Few economists saw our current crisis coming, but this predictive failure was the least of the field’s problems. More important was the profession’s blindness to the very possibility of catastrophic failures in a market economy.

— Paul Krugman (economist)

The conventional wisdom on the state of the economy — that the financial crisis that started in 2008 was caused by bad real estate loans and that eventually, when the kinks are worked out, the nation will be back to business as usual — is tragically wrong. Our real situation is far more unsettling, our problems have much deeper roots, and an adequate response will require far more from us than just waiting for the business cycle to come back around to the “growth” setting. In reality, our economic system is set for a dramatic, and for all practical purposes permanent, reset to a much lower level of function. Civilization is about to be downsized.

Why have the vast majority of pundits missed this story? Partly because they rely on economic experts with a tunnel vision that ignores the physical limits of planet Earth — the context in which economies operate.

In this chapter we will see in brief outline not only how economies and economic theories have evolved from ancient times to the present, but how and why some modern industrial economies — particularly that of the US — have come to resemble casinos, where a significant proportion of economic activity takes the form of speculative bets on the rise or fall in value of an array of real or illusory assets. And we’ll see why all of these developments have led to the fundamental impasse at which we are stuck today.

In order to maximize our perspective, we’re going to start our story at the very beginning.

Economic History in Ten Minutes

Throughout over 95 percent of our species’ history, we humans lived by hunting and gathering in what anthropologists call gift economies.1 People had no money, and there was neither barter nor trade among members of any given group. Trade did exist, but it occurred only between members of different communities.

It’s not hard to see why sharing was the norm within each band of hunter-gatherers, and why trade was restricted to relations with strangers. Groups were small, usually comprising between 15 and 50 persons, and everyone knew and depended on everyone else within the group. Trust was essential to individual survival, and competition would have undermined trust. Trade is an inherently competitive activity: each trader tries to get the best deal possible, even at the expense of other traders. For hunter-gatherers, cooperation — not competition — was the route to success, and so innate competitive drives (especially among males) were moderated through ritual and custom, while a thoroughly entangled condition of mutual indebtedness helped maintain a generally cooperative attitude on everyone’s part.

Today we still enjoy vestiges of the gift economy, notably in the family. We don’t keep close tabs on how much we are spending on our three-year-old child in an effort to make sure that accounts are settled at some later date; instead, we provide food, shelter, education and more as free gifts, out of love. Yes, parents enjoy psychological rewards, but (at least in the case of mentally healthy parents) there is no conscious process of bargaining, in which we tell the child, “I will give you food and shelter if you repay me with goods and services of equivalent or greater value.”

For humans in simple societies, the community was essentially like a family. Freeloading was occasionally a problem, and when it became a drag on the rest of the group it was punished by subtle or not-so-subtle social signals — ultimately, ostracism. But otherwise no one kept score of who owed whom what; to do so would have been considered very bad manners.

We know this from the accounts of 20th-century anthropologists who visited surviving hunter-gatherer societies. Often they reported on the amazing generosity of people who seemed eager to share everything they owned despite having almost no material possessions and being officially listed by aid agencies as among the poorest people on the planet.2 In some instances anthropologists felt embarrassed by this generosity, and, after being gifted some prized food or a painstakingly hand-made basket, immediately offered a factory-made knife or ornament in return. The anthropologist assumed that natives would be happy to receive the trinkets, but the recipients instead appeared insulted. What had happened? The natives’ initial gifts were a way of saying, “You are part of the family; welcome!” But the immediate offering of a gift in return smacked of trade — something only done with strangers. The anthropologist was understood as having said, “No, thanks. I do not wish to be considered part of your family; I want to remain a stranger to you.”

By the way, this brief foray into cultural anthropology shouldn’t be interpreted as an argument that the hunting-gathering existence represents some ideal of perfection. Partly because simpler societies lacked police and jails, they tended to feature very high levels of interpersonal violence. Accidents were common and average lifespan was short. The gift economy, with both its advantages and limits, was simply a strategy that worked in a certain context, honed by tens of millennia of trial and error.

Here is economic history compressed into one sentence: As societies have grown more complex, larger, more far-flung, and diverse, the tribe-based gift economy has shrunk in importance, while the trade economy has grown to dominate most aspects of people’s lives, and has expanded in scope to encompass the entire planet. Is this progress or a process of moral decline? Philosophers have debated the question for centuries. Approve or disapprove, it is what we have done.

With more and more of our daily human interactions based on exchange rather than gifting, we have developed polite ways of being around each other on a daily basis while maintaining an exchange-mediated social distance. This is particularly the case in large cities, where anonymity is fostered also by the practical formalities and psychological impacts that go along with the need to interact with large numbers of strangers, day in and day out. In the best instances, we still take care of one another — often through government programs and private charities. We still enjoy some of the benefits of the old gift economy in our families and churches. But increasingly, the market rules our lives. Our apparent destination in this relentless trajectory toward expansion of trade is a world in which everything is for sale, and all human activities are measured by and for their monetary value.

Humanity has benefited in many obvious ways from this economic evolution: the gift economy really only worked when we lived in small bands and had almost no possessions to speak of. So letting go of the gift economy was a trade-off for houses, cities, cars, iPhones, and all the rest. Still, saying goodbye to community-as-family was painful, and there have been various attempts throughout history to try to revisit it. Communism was one such attempt. However, trying to institutionalize a gift economy at the scale of the nation state introduces all kinds of problems, including those of how to reward initiative and punish laziness in ways that everyone finds acceptable, and how to deter corruption among those whose job it is to collect, count, and reapportion the wealth.

But back to our tour of economic history. Along the road from the gift economy to the trade economy there were several important landmarks. Of these, the invention of money was clearly the most important. Money is a tool used to facilitate trade. People invented it because they needed a medium of exchange to make trading easier, simpler, and more flexible. Once money came into use, the exchange process was freed to grow and to insert itself into aspects of life where it had never been permitted previously. Money simultaneously began to serve other functions as well — principally, as a measure and store of value.

Today we take money for granted. But until fairly recent times it was an oddity, something only merchants used on a daily basis. Some complex societies, including the Inca civilization, managed to do almost completely without it; even in the US, until the mid-20th century, many rural families used money only for occasional trips into town to buy nails, boots, glass, or other items they couldn’t grow or make for themselves on the farm.

In his marvelous book The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilization & Capitalism 15th–18th Century, historian Fernand Braudel wrote of the gradual insinuation of the money economy into the lives of medieval peasants: “What did it actually bring? Sharp variations in prices of essential foodstuffs; incomprehensible relationships in which man no longer recognized either himself, his customs or his ancient values. His work became a commodity, himself a ‘thing.’”3

While early forms of money consisted of anything from sheep to shells, coins made of gold and silver gradually emerged as the most practical, universally accepted means of exchange, measure of value, and store of value.

Money’s ease of storage enabled industrious individuals to accumulate substantial amounts of wealth. But this concentrated wealth also presented a target for thieves. Thievery was especially a problem for traders: while the portability of money enabled travel over long distances for the purchase of rare fabrics and spices, highwaymen often lurked along the way, ready to snatch a purse at knife-point. These problems led to the invention of banking — a practice in which metal-smiths who routinely dealt with large amounts of gold and silver (and who were accustomed to keeping it in secure, well-guarded vaults) agreed to store other people’s coins, offering storage receipts in return. Storage receipts could then be traded as money, thus making trade easier and safer.4

Eventually, by the Middle Ages, goldsmith-bankers realized that they could issue these tradable receipts for more gold than they had in their vaults, without anyone being the wiser. They did this by making loans of the receipts, for which they charged a fee amounting to a percentage of the loan.

Initially the church regarded the practice of profiting from loans as a sin — known as usury — but the bankers found a loophole in religious doctrine: it was permitted to charge for reimbursement of expenses incurred in making the loan. This was termed interest. Gradually bankers widened the definition of “interest” to include what had formerly been called “usury.”

The practice of loaning out receipts for gold that didn’t really exist worked fine, unless many receipt-holders wanted to redeem paper notes for gold or silver all at once. Fortunately for the bankers, this happened so rarely that eventually the writing of receipts for more money than was on deposit became a perfectly respectable practice known as fractional reserve banking.

It turned out that having increasing amounts of money in circulation was a benefit to traders and industrialists during the historical period when all of this was happening — a time when unprecedented amounts of new wealth were being created, first through colonialism and slavery, but then by harnessing the enormous energies of fossil fuels.

The last impediment to money’s ability to act as a lubricant for transactions was its remaining tie to precious metals. As long as paper notes were redeemable for gold or silver, the amounts of these substances existing in vaults put at least a theoretical restraint on the process of money creation. Paper currencies not backed by metal had sprung up from time to time, starting as early as the 13th century ce in China; by the late 20th century, they were the near-universal norm.

Along with more abstract forms of currency, the past century has also seen the appearance and growth of ever more sophisticated investment instruments. Stocks, bonds, options, futures, long- and short-selling, credit default swaps, and more now enable investors to make (or lose) money on the movement of prices of real or imaginary properties and commodities, and to insure their bets — even their bets on other investors’ bets.

Probably the most infamous investment scheme of all time was created by Charles Ponzi, an Italian immigrant to the US who, in 1919, began promising investors he could double their money within 90 days. Ponzi told clients the profits would come from buying discounted postal reply coupons in other countries and redeeming them at face value in the United States — a technically legal practice that could yield up to a 400 percent profit on each coupon redeemed due to differences in currency values. What he didn’t tell them was that each coup0n had to be redeemed individually, so the red tape involved would entail prohibitive costs if large numbers of the coupons (which were only worth a few pennies) were bought and redeemed. In reality, Ponzi was merely paying early investors returns from the principal amounts contributed by later investors. It was a way of shifting wealth from the many to the few, with Ponzi skimming off a lavish income as the money passed through his hands. At the height of the scheme, Ponzi was raking in $250,000 a day, millions in today’s dollars. Thousands of people lost their savings, in some cases having mortgaged or sold their houses in order to invest.

A few critics (primarily advocates of gold-backed currency) have called fractional reserve banking a kind of Ponzi scheme, and there is some truth to the claim.5 As long as the real economy of goods and services within a nation is growing, an expanding money supply seems justifiable, arguably necessary. However, units of currency are essentially claims on labor and natural resources — and as those claims multiply (with the growth of the money supply), and as resources deplete, eventually the remaining resources will be insufficient to satisfy all of the existing monetary claims. Those claims will lose value, perhaps dramatically and suddenly. When this happens, paper and electronic currency systems based on money creation through fractional reserve banking will produce results somewhat similar to those of a collapsing Ponzi scheme: the vast majority of those involved will lose much or all of what they thought they had.

BOX 1.1 Why Was Usury Banned?

In his book Medici Money: Banking, Metaphysics, and Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence, Tim Parks writes:

“Usury changes things. With interest rates, money is no longer a simple and stable commodity that just happens to have been chosen as a medium of exchange. Projected through time, it multiplies, and this without any toil on the part of the usurer. Everything becomes more fluid. A man can borrow money, buy a loom, sell his wool at a high price, change his station in life. Another man can borrow money, buy the first man’s wool, ship it abroad, and sell it at an even higher price. He moves up the social scale. Or if he is unlucky, or foolish, he is ruined. Meanwhile, the usurer, the banker, grows richer and richer. We can’t even know how rich, because money can be moved and hidden, and gains on financial transactions are hard to trace. It’s pointless to count his sheep and cattle or to measure how much land he owns. Who will make him pay his tithe? Who will make him pay his taxes? Who will persuade him to pay some attention to his soul when life has become so interesting? Things are getting out of hand.”6

Economics for the Hurried

We have just surveyed the history of economies — the systems by which humans create and distribute wealth. Economics, in contrast, is a set of philosophies, ideas, equations, and assumptions that describe how all of this does, or should, work.7

This story begins much more recently. While the first economists were ancient Greek and Indian philosophers, among them Aristotle (382– 322 bce) — who discussed the “art” of wealth acquisition and questioned whether property should best be owned privately or by government acting on behalf of the people — little of real substance was added to the discussion during the next two thousand years.

It’s in the 18th century that economic thinking really gets going. “Classical” economic philosophers such as Adam Smith (1723–1790), Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834), and David Ricardo (1772–1823) introduced basic concepts such as supply and demand, division of labor, and the balance of international trade. As happens in so many disciplines, early practitioners were presented with plenty of uncharted territory and proceeded to formulate general maps of their subject that future experts would labor to refine in ever more trivial ways.

These pioneers set out to discover natural laws in the day-to-day workings of economies. They were striving, that is, to make of economics a science on a par with the emerging disciplines of physics and astronomy.

Like all thinkers, the classical economic theorists — to be properly understood — must be viewed in the context of their age. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Europe’s power structure was beginning to strain: as wealth flowed from colonies, merchants and traders were getting rich, but they increasingly felt hemmed in by the established privileges of the aristocracy and the church. While economic philosophers were mostly interested in questioning the aristocracy’s entrenched advantages, they admired the ability of physicists, biologists, and astronomers to demonstrate the fallacy of old church doctrines, and to establish new universal “laws” through inquiry and experiment.

Physical scientists set aside biblical and Aristotelian doctrines about how the world works and undertook active investigations of natural phenomena such as gravity and electromagnetism — fundamental forces of nature. Economic philosophers, for their part, could point to price as arbiter of supply and demand, acting everywhere to allocate resources far more effectively than any human manager or bureaucrat could ever possibly do. Surely this was a principle as universal and impersonal as the force of gravitation! Isaac Newton had shown there was more to the motions of the stars and planets than could be found in the book of Genesis; similarly, Adam Smith was revealing more potential in the principles and practice of trade than had ever been realized through the ancient, formal relations between princes and peasants, or among members of the medieval crafts guilds.

The classical theorists gradually adopted the math and some of the terminology of science. Unfortunately, however, they were unable to incorporate into economics the basic self-correcting methodology that is science’s defining characteristic. Economic theory required no falsifi-able hypotheses and demanded no repeatable controlled experiments (these would in most instances have been hard to organize in any case). Economists began to think of themselves as scientists, while in fact their discipline remained a branch of moral philosophy — as it largely does to this day.8

The notions of these 18th- and early 19th-century economic philosophers constituted classical economic liberalism — the term liberal in this case indicating a belief that managers of the economy should let markets act freely and openly, without outside intervention, to set prices and thereby allocate goods, services, and wealth. Hence the term laissez-faire (from the French “let do” or “let it be”).

In theory, the Market was a beneficent quasi-deity tirelessly working for everyone’s good by distributing the bounty of nature and the products of human labor as efficiently and fairly as possible. But in fact everybody wasn’t benefiting equally or (in many people’s minds) fairly from colonialism and industrialization. The Market worked especially to the advantage of those for whom making money was a primary interest in life (bankers, traders, industrialists, and investors), and who happened to be clever and lucky. It also worked nicely for those who were born rich and who managed not to squander their birthright. Others, who were more interested in growing crops, teaching children, or taking care of the elderly, or who were forced by circumstance to give up farming or cottage industries in favor of factory work, seemed to be getting less and less — certainly as a share of the entire economy, and often in absolute terms. Was this fair? Well, that was a moral and philosophical question. In defense of the Market, many economists said that it was fair: merchants and factory owners were making more because they were increasing the general level of economic activity; as a result, everyone else would also benefit...eventually. See? The Market can do no wrong. To some this sounded a bit like the circularly reasoned response of a medieval priest to doubts about the infallibility of scripture. Still, despite its blind spots, classical economics proved useful in making sense of the messy details of money and markets.

Importantly, these early philosophers had some inkling of natural limits and anticipated an eventual end to economic growth. The essential ingredients of the economy were understood to consist of land, labor, and capital. There was on Earth only so much land (which in these theorists’ minds stood for all natural resources), so of course at some point the expansion of the economy would cease. Both Malthus and Smith explicitly held this view. A somewhat later economic philosopher, John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), put the matter as follows: “It must always have been seen, more or less distinctly, by political economists, that the increase in wealth is not boundless: that at the end of what they term the progressive state lies the stationary state....”9

But, starting with Adam Smith, the idea that continuous “improvement” in the human condition was possible came to be generally accepted. At first, the meaning of “improvement” (or progress) was kept vague, perhaps purposefully. Gradually, however, “improvement” and “progress” came to mean “growth” in the current economic sense of the term — abstractly, an increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), but in practical terms, an increase in consumption.

A key to this transformation was the gradual deletion by economists of land from the theoretical primary ingredients of the economy (increasingly, only labor and capital really mattered, land having been demoted to a sub-category of capital). This was one of the refinements that turned classical economic theory into neoclassical economics; others included the theories of utility maximization and rational choice. While this shift began in the 19th century, it reached its fruition in the 20th through the work of economists who explored models of imperfect competition, and theories of market forms and industrial organization, while emphasizing tools such as the marginal revenue curve (this is when economics came to be known as “the dismal science” — partly because its terminology was, perhaps intentionally, increasingly mind-numbing).10

Meanwhile, however, the most influential economist of the 19th century, a philosopher named Karl Marx, had thrown a metaphorical bomb through the window of the house that Adam Smith had built. In his most important book, Das Kapital, Marx proposed a name for the economic system that had evolved since the Middle Ages: capitalism. It was a system founded on capital. Many people assume that capital is simply another word for money, but that entirely misses the essential point: capital is wealth — money, land, buildings, or machinery — that has been set aside for production of more wealth. If you use your entire weekly paycheck for rent, groceries, and other necessities, you may occasionally have money but no capital. But even if you are deeply in debt, if you own stocks or bonds, or a computer that you use for a home-based business, you have capital.

Capitalism, as Marx defined it, is a system in which productive wealth is privately owned. Communism (which Marx proposed as an alternative) is one in which productive wealth is owned by the community, or by the nation on behalf of the people.

In any case, Marx said, capital tends to grow. If capital is privately held, it must grow: as capitalists compete with one another, those who increase their capital fastest are inclined to absorb the capital of others who lag behind, so the system as a whole has a built-in expansionist imperative. Marx also wrote that capitalism is inherently unsustainable, in that when the workers become sufficiently impoverished by the capitalists, they will rise up and overthrow their bosses and establish a communist state (or, eventually, a stateless workers’ paradise).

The ruthless capitalism of the 19th century resulted in booms and busts, and a great increase in inequality of wealth — and therefore an increase in social unrest. With the depression of 1873 and the crash of 1907, and finally the Great Depression of the 1930s, it appeared to many social commentators of the time that capitalism was indeed failing, and that Marx-inspired uprisings were inevitable; the Bolshevik revolt in 1917 served as a stark confirmation of those hopes or fears (depending on one’s point of view).

20th-Century Economics

Beginning in the late 19th century, social liberalism emerged as a moderate response to both naked capitalism and Marxism. Pioneered by sociologist Lester F. Ward (1841–1913), psychologist William James (1842–1910), philosopher John Dewey (1859–1952), and physician-essayist Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809–1894), social liberalism argued that government has a legitimate economic role in addressing social issues such as unemployment, healthcare, and education. Social liberals decried the unbridled concentration of wealth within society and the conditions suffered by factory workers, while expressing sympathy for labor unions. Their general goal was to retain the dynamism of private capital while curbing its excesses.

Non-Marxian economists channeled social liberalism into economic reforms such as the progressive income tax and restraints on monopolies. The most influential of the early 20th-century economists of this school was John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), who advised that when the economy falls into a recession government should spend lavishly in order to restart growth. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs of the 1930s constituted a laboratory for Keynesian economics, and the enormous scale of government borrowing and spending during World War II was generally credited with ending the Depression and setting the US on a path of economic expansion.

The next few decades saw a three-way contest between Keynesian social liberals, the followers of Marx, and temporarily marginalized neoclassical or neoliberal economists who insisted that social reforms and government borrowing or meddling with interest rates merely impeded the ultimate efficiency of the free Market.

With the fall of the Soviet Union at the end of the 1980s, Marxism ceased to have much of a credible voice in economics. Its virtual disappearance from the discussion created space for the rapid rise of the neoliberals, who for some time had been drawing energy from widespread reactions against the repression and inefficiencies of state-run economies. Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan both relied heavily on advice from neoliberal thinkers like monetarist Milton Friedman (1912–2006) and followers of the Austrian School economist Friedrich von Hayek (1899–1992).

There is a saying now in Russia: Marx was wrong in everything he said about communism, but he was right in everything he wrote about capitalism. Since the 1980s, the nearly worldwide re-embrace of classical economic philosophy has predictably led to increasing inequalities of wealth within the US and other nations, and to more frequent and severe economic bubbles and crashes.

Which brings us to the global crisis that began in 2007–2008. By this time the two remaining mainstream economics camps — the Keynesians and the neoliberals — had come to assume that perpetual growth is the rational and achievable goal of national economies. The discussion was only about how to maintain it: through government intervention or a laissez-faire approach that assumes the Market always knows best.

But in 2008 economic growth ceased in many nations, and there has as yet been limited success in restarting it. Indeed, by some measures the US economy is slipping further behind, or at best treading water. This dire reality constitutes a conundrum for both economic camps. It is clearly a challenge to the neoliberals, whose deregulatory policies were largely responsible for creating the shadow banking system, the implosion of which is generally credited with stoking the current economic crisis. But it is a problem also for the Keynesians, whose stimulus packages have failed in their aim of increasing employment and general economic activity. What we have, then, is a crisis not just of the economy, but also of economic theory and philosophy.

The ideological clash between Keynesians and neoliberals (represented to a certain degree in the escalating all-out warfare between the US Democratic and Republican political parties) will no doubt continue and even intensify. But the ensuing heat of battle will yield little light if both philosophies conceal the same fundamental errors. One such error is the belief that economies can and should perpetually grow.

But that error rests on another that is deeper and subtler. The subsuming of land within the category of capital by nearly all post-classical economists had amounted to a declaration that Nature is merely a subset of the human economy — an endless pile of resources to be transformed into wealth. It also meant that natural resources could always be substituted with some other form of capital — money or technology.11 The reality, of course, is that the human economy exists within and entirely depends upon Nature, and many natural resources have no realistic substitutes. This fundamental logical and philosophical mistake, embedded at the very core of modern mainstream economic philosophies, set society directly on a course toward the current era of climate change and resource depletion, and its persistence makes conventional economic theories — of both Keynesian and neoliberal varieties — utterly incapable of dealing with the economic and environmental survival threats to civilization in the 21st century.

For help we can look to the ecological and biophysical economists — whose ideas we will discuss in Chapter 6, and who have been thoroughly marginalized by the high priests and gatekeepers of mainstream economics — and, to a certain extent, to the likewise marginalized Austrian and Post-Keynesian schools, whose standard bearers have been particularly good at forecasting and diagnosing the purely financial aspects of the current global crisis. But that help will not come in the form that many would wish: as advice that can return our economy to a “normal” state of “healthy” growth. One way or the other — whether through planning and methodical reform, or through collapse and failure — our economy is destined to shrink, not grow.

BOX 1.2 Absurdities of Conventional Economic Theory

• Mainstream economists’ way of calculating a nation’s economic health — the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) — counts only monetary transactions. If a country has happy families, the GDP won’t reflect that fact; but if the same country suffers a war or natural disaster monetary transactions will likely increase, leading to a bounce in the GDP. Calculating a nation’s overall health according to its GDP makes about as much sense as evaluating the quality of a piece of music solely by counting the number of notes it contains.

• A related absurdity is what economists call an “externality.” An externality occurs when production or consumption by one party directly affects the welfare of another party, where “directly” means that the effect is unpriced (it is external to the market). The damage to ecosystems that occurs from logging and mining is an externality if it isn’t figured into the price of lumber or coal. Positive externalities are possible (if some people farm organically, even people who don’t grow or eat organic food will benefit thanks to an overall reduction in the load of pesticides in the environment). Unfortunately, negative externalities are far more prevalent, since corporations use them as economic loopholes through which to pump every imaginable sort of pollution and abuse. Corporations keep the profit and leave society as a whole to clean up the mess.

• Mainstream economists habitually treat asset depletion as income, while ignoring the value of the assets themselves. If the owner of an old-growth forest cuts it and sells the timber, the market may record a drop in the land’s monetary value, but otherwise the ecological damage done is regarded as an externality. Irreplaceable biological assets, in this case, have been liquidated; thus the benefit of these assets to future generations is denied. From an ecosystem point of view, an economy that does not heavily tax the extraction of non-renewable resources is like a jobless person rapidly spending an inheritance.

• Mainstream economists like to treat people as if they were producers and consumers — and nothing more. The theoretical entity Homo eco-nomicus will act rationally to acquire as much wealth as possible and to consume as much stuff as possible. Generosity and self-limitation are (according to theory) irrational. Anthropological evidence of the existence of non-economic motives in humans is simply brushed aside. Unfortunately, people tend to act (to some degree, at least) the way they are expected and conditioned to act; thus Homo economicus becomes a self-confirming prediction.

Business Cycles, Interest Rates, and Central Banks

We have just reviewed a minimalist history of human economies and the economic theories that have been invented to explain and manage them. But there is a lot of detail to be filled in if we are to understand what’s happening in the world economy today. And much of that detail has to do with the spectacular growth of debt — in obvious and subtle forms — that has occurred during the past few decades. The modern debt phenomenon in turn must be seen in light of recurring business cycles that characterize economic activity in modern industrial societies, and the central banks that have been set up to manage them.

We’ve already noted that nations learned to support the fossil fuel-stoked growth of their real economies by increasing their money supply via fractional reserve banking. As money was gradually de-linked from physical substance (i.e., precious metals), the creation of money became tied to the making of loans by commercial banks. This meant that the supply of money was entirely elastic — as much could be created as was needed, and the amount in circulation could contract as well as expand. Growth of money was tied to growth of debt.

The system is dynamic and unstable, and this instability manifests in the business cycle, which in a simplified model looks something like this.12 In the expansionary phase of the cycle, businesses see the future as rosy, and therefore take out loans to build more productive capacity and hire new workers. Because many businesses are doing this at the same time, the pool of available workers shrinks; so, to attract and keep the best workers, businesses have to raise wages. With wages increasing, worker-consumers have more money in their pockets, which they then spend on products made by businesses. This increases demand, and businesses see the future as even rosier and take out more loans to build even more productive capacity and hire even more workers...and so the cycle continues. Amid all this euphoria, workers go into debt based on the expectation that their wages will continue to grow, making it easy to repay loans. Businesses go into debt to expand their productive capacity. Real estate prices go up because of rising demand (former renters decide they can now afford to buy), which means that houses are worth more as collateral for homeowner loans. All of this borrowing and spending increases both the money supply and the “velocity” of money — the rate at which it is spent and re-spent.

At some point, however, the overall mood of the country changes. Businesses have invested in as much productive capacity as they are likely to need for a while. They feel they have taken on as much debt as they can handle and don’t need to hire more employees. Upward pressure on wages ceases, which helps dampen the general sense of optimism about the economy. Workers likewise become shy about taking on more debt, and instead concentrate on paying off existing debts. Or, in the worst case, if they have lost their jobs, they may fail to make debt payments or even declare bankruptcy. With fewer loans being written, less new money is being created; meanwhile, as earlier loans are paid off or defaulted upon, money effectively disappears from the system. The nation’s money supply contracts in a self-reinforcing spiral.

But if people increase their savings during this downward segment of the cycle, they eventually will feel more secure and therefore more willing to begin spending again. Also, businesses will eventually have liquidated much of their surplus productive capacity and reduced their debt burden. This sets the stage for the next expansion phase.

Business cycles can be gentle or rough, and their timing is somewhat random and largely unpredictable.13 They are also controversial: Austrian School and Chicago School economists believe they are self-correcting as long as the government and central banks (which we’ll discuss below) don’t interfere; Keynesians believe they are only partially self-correcting and must be managed.

In the worst case, the upside of the cycle can constitute a bubble, and the downside a recession or even a depression. A recession is a widespread decline in GDP, employment, and trade lasting from six months to a year; a depression is a sustained, multi-year contraction in economic activity. In the narrow sense of the term, a bubble consists of trade in high volumes at prices that are considerably at odds with intrinsic values, but the word can also be used more broadly to refer to any instance of rapid expansion of currency or credit that’s not sustainable over the long run. Bubbles always end with a crash: a rapid, sharp decline in asset values.

Interest rates can play an important role in the business cycle. When rates are low, both businesses and individuals are more likely to want to take on more debt; when rates are high, new debt is more expensive to service. When money is flooding the system, the price of money (in terms of interest rates) naturally tends to fall, and when money is tight its price tends to rise — effects that magnify the existing trend.14

During the 19th century, as banks acted with little supervision in creating money to fuel business growth cycles and bubbles, a series of financial crises ensued. In response, bankers in many countries organized to pressure governments to authorize central banks to manage the national money supply. In the US, the Federal Reserve (“the Fed”) was authorized by Congress in 1913 to act as the nation’s central bank.

The essential role of central banks, such as the Fed, is to conduct the nation’s monetary policy, supervise and regulate banks, maintain the stability of the financial system, and provide financial services to both banks and the government. In doing this, central banks also often aim to moderate business cycles by controlling interest rates. The idea is simple enough: lowering interest rates makes borrowing easier, leading to an increasing money supply and the moderation of recessionary trends; high interest rates discourage borrowing and deflate dangerous bubbles.

The Federal Reserve charters member banks, which must obey rules if they are to maintain the privilege of creating money through generating loans. It effectively controls interest rates for the banking system as a whole by influencing the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, and the rate for overnight loans that member banks borrow directly from the Fed. In addition, the Fed can purchase government debt obligations, creating the money out of thin air (by fiat) with which to do so, thus directly expanding the nation’s money supply and thereby influencing the interest rates on bonds.

The Fed has often been a magnet for controversy. While it operates without fanfare and issues statements filled with terms opaque even to many trained economists, its secrecy and power have led many critics to call for reforms or for its replacement with other kinds of banking regulatory institutions. Critics point out that the Fed is not really democratic (the Fed chairman is appointed by the US President, but other board members are chosen by private banks, which also own shares in the institution, making it an odd government-corporate hybrid).

Other central banks serve similar functions within their domestic economies, but with some differences: The Bank of England, for example, was nationalized in 1946 and is now wholly owned by the government; the Bank of Russia was set up in 1990 and by law must channel half of its profits into the national budget (the Fed does this with all its profits, after deducting operating expenses). Nevertheless, many see the Fed and central banks elsewhere (the European Central Bank, the Bank of Canada, the People’s Bank of China, the Reserve Bank of India) as clubs of bankers that run national economies largely for their own benefit. Suspicions are most often voiced with regard to the Fed itself, which is arguably the most secretive and certainly the most powerful of the central banks. Consider the Fed’s theoretical ability to engineer either a euphoric financial bubble or a Wall Street crash immediately before an election, and its ability therefore to substantially impact that election. It is not hard to see why president James Garfield would write, “Whoever controls the volume of money in any country is absolute master of industry and commerce,” or why Thomas Jefferson would opine, “Banking establishments are more dangerous than standing armies.”

Still, the US government itself — apart from the Fed — maintains an enormous role in managing the economy. National governments set and collect taxes, which encourage or discourage various kinds of economic activity (taxes on cigarettes encourage smokers to quit; tax breaks for oil companies discourage alternative energy producers). General tax cuts can spur more activity throughout the economy, while generally higher taxes may dampen borrowing and spending. Governments also regulate the financial system by setting their own rules for banks, insurance companies, and investment institutions.

Meanwhile, as Keynes advised, governments also borrow and spend to create infrastructure and jobs, becoming the borrowers and spenders of last resort during recessions. A non-trivial example: In the US since World War II, military spending has supported a substantial segment of the national economy — the weapons industries and various private military contractors — while directly providing hundreds of thousands of jobs, at any given moment, for soldiers and support personnel. Critics describe the system as a military-industrial “welfare state for corporations.”15

The upsides and downsides of the business cycle are reflected in higher or lower levels of inflation. Inflation is often defined in terms of higher wages and prices, but (as Austrian School economists have persuasively argued) wage and price inflation is actually just the symptom of an increase in the money supply relative to the amounts of goods and services being traded, which in turn is typically the result of exuberant borrowing and spending. Inflation causes each unit of currency to lose value. The downside of the business cycle, in the worst instance, can produce the opposite of inflation, or deflation. Deflation manifests as declining wages and prices, due to a declining money supply relative to goods and services traded (which causes each unit of currency to increase in purchasing power), itself due to a contraction of borrowing and spending or to widespread defaults.

Business cycles, and regulated monetary and banking systems, constitute the framework within which companies, investors, workers, and consumers act. But over the past few decades something remarkable has happened within that framework. In the US, the financial services industry has ballooned to unprecedented proportions, and has plunged society as a whole into a crisis of still-unknown proportions. How and why did this happen? As we are about to see, these recent developments have deep roots.

Mad Money

Investing is a practice nearly as old as money itself, and from the earliest times motives for investment were two-fold: to share in profits from productive enterprise, and to speculate on anticipated growth in the value of assets. The former kind of investment is generally regarded as helpful to society, while the latter is seen, by some at least, as a form of gambling that eventually results in wasteful destruction of wealth. It is important to remember that the difference between the two is not always clear-cut, as investment always carries risk as well as an expectation of reward.16

Here are obvious examples of the two kinds of investment motive. If you own shares of stock in General Motors, you own part of the company; if it does well, you are paid dividends — in “normal” times, a modest but steady return on your investment. If dividends are your main objective, you are likely to hold your GM stock for a long time, and if most others who own GM stock have bought it with similar goals, then — barring serious mismanagement or a general economic downturn — the value of the stock is likely to remain fairly stable. But suppose instead you bought shares of a small start-up company that is working to perfect a new oil-drilling technology. If the technology works, the value of the shares could skyrocket long before the company actually shows a profit. You could then dump your shares and make a killing. If you’re this kind of investor, you are more likely to hold shares relatively briefly, and you are likely to gravitate toward stocks that see rapid swings in value. You are also likely to be constantly on the lookout for information — even rumors — that could tip you off to impending price swings in particular stocks.

When lots of people engage in speculative investment, the likely result is a series of occasional manias or bubbles. A classic example is the 17th-century Dutch tulip mania, when trade in tulip bulbs assumed bubble proportions; at its peak in early February 1637, some single tulip bulbs sold for more than ten times the annual income of a skilled craftsman.17 Just days after the peak, tulip bulb contract prices collapsed and speculative tulip trading virtually ceased. More recently, in the 1920s, radio stocks were the bubble du jour while the dot-com or Internet bubble ran its course a little over a decade ago (1995–2000).

Given the evident fact that bubbles tend to burst, resulting in a destruction of wealth sometimes on an enormous and catastrophic scale, one might expect that governments would seek to restrain the riskier versions of speculative investing through regulation. This has indeed been the case in historic periods immediately following spectacular crashes. For example, after the 1929 stock market crash regular commercial banks (which accept deposits and make loans) were prohibited from acting as investment banks (which deal in stocks, bonds, and other financial instruments). But as the memory of a crash fades, such restraints tend to fall away.

Moreover, investors are always looking for creative ways to turn a profit — sometimes by devising new methods that are not yet constrained by regulations. A few of these methods were particularly instrumental in the build-up to the 2007–2008 crisis. As we discuss them, we will also define some crucial terms.

Let’s start with leverage — a general term for any way to multiply investment gains or losses. A bit of history helps in understanding the concept. During the 1920s, partly because the Fed was keeping interest rates low, investors found they could borrow money to buy stocks, then make enough of a profit in the buoyant stock market to repay their debt (with interest) and still come out ahead. This was called buying on margin, and it is a classic form of leverage. Unfortunately, when worries about higher interest rates and falling real estate prices helped trigger the stock market crash of October 1929, margin investors found themselves owing enormous sums they couldn’t repay. The lesson: leverage can multiply profits, but it likewise multiplies losses.18

Two important ways to attain leverage are by borrowing money and trading securities. An example of the former: A public corporation (i.e., one that sells stock) may leverage its equity by borrowing money. The more it borrows, the fewer dividend-paying stock shares it needs to sell to raise capital, so any profits or losses are divided among a smaller base and are proportionately larger as a result. The company’s stock looks like a better buy and the value of shares may increase. But if a corporation borrows too much money, a business downturn might drive it into bankruptcy, while a less-leveraged corporation might prove more resilient.

In the financial world, leverage is mostly achieved with securities. A security is any fungible, negotiable financial instrument representing value. Securities are generally categorized as debt securities (such as bonds and debentures), equity securities (such as common stocks), and derivative contracts.

Debt and equity securities are relatively easy to explain and understand; derivatives are another story. A derivative is an agreement between two parties that has a value that is determined by the price movement of something else (called the underlying). The underlying can consist of stock shares, a currency, or an interest rate, to cite three common examples. Since a derivative can be placed on any sort of security, the scope of possible derivatives is nearly endless. Derivatives can be used either to deliberately acquire risk (and increase potential profits) or to hedge against risk (and reduce potential losses). The most widespread kinds of derivatives are options (financial instruments that give owners the right, but not the obligation, to engage in a specific transaction on an asset), futures (a contract to buy or sell an asset at a future date at a price agreed today), and swaps (in which counterparties exchange certain benefits of one party’s financial instrument for those of the other party’s financial instrument).

Derivatives have a fairly long history: rice futures have been traded on the Dojima Rice Exchange in Osaka, Japan since 1710. However, they have more recently attracted considerable controversy, as the total nominal value of outstanding derivatives contracts has grown to colossal proportions — in the hundreds of trillions of dollars globally, according to some estimates. Prior to the crash of 2008, investor Warren Buffett famously called derivatives “financial weapons of mass destruction,” and asserted that they constitute an enormous bubble. Indeed, during the 2008 crash, a subsidiary of the giant insurance company AIG lost more than $18 billion on a type of swap known as a credit default swap, or CDS (essentially an insurance arrangement in which the buyer pays a premium at periodic intervals in exchange for a contingent payment in the event that a third party defaults). Société Générale lost $7.2 billion in January of the same year on futures contracts.

Often, mundane financial jargon conceals truly remarkable practices. Take the common terms long and short for example. If a trader is “long” on oil futures, for example, that means he or she is holding contracts to buy or sell a specified amount of oil at a specified future date at a price agreed today, in expectation of a rise in price. One would therefore naturally assume that taking a “short” position on oil futures or anything else would involve expectation of a falling price. True enough. But just how does one successfully go about investing to profit on assets whose value is declining? The answer: short selling (also known as shorting or going short), which involves borrowing the assets (usually securities borrowed from a broker, for a fee) and immediately selling them, waiting for the price of those assets to fall, buying them back at the depressed price, then returning them to the lender and pocketing the price difference. Of course, if the price of the assets rises, the short seller loses money. If this sounds dodgy, then consider naked short selling, in which the investor sells a financial instrument without bothering first to buy or borrow it, or even to ensure that it can be borrowed. Naked short selling is illegal in the US, but many knowledgeable commentators assert that the practice is widespread nonetheless.

In the boom years leading up to the 2007–2008 crash, it was often the wealthiest individuals who engaged in the riskiest financial behavior. And the wealthy seemed to flock, like finches around a bird feeder, toward hedge funds: investment funds that are open to a limited range of investors and that undertake a wider range of activities than traditional “long-only” funds invested in stocks and bonds — activities including short selling and entering into derivative contracts. To neutralize the effect of overall market movement, hedge fund managers balance portfolios by buying assets whose price is expected to outpace the market, and by short-selling assets expected to do worse than the market as a whole. Thus, in theory, price movements of particular securities that reflect overall market activity are cancelled out, or “hedged.” Hedge funds promise (and often produce) high returns through extreme leverage. But because of the enormous sums at stake, critics say this poses a systemic risk to the entire economy. This risk was highlighted by the near-collapse of two Bear Stearns hedge funds, which had invested heavily in mortgage-backed securities, in June 2007.19

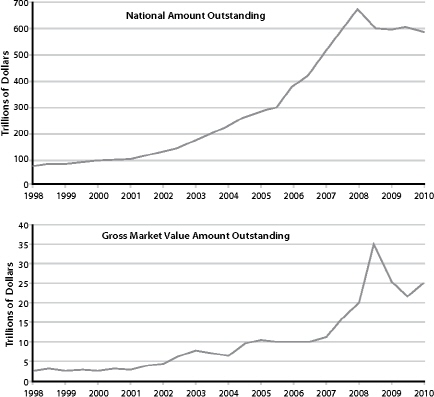

FIGURE 9. Amounts Outstanding of Over the Counter (OTC) Derivatives since 1998 in G10 Countries and Switzerland. “Notional value” refers to the total value of a leveraged position’s assets. The term is commonly used in the options, futures, and currency markets when a small amount of invested money controls a large position (and has a large consequence for the trader). “Market value” refers to how much derivatives contracts would be worth if they had to be settled at a given moment.

Source: Bank for International Settlements.

I Owe You

As we have seen, bubbles are a phenomenon generally tied to speculative investing. But in a larger sense our entire economy has assumed the characteristics of a bubble or a Ponzi scheme. That is because it has come to depend upon staggering and continually expanding amounts of debt: government and private debt; debt in the trillions, and tens of trillions, and hundreds of trillions of dollars; debt that, in aggregate, has grown by 500 percent since 1980; debt that has grown faster than economic output (measured in GDP) in all but one of the past 50 years; debt that can never be repaid; debt that represents claims on quantities of labor and resources that simply do not exist.

When we inquire how and why this happened, we discover a web of interrelated trends.

Looking at the problem close up, the globalization of the economy looms as a prominent factor. In the 1970s and ’80s, with stiffer environmental and labor standards to contend with domestically, corporations began eyeing the regulatory vacuum, cheap labor, and relatively untouched natural resources of less-industrialized nations as a potential goldmine. International investment banks started loaning poor nations enormous sums to pay for ill-advised infrastructure projects (and, incidentally, to pay kickbacks to corrupt local politicians), later requiring these countries to liquidate their natural resources at fire-sale prices so as to come up with the cash required to make loan payments. Then, prodded by corporate interests, industrialized nations pressed for the liberalization of trade rules via the World Trade Organization (the new rules almost always subtly favored the wealthier trading partner). All of this led predictably to a reduction of manufacturing and resource extraction in core industrial nations, especially the US (many important resources were becoming depleted in the wealthy industrial nations anyway), and a steep increase in resource extraction and manufacturing in several “developing” nations, principally China. Reductions in domestic manufacturing and resource extraction in turn motivated investors within industrial nations to seek profits through purely financial means. As a result of these trends, there are now as many Americans employed in manufacturing as there were in 1940, when the nation’s population was roughly half what it is today, while the proportion of total US economic activity deriving from financial services has tripled during the same period. Speculative investing has become an accepted practice that is taught in top universities and institutionalized in the world’s largest corporations.

But as we back up to take in a wider view, we notice larger and longer-term trends that have played even more important roles. One key factor was the severance of money from its moorings in precious metals, a process that started over a century ago. Once money came to be based on debt (so that it was created primarily when banks made loans), growth in total outstanding debt became a precondition for growth of the money supply and therefore for economic expansion. With virtually everyone —workers, investors, politicians — clamoring for more economic growth, it was inevitable that innovative ways to stimulate the process of debt creation would be found. Hence the fairly recent appearance of a bewildering array of devices for borrowing, betting, and insuring — from credit cards to credit default swaps — all essentially tools for the “ephemeralization” of money and the expansion of debt.

A Marxist would say that all of this flows from the inherent imperatives of capitalism. A historian might contend it reflects the inevitable trajectory of all empires (though past empires didn’t have fossil fuels and therefore lacked the means to become global in extent). And a cultural anthropologist might point out that the causes of our debt spiral are endemic to civilization itself: as the gift economy shrank and trade grew, the infinitely various strands of mutual obligation that bind together every human community became translated into financial debt (and, as hunter-gatherers intuitively understood, debts within the community can never fully be repaid — nor should they be; and certainly not with interest).

In the end perhaps the modern world’s dilemma is as simple as “What goes up must come down.” But as we experience the events comprising ascent and decline close up and first-hand, matters don’t appear simple at all. We suffer from media bombardment; we’re soaked daily in unfiltered and unorganized data; we are blindingly, numbingly overwhelmed by the rapidity of change. But if we are to respond and adapt successfully to all this change, we must have a way of understanding why it is happening, where it might be headed, and what we can do to achieve an optimal outcome under the circumstances. If we are to get it right, we must see both the forest (the big, long-term trends) and the trees (the immediate challenges ahead).

Which brings us to a key question: If the financial economy cannot continue to grow by piling up more debt, then what will happen next?

BOX 1.3 The Magic of Compound Interest

Suppose you have $100. You decide to put it into a savings account that pays you 5 percent interest. After the first year, you have $105. You leave the entire amount in the bank, so at the end of the second year you are collecting 5 percent interest not on $100, but on $105 — which works out to $5.25. So now you have $110.25 in your account. At first this may not seem all that remarkable. But just wait. After three years you have $115.76, then $121.55, then $127.63, then $134.01. After ten years you would have $162.88, and at the end of fourteen years you would have nearly doubled your initial investment. After 29 years you would have about $400, and if you could manage to leave your investment untouched for forty-three years you would have nearly $800. After eighty-six years your heirs could collect $3,200, and after a full century had passed your initial $100 deposit would have grown to nearly $6,200. Of course, if this were a debt rather than an investment, interest would compound similarly.

Somehow these claims on real wealth (goods and services) have multiplied, while the world’s stores of natural resources have in many cases actually declined due to depletion of fossil fuels and minerals, or the over-harvesting of forests and fish. Money, if invested or loaned, has the “right” to increase, while nature enjoys no such imperative.

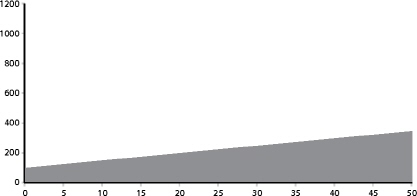

FIGURE 10. Additive growth. Here we see an additive growth rate of 5. Beginning with 100, we add 5, and then add 5 to that sum, and so on. After 50 transactions we arrive at 350.

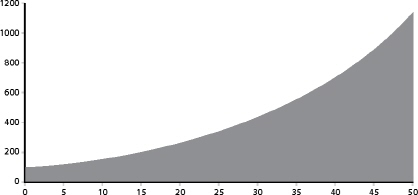

FIGURE 11. Compounded growth. This graph shows a compound growth rate of 5 percent, which means we start by multiplying 100 by 5 percent and then add the product to the original 100. Then we multiply that sum by 5 percent and add the product to the original sum, and so on. After 50 transactions, we arrive at 1147.