II

THE SHATTERING

HIS NAME RICOCHETS down the canyons of nearly five centuries—ricochets, because the trajectory of his zigzagging life, never direct, dodged this way and that, ever elusive and often devious. We cannot even be certain what to call him. In Portuguese documents his name appears alternately as Fernão de Magalhães and Fernão de Magalhais. Born the son of a fourth-grade nobleman, in middle age he renounced his native land and, as an immigrant in Seville, took the nom de guerre Fernando de Magallanes. Sometimes he spelled it that way, sometimes as Maghellanes. In Sanlúcar de Barrameda, before embarking for immortality on September 20, 1519, he signed his last will and testament as Hernando de Magallanes. Cartographers Latinized this to Magellanus —a German pamphleteer printed it as “Wagellanus”—and we have anglicized it to Magellan. But what was his real nationality? On his historic voyage he sailed under the colors of Castile and Aragon. Today Lisbon proudly acclaims him: “Êle é nosso!”—“He is ours!”—but that is chutzpah. In his lifetime his countrymen treated him as a renegade, calling him traidor and transfuga—turncoat.

One would expect the mightiest explorer in history to have been sensitive and proud, easily stung by such slurs. In fact he was unoffended. By our lights, his character was knotted and intricate. It was more comprehensible to his contemporaries, however, because the capitán-general of 1519–1521 was, to an exceptional degree, a creature of his time. His modesty arose from his faith. In the early sixteenth century, pride in achievement was reserved for sovereigns, who were believed to be sheathed in divine glory. Being a lesser mortal, and a pious one, Magellan assumed that the Madonna was responsible for his accomplishments.

At the time he may have underrated them. That is more understandable. He was an explorer, a man whose destiny it was to venture into the unknown; what he found, therefore, was new. He had some idea of its worth but lacked accurate standards by which to measure it. Indeed, he couldn’t even be certain of what he was looking for until he had found it, and the fact that he had no clear view of his target makes the fact that he hit it squarely all the more remarkable.

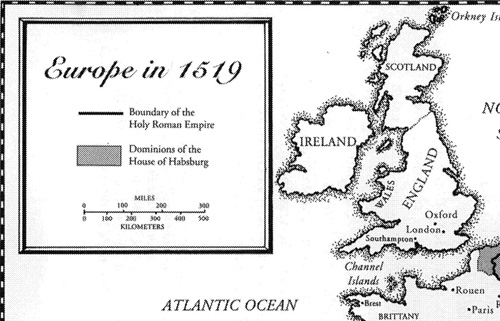

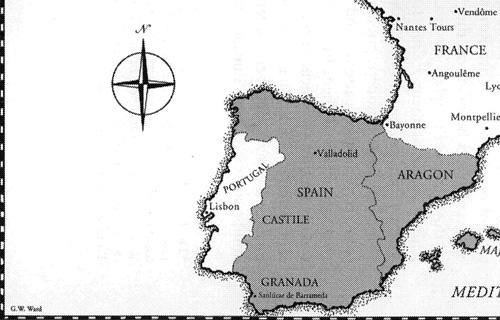

His Spanish sponsors did not share his sense of mission. They sought profit, not adventure. His way around that obstacle seems to have been to ignore it and mislead them. Sailing around the world was unmentioned during his royal audience with Carlos I, sovereign of Spain, who, as the elected Holy Roman emperor Charles V, was to play a key (if largely unwitting) role in the great religious revolution which split Christendom and signaled the end of the medieval world. Carlos’s commission to Magellan was to journey westward, there to claim Spanish possession of an archipelago then in the hands of his Iberian rival, Manuel I of Portugal. These were the Spice Islands—the Moluccas, lying between Celebes and New Guinea. Now an obscure part of Indonesia, they are unshown on most maps, but then the isles were considered priceless. Officially, the capitán-general’s incentive lay in the king’s pledge to him. Two of the islands would become Magellan’s personal fief and he would receive 5 percent of all profits from the archipelago, thus making his fortune.

But as Timothy Joyner points out in his life of Magellan, this Moluccan plan was a disaster. Indeed, as the leader of the expedition, Magellan was killed before he could even reach there. He had, however, landed in the Philippines. This was of momentous importance, for eastbound Portuguese had reconnoitered the Spice Islands nine years earlier. Therefore, in overlapping them, he had closed the nexus between the 123rd and 124th degrees of east longitude and thus completed the encirclement of the earth.

Yet his achievements were slighted. Death is always a misfortune, at least to the man who has to do the dying. In Magellan’s case it was exceptionally so, however, for as a dead discoverer he was unhonored in his own time. Even Magellan’s discovery of the strait which bears his name was belittled. Only a superb mariner, which he was, could have negotiated the foggy, treacherous, 350-mile-long Estrecho de Magallanes. In the years after his death, expedition after expedition tried to follow his lead. They failed; all but one ended in shipwreck or turned homeward, and the exception met disaster in the Pacific. Frustrated and defeated, skippers decided that Magellan’s exploit was impossible and declared it a myth. Nearly sixty years passed before another great sailor, Sir Francis Drake, successfully guided The Golden Hind through the tortuous passage and survived to tell the tale.

Had fortune and a viceregal role in the Moluccas been Magellan’s real inducement, he would have been a failure by his own lights. But his original motives remain obscure. Desperately searching for sponsorship of his voyage, he may have feigned interest in the Spice Islands. There is no proof of that, but it would have been in character. And were that the case, he would have confided in no one; he was always the most secretive of men. Moreover, the true drives of men are often hidden from them. Magellan’s vision may or may not have been cloudy, but clearly his real inspiration was nobler than profits. And in the end he proved that the world was round.

In so doing, he did much more. He provided a linchpin for the men of the Renaissance. Philosophers, scholars, and even learned men in the Church had begun to challenge stolid medieval assumptions, among them pontifical dogma on the shape of the earth, its size, and its position and movement in the universe. Magellan gave men a realistic perception of the globe’s dimensions, of its enormous seas, of how its landmasses were distributed. Others had raised questions. He provided answers, which now, inevitably, would lead to further questions—to challenges which continue on the eve of the twenty-first century.

The Spanish court was less than ecstatic. It had wanted Magellan to hoist its flag over the Moluccas, thereby breaking Portugal’s monopoly of the Oriental spice trade: cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and pepper. Spices made valuable preservatives, but trafficking in them had other, sinister implications. They were also used, and used more often, to disguise the odors and the ugly taste of spoiled meat. The regimes that encouraged and supported the spice trade were, in effect, accomplices in the poisoning of their own people. Moreover, medieval Europeans were extremely vulnerable to disease. This was the down side of exploration. The discoverers and their crews had carried European germs to distant lands, infecting native populations. Then, when they returned, they bore exotic diseases which could spread across the continent unchecked.

Sometimes the source of an epidemic could be quickly traced. Typhus, never before known in Europe, swept Aragon immediately after Spanish troops returned from their Cyprian triumph over the Moors. More often the origin was never identified. No one knows why Europe’s first outbreak of syphilis ravaged Naples in 1495, or why the “sweating sickness” devastated England later the same year—“Scarce one among a hundred that sickened did escape with life,” wrote the sixteenth-century chronicler Raphael Holinshed—or the specific origins of the pandemic Black Death, which had been revisiting Europe at least once a generation since October 1347, when a Genoese fleet returning from the Orient staggered into Messina harbor, all members of its crews dead or dying from a combination of bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic plague strains. All that can be said with certainty is that the late 1400s and early 1500s were haunted by dark reigns of pestilence, that life became very cheap, and that this wretched situation can scarcely have discouraged explorers eager to investigate what lay over the horizon.

The mounting toll of disease—each night gravediggers’ carts creaked down streets as drivers cried, “Bring out your dead!” and in Germany entire towns, a chronicler of the time wrote, had become like cemeteries “in ihrer betru benden Einsamkeit” (“in their sad desertion”)—was far from the only sign that society seemed to have lost its way. In some ways the period seems to have been the worst of times—an age of treachery, abduction, fratricide, depravity, barbarism, and sadism. In England, by royal decree, the Star Chamber sent innocent men to the gallows ignorant of both their accusers and the charges against them. In Florence, the fief of Lorenzo de’ Medici, local merchants were licensed to organize the African slave trade, after which the first “blackbirders” arrived in Italian ports with their wretched human cargoes. Tomás de Torquemada, a Dominican monk, presided over the Spanish Inquisition—actually conceived by Isabella of Castile—which tortured accused heretics until they confessed.

Torquemada’s methods reveal much about one of the age’s most unpleasant characteristics: man’s inhumanity to man. Sharp iron frames prevented victims from sleeping, lying, or even sitting. Braziers scorched the soles of their feet, racks stretched their limbs, suspects were crushed to death beneath chests filled with stones, and in Germany the very mention of die verfüchte Jungfer—the dreaded old iron maid—inspired terror. The Jungfer embraced the condemned with metal arms, crushed him in a spiked hug, and then opened, letting him fall, a mass of gore, bleeding from a hundred stab wounds, all bones broken, to die slowly in an underground hole of revolving knives and sharp spears.

Jewry was luckier—slightly luckier—than blacks. If the pogroms of the time are less infamous than the Holocaust, it is only because anti-Semites then lacked twentieth-century technology. Certainly they possessed the evil will. In 1492, the year of Columbus, Spain’s Jews were given three months to accept Christian baptism or be banished from the country. Even those who had been baptized were distrusted; Isabella had fixed her dark eye on converted Jews suspected of recidivism—Marranos, she called them; “pigs”—and marked them for resettlement as early as 1478. Eventually between thirty thousand and sixty thousand were expelled. Meantime the king of Portugal, finding merit in the Spanish decree, ordered the expulsion of all Portuguese Jews. His soldiers were instructed to massacre those who were slow to leave. During a single night in 1506 nearly four thousand Lisbon Jews were put to the sword. Three years later the systematic persecution of the German Jews began.

Blacks and Jews suffered most, but any minority was considered fair game for tyrants. In Moscovy, Ivan III Vasilyevich, the grand duke of Moscow, proclaimed himself the first czar of Russia and then drove all Germans from Novgorod and enslaved Lithuania. Fevered Turks swung their long curved swords in Egypt, leaving the gutters of Cairo awash in Arab blood, and then pillaged Mecca. At the turn of the sixteenth century, Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros—who would become Spain’s new inquisitor general —provided Europe with an extraordinary example of medieval genocide. He ordered all Grenadine Moors to accept baptism. Cisneros wasn’t really seeking converts. He hoped to goad them to revolt, and when they did rise he annihilated them. Any nonconformity, any weakness, was despised; the handicapped were given not compassion, but terror and pain, as prescribed in Malleus maleficarum (The Witches’ Hammer), a handbook by the inquisitors Johann Sprenger and Heinrich Kraemer, which justified the shackling and burning of, among others, the mentally ill.

These victims were helpless and oppressed, but no one was really safe. In 1500 the eminent Alfonso of Aragon, son-in-law of a pope, was slain by his wife’s brother; seven years later Alfonso’s killer, who had become brother-in-law of the king of Navarre, was himself murdered by assassins in the employ of the Count of Lerin. Intrigue thickened in every princely court, liquidation of enemies was tolerated among all social classes, and because the technology of homicide was in its infancy — August Kotter, the German gunsmith, did not invent the rifle until 1520—their deaths were often macabre. Perhaps the most celebrated crime of the Middle Ages had been committed in the Tower of London: the disappearance and, it was thought, the murder of two young heirs to the English throne in 1483. This outrage was widely believed to be the work of the Duke of Gloucester, who became King Richard III. But there were other, equally bizarre royal homicides. The reign of King James III of Scotland ended in his thirty-seventh year when an assassin, disguised as a priest, heard his confession and then eviscerated him. And in his first sovereign act, the new Ottoman sultan Bayezid ordered his brother, whom he regarded as a threat to his power, publicly strangled.

Despots, confronted by violence, struck back with equal fury; for every eye lost, they gouged out as many eyes as they could reach. In gentler times, reformers and protesters are given at least the semblance of a fair hearing. There was none of that then. In 1510 two former speakers of the House of Commons found themselves in vehement disagreement with Parliament over taxation. The issues are obscure, but Parliament’s solution of them was not; on the hottest day of that August both men were beheaded. Six years later, on May Day, London’s street people staged a public demonstration to express exasperation over their plight. On orders from Thomas Cardinal Wolsey, sixty of them were hanged.

AT ANY GIVEN MOMENT the most dangerous enemy in Europe was the reigning pope. It seems odd to think of Holy Fathers in that light, but the five Vicars of Christ who ruled the Holy See during Magellan’s lifetime were the least Christian of men: the least devout, least scrupulous, least compassionate, and among the least chaste—lechers, almost without exception. Ruthless in their pursuit of political power and personal gain, they were medieval despots who used their holy office for blackmail and extortion. Under Innocent VIII (r. 1484–1492) simony was institutionalized; a board was set up for the marketing of favors, absolution, forged papal bulls—even the office of Vatican librarian, previously reserved for the eminent—with 150 ducats (about $3,750) * from each transaction going to the pontiff. Selling pardons for murderers raised some eyebrows, but a powerful cardinal explained that “the Lord desireth not the death of a sinner but rather that he live and pay.” The fact is that everything in the Holy See was up for auction, including the papacy itself. Innocent’s successor, the Spanish cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, became Alexander VI (r.1492–1503), the second Borgia pope—Callixtus III had been the first—by buying off the other leading candidates. He sent his closest rival, Ascanio Cardinal Sforza, four mules laden with ingots of gold.

The Vatican’s permissive attitude toward men convicted of homicide was not entirely illogical. The papal palace itself was often home to killers and their accomplices. Popes and cardinals hired assassins, sanctioned torture, and frequently enjoyed the sight of blood. In his official history, Storia d’Italia (1561–1564), Francesco Guicciardini noted the remarkable spectacle of “the High Priest, the Vicar of Christ on earth”—in this instance Julius II—“excited” by a scene in which Christians slaughtered one another, “retaining nothing of the pontiff but the name and the robes.” The Alsatian Johann Burchard was papal magister ceremoniarum, or master of ceremonies, from 1483 to 1506. Burchard was one of those rare men historians bless: a diarist. In his Diarium, a day-by-day chronicle of pontifical life, he tells how, at one Vatican banquet, another Holy Father “watched with loud laughter and much pleasure” from a balcony while his bastard son slew unarmed criminals, one by one, as they were driven into a small courtyard below.

That was recreational homicide. The strangling of Alfonso Cardinal Petrucci with a red silk noose—the executioner was a Moor; Vatican etiquette enjoined Christians from killing a prince of the Church—was a graver matter. In 1517 Petrucci, who considered himself ill used by Pope Leo X, had led a conspiracy of several cardinals to dispatch the Holy Father by injecting poison into his buttock on the pretext of lancing a boil. A servant betrayed them. Petrucci’s accomplices were pardoned after paying huge fines. The highest, 150,000 ducats, was exacted from Raffaele Cardinal Riario, a great-nephew of a previous pope.

Such grisly tales of pontifical mayhem are found in contemporary diaries, but the details of massacres among the lower Roman classes are lost to us, though we know they occurred; diplomats stationed there attest to that. An envoy from Lombardy wrote of “murders innumerable. … One hears nothing but moaning and weeping. In all the memory of man the Church has never been in such an evil plight.” That plight grew wickeder; a few years later the Venetian ambassador reported that “every night four or five murdered men are discovered, bishops, prelates, and others.” If such slaughters were remarkable, so was the alacrity with which the Eternal City forgot them. When the blood on killers’ knives had clotted and dried, when the graves had been filled in and cadavers removed from the Tiber, the mood tended to be hedonistic. “God has given us the papacy,” Leo X wrote his brother. “Let us enjoy it.” The prelates of that age had large appetites for pleasure. Pietro Cardinal Riario held “a saturnalian banquet,” according to one account, “featuring a whole roasted bear holding a staff in its jaws, stags reconstructed in their skins, herons and peacocks in their feathers, and”—there would be more of this later—“orgiastic behavior by the guests appropriate to the ancient Roman model.”

In previous centuries, when the cause of Christianity had met with some striking success, their predecessors had opened St. Peter’s for Te Deums of thanksgiving. Now prayer had become unfashionable. Alexander VI caught the spirit of the new age in the first year of his reign. Told that Castilian Catholics had defeated the Moors of Granada, this Spanish pontiff scheduled a bullfight in the Piazza of St. Peter’s and cheered as five bulls were slain. The menu for Riario’s feast and the Borgia pope’s celebration reveal a Church hopelessly at odds with the preachings of Jesus, whose existence was the sole reason for its existence. But sitting in the Piazza of St. Peter’s was more comfortable than kneeling at the altar within, and other diversions were more entertaining than holy communion. Among them were compulsive spending on entertainment, gambling (and cheating) at cards, writing dreadful poems and reciting them in public, hiring orchestras to play while the prelates wallowed in gluttony, applauding elaborate theatrical performances. During the digestive process, the churchmen emptied great flagons of strong wine, whereupon intoxication inspired their eminences and even His Holiness to improvise bawdy exhibitions with female guests selected from the city’s brothels—which kept the papal master of ceremonies scribbling in his diary—until dawn brightened the papal palace and hangovers gave its inhabitants some idea of how merciless God’s vengeance could be.

It was Alexander, the Borgia pope, who first suppressed books critical of the papacy. He was either unaware of Burchard’s diary or indifferent to it, though there is another possibility: he may have been incapable of appreciating it. Men accept the values of their time and reject criticisms of them as irrelevant. Moreover, iniquitous regimes do not perpetuate themselves in disciplined societies, nor does a strong, pure, holy institution, supported by centuries of selflessness and integrity, abruptly find itself wallowing in corruption. Vice, no less than virtue, arises from precedents. Over the thirteen centuries since Christianity’s rise to power the Church had lost its way because the wrong criteria had insinuated themselves into its sanctuaries, turning piety into blasphemy, supplanting worship with scandal, and substituting the pursuit of secular power for eternal grace.

IRONICALLY, the purity of Christ’s vision had been contaminated by its very popularity. As Christianity expanded through mass conversions, its evangelists had tempered their exhortations, accommodating their message to those whose souls they sought to save. Philanthropy, one of the Church’s most admirable virtues, had become another source of vitiation. Donations poured in from the faithful, and the unspent wealth was passed up to the ecclesiastical hierarchy, where it accumulated and led to dissipation, debauchery, and—because spendthrifts are always running out of funds—demands for still more money. Here a dangerous solution presented itself, one which, when it was adopted, almost guaranteed future abuse. Ancient German custom offered convicted criminals a choice; they could be punished or, if they were wealthy, pay fines (Wehrgeld). Buying salvation was new to the Church. It was also sacrilegious. Early Christians had atoned for their sins by confession, absolution, and penance. Now it became possible to erase transgressions by buying indulgences. The papacy, searching for a scriptural precedent, settled on Matthew 16:19, in which Jesus tells Peter: “I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

On this shakiest of foundations the Holy See built a bureaucracy in which Peter’s power, appropriated by pontiffs, was delegated to bishops, who passed it on to priests, who sent out friars in pursuit of sinners, empowered to judge the price to be paid for the sin, from which he deducted his commission. In Rome the contributions were welcomed and, in the beginning, used to finance hospitals, cathedrals, and crusades. Then other, less admirable causes appeared. Holy Fathers permitted those who had violated God’s commandments to buy release from purgatory, thus encroaching on the sacrament of penance.

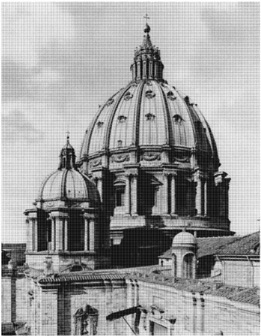

At the same time, the lawlessness and disorders of the Dark Ages—particularly after the papacy had fallen under the dominance of feudal aristocrats in the ninth century—had led churchmen first to collaborate with secular rulers, and then to seek their subjugation. Pontiffs began by regulating the behavior of despots. Then they erected awesome cathedrals as symbols of their secular power, became enmeshed in political manipulations, and, finally, made war on their enemies.

IN THE VERY BEGINNING the first Vicars of Christ had withdrawn from the world and its temptations. Now they became indistinguishable from the nobility. Once they had held the blessings of austerity to be inviolate, even renouncing marriage and cohabitation. Now celibacy yielded to widespread clerical concubinage and, in the convents, to promiscuity and homes for fatherless children born to women who had pledged their virtue as brides of Christ.

The precept that men of God should sleep alone, established by the Lateran Councils of 1123 and 1139 after nine hundred years of hemming and hawing, had begun to fray well before the dawn of the sixteenth century. Now it was a thing of shreds and patches. The last pontiff to take it seriously had died in 1471, and even he, during his youthful days as a bishop of Trieste, had slept with a succession of mistresses. A generation later the occupants of Saint Peter’s chair were openly acknowledging their bantlings, endowing their sons with titles and their daughters with dowries.

In the Vatican nepotism ran amok. Sixtus IV (r. 1471–1484), upon donning the miter, appointed two of his nephews—both dissolute youths—to the sacred College of Cardinals. Later he put red hats on three more nephews and a grandnephew. He also named an eight-year-old boy archbishop of Lisbon and an eleven-year-old archbishop of Milan, though, quite apart from the fact that both were children, neither had received any religious instruction. Innocent VIII, who succeeded Sixtus in 1484, doted on Franceschetto Cibò, his son by a nameless courtesan. Innocent couldn’t make a cardinal of Franceschetto. Standards had not deteriorated that far—yet—and the youth didn’t seem interested. What excited him was roaming city streets each night with a pack of Roman hoodlums, gang-raping young women, some of them nuns; sodomizing them and then leaving them unconscious, bloody, bruised, often with serious injuries, in the streets. The pope’s son was not only a guttersnipe; he was also one of history’s great spendthrifts. To support his lifestyle Innocent raised simony to new levels. By the time he found a suitable bride for Frances-chetto, a Medici, he had to mortgage the papal tiara and treasury to pay for the wedding. Then he appointed his son’s new brother-in-law to the sacred college. The new cardinal and future pope—Leo X—was fourteen years old.

Even Leo X (r. 1513–1521), who fathered no children, shared the passion to honor papal relatives. He began in 1513 with his first cousin, Giulio de’ Medici, whose mother, all Rome knew, had been a casual partner at a drunken Holy Week frolic. By now there were precedents for conferring red hats on illegitimate sons; Alexander VI had put one on his own teenaged bastard, Cesare Borgia. Leo had big plans for Giulio, so he perjured himself, swearing out an affidavit that the youth’s parents had been secretly married. He then appointed five more members of his family, three nephews and two first cousins, to the cardinal’s college. Meantime his hopes for Giulio, like Giulio himself, were maturing. The boy cardinal became a man, served his benefactor as chief minister, and, in 1523, became pope himself. However, it is just as well that Leo did not live to see his dream realized. As Clement VII, Giulio was to become the ultimate pontifical disaster.

UNDISCIPLINED BY PIETY, most of these popes are nonetheless remembered for their consummate skills in the brutal politics of the era. Only men with strong power bases of their own, notably leaders of great Italian families—the Sforzas, Medicis, Pazzis, Aragons—dared challenge them. At the turn of the century the most popular critic of Alexander VI, the Borgia pope, was a Florentine, Girolamo Savonarola of San Marco, a charismatic, idealistic Dominican friar with an enormous following in Florence, where he had introduced a democratic government free of corruption. Savonarola (1452–1498) was among those offended by Vatican orgies and Alexander’s celebrated collection of pornography. The friar’s protests took the form of annual “bonfires of the vanities”—carnivals in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria, where he tossed lewd pictures, pornography, personal ornaments, cards, and gaming tables on the flames. To his multitudes he would roar: “Popes and prelates speak against pride and ambition and they are plunged into it up to their ears.” The papal palace, he said, had literally become a house of prostitution where harlots “sit upon the throne of Solomon and signal to the passersby. Whoever can pay enters and does what he wishes.”

Savonarola also charged the Vicar of Christ with simony and demanded that he be removed. Alexander at first responded warily, merely ordering the friar gagged. But Savonarola continued to defy him. The pontiff, he declared “is no longer a Christian. He is an infidel, a heretic, and as such has ceased to be pope.” The

Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498)

Holy Father tried to buy him off with a cardinal’s hat. Savonarola indignantly rejected it—“A red hat?” he cried; “I want a hat of blood!”—and that was the end of him. Alexander excommunicated him; then, when Savonarola again defied him by continuing to celebrate Mass and give communion, the pope condemned him as a heretic, sentenced him to torture, and finally had him hanged and burned in the Piazza della Signoria.

The pontiffs of that time cannot be said to have been fastidious. They even executed their enemies in churches, where victims’ bodyguards were likeliest to be caught off guard. Allying himself with the Pazzi family, who were challenging the Florentine power of Lorenzo de’ Medici—Lorenzo the Magnificent—Pope Sixtus IV conspired with them to murder Lorenzo and his handsome brother Giuliano. He chose their most defenseless moment, when they were observing High Mass in the Florentine cathedral. The signal for the killers was the bell marking the elevation of the host. Giuliano fell at the altar, mortally wounded, but Lorenzo was not called magnificent for nothing. Drawing his long sword, he escaped into the sacristy and barricaded himself there until help arrived.

If the pope’s attack says much about the era, so does Lorenzo’s vengeance. On his instructions some of the Pazzi gang were hanged from balconies of the Palace of the Signoria while the rest were emasculated, dragged through the streets, hacked to death, and flung into the Arno. By medieval standards Lorenzo’s revenge had not been excessive, though that cannot be said of Denmark’s King Christian II, who invaded Sweden early in 1520. In January, Sten Sture, Sweden’s leader, was killed in action. Heavy fighting continued throughout the year, however, and it was autumn before Sture’s widow, Dame Christina Gyllenstjerna, surrendered. Christian had promised her a general amnesty, but a king’s word wasn’t worth much then. He immediately broke his, and in spectacular fashion. First two Swedish bishops were beheaded in Stockholm’s public square at midnight, November 8, while eighty of their parishioners, who had been summoned to witness the execution, were butchered where they stood. The Danish king then disinterred Sten Sture’s remains. After ten months in the grave they were scarcely recognizable. Rotting, crawling with maggots, emitting a nauseous stench, the corpse was nevertheless burned. Next Sture’s small son was flung — alive—into the flames. Then Dame Christina, who had been forced to watch all this, was sentenced to live out her days as a common prostitute.

WHAT WAS the world like—and to them it was the only world, round which the sun orbited each day—when ruled by such men? Imagination alone can reconstruct it. If a modern European could be transported back five centuries through a kind of time warp, and suspended high above earth in one of those balloons which fascinated Jules Verne, he would scarcely recognize his own continent. Where, he would wonder, looking down, are all the people? Westward from Russia to the Atlantic, Europe was covered by the same trackless forest primeval the Romans had confronted fifteen hundred years earlier, when, according to Tacitus’s De Germania, Julius Caesar interviewed men who had spent two months walking from Poland to Gaul without once glimpsing sunlight. One reason the lands east of the Rhine and north of the Danube had proved unconquerable to legions commanded by Caesar and over seventy other Roman consuls was that, unlike the other territories he subdued, they lacked roads.

But there were people there in A.D. 1500. Beneath the deciduous canopy, most of them toiling from sunup to sundown, dwelt nearly 73 million people, and although that was less than a tenth of the continent’s modern population, there were enough Europeans to establish patterns and precedents still viable today. Twenty million of them lived in what was known as the Holy Roman Empire—which, in the hoary classroom witticism, was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. It was in fact central Europe: Germany and her bordering territories. * There were 15 million souls in France, Europe’s most populous country. Thirteen million lived in Italy, where the population was densest, 8 million in Spain, and a mere 4.5 million—the number of Philadelphians in 1990—in England and Wales.

A voyager into the past would search in vain for the sprawling urban complexes which have dominated the continent since the Industrial Revolution transformed it some two hundred years ago. In 1500 the three largest cities in Europe were Paris, Naples, and Venice, with about 150,000 each. The only other communities with more than 100,000 inhabitants were situated by the sea, rivers, or trading centers: Seville, Genoa, and Milan, each of them about the size of Reno, Nevada; Eugene, Oregon; or Beaumont, Texas. Even among the celebrated Reichsstädte of the empire, only Cologne housed over 40,000 people. Other cities were about the same: Pisa had 40,000 citizens; Montpellier, the largest municipality in southern France, 40,000; Florence 70,000; Barcelona 50,000; Valencia 30,000; Augsburg 20,000; Nuremberg 15,000; Antwerp and Brussels 20,000. London was by far England’s largest town, with 50,000 Londoners; only 10,000 Englishmen lived in Bristol, the second-largest.

Twentieth-century urban areas are approached by superhighways, with skylines looming in the background. Municipalities were far humbler then. Emerging from the forest and following a dirt path, a stranger would confront the grim walls and turrets of a town’s defenses. Visible beyond them would be the gabled roofs of the well-to-do, the huge square tower of the donjon, the spires of parish churches, and, dwarfing them all, the soaring mass of the local cathedral.

If the bishop’s seat was the spiritual heart of the community, the donjon, overshadowing the public square, was its secular nucleus. On its roofs, twenty-four hours a day, stood watchmen, ready to strike the alarm bells at the first sign of attack or fire. Below them lay the council chamber, where elders gathered to confer and vote; beneath that, the city archives; and, in the cellar, the dungeon and the living quarters of the hangman, who was kept far busier than any executioner today. Sixteenth-century men did not believe that criminal characters could be reformed or corrected, and so there were no reformatories or correctional institutions. Indeed, prisons as we know them did not exist. Maiming and the lash were common punishments; for convicted felons the rope was commoner still.

The donjon was the last line of defense, but it was the wall, the first line of defense, which determined the propinquity inside it. The smaller its circumference, the safer (and cheaper) the wall was. Therefore the land within was invaluable, and not an inch of it could be wasted. The twisting streets were as narrow as the breadth of a man’s shoulders, and pedestrians bore bruises from collisions with one another. There was no paving; shops opened directly on the streets, which were filthy; excrement, urine, and offal were simply flung out windows.

And it was easy to get lost. Sunlight rarely reached ground level, because the second story of each building always jutted out over the first, the third over the second, and the fourth and fifth stories over those lower. At the top, at a height approaching that of the great wall, burghers could actually shake hands with neighbors across the way. Rain rarely fell on pedestrians, for which they were grateful, and little air or light, for which they weren’t. At night the town was scary. Watchmen patrolled it—once clocks arrived, they would call, “One o’clock and all’s well!”—and heavy chains were stretched across street entrances to foil the flight of thieves. Nevertheless rogues lurked in dark corners.

One neighborhood of winding little alleys offered signs, for those who could read them, that the feudal past was receding. Here were found the butcher’s lane, the papermaker’s street, tanners’ row, cobblers’ shops, saddlemakers, and even a small bookshop. Their significance lay in their commerce. Europe had developed a new class: the merchants. The hubs of medieval business had been Venice, Naples, and Milan—among only a handful of cities with over 100,000 inhabitants. Then the Medicis of Florence had entered banking. Finally, Germany’s century-old Hanseatic League stirred itself and, overtaking the others, for a time dominated trade.

The Hansa, a league of some seventy medieval towns centering around Bremen, Hamburg, and Lübeck, was originally formed in the thirteenth century to combat piracy and overcome foreign trade restrictions. It reached its apogee when a new generation of rich traders and bankers came to power. Foremost among them was the Fugger family. Having started as peasant weavers in Augsburg, not a Hanseatic town, the Fuggers expanded into the mining of silver, copper, and mercury. As moneylenders, they became immensely wealthy, controlling Spanish customs and extending their power throughout Spain’s overseas empire. Their influence stretched from Rome to Budapest, from Lisbon to Danzig, from

A sixteenth-century town wall

Moscow to Chile. In their banking role, they loaned millions of ducats to kings, cardinals, and the Holy Roman emperor, financing wars, propping up popes, and underwriting new adventures—putting up the money, for example, that King Carlos of Spain gave Magellan in commissioning his voyage around the world. In the early sixteenth century the family patriarch was Jakob Fugger II, who first emerged as a powerful figure in 1505, when he secretly bought the crown jewels of Charles the Bold, duke of Burgundy. Jakob first became a count in Kirchberg and Weisser-horn; then, in 1514 the emperor Maximilian I—der gross Max—acknowledged the Fuggers’ role as his chief financial supporter for thirty years by making him a hereditary knight of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1516, by negotiating complex loans, Jakob made Henry VIII of England a Fugger ally. It was a tribute to the family’s influence, and to the growth of trade everywhere, that a year later the Church’s Fifth Lateran Council lifted its age-old prohibition of usury.

Each European town of any size had its miniature Fugger, a merchant whose home in the marketplace typically rose five stories and was built with beams filled in with stucco, mortar, and laths. Storerooms were piled high with expensive Oriental rugs and containers of powdered spices; clerks at high desks pored over accounts; the owner and his wife, though of peasant birth, wore gold lace and even ignored laws forbidding anyone not nobly born to wear furs. In the manner of a grand seigneur the merchant would chat with patrician customers as though he were their equal. Impoverished knights, resenting this, ambushed merchants in the forest and cut off their right hands. It was a cruel and futile gesture; commerce had arrived to stay, and the knights were just leaving. Besides, the adversaries were mismatched. The true rivals of the mercantile class were the clerics. Subtly but inexorably the bourgeois would replace the clergy in the continental power structure.

THE TOWN, HOWEVER, was not typical of Europe. In the early 1500s one could hike through the woods for days without encountering a settlement of any size. Between 80 and 90 percent of the population (the peasantry; serfdom had been abolished everywhere except in remote pockets of Germany) lived in villages of fewer than a hundred people, fifteen or twenty miles apart, surrounded by endless woodlands. They slept in their small, cramped hamlets, which afforded little privacy, but they worked—entire families, including expectant mothers and toddlers—in the fields and pastures between their huts and the great forest. It was brutish toil, but absolutely necessary to keep the wolf from the door. Wheat had to be beaten out by flails, and not everyone owned a plowshare. Those who didn’t borrowed or rented when possible; when it was impossible, they broke the earth awkwardly with mattocks.

Knights, of course, experienced none of this. In their castles—or, now that the cannon had rendered castle defenses obsolete, their new manor houses—they played backgammon, chess, or checkers (which was called cronometrista in Italy, dames in France, and draughts in England). Hunting, hawking, and falconry were their outdoor passions. A visitor from the twentieth century would find their homes uncomfortable: damp, cold, and reeking from primitive sanitation, for plumbing was unknown. But in other ways they were attractive and spacious. Ceilings were timbered,

A medieval fair: customers, cloth merchants, a beggar, a draper’s shop, a money-weigher, mountebanks

floors tiled (carpets were just beginning to come into fashion); tapestries covered walls, windows were glass. The great central hall of the crumbling castles had been replaced by a vestibule at the entrance, which led to a living room dominated by its massive hearth, and, beyond that, a “drawto chamber,” or “(with)drawing room” for private talks and a “parler” for general conversations and meals.

Gluttony wallowed in its nauseous excesses at tables spread in the halls of the mighty. The everyday dinner of a man of rank ran from fifteen to twenty dishes; England’s earl of Warwick, who fed as many as five hundred guests at a sitting, used six oxen a day at the evening meal. The oxen were not as succulent as they sound; by tradition, the meat was kept salted in vats against the possibility of a siege, and boiled in a great copper vat. Even so, enormous quantities of it were ingested and digested. On special occasions a whole stag might be roasted in the great fireplace, crisped and larded, then cut up in quarters, doused in a steaming pepper sauce, and served on outsized plates.

The hearth excepted, the home of a prosperous peasant lacked these amenities. Lying at the end of a narrow, muddy lane, his

Home of a medieval nobleman

rambling edifice of thatch, wattles, mud, and dirty brown wood was almost obscured by a towering dung heap in what, without it, would have been the front yard. The building was large, for it was more than a dwelling. Beneath its sagging roof were a pigpen, a henhouse, cattle sheds, corncribs, straw and hay, and, last and least, the family’s apartment, actually a single room whose walls and timbers were coated with soot. According to Erasmus, who examined such huts, “almost all the floors are of clay and rushes from the marshes, so carelessly renewed that the foundation sometimes remains for twenty years, harboring, there below, spittle and vomit and wine of dogs and men, beer … remnants of fishes, and other filth unnameable. Hence, with the change of weather, a vapor exhales which in my judgment is far from wholesome.”

The centerpiece of the room was a gigantic bedstead, piled high with straw pallets, all seething with vermin. Everyone slept there, regardless of age or gender—grandparents, parents, children, grandchildren, and hens and pigs—and if a couple chose to enjoy intimacy, the others were aware of every movement. In summer they could even watch. If a stranger was staying the night, hospitality required that he be invited to make “one more” on the familial mattress. This was true even if the head of the household was away, on, say, a pilgrimage. If this led to goings-on, and the husband returned to discover his wife with child, her readiest reply was that during the night, while she was sleeping, she had been penetrated by an incubus. Theologians had confirmed that such monsters existed and that it was their demonic mission to impregnate lonely women lost in slumber. (Priests offered the same explanation for boys’ wet dreams.) Even if the infant bore a striking similarity to someone other than the head of the household, and tongues wagged as a result, direct accusations were rare. Cuckolds were figures of fun; a man was reluctant to identify himself as one. Of course, when unmarried girls found themselves with child and told the same tale, they met with more skepticism.

If this familial situation seems primitive, it should be borne in mind that these were prosperous peasants. Not all their neighbors were so lucky. Some lived in tiny cabins of crossed laths stuffed with grass or straw, inadequately shielded from rain, snow, and wind. They lacked even a chimney; smoke from the cabin’s fire left through a small hole in the thatched roof—where, unsurprisingly, fires frequently broke out. These homes were without glass windows or shutters; in a storm, or in frigid weather, openings in the walls could only be stuffed with straw, rags—whatever was handy. Such families envied those enjoying greater comfort, and most of all they coveted their beds. They themselves slept on thin straw pallets covered by ragged blankets. Some were without blankets. Some didn’t even have pallets.

Typically, three years of harvests could be expected for one year of famine. The years of hunger were terrible. The peasants might be forced to sell all they owned, including their pitifully inadequate clothing, and be reduced to nudity in all seasons. In the hardest times they devoured bark, roots, grass; even white clay. Cannibalism was not unknown. Strangers and travelers were waylaid and killed to be eaten, and there are tales of gallows being torn down—as many as twenty bodies would hang from a single scaffold—by men frantic to eat the warm flesh raw.

However, in the good years, when they ate, they ate. To avoid dining in the dark, there were only two meals a day—“dinner” at 10 A.M. and “supper” at 5 P.M.—but bountiful harvests meant tables which groaned. Although meat was rare on the Continent, there were often huge pork sausages, and always enormous rolls of black bread (white bread was the prerogative of the patriciate) and endless courses of soup: cabbage, watercress, and cheese soups; “dried peas and bacon water,” “poor man’s soup” from odds and ends, and during Lent, of course, fish soup. Every meal was washed down by flagons of wine in Italy and France, and, in Germany or England, ale or beer. “Small beer” was the traditional drink, though since the crusaders’ return from the East many preferred “spiced beer,” seasoned with cinnamon, resin, gentian, and juniper. Under Henry VII and Henry VIII the per capita allowance was a gallon of beer a day—even for nuns and eight-year-old children. Sir John Fortescue observed that the English “drink no water, unless at certain times upon religious score, or by way of doing penance.”

THIS MUST HAVE LED to an exceptional degree of intoxication, for people then were small. The average man stood a few inches over five feet and weighed about 135 pounds. His wife was shorter and lighter. Anyone standing several inches over six feet was considered a giant and inspired legends—Jack the Giant Killer, for example, and Jack and the Beanstalk. Folklore was rich in such violent tales, for death was their constant companion. Life expectancy was brief; half the people in Europe died, usually from disease, before reaching their thirtieth birthday. It was still true, as Richard Rolle had written earlier, that “few men now reach the age of forty, and fewer still the age of fifty.” If a man passed that milestone, his chances of reaching his late forties or his early fifties were good, though he looked much older; at forty-five his hair was as white, back as bent, and face as knurled as an octogenarian’s today. The same was true of his wife—“Old Gretel,” a woman in her thirties might be called. In longevity she was less fortunate than her husband. The toll at childbirth was appalling. A young girl’s life expectancy was twenty-four. On her wedding day, traditionally, her mother gave her a piece of fine cloth which could be made into a frock. Six or seven years later it would become her shroud.

Clothing served as a kind of uniform, designating status. Some raiment was stigmatic. Lepers were required to wear gray coats and red hats, the skirts of prostitutes had to be scarlet, public penitents wore white robes, released heretics carried crosses sewn on both sides of their chests—you were expected to pray as you passed them—and the breast of every Jew, as stipulated by law, bore a huge yellow circle. The rest of society belonged to one of the three great classes: the nobility, the clergy, and the commons. Establishing one’s social identity was important. Each man knew his place, believed it had been foreordained in heaven, and was aware that what he wore must reflect it.

To be sure, certain fashions were shared by all. Styles had changed since Greece and Rome shimmered in their glory; then garments had been wrapped on; now all classes put them on and fastened them. Most clothing—except the leather gauntlets and leggings of hunters, and the crude animal skins worn by the very poor—was now woven of wool. (Since few Europeans possessed a change of clothes, the same raiment was worn daily; as a consequence, skin diseases were astonishingly prevalent.) But there was no mistaking the distinctions between the parson in his vestments; the toiler in his dirty cloth tunic, loose trousers, and heavy boots; and the aristocrat with his jewelry, his hairdress, and his extravagant finery. Every knight wore a signet ring, and wearing fur was as much a sign of knighthood as wearing a sword or carrying a falcon. Indeed, in some European states it was illegal for anyone not nobly born to adorn himself with fur. “Many a petty noble,” wrote historian W. S. Davis, “will cling to his frayed tippet of black lambskin, even in the hottest weather, merely to prove that he is not a villein.”

Furred (and feathered) hats were favored by patricians; so were flowered robes and fancy jackets bulging at the sleeves. It was considered appropriate for the nobly born to flaunt the distinguishing marks of their sex. This had not changed since the death of Chaucer a century earlier. Chaucer himself—who as a page had worn a flaming costume with one hose red and one black—nevertheless deplored, in The Canterbury Tales, the custom of wearing trousers with codpieces over the genitalia. This flaunting of “shameful privee membres,” he wrote, by men with “horrible swollen membres that they shewe thugh disgisynge [disguise],” also made “the buttokes … as it were, the hyndre part of a sheape in the fulle of the moone.”

He was even more offended by “the outrageous array of wommen, God wot that the visages of somme of them seem ful chaste and debonaire, yet notifie they” by “the horrible disordinate scantinesse” of their dress their “likerousnesse [lecherousness] and pride.” Both sexes were advertising, not flirting, and they were certainly not bluffing; when challenged, by all accounts, they responded eagerly.

IT WAS A TIME when the social lubricants of civility, and the small but essential trivia of civilized life, were just beginning to re-emerge, phoenixlike, from the medieval ashes. Learning, like etiquette, was being rediscovered. For example, the arithmetic symbols + and − did not come back into general use until the late 1400s. Spectacles for the shortsighted were unavailable until around 1520. Lead pencils had appeared at the turn of the century, together with the first postal service (between Vienna and Brussels). However, Peter Henlein’s “Nuremberg Egg,” the first watch, said to have been invented in 1502, is now regarded as a myth. Small table clocks and watches, telling time to the hour, would not begin to appear in Italy and Germany until the last quarter of the century. Bartolomew Newsam is said to have built the first English standing clock in 1585.

In all classes, table manners were atrocious. Men behaved like boors at meals. They customarily ate with their hats on and frequently beat their wives at table, while chewing a sausage or gnawing at a bone. Their clothes and their bodies were filthy. The story was often told of the peasant in the city who, passing a lane of perfume shops, fainted at the unfamiliar sent and was revived by holding a shovel of excrement under his nose. Pocket handkerchiefs did not appear until the early 1500s, and it was midcentury before they came into general use. Event sovereigns wiped their noses on their sleeves, or, more often, on their footmen’s sleeves. Napkins were also unknown; guests were warned not to clean their teeth on the tablecloth. Guests in homes were also reminded that they should blow their noses with the hand that held the knife, not the one holding the food.

There is some dispute about when cutlery was introduced. Apparently knives were first provided by guests, who carried them in sheaths attached to their belts. According to Erasmus, decorum dictated that food be brought to the mouth with one’s fingers. The fork is mentioned in the fifteenth century, but was used then only to serve dishes. As tableware it was not laid out in the French court until 1589, though it had appeared at a Venetian ducal banquet in 1520; writing in his diary afterward, Jacques LeSaige, a French silk merchant who had been among the guests, noted with wonder: “These seigneurs, when they want to take the meat up, use a silver fork.”

There was such a thing as bad form, but it had nothing to do with manners. Any breach of rules established by the Church was a grave offense. Except for the Jews, of whom there were perhaps a million in Europe, every European was expected to venerate, above all others, the Virgin Mary—Queen of the Holy City, Lady of Heaven, la Beata Vergine, die heilige Jungfrau, la Virgen María, la Dame débonnaire—followed by her vassals, the Catholic saints, who did her liege homage. Parishioners were required to hear Mass at least once a week (for knights it was daily); to hate the Saracens and, of course, the Jews; to honor holy places and sacred objects; and to keep the major fasts.

Fasts were the greatest challenge faced by the faithful, and not all were equal to it. In one Breton village the devout affirmed their Lenten piety by joining a procession led by a priest. Afterward one marching woman, who had worn a particularly saintly expression during the parade, retired to her kitchen and elatedly broke Lent by heating, and eating, mutton and ham. The aroma drifted out the window. It was identified by passersby. Seized, she was brought before the local bishop, who sentenced her to walk the village streets until Easter, a month away, with the ham slung around her neck and the quarter of mutton, on its spit, over her shoulder. Ineluctably—and another sign of the age—a jeering mob followed her every step.

THAT WAS a relatively minor infraction. Greater crimes provoked awesome rites. A drunken, irreverent baron found himself in deep trouble after stealing the chalice of a parish church. He had been seen galloping away with it. The local bishop ordered the church bell tolled in the mournful cadence usually reserved for major funerals. The church itself was draped in black. The congregation gathered in the nave. Amid a frightful hush the prelate, surrounded by his clergymen, each carrying a lighted candle, appeared in the chancel and pronounced the name of the thief, shouting: “Let him be cursed in the city and cursed in the field; cursed in his granary, his harvest, and his children; as Dathan and Abiram were swallowed up by the gaming earth, so may hell swallow him. And even as today we quench these torches in our hands, so may the light of his life be quenched for all eternity, unless he do repent!”

As the priests flung their candles down and stamped them out, the parishioners trembled for the knight’s soul, which, they knew, had very little chance of surviving so awful an imprecation. The wayward baron was now an outlaw; every man’s hand was against him; neither lepers nor Jews were so completely isolated. This social exile was a formidable weapon, and it brought the sinner to his knees, for eventually he bought back his salvation—at a formidable price. First he donated his entire fortune to the bishop. Then he appeared at the chancel barefoot, wearing a pilgrim’s robe. For twenty-four hours he lay prostrate before the high altar, praying and fasting; then he knelt while sixty monks and priests clubbed him. As each blow fell he yelled, “Just are thy judgments, O Lord!” At last, when he lay bleeding, bones broken and senses impaired, the bishop absolved him and gave him the kiss of peace.

The punishment seems excessive. Such a chalice, not fashioned from precious metal, had little monetary value; its theft had merely been an act of petty larceny. But the medieval Church was strong on law and order, and had this felony gone unpunished, the aftermath could have led to laxity, backsliding, even mutiny. Besides, there were greater sinners than the scourged baron, and crueler penances. For them the road to atonement was literally a series of roads, to be covered, over six, ten, or even twelve years in that greatest of penances, the pilgrimage.

In instances in which pilgrims had offended God and man, their journeys were actually a substitute for prison terms. European castles had dungeons—so did the Vatican—but they couldn’t begin to hold the miscreant population. The chief legal penalty was execution. There were alternatives in lay courts—ears were cut off, tongues ripped out, eyes gouged from their sockets; the genitalia of wives who had betrayed their husbands were cauterized with white-hot tongs—but these, although extremely unpleasant, offered no hope for salvation. The violator still faced a writhing afterlife in Hades, and obviously everyone who had violated the law did not deserve that. Therefore the Church, which had its own legal system, paralleling secular courts, took over.

Offenders were ordered to shave their heads, abandon their families, fast constantly (meat only once a day), and set out barefoot for a far destination. Journey’s end varied from offender to offender. Rome was a popular choice. Some were sent all the way to Jerusalem. The general rule was the longer the distance, the greater the atonement. If of noble birth, the penitent had to wear chains on his neck and wrists forged from his own armor, a sign of how far he had fallen. Frequently the felon carried a passport, signed by a bishop, specifying his crimes in the grimmest possible detail and then asking good Christians to offer him food and lodging. From the felon’s point of view this approach may have seemed flawed, but his opinion was unsolicited. And ecclesiastical verdicts could seldom be appealed.

Some men, in their search for absolution, suffered almost unendurable ordeals. The notorious Count Fulk the Black of Anjou, whose crimes were legendary, finally realized that his immortal soul was in peril and, while miserable in the throes of his conscience, begged for divine mercy. Count Fulk had sinned for twenty years. Among other things he had murdered his wife, though this charge had been dropped on the strength of his unsupported word that he had found her rutting behind a barn with a goatherd. The court felt helpless here. Decapitation on the spot was the fate of an adulteress caught in the act; adulterers usually went free, to be dealt with by the husbands they had wronged. In this case there had been no witnesses, and the goatherd had vanished, but counts, even wicked counts, did not lie. However, quite apart from that, Fulk the Black’s catalog of crimes was a long one. He expected a heavy sentence, and that is what he got. He is said to have fainted when it was passed. Shackled, he was condemned to a triple Jerusalem pilgrimage: across most of France and Savoy, over the Alps, through the Papal States, Carinthia, Hungary, Bosnia, mountainous Serbia, Bulgaria, Constantinople, and the length of mountainous Anatolia, then down through modern Syria and Jordan to the holy city. In irons, his fleet bleeding, he made this round trip three times—15,300 miles—and the last time he was dragged through the streets on a hurdle while two well-muscled men lashed his naked back with bullwhips.

THE COUNT could have asked, though he didn’t, what all this misery had to do with the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. In fact it had nothing to do with them. The distinction between devotion and superstition has always been unclear, but there was little blurring here. Although they called themselves Christians, medieval Europeans were ignorant of the Gospels. The Bible existed only in a language they could not read. The mumbled incantations at Mass were meaningless to them. They believed in sorcery, witchcraft, hobgoblins, werewolves, amulets, and black magic, and were thus indistinguishable from pagans. If a lady died, the instant her breath stopped servants ran through the manor house, emptying every container of water to prevent her soul from drowning, and before her funeral the corpse was carefully watched to prevent any dog or cat from running across the coffin, thus changing her remains into a vampire. Meantime her lord, praying for her salvation, was lying prostrate, his head turned eastward and his arms stretched out, forming a cross. Nothing in the New Testament supported such delusions and rituals; nevertheless the precautions were taken—with the blessings of the clergy. In monastic manuscripts one repeatedly finds such entries as: “Common report has it that Antichrist has been born at Babylon and that the Day of Judgment is nigh.” The alarm was spread so often that the peasants ignored it; on the Sabbath, after an early Mass, they would gossip, dance, sing, wrestle, race, and compete in archery contests until evening shadows deepened. There was hell enough on earth for them; they were too drained to ponder the risks of another world.

Nevertheless in pensive moments they worried. Should the left eye of a corpse not close properly, they knew, the departed would soon have company in purgatory. If a man donned a clean white shirt on a Friday, or saw a shooting star, or a will-o’-the-wisp in the marshes, or a vulture hovering over his home, his death was very near. Similarly, a woman stupid enough to wash clothes during Holy Week would soon be in her grave. Should thirteen people be so thoughtless as to sup at one table, one of those present would not be there for tomorrow morning’s meal; if a wolf howled through the night, one who heard him would disappear before dawn. Comets and eclipses were sinister. Everyone knew that an enormous comet had been sighted in July 1198 and Richard the Lion-Hearted had died “very soon after.” (In fact he did not die until April 6, 1199.)

Everyone also knew—and every child was taught—that the air all around them was infested with invisible, soulless spirits, some benign but most of them evil, dangerous, long-lived, and hard to kill; that among them were the souls of unbaptized infants, ghouls who snuffled out cadavers in graveyards and chewed their bones, water nymphs skilled at luring knights to death by drowning, dracs who carried little children off to their caves beneath the earth, wolfmen—the undead turned into ravenous beasts—and vampires who rose from their tombs at dusk to suck the blood of men, women, or children who had strayed from home. At any moment, under any circumstances, a person could be removed from the world of the senses to a realm of magic creatures and occult powers. Every natural object possessed supernatural qualities. Books interpreting dreams were highly popular.

The stars were known to be guided by angels, and physicians were constantly consulting astrologers and theologians. Doctors diagnosing illnesses were influenced by the constellation under which the patient had been born or taken sick; thus the eminent surgeon Guy de Chauliac wrote: “If anyone is wounded in the neck when the moon is at Taurus, the affliction will be dangerous.” Thousands of pitiful people disfigured by swollen lymph nodes in their necks mobbed the kings of England and France, believing that their scrofula could be cured by the touch of a royal hand. One document from the period is a calendar, published at Mainz, which designates the best astrological times for bloodletting. Epidemics were attributed to unfortunate configurations of the stars. Now and then a quack was unmasked; in London one Roger Clerk, who had pretended to cure ailments with spurious charms, was sentenced to ride through the city with urinals hanging from his neck. But others, equally bogus, lived out their lives unchallenged.

Scholars as eminent as Erasmus and Sir Thomas More accepted the existence of witchcraft. Conspicuous fakes excepted, the Church encouraged superstitions, recommended trust in faith healers, and spread tales of satyrs, incubi, sirens, cyclops, tritons, and giants, explaining that all were manifestations of Satan. The Prince of Darkness, it taught, was as real as the Holy Trinity. Certainly belief in him was useful; prelates agreed that when it came to keeping the masses on the straight and narrow, fear of the devil was a stronger force than the love of God. Great shows were made of exorcisms. The story spread across the continent of how the fiend entered a man’s body and croaked blasphemy through his mouth until a priest, following a magic rite, recited an incantation. The devil, foiled, screamed horribly and fled.

The ecclesiastical hierarchy, through its priests and monks, repeatedly affirmed the legitimacy of specific miracles. Unshriven sinners were not the only pilgrims on Europe’s roads. In fact, they were a minority. The majority were simple people, identifiable by their brown wool robes, heavy staffs, and sacks slung from their belts. Their motivation was simple devotion, often concern for a recently departed relative now in purgatory. Although filthy and untidy, they were rarely abused; few wanted to lose the scriptural blessing reserved for those who, having shown kindness to a stranger, had “entertained angels unawares.”

Pilgrims headed for over a thousand shrines whose miracles had been recognized by Rome. There was Our Lady of Chartres, Our Lady of the Rose at Lucca, Our Guardian Lady in Genoa, and other Our Ladies at Le Puy, Auray, Grenoble, Valenciennes, Liesse, Rocamadour, Ossier. … It went on and on. One popular destination was the tomb of Pierre de Luxembourg, a cardinal who had died, aged eighteen, of anorexia; within fifteen months of his death 1,964 miracles were credited to the magic he had left in his bones. Some saints were regarded as medical specialists; victims of cholera headed for a chapel of Saint Vitus, who was believed to be particularly efficacious for that disease.

But nothing could compete with the two star attractions: scenes actually visited by the savior himself and spectacular phenomena confirmed by the Vatican. At Santa Maria Maggiore, people were told, they could see the actual manger where Christ was born, or, at St. John Lateran, the holy steps Jesus ascended while wearing his crown of thorns, or, at St. Peter in Montorio, the place where Peter was martyred by Nero. Englishmen believed that the venerable abbot of St. Germer need only bless a fountain and lo! its waters would heal the sick, restore sight to the blind, and make the dumb speak. Once, according to pilgrims, the abbot had visited a village parched for lack of water. He led the peasants into the church, and, as they watched, smote a stone with his staff. Behold! Water gushed forth, not only to slake thirsts but also possessing miraculous powers to cure all pain and illness.

TRAVEL WAS slow, expensive, uncomfortable—and perilous. It was slowest for those who rode in coaches, faster for walkers, and fastest for horsemen, who were few because of the need to change and stable steeds. The expenses chiefly arose from the countless tolls, the discomfort from a score of irritants. Bridges spanning rivers were shaky (priests recommended that before crossing them travelers commend themselves to God); other streams had to be forded; the roads were deplorable—mostly trails and muddy ruts, impassable, except in summer, by two-wheeled carts—and nights en route had to be spent in Europe’s wretched inns. These were unsanitary places, the beds wedged against one another, blankets crawling with roaches, rats, and fleas; whores plied their trade and then slipped away with a man’s money, and innkeepers seized guests’ baggage on the pretext that they had not paid.

The peril came from highwaymen, whose mythic joys and miseries were celebrated by the Parisian François Villon. In reality there was nothing attractive about these criminals in the woods. They were pitiless thieves, kidnappers, and killers, and they flourished because they were so seldom pursued. Between towns the traveler was on his own. Except in a few places like Castile, where roads were patrolled by the archers of the Santa Hermandad, no policemen were stationed in the open country. Outlaws had always lurked in the woods, but their menace had increased as their ranks were thickened by impoverished knights returning from the illstarred crusades, demobilized veterans of various foreign campaigns, and, in England, renegades from the recent War of the Roses. Sometimes these brigands traveled in roving gangs, waiting to ambush strangers; sometimes they stood by the road disguised as beggars or pilgrims, knives at the ready. Even gallant seigneurs declined responsibility for travelers passing through their lands at night, and many a less-principled sire was either a bandit himself or an accomplice of outlaws, overlooking their outrages provided they hold important personages harmless and present him with lavish gifts at Christmas.

Therefore honest travelers carried well-honed daggers, knowing they might have to kill and hoping they would have the stomach for it. Wayfarers from different lands usually banded together, seeking collective security, though they often excluded Englishmen, who in that age were distrusted, suspected of petty thefts, regarded by seamen as pirates, and notorious for the false weights and shoddy goods of their merchants. Even Britons like Chaucer, who denounced greed, were themselves greedy. Their women were unwelcome for another reason. They were so foul-mouthed that Joan of Arc always referred to them as “the Goddams.” And the English of both sexes were known, even then, for their insolence. In 1500 the Venetian ambassador to London reported to his government that his hosts were “great lovers of themselves, and of everything belonging to them; they think there are no other men than themselves, and no other country but England; and whenever they see a handsome foreigner they say that ‘he looks like an Englishman,’ and that it is a great pity that he is not one.”

Doubtless the same thing could be said, mutatis mutandis, of other people, but Englishmen, aware of their reputation, always went abroad heavily armed—unless they were rich. Surrounded by bands of knights in full armor, wealthy Europeans traveled in painted, gilded, carved, and curtained horse-drawn coaches. They knew they were marks for thieves, and never left their fiefs to visit cities, or attend the great August fairs, unless heavily guarded.

A YORKSHIRE gravestone bears this inscription:

Hear underneath dis laihl stean

las Robert earl of Huntingtun

neer arcir yer az hie sa geud

And pipl kauld in Robin Heud

sick utlawz as he an iz men

il england nivr si agen

Obiit 24 kal Decembris 1247

Robin Hood lived; this marker confirms it, just as the Easter tables attest to the existence of the great Arthur. But that is all the tombstone does. Everything we know about that period suggests that Robin was merely another wellborn cutthroat who hid in shrubbery by roadsides, waiting to rob helpless wayfarers. The possibility that he stole from the rich and gave to the poor is, like the tale of that other cold-blooded rogue, Jesse James, highly unlikely. Even unlikelier is the conceit that Robin Hood, aka Heud, was accompanied by a bedmate called Maid Marian, a giant known as Little John, and a lapsed Catholic named Friar Tuck. Almost certainly they were creatures of an ingenious folk imagination, and their contemporary, the sheriff of Nottingham, is probably the most libeled law enforcement officer in this millennium.

The more we study those remote centuries, the unlikelier such legends become. Later mythmakers invested the Middle Ages with a bogus aura of romance. The Pied Piper of Hamelin is an example. He was a real man, but there was nothing enchanting about him. Quite the opposite; he was horrible, a pyschopath and pederast who, on June 20, 1484, spirited away 130 children in the Saxon village of Hammel and used them in unspeakable ways. Accounts of the aftermath vary. According to some, his victims were never seen again; others told of dismembered little bodies found scattered in the forest underbrush or festooning the branches of trees.

The most imaginative cluster of fables appeared in print the year after the Piper’s mass murders, when William Caxton published Sir Thomas Malory’s Le morte d’Arthur. Later, bowdlerized versions of this great work have obscured the fact that Malory, contemplating medieval morality, seldom wore blinders. He had no illusions about his heroine when he wrote: “There syr Launcelot toke the Fayrest Ladie by the hand, and she was naked as a nedel.” Some of his characters may actually have existed. For over a thousand years villagers in remote parts of Wales have called an adulteress “a regular Guinevere.” But Launcelot du Lac is entirely fictitious, and given the colossal time sprawl of the Middle Ages, it is highly unlikely that Guinevere, if indeed she lived, even shared the same century with Arthur.

WE KNOW LITTLE of the circumstances under which Magellan and his Beatriz were married in 1517, but if they were united by transcendental love, they were an odd couple. It is true that a young archduke in Vienna’s imperial court had introduced the diamond ring as a sign of engagement forty years earlier, but its vogue had been confined to the patriciate, and even there it had found little favor. Typically, news of an imminent marriage spread when the pregnancy of the bride-elect began to show. If she had been particularly user-friendly, raising genuine doubts about the child’s paternity, those who had enjoyed her favors drew straws. “Virginity,” one historian of the period writes, “had to be protected by every device of custom, morals, law, religion, paternal authority, pedagogy, and ‘point of honor’; yet somehow it managed to get lost.”

No one was actually scandalized; the normal, eternal reproductive instincts were merely asserting themselves. But such random matrimony disappointed parents; a girl’s wedding was the pivotal event in her life, and its economic implications—the ceremony was among other things a merging of belongings—concerned both families. The tradition of arranged marriages, sensibly conceived, was obviously crumbling. Commentators of the time, believing that the old way was best, were troubled. In his Colloquia familiaria (Colloquies) Erasmus recommended that youths let fathers choose their brides and trust that love would grow as acquaintance ripened. Even Rabelais agreed in Le cinquiesme et dernier livre. Couples who kicked over the traces were reproached in The Schole-master by Roger Ascham, tutor to England’s royal family. Ascham bitterly regretted that “our time is so far gone from the old discipline and obedience as now not only young gentlemen but even very young girls dare … marry themselves in spite of father, mother, God, good order, and all.” At the University of Wittenberg, Martin Luther, dismayed that the son of a faculty colleague had plighted his troth without consulting his father—and that a young judge had found the vow legal—thought the reputation of the institution was being tarnished. He wrote: “Many parents have ordered their sons home … saying that we hang wives around their necks. … The next Sunday I preached a strong sermon, telling men to follow the common road and manner which had been since the beginning of the world … namely, that parents should give their children to each other with prudence and good will, without their own preliminary arrangement.”

Females could marry—legally, with or without parental consent—when they reached their twelfth birthday. The age for males was fourteen. Even before she had reached her teens, a girl knew that unless she married before she was twenty-one, society would consider her useless, fit only for the nunnery, or, in England, the spinning wheel (a “spinster”). Hence the yearning of female adolescents for the altar. Getting pregnant was one way to reach it. On Sundays, under watchful parental eyes, girls would dress modestly and be demure in church, but on weekdays they opened their blouses, hiked their skirts, and romped through the fields in pursuit of phalli.

Another five centuries would pass before young women would be so open in their pursuit of sex. In Wittenberg Luther complained that “the race of girls is getting bold, and run after the fellows into their rooms and chambers and wherever they can and offer them their free love.” Later he fumed that young women had become “immodest, shameless. … The young people of today are utterly dissolute and disorderly. … The women and girls of Wittenberg have begun to go bare before and behind, and there is no one to punish or correct them.” If the lover of a soon-to-be unwed mother decided he was not ready for marriage, her cause was not necessarily lost; often an attractive girl with a fatherless child and a long record of indiscretions could find a respectable peasant willing to take her to the altar.

In this lusty age the most a parent could extract from a daughter was her promise not to yield until the banns had been read. Once a couple was engaged, they slept together with society’s approval. If a peasant girl was not pregnant, there were only two practical deterrents to her acceptance of a marriage proposal. It was her desire either to enter a convent or, at the far end of the spectrum, to join the world’s oldest profession. Harlotry not only paid well; it was frequently prestigious. Because prostitutes had to expose their entire bodies, they were the cleanest people in Europe. The competition was fierce, but it always had been, and once established, these women became what were now being called courtesans (from the Italian courtigiane), or female courtiers. Moves to suppress them were rare and unpopular; Luther lost many followers when, though affirming the normality of sexual desire, he proclaimed that the sale of sex was wrong and persuaded several German cities to outlaw it.