Chapter 2

The World Transformed

I. The Way of Noble Love

A man a woman, a woman a man,

Tristan Isolt, Isolt Tristan.

“As the glow of love’s inward fire increases,” the poet Gottfried wrote, “so the frenzy of the lover’s suit. But this pain is so full of love, this anguish so enheartening, that no noble heart would dispense with it, once having been so heartened.”Note 1

Figure

13. Gottfried of Strassburg (ink on velum, Germany, c.

1304)

Of all the modes of experience by which the individual might be carried away from the safety of well-trodden grounds to the danger of the unknown, the mode of feeling, the erotic, was the first to waken Gothic man from his childhood slumber in authority; and, as Gottfried’s language tells, there were those, whom he calls noble, whose lives received from this spiritual fire the same nourishment as the lover of God received from the bread and wine of the sacrament. The poet intentionally echoes, in celebration of his legend, the monkish raptures of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux’s famous series of sermons on the Song of Songs:

“I know it,” he writes, “as surely as my death, since I have learned from the agony itself: the noble lover loves love stories. Anyone yearning for such a story, then, need fare no farther than here: for I shall story him well of noble lovers who of pure love gave proof enough: he in love, she in love.…”

We read their life, we read their death,

And to us it is sweet as bread.

Their life, their death, are our bread.

So lives their life, so lives their death,

So live they still and yet are dead

And their death is the bread of the living.Note 2

Like the other legends of Arthurian romance, that of Tristan and Isolt had been distilled from a compound of themes derived from pagan Celtic myth, transformed and retold as of Christian knighthood. Hence the force of its allure to the still half-pagan ears that opened to its song in the age of the Crusades, and its appeal to romantic hearts ever since. For, as in all great pagan mythologies, in the Celtic there is throughout an essential reliance on nature; whereas, according to every churchly doctrine, nature had been so corrupted by the Fall of Adam and Eve that there was no virtue in it whatsoever. The Celtic hero, as though moved by an infallible natural grace, follows without fear the urges of his heart. And though these may promise only sorrow and pain, danger and disaster — to Christians, even the ultimate disaster of hell for all eternity — when followed for themselves alone, without thought or care for consequence, they can be felt to communicate to a life, if not the radiance of eternal life, at least integrity and truth.

Saint Augustine had established in the early fifth century, against the Irish heretic Pelagius, the doctrine that salvation from the general corruption of the Fall can be attained only through a supernatural grace that is rendered not by nature but by God, through Jesus crucified, and dispensed only by the clergy of his incorruptible Church, through its seven sacraments. Extra ecclesiam nulla salus. And yet within the fold of the Gothic Church of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the corruption at least of the natural (if not also the supernatural) character of its incorruptible clergy was the outstanding scandal of the age.Note 3 Arthurian romance suggested to those with ears to hear that there was in corruptible nature a virtue, after all, without which life lacked incorruptible nobility; and it delivered this interesting message, which had been known for eons to the greater part of mankind, simply by clothing Celtic gods and heroes, heroines and goddesses, in the guise of Christian knights and damosels. Hence the challenge in these romances to the Church.

And to make his own recognition of this really serious challenge quite clear, the poet Gottfried described the love grotto in which his lovers took refuge from Isolt’s sacramented marriage to King Mark as a chapel in the heart of nature, with the bed of their consummation of love in the place proper to an altar.

The grotto had been hewn in heathen times into the wild mountain [Gottfried told], when giants ruled, before the coming of Corinaeus (Corinaeus was supposed to have been the eponymous hero of Cornwall. He was so designated in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain 1.12, whose source for the name was Virgil’s Aeneid 9.571 and 12.298.). And there it had been their wont to hide when they wished privacy to make love. Indeed, wherever such a grotto was found, it was closed with a door of bronze and inscribed to Love with this name: La fossiure a la gent amant, which is to say, “The Grotto for People in Love.”

The name well suited the place. For as its legend lets us know, the grotto was circular, wide, high, and with upright walls, snow-white, smooth and plain. Above, the vault was finely joined, and on the keystone there was a crown, embellished beautifully by the goldsmith’s art with an incrustation of gems. The pavement below was of a smooth, shining and rich marble, green as grass. In the center stood a bed, handsomely and cleanly hewn of crystal, high and wide, well raised from the ground, and engraved round about with letters which — according to the legend — proclaimed its dedication to the goddess Love. Aloft, in the ceiling of the grotto, three little windows had been cut, through which light fell here and there. And at the place of entrance and departure was a door of bronze.Note 4

Gottfried explains in detail the allegory of these forms.

The circular interior is Simplicity in Love; for Simplicity best beseems Love, which cannot abide any corners: in Love, Malice and Cunning are the corners. The great width is the Power of Love. It is boundless. Height signifies Aspiration, reaching toward the clouds: nothing is too much for it when it strives to rise to where Golden Virtues bind the vault together at the key.…

The wall of the grotto is white, smooth, and upright: the character of Integrity. Its luster, uniformly white, must never be colored over; nor should any sort of Suspicion be able to find there bump or dent. The marble floor is Constancy — in its greenness and its hardness, which color and surface are most fitting; for Constancy is ever as freshly green as grass and as level and clear as glass. The bed of crystalline noble Love, at the center, was rightly consecrated to her name, and right well had the craftsman who carved its crystal recognized her due: for Love indeed must be crystalline, transparent, and translucent. Within the cave, across the door of bronze, there ran two bars; and there was a latch, too, within, let ingeniously through the wall — exactly where Tristan had found it. A little lever controlled it, which ran in from the outside and moved it this way and that. Moreover, there was neither lock nor key; and I shall tell you why.

There was no lock because any device that might be attached to a door (I mean on the outside) to cause it either to open or to lock, would signify Treachery. Because, if anyone enters Love’s door when he has not been admitted from within, this cannot be accounted Love: it is either Deceit or Force. Love’s door is there — Love’s door of bronze — to prevent anyone from entering unless it be by Love: and it is of bronze so that no device, whether of violence or of strength, cunning or mastery, treachery or lies, should enable one to undo it. Furthermore, the two bars within, the two seals of Love, are turned toward each other from each side. One is of cedar, the other ivory. And now you must learn their meaning:

The cedar bar signifies the Understanding and Reasoning of Love; the ivory, its Modesty and Purity. And with these two seals, these two chaste bars, the dwelling of Love is guarded: Treachery and Violence are locked out.

The little secret lever that was let in to the latch from outside was a rod of tin, and the latch — as it should be — was of gold. The latch and the lever, this and that: neither could have been better chosen for qualities. For tin is Gentle Striving in relation to a secret hope, while gold is Success. Thus tin and gold are appropriate. Everybody can direct his own striving according to his will: narrowly, broadly, briefly or at length, liberally or strictly, that way or this, this way or that, with little effort — as with tin; and there is little harm in that. But if he then, with proper gentleness, can give thought to the nature of Love, his lever of tin, this humble thing, will carry him forward to golden success and on to dear adventure.

Now those little windows above, neatly, skillfully, hewn into the cave right through the rock, admitted the radiance of the sun. The first is Gentleness, the next Humility, the last Breeding; and through all three the sweet light smiled of that blessed radiance, Honor, which is of all lights the very best to illuminate our grotto of earthly adventure.

Then finally, it has meaning, as well, that the grotto should lie thus alone in a savage Waste. The interpretation must be that Love and her occasions are not to be found abroad in the streets, nor in any open field. She is hidden away in the wild. And the way to her resort is toilsome and austere. Mountains lie all about, with many difficult turns leading here and there. The trails run up and down; we are martyred with obstructing rocks. No matter how well we keep the path, if we miss one single step, we shall never know safe return. But whoever has the good fortune to penetrate that wilderness, for his labors will gain a beatific reward. For he shall find there his heart’s delight. The wilderness abounds in whatsoever the ear desires to hear, whatsoever would please the eye; so that no one could possibly wish to be anywhere else. — And this I well know; for I have been there.… The little sun-giving windows often have sent their rays into my heart. I have known that grotto since my eleventh year, yet never have I been to Cornwall.Note 5

What food sustains the lovers sequestered in that cave?

“Obsessed with curiosity and wonder,” the poet Gottfried answers, “enough people have puzzled themselves with the question of how that couple, Isolt and Tristan, fed themselves in the Waste Land. I shall now tell and set that curiosity at rest.

“They looked upon each other and nourished themselves with that. The fruit that their eyes bore was the sustenance of both. Nothing but love and their state of mind did they consume.… And what better food could they have had, either for spirit or for body? Man was there with Woman, Woman was there with Man. What more could they have wished? They had what they were meant to have and had reached the goal of desire.… Note 6

“Love’s service (minne) is without eyes, and love (liebe) without fear, when it is sincere.”Note 7

II. The Devil’s Door

“The twelfth and thirteenth centuries, studied in the pure light of political economy, are insane,” wrote Henry Adams in his deceptively playful, profoundly serious interpretation of the great high peak of communal creative life in the cathedral-building age, Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres:Note 8

Figure

14. Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral (granite, France, twelfth

century)

“According to statistics, in the single century between 1170 and 1270, the French built eighty cathedrals and nearly five hundred churches of the cathedral class, which would have cost, according to an estimate made in 1840, more than five thousand millions to replace. Five thousand million francs is a thousand million dollars (Adams was writing in 1904. Today’s equivalent would be something more like ten thousand million dollars.), and this covered only the great churches of a single century. The same scale of expenditure had been going on since the year 1000, and almost every parish in France had rebuilt its church in stone; to this day France is strewn with the ruins of this architecture, and yet the still preserved churches of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, among the churches that belong to the Romanesque and Transition period, are numbered by hundreds until they reach well into the thousands. The share of this capital which was — if one may use a commerical figure — invested in the Virgin cannot be fixed, any more than the total sum given to religious objects between 1000 and 1300; but in a spiritual and artistic sense, it was almost the whole, and expressed an intensity of conviction never again reached by any passion, whether of religion, of loyalty, of patriotism, or of wealth; perhaps never even paralleled by any single economic effort, except in war.”Note 9

But we have found — have we not? — that a number of other initial developments in the unfolding of great civilizations also were marked with signs of insanity: the prodigious labors on the pyramids, for instance,Note 10 and the courtly astronomical mime of the Royal Tombs of Ur.Note 11 Indeed, as there appeared, and as here we recognize again, civilization, seriously regarded, cannot be described in economic terms. In their peak periods civilizations are mythologically inspired, like youth. Early arts are not, like late, the merely secondary concerns of a people devoted first to economics, politics, comfort, and then, in their leisure time, to aesthetic enjoyment. On the contrary, economics, politics, and even war (crusade) are, in such periods, but functions of a motivating dream of which the arts too are an irrepressible expression. The formative force of a traditional civilization is a kind of compulsion neurosis shared by all members of the implicated domain, and the leading practical function of religious (i.e. mythological) education, therefore, is to infect the young with the madness of their elders — or, in sociological terms, to communicate to its individuals the “system of sentiments” on which the group depends for survival as a unit. Let me cite to this point, once again, the whole paragraph already quoted in Primitive Mythology from the distinguished British anthropologist of Trinity College, Cambridge, the late Professor A. R. Radcliffe-Brown:

A society depends for its existence on the presence in the minds of its members of a certain system of sentiments by which the conduct of the individual is regulated in conformity with the needs of the society. Every feature of the social system itself and every event or object that in any way affects the well-being or the cohesion of the society becomes an object of this system of sentiments. In human society the sentiments in question are not innate but are developed in the individual by the action of the society upon him [italics mine]. The ceremonial customs of a society are a means by which the sentiments in question are given collective expression on appropriate occasions. The ceremonial (i.e. collective) expression of any sentiment serves both to maintain it at the requisite degree of intensity in the mind of the individual and to transmit it from one generation to another. Without such expression the sentiments involved could not exist.Note 12

In the great creative period of the cathedrals and crusades the leading muse of the civilization, as Adams correctly saw, was the Virgin Mother Mary, whom Dante, one century later, was to eulogize in the celebrated prayer that marks the culmination of his spiritual adventure through Hell, Purgatory, and the spheres of Paradise, to the beatific vison of the Trinity in the midst of the celestial rose:

Virgin Mother, daughter of thine own Son, humble and exalted more than any creature, fixed term of the eternal counsel, thou art she who didst so ennoble human nature that its own Maker disdained not to become its creature. Within thy womb was rekindled the Love through whose warmth this flower [the Celestial Rose] has thus blossomed in the eternal peace. Here [in Paradise] thou art to us the noonday torch of charity, and below, among mortals, thou art the living torch of hope. Lady, thou art so great, and so availest, that whoso would have grace, and has not recourse to thee, would have his desire fly without wings. Thy benignity not only succors him who asks, but often times freely foreruns the asking. In thee mercy, in thee pity, in thee magnificence, in thee whatever goodness there is in any creature, are united.… Note 13

As Oswald Spengler has properly noticed, however, the world of purity, light and utter beauty of soul of the Virgin Mother Mary — whose coronation in the heavens was one of the earliest motives of Gothic art, and who is simultaneously both a light-figure, in white, blue, and gold, surrounded by heavenly hosts, and an earthly mother bending over her newborn babe, standing at the foot of his Cross, and holding the corpse of her tortured, murdered son in resignation on her knees — would have been unimaginable without the counter-idea, inseparable from it, of Hell, “an idea,” Spengler writes,

that constitutes one of the maxima of the Gothic, one of its unfathomable creations — one that the present day forgets and deliberately forgets. While she there sits enthroned, smiling in her beauty and tenderness, there lies in the background another world that throughout nature and throughout mankind weaves and breeds ill, pierces, destroys, and seduces — the realm, namely, of the Devil.…

It is not possible to exaggerate either the grandeur of this forceful, insistent picture or the depth of sincerity with which it was believed in. The Mary-myths and the Devil-myth formed themselves side by side, neither possible without the other. Disbelief in either of them was deadly sin. There was a Mary-cult of prayer, and a Devil-cult of spells and exorcisms. Man walked continuously on the thin crust of a bottomless pit.…

For the Devil gained possession of human souls and seduced them into heresy, lechery, and black arts. It was war that was waged against him on earth, and waged with fire and sword upon those who had given themselves up to him. It is easy enough for us today to think ourselves out of such notions, but if we eliminate this appalling reality from the Gothic, all that remains is mere romanticism. It was not only the love-glowing hymns to Mary, but the cries of countless pyres as well that rose up to heaven. Hard by the Cathedral were the gallows and the wheel. Every man lived in those days in the consciousness of an immense danger, and it was hell, not the hangman, that he feared. Unnumbered thousands of witches genuinely imagined themselves to be so; they denounced themselves, prayed for absolution, and in pure love of truth confessed their night rides and bargains with the Evil One. Inquisitors, in tears and compassion for the fallen wretches, doomed them to the rack in order to save their souls. That is the Gothic myth, out of which came the cathedral, the crusader, the deep and spiritual painting, the mysticism. In its shadow flowered that profound Gothic blissfulness of which today we cannot even form an idea.Note 14

Nor did the Devil and his army of night-spirits, werewolves, and witches disappear from the European scene with the waning of the Middle Ages; with the Puritans he was transported to Plymouth Rock and New England and with Cortez went to Mexico to link arms with the powers of the Aztec underworld, Mictlan; for there too the cosmic nightmare was known: there were nine hells and thirteen heavens; however, until the Christian religion arrived, the idea of an eternal hell had never been conceived. In the ninth or final Aztec hell, which the voyaging soul would reach after a tortured journey of four years, it either found eternal rest or forever disappeared.

James Joyce, in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, has provided an unforgettable reproduction of the standard Jesuit hell sermon, delivered to Catholic schoolboys to this day by retreat masters, to furnish their dreams with nightmare stuff and keep their feet on the straight and narrow path. The scene is the chapel of an Irish Catholic school. The priest is lecturing his young charges quietly and gently, with genuine solicitude:

“Now let us try for a moment to realise, as far ar we can, the nature of that abode of the damned which the justice of an offended God has called into existence for the eternal punishment of sinners. Hell is a strait and dark and foulsmelling prison, an abode of demons and lost souls, filled with fire and smoke. The straitness of this prison house is expressly designed by God to punish those who refused to be bound by His laws. In earthly prisons the poor captive has at least some liberty of movement, were it only within the four walls of his cell or in the gloomy yard of his prison. Not so in hell. There, by reason of the great number of the damned, the prisoners are heaped together in their awful prison, the walls of which are said to be four thousand miles thick: and the damned are so utterly bound and helpless that, as a blessed saint, saint Anselm, writes in his book on similitudes, they are not even able to remove from the eye a worm that gnaws it.

“They lie in exterior darkness. For, remember, the fire of hell gives forth no light. As, at the command of God, the fire of the Babylonian furnace lost its heat but not its light, so, at the command of God, the fire of hell, while retaining the intensity of its heat, bums eternally in darkness. It is a neverending storm of darkness, dark flames and dark smoke of burning brimstone, amid which the bodies are heaped one upon another without even a glimpse of air. Of all the plagues with which the land of the Pharaohs was smitten one plague alone, that of darkness, was called horrible. What name, then, shall we give to the darkness of hell which is to last not for three days alone but for all eternity?

“The horror of this strait and dark prison is increased by its awful stench. All the filth of the world, all the offal and scum of the world, we are told, shall run there as to a vast reeking sewer when the terrible conflagration of the last day has purged the world. The brimstone, too, which burns there in such prodigious quantity fills all hell with its intolerable stench; and the bodies of the damned themselves exhale such a pestilential odor that, as saint Bonaventure says, one of them alone would suffice to infect the whole world. The very air of this world, that pure element, becomes foul and unbearable when it has been long enclosed. Consider then what must be the foulness of the air of hell. Imagine some foul and putrid corpse that has lain rotting and decomposing in the grave, a jelly-like mass of liquid corruption. Imagine such a corpse a prey to flames, devoured by the fire of burning brimstone and giving off dense choking fumes of nauseous loathsome decomposition. And then imagine this sickening stench, multiplied a millionfold and a millionfold again from the millions of fetid carcasses massed together in the reeking darkness, a huge and rotting human fungus. Imagine all this, and you will have some idea of the horror of the stench of hell.

“But this stench is not, horrible though it is, the greatest physical torment to which the damned are subjected. The torment of fire is the greatest torment to which the tyrant has ever subjected his fellowcreatures. Place your finger for a moment in the flame of a candle and you will feel the pain of fire. But our earthly fire was created by God for the benefit of man, to maintain in him the spark of life and to help him in the useful arts, whereas the fire of hell is of another quality and was created by God to torture and punish the unrepentant sinner. Our earthly fire also consumes more or less rapidly according as the object which it attacks is more or less combustible, so that human ingenuity has even succeeded in inventing chemical preparations to check or frustrate its action. But the sulphurous brimstone which burns in hell is a substance which is especially designed to burn for ever and for ever with unspeakable fury. Moreover, our earthly fire destroys at the same time as it burns, so that the more intense it is the shorter is its duration; but the fire of hell has this property, that it preserves that which it burns, and, though it rages with incredible intensity, it rages for ever.…”Note 15

And so on, for a terrible half-hour.

“Every sense of the flesh is tortured and every faculty of the soul therewith.… Consider finally that the torment of this infernal prison is increased by the company of the damned themselves.… The damned howl and scream at one another, their torture and rage intensified by the presence of beings tortured and raging like themselves. All sense of humanity is forgotten.… Last of all consider the frightful torment to those damned souls, tempters and tempted alike, of the company of the devils. These devils will afflict the damned in two ways, by their presence and by their reproaches. We can have no idea of how horrible these devils are. Saint Catherine of Siena once saw a devil and she has written that, rather than look again for one single instant on such a frightful monster, she would prefer to walk until the end of her life along a track of red coals.…”

The young hero of Joyce’s novel heard with a knowledge of precocious sins of his own, already committed, and when the priest dismissed the sickened little flock with the wish — “O, my dear little brothers in Christ!” — that they might never hear in God’s voice the awful sentence of rejection: Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels!, the boy rose from his pew and came down the aisle of the chapel, “his legs shaking and the scalp of his head trembling as though it had been touched by ghostly fingers.… And at every step he feared that he had already died.… He was judged.… His brain began to glow.” In the classrooom, he leaned back weakly at his desk. “He had not died. God had spared him still.… There was still time.… O Mary, refuge of sinners, intercede for him! O Virgin Undefiled, save him from the gulf of death!”Note 16

It is against the backdrop of such a nightmare as this, taken infinitely more seriously than the earth itself and the life to be lived on this earth (since the earth and life would pass, but this scene of hell’s bedlam, never), that the loves of Isolt and Guinevere, and of the actual women of the age of the great cathedrals, must be understood. Marriage in the Middle Ages was an affair largely of convenience. Moreover, girls betrothed in childhood for social, economic, or political ends, were married very young, and often to much older men, who invariably took their property rights in the women they had married very seriously. They might be away for years on Crusade; the wife was to remain inviolate, and if for any reason the worm Suspicion happened to have entered to gnaw the husband’s brain, his blacksmith might be summoned up to fit an iron girdle of chastity to the mortified young wife’s pelvic basin. The Church sanctified these sordid property rights, furthermore, with all the weight of Hell, Heaven, eternity, and the coming of Christ in glory on the day of judgment — the day so beautifully pictured in the western rose window of Chartres: that “jeweled sunburst on the Virgin’s breast,” as Henry Adams called it, “with three large pendants beneath.” So that, against all this, the wakening of a woman’s heart to love was in the Middle Ages a grave and really terrible disaster, not only for herself, for whom torture and fire were in prospect, but also for her lover; and not only here on earth but also — and more horribly — in the world to come, forever. Hence, in a phrase coined by the early Church Father Tertullian, which long remained a favorite of the pulpits, woman — earthly, actual woman, that is — awakened to her nature, was janua diaboli, “the devil’s door.”

III. Heloise

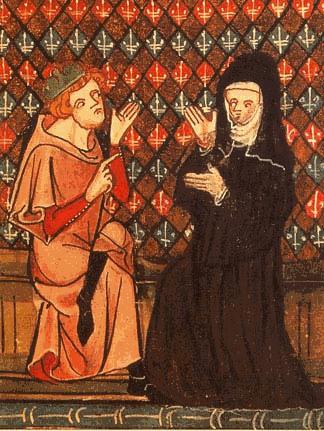

Figure

15. Abelard & Heloise (ink on vellum, c. 1370)

Abelard was thirty-eight, Heloise eighteen, and the year 1118 a.d. “There was in Paris a young girl named Heloise, the niece of a canon, Fulbert,” we read in the rueful autobiographical letter known as Abelard’s Historia calamitatum.

I had hitherto lived continently, but now was casting my eyes about, and I saw that she possessed every attraction that lovers seek; nor did I regard my success as doubtful, when I considered my fame and my goodly person, and also her love of letters. Inflamed with love, I thought how I could best become intimate with her. It occurred to me to obtain lodgings with her uncle, on the plea that household cares distracted me from study. Friends quickly brought this about, the old man being miserly and yet desirous of instruction for his niece. He eagerly entrusted her to my tutorship, and begged me to give her all the time I could take from my lectures, authorizing me to see her at any hour of the day or night and punish her when necessary. I marveled with what simplicity he confided a tender lamb to a hungry wolf.… Well, what need to say more: we were united first by the one roof above us, and then by our hearts.

Now it may or may not be relevant that Abelard, like Tristan of the legend, was bom in Celtic Brittany, where, in those years, that oft-told tale of illicit love was in the making which (in Gottfried’s phrase) was “bread to all noble hearts.” Abelard, like Tristan, was a harpist of renown: his songs composed to Heloise were sung throughout the young Latin Quarter. And, like Tristan, he was given the task of tutoring the young lady, who, like the maid Isolt, was comparable (in the words, again, of Gottfried) “only to the Sirens with their lodestone, who draw to themselves stray ships.”

To the agitation of many a heart [wrote Gottfried of the maid Isolt] she sang at once openly and secretly, by the ways of both ear and eye. The melody sung openly, both abroad and with her tutor, was of her own sweet voice and the strings’ soft sound that openly and clearly rode through the kingdom of the ears, down deep, into the heart. But the secret song was her marvelous beauty itself, which covertly and silently slipped through the windows of the eyes, and in many noble hearts spread a magic that immediately made thoughts captive and fettered them with yearning and yearning’s stress.Note 17

Love was in the air in that century of the troubadours, shaping lives no less than tales; but the lives, specifically and only, of those of noble heart, whose courage in their knowledge of love announced the great theme that was in time to become the characteristic signal of our culture: the courage, namely, to affirm against tradition whatever knowledge stands confirmed in one’s own controlled experience. For the first of such creative knowledges in the destiny of the West was of the majesty of love, against the supernatural utilitarianism of the sacramental system of the Church. And the second was of reason. So it can be truly said that the first published manifesto of this new age of the world, the age of the self-reliant individual, appeared at the first dawn of the most creative century of the Gothic Middle Ages, in the love and the noble love letters of the lady Heloise to Abelard. For when she discovered herself pregnant, her lover, in fear, spirited her off to his sister’s place in Brittany; and when she had there given birth to their son — whom they christened Astralabius — Abelard, as the calamitous letter tells, proposed to her that they should marry.

However, as we read, returning to Abelard’s words:

She strongly disapproved and urged two reasons against the marriage, to wit, the danger and the disgrace in which it would involve me.

She swore — and so it proved — that no satisfaction would ever appease her uncle. She asked how she was to have any glory through me when she should have made me inglorious, and should have humiliated both herself and me. What penalties would the world exact from her if she deprived it of such a luminary; what curses, what damage to the Church, what lamentations of philosophers, would follow on this marriage! How indecent, how lamentable would it be for a man whom nature had made for all, to declare that he belonged to one woman, and subject himself to such shame!”

The letter, continuing, next recounts some of the arguments urged by Heloise in dissuasion.

From her soul [wrote Abelard to his reader], she detested this marriage, which would be so utterly ignominious for me, and a burden to me. She expatiated on the disgrace and inconvenience of matrimony for me and quoted the Apostle Paul exhorting men to shun it. If I would not take the apostle’s advice or listen to what the saints had said regarding the matrimonial yoke, I should at least pay attention to the philosophers — to Theophrastus’s words upon the intolerable evils of marriage, and to the refusal of Cicero to take a wife after he had divorced Terentia, when he said that he could not devote himself to a wife and philosophy at the same time. “Or,” she continued, “laying aside the disaccord between study and a wife, consider what a married man’s establishment would be to you. What sweet accord there would be between the schools and domestics, between copyists and cradles, between books and distaffs, between pen and spindle! Who, engaged in religious or philosophical meditations, could endure a baby’s crying and the nurse’s ditties stilling it, and all the noise of servants? Could you put up with the dirty ways of children? The rich can, you say, with their palaces and apartments of all kinds; their wealth does not feel the expense or the daily care and annoyance. But I say, the state of the rich is not that of philosophers; nor have men entangled in riches and affairs any time for the study of Scripture or philosophy. The renowned philosophers of old, despising the world, fleeing rather than relinquishing it, forbade themselves all pleasures, and reposed in the embraces of philosophy.… If laymen and Gentiles, bound by no profession of religion, lived thus, surely you, a clerk and canon, should not prefer low pleasures to sacred duties, nor let yourself be sucked down by this Charybdis and smothered in filth inextricably. If you do not value the privilege of a clerk, at least defend the dignity of a philosopher. If reverence for God be despised, still let love of decency temper immodesty.…

Finally [Abelard continued to his friend] she said that it would be dangerous for me to take her back to Paris; it was more becoming to me, and sweeter to her, to be called my mistress, so that affection alone might keep me hers and not the binding power of any matrimonial chain; and if we should be separated for a time, our joys at meeting would be the dearer for their rarity. When at last with all her persuasions and dissuasions she could not turn me from my folly, and could not bear to offend me, with a burst of tears she ended in these words: “One thing is left: in the ruin of us both the grief which follows shall not be less than the love which went before.”

“Nor did she here lack the spirit of prophecy,” the poor man added in comment; for the world knows what then occurred. Leaving their son in Brittany in the care of Abelard’s sister, the couple returned to Paris and were married in the presence of the canon Fulbert, her uncle, who, however, still resenting the seduction, deflowering, and marriage of his niece, retaliated like a savage.

“Having bribed my servant,” Abelard wrote, “they came upon me by night, when I was sleeping, and took on me a vengeance as cruel and irretrievable as it was vile and shameful.” The canon Fulbert and his footpads had turned Abelard into a eunuch — who, however, in the spirit of a true and penitent Christian, finally was able to reflect in his confessional letter, years later: “I thought of my ruined hopes and glory, and then saw that by God’s just judgment I was punished where I had most sinned, and that Fulbert had justly avenged treachery with treachery.”

That is the first part of this cruel story. The second carries us further; for Abelard, in his shame, entered the monastery of Saint Denis as a monk, and Heloise, in obedience to his wish, the convent of Argenteuil as a nun. Ten years of silence followed, whereafter, from the convent to the monastery came a letter with the following superscription:

To her master, rather to a father, to her husband, rather to a brother, his maid or rather daughter, his wife or rather sister, to Abelard, Heloise.…

And therein the following, among much more of the kind, was to be read:

Thou knowest, dearest — and who knows not? — how much I lost in thee, and that an infamous act of treachery robbed me of thee and of myself at once.… Love turned to madness and cut itself off from hope of that which alone it sought, when I obediently changed my garb and my heart too in order that 1 might prove thee sole owner of my body as well as of my spirit. God knows, I have ever sought in thee only thyself, desiring simply thee and not what was thine. I asked no matrimonial contract, I looked for no dowry; not my pleasure, not my will, but thine have I striven to fulfill. And if the name of wife seemed holier or more potent, the word mistress [arnica] was always sweeter to me, or even — be not angry! — concubine or harlot; for the more I lowered myself before thee, the more I hoped to gain thy favor, and the less I should hurt the glory of thy renown.

I call God to witness that if Augustus, the master of the world, would honor me with marriage and invest me with equal rule, it would still seem to me dearer and more honorable to be called thy strumpet than his empress. He who is rich and powerful is not the better man: that is a matter of fortune, this of merit. And she is venal who marries a rich man sooner than a poor man, and yearns for a husband’s riches rather than himself.

Such a woman deserves pay and not affection. She is not seeking the man but his goods, and would wish, if possible, to prostitute herself to one still richer.

Thus the female of the species spoke, and one is reminded strongly of those noble words of an Abyssinian woman that were quoted in Primitive Mythology: “How can a man know what a woman’s life is …”;Note 18 so that once again, as so often in these pages, the same age-long dialogue of the sexes is heard that was represented first in the alternating early symbols of the female- and the male-oriented mythological orders: first the little stone paleolithic Venus figurines of the earliest Aurignacian rock shelters, which presently had to give way to the magically costumed dancing males of the painted temple caves; next the numerous ceramic female figurines that have been found wherever Neolithic man tilled the soil, and then the sudden appearance of those thunder-hurling male divinities of the great patriarchal Semitic and Aryan warrior races. In the old Irish legends of the brazen Queen Meave, disregarding scornfully the patriarchal claims on her of her kingly warrior spouse, we have an early Celtic version of the challenge from the “other side,” delivered with a strong barbaric force;Note 19 and now, elevated in Heloise to a plane of civilization already centuries in advance of the crudely patriarchal, ecclesiastically sacramentalized moral order of her day, the challenge is again flung forth, and with equal, though more cautiously and much more graciously verbalized, scorn. From the opposite side, the nun, now the abbess of her convent, reviews the young love scenes of the tender lamb and middle-aged, ravenous wolf: “What queen did not envy me my joys and couch?” she wrote to her shattered lover of yore.

There were in you two qualities by which you could draw the soul of any woman, the gift of poetry and the gift of singing, gifts which other philosophers had lacked. As a distraction from labor, you composed love-songs both in meter and in rhyme, which for their sweet sentiment and music have been sung and resung and have kept your name in every mouth. Your sweet melodies do not permit even the illiterate to forget you. Because of these gifts women sighed for your love. And, as these songs sang of our loves, they quickly spread my name in many lands, and made me the envy of my sex. What excellence of mind or body did not adorn your youth?”

That had been the lover then; whereas now, as she reminds him, during the ten years of their separation she has not received from that lover a single written line.

“Tell me,” she wrote, “one thing,” and here she drove her dart:

Why, after our conversion, commanded by thyself, did I drop into oblivion, to be no more refreshed by speech of thine or letter? Tell me, I say, if you can, or I will say what I feel and what everyone suspects: desire rather than friendship drew you to me, lust rather than love. So when desire ceased, whatever you were manifesting for its sake likewise vanished. This, beloved, is not so much my opinion as the opinion of all. Would it were only mine and that thy love might find defenders to argue away my pain. Would that I could invent some reason to excuse you and also cover my cheapness. Listen, I beg, to what I ask, and it will seem small and very easy to you. Since I am cheated of your presence, at least put vows in words, of which you have a store, and so keep before me the sweetness of thine image.… When little more than a girl I took the hard vows of a nun, not from piety but at your command. If I merit nothing from thee, how vain I deem my labor! I can expect no reward from God, as I have done nothing from love of Him.… God knows, at your command I would have followed or preceded you to fiery places. For my heart is not with me, but with thee.Note 20

As Professor Henry Osborn Taylor, from whose translation I have taken my text, observes: “Remarks upon this letter would seem to profane a shrine. Had the man profaned that shrine?”Note 21

Obviously, the man had; and the same man, now a eunuch monk, was about to do so again. For the shrine of the abbess Heloise was to a deity unrecognized by the offices of Abelard’s theology: an actual experience, namely, of love, not for an abstraction but for a person; a flame of love in which lust and religion are equally consumed, so that, in fact, Abelard was her god. In her own words — and they may yet be crowned in Heaven as the noblest signature of her century — not the natural, animal urgencies of lust, not the supernatural, angelic desire to glow forever in the beatific vision, but the womanly, purely human experience of love for a specific living being, and the courage to burn for that love were to be the kingdom and the glory of a properly human life. Abelard, however, had never even known of that kingdom. For all his song-building and philosophy, the urge in his seduction of the girl had indeed been lust, and the urge behind his command of her to the nunnery had been fear — both of which emotions she had transcended through her love; which gives point to the famous line of the Persian poet of love, Hafiz (1325–1389): “Love’s slave am I, and from both worlds free.”

And so what, now, was to be Abelard’s reply? A letter addressed as follows: “To Heloise, his beloved sister in Christ, Abelard, her brother in the Same.” And, after a number of edifying paragraphs:

I have composed this prayer, which I send thee:

“O God, who formed woman from the side of man and didst sanction the sacrament of marriage; who didst bestow upon my frailty a cure for its incontinence; do not despise the prayers of thy handmaid, and the prayers which I pour out for my sins and those of my dear one. Pardon our great crimes, and may the enormity of our faults find the greatness of thy ineffable mercy. Punish the culprits in the present; spare, in the future. Thou hast joined us, Lord, and hast divided us, as it pleased thee. Now complete most mercifully what thou hast begun in mercy; and those whom thou hast divided in this world, join eternally in heaven, thou who art our hope, our portion, our expectation, our consolation, Lord blessed forever. Amen.Note 22

Farewell in Christ, spouse of Christ; in Christ farewell and in Christ live. Amen.Note 23

These two tortured communications, from convent to monastery and from monastery to convent, reveal the cleavage that in that period of the apogee of the Gothic separated the truths of human experience from the articles of enforced faith. The raging heresies of the time and the fury of their suppression likewise testify to an incongruity of Credo and Libido. However, these heresies, for the most part, whether of Manichaean or of Waldensian Christian type 23 — as well as the coarsely obscene, pathological Black Mass, which also flourished in these centuries — were as committed as the Roman Church itself to that dualistic dogma, imported from the Levant, according to which life in its spontaneity is not innocent but corrupt. Moreover, even following the inevitable explosion of the Reformation and the breakaway thereafter of the Lutherans, Calvinists, Anabaptists, and all, the entire Protestant movement carried this same dualism onward; so that the rafters of their chapels rang, splintered, cracked, and warped to the fiery preachments of the Fall of Man, atonement, and the reek of Hell.

In contrast, the testament of Heloise was of an actual experience of innocence in love, which erased from her heart the whole appeal of the other myth. One is reminded of the words of the greatest female mystic of Islam, Rabi’a of Basra (d. 801 a.d.), who proclaimed in her poems that her love for God was so great that she was filled with it to the brim, as a cup with wine, so that no place remained in her for either fear of Hell or desire for Paradise, nor for either love or hate of any other being — not the Prophet himself.Note 24

Now such a commitment to the beloved as that expressed in the declarations of these two women corresponds perfectly to the ideal of religious fervor that was cultivated in India in those centuries in the popular bhakti movement. Religious devotion was there defined as of two orders: 1. liturgical, formal (vaidhī bhakti); and 2. impassioned, guided by feeling (rāgānuga bhakti). The first, being the usual churchgoing sort of thing, was only by courtesy called devotion; whereas the latter, on the contrary, could not be acquired either by practice or by desire. As though struck by lightning, so is one by love, which is a divine seizure, transmuting the life, erasing every interfering thought. As we read in a Bengali text celebrating this experience: “The self is void, the world is void; heaven, earth, and the space between are void: in this rapture, there is neither virtue nor sin.”Note 25

The popular Indian Puranic legends of Kṛṣṇa and the Gopis, and the passionate Gīta Govinda of the young love poet Jayadeva (fl. 1170 a.d.)Note 26 represent the spirit of this tradition of divine rapture. And in the Moslem world as well, the related mystic movement of the Sufis — celebrating fanā, the “passing away of the self,” and bagā, the “unitive life in God” — likewise became the inspiration not only of religiously ecstatic (dervish) orders but also of a mystically toned secular poetry of love,Note 27 one of the leading centers of which was Moorish Spain.

But here we are on the road back to Abelard and Heloise, Tristan and Isolt; for with the reconquest of Toledo, in the year 1085, by Alfonso the Brave — the Christian King, Alfonso VI of Castile and Leon — the gates of Oriental poetry and song, mysticism and learning were opened wide to Europe. It is possible that even earlier than this date a flow of ideas may already have been set in motion from Moorish Spain to the north, and in particular by sea to Celtic Ireland, Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany (the lands of the romance of Tristan and Isolt), where a golden age of amalgamated pagan and Christian poetry and learning had glowed with a wild strange light of its own throughout the long grim night of the early Christian Middle Ages.Note 28 However, the real event was the reconquest of Toledo. And among the first of its great effects were the simultaneous births of the arts of love and love poetry in the lives and works of the troubadours.

The name troubadour itself (Provençal, trobador) has been traced with reasonable assurance from the Arabic root TRB (Ta Ra B = “music, song”), plus -ador, the usual Spanish agential suffix (as, for instance, in conquist-ador); so that Ta Ra B-ador would have meant originally simply “song- or music-maker.”Note 29 Professor Philip K. Hitti, who supports this etymology, states in his History of the Arabs that “the troubadours resembled Arab singers, not only in sentiment and character, but also in the very forms of their minstrelsy. Certain titles,” he avers, “which these Provencal singers gave to their songs are but translations from Arabic titles.”Note 30 And Professor H. A. R. Gibb has likewise remarked the connection of the two traditions, even pointing out that the poems of the first European troubadour, Count William IX of Poitiers, Duke of Aquitaine (1071–1127), were composed in meters sometimes identical with those of his Andalusian Arabic contemporary Ibn Quzman.Note 31 Moreover, Professor Hitti has further observed that, simultaneously with the rise, at the opening of the twelfth century, of this elite tradition of Arabicized European poetry, the “cult of the dame,” likewise “following the Arab precedent,” also suddenly appears.Note 32 Thus we now have evidence of an unbroken, though variously modified, aristocratic tradition of mystically toned erotic lore, extending from India not only eastward (as noted in Oriental Mythology) as far as to Lady Murasaki’s sentimental Fujiwara court in Kyoto,Note 33 but also westward into Europe, and even rising to almost simultaneous culmination all the way from Ireland to the Yellow Sea, at exactly the time of the calamitous adventure of Abelard and Heloise; so that the songs that he sang to the world in her name, and which would have drawn, as she declared, the soul of any woman, almost certainly were a northern echo from the gardens of Granada, Tripoli, Baghdad, and Kashmir.

However, whereas in the Orient the ultimate reference of the poetry of love was normally to that unitive rapture epitomized in the cry of the Persian Sufi mystic Bayazid of Bistan (d. 874 a.d.): “I am the Wine-drinker, the Wine, and the Cupbearer!” “Lover, beloved, and love are one!”Note 34 the European ideal was rather to celebrate specifically the beloved human individual, who, moreover, was normally a woman of high station and developed personality, not, as so often in the Orient, a mere slave girl, professional courtesan, or (in the Indian erotic rituals) a female of inferior caste.Note 35 In Dante’s case, it is true, no personal relationship beyond the meeting of the eyes was ever established here on earth between the poet and his beloved. However, it was Beatrice and she alone — Beatrice Portinari, in her own spiritual character, not as an exemplar merely of the general female power (śakti) but as that uniquely beautiful Florentine lady she had been when their eyes met — whose recollection brought home to him, in the decade following her death, the realization of the radiance and beatitude of that “divine Love,” as he writes, “which moves the sun and the other stars.”Note 36 Nor was she left behind, dissolved, forgotten, in the rapture of that beatific radiance, but herself was there, at the very feet of God, when the consummation was attained. And the work itself then was composed — the poet tells — in celebration specifically of her.

From the Oriental point of view, such a radical shift of accent from the abstract spiritual rapture to its natural earthly term has been generally judged to be a debasement; as it is, for example, in a recent work, The Sufis, by the Grand Sheikh Idries Shah, where it is alleged that, on entering the West, “the Sufi stream was partially dammed.… Certain elements, necessary to the whole and impossible without a human exemplar of the Sufi Way, remained almost unknown.”Note 37 But, on the other hand, in Europe an Oriental liquidation of oneself in a rapturous realization of the Alone with the Alone has been seldom either desired or intended — or even greatly admired — outside, that is to say, of certain cloisters. For the maintenance even in rapture of a hither-world state of consciousness — and a grateful appreciation thereby of the values of the personality — has been through most of our centuries the preferred Occidental state of mind. In the words of Nietzsche, “A new pride, my Ego taught me, and I teach it now to men: no longer to stick one’s head in the sand of celestial things, but to carry it freely, an earthly head that gives meaning to the earth!”Note 38

Something similar may seem to be intended in some of the advanced mystical writings of Japan; the lines, for instance, of the eighteenth-century Zen master Hakuin (1685–1768):

Not knowing how near the Truth is,

People seek it far away: what a pity!

This very earth is the Lotus Land of Purity,

And this body is the body of the Buddha.Note 39

However, even there, in the youngest, livest nation of the great East, the ideal — even in the Zen monasteries — is to follow rules of discipline handed down from the masters of the past for the realization of specified spiritual ends, whereas in the Europe of the new mythology of self-discovery and -reliance that was coming into being in the century of Heloise (outside the Church, outside the monastery), neither rules nor aims were foreknown. The mind entered the wood, so to say, “where it was thickest,” in true adventure, and the unforeseen, unprecedented experience itself then became the opener and dictator of a singular way.

Abelard had been for Heloise such a determinant, and she, in turn, might have become the like for him, had he possessed the courage to let her remain unincorporated through marriage in the context of his already held system of ideas. But instead — alas for them both! — he clung to his past, his sacraments, Heaven and Hell, and all was lost. He became what Nietzsche has called “the pale criminal” : “An idea made this man pale. Adequate was he to his deed when he did it: but the idea of it he could not bear, when it was done.”Note 40

And so we may say in summary at this point that the first and absolutely essential characteristic of the new, secular mythology that was emerging in the literature of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries was that its structuring themes were not derived from dogma, learning, politics, or any current concepts of the general social good, but were expressions of individual experience: what I have termed Libido as opposed to Credo. Undoubtedly the myths of all traditions, great and small, must have sprung in the first instance from individual experiences: indeed we possess, in fact, a world of legends telling of the prophets and visionaries through whose personal realizations the cults, sects, and even major religions of mankind were instituted. However, in so far as these then became the authorized and even sanctified vehicles of established cultural heritages, overinterpreted as of divine origin and enforced often on pain of death — representing what the late Professor José Ortega y Gasset well defined as “collective faith” in contrast to “individual faith” — they were no longer determined by, but were rather determinants of, individual experience, feeling, thought, and motivation. In the words of Ortega y Gasset:

Apart from what individuals as individuals, that is to say, each for himself and on his own account, may believe, there exists always a collective state of belief. This social faith may or may not coincide with that felt by such and such an individual.… What constitutes and gives a specific character to collective opinion is the fact that its existence does not depend on its acceptance or rejection by any given individual. From the viewpoint of each individual life, public belief has, as it were, the appearance of a physical object. The tangible reality, so to speak, of collective belief does not consist in its acceptance by you or by me; instead it is it which, whether we acquiesce or not, imposes on us its reality and forces us to reckon with it.”Note 41

Traditional mythologies, that is to say, whether of the primitive or of the higher cultures, antecede and control experience; whereas what I am here calling Creative Mythology is an effect and expression of experience. Its producers do not claim divine authority for their human, all too human, works. They are not saints or priests but men and women of this world; and their first requirement is that both their works and their lives should unfold from convictions derived from their own experience.

IV. The Crystalline Bed

Our Tristan poet Gottfried, for instance — who was one of the earliest modern geniuses of first magnitude in the history of European letters — took particular pains to assure his readers that he knew whereof he spoke when telling of the life-empowering mysteries of love. Indeed, the only statement of this master in which he lets fall any hint of his personal life follows immediately upon his description of the love grotto and symbolic wilderness round about it:

No one could wish to be anywhere else. And this I well know; for I have been there. I, too, have tracked and pursued the wild birds and beasts in that wilderness, the deer and other game, over many a wooded stream; and yet, having so given my time, I never made a real kill. My toils and pains gained no reward.

I have found the lever and seen the latch of that cave; occasionally reached even the crystalline bed. In fact, I have danced up to it and back frequently and rather well; yet never have known rest upon it. The marble floor beside it, hard though it is, I have so trodden that were it not continually refreshed by the virtue of its greenness — in which its greatest virtue lies and through which it is ever renewed — you would see on it Love’s true tracks. My eyes I have feasted richly on those gleaming walls, and with upturned gaze to the medallion, vault, and keystone, full eagerly have I destroyed my sight on the ornaments up there, they are so bespangled with Excellence. The little sungiving windows often have sent their rays into my heart.Note 42

For the love grotto, like the center of that circle whose circumference is nowhere and center everywhere, can be found as well in the Rhineland as in the neighborhood of Tintagel; and for those at rest on its crystalline bed the conditions of time dissolve to eternity. As Gottfried tells of his two lovers there: “They looked upon each other and nourished themselves with that.… Nothing but their state of mind and love did they consume.” How few, however, have known the purity of that bed!

We may dance toward it and away, achieve glimpses, and even dwell in its beauty for a time; yet few are those who have been confirmed in that knowledge of its ubiquity which antiquity called gnosis and the Orient calls bodhi: full awakening to the crystalline purity of the bed or ground of one’s own and the world’s true being. Like perfectly transparent crystal, it is there, yet as though not there; and all things, when seen through it, become luminous in its light. Moreover, it is hard, endures forever. And the green floor across which one approaches reveals the excellence of time, which is ever-renewing.

In short, the love grotto in its wilderness can be compared to the cave-sanctuary of the classical mysteries of Eleusis, or to the sanctum of the female triad shown at Stations 4–5–6 of the golden mystery-bowl of Figure 5. The female guide to the secret gate (at Station 4) bears in hand a little pail of the ambrosia of eternity, but the raven of death appears first, since all who would know eternity must die to their temporal hopes and fears, and to their name in the world as well. The female guide and guardian marks the way both to the entry into wisdom and to the return with it to the world (Figure 5, Stations 4 and 15). Heloise, it can be truly said, had appeared as such a guide to Abelard.

In the rites of the classical mystery cults the initiatory symbolic shocks were experienced in graduated series by neophytes spiritually ready, who were carried thereby through expanding revelations to whatever sign or event, displayed within the ultimate sanctum, conferred the consummating epiphany. But life too confers initiations, and the most potent of these are of sex and death. Life too communicates revelatory shocks, but they are not pedagogically graded. These initiations are administered both to those prepared and to those who are unprepared, and while the latter either receive from them no instruction or, worse, are left damaged (insane, a bit exploded, defensively hardened, or inert), those ready receive initiations that may not only match but even surpass the revelations of the cults. For since life is itself the background from which the prophets of yore of both the great and the little ceremonial systems derived their initial inspirations, life holds still in store the possibilities of the same enlightenment anew, and of more and greater besides.

V. Aesthetic Arrest

Now, in the language of art such a seizure is termed aesthetic arrest. As characterized by James Joyce in the words of his hero Stephen Dedalus, it is that “enchantment of the heart” by which the mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing in the luminous stasis of aesthetic pleasure. “This supreme quality is felt by the artist,” Stephen declares, “when the esthetic image is first conceived in his imagination.”Note 43 By Dante the moment is described at the opening of his Vita Nuova, where Beatrice — then but a child of nine, he also a child of nine — first appeared before his eyes.

At that instant, I say truly, the spirit of life, which dwells in the most secret chamber of the heart, began to tremble with such violence that it appeared fearfully in the least pulses, and, trembling, said these words: Ecce deus fortior me, qui veniens dominabitur mihi [Behold a god stronger than I, who coming shall rule over me].

At that instant the spirit of the soul, which dwells in the high chamber to which all the spirits of the senses carry their perceptions, began to marvel greatly, and, speaking especially to the spirit of the sight, said these words: Apparuit jam beatitudo vestra [Now has appeared your bliss].

At that instant the natural spirit, which dwells in that part where our nourishment is supplied, began to weep, and, weeping, said these words: Heu miser! quia frequenter impeditus ero deinceps [Woe is me, wretched! because often from this time forth shall I be hindered].

I say that from that time forward Love lorded it over my soul, which had been so speedily wedded to him: and he began to exercise over me such control and such lordship, through the power which my imagination gave to him, that it behooved me to do completely all his pleasure.Note 44

The whole career of Dante in art unfolded from this instant; for, as he tells at the close of the Vita Nuova, having published as a youth the sonnets and canzoni of his emotion, he resolved to speak no more of that blessed one till he could more worthily treat of her. “And to attain to this,” he decared, “I study to the utmost of my power, as she truly knows. So that, if it shall please Him through whom all things live, that my life be prolonged for some years, I hope to say of her what was never said of any woman.”Note 45

James Joyce too writes of such a moment in the youth of his alter-ego, Stephen. He had arrived spiritually in a Waste Land of total disillusionment in the goals and ideals offered him by the society and its church into which he had been born. “Where,” asks the author, “was his boyhood now? Where was the soul that had hung back from her destiny, to brood alone upon the shame of her wounds and in her house of squalor and subterfuge … ?” Unhappily brooding in this vein, he was strolling barefoot along the broad beach at Dollymount, north of Dublin, beside a long rivulet in the strand. “He was alone. He was unheeded, happy and near to the wild heart of life.”

And then, behold!

A girl stood before him in midstream, alone and still, gazing out to sea. She seemed like one whom magic had changed into the likeness of a strange and beautiful seabird. Her long slender bare legs were delicate as a crane’s and pure save where an emerald trail of seaweed had fashioned itself as a sign upon the flesh. Her thighs, fuller and softhued as ivory, were bared almost to her hips, where the white fringes of her drawers were like feathering of soft white down. Her slateblue skirts were kilted boldly about her waist and dovetailed behind her. Her bosom was as a bird’s, soft and slight, slight and soft as the breast of some darkplumaged dove. But her long fair hair was girlish: and girlish, and touched with the wonder of mortal beauty, her face.

She was alone and still, gazing out to sea; and when she felt his presence and the worship of his eyes her eyes turned to him in quiet sufferance of his gaze, without shame or wantonness. Long, long she suffered his gaze and then quietly withdrew her eyes from his and bent them towards the stream, gently stirring the water with her foot hither and thither. The first faint noise of gently moving water broke the silence, low and faint and whispering, faint as the bells of sleep; hither and thither, hither and thither; and a faint flame trembled on her cheek.

— Heavenly God! cried Stephen’s soul, in an outburst of profane joy.

He turned away from her suddenly and set off across the strand. His cheeks were aflame; his body was aglow; his limbs were trembling. On and on and on and on he strode, far out over the sands, singing wildly to the sea, crying to greet the advent of the life that had cried to him.

Her image had passed into his soul for ever and no word had broken the holy silence of his ecstasy. Her eyes had called him and his soul had leaped at the call. To live, to err, to fall, to triumph, to recreate life out of life! A wild angel had appeared to him, the angel of mortal youth and beauty, an envoy from the fair courts of life, to throw open before him in an instant of ecstasy the gates of all the ways of error and glory. On and on and on and on!Note 46

In the Tristan legend, this moment of the meeting of the eyes and stilling of the world occurred when the couple, sailing from Ireland to Cornwall, drank by accident the magic potion that Isolt’s mother had prepared for the maiden’s wedding night with King Mark. There has been a difference of opinion among both poets and critics, however, as to whether this draft was merely a catalyst or itself the cause of the passion, and I suppose there must also be lovers who wonder if the wild storm they enjoy would ever have been known to them had they not tarried long — for just one more glass — that night of the moon on Caribbean waters. “The potion,” states one authority, “was indeed the true cause of the lovers’ passion, and of all that followed from it.”Note 47 “The love potion,” states another, “is a poetic symbol, and Gottfried perhaps kept the love-drink because it made an excellent climax. Love potion or not — the climax in his Tristan and Isolt was bound to come.”Note 48

We do not know how the matter stood in the earliest versions of the legend. Many scholars have pointed out, however, that in the earliest extant version — namely that of Thomas of Britain, composed c. 1165–1170 — the beautiful maid and heroic youth were already clearly in love before the potion at last unlocked their hearts.Note 49 In the later version of Eilhart von Oberge (c. 1180–1190) the influence of the magic abates after a period of four years, and in the Norman French version of Beroul (c. 1191–1205), which follows Eilhart’s tradition, the period given is three: in both, the drink is declared to be the cause. In Eilhart’s words: “For four years, their love was so great they could not be apart for even half a day. Unless they saw each other every day, they fell ill: they were in love because of that drink. And if they had not seen each other for a week, they would have died: the drink was so concocted and of such great strength. Of this you must take full account!”Note 50 Gottfried (c. 1210), on the other hand, followed Thomas, and Richard Wagner followed Gottfried.

But if the potion is not the cause of love, then what, for these great poets — Thomas, Gottfried, and Wagner — can the meaning of its magic have been?

In Wagner’s case we know from his autobiography as well as letters that throughout the years of the composition of his Tristan und Isolde, 1854–1859, he was in rapturous love with the wife, Mathilde, of his most generous friend and benefactor, Otto Wesendonck; even conceiving of himself as Tristan, Wesendonck as King Mark, and his muse Mathilde as Queen Isolde, in whose arms (according to his own oft repeated words) he desired to die. For, like Gottfried, this incurable lover of other men’s wives also had danced rather well and frequently to the crystalline bed and back, yet never had known rest upon it. And in fact, if such poets ever had found that rest, we should never have had their works.

“Because I have never tasted the true bliss of love,” Wagner wrote to his friend Franz Liszt in December 1854, “I shall raise a monument to that most beautiful of all dreams, wherein, from beginning to end, this love may for once drink to its full.”Note 51 He had met Mathilde, his Beatrice, two years before. And — what is no less relevant — he had discovered in the language of philosophy, like Dante, the means not only to read in depth the secret of his stricken heart, but also to render the import of its sweetly bitter agony in the timeless metaphors of myth. For, as we learn from his own account in the autobiography, it was in the year of his conception of this monument to a dream that he found the works of Schopenhauer; and, as he declares in so many words: “It was certainly, in part, the serious mood into which Schopenhauer had transposed me and which now was pressing for an ecstatic expression of its structuring ideas, that inspired in me the conception of a Tristan und Isolde.” Note 52

Schopenhauer, it will be recalled, treats of love as the great transforming power that converts the will to live into its opposite and reveals thereby a dimension of truth beyond the world dominion of King Death: beyond the boundaries of space and time and the turbulent ocean, within these bounds, of our life’s conflicting centers of self-interest. As he writes in his famous paper on “The Foundation of Morality,” crowned in the year 1840 by the Royal Danish Society of Sciences: “If I perform an act wholly and solely in the interest of another, it is then his weal and woe that have become my immediate concern — just as in every other act of mine, the interest served is my own.…

“But how,” he then asks, “can it possibly be that the weal and woe of another should directly move my will; that is to say, become my motivation, as though the end served were my own: indeed, and even occasionally to such a degree that my own well being and suffering — which are normally my only two springs of conduct — should remain more or less ignored?”

He replies in a fundamental passage that can be read, now, as the grounding theme not only of Wagner’s Tristan but also of his Parsifal — and of the Ring der Nibelungen as well:

Obviously this can occur only because another can actually become the final concern of my willing — as I am myself its usual concern: that is to say, because I can desire his weal and suffer his woe as acutely as though they were my own. But this necessarily presupposes that I can actually participate sympathetically in his pain, can experience his pain as otherwise only my own, and consequently can truly desire his good, as otherwise only my own. Which, in turn, demands, however, that I should for a certain time become identified with him: demands, that is to say, that the final distinction between me and him, which is the premise of my egoism, should, to some degree at least, be suspended. And since I am not actually in the skin of that other, it can be only through my knowledge of him, his image in my head, that I can become to such a degree identified with him as to act in a way that annuls the difference between us.

Having thus reasoned, Schopenhauer now proceeds to his metaphysical judgment; and in the light of the luminous words that we have just read of Heloise to Abelard, these relatively dispassionate paragraphs of the lucid bachelor philosopher will seem rather to understate than to overstate the message that Wagner echoed and amplified in the mild and gentle swelling strains of Isolde’s “Liebestod.”

The sort of act that I am here discussing [states Schopenhauer] is not something that I have merely dreamed up or conjured out of thin air, but a reality — in fact, a not unusual reality: it is, namely, the everyday phenomenon of Mitleid, compassion, which is to say: immediate participation, released from all other considerations, first, in the pain of another, and then, in the alleviation or termination of that pain . . . : which alone is the true ground of all autonomous righteousness and of all true human love. An act can be said to have genuine moral worth only in so far as it stems from this source; and conversely, an act from any other source has none. The weal and woe of another comes to lie directly on my heart in exactly the same way — though not always to the same degree — as otherwise only my own would lie, as soon as this sentiment of compassion is aroused, and therewith, the difference between him and me is no longer absolute. And this really is amazing — even mysterious. It is, in fact, the great mystery inherent in all morality, the prime integrant of ethics, and a gate beyond which the only type of speculation that can presume to venture a single step must be metaphysical.Note 53

It is fascinating to read in Wagner’s account of his studies of these years that, even while engrossed in his volumes of Schopenhauer and settling down to his Tristan, he became so deeply interested in Eugene Burnoufs Introduction á l’histoire du Bouddhisme indien (1844) that for a time he thought of writing an opera “based on the simple legend,” as he tells us, “of the reception of a maiden of an untouchable caste into the exalted mendicant order of Shakyamuni; she having made herself worthy of this, through her most passionately intensified and purified love for the Buddha’s chief disciple Ananda.”Note 54 But Schopenhauer had himself already recognized, acknowledged, and even celebrated the relationship of his metaphysics not only to Indian Buddhist and Vedantic thought, but to an ever-present heretical strain in Occidental philosophy as well. As we read, for instance, turning with Wagner once again to the prize essay, “On the Foundation of Morality”:

This doctrine, that plurality is merely illusory, and that in all the individuals of this world — no matter how great their number, as they appear beside each other in space and after each other in time — there is made manifest only one, single, truly existent Being, present and ever the same in all, was known to the world, even ages before Kant. In fact, it can be said to have been with us through all time. For, in the first place, it is the chief and fundamental teaching of the oldest books in the world, the sacred Vedas, the dogmatic portion — or better, esoteric meaning — of which is preserved for us in the Upaniṣads, throughout which the same great teaching is to be found tirelessly restated in endless variation on practically every page, as well as allegorized in multitudes of similes and figures. That it was basic, also, to the wisdom of Pythagoras, there can be no doubt, even in spite of our paucity of information concerning that philosopher; and practically the entire body of teaching of the Eleatic school consisted of this doctrine, as everybody knows. The Neoplatonists were literally soaked in it: “Through the unity of all,” they wrote, “all souls are one” (διὰ τὴν ἑνότητα ἁπάντων πάσας ψυχὰς μίαν εἰναι: propter omnium unitatemcunctas animas unam esse). Then in Europe, unexpectedly, we see it emerge in the ninth century in the works of Scotus Erigena,Note 55 whom it so excited that he strove to clothe it in the forms and language of the Christian faith. Among Mohammedans it is found in the inspired mysticism of the Sufis.Note 56 And yet in the more recent Occident, Giordano Bruno had to pay with a shameful and painful death for his inability to suppress an urge to proclaim its general truth. The Christian mystics, no matter when or where they appear, can be seen caught in this realization — even against their will and in spite of every effort. Spinoza’s name is identified with it. And in our own day, at last — now that Kant has blown the old dogmatic theology to bits and the world stands appalled among the smoking ruins — the same perception is restated in the eclectic philosophy of Schelling [1775–1854], Uniting deftly in a single system the doctrines of Plotinus, Spinoza, Kant, and Jacob Boehme, combined with the findings of modem science, Schelling, to meet the pressing need of his generation, developed his own variations on the common themes — so that this knowledge has now gained general credit among German scholars and is known even to the educated public. As in the words of Voltaire:

On peut assez longtemps, chez notre espèce,

Fermer la porte à la raison.

Mais, dès qu’elle entre avec adresse,

Elle reste dans la maison,

Et bientôt elle en est maîtresse.

The only exceptions today are the university professors, who face now the difficult assignment of waging war on this so-called “Pantheism.” Placed thereby in a situation of both embarrassment and jeopardy, they are clutching in their heartfelt anxiety at every sort of pitiful sophism, all kinds of bombastic phraseologies, from which to piece together an acceptable disguise for their cherished, specially privileged, old cutaway-coat philosophy.

In brief: The Ἑν και παν has been forever the laughingstock of fools and the everlasting meditation of the wise. And yet, no rigorous proof has ever been, or can be, given for it, except by way of the demonstrations of Kant — who, however, did not complete the proof himself, but, like a sharp debater, presented only his premises, leaving to his audience the pleasure of arriving at the necessary conclusion.