Shadow Grounds

THREE days of clear weather have come to an end. I know it as soon as I awaken. I open my eyes with no discomfort.

The sun is stripped of light and warmth, the sky is cloaked in heavy clouds. Trees send up crooked, leafless branches into the chill gray, like cracks in the firmament. Surely snow will fall through, yet the air is still.

"It will not snow today," the Colonel informs me. "Such clouds do not bring snow."

I open the window to look out, but cannot know what the Colonel understands.

The Gatekeeper sits before his iron stove, shoes removed, warming his feet. The stove is like the one in the Library. It has a flat heating surface for a kettle and a drawer at the bottom for the ash. The front opens with a large metal pull, which the Gatekeeper uses as his footrest. The Gatehouse is stuffy from kettle steam and cheap pipe tobacco, or more probably some surrogate. The Gatekeeper's feet also smell.

"I need a scarf," I begin. "I get chills in my head."

"I can see that," snorts the Gatekeeper. "Does not surprise me at all."

"There are old clothes in the Collection Room at the back of the Library. I was wondering if I might borrow a few."

"Oh, those things," says the Gatekeeper. "You can help yourself to any of them. Take a muffler, take a coat, take whatever you like."

"And the owners?"

"Forget about the owners Even if the owners are around, they have forgotten about those things. But say, I heard you were looking for a musical instrument?"

He knows everything.

"Officially, the Town has no musical instruments," he says. "But that does not rule out the possibility. You do serious work, so what could be wrong if you had yourself an instrument. Go to the Power Station and ask the Caretaker. He might find you something."

"Power Station?" I ask, surprised.

"We use power, you know," he says, pointing to the light overhead. "You think power grows on apple trees?" The Gatekeeper laughs as he draws a map. "You take the road along the south bank of the River, going upstream. Then after thirty minutes, you see an old granary on your right-hand side. The shed with the roof caved in and no door. You make a right turn there, and follow the road until you see a hill. Beyond the hill is the Woods. Go five hundred yards into the Woods, and there is the Power Station. Understand?"

"I believe so," I say. "But it is dangerous to go into the Woods in winter. Everyone tells me so. I fell ill the last time."

"Ah, yes, I nearly forgot. I had to carry you up the Hill," says the Gatekeeper. "Are you better now?"

"Much better, thank you."

"A little less foolish?"

"Yes, I hope so."

The Gatekeeper grins broadly and shifts his feet on the stove handle. "You got to know your limits. Once is enough, but you got to learn. A little caution never hurt anyone. A good woodsman has only one scar on him. No more, no less. You get my meaning?"

I nod appropriately.

"No need to worry about the Power Station. It sits right at the entrance to the Woods. Only one path, you cannot get lost. No Woodsfolk around there. The real danger is deep in the Woods, and near the Wall. If you stay away from them, everything will be fine. Keep to the path, do not go past the Power Station."

"Is the Caretaker one of the Woodsfolk?"

"Not him. Not Woodsfolk and not Townfolk. We call him nobody. He stays at the edge of the Woods, never comes to Town. Harmless, got no guts."

"What are Woodsfolk like?"

The Gatekeeper turns his head and pauses before saying, "Like I believe I told you the very first time, you can ask whatever questions you please, but I can answer or not answer as I see fit."

I open my mouth, a question on my lips.

"Forget it. Today, no answers," says the Gatekeeper. "But say, you wanted to see your shadow? Time you saw it, no? The shadow is down in strength since winter come along. No reason for you not to see it."

"Is he sick?"

"No, not sick. Healthy as can be. It has a couple of hours exercise every day. Healthy appetite, ha ha. Just that when winter days get short and cold, any shadow is bound to lose a little something. No fault of mine. Just the way things go. Well, let it speak for itself."

The Gatekeeper retrieves a ring of keys from the wall and puts them in his pocket. He yawns as he laces up his leather boots. They look heavy and sturdy, with iron cleats for walking in snow.

My shadow lives between the Town and the outside. As I cannot leave to go to the world beyond the Wall, my shadow cannot come into Town. So the one place we can meet is the Shadow Grounds, a close behind the Gatehouse. It is small and fenced in.

The Gatekeeper takes the keys out of his pocket and opens the iron gate to the enclosure.

We enter the Shadow Grounds. It is a perfect square, one side backed up almost against the Wall. In the center is an <id elm tree, underneath which is a bench. The tree is blanched with age; I do not know if it is alive or dead.

In a corner stands a lean-to of bricks and building scraps. No glass in the window; only a rude wooden panel that swings up for a door. I see no chimney, so there must be no heat.

"That is where your shadow sleeps," says the Gatekeeper. "Not as bad as it looks. Even got water and a toilet. Not quite a hotel, but it is shelter. Care to go in?"

"No, I'll meet him here," I say, still dizzy from the stale air in the Gatehouse. Cold or not, it is better to be out in the fresh air.

"Fine by me, let me bring it outside." The Gatekeeper storms into the lean-to by himself.

I turn up my collar and sit down on the bench, scraping at the ground with the heel of my shoe. The ground is hard, with lingering patches of snow where shaded by the Wall.

Presently, the Gatekeeper emerges and strides across the Grounds, my shadow following slowly after. My shadow is not the picture of health the Gatekeeper has led me to believe.

His face is haggard, all eyes and beard.

"I imagine you two want to be alone, ha ha," says the Gatekeeper. "Probably got heaps to talk about. Well, have yourselves a nice, long talk. But not too long, if you know what I mean."

I know what he means. My shadow and I watch the Gatekeeper lock the enclosure gate and withdraw to the Gatehouse. His cleats rasp into the frozen distance. We hear the heavy wooden door shutting behind him. Not until he is gone from sight does the shadow approach and sit next to me. He wears a bulky rough-knit sweater, work pants, and the boots I got for him.

"How are you holding up?" I ask.

"How do you expect?" says my shadow. "It's freezing and the food's terrible."

"But he said you exercise every day."

"Exercise?" says my shadow. "Every day the Gatekeeper drags me out and makes me burn dead beasts with him. Some exercise."

"Is that so bad?"

"It's not fun and games. We load up the cart with carcasses, haul them out to the Apple Grove, douse them with oil, and torch them. But before that, the Gatekeeper lops off the heads with a hackblade. You've seen his magnificent tool collection, haven't you? The guy's not right in his head. He'd hack the whole world to bits if he had his way."

"Is the Gatekeeper what they call Townfolk?"

"No, I don't think he's from here. The guy takes pleasure in dead things. The Townpeople don't pay him any mind. As if they could. We've already gotten rid of loads of beasts. This morning there were thirteen dead, which we have to burn after this."

The shadow digs his heels into the frozen ground.

"I found the map," says my shadow. "Drawn much better than I expected. Thoughtful notes, too. But it was just a little late."

"I got sick," I say.

"So I heard. Still, winter was too late. I needed it earlier. I could have formulated a plan with time to spare."

"Apian?"

"A plan of escape. What else? You didn't think I wanted a map for my amusement, did you?"

I shake my head. "I thought you would explain to me what's what in this Town. After all, you ended up with almost all our memories."

"Big deal," says my shadow. "I got most of our memories, but what am I supposed to do with them? In order to make sense, we'd have to be put back together, which is not going to happen. If we try anything, they'd keep us apart forever. We'd never pull it off. That's why I thought things out for myself. About the way things work in this Town."

"And did you figure anything out?"

"Some things I did. But nothing I can tell you yet. Without more details to back it all up, it would hardly be convincing. Give me more time, I think I'll have it. But by then it might already be too late. Since winter came on, I am definitely getting weaker. I might draw up an escape plan, but would I even have the strength to carry it out? That's why I needed the map sooner."

I look up at the elm tree overhead. A mosaic of winter sky shows between the branches.

"But there is no escape from here," I say. "You looked over the map, didn't you? There is no exit. This is the End of the World."

"It may be the End of the World, but it has to have a way out. I know that for certain. Look at the sky. Where do those birds go when they fly over the Wall? To another world. If there was nothing out there, why surround the place with a Wall? It has to let out somewhere."

"Or maybe—"

"Leave it to me, I'll find it," he cuts me short. "We'll get out of here. I don't want to die in this miserable hole."

He digs his heel into the ground again. "I repeat what I said at the very beginning: this place is wrong. I know it. More than ever. The problem is, the Town is perfectly wrong. Every last thing is skewed, so that the total distortion is seamless. It's a whole. Like this—"

My shadow draws a circle on the ground with his boot.

"The Town is sealed," he states, "like this. That's why the longer you stay in here, the more you get to thinking that things are normal. You begin to doubt your judgment. You get what I'm saying?"

"Yes, I've felt that myself. I get so confused. Sometimes it seems I'm the cause of a lot of trouble."

"It's not that way at all," says my shadow, scratching a meandering pattern next to the circle. "We're the ones who are right. They're the ones who are wrong, absolutely. You have to believe that, while you still have the strength to believe. Or else the Town will swallow you, mind and all."

"But how can we be absolutely right? What could their being absolutely wrong mean? And without memory to measure things against, how could I ever know?"

My shadow shakes his head. "Look at it this way. The Town seems to contain everything it needs to sustain itself in perpetual peace and security. The order of things remains perfectly constant, no matter what happens. But a world of perpetual motion is theoretically impossible. There has to be a trick. The system must take in and let out somewhere."

"And have you discovered where that is?"

"No, not yet. As I said, I'm still working on it. I need more details."

"Can you tell me anything? Perhaps I can help."

My shadow takes his hands out of his pockets, warms them in his breath, then rubs them on his lap.

"No, it's too much to expect of you. Physically I'm a mess, but your mind is in no shape either. The first thing you have to do is recover. Otherwise, we're both stuck. I'll think these things out by myself, and you do what you need to do to save yourself."

"My confidence is going, it's true," I say, dropping my eyes to the circle on the ground.

"How can I be strong when I do not know my own mind? I am lost."

"That's not true," corrects my shadow. "You are not lost. It's just that your own thoughts are being kept from you, or hidden away. But the mind is strong. It survives, even without thought. Even with everything taken away, it holds a seed—your self. You must believe in your own powers."

"I will try," I say.

My shadow gazes up at the sky and closes his eyes.

"Look at the birds," he says. "Nothing can hold them. Not the Wall, nor the Gate, nor the sounding of the horn. It does good to watch the birds."

I hear the Gatekeeper calling. I am to curtail my visit.

"Don't come see me for a while," my shadow whispers as I turn to go. "When it comes time, I'll arrange to see you. The Gatekeeper will get suspicious if we meet, which will only make my work harder. Pretend we didn't get along"

"All right," I say.

"How did it go?" asks the Gatekeeper, upon my return to the Gatehouse. "Good to visit after all this time, eh?"

"I don't really know," I say, with a shake of the head.

"That's how it is," says the Gatekeeper, satisfied.

Meal, Elephant Factory, Trap

Climbing the rope was easier than climbing the steps. There was a strong knot every thirty centimeters. Rope in both hands, I swung suspended, bounding off the tower. A regular scene from The Big Top. Although, of course, in the film the rope wouldn't be knotted; the audience wouldn't go for that.

I looked up from time to time. She was shining her light down at me, but I could get no clear sense of distance. I just kept climbing, and my gut wound kept throbbing. The bump on my head wasn't doing bad either.

As I neared the top, the light she held became bright enough for me to see my whole body and surroundings. But by then I'd gotten so used to climbing in the dark that actually seeing what I was doing slowed me down and I nearly slipped a couple of times.

I couldn't gauge distance. Lighted surfaces jumped out at me and shadowed parts inverted into negative.

Sixty or seventy knots up, I reached the summit. I grabbed the rock overhang with both hands and pushed up like a competition swimmer at poolside. My arms ached from the long climb, so it was a struggle. She grabbed my belt and helped pull me up.

"That was close," she said. "A few more minutes and we'd have been goners."

"Great," I said, stretching out on the level and taking a few deep breaths, "just great. How far up did the water come?"

She set her light down and pulled up the rope, hand over hand. At the thirtieth knot she stopped and passed the rope over to me. It was dripping wet.

"Did you find your grandfather?"

"Why of course," she beamed. "He's back there at the altar. But he's sprained his foot. He got it caught in a hole."

"And he made it all the way here with a sprained foot?"

"Yes, sure. Grandfather's in very good shape."

"I'd imagine so," I said.

"Let's go. Grandfather's waiting inside. There's lots he wants to talk to you about."

"Likewise here," I said.

I picked up the knapsack and followed her toward the altar. This turned out to be nothing more than a round opening cut into a rock face. It led into a large room illuminated by the dim amber glow of a propane lamp set in a niche, the walls textured with myriad shadows from the grain of the rock. The Professor sat next to the lamp, wrapped in a blanket. His face was half in shadow. His eyes looked sunken in the half-light, but in fact he was chipper as could be.

"Seems we almost lost you," the Professor greeted me ever so gladly. "I knew the water was goint'rise, but I thought you'd get here a bit sooner."

"I got lost in the city, Grandfather," said his chubby granddaughter. "It was almost a whole day before I finally met up with him."

" Tosh," said the Professor. "But we're here now and 'sail the same."

"Excuse me, but what exactly is 'sail the same?" I asked.

"Now, now, hold your horses. I'll get't'all that. Just take yourself a seat. First thing, let's just remove that leech from your neck."

I sat down near the Professor. His granddaughter sat beside me. She lit a match and held it to the giant sucker feasting on my neck. It was big as a wine cork. The flame hissed as it touched the engorged parasite. The leech fell to the ground, wriggling in spasms, until she put it out of its misery.

My neck felt seared. If I turned my head too far, I thought the skin would slip off like the peel of a rotten tomato. A week of this life-style and I'd be a regular scar tissue showcase, like one of those full-color photos of athlete's foot posted in the windows of pharmacies.

Gut wound, lump on the head, leech welt—throw in penile dysfunction for comic relief.

"You wouldn't by any chance have brought along anything to eat, would you?" the Professor asked me. "Left in such a hurry, I didn't pack."

I opened the knapsack and removed several cans, squashed bread, and the canteen, which I handed to him. The Professor took a long drink of water, then examined each can as if inspecting vintage wines. He decided on corned beef and peaches.

"Care't'join me?" offered the Professor.

I declined. We watched the Professor tear off some bread and top it with a chunk of corned beef, then dig into it with real zest. Next he had at the peaches and even brought the can up to his lips to drink the syrup. I contented myself with whiskey, for medicinal purposes. It helped numb my various aches and pains. Not that the alcohol actually reduced the pain; it just gave the pain a life of its own, apart from mine.

"Yessir, that hit the spot," the Professor thanked me. "I usually keep two or three days' emergency rations here, but this time it so happened I hadn't replenished supplies. Unforgivable. Get accustomed to carefree days and you drop your guard. You know the old saying: When the sun leaks through again, patch the roof for rain. Ho-ho-ho."

"Now that you've finished your meal," I began, "there's a few things we need to talk about. Let's take things in order, starting from the top. Like, what is it you were trying to do? What did you do? What was the result? And where does that leave me ?"

"I believe you'll find it all rather technical," the Professor said evasively.

"Okay, then break it down. Make it less technical." "That may take some time."

"Fine. You know exactly how much time I've got." "Well, uh, 't'begin with," the Professor owned up, "I must apologize. Research is research, but I tricked you and used you and I put your life in danger. Set a scientist down in front of a vein of knowledge and he's goint'dig. It's this pure focus, exclusive of all view to loss or gain, that's seen science achieve such uninterrupted advances i . . You've read your Aristotle."

"Almost not at all," I said. "I grant you your pure scientific motives. Please get to the point."

"Forgive me, I only wanted't'say that the purity of science often hurts many people, just like pure natural phenomena do. Volcanic eruptions bury whole towns, floods wash bridges away, earthquakes knock buildings flat—"

"Grandfather!" interrupted his chubby granddaughter. "Do we really have the time for that? Won't you hurry up a bit with what you have to say?"

"Right you are, child, right you are," said the Professor, taking up his granddaughter's hand and patting it. "Well, then, uh, what is it y' want't'know? I'm terrible at explanations. Where should I begin?"

"You gave me some numbers to shuffle. What were they all about?"

"T'explain that, we have't'go back three years. I was working at System Central Research. Not as a formal employee researcher, but as a special outside expert. I had four or five staffers under me and the benefit of magnificent facilities. I had all the money I could use. I don't put much by money, mind you, and I do have something of an allergy't'servin' under others. But even so, the resources the System put at my disposal and the prospect of puttin' my research findings into practice was certainly attractive."

"The System was at a critical point just then. That's't'say, virtually every method of data-scramblin' they devised't' protect information had been found out by the Semiotecs. That's when I was invited't'head up their R&D."

"I was then—and still am, of course—the most able and the most ambitious scientist in the field of neurophysiology. This the System knew and they sought me out. What they were after wasn't further complexification or sophistication of existing methods, but unprecedented technology. Wasn't the kind of thinkin' you get from workaday university lab scholars, publish-or-perishin' and countin' their pay. The truly original scientist is a free individual."

"But on entering the System, you surrendered that freedom," I countered.

"Exactly right," said the Professor. "I did my share of soul-searchin' on that one. Don't mean't'excuse myself, but I was eagerer than anythint'put my theories into practice. Back then, I already had a fully developed theory, but no way't'verify it. That's one of the drawbacks of neurophysiology; you can't experiment on animals like you can in other branches of physiology. No monkey's got functions complex enough't'stand in for human subconscious psychology and memory."

"So you used us as your monkeys."

"Now, now, let's not jump to conclusions. First, let me give you a quick rundown on my theories. There's one Kiven about codes, and that is there's no such thing as a code that can't be cracked. The reason bein' that codes are composed accordin' to certain basic principles. And these principles, it doesn't matter how complicated or how cxactin', ultimately come down to commonalities intelligible to more than one person. Understand the principle and you can crack the code. Even the most reliable book-to-book codes, where two people exchange messages denotin' words by page and line number in two copies of the same edition of the same book—even then, if someone discovers the right book, the game is up."

"That got me't'thinkin'. There's only one true crack-proof method: you pass information through a 'black boxt'scramble it and then you pass the processed information back through the same black box't'unscramble it. Not even the agent holdin' the black box would know its contents or principle. An agent could use it, but he'd have no understanding of how it worked. If that agent didn't know how it worked, no one could steal the information. Perfect."

"So the black box is the subconscious."

"Yes, that's correct. Each individual behaves on the basis of his individual mnemonic makeup. No two human beings are alike; it's a question of identity. And what is identity? The cognitive system arisin' from the aggregate memories of that individual's past experiences. The layman's word for this is the mind. Not two human beings have the same mind. At the same time, human beings have almost no grasp of their own cognitive systems. I don't, you don't, nobody does. All we know—or think we know—is but a fraction of the whole cake. A mere tip of the icing."

"Now let me ask you a simple question: are you bold, or are you timid?"

"Huh?" I had to think. "Sometimes I get bold and sometimes I'm timid. I can't really say."

"Well, there's your cognitive system for y't. You just can't say all at once. Accordint'what you're up against, almost instantaneously, you elect some point between the extremes. That's the precision programming you've got built in. You yourself don't know a thing about the inner shenanigans of that program. 'Tisn't any need for you't'know. Even without you knowin', you function as yourself. That's your black box. In other words, we all carry around this great unexplored 'elephant graveyard' inside us. Outer space aside, this is truly humanity's last terra incognita."

"No, an 'elephant graveyard' isn't exactly right. 'Tisn't a burial ground for collected dead memories. An 'elephant factory' is more like it. There's where you sort through countless memories and bits of knowledge, arrange the sorted chips into complex lines, combine these lines into even more complex bundles, and finally make up a cognitive system. A veritable production line, with you as the boss. Unfortunately, though, the factory floor is off-limits. Like Alice in Wonderland, you need a special drug't'shrink you in."

"So our behavioral patterns run according to commands issued by this elephant factory?"

"Exactly as you say," said the old man. "In other words—"

"Just a second. I have a question."

"Certainly, certainly."

"I get the gist. But the thing is, those behavioral patterns do not dictate actual surface-level behavior. Say I get up in the morning and decide whether I want to drink milk or coffee or tea with my toast. That depends on my mood, right?"

"Exactly so," said the Professor with a nod. "Another complication's that the subconscious mind is always changin'. Like an encyclopedia that keeps puttin' out a whole new edition every day. In order't'stabilize human consciousness, you have to clear up two trouble spots."

"Trouble spots?" I asked. "Why would there be any trouble spots? We're talking about perfectly normal human actions."

"Now, now," said the Professor. "Pursue this much fur-iher and we enter into theological issues. The bottom line liere, if you want't'call it that, is whether human actions are plotted out in advance by the Divine, or self-initiated begin-nin' to end. Of course, ever since the modern age, science has stressed the physiological spontaneity of the human organism. But soon's we start askin' just what this spontaneity is, nobody can come up with a decent answer. Nobody's got the keys't'the elephant factory inside us. Freud and Jung and all the rest of them published their theories, but all they did was't'invent a lot of jargon't'get people talkin'. Gave mental phenomena a little scholastic color."

Whereupon the Professor launched into another round of guffaws. Oh-ho-ho. The girl and I could only wait for him to stop laughing.

"Me, I'm of a more practical bent," continued the Professor. " Render unto Caesar what is Caesar's and leave the rest alone. Metaphysics is never more than semantic pleasantries anyway. There's loads't'be done right here before you go drainin' the reality out of everything. Take our black box. You can set it aside without so much as ever touchin' it, or you can use its bein' a black box't'your advantage. Only—" paused the Professor, one finger raised theatrically, "only—you have't'solve two problems. The first is random chance on the surface level of action. And the other is changes in the black box due't'new experiences. Neither is very easy't'resolve. Because, like you said, both are perfectly normal for humans. As long as an individual's alive, he will undergo experience in some form or other, and those experiences are stored up instant by instant. To stop experiencin' is to die."

"This prompted me't'hypothesize. What would happen if you fixed a person's black box at one point in time? If afterwards it were't'change, well, let it change. But that black box of that one instant would remain, and you could call it up in just the state it was. Flash-frozen, as it were."

"Wait a minute. That would mean two different cognitive systems coexisted in the same person."

"You catch on quick," said the old man. "It confirms what I saw in you. Yes, Cognitive System A would be on permanent hold, while the other would go on changin'… a', a", a'"… without a moment's pause. You'd have a stopped watch in your right pocket and a tickin' watch in your left. You can take out whichever you want, whenever you want."

"We can address the other problem by the same principle: cut off all options open to Cognitive System A at surface level. Do you follow?"

No, I didn't.

"In other words, we scrape off the surface just like the dentist scrapes off plaque, leaving the core consciousness. No more margin of error. We just strip the cognitive system of its outer layers, freeze it, and plunk it in a secret compartment. That's the original scheme of shuffling. This much I'd worked out in theory for myself before I joined the System."

"In order to conduct brain surgery?"

"Yes, but only as necessary," the Professor allowed. "No doubt, if I'd proceeded with my research, I would have bypassed the need for surgery. Sensory-deprivation para-hypnotics or some such external procedure't'create similar conditions. But for now, there's only electrostimulation. That is, artificial alteration of currents flowin' through the brain circuitry. Nothin' fancy. 'Tisn't anythin' more than a slight modification of normal procedures in current use on psychotics or epileptics. Cancel out electrical impulses emitted by the aberration in the… I take it I should dispense with the more technical details?"

"If you don't mind," I said.

"Well, the main thing is, we set up a junction box't' channel brain waves. A fork, as it were. Then we implant electrodes along with a tiny battery so that, at a given signal, the junction box switches over, click-click."

"You put electrodes and a battery inside my head?"

"Of course."

"Great," I said, "just great."

"No need for alarm. Isn't anythin' so frightenin'. The implant is only the size of an azuki bean, and besides, there's plenty of people walkin' around with similar units and pacemakers in other parts of their body."

"Now the original cognitive system—the stopped-watch circuit—is a blind circuit. Once you enter that circuit, you don't perceive a thing in your own flow of thought; you have absolutely no awareness of what you think or do. If we didn't arrange it that way, you'd be in there foolin' with the cognitive system yourself."

"But there's got to be problems with irradiating the core consciousness after it's stripped. That's what one of your staff told me after the operation."

"All very correct. But we still hadn't established that at the time. We were workin' on supposition. Well, we'd done a few human experiments. Didn't want't'expose valuable human resources such as you Calcutecs't'any dangers right off the bat, y'know. The System selected ten people for us. We operated on them and watched for results."

"What sort of people?"

"The System wouldn't tell us. They were ten healthy males, with no history of mental irregularities. IQ 120 or above. Those were the only conditions. The results were moderately encouragin'. In seven out of the ten, the junction box functioned without a hitch. In the other three, the junction box didn't work; they couldn't switch cognitive system or they confused them or they got both."

"What happened to the confused ones?"

"We fixed them back the way they were, disconnected the junction box. No harm done. Meanwhile, we continued trainin' the seven, until a number of problems became apparent: one was a technical problem, others had't'do with the subjects themselves. First of all, the call sign for switchin' the junction box was too codependent. We started off with a five-digit number, but for some reason a few of them switched junctions at the smell of grape juice. Found that out one lunchtime."

The chubby girl giggled next to me, but for me it was no laughing matter. Soon after my shuffling actualization, I'd been by disturbed by all sorts of different smells. For example, I could swear the girl's melon eau de cologne made me hear things. If your cognitive system turned over each time you smelled a different odor, it could be disaster.

"We solved that by dispersin' special sound waves between the numbers. Call signs that caused reactions very similar't'the reactions't'certain smells. Another problem, depending on the individual, was that the junction box would kick over, but the stored cognitive system wouldn't operate. We found out, after investigatin' all sorts of possibilities, that the problem lay with the subjects' cognitive system from the very beginnin'. The subjects' core consciousness was unstable or too rarefied. Oh, they were healthy and sharp enough, but pyschologically they hadn't established an identity. Or rather, they had identity enough, but had put things in order accordint'that identity, so you couldn't do a thing with them. Just because you got the operation didn't mean you could do shuffling. As clear as could be, there was a screenin' factor at work here."

"Well, that left three of them. And in all three, the junction box kicked over at the prescribed call sign and the frozen cognitive system functioned stably and effectively. So we did additional experiments with them for one more month, and at that point we were given the go-ahead."

"And then, I gather, you proceeded with shuffling actualization?"

"Exactly so. The next phase was't'conduct tests and interviews with close to five hundred Calcutecs. We selected twenty-six healthy males with no history of mental disorders, who exhibited strong psychological independence, and who could control their own behavior and emotions. This all took quite some dbin'. Seein' as tests and interviews leave a lot in the dark, I had the System draw up detailed files on each and every one of you. Your family background, upbringin', school records, sex life, drinkin'… anyway, every thin'."

"Just one thing I don't understand," I spoke up. "From what I've heard, our core consciousness, our black boxes, are stored in the System vault. How is that possible?"

"We did thorough tracings of your cognitive systems. Then we made simulations for storage in a main computer bank. We did it as a kind of insurance; you'd be stuck if anything happened't'you."

"A total simulation?"

"No, not total, of course, but functionally quite close't' total, since the effective strippin' away of surface layers made tracin' that much easier. More exactly, each simulation was made up of three sets of planar coordinates and holographs. With previous computers that wasn't possible, but these new-generation computers incorporate a good many elephant factory-like functions in themselves, so they can handle complex mental constructs. You see, it's a question of fixed structural mappin'. It's rather involved, but't'put it simple for the layman, the tracin' system works like this: first, we input the electrical pattern given off by your conscious mind. This pattern varies slightly with each readin'. That's because your chips keep gettin' rearranged into different lines, and the lines into bundles. Some of these rearrangements are quantifiably meaningful; others not so much. The computer distinguishes among them, rejects the meaningless ones, and the rest get mapped as a basic pattern. This is repeated and repeated and repeated hundreds of thousands of unit-times. Like overlayin' plastic film cells. Then, after verifyin' that the composite won't stand out in greater relief, we keep that pattern as your black box."

"You're saying you reproduced our minds?"

"No, not at all. The mind's beyond reproducin'. All I did was fix your cognitive system on the phenomenological level. Even so, it has temporal limits—a time frame. We have't'throw up our hands when it comes to the brain's flexibility. But that's not all we did. We successfully rendered a computer visualization from your black box."

Saying this, the Professor looked first at me, then at his chubby granddaughter.

"A video of your core consciousness. Something no-body'd ever done. Because it wasn't possible. I made it possible. How do you think I did it?"

"Haven't a clue."

"We showed our subjects some object, analyzed the electromagnetic reactions in their brains, converted that into numerics, then plotted these as dots. Very primitive designs in the early stages, but over many many repetitions, revisin' and fillin' in details, we could regenerate what the subjects had seen on a computer screen. Not nearly so easy as I've described it, but simply put, that's what we did. So that after goin' over and over these steps how many times, the computer had its patterns down so well it could autosimu-late images from the brain's electromagnetic activity. The computer's really cute at that."

"Next thing I did was't'read your black box into the computer pre-programmed with those patterns, and out came an amazin' graphic renderin' of what went on in your core consciousness. Naturally, the images were jumbled and fragmentary and didn't mean much in themselves. They needed editin'. Cuttin' and pastin', tossin' out some parts, resequencin', exactly like film editin'. Rearrangin' everything into a story."

"A story?"

"That shouldn't be so strange," said the Professor. "The best musicians transpose consciousness into sound; painters do the same for color and shape. Mental phenomena are the stuff writers make into novels. It's the same basic logic. Of course, as encephalodigital conversion, it doesn't represent an accurate mappin', but viewin' an accurate, random succession of images didn't much help us either. Anyway, this 'visual edition' proved quite convenient for graspin' the whole picture. True, the System didn't have it on its agenda. This visualization was all me, dabblin'." "Dabbling?"

"I used't'—before the War, that is—work as an assistant editor in the movies. That's how I got so good at this line of work. Bestowin' order upon chaos. I did the editin' alone in my laboratory, without assistance from any other staff. Nobody had any idea what I had holed myself up doin'. So of course, I could walk off with those visualizations without anybody the worse for knowin'. They were my treasures." "Did you render all twenty-six visualizations?" "Sure did. Did them all, for what it's worth. Gave each one a title, and that title became the title of the black box. Yours is 'End of the World', isn't it?"

-"You know it is. 'The End of the World'. It's a rather unusual title, wouldn't you say?"

"We'll go into that later," said the Professor. "The fact is, nobody knew I'd succeeded in visualizin' twenty-six consciousnesses. I never told anyone. I wanted't'take the research beyond anythin' related to the System. I'd completed the project I was commissioned't'do, and I'd taken care of the human experiments I needed for my research. I didn't want't'hang around there any longer. I told the System I wanted't'quit. They didn't want me't'quit; I knew too much. If I were't'run over to the Semiotecs at this stage, the whole shuffling plan would come to nothin', or so they thought. Wait three months, they told me. Continue with whatever research I felt like in their laboratory. They'd pay me a special bonus. In three months' time, their top-secret protection system would be perfected, so if I was going t'leave, hang around until then."

"Now, I'm a free-born individual and such restrictions don't sit well with me, but, well, this wasn't such a bad deal. So I decided't'hang around. Still, takin' things easy doesn't lead to much good. With all this time and these subjects on my hands, I hit upon the idea of installin' another separate circuit to the junction boxes in your brains. Make it a three-way cognitive circuitry. And into this third circuit, I'd load my edited version of your core consciousness." "Why would you want to do that?" "For one thing, just't'see what effect it'd have on the subjects. I wanted't'find out how an edited consciousness put in order by someone else would function in the original subjects themselves. No such precedent in all of human history. And for another thing—an incidental motivation, granted—if the System really was tellin' me't'do whatever I liked, well then, by darn, I was goint'take them at their word and do what I liked. I thought I'd go ahead and concoct one more function they'd never suspect."

"And for that reason, you screwed around in our heads, laying down those electric train tracks of yours?"

"Well, a scientist isn't one for controlling his curiosity. Of course, I deplore how those scientists cooperated with the Nazis conductin' vivisection in the concentration camps. That was wrong. At the same time, I find myself thinkin', if you're goint'do live experiments, you might as well do something a little spiffier and more productive. Given the opportunity, scientists all feel the same way at the bottom of their heart. I was only addin' a third widget where there already was two, slightly alterin' the current of circuits already in the brain. What could be the harm of usin' the same alphabet flashcards't'spell an extra word?"

"But the truth is, aside from myself, all the others who underwent shuffling actualization have died. Now why is that?"

"That's somethin'… even I don't know why," admitted the Professor. "Exactly as y' say, twenty-five of the twenty-six Calcutecs who underwent shuffling actualization have died. All died the same way, as if their fates were sealed. They went to bed one night; come morning they were dead."

"Well, then, what about me?" I said. "Come tomorrow, I might be dead."

"Now hold your horses, son," held forth the Professor from inside his blanket. "All twenty-five of them died within a half-year of each other. Anywhere from one year and two months to one year and eight months after the actualization. And here you are, three years and three months later, still shuffling with no problems. This leads us't'believe that you possess some special oomph that the others didn't."

"Special? In what sense, special?"

"Now, now. Just a minute, please. Let me ask you this: since your actualization, you haven't suffered any strange symptoms, have you? No hearin' things or hallucinatin' or faintin' or anythin' like that?"

"No," I said. "Haven't seen or heard things. Except, as I said, I have become sensitive to fruit smells."

"That was common't'everyone. Even so, that hasn't resulted in any auditory or visual hallucinations, has it? No sudden loss of consciousness?"

"No."

"Hmm," the Professor trailed off. "Anythin' else?"

"Well, yes, as a matter of fact. Something I'd totally forgotten as ever having happened to me just came back to me as a memory. Up until now, I've recalled only fragments of memories, so they didn't seem to call for attention. But as we were making our way here, I experienced one long, vivid continuity, triggered by the sound of the water. It was no hallucination. It was a substantial memory. I know that beyond a doubt."

"No, it wasn't," the Professor contradicted me flatly. "You may have experienced it as a memory, but that was an artificial bridge of your own makin'. You see, quite naturally there are going't'be gaps between your own identity and my edited input consciousness. So you, in order't'justify your own existence, have laid down bridges across those gaps."

"I don't follow. Not once has anything like that ever happened to me before. Why suddenly now does it choose to spring up?"

"'That's because I switched the junction to the third circuit," said the Professor. "But, well, let's just take things in order. Make things difficult if we don't, and it'd be even harder for you't'follow."

I took a gulp of whiskey. This was turning into a nightmare.

"When the first eight men died one after another, I got a call from System Central. Ascertain the cause of death, they said. Frankly, I didn't want't'have any more't'do with them, but since it was my technology, not't'mention a matter of life and death, I couldn't very well ignore them. Anyway, I went't'have a look. They briefed me on the circumstances of the deaths and showed me the brain autopsy findings. Like I told y', all eight had died of unknown causes in the same way. There was no apparent damage to brain or body; all had quietly stopped breathing in their sleep." "You didn't discover the cause of death?" "Never found out. Naturally, I came up with a few hypotheses. If for any reason the junction boxes we implanted in their brains burnt out or just went down, mightn't the cognitive systems muddle together and overload brain functions? Or say it wasn't a junction problem, supposing there was something fundamentally wrong with liberatin' the core consciousness even for short periods of time, maybe it was simply too much for the human brain?" The Professor then paused to pull the blanket up to his chin.

"The brain autopsies didn't clear anything up?"

"The brain is not a toaster, and it isn't a washing machine either. Codes and switches are pretty much imperceptible to the eye. All we're talkin' about is redirectin' the flow of invisible electrical charges, so takin' out the junction box for testin' after the subject's dead won't tell you anything. We can detect irregularities in a living brain but not in a dead brain. Of course, if there's hemorrhagin' or tumors, we can tell, but there wasn't any. These brains were i lean."

"Next thing we did w'ks't'call in ten of the surviving subjects to the lab and check them all over again. Did brain scans, switched over cognitive systems't'see that the junctions were working right. Conducted detailed interviews, asked them whether they had any physical disorders, any auditory or visual hallucinations. But none of them had any problems't'speak of. All were healthy and kept up a perfectly unremarkable career of shuffling jobs. We could only conclude that the ones who died had had some a priori glitch in their brain that rendered them unsuitable for shuffling. We didn't have any idea what that glitch might be. That was something for further investigation, something't'be solved before attemptin' a second round of shuffling actualization."

"But as it turned out, we were wrong. Within one month, another five died, three of which had undergone our thorough recheck. Persons we had deemed fit on the basis of our recheck had up and died soon after without battin' an eyelash. Needless't'say, this came as quite a shock to us. Half of our twenty-six subjects were dead, and we were powerless't'know why. This was no longer a question of fit versus unfit; this was a basic program design error. The idea of switchin' between two different cognitive systems was untenable from the very beginning as far as the brain was concerned. At that point I proposed that the System freeze the project. Take the junction boxes out of the survivors' heads, cancel all further shuffling jobs. If we didn't, we'd lose everyone. Out of the question, the System informed me. They overruled me."

"They what?"

"They overruled me. The shuffling system itself was extremely successful, and it was unrealistic't'expect the System't'return to square one. And besides, we weren't sure the rest would die. If any survived, they'd serve as ideal research samples toward the next generation. That's when I stepped down."

"And only I survived."

"Correct."

I leaned my head back against the rock wall and stroked my growth of beard. When was the last time I shaved?

"So why didn't I die?"

"This is also only a hypothesis," resumed the Professor. "A hypothesis built on hypotheses. Still I can't be too far off the mark. It seems you were operatin' under multiple cognitive systems't'begin with. Not even you knew you were dividin' your time between two identities. Our paradigm of one watch in one pocket, another watch in another pocket. You probably had your own junction box that gave you a kind of mental immunity."

"Got any evidence?"

"'Deed I do. Two or three months ago, I went back and replayed all twenty-six visualizations. And something struck me. Yours was the least random, most coherent. Well-plotted, even perfect. It could have passed for a novel or a movie. The other twenty-five were different. They were all confused, murky, ramblin', a mess. No matter how I tried't'edit them, they didn't pull together. Strings of nonsequential dream images. They were like children's finger paintings."

"I thought and thought, now why should that be? And I came to one conclusion: this was somethin' you yourself made. You gave structure to your images. It's as if you descended to the elephant factory floor beneath your consciousness and built an elephant with your own hands. Without you even knowin'!"

"I find that very hard to believe," I said.

"I can think of many possible causes," the Professor assured me. "Childhood trauma, misguided upbringin', over-objectified ego, guilt… Whatever it was made you extremely self-protective, made you harden your shell."

"Well, okay. What if it's so, where does that lead?"

"Nowhere special. If left alone, you'd probably live a good, long life," said the Professor. "But unfortunately, that's not goint'happen. Like or not, you're the key to the outcome of these whole idiotic infowars. It won't be long before the System starts up a second-generation project with you as their model. They'll tweak and probe and buzz every part of you there is't'test. I don't know how far they'll go, but I can assure you it won't be pleasant. I wanted't' save you from all that."

"Wonderful," I groaned. "You're to going to save me by boycotting the project, is that it?"

"No, but you've got to trust me."

"Trust you? After you've been deceiving me all this time? Lying to me, making me do those phony tabulations…"

"I wanted't'get to you before either the System or Semiotecs did, so I could test my hypothesis. If I could come up with positive proof, they wouldn't have't'put you through the wringer. Embedded in the data I gave you was a call sequence. After you switched over to your second cognitive system, you switched one more click to the third cognitive system."

"The one you visualized and edited."

"Exactly," said the Professor, nodding.

"How exactly is that going to prove your hypothesis?"

"It's a question of gaps," answered the Professor. "You've got an innate grasp on your core consciousness. So you have absolutely no problem as far as your second cognitive system. But this third circuit, being something I edited, will be part foreign, and the difference should call up some kind of reaction on your part. From measuring that, I should have been able't'obtain a complete electropic-tographic registration of your subconscious mind."

" Should have been able?"

"Yes, should have been able. That was before the Semiotecs teamed up with the INKlings and destroyed my labo-ratory. They walked off with all my research materials, everything that mattered."

"Are you sure? We thought they left critical things alone."

"No, I went back to the lab and checked. There's not one thing of importance left. There's not a chance I could make meaningful measurements with what's left."

"So how does all this have anything to do with the world ending?" An innocent question.

"Accurately speaking, it isn't this world. It's the world in your mind that's going to end."

"You've lost me," I said.

"It's your core consciousness. The vision displayed in your consciousness is the End of the World. Why you have the likes of that tucked away in there, I can't say. But for whatever reason, it's there. Meanwhile, this world in your mind here is coming to an end. Or't'put it another way, your mind will be living there, in the place called the End of the World."

"Everythin' that's in this world here and now is missin' from that world. There's no time, no life, no death. No values in any strict sense. No self. In that world of yours, people's selves are externalized into beasts."

"Beasts?"

"Unicorns," said the Professor. "You've got unicorns, herded in a town, surrounded by a wall."

"Does this have something to do with the unicorn skull you gave me?"

"That was a replica. I made it. Pretty realistic, eh? Modelled it after a visualized image of yours. It took quite some doin'. No particular significance to it. Just thought I'd make it up on a phrenological whim, ho ho. My little gift to you."

"Now just a minute, please," I said. "I'm willing to swallow that such a world exists in the depths of my consciousness. I'll buy that you edited it into a clearer form and input it into a third circuit in my head. Next, you've sent in call signs to direct my consciousness over there to do shuffling. Correct so far?"

"Correct."

"Then, what's this about the world ending? Once the shuffling is over, isn't the third circuit going to break and my consciousness automatically return to circuit one?"

"No. That's the problem," corrected the Professor. "If it went like that, things'd be easy, but it doesn't. The third circuit doesn't have an override function."

"You mean to tell me my third circuit's permanently engaged?"

"Well, yes, that's the size of it."

"But right now I'm thinking and acting according to my first circuit."

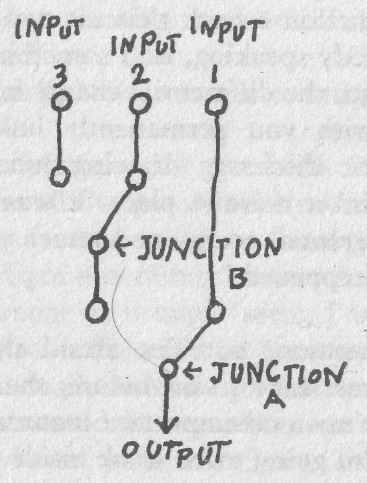

"That's because your second circuit's plugged up. If we diagram it, the arrangement looks like this," said the Professor. He sketched a diagram on a memo pad and handed it to me.

"This here's your normal state. Junction A connected to Input 1, Junction B to Input 2. Whereas now," continued the Professor, drawing another diagram on another sheet, "it's like this."

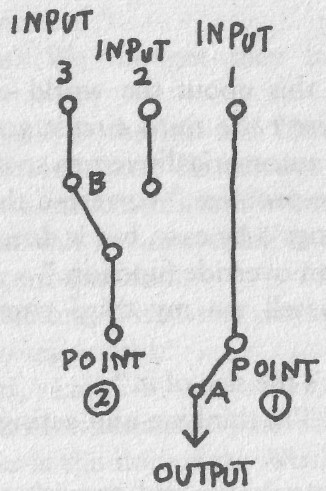

"Get the picture? Junction b's linked up with the third circuit, while Junction A is auto-switched't'your first circuit. This being the case, it's possible for you't'think and act in the first circuit mode. However, this is only temporary. We have't'switch Junction B back't'circuit two, but soon. The third circuit, strictly speaking, isn't something of your own. If we just let it go, the differential energy is goint'melt the junction box, with you permanently linked into circuit three, the electric discharge drawing Junction A over to Point 2 and fusin' it there in place. It was my intention't' measure the differential energy and return you back to normal before that happened."

"Intention!"

"Yes, my intention, but I'm afraid that hand's been played out for me. Like I said before, the fools destroyed my lab and stole my most important materials."

"You mean I'm going to be stuck inside this third circuit with no hope of return?"

"Well, uh, yes. You'll be livin' in the End of the World. I'm terribly, terribly sorry."

"Terribly sorry?" The words veered out abstractly. "Terribly sorry? Easy for you to say, but what the hell's going to become of me? This is no game! This is my life!"

"I never dreamed anythin' like this would happen. I never dreamed the Semiotecs and INKlings would form a pact. And now System Central's probably thinkin' we've got somethin' goin' on our own. That is, the Semiotecs, they've had their sights on you, too. They as good as informed the System of that. And as far as the System's concerned, we betrayed them, so even if it meant settin' back the whole of shuffling, they'd just as soon eliminate us. And that's exactly what the Semiotecs have in mind. They'd be delighted if our own Calcutecs did us in—that would mean the end of the System's edge on Phase Two Shuffling. Or they'd be happy if we went runnint'them—what could be better? Either way, they have nothint'lose."

"Great," I said, "just great." Then those two guys who came and wasted my apartment and slit my stomach had been Semiotecs after all. They'd put on that song and dance of a story to divert System attention. Which meant I'd fallen right into their trap. "So it's all a foregone conclusion. I'm screwed. Both sides are after me, and if I stand still my existence is annulled."

"No, not annulled. Your existence isn't over. You'll enter another world."

"Interesting distinction," I grumbled. "Listen. I may not be much, but I'm all I've got. Maybe you need a magnifying glass to find my face in my high school graduation photo. Maybe I haven't got any family or friends. Yes, yes, I know all that. But, strange as it might seem, I'm not entirely dissatisfied with this life. It could be because this split personality of mine has made a stand-up comedy routine of it all. I wouldn't know, would I? But whatever the reason, I feel pretty much at home with what I am. I don't want to go anywhere. I don't want any unicorns behind fences."

"Not fences," corrected the Professor. "A wall."

"Whatever you say. A wall, fences, I don't need any of it," I fumed. "Will you permit me to get a little mad?"

"Well, under the circumstances, I guess it can't be helped," said the Professor, scratching his ear.

"As far as I can see, the responsibility for all this is one hundred percent yours. You started it, you developed it, you dragged me into it. Wiring quack circuitry into people's heads, faking request forms to get me to do your phony shuffling job, making me cross the System, -putting the Semiotecs on my tail, luring me down into this hell hole, and now you're snuffing my world! This is worse than a horror movie! Who the fuck do you think you are? I don't care what you think. Get me back the way I was."

The Professor grunted.

"I think he's right, Grandfather," interjected the chubby girl. "You sometimes get so wrapped up in what you're doing, you don't even think about the trouble you make for others. Remember that ankle-fin experiment? You've got to do something to help him."

"I thought I was doin' good, honest. Except circumstances kept turnin' worse and worse," the old man moaned. "Things're completely out of my hands. There's nothing I can do about it any more. There's nothin' you can do about it either."

"Just wonderful," I said.

"'Tis a small comfort, I know," the Professor said meekly, "but all's not lost. Once you're there in that world, you can reclaim everything from this world, everything you're goint'have't'give up."

"Give up?"

"That's right," said the Professor. "You'll be losin' everything from here, but it'll all be there."