Chapter 1

Experience and Authority

I. Creative Symbolization

In the earlier volumes of this survey of the historical transformations of those imagined forms that I am calling the “masks” of God, through which men everywhere have sought to relate themselves to the wonder of existence, the myths and rites of the Primitive, Oriental, and Early Occidental worlds could be discussed in terms of grandiose unitary stages. For in the history of our still youthful species, a profound respect for inherited forms has generally suppressed innovation. Millenniums have rolled by with only minor variations played on themes derived from God-knows-when. Not so, however, in our recent West, where, since the middle of the twelfth century, an accelerating disintegration has been undoing the formidable orthodox tradition that came to flower in that century, and with its fall, the released creative powers of a great company of towering individuals have broken forth: so that not one, or even two or three, but a galaxy of mythologies — as many, one might say, as the multitude of its geniuses — must be taken into account in any study of the spectacle of our own titanic age. Even in the formerly dominant, but now distinctly subordinate, sphere of theology there has arisen, since the victories of Luther, Melanchthon, and the Augsburg Confession of 1530, a manifold beyond reckoning of variant readings of the Christian revelation; while in the fields of literature, secular philosophy, and the arts, a totally new type of non-theological revelation, of great scope, great depth, and infinite variety, has become the actual spiritual guide and structuring force of the civilization.

In the context of a traditional mythology, the symbols are presented in socially maintained rites, through which the individual is required to experience, or will pretend to have experienced, certain insights, sentiments, and commitments. In what I am calling “creative” mythology, on the other hand, this order is reversed: the individual has had an experience of his own — of order, horror, beauty, or even mere exhilaration — which he seeks to communicate through signs; and if his realization has been of a certain depth and import, his communication will have the value and force of living myth — for those, that is to say, who receive and respond to it of themselves, with recognition, uncoerced.

Mythological symbols touch and exhilarate centers of life beyond the reach of vocabularies of reason and coercion. The light-world modes of experience and thought were late, very late, developments in the biological prehistory of our species. Even in the lifecourse of the individual, the opening of the eyes to light occurs only after all the main miracles have been accomplished of the building of a living body of already functioning organs, each with its inherent aim, none of these aims either educed from, or as yet even known to, reason; while in the larger course and context of the evolution of life itself from the silence of primordial seas, of which the taste still runs in our blood, the opening of the eyes occurred only after the first principle of all organic being (“Now I’ll eat you; now you eat me!”) had been operative for so many hundreds of millions of centuries that it could not then, and cannot now, be undone — though our eyes and what they witness may persuade us to regret the monstrous game.

The first function of a mythology is to reconcile waking consciousness to the mysterium tremendum et fascinans of this universe as it is: the second being to render an interpretive total image of the same, as known to contemporary consciousness. Shakespeare’s definition of the function of his art, “to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature,” is thus equally a definition of mythology. It is the revelation to waking consciousness of the powers of its own sustaining source.

A third function, however, is the enforcement of a moral order: the shaping of the individual to the requirements of his geographically and historically conditioned social group, and here an actual break from nature may ensue, as for instance (extremely) in the case of a castrato. Circumcisions, subincisions, scarifications, tattoos, and so forth, are socially ordered brands and croppings, to join the merely natural human body in membership to a larger, more enduring, cultural body, of which it is required to become an organ — the mind and feelings being imprinted simultaneously with a correlative mythology. And not nature, but society, is the alpha and omega of this lesson. Moreover, it is in this moral, sociological sphere that authority and coercion come into play, as they did mightily in India in the maintenance of caste and the rites and mythology of suttee. In Christian Europe, already in the twelfth century, beliefs no longer universally held were universally enforced. The result was a dissociation of professed from actual existence and that consequent spiritual disaster which, in the imagery of the Grail legend, is symbolized in the Waste Land theme: a landscape of spiritual death, a world waiting, waiting — “Waiting for Godot!” — for the Desired Knight, who would restore its integrity to life and let stream again from infinite depths the lost, forgotten, living waters of the inexhaustible source.

The rise and fall of civilizations in the long, broad course of history can be seen to have been largely a function of the integrity and cogency of their supporting canons of myth; for not authority but aspiration is the motivater, builder, and transformer of civilization. A mythological canon is an organization of symbols, ineffable in import, by which the energies of aspiration are evoked and gathered toward a focus. The message leaps from heart to heart by way of the brain, and where the brain is unpersuaded the message cannot pass. The life then is untouched. For those in whom a local mythology still works, there is an experience both of accord with the social order, and of harmony with the universe. For those, however, in whom the authorized signs no longer work — or, if working, produce deviant effects — there follows inevitably a sense both of dissociation from the local social nexus and of quest, within and without, for life, which the brain will take to be for “meaning.” Coerced to the social pattern, the individual can only harden to some figure of living death; and if any considerable number of the members of a civilization are in this predicament, a point of no return will have been passed.

Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Discours sur les arts et sciences, published 1749, marked an epoch of this kind. Society was the corruption of man; “back to nature” was the call: back to the state of the “noble savage” as the model of “natural man” — which the savage, with his tribal imprints, was no more, of course, than was Rousseau himself. For as faith in Scripture waned at the climax of the Middle Ages, so at the climax of the Age of Enlightenment, did faith in reason: and today, two centuries later, we have T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (published 1922, with footnotes):Note 1

Here is no water but only rock

Rock and no water and the sandy road

The road winding above among the mountains

Which are mountains of rock without water

If there were water we should stop and drink

Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think

Sweat is dry and feet are in the sand

If there were only water amongst the rock

Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit

Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit

There is not even silence in the mountains

But dry sterile thunder without rain

There is not even solitude in the mountains

But red sullen faces sneer and snarl

From doors of mudcracked houses

The fourth and most vital, most critical function of a mythology, then, is to foster the centering and unfolding of the individual in integrity, in accord with d) himself (the microcosm), c) his culture (the mesocosm), b) the universe (the macrocosm), and a) that awesome ultimate mystery which is both beyond and within himself and all things:

Wherefrom words turn back,

Together with the mind, not having attained.Note 2

Creative mythology, in Shakespeare’s sense, of the mirror “to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure,”Note 3 springs not, like theology, from the dicta of authority, but from the insights, sentiments, thought, and vision of an adequate individual, loyal to his own experience of value. Thus it corrects the authority holding to the shells of forms produced and left behind by lives once lived. Renewing the act of experience itself, it restores to existence the quality of adventure, at once shattering and reintegrating the fixed, already known, in the sacrificial creative fire of the becoming thing that is no thing at all but life, not as it will be or as it should be, as it was or as it never will be, but as it is, in depth, in process, here and now, inside and out.

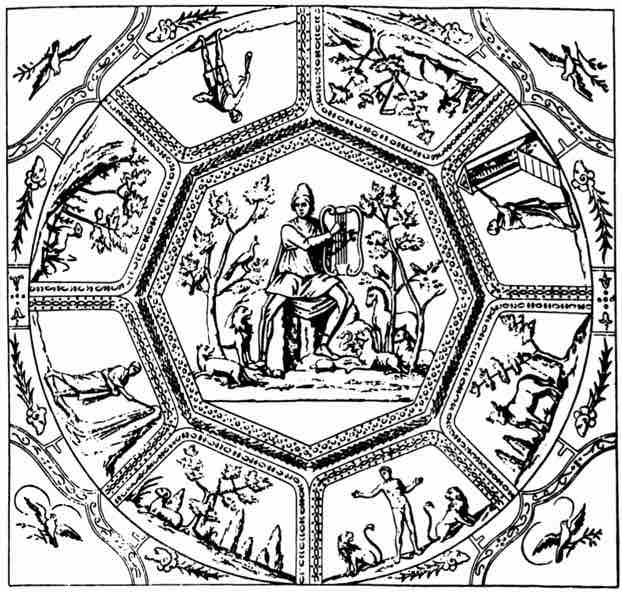

Figure

3. Orpheus the Savior; Domitilla Catacomb, (artist's representation of fresco, Rome, 3rd

century a.d.)

Figure 3 shows an early Christian painting from the ceiling of the Domitilla Catacomb in Rome, third century a.d. In the central panel, where a symbol of Christ might have been expected, the legendary founder of the Orphic mysteries appears, the pagan poet Orpheus, quelling animals of the wilderness with the magic of his lyre and song. In four of the eight surrounding panels, Old and New Testament scenes can be identified: David with his sling (upper left), Daniel in the lion’s den (lower right), Moses drawing water from the rock, Jesus resurrecting Lazarus. Alternating with these are four animal scenes, two exhibiting, among trees, the usual pagan sacrificial beast, the bull; two, the Old Testament ram. Toward the corners are eight sacrificed rams’ heads (Christ, the sacrificed “Lamb of God”), each giving rise to a vegetal spray (the New Life), while in each of the corners Noah’s dove bears the olive branch telling of the reappearance of land after the Flood. The syncretism is deliberate, uniting themes of the two traditions of which Christianity was the product, and thus pointing through and beyond all three traditions to the source, the sourceexperience of a truth, a mystery, out of which their differing symbologies arose. Isaiah’s prophecy of the Messianic age, when “the wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard lie down with the kid” (Isaiah 11:6), and the Hellenistic mystery theme of the realization of harmony in the individual soul, are recognized as variants of one and the same idea, of which Christ was conceived to be the fulfillment: the underlying theme in all being of the life transcending death.

We may term such an underlying theme the “archetypal, natural, or elementary idea,” and its culturally conditioned inflections “social, historical, or ethnic ideas.”Note 4 The focus of creative thought is always on the former, which then is rendered, necessarily, in the language of the time. The priestly, orthodox mind, on the other hand, is always and everywhere focused upon the local, culturally conditioned rendition.

Figure

4. Tristan Harping for King Mark (glazed tile, England, c.1270)

Figure 4, from a set of pavement tiles from the ruins of Chertsey Abbey (Surrey), c. 1270 a.d., shows the youthful Tristan harping for his Uncle Mark. No one regarding this in its time would have failed to associate the scene with the young David harping for King Saul. “Saul,” we are told, “was afraid of David because the Lord was with him but had departed from Saul” (I Samuel 18:12). By analogy, as Saul’s kingdom went to David, so Mark’s queen to his nephew. The ruler according to the order merely of the day (the ethnic sphere), out of touch with the enduring principles of his own nature and the world (the elementary), is displaced in his sovereignty (in his kingdom/in his queen) by the revealer of the concealed harmony of all things.

By analogy, as Saul’s kingdom went to David, so Mark’s queen to his nephew. The ruler according to the order merely of the day (the ethnic sphere), out of touch with the enduring principles of his own nature and the world (the elementary), is displaced in his sovereignty (in his kingdom / in his queen) by the revealer of the concealed harmony of all things.

II. Where Words Turn Back

Figure

5. Orphic Sacramental Bowl (cast gold, Rumania, 3rd or 4th century

a.d.)

Figure

6. Central Figure of the Orphic Bowl

Figures 5 and 6 show the interior and the central figure of an Orphic sacramental bowl of gold, dating approximately from the period of the Domitilla ceiling. It was unearthed in the year 1837, near the town of Pietroasa, in the area of Buzau, Rumania, together with twenty-one other precious pieces; and since one of the large armbands of the hoard was inscribed with runic characters, a number of the scholars first examining the treasure suggested that it might have been buried by the Visigothic king Athanaric when, in the year 381 a.d., he fled for protection from the Huns to Byzantium. During the First World War the whole collection was taken to Moscow to be kept from the Germans, where it was melted down by the Russian Communists for its gold; so that nothing can now be done to establish its origin or precise date. However, during the winter of 1867–1868 it had been on loan for six months in England, where it was photographed and galvanoplastically reproduced.

The figures are crude, according to classical standards, and may represent the work of a provincial craftsman. Rumania, it may be recalled, was for centuries occupied by the Roman border legions defending the Empire from the Goths and other Germanic tribes, with, however, increasingly numerous German auxiliaries and even officers of rank. Throughout the area and on into Central Europe shrines of the Mithra mysteries have been discovered in abundance;Note 5 and as this bowl reveals, the Orphic cult also was known. Moreover, since it was from this province that a continuous stream of Hellenistic influences flowed northward, throughout the Roman period, to the Celtic as well as to the German tribes, and from which, furthermore, in the Middle Ages, a powerful heresy of Gnostic-Manichaean cast flooded westward into southern France (precisely in the century of the rise of the love cult of the troubadours and legends of the Grail), the figures on this Orphic bowl bear especial relevance not only to the religious but also to the literary and artistic traditions of the West. Indeed, already at its first station, showing Orpheus as a fisherman, a host of associations springs to mind.

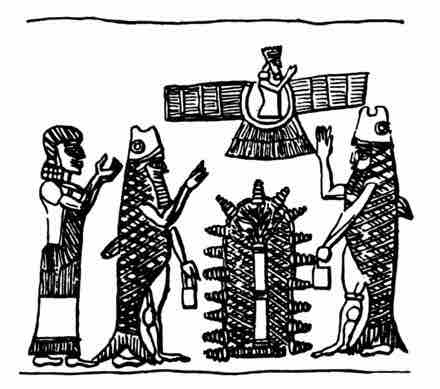

Figure

7. The Warden of the Fish (terra cotta, Babylonia, 2nd millennium

b.c.)

1. Orpheus the Fisherman is shown on the bowl with his fishing pole, the line wound around it, a mesh bag in his elevated hand, and a fish lying at his feet. One thinks of Christ’s words to his fishermen apostles, Peter, James, and John: “I shall make you fishers of men”;Note 6 but also of the Fisher King of the legends of the Grail: and with this latter comes the idea that the central figure of the vessel, seated with a chalice in her hands, may be a prototype of the Grail Maiden in the castle to which the questing knight was directed by the Fisher King. A very early model of the mystic fisherman appears on Babylonian seals in a figure known as the “Warden of the Fish” (Figure 7),Note 7 while the most significant current reference is on the ring worn by the Pope, the “Fisherman’s Ring,” which is engraved with a representation of the miraculous draft of fishes that afforded the occasion for Christ’s words.

Figure

8. Christian Neophyte in Fish Garb; early Christian lamp

For the fishing image was appropriate in a special way to the early Christian community, where in baptism the neophyte was drawn from the water like a fish. Figure 8 is an early Christian earthenware lamp showing such a neophyte clothed as a fish, to be born, as it were, a second time, in accordance with Christ’s teaching that “unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God.”Note 8 The Hindu legend of the birth of the great sage Vyasa from a fish-born virgin nicknamed Fishy Smell (whose proper name, however, was Truth) may recur to mind at this point;Note 9 and one thinks also of Jonah reborn from the whale — of whom it is said in the Midrash that in the belly of the fish he typifies the soul of man swallowed by Sheol.Note 10 Christ himself is symbolized by a fish, and on Friday a fish meal is consumed.

Figure

9. Fish Gods at the Tree of Life; Assyria, c. 700 b.c.

Evidently we have here broken into a context of considerable antiquity, referring to a plunge into abyssal waters, to emerge as though reborn; of which spiritual experience perhaps the best-known ancient legend is of the plunge of the Babylonian King Gilgamesh to pluck the plant of immortality from the floor of the cosmic ocean.Note 11 Figure 9, from an Assyrian cylinder seal of c. 700 bc. (the period to which the prophet Jonah is commonly assigned), shows a worshiper with outstretched arms arriving at this immortal plant on the floor of the abyss, where it is found guarded by two fish-men.Note 12 The god Assur of Nineveh (to which city Jonah was traveling when he was swallowed by the whale) floats wonderfully above the scene. But Gilgamesh, it is recalled, lost the plant after he had come ashore. It was eaten by a serpent; so that, whereas serpents now can shed their skins to be reborn, man is mortal and must die. As in the words of the God of Eden to Adam after the fall, so here: man is dust and unto dust he shall return.Note 13

Such, however, was not the idea of the Greeks of the mystery tradition, who told of God (Zeus) creating man, not from lifeless dust, but from the ashes of the Titans who had consumed his son, Dionysus.Note 14 Man is in part, therefore, of immortal Dionysian substance, though in part, also, of Titanic, mortal; and in the mystery initiations he is made cognizant of the portion within him of the ever-living god who died to himself to live manifold in us all.

In the sixteen figures of the once golden sacramental bowl of Figure 5, the sequence of initiatory stages of that inward search is represented. Having been drawn to the mystic gate by Orpheus’s fishing line, the neophyte seen at Station 3 commences the night-sea journey, sunwise round the bowl. Like the setting sun, he descends in symbolic death into the earth and at Station 14 reappears to a new day, qualified to experience the “meeting of the eyes” of Hyperborean Apollo at Station 16.

2. A naked figure in attendance at the entrance, bearing on his head a sacred chest (cista mystica), and with an ear of grain in hand (In classical reliefs such figures, bearing sacred chests, are frequently smaller than those around them. We are not to interpret this figure as a child.), offers the contents of the chest to:

3. A kilted male, the neophyte. He holds a torch in his left hand, symbol of the goddess Persephone of the netherworld, to whose mystery (the truth about death) he is to be introduced. Yet his eyes still hold to those of his mystagogue, the Fisher. The raven of death perches on his shoulder (Compare the symbolism of the initiations of Mithra. Occidental Mythology, and the Irish goddess of death.), while with his right hand he lifts from the mystic chest an immense pine cone symbolic of the life-renewing principle of the seed, which the death and decay of its carrier, the cone, are to set free. For, as in the words of Paul, so here: “what you sow does not come to life unless it dies.… What is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable.”Note 15

4. A draped female figure, porteress of the sanctuary, bearing in her left hand a bowl and in her right a pail, conducts the neophyte within. For as the female power resident in the earth releases the seed-life from the cone, so will the mystery of the goddesses release the mind of this neophyte from its commitment to what Paul (using the language of the mysteries) termed “this body of death.”Note 16 On the early Mesopotamian cylinder seals, porters at the entrances to shrines carried pails, like that of this figure, of the mead of immortal life.Note 17 The fish-men of Figure 9 also carry such pails. The neophyte is being guided to the sanctuary of the two goddesses:

5. Demeter enthroned, in her right hand holding the flowering scepter of terrestrial life, and in her left the open shears by which life’s thread is cut; and

6. Her daughter, Persephone, as mistress of the netherworld, enthroned beyond the reign of Demeter’s scepter and shears. The torch, her emblem, symbolic of the light of the netherworld, is a regenerative spiritual flame.

The neophyte now has learned the meaning of the raven that perched on his shoulder when he entered the mystic way and of the torch and cone that were placed in his hands. We see him next, therefore, as:

7. The initiated mystes, standing with his left hand reverently to his breast, holding a chaplet in his right.

8. Tyche, the goddess of Fortune,touches the initiate with a wand that elevates his spirit above mortality, holding on her left arm a cornucopia, symbolic of the abundance she bestows.

We are now just halfway around, at the point, as it were, of midnight, where:

9. Agathodaemon, the god of Good Fortune, holding in his right hand, turned downward, the poppy stalk of the sleep of death, and in his left, pointing upward, a large ear of the grain of life, is to introduce the initiate to:

10. The Lord of the Abyss. With his hammer in his right hand and on his left arm a cornucopia, this dark and terrible god is enthroned upon a scaly sea-beast, a sort of modified crocodile. His hammer is the instrument of Plato’s Divine Artificer, by whom the temporal world is fashioned on the model of eternal forms. But the same hammer is symbolic, also, of the lightning bolt of illumination, by which ignorance concerning this same temporal world is destroyed. Compare the symbolism of the god Zervan Akarana in the initiations of Mithraism;Note 18 also, the Indian divinities who both create and destroy the world illusion.

The old Sumerian serpent-god Ningizzida is the ultimate archetype of this lord of the watery abyss from which mortal life arises and back to which it returns.Note 19 Among the Celts, the underworld god Sucellos represented this same dark power;Note 20 in the classical mythologies he was Hades-Pluto-Poseidon; and in Christian mythology he is, exactly, the Devil.

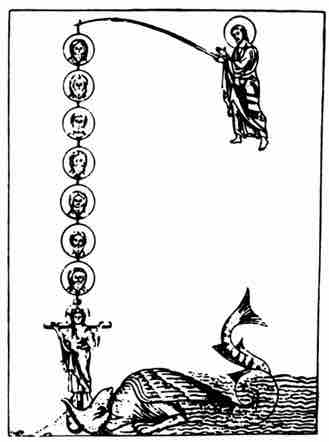

Figure

10. God the Father, Fishing; c. 1180 a.d.

Figure 10 will show, however, that there is an important difference between the Devil’s place in the Christian universe and Ningizzida’s or Hades-Pluto-Poseidon’s in the pagan. The illustration is from an illuminated twelfth-century handbook of everything worth knowing, called The Little Garden of Delights (Hortulus deliciarum), compiled by the Abbess Herrad von Landsberg (d. 1195) in her convent in Hohenburg, Alsace, to assist her nuns in their teaching tasks.Note 21 Its figure is based on a metaphor coined by Gregory the Great, as Pope (590–604), to illustrate the doctrine of salvation that was most favored throughout Christendom for the first twelve hundred years. Known as “the ransom theory of salvation,” it is based on the words of the Savior himself, as reported in the Mark and Matthew Gospels: “For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.”Note 22 The second-century Greek bishop of Lyons, Irenaeus (130?–202?) and the Alexandrian theologian Origen (185?–254?) seem to have been among the first to read a theological thesis into this metaphor, which then was accepted even by Augustine (354?–430).Note 23

What we see is God the Father in heaven, fishing for the Devil in the form of the monster Leviathan, using for his line the kings of the royal house of David, with the Cross for his hook, and his Son affixed there as bait. For the Devil, through his ruse in the Garden of Eden, had acquired a legal right to man’s soul, which God, as a just God, had to honor. However, since the right had been acquired by a ruse, God might justly terminate it by a ruse. He offered as ransom for the soul of man the soul of his own divine Son, knowing, as the Devil did not, that since the Second Person of the Trinity is beyond the touch of corruption, Satan would not be able to lay hold. Christ’s humanity was thus the bait at which the Devil snapped like a fish, only to be caught on the hook of the Cross, from which the Son of God, through his resurrection, escaped.

It is little wonder that Saint Anselm (1033–1109) should have thought a new interpretation of the Incarnation desirable. In his celebrated tract, Cur deus homo? (“Why did God become Man?”), which marks an epoch in Christian theology, he proposed that the claimant in the case was not the Devil but the Father, whose command had been disobeyed; and the claim, moreover, was against man. What was required, consequently, was not a ransom rendered to Satan, but atonement rendered to God, in the sense of satisfaction for an injury sustained. The injury, however, had been against the infinite majesty of God, whereas man is finite. Hence, no act or offering by any number of men could ever have cleared the account. And God’s whole program for creation was meanwhile being frustrated by this legal impasse. Cur deus homo? The answer is suggested in two stages:

-

In Christ, true God and true Man, the species Man had a perfect representative, who at the same time was infinite and consequently adequate to make satisfaction for an infinite offense.

-

Merely living perfectly, as Christ did, however, would not have sufficed to compensate for man’s fault, since living perfectly is no more than man’s duty and produces no merit to spare. “If man has had a sweet experience in sinning, is it not fitting,” Anselm argued “that he should have a hard experience in satisfying?

… But there is nothing harder or more difficult that a man can suffer for the honor of God spontaneously, and not of debt, than death, and in no way can man give himself more fully to God than when he surrenders himself to death for His honor.”

Christ’s dying was necessary because he willed it; but at the same time was not necessary, because God did not demand it. The Son’s death, therefore, was voluntary, and the Father had to recompense him. However, since nothing could be given to the Son, who already had all, Christ passed the benefit earned to mankind; so that God now rejects no one who comes to him in the name of Christ — on condition that he come as Holy Scripture directs.Note 24

It is difficult to believe today that anyone could ever have taken seriously either of these attributions of legal mathematics to a God supposed to be transcendent. They are known, respectively, as the “ransom” and the “penal” doctrines of redemption. A third suggestion was offered by Saint Anselm’s brilliant contemporary, the lover of Heloise, Abelard (1079–1142), but rejected by the churchmen as unacceptable; namely, that Christ’s self-offering was addressed neither to the Devil nor to God, but to man, to prove God’s love, to waken love in response, and thus to win man back to God. All that was asked for redemption was a response of love in return, and the power of love then itself would operate to effect the reunion that is mankind’s proper end.Note 25 However, as Professor Etienne Gilson of the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, Toronto, points out in his History of Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages,Note 26 there is throughout Abelard’s thinking an indifference to the distinction between natural and supernatural grace, the merely natural virtues of the unbaptized and the priceless gift of God in the sacraments. Abelard was one of those who believed that the unbaptized might be saved; which implied that the sacraments were unnecessary, and natural grace sufficient for salvation. What about the pagan philosophers on whose writings Christian thought itself was grounded? he asked. And what of the prophets and all those who have lived by their words?

“Abélard,” writes Professor Gilson, “is here freely indulging in his general tendency to look upon grace as a blossoming of nature, or inversely … to conceive Christianity as the total verity which includes all others within it.… Christian revelation was never, for him, an impassable barrier dividing the chosen from the condemned and truth from error.… One cannot read Abelard without thinking of those educated Christians of the sixteenth century, Erasmus for example, to whom the distance from ancient wisdom to the wisdom of the Gospel will seem so short.”Note 27

The biblical representation of God as somebody “up there” (rather like the god Assur in Figure 9), not the substance, but the maker of this universe, from which he is distinct, had deprived matter of a divine dimension and reduced it to mere dust. Hence, whatever the pagan world had regarded as evidence of a divine presence in nature, the Church interpreted as of the Devil. Poseidon’s trident (which in India is Śiva’s) became thus the Devil’s popular pitchfork; Poseidon’s great bull, sire of the Minotaur (in India, Śiva’s bull Nandi) gave the Devil his cloven foot and horns; the very name, Hades, of the god of the underworld became a designation of that inferno which Heinrich Zimmer once described wittily as “Mr. Lucifer’s luxury skyscraper apartment-hotel for lifers, plunged top downward in the abyss”; and the creative life-fire of the netherworld, displayed in Persephone’s torch, became a reeking furnace of sin.

The simplest way, therefore, to suggest in Christian terms the sense of the Orphic initiation at Station 10 might be to say that here the Devil himself is taken to be the immanent presence of God. However, whereas in the Christian view the Devil, like God, is an independent personage “out there,” what the mystes learned at this Orphic station was that the god of the creative sea, the moving tremendum of this world, was an aspect of himself, to be experienced within — exactly as in the Indian Tantric tradition, where all the gods and demons, heavens and hells, are discovered and displayed within us — and this ground of being, which is both giver and taker of the forms that appear and disappear in space and time, though dark indeed, cannot be termed evil unless the world itself is to be so termed. The lesson of Hades-Pluto, Poseidon-Neptune-Śiva, is not that our mortal part is ignoble but that within it — or at one with it — is that immortal Person whom the Christians split into God and Devil and think of as “out there.”

And so we move to the next station, of:

11. The Mystes, fully initiate. He bears a bowl, as though endowed with a new capacity. His hair is long, and his right hand, on his belly, suggests a woman who has conceived. Yet the chest is clearly male. Thus an androgyne theme is suggested, symbolic of a spiritual experience uniting the opposed ways of knowledge of the male and female; and fused with this idea is that of a new life conceived within. Above the crown of the head, symbolic center of realization, is a pair of spiritual wings. The initiate is now fit to return to the world of normal day. There follow:

12 and 13. Two young men regarding each other. As to the identity of these, there has been considerable academic disagreement. The French archaeologist Charles de Linas believed they represented Castor and Triptolemus (For Triptolemus, see Occidental Mythology, Figure 14.). However, to this the late Professor Hans Leisegang of the University of Jena objected reasonably that in that case Castor would have been separated from his inseparable twin, Pollux.Note 28 The pair, he suggested, might rather represent two mystes bearing scourges (for in certain mys-teries scourging played a part). However, to me this seems unlikely, since if scourging were to have been noticed, we should have had it earlier in the series, on the way down, not the way up.

For myself, I cannot see why the two should not be identified as (12) the immortal twin Pollux and (13) the mortal Castor. For the mystes, departing from the sanctuary of his experience of androgyny (beyond the opposites not only of femininity and masculinity but also of life and death, time and eternity), must resume his place in the light world without forfeiting the wisdom gained; and exactly proper to the sense of such a passage is the dual symbol of the twins, immortal and mortal, respectively, Pollux and Castor. The legs of the two are straight, the only such in the composition; they touch at the feet, and the two are looking at each other. Both were horsemen; hence the whips. Furthermore, on the shoulder of the second the raven again perches that has not been seen since the passage of the dual-goddess threshold, opposite, where the passage was into the realm of knowledge beyond death, from which we are now emerging. The raven on the right shoulder and torch in the left hand here correspond to the raven and torch at Station 3, to which the whip in the right hand now adds a token of the initiate’s acquired knowledge of his immortal part as a member of the symbolic twin-horsemen syzygy. And I am encouraged in this interpretation by the view of Professor Alexander Odobesco of the University of Bucharest, the first scholar to examine this bowl, who identified these two as the Alci, the German counterparts of Castor and Pollux; for since both the Greeks and the Romans strove generally to recognize analogies between their own and alien gods, it is altogether likely that, whether in the hands of some German chieftain or in those of a Roman officer, the twin horsemen would have been recognized as readily by their German as by their Greek or Roman names.

The last three figures of the series return us to the light world:

14. The returning mystes, clothed exactly as at Station 3, now bears in his left hand a basket of abundance and in his right a sage’s staff. He is conducted by:

15. A draped female figure with pail and bowl, counterpart of the figure at Station 4. Vines and fruit are at her right and left: fulfillment has been attained. She leads the initiate toward the god to whose vision he has at last arrived, on whom his eyes are fixed:

16. Hyperborean Apollo, the mythopoetic personification of the transcendent aspect of the Being of beings, as the Lord of the Abyss at Station 10 represented the immanent aspect of the same. He sits gracefully with lyre in hand and a griffin reposing at his feet: the very god addressed as the Lord of both Day and Night in the Orphic hymns:

For thou surveyest this boundless ether all,

And every part of this terrestrial ball

Abundant, blessed; and thy piercing sight

Extends beneath the gloomy, silent night;

The world’s wide bounds, all-flourishing, are thine,

Thyself of all the source and end divine.Note 29

Having circled the full round, the mystes now is in possession of the knowledge of that mover beyond the motions of the universe, from whose substance the sun derives its light and the dark its light of another kind. The lyre suggests the Pythagorean “harmony of the spheres,” and the griffin at the god’s feet, combining the forms of the solar bird and solar beast, eagle and lion, is the counterplayer to the symbolic animal-fish, the crocodile of night. Moreover, the knowledge through these two gods of the mystery beyond duality is the only knowledge adequate to the sense of: The Great Goddess (Figure 6). By whatever name, she it is within whose universal womb both day and night are enclosed, the worlds both of life, symbolized by Demeter (5) , and of death, life’s daughter, Persephone (6). The grapevine entwining her throne is matched by that of the outer margin of the bowl; and she holds in both hands a large chalice of the ambrosia of this vine of the universe: the blood of her ever-dying, ever-living slain and resurrected son, Dionysus-Bacchus-Zagreus — or, in the older, Sumero-Babylonian myths, Dumuzi-absu, Tammuz — the “child of the abyss,” whose blood, in this chalice to be drunk, is the pagan prototype of the wine of the sacrifice of the Mass, which is transubstantiated by the words of consecration into the blood of the Son of the Virgin.

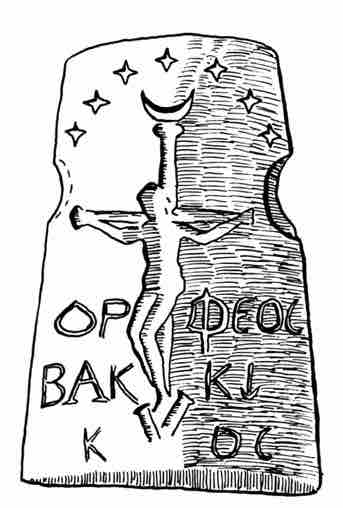

Figure

11. Orpheos Bakkikos Crucified; c. 300 a.d.

Figure 11 is from a cyclinder seal of 300

a.d.Note

30 The date is of the general period of both the

Domitilla ceiling and the Pietroasa bowl, and as Dr. Eisler, in

whose Orpheus the Fisher the figure was first published,

suggests, it must have belonged to “an Orphic initiate who had

turned Christian without giving up completely his old religious

beliefs.”Note 31 The inscription is unmistakable:

Orpheos Bakkikos. The seven stars represent the Pleiades,

known to antiquity as the Lyre of Orpheus, and the cross suggests,

besides the Christian Cross, the chief stars  of the constellation

Orion, known also as that of Dionysus. The crescent is of the

ever-waning and -waxing moon, which is three days dark as Christ

was three days in the tomb.

of the constellation

Orion, known also as that of Dionysus. The crescent is of the

ever-waning and -waxing moon, which is three days dark as Christ

was three days in the tomb.

Interpreted in Orphic terms, such a crucified redeemer, in his human character as Orpheos (True Man), would have represented precisely that “ultimate surrender of self, in love ‘to the uttermost,’” which both the Bishop John A. T. Robinson of Woolwich and the late Dr. Paul Tillich have proposed as the mystic lesson of Christ’s crucifixion.Note 32 But at the same time, in his divine character as Bakkikos (True God), the image must have symbolized that coming to us of the personified transcendent “ground of Being,” through whose willing self-dismemberment as the substance (not the creator merely) of this world, that which there is one becomes these many here — “like a felled tree, cut up into logs” (Ṛg Veda I:32).

It is, however, by way of the Goddess Mother

of the universe, whose womb is the apriority of space and time,

that the one, there, becomes these many, here. It is she who is

symbolized by the Cross; as, for instance, in the

astrological-astronomical sign signifying earth  . It is into

and through her that the god-substance pours into this field of

space and time in a continuous act of world-creative self-giving;

and through her, in return — her guidance and her teaching — that

these many are led back, beyond her reign, to the light beyond dark

from which all come.

. It is into

and through her that the god-substance pours into this field of

space and time in a continuous act of world-creative self-giving;

and through her, in return — her guidance and her teaching — that

these many are led back, beyond her reign, to the light beyond dark

from which all come.

Returning, therefore, to Figure 5, we now remark that in the inner circle surrounding her seat there is a reclining human being, apparently a shepherd, by whose legs there lies (or runs) a dog, before whose nose we see a recumbent (or fleeing) donkey colt. The reclining figure, in contrast to those upright in the outer series, suggests sleep, the spiritual state of the uninitiated natural man, who sees without understanding; whereas the knowledge gained by the mystes in the outer circle is of those eternal forms, or Platonic ideas, that are the structuring principles of all things, inherent in all, and to be recognized by the wakened mind.

In this inner circle, at the opposite point to the dreamer, two asses — recumbent and standing — browsing on a plant are themselves about to be consumed by a leopard and a lion. The lesson is the same as that of “The Self-Consuming Power” represented on the old Sumerian seal of c. 3500 b.c. reproduced in a preceding volume of this work, Oriental Mythology, Figure 2. The ever-dying, ever-living god, who is the reality of all beings, our eyes see as the consumer and consumed. However, the initiate, who has penetrated the veil of nature, knows that the one life immortal lives in all: namely, the god whose symbol is the vine here growing from the feet of the World Goddess and encircling the composition. Of old he was known as Dionysus-Orpheus-Bacchus; earlier still, Dumuzi-Tammuz; but we hear of him, also, in the words of that one, about to be crucified, who at the banquet of his Last Supper spoke (as quoted in the John Gospel) to his zodiac of apostles: “I am the vine, you are the branches. He who abides in me, and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit, for apart from me you can do nothing.”Note 33

In a word, then, the same symbols, words, and mysteries were associated with the ancient pagan vine as with the Christian gospel of the new. For the myth of the dead and resurrected god whose being is the life-pulse of the universe had been known to the pagans millenniums before the crucifixion of Christ. In the earliest agricultural communities the image had been rendered in rites of actual human sacrifice, the aim of which had been magical, to make the crops grow. In the later Hellenistic cosmopolitan cities, on the other hand, where a concern for the inner man removed from the stabilizing influences of nature and the soil was more acutely felt than the earlier, for the crops, the ancient myth became interiorized, translated from the syntax of earthmagic to spiritual initiation; from the work of enlivening fields to that of livening the soul.Note 34 And in this it became joined with Greek philosophy, science, and the arts, to uncover the ways to a knowledge of those intelligible forms that are the “models” (in Platonic terms; or, as Aristotle taught, the “entelechies”) of all things: the immanent “thoughts” of that First Mover, called God, who is both separate, “by Himself,” and yet identical with the nature of the universe as the order and potential of its parts.Note 35

And if we now ask why, in the Domitilla ceiling, it is Orpheus, not Jesus, who holds the central, solar place, the answer, I think, is clear. The Jewish idea of the Messianic age is of a time to come. The earliest Christian notion was that the time had already come. By the end of the second century, however, it was obvious that the end of time had not come. The necessity arose, therefore, to reinterpret the prophecy as referring either to an end postponed to some unspecified future date, or to an end not of the world, as in Hebrew thought, but of delusion, as in Greek. The former was the orthodox Christian solution, the latter the Orphic-Gnostic, casting Christ in the role of the mystagogue supreme. And accordingly, as we have seen, the symbol of Christ as the crucified God-Man had then to be read not in the way of either Saint Gregory’s “ransom” or Saint Anselm’s “penal” doctrine, but of Abelard’s, Paul Tillich’s, and Bishop Robinson’s, of “mutual approach”; namely, read from there to here, as of the god, the Being of beings, willingly come to the Cross to be dismembered, broken into mortal fragments, “like a felled tree cut into logs”; and simultaneously read the other way — here to there — as of the self-noughting individual abandoning attachment to his mortal portion to rejoin the archetype, thus achieving atonement, not in the penal sense of a legal “reparation for injury,” but in the earlier, mystical meaning of the term: at-one-ment.

III. The Trackless Way

“What greater misfortune for a state can be conceived than that honorable men should be sent like criminals into exile, because they hold diverse opinions which they cannot disguise? What, say I, can be more hurtful than that men who have committed no crime or wickedness should, simply because they are enlightened, be treated as enemies and put to death, and that the scaffold, the terror of evil-doers, should become the stage where the highest examples of tolerance and virtue are displayed to the people with all the marks of ignominy that authority can devise?”Note 36

These are the words of Benedict Spinoza (1632–1677), a Jew in refuge from his own synagogue, whom the German romantic Novalis (1772–1801) was to celebrate as ein gottbetrunkener Mensch, “a God-intoxicated man.” In a period of appalling religious massacres, writing, as he declared, “to show that not only is perfect liberty to philosophize compatible with devout piety and with the peace of the state, but that to take away such liberty is to destroy the public peace and even piety itself,” Spinoza represents as courageously and splendidly as anyone in the European record those principles of enlightenment and integrity that he stood for. His own writing was denounced in his time as an instrument “forged in hell by a renegade Jew and the Devil.” In a world of madmen flinging the Bible at one another — French Calvinists, German Lutherans, Spanish and Portuguese inquisitors, Dutch rabbis, and miscellaneous others — Spinoza had the spirit to point out (what should have been obvious to all) that the Bible “is in parts imperfect, corrupt, erroneous, and inconsistent with itself,” whereas the real “word of God” is not something written in a book but “inscribed on the heart and mind of man.”

The world, men had begun to learn, was not a nest of revolving crystalline spheres with the earth at its precious center and man thereon as the chief concern of the moon, the sun, the planets, the fixed stars, and, beyond all these, a King of Kings on a throne of jeweled gold, surrounded by nine rapturous choirs of many-winged luminous seraphim, cherubim, thrones, dominions, virtues, powers, principalities, archangels, and angels. Nor is there anywhere toward the core of this earth a pit of flaming souls, screaming, tortured by devils who are fallen angels all. There never was a Garden of Eden, where the first human pair ate forbidden fruit, seduced by a serpent who could talk, and so brought death into the world; for there had been death here for millenniums before the species Man evolved: the deaths of dinosaurs and of trilobites, of birds, fish, and mammals, and even of creatures that were almost men. Nor could there ever have occurred that universal Flood to float the toy menagerie of Noah’s Ark to a summit of the Elburz range, whence the animals, then, would have studiously crawled, hopped, swum, or galloped to their continents: kangaroos and duck-billed platypuses to far-away Australia, llamas to Peru, guinea pigs to Brazil, polar bears to the farthest north, and ostriches to the south.… It is hard to believe today that for doubting such extravagances a philosopher was actually burned alive in the Campo dei Fiori in Rome in the Year of Our Lord 1600; or that as late as the year of Darwin’s Origin of Species, 1859, men of authority still could quote this kind of lore against a work of science.

“The fool says in his heart, ‘There is no God’” (Psalms 14:1; 53:1). There is, however, another type of fool, more dangerous and sure of himself, who says in his heart and proclaims to all the world, “There is no God but mine.”

Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), the indiscreet philosopher who was burned in the Campo dei Fiori — where his statue by the sculptor Ferrari now stands — was incinerated not because he had said in his heart, “There is no God”; for in fact he had taught and written that there is a God, who is both transcendent and immanent. As transcendent, according to Bruno’s understanding, God is outside of and prior to the universe and unknowable by reason; but as immanent, he is the very spirit and nature of the universe, the image in which it is created, and knowable thus by sense, by reason, and by love, in gradual approximation. God is in all and in every part, and in him all opposites, including good and evil, coincide. Bruno was burned alive for teaching the truth that the mathematician Copernicus had demonstrated five years before his birth; namely, that the earth revolves around the sun, not the sun around the earth, which, as all Christian authorities, Catholic and Protestant, as well as Bruno himself, knew, was a doctrine contrary to the Bible. The actual point in question, throughout the centuries of Christian persecution, has never been faith in God, but faith in the Bible as the word of God, and in the Church ( this Church or that) as the interpreter of that word. Bruno held that the Old Testament tales teach neither science, history, nor metaphysics, but morality of a kind; and he placed them on a level with Greek mythology, which teaches morality of another kind. He also expressed unorthodox views on the delicate topics of the Virgin Birth of Jesus and the mystery of transubstantiation. The function of a church, he declared, is the same as that of a state; it is social and practical: the security of the community, the prosperity and well-doing of its members. Dissension and strife are dangerous to the state, hence the need of an authoritative doctrine and the enforcement of its acceptance and of outward conformity with it; but the Church has no right to go further, to interfere with the pursuit of knowledge, of truth, which is the object of philosophy or science.Note 37

The altogether new thing in the world that was making all the trouble was the scientific method of research, which in that period of Galileo, Kepler, Descartes, Harvey, and Francis Bacon was advancing with enormous strides. All walls, all the limitations, all the certainties of the ages were in dissolution, tottering. There had never been anything like it. In fact this epoch, in which we are participating still, with continually opening vistas, can be compared in magnitude and promise only to that of the eighth to fourth millenniums b.c.: of the birth of civilization in the nuclear Near East, when the inventions of food production, grain agriculture and stockbreeding, released mankind from the primitive condition of foraging and so made possible an establishment of soundly grounded communities: first villages, then towns, then cities, kingdoms, and empires. Leo Frobenius in his Monumenta TerrarumNote 38 wrote of the age that opened at that distant date as the Monumental Age — now closing — and of the age now before us, dawning, as the Global.

“We are concerned no longer with cultural inflections,” he declared, “but with a passage from one culture stage to another. In all previous ages, only restricted portions of the surface of the earth were known. Men looked out from the narrowest, upon a somewhat larger neighborhood, and beyond that, a great unknown. They were all, so to say, insular: bound in. Whereas our view is confined no longer to a spot of space on the surface of this earth. It surveys the whole of the planet. And this fact, this lack of horizon, is something new.”

Now it has been — as I have already said — chiefly to the scientific method of research that this release of mankind has been due, and along with mankind as a whole, every developed individual has been freed from the once protective but now dissolved horizons of the local land, local moral code, local modes of group thought and sentiment, local heritages of signs. But this scientific method was itself a product of the minds of already self-reliant individuals courageous enough to be free. Moreover, not only in the sciences but in every department of life the will and courage to credit one’s own senses and to honor one’s own decisions, to name one’s own virtues and to claim one’s own vision of truth, have been the generative forces of the new age, the enzymes of the fermentation of the wine of this great modern harvest — which is a wine, however, that can be safely drunk only by those with a courage of their own.

For this age is one of unbridled, headlong adventure, not only for those addressed to the outward world, but also for those turned inward, released from the guidance of tradition. Its motto is perhaps most aptly formulated in Albert Einstein’s statement of the principle of relativity, set down in the year 1905: “Nature is such that it is impossible to determine absolute motion by any experiment whatsoever.”Note 39 In these fifteen words we find summarized the results of a decade of experiments in various quarters of Europe, to establish some absolute standard of rest, some static environment of ether, as a fixed frame of reference against which the movements of the stars and suns might be measured. None was found. And this negative result only confirmed what Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727) had already suspected when he wrote in his Principia:

It is possible that in the remote regions of the fixed stars, or perhaps far beyond them, there may be some body absolutely at rest, but it is impossible to know from the positions of bodies to one another in our regions whether any one of these do not keep the same position to that remote body. It follows that absolute rest cannot be determined from the position of bodies in our region.Note 40

It might be said, in fact, that the principle of relativity had been defined already in mythopoetic, moral, and metaphysical terms in that sentence from the twelfth-century hermetic Book of the Twenty-four Philosophers, “God is an intelligible sphere, whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere,”Note 41 which has been quoted with relish through the centuries by a significant number of influential European thinkers; among others, Alan of Lille (1128–1202), Nicholas Cusanus (1401–1464), Rabelais (1497–1553), Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), Pascal (1623–1662), and Voltaire (1694–1778).

In a sense, then, our recent mathematicians, physicists, and astronomers have only validated for their own fields a general principle long recognized in European thought and feeling. Whereas formerly, in the old Sumerian world view, preserved in the Old Testament, the notion of a stable cosmological order had prevailed and was matched by the priestly concept of an established moral order as well; we now find that, matching our recent cosmological recognition of the relativity of all measures to the instrument doing the measuring, there is a growing realization even in the moral field that all judgments are (to use Nietzsche’s words) “human, all too human.”

Oswald Spengler, in The Decline of the West, coined the term “historical pseudomorphosis” to designate, as he explained, “those cases in which an older alien culture lies so massively over a land that a young culture, born in this land, cannot get its breath and fails not only to achieve pure and specific expression forms, but even to develop fully its own self-consciousness.”Note 42 The figure was adopted from the terminology of the science of mineralogy, where the word pseudomorphosis, “false formation,” refers to the deceptive outer shape of a crystal that has solidified within a rock crevice or other mold incongruous to its inner structure. An important part of the Levantine (or, as Spengler termed it, Magian) culture developed in such a way under Greek and Roman pressures; but then suddenly, with Mohammed, it broke free to evolve in its own style the civilization of Islam;Note 43 and in like manner the North European culture developed throughout its Gothic period under an overlay of both classical Greco-Roman and Levantine biblical forms, in each of which there was the idea of a single law for mankind, from which notion we are only now beginning to break free.

The biblical law was supposed to be of a supernatural order, received by special revelation from a God set apart from nature, who demanded absolute submission of the individual will. But in the classical portion of our dual heritage, too, there is equally the concept of a single normative moral law; a natural law, this time, however, discoverable by reason. Yet if there is any one thing that our modern archives of anthropology, history, physiology, and psychology prove, it is that there is no single human norm.

The British anatomist Sir Arthur Keith testified to the psychosomatic determination of this relativism some thirty-odd years ago. “Within the brain,” he wrote in a piece composed for what used to be called the General Reader, “there are some eighteen thousand million of microscopic living units or nerve cells. These units are grouped in myriads of battalions, and the battalions are linked together by a system of communication which in complexity has no parallel in any telephone network devised by man. Of the millions of nerve units in the brain not one is isolated. All are connected and take part in handling the ceaseless streams of messages which flow into the brain from eyes, ears, fingers, feet, limbs, and body.” And then he moved to his conclusion:

If nature cannot reproduce the same simple pattern in any two fingers, how much more impossible is it for her to reproduce the same pattern in any two brains, the organization of which is so inconceivably complex! Every child is bom with a certain balance of faculties, aptitudes, inclinations, and instinctive leanings. In no two is the balance alike, and each different brain has to deal with a different tide of experience. I marvel, then, not that one man should disagree with another concerning the ultimate realities of life, but that so many, in spite of the diversity of their inborn natures, should reach so large a measure of agreement.Note 44

Thus, as in the world without, of Einstein, so in the world within, of Keith, there is no point of absolute rest, no Rock of Ages on which a man of God might stand assured or a Prometheus be impaled. But this too was only something that in the arts and philosophies of post-Gothic Europe had already been recognized; for instance, in metaphysical terms, in the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860). This melancholy genius — touched, like the Buddha, by the spectacle of the world’s sorrow — was the first major philosopher of the West to recognize the relevance of Vedantic and Buddhistic thought to his own; yet in his doctrine of the metaphysical ground of the unique character of each and every human individual he stood worlds apart from the indifference of all Indian thought to individuation. The goal in India, whether in Hinduism, Buddhism, or Jainism, is to purge away individuality through insistence first upon the absolute laws of caste (dharma), and then upon the long-known, marked-out stages of the way (marga) toward indifference to the winds of time (nirvāṇa). The Buddha himself only renewed the timeless teaching of the Buddhas, and all Buddhas, cleansed of individuality, look alike. For Schopenhauer, on the other hand (though indeed in the end he saw the denial of the will-to-life as the highest spiritual goal), not caste or a social order but intelligent, responsible autonomy in the realization of character and in sympathy and well-doing was the criterion of moral worth, having as general guide the formula: “Hurt none; but, as far as possible, benefit all.”Note 45

For in Schopenhauer’s view, the species Homo sapiens represents the achievement of a stage in evolution beyond the meaning of the word “species” when applied to animals, since among men each individual is in himself, as it were, a species. “No animals,” he states, “exhibit individuality to any such remarkable degree. The higher types, it is true, show traces; yet even there, it is the character of the species that predominates and there is little individuality of physiognomy. Moreover, the farther down we go, the more does every trace of individual character disappear in the common character of the species, until, at last, only a general physiognomy remains.”Note 46

In the pictorial arts, Schopenhauer then observes, there is a distinction between the aims of those addressed to the beauty and grace of a species and those concerned to render the character of an individual. Animal sculpture and painting are of the former type; portraiture in sculpture and painting, of the latter. A midground is to be recognized in the rendition of the nude; for here — at least in the classical arts — the figure is regarded in terms of the beauty of its species, not the character of the individual. Where the individual appears, the figure is naked, not properly a “nude.”Note 47 However, the nakedness itself may be advanced to the status of portraiture if the address is to the character of the subject; for, as Schopenhauer sees, individuality extends to the entire embodiment.Note 48

And so we now note that in classical art the culminating achievement, the apogee, was the beautiful standing nude: a revelation physically of the ideal of the norm of the human species, in accord with the quest of Greek philosophy for the moral and spiritual norm. Whereas, in contrast, at the apogee of Renaissance and Baroque achievement the art of portraiture came to flower — in the canvases, for instance, of Titian, Rembrandt, Diirer, and Velazquez. Even the nudes in this period are portraits, and in the large historical canvases, such as Velazquez’s “Surrender of Breda” (in the Prado), portraiture again prevails. The epochs of history are read not as impersonal, anonymous effects of what are being called today the “winds of change” (as though history moved of itself), but as the accomplishments of specific individuals. And in the little as well as in the great affairs of life the accent remains on character — as in the paintings of Toulouse-Lautrec from the Moulin Rouge.

The masters of these works, then, are the prophets of the present dawn of the new age of our species, identifying that aspect of the wonder of the world most appropriate to our contemplation: a pantheon not of beasts or of superhuman celestials, not even of ideal human beings transfigured beyond themselves, but of actual individuals beheld by the eye that penetrates to the presences actually there.

Let me quote again from the philosopher:

As the general human form corresponds to our general human will, so the individual bodily form to the individually inflected will of the personal character; hence, it is in every part characteristic and full of expression.Note 49

The ultimate ground of the individual character, Schopenhauer states, in perfect accord with the finding of Sir Arthur Keith, lies beyond research, beyond analysis; it is in the body of the individual as it comes to birth. Hence, the circumstances of the environment in which the individual lives do not determine the character. They provide only the furtherances and hindrances of its temporal fulfillment, as do soil and rain the growth and flowering of seed. “The experiences and illuminations of childhood and early youth,” he writes in a sentence anticipating much that has been clinically confirmed by others since, “become in later life the types, standards and patterns of all subsequent knowledge and experience, or as it were, the categories according to which all later things are classified — not always consciously, however. And so it is that in our childhood years the foundation is laid of our later view of the world, and therewith as well of its superficiality or depth: it will be in later years unfolded and fulfilled, not essentially changed.”Note 50

The inborn, or, as Schopenhauer terms it, intelligible character is unfolded only gradually and imperfectly through circumstance; and what comes to view in this way he calls the empirical (experienced or observed) character. Our neighbors, through observation of this empirical character, often become more aware than ourselves of the intelligible, innate personality that is secretly shaping our life. We have to learn through experience what we are, want, and can do, and “until then,” declares Schopenhauer, “we are characterless, ignorant of ourselves, and have often to be thrown back onto our proper way by hard blows from without. When finally we shall have learned, however, we shall have gained what the world calls ‘character’ — which is to say, earned character. And this, in short, is neither more nor less than the fullest possible knowledge of our own individuality.”Note 51

A great portrait is, then, a revelation, through the “empirical,” of the “intelligible” character of a being whose ground is beyond our comprehension. The work is an icon, so to say, of a spirituality true to this earth and to its life, where it is in the creatures of this world that the Delectable Mountains of our Pilgrim’s Progress are discovered, and where the radiance of the City of God is recognized as Man. The arts of Shakespeare and Cervantes are revelations, texts and chapters, in this way, of the actual living mythology of our present developing humanity. And since the object of contemplation here is man — not man as species, or as representing some social class, typical situation, passion, or idea (as in Indian literature and art)Note 52 — but as that specific individual which he is, or was, and no other, it would appear that the pantheon, the gods, of this mythology must be its variously realized individuals, not as they may know or not know themselves, but as the canvas of art reveals them: each in himself (as in Schopenhauer’s phrase) “the entire World-as-Will in his own way.” The French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle (1861–1929) used to say to the pupils in his studio: “L’art fait ressortir les grandes lignes de la nature.” James Joyce in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man writes of “the whatness of a thing” as that “supreme quality of beauty” which is recognized when “you see that it is that thing which it is and no other thing.”Note 53 And we have also, again, Shakespeare’s figure of “the mirror.”

And just as in the past each civilization was the vehicle of its own mythology, developing in character as its myth became progressively interpreted, analyzed, and elucidated by its leading minds, so in this modern world — where the application of science to the fields of practical life has now dissolved all cultural horizons, so that no separate civilization can ever develop again — each individual is the center of a mythology of his own, of which his own intelligible character is the Incarnate God, so to say, whom his empirically questing consciousness is to find. The aphorism of Delphi, “Know thyself,” is the motto. And not Rome, not Mecca, not Jerusalem, Sinai, or Benares, but each and every “thou” on earth is the center of this world, in the sense of that formula just quoted from the twelfth-century Book of the Twenty-four Philosophers, of God as “an intelligible sphere, whose center is everywhere.”

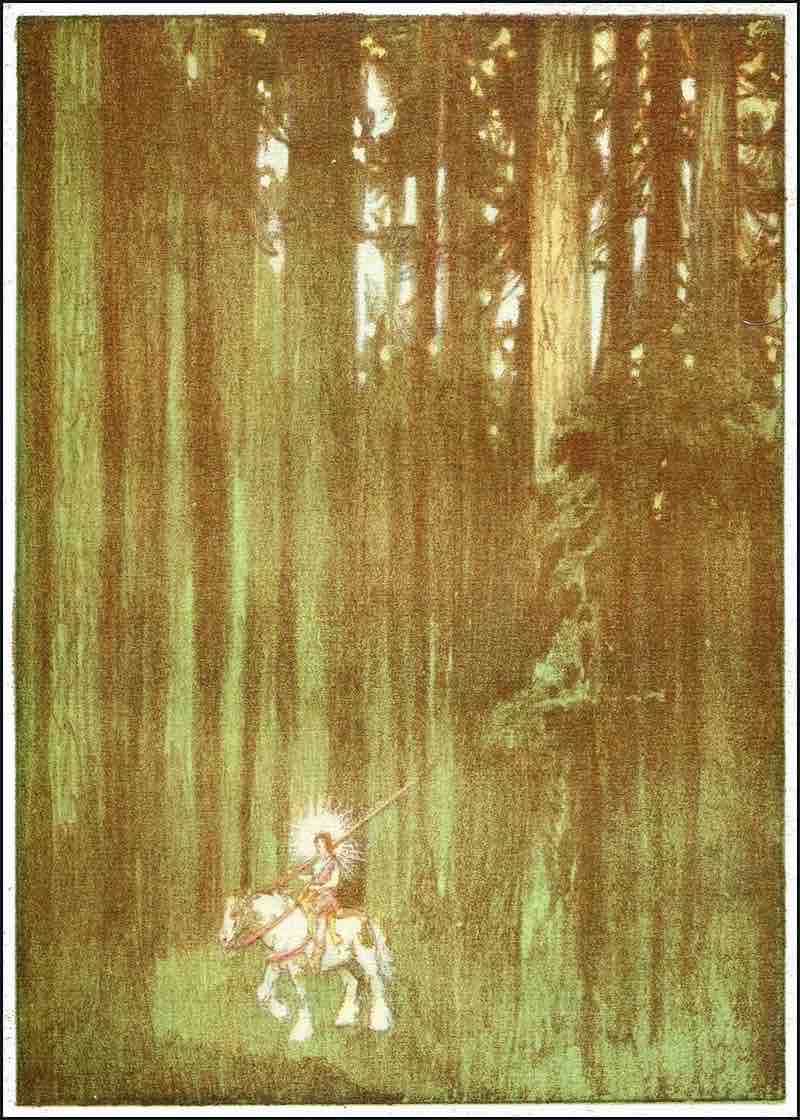

Figure 12.

"Where it was thickest" (print, United States, 1912)

Figure 12.

"Where it was thickest" (print, United States, 1912)

In the marvelous thirteenth-century legend called La Queste del Saint Graal, it is told that when the knights of the Round Table set forth, each on his own steed, in quest of the Holy Grail, they departed separately from the castle of King Arthur. “And now each one,” we are told, “went the way upon which he had decided, and they set out into the forest at one point and another, there where they saw it to be thickest” (la ou il la voient plus espesse); so that each, entering of his own volition, leaving behind the known good company and table of Arthur’s towered court, would experience the unknown pathless forest in his own heroic way.Note 54

Today the walls and towers of the culture-world that then were in the building are dissolving; and whereas heroes then could set forth of their own will from the known to the unknown, we today, willy-nilly, must enter the forest la ou nos la voions plus espesse: and, like it or not, the pathless way is the only way now before us.

But of course, on the other hand, for those who can still contrive to live within the fold of a traditional mythology of some kind, protection is still afforded against the dangers of an individual life; and for many the possibility of adhering in this way to established formulas is a birthright they rightly cherish, since it will contribute meaning and nobility to their unadventured lives, from birth to marriage and its duties and, with the gradual failure of powers, a peaceful passage of the last gate. For, as the psalmist sings, “Steadfast love surrounds him who trusts in the Lord” (Psalm 32:10); and to those for whom such protection seems a prospect worthy of all sacrifice, an orthodox mythology will afford both the patterns and the sentiments of a lifetime of good repute. However, by those to whom such living would be not life, but anticipated death, the circumvallating mountains that to others appear to be of stone are recognized as of the mist of dream, and precisely between their God and Devil, heaven and hell, white and black, the man of heart walks through. Out beyond those walls, in the uncharted forest night, where the terrible wind of God blows directly on the questing undefended soul, tangled ways may lead to madness. They may also lead, however, as one of the greatest poets of the Middle Ages tells, to “all those things that go to make heaven and earth.”

IV. Mountain Immortals

“I have undertaken a labor,” wrote the poet Gottfried von Strassburg, whose Tristan, composed about the year 1210, became the source and model of Wagner’s mighty work, “a labor out of love for the world and to comfort noble hearts: those that I hold dear, and the world to which my heart goes out. Not the common world do I mean of those who (as I have heard) cannot bear grief, and desire but to bathe in bliss. (May God then let them dwell in bliss!) Their world and manner of life my tale does not regard: its life and mine lie apart. Another world do I hold in mind, which bears together in one heart its bitter sweet, its dear grief, its heart’s delight and its pain of longing, dear life and sorrowful death, its dear death and sorrowful life. In this world let me have my world, to be damned with it, or to be saved.”Note 55

James Joyce, in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, sounded the same bold theme in the words of his twentieth-century Irish Catholic hero, Stephen Dedalus: “I do not fear to be alone. And I am not afraid to make a mistake, even a great mistake, a lifelong mistake, and perhaps as long as eternity too.”Note 56

It is amazing, really, to think that in our present world with all its sciences and machines, megalopolitan populations, penetrations of space and time, night life and revolutions, so different (it would seem) from the God-filled world of the Middle Ages, young people should still exist among us who are facing in their minds, seriously, the same adventure as thirteenth-century Gottfried: challenging hell. If one could think of the Western World for a moment in terms not of time but of space; not as changing in time, but as remaining in space, with the men of its various eras, each in his own environment, still there as contemporaries discoursing, one could perhaps pass from one to another in a trackless magical forest, or as in a garden of winding ways and little bridges. The utilization by Wagner of both the Tristan of Gottfried and the majestic Parzival of Gottfried’s leading contemporary, Wolfram von Eschenbach, would suggest perhaps a trail; so also the line, very strong indeed, from Gottfried to James Joyce. Then again there is the coincidence (this time in two contemporaries) of James Joyce (1882–1941) and Thomas Mann (1875–1955), proceeding each along his own path, ignoring the other’s work, yet marking, in measured pace, the same stages, date by date; as follows:

First, in the Buddenbrooks (1902) and “Tonio Kröger” (1903) of Thomas Mann, Stephen Hero (1903) and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) of James Joyce: accounts of the separation of a youth from the social nexus of his birth to strive to realize a personal destiny, the one moving from the Protestant side, the other from the Roman Catholic, yet each resolving his issue through a moment of inspired insight (the inspiring object, in each case, being the figure of a girl), and the definition, then, of an aesthetic theory and decision.

Next, in Ulysses (1922) and The Magic Mountain (1924), two accounts of quests through all the mixed conditions of a modern civilization for an informing principle substantial to existence, the episodes being rendered in the manner of the naturalistic novel, yet in both works opening backward to reveal mythological analogies: in Joyce’s case, largely by way of Homer, Yeats, Blake, Vico, Dante, and the Roman Catholic Mass, with many echoes more; and in Mann’s, by way of Goethe’s Faust, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, the Venus Mountain of Wagner, and hermetic alchemical lore.

Then, in Finnegans Wake (1939) and the tetralogy of Joseph and His Brothers (1933–1943), both novelists dropped completely into the well and seas of myth, so that, whereas in the earlier great novels the mythological themes had resounded as memories and echoes, here mythology itself became the text, rendering visions of the mystery of life as different from each other as the brawl at an Irish wake and a conducted visit to a museum, yet, for all that, of essentially the same stuff. And, as in the Domitilla Catacomb the composed syncretic imagery broke the hold upon the mind of the ethnic orders, opening back, beyond, and within, to their source in elementary ideas, so in these really mighty mythic novels (the greatest, without question, yet produced in our twentieth century), the learnedly structured syncrasies conjure, as it were from the infinite resources of the source abyss of all history itself, intimations in unending abundance of the wonder of one’s own life as Man.

In the earlier volumes of this survey the mythologies treated are largely of the common world of those who, in the poet Gottfried’s words, “can bear no grief and desire but to bathe in bliss”: the mythologies, that is to say, of the received religions, great and small. In the present work, on the other hand, I accept the idea proposed by Schopenhauer and confirmed by Sir Arthur Keith, the intention being to regard each of the creative masters of this dawning day and civilization of the individual as absolutely singular, each a species unique in himself. He will have arrived in this world in one place or another, at one time or another, to unfold, in the conditions of his time and place, the autonomy of his nature. And in youth, though early imprinted with one authorized brand or another of the Western religious heritage, in one or another of its known historic states of disintegration, he will have conceived the idea of thinking for himself, peering through his own eyes, heeding the compass of his own heart. Hence the works of the really great of this new age do not and cannot combine in a unified tradition to which followers then can adhere, but are individual and various. They are the works of individuals and, as such, will stand as models for other individuals: not coercive, but evocative. Wagner following Gottfried, Wagner following Wolfram, Wagner following Schopenhauer, follows, finally, no one but himself. Scholars, of course, have nevertheless traced, described, and taught school around traditions; and for scholars as a race such work affords a career. However, it has nothing to do with creative life and less than nothing with what I am here calling creative myth, which springs from the unpredictable, unprecedented experience-inillumination of an object by a subject, and the labor, then, of achieving communication of the effect. It is in this second, altogether secondary, technical phase of creative art, communication, that the general treasury, the dictionary so to say, of the world’s infinitely rich heritage of symbols, images, myth motives, and hero deeds, may be called upon — either consciously, as by Joyce and Mann, or unconsciously, as in dream — to render the message. Or on the other hand, local, current, utterly novel themes and images may be used — as again in Joyce and Mann.

But I shall not anticipate here the adventures in these pages beyond pointing out that we shall dwell first upon the mystery of that moment of aesthetic arrest when the possibility of a life in adventure is opened to the mind; review, next, a catalogue of the vehicles of communication available to the Western artist for the celebration of his rapture; and follow, finally, the courses of fulfillment of a certain number of masters, dealing all with that same rich continuum of themes from our deepest, darkest past that has come to boil most recently in the vessel of Finnegans Wake. Further, for the giving of heart to those who have entered into other works with hope, only to find in the end dust and ashes, the assurance can also be given that, according to the evidence of these pages, it appears that the soul’s release from the matrix of inherited social bondages can actually be attained and, in fact, has already been attained many times: specifically, by those giants of creative thought who, though few in the world on any given day, are in the long course of the centuries of mankind as numerous as mountains on the whole earth, and are, in fact, the great company from whose grace the rest of men derive whatever spiritual strength or virtue we may claim.

Societies throughout history have mistrusted and suppressed these towering spirits. Even the noble city of Athens condemned Socrates to death, and Aristotle, in the end, had to flee its indignation. As Nietzsche could say from experience: “The aim of institutions — whether scientific, artistic, political, or religious — never is to produce and foster exceptional examples; institutions are concerned, rather, for the usual, the normal, the mediocre.” And yet, as Nietzsche goes on to affirm, “The goal of mankind is not to be seen in the realization of some terminal state of perfection, but is present in its noblest exemplars.”

That the Great Man should be able to appear and dwell among you again, again, and again [he wrote], that is the sense of all your efforts here on earth. That there should ever and again be men among you able to elevate you to your heights: that is the prize for which you strive. For it is only through the occasional coming to light of such human beings that your own existence can be justified.… And if you are not yourself a great exception, well then be a small one at least! and so you will foster on earth that holy fire from which genius may arise.Note 57