I

THE MEDIEVAL MIND

THE DENSEST of the medieval centuries—the six hundred years between, roughly, A.D. 400 and A.D. 1000—are still widely known as the Dark Ages. Modern historians have abandoned that phrase, one of them writes, “because of the unacceptable value judgment it implies.” Yet there are no survivors to be offended. Nor is the term necessarily pejorative. Very little is clear about that dim era. Intellectual life had vanished from Europe. Even Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman emperor and the greatest of all medieval rulers, was illiterate. Indeed, throughout the Middle Ages, which lasted some seven centuries after Charlemagne, literacy was scorned; when a cardinal corrected the Latin of the emperor Sigismund, Charlemagne’s forty-seventh successor, Sigismund rudely replied, “Ego sum rex Romanus et super grammatica”—as “king of Rome,” he was “above grammar.” Nevertheless, if value judgments are made, it is undeniable that most of what is known about the period is unlovely. After the extant fragments have been fitted together, the portrait which emerges is a mélange of incessant warfare, corruption, lawlessness, obsession with strange myths, and an almost impenetrable mindlessness.

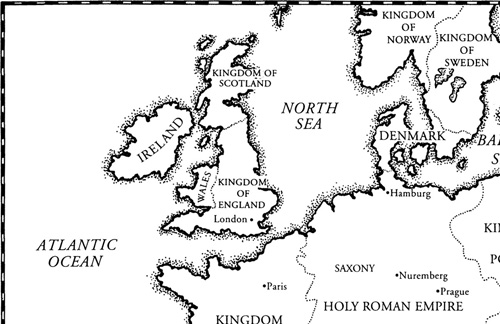

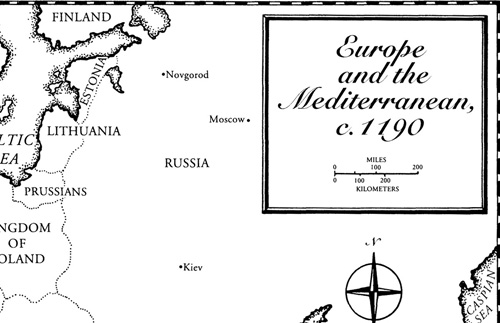

Europe had been troubled since the Roman Empire perished in the fifth century. There were many reasons for Rome’s fall, among them apathy and bureaucratic absolutism, but the chain of events leading to its actual end had begun the century before. The defenders of the empire were responsible for a ten-thousand-mile frontier. Ever since the time of the soldier-historian Tacitus, in the first century A.D., the vital sector in the north—where the realm’s border rested on the Danube and the Rhine—had been vulnerable. Above these great rivers the forests swarmed with barbaric Germanic tribes, some of them tamer than others but all envious of the empire’s prosperity. For centuries they had been intimidated by the imperial legions confronting them on the far banks.

Now they no longer were. They had panicked, stampeded by an even more fearsome enemy in their rear: feral packs of mounted Hsiung-nu, or Huns. Ignorant of agriculture but expert archers, bred to kill and trained from infancy to be pitiless, these dreaded warriors from the plains of Mongolia had turned war into an industry. “Their country,” it was said of them, “is the back of a horse.” It was Europe’s misfortune that early in the fourth century the Huns had met their masters at China’s Great Wall. Defeated by the Chinese, they had turned westward, entered Russia about A.D. 355, and crossed the Volga seventeen years later. In 375 they fell upon the Ostrogoths (East Goths) in the Ukraine. After killing the Ostrogoth chieftain, Ermanaric, they pursued his tribesmen across eastern Europe. An army of Visigoths (West Goths) met the advancing Huns on the Dniester, near what is now Romania. The Goths were cut to pieces. The survivors among them — some eighty thousand—fled toward the Danube and crossed it, thereby invading the empire. On instructions from the Emperor Valens, imperial commanders charged with defense of the frontier first disarmed the Gothic refugees, next admitted them subject to various conditions, then tried to enslave them, and finally, in A.D. 378, fought them, not with Roman legions, but using mercenaries recruited from other tribes. Caesar would have wept at the spectacle that followed. In battle the mercenaries were overconfident and slack; according to Ammianus Marcellinus, Tacitus’s Greek successor, the result was “the most disastrous defeat encountered by the Romans since Cannae”—six centuries earlier.

Under the weight of relentless attacks by the combined barbaric tribes and the Huns, now Gothic allies, the Danube-Rhine line broke along its entire length and then collapsed. Plunging deeper and deeper into the empire, the invaders prepared to penetrate Italy. In 400 the Visigoth Alaric, a relatively enlightened chieftain and a zealous religieux, led forty thousand Goths, Huns, and freed Roman slaves across the Julian Alps. Eight years of fighting followed. Rome’s cavalry was no match for the tribal horsemen; two-thirds of the imperial legions were slain. In 410 Alaric’s triumphant warriors swept down to Rome itself, and on August 24 they entered it.

Thus, for the first time in eight centuries, the Eternal City fell to an enemy army. After three days of pillage it was battered almost beyond recognition. Alaric tried to spare Rome’s citizens, but he could not control the Huns or the former slaves. They slaughtered wealthy men, raped women, destroyed priceless pieces of sculpture, and melted down works of art for their precious metals. That was only the beginning; sixty-six years later another Germanic chieftain deposed the last Roman emperor in the west, Romulus Augustulus, and proclaimed himself ruler of the empire. Meantime Gunderic’s Vandals, Clovis’s Franks, and most of all the Huns under their terrible new chieftain Attila—who had seized power by murdering his brother—ravaged Gaul as far south as Paris, paused, and lunged into Spain. In the years that followed, Goths, Alans, Burgundians, Thuringians, Frisians, Gepidae, Suevi, Alemanni, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Lombards, Heruli, Quadi, and Magyars joined them in ravaging what was left of civilization. The ethnic tide then settled in its conquered lands and darkness descended upon the devastated, unstable continent. It would not lift until forty medieval generations had suffered, wrought their pathetic destinies, and passed on.

THE DARK AGES were stark in every dimension. Famines and plague, culminating in the Black Death and its recurring pandemics, repeatedly thinned the population. Rickets afflicted the survivors. Extraordinary climatic changes brought storms and floods which turned into major disasters because the empire’s drainage system, like most of the imperial infrastructure, was no longer functioning. It says much about the Middle Ages that in the year 1500, after a thousand years of neglect, the roads built by the Romans were still the best on the continent. Most others were in such a state of disrepair that they were unusable; so were all European harbors until the eighth century, when commerce again began to stir. Among the lost arts was bricklaying; in all of Germany, England, Holland, and Scandinavia, virtually no stone buildings, except cathedrals, were raised for ten centuries. The serfs’ basic agricultural tools were picks, forks, spades, rakes, scythes, and balanced sickles. Because there was very little iron, there were no wheeled plowshares with moldboards. The lack of plows was not a major problem in the south, where farmers could pulverize light Mediterranean soils, but the heavier earth in northern Europe had to be sliced, moved, and turned by hand. Although horses and oxen were available, they were of limited use. The horse collar, harness, and stirrup did not exist until about A.D. 900. Therefore tandem hitching was impossible. Peasants labored harder, sweated more, and collapsed from exhaustion more often than their animals.

Surrounding them was the vast, menacing, and at places impassable, Hercynian Forest, infested by boars; by bears; by the hulking medieval wolves who lurk so fearsomely in fairy tales handed down from that time; by imaginary demons; and by very real outlaws, who flourished because they were seldom pursued. Although homicides were twice as frequent as deaths by accident, English coroners’ records show that only one of every hundred murderers was ever brought to justice. Moreover, abduction for ransom was an acceptable means of livelihood for skilled but landless knights. One consequence of medieval peril was that people huddled closely together in communal homes. They married fellow villagers and were so insular that local dialects were often incomprehensible to men living only a few miles away.

The level of everyday violence—deaths in alehouse brawls, during bouts with staves, or even in playing football or wrestling —was shocking. Tournaments were very different from the romantic descriptions in Malory, Scott, and Conan Doyle. They were vicious sham battles by large bands of armed knights, ostensibly gatherings for enjoyment and exercise but really occasions for abduction and mayhem. As late as the year 1240, in a tourney near Düsseldorf, sixty knights were hacked to death.

Despite their bloodthirstiness—a taste which may have been acquired from the Huns, Goths, Franks, and Saxons—all were devout Christians. It was a paradox: the Church had replaced imperial Rome as the fixer of European frontiers, but missionaries found teaching pagans the lessons of Jesus to be an almost hopeless task. Yet converting them was easy. As quickly as the barbaric tribes had overrun the empire, Catholicism’s overrunning of the tribesmen was even quicker. As early as A.D. 493 the Frankish chieftain Clovis accepted the divinity of Christ and was baptized, though a modern priest would have found his manner of championing the Church difficult to understand or even forgive. Fortunately Clovis was accompanied by a contemporary, Bishop Gregory of Tours. The bishop made allowances for the violent streak in the Frankish character. In his writings Gregory portrayed his protégé as a heroic general whose triumphs were attributable to divine guidance. He proudly set down an account of how the chief dealt with a Frankish warrior who, during a division of tribal booty at Soissons, had wantonly swung his ax and smashed a vase. As it happened, the broken pottery had been Church property and much cherished by the bishop. Clovis knew that. Later, picking his moment, he split the warrior’s skull with his own ax, yelling, “Thus you treated the vase at Soissons!”

Medieval Christians, knowing the other cheek would be bloodied, did not turn it. Death was the prescribed penalty for hundreds of offenses, particularly those against property. The threat of capital punishment was even used in religious conversions, and medieval threats were never idle. Charlemagne was a just and enlightened ruler—for the times. His loyalty to the Church was absolute, though he sometimes chose peculiar ways to demonstrate it. Conquering Saxon rebels, he gave them a choice between baptism and immediate execution; when they demurred, he had forty-five hundred of them beheaded in one morning.

That was not remarkable. Soldiers of Christ swung their swords freely. And the victims were not always pagans. Every flourishing religion has been intermittently watered by the blood of its own faithful, but none has seen more spectacular internecine butchery than Christianity. In A.D. 330 Constantine I, the first Roman emperor to recognize Jesus as his savior, made Constantinople the empire’s second capital. Within a few years, a great many people who shared his faith began to die there for their interpretation of it. The emperor’s first Council of Nicaea failed to resolve a doctrinal dispute between Arius of Alexandria and the dominant faction of theologians. Arius rejected the Nicene Creed, taking the Unitarian position that although Christ was the son of God, he was not divine. Attempts at compromise foundered; Arius died, condemned as a heresiarch; his Arians rioted and were put to the sword. Over three thousand Christians thus died at the hands of fellow Christians—more than all the victims in three centuries of Roman persecutions. On April 13, 1204, nearly nine centuries later, medieval horror returned to Constantinople when the armies of the Fourth Crusade, embittered by their failure to reach the Holy Land, turned on the city, sacked it, destroyed sacred relics, and massacred the inhabitants.

CHRIST’S missionary commandment had been clearly set forth in Matthew (28:19–20), but in the early centuries after his crucifixion the flame of faith flickered low. Wholesale conversions of Germans, Celts, and Slavs did not begin until about A.D. 500, after Christianity had been firmly established as the state religion of the Roman Empire. Its victories were deceptive; few of its converts understood their new faith. Paganism—Stoicism, Neoplatonism, Cynicism, Mithraism, and local cults — continued to be deeply entrenched, not only in the barbaric tribes, but also among the Sophists, teachers of wisdom in the old imperial cities: Athens, Alexandria, Smyrna, Antioch, and Rome itself, which was the city of Caesar as well as Saint Peter. Constantine had tried to discourage pagan ceremonies and sacrifices, but he had not outlawed them, and they continued to flourish.

This infuriated the followers of Jesus. They were split on countless issues—Arianism, which was one of them, flourished for over half a century—but united in their determination to raze the temples of the pagans, confiscate their property, and subject them to the same official persecutions Christians had endured in the catacombs, including the feeding of martyrs to lions. This vindictiveness seems an incongruity, inconsistent with the Gospels. But medieval Christianity had more in common with paganism than its worshipers would acknowledge. The apostles Paul and John had been profoundly influenced by Neoplatonism. Of the seven cardinal virtues named by Pope Gregory I in the sixth century, only three were Christian—faith, hope, and charity —while the other four—wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance—were adopted from the pagans Plato and Pythagoras. Pagan philosophers argued that the Gospels contradicted each other, which they do, and pointed out that Genesis assumes a plurality of gods. The devout scorned reason, however. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), the most influential Christian of his time, bore a deep distrust of the intellect and declared that the pursuit of knowledge, unless sanctified by a holy mission, was a pagan act and therefore vile.

Ironically, the masterwork of Christianity’s most powerful medieval philosopher was inspired by a false report. Alaric’s sack of Rome, it was said, had been the act of a barbaric pagan seeking vengeance for his idols. (This was inaccurate; actually, Alaric and a majority of his Visigoths were Arian Christians.) Even so, the followers of Jesus were widely blamed for bringing about Rome’s fall; men charged that the ancient gods, offended by the empire’s formal adoption of the new faith, had withdrawn their protection from the Eternal City. One Catholic prelate, the bishop of Hippo—Aurelius Augustinus, later Saint Augustine —felt challenged. He devoted thirteen years to writing his response, De civitate Dei (The City of God), the first great work to shape and define the medieval mind. Augustine (354–430) began by declaring that Rome was being punished, not for her new faith, but for her old, continuing sins: lascivious acts by the populace and corruption among politicians. The pagan deities, he wrote, had lewdly urged Romans to yield to sexual passion—“the god Virgineus to loose the virgin’s girdle, Subigus to put her beneath a man’s loins, Prema to hold her down … Priapus upon whose huge and beastly member the new bride was commanded by religious order to stir and receive!”

Here Augustine, by his own account, spoke from personal experience. In his Confessions he had described how, before his conversion, he had devoted his youth to exploring the outer limits of carnal depravity. But, he wrote, the original sin, and he now declared that there was such a thing, had been committed by Adam when he yielded to Eve’s temptations. As children of Adam, he held, all mankind shared Adam’s guilt. Lust polluted every child in the very act of conception—sexual intercourse was a “mass of perdition [exitium].” However, although most people were thereby damned in the womb, some could be saved by the blessed intervention of the Virgin Mary, who possessed that power because she had conceived Christ sinlessly: “Through a woman we were sent to destruction; through a woman salvation was restored to us.” He thus drew a sharp line. The chief distinction between the old faiths and the new were in the sexual arena. Pagans had accepted prostitution as a relief from monogamy. Worshipers of Jesus vehemently rejected it, demanding instead purity, chastity, and absolute fidelity in husbands and wives. Women found this ringing affirmation enormously appealing. Aurelius Augustinus—whose influence on Christianity would be greater than that of any other man except the apostle Paul—was the first to teach medieval men that sex was evil, and that salvation was possible only through the intercession of the Madonna.

But there were subtler registers to Augustine’s mind. In his most complex metaphor, he divided all creation into civitas Dei and civitas terrena. Everyone had to embrace one of them, and a man’s choice would determine where he spent eternity. In chapter fifteen he explained: “Mankind [hominum] is divided into two sorts: such as live according to man, and such as live according to God. These we mystically call the ‘two cities’ or societies, the one predestined to reign eternally with God, the other condemned to perpetual torment with Satan.” Individual, he wrote, would slip back and forth between the two cities; their fate would be decided at the Last Judgment. Because he had identified the Church with his civitas Dei, Augustine clearly implied the need for a theocracy, a state in which secular power, symbolizing civitas terrena, would be subordinate to spiritual powers derived from God. The Church, drawing the inference, thereafter used Augustine’s reasoning as an ideological tool and, ultimately, as a weapon in grappling with kings and emperors.

THE HOLY SEE’S struggle with Europe’s increasingly powerful crowned heads became one of the most protracted in history. When Augustine finished his great work in 426, Celestine I was pope. In 1076—over a hundred pontiffs later—the issue was still unresolved. Holy Fathers in the Vatican, near Nero’s old Circus, were still fighting Holy Roman emperors, trying to end the prerogative of lay rulers to invest prelates with authority. An exasperated Gregory VII, resorting to his ultimate sanction, excommunicated Emperor Henry IV. That literally brought Henry to his knees. He begged for absolution and was granted it only after he had spent three days and nights prostrate in the snows of Canossa, outside the papal castle in northern Italy. Canossa became a symbol of secular submission, but improperly so; the emperor’s contrition was short-lived. Changing his mind, he renewed his attack, and, undeterred by a second excommunication, drove Gregory from Rome. Bitterly the pontiff wrote, “Dilexi justitiam et odi iniquitatem; propterea morior in exilio”—because he had “loved justice and hated iniquity” he would “die in exile.” Another century passed before the papacy wrested independence from the imperial courts in Germany. Even then conflicts remained, and they were not fully resolved until early in the thirteenth century, when Innocent III brought the Church to the height of its prestige and power.

Nevertheless the entire medieval millennium took on the aspect of triumphant Christendom. As aristocracies arose from the barbaric mire, kings and princes owed their legitimacy to divine authority, and squires became knights by praying all night at Christian altars. Sovereigns courting popularity led crusades to the Holy Land. To eat meat during Lent became a capital offense, sacrilege meant imprisonment, the Church became the wealthiest landowner on the Continent, and the life of every European, from baptism through matrimony to burial, was governed by popes, cardinals, prelates, monsignors, archbishops, bishops, and village priests. The clergy, it was believed, would also cast decisive votes in determining where each soul would spend the afterlife.

And yet …

The crafty but benevolent pagan gods—whose caprice and intransigence existed only in the imagination of Christian theologians eager to discredit them—survived all this. Imperial Rome having yielded to barbarians, and then barbarism to Christianity, Christianity was in turn infiltrated, and to a considerable extent subverted, by the paganism it was supposed to destroy. Medieval men simply could not bear to part with Thor, Hermes, Zeus, Juno, Cronus, Saturn, and their peers. Idol worship addressed needs the Church could not meet. Its rituals, myths, legends, marvels, and miracles were peculiarly suited to people who, living in the trackless fen and impenetrable forest, were always vulnerable to random disaster. Moreover, its creeds had never held, as the Augustinians did, that procreation was evil; pagans celebrating Aphrodite, Eros, Hymen, Cupid, and Venus could rejoice in lust. Thus the allegiance of converts was divided. Few saw any inconsistency or double-dealing in it. Hedging bets seemed only sensible. After all, it was just possible that Rome had fallen because the pagan deities had turned away from the city whose emperors no longer recognized them. What harm could come from paying token tribute to their ancient dignity? If people went to Mass and followed the commandments, there would be no retaliation from new worshipers of the savior, with their commitments to humility, mercy, tenderness, and kindness. The old genies, on the other hand, had never forgiven anyone anything, and as the Greeks had noted, the dice of the gods were always loaded.

So Christian churches were built on the foundations of pagan temples, and the names of biblical saints were given to groves which had been considered sacred centuries before the birth of Jesus. Pagan holidays still enjoyed wide popularity; therefore the Church expropriated them. Pentecost supplanted the Floralia, All Souls’ Day replaced a festival for the dead, the feast of the purification of Isis and the Roman Lupercalia were transformed into the Feast of the Nativity. The Saturnalia, when even slaves had enjoyed great liberty, became Christmas; the resurrection of Attis, Easter. There was a lot of legerdemain in this. No one then knew the year Christ was born—it was probably 5 B.C.—let alone the date. Sometime in A.D. 336 Roman Christians first observed his birthday. The Eastern Roman Empire picked January 6 as the day, but later in the same century December 25 was adopted, apparently at random. The date of his resurrection was also unrecorded. The early Christians, believing that their lord’s return was imminent, celebrated Easter every Sunday. After three hundred years their descendants became reconciled to a delay. In an attempt to link Easter with the Passion, it was sheduled on Passover, the Jewish feast observing the Exodus from Egypt in the thirteenth century B.C. Finally, in A.D. 325, after long and bitter controversy, the First Council of Nicaea settled on the first Sunday after the full moon following the spring equinox. The decision had no historical validity, but neither did the event, and it comforted those who cherished traditional holidays.

As mass baptisms swelled its congregations, the Church further indulged the converts by condoning ancient rites, or attempting to transform them, in the hope—never realized—that they would die out. Fertility rituals and augury were sanctioned; so was the sacrifice of cattle. After the pagan sacrifice of humans was replaced by Christianity’s symbolic Mass, the ceremonial performance of the sacraments became of paramount importance. Christian priests, like the pagan priests before them, also blessed harvests and homes. They even asked omnipotent God to spare communities from fire, plague, and enemy invasions. This was tempting fate, however, and medieval fate never resisted temptation for long. In time the flames, diseases, and invaders came anyway, invariably followed by outbreaks of anticlericalism, or even backsliding into such extravagant sects as the flagellants, who appeared recurrently in the wake of the Black Death. Nevertheless the traffic in holy relics, to which supernatural powers were attributed, never slackened, and Christian miracle stories continued to attribute pagan qualities to saints.

Neither Jesus nor his disciples had mentioned sainthood. The designation of saints emerged during the second and third centuries after Christ, with the Roman persecution of Christians. The survivors of the catacombs believed those who had been martyred had been received directly into heaven and, being there, could intercede for the living. They revered them as saints, but they never venerated idols of them. All the early Christians had despised idolatry, reserving special scorn for sculptures representing pagan gods. Typically, Clement of Alexandria (A.D. 150?–220?), a theologian and teacher, declared that it was sacrilege to adulate that which is created, rather than the creator. However, as the number of saints grew, so did the medieval yearning to give them identity; worshipers wanted pictures of them, images of the Madonna, and replicas of Christ on the cross. Statues of Horus, the Egyptian sky god, and Isis, the goddess of royalty, were rechristened Jesus and Mary. Craftsmen turned out other images and pictures to meet the demands of Christians who kissed them, prostrated themselves before them, and adorned them with flowers. Incense was introduced in Christian church services around 500, followed by the burning of candles. Each medieval community, in times of crisis, evoked the supposed potency of its patron saint, or of the relics it possessed.

Augustine deplored the adoration of saints, but priests and parishioners alike believed that the devil could be driven away by invoking their powers, or by making the sign of the cross. Medieval astrologers and magicians flourished. Clearly all this met a deep human need, but thoughtful men were troubled. Reaction came in the eighth century. Leo III, the deeply pious Byzantine emperor, believed it his imperial duty to defend true Christianity against all who would desecrate it. To him the adoption of pagan ways was sacrilege, and he was particularly offended by the veneration of relics and religious pictures during the celebration of Mass. After citing Deuteronomy 4:16—which forbids worship of any “graven image” or “the similitude of any figure, the likeness of male or female”—he issued a draconian edict in 726. On his orders, soldiers were to remove all icons and representations of Jesus and Mary from churches. All murals, frescoes, and mosaics were to be plastered over.

This made Leo history’s most celebrated iconoclast. It also enraged his subjects. In the Cyclades Islands they rebelled. In Venice and Ravenna they drove out imperial authorities. In Greece they elected an antiemperor and sent a fleet to capture Leo. He sank the fleet, but when his troops tried to enforce the edict, they were attacked at church doors by outraged mobs. Undeterred, in 730 the emperor proclaimed iconoclasm the official policy of the empire. But then the Church intervened. The lower clergy had opposed image breaking from its outset. They were joined by prelates, then by the patriarch of Constantinople, and, finally, by a council of bishops called by Pope Gregory II. Enforcing Leo’s edict proved impossible anyway. At his death in 741 most of the art he had ordered destroyed or covered up was untouched, and forty-six years later, when the Second Council of Nicaea met, the Church formally abandoned his policy. After all, Rome was also the old imperial stronghold of a romantic polytheism whose local deities, now renamed for saints, were cloaked in myth and legend. Since the fourth century, Christian art there had reflected that heritage. The form, construction, and columnar basilican style of the original St. Peter’s basilica, built between 330 and 360, were all in the pagan tradition. And nearby Santa Maria Maggiore, begun by Pope Sixtus III in 432, was actually the site of a former pagan temple.

WAS THE MEDIEVAL WORLD a civilization, comparable to Rome before it or to the modern era which followed? If by civilization one means a society which has reached a relatively high level of cultural and technological development, the answer is no. During the Roman millennium imperial authorities had controlled the destinies of all the lands within the empire—from the Atlantic in the west to the Caspian Sea in the east, from the Antonine Wall in northern Britain to the upper Nile valley in the south. Enlightened Romans had served as teachers, lawgivers, builders, and administrators; Romans had reached towering pinnacles of artistic and intellectual achievement; their city had become the physical and spiritual capital of the Roman Catholic Church.

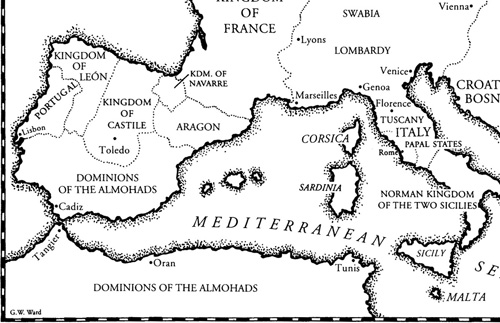

The age which succeeded it accomplished none of these. Trade on the Mediterranean, once a Roman lake, was perilous; Vandal pirates, and then Muslim pirates, lay athwart the vital sea routes. Agriculture and transport were inefficient; the population was never fed adequately. A barter economy yielded to coinage only because the dominant lords, enriched by plunder and conquest, needed some form of currency to pay for wars, ransoms, their departure on crusades, the knighting of their sons, and their daughters’ marriages. Royal treasury officials were so deficient in elementary skills that they were dependent upon arithmetic learned from the Arabs; the name exchequer emerged because they used a checkered cloth as a kind of abacus in doing sums. If their society was diverse and colorful, it was also anarchic, formless, and appallingly unjust.

Nevertheless it possessed its own structure and peculiar institutions, which evolved almost imperceptibly over the centuries. Medievalism was born in the decaying ruins of a senile and impotent empire; it died just a Europe was emerging as a distinctive cultural unit. The interregnum was the worst of times for the imaginative, the cerebral, and the unfortunate, but the strong, the healthy, the shrewd, the handsome, the beautiful—and the lucky—flourished.

Europe was ruled by a new aristocracy: the noble, and, ultimately, the regal. After the barbarian tribes had overwhelmed the Roman Empire, men had established themselves as members of the new privileged classes in various ways. Any leader with a large following of free men was eligible, though some had greater followings, and therefore greater claims, than others. In Italy some were members of Roman senatorial families, survivors who had intermarried with Goths or Huns; as Ovid had observed, a barbarian was suitable if he was rich. Others in the particiate were landowners whose huge domains (latifundia) were worked by slaves and protected by private armies of bucellaeii. In England and France the privileged might be descendants of Angle, Saxon, Frank, Vandal, or Ostrogoth chieftains. Many German hierarchs belonged to very old families, revered since time immemorial, and therefore acceptable to the other princes —the Reichsfürsten-stand—who had to approve each ennoblement. Because this was a time of incessant warfare, however, most noblemen had risen by distinguishing themselves in battle. In the early centuries distinction ended with the death of the man who had won it, but patrilineal descent became increasingly common, creating dynasties.

Titles evolved: duke, from the Latin dux, meaning a military commander; earl, from the Anglo-Saxon eorla or cheorl (as distinguished from churl); count or comte, from the Latin comes, a companion of a great personage; baron, from the Teutonic beron, a warrior; margrave, from the Dutch markgraaf; and marquess, marquis, markis, marques, marqués, or marchese, from the Latin marca—literally a frontier, or frontier territory. Serving these, on the lowest rung of the aristocratic ladder, was the knight (French chevalier, German Ritter, Italian cavallo, Spanish caballero, Portuguese cavalheiro). Originally the word meant a farm worker of free birth. By the eleventh century knights were cavalrymen living in fortified mansions, each with his noble seal. All were guided, in theory at least, by an idealistic knightly code and bound by oath to serve a duke, earl, count, baron, or marquis who, in turn, periodically honored him with gifts: horses, falcons, even weapons.

ROYALTY WAS invested with glory, swathed in mystique, and clothed with magical powers. To be a king was to be a lord of men, a host at great feasts for his vassal dukes, earls, counts, barons, and marquises; a giver of rings, of gold, of landed estates. Because the first medieval rulers had been barbarians, most of what followed derived from their customs. Chieftains like Ermanaric, Alaric, Attila, and Clovis rose as successful battlefield leaders whose fighting skills promised still more triumphs to come. Each had been chosen by his warriors, who, after raising him on their shields, had carried him to a pagan temple or a sacred stone and acclaimed him there. In the first century Tacitus had noted that the chiefs’ favored lieutenants were the gasindi or comitatus—future nobles—whose supreme virtue was absolute loyalty to the chief. Lesser tribesmen were grateful to him for the spoils of victory, though his claim on their allegiance also had supernatural roots.

His retinue always included pagan priests—sometimes he himself was one—and he was believed to be either favored by the gods or descended from them. When Christian missionaries converted a chieftain, his men obediently followed him to the baptismal font. Christian priests then enthroned his successors. A bishop’s investiture of a Frankish chief was recorded in the fifth century, and by 754, when Pope Stephen II consecrated the new king of the Franks—Pepin the Short, Charlemagne’s father — impressive ceremonies and symbols had been designed. The liturgy drew Old Testament precedents from Solomon and Saul; Pepin was crowned and solemnly armed with a royal scepter. The Holy Father exacted promises from him that he would defend the Church, the poor, the weak, and the defenseless; he then proclaimed him anointed of the Lord.

Hereditary monarchy, like hereditary nobility, was largely a medieval innovation. It is true that some barbarian lieutenants had held office by descent rather than deed. But the chieftains had been chosen for merit, and early kings wore crowns only ad vitam aut culpam—for life or until removed for fault. Because the papacy opposed primogeniture, secular leaders tried to maintain the fiction that sovereigns were elected—during the Capetian dynasty court etiquette required that all references to the king of France mention that he had been chosen by his subjects, when in fact son succeeded father in unbroken descent for 329 years—but by the end of the Middle Ages, this pretense had been abandoned. In England, France, and Spain the succession rights of royal princes had become absolute. After 1356 only Holy Roman emperors were elected (by seven carefully designated electors), and then only because the Vatican was in a position to insist on it, the office being within the Christian community, or ecclesia. Even so, beginning in 1437 the Habsburg family had a stranglehold on the imperial title.

The conspicuous sacerdotal role in the crowning of kings, who then claimed that they ruled by divine right, was characteristic of Christianity’s domination of medieval Europe. Proclamations from the Holy See—called bulls because of the bulla, a leaden seal which made them official—were recognized in royal courts. So were canon (ecclesiastical) law and the rulings of the Curia, the Church’s central bureaucracy in Rome. Strong sovereigns continued to seek freedom from the Vatican, with varying success; in the twelfth century, the quarrels between England’s Henry II and the archbishop of Canterbury ended with the archbishop’s murder, and the Holy Roman emperor Frederick Barbarossa (“Redbeard”), battling to establish German predominance in western Europe, was in open conflict with a series of popes.

However, the greatest wound to the prestige of the Vatican was self-inflicted. In 1305 Pope Clement V, alarmed by Italian disorders and a campaign to outlaw the Catholic Knights Templars, moved the papacy to Avignon, in what is now southeastern France. There it remained for seven pontificates, despite appeals from such figures as Petrarch and Saint Catherine of Siena. By 1377, when Pope Gregory XI returned the Holy See to Rome, the College of Cardinals was dominated by Frenchmen. After Gregory’s death the following year the sacred college was hopelessly split. A majority wanted a French pontiff; a minority, backed by the Roman mob, demanded an Italian. Intimidated, the college capitulated to the rabble and elected Bartolomeo Prignano of Naples. French dissidents fled home and chose one of their own, with the consequence that for nearly forty years Christendom was ruled by two Vicars of Christ, a pope in Rome and an antipope in Avignon.

IN ANOTHER AGE, so shocking a split would have created a crisis among the faithful, but there was no room in the medieval mind for doubt; the possibility of skepticism simply did not exist. Katholikos, Greek for “universal,” had been used by theologians since the second century to distinguish Christianity from other religions. In A.D. 340 Saint Cyril of Jerusalem had reasoned that what all men believe must be true, and ever since then the purity of the faith had derived from its wholeness, from the conviction, as expressed by an early Jesuit, that all who worshiped were united in “one sacramental system under the government of the Roman Pontiff.” Anyone not a member of the Church was to be cast out of this life, and more important, out of the next. It was consignment to the worst fate imaginable, like being exiled from an ancient German tribe—“to be given forth,” in the pagan Teutonic phrase, “to be a wolf in holy places.” The faithless were doomed; the Fifth Lateran Council (1512–1517) reaffirmed Saint Cyprian’s third-century dictum: “Nulla salus extra ecclesiam”—“Outside the Church there is no salvation.” Any other finding would have been inconceivable.

Catholicism had thus found its greatest strength in total resistance to change. Saint Jean Baptiste de la Salle, in his Les devoirs d’un Chrétien (Duties of a Christian, 1703), defined Catholicism as “the society of the faithful collected into one and the same body, governed by its legitimate pastors, of whom Jesus Christ is the invisible head—the pope, the successor of Saint Peter, being his representative on earth.” Saint Vincent of Lérins had written in his Commonitoria (Memoranda, c. 430) that the Church had become “a faithful and ever watchful guardian of the dogmas which have been committed to her charge. In this secret deposit she changes nothing, she takes nothing from it, she adds nothing to it.”

Subsequent spokesmen for the Holy See enlarged upon this, assuming, in God’s name, the right to prohibit changes by those who worshiped elsewhere or nowhere. Overstating this absolutism is impossible. “The Catholic Church holds it better,” wrote a Roman theologian, “that the entire population of the world should die of starvation in extremest agony … than that one soul, I will not say should be lost, but should commit one single venial sin.” In the words of one pope, “The Church is independent of any earthly power, not merely in regard to her lawful end and purpose, but also in regard to whatever means she may deem suitable and necessary to attain them.” Another pope, agreeing, declared that God had made the Vatican “a sharer in the divine magistracy, and granted her, by special privilege, immunity from error.” Even to “appeal from the living voice of the Church” was “a treason,” wrote a cardinal, “because that living voice is supreme; and to appeal from that supreme voice is also a heresy, because that voice, by divine assistance, is infallible.” A fellow cardinal put it even more clearly: “The Church is not susceptible of being reformed in her doctrines. The Church is the work of an Incarnate God. Like all God’s works, it is perfect. It is, therefore, incapable of reform.”

THE MOST BAFFLING, elusive, yet in many ways the most significant dimensions of the medieval mind were invisible and silent. One was the medieval man’s total lack of ego. Even those with creative powers had no sense of self. Each of the great soaring medieval cathedrals, our most treasured legacy from that age, required three or four centuries to complete. Canterbury was twenty-three generations in the making; Chartres, a former Druidic center, eighteen generations. Yet we know nothing of the architects or builders. They were glorifying God. To them their identity in this life was irrelevant. Noblemen had surnames, but fewer than one percent of the souls in Christendom were wellborn. Typically, the rest—nearly 60 million Europeans—were known as Hans, Jacques, Sal, Carlos, Will, or Will’s wife, Will’s son, or Will’s daughter. If that was inadequate or confusing, a nickname would do. Because most peasants lived and died without leaving their birthplace, there was seldom need for any tag beyond One-Eye, or Roussie (Redhead), or Bionda (Blondie), or the like.

Their villages were frequently innominate for the same reason. If war took a man even a short distance from a nameless hamlet, the chances of his returning to it were slight; he could not identify it, and finding his way back alone was virtually impossible. Each hamlet was inbred, isolated, unaware of the world beyond the most familiar local landmark: a creek, or mill, or tall tree scarred by lightning. There were no newspapers or magazines to inform the common people of great events; occasional pamphlets might reach them, but they were usually theological and, like the Bible, were always published in Latin, a language they no longer understood. Between 1378 and 1417, Popes Clement VII and Benedict XIII reigned in Avignon, excommunicating Rome’s Urban VI, Boniface IX, Innocent VII, and Gregory XII, who excommunicated them right back. Yet the toiling peasantry was unaware of the estrangement in the Church. Who would have told them? The village priest knew nothing himself; his archbishop had every reason to keep it quiet. The folk (Leute, popolo, pueblo, gens, gente) were baptized, shriven, attended mass, received the host at communion, married, and received the last rites never dreaming that they should be informed about great events, let alone have any voice in them. Their anonymity approached the absolute. So did their mute acceptance of it.

In later ages, when identities became necessary, their descendants would either adopt the surname of the local lord—a custom later followed by American slaves after their emancipation—or take the name of an honest occupation (Miller, Taylor, Smith). Even then they were casual in spelling it; in the 1580s the founder of Germany’s great munitions dynasty variously spelled his name as Krupp, Krupe, Kripp, Kripe, and Krapp. Among the implications of this lack of selfhood was an almost total indifference to privacy. In summertime peasants went about naked.

In the medieval mind there was also no awareness of time, which is even more difficult to grasp. Inhabitants of the twentieth century are instinctively aware of past, present, and future. At any given moment most can quickly identify where they are on this temporal scale—the year, usually the date or day of the week, and frequently, by glancing at their wrists, the time of day. Medieval men were rarely aware of which century they were living in. There was no reason they should have been. There are great differences between everyday life in 1791 and 1991, but there were very few between 791 and 991. Life then revolved around the passing of the seasons and such cyclical events as religious holidays, harvest time, and local fetes. In all Christendom there was no such thing as a watch, a clock, or, apart from a copy of the Easter tables in the nearest church or monastery, anything resembling a calendar. * Generations succeeded one another in a meaningless, timeless blur. In the whole of Europe, which was the world as they knew it, very little happened. Popes, emperors, and kings died and were succeeded by new popes, emperors, and kings; wars were fought, spoils divided; communities suffered, then recovered from, natural disasters. But the impact on the masses was negligible. This lockstep continued for a period of time roughly corresponding in length to the time between the Norman conquest of England, in 1066, and the end of the twentieth century. Inertia reinforced the immobility. Any innovation was inconceivable; to suggest the possibility of one would have invited suspicion, and because the accused were guilty until they had proved themselves innocent by surviving impossible ordeals—by fire, water, or combat—to be suspect was to be doomed.

EVEN DURING the Great Schism, as the interstice of the rival popes came to be known, the Holy See remained formidable. In 1215 the medieval papacy had reached its culmination at the Fourth Lateran Council, held in a Roman palace which, before Nero confiscated it, had been the home of the ancient Laterani family. The council, representing the entire Church, was brilliantly attended. Its decrees were of supreme importance, covering confession, Easter rites, clerical and lay reform, and the doctrine of transubstantiation, an affirmation that at holy communion bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Christ. The council glorified Vicars of Christ in language of unprecedented majesty and splendor; pontiffs were explicitly permitted to exert authority not only in theological matters, but also in all vital political issues which might arise. Later in the thirteenth century Saint Thomas Aquinas celebrated the accord of reason and revelation, and in 1302 Unam Sanctam—a bull affirming papal supremacy—was proclaimed. Even during its Avignon exile the Church progressed, centralizing its government and creating an elaborate administrative structure. Medieval institutions seemed stronger than ever.

And yet, and yet …

Rising gusts of wind, disregarded at the time, signaled the coming storm. The first gales affected the laity. Knighthood, a pivotal medieval institution, was dying. At a time when its ceremonies had finally reached their fullest development, chivalry was obsolescent and would soon be obsolete. The knightly way of life was no longer practical. Chain mail had been replaced by plate, which, though more effective, was also much heavier; horses which were capable of carrying that much weight were hard to come by, and their expense, added to that of the costly new mail, was almost prohibitive. Worse still, the mounted knight no longer dominated the battlefield; he could be outmaneuvered and unhorsed by English bowmen, Genoese crossbowmen, and pikemen led by lightly armed men-at-arms, or sergeants. Europe’s new armies were composed of highly trained, well-armed professional infantrymen who could remain in the field, ready for battle, through an entire season of campaigning. Since only great nation-states could afford them, the future would belong to powerful absolute monarchs.

By A.D. 1500 most of these sovereign dynasties were in place, represented by England’s Henry VII, France’s Louis XII, Russia’s Ivan III, Scandinavia’s John I, Hungary’s Ladislas II, Poland’s John Albert, and Portugal’s Manuel I. Another major player was on the way: in 1492, when the fall of Granada destroyed the last vestiges of Moorish power on the Iberian peninsula, Spaniards completed the long reconquest of their territory. The union of their two chief crowns with the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile laid the foundations for modern Spain; together they began suppressing their fractious vassals. Germany and Italy, however, were going to be late in joining the new Europe. On both sides of the Alps prolonged disputes over succession delayed the coalescence of central authority. As a result, in the immediate future Italians would continue to live in city-states or papal states and Germans would still be ruled by petty princes. But this fragmentation could not last. A kind of centripetal force, strengthened by emerging feelings of national identity among the masses, was reshaping Europe. And that was a threat to monolithic Christendom.

The papacy was vexed otherwise as the fifteenth century drew to a close. European cities were witnessing the emergence of educated classes inflamed by anticlericalism. Their feelings were understandable, if, in papal eyes, unpardonable. The Lateran reforms of 1215 had been inadequate; reliable reports of misconduct by priests, nuns, and prelates, much of it squalid, were rising. And the harmony achieved by theologians over the last century had been shattered. Bernard of Clairvaux, the anti-intellectual saint, would have found his worst suspicions confirmed by the new philosophy of nominalism. Denying the existence of universals, nominalists declared that the gulf between reason and revelation was unbridgeable—that to believe in virgin birth and the resurrection was completely unreasonable. Men of faith who might have challenged them, such as Thomas à Kempis, seemed lost in a dream of mysticism.

At the same time, a subtle but powerful new spirit was rising in Europe. It was virulently subversive of all medieval society, especially the Church, though no one recognized it as such, partly because its greatest figures were devout Catholics. During the pontificate of Innocent III (1198–1216) the rediscovery of Aristotelian learning—in dialectic, logic, natural science, and metaphysics—had been readily synthesized with traditional Church doctrine. Now, as the full cultural heritage of Greece and Rome began to reappear, the problems of synthesis were escalating, and they defied solution. In Italy the movement was known as the Rinascimento. The French combined the verb renaître, “revive,” with the feminine noun naissance, “birth,” to form Renaissance—rebirth.

FIXING A DATE for the beginning of the Renaissance is impossible, but most scholars believe its stirrings had begun by the early 1400s. Although Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Saint Francis of Assisi, and the painter Giotto de Bondone—all of whom seem to have been infused with the new spirit—were dead by then, they are seen as forerunners of the reawakening. In the long reach of history, the most influential Renaissance men were the writers, scholars, philosophers, educators, statesmen, and independent theologians. However, their impact upon events, tremendous as it was, would not be felt until later. The artists began to arrive first, led by the greatest galaxy of painters, sculptors, and architects ever known. They were spectacular, they were most memorably Italian, notably Florentine, and because their works were so dazzling—and so pious—they had the enthusiastic blessing and sponsorship of the papacy. Among their immortal figures were Botticelli, Fra Filippo Lippi, Piero della Francesca, the Bellinis, Giorgione, Della Robbia, Titian, Michelangelo, Raphael, and, elsewhere in Europe, Rubens, the Brueghels, Dürer, and Holbein. The supreme figure was Leonardo da Vinci, but Leonardo was more than an artist, and will appear later in this volume, trailing clouds of glory.

When we look back across five centuries, the implications of the Renaissance appear to be obvious. It seems astonishing that no one saw where it was leading, anticipating what lay round the next bend in the road and then over the horizon. But they lacked our perspective; they could not hold a mirror up to the future. Like all people at all times, they were confronted each day by the present, which always arrives in a promiscuous rush, with the significant, the trivial, the profound, and the fatuous all tangled together. The popes, emperors, cardinals, kings, prelates, and nobles of the time sorted through the snarl and, being typical men in power, chose to believe what they wanted to believe, accepting whatever justified their policies and convictions and ignoring the rest. Even the wisest of them were at a hopeless disadvantage, for their only guide in sorting it all out—the only guide anyone ever has—was the past, and precedents are worse than useless when facing something entirely new. They suffered another handicap. As medieval men, crippled by ten centuries of immobility, they viewed the world through distorted prisms peculiar to their age.

In all that time nothing of real consequence had either improved or declined. Except for the introduction of waterwheels in the 800s and windmills in the late 1100s, there had been no inventions of significance. No startling new ideas had appeared, no new territories outside Europe had been explored. Everything was as it had been for as long as the oldest European could remember. The center of the Ptolemaic universe was the known world—Europe, with the Holy Land and North Africa on its fringes. The sun moved round it every day. Heaven was above the immovable earth, somewhere in the overarching sky; hell seethed far beneath their feet. Kings ruled at the pleasure of the Almighty; all others did what they were told to do. Jesus, the son of God, had been crucified and resurrected, and his reappearance was imminent, or at any rate inevitable. Every human being adored him (the Jews and the Muslims being invisible). During the 1,436 years since the death of Saint Peter the Apostle, 211 popes had succeeded him, all chosen by God and all infallible. The Church was indivisible, the afterlife a certainty; all knowledge was already known. And nothing would ever change.

The mighty storm was swiftly approaching, but Europeans were not only unaware of it; they were convinced that such a phenomenon could not exist. Shackled in ignorance, disciplined by fear, and sheathed in superstition, they trudged into the sixteenth century in the clumsy, hunched, pigeon-toed gait of rickets victims, their vacant faces, pocked by smallpox, turned blindly toward the future they thought they knew—gullible, pitiful innocents who were about to be swept up in the most powerful, incomprehensible, irresistible vortex since Alaric had led his Visigoths and Huns across the Alps, fallen on Rome, and extinguished the lamps of learning a thousand years before.

WHEN THE CARTOGRAPHERS of the Middle Ages came to the end of the world as they knew it, they wrote: Beware: Dragons Lurk Beyond Here. They were right, though the menacing dimension was not on maps, but on the calendar. It was time, not space. There the fiercest threats to their medieval mind-set waited in ambush. A few of the perils had already infiltrated society, though their presence was unsuspected and the havoc they would wreak was yet to come. Some of the dragons were benign, even saintly; others were wicked. All, however, would seem monstrous to those who cherished the status quo, and their names included Johannes Gutenberg, Cesare Borgia, Johann Tetzel, Desiderius Erasmus, Martin Luther, Jakob Fugger, François Rabelais, Girolamo Savonarola, Nicolaus Copernicus, Giordano Bruno, Niccolò Machiavelli, William Tyndale, John Calvin, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Emperor Charles V, King Henry VIII, Tomás de Torquemada, Lucrezia Borgia, William Caxton, Gerardus Mercator, Girolamo Aleandro, Ulrich von Hutten, Martin Waldseemüller, Thomas More, Catherine of Aragon, Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and—most fearsome of all, the man who would destroy the very world the cartographers had drawn—Ferdinand Magellan.