In the days that followed this conversation with Bono, I began to look about me with new eyes — that is to say, with eyes from which the scales had new-fallen, where bedazzlement was harsh and all about me; and I saw for the first time and understood that in our house and the houses we visited, there were black and white, bonded, freed, free-born, indentured, enslaved, and hired.

Perhaps I may be pardoned my naïveté; I was but eight, and had given little thought to service and recompense.

Knowing, now, that my mother and I had been purchased, I began to revolve the question, For what purpose?

And though the solution to this mystery was, to my young mind, occulted, yet did I know where it lay: behind the forbidden door. Thither — in spite of my fears — would I have to repair for answers.

No words can tell the agitation of my spirits occasioned by merely the thought of throwing open that portal and beholding the secrets of the gloomy closet within. Consider that on the door itself was pasted my visage, open-mouthed, above crossed bones. I fancied that, should I be discovered, I should be caged and tortured like the animals in the experimental chambers, burning compounds applied to my skin, incisions made near my eyes.

When I would pass the door in the morning, I would hesitate before it and regard its latch and its lock. I considered furtively when I might find occasion to slip into the room without detection. 03-01 and some of the other academicians repaired there with some frequency, and it was of utmost importance that they not discover me dabbling in their mysteries.

I found my opportunity one night when I knew them to be holding a dinner and entertainment for other wealthy men of the colony who protested Britain’s yoke; that evening Mr. 03-01 and his brethren were to open their doors to a large company of prosperous merchants, doctors, lawyers, smugglers of Dutch tea and Madeira wine, owners of slave-ships, speculators in real estate, and colonial gentry who wished to give voice to their outrage and resist, as they said, the oppression of royal ministers and the bondage imposed upon them by Parliament. Well did I know that I would spend my evening in bed, from whence I could slip out, once they had begun their discussion in earnest and all ears were fixed upon the transports of incendiary disputation.

The chambers set aside for experiment were not lit at that hour. Though there were blankets over the cages, I could hear the animals stir as I passed by them, the floor creaking beneath my bare and chilled feet.

I stopped to watch the antics of the squirrels. They observed me in return. Their eyes were black as obsidian in the night. They stood upon their haunches.

“Play,” I whispered, but they would not; their attentions were absorbed in my endeavor, as if they knew what was to come, and wished particularly to witness it.

I passed by them to the forbidden door. Over the lintel was affixed the ancient dragon’s skull, its browning sockets gazing down the corridor.

On the door itself was the sketch of my own face.

I regarded it with that giddiness that comes of sin. I raised my hand and touched the metal latch, pressed it with my thumb, and found it, as I had suspected, locked; all the while hearing voices two rooms away which complained that Parliament would reduce honest men of business to the status of slaves.

In the days previous, I had observed the key used to open the door. It was a simple thing with but one tang. It was a matter of moments, then, for me to bend a wire so that I might motivate the tumblers of the lock and spring it open.

I lifted the elbow of the lock from the door’s hasp. Face to face with the cartoon of my own infant anxiety, I lifted the latch, and opened the door, and beheld the secret chamber.

Perhaps I had expected masks and robes and all the imagined gimcrackery of cultism: bibs of animal teeth, screws for boring into the head, phials and plungers to extract and titrate the soul; perhaps, merely, I had wished for these things, knowing too well what I would find instead.

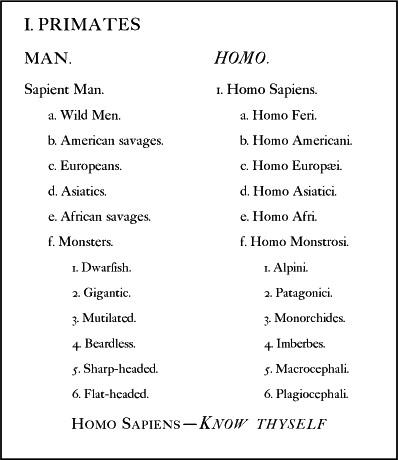

It was a small room, taken up mostly with a wide plank desk and three stools. On bookshelves were bound volumes with my name and my mother’s embossed upon the spine beside a date; the dates stretching back to the time of my birth. Upon the wall, writ large, was a chart labeled “MAMMALIA — or, Beasts that Give Suck.” And first upon it:

Below that, the primates continued in their course, each one named — the ape and the orangutan, the monkey — and then, the brutes, the feræ, the glires, all the beasts from sloth to pigmy shrew, arrayed silently in ordered cavalcade as if waiting admission to the Ark.

There was nothing, thus far, to affright. I had just leaned over to examine a print hung upon the wall, the figure of a woman unclothed, when I heard my name called. The painter, 07-03, was calling to the company, “He is not above-stairs!”

There was a cry of, “Music! We must have music!”

I ascertained that they wished me to perform, and it behove me to comply, that I might avoid detection. I backed out of the room, and had almost shut the door when my eyes fell again upon the engraving of the naked woman on the wall; and I saw that it was my mother.

“Octavian!” called 03-01. “Octavian? Your presence is cordially requested in the audience room! We have your violin!”

I stepped back into the forbidden chamber. I pulled the door shut behind me, and held my candle toward the print, viewing now more clearly than before her face, still and impassive, the close-cropped hair I rarely saw except concealed by wig or cap. I thought it strange that they should have a portrait of her here, especially in such a state of dishabille. Her portrait was entitled, “PLATE XVII. PUBESCENT FEMALE OF THE OYO COUNTRY IN AFRICA.” I squinted, and edged my gaze down to her breasts, her stomach, the lines that marked her; which extended out from her prone form to letters worn like mechanical bouquets in the blank space where her image floated. She hung there corpse-like; her hands turned outwards, as, in paintings of Christ, he stands when with gentility he reveals to Thomas the holes torn in his side and palms.

“A puff of breath would have extinguished your candle,” 03-01 chided, standing in the door — which now was wide open — behind me. I turned. He said, “A mere whisper across the flame. There could be no strategy simpler to pursue, nor so effective in delaying the punishment which is, as you are aware, contingent on your passing through this door.”

I could not speak for awe of him.

He leaned back and shouted to the others, “I have found him! Proceed without us!” He stepped back into the chamber and shut the door behind him. “Set the candle down upon the desk,” he said. “Sit upon a stool.”

He sat beside me. He smiled faintly and watched my face. He said, “You have seen your mother.” I did not reply. He offered, “In the illustration.”

I could not look at him anymore. My spirits were so disarranged, my nerves so clamorous in their confusion, that no course of thought, speech, or action presented itself.

His breeches were satin. It was a fancy evening.

He sighed, and offered nothing. The candle guttered between us. From a far chamber, I could hear the conversation of vital men, men on whom depended the colony’s well-being.

At length, he demanded, “Why have you trespassed here?”

“I wished . . . to know . . .”

“You know,” he said, nodding. “You have already divined our purpose.” He smiled. “In these volumes are recorded each bit of data that we have collected in the years since your mother came to live with us. Your height . . . your weight . . . your diseases . . . your sustenance both in its ingress and egress. Through the collection of such details, we hope to establish, in the broadest sense, the means by which children grow, the astounding systems of ingestion, decoction, and waste, the development of skills and the reception of ideas and language by the infant brain.”

The embossed names on the volumes glowed faintly in the candlelight, the mother, the son, twinned in each passing month, and I thought of those months — playing at her knees; or her telling me tales of the Governor’s wife and lap-dog, the barking, the stains, the hullabaloo of servants; I considered the nights of my childhood when she sat by my side and stared down upon me; and I recalled that earliest image, standing with her while men burned bubbles in the orchard like the ignition of cherubim. Such scenes as these, I had no doubt, were not extant in the volumes there, slipped between the quantification of my appetites; thus, I might read of the weight of peach cobbler I had eaten on a certain night when I was five, but not recall the blush of evening as I walked with her a half an hour later among the garden herbs.

I did not speak; instead, I meditated on the passage of time, and how it may be found in both a dry and a wet or gaseous state; how, though lush, it might be desiccated for storage.

“So you understand the experiment, then,” said 03-01.

I grasped the edges of my stool. 03-01 had crossed his legs.

“That is not all, sir,” I said.

“No,” said 03-01. “That . . . is not all.”

“Would you tell me, sir?”

“You know, Octavian.”

I shook my head.

Mr. 03-01 frowned. “What did you revolve in your thoughts, during the long silence?”

“I was thinking of time, sir.”

“I do not follow.”

“How time has different states, like unto the elements.”

“This is novel,” said 03-01.

“And how it is become dried.”

“You are a clever boy, though somewhat too obscure.”

“Sir, you have not answered my question.”

“Regarding?”

“Your work, sir,” I said, “with me.”

“True, I have not. You know what I shall say.”

“Still, I am . . .” I spake no more.

He asked, “What would you know?”

“Why are we called by names, when all others have numbers?”

“For the reason that you are the experiment, and all the rest of this . . . the house, the guests, the servants . . . all are in service of that pursuit of truth. You are central to the work; we, but the disembodied observers of your progress.”

“What do you propose to do with me?”

“You know the answer.”

“Tell me, please, sir,” I said.

He gave me a canny look, and explained slowly, “We are providing you with an education equal to any of the princes of Europe . . . We wish to divine whether you are a separate and distinct species. Thus, we wish to determine your capacity, as an African prince, for the acquisition of the noble arts and sciences.”

“You wish to prove that I am the equal of any other?”

“We wish to prove nothing,” said 03-01. “We simply aim at discovering the truth.” He rose from his stool.

“Sir —”

“Stand,” he said; which I did. “Put out your arms at your sides, straight,” said he; which I did.

“Sir —,” I said, “you shall be glad of my success?”

He smiled. “Of course I shall,” he said. “You are a good boy.”

I asked, “Shall I someday be called by a number?”

He looked fondly upon me. He said, “That, Octavian, is something to aspire to.” He turned away from me, and began perusing the volumes upon the shelf, selecting some, drawing them out, and laying them in the crook of his arm.

I waited, my arms outstretched at either side, until he turned again, and began to stack them, volume after volume, on my hands.

“When I was a boy,” said he, “this was my punishment. Standing with Milton weighing upon one hand and Shakespeare the other. But you . . . you shall be encumbered with your own past, hm?”

My hands bobbed beneath the weight.

“Drop one,” he said, “and you shall be caned.” He stepped out into the experimental chamber and shouted for Bono.

Turning back to me, he said, “Here, my boy, was the miraculous aspect of this little torture, as I found. When twenty minutes had passed, and I was permitted to set down the volumes, or they were taken from my hands — when I was relieved of the weight of the books — I marked that as I dropped my empty arms, they rose again of their own accord. . . . They drifted upwards. They felt as light as air. I could not keep them down. ’Twas an ecstatic sensation. . . . My arms yearned for the stance of punishment; and when they lifted thus, I could have been flying. This, you must understand, Octavian, is the true and sublime end of discipline: that you may rise into a new and glorious buoyancy.”