THE SONG OF AMERGIN

I suggest in the first part of this argument that the ‘I am’ and ‘I have been’ sequences frequent in ancient Welsh and Irish poetry are all variants of the same calendar theme. Here, for instance, is the ‘Song of Amergin’ (or Amorgen) said to have been chanted by the chief bard of the Milesian invaders, as he set his foot on the soil of Ireland, in the year of the world 2736 (1268 BC). Unfortunately the version which survives is only a translation into colloquial Irish from the Old Goidelic. Dr. Macalister pronounces it ‘a pantheistic conception of a Universe where godhead is everywhere and omnipotent’ and suggests that it was a liturgical hymn of as wide a currency as, say, the opening chapters of the Koran, or the Apostles’ Creed. He writes: ‘Was it of this hymn, or of what he had been told of the contents of this hymn, that Caesar was thinking when he wrote: “The Druids teach of the stars and their motions, the world, the size of lands, natural philosophy and the nature of the gods”?’ He notes that the same piece ‘in a garbled form’ is put into the mouth of the Child-bard Taliesin when narrating his transformations in previous existences. Sir John Rhys pointed out in his Hibbert Lectures that many of Gwion’s ‘I have been’s’ imply ‘not actual transformation but mere likeness, through a primitive formation of a predicate without the aid of a particle corresponding to such a word as “like”.’

The Song of Amergin begins with thirteen statements, provided with mediaeval glosses. The thirteen statements are followed by six questions, also provided with glosses. These are followed in Professor John MacNeill’s version by an envoie in which the Druid advises the People of the Sea to invoke the poet of the sacred rath to give them a poem. He himself will supply the poet with the necessary material, and together they will compose an incantation.

| THE SONG OF AMERGIN | |

| God speaks and says: | Glosses |

| I am a wind of the sea, | for depth |

| I am a wave of the sea, | for weight |

| I am a sound of the sea, | for horror |

| I am an ox of seven fights, | for strength |

| or I am stag of seven tines, | |

| I am a griffon on a cliff, | for deftness |

| or I am a hawk on a cliff, | |

| I am a tear of the sun, | ‘a dew-drop’ – for clearness |

| I am fair among flowers, | |

| I am a boar, | for valour |

| I am a salmon in a pool, | ‘the pools of knowledge’ |

| I am a lake on a plain, | for extent |

| I am a hill of poetry, | ‘and knowledge’ |

| I am a battle-waging spear, | |

| I am a god who forms fire for a head. | [i.e. ‘gives inspiration: Macalister] |

| or I am a god who forms smoke from sacred fire for a head. | ‘to slay therewith’ |

***

| 1. | Who makes clear the ruggedness of the

mountains? or Who but myself knows the assemblies of the dolmen-house on the mountain of Slieve Mis? |

‘Who but myself will resolve every question?’ |

| 2. | Who but myself knows where the sun shall set? | |

| 3. | Who foretells the ages of the moon? | |

| 4. | Who brings the cattle from the House of Tethra and segregates them? | [i.e. ‘the fish’, Macalister, i.e. ‘the stars’, MacNeill] |

| 5. | On whom do the cattle of Tethra

smile? or For whom but me will the fish of the laughing ocean be making welcome? |

|

| 6. | Who shapes weapons from hill to hill? | ‘wave to wave, letter to letter, point to point’ |

***

Invoke, People of the Sea, invoke the poet, that he may compose a spell for you.

For I, the Druid, who set out letters in Ogham,

I, who part combatants,

I will approach the rath of the Sidhe to seek a cunning poet that together we may concoct incantations.

I am a wind of the sea.

Tethra was the king of the Undersea-land from which the People of the Sea were later supposed to have originated. He is perhaps a masculinization of Tethys, the Pelasgian Sea-goddess, also known as Thetis, whom, Doge-like, Peleus the Achaean married at Iolcus in Thessaly. The Sidhe are now popularly regarded as fairies: but in early Irish poetry they appear as a real people – a highly cultured and dwindling nation of warriors and poets living in the raths, or round stockaded forts, of which New Grange on the Boyne is the most celebrated. All had blue eyes, pale faces and long curly yellow hair. The men carried white shields, and were organized in military companies of fifty. They were ruled over by two virgin-born kings and were sexually promiscuous but ‘without blame or shame’. They were, in fact, Picts (tattooed men) and all that can be learned about them corresponds with Xenophon’s observations in his Anabasis on the primitive Mosynoechians (‘wooden-castle dwellers’) of the Black Sea coast. The Mosynoechians were skilfully tattooed, carried long spears and ivy-leaf shields made from white ox-hide, were forest dwellers, and performed the sexual act in public. They lived in the stockaded forts from which they took their name, and in Xenophon’s time occupied the territory assigned in early Greek legend to the matriarchal Amazons. The ‘blue eyes’ of the Sidhe I take to be blue interlocking rings tattooed around the eyes, for which the Thracians were known in Classical times. Their pallor was also perhaps artificial – white ‘war-paint’ of chalk or powdered gypsum, in honour of the White Goddess, such as we know, from a scene in Aristophanes’s Clouds where Socrates whitens Strepsiades, was used in Orphic rites of initiation.

Slieve Mis is a mountain in Kerry.

‘Of seven tines’ probably means of seven points on each horn, fourteen in all: which make a ‘royal stag’. But royalty is also conceded to a stag of twelve points, and since a stag must be seven years old before it can have twelve points, ‘seven fights’ may refer to the years.

It is most unlikely that this poem was allowed to reveal its esoteric meaning to all and sundry; it would have been ‘pied’, as Gwion pied his poems, for reasons of security. So let us rearrange the order of statements in a thirteen-month calendar form, on the lines of the Beth-Luis-Nion, profiting from what we have learned about the mythic meaning of each letter-month:

| God speaks and says: | Trees of the month | |||

| Dec. 24-Jan. 20 | B | I am a stag of seven tines, or an ox of seven fights, | Birch | Beth |

| Jan. 21-Feb. 17 | L | I am a wide flood on a plain, | Quick-beam (Rowan) | Luis |

| Feb. 18-Mar. 17 | N | I am a wind on the deep waters, | Ash | Nion |

| Mar. 18-Apr. 14 | F | I am a shining tear of the sun, | Alder | Fearn |

| Apr. 15-May 12 | S | I am a hawk on a cliff, | Willow | Saille |

| May 13-Jun. 9 | H | I am fair among flowers, | Hawthorn | Uath |

| Jun. 10-July 7 | D | I am a god who sets the head afire with smoke, | Oak | Duir |

| July 8-Aug. 4 | T | I am a battle-waging spear, | Holly | Tinne |

| Aug. 5-Sept. 1 | C | I am a salmon in the pool, | Hazel | Coll |

| Sept. 2-Sept. 29 | M | I am a hill of poetry, | Vine | Muin |

| Sept. 30-Oct. 27 | G | I am a ruthless boar, | Ivy | Gort |

| Oct. 28-Nov. 24 | NG | I am a threatening noise, | Reed | Ngetal |

| Nov. 25-Dec. 22 | R | I am a wave of the sea, | Elder | Ruis |

| Dec. 23 | Who but I knows the secrets of the unhewn dolmen? |

There can be little doubt as to the appropriateness of this arrangement. B is the Hercules stag (or wild bull) which begins the year. The seven fights, or seven tines of his antlers, are months in prospect and in retrospect: for Beth is the seventh month after Duir the oak-month, and the seventh month from Beth is Duir again. The ‘Boibalos’ of the Hercules charm contained in the Boibel-Loth was an antelope-bull. The Orphic ‘ox of seven fights’ is hinted at in Plutarch’s Isis and Osiris, where he describes how at the Winter solstice they carry the golden cow of Isis, enveloped in black cloth, seven times around the shrine of Osiris, whom he identifies with Dionysus. ‘The circuit is called “The Seeking for Osiris”, for in winter the Goddess longs for the water of the Sun. And she goes around seven times because he completes his passing from the winter to the summer solstice in the seventh month.’ Plutarch must be reckoning in months of 28 days, not 30, else the passage would be completed in the sixth of them.

L is February Fill-Dyke, season of floods.

N is centred in early March, which ‘comes in like a lion’ with winds that dry the floods.

F is explained by the sentiment of the well-known mediaeval carol:

He came all so still

Where his mother was,

Like dew in April

That falleth on grass.

For this is the true beginning of the sacred year, when the deer and wild cow drop their young, and when the Child Hercules is born who was begotten at the mid-summer orgies. Hitherto he has been sailing in his coracle over the floods; now he lies glistening on the grass.

S is the month when birds nest. In Gwion’s Can y Meirch (‘Song of the Horses’), a partial series of ‘I have been’s’ occurs as an interpolation. One of them is: ‘I have been a crane on a wall, a wondrous sight.’ The crane was sacred to Delian Apollo and, before Apollo, to the Sun-hero Theseus. It also appears, in triad, in a Gaulish bas-relief at Paris, and in another at Trèves, in association with the god Esus and a bull. Crane, hawk, or vulture? That is an important question because the provenience of the poem depends on the answer. The hawk, if not the royal hawk of Egyptian Horus, will have been the kite sacred to Boreas the North Wind; in Greek legend his Thracian sons Calaïs and Zetes wore kite-feathers in his honour and had the power of transforming themselves into kites. These two birds are mythologically linked in the Egyptian hieroglyph for the North Wind, which is a hawk. In Welsh the word is barcut, and in Iranian the word is barqut, which supports Pliny’s suggestion (Natural History XXX, 13) of a strong connexion between the Persian and British sun-cults. Another mark of close similarity is that Mithras, the Persian Sun-god whose birthday was celebrated at the Winter solstice, was worshipped as a bull of seven fights: his initiates having to go through seven grades before they were sealed on the brow as ‘tried soldiers of Mithras’. Mithraism was a favourite cult of the Roman legionaries in Imperial times, but they never reached Ireland, and the Song of Amergin is evidently far older than the Claudian invasion of Britain. The vulture will have been the griffon-vulture sacred to Osiris, a bird also of great importance to the Etruscan augurs and with a wider wing-span than the golden eagle. In the Song of Moses (Deuteronomy XXXII, 11) Jehovah is identified with this bird, which is a proof that its ‘uncleanness’ in the Levitical list means sanctity, not foulness. The heraldic griffin is a lion with griffon-vultures’ wings and claws and represents the Sun-god as King of the earth and air. The ordinary Welsh word for hawk is Gwalch, akin to the Latin falco, falcon, and the court-bards always likened their royal patrons to it. The mystical names Gwalchmai (‘hawk of May’); Gwalchaved (‘hawk of summer’) better known as Sir Galahad; and Gwalchgwyn (‘white hawk’) better known as Sir Gawain, are best understood in terms of this calendar formula.

H, which starts in the second half of May, is the season of flowers, and the hawthorn, or may-tree, rules it. Olwen, the daughter of ‘Giant Hawthorn’, has already been mentioned. Her hair was yellow as the broom, her fingers pale as wood-anemones, her cheeks the colour of roses and from her footprints white trefoil sprang up – trefoil to show that she was the summer aspect of the old triple Goddess. This peculiarity gave her the name of Olwen – ‘She of the White Track’. Trefoil, by the way, was celebrated by the Welsh bards with praise out of all proportion to its beauty. Homer called it ‘the lotus’ and mentioned it as a rich fodder for horses.

D is ruled by the midsummer oak. The meaning is, I think, that the painful smoke of green oak gives inspiration to those who dance between the twin sacrificial fires lighted on Midsummer Eve. Compare the Song of the Forest Trees:

Fiercest heat-giver of all timber is green oak;

From him none may escape unhurt.

By love of him the head is set an-aching,

By his acrid embers the eye is made sore.

T is the spear month, the month of the tanist; the bardic character T was shaped like a barbed spear.

C is the nut month. The salmon was, and still is, the King of the river-fish, and the difficulty of capturing him, once he is lodged in a pool, makes him a useful emblem of philosophical retirement. Thus Loki, the Norse God of cunning, disguised himself from his fellow-gods as a salmon and was drawn from his pool only with a special net of his own design. The connexion of salmon with nuts and with wisdom has already been explained.

M is the initial of Minerva, Latin goddess of wisdom and inventor of numbers; of Mnemosyne, the Mother of the Greek Muses; and of the Muses themselves; and of the Moirae, or Fates, who are credited by some mythographers with the first invention of the alphabet. The vine, the prime tree of Dionysus, is everywhere associated with poetic inspiration. Wine is the poets’ proper drink, as Ben Jonson knew well when he asked for his fee as Poet Laureate to be paid in sack. The base Colley Cibber asked for a cash payment in lieu of wine, and no Poet Laureate since has been poet enough to demand a return to the old system of payment.

G, the ivy month, is also the month of the boar. Set, the Egyptian Sun-god, disguised as a boar, kills Osiris of the ivy, the lover of the Goddess Isis. Apollo the Greek Sun-god, disguised as a boar, kills Adonis, or Tammuz, the Syrian, the lover of the Goddess Aphrodite. Finn Mac Cool, disguised as a boar, kills Diarmuid, the lover of the Irish Goddess Grainne (Greine). An unknown god disguised as a boar kills Ancaeus the Arcadian King, a devotee of Artemis, in his vineyard at Tegea and, according to the Nestorian Gannat Busamé (‘Garden of Delights’), Cretan Zeus was similarly killed. October was the boar-hunting season, as it was also the revelry season of the ivy-wreathed Bassarids. The boar is the beast of death and the ‘fall’ of the year begins in the month of the boar.

NG is the month when the terrible roar of breakers and the snarling noise of pebbles on the Atlantic seaboard fill the heart with terror, and when the wind whistles dismally through the reed-beds of the rivers. In Ireland the roaring of the sea was held to be prophetic of a king’s death. The warning also came with the harsh cry of the scritch-owl. Owls are most vocal on moonlight nights in November and then remain silent until February. It is this habit, with their silent flight, the carrion-smell of their nests, their diet of mice, and the shining of their eyes in the dark, which makes owls messengers of the Death-goddess Hecate, or Athene, or Persephone: from whom, as the supreme source of prophecy, they derive their reputation for wisdom.

R is the month when the wave returns to the sea, and the end of the year to its watery beginning. A wave of the sea in Irish and Welsh poetry is a ‘sea-stag’: so that the year begins and ends with the white roebuck. In Irish legend such gods of the year as Cuchulain and Fionn fight the waves with sword and spear.

The corresponding text in the Romance of Taliesin is scattered rather than garbled.

| B | I have been a fierce bull and a yellow buck. | |

| L | I have been a boat on the sea. | |

| N | I fled vehemently…on the foam of water. | |

| F | I have been a drop in the air. | |

| S | I journeyed as an eagle. | |

| H | God made me of blossom. | |

| D | I have been a tree-stump in a shovel. | |

| T | I fled as a spear-head of woe to such as wish for woe. | |

| C | I have been a blue salmon. | |

| M | I have been a spotted snake on a hill. | |

| G | I fled as a bristly boar seen in a ravine. | |

| NG | I have been a wave breaking on the beach. | |

| R | On a boundless sea I was set adrift. |

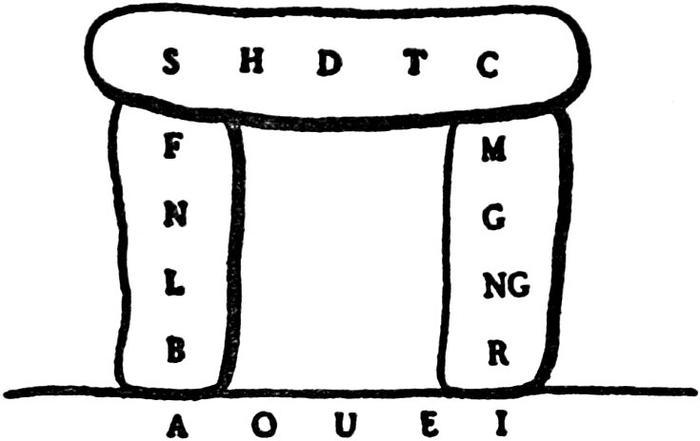

The clue to the arrangement of this alphabet is found in Amergin’s reference to the dolmen; it is an alphabet that best explains itself when built up as a dolmen of consonants with a threshold of vowels. Dolmens are closely connected with the calendar in the legend of the flight of Grainne and Diarmuid from Finn Mac Cool. The flight lasted for a year and a day, and the lovers bedded together beside a fresh dolmen every night. Numerous ‘Beds of Diarmuid and Grainne’ are shown in Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary and the West, each of them marked by a dolmen. So this alphabet dolmen will also serve as a calendar, with one post for Spring, the other for Autumn, the lintel for Summer, the threshold for New Year’s Day. Thus:

At once one sees the reference to S as a hawk, or griffon, on the cliff; and to M as the hill of poetry or inspiration – a hill rooted in the death letters R and I and surmounted by the C of wisdom. So the text of the first part of Amergin’s song may be expanded as follows:

God speaks and says:

I am a stag of seven tines.

Over the flooded world

I am borne by the wind.

I descend in tears like dew, I lie glittering,

I fly aloft like a griffon to my nest on the cliff,

I bloom among the loveliest flowers,

I am both the oak and the lightning that blasts it.

I embolden the spearman,

I teach the councillors their wisdom,

I inspire the poets,

I rove the hills like a conquering boar,

I roar like the winter sea,

I return like the receding wave.

Who but I can unfold the secrets of the unhewn dolmen?

For if the poem really consists of two stanzas, each of two triads, ending with a single authoritative statement, then the first ‘Who but I?’ (which does not match the other five) is the conclusion of the second stanza, and is uttered by the New Year God. This Child is represented by the sacred threshold of the dolmen, the central triad of vowels, namely O.U.E. But one must read O.U.E. backwards, the way of the sun, to make sense of it. It is the sacred name of Dionysus, EUO, which in English is usually written ‘EVOE’.

It is clear that ‘God’ is Celestial Hercules again, and that the child-poet Taliesin is a more appropriate person to utter the song than Amergin, the leader of the Milesians, unless Amergin is speaking as a mouth-piece of Hercules.

There is a mystery connected with the line ‘I am a shining tear of the sun’, because Deorgreine, ‘tear of the Sun’, is the name of Niamh of the Golden Hair, the lovely goddess mentioned in the myth of Laegaire mac Crimthainne. Celestial Hercules when he passes into the month F, the month of Bran’s alder, becomes a maiden. This recalls the stories of such sun-heroes as Achilles1, Hercules and Dionysus who lived for a time disguised as girls in the women’s quarters of a palace and plied the distaff. It also explains the ‘I have been a maiden’, in a series corresponding with the Amergin cycle, ascribed to Empedocles the fifth-century BC. mystical philosopher. The sense is that the Sun is still under female tutelage for half of this month – Cretan boys not yet old enough to bear arms were called Scotioi, members of the women’s quarters – then, like Achilles, he is given arms and flies off royally like a griffon or hawk to its nest.

But why a dolmen? A dolmen is a burial chamber, a ‘womb of Earth’, consisting of a cap-stone supported on two or more uprights, in which a dead hero is buried in a crouched position like a foetus in the womb, awaiting rebirth. In spiral Castle (passage-burial), the entrance to the inner chamber is always narrow and low in representation of the entrance to the womb. But dolmens are used in Melanesia (according to Prof. W. H. R. Rivers) as sacred doors through which the totem-clan initiate crawls in a ceremony of rebirth; if, as seems likely, they were used for the same purpose in ancient Britain, Gwion is both recounting the phases of his past existence and announcing the phases of his future existence. There is a regular row of dolmens on Slieve Mis. They stand between two baetyls with Ogham markings, traditionally sacred to the Milesian Goddess Scota who is said to be buried there; alternatively, in the account preserved by Borlase in his Dolmens of Ireland, to ‘Bera a queen who came from Spain’. But Bera and Scota seem to be the same person, since the Milesians came from Spain. Bera is otherwise known as the Hag Of Beara.

The five remaining questions correspond with the five vowels, yet they are not uttered by the Five-fold Goddess of the white ivy-leaf, as one would expect. They must have been substituted for an original text telling of Birth, Initiation, Love, Repose, Death, and can be assigned to a later bardic period. In fact, they correspond closely with the envoi to the first section of the tenth-century Irish Saltair No Rann, which seems to be a Christianized version of a pagan epigram.

For each day five items of knowledge

Are required of every understanding person –

From everyone, without appearance of boasting,

Who is in holy orders.

The day of the solar month; the age of the moon;

The state of the sea-tide, without error;

The day of the week; the calendar of the feasts of the perfect saints

In just clarity with their variations.

For ‘perfect saints’ read ‘blessed deities’ and no further alteration is needed. Compare this with Amergin’s:

Who but myself knows where the sun shall set?

Who foretells the ages of the moon?

Who brings the cattle from the house of Tethra and segregates them?

On whom do the cattle of Tethra smile?

Who shapes weapons from hill to hill, wave to wave,

letter to letter, point to point?

The first two questions in the Song of Amergin, about the day of the solar month and the ages of the moon, coincide with the first two items of knowledge in the Saltair: ‘Who knows when the Sun shall set?’ means both ‘who knows the length of the hours of daylight at any given day of the year?’ – a problem worked out in exhaustive detail by the author of The Book of Enoch – and ‘Who knows on any given day how long the particular solar month in which it occurs will last?’

The third question is ‘Who brings the cattle of Tethra (the heavenly bodies) out of the ocean and puts each in his due place?’ This assumes a knowledge: of the five planets, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, Saturn, which, with the Sun and Moon, had days of the week allotted to them in Babylonian astronomy, and still keep them in all European languages. Thus it corresponds with ‘the day of the week’.

The fourth question, as the glossarist explains, amounts to ‘Who is lucky in fishing?’ This corresponds with ‘the state of the sea tide’; for a fisherman who does not know what tide to expect will have no fishing luck.

The fifth question, read in the light of its gloss, amounts to: ‘Who orders the calendar from the advancing wave B to the receding wave R; from one calendar month to the next; from one season of the year to the next?’ (The three seasons of Spring, Summer and Autumn are separated by points, or angles, of the dolmen.) So it corresponds with ‘the calendar of the feasts of the perfect saints.’

Another version of the poem found in The Book of Leacon and The Book of the O’Clerys, runs as follows when restored to its proper order. The glosses are similar in both books, though the O’Clerys’ are the more verbose.

| B | I am seven battalions or I am an ox in strength – for strength | |

| L | I am a flood on a plain – for extent | |

| N | I am a wind on the sea – for depth | |

| F | I am a ray of the sun – for purity | |

| S | I am a bird of prey on a cliff – for cunning | |

| H | I am a shrewd navigator – | |

| D | I am gods in the power of transformation – I am a god, a druid, and a man who creates fire from magical smoke for the destruction of all, and makes magic on the tops of hills | |

| T | I am a giant with a sharp sword, hewing down an army – in taking vengeance | |

| C | I am a salmon in a river or pool – for power | |

| G | I am a fierce boar – for powers of chieftain-like valour | |

| NG | I am the roaring of the sea – for terror | |

| R | I am a wave of the sea – for might |

This seems a later version, since the T-month is awarded a sword, not the traditional spear; and the original wording of the D-line is recalled in a gloss; and ‘Who but I knows the secrets of the unhewn dolmen?’ is omitted. Another change of importance is that the H-month is described in terms of navigation, not flowers. May 14th marked the beginning of the deep-sea fishing in ancient Ireland when the equinoctial gales had subsided and it was safe to put to sea in an ox-hide curragh; but the ascetic meaning of Hawthorn is a reminder of the ban against taking women on a fishing trip. The additions to the poem show, even more clearly than Macalister’s text, that it was preserved as a charm for successful fishing both in river and sea; the Druid being paid by the fishermen for repeating it and threatening the water with javelin-vengeance if a curagh were to be lost: –

Whither shall we go? Shall we debate in valley or on peak?

Where shall we dwell? In what nobler land than the isle of Sunset?

Where else shall we walk in peace, to and fro, on fertile ground?

Who but I can take you to where the stream runs, or falls, clearest?

Who but I tell you the age of the moon?

Who but I can bring you Tethra’s cattle from the recesses of the sea?

Who but I can draw Tethra’s cattle shoreward?

Who can change the hills, mountains or promontories as I can?

I am a cunning poet who invokes prophecy at the entreaty of seafarers.

Javelins shall be wielded to revenge the loss of our ships.

I sing praises, I prophesy victory.

In closing my poem I desire other preferments, and shall obtain them.

The original five-lined pendant to the poem may have run something like this:

| A | I am the womb of every holt, | |

| O | I am the blaze on every hill, | |

| U | I am the queen of every hive, | |

| E | I am the shield to every head, | |

| I | I am the tomb to every hope. |

How or why this alphabet of thirteen consonants gave place to the alphabet of fifteen consonants is another question, the solution of which will be helped by a study of Latin and Greek alphabet legends.

*

That the first line of the Song of Amergin has the variant readings ‘stag of seven tines’ and ‘ox of seven fights’ suggests that in Ireland during the Bronze Age, as in Crete and Greece, both stag and bull were sacred to the Great Goddess. In Minoan Crete the bull became dominant as the Minotaur, ‘Bull-Minos’, but there was also a Minelaphos, ‘Stag-Minos’, who figured in the cult of the Moon-goddess Britomart, and a Minotragos, ‘Goat-Minos’ cult. The antlers found in the burial at New Grange suggest that the stag was the royal beast of the Irish Danaans, and the stag figures prominently in Irish myth: an incident in The Cattle Raid of Cuailgne, part of the Cuchulain saga, shows that a guild of deer-priests called ‘The Fair Lucky Harps’ had their headquarters at Assaroe in Donegal. Oisin was born of the deer-goddess Sadb and at the end of his life, when mounted on the fairy-steed of Niamh of the Golden Hair and sped by the wailing of the Fenians to her island paradise, he was shown a vision: a hornless fawn pursued over the waters of the sea by the red-eared white hounds of Hell. The fawn was himself. There is a parallel to this in the Romance of Pwyll Prince of Dyfed: Pwyll goes out hunting and meets Arawn King of Annwm mounted on a pale horse hunting a stag with his white, red-eared hounds. In recognition of Pwyll’s courtesy, Arawn, though sending him down to Annwm – for the stag is Pwyll’s soul – permits him to reign there in his stead. Another parallel is in the Romance of Math the Son of Mathonwy: Llew Llaw in the company of the faithless Blodeuwedd sees a stag being baited to death: it is his soul, and almost immediately afterwards he is put to death by her lover Gronw.

The fate of the antlered king – of whom Cernunnos, ‘the horned one’ of Gaul, is a familiar example – is expressed in the early Greek myth of Actaeon whom Artemis metamorphosed into a stag and hunted to death with her dogs. She did this at her anodos, or yearly reappearance, when she refreshed her virginity by bathing naked in a sacred fountain; after which she took another lover. The Irish Garbh Ogh with her pack of hounds was the same goddess: her diet was venison and eagles’ breasts. This ancient myth of the betrayed stag-king survives curiously in the convention, which is British as well as Continental, that gives the cuckold a branching pair of antlers. The May-day stag-mummers of Abbot’s Bromley in Staffordshire are akin to the stag-mummers of Syracuse in ancient Sicily, and to judge from an epic fragment concerned with Dionysus, one of the mummers disguised as an Actaeon stag was originally chased and eaten. In the Lycaean precinct of Arcadia the same tradition of the man dressed in deer skins who is chased and eaten survived in Pausanias’s day, though the chase was explained as a punishment for trespassing. From Sardinia comes a Bronze Age figurine of a man-stag with horns resembling the foliage of an oak, a short tail, an arrow in one hand and in the other a bow that has turned into a wriggling serpent. His mouth and eyes express an excusable terror at the sight; for the serpent is death. That the stag was part of the Elysian oracular cult is shown in the story of Brut the Trojan’s visit to the Island of Leogrecia, where the moon-oracle was given him while sleeping in the newly-flayed hide of a white hart whose blood had been poured on the sacrificial fire.

The stag-cult is far older than the Cretan Minelaphos: he is shown in palaeolithic paintings in the Spanish caves of Altamira and in the Caverne des Trois Frères at Ariège in the French Pyrenees, dating from at least 20,000 BC. The Altamiran paintings are the work of the Aurignacian people, who have also left records of their ritual in the caves of Domboshawa, and elsewhere in Southern Rhodesia. At Domboshawa a ‘Bushman’ painting, containing scores of figures, shows the death of a king who wears an antelope mask and is tightly corseted; as he dies, with arms outflung and one knee upraised, he ejaculates and his seed seems to form a heap of corn. An old priestess lying naked beside a cauldron is either mimicking his agony, or perhaps inducing it by sympathetic magic. Close by, young priestesses dance beside a stream, surrounded by clouds of fruit and heaped baskets; beasts are led off laden with fruit; and a huge bison bull is pacified by a priestess accompanied by an erect python. The cults of stag and bull were evidently combined at Domoshawa; but the stag is likely to have been the more royal beast, since the dying king is given the greater prominence. The cults were also combined by the Aurignacians. In a Dordogne cave painting a bull-man is shown dancing and playing a musical instrument shaped like a bow.

The Minotragos goat-cult in Crete seems to have been intermediate between the cults of Minelaphos and Minotaur. Amalthea, the nurse of Cretan Zeus, was a goat. The Goddess Athene carried an aegis (‘goatskin’) shield, made it was said from Amalthea’s hide which had been previously used by her father Zeus as a prophylactic coat. The Goddess Libya appeared in triad to Jason on the shores of Lake Triton, Athene’s birthplace, when the Argo was landlocked there, and was clad in goatskins; she thereby identified herself with Aega, sister of Helice (‘willow branch’) and daughter of a king of Crete – Aega who was the human double of the goat Amalthea; and with Athene herself. The tradition of the Libyan origin of Athene is supported by a comparison of Greek and Roman methods of augury. In Libya the year begins in the autumn with the winter rains and the arrival of birds from the North; but in Northern Europe and the Black Sea area it begins in Spring with the arrival of birds from the South. In most Greek states the year began in the autumn and the Greek augurs faced north when observing birds, presumably because they derived their tradition from the birth-place of Athene, patroness of augury. On the other hand, the Roman augurs faced south, presumably because the Dardanians (whose patrician descendants in the early Roman Republic were alone permitted to take auguries) had migrated from the Black Sea area where birds arrive from Palestine and Syria in the Spring. The Roman year began in the Spring.

The goat-Dionysus, or Pan, was a powerful deity in Palestine. He may have come there from Libya by way of Egypt or taken a roundabout northern route by way of Crete, Thrace, Asia Minor and Syria. The Day of Atonement scape-goat was a left-handed sacrifice to him under the name of Azazel, and the source of the Jordan was a grotto sacred to him as Baal Gad, the goat king, eponymous ancestor of the tribe of Gad. The prohibition in Deuteronomy XIV against seething a kid in its mother’s milk is puzzling only if sentimentally read; it is clearly written in the severe style of the remainder of the chapter, which begins with a prohibition against self-disfigurement at funerals, and directed against a eucharistic rite no longer tolerated by the priesthood of Jehovah. The clue is to be found in the well-known Orphic formula:

Like a kid I have fallen into milk

which was a password for initiates when they reached Hades and were challenged by the guardians of the dead. They had become one with The Kid, that is to say the immortal Dionysus, originally Cretan Zagreus or Zeus, by partaking of his flesh, and with the Goat-goddess, his mother, in whose cauldron and milk he had been seethed.1 A song about the birth of the gods on one of the recently discovered Ras Shamra tablets contains an express injunction to seethe a kid in its mother’s milk.

The prohibition in Deuteronomy explains the glib and obviously artificial myth of Esau, Jacob, Rebeccah and the blessing of Isaac, which is introduced into Genesis XXVII to justify the usurpation by the Jacob tribe of priestly and royal prerogatives belonging to the Edomites. The religious picture iconotropically2 advanced in support of the myth seems to have illustrated the kid-eating ceremony in Azazel’s honour. Two celebrants wearing goatskin disguises are shown at a seething cauldron presided over by the priestess (Rebeccah), one of them with bow and quiver (Esau) the other (Jacob) being initiated into the mysteries by the old leader of the fraternity (Isaac) who whispers the secret formula into his ear, blesses him and hands him – a piece of the kid to eat. The ceremony probably included a mock-slaughter and resurrection of the initiate, and this would account for the passage at the close of the chapter where Esau murderously pursues Jacob, Rebeccah directs affairs and the orgiastic ‘daughters of Heth’ in Cretan costume stand by. The two kids are probably an error: the same kid is shown twice, first being taken from its mother, and then being plunged into the cauldron of milk.

Nonnus, the Orphic writer, explains the shift in Crete from the goat to the bull-sacrifice by saying that Zagreus, or Dionysus, was a horned infant who occupied the throne of Zeus for a day. The Titans tore him in pieces and ate him after he had raced through his changes of shape: Zeus with the goatskin coat, Cronos making rain, an inspired youth, a lion, a horse, a horned snake, a tiger, a bull. It was as a bull that the Titans ate him. The Persian Mithras was also eaten in bull form.

There seems to have been a goat-cult in Ireland before the arrival of the Danaans and Milesians, for in a passage in the Book of the Dun Cow ‘goatheads’ are a sort of demon associated with leprechauns, pigmies, and the Fomorians, or African aborigines.1 But by the time of the Ulster hero Cuchulain, the traditional date of whose death is 2 AD, the royal bull-cult was well established. His destiny was bound up with that of a brown bull-calf, son of Queen Maeve’s famous Brown Bull. The Morrigan, the Fate-goddess, when she first met Cuchulain, warned him that only while the calf was still a yearling would he continue to live. The central episode in the Cuchulain saga is the War of the Bulls, fought between the armies of Maeve and her husband King Ailell as the result of an idle quarrel about two bulls. At the close of it, the Brown Bull, Cuchulain’s other self, kills his rival, the White-horned, which considering itself too noble to serve a woman, has deserted Maeve’s herd for the herd of Ailell; it then goes mad with pride, charges a rock and dashes out its brains. It is succeeded by its calf, and Cuchulain dies.

The bull-cult was also established in Wales at an early date. In a Welsh poetic dialogue contained in the Black Book of Carmarthen, Gwyddno Garanhir, Elphin’s father, describes the hero Gwyn as: ‘A bull of conflict, quick to disperse an embattled host’, and ‘bull of conflict’ here and in later poems seems to have been a sacred title rather than a complimentary metaphor; as ‘hawk’ and ‘eagle’ also were.

***

The War of the Bulls contains an instance of the intricate language of myth: the Brown Bull and the White-horned were really royal swine-herds who had the power of changing their shapes. It seems that in ancient times swine-herds had an altogether different standing from that conveyed in the parable of the Prodigal Son: to be a swine-herd was originally to be a priest in the service of the Death-goddess whose sacred beast was a pig.1 The War of the Bulls is introduced by the Proceedings of the Grand Bardic Academy, a seventh-century satire against the greed and arrogance of the ruling caste of bards, apparently composed by some member of an earlier oracular fraternity which had been dispossessed with the advent of Christianity. The leading character here is Marvan, royal swineherd to King Guaire of Connaught; he may be identified with Morvran (‘black raven’) son of the White Sow-goddess Cerridwen, who appears as Afagddu in the similar Welsh satire The Romance of Taliesin. In revenge for the loss of a magical white boar, at once his physician, music-maker and messenger, which the ruling bards have persuaded Guaire to slaughter, he routs them in a combat of wit and reduces them to silence and ignominy; Seanchan Torpest, the President of the Academy, addresses him as ‘Chief Prophet of Heaven and Earth’. There is a hint in the Romance of Branwen that the swine-herds of Matholwch King of Ireland were magicians, with a power of foreseeing the future. And this hint is expanded in Triad 56 which attributes to Coll ap Collfrewr, the magician, one of ‘the Three Powerful Swine-herds of the Isle of Britain’, the introduction into Britain of wheat and barley. But the credit was not really his. The name of the White Sow whom he tended at Dallwr in Cornwall and who went about Wales with gifts of grain, bees and her own young, was Hen Wen, ‘the Old White One’. Her gift to Maes Gwenith (‘Wheatfield’) in Gwent was three grains of wheat and three bees. She was, of course, the Goddess Cerridwen in beast disguise. (The story is contained in three series of Triads printed in the Myvyrian Archaiology.)

The unpleasant side of her nature was shown by her gift to the people of Arvon of a savage kitten, which grew up to be one of the Three Plagues of Anglesey, ‘the Palug Cat’. Cerridwen then is a Cat-goddess as well as a Sow-goddess. This links her with the Cat-as-corn-spirit mentioned by Sir James Frazer as surviving in harvest festivals in north and north-eastern Germany, and in most parts of France and with the monster Chapalu of French Arthurian legend.

There was also a Cat-cult in Ireland. A ‘Slender Black Cat reclining upon a chair of old silver’ had an oracular cave-shrine in Connaught at Clogh-magh-righ-cat, now Clough, before the coming of St. Patrick. This cat gave very vituperative answers to inquirers who tried to deceive her and was apparently an Irish equivalent of the Egyptian Cat-goddess Pasht. Egyptian cats were slender, black, long-legged and small-headed. Another seat of the Irish cat-cult was Knowth, a burial in Co. Meath of about the same date as New Grange. In The Proceedings of the Grand Bardic Academy the Knowth burial chamber is said to have been the home of the King-cat Irusan, who was as large as a plough-ox and once bore Seanchan Torpest, the chief-ollave of Ireland, away on its back in revenge for a satire. In his Poetic Astronomy, Hyginus identifies Pasht with the White Goddess by recording that when Typhon suddenly appeared in Greece – but whether he is referring to an invasion or to a volcanic eruption, such as destroyed most of the island of Thera, is not clear – the gods fled, disguised in bestial forms: ‘Mercury into an ibis, Apollo into a crane, a Thracian bird, Diana into a cat.’

The Old White Sow’s gift to the people of Rhiwgyverthwch was a wolf cub which also became famous. The Wolf-as-corn-spirit survives in roughly the same area as the Cat-as-corn-spirit; and in the island of Rügen the woman who binds the last sheaf is called ‘The Wolf’ and must bite the lady of the house and the stewardess, who placate her with a large piece of meat. So Cerridwen was a Wolf-goddess too, like Artemis. It looks as if she came to Britain between 2500–2000 BC with the New Stone Age long-headed agriculturists from North Africa.

Why the cat, pig, and wolf were considered particularly sacred to the Moon-goddess is not hard to discover. Wolves howl to the moon and feed on corpse-flesh, their eyes shine in the dark, and they haunt wooded mountains. Cats’ eyes similarly shine in the dark, they feed on mice (symbol of pestilence), mate openly and walk inaudibly, they are prolific but eat their own young, and their colours vary, like the moon, between white, reddish and black. Pigs also vary between white, reddish and black, feed on corpse-flesh, are prolific but eat their own young, and their tusks are crescent-shaped.

1 Sir Thomas Browne generously remarked in his Urn Burial that ‘what song the Sirens sang, or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women, though puzzling questions are not beyond all conjecture’. According to Suetonius the guesses made by various scholars whom the Emperor Tiberius consulted on this point were ‘Cercysera’ on account of the distaff (kerkis) that Achilles wielded; ‘Issa’, on account of his swiftness (aissoi, I dart); ‘Pyrrha’ on account of his red hair. Hyginus gives his vote for Pyrrha. My conjecture is that Achilles called himself Dacryoessa (‘the tearful one’) or, better, Drosoessa (‘the dewy one’), drosos being a poetic synonym for tears. According to Apollonius his original name Liguron (‘wailing’) was changed to Achilles by his tutor Cheiron. This is to suggest that the Achilles-cult came to Thessaly from Liguria. Homer punningly derives Achilles from achos (‘distress’), but Apollodorus from a ‘not’ and cheile ‘lips’, a derivation which Sir James Frazer calls absurd; though ‘Lipless’ is quite a likely name for an oracular hero.

1 I find that I have been anticipated in this explanation by Maimonides (‘Rambam’), the twelfth-century Spanish Jew who reformed the Judaic religion and was, incidentally, Saladin’s physician-royal. In his Guide to the Erring he reads the text as an injunction against taking part in Ashtaroth worship.

2 In the preface to my King Jesus I define iconotropy as a technique of deliberate misrepresentation by which ancient ritual icons are twisted in meaning in order to confirm a profound change of the existent religious system – usually a change from matriarchal to patriarchal – and the new meanings are embodied in myth. I adduce examples from the myths of Pasiphaë, Oedipus, and Lot.

1 Demons and bogeys are invariably the reduced gods or priests of a superseded religion: for example the Empusae and Lamiae of Greece who in Aristophanes’s day were regarded as emissaries of the Triple Goddess Hecate. The Lamiae, beautiful women who used to seduce, enervate and suck the blood of travellers, had been the orgiastic priestesses of the Libyan Sea-goddess Lamia; and the Empusae, demons with one leg of brass and one ass’s leg were relics of the Set cult – the Lilim, or Children of Lilith, the devotees of the Hebrew Owl-goddess, who was Adam’s first wife, were ass-haunched.

1 Evidence of a similar function in early Greece is the conventional epithet dios, ‘divine’ applied in the Odyssey to the swine-herd Eumaeus. Because of the horror in which swineherds were held by the Jews and Egyptians and the contempt in which, thanks to the Prodigal Son, they have long been held in Europe, the word is usually mistranslated ‘honest or worthy’ though admitted to be an hapax legomenon. It is true that except on one night of the year – the full moon that fell nearest to the winter solstice, when the pig was sacrificed to Isis and Osiris and its flesh eaten by every Egyptian – the taboo on any contact with pigs was so strong that swine-herds though full-blooded Egyptians (according to Herodotus) were avoided like the plague and forced to marry within their own caste; but this was a tribute to their sanctity rather than anything else. The public hangman is similarly avoided in France and England because he has courageously undertaken, in the interests of public morality, a peculiarly horrible and thankless trade.