SHRINKING PIE:

COMPETITION AND RELATIVE

GROWTH IN A FINITE WORLD

...[C]ommerce is but a means to an end, the diffusion of civilization and wealth. To allow commerce to proceed until the source of civilization is weakened and overturned is like killing the goose to get the golden egg. Is the immediate creation of material wealth to be our only object? Have we not hereditary possessions in our just laws, our free and nobly developed constitution, our rich literature and philosophy, incomparably above material wealth, and which we are beyond all things bound to maintain, improve, and hand down in safety? And do we accomplish this duty in encouraging a growth of industry which must prove unstable, and perhaps involve all things in its fall?

— William Stanley Jevons (economist, 1865)

Is the central assertion of this book — that world economic growth is over — already disproved? How else to explain China’s continued exuberant expansion, or signs of recovery in the US in 2010?

As stated in the Introduction, I am asserting that real, aggregate, averaged growth is essentially finished, though we may still see an occasional quarter or year of GDP growth relative to the previous quarter or year, and will still see residual growth in some nations or regions. The point can be summarized in a single sentence, but it bears reiterating and unpacking because there are several kinds of relative growth, and the competitive pursuit of advantage within a global economy that, overall, is shrinking rather than growing will powerfully shape political, geopolitical, and social developments for the next few decades.

In this chapter we will explore the growth prospects of the Asian economies. We will also examine the dynamics of currency wars. And we will see how rich and poor countries, and demographic sectors within those countries, are likely to fare in post-growth economy, and how increasing competition for depleting resources may drive nations toward conflict.

The best place to start this survey of prospects for short-to-medium-term relative growth is with China, which not only exemplifies rapid residual economic growth, but also points the way to how currency and resource rivalries, as well as old/young, rich/poor, urban/rural divisions might play out as the global economy contracts.

The China Bubble

If one were looking for a single arguing point against the idea that world economic growth is ending, China would almost certainly be the best choice. New Chinese cities are springing up in mere months. A stop-motion–video posted on the Internet last year showed a 15-story hotel being built in six days.1 A new coal power plant opens, on average, every four days. Twenty million Chinese move from the countryside to cities each year. Because city dwellers contribute 20 times as much per capita to GDP, urbanization alone accounts for half or more of China’s 10 percent annual GDP growth. China is building highways faster than any other nation, and its motorists are now buying around 13 million automobiles per year, versus 11 million annually in the US — which had been the world’s largest market for cars since the days of the Model T. It’s all happening blindingly fast. Indeed, in both its scale and speed, the expansion of the Chinese economy is unprecedented in world history.

But how long can this go on? Will China escape the economic fate of older industrial nations, or is it poised for its own encounter with growth limits? There are four reasons for thinking current trends cannot be sustained.

1. Resource Depletion and Resource Competition:The Story of China’s Coal

China’s appetite for resources and raw materials is driving up worldwide prices of a wide range of commodities including oil, iron, copper, cotton, cement, and soybeans. But for the Chinese economy, perhaps the single most important resource is coal. Indeed, it may not be an oversimplification to say that the fate of China’s economy rests on its ability to maintain growth in coal supplies.

China relies on coal for 80 percent of its electricity and 70 percent of its total energy; coal also supports China’s steel industry, the world’s largest. Altogether, China is one of the most coal-dependent nations in the world. In order to become the world’s second-largest economy, it has had to more than double its coal consumption over the past decade, so that it is now using nearly half of all coal consumed globally, and over three times as much as is consumed in the next nation in line, the US (which prides itself on being “the Saudi Arabia of coal”).

As China energy expert David Fridley and I argued in a recent op-ed in Nature, while China claims it has enough coal to fuel continued economic growth, that claim is questionable.2

The nation has recently updated its proven coal reserves to 187 billion metric tons, putting it second in line after the US in terms of supplies. That would be about 62 years’ worth of coal at 2009 rates of consumption (over three billion tons per year). But this simple “lifetime” calculation is highly misleading.

Reserves lifetime figures are calculated on the basis of flat demand and lose meaning if demand grows over time. China’s coal consumption is accelerating rapidly, so that the expected “62 years’ worth” must be adjusted downward. Demand forecasts from China’s Energy Research Institute would reduce the reserves lifetime to about 33 years; but if coal demand were to grow in step with projected Chinese economic growth, the reserves lifetime would drop to just 19 years.

Yet this still doesn’t capture the situation. Production will peak and decline long before China’s coal completely runs out. Further, as with oil production, coal mining proceeds on the basis of the “best-first” or “low-hanging fruit” principle, so we must assume that China is extracting its highest-quality, easiest-accessed coal now, leaving the lower-quality and more expensively mined coal for later. Unlike the US, China does not have vast deposits of surface-minable coal; over 90 percent of China’s coal comes from underground mines up to 1,000 meters in depth, and those mines face increasing engineering challenges.

Hubbert analysis, which has been used to forecast oil production peaks, can also be applied to forecasting future coal supplies. In 2007, Chinese academics Tao and Li forecast that China’s coal production will peak and start to decline perhaps as early as 2025.3 Other forecasts are more pessimistic. A 2007 analysis by the Energy Watch Group of Germany forecast a peak of production in 2015 with a rapid production decline commencing in 2020.4 And a 2010 study by Patzek and Croft forecast the peak of world coal production for this year (2011); they see China’s coal peak also occurring essentially now.5

China has few options for reducing its reliance on coal, since the fuel is used in so many ways. In addition to powering the electricity and steel sectors, coal provides winter heat to hundreds of millions of northern Chinese; it is also used in the cement, non-ferrous metals, and chemicals industries. While China is rapidly expanding its supply of natural gas, to replace just the coal used for heating would double total gas consumption.

China is quickly developing alternative energy sources. But can these be brought on line fast enough to make a difference? Let’s do some numbers. China aims to have 100 gigawatts (GW) of wind power capacity by 2020, and the nation’s leaders plan to expand installed solar capacity to 20 GW during the same period. These are truly astonishing goals, and, if China even comes close to accomplishing them, it will become the world’s renewable energy leader. But there is a problem. Total Chinese electricity generation capacity is 900 GW currently; with seven percent growth, that means the nation’s electricity demand in 2020 will be something like 1800 GW. Wind and solar together would supply less than seven percent of that. The only thing likely to boost that percentage much would be a dramatic reduction in growth of energy demand to, say, two percent annually.

The situation with nuclear power is similar: China has 11 atomic power plants now and is in the process of building 20 more, with a target of 60 GW of generating capacity, or possibly more, by 2020. But this will supply only between three and five percent of total electricity demand, depending on energy demand growth rates. In late 2010, energy policy makers in Beijing evidently began to take notice of the looming electricity supply problem, and rumors circulated of new efforts to construct up to 245 new nuclear plants over the next two decades (the US has only 104 in total). If this new target is real, and if the Chinese succeed in achieving it, a large fraction of new electricity demand for the coming years could be met through sources other than coal — but China would still have an enormous (though more slowly growing) coal dependence to feed. Meanwhile, China’s soaring demand for uranium would push up global prices for this energy mineral.6

In 2009 China was a substantial net importer of coal, having been a net exporter every year through 2008.7 China could import more coal to enable further growth, but the biggest exporters of coal — Australia, Indonesia, and South Africa — have much smaller reserves and production rates. The entire seaborne trade in steam coal (mainly used by power plants) currently amounts to only 630 million tons per year, and China could absorb this much with only three years of continued growth in coal demand. That’s not going to happen, though: Other nations need that export coal, too — including India, also major coal-based economy, and also a country needing to import increasing amounts of fuel.

The conclusion is unsettling but inescapable: China’s reliance on coal cannot be significantly reduced as long as its demand for electrical power continues to grow at anything like current rates. And even if energy demand growth tapers off and alternative energy sources come on line quickly, the country’s ability to supply enough coal domestically will still be challenged. This will drive up coal prices worldwide, while choking off economic growth at home. China’s energy economy is unsustainable and will cease growing in the foreseeable future, impacting many other nations as it does so.

2. Export-Led Development Model

The fundamental economic model that China has depended on for the past couple of decades was borrowed from Japan, and consists of producing low-cost export goods to fund investment at home. Essentially the same model is being pursued by Thailand, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, and Indonesia. The story of what happened to Japan as a result of following this strategy should be a cautionary tale for its neighbors, and for Beijing in particular.8

The post-war Japanese export boom resulted in spectacular growth for four decades, but the undervalued yen eventually caused a deflationary contraction of Japan’s economy, which is smaller today than it was in the late 1990s. There are good reasons to think the same policies will achieve the same results in China. However, China is much larger than Japan, and the world economy is today far more fragile than it was in the late 1980s when the Japanese bubble burst, so the global consequences of a Chinese crash would be far greater.

After World War II, Japan kept its yen weak, making exports relatively cheap to foreign buyers. Japan also benefited from a high savings rate, which enabled massive investment in infrastructure and manufacturing capacity. The country’s GDP ballooned by 600 percent from 1950 to 1970, pulling more people out of poverty more quickly than had ever been done anywhere previously.

Export- and investment-driven growth typically discourages consumption, as domestic prices are kept high and salaries low (to help fuel exports). In the case of Japan, yields on savings were suppressed so that available capital would flow to corporations and the government.

All of this resulted in a lopsided economy. In most modern market economies, consumption accounts for around 65 percent of GDP (in the US, the proportion is 70 percent), while investment in fixed assets such as infrastructure and manufacturing capacity makes up 15 percent. In 1970, Japan’s domestic consumption contributed 48 percent of the economy and fixed investment 40 percent. As Ethan Devine put it in his article “The Japan Syndrome” in Foreign Policy, “In plain English, the Japanese were consuming relatively little while investing heavily in steel plants and skyscrapers, which didn’t leave much for fish or tourism. Belatedly, Tokyo realized that a balanced economy must also have consumption and that coating the country with factories and infrastructure wouldn’t do the trick.”9

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Japan gradually strengthened the yen so as to support the development of a consumer culture, and consumption rose to more than half of GDP. In 1985, Tokyo let its currency appreciate more rapidly. But the result was simply a spectacular inflation of real estate and stock prices. The bubble’s collapse lasted more than a decade, with stock prices scraping bottom in 2003 (before plummeting even further after the commencement of the current global crisis in 2008). Export-oriented industries could not adapt to a domestically led economy because there was insufficient consumer demand. And so rapid growth turned to stagnation, which has persisted up to the present.

Japan still runs on exports, but now government spending is an essential prop for the economy. Twenty years of fiscal stimulus have done little more than stave off even more serious economic contraction, while government debt has grown to nearly 200 percent of GDP.10

Fast forward to China, 2011. Like Japan, China subsists largely on exports while investing heavily in infrastructure, paying for the latter with private savings that come from tamping down consumption. Beijing adopted the Japanese growth model in the 1990s, when its deregulation and opening up of the country’s economy was widely praised. While these policies created tens of millions of jobs, as well as thousands of new roads and millions of new buildings, they have also generated imbalances reminiscent of Japan in the 1980s — except that in many ways China has gone even further out on a limb.

Devine recites the startling numbers:

China is far more dependent on exports and investment than Japan ever was, and the numbers are still moving in the wrong direction. Investment accounts for half of China’s economy while consumption is only 36 percent of GDP — the lowest in the world, drastically lower than even other emerging economies such as India and Brazil. But as the Japan example illustrates, low consumption leads to high savings, and China’s thrifty citizens, coupled with booming net exports, have bestowed upon the country the world’s largest current account surplus, triple that of Japan’s in 1985.11

China’s legendary trade surpluses cause problems for its trading partners while stoking price inflation at home. And inflation, the usual result of an undervalued currency, is dangerous in a country where hundreds of millions of people still have trouble affording basic essentials.

To outsiders, China has looked like a shining example of what growth can accomplish, yet it has achieved its success by strangling personal consumption (which was the engine of growth in the US and Europe) and sidelining small-scale entrepreneurs in favor of state-owned businesses and selected multinational corporations. Only a small percentage of its population has shared in the bounty.

China’s leaders are aware of the pitfalls of pursuing the Japanese development model, and have issued a comprehensive slate of reforms to foster consumption and curb excessive capital investment. But these efforts will only work if the US and the rest of the world return to a path of growing consumption. If not, China’s choices may be limited. An export-driven economy can only succeed if others can afford to import.

3. Demographics: Old/Young, Rich/Poor, Urban/Rural

Beijing’s one-child policy, introduced in 1979, was largely effective — though it had the abhorrent side effect of encouraging a disdain for female infants, a prejudice that has led to abortion, neglect, abandonment, and even infanticide. Applying mainly to urban couples of Han descent, the policy reduced population growth in the country of 1.3 billion by as much as 300 million people. This meant that by the 1980s and ’90s, young workers had fewer dependents to support — and China’s manufacturing boom drew strength from young people moving from country to city to work in factories. For the nation as a whole, having a few hundred million fewer mouths to feed has acted as a social safety valve so far, and will reduce misery in the decades ahead as world resources deplete and human carrying capacity disappears.

However, there is a demographic price to pay. Beginning in 2015, China will see a growing number of older citizens relying on a shrinking pool of young workers.

Most of the nation’s factories are located in its coastal cities, of which some, like Shenzen, were built from scratch as industrial centers. Shenzen hosts the Foxconn Technology Group, an electronics manufacturer that makes components for Dell, Hewlett-Packard, and Apple; nearly all its workers are under 25.

China’s older workers have largely been left behind in rural villages, or pushed from their urban homes into apartment blocks on cities’ outskirts to make way for new apartments and office buildings occupied by younger urbanites and the companies hiring them. Age discrimination is a fact of life.

All of this will gradually change as China’s work force ages. Within a generation, the average age of a Chinese worker will be higher than that of an American worker.12 One of China’s leaders’ biggest fears, expressed repeatedly in public pronouncements, is that the nation will grow old before it grows rich (Japan, in contrast, got rich before it grew old).

To avoid this fate, China is trying to grow its economy as fast as possible now, while it still can.

One way it does this is to offer paltry pensions and poor-quality healthcare to older citizens. This makes China an attractive place for foreign corporations to do business. In the US, healthcare costs for older workers are often double the costs for workers in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. By keeping its workforce young and denying them benefits, China’s leaders keep costs down. American or European companies that move production to China or buy Chinese goods gain leverage to rewrite terms of employment with their older workers at home — or they can simply shut down domestic factories.

China’s youthful labor force attracts foreign investment. But as the country’s work force ages, its competitive advantage may evaporate. Moreover, the lack of adequate pensions and healthcare for Chinese workers will eventually result in worsening social stresses and strains.

It is the financial sacrifices of its people that have given China the opportunity to attract capital investment to its industries, and that generate subsequent profits that are then loaned back to the United States and other industrialized nations.

To understand the significance of those sacrifices, one must understand a little of the country’s recent history. At the end of the Communist revolution in 1949, China was impoverished and war-ravaged; the overwhelming majority of its people were rural peasants. Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong set a goal of bringing prosperity to the populous, resource-rich nation. A period of economic growth and infrastructure development ensued, lasting until the mid-1960s. At this point, Mao appears to have had second thoughts: concerned that further industrialization would create or deepen class divisions, he unleashed the Cultural Revolution, lasting from 1966 to the mid-1970s, when industrial and agricultural output fell. As Mao’s health declined, a vicious power struggle ensued, leading to the reforms of Deng Xiaoping. Economic growth became a higher priority than ever before, and it followed in spectacular fashion from widespread privatization and the application of market principles. “To get rich is glorious,” Communist officials now proclaimed.

During the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, the Chinese people had worked hard and endured grinding poverty for the good of the nation. But in the 1990s a small segment of the populace — mostly in the coastal cities — began to enjoy a middle-class existence. Some Chinese were indeed becoming gloriously rich, while most remained mired in extreme poverty. The resulting wealth disparity is only bearable as long as the middle class continues to expand in numbers, offering the promise of economic opportunity to hundreds of millions of destitute peasants in the rural interior.

China’s central government has unleashed a firestorm of entrepreneurial, profit-driven economic activity that is both unsustainable and difficult to control. Meanwhile, as we have seen, the uncontrollably dynamic economy is export-dependent and ill suited to meeting domestic needs.

China has encouraged rapid export-led, coal-fired economic growth, perhaps as a way of putting off dealing with its internal political, demographic, and social problems. If that is indeed Beijing’s strategy, it has worked spectacularly well for a short while. But it is built on contradictions and false hopes. Over the course of the current decade, the Chinese demographic-economic strategy will likely begin to unravel. What happens next is anybody’s guess.13

4. Oh No — Not Another Real Estate Bubble!

There is one more similarity between Japan and China that is worth mentioning. During the 1980s, real estate prices in Tokyo were jaw-dropping. In the Ginza district in 1989, choice properties fetched over 100 million yen (approximately $1 million US dollars) per square meter, or $93,000 per square foot. Prices were only slightly lower in other major business districts in the city. By 2004, values of top properties in Tokyo’s financial districts had plummeted by 99 percent, and residential homes were selling for less than a tenth their peak prices. Tens of trillions of dollars in value were wiped out with the combined collapse of the Tokyo stock and real estate markets during the intervening years.

Once again, China is following in Japan’s footsteps. Massive real estate projects — houses, shopping malls, factories, and skyscrapers — have been proliferating in China for years, attracting both private and corporate buyers. As prices have soared, investors have turned into speculators, intent on buying brand-new properties with the intention of flipping them.

Building is being driven by artificially inflated demand — the very definition of a bubble. And this is resulting in oversupply. In city after city, acres of commercial space sit vacant. Indeed, whole cities intended for millions of inhabitants have been built in the Chinese interior and now stand all but empty.14 Some might argue that the Chinese are investing in infrastructure now in anticipation of many millions more citizens moving into urban centers over the coming decades — however, this presupposes continuing rapid economic growth, which is exactly what is in question. If growth sputters, this infrastructure overbuild will be a dead weight on the Chinese economy.

Though Beijing initiated an effort to cool the real estate and stock markets in 2008, the global financial crisis forced officials to relent in favor of lavish stimulus spending on shovel-ready infrastructure projects. The Chinese funneled 4 trillion yuan (about $590 billion) into what in many cases turned out to be yet more empty new shopping malls, empty new cities, and empty new factories.

For Chinese citizens, investment in the stock market hardly makes sense, given dramatic episodes of turbulence in recent years. Instead, a condominium or a house is seen as the most sensible and profitable investment. But this results in a bidding up of prices to the point where, in major cities like Beijing and Shanghai, a condo can cost 20 times a worker’s annual salary. A worker in Tokyo might expect to pay only eight times her annual wages for a similar property.

What are the chances of putting off a property price meltdown? According to a November, 2010 article by Wieland Wagner in the German magazine Der Spiegel,

Cao Jianhai of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing likens the Chinese economy to “a volcano before an eruption.” Nevertheless, he doesn’t believe that the government of Hu Jintao, the Communist Party leader and president, and Prime Minister Wen will allow a crash to occur before its term in office ends in 2012 — local governments are too dependent on the real estate boom. According to Cao, Beijing will go to “any expense” to pump money into the financial system and spur a renewed surge of rapid economic growth.15

Once Hu and Wen are gone, however, it will be up to their successors to deal with the fallout from a housing crash.16

Economic Growth’s Last Stand?

China is no more able to sustain perpetual growth than any other nation. The only questions, really, are when its growth will stall, and by what pace and to what degree its economy will contract.

The property bubble is likely to be China’s biggest short-term problem, and it could have knock-on effects on the nation’s banking system. The bubble could start to deflate as soon as next year, or the year after. Beijing will do what it can to prop up growth and tamp down social strain, and this could buy another couple of years — though there is no guarantee that the effort will succeed.

Over the longer haul (the next 2–10 years), China’s greatest vulnerabilities are in the areas of energy, demographics, and the environment (water, climate, and agriculture). By the period 2016 to 2020, problems in these areas will accumulate and become mutually exacerbating, and it will eventually be impossible for China’s leaders to plug all the leaks in the dike.

Already, China’s social structure is stressed, as can be seen from the many regional rebellions that take place each year (but that go mostly unreported in world media). This is the main reason the central government is ruthless with respect to press and Internet freedoms and other civil liberties.

Talk to a businessperson from China and you may hear how the continued expansion of the Chinese economy is inevitable and unstoppable. But peer beneath the surface and you will see roiling, boiling ferment.

We have discussed China at some length, not only because it has become the world’s second-largest national economy and is the world’s foremost energy user, but because it is emblematic. India, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam are each pursuing somewhat different paths toward the same grail of rapid economic growth, but their strategies and vulnerabilities are sufficiently similar that an understanding of China’s predicament provides useful context for gauging these other countries’ prospects.

China is likely the site of world economic growth’s last stand. This nation, together with the other Asian “tigers,” comprises the main engine of expansion that remains after the faltering of the older, more established economies in North America and Europe. When China sputters, the quickening slide of the global economy will be clear and obvious to everyone.

BOX 5.1 Is China Planning for the End of Growth?

China’s new national 2011–1015 economic plan — which is essentially also its green blueprint — was finalized by the People’s Congress in March 2011. The plan focuses on quality of development rather than on quantity only, with the goal of making the nation’s economy less carbon-intensive and more resource-efficient through top-down mandates and regional pilot projects.

Beijing’s 2010 energy efficiency goal was stringently enforced so that the nation would reach its target to decrease energy consumption per unit of GDP by 20 percent compared to 2005. As 2010 was winding down, some Zhejiang provincial officials tried to make their final five-year plan energy efficiency goal by enforcing rolling blackouts, turning off power at various times for days on end.

The new five-year plan prioritizes investments in renewable energy, information and communications technologies, advanced transportation and materials, water supply and treatment technologies (including using plants for bioremediation), and air and water quality.

China’s move to become more of a service economy is likely inspired partly by a dawning awareness of limited resources and limited consumer demand in the West. Resource and energy efficiency and the shift to renewable energy sources may be driven by looming coal limits and rising oil prices. If leaders in Beijing are planning for less growth, it may be because they are beginning to recognize that current growth rates cannot be sustained. The strategies they are beginning to put in place are sensible from both an economic and an environmental standpoint. The question is: Can China’s leaders put the brakes on growth fast enough to avoid looming obstacles, yet gradually enough to maintain control?17

Currency Wars

Since the economic crisis began, stresses in trade between the US and China have led to unfriendly official comments on both sides regarding the other nation’s currency. Some financial commentators suggest that “currency wars,” which might also embroil the European Union and other nations, may be in the offing, and that these could eventually turn into trade wars or even military conflicts. The US dollar, as the world’s reserve currency and as the national currency of the country leading the world into the post-growth era, appears to be central to these “money wars.”

It takes a little history to understand what currency conflicts are about.18 Prior to the 20th century, most national currencies either consisted of gold or were tied to gold; therefore the currency of one nation was fairly easily convertible to that of another. National monetary reserves consisted of gold, and balance of payments deficits were settled in gold. Limited supplies of gold kept public spending within fairly tight bounds. Inflation through the debasement of a currency resulted in the refusal of other nations to accept that currency in trade. Typically the financing of wars presented the only exigency strong enough to overcome disincentives to debase money.

World War I, a conflict that engulfed at least 17 nations, was the first occasion when several countries simultaneously abandoned a hard money policy. Britain took on long-term war loans while Germany issued short-term bonds. Deficit financing arguably prolonged the war, resulting in millions of needless casualties.

Though Germany had entered the war with a thriving economy, its short-term debt, compounded by the harsh post-war terms of the Versailles Treaty, resulted in economic ruin through hyperinflation, leading to the destruction of its middle class and to the rise of Hitler, setting the stage for World War II.

At the Conference of Genoa in 1922, a partial return to the gold standard came about as the central banks of the world’s powerful nations were permitted to keep part of their reserves in currencies (including the US dollar) that were directly exchangeable by other governments for gold coins. However, under this new Gold Exchange Standard, citizens could not themselves redeem national banknotes for gold coins. Now dollars and pounds were effectively equivalent to gold for the currency issuer, but not for most currency holders. This was an inherently inflationary development from a monetarist point of view (in that it meant that money could be issued substantially beyond the amounts of gold on deposit); however, the world’s growing energy supplies and manufacturing capacity required an increase in the money supply, so for most countries and in most years measurable rates of price inflation remained relatively low.19

As World War II neared its end, Japan and the European powers lay in ruins; the United States was relatively unscathed. At the Bretton Woods monetary conference of 1944 the Allied nations laid the groundwork for a postwar international economic system that included new institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which today is part of the World Bank. The US would assume a dominant role in these institutions, and the (partially) gold-backed dollar became, in effect, the world’s reserve currency. Throughout the next half-century and more, citizens and businesses in nations around the world — even in the Soviet Union — who wanted a hedge against instability in their own national currency would hoard US greenbacks.

In the early 1970s, as the US borrowed heavily to finance the Vietnam War, France insisted on trading its surplus dollars for gold; this had the effect of emptying out US gold reserves. President Nixon’s only apparent option was to ditch what remained of the gold standard. From then on, the dollar would have no fixed definition, other than as “the official currency of the United States.”20

After 1973, many currencies kept a fixed exchange rate with the dollar. As of 2008, there were at least 17 national currencies still pegged to the US currency, including Aruba’s florin, Jordan’s dinar, Bahrain’s dinar, Lebanon’s pound, Oman’s rial, Qatar’s rial, as well as the Saudi riyal, –Emirati dirham, Maldivian rufiyaa, Venezuelan bolivar, Belize dollar, Bahamian dollar, Hong Kong dollar, Barbados dollar, Trinidad and Tobago dollar, and Eastern Caribbean dollar.

While the US dollar now had no gold backing, in effect it was being backed by the oil of several key Middle East petroleum exporting nations, which sold their crude only for US dollars (thus creating and maintaining a worldwide demand for greenbacks with which to pay for oil) and then deposited their enormous earnings in US banks, which in turn made dollar-denominated loans throughout the world — loans that had to be repaid (with interest) in dollars.21

Meanwhile exchange rates for most currencies (including those of the European countries) floated relative to one another and to the dollar. This provided an opening for the emergence of the foreign exchange (ForEx) currency market, which has grown to an astonishing four trillion dollars per day in turnover as of 2010.

In 1999, most members of the European Union opted into a common currency, the euro, that floated in value like the Japanese yen. One of the motives for this historic monetary unification was the desire for a stronger currency that would be more stable and competitive relative to the US dollar.

For decades, China has been one of the countries that kept its currency pegged to the dollar at a fixed rate. This enabled the country to keep its currency’s value low, making Chinese exports cheap and attractive — especially to the United States.

However, for smaller countries, fixed exchange rates have meant vulnerability to currency attacks. If speculators decide to sell large amounts of a country’s currency, that country can defend its currency’s value only by holding a large cache of foreign reserves sufficient to keep its fixed exchange rate in place. This reserve requirement effectively ties the country’s leaders’ hands during the attack, preventing them from spending (for example, to prop up banks); if the pegged exchange rate is abandoned under such circumstances, the currency’s value will plummet. Either way, the nation faces the risk of economic depression or collapse — as occurred in the cases of the recent Argentine and East Asian financial crises.

Altogether, the world’s currencies could hardly even be said to comprise a coherent “system”: harmony and functionality are maintained only at great cost (with most of that cost ending up as profits to currency traders and speculators). But as world economic growth shifts into reverse, stresses within the global community of currencies may become unbearable.

With its enormous levels of public and private debt and its continuing trade deficits, the US has something to gain from a lower-valued dollar. This would make its export goods more attractive to foreign buyers; meanwhile, by making imports more expensive, it would help encourage savings and investment in domestic production. It would also enable the country to pay back its government debt with currency of lower value, effectively wiping out part of that debt. Maintaining low interest rates helps reduce the dollar’s value, and the United States has kept interest rates low since the start of the crisis. But the US doesn’t want to announce to the world that it is seeking to trash the dollar, because this could reduce the dollar’s viability as the world’s reserve currency — a status that yields multiple advantages to America’s economy, and one that is increasingly being challenged.22

Investment money tends to “chase yield,” which has the effect of driving up the value of the currencies in countries where investment opportunities and higher yields are to be found — currently, the young, industrializing countries of Asia. China and the other industrializing nations are responding by doing everything they can to keep exchange rates for their currencies low relative to the dollar so as to maintain trade advantages and reduce the impacts of an influx of yield-seeking money.

China has led the way in the international competition to weaken national currencies, but Japan and the US are seeking to lower the value of the yen and the dollar, respectively. According to Bill Black, writing in Business Insider on December 13, 2010,

The EU, taking its lead from Germany, has allowed the Euro to appreciate against many currencies. Germany’s high-tech exports can survive a strong Euro, but Greece, Spain, and Portugal cannot export successfully under a strong Euro and their already severe economic crises can become much worse. The Irish will have serious problems, and their export problems would have been crippling if they were not a corporate income tax haven. Italy’s, particularly southern Italy’s, ability to export successfully is dubious.23

If the US dollar tumbles, that hurts China and other countries with fixed exchange rates; they feel pressured to drop their peg or revalue their currencies higher. Countries whose currencies are pegged to the dollar have had to resort to currency interventions and a massive buildup of foreign reserves to stop their currencies from appreciating. This is inflationary for those countries, and is one reason for the housing and equities boom in Asia.24 China’s way of pushing back against a lowering of the dollar’s value is its threat of ceasing to purchase US Treasury debt (which it has in fact partly done). If neither the United States nor the industrializing nations back down, the result could be a final refusal of the latter nations to continue funding deficits in the US.25

As the US dollar has weakened, it has done so only against those currencies that are free-floating. This has meant that countries like Japan and Germany have had to endure upward pressures on the value of their currencies. German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, interviewed in November 2010, had harsh words for his American counterparts, noting that “The US lived on borrowed money for too long,” and adding that:

The Fed’s decisions [to buy US Treasury debt] bring more uncertainty to the global economy. They make it more difficult to achieve a reasonable balance between industrialized and emerging economies, and they undermine the US’s credibility when it comes to fiscal policy. It’s inconsistent for the Americans to accuse the Chinese of manipulating exchange rates and then to artificially depress the dollar exchange rate by printing money.26

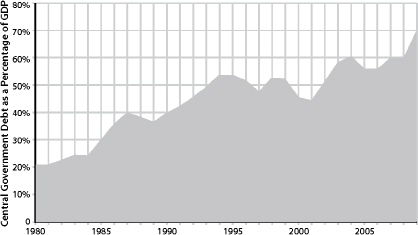

FIGURE 42. OECD Government Debt as a Percentage of GDP, 1980–2009. By 2009, the governments of the 34 OECD member countries held debts equal to 70 percent of their combined GDP. Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Meanwhile, also in November 2010, China and Russia ceased using the dollar in bilateral trade, with Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin declaring that his country might eventually adopt the euro. Even though Russia is not one of China’s top trading partners and is unlikely to be welcomed into the eurozone anytime soon, its leaders’ hostility to the dollar helps exacerbate discontent elsewhere. If China excludes dollar trades with other primary non-US trade partners there may be a reason for Washington to worry. For now, Beijing appears merely to be letting off steam with no serious intent of isolating the United States, or of causing its nearly $3 trillion in US foreign exchange reserves to lose a significant portion of their value.

Thus for the time being, pundits who warn of wider and worse currency wars leading to trade or military conflicts may be exaggerating the threat.27 Currency and trade wars are not in anyone’s interest. A trade war between the US and China, for example, would reduce the GDP of both countries — and China would have more to lose than the United States. As long as cool heads prevail, currency conflicts are not likely to get out of hand. Of course, there is always the possibility that cooler heads may not prevail — especially in the politically volatile US, where members of Congress posture by threatening to refuse to raise the debt ceiling.

Over the longer term, the ecosystem of world currencies faces increasing dangers if growth fails to return in the US, and if the Chinese economic juggernaut falters.

Debt-based currencies that are traded without any clear international exchange standard create an inherently unstable situation. The so-called “goldbugs,” economists who advocate a universal return to the gold standard, have plenty of grounds for criticizing free-floating currencies, but their alternative is simply not a realistic option: there isn’t enough gold in the world to support anything like current levels of trade and investment, and much of the gold that exists is held in enormous reserves where it can do little good as a medium of exchange. The transition from the present system back to a gold standard would be intolerably chaotic, if it is even theoretically possible. Other kinds of fundamental national and global currency reforms (such as we will touch upon in the next chapter) may have better practical prospects over the long run, but are currently outside the realm of serious discussion among policy makers.

Without a return to economic growth, there is no sufficient remedy for the rapidly worsening stresses between and among the world’s currencies. The lid can probably be kept on this boiling kettle in the short term, but over the course of the next decade it becomes more and more likely that something will give way.

Post-Growth Geopolitics

As nations compete for currency advantages, they are also eyeing the world’s diminishing resources — fossil fuels, minerals, agricultural land, and water. Resource wars have been fought since the dawn of history, but today the competition is entering a new phase.

Nations need increasing amounts of energy and materials to produce economic growth, but — as we have seen — the costs of supplying new increments of energy and materials are increasing. In many cases all that remains are lower-quality resources that have high extraction costs. In some instances, securing access to these resources requires military expenditures as well. Meanwhile the struggle for the control of resources is re-aligning political power balances throughout the world.

The US, as the world’s superpower, has the most to lose from a reshuffling of alliances and resource flows. The nation’s leaders continue to play the game of geopolitics by 20th-century rules: They are still obsessed with the Carter Doctrine and focused on petroleum as the world’s foremost resource prize (a situation largely necessitated by the country’s continuing overwhelming dependence on oil imports, due in turn to a series of short-sighted political decisions stretching back at least to the 1970s). The ongoing war in Afghanistan exemplifies US inertia: Most experts agree that there is little to be gained from the conflict, but withdrawal of forces is politically unfeasible.

The United States maintains a globe-spanning network of over 800 military bases that formerly represented tokens of security to regimes throughout the world — but that now increasingly only provoke resentment among the locals. This enormous military machine requires a vast supply system originating with American weapons manufacturers that in turn depend on a prodigious and ever-expanding torrent of funds from the Treasury. Indeed, the nation’s budget deficit largely stems from its trillion-dollar-per-year, first-priority commitment to continue growing its military-industrial complex.

Yet despite the country’s gargantuan expenditures on high-tech weaponry, its armed forces appear to be stretched to their limits, fielding around 200,000 troops and even larger numbers of support personnel in Iraq and Afghanistan, where supply chains are both vulnerable and expensive to maintain.

In short, the United States remains an enormously powerful nation militarily, with thousands of nuclear weapons in addition to its unparalleled conventional forces, yet it suffers from declining strategic flexibility.

The European Union, traditionally allied with the US, is increasingly mapping its priorities independently — partly because of increased energy dependence on Russia, and partly because of economic rivalries and currency conflicts with America. Germany’s economy is one of the few to have emerged from the 2008 crisis relatively unscathed, but the country is faced with the problem of having to bail out more and more of its neighbors. The ongoing European serial sovereign debt crisis could eventually undermine the German economy and throw into doubt the long-term soundness of the euro and the EU itself.28

The UK is a mere shadow of its former imperial self, with unsustainable levels of debt, declining military budgets, and falling oil production. Its foreign policy is still largely dictated in Washington, though many Britons are increasingly unhappy with this state of affairs.

China is the rising power of the 21st century, according to many geopolitical pundits, with a surging military and lots of cash with which to buy access to resources (oil, coal, minerals, and farmland) around the planet. Yet while it is building an imperial-class navy that could eventually threaten America’s, Beijing suffers (as we have already seen) from domestic political and economic weaknesses that could make its turn at the center of the world stage a brief one.

Japan, with the world’s third-largest national economy, is wary of China and increasingly uncertain of its protector, the US. The country is tentatively rebuilding its military so as to be able to defend its interests independently. Disputes with China over oil and gas deposits in the East China Sea are likely to worsen, as Japan has almost no domestic fossil fuel resources and needs secure access to supplies.

Russia is a resource powerhouse but is also politically corrupt and remains economically crippled. With a residual military force at the ready, it vies with China and the US for control of Caspian and Central Asian energy and mineral wealth through alliances with former Soviet states. It tends to strike tentative deals with China to counter American interests, but ultimately Beijing may be as much of a rival as Washington. Moscow uses its gas exports as a bargaining chip for influence in Europe. Meanwhile, little of the income from the country’s resource riches benefits the populace. The Russian people’s advantage in all this may be that they have recently been through one political-economic collapse and will therefore be relatively well-prepared to navigate another.

Even as countries like Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Nicaragua reject American foreign policy, the US continues to exert enormous influence on resource-rich Latin America via North American-based corporations, which in some cases wield overwhelming influence over entire national economies. However, China is now actively contracting for access to energy and mineral resources throughout this region, which is resulting in a gradual shift in economic spheres of interest.

Africa is a site of fast-growing US investment in oil and other mineral extraction projects (as evidenced by the establishment in 2009 of Afri-com, a military strategic command center on par with Centcom, Eucom, Northcom, Pacom, and Southcom), but is also a target of Chinese and European resource acquisition efforts. Proxy conflicts there between and among these powers may intensify in the years ahead — in most instances, to the sad detriment of African peoples.29 The Middle East maintains vast oil wealth (though reserves have been substantially overestimated due to rivalries inside OPEC), but is characterized by extreme economic inequality, high population growth rates, political instability, and the need for importation of non-energy resources (including food and water). The revolutions and protests in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, and Yemen in early 2011 were interpreted by many observers as indicating the inability of the common people in Middle Eastern regimes to tolerate sharply rising food, water, and energy prices in the context of autocratic political regimes.30 As economic conditions worsen, many more nations — including ones outside the Middle East — could become destabilized; the ultimate consequences are unknowable at this point, but could well be enormous.

Like China, Saudi Arabia is buying farmland in Australia, New Zealand, and the US. Nations like Iraq and Iran need advanced technology with which to maintain an oil industry that is moving from easy plays to oilfields that are smaller, harder to access, and more expensive to produce, and both Chinese and US companies stand ready to supply it.

The deep oceans and the Arctic will be areas of growing resource interest, as long as the world’s wealthier nations are still capable of mounting increasingly expensive efforts to compete for and extract strategic materials in these extreme environments.31 However, both military maneuvering and engineering-mining efforts will see diminishing returns as costs rise and payoffs diminish.

Unfortunately, rising costs and flagging returns from resource conflicts will not guarantee world peace. History suggests that as nations become more desperate to maintain their relative positions of strength and advantage, they may lash out in ways that serve no rational purpose.

Again, no crisis is imminent as long as cool heads prevail. But the world system is losing stability. Current economic and geopolitical conditions would appear to support a forecast not for increasing economic growth, democracy, and peace, but for more political volatility, and for greater government military mobilization justified under the banner of security.

Population Stress: Old vs. Young on a Full Planet

Throughout the past two centuries economic growth has translated to an increased capability to support more humans with Earth’s available resources. More energy, more raw materials, more jobs, more trade, better sanitation, and key medical advances have all contributed to higher infant survival rates and longer life expectancy in general. Human population growth can be seen as an indication of our success as a species.32

But now, as economic growth ends, higher population levels pose an enormous vulnerability. Declining energy, declining minerals and fresh water, and reduced global trade will challenge our ability to maintain existing food and public health systems, perhaps even in currently wealthy countries.

August Comte, the 19th-century French sociologist, famously declared that, “demography is destiny.” During the coming post-growth decades, the nations of the world will face somewhat differing challenges depending on their size of population, rates of population growth, median age, and degree of urbanization.

Countries with large, youthful, and growing urban populations will be hardest hit. Young people will face lack of economic opportunity as trade contracts. Also, countries with young populations will see continuing population growth even if efforts are undertaken now to rein in fertility, simply because the bulk of the population will be in the child-bearing age range for the next two or three decades.

Countries with stable or declining populations (this includes most western European nations) will see aging populations, and thus a declining proportion of the population will consist of youthful workers (as we saw in the case of China). Some economists see this as a serious problem, and as a result Germany is offering cash financial incentives for couples to reproduce. However, this merely puts off inevitable process of adjustment to the end of population growth.

The end of economic growth will pose demographic challenges to all societies. But having more people will result in a bigger challenge than having fewer.

In a low-income society, when people have many children they tend to spend whatever money they have on keeping those children fed, so there is little left over to invest in future economic productivity (including education for children). This is a situation that tends to lead to continuing poverty. If there is no surplus income, there is nothing for the government to tax, so governments don’t expand infrastructure: they don’t build roads to rural areas so farmers can get their product to market — or water treatment facilities, or electricity grids, or schools. If farmers can’t get their products to market, they may eventually give up and move to the cities where they strain whatever support infrastructure does exist. One of the best hopes for a society in this kind of bind is to reduce fertility.

Since World War II, eight countries (Tunisia, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Barbados, Hong Kong, and Bahamas) have achieved the shift from being listed as “developing” to “developed” by first bringing fertility down through strong family planning programs. Once fewer children were being born, families found that they had money left over after paying for basic necessities, and this led to capital formation through personal savings. Demographers call this the “demographic dividend.”

The continent of Africa will probably encounter the worst demographic challenges of any region in the decades ahead. Its population is expected to double its numbers by 2050, according to the UN. By then, Africa’s urban population may have tripled, with 1.3 billion living in cities. These trends of rapid population growth and rapid urbanization cannot be sustained in a world of declining energy, scarce water, and changing climate, and will soon become enormous liabilities as today’s quickly growing slums turn into centers of even greater human misery.

South Asia will also encounter enormous problems. Especially vulnerable is Pakistan, whose rapid population growth is already undermining access to education and medical facilities while posing serious health problems for women.33

The US has the fastest growing population of any industrialized country — mostly due to immigration (though immigration rates have declined in the last couple of years, probably due to the economic crisis). Already a hot-button issue, immigration could become even more of one as the economy contracts. But further waves of immigrants are possible if Mexico’s economy fails due to declining revenues from oil production.

Further declines in the US economy will shift public opinion toward wanting to restrict immigration and population growth. Every survey since the 1940s has shown that a majority of Americans favors reducing immigration, yet during that time legal immigration has quadrupled (it doubled during Bush I and again during Bush II). Much of the support for liberalizing immigration policy has come from the Democratic party (in its calculus, more immigrants mean more Democrats), as well as from the construction industry (more immigrants equal more housing starts), the food industry (which depends on low-paid seasonal farm workers), and the US Chamber of Commerce (immigrants reduce labor costs).

Sadly, the debate has failed to take account of one key question: What is the population level the US can sustain? By most accounts, the country is already overdrawing resources, so that future generations will have restricted access to fresh water, fertile soil, and useful minerals. Adding more people through immigration simply steals further from our grandchildren. Gains in the efficiency with which resources are used may help temporarily, but population growth erases those gains over the long run.

For all nations, immigration laws need to be based on reasonable targets based in turn on estimates of human carrying capacity. Those laws must deal humanely with extreme circumstances, including provisions for refugees — such as climate refugees, whose numbers will likely multiply dramatically in the years ahead.

Meanwhile, declining economic growth will probably lead to increased demographic competition between the old (who will be seen by the young to have used up the world’s resources) and the young (who will be seen by the old as a threat to savings and economic stability).

In the US, this competition may already be taking political form through the Tea Party movement, whose main agenda is to end government borrowing, bailouts, and stimulus packages, and to cap the national debt. These priorities are attractive to older, wealthier citizens who are concerned about protecting their savings from inflation — which would tend to benefit younger people saddled with debt.34 Meanwhile, younger citizens are unhappy looking toward a future in which college and home ownership are no longer affordable and few jobs are available.

The population problem is solvable by making family planning and contraception freely available, changing cultural norms (as is being done by Population Media Center), and advancing women’s rights.35 But consider a best-case scenario: In a dozen years, given proper funding, virtually all countries could achieve a replacement level of fertility. Still, even after that monumental accomplishment, it would be another 70 years before the world as a whole would achieve zero population growth or begin a controlled decline.

The population issue has been highly politicized, and those who argue for controls on population growth are often demonized as elitist, racist, or misogynist. This is tragic, because the ongoing debate has caused humanity to put off dealing with the problem for far too long. And it is the poor, and especially poor women and children, who will pay the price for this delay.

BOX 5.2 Implications for Women

During the past two centuries, industrialization and urbanization resulted in women’s entry into the work force, and this in turn catalyzed the movement for women’s rights. The end of cheap energy could see a return of women to work centered primarily in the home, and a consequent reduction in women’s rights and opportunities, unless attention and effort are devoted by both men and women to averting that outcome.

In her 2004 essay, “Peak Oil Is a Women’s Issue,” Sharon Astyk wrote:

“Whatever happens in the post peak future will hit women differently, and in many ways harder, than it will hit men. For example, women are more likely to be poor than men are. In an economic crisis, women are more likely than men to be impoverished, and more seriously. Elderly women are the poorest and most vulnerable people in the US, and their lives are not likely to be improved by peak oil. Women are more likely to be single parents, a job that will come with a whole host of new difficulties post peak. They are more likely than men to work minimum wage jobs, to be exploited at work.... Poor women are more likely to be victims of violence, to have unplanned children, to be trapped in poverty from which they can’t arise. In a period of economic crisis, where everyone is desperate for work, women will be even more vulnerable than usual, and we are already more vulnerable than men.

“Creating a sustainable future requires that women who don’t want to have children, or not yet, or not many, be able to cease doing so. And yet poverty dramatically decreases access to medical care and birth control even in our first-world society. The poorer and less well-educated you are (and those two things are reciprocally related) the more likely you are to become pregnant without intending it, both because of reduced access to reliable birth control and insufficient education in how to use it. The younger, poorer and less well-educated a woman is, the younger she is likely to have children, the more children she is likely to have, the more health consequences she and her children are likely to have (prematurity, high blood pressure, etc. . .), and the less likely she is to ever escape poverty — or for her children to escape it. In a major economic depression, the ranks of poor women are likely to grow enormously, and we are likely to see not fewer children, but more and more unwanted children unless we plan very carefully to ensure that we prioritize medical access for everyone as one of the things we do with our limited resources.”36

Astyk also points out that “Women also still do a disproportionate amount of child-rearing in just about every society, especially among very young children. They are the ones who instill values and ethics in their children to a large degree.”

The population issue is discussed from a women’s perspective in the new documentary film “Mother: Caring Our Way Out of the Population Dilemma.”37

The End of “Development”?

For decades agencies that either actually or ostensibly aimed to aid impoverished nations have employed the terms “developed,” “developing,” and “underdeveloped” to refer to countries at various stages of industrialization. In ordinary usage, the word develop often means “to progress from an embryonic to an adult form”; thus its application to processes of economic and social change has conveyed an implicit assumption of inevitability. By calling rich industrialized countries “developed” and poor non-industrial countries “underdeveloped,” policy makers were in effect saying that industrialization is equivalent to the healthy biological process of maturation, and should be the goal of all human societies. Through a trade-led process of economic expansion, non-industrial countries with subsistence economies and large indigenous populations must aim to become urbanized, consumer-driven, cosmopolitan manufacturing centers (according to this view): it is their right and destiny to do so.

This set of assumptions was always questionable. Indeed, it has been attacked with some vigor by Vandana Shiva, Helena Norberg-Hodge, Martin Kohr, Jerry Mander, Doug Tompkins, Gustavo Esteva, Edward Goldsmith, Ivan Illich, Manfred Max-Neef, David Graeber, and other prominent development critics (sometimes also known as post-development–theorists).38

The critics of development claimed that the project of using loans and aid packages to fund huge infrastructure projects in poor nations, or to build factories there for multinational corporations, was at its core merely a continuation of colonialism by other means. Since two-thirds of the world’s nations were defined as “underdeveloped,” this meant that people in most countries needed to look outside of their own cultures for economic, agricultural, and educational models. Poor Third World nations were encouraged to take on enormous amounts of debt, and to flush young people out of the countryside and into cities. All of this came at both a human and an environmental cost.

Development, according to the critics, was actually a euphemism for post-war American hegemony; and indeed it was the US (along with its European allies) that provided the loans, trade rules, educational templates, and media images that would reshape societies across the global south.

BOX 5.3 Development and Freedom

Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen argues that a country’s development should be measured by the freedom of its citizens.42 Sen points to political freedom, civil rights, economic freedom, social opportunities (access to healthcare, education, and other social services), transparency guarantees (dealings with others and the government that are characterized by a mutual understanding of what is expected and what is offered), and protective security (unemployment benefits, famine and emergency relief, and general social safety nets) as comprising an interdependent bundle of freedoms that are instrumental in enabling people to live better lives.

Sen refers to these freedoms as “capabilities,” arguing that they contribute to human functioning.43 He sees life as a set of “doings and beings” — i.e., being healthy, being employed, being safe, and so on. Capabilities are a person’s ability to do or be what they want given the resources they have. Civil rights, government transparency, education, and famine relief all make people better able to do and be what they want with what they have. And, for Sen, it is the ability and freedom to achieve what one wants that is the hallmark of development. Within the capabilities approach, development can be understood then as a process by which capabilities and freedom are expanded — not one where large increases are achieved in national GDP.

In this view, developed countries are not those with the highest per capita incomes, but those where people are best able to do and to be what they want.

One way to understand capabilities, development, and freedom is to think of them in the context of food security. It is widely understood that today people typically go hungry not from lack of food, but from their inability to access it. Poverty, social exclusion, and corrupt governance can all result in people being denied access to food. For example, a person may have the money to buy food and still go hungry due to unequal social status that results in exclusion from food networks. The way to remedy this is not by money alone, but by expanding capabilities and freedom. What the individual needs is civil rights and equal protection under the law. And the best way to achieve this, according to Sen, is through democracy. Sen argues that there has never been a famine under a democratic government. This is because in a democratic system people are better able to petition the government to act in emergency situations; also, democratic accountability provides incentives for leaders to act.

Sen’s capabilities approach has been incorporated into some welfare and poverty measurements being used today. The best example is the UN Human Development Index (HDI). This measure looks at education and life expectancy along with income to measure and understand a country’s development. It is interesting to note that the HDI does not correspond directly with a ranking of countries by GDP, or even GDP per capita — a measure that tends to mask inequality. For example, Norway ranks first on the HDI and 25th by national GDP. Conversely, China ranks second by national GDP and 89th on the HDI.

Another important consequence of the capabilities approach is that it allows for some real welfare improvements to be made that do not rely on increased resource use. For example, rooting out political corruption and ineptitude does not require much energy or resource throughput. However, other “capabilities,” including education, health, and nutrition may be more problematic in this regard. In their paper “Energetic Limits to Economic Growth,” Davidson, Brown, et al. argue that it has not been possible to increase socially desirable goods and services like nutrition, education, healthcare, technology, and innovation without increasing the consumption of energy and other natural resources.44

Two books galvanized anti-globalization activism and epitomized the arguments of development critics: Ancient Futures (1991) by Helena Norberg-Hodge, and Confessions of an Economic Hit Man (2005) by John Perkins.39

As a graduate student in linguistics in the 1970s, Norberg-Hodge had chosen to do field work in Ladakh, a remote Buddhist region in northern India. She found there a traditional village-based society virtually untouched by the modern Western world. The people had their problems, as people everywhere do, but the culture had evolved to suit its ecological constraints and opportunities; most people seemed generally happy, helpful, and friendly. Norberg-Hodge has continued her work in Ladakh up to the present, documenting how development has uprooted families, upended cultural norms, turned self-sufficiency into dependency, and created more misery than satisfaction.

John Perkins, a former chief economist at a Boston-based strategic consulting firm, claims he was groomed in the 1970s as an “economic hit man,” in which capacity he helped needlessly to plunge poor nations like Indonesia and Panama into debt. Perkins tells how he used purposefully over-optimistic economic projections to persuade foreign governments to accept billions of dollars in loans from the World Bank and other institutions in order to build dams, airports, electric grids, and other infrastructure that he knew they couldn’t afford and didn’t need. Construction and engineering contracts were routed to US companies, with bribes to top foreign officials smoothing the way. However, the resulting debts ultimately had to be shouldered by the taxpayers in the poor countries. When payments couldn’t be made, the World Bank or International Monetary Fund would jet in a team of economists to dictate the country’s budget and security agreements. Perkins contends that this all amounted to a clever way for the US to expand its global influence at the expense of citizens in poor, often largely indigenous nations.

The defenders of development have always maintained that such claims are either fabricated or overblown, and that the real purpose of loans and aid packages has been to raise the standard of living of people in the world’s poorest countries. Statistics lend support to this view. The recent 2010 UN Human Development Report concludes that people in poor nations are generally healthier, wealthier, and better educated than they were 40 years ago.40 Surveying human progress in 135 countries — 92 percent of the world’s population — the report shows that average life expectancy rose from 59 to 70 years, primary school enrolment grew from 55 to 70 percent, and per capita income doubled to more than $10,000. The report’s authors do devote a section to discussion of the “weak association between [GDP] growth and quality of life indicators such as health, education, political freedom, conflict and inequality,” and also note that, “Within countries rising income inequality is the norm.”

BOX 5.4 Development or Overdevelopment?

Development critics place significant emphasis on these latter points. It is relatively easy to measure GDP; it is more difficult to quantitatively assess the integrity of families and communities. Also, much of the measured “progress” of the past few decades has occurred in a few rapidly industrializing nations, while many very poor countries have actually lost ground in terms of most citizens’ access to food, water, and shelter. Averages and totals can obscure important and worrisome details.

Environmental preservationist and publisher Doug Tompkins, among others, uses the term “overdeveloped” to refer to what are conventionally called “developed” nations, and “nations on the road to overdevelop-ment” for those usually classified as “developing.” In this view, the goal of “development” as typically pursued is a condition that is clearly unsustainable, hence the term used to refer to it should reflect that fact.45 The term also is logically required as a counterpart to the more commonly employed concept of “underdevelopment.” Questioning how and why nations develop unevenly can lead to greater insight into the process whereby certain nations commandeer resources and labor to become “overdeveloped.”

The discussion about development’s efficacy was important during the heyday of economic expansion. However, now that growth is ending, the goal of conventional economic development — whether or not it ever made sense from humanitarian and environmental points of view — may have become largely unachievable.41

Without cheap transport fuel, the advantages of globalization begin to disappear, as we saw in Chapter 4. Scarce and expensive petroleum also undermines the project of industrializing agriculture and makes highway construction nonsensical. And the global credit crisis spells an end to big loans for unneeded infrastructure projects.

The priorities of poor nations have just changed. From here on, competing in the global economy will recede in importance; the primary challenge will be to adapt to post-growth world economic conditions and ever-worsening environmental challenges.

The UN Human Development Report does not address the resilience of societies in the face of declining global energy resources, the rising scale environmental disasters, or the end of economic growth (only the potential impacts of climate change are mentioned, though not taken fully into account). But in the decades ahead resilience will count for far more than economic competitiveness.

Urbanization, the industrialization of food systems, and the building of highways may have contributed to GDP over the short term, but they have created societal vulnerability over the longer term. In a world of Peak Oil, scarce fresh water, unstable currencies, changing climate, and declining trade, true “development” may require implementation of policies at odds with — sometimes the very reverse of — those of recent decades.

The phrase “sustainable development” entered the development lexicon in the late 1980s with the publication of the Report of the Brundtland Commission (the World Commission on Environment and Development); it was defined as development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” While this ideal has often been watered down in the process of implementation, if taken seriously it could help poor nations identify sound strategies for dealing with the end of growth.

All the world’s nations need to continue solving basic human problems (i.e., providing food, education, healthcare, and security) in the face of global environmental and economic change, without drawing down Earth’s nonrenewable resources or saddling future generations with onerous debt. And they have to do this in a way that protects fragile ecosystems — including forests, river systems, soils, and ocean fisheries — while, if possible, restoring them.

Nations whose subsistence farmers still form a significant proportion of the over-all population, though in recent decades termed “underdeveloped,” may in fact have some advantages in the post-growth world. Rather than continuing with ruinous attempts to install fuel-guzzling food and transport systems, these countries should be adopting the “appropriate” or “intermediate” technologies that have been advocated for several decades by E. F. Schumacher and others. Appropriate technology (or AT) is typically labor- and knowledge-intensive rather than capital-, resource, and energy-intensive. Examples include the use of local natural materials for building, the small-scale generation of local power from methane digesters, and the purification of water in households with porous ceramic filters.

People in currently wealthy nations may well find themselves adopting similar technological strategies in the decades ahead. In the process, there may be a substantial reversal of the trend, seen since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, toward greater wealth inequality among nations.

BOX 5.5 Human Scale Development

According to the school of “Human Scale Development” developed by Manfred Max-Neef, Antonio Elizalde, and Martin Hopenhayn, fundamental human needs are ontological (stemming from the condition of being human); they are also few, finite, and classifiable — as distinguished from the conventional notion of economic “wants” that are infinite and insatiable.46 They are also constant through all human cultures and throughout history; what changes is the set of strategies by which these needs are satisfied. Human needs are a system — that is, they are interrelated and interactive. The school of Human Scale Development is described as, “focused and based on the satisfaction of fundamental human needs, on the generation of growing levels of self-reliance, and on the construction of organic articulations of people with nature and technology, of global processes with local activity, of the personal with the social, of planning with autonomy, and of civil society with the state.”47 Max-Neef classifies the fundamental human needs as:

• subsistence,

• protection,

• affection,

• understanding,

• participation,

• leisure,

• creation,

• identity, and

• freedom.

The Post-Growth Struggle Between Rich and Poor

If current levels of wealth inequality among the world’s nations cannot be maintained in a non-growing, energy-starved economy, that doesn’t necessarily mean that we are headed toward a future of perfect equity. Rather, the end of growth is likely to lead, in many instances, to a sharply heightened struggle between rich and poor for control of the world’s vanishing wealth.

As GDP per capita has increased during the past two centuries, so has inequality in the distribution of wealth, both among nations and often within nations as well. These trends will not be abandoned without a fight.

The most widely used metric of economic inequality is the Gini coefficient, developed by Italian statistician Corrado Gini in 1912. A value of 0 reflects total equality, while a value of 1 shows maximal inequality. In the world currently, Gini coefficients for income within nations range from approximately 0.23 (Sweden, with the lowest level of economic inequality) to 0.70 (Namibia, with the highest). The US weighs in at 0.45 — between Cote d’Ivoire at 0.446 and Uruguay at 0.452 (some agencies arbitrarily shift the decimal point two places to the right for all scores, giving the US a score of 45 instead of 0.45).