Chapter 8

THE PARACLETE

I. The Son of the Widow

BOOK I: THE BLACK QUEEN OF ZAZAMANC

“Brave, and slowly wise: thus I hail my hero.” So the poet introduces Parzival.

Figure

70. GahmuretHis father, Gahmuret, brave too, had been a

younger son of royalty, who, though invited to share his brother’s

kingdom, had preferred to prove himself on his own, and so,

adventuring, came to Baghdad, where he served the caliph so

valiantly that his reputation extended soon from Persia to Morocco.

He left, however, to sail to Zazamanc, where the people are as

black as night.

The black ladies leaned from their windows to watch the company descend from his ship into their port, Patelamunt: ten pack horses before, with twenty squires behind; also pages, cooks, and cooks’ helpers; twelve noble cavaliers, a number of them Saracens; eight caparisoned steeds with a ninth bearing the knight’s jousting saddle and a young shield-bearer striding saucily at its side; mounted trumpeters and a drummer that swung and struck his instrument over his head, flute-players and fiddlers three; after all of which came the great knight himself with his ship’s captain riding beside him.

Gahmuret was greeted with delight by the black Queen Belakane; for her city was under siege, with a black army of Moors at the west, and eastward a white, of Christian knights. Her crown was an immense transparent ruby that encased her head like a bubble; through it her dark face could be seen. Courteously she received him. They looked upon each other and their two hearts were unlocked. And when he asked the reason for the siege, with sighs and tears she confessed she had been hesitant in love. Her chivalrous lover, Isenhart, driven to desperation, a princely youth, black like herself, had sought renown by riding without armor into battles and these armies were of his friends, come to avenge his death. Her whole kingdom was in mourning.

“I will serve you, my lady,” said Gahmuret.

“Sir,” she replied, “you have my trust.”

And he overthrew, next day, the champions of both sides.

The rescued queen led him in triumph to her castle, where she removed his armor with her own black hands and bestowed on him her kingdom and herself. More dear to him than his life was then that black and heathen wife; not more, however, than the feats of arms from which she restrained him. As king, therefore, he languished, and one night, at last, sailed away; so that in grief she bore their son (Feirefiz Angevin, she named him ), in whom God had wrought a miracle: he was piebald, white and black, like a magpie’s plumage.

And his mother, when she saw him, kissed him over and over and over again, on the white spots.

BOOK II: THE WHITE QUEEN OF WALES

The maiden queen Herzeloyde of Wales proclaimed at Kanvoleis a tournament: herself and two countries, the prize. And as the kings and knights, arriving, set up tents and pavilions on the meadow, she with her ladies sat watching from the windows.

“What a pavilion that one is!” an impudent young page exclaimed. “Your country and crown aren’t half its worth.”

It was of the rich king of Zazamanc: its transport had required thirty horses.

The unofficial warming-up games commenced next morning gradually when the kings and knights from many lands, galloping up and down the great field, began maneuvering in companies, colliding in single charges, splintering spears, clashing swords, and running each other down. The old father of King Arthur was out there, and Gawain, still a mere lad; Gawain’s father, King Lot of Norway; also Rivalin, who had yet to sire Tristan, and the mighty Morholt of Ireland, who was yet to be Tristan’s foe.

The king of Zazamanc, resting in his tent, lured by the gradually increasing tumult, rose, became arrayed, put on his headgear (which, like the ruby crown of his queen, was an immense transparent diamond, fitting over his whole head), and mounting his caparisoned charger, rode out onto the field, where he unhorsed one man of might after another. Many spears became snow on that field, saddles flew, men in iron clothing ran about among the legs of horses, shattered shields and banners lay all about. And when darkness closed it was evident to all, from the general exhaustion, there could be no tournament the next day.

In his pavilion that night the infinitely rich king of Zazamanc was entertaining the kings, princes, and others who had fallen to him, when the noble Lady Herzeloyde arrived with joy in her eyes to embrace him; for the talk of all was that he had gained the field. He had just that evening learned, however, of the deaths, during his years of absence, of his brother and his mother, so that when the queen came into his tent he was in tears. Moreover, nostalgia for his distant wife had been coming upon him all that day. Further, an embassy had just brought a letter from an earlier lady with claims on him, the Queen of France. So that when Herzeloyde also claimed him, he demurred.

“I have a wife, my lady, who is more dear to me than myself.”

“You must renounce that Moor,” she answered; “renounce your heathendom and love me — by our own religious laws.”

He put forward the claim of the Queen of France; after that, of his new sorrow; next, the cancellation of the tournament: at which last, however, appeal was made to a judge, who declared that, having donned his helm, he had officially competed and must now accept the award. She capitulated to his last demand: never, like his former wife, to prevent him from entering tournaments. And when that was done, she took his hand.

“And so now,” she said, “you belong to me and must yield yourself to my charge.”

She led him by a secret way to a place where he dismissed his sorrow and she her maidenhood. And he then did an admirable thing: he released those he had overthrown; to all poor knights gave Arabian gold; to the traveling minstrels, presents; and to the kings who were there, his gems. In delight and full of praise for that king all rode away to their homes.

However, the sword blade of Herzeloyde’s joy soon snapped; for when Gahmuret learned that his former lord, the caliph, was being overridden by Babylon, he sailed to serve him and six months later the message returned of his death.

Queen Herzeloyde gave birth to a son so large she hardly survived. Bon fils, cher fils, beau fils, she called him, as she pressed into his tiny mouth the little pink buds of her breasts. “I am his mother and his wife,” she thought; for she felt that she again held Gahmuret in her arms. And she mused: “The supreme Queen gave her breasts to Jesus, Who for our sake suffered death on the Cross, and thus to His faith in us remained loyal. But the soul of anyone who underestimates His wrath will be in trouble on Judgment Day. This fable I know to be true.”

BOOK III: THE GREAT FOOL

Overwhelmed with grief, the widowed queen withdrew from her castle and world to a solitary waste, charging her people never to mention a word about chivalry to her son. He was thus raised ignorant of his heritage and even of his name. All he ever heard himself called was fils: bon fils, cher fils, beau fils. Yet with his own little hands he made himself a tiny bow with which to shoot at birds. The sweetness of their song transfixed his heart, and when he saw them dead, he wept.

His mother told him of God. “ He is brighter than day, yet assumed the form of man. Pray to Him when in trouble; He is faithful and gives help. There is another, however, the Lord of Hell, dark he is and faithless. Turn your mind away from him, and from doubt.”

Figure

71. Parzival spies three knightsIn early youth strong

and beautiful, the boy was one day rambling on a mountainside when

he heard galloping hoofs and thought the noise must be of devils.

Three knights then flashed into view, and, deciding that they were

angels, he fell to his knees to pray. A fourth appeared with bells

ringing from his stirrups and right arm, who pulled to a halt and

asked the stupefied youth if he had seen two knights ride past with

an abducted maid.

“O God of help!” the youth prayed to the knight. “Give me help!”

Gently the prince answered: “I am not God. We are four knights.”

“What is a knight?” the lad asked; and he was

told: told, also, of King Arthur, who made knights. And when they

had shown him what a sword was and a lance, and passed on, he ran

in rapture to his mother, who, when told what he had seen,

collapsed.

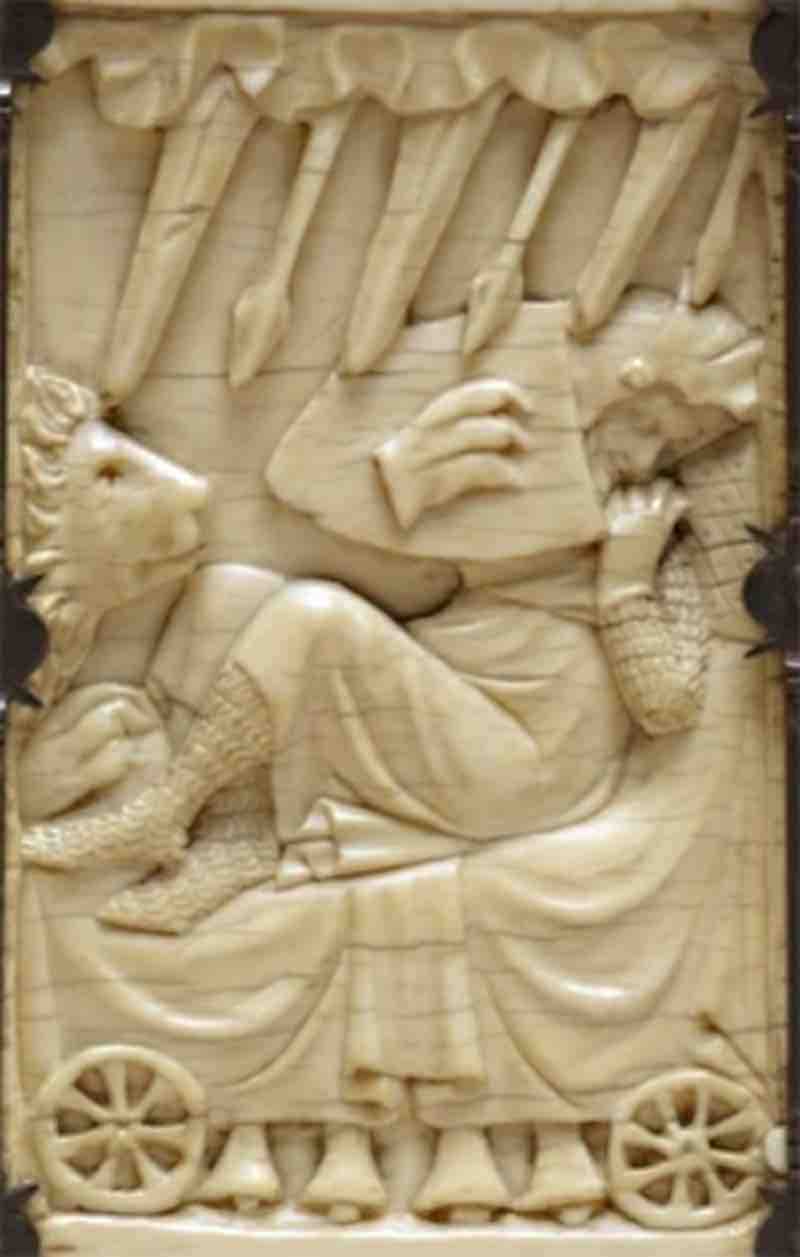

Figure

72. Parzival and HerzeloydeBelieving that if she made

him look the fool, he might be forced to return, she procured the

poorest horse she could find and clothed him in a clown’s rig of

hempen shirt and breeches in one piece, coming halfway down his

legs, a monk’s hood, and clumsy, untanned boots; then gave him the

following advice:

- to cross streams only where most shallow

- to greet people with the words, “God protect you!”

- to ask advice of those with gray hair, and

- to strive to win a good lady’s ring and then to kiss and embrace her

She also told of a knight, Lahelin, who had taken from her two countries. “I will avenge that,” her son said as he mounted, with a quiver of darts on his back. She kissed him, stumbled after as he rode, and when he had disappeared, fell and was dead.

Simplicity’s child came to a brook that a rooster could have crossed, rode along to a very shallow place, and forded to the meadow beyond, where a colorful tent was to be seen. Within, a young wife lay asleep with her coverlet to her hips (God himself had fashioned that body), and on her soft white hand there was a ring, to seize which the youth pounced upon the bed. During the lively tussle that ensued he acquired, besides the ring, a forced kiss and a brooch; then made a meal of her provisions, forced another kiss, and rode off.

“Aha!” the knight, her husband, exclaimed when he returned.

He was the brother of the knight Lahelin, Duke Orilus de Lalander, and in a paroxism of mortification, smashed her saddle, tore up her clothes, bade her ride behind him in shreds, and departed to find the youth by whom his honor had been undone — who, meanwhile, had come to a forest cliff, beneath which a lady sat with a dead knight on her knees, tearing her hair in grief. Simplicity approached.

“What is your name?” she asked.

“Bon fils, cher fils, beau fils," he replied.

She was Sigune, his mother’s sister’s child, and she recognized the litany. “Your name,” she said, “is Parzival. Its meaning is ‘right through the middle’; for a false love cut its furrow through the middle of your mother’s heart.” Then she told him his parents’ story and of how the knight on her lap, Prince Schianatulander, had been slain defending his heritage against Lähelin and Orilus.

“I shall avenge these things,” he told her. But she, fearing for his life should he come to Arthur’s court, sent him off in the wrong direction, along a broad, much-traveled road, where he greeted whomever he passed, “God protect you!” and when night came, turned to the large dwelling of an avaricious fisherman, who refused shelter until the brooch was offered, then became so hospitable that the next morning he brought his guest all the way to the towers of Arthur’s court.

No Curvenal had trained this youth as Tristan had been trained. Trotting forward on his stumbling mount, he saw come galloping from the castle a knight in bright red armor with a goblet in his hand, who, when greeted, reined and called to him to tell the court, he would be waiting on the jousting field — with apologies to the queen for having splashed her gown with the wine. He was King Ither of Kukumerlant ("Cucumberland"), who had seized the cup in token of his claim to a portion of Arthur’s kingdom.

At the castle gate were sentries and a crowd; but God had been in good spirits when fashioning Parzival: his beauty and the kindness of a young page got him through to the Round Table, where Arthur himself heard his brash demand to be knighted on the spot and given the red suit of armor he had seen on the knight outside — whose message he briefly told. The court’s rude seneschal, Keie, shouted to let him get the suit himself; but a lady, Cunneware by name, of whom it had been prophesied that she would never laugh in her life until she saw the flower of knighthood, laughed loudly as Parzival passed, going out, for which Keie beat her with his staff. And when the court fool Antanor cried that Keie would be sorry for that beating, he too tasted of that stick.

Parzival trotted to the field, challenged Ither for his suit, and the knight, indignantly reversing his bright red lance, struck him with its butt so hard that both he and his pony went sprawling among the flowers of that April day — who got quickly to his feet, however, and replied with a swift dart through the grill of the Red Knight’s vizor to his eye, and he fell from his charger, dead. The powerful stallion whinnied loud. And the lout was rolling the knight about to remove his bright red armor, when the queen’s page who had shown him to the court came running, helped with the suit and attired him over his mother’s clothes, shoes and all (which he refused to remove), took away the darts (forbidden to knighthood), taught him briefly the use of shield and spear, and fastened upon him the knight’s sword. Parzival then sprang onto the charger. “Return the goblet to the king,” he said as the horse began to move, “and tell that beaten maid I will avenge her pain.”

Figure

73. Parzival rides forth

He rode the great Castilian at a gallop all day because he had not been taught how to check it, and that evening came to the towers of the aged Prince Gurnemanz de Graharz (Wagner’s Gurnemanz, with whose words the opera starts, who is here the lord of a castle of his own, not, as in Wagner’s work, a member of the company of the Grail). Reposing with his young falcon beneath a large tree outside his castle, the old knight rose to greet the red horseman, whose steed halted before him. “My mother told me,” said the rider, “to ask advice from people whose hair is gray.” To which the elder replied courteously, “If you have come for advice, young man, you must pledge to me your friendship.” And he cast from his hand his hawk, which, wearing a little golden bell, flew as messenger to the castle, where the gates opened, a company appeared, and the visitor was made welcome. But when his armor was removed, his fool’s costume came to view, and all were embarrassed and amazed. Yet his form was noble. Gurnemanz took him to his heart and for a season coached him in knighthood.

“You talk,” said the old knight, “like a little child. Why not be quiet now about your mother and take thought of something else?” He gave the youth certain rules of conduct: never to lose the sense of shame; to be compassionate to the needy; neither to squander wealth nor to hoard it; not to ask too many questions; to reply to questions frankly; to be manly and of good cheer; not to kill a foe begging mercy; to be loyal in love, and to remember that a husband and wife are one: they blossom from a single seed.

Figure

74. Gurnemanz and his daughterOld Gurnemanz, who had

lost three sons, hoped now to marry Parzival to his daughter. The

youth had a feeling, however, that before experiencing a wife’s

arms he should prove himself in the field. In the poet’s words: “He

sensed in noble striving a lofty aim for both this life and beyond

— and that is still no lie.”Note 1

Compare in Goethe’s Faust the famous line: “Whoever strives

with unremitting effort, we can redeem”;Note 2

also, Goethe’s words to

Eckermann on the Godhead effective in the living. When Parzival

rode away, therefore, with his mentor’s sad permission, the old

man, riding beside him a short way, felt in his heart that he was

giving to knighthood a fourth son, his fourth great loss.

BOOK IV: CONDWIRAMURS

Parzival, now a knight well schooled, let his stallion take him through the forest as it would, too melancholy to care; and riding into wild, high, wooded mountains came, before day was done, upon a roaring mountain, stream that tumbled downward over cliffs to the city of Pelrapeire, where it was spanned by a wickerwork drawbridge, flimsy and without a rope, under which its waters coursed to the sea. Across the bridge some sixty armed knights were to be seen, who as Parzival approached warned him back. His stallion balked, so he dismounted, and as he led the beast across the rocking span, the knights withdrew and the city gates closed. A pretty maid leaning from a window asked if the knight were a friend or a foe, and when a portal was opened he found within the city walls the whole population armed. But they were frail, haggard with hunger, and there were everywhere towers, turrets, and armed keeps.

Admitted to the castle, relieved of his arms,

and clothed in a mantle of sable with a fresh wild furry smell, he

was conducted to the maiden queen, the beautiful

Condwiramurs.

Figure

75. Condwiramurs He sat beside her for some time in

silence, in obedience, he thought, to Gurnemanz’s law, and the

young queen wondered; but then deciding that, as hostess, she might

start the talk herself, she asked whence he had come. He told of

Gurnemanz and then learned from this queenly maiden that she was

his niece. She was more radiant, like a rose both red and white,

than the two Isolts together.

When her guest that night had retired and already slept, she came quietly to his bedside, not for such love as changes maids into women, but for aid and a friend’s advice. Yet she wore the raiment of battle: a white silk nightgown, over which she had tossed a samite robe; and since all in the castle were asleep, she could talk now as she would.

She knelt beside his bed. He woke and discovered her. “Lady, are you mocking me?” he said. “One kneels that way only to God.”

She replied, “If you will promise on your honor, to be temperate and not to wrestle with me, I shall lie then by your side.”

Neither she nor he, states the poet, had any notion of joining in love. Parzival lacked all knowledge of the art, and she, desperate and ashamed, had come in misery of her life. In tears, Condwiramurs, the orphan queen, told him of her plight. A certain powerful king, Clamide by name, with an army led by his seneschal Kingrun, had taken every castle of her land, right up to that rickety bridge. He had slain the elder son of Gurnemanz and now wanted her for his wife. “But I am ready,” she said, “to kill myself before surrendering my maidenhood and body to Clamide. You have seen the height of my palace. I would cast myself into the moat.”

And there we have Wolfram’s second point, the second term of an opposition right through the middle of which his hero and heroine were to pass: on one hand, the magic of the senses, sheer passion (the side of Isolt and Tristan), and on the other hand, the sacramentalized marriage of convenience, society, and custom, without love (Isolt and King Mark).

Said Parzival to the young queen weeping in bed beside him: “Lady, is there no way to console you?”

“Yes, my lord,” she answered, “if I could be freed from the power of this king and his seneschal Kingrun.”

“My lady, let Kingrun be a Frenchman, a Briton, or what-not, my hand here will defend you as far as my life can serve.”

And that night ending, its day arrived, and with day the army of Kingrun, showing many a banner and Kingrun himself in the lead.

Riding forth to his first battle, Parzival galloped out the castle gate and against the charging seneschal with such force that the girths of both saddles broke. Their swords flashed, and presently Kingrun, whose fame in the world was great, lay on his back surrendering, with Parzival’s knee on his chest. The fresh young knight, recalling his mentor’s rules, bade him go submit to Gurnemanz.

“Gurnemanz,” said the man, “would kill me: I slew his son.”

“Then surrender here to the queen.”

“They would hack me to bits in that town.”

“Go to Britain, then, to King Arthur’s court, and submit there to the maiden who was beaten for my sake.”

So the battle ended, and Condwiramurs, when her knight returned, embraced him before all. Her citizens paid him homage, and she declared him to be her ami, her lord and theirs.

“I shall never be the wife,” she said, “of any man on earth but the one I have just embraced.” Then all looked to the sea, and behold! there were merchantmen arriving, ships bearing food and nothing but food, good meats and wine.*

After a jubilant feast and festival, the two were asked would they share one bed, and they answered together, yes. However, he lay with her so decently that not many a lady nowadays would have been satisfied with such a night. He left the young queen a maiden. Yet she thought of herself as his wife, and next day, in token of her love, did up her hair in the way of a matron; conferring on him, her beloved, all her castles and her land: this virgin bride. Two days and two nights more they were happy in this way — although now and then there came to him the idea which his mother had advised of embraces. Gurnemanz too had explained to him that husband and wife are one. And so — if I may tell you so — they enlaced legs and arms and he found the closeness sweet; and that old custom, ever new, was theirs thereafter: in which they were glad and nowise sad.Note 3

“The ineffable, the mystical and transcendent quality of this love,” comments Gottfried Weber on this critical passage, “is epitomized in the ‘purity’ of the first three nights, in the full sense of the Middle High German term, kiusche. The morning following the first night, the ‘virgin bride’ (magetbaeriu brut) felt herself to be a ‘woman’ (wip: a ‘wife’); for her soul had already absorbed an absolutely new, perfectly fulfilling, traumatic impression, experienced as completely unique: the virginality of her heart had been bestowed upon that other as her gift, he was now her spouse vor gote, ‘before God.’ … And it was only after this consummation of the marriage purely in soul and spirit that the bond, already recognized as confirmed, was substantiated through extension to the physical estate.”Note 4

In time, however, Clamide himself arrived, having heard report of his seneschal’s defeat at the hands (it was said) of the Red Knight (King Ither of Kukumerlant, whose armor Parzival wore). He appeared with a second army, and all the machines of war. Greek fire, catapults, battering rams, and portable sheds were brought to bear, until, learning from his captives of the marriage of the maid he had come to win, Clamide sent to the castle a challenge to single combat, and the Red Knight again broke from the city at a gallop. The king charged to meet him and they fought till their steeds collapsed, then went at it with their swords. Presently Clamide weakened. Parzival tore his helm off, so that the blood gushed from his nose and eyes, and was about to do him dead when the once-great king begged mercy and was sent — like his seneschal — to Arthur’s court, to be subject to the Lady Cunneware. And there was amazement there indeed when those two appeared; for that beaten king had been richer even than Arthur in wealth of lands.

But at Pelrapeire, after fifteen months of love and jubilation, a time came for departure. One morning Parzival said courteously (as many there saw and heard), “If you will permit, my lady, I should like, with your allowance, to see how things stand now with my mother: I know not whether ill or well.”

He was so dear to her, the young queen could not deny him, and he rode forth from their castle and town, again alone.

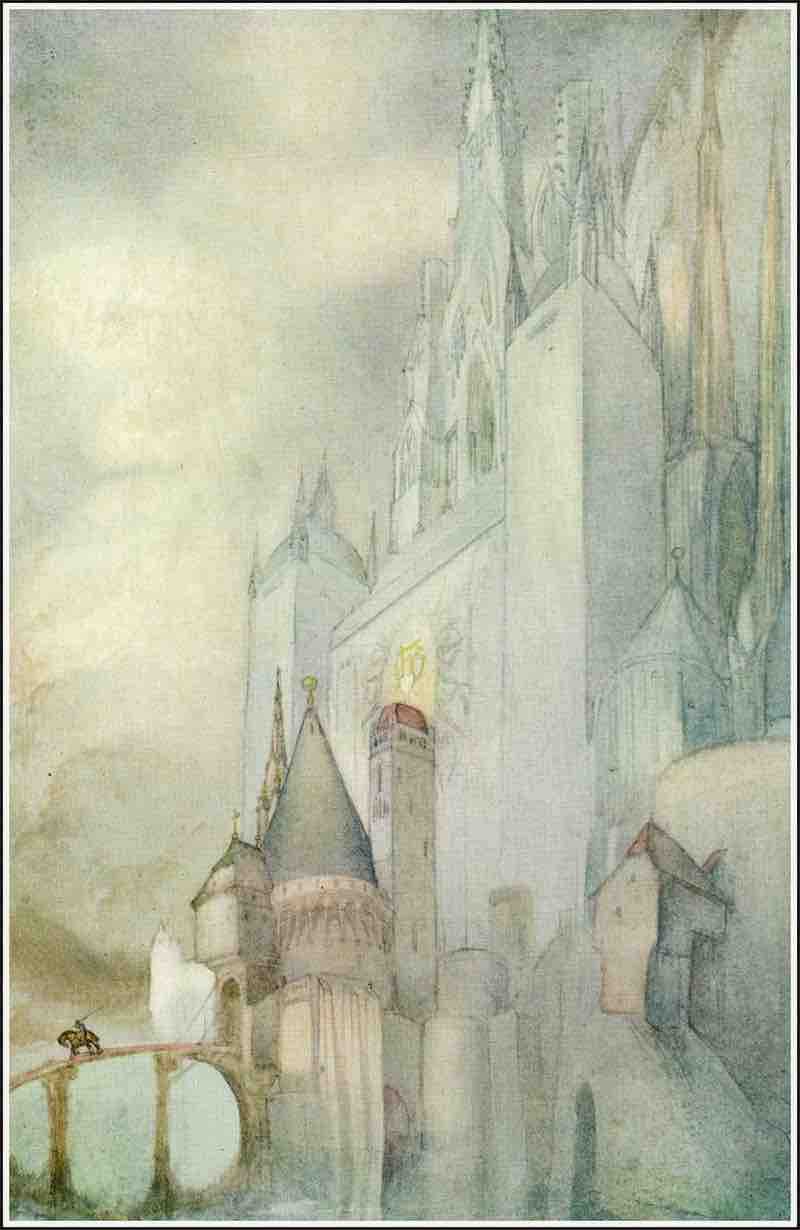

BOOK V: THE CASTLE OF THE GRAIL

And again riding without reins, but now

through autumn foliage, not spring, he arrived that evening at a

lake where he saw two fishermen

Figure

76. The Fisher King floating at anchor in a boat, one so

richly clad he might have been king of the world. From his bonnet

peacock feathers plumed. The Red Knight called to know where

lodging for the night might be obtained, and the fisherman richly

clad — he was deeply sad of mien — replied that he knew of no

habitation but one within thirty miles. “There, at the head of the

cliff,” he called back, “turn right, ascend the hill, and when you

come to the moat, call to let down the bridge. But have a care! The

roads here lead astray; no one knows where. If you arrive, I shall

be your host.”

The perilous wilderness again: the “dark wood” of Dante’s opening lines!

Without difficulty, at an easy trot, Parzival rode past the cliff, turned right, and ascended the wooded hill to the moat before a castle of many turrets, where a squire from within caught sight of him and cried to know what he wanted.

“The fisherman sent me,” Parzival called, and the drawbridge descended. He crossed and passed into a spacious court, where the grass was unworn by jousting; for that castle was in sorrow: no banners flew. When his armor was removed and they beheld his beautiful young face, still boyish, beardless, they were joyful. A cloak of finest silk was cast around him, which, he was told, was of the queen, whom he was presently to see: Repanse de Schoye (Repense de Joie). He was conducted kindly to an immense hall with a full hundred chandeliers and as many couches, well apart, a carpet before each, and on each of which there sat four knights. In three great marble fireplaces fires blazed of aromatic aloewood, and the lord of castle, carried in on a stretcher, was set before the central of these: who bade Parzival sit beside him. And the sense of it all was of sorrow.

Through a door a squire then came rushing, bearing a lance; and by this rite the sorrow was increased. From its point gushed blood that ran down its length to the bearer’s hand and on into his sleeve. The squire circled the hall and when he reached the door again, ran out.

A steel door opened at the end of the great room and two beautiful maidens entered, clothed in gowns of earth-brown wool, drawn tight by girdles at the waist. Wreaths of flowers crowned their long flowing fair hair, and each bore a lighted candle in a golden candlestick. They were followed by another two, each with a little ivory stool, which, when they bowed, all four, before the host, was set before him on the floor. The four stood back, and from the door there entered twice four again, clad, however, in gowns more green than grass, long, full, and gathered at the waist by long, narrow girdles, richly wrought. The first four of these bore candles, and the second four a precious tabletop carved of hyacinth-tawny translucent garnet, which they carefully set down on the two little ivory stools; after which the eight in green stepped back to the four in brown, and the number standing now was twelve.

Next appeared six: two bearing on cloths two very sharp white silver knives, which the candles of the other four made to gleam. Clothed in gowns of two manners of silk, one dark, the other shot with gold, these, approaching, courteously bowed. The two knives were placed upon the table, and all six stood back before the twelve. When see! from that door there entered six again in the same parti-colored gowns, bearing in tall glass vessels lights of costliest balsam; and they were followed by the queen, Repanse de Schoye: radiant as a dawn breaking, clothed in Arabian silk, and she bore on a deep green cloth of gold-threaded silk the Joy of Paradise, both root and branch.

That was the object called the Grail. It was beyond all earthly joy, and such that its bearer was required to preserve her purity, cultivate virtue, and spurn falsity [in contrast to that doctrine of the Church whereby the personal morals of its clergy — who, moreover, were exclusively male — were declared to bear no relation to the operation of the sacraments they dispensed]. The queen, together with her six maidens bearing lights, advanced and courteously bowed as she placed the Grail before the host — while Parzival, watching as she did so, thought only, “The robe I have on is hers.” The seven drew back to the other eighteen and the queen, then standing in the center, had twelve at either hand.

A hundred tables, now carried in, were set before the couches. White cloths were spread upon them. The host washed his hands from a vessel and Parzival from the same. Four cars carried costly golden vessels to every knight in the hall, and a hundred squires, bearing white napkins, began gathering from before the Grail a feast which they served to the knights.

“And I have been told,” states Wolfram, “and I pass it on to you (but on your responsibility, not mine, so that if I speak false, we do so together), that whatever one reached one’s hand to take, it was found there before the Grail: food warm and cold, foods new and old, both cultivated and wild.… For the Grail was beatitude’s own fruit and provided such abundance of the world’s sweetness that its delights were very like what we are told of the kingdom of Heaven.… And for whatever drink one held one’s cup, that was the drink that flowed by the power of the Grail: white wine, mulberry, or red.”

Figure

77. Don't ask too many questions

And Parzival marked all this, the richness and great wonder, but thought, remembering Gurnemanz: “He counseled me, in sincerity and truth, not to ask too many questions.”

There appeared a squire, bearing a sword in a jeweled sheath, its hilt a ruby, its blade a source of wonder. Presenting this to Parzival, the melancholy host declared that before God had maimed him, he had worn this sword in battle. And still the guest never spoke.

“For that I pity him,” declares Wolfram; “and I pity too his sweet host, whom divine displeasure does not spare, when a mere question would have set him free.”

The queen and twenty-four maidens advanced, bowed courteously to both Parzival and his host, took up the Grail, and proceeded to their door, through which, before it closed behind them, he saw on a couch in a large room, where there was also a great fireplace, the most beautiful old man his eyes had ever seen: he was grayer even than mist. “Your bed,” said his host politely, “I think, is ready,” and the company dispersed.

Figure

78. Leaving the castleThe youth was shown to his room.

Four fair maidens saw him to bed with wine and fruits of the sort

that grow in Paradise. And he slept long, but with threatening,

terrible dreams, and when he woke the morning was half gone. His

armor and two swords were on the carpet, and he had to don them

alone. His steed was tethered outside, at the foot of the main exit

stair, with his shield and spear set up nearby; but not a soul did

he see about. Nor did he hear anywhere a sound. He mounted. The

great gate was open. Through it ran the tracks of many horses. And

as he crossed the bridge, a squire, unseen, pulled the draw so hard

that it nearly struck his steed as it sprang clear. Then somebody’s

voice was heard: “Ride on, you goose, and bear the hatred of the

sun. If you had only moved your jaws and asked the question of your

host! You’ve lost for yourself great praise!”

The knight called back for an explanation, but the castle again was all silence, and, turning, he followed the other tracks, which, however, gradually dispersed and were lost.…

Before him, in a linden tree, sat a maiden with a dead knight, embalmed, propped against her: again Sigune, his mother’s sister’s child. When she saw him, “This wilderness,” she warned, “is dangerous; turn back!” Then she asked whence he had come, and he told her of the castle. “It is a mile or so from here,” he said.

“Do not lie to me,” she answered. “For thirty miles round about, no hand has touched here either tree or stone, save for a single rich castle that many seek but none has found. For he who seeks will not find it. The name is Munsalvaesche (French, mon salvage: "my salvation"), and its kingdom, Terre de Salvaesche ("Land of Salvation"). It was bequeathed by the aged Titurel to his son, King Frimutel, who was killed in a joust for love. One of his sons, who can neither ride nor walk nor lie nor stand, is its present lord, Anfortas. Another son, Trevrizent, has retired as a hermit from the world.”

“I beheld great marvels there,” declared Parzival; and it was then that she recognized his voice. “I am the same,” she told him, “who revealed to you your name.”

“But your long brown wavy hair,” he asked, “what has become of it?” For she was bald. “And let us bury that dead man,” he suggested, “whose company you keep.”

For response, she only wept. Then, noticing his sword, she disclosed its danger. On the second blow it would break. However, if dipped in the waters of a certain spring beneath a rock it would come together and be stronger than before. “It requires a magic spell,” she said, “which perhaps you failed to learn. Did you ask the question?”

“No,” he answered.

“Oh, alas,” she cried, “that I must look upon you!” And she stared with loathing. “You should have felt pity for your host and have asked concerning his pain.”

“Dear cousin, show me a friendlier mien,” Parzival protested. “For whatever wrong I have done, I shall make amendment.”

“You are cursed,” she cried. “At Munsalvaesche you forfeited both your honor and your fame. I will say no more.”

She turned away. And he too turned away. He wheeled his charger and, riding off, came remarkably soon upon two fresh tracks: one of a charger well shod, the other of an unshod mount — which latter he soon overtook. It was a beast in miserable case, with a lady on its back clad in shreds, who, when she turned and saw him, gave a start.

“I have seen you before,” she said. “And may God give you more honor and joy than, from your treatment of me, you deserve!”

She was the lady of the tent. No part of her gown was untorn, yet in her purity she was clothed. And when Parzival’s stallion, bending its head to her mare, neighed, the knight riding far ahead turned back and on seeing a knight beside his dame, immediately couched his spear for the charge. He was elegantly armed. On his shield was a dragon, as though alive; another was on his helm; and there were many more, in gold, rare stones, and rubies, on his gambeson; more still on the trappings of his steed. The two collided, and the lady, watching, wrung her hands, wishing neither any harm. The dragons, one by one, received blows and serious wounds. The two champions fought with swords from their mounts, but finally, seizing each other, tumbled to the ground with Parzival on top; and the other, forced to surrender, was compelled next to forgive his all-but-naked wife and to report, then, to Arthur’s court and the Lady Cunneware.

Afraid of what her husband now would do to her, the lady held apart; but at last, “Lady,” said he, “since I am beaten for your sake — well, come here: you shall be kissed.” She leaped down and ran to him, kissing as commanded, careless of the blood about his face. On a sacred relic, which they presently discovered in an empty hermitage, Parzival swore that in the episode of the tent the lady had been all innocence, and he no man, but a fool. Orilus thereupon was reconciled, and the couple rode off to Arthur’s court in joy. “For, as all the world knows,” comments the author, “eyes that weep have a mouth that is sweet. Great love is born of joy and sorrow, both.”

BOOK VI: THE LOATHLY DAMSEL

“Would you not like to hear,” the poet asks, “how Arthur with his court set forth from Karidoel, his castle and land?” He set forth to add to his Round Table company the champion (of whom no one knew the name) responsible for those three impressive arrivals submitting to Cunneware: Kingrun, Clamide, and now, with his lovely wife Jeschute (French, je chute: “I fall”) the Lady Cunneware’s own brother, proud and fierce Orilus.

The company had been out some eight days with its tents, banners, and pavilions, when a party of the king’s falconers, hawking of an evening, lost their best bird. It disappeared into the woods. But the night being chill and the forest unfamiliar, it flew to the neighborhood of a campfire, which chanced to be of Parzival, who was also in that wood. Next morning the world lay covered with the winter’s first light snow; and when the Red Knight mounted, to ride on, the falcon followed.

Figure

79. Parzival staring at the drops of blood on the

snowBefore them, with a great roar of wings and cackling, a

thousand wild geese went up, and the hawk, darting, struck at one

so fiercely that its blood fell on the snow in three large drops —

bright red on purest white — the sight of which brought Parzival to

a stop. And he was sitting on his mount, in recollection of his

wife’s complexion (the bright red of her cheeks and chin on the

pure white of her skin), when a squire of the Lady Cunneware,

riding with a message to her brother, spied him in the distance,

like a statue on his steed, and galloped back to camp, setting up a

din.

“Fie! You cowards! Wake up! The Round Table is disgraced! There is a knight here trampling your tent ropes!”

The whole camp became a-clatter, and a young knight, Sir Segramors, dashed into Arthur’s tent, where the king lay sweetly sleeping with his queen, snatched away their sable coverlet, and cried at them to be the first to go — to which, laughing, they consented. And he rode at the unknown knight still lost in absorbed arrest — whose steed, however, to meet the charge, wheeled of itself, and when its rider’s view of his idol was broken, his knightly honor was saved; for he lowered his spear in such a way that the oncoming Sir Segramors soon learned what it meant to fly. Without a word or sign, the stranger knight then returned to his contemplation of the snow.

Sir Keie came next, and the Lady Cunneware was avenged; for he ended wedged between a rock and his shattered saddle, with a broken arm and leg, and his horse beside him, dead, while the knight, again without word or sign, wheeled back to his dream.

Third to come was the courteous knight, Sir Gawain, with neither spur, sword, shield, nor lance. “What if it be love that holds that man enthralled,” he thought, “as, at times, it has held me!” Remarking the focus of the knight’s gaze, he flung a yellow scarf across the red drops; and when Parzival murmured to the vanished presence, “Who has taken you from me?” and more loudly, “But what has become of my lance?” Gawain courteously answered, “You just broke it in a joust, my lord.” He mollified skillfully the other’s irritation at the interruption, told his name, offered his service, and in peace led the knight to Arthur’s camp, where the two were greeted by a joyous crowd, from which the Lady Cunneware emerged to welcome her champion with a kiss.

The precious guest, brought to Gawain’s pavilion, was relieved there of his armor and clothed in a mantle of silk, provided by Cunneware. It was fastened with an emerald at the neck, and at the waist with a girdle of rare stones; so that he looked like an angel come to flower on this earth when Arthur and his knights arrived.

“You have brought me pain as well as joy,” said the king; “yet more honor than I have ever received from any man before.” And he ordered spread on a flowery field a great circular cloth of Orient silk, large enough for every knight to be seated by his lady, and there, when all had made the guest welcome, they awaited an adventure: “For,” as the poet tells, “it was a firm custom of the king that none should eat with him on a day when adventure failed to visit his court.” And it was then that she appeared of whom we have now to speak, whose tidings brought grief to many.

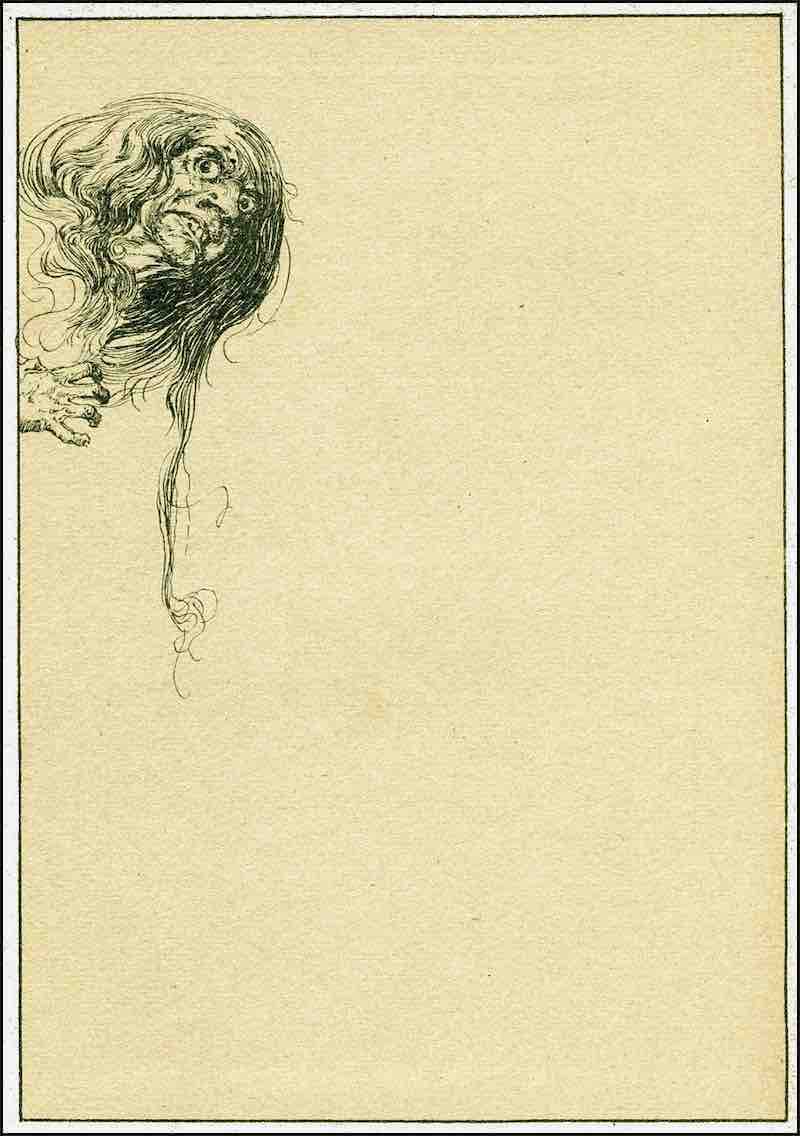

Figure

80. CundrieOn a mule the maiden rode, as tall as a

Castilian steed, yellow-red, with nostrils slit and sides terribly

branded. The rich bridle was excellently wrought. She was Cundrie

[Wagner’s Kundry], the sorceress, eloquent in many tongues, Latin,

Arabic, and French. She wore a cape more blue than lapis lazuli,

tailored in the French style, with a fine new hat from London

hanging down her back, over which there fell and swung a switch of

long black hair, as coarse as the bristles of a pig. She had a

great nose, like a dog; two protruding boar’s tusks, and eyebrows

braided to the ribbon of her hair, bear’s ears, a hairy face, and

in her hand a whip with ruby grip, but fingernails like a lion’s

claws and hands charming as a monkey’s. She rode directly to

Arthur.

“O son of King Utpandragun,” she said to him in French, “what you have here done today has brought shame both to yourself and to many a Briton. The Round Table is destroyed: dishonor has been joined to it. Parzival here has the look of a knight. The Red Knight, you call him, after that noble one he slew; yet none could less resemble that noble knight than this.” She turned and rode directly to the Welshman. “Cursed be the beauty of your face! I am less a monster than you,” she said. “Parzival, speak up! Tell why, when the sorrowful Fisherman sat there, you did not relieve him of his sighs. May your tongue now become as empty as your heart is empty of right feeling. By Heaven you are condemned to Hell, as you will be by all the noble of this earth when people come to their senses. I think of your father, Gahmuret; of your mother, Herzeloyde: alas that I have had to learn now of the dishonor of their child!

“Your noble brother Feirefiz, son of the queen of Zazamanc, is black and white, yet in him the manhood of your father never has failed. He has won through chivalrous service the queen of the city of Thabronit, where all earthly desires are fulfilled; yet had the question been asked at Munsalvaesche, riches far beyond his would here and now have been yours.”

She broke into great tears, wrung her hands, and changing the subject, turned to the company. “Is there here no noble knight yearning to win both fame and noble love? I know four queens and four hundred maidens, all in the Castle of Wonders; and all adventure is wind compared to what might there be gained through noble love. The road is difficult, yet I shall be in that place this night.” And she rode abruptly off with the words: “O Munsalvaesche, sorrow’s home! To comfort you, alas, there now is none!”

But to Parzival of what help were now his brave heart, true breeding, and manhood? Yet there was one great virtue more in him, namely shame. He had not been guilty of real falsity. Shame brings honor. Shame is the crown of the soul and a sense of shame the highest virtue.

The first to begin to weep for the shamed knight in whose welcome this circle had been gathered was the lady Cunneware; many another lady followed. And they were all thus sitting in sorrow and tears when there came riding a knight, richly armed, holding a sword aloft, still sheathed, who cried, “Where is Arthur? Where Gawain?” He gave greeting to all save Gawain, whom he then challenged to a duel of hate. “He slew my lord while giving greeting,” he said; “and I here challenge him to meet me forty days from this day before the King of Ascalun [Avalon], in the city of Schanpfanzun.” When he gave his name he was recognized as a knight of the greatest wisdom, honor, and fame, Prince Kingrimursel; and when he rode away the entire astonished company rose and broke into a tumult of talk.

“I am resolved to enjoy no joy,” said Parzival to a dark heathen lady from Janfuse, who had approached to tell him of his brother. “The man whom Cundrie named may well be your brother,” she had told him. “He is a noble king, both black and white, worshiped as a god. I am the daughter of his mother’s sister, and perceive that you too have nobility and strength.”

“I am resolved to enjoy no joy until I shall have seen again the Grail,” Parzival declared. “If I am to suffer the scorn of the world for having obeyed a rule of courtesy, the counsel of Gurnemanz may perhaps not have been quite wise. A sharp judgment has here been passed upon me.”

The manly Gawain came and kissed him. “God give you good fortune in battle,” said Gawain. “And may God’s power help me to serve you one day as I would like!”

“Alas,” replied Parzival, “what is God? Were He great, He would not have heaped undeserved disgrace on us both. I was in His service, expecting His grace. But I now renounce Him and His service. If He hates me, I shall bear that. Good friend, when your own time comes for battle, let a woman be your shield. May a woman’s love be your guard! When I am to see you again I do not know. My good wishes go with you.”

The Lady Cunneware, sorrowing, led her knight to her pavilion, with her soft, lovely hands there to arm him. King Clamide, whom he had sent to her in service, had lately asked her to marry him, and for that she thanked her knight. He kissed her and rode away, clad in shining steel. And many more of Arthur’s knights that day rode away for the Castle of Wonders; but Gawain left for his war in Schanpfanzun.

II. First Intermezzo: The Restitution of Symbols

Parzival’s denunciation of God—or of what he took to be God: that Universal King, “up there,” reported to him by his mother — marks a deep break in the spiritual life not only of this Christian hero, as a necessary prelude to his healing of the Maimed King and assumption of the role without inheriting the wound, but also of the Gothic age itself and thereby Western man. In Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man the same break is represented in essentially the same terms; for in each of these Catholic biographies (eight centuries apart), the hero’s self-realization required a rejection first of his mother’s mythology of God, the authorized, contemporary ecclesiastical mask, and a confrontation then, directly, with the void wherein, as Nietzsche tells, the dragon “Thou Shalt” is to be slain:Note 5 the void of Parzival’s exit to the wilderness and of Stephen’s alienation from home, and his brooding, in Ulysses, on the mystery deeper than the sea.

In each of these works it was through “a struggle for the existential possibilities of faith” (to use a phrase coined by the philosopher Karl Jaspers)Note 6 that the redemptive symbols of the hero’s inheritance of myth were transformed and effectively integrated as guides for the unfolding of his life. The local, provincial Roman Catholic inflections of what are actually archetypal, universal mythic images of spiritual transformation are, in both works, opened outward, to combine with their non-Christian, pagan, primitive, and Oriental counterparts; and they become thereby transformed into nonsectarian, nonecclesiastical, psychologically (as opposed to theologically) significant symbols. I have already remarked the relevance of the Waste Land theme to the state of the European Church under its authorized yet inauthentic spiritual guides (wolves in shepherd’s clothing, as they were called by their contemporaries) in the period of Innocent III.Note 7 In Joyce’s work the hero, Stephen Dedalus, though grateful to his Jesuit masters — “intelligent and serious priests, athletic and highspirited prefects, who had taught him Christian doctrine and urged him to live a good life and, when he had fallen into grievous sin, had led him back to grace” — yet began to realize at an early age that “some of their judgments sounded a little childish in his ears,” and that “the chill and order of their life repelled him.”Note 8 “He was destined,” he mused, “to learn his own wisdom apart from others or to learn the wisdom of others himself wandering among the snares of the world. The snares of the world were its ways of sin. He would fall. He had not yet fallen but he would fall silently, in an instant. Not to fall was too hard, too hard; and he felt the silent lapse of his soul, as it would be at some instant to come, falling, falling, but not yet fallen, still unfallen, but about to fall.”Note 9 And then, in the brothel scene of Ulysses, at the nadir of this young man’s plunge to the abyss, in the context of a Black Mass and at a stage of his adventure roughly comparable to Station 10 of the round of Figure 5, that vision of the Irish sea-god appeared, amalgamated with Śiva, which was to him the sign of a power deeper than the sea, in which all beings, all things, are consubstantial:Note 10 and he then was able to recognize in his sympathy for Bloom’s suffering a shared life, as of one power in two reflections, poles apart.Note 11

Comparably, in Wolfram’s Castle of the Grail, where Celtic, Oriental, alchemical, and Christian features are combined in a communion ritual of unorthodox form and sense, the young hero’s spiritual test is to forget himself, his ego and its goals, and to participate with sympathy (caritas, karuṇā) in the anguish of another life.

However, Parzival’s mind on that occasion was on himself and his social reputation. The Round Table stands in Wolfram’s work for the social order of the period of which it was the summit and consummation. The young knight’s concern for his reputation as one worthy of that circle was his motive for holding his tongue when his own better nature was actually pressing him to speak; and in the light of his conscious notion of himself as a knight worthy of the name, just hailed as the greatest in the world, one can understand his shock and resentment at the sharp judgments of the Loathly Damsel and Sigune. However, those two were the messengers of a deeper sphere of values and possibilities than was yet known, or even sensed, by his socially conscious mind; they were of the sphere not of the Round Table but of the Castle of the Grail, which had not been a feature of the normal daylight world, visible to all, but dreamlike, visionary, mythic — and yet to the questing knight not an unsubstantial mirage. It had appeared to him as the first sign and challenge of a kingdom yet to be earned, beyond the sphere of the world’s flattery, proper to his own unfolding life: a kingdom hidden from the known world and screened from even himself by his fascination with the glamour of knighthood; a kingdom the vision of which had opened to him — significantly — only after his series of great victories, not as a retreat from failure but as his guerdon of fulfillment. His decision to act in that intelligible sphere, not according to the dictates of his nature but in terms of what people would think, broke the line of his integrity, and the result to his soul was first shown to him alone by the baldness of his cousin, but then to all the world, and to his utmost shock and shame, by that Loathly Damsel, richly arrayed, as ugly as a hog.

This figure of the Loathly Damsel is comparable, and perhaps related, to that Zoroastrian “Spirit of the Way” who meets the soul at death on the Chinvat Bridge to the Persian yonder world. Those of wicked life see her ugly; those of unsullied virtue, most fair.Note 12 The Loathly Damsel or Ugly Bride is a well-known figure, moreover, in Celtic fairytale and legend. We have met with one of her manifestations in the Irish folktale of the daughter of the King of the Land of Youth, who was cursed with the head of a pig (as here, a pig’s bristles and boar’s snout), but when boldly kissed became beautiful and bestowed on her savior the kingship of her timeless realm. The Kingdom of the Grail is such a land: to be achieved only by one capable of transcending the painted wall of space-time with its foul and fair, good and evil, true and false display of the names and forms of merely phenomenal pairs of opposites. Geoffrey Chaucer (1340?–1400) provides an elegant example of the resolution of the Loathly Bride motif in his “Tale of the Wife of Bath”; John Gower (1325?–1408) another, in his “Tale of Florent.” There is also the fifteenth-century poem “The Weddynge of Sir Gawen and Dame Ragnall,” as well as a mid-seventeenth-century ballad, “The Marriage of Sir Gawain.” The transformation of the fairy bride and the sovereignty that she bestows are, finally, of one’s own heart in fulfillment. The knightly rules of Gurnemanz had prepared Parzival well for his ambition in the world, but left his own unfolding interior life, his “intelligible character” (to use Schopenhauer’s term), not only unguided but unrecognized and completely out of account. And yet, when the old knight offered him his daughter, the youth discreetly departed, not because she was unlovely, unworthy of him, or unkind, but because an inward knowledge already told him that a life — a life with substance — has to be earned and fashioned from within, not received from the world as a gift, as the Maimed Grail King had received his castle and throne. And it was precisely this integrity of heart that marked Parzival for a destiny beyond the bounds and gifts of any settled social order, proved him eligible to approach the Grail, and brought him in the next adventure directly to his counterpart, a young woman resisting to the death the suit of a powerful, highly respected king who, though offering her the world, had not awakened love. In contrast to her cousin Liaze, the compliant daughter of Gurnemanz, submissive to her father’s will, Condwiramurs, like Parzival, stood for a new ideal, a new possibility in love and life: namely, of love (amor) as the sole motive for marriage and an indissoluble marriage as the sacrament of love — whereas in the normal manner of that period the sacrament was held as far as possible apart from the influence of amor, to be governed by the concerns only of security and reputation, politics and economics: while love, known only as eros, was to be sublimated as agapē, and if any such physical contact occurred as would not become either a monk or a nun, it was to be undertaken dutifully, as far as possible without pleasure, for God’s purpose of repopulating those vacant seats in Heaven which had been emptied when the wicked angels fell.

But now, it is rather curious and of considerable interest to remark that in Wagner’s operatic transformation of the Parzival there is no mention either of Condwiramurs or of the new Grail King as a married man, whereas in Wolfram’s work it was precisely because of this love-marriage and through his loyalty to its sacrament that Parzival was to achieve at last the healing of Anfortas and succeed to his throne without inheriting his wound. Furthermore, whereas in Wolfram’s Castle of the Grail all members of the procession except the startling bearer of the bleeding lance were female — young, stately, and lovely — those of Wagner’s chorus and procession are exclusively male. And still further, Gurnemanz, whose calls to the guardians of the Grail Forest sound the opening words of Wagner’s opera, serves there not as a teacher of the laws of chivalry but as a guide directly to the Grail Temple. He has no daughter to offer, nor respect for marriage, but is himself a member of the Temple order, and in the spirit rather of a monk than of a knight cries out at Parsifal, when the “Guileless Fool” has failed to ask the question: “Go find yourself a goose, you gander!” After which, the first curtain falls.

The leading theme of Wolfram’s writing is thus in Wagner’s work dismissed: the lesson of loyalty in true love, joined with heroism in action, as the human way to perfection, passing in freedom between the two impersonal compulsions, on one hand of mere nature, the daemonic species-lust (eros) of the body, and on the other of sheer spirit, the celestial charity (agapē) of saints. Accordingly, in Wagner’s work the Grail is represented, as in Tennyson’s sentimental Idylls of the King, as the holy chalice of the Last Supper; and when the vessel is uncovered before the suffering Amfortas a ray of light pours upon it from aloft, while a chorus of boys’ voices, floating down from high in the dome, echoes angelically the words of Christ in consecration of the sacrament of the altar:

Take and drink my blood,

In recollection of our love!

Take and eat my body,

And in doing so, think of me.

But there is absolutely nothing of this kind either in Wolfram or in Chrétien’s work.

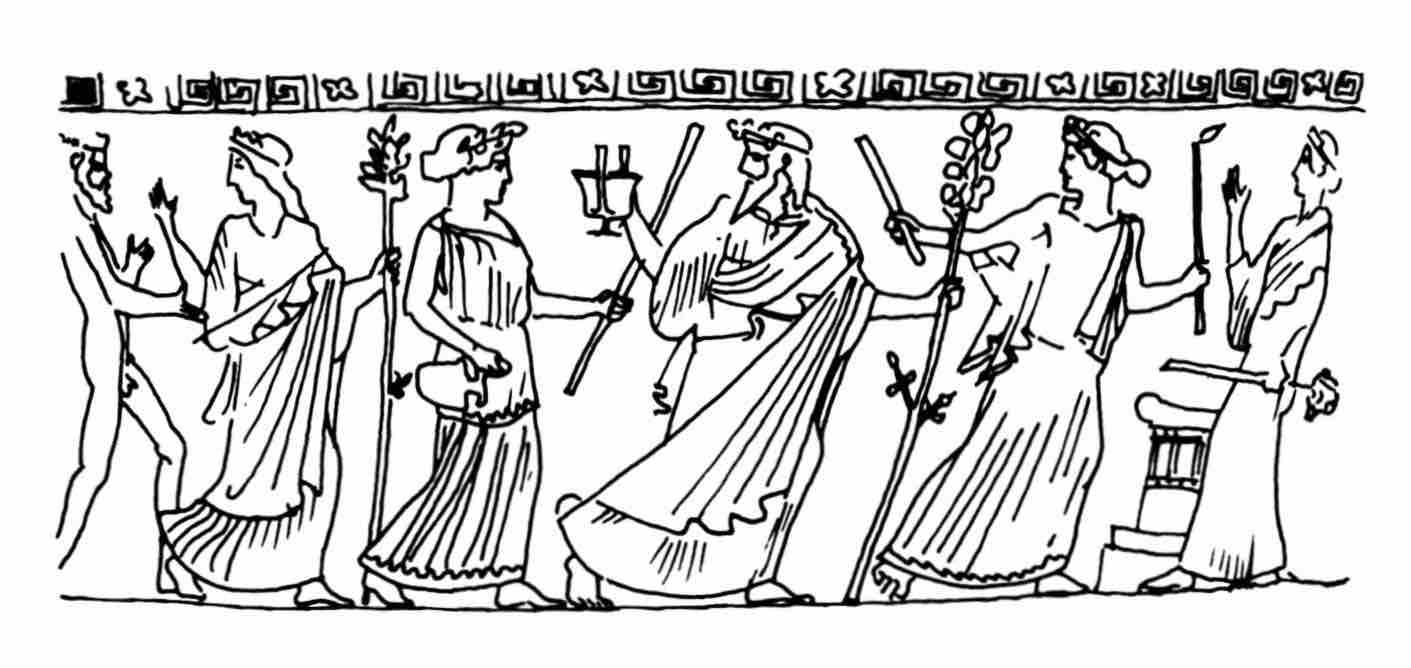

Figure

81. Dionysian Scene; mid-5th century b.c.

Figure

82. The Fisher among Baccic Satyrs; c. 500 b.c.

Jessie Weston was the first to suggest, I believe, that the symbols of the Bleeding Lance borne by a squire and the Grail carried by a maiden must have been originally sexual emblems in some classical mystery rite.Note 13 The Greek vase painting of Figure 81, from the fifth century b.c., attests to the antiquity of such symbols in the context of initiation rites. The flaming staff and empty pitcher in the hands of the young girl are matched by the sprouting thyrsus, running with living sap, and the proffered wine cup of the god. And in Figure 82, from another vase of about the same date, showing the Fisher among Bacchic satyrs, we have a most striking confirmation of Miss Weston’s thesis. In the early Christian communities Christ became associated with the imagery of such rites: with the Singer and Good Shepherd Orpheus (Figures 3 and 11); the bread and wine of Dionysus, in which the god himself is consumed; the death and resurrection of Tammuz, Adonis, Attis, and Osiris; and the sexual imagery (in certain Gnostic sects) of the god in menstrual blood and semen, suffering in both the woman and the man, made whole through sexual union. The original reference of such pagan symbols, however, had not been forward to the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ (i.e. to Roman Catholic theology), but inward to the powers of nature operative in the universe and in man; and the function accordingly of the Hellenistic initiation rites had not been to refer the mind to Christ or even, finally, to Apollo, but to effect in the individual certain psychological transformations, adjustments, and illuminations. The lance that pierced Christ’s side is, by analogy, the boar that slew Adonis and, like the boar, a counterpart of the slain divinity himself, in whom opposites are transcended: death and birth, time and eternity, the slayer and the slain; also, male and female. Accordingly, the lance in Christ’s wound is comparable to the liṅgaṃ in the yonī (or as the Buddhists say, “the jewel in the lotus” ) , and the blood pouring from the wound (the yonī) is equally pouring from the lance (the liṅgaṃ), as the one life-substance of the god: for the two, though apparently separate, are the same. And that is the lesson of the bleeding lance symbolically borne about the great hall, with the blood running down the length of its shaft and over the bearer’s hand into his sleeve. It tells of the lance by which the Maimed Fisher was wounded: Anfortas on his bed of pain, Christ upon the Cross; announcing the sense of the mystery to come, of the Grail, the Perfection of Paradise, in which opposites are at one. For such signs to be effective in life, however, they must move the human heart to recognition and response in human terms, until which moment their mere presence, supernaturally interpreted, though perhaps of comfort and of promise, do not quite convince.

The Castle of the Grail, like the bowl of a baptismal font or the sanctuary of the winged serpent (Figure 18), is the place — the vas the temenos — of regeneration and, as such, a sanctuary in which sexual symbolism is both appropriate and inevitable. The great virtue of Wolfram lay in his translation of the magically interpreted symbols back into the language of human heterosexual experience, illustrating in his narrative, through many modes and on many levels, the influence of the sexes on each other as guiding, inspiriting, and illuminating forces — with the symbols there to inform us of the grades of realization achieved: as in the instance of Parzival. When crude and raw, seeking only his own good (kneeling in prayer to what he took to be a god of help, indifferent to his mother’s sorrow, violently taking what he wanted from the lady of the tent), he met an avaricious fisherman who pointed him to the castle of worldly fame; but when he had risked death for another and experienced with her the initiation of love (Condwiramurs: Old French, conduire-amours: “to conduct, to serve, to guide love”), the fisherman met was the Fisher King, pointing to the Castle of the Grail, for the attainment of which he was now eligible to strive. And in this dreamlike epic of earthly spiritual quest the heroes and heroines are many, though the destinies of all — as in Schopenhauer’s cosmic vision of the most miraculous harmonia praestabilita — interlace.

III. The Ladies’ Knight

BOOK VII: THE LITTLE LADY OBILOT

Parzival, now at large, alone, in the Waste Land of his own disoriented life, is to wander for a span of five years. He may be thought of as the Stephen Dedalus of this medieval work, an introverted, essentially solitary youth, deeply moved by a supreme sense of purpose; while Gawain, his elder by some sixteen years, can be compared in a way to Bloom, the extrovert, moving in a casual course from one adventure to the next, largely with ladies on his mind.

Gawain had been riding, we know not how many days, when he left the forest and beheld before him on a hillside many banners and a mighty host on the move in his direction. And where their road joined his, he drew aside to watch many costly helmets go past and multitudes of new white spears, flying pennons. Mules bearing armor followed, and numerous loaded wagons; tradesmen laden with exotic wares, and ladies in large number: no queens, these last, but soldier girls, some wearing their twelfth love-token. A rabble of young and old besides, footsore and bedraggled, of whom some would have been appropriately garnished with a rope around the neck.

Gawain asked a young squire whose multitude this was, and learned that its lord was King Poydiconjunz of Gors, the father of that rude Prince Meljacanz who had once abducted Arthur’s queen. Poydiconjunz and his son, with the powerful Duke Astor of Lanverunz, were here in the van of the still larger force of the king’s young nephew, King Meljanz of Liz (French, mal chance: "bad luck"), who, having been spumed by the daughter of his loyal vassal, Duke Lyppaut of Bearosche, was here coming to gain his suit by force. The duke had raised Meljanz from boyhood and was now in the deepest distress.

Gawain’s interest was greatly excited by this tale, and, not knowing that Parzival was in the army of Meljanz, he pressed on to the fortified town, before which a large defending army was encamped; and although one tent rope crowded the next, he and his equipage rode through, until he came below the castle walls. Above, from a window, leaned the difficult daughter, Obie, who had brought this all about, together with her mother and little sister, Obilot.

“Who is that fine young knight just arrived?” the mother asked.

“O Mother!” answered the daughter. “That is no knight. That is just a merchant!”

“But they have brought along his shields.”

“Many merchants have that custom,” said the girl.

The little sister, however, was admiring the knight. “Shame on you!” she scolded. “He is no merchant. He is handsome. I want him for my knight.”

Gawain’s squires had meanwhile settled him beneath a large linden tree, and presently the old Duke Lyppaut himself came out to request him to assist in the coming battle.

“I would do so, gladly,” said Gawain, “but must avoid battle, my lord, until an appointed time. For I am on the way to redeem my honor in combat, or else to die on the field.”

The old man, disheartened, rose and returned to his city gate, but within found his little Obilot.

“Father,” she said, “I think the knight will do it for me: I want to pledge him to my service.” And her father, with hope, having released her, out she ran to Sir Gawain, who, when she arrived, stood to receive the little guest.

“Sir,” she said, “God is my witness: you are the first man I have spoken to alone. My governess tells me that speech is the garment of the mind; I hope mine will show me to be modest and of good breeding. It is only the greatest distress that brings me to this. I hope you will let me tell you what it is.

“You are really I and I am you, though our names are different. I shall give you now my name, and that will make you both maid and man, so that I shall be speaking both to you and to myself. Sir, if you wish it, I will give you my love with all my heart; and if you have a manly heart, you will serve us both well for my reward alone.”

Gawain thought of how Parzival had said it was better to trust a woman than God, and gave the little lady his word.

“Into your hands I give my sword,” he said. “When I am challenged, it will be you who ride for me. Others will think they see me, but I shall know they see you.”

“That will not be too much for me to do,” she said. “I shall be your protection and shield.”

“Lady!” said he, and her little hands now lay clasped between his own. “Now I live at your command, and by the gift of your comfort and love.”

“Sir,” she said, “I must now leave you; for there is something more I must do. I must arrange my token. If you wear it, no knight will be greater in fame.” And with her playmate, the burgrave’s little daughter Clauditte, she ran off.

“What a gallant and good man!” the Duchess said when the story had been told. They made the child a new dress of golden silk, of which they took one sleeve and gave it to her playmate to carry to Gawain, who immediately, in delight, nailed it to one of his three shields.

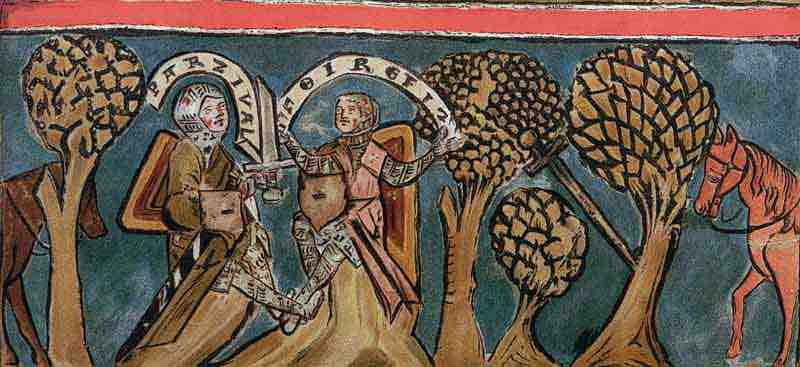

Next day, like splitting thunder, with a sound of cracking spears, the great voice of battle rose, and Gawain rode to the attack, overthrowing swiftly two young lords. When, however, he heard the Duke Astor of Lanverunz shout the battle cry, “Nantes,” of the knights of the Round Table and saw on a shield among his men the coat of arms of Arthur’s son, he wheeled away and left that army, riding to attack the other, of King Meljanz, whom he unhorsed and bound to the service of Obilot. Parzival was elsewhere on the battlefield, clashing with the champions of Duke Lyppaut’s brother, while the duke himself was engaged with Poydiconjunz: and Gawain, returning to assist him, struck down the rude Meljacanz, whom Astor, however, rescued. So that the day of battle ended with King Meljanz a captive and the best deeds of the day having been performed in the name of Obilot.

Nor did Gawain fail to receive a kiss when they asked him to take his lady in his arms. He pressed the pretty child like a doll to his breast and, summoning King Meljanz, bound him to her service. Whereafter Lady Love, with her powerful art, old yet ever young, waked love anew — and as to how the wedding of that humbled king with Obilot’s elder sister went, ask those who there received gifts. Gawain himself departed. His little lady wept bitterly. Her mother could scarcely get her away from him, and he rode into the forest with a heavy heart.

BOOK VIII: THE WILLING QUEEN OF ASCALUN

“Now help me lament Gawain’s woes!” the poet writes. High ranges and many moors he crossed, then saw approaching, before a mighty castle, an army of some five hundred knights out hawking. On a tall Arabian steed from Spain, their king, Vergulaht of Ascalun of the race of the fairy hills, (Ascalun, Avalon: Gawain’s adventures generally are transformations of Celtic visits to the fairy hills.) shone like day in the midst of night. However, when he wheeled to pursue and rescue a falcon that with its prey had dropped into a pond, his Arabian stumbled and he was hurled into the wet — at which moment, up rode Gawain, to ask the way to Schanpfanzun.

“You see it before you,” said the king. “My sister is there, but if you will permit, I shall continue here a while longer. She will care for you till I come, and you will not be sorry if I tarry.”

The reader familiar with the fourteenth-century Sir Gawaine and the Green Knight will have guessed that we are approaching here a variant of its temptation scene,Note 14 at the opposite range of Gawain’s spectrum from his affair with tiny Obilot.

The castle was immense; the lady, beautiful. “Since my brother has so highly recommended you,” she said, “I shall kiss you if you like. But you must let me know what I am to do, according to your own rules.” She was standing there with all charm.

“Lady, your mouth,” Gawain said, “looks to me so kissable, I will have that kiss of greeting.”

The mouth was hot, plump, and red. Upon it Gawain affixed his own, and there took place a kiss that was not of the sort recommended for greeting guests. She and her well-born guest sat down. Sweet talk, quite frank, ensued, which advanced rapidly to a point where she could only repeat a refusal and he an unchanging plea.

“Sir,” she said, at last, “if you know what you are doing, you will realize that I have already gone far enough. Besides, I don’t even know who you are.”

“I am my aunt’s brother’s son,” he answered, “of a line high enough to match yours; so that if you’d like to grant that favor, don’t let our ancestors prevent you.”

The waiting maid who had been pouring their drink disappeared, and some other ladies who had been sitting there did not forget they had things elsewhere to attend to. The knight who had escorted Gawain also was out of the way. And he, then reflecting that even a badly wounded eagle may catch a big fat ostrich, reached his hand beneath her mantle, “and I think,” states the poet, “touched her hip” — which only increased his anguish. They were in such distress of love that something very nearly happened. Both the man and the maid were ready for it, when alas! their hearts’ sorrow arrived! A white-haired knight came to the door and, on perceiving Gawain, set up a loud halloo of war, “Alas and hey hey for my master,” he cried, “my master, whom you murdered! And now you would rape his daughter!”

People usually answer a call to arms, and so it happened now. Here a knight appeared; there, a merchant. They heard the rabble coming from the city.

“Lady,” said Gawain, “let me now know your advice! If I only had my sword!”

“Let us fly into that tower,” she said. “It’s the one next to my chamber.” And the two made for the door.

Gawain yanked from the wall the bar to lock the tower, and, wielding this, held the door while his lady ran upstairs. Above, she rushed about for a weapon of some sort, found a beautifully inlaid chessboard with its pieces, and brought these down to Gawain, who used that square board for a shield while the queen, behind him, flung the kings and rooks, and (as our story tells) they were heavy, so that those whom they hit went down. Like a knight that mighty lady fought, and no market woman at carnival time ever offered battle more warlike. A female soiled with armor-rust soon forgets what is seemly. And all the while, giving battle, she was in tears.

But Gawain? Every chance he got, he turned to have another look at his queen. You never saw on a spitted hare a better shape than hers. Between hips and breast, where the belt went round, no ant had ever slimmer waist. Every time Gawain had a fresh sight of her, more attackers lost their lives.

Then the king arrived, Vergulaht. He saw that battle, how it stood; “and I am afraid,” interjects the poet, “that I am now going to have to let you hear that a king there disgraced himself in his handling of a guest.” Gawain had to stand waiting until Vergulaht donned his armor, then he fell back, retreating up the stairs.

However, at this juncture the noble Prince Kingrimursel appeared, who at the field banquet of Arthur had challenged Gawain to this journey. And when he saw what was going on, he tore his hair in distress, for he had guaranteed on his honor that Gawain should come in peace until met in single combat on the field. He beat the rabble back from the tower, cried to Gawain to let him come fight by his side, and the two escaped to the open.

The king’s counselors persuaded him first to proclaim an armistice, and then to make up his mind how his father was to be avenged. The battlefield became still. The lady appeared from her tower, kissed her cousin, Kingrimursel, on the lips for having rescued Gawain, and turned upon the king, her brother:

“Modesty and good manners were the only shield I had,” she said, “to protect myself and the knight you sent to me. You have done me a grievous wrong. Furthermore, I had always heard that when a man turns for protection to a lady his opponent should give up the combat. The flight of your guest to me, King Vergulaht, is going to do your reputation no good.”

The prince accused him too. “I gave Gawain guarantee. You betrayed him, and I too, therefore, have suffered affront. My fellow princes all will look into this. If you cannot honor princes, we shall not respect your crown.”

There were some further verbal exchanges, but the upshot of it all was that while the lady — her name was Antikonie — that evening entertained Gawain and Kingrimursel with a dinner of wines, pheasant, partridge, fish, and white bread, served by beautiful maidens — all slim-waisted as ants — the king, meeting with his counselors, told of a battle he had lately fought with a powerful knight in the forest who had sent him flying from his steed and made him swear to procure for him the Grail within a year. “And if I fail I must go to Queen Condwiramurs and pronounce an oath to her of submission.”

The counselors then agreed that since Gawain was in Vergulaht’s grasp, flapping his wings in his trap, the king should turn the Grail task over to him. “Let him rest for the night,” they suggested, “and let him hear of this in the morning.”

So when Mass had been said, and the lady with her two knights appeared, a wreath of flowers in her hair of which no rose was redder than her lips, King Vergulaht begged his guest to help persuade his sister to forgive him. “And I will then forgive you my heart’s sorrow for my father — provided,” he added, “that you swear to me without delay you will seek for me the Grail.”

Thus all were reconciled, and, breakfast having ended, Gawain’s time came for departure. The queen approached without guile, spoke adieu, and her mouth again kissed his. “I think,” states the poet, “they were both very sad.” Then his pages brought his steeds, and he mounted Gringuljete (his white fairy horse with shining red ears) and in quest of the Grail for King Vergulaht of Ascalun rode away.

IV. Illuminations

BOOK IX: THE GOSPEL OF TREVRIZENT

“Open up, now, my heart,” writes the poet, “to the knock of Lady Adventure! Let us hear how fares that noble knight whom Cundrie, with her harshest words, sent questing for the Grail. Has he yet seen Munsalvaesche?”

The book of his adventure tells that as he rode one day in the forest — “I know not at what hour” — God took thought for his guidance, and he spied among the trees a hermit’s hut. Within was a hermitess, kneeling over a coffin, and the knight, hoping for direction, called, “Is anybody in?” She responded, and when he heard a woman’s voice he quickly turned his mount away and, while she was rising, left his horse, shield, and sword by a tree.

She wore a hair shirt beneath a gray gown, but wore also a garnet ring. “May God reward you for your greeting, as He rewards all courtesy,” she said as she came to sit beside him on a bench, where he asked concerning her life. “My food is from the Grail,” she said. “Cundrie brings it, the sorceress, on Saturdays, for the week.” And that seeming to him an unlikely tale, he indicated the ring.

“I wear this,” she explained, “for a man beloved, whose love, in the way of human love, I never knew. And I have worn it since the day the lance of the Duke Orilus struck him dead. I am unmarried and a maid; yet in God’s sight he is my husband, and this ring is to go with me before God.”

Then he realized that the woman was Sigune.

Grief pressed his heart; he removed his helm and she looked hard into his face. “Parzival! It is you!" Her manner became very hard. “How do you stand now with the Grail? Have you learned its meaning yet?”

“It is cruel of you, my cousin, to bear me such ill will,” he replied. “I have lost in these years all joy because of the Grail. We are kin, dear cousin. I behaved there as one bound to be a loser. Give me counsel.”

She answered more kindly. “May the hand of Him now help you, to Whom all sorrow is known. You may succeed yet in finding a track that will take you to Munsalvaesche, for Cundrie has just now gone that way. Her mule stands over there when she comes, where the spring flows from the rock. I suggest you follow Cundrie; she may not be far ahead.” (Compare again Eliot, The Waste Land: “If there were rock/And also water/And water/A spring/A pool among the rock” (lines 348–52).)

He thanked her and mounted; but the fresh track soon was lost, and there came riding at him instead a bareheaded knight in shining mail and rich surcoat, shouting at him to get out. “Munsalvaesche allows no one this close who is not prepared either for battle,” he cried, “or else for that transformation that in the world outside this forest is called death.” The knight donned his helmet, which he carried in his hand, and Parzival, charging, struck him just above the shield and sent him rolling down a ravine. Parzival’s steed went over too, but himself quickly catching a cedar branch, he dangled there until, groping with his feet, he found a rock. Below, his great Castilian lay dead, but the Temple Knight was scrambling up the other slope, and his mount, not far from Parzival, was standing with its feet tangled in the reins.

Mounting and now missing nothing but his spear, Parzival again was riding without aim, and so for weeks on end, until one morning when a light snow had fallen — just enough to be chill — he chanced upon a file of pilgrims, barefoot, all in rough gray cloaks. In the lead were a white-haired nobleman, his wife, and their two daughters, the ladies with little dogs trotting at their sides; and these were followed by a troupe of squires and knights, also in pilgrim garb. Said the leader as he passed, to the armored horseman, who had turned his steed out of their path: “I am shocked to see you mounted on this day, and not barefoot, like ourselves.” To which the mounted Parzival answered, “Sir, I do not know what day this year began, how many weeks have passed, nor what day this is of the week. I used to serve someone named God, until His mercy condemned me to shame.”