THE BATTLE OF THE TREES

It seems that the Welsh minstrels, like the Irish poets, recited their traditional romances in prose, breaking into dramatic verse, with harp accompaniment, only at points of emotional stress. Some of these romances survive complete with the incidental verses; others have lost them; in some cases, such as the romance of Llywarch Hen, only the verses survive. The most famous Welsh collection is the Mabinogion, which is usually explained as ‘Juvenile Romances’, that is to say those that every apprentice to the minstrel profession was expected to know; it is contained in the thirteenth-century Red Book of Hergest. Almost all the incidental verses are lost. These romances are the stock-in-trade of a minstrel and some of them have been brought more up-to-date than others in their language and description of manners and morals.

The Red Book of Hergest also contains a jumble of fifty-eight poems, called The Book of Taliesin, among which occur the incidental verses of a Romance of Taliesin which is not included in the Mabinogion. However, the first part of the romance is preserved in a late sixteenth-century manuscript, called the ‘Peniardd M.S.’, first printed in the early nineteenth-century Myvyrian Archaiology, complete with many of the same incidental verses, though with textual variations. Lady Charlotte Guest translated this fragment, completing it with material from two other manuscripts, and included it in her well-known edition of the Mabinogion (1848). Unfortunately, one of the two manuscripts came from the library of Iolo Morganwg, a celebrated eighteenth-century ‘improver’ of Welsh documents, so that her version cannot be read with confidence, though it has not been proved that this particular manuscript was forged.

The gist of the romance is as follows. A nobleman of Penllyn named Tegid Voel had a wife named Caridwen, or Cerridwen, and two children, Creirwy, the most beautiful girl in the world, and Afagddu, the ugliest boy. They lived on an island in the middle of Lake Tegid. To compensate for Afagddu’s ugliness, Cerridwen decided to make him highly intelligent. So, according to a recipe contained in the books of Vergil of Toledo the magician (hero of a twelfth-century romance), she boiled up a cauldron of inspiration and knowledge, which had to be kept on the simmer for a year and a day. Season by season, she added to the brew magical herbs gathered in their correct planetary hours. While she gathered the herbs she put little Gwion, the son of Gwreang, of the parish of Llanfair in Caereinion, to stir the cauldron. Towards the end of the year three burning drops flew out and fell on little Gwion’s finger. He thrust it into his mouth and at once understood the nature and meaning of all things past, present and future, and thus saw the need of guarding against the wiles of Cerridwen who was determined on killing him as soon as his work should be completed. He fled away, and she pursued him like a black screaming hag. By use of the powers that he had drawn from the cauldron he changed himself into a hare; she changed herself into a greyhound. He plunged into a river and became a fish; she changed herself into an otter. He flew up into the air like a bird; she changed herself into a hawk. He became a grain of winnowed wheat on the floor of a barn; she changed herself into a black hen, scratched the wheat over with her feet, found him and swallowed him. When she returned to her own shape she found herself pregnant of Gwion and nine months later bore him as a child. She could not find it in her heart to kill him, because he was very beautiful, so tied him in a leather bag and threw him into the sea two days before May Day. He was carried into the weir of Gwyddno Garanhair near Dovey and Aberystwyth, in Cardigan Bay, and rescued from it by Prince Elphin, the son of Gwyddno and nephew of King Maelgwyn of Gwynedd (North Wales), who had come there to net fish. Elphin, though he caught no fish, considered himself well rewarded for his labour and renamed Gwion ‘Taliesin’, meaning either ‘fine value’, or ‘beautiful brow’ – a subject for punning by the author of the romance.

When Elphin was imprisoned by his royal uncle at Dyganwy (near Llandudno), the capital of Gwynedd, the child Taliesin went there to rescue him and by a display of wisdom, in which he confounded all the twenty-four court-bards of Maelgwyn – the eighth-century British historian Nennius mentions Maelgwyn’s sycophantic bards – and their leader the chief bard Heinin, secured the prince’s release. First he put a magic spell on the bards so that they could only play blerwm blerwm with their fingers on their lips like children, and then he recited a long riddling poem, the Hanes Taliesin, which they were unable to understand, and which will be found in Chapter V. Since the Peniardd version of the romance is not complete, it is just possible that the solution of the riddle was eventually given, as in the similar romances of Rumpelstiltskin, Tom Tit Tot, Oedipus, and Samson. But the other incidental poems suggest that Taliesin continued to ridicule the ignorance and stupidity of Heinin and the other bards to the end and never revealed his secret.

The climax of the story in Lady Charlotte’s version comes with another riddle, proposed by the child Taliesin, beginning:

Discover what it is:

The strong creature from before the Flood

Without flesh, without bone,

Without vein, without blood,

Without head, without feet…

In field, in forest…

Without hand, without foot.

It is also as wide

As the surface of the earth,

And it was not born,

Nor was it seen…

The solution, namely ‘The Wind’, is given practically with a violent storm of wind which frightens the King into fetching Elphin from the dungeon, whereupon Taliesin unchains him with an incantation. Probably in an earlier version the wind was released from the mantle of his comrade Afagddu or Morvran, as it was by Morvran’s Irish counterpart Marvan in the early mediaeval Proceedings of the Grand Bardic Academy, with which The Romance of Taliesin has much in common. ‘A part of it blew into the bosom of every bard present, so that they all rose to their feet.’ A condensed form of this riddle appears in the Flores of Bede, an author commended in one of the Book of Taliesin poems:

Dic mihi quae est illa res quae caelum, totamque terram replevit, silvas et sirculos confringit…omnia-que fundamenta concutit, sed nec oculis videri aut [sic] manibus tangi potest.

[Answer] Ventus.

There can be no mistake here. But since the Hanes Taliesin is not preceded by any formal Dychymig Dychymig (‘riddle me this riddle’) or Dechymic pwy yw (‘Discover what it is’)1 commentators excuse themselves from reading it as a riddle at all. Some consider it to be solemn-sounding nonsense, an early anticipation of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll, intended to raise a laugh; others consider that it has some sort of mystical sense connected with the Druidical doctrine of the transmigration of souls, but do not claim to be able to elucidate this.

Here I must apologize for my temerity in writing on a subject which is not really my own. I am not a Welshman, except an honorary one through eating the leek on St. David’s Day while serving with the Royal Welch Fusiliers and, though I have lived in Wales for some years, off and on, have no command even of modern Welsh; and I am not a mediaeval historian. But my profession is poetry, and I agree with the Welsh minstrels that the poet’s first enrichment is a knowledge and understanding of myths. One day while I was puzzling out the meaning of the ancient Welsh myth of Câd Goddeu (‘The Battle of the Trees’), fought between Arawn King of Annwm (‘The Bottomless Place’), and the two sons of Dôn, Gwydion and Amathaon, I had much the same experience as Gwion of Llanfair. A drop or two of the brew of Inspiration flew out of the cauldron and I suddenly felt confident that if I turned again to Gwion’s riddle, which I had not read since I was a schoolboy, I could make sense of it.

This Battle of the Trees was ‘occasioned by a Lapwing, a White Roebuck and a Whelp from Annwm.’ In the ancient Welsh Triads, which are a collection of sententious or historical observations arranged epigrammatically in threes, it is reckoned as one of the ‘Three Frivolous Battles of Britain’. And the Romance of Taliesin contains a long poem, or group of poems run together, called Câd Goddeu, the verses of which seem as nonsensical as the Hanes Taliesin because they have been deliberately ‘pied’. Here is the poem in D. W. Nash’s mid-Victorian translation, said to be unreliable but the best at present available. The original is written in short rhyming lines, the same rhyme often being sustained for ten or fifteen lines. Less than half of them belong to the poem which gives its name to the whole medley, and these must be laboriously sorted before their relevance to Gwion’s riddle can be explained. Patience!

CÂD GODDEU

(The Battle of the Trees)

I have been in many shapes,

Before I attained a congenial form.

I have been a narrow blade of a sword.

(I will believe it when it appears.)

5 have been a drop in the air.

I have been a shining star.

I have been a word in a book.

I have been a book originally.

I have been a light in a lantern.

10 A year and a half.

I have been a bridge for passing over

Three-score rivers.

I have journeyed as an eagle.

I have been a boat on the sea.

15 have been a director in battle.

I have been the string of a child’s swaddling clout.

I have been a shield in the fight.

I have been the string of a harp,

20 Enchanted for a year

In the foam of water.

I have been a poker in the fire.

I have been a tree in a covert.

There is nothing in which I have not been.

25 I have fought, though small,

In the Battle of Goddeu Brig,

Before the Ruler of Britain,

Abounding in fleets.

Indifferent bards pretend,

30 They pretend a monstrous beast,

With a hundred heads,

And a grievous combat

At the root of the tongue.

And another fight there is

35 At the back of the head.

A toad having on his thighs

A hundred claws,

A spotted crested snake,

For punishing in their flesh

40 A hundred souls on account of then sins.

I was in Caer Fefynedd,

Thither were hastening grasses and trees.

Wayfarers perceive them,

Warriors are astonished

45 At a renewal of the conflicts

Such as Gwydion made.

There is calling on Heaven,

And on Christ that he would effect

Their deliverance,

50 The all-powerful Lord.

If the Lord had answered,

Through charms and magic skill,

Assume the forms of the principal trees,

With you in array

55 Restrain the people

Inexperienced in battle.

When the trees were enchanted

There was hope for the trees,

That they should frustrate the intention

60 Of the surrounding fires….

And enjoying themselves in a circle,

And one of them relating

The story of the deluge,

65 And of the cross of Christ,

And of the Day of Judgement near at hand,

The alder-trees in the first line,

They made the commencement.

Willow and quicken tree,

70 They were slow in their array.

The plum is a tree

Not beloved of men;

The medlar of a like nature,

Overcoming severe toil.

75 The bean bearing in its shade

An army of phantoms.

The raspberry makes

Not the best of food.

In shelter live,

80 The privet and the woodbine,

And the ivy in its season.

Great is the gorse in battle.

The cherry-tree had been reproached.

The birch, though very magnanimous,

85 Was late in arraying himself;

It was not through cowardice,

But on account of his great size.

The appearance of the…

Is that of a foreigner and a savage.

90 The pine-tree in the court,

Strong in battle,

By me greatly exalted

In the presence of kings,

The elm-trees are his subjects.

95 He turns not aside the measure of a foot,

But strikes right in the middle,

And at the farthest end.

The hazel is the judge,

His berries are thy dowry.

100 The privet is blessed.

Strong chiefs in war

Are the…and the mulberry.

Prosperous the beech-tree.

The holly dark green,

Defended with spikes on every side,

Wounding the hands.

The long-enduring poplars

Very much broken in fight.

110 The plundered fern;

The brooms with their offspring:

The furze was not well behaved

Until he was tamed.

The heath was giving consolation,

115 Comforting the people.

The black cherry-tree was pursuing.

The oak-tree swiftly moving,

Before him tremble heaven and earth,

Stout doorkeeper against the foe

120 Is his name in all lands.

The corn-cockle bound together,

Was given to be burnt.

Others were rejected

On account of the holes made

125 By great violence

In the field of battle.

Very wrathful the…

Cruel the gloomy ash.

Bashful the chestnut-tree,

130 Retreating from happiness.

There shall be a black darkness,

There shall be a shaking of the mountain,

There shall be a purifying furnace,

There shall first be a great wave,

135 And when the shout shall be heard –

Putting forth new leaves are the tops of the beech,

Changing form and being renewed from a withered state;

Entangled are the tops of the oak.

From the Gorchan of Maelderw.

140 Smiling at the side of the rock

(Was) the pear-tree not of an ardent nature.

Neither of mother or father,

When I was made,

Was my blood or body;

145 Of nine kinds of faculties,

Of fruit of fruits,

Of fruit God made me,

Of the blossom of the mountain primrose,

150 Of earth of earthly kind.

When I was made

Of the blossoms of the nettle,

Of the mater of the ninth wave,

I was spell-bound by Math

155 Before I became immortal.

I was spell-bound by Gwydion,

Great enchanter of the Britons,

Of Eurys, of Eurwn,

Of Euron, of Medron,

160 In myriads of secrets,

I am as learned as Math….

I know about the Emperor

When he was half burnt.

I know the star-knowledge

165 Of stars before the earth (was made),

Whence I was born,

How many worlds there are.

It is the custom of accomplished bards

To recite the praise of their country.

170 have played in Lloughor,

I have slept in purple.

Was I not in the enclosure

With Dylan Ail Mor,

On a couch in the centre

175 Between the two knees of the prince

Upon two blunt spears?

When from heaven came

The torrents into the deep,

Rushing with violent impulse.

180 (I know) four-score songs,

For administering to their pleasure.

There is neither old nor young,

Except me as to their poems,

Any other singer who knows the whole of the nine hundred

185 Which are known to me,

Concerning the blood-spotted sword.

Honour is my guide.

Profitable learning is from the Lord.

(I know) of the slaying of the boar,

190 Its appearing, its disappearing,

Its knowledge of languages.

(I know) the light whose name is Splendour,

That scatter rays of fire

195 High above the deep.

I have been a spotted snake upon a hill;

I have been a viper in a lake;

I have been an evil star formerly.

I have been a weight in a mill. (?)

200 My cassock is red all over.

I prophesy no evil.

Four score puffs of smoke

To every one who will carry them away:

And a million of angels,

205 On the point of my knife.

Handsome is the yellow horse,

But a hundred times better

Is my cream-coloured one,

Swift as the sea-mew,

210 Which cannot pass me

Between the sea and the shore.

Am I not pre-eminent in the field of blood?

I have a hundred shares of the spoil.

My wreath is of red jewels,

215 Of gold is the border of my shield.

There has not been born one so good as I,

Or ever known,

Except Goronwy,

From the dales of Edrywy.

220 Long and white are my fingers,

It is long since I was a herdsman.

I travelled over the earth

Before I became a learned person.

I have travelled, I have made a circuit,

225 have slept in a hundred islands;

I have dwelt in a hundred cities.

Learned Druids,

Prophesy ye of Arthur?

Or is it me they celebrate,

230 And the Crucifixion of Christ,

And the Day of Judgement near at hand,

And one relating

The history of the Deluge?

With a golden jewel set in gold

235 I am enriched,

And I am indulged in pleasure

By the oppressive toil of the goldsmith.

With a little patience most of the lines that belong to the poem about the Battle of the Trees can be separated from the four or five other poems with which they are mixed. Here is a tentative restoration of the easier parts, with gaps left for the more difficult. The reasons that have led me to this solution will appear in due course as I discuss the meaning of the allusions contained in the poem. I use the balled metre as the most suitable English equivalent of the original.

THE BATTLE OF THE TREES

(lines 41–42)

From my seat at Fefynedd,

A city that is strong,

I matched the trees and green things

Hastening along.

(lines 43–46)

Wayfarers wondered,

Warriors were dismayed

At renewal of conflicts

Such as Gwydion made,

(lines 32–35)

Under the tongue-root

A fight most dread,

And another raging

Behind, in the head.

(lines 67–70

The alders in the front line

Began the affray,

Willow and rowan-tree

Were tardy in array.

(lines 104–107)

The holly, dark green,

Made a resolute stand;

He is armed with many spear-points,

Wounding the hand.

(lines 117–120)

With foot–beat of the swift oak

Heaven and earth rung;

‘Stout Guardian of the Door’

His name in every tongue.

(lines 82, 81, 98, 57)

Great was the gorse in battle,

And the ivy at his prime;

The hazel was arbiter

At this charmed time.

(lines 88, 89, 128, 95, 96)

Uncouth and savage was the [fir?]

Cruel the ash-tree –

Turns not aside a foot-breadth,

Straight at the heart runs he.

(lines 84–87)

The birch, though very noble,

Armed himself but late:

A sign not of cowardice

But of high estate.

(lines 114, 115, 108, 109)

The heath gave consolation

To the toil-spent folk,

The long-enduring poplars

In battle much broke.

(lines 123, 126)

Some of them were cast away

On the field of fight

Because of holes torn in them

By the enemy’s might.

(lines 127, 94, 92, 93)

Very wrathful was the [vine?]

Whose henchmen are the elms;

I exalt him mightily

To rulers of realms.

(lines 79, 80, 56, 90)

In shelter linger

Privet and woodbine

Inexperienced in warfare;

And the courtly pine.

Little Gwion has made it clear that he does not offer this encounter as the original Câd Goddeu but as:

A renewal of conflicts

Such as Gwydion made.

Commentators, confused by the pied verses, have for the most part been content to remark that in Celtic tradition the Druids were credited with the magical power of transforming trees into warriors and sending them into battle. But, as the Rev. Edward Davies, a brilliant but hopelessly erratic Welsh scholar of the early nineteenth century, first noted in his Celtic Researches (1809), the battle described by Gwion is not a frivolous battle, or a battle physically fought, but a battle fought intellectually in the heads and with the tongues of the learned. Davies also noted that in all Celtic languages trees means letters; that the Druidic colleges were founded in woods or groves; that a great part of the Druidic mysteries was concerned with twigs of different sorts; and that the most ancient Irish alphabet, the Beth-Luis-Nion (‘Birch-Rowan-Ash’) takes its name from the first three of a series of trees whose initials form the sequence of its letters. Davies was on the right track and though he soon went astray because, not realizing that the poems were pied, he mistranslated them into what he thought was good sense, his observations help us to restore the text of the passage referring to the hastening green things and trees:

(lines 130 and 53)

Retreating from happiness,

They would fain be set

In forms of the chief letters

Of the alphabet.

The following lines seem to form an introduction to his account of the battle:

(lines 136–137)

The tops of the beech-tree

Have sprouted of late,

Are changed and renewed

From their withered state.

(lines 103, 52, 138, 58)

When the beech prospers,

Though spells and litanies

The oak–tops entangle,

There is hope for trees.

This means, if anything, that there had been a recent revival of letters in Wales. ‘Beech’ is a common synonym for ‘literature’. The English word ‘book’, for example, comes from a Gothic word meaning letters and, like the German buchstabe, is etymologically connected with the word ‘beech’ – the reason being that writing tablets were made of beech. As Venantius Fortunatus, the sixth-century bishop-poet, wrote: Barbara fraxineis pingatur runa tabellis – ‘Let the barbarian rune be marked on beechwood tablets.’ The ‘tangled oak-tops’ must refer to the ancient poetic mysteries: as has already been mentioned, the derwydd, or Druid, or poet, was an ‘oak-seer’. An early Cornish poem describes how the Druid Merddin, or Merlin, went early in the morning with his black dog to seek the glain, or magical snake’s-egg (probably a fossiled sea-urchin of the sort found in Iron Age burials), cull cresses and samolus (herbe d’or), and cut the highest twig from the top of the oak. Gwion, who in line 225 addresses his fellow-poets as Druids, is saying here: ‘The ancient poetic mysteries have been reduced to a tangle by the Church’s prolonged hostility, but they have a hopeful future, now that literature is prospering outside the monasteries.’

He mentions other participants in the battle:

Strong chiefs in war

Are the [ ? ] and mulberry….

The raspberry that makes

Not the best of foods….

The plum is a tree

Unbeloved of men….

The medlar of like nature….

None of these mentions makes good poetic sense. Raspberry is excellent food; the plum is a popular tree; pear-wood is so ardent that in the Balkans it is often used as a substitute for cornel to kindle the ritual need-fire; the mulberry is not used as a weapon-tree; the cherry was never slighted and in Gwion’s day was connected with the Nativity story in a popular version of the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew; and the black cherry does not ‘pursue’. It is pretty clear that these eight names of orchard fruits, and another which occupied the place that I have filled with ‘fir’, have been mischievously robbed from the next riddling passage in the poem:

Of nine kinds of faculties,

Of fruit of fruits,

Of fruit God made me….

and have been substituted for the names of nine forest trees that did engage in the fight.

It is hard to decide whether the story of the fruit man belongs to the Battle of the Trees poem, or whether it is a ‘Here come I’ speech like the four others muddled up in the Câd Goddeu, of whom the speakers are evidently Taliesin, the Flower-Goddess Blodeuwedd, Hu Gadarn the ancestor of the Cymry, and the God Apollo. On the whole, I think it does belong to the Battle of the Trees:

(lines 145–147)

With nine sorts of faculty

God has gifted me:

I am fruit of fruits gathered

From nine sorts of tree –

(lines 71, 73, 77, 83, 102, 116, 141)

Plum, quince, whortle, mulberry,

Raspberry, pear,

Black cherry and white

With the sorb in me share.

By a study of the trees of the Irish Beth-Luis-Nion tree-alphabet, with which the author of the poem was clearly familiar, it is easy to restore the original nine trees which have been replaced with the fruit names. We can be sure that it is the sloe that ‘makes not the best of foods’; the elder, a notoriously bad wood for fuel and a famous country remedy for fevers, scalds and burns, that is ‘not ardent’; the unlucky whitethorn, and the blackthorn ‘of like nature’, that are ‘unbeloved of men’ and, with the archer’s yew, are the ‘strong chiefs in war’. And on the analogy of the oak from which reverberating clubs were made, the yew from which deadly bows and dagger-handles were made, the ash from which sure-thrusting spears were made, and the poplar from which long-enduring shields were made, I suggest that the original of ‘the black cherry was pursuing’ was the restless reed from which swift-flying arrow-shafts were made. The reed was reckoned a ‘tree’ by the Irish poets.

The ‘I’ who was slighted because he was not big is Gwion himself, whom Heinin and his fellow-bards scoffed at for his childish appearance; but he is perhaps speaking in the character of still another tree – the mistletoe, which in the Norse legend killed Balder the sun-god after having been slighted as too young to take the oath not to harm him. Although in ancient Irish religion there is no trace of a mistletoe cult, and the mistletoe does not figure in the Beth-Luis-Nion, to the Gallic Druids who relied on Britain for their doctrine it was the most important of all trees, and remains of mistletoe have been found in conjunction with oak-branches in a Bronze Age tree-coffin burial at Gristhorpe near Scarborough in Yorkshire. Gwion may therefore be relying here on a British tradition of the original Câd Goddeu rather than on his Irish learning.

The remaining tree-references in the poem are these:

The broom with its children…

The furze not well behaved

Until he was tamed….

Bashful the chestnut-tree….

The furze is tamed by the Spring-fires which make its young shoots edible for sheep.

The bashful chestnut does not belong to the same category of letter trees as those that took part in the battle; probably the line in which it occurs is part of another of the poems included in Câd Goddeu, which describes how the lovely Blodeuwedd (‘Flower-aspect’) was conjured by the wizard Gwydion, from buds and blossoms. The poem is not difficult to separate from the rest of Câd Goddeu, though one or two lines seem to be missing. They can be supplied from the parallel lines:

Of nine kinds of faculties.

Of fruit of fruits,

Of fruit God made me.

The fruit man is created from nine kinds of fruit; the flower woman must have been created from nine kinds of flower. Five are given in Câd Goddeu; three more – broom, meadow-sweet and oak-blossom – in the account of the same event in the Romance of Math the Son of Mathonwy; and the ninth is likely to have been the hawthorn, because Blodeuwedd is another name for Olwen, the May-queen, daughter (according to the Romance of Kilhwych and Olwen) of the Hawthorn, or Whitethorn, or May Tree; but it may have been the white-flowering trefoil.

HANES BLODEUWEDD

line 142

Not of father nor of mother

144

Was my blood, was my body.

156

I was spellbound by Gwydion,

157

Prime enchanter of the Britons,

143

When he formed me from nine blossoms,

149

Nine buds of various kind:

148

From primrose of the mountain,

121

Broom, meadow-sweet and cockle,

Together intertwined,

75

From the bean in its shade bearing

76

A white spectral army

150

Of earth, of earthly kind,

152

From blossoms of the nettle,

129

Oak, thorn, and bashful chestnut –

[146

Nine powers of nine flowers,

145]

Nine powers in me combined,

149

Nine buds of plant and tree.

220

Long and white are my fingers

153

As the ninth wave of the sea.

In Wales and Ireland primroses are reckoned fairy flowers and in English folk tradition represent wantonness (cf. ‘the primrose path of dalliance’ – Hamlet; the ‘primrose of her wantonness’ – Brathwait’s Golden Fleece). So Milton’s ‘yellow-skirted fayes’ wore primrose. ‘Cockles’ are the ‘tares’ of the Parable that the Devil sowed in the wheat; and the bean is traditionally associated with ghosts – the Greek and Roman homoeopathic remedy against ghosts was to spit beans at them – and Pliny in his Natural History records the belief that the souls of the dead reside in beans. According to the Scottish poet Montgomerie (1605), witches rode on bean-stalks to their sabbaths.

To return to the Battle of the Trees. Though the fern was reckoned a ‘tree’ by the Irish poets, the ‘plundered fern’ is probably a reference to fern-seed which makes invisible and confers other magical powers. The twice-repeated ‘privet’ is suspicious. The privet figures unimportantly in Irish poetic tree-lore; it is never regarded as ‘blessed’. Probably its second occurrence in line 100 is a disguise of the wild-apple, which is the tree most likely to smile from beside the rock, emblem of security: for Olwen, the laughing Aphrodite of Welsh legend, is always connected with the wild-apple. In line 99 ‘his berries are thy dowry’ is absurdly juxtaposed to the hazel. Only two fruit-trees could be said to dower a bride in Gwion’s day: the churchyard yew whose berries fell at the church porch where marriages were always celebrated, and the churchyard rowan, often substituted for the yew in Wales. I think the yew is here intended; yew-berries were prized for their sticky sweetness. In the tenth-century Irish poem, King and Hermit, Marvan the brother of King Guare of Connaught commends them highly as food.

The remaining stanzas of the poem may now be tentatively restored:

(lines 110, 160, and 161)

I have plundered the fern,

Through all secrets I spy,

Old Math ap Mathonwy

Knew no more than I.

(lines 101, 71–73, 77 and 78)

Strong chieftains were the blackthorn

With his ill fruit,

The unbeloved whitethorn

Who wears the same suit.

(lines 116, 111–113)

The swift-pursuing reed,

The broom with his brood,

And the furze but ill-behaved

Until he is subdued.

(lines 97, 99, 128, 141, 60)

The dower-scattering yew

Stood glum at the fight’s fringe,

With the elder slow to burn

Amid fires that singe,

(lines 100, 139 and 140)

And the blessed wild apple

Laughing for pride

From the Gorchan of Maelderw,

By the rock side.

(lines 83, 54, 25, 26)

But I, although slighted

Because I was not big,

Fought, trees, in your array

On the field of Goddeu Brig.

The broom may not seem a warlike tree, but in Gratius’s Genistae Altinates the tall white broom is said to have been much used in ancient times for the staves of spears and darts: these are probably the ‘brood’. Goddeu Brig means Tree-tops, which has puzzled critics who hold that Câd Goddeu was a battle fought in Goddeu, ‘Trees’, the Welsh name for Shropshire. The Gorchan of Maelderw (‘the incantation of Maelderw’) was a long poem attributed to the sixth-century poet Taliesin, who is said to have particularly prescribed it as a classic to his bardic colleagues. The apple-tree was a symbol of poetic immortality, which is why it is here presented as growing out of this incantation of Taliesin’s.

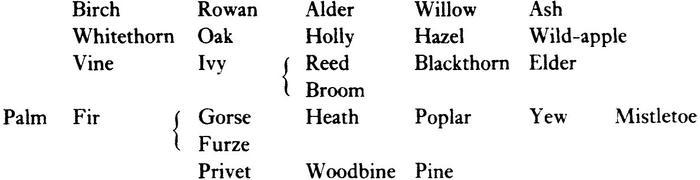

Here, to anticipate my argument by several chapters, is the Order of Battle in the Câd Goddeu:

It should be added that in the original, between the lines numbered 60 and 61, occur eight lines unintelligible to D. W. Nash: beginning with ‘the chieftains are falling’ and ending with ‘blood of men up to the buttocks’. They may or may not belong to the Battle of the Trees.

I leave the other pieces included in this medley to be sorted out by someone else. Besides the monologues of Blodeuwedd, Hu Gadarn and Apollo, there is a satire on monkish theologians, who sit in a circle gloomily enjoying themselves with prophecies of the imminent Day of Judgement (lines 62–66), the black darkness, the shaking of the mountain, the purifying furnace (lines 131–134), damning men’s souls by the hundred (lines 39–40) and pondering the absurd problems of the Schoolmen:

(lines 204, 205)

Room for a million angels

On my knife-point, it appears.

(lines 167 and 176)

Then room for how many worlds

A-top of two blunt spears?

This introduces a boast of Gwion’s own learning:

(lines 201,200)

But I prophesy no evil,

My cassock is wholly red.

(line 184)

‘He knows the Nine Hundred Tales’ –

Of whom but me is it said?

Red was the most honourable colour for dress among the ancient Welsh, according to the twelfth-century poet Cynddelw; Gwion is contrasting it with the dismal dress of the monks. Of the Nine Hundred Tales he mentions only two, both of which are included in the Red Book of Hergest: the Hunting of the Twrch Trwyth (line 189) and the Dream of Maxen Wledig (lines 162–3).

Lines 206 to 211 belong, it seems, to Can y Meirch, ‘The Song of the Horses’, another of the Gwion poems, which refers to a race between the horses of Elphin and Maelgwyn which is an incident in the Romance.

One most interesting sequence can be built up from lines 29–32, 36–37 and 234–237:

Indifferent bards pretend,

They pretend a monstrous beast,

With a hundred heads,

A spotted crested snake,

A toad having on his thighs

A hundred claws,

With a golden jewel set in gold

I am enriched;

And indulged in pleasure

By the oppressive toil of the goldsmith.

Since Gwion identifies himself with these bards, they are, I think, described as ‘indifferent’ by way of irony. The hundred-headed serpent watching over the jewelled Garden of the Hesperides, and the hundred-clawed toad wearing a precious jewel in his head (mentioned by Shakespeare’s Duke Senior) both belonged to the ancient toadstool mysteries, of which Gwion seems to have been an adept. The European mysteries are less fully explored than their Mexican counterpart; but Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Wasson and Professor Roger Heim have shown that the pre-Columbian Toadstool-god Tlalóc, represented as a toad with a serpent head-dress, has for thousands of years presided at the communal eating of the hallucigenic toadstool psilocybe: a feast that gives visions of transcendental beauty. Tlalóc’s European counterpart, Dionysus, shares too many of his mythical attributes for coincidence: they must be versions of the same deity; though at what period the cultural contact took place between the Old World and the New is debatable.

In my foreword to a revised edition of The Greek Myths, I suggest that a secret Dionysiac mushroom cult was borrowed from the native Pelasgians by the Achaeans of Argos. Dionysus’s Centaurs, Satyrs and Maenads, it seems, ritually ate a spotted toadstool called ‘fly-cap’ (amanita muscaria), which gave them enormous muscular strength, erotic power, delirious visions, and the gift of prophecy. Partakers in the Eleusinian, Orphic and other mysteries may also have known the panaeolus papilionaceus, a small dung-mushroom still used by Portuguese witches, and similar in effect to mescalin. In lines 234–237, Gwion implies that a single gem can enlarge itself under the influence of ‘the toad’ or ‘the serpent’ into a whole treasury of jewels. His claim to be as learned as Math and to know myriads of secrets may also belong to the toad-serpent sequence; at any rate, psilocybe gives a sense of universal illumination, as I can attest from my own experience of it. ‘The light whose name is Splendour’ may refer to this brilliance of vision, rather than to the Sun.

The Book of Taliesin contains several similar medleys or poems awaiting resurrection: a most interesting task, but one that must wait until the texts are established and properly translated. The work that I have done here is not offered as in any sense final.

CÂD GODDEU

‘The Battle of the Trees’.

The tops of the beech tree

Have sprouted of late,

Are changed and renewed

From their withered state.

When the beech prospers,

Though spells and litanies

The oak tops entangle,

There is hope for trees.

I have plundered the fern,

Through all secrets I spy,

Old Math ap Mathonwy

Knew no more than I.

For with nine sorts of faculty

God has gifted me:

I am fruit of fruits gathered

From nine sorts of tree –

Plum, quince, whortle, mulberry,

Raspberry, pear,

Black cherry and white

With the sorb in me share.

From my seat at Fefynedd,

A city that is strong,

I watched the trees and green things

Hastening along.

Retreating from happiness

They would fain be set

Informs of the chief letters

Of the alphabet.

Under the tongue root

A fight most dread,

And another raging

Behind, in the head.

The alders in the front line

Began the affray.

Willow and rowan-tree

Were tardy in array.

The holly, dark green,

Made a resolute stand;

He is armed with many spear-points

Wounding the hand.

With foot-beat of the swift oak

Heaven and earth rung;

‘Stout Guardian of the Door’,

His name in every tongue.

Great was the gorse in battle,

And the ivy at his prime;

The hazel was arbiter

At this charmed time.

Uncouth and savage was the fir,

Cruel the ash tree –

Turns not aside a foot-breadth,

Straight at the heart runs he.

The birch, though very noble,

Armed himself but late:

A sign not of cowardice

But of high estate.

The heath gave consolation

To the toil-spent folk,

The long-enduring poplars

In battle much broke.

Some of them were cast away

On the field of fight

Because of holes torn in them

By the enemy’s might.

Strong chieftains were the blackthorn

With his ill fruit,

The unbeloved whitethorn

Who wears the same suit,

The swift-pursuing reed,

The broom with his brood,

And the furze but ill-behaved

Until he is subdued.

The dower-scattering yew

Stood glum at the fight’s fringe

With the elder slow to burn

Amid fires that singe,

And the blessed wild apple

Laughing in pride

From the Gorchan of Maelderw,

By the rock side.

In shelter linger

Privet and woodbine,

Inexperienced in warfare,

And the courtly pine.

But I, although slighted

Because I was not big,

Fought, trees, in your array

On the field of Goddeu Brig.

1 Another form is dychymig dameg (‘a riddle, a riddle’), which seems to explain the mysterious ducdame ducdame in As You Like It, which Jacques describes as ‘a Greek invocation to call fools into a circle’ – perhaps a favourite joke of Shakespeare’s Welsh schoolmaster, remembered for its oddity.