused of heresy before the Sorbonne, and a monk told his flock she should be sewn in a sack and flung into the Seine. As the sister of the French king she was never in peril, however; he adored her, and her championing of sexual freedom had enhanced her popularity in France.

The Vatican, with its population of bastards, was in no position to censure an advocate of infidelity. Marguerite’s only real threat to Catholicism was her subsequent role as an accomplice of its enemies; she later provided sanctuary for fugitives from heresimach posses. One of them was John Calvin. It is instructive to note that Calvin was an ingrate. He rebuked his protectress for including, as guests of her court, Bonaventure Desperiers and Étienne Dolet, skeptics who mocked Catholics and Protestants alike. The dismal truth is that the new Christians would turn out to be at least as bigoted as the old.

However, their clergy were to prove neither corrupt nor depraved, and this, in that age, was refreshing. At a time when homicide, thievery, rape, and assassination reached shocking heights, loyal Catholics were most deeply distressed by the abuses of their own clergymen. Many of the clergy agreed. Abbot Johannes Trithemius of Sponheim condemned his own monks: “The whole day is spent in filthy talk; their whole time is given to play and gluttony. … They neither fear nor love God; they have no thought of the life to come, preferring their fleshly lusts to the needs of the soul. … They scorn the vow of poverty, know not that of chastity, revile that of obedience. … The smoke of their filth ascends all around.” Another monk noted that “many convents … differ little from public brothels.” According to Durant, Guy Jouenneaux, a papal emissary sent to inspect the Benedictine monasteries of France in 1503, described the monks as foulmouthed gamblers and lechers who “live the life of Bacchanals” and “are more worldly than the mere worldling. … Were I minded to relate all those things that have come under my own eyes, I should make too long a tale of it.”

In England Archbishop (later Cardinal) John Morton accused Abbot William of St. Albans of “simony, usury, embezzlement and living publicly and continuously with harlots and mistresses within the precincts of the monastery and without,” and accused the country’s monks of leading “a life of lasciviousness … nay, of defiling the holy places, even the very churches of God, by infamous intercourse with nuns,” making a neighborhood priory “a public brothel.” The bishop of Torcello wrote: “The morals of the clergy are corrupt; they have become an offense to the laity.”

The public perception of the priesthood was in fact appalling. Eustace Chapuys, Charles V’s ambassador in England, wrote the emperor: “Nearly all the people hate the priests.” A Cambridge professor observed that “Englishmen, if called monk, priest, or clerk, felt bitterly insulted.” Everywhere, wrote William Durand, bishop of Mende, the Church “is in ill repute, and all cry and publish it abroad that within her bosom all men, from the greatest even unto the least, have set their hearts upon covetousness. … That the whole Christian folk take from the clergy pernicious examples of gluttony is clear and notorious, since the clergy feast more luxuriously … than princes and kings.” In Vienna the priesthood had once been the objective of ambitious youths. But now, on the eve of the religious revolt, it had attracted no recruits for twenty years.

In his fourteen-volume History of the Popes, Ludwig Pastor concludes that it was virtually impossible to exaggerate the “contempt and hatred of the laity for the degenerate clergy.” Philip Hughes, historian of the Reformation in England, found that in 1514, when the chancellor of the bishop of London was accused of murdering a heretic, the bishop asked Cardinal Wolsey to prevent a trial by jury because Londoners were “so maliciously set in favor of heretical pravity that they will … condemn my clerk, though he were as innocent as Abel.” Even Pope Leo, who, one would have thought, might have felt some responsibility for scandals committed in the name of the Church, observed in 1516, “The lack of rule in the monasteries of France and the immodest life of the monks have come to such a pitch that neither kings, princes, nor the faithful have any respect for them.”

Priests by the thousands found it impossible to live in celibacy. Their solutions varied. In London it was not unknown for women entering the confessional box to be offered absolution in exchange for awkward, cramped intercourse on the spot. In Norfolk, Ripton, and Lambeth, 23 percent of the men indicted for sex crimes against women were clerics, though they constituted less than 2 percent of the population. The most common solution for men unable to bear the strain of continence was to take a mistress. Virtually all German priests kept women. The Roman clergy had a reputation for promiscuity, “but it is a mistake,” writes Pastor, “to assume that the corruption of the clergy was worse in Rome than elsewhere; there is documentary evidence of the immorality of the priests in almost every town in the Italian peninsula. … No wonder, as contemporary writers sadly testify, the influence of the clergy had declined, and in many places hardly any respect was shown for the priesthood.”

There was trouble in the convents, too. The problem seems to have been especially distressing in England. In 1520 eight nunneries there were closed, one because of “the dissolute disposition and incontinence of the religious women of the house, by reason of the vicinity of Cambridge University.” After an examination of twenty-one convents in the diocese of Lincoln, fourteen were blacklisted for “lack of discipline or devotion.” In several, nuns had been found who had been made pregnant by priests. Two reports told of prioresses living in adultery. A diocesan commission filed a separate account of one abbess who had presented a local blacksmith with three sons.

The failure of pontiffs to set a good example was heavily blamed. Egidio of Viterbo, general of the Augustinians, summed up Pope Alexander’s Rome in nine words: “No law, no divinity; Gold, force and Venus rule.” Guicciardini wrote: “Reverence for the Papacy has been utterly lost in the hearts of men.” In 1513 Machiavelli charged that there could be no greater proof of papal “decadence than the fact that the nearer people are to the Roman Church, the head of their religion, the less religious they are. And whoever examines the principles on which that religion is founded, and sees how widely different from those principles its present practice and application are, will judge that her ruin or chastisement is near at hand.”

IT WAS PRECISELY four years away, and the spark which ignited it was the sale of indulgences—specifically, the conduct of the quaestiarii, or pardoners, commissioned to distribute them, and the avarice of the papacy. Thomas Gascoigne, chancellor of Oxford, noted in 1450 that “sinners say nowadays: “I care not how many evils I do in God’s sight, for I can easily get plenary remission of all guilt and penalty by an absolution and indulgence granted me by the pope, whose written grant I have bought for four or six pence.” The “indulgence-mongers,” as Gascoigne scornfully called the quaestiarii in his account, “wander all over the country, and give a letter of pardon, sometimes for two pence, sometimes for a draught of wine or beer … or even for the hire of a harlot, or for carnal love.”

John Colet, dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in the early sixteenth century, concluded that the commercialization of indulgences had transformed the Church into a “money machine.” He quoted Isaiah: “The faithful city is become a harlot”—no one could doubt which city he meant—and then Jeremiah: “She hath committed fornication with many lovers. … She hath conceived many seeds of iniquity, and daily bringeth forth the foulest of offspring.” He said, “Covetousness also … has so taken possession of the hearts of all priests … that nowadays we are blind to everything but that alone which seems able to bring us gain.” In effect, the practice of indulgences was a form of religious taxation, and its weight bore heavily on those who could least afford it. Informed Christians deeply resented the gulf between Europe’s hungry masses and Rome’s greed. In 1502 a procurer-general of the Parlement estimated that the Catholic hierarchy owned 75 percent of all the money in France; twenty years later, when the Diet of Nuremberg drew up its Centum Gravamina—Hundred Grievances—the Church was credited with owning 50 percent of the wealth in Germany.

Peter and Saul (later Paul) had lived in penury. The popes in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries lived like Roman emperors. They were the wealthiest men in the world, and they and their cardinals further enriched themselves by selling holy offices. An ecclesiastical appointee had to send the Curia half his income during the first year of his appointment, and a tenth of it each year thereafter. Archbishops paid huge lump sums for their pallia, the white bands which served as the insignia of their rank. When Catholic officeholders died, all their personal possessions went to Rome. Judgments and dispensations rendered by the Curia became official when the applicant sent a gift in acknowledgment, with the Curia fixing the size of the gift. And every Christian was subject to papal taxes.

Even before he bought his pontificate, Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia’s income had been 70,000 florins a year. But an occupant of Saint Peter’s chair could do much better than that. Pope Julius

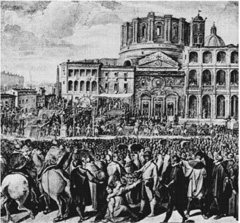

The traffic in indulgences

II formed a “college” of 101 secretaries who each paid him 7,400 florins for the honor. Leo X, more ambitious, created 141 squires and 60 chamberlains in his papal household, and, in return, received 202,000 florins.

Archbishops, bishops—even lower orders of the clergy—grew fat and frequently supported concubines on their fees and tithes. The laity had first protested their systematic impoverishment in the fourteenth century. Germans had seized tax collectors from Rome, jailed them, mutilated many, executed some. There, and elsewhere, brave prelates had supported the people. One, Alvaro Pelayo of Spain, declared: “Wolves are in control of the Church and feed on [Christian] blood!” another, Bishop Durand of Mende, demanded that “the Church of Rome” remove “evil examples from herself … by which men are scandalized, and the whole people, as it were, infected.”

The Vatican was unmoved. Over the years it had increased its levies, and that continued. In 1476 Pope Sixtus IV had proclaimed that indulgences applied to souls suffering in purgatory. This celestial confidence trick was an immediate success; David S. Schiff has described how peasants starved their families and themselves to buy relief for departed relatives. Discontent was growing when the wasteful Pope Leo found himself broke—undone by his war against the Duchy of Urbino. Going to the well once too often, on March 15, 1517, the Holy Father announced a “special” sale of indulgences. The purpose of this “jubilee” bargain (feste dies), as he called it, was to rebuild St. Peter’s basilica. As an incentive donors would receive, not only “complete absolution and remission of all sins,” but also “preferential treatment for their future sins.”

There was, understandably, no mention of a secret agreement under which the Curia would split the jubilee’s profits with young Albrecht of Brandenburg, archbishop of Mainz, who was deeply in debt to Germany’s merchant family, the Fuggers. Albrecht had the pontiff’s sympathy, and he was entitled to it. Albrecht had been obliged to borrow 20,000 florins because that was the price the pope had exacted for his confirmation as prelate.

The new archbishop chose as his jubilee’s principal agent and hawker one Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar in his fifties. There were quaestiarii whose traffic in indulgences was scrupulous, but Tetzel was not among them. He was a sort of medieval P. T. Barnum who traveled from village to village with a brass-bound chest, a bag of printed receipts, and an enormous cross draped with the papal banner. Accompanying him were a Fugger accountant and another friar, an assistant carrying a velvet cushion bearing Leo’s bull of indulgence. Their entrance into a town square was heralded by the ringing of church bells. Jugglers performed and local throngs crowded around, waving candles, flags, and relics.

Setting up in the nave of the local church, Tetzel would begin his pitch by opening the bag and calling out, “I have here the passports … to lead the human soul to the celestial joys of Paradise.” The fees were dirt-cheap, he pointed out, if they considered the alternatives. Christians who had committed a mortal sin owed God seven years’ penance. “Who then,” he asked, “would hesitate for a quarter-florin to secure one of these letters of remission?” Anything could be forgiven, he assured them, anything. He gave an example. Suppose a youth had slipped into his mother’s bed

St. Peter’s Square in Rome at the time of the coronation of Pope Sixtus V, in 1585.

and spent his seed inside her. If that boy put the right coins in the pontiff’s bowl, “the Holy Father has the power in heaven and earth to forgive that sin, and if he forgives it, God must do so also.” Warming up, Tetzel even appealed to the survivors of men who had gone to their graves unshriven: “As soon as the coin rings in the bowl, the soul for whom it is paid will fly out of purgatory and straight to heaven.”

In Germany Tetzel exceeded his quota. He always did. This was his profession; he traveled from one diocese to another, raising funds as instructed by the Curia. Indulgences were popular among the peasantry, but less so among those who, in those days, formed the opinions of the laity. And this time he was in hostile territory. Northeastern Germany—Magdeburg, Halberstadt, and Mainz—had been chosen for this extortion because it was weak. France, Spain, and England were strong, and when they had asked that little be expected of them, pleading poverty, the pontiff had agreed. The decision was not without risk. Antipapal feeling was strong and vocal in Germany. The papal nuncio to the Holy Roman Empire was worried. That part of the Reich, he had written the pope, was in an ugly mood. He had therefore urged cancellation of the jubilee.

Leo had ignored him—unwisely, for presently ominous signs appeared. After watching Tetzel perform, a local Franciscan friar wrote: “It is incredible what this ignorant monk said and preached. He gave sealed letters stating that even the sins a man was intending to commit would be forgiven. The pope, he said, had more power than all the Apostles, all the angels and saints, more even than the Virgin Mary herself, for these were all subjects of Christ, but the pope was equal to Christ.” Another eyewitness quoted the moneyraiser as declaring that even if a man had violated the Mother of God the indulgence would wipe away his sin.

Nevertheless, Tetzel was probably acting within the letter of his archiepiscopal instructions, and he would have emerged triumphant once more had he not crossed, or at least approached, a political line. That was the boundary of Saxony, then ruled by Frederick III, also known variously as Frederick the Wise and, because he was among the privileged few entitled to choose a new Holy Roman emperor, as elector of Saxony. Frederick was no less reverent than other rulers of his time, no less superstitious — he had collected nineteen thousand saintly relics in Wittenberg’s Castle Church—and, until now, no critic of quaestiarii. However, accounts of Tetzel’s extravagant claims had troubled him. He wanted to keep Saxon coins in Saxon pockets. Therefore he had declared the friar and his jubilee sale non grata in his territory. That was where the peddler of paradise passports blundered. He knew he wasn’t wanted in Frederick’s domain, but while working the dioceses of Meissen, Magdeburg, and Halberstadt he came so close to the border that some Saxons crossed over and bought his divine wares.

Frederick was indignant. He considered this an affront. Of far greater moment, several of these Saxon customers brought their “papal letters” to a slender, tonsured monk of grave aspect and hard eyes—Martin Luther—asking him, as a professor at Wittenberg, to judge their authenticity. After careful study Luther pronounced them frauds. Word of this reached Tetzel. He made inquiries. The professor, he was told—correctly—had no intention of offending the Church. Luther was an ardent Catholic, though inclined, as an academic, to draw nice distinctions. Such a man, Tetzel decided, would be easy to intimidate. Therefore, in the most momentous decision of his life—and one of the most momentous in the history of Christianity—he formally denounced him.

TETZEL BECAME the most famous man to misjudge Professor Martin Luther, but he was far from the first. Luther had always been difficult. Few were close to him, and none—including, perhaps, Luther himself—understood the tumultuous forces within him. His genius is unquestioned. He had begun as an Augustinian friar. In 1505, at the age of twenty-two, he was lecturing on the ethics of Aristotle, using the original Greek text. Two years later he was consecrated a priest, and the year after that, though he continued to regard himself as a friar or monk, he was appointed by Frederick to the chair of professor of philosophy at Wittenberg, on the Elbe, about sixty miles southwest of Berlin. Later in his career he translated both the Old and New Testaments into New High German, a language he virtually created, and composed forty-one hymns, for which he wrote both the words and music. The most memorable of these, still sung around the world, is “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.”

In his early years Luther’s loyalty to the Vatican was total; when he first glimpsed the Eternal City in 1511, he fell to his knees crying, “Hail to thee, O holy Rome!” He was already admired as a priest of narrow strength who had risen to early eminence as much by force of character as by intellect. Nevertheless, deep within him lurked a dark, irrational, half-mad streak of violence. This flaw, and it was a flaw, may be explained by his origins, which lay in the ignorant, superstition-ridden depths of medieval society. Luther was the product of a terrifying Teutonic childhood which would have broken most men.

He had been born in 1483, the son of a Mohra peasant who became a Mansfield miner, a husky, hardworking, frugal, humorless, choleric anticleric who loathed the Church yet believed in hell—which, in his imagination, existed as a frightening underworld toward which men were driven by cloven-footed demons, elves, goblins, satyrs, ogres, and witches, and from which they could be rescued only by benign spirits. It was Hans Luther’s conviction that these good witches rarely interceded, though occasionally they could be propitiated by men living lives of relentless, joyless virtue.

Since children were born wicked, as Hans believed, it was virtuous to beat them senseless with righteous cudgels. However, Martin, the eldest of seven children, was never a submissive victim. He was not strong enough to overpower his father, but when the thrashings entered the realm of sadism, the two became, as he later recalled, open enemies. He received no sympathy from his mother. Though more timid, less irascible, and less worldly than her husband—she spent hours on her knees, praying to obscure saints—she shared Hans’s convictions, including his belief in the salubrious effect of a vigorously applied lash. On one occasion, according to Luther, she caught him stealing a nut and whipped him to a bloody pulp.

The Church was the last career such parents would have chosen for their eldest son. He knew it, and that decided him. “The severe and harsh life I led with them,” he wrote, “was the reason I afterward took refuge in the cloister and became a monk. ” Despite its inspirational beginning, his visit to the Vatican left a poor impression on him, but at the time he kept that to himself. His colleagues, dazzled by his treatises and his performances in his lecture hall, would have been astounded to learn that he had never shed the pagan superstitions infused in him even before he had reached the age of awareness—that a part of him was still haunted by pagan nightmares of werewolves and griffins crouched beneath writhing treetops under a full moon, of trolls and warlocks feasting on serpents’ hearts, of men transforming themselves into slimy

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

incubi and coupling with their own sisters while in a cave Brunhilde dreamed of the dank smell of bloodstained axes.

Luther was peculiar in other ways. His fellow monks spoke of the devil, warned of the devil, feared the devil. Luther saw the devil—ran into apparitions of him all the time. He was also the most anal of theologians. In part, this derived from the national character of the Reich. A later mot had it that the Englishman’s sense of humor is in the drawing room, the Frenchman’s sense of humor is in the bedroom, and the German’s sense of humor is in the bathroom. For Luther the bathroom was also a place of worship. His holiest moments often came when he was seated on the privy (Abort) in a Wittenberg monastery tower. It was there, while moving his bowels, that he conceived the revolutionary Protestant doctrine of justification by faith. Afterward he wrote: “These words ‘just’ and ‘justice of God’ were a thunderbolt to my conscience. … I soon had the thought [that] God’s justice ought to be the salvation of every believer. … Therefore it is God’s justice which justifies us and saves us. And these words became a sweeter message for me. This knowledge the Holy Spirit gave me on the privy in the tower.”

Well, God is everywhere, as the Vatican conceded four centuries later, backing away from a Jesuit scholar who had gleefully translated explicit excretory passages in Luther’s Sammtiche Schriften. The Jesuit had provoked angry protests from Lutherans who accused him of “vulgar Catholic polemics.” Yet the real vulgarity lies in Luther’s own words, which his followers have shelved. They enjoy telling the story of how the devil threw ink at Luther and Luther threw it back. But in the original version it wasn’t ink; it was Scheiss (shit). That feces was the ammunition Satan and his Wittenberg adversary employed against each other is clear from the rest of Luther’s story, as set down by his Wittenberg faculty colleague Philipp Melanchthon: “Having been worsted … the Demon departed indignant and murmuring to himself after having emitted a crepitation of no small size, which left a foul stench in the chamber for several days afterwards.”

Again and again, in recalling Satan’s attacks on him, Luther uses the crude verb bescheissen, which describes what happens when someone soils you with his Scheiss. In another demonic stratagem, an apparition of the prince of darkness would humiliate the monk by “showing his arse” (Steiss). Fighting back, Luther adopted satanic tactics. He invited the devil to “kiss” or “lick” his Steiss, threatened to “throw him into my anus, where he belongs,” to defecate “in his face” or, better yet, “in his pants” and then “hang them around his neck.”

A man who had battled the foulest of fiends in der Abort and die Latrine was unlikely to be intimidated by the vaudevillian Tetzel. Yet Luther’s reply to the jubilee agent was not as dramatic as legend has made it. He did not “nail” a denunciation of the pope on the door of Frederick’s Castle Church. In Wittenberg, as in many university towns of the time, the church door was customarily used as a bulletin board; an academician with a new religious theory would post it there, thus signifying his readiness to defend it against all challengers.

Luther’s timing was canny, however. He took advantage of another tradition, the elector’s annual display of his relics on All Saints’ Day, November 1. This always brought a crowd. Therefore at noon on October 31, 1517, he affixed his (Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum (Disputation for the Clarification of the Power of Indulgences) alongside the postulates of other theologians. He did something else. He prepared a German translation to be circulated among the worshipers who would gather in the morning. And he sent a copy to Archbishop Albrecht, sponsor and secret beneficiary of Tetzel’s carnival act.

Luther’s theses—he had posted ninety-five of them—were preceded by a conciliatory preamble: “Out of love for the faith and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions will be discussed at Wittenberg under the chairmanship of the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology.” It did not occur to him that his position was heretical. Nor was it—then. The pontiff, he agreed, retained the right to absolve penitents, “the power of the keys.” He simply argued that peddling pardons like Colosseum souvenirs trivialized sin by debasing the contrition.

However, he then lodged an objection, one Rome could not ignore. The papal keys, he pointed out, could not reach beyond the grave, freeing an unremorseful soul from purgatory or even decreasing its term of penance there. And while he absolved the Holy See from huckstering indulgences, he added a sharp, significant observation, which, in retrospect, may be seen as the first warning flash of the fury he had bottled up within since his hideous childhood. It was, in fact, a direct criticism of the Apostolic See—breathtaking because it could only be interpreted as the premeditated act of a heresiarch, and thus, a capital offense. He wrote: “This unbridled preaching of pardons makes it no easy matter, even for learned men, to rescue the reverence due the pope from … the shrewd questionings of the laity, to wit: ‘Why does not the pope empty purgatory for the sake of holy love and of the dire need of the souls that are there, if he redeems a … number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a church?’ ”

THE SALE of indulgences plunged. Fewer and fewer quarter-florin coins rang in the pontiff’s bowl. The jubilee had virtually collapsed; Tetzel’s spell had been broken. Luther was the new spellbinder—divine or satanic, for opinion was deeply divided—and accounts of his audacity spread across the continent with what was, in the early 1500s, historic speed.

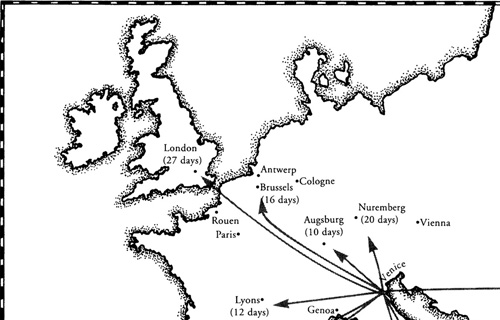

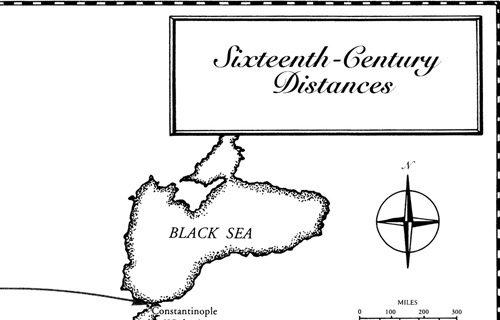

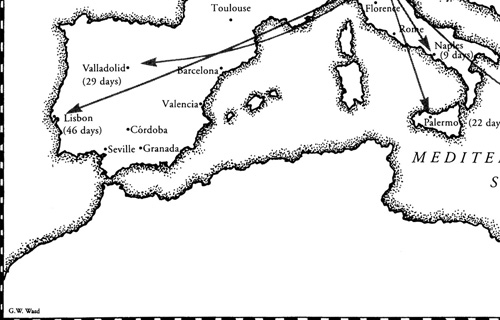

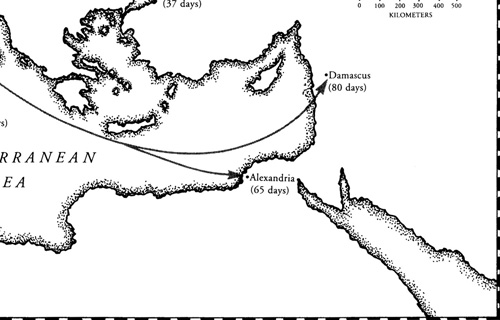

As long as a year would pass before the tidings of great events reached the far corners of Europe. Except for the flatbed presses, which moved at a lentitudinous pace, communications as we know them did not exist. Information was usually carried by travelers, and trips were measured by the calendar. The best surviving timetables start from Venice, then the center of commerce. A passenger departing there could hope to enter Naples nine days later. Lyons was two weeks away; Augsburg, Nuremberg, and Cologne, two or three weeks; Lisbon seven weeks. With luck, a man could reach London in a month, provided the weather over the Channel was cooperative. If a storm broke in midpassage, however, you were trapped. The king of England, leaving Bordeaux under fair skies, did not appear in London until twelve days later.

Yet if news was electrifying, it could pass from village to village and even across the Channel, borne word-of-mouth. That is what happened after Luther affixed his theses to the church door. Before the first week in November had ended, spontaneous demonstrations supporting or condemning him had erupted throughout Germany. Luther had done the unthinkable—he had flouted the ruler of the universe.

Penetrating the essence of the peasants’ faith is difficult. Essentially it was belief in the supernatural. The lower orders of parochial clergy were regarded with contempt but also with affection. Bishops and archbishops, on the other hand, were less popular. In a study of Luther’s homeland on the eve of his rise, Johannes Janssen, himself an eminent Catholic, found the prelates there obsessed with “worldly greed,” while “preaching and the care of souls were altogether neglected.” And, unlike priests faithful to their Konkubinen, they were notoriously promiscuous, sometimes traveling to federal or imperial diets with several mistresses in tow. The peasants’ view of the pope is harder to define. They revered him, but not as the Vicar of Christ. He was more like a great magician. Now his powers had been impeached by a lowly Augustinian theologian. They expected a vengeful response. Its potency would sway their allegiance. If the pontiff’s magic failed, they would begin to turn away from him.

In defying the organized Church, Luther had done something else. He had broken the dam of medieval discipline. By his reasoning, every man could be his own priest, a conclusion he himself would reach in 1520–1521. Moreover, as fragmentary accounts of the Gospels began to circulate, the peasantry learned that the sympathies of Christ and his apostles had lain with the oppressed, not with the princes who had presumed to speak in his name. Because church and state were so entwined in central Europe, Luther’s challenge to ecclesiastical prestige encouraged a proletariat eager to demand a larger share in an increasingly prosperous Germany. Soon a pamphlet titled Karsthans (Pitchfork John) appeared in rural villages, pledging Luther the protection of the peasants. The assumption that he had become their champion was implicit.

The views of the upper classes were very different. Before the succession of disastrous popes their commitment to the Catholic hierarchy and the order of temporal life had been unwavering. Their lives were still guided by the dogmas of the Church, but the corruption in Rome and the flagrant misconduct of the clergy had angered them. It was also their “general opinion,” in the words of Ludwig Pastor, “that in the matter of taxation the Roman Curia put on the pressure to an unbearable degree. … Even men devoted to the Church and the Holy See … often declared that the German grievances against Rome were, from a financial point of view, for the most part only too well founded.” Now they listened attentively to the sermons of Luther’s disciples touring Austria, Bohemia, Saxony, and the Swiss Confederation. The patricians, too, awaited a strong response from Rome.

ON APRIL 24, 1518, the German Augustinians, meeting in Heidelberg, relieved Luther of his duties as district vicar. It was a show of confidence, not a reprimand, and he used his new freedom well, delivering a closely reasoned denunciation of Scholastic doctrine as a pretentious “theory of glory.” Printed copies were circulated across the Continent and discussed in widening circles, including the humanist community. Since the turn of the century humanist leaders had awaited a distinguished theologian with the courage to label Scholasticism as anti-intellectualism parading mindless shibboleths as philosophy. German scholars now published a sheaf of leaflets proclaiming themselves Lutherans.

In England John Colet, who had seen the revolt coming—yet whose loyalty to the papacy would remain unshaken throughout the coming tumult—saw the Curia engrossed not with good works and repentance, but with the size of the fees it could exact. Luther was discovering that he had become the voice of millions who suffered doubly from the Renaissance popes; impoverished by highwaymen like Tetzel, they also grieved for their beloved faith, desecrated by rogues in vestments. From this point forward, his wrath and theirs would join, gathering in volume and strength as together they confronted the most powerful symbol of authority Europe had ever known. Both sides would invoke the name of Christ, but in Germany, where first blood was being drawn, the spectacle invited parallels, not with the New Testament, but with Das Lied vom huren Seyfrid, the pagan fable first heard by Luther as a child, which reaches its climax when Siegfried buries his gory ax in the dragon Fafnir.

The gauntlet had been flung, but Pope Leo merely toyed with it. Archbishop Albrecht, alarmed, sent the theses from Mainz to Rome accompanied by a forceful request that Luther be formally disciplined. Leo misinterpreted the challenge. Dismissing it as another dispute between Augustinians and Dominicans, he turned the matter over to Gabriel della Volta, the vicar general of Luther’s order, instructing him to deal with it through channels, in this case Johann von Staupitz, the Augustinian responsible for Wittenberg. Della Volta’s order may have wound up in some curial pigeonhole or file. Certainly it never reached Staupitz. In effect, the papacy had ignored the defiance in Wittenberg.

Elsewhere, however, the Catholic reaction was vehement. The universities of Louvain, Cologne, and Leipzig, strongholds of theological tradition, condemned the theses in their entirety. And Tetzel, feeling himself libeled, had decided to reply. Because he was an illiterate and ignorant of virtually every principle at stake, the Dominicans had appointed a theologian, Konrad Wimpina, as his collaborator, and in December 1517 One Hundred and Six Anti-Theses had appeared in Frankfurt under Tetzel’s name. Unapologetic, unyielding, the friar defended his distributions of cut-rate salvation in an argument later described in the Catholic Encyclopedia as giving “an uncompromising, even dogmatic, sanction to mere theological opinions that were hardly consonant with the most accurate scholarship.” The following March a hawker offered eight hundred copies of the leaflet in Wittenberg. University students mobbed him, bought the lot, and burned them in the market square.

Luther counterattacked in a tract, Indulgence and Grace. Now the rebelliousness in his tone was unmistakable: “If I am called a heretic by those whose purses will suffer from my truths, I care not much for their brawling; for only those say this whose dark understanding has never known the Bible.” In the Curia wise men, realizing that Tetzel had become an embarrassment, told Leo that he had to go. The pope, agreeing, received Karl von Miltitz, a young Saxon priest of noble lineage now serving in Rome. Once the dust had settled, he told Von Miltitz, he wanted him to travel north and unfrock the discredited friar.

BUT ABANDONING TETZEL now—with orthodox German theologians fiercely defending him—was out of the question. Archbishop Albrecht had privately reprimanded the salesman for his excesses. In public, however, the leadership of the Catholic establishment there closed its ranks and its minds, refusing to discuss compromise. In Rome, a German archbishop called for heresy proceedings against Luther, and the Dominicans demanded his immediate impeachment. Dr. Johann Eck, vice chancellor of Ingolstadt University and perhaps the most eminent theologian in central Europe, attacked the theses in a leaflet, Obelisks, accusing their author of subverting the faith by spreading “poison.” The Curia’s censor of literature, concurring, issued a Dialogue reaffirming “the absolute supremacy of the pope,” and Jakob van Hoogsträten of Cologne demanded Luther be burned at the stake.

Instead he kept scratching away with his pen. In April 1518, the month after Eck’s blast, he published Resolutiones, a curious brochure whose ostensible purpose was to assure the Church of his orthodoxy and submission. In a copy sent to the pontiff he offered “myself prostrate at the feet of your Holiness, with all I am and have. Quicken, slay, call, recall, approve, reprove, as may seem to you good. I will acknowledge your voice as the voice of Christ, residing and speaking in you.” Yet this inscription was wholly inconsistent with the text that followed. Resolutiones implicitly denied the pontiff’s supremacy, suggesting he was answerable to an ecumenical council. The pamphlet went on to slight relics, pilgrimages, extravagant claims for the powers of saints, and the holy city (“Rome … now laughs at good men; in what part of the Christian world do men more freely make a mock of the best bishops than in Rome, the true Babylon?”). He declared the very foundation of the Curia’s indulgences policy—stretching back over three centuries—null and void. The monk of Wittenberg was growing ever more confident, and as his confidence grew, so did his feelings of independence.

Leo was stunned. Abandon indulgences? Just as his pontificate was approaching bankruptcy? He was rebuilding a cathedral, waging wars, funding elaborate dinner parties while trying to keep Raphael, Lotto, Vecchio, Perugino, Titian, Parmigianino, and Michelangelo in wine. The Curia, juggling budgets, was swamped with bills. And now a German monk—a mere friar—had the audacity to condemn a prime source of Vatican revenue. The Holy Father summoned Martin Luther to Rome.

The invitation was declined. Acceptance might mean the stake—there were plenty of precedents for that. At the very least Luther might be assigned to an obscure Italian monastery, where, within a year, he and his cause would be forgotten. Instead he appealed to Frederick the Wise, submitting that German princes should shield their people from extradition. The elector agreed. He liked his controversial Augustinian. (One reason was that Luther’s Wittenberg duties included keeping the university’s books; unlike Leo, he had never resorted to red ink.) And

Pope Leo X (1475–1521)

Maximilian’s advice, which Frederick sought, was decisive. The Habsburg emperor had only five months to live, but he had lost none of the political shrewdness which had forged an intricate dynastic structure, making his family dominant in central Europe. He was keeping a close watch on the interplay of German politics and religion. “Take good care of that monk,” Maximilian wrote the elector. Handing Luther over to the pontiff, he explained, could be a political blunder. In his judgment, anticlerical sentiment was increasing throughout Germany.

Almost immediately an imperial diet, or Reichstag, confirmed him. The emperor, in summoning his German princes to Augsburg, was responding to a request from Rome. Leo had told him he was planning a new crusade against the Turks and wanted a surtax to support it. The diet rejected his appeal. The action was highly unusual, but not unprecedented; Frederick, after collecting a papal levy from his people, had decided to keep it and build the University of Wittenberg. His peers had been heartened. All the Vatican wanted from the princes, it seemed, was money, money, and more money. In their view the confirmation fees, annates, and costs of canonical litigation were already millstones around the empire’s neck. Besides, they had sent the Curia revenues for other crusades, only to learn that the ventures had been canceled, while the funds, unreturned, had been spent on Italian projects. All previous crusades had failed anyway. And the princes weren’t worried about Turks. The real enemy of Christendom, they decided, was what one of them called “the hell-hound in Rome.” In a conciliatory letter to the Vatican, Maximilian assured the pope that he would move sternly against heresy. At the same time, he ventured to suggest that Luther be treated carefully.