Chapter 7

The Crucified

I. The Turning Wheel of Terror-Joy

The origins of Arthurian romance were Celtic.Note 1 However, beneath and behind the Celtic stratum lay the widely disseminated neolithic and Bronze Age mythic and ritual heritage, which had originated in great stages, c. 7500–2500 b.c., in the earliest agricultural and city-state communities of the nuclear Near East and represents finally the fundamental spiritual heritage of all higher civilization whatsoever.Note 2 Its diffusion from the matrix — the mythogenetic zone, as I have termed it — where it first took form as a profoundly inspired intuition of an all-governing cosmic order, carried its heavily charged imagery to every quarter of the cultivated earth. Hence the Celtic myths of the Great Goddess and her consort dwelling in the fairy hills, Land under Waves, Land of Youth, or Isle of Women (Arthurian Avalon), participate in a world tradition, of which they represent the remotest northwestward extension.

Moreover, the later, Iron Age features of the popular Celtic legends of the chariot-warriors of King Conchobar and giant-men of Finn Mac Cumhaill likewise are of the widest distribution. Stemming from a second mythogenetic zone, the broad grasslands of Eastern Europe and Southwest Asia, the matrix of the Aryan races, they belong to the brilliant hunting-herding-fighting complex of male-oriented patriarchal legendry that was carried by tough, warloving, widely ranging nomads — masters of the horse and inventors of the war chariot — westward as far as to Ireland, eastward even to China, and southward to Italy, Greece, Anatolia, India, and Egypt; so that the chariots, battle hymns, and battle-ready gods of the Vedas, Homer, and the Irish epics are akin, as variant developments of this single Aryan, Indo-Celtic, Indo-Germanic, or, as it is now commonly called, Indo-European complex.

Furthermore, the interactions of the conquering gods and heroes of this later, patriarchal mythology, on one hand, and the local, earth-bound, earth-fructifying goddesses and their consorts — guardians of the order of mother-right — on the other, exhibit analogous features wherever the two contrary systems came together, clashed, and finally, perforce, amalgamated. In some areas — India and Ireland, for example — the point of view and mythic order of the earlier Bronze Age civilization held its own, absorbed the other, and finally became dominant in the combination, whereas in others — most notably in Continental Europe, the classic land of the paleolithic hunt, to which the art of the great caves of Altamira, Lascaux, Trois Frères, Tuc d’Audoubert, and the rest, bears a testimony of some thirty thousand years — the moral and spiritual order represented by the Aryan battle-gods prevailed. Nevertheless, in the main, like features are evident everywhere, here stressing one, there the other side of the interaction. And as we have seen, it was out of one such arena of mythogenic superfetation — the well-named “fertile crescent,” again, of the nuclear Near East — that the late classical, Hellenistic, and Roman mystery cults developed, of which the Christian sect was a popular, nonesoteric, politically manageable, state-supported variant, wherein symbols that in others were read in a mystic, anagogical way, proper to symbols, were reduced to a literal sense and referred to supposed or actual historical events. Together, official Christianity and a number of the mystic traditions (Orphic and Mithraic, Gnostic, Manichaean, and so forth) were carried by Roman arms and colonization to northern Europe, and there, following the victories of Constantine (324 a.d.)and promulgation of the Theodosian Code (438 a.d.) — which banned in the Roman Empire all beliefs and cults save the Christian — the mysteries, like a secret stream, went underground, while the same symbols that were there being employed in rites of initiation as anagogic metaphors were enforced officially, above ground, as reports of hard historic fact.

In that bold and learned study of the legend of the Grail to which T. S. Eliot refers in his footnotes to The Waste Land, Miss Jessie L. Weston’s From Ritual to Romance (published 1920), it is suggested that the rites of a mystery cult of this subterranean kind may lie at the root of the Grail tradition: some such esoteric sect as we have seen indicated in the sacramental bowls of Figures 5 and 6, 18 and 19.

C’est del Graal dont nus ne doit

Le secret dire ne conter.…

So states the so-called “Elucidation” attached by some unknown redactor to Chretien de Troyes’ unfinished Perceval:Note 3 “The tale is of the Grail, of which none may speak or recount the secret.” But as Miss Weston reminds us, the rites of the Christian Church were never secret; nor are the fertility rites of the primitive nature cults. Taken together with the general atmosphere of wonder, mystery, quest, and initiation that pervades the Grail tradition, these two lines would therefore seem to indicate a relationship of some kind between the enigmatic symbols displayed in the Castle of the Grail and the rites of the late classical mystery sects. In these latter, we have seen, the earlier field-cult symbols of vegetal fertility were turned to the ends of inward spiritual fructification, wakening, and rebirth. Furthermore, as we have also seen, the native Celto-Germanic gods of northern Europe were identified in Roman times with their Greco-Roman counterparts, and so made available for service in local extensions of the classical mystery tradition. The Irish sea-god Manannan Mac Lir was the northern, Celtic analogue of Neptune (Greek Poseidon), who in turn — as disclosed at the culminating moment of the brothel scene of Ulysses — was the Occidental counterpart of Śiva. In the Hellenistic age of Alexander’s “Marriage of East and West,” such Occidental-Oriental equivalencies were already recognized both in mythological and in philosophical contexts; so that with the later Roman carriage of the mysteries and philosophies of the Hellenized Near East to France and Britain, the secrets of the Orient came too. And a knowledge of their psychologically effective mysteries, in alchemy, the Grail tradition, Rosicrucianism, Masonry, and so on, has come down, even to the present hour.

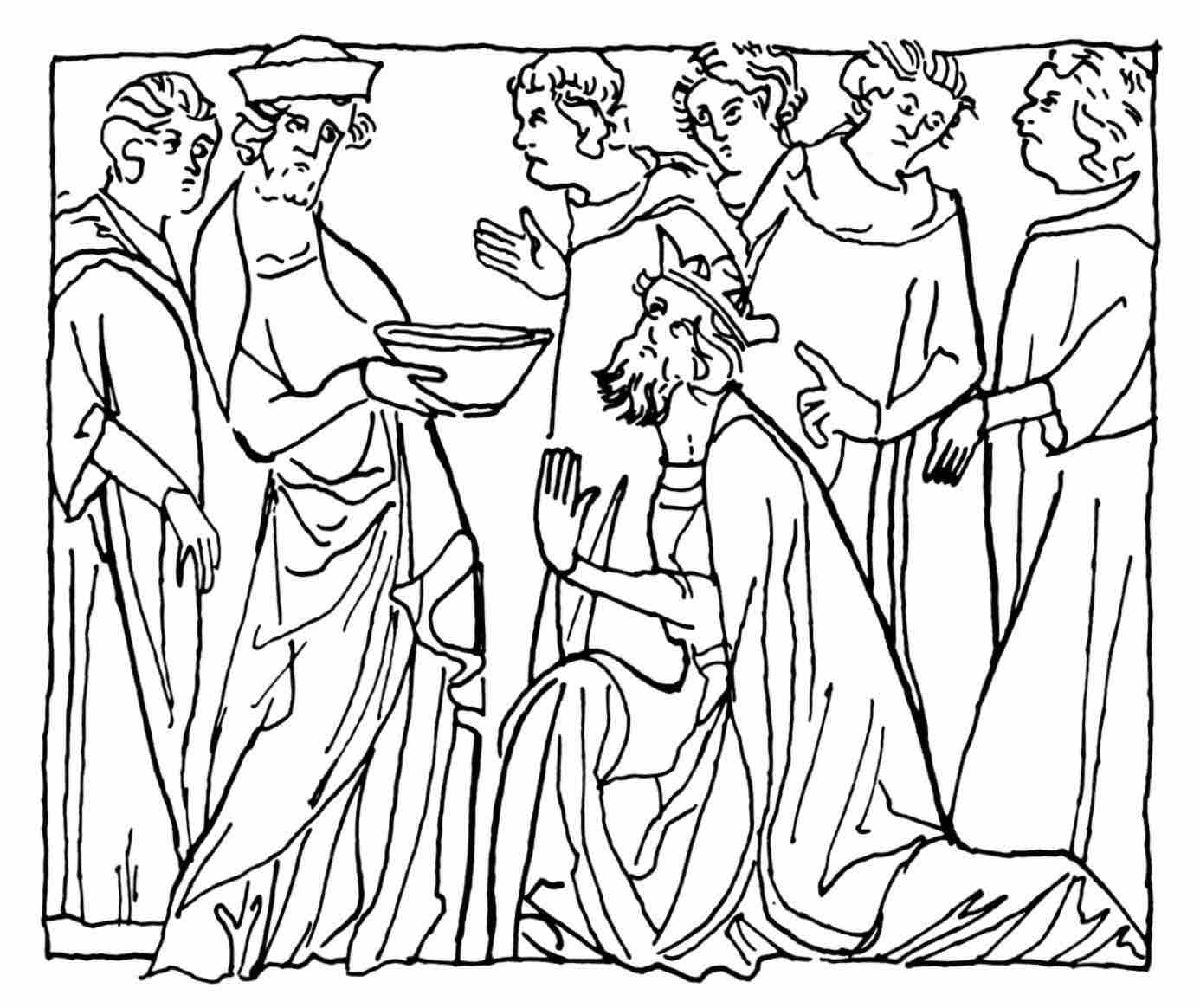

Figure

63. Bishop Josephe Confers the Grail on King Alain

Figure 63 is from an illuminated manuscript (c. 1300 a.d.) of a late prose version of the Grail romance known as the Estoire del Saint Graal (date c. 1215–1230), in which the Grail hero is no longer Perceval but the perfectly chaste Galahad, and the holy vessel itself is identified with that from which Christ, at the Last Supper, served the Apostles. This Grail, or dish, was supposed to have been brought to Britain most marvelously, together with the lance that pierced Christ’s side, by the chaste son, Josephes, of that good man Joseph of Arimathea, in whose rock-cut tomb the Savior had been buried.Note 4 The illustration is of the scene, late in the romance, where Josephe confers the Grail upon the king who is to succeed him as its keeper, and who will be known as the rich fisher when he will have miraculously served a large company with a single fish he is now to catch. Note the form of the vessel. A comparison with the bowls of Figures 5 and 6, 18 and 19, and then 33, which last is of the same date as this illumination, will of itself tell a story of the Grail — in silence — better than words.

Let us again regard, therefore, in Figure 5, at the opening of the round of initiation, the mystagogue Orpheus, the Fisherman, with his pole, his net, and caught fish. Miss Weston had already recognized a relationship of the figure of the Fisher King not only to the Christian “fisher of men” theme but also to the earlier pagan mystery-cult symbologies of the fish, the Friday fish meal, and the fisher god;Note 5 and Professor William A. Nitze of the University of California has carried her suggestion a step further by pointing to a sea-god of Celtic Britain whose name, Nodens, actually means “Fisher.” In the Irish epics he appears as King Nuadu of the Silver Hand, of the people of the fairy hills, who, having lost an arm in combat, replaced it with an arm of silver, and so, like the Fisher of the Grail Castle, was a maimed king.Note 6

Now silver is the metal of the moon, as gold, of the sun; and the reader has surely thought by now of the symbolic association, already frequently alluded to in these volumes, of the sea-god and the moon, that celestial cup of the liquor of immortality, which is ever emptied and refilled. When personified as the tide-controller himself, the moon is lame, lopsided; and accordingly, as noticed in Oriental Mythology, both the Chinese flood hero Yii and the biblical Noah became lame, according to folk legend, in the course of their water labors: the latter when struck by the paw of the lion (the sun beast) in his ark, and the former from a sickness that made him shrivel in half his body, like the moon.Note 7 This celestial orb, like the soul and destiny of man, is both light and dark, of both the spirit and the flesh, bound to the orbit of this earth and, like the serpent of Figures 18, 20, and 32, ever circling from the light of the empyrean to the dark of the abyss.

But as a cup the moon is the inexhaustible vessel of immortal food and drink of the lord of the tides of life — and such an inexhaustible vessel is also the Grail. Moreover, the moon may be viewed as a head (“the Man in the Moon”), and in the Welsh version of the Grail romance, Peredur, what the hero is shown at the Castle of the Grail is neither a cup nor a bowl but a man’s head, carried on a large salver by two maidens.Note 8 And finally, as Miss Weston remarksNote 9 and every Wagner devotee knows, there are in the Grail Castle not one but two disabled kings: the Maimed or Fisher King, in the foreground, suffering terribly from his wound, and another king, in extreme old age, in a room unseen, into which the Grail is carried and from which it again returns. These two, in lunar imagery, would correspond to the dark, the old moon, into which the light goes and from which in three days it returns, and the young or visible moon, which is successively young, full, and declining. In Wolfram’s words:

*Compare T.S. Eliot’s line in The Waste Land: “Here one can neither lie nor stand nor sit” (see Experience and Authority).

The king can neither ride nor walk, neither lie nor stand:he leans but cannot sit, and sighs, remembering why.* At the time of the change of the moon his pain is great. There is a lake by the name Brumbane: they bring him there for the fresh air for his painful open wound and he calls that his hunting day. But what he can catch there with his wound so painful would never provision his home. It is from this the legend came that he was a fisher.Note 10

Figure

64. The Gundestrupp Bowl; Jutland

Figure

65. The God Cernunnos; Gundestrupp Bowl detail

Figure 64 is a ritual bowl of silver, the metal of the moon. It was found at Gundestrupp, Jutland, in a bog. On the outside are a number of deities unidentified, and within, a series of strange scenes. Figure 65, one of these, shows the Celtic underworld god Cernunnos, whom the Romans identified with Pluto-Hades. Figures 33 and 30 have already been discussed in relation to this complex. Cernunnos, Manannan Mac Lir, Poseidon, Hades, Dumuzi-Tammuz, and Satan are alternate names of this same lord of the abyss, who is also the god in Figure 5 at Station l0 (See Experience and Authority.). In Oriental Mythology, Figure 20, is a horned image of this Celtic god, seated cross-legged on a low dais and holding on his left arm a cornucopia-like bag, from which grain pours as from an inexhaustible source. Before him stand a bull and stag, feeding on the downpouring grain (as here, a bull and stag at the god’s right), while at either hand stands a classical divinity: Apollo at his right, Hermes-Mercury at his left, the lords respectively of the light world and the road to the abyss; while above is the emblem of a large rat, which in India is the animal of Ganesha, the god of thresholds: and in my discussion of this altarpiece I have remarked its resemblance to the numerous images in India and the Far East of a seated Buddha between two standing Bodhisattvas; also, greatly earlier, from the Indus Valley period, c. 2500–1500 b.c., certain figures on stamp seals in seated yogic postures, among which there is one seated on a low dais flanked by worshiping serpent princes (Oriental Mythology, Figure 29), and another, again on a low dais, wearing a large headpiece of buffalo horns with a high crown between (Oriental Mythology, Figure 18), suggesting a trefoil or trident, the symbol of Śiva, Poseidon, Satan. Two gazelles stand before this dais in the place exactly of the beasts before Cemunnos; also, of the two deer that frequently appear in Buddhist art before the seat of the Buddha preaching his first sermon (“The First Turning of the Wheel of the Law”) in the Deer Park of Benares. Around the Indus figure, furthermore, stand four assorted beasts, which again suggest Śiva in his character as “Lord of Beasts” (pasu-pati). Compare the Orpheus-Christ of Figure 3.

It is next to certain that all these figures are related, not only in form, but also in sense, deriving ultimately from a common background in the old Bronze Age culture matrix. The reader has perhaps already recalled in this connection our discussion in Oriental Mythology of Śiva and his Śakti in “The Isle of Gems” (Oriental Mythology, Figure 21), where the male divinity appears in two aspects simultaneously: one turned away from his goddess spouse in the aspect known as Śava, “The Corpse,” deus absconditus, the inconceivable, unmanifest, transcendent aspect of the ground of being; and the other in connubium with her as Śiva-Śakti, the lord and lady of life. I there compared this dual view of the one mystery to the two aspects of Egyptian Pharaonic power symbolized as early as c. 2850 b.c. in (a) the dead Pharaoh in his tomb, identified with Osiris in the underworld, lord of the dead, and (b) the reigning Pharaoh on his throne, as Horns, son of the dead Osiris, lord of the living. Comparably, in Mahāyāna Buddhism the mystery of enlightenment is personified in two contrasting forms: (a) the Buddha, the departed one, represented as a monk, dead to the world, and (b) the Bodhisattva, a noble, princely being wearing a richly jeweled tiara, symbolic of the world-regarding, compassionate aspect of illuminated consciousness.Note 11

When he teaches, the Bodhisattva assumes the form of his auditors. He is free of passion, free also of thought. He is benevolence without purpose; he is merit, put to the service of all beings. When shown with many arms, many hands, many heads, gazing and serving in all directions, he carries in his hands skulls filled with flowers (compare in Figure 3 the plants growing from the rams’ heads), also tridents encircled with serpents (compare the symbols of Hermes and Poseidon). From his fingers flow rivers of ambrosia, which cool the hells and feed the hungry ghosts. In the palm of each hand is an eye — regarding the world and with sympathy participant in its pain: each eye a wound, pierced with sorrow, as the wounds in the palms of Christ the Savior on the Cross. He is called the “god of the present,” “he who bears the world,” and as such bears and absorbs in his infinite person the sorrows of the world.Note 12

There is an astonishing fable in the Hindu Pañcatantra, where an awesome reflection of the pain-bearing aspect of the Bodhisattva principle appears in a strange adventure that throws light on the meaning and background of the Maimed King of the Grail. It is of four friends, Brahmins, stricken with poverty, who determined to try to get rich. They set forth together and in the Avanti country met a magician named Terror-Joy, whom they asked for assistance. He gave to each a magic quill, with instructions to go north, to the northern slope of the Himalayas [i.e., to Buddhist Tibet]; and wherever a quill dropped, the owner would find treasure. The leader’s quill dropped first, and they found the soil to be all copper. So he said, “Look here! Take all you want!” But the others decided to go on. The first took his copper and turned back. Next the second leader’s quill dropped; he dug, found silver, and was the second to return. The next quill yielded gold. “Don’t you see the point?” said the fourth. “First copper, then silver, then gold. Beyond, there will surely be gems.” And he went on.

And so this other went on alone. His limbs were scorched by the rays of the summer sun and his thoughts were confused by thirst as he wandered to and fro over the trails in the land of the fairies. At last, on a whirling platform, he saw a man with blood dripping down his body; for a wheel was whirling on his head. Then he made haste and said: “Sir, why do you stand thus with a wheel whirling on your head? In any case, tell me if there is water anywhere. I am mad with thirst.”

The moment the Brahmin said this, the wheel left the other’s head and settled on his own. “My very dear sir,” said he, “what is the meaning of this?” “In the very same way,” replied the other, “it settled on my head.” “But,” said the Brahmin, “when will it go away? It hurts terribly.”

And the fellow said: “When someone who holds in his hand a magic quill, such as you had, arrives and speaks as you did, then it will settle on his head.” “Well,” said the Brahmin, “how long have you been here?” The other asked: “Who is king in the world at present?” And on hearing the answer, “King Vinabatsa,” he said: “When Rāma was king, I was poverty-stricken, procured a magic quill, and came here, just like you. And I saw another man with a wheel on his head and put a question to him. The moment I asked a question (just like you) the wheel left his head and settled on mine. But I cannot reckon the centuries.”

Then the wheel-bearer asked: “My dear sir, how, pray, did you get food while standing thus?” “My dear sir,” said the fellow, “the god of wealth [Kubera = Hades-Pluto], fearful lest his treasures be stolen, prepared this terror, so that no magician might come so far. And if any should succeed in coming, he was to be freed from hunger and thirst, preserved from decrepitude and death, and was merely to endure this torture. So now permit me to say farewell. You have set me free from a sizable misery. Now I am going home.” And he went.Note 13

The fable, as here retold in this frankly worldly work, devoted not to sainthood but to the art of getting on, is presented as a warning to all of the danger of excessive greed; however, as Theodor Benfey was the first to show (already in 1859), this was originally a Mahāyāna Buddhist legend treating of the path to Bodhisattvahood.Note 14 The key to its hidden religious import — which is just the opposite to that of the secular fable — is betrayed in the name of the magician, Terror-Joy (Bhairavānanda), “the exhilaration or bliss (ānanda) of what is awesome or terrible (bhai-rava)” — which is an oxymoron fiercer than Gottfried’s “bittersweet,” yet of the same sense.

“Terror,” Bhairava, is the cult-name of Śiva in his most terrific aspect, as the terrible destroyer of illusion, consort of the bloodcurdling, blood-consuming black goddess Kali. Divinities of this furious kind, representing the dark, brutal, implacable aspects of nature and of human nature, befit people who are themselves dark, brutal, and passionate of heart. They are, in fact, the only gods that people of such temperament can truly recognize, credit, and respect. Hence — since the Bodhisattva, as we have said, assumes the form of his auditors when he teaches — the harsh, brutal traits of these fierce Hindu divinities and their equally terrible rites were taken over by the later Mahāyāna as means for the conversion of passionate men through the medium of their own passions into sages of a truly terrible wisdom: knowers through an experience (by reflection of the force of their own life zeal) of the monstrous thing that is life, which lives, in each of its beings, on the death and pain of all the rest.

The magician of this paradoxical fable gave instruction to those who came to him in such a way that each should receive a reward appropriate to his nature. Hence, it was only the one whose greed was truly boundless who achieved the boon of bhairavānanda: that experience beyond the bounds of knowledge, purpose, and value, which is learned with a terrible joy “at the still point of this turning world” — in the way of William Blake’s Proverb of Hell: “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom,”Note 15 or in the way of Christ crucified; Atlas bearing the world on his back; Loki tortured by the venom of a serpent continually dropping on his head; or Prometheus pinned to a crag of Caucasus. One may think also of Job.

The wheel of dharma (carved stone, India, thirteenth

century)The wheel in Buddhist iconography is known as the

“Wheel of the Law” (dharmacakra). It is symbolic of the

reign of the World Monarch, the so-called “Turner of the Wheel”

(cakra-vartin), but also of the teaching of the Buddha, the

World Savior, who in his first sermon, in the Deer Park of Benares,

set the Wheel of the Law in motion. The World Monarch is to reign

in the spirit of that law. And the wheel is to be known as of two

sides: in its commonly manifest aspect, as the wheel of sorrows of

this everlasting round of births and rebirths, disease, old age,

and death (all life is sorrowful); but also in the deeper, darker,

yet more luminous revelation of the Mahāyāna doctrine of the “Great

Delight” (Mahāsukha): the realization of this world, just as

it is, as the Golden Lotus World; of saṁsāra, the painful

wheel of rebirth, and nirvāṇa, the still state at the center

of the wheel, as the same — for those with the courage and strength

of will to endure the terrible cutting edge (Compare in

Occidental Mythology, Figure 24, the Mithraic-Zoroastrian

figure and mystery of Zervan Akarana, “Boundless Time.”).

And should the reader wish to know how such an experience of the cutting edge can be endured in this world, let him turn to the ambrosial book, Man’s Search for Meaning, of Dr. Viktor E. Frankl (now of the University of Vienna), who, for endless days in the Nazi prison camps, bore on his head the whole weight of that wheel.Note 16

II. The Maimed Fisher King

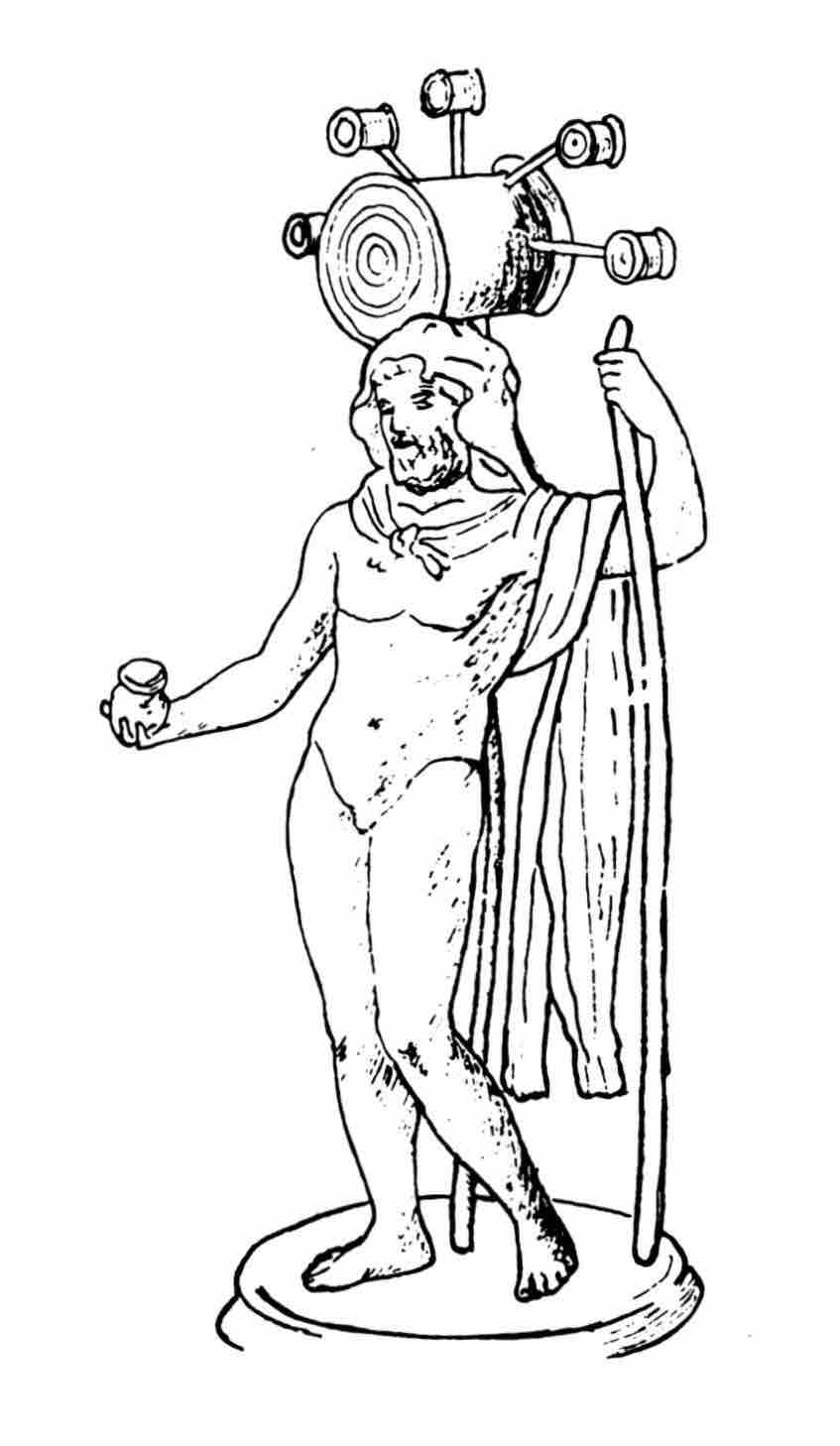

Figure

66. The God of the Wheel; France, Gallo-Roman Period

Figure

67. The God Sucellos; France, Gallo-Roman Period

In the mythologies of the Celts, behind the Grail romance and figure of the Fisher King, the idea of a revolving wheel, platform, or castle is an essential feature. Figure 66 is of a Gallo-Roman statue found at Chatelet, Haute-Marne. It shows a bearded Celtic god with a wheel; and like the Buddhist “wheel of being,” this also has six spokes.* The god has slung over his right shoulder his supply of thunderbolts and elevates in his right hand the cornucopia of ambrosia that he holds for his devotees. Figure 67 shows another of these early Gallic divinities, Sucellos, who as here depicted is a manifestation of the power of his own world-creating, world-annihilating hammer (Sanskrit vajra, “diamond bolt,” the highest Hindu-Buddhist symbol of illumination, by which the world-illusion is destroyed and which itself is indestructible). The five hammers fixed to this large bolt suggest the energies of the five elements of which (in the Indian view) the world and its creatures are composed: ether, air, fire, water, and earth. The circles on the hammer suggest both the Buddhist Wheel of the Law and the symbolic cosmic circles on the Orphic serpent bowl (Figure 18). And in the right hand of this god — whom the Romans identified with Pluto — there is again the ambrosial cup.

Now the Irish sea-god Manannan had a vessel of this kind, of inexhaustible ambrosia; so also his Welsh counterpart, Bran the Blessed, son of Llyr, known also as Manawyddan, whose dwelling in the Land under Waves was called Annwfn, “the abyss,” but also Caer Sidi, “the revolving castle.”Note 17 And all around that whirling castle, difficult to enter, flow the ocean streams. A t its festive board the meat is served of immortal swine killed every day, which come alive the next, and this delicious fare, washed down with an immortal ale, gives immortality to all guests. Moreover there is in that land an abundant well, sweeter than white wine: hazel trees of knowledge drop crimson nuts into its waters, which are eaten by the salmon there; and the flesh of those fish gives omniscience. Now that Elysium with its castle and hospitable host is coextensive with the world, only hidden in mist; hence may appear anywhere to voyagers and as strangely disappear — like the Castle of the Grail. But there have also been places where it has been found to be more present; as on the summit of Slieve Mish, County Kerry, where there would appear, from time to time, the whirling castle of a shape-shifter named Curoi, who possessed an ambrosial caldron, stolen from a king of the fairy hills along with the latter’s daughter and three cows — all of which treasures he lost in turn, however, to the greatest trickster of all, Cuchullin (For Cuchullin, see Occidental Mythology.).

It is a moot question as to whether the obvious relationship of the Pañcatantra fable, in motifs and general sense, to the Grail Castle adventure is to be attributed mainly to remote, very early connections — say in Gallo-Roman times — or, more closely, to the period of the crusades; for as Theodor Benfey’s study of the Pañcatantra showed, over a century ago,Note 18 the passage of literary matter in the Middle Ages from India to Europe was considerable. As already remarked,* an Arabic translation of the Sanskrit Pañcatantra, made in the eighth century, was carried into Syriac in the tenth, Greek in the eleventh, old Spanish, Hebrew, and Latin in the middle and late thirteenth. Benfey himself remarked, furthermore, that an independent version of the fable of the four treasureseekers itself appears in the Grimm collection (Tale Number 54),Note 19 and that variants have been discovered since in every language and even dialect of Europe.Note 20 However, the all-important Wheel and Question motifs were dropped from these European versions, where the fourth seeker, after long wandering, comes only to a tall tree (the axis mundi) under which he rests, and when he wishes for a meal, a table appears set with a feast — after which the tale goes on with episodes from a totally different source.

The image of a spoked wheel symbolic of the turning world is attested for India already c. 700 b.c. in the Chandogya and Bṛhadāraṇya Upaniṣads: “Even as the spokes of a wheel are held fast in the hub, so is all this on prana, the life-breath.”Note 21 “As spokes are held fast by the hub and felly of a wheel, so are all beings, all gods, all worlds, all breathing things, all of these selves, held fast in ātman, the Self.”Note 22 And in the later Praśna Upaniṣad, where the immanent ground is personified as that mythic “Person” (puruṣa) of whose dismembered body the universe is made (Compare, Primitive Mythology, Oriental Mythology, Occidental Mythology.), we read: “He in whom all these parts are well fixed, like spokes in the hub of a wheel: him, recognize as the Person to be known — that death may not afflict you.”Note 23

Clearly the authors of these passages were familiar with the spoked wheel of the Aryan war chariot, which first appeared in the world in the early second millennium b.c. The figure dates, therefore, from the Vedic age, and cannot have appeared before that, or among people to whom the chariot was unknown. A very much earlier form, however, long antedating the invention even of the old Sumerian solid wheel (c. 3500 b.c.), was the almost universally known swastika, of which we have at least one example from the late paleolithic period, as early, perhaps, as c. 18,000 b.c.Note 24 In the beautifully painted ceramic wares of the high neolithic of Iran (Samarra ware, c. 4500 b.c.), this same sign is a conspicuous, even dominant, motif; and, as shown in Primitive Mythology, it was apparently from there that it was diffused to well nigh every corner of the earth.Note 25

Figure

68. Ixion; Etruscan bronze mirror, 4th century b.c.

From what we know of the temper of early cultures, it is safe to assume that the myths, rites, and philosophies first associated with these symbols were rather positive than negative in their address to the pains and pleasures of existence. However, in the period of Pythagoras in Greece (c. 582–500? b.c.) and the Buddha in India (563–483 b.c.), there occurred what I have called the Great Reversal.Note 26 Life became known as a fiery vortex of delusion, desire, violence, and death, a burning waste. “All things are on fire,” taught the Buddha in his sermon at Gaya,Note 27 and in Greece the Orphic saying ”Soma sema: The body is a tomb” gained currency at this time, while in both domains the doctrine of reincarnation, the binding of the soul forever to this meaningless round of pain, only added urgency to the quest for some means of release. In the Buddha’s teaching, the image of the turning spoked wheel, which in the earlier period had been symbolic of the world’s glory, thus became a sign, on one hand, of the wheeling round of sorrow, and, on the other, release in the sunlike doctrine of illumination. And in the classical world the turning spoked wheel appeared also at this time as an emblem rather of life’s defeat and pain than of victory and exhilaration in the image and myth of Ixion (Figure 68), bound by Zeus to a blazing wheel of eight spokes, to be sent whirling for all time through the air.

As the king of a late Bronze Age people of Thessaly, the Lapithai, Ixion had been a god-king, symbolic thus of that cosmic Person who in the Praśna quotation is celebrated as that one in whom all parts of the world are made fast, like spokes in the hub of a wheel; and he is here being punished by Zeus for two crimes, the first, of violence (the murder of his father-in-law), and the second, of lust (an attempt to ravish the goddess H era): i.e., the same two compulsions of desire and aggression recognized in Hindu and Buddhist thought (as well as in modern depth psychology) as the creative powers of the world illusion — which hold the world together and were overcome by the Buddha in his victory over the great lord of life named Lust and Death (kāma-māra), beneath the Bodhi-tree, at the hub of the wheel of the world (the axis mundi).Note 28

The legend of Ixion is cited by Pindar (522–448? b.c.) in a victory ode to the winner of a chariot race.Note 29 Five centuries later Virgil (70–19 b.c.) refers to it in the Aeneid,Note 30 by which time, however, the scene of the suffering has been transferred from the air to the underworld, where it is placed also by Ovid (43 b.c.–17 ad) in the Metamorphoses.Note 31 And down there, together with Ixion, are a number of other tortured characters, all symbolic, one way or another, of the agony of life: Tityos, with his vitals being torn forever by a vulture; Tantalus, tortured with thirst, teased by a water he cannot reach; and Sisyphus, shoving his huge boulder up a hill, down which it is again to roll — each to be tortured thus forever.

In the classic, popular view of these pains, they are punishments for crimes; however, as the existentialist Albert Camus, in his “Essay on the Absurd,” The Myth of Sisyphus, remarks: such figures are figures of life. The unilluminated common man lives normally in hope: the belief that his labor will lead to something, or at least the knowledge that in death his pains will end. Sisyphus knows, however, that the labor of getting his great rock up the hill is to end with its rolling down again; and, since he is immortal, the absurdity of this unexhilarating grim labor will last — forever.

Sisyphus [writes Camus] watches while the stone, in a few minutes, rolls down to that lower field again, from which he is going to have to push it up, once more, to the top. And he goes down again to the plain.

It is during his return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stone is itself already stone. I see that man going down again with heavy but steady tread, to the torment of which he will know no end. This hour, which is like a breath of relief and returns as surely as his woe, is the hour of consciousness. At each of these moments, when he leaves the heights and makes his way, step by step, toward the retreats of the gods, he is superior to his destiny, stronger than his rock.

If this myth, then, is tragic, it is because its hero is conscious. For where, in fact, would the agony be, if at each step he were sustained by hope of success? The laboring man of today works every day of his life at the same tasks, and that destiny is no less absurd. However, it is not tragic, save in those uncommon moments when it becomes conscious. Sisyphus, impotent and rebellious, the proletarian of the gods, knows the whole extent of his miserable condition. It is of this that he thinks at the time of his descent. And yet, this foreknowledge, which was to have been his torment, simultaneously crowns his victory: there is no destiny that is not overcome by disdain.

If on certain days the descent is made in sorrow, it can also be made in joy. The term is not too strong. I again imagine Sisyphus returning to his rock. The sorrow was only at the beginning. For it is when the scenes of earthly life weigh in the memory too strongly, when the call of happiness becomes too urgent, that sorrow surges to the human heart: that is the victory of the rock, that is the rock itself. The weight of sorrow is too heavy to be borne. Those are the nights of our Gethsemane. However, the crushing verities, when recognized, dissolve. It was thus that Oedipus obeyed his destiny, at first without knowing. And from the moment that he knew it, his tragedy commenced. Yet, at the same instant, blind and despairing, he realized that the only bond that held him to the world was the cool fresh hand of a young girl. And it was then that a remark resounded, immeasurably great: “In spite of all these trials, my advanced age and the grandeur of my soul lead me to conclude that all is well.”Note 32

“In a man’s attachment to his life,” this author concludes, “there is something stronger than all the miseries of the world.”Note 33

The sentiment is noble. There is, however, something wonderfully French — Cartesian, Socratic — in the declaration that, since life (or, as we are saying today, “existence”) will not conform to reason, it can properly be termed absurd. “I think, therefore I am,” has had to become, “I am, but I can’t think why!” which can be embarrassing to one who thinks of himself professionally as a thinker. The Bodhisattva, on the other hand, is “without thought.” The Buddha is called “the one who is thus come” (tathāgata). And as Dr. Frankl states to this point in his ambrosial book: “What is demanded of man is not, as some existential philosophies teach, to endure the meaninglessness of life; but rather to bear his incapacity to grasp its unconditional meaningfulness in rational terms. Logos is deeper than logic.”Note 34

The question as to meaning, to be asked by the young hero of the Grail quest when he beholds the rites of the Grail Castle, is the same, essentially, as that asked by the hero of the Pañcatantra fable, and its effect also is the same: the release of the sufferer from his pain and the transfer of his role to the questioner. Moreover, these two questions are at root the same as Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be,” since their concern is to learn the meaning of a circumstance “thus come” — to which there is no answer. There is, however, an experience possible, for which the hero’s arrival at the world axis and his readiness to learn (as demonstrated by his question) have proven him to be eligible. Will he be able to support it? Nietzsche, in The Birth of Tragedy, wrote of what he termed the “Hamlet condition” of the one whose realization of the primal precondition of life (“All life is sorrowful!”) has undercut his will to live. The problem of the Grail hero will therefore be: to ask the question relieving the Maimed King in such a way as to inherit his role without the wound.

The Maimed King’s wound and the agony of the revolving wheel are equivalent symbols of the knowledge of the anguish of existence as a function not merely of this or that contingency, but of being. The common man, in pain, believes that by altering his circumstances he might achieve a state free of pain: his world, in Gottfried’s phrase, being of those who want only “to bathe in bliss.” Socratic man too believes that life can be trimmed somehow to reason — his own Procrustean bed for it. Hamlet learned, however, that his world, at least, had something at the heart of it that was rotten and, like Oedipus, who read the riddle of the Sphinx (“What is man?”), became maimed. Oedipus, self-blinded, is equivalent to the Maimed King — and, as Freud has shown, all of us are Oedipus. For this there is no cure. However, as Camus points out, Oedipus, like Sisyphus, came through his experiences of his maimed life to the realization that all is well.

The wound in Christ’s side, delivered by Longinus’s spear, is a counterpart of that of the Maimed Fisher; also, the poisoned wound of Tristan. The crown of thorns is a counterpart of the Bodhisattva’s turning wheel, and the Cross, of the wheel of Ixion (Figures 11 and 68). Christ’s role as the Man of Sorrows, blood flowing from the nail wounds in his palms and feet, head dropped to one side, eyes closed, and blood streaming from that painful crown, corresponds to the Grail King in torture. In his other mode, however, as Christ the Logos, Triumphant (as True God), crucified yet without anguish, head erect, eyes open, outward gazing at the world of light, the nails there, but no sign of blood, he is the image of that immanent “radiance” (claritas), “thus come,” which hangs everywhere, as the world’s joy-to-beknown, behind its battered face of torment. In his being, as in the Bodhisattva, there is ambrosia. He too descended into Hell: and though the credo of his church returned him to the sky, in his Bodhisattvahood he is still there — as Satan.

“Look forward!” Virgil said to his follower, Dante, when, having descended through all the murk of Hell, the two were approaching on a plain the center of the earth — the center of the universe — the immovable spot! “See if thou discern him.”

Dante peared ahead. And so we read:

As when a thick fog breathes, or when our hemisphere darkens to night, a mill that the wind is turning might look from afar, such a structure, it seemed to me that I then saw. Because of the wind proceeding from it, I drew me behind my Leader; there was no other shelter. For I was now (and with fear I put it into verse) there where the shades were wholly covered with ice and showed through like a straw in glass. Some are lying down; some are upright, this one with his head, and that with his soles uppermost; another, like a bow, bends his face to his feet. And when we had gone so far forward that it pleased my Master to show me the creature that once had had the fair semblance [i.e. Lucifer, now Satan], he took himself from before me and made me stop, saying: “Lo Dis! and lo the place where it is needful that thou arm thyself with fortitude!”

How frozen and faint I then became, ask it not, Reader, for I do not write it, because all speech would be little. I did not die and did not remain alive: think now for thyself, if thou hast a grain of wit, what I became, deprived alike of death and of life.

The emperor of the woeful realm stood forth from the ice from the middle of his breast; and I were better compared to a giant, than a giant to his arms. Imagine how great now must be the whole, proportionate to such a part. And if when he lifted his brows against his Maker he was as fair as he now is foul, well indeed should all tribulation proceed from him.

Oh, how great a marvel it seemed to me, when I saw three faces on his head! one in front, and that was crimson; the others were two, adjoined to this above the middle of each shoulder, and they were joined up to the place of the crest: and the right seemed between white and yellow, the left such as those who come from where the Nile descends. Beneath each came forth two great wings, of size befitting so great a bird; I never saw such sails on the sea. They had no feathers, but their fashion was of a bat; and he was flapping them so that three winds were proceeding from him, whereby the river of that part of Hell was all congealed. With six eyes he was weeping, and over three chins were trickling the tears and bloody drivel. At each mouth he was crushing a sinner with his teeth, in the manner of a hackle, so that he thus was making three of them woeful. To the one in front the biting was nothing to the clawing, whereby sometimes his back remained all stripped of the skin.

“That soul up there which has the greatest punishment,” said the Master, “is Judas Iscariot, who has his head within, and plies his legs outside. Of the other two who have their heads downward, he who hangs from the black muzzle is Brutus; see how he writhes and says not a word; and the other is Cassius, who seems so large-limbed. But the night is rising again; and now we must depart, for we have seen the whole.”Note 35

And then, grotesquely, when the wings opened, the two moved in and caught hold of the shaggy flanks of the awesome, prodigious, suffering monster, and down through the ice in which he was fixed, between the matted hair and frozen crusts, crawling from shag to shag, down his side they descended, Virgil ahead, Dante after. And when they had come to where the haunch becomes thigh, the Leader, Virgil, with great effort and stress of breath, grappled hard and now was climbing; for he had just passed the center of the earth and was going up.

The meanings of the colors of the faces of the Angel of Eternal Sorrow they had seen were as follows: impotence, the red, scarlet with rage; hate, the white and yellow, pale with jealousy and envy; ignorance, the black, in its own darkness — exactly in negative to the attributes of the Trinity: Power, the Father; Love, the Son; and Wisdom, the Holy Ghost. So that God and Satan are here a pair of opposites — and we know, by now, what that means. Hell and Heaven too, Satan, Trinity, and all, are as meaningless — thus come — as being itself. The affirmation of one is the affirmation of all. They are separate in the field of space-time as appearances, or as concepts, whereas in truth — the Wisdom of the Yonder Shore, the logos deeper than logic, beyond opposites — they are the left and right of one being that is no being and neither is nor is not: as indeed Dante, when viewing that vision of the shadow of God, had himself been neither dead nor alive.

The Buddha at the world tree, the “immovable spot” around which all revolves, transcended sorrow in illumination: “There is release from sorrow — nirvāṇa,” he taught, and in the end he vanished from this world. The Bodhisattva, on the other hand — he whose “being” (sattva) is “illumination” (bodhi) — remains addressed to this vale of tears, testifying to the non-duality of nirvāṇa and the sorrows of this world: the bitter-sweetness of the life that, in Gottfried’s words, is bread to all noble hearts in its terrible joy. There is no escape to which the Bodhisattva on the revolving platform refers us, but only a source within ourselves of the competence to be and not to be, to move with the world and to be absolutely still within — at once.

Comparing the four orders of imagery, then, of Christ crucified, the suffering yet not suffering Bodhisattva, the sinner Ixion, lashed to his whirling flaming wheel, and the wounded Grail King of the Waste Land, it appears that though at root related — in a certain sense even the same — yet in import they differ, as representing four interpretations or modes of experience and judgment of the same reality.

The two Asian figures, the Bodhisattva and Christ, are of immaculate virtue and supernatural race, whereas the Europeans are both sinners who in their symbolic suffering achieved no such stature as either of the Asian saviors. Of the two Asians, the Bodhisattva is entirely of this world. There is no Heaven to which he refers us, no place or god “out there,” whence or from whom he has come down. He is a reflex of the consciousness of being — of which not men alone, but beasts, trees, and even minerals are the organs, modifications, and degrees. And in reminding us of that in ourselves, he is our savior from the illusion of this, our ephemeral yet everlasting suffering.

Christ Jesus, on the other hand, has been traditionally interpreted altogether differently: in the way, for example, of Pope Gregory, as our “Agenbuyer” from the Devil (Figure 10); or in the way of Saint Anselm, as our compensation to the Father for Adam and Eve’s happy fault; or still again, according to the view put forward first by Abelard, as a demonstration of God’s love for man, to recall our hearts to himself from the false allures of this Devil’s world.Note 36 Only add to this last the Indian words tat tvam asi, “thou art that” — thou thyself, unknown to thyself, art that beloved lover (in the sense of the words of the Sufi mystic Bayazid: “Then I looked and I saw that lover, beloved, and love are one!”)Note 37 — and behold! the two savior figures, along with even the Allah of Islam, and the Devil as well, have become one. “For in the world of unity,” said Bayazid, “all can be one. — Glory to me!”Note 38

In contrast, both of the European figures have been somehow made aware of themselves as sinners and are in need, consequently, of redemption. But what is their redemption to be? Well, since they were both originally redeemer figures, one might suggest that all they require is to be reminded of their own occluded divinity. That would accord with the final stanza of Wagner’s opera when the wonderful youth Parsifal, “through compassion’s supreme power [karuṇā] and the force of purest knowledge [bodhi],” has healed the suffering king of his wound and himself assumed the sacred role: “Erlõsung dem Erlöser! Redemption to the Redeemer!” sings the chorus, and the curtain falls.

Parsifal, become the Grail King, did not inherit the wound. We must now learn why.

III. The Quest beyond Meaning

Chrétien de Troyes, whose version of the Grail Quest is the earliest we possess, declares that he derived the subject matter of his legend, the matière, from a certain book given him by the Count Philip of FlandersNote 39 — who, it is known, was twice in the Levant: first in 1177 and again in 1190, when he died there. “And the best tale it is,” states Chrétien, “that may be told in a royal court.” Wolfram von Eschenbach, on the other hand, cites a Provençal author, otherwise unknown to us, named Kyot, whose existence many scholars doubt. Chrétien’s unfinished version of the romance lay on the desk before Wolfram as he wrote. However, his own version, starting as it does with the career of Parzival’s father in the Orient and following the young Grail quester himself through a series of trials not described in Chrétien’s work — and, moreover, from a totally different point of view, Chrétien having been, apparently, a cleric concerned to reduce the Quest to Christian termsNote 40 — makes it certain that if there never was any such book as that of Kyot for him to follow, Wolfram must either have had before him the same — or somewhat the same — book as Chrétien, or else have been himself wholly responsible for everything that qualifies his work for consideration as the first great spiritual biography in the history of Occidental letters.

According to Wolfram’s perhaps invented reference, the Provençal author Kyot discovered the legend of the Grail in Toledo, in the forgotten work of a heathen astrologer, Flegetanis by name, “who had with his own eyes seen hidden wonders in the stars. He tells of a thing,” states Wolfram, “called the Grail, whose name he had read in the constellations. ‘A host of angels left it on the earth,’ Flegetanis tells, ‘then flew off, high above the stars.’ ”Note 41

Now the Holy Grail, even in Chrétien’s text, was neither a bowl nor a cup, not the chalice of the Last Supper, nor the cup that received Christ’s blood from the Cross, but, as Professor Loomis reminds us, “a dish of considerable size.” The word grail is defined by a contemporary of Chrétien, the abbot Helinand of Froidmont, as “a wide and slightly deep dish, in which costly viands are customarily placed for rich people,” and one of the continuators of Chrétien’s unfinished romance mentions a hundred boars’ heads on grails: “an impossibility,” states Loomis, “if the grails were chalices.”Note 42

In Wolfram’s text the Grail is a stone. “Its name,” he declares, “is lapis exilis,” which is one of the terms applied in alchemy to the philosophers’ stone: “the uncomely stone, the small or paltry stone”;Note 43 so that Wagner’s representation of Wolfram’s intentionally nonecclesiastical, indeed even non-Christian, almost Islamic, symbol as a glowing super-chalice of Christ’s blood brings to his production — as Nietzsche protested — a note of Christian sanctimoniousness that is inappropriate.

“By the power of that stone,” we read in Wolfram, “the phoenix burns and becomes ashes, but the ashes restore it speedily to life.” The stone, that is to say, will bring us not only to the nigredo and putrefactio of the alchemical love-death (Figure 58), but also back to the world — as gold. “So the phoenix,” we continue with Wolfram, “molts and thereafter very brightly shines. Moreover, there never was a man so ill that, if he saw that stone, would not live, unable to die within a week of that day. Nor in complexion would he ever change: one’s appearance, whether maid or man, remains the same as on the day that stone is seen, or as at the commencement of the years of one’s prime. And should one look upon that stone for two hundred years, nought but one’s hair would gray. Such virtue does it communicate to man that flesh and bones grow young at once. The stone is also known as the Grail.”Note 44*

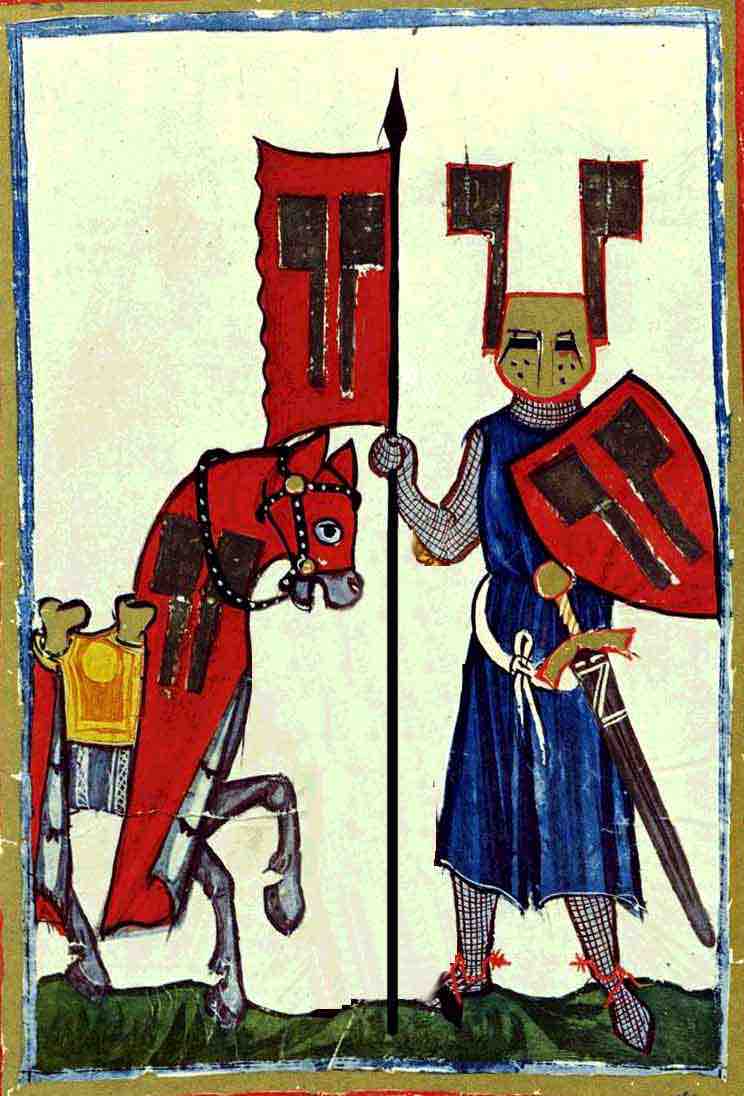

Figure

69. Wolfram von Eschenbach

Figure 69 is a fanciful portrait of Wolfram in his jousting armor: for he was a poet of knightly race, more proud of his feats in arms than of his literary gifts; yet he was honored in his day, and is honored now, even above Gottfried, as the most significant poet of the German Middle Ages, and on the European scale is to be ranked second not even to Dante. In contrast to the Tristan poet, who, we have seen, was a gracefully sophisticated, classically educated city man of letters, learned in Latin, philosophy, and theology, as well as in French and German poetry and romance, Wolfram claimed (perhaps ironically, to contrast himself with Gottfried; however, possibly also with that deep disdain of the aristocrat for the cleric smell of ink) not to know a single letter of the alphabet.Note 45 In Gottfried’s work battle scenes are described with sardonic wit, as from a distance; in Wolfram’s, on the contrary, as by one who had himself engaged in chivalrous battle and experienced its moral worth. Gottfried’s settings are largely domestic, urban; Wolfram’s, all afield. And his aim for life was neither rapture aloft, quit of the flesh, nor rapture below, quit of the light, but — as the symbol on his shield and flag, horse and helm makes known — the way between. His own fanciful interpretation of his hero Parzival’s name, perce à val, “pierce through the middle,”Note 46 gives the first clue to his ideal, which is, namely, of a realization here on earth, through human, natural means (in the sinning and virtuous, black and white, yet nobly courageous self-determined development of a no more than human life) of the mystery of the Word Made Flesh: the logos deeper than logic, wherein dark and light, all pairs of opposites — yet not as opposites — take part. “A life so lived,” as he wrote at the conclusion of his epic, “that God is not robbed of the soul through the body’s guilt; yet can retain with honor the world’s favor: that is a worthy work.”Note 47 Or as in his opening stanza:

If vacillation be neighbor to one’s heart, this can become distressful to the soul. Blame and praise alike are inevitable for the man whose courage is undaunted, mixed of white and black as it must be, like a magpie’s plumage. Such a one may nevertheless know blessedness, though both colors have a part in him: that of Heaven, that of Hell. Completely black-complexioned is the one uncertain of himself, who in his hue of darkness even increases; whereas he of steady purpose trends to the light.Note 48

So let us trend now, through the middle, to the Castle of the Grail and its stone of wisdom, here on earth, which is called the Perfection of Paradise.*