The Wall

ON an overcast afternoon I make my way down to the Gatehouse and find my shadow working with the Gatekeeper. They have rolled a wagon into the clearing, replacing the old floorboards and sideboards. The Gatekeeper planes the planks and my shadow hammers them in place. The shadow appears altogether unchanged from when we parted.

He is still physically well, but his movements seem wrong. Ill-humored folds brew about his eyes.

As I draw near, they pause in their labors to look up.

"Well now, what brings you here?" asks the Gatekeeper.

"I must talk to you about something," I say.

"Wait till our next break," says the Gatekeeper, readdressing himself to the half-shaved board. My shadow glances in my direction, then resumes working. He is furious with me, I can tell.

I go into the Gatehouse and sit down at the table to wait for the Gatekeeper. The table is cluttered. Does the Gatekeeper clean only when he hones his blades? Today the table is an accumulation of dirty cups, coffee grounds, wood shavings, and pipe ash. Yet, in the racks on the wall, his knives are ordered in what approaches an aesthetic ideal.

The Gatekeeper keeps me waiting. I gaze at the ceiling, with arms thrown over the back of the chair. What do people do with so much time in this Town?

Outside, the sounds of planing and hammering are unceasing.

When finally the door does open, in steps not the Gatekeeper but my shadow.

"I can't talk long," whispers my shadow as he hurries past. "I came to get some nails from the storeroom."

He opens a door on the far side of the room, goes into the right storeroom, and emerges with a box of nails.

"I'll come straight to the point," says my shadow under his breath as he sorts through the nails. "First, you need to make a map of the Town. Don't do it by asking anyone else.

Every detail of the map must be seen with your own eyes. Everything you see gets written down, no matter how small."

"How soon do you need it?" I say.

"By autumn," speaks the shadow at a fast clip. "Also, I want a verbal report. Particularly about the Wall. The lay of it, how it goes along the Eastern Woods, where the River enters and where it exits. Got it?"

And without even looking my way, my shadow disappears out the door. I repeat everything he has told me. Lay of the Wall, Eastern Woods, River entrance and River exit. Making a map is not a bad idea. It will show me the Town and use my time well.

Soon the Gatekeeper enters. He wipes the sweat and grime off his face, and drops his bulk in the chair across from me.

"Well, what is it?"

"May I see my shadow?" I ask.

The Gatekeeper nods a few times. He tamps tobacco into his pipe and lights up.

"Not yet," he says. "It is too soon. The shadow is too strong. Wait till the days get shorter. Just so there is no trouble."

He breaks his matchstick in half and flips it onto the table.

"For your own sake, wait," he continues. "Getting too close to your shadow makes trouble. Seen it happen before."

I say nothing. He is not sympathetic. Still, I have spoken with my shadow. Surely the Gatekeeper will let down his guard again.

The Gatekeeper rises. He goes to the sink, and sloshes down cup after cup of water.

"How is the work?"

"Slow, but I am learning," I say.

"Good," says the Gatekeeper. "Do a good job. A body who works bad thinks bad, I always say."

I listen to my shadow nailing steadily.

"How about a walk?" proposes the Gatekeeper. "I want to show you something."

I follow him outside. As we enter the clearing, I see my shadow. He is standing on the wagon, putting the last sideboard in place.

The Gatekeeper strides across the clearing toward the Watchtower. The afternoon is humid and gray. Dark clouds sweep low over the Wall from the west, threatening to burst at any second. The sweat-soaked shirt of the Gatekeeper clings to his massive trunk and gives off a sour stink.

"This is the Wall," says the Gatekeeper, slapping the broad side of the battlements.

"Seven yards tall, circles the whole Town. Only birds can clear the Wall. No entrance or exit except this Gate. Long ago there was the East Gate, but they walled it up. You see these bricks? Nothing can dent them, not even a cannon."

The Gatekeeper picks up a scrap of wood and expertly pares it down to a tiny sliver.

"Watch this," he says. He runs the sliver of wood between the bricks. It hardly penetrates a fraction of an inch. He tosses the wood away, and draws the tip of his knife over the bricks. This produces an awful sound, but leaves not a mark. He examines his knife, then puts it away.

"This Wall has no mortar," the Gatekeeper states. "There is no need. The bricks fit perfect; not a hair-space between them. Nobody can put a dent in the Wall. And nobody can climb it. Because this Wall is perfect. So forget any ideas you have. Nobody leaves here."

The Gatekeeper lays a giant hand on my

back.

"You have to endure. If you endure, everything will be fine. No worry, no suffering. It all disappears. Forget about the shadow. This is the End of the World. This is where the world ends. Nowhere further to go."

On my way back to my room, I stop in the middle of the Old Bridge and look at the River. I think about what the Gatekeeper has said.

The End of the World.

Why did I cast off my past to come here to the End of the World? What possible event or meaning or purpose could there have been? Why can I not remember?

Something has summoned me here. Something intractable. And for this, I have forfeited my shadow and my memory.

The River murmurs at my feet. There is the sandbar midstream, and on it the willows sway as they trail their long branches in the current. The water is beautifully clear. I can see fish playing among the rocks. Gazing at the River soothes me.

Steps lead down from the bridge to the sandbar. A bench waits under the willows, a few beasts lay nearby. Often have I descended to the sandbar and offered crusts of bread to the beasts. At first they hesitated, but now the old and the very young eat from my hand.

As the autumn deepens, the fathomless lakes of their eyes assume an ever more sorrowful hue. The leaves turn color, the grasses wither; the beasts sense the advance of a long, hungry season. And bowing to their vision, I too know a sadness.

Dressing, Watermelon, Chaos

The clock read half past nine when she got out of bed, picked up her clothes from the floor, and slowly, leisurely, put them on. I stayed in bed, sprawled out, one elbow bent upright, watching her every move out of the corner of my eye. One piece of clothing at a time, liltingly graceful, not a motion wasted, achingly quiet. She zipped up her skirt, did the buttons of her blouse from the top down, lastly sat down on the bed to pull on her stockings. Then she kissed me on the cheek. Many are the women who can take their clothes off seductively, but women who can charm as they dress? Now completely composed, she ran her hand through her long black hair. All at once, the room breathed new air.

"Thanks for the food," she said.

"My pleasure."

"Do you always cook like that?"

"When I'm not too busy with work," I said. "When things get hectic, it's catch-as-catch-can with leftovers. Or I eat out."

She grabbed a chair in the kitchen and lit up a cigarette. "I don't do much cooking myself.

When I think about getting home after work and fixing a meal that I'm going to polish off in ten minutes anyway, it's so-o depressing."

While I got dressed, she pulled a datebook out of her handbag and scribbled something, which she tore off and handed to me.

"Here's my phone number," she said. "If you have food to spare or want to get together or whatever, give me a call. I'll be right over."

After she left, carrying off the several volumes on mammals to be returned to the library, I went over to the TV and removed the T-shirt.

I reflected upon the unicorn skull. I didn't have an iota of proof, but I couldn't help feeling that this mystery skull was the very same specimen of Voltafil-Leningrad renown. I seemed to sense, somehow, an odor of history drifting about it. True, the story was still fresh in my mind and the power of suggestion was strong. I gave the skull a light tap with the stainless-steel tongs and went into the kitchen.

I washed the dishes, then wiped off the kitchen table. It was time to start. I switched the telephone over to my answering service so I wouldn't be disturbed. I disconnected the door chimes and turned out all the lights except for the kitchen lamp. For the next few hours I needed to concentrate my energies on shuffling.

My shuffling password was "End of the World". This was the title of a profoundly personal drama by which previously laundered numerics would be reordered for computer calculation. Of course, when I say drama, I don't mean the kind they show on TV. This drama was a lot more complex and with no discernible plot. The word is only a label, for convenience sake. All the same, I was in the dark about its contents. The sole thing I knew was its title, End of the World.

The scientists at the System had induced this drama. I had undergone a full year of Calcutec training. After I passed the final exam, they put me on ice for two weeks to conduct comprehensive tests on my brainwaves, from which was extracted the epicenter of encephalographic activity, the "core" of my consciousness. The patterns were transcoded into my shuffling password, then re-input into my brain—this time in reverse.

I was informed that End of the World was the title, which was to be my shuffling password. Thus was my conscious mind completely restructured. First there was the overall chaos of my conscious mind, then inside that, a distinct plum pit of condensed chaos as the center.

They refused to reveal any more than this.

"There is no need for you to know more. The unconscious goes about its business better than you'll ever be able to. After a certain age—our calculations put it at twenty-eight years—human beings rarely experience alterations in the overall configuration of their consciousness. What is commonly referred to as self-improvement or conscious change hardly even scratches the surface. Your 'End of the World' core consciousness will continue to function, unaffected, until you take your last breath. Understand this far?"

"I understand," I said.

"All efforts of reason and analysis are, in a word, like trying to slice through a watermelon with sewing needles. They may leave marks on the outer rind, but the fruity pulp will remain perpetually out of reach. Hence, we separate the rind from the pulp. Of course, there are idle souls out there who seem to enjoy just nibbling away on the rind.

"In view of all contingencies," they went on, "we must protect your password-drama, isolating it from any superficial turbulence, the tides of your outer consciousness.

Suppose we were to say to you, your End of the World is inhered with such, such, and such elements. It would be like peeling away the rind of the watermelon for you. The temptation would be irresistible: you would stick your fingers into the pulp and muck it up. And in no time, the hermetic extractability of our password-drama would be forfeited. Poof! You would no longer be able to shuffle."

"That's why we're giving you back your watermelon with an extra thick rind," one scientist interjected. "You can call up the drama, because it is your own self, after all. But you can never know its contents. It transpires in a sea of chaos into which you submerge empty-handed and from which you resurface empty-handed. Do you follow?"

"I believe so," I said.

"One more point," they intoned in solemn chorus. "Properly speaking, should any individual ever have exact, clear knowledge of his own core consciousness?"

"I wouldn't know," I said.

"Nor would we," said the scientists. "Such questions are, as they say, beyond science."

"Speaking from experience, we cannot conclude otherwise," admitted one. "So in this sense, this is an extremely sensitive experiment."

"Experiment?" I recoiled.

"Yes, experiment," echoed the chorus. "We cannot tell you any more than this."

Then they instructed me on how to shuffle: Do it alone, preferably at night, on neither a full nor empty stomach. Listen to three repetitions of a sound-cue pattern, which calls up the End of the World and plunges consciousness into a sea of chaos. Therein, shuffle the numerical data.

When the shuffling was done, the End of the World call would abort automatically and my consciousness would exit from chaos. I would have no memory of anything.

Reverse shuffling was the literal reverse of this process. For reverse shuffling, I was to listen to a reverse-shuffling sound-cue pattern.

This mechanism was programmed into me. An unconscious tunnel, as it were, input right through the middle of my brain. Nothing more or less.

Understandably, whenever I shuffle, I am rendered utterly defenseless and subject to mood swings.

With laundering, it's different. Laundering is a pain, but I myself can take pride in doing it. All sorts of abilities are brought into the equation. Whereas shuffling is nothing I can pride myself on. I am merely a vessel to be used. My consciousness is borrowed and something is processed while I'm unaware. I hardly feel I can be called a Calcutec when it comes to shuffling. Nor, of course, do I have any say in choice of calc-scheme.

I am licensed in both shuffling and laundering, but can only follow the prescribed order of business. And if I don't like it, well, I can quit the profession.

I have no intention of turning in my Calcutec qualifications. Despite the meddling and the raised eyebrows at the System, I know of no line of work that allows the individual as much freedom to exercise his abilities as being a Calcutec. Plus the pay is good. If I work fifteen years, I will have made enough money to take it easy for the rest of my life.

Shuffling is not impeded by drinking. In fact, the experts indicate that moderate drinking may even help in releasing nervous tension. With me, though, it's part of my ritual that I always shuffle sober. I remain wary about the whole enterprise. Especially since they've put the freeze on shuffling for two months now.

I took a cold shower, did fifteen minutes of hard calisthenics, and drank two cups of black coffee. I opened my private safe, removed a miniature tape recorder and the typewritten paper with the converted data, and set them out on the kitchen table. Then I readied a notepad and a supply of five sharpened pencils.

I inserted the tape, put on headphones, then started the tape rolling. I let the digital tape counter run to 16, then rewound it to 9, then forwarded it to 26. Then I waited with it locked for ten seconds until the counter numbers disappeared and the signal tone began.

Any other order of operation would have caused the sounds on the tape to self-erase.

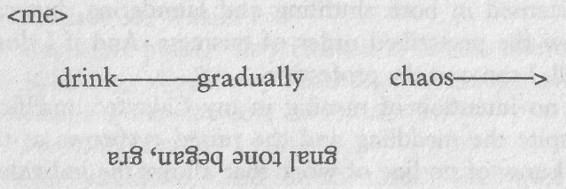

Tape set, brand new notepad at my right hand, converted data at my left. All preparations completed. I switched on the red light to the security devices installed on the apartment door and on all accessible windows. No slip-ups. I reached over to push the PLAY switch on the tape recorder and as the signal tone began, gradually a warm chaos noiselessly drank me in.

A Map of the End of the World

The day after meeting my shadow, I immediately set about making a map of the Town.

At dusk, I go to the top of the Western Hill to get a full perspective. The Hill, however, is not high enough to afford me a panorama, nor is my eyesight as it once was. Hence the effort is not wholly successful. I gain only the most general sense of the Town.

The Town is neither too big nor too small. That is to say, it is not so vast that it eclipses my powers of comprehension, but neither is it so contained that the entire picture can be easily grasped. This, then, is the sum total of what I discern from the summit of the Western Hill: the heights of the Wall encompass the Town, and the River transects it north and south. The evening sky turns the River a leaden hue. Presently the Town resounds with horn and hoof.

In order to determine the route of the Wall, I will ulti-mately need to follow its course on foot. Of course, as I can be outdoors only on dark, overcast days, I must be careful when venturing far from the Western Hill. A stormy sky might suddenly clear or it might let loose a downpour. Each morning, I ask the Colonel to monitor the sky for me. The Colonel's predictions are nearly always right.

"Harbor no fears about the weather" says the old officer with pride. "I know the direction of the clouds. I will not steer you wrong."

Still, there can be unexpected changes in the sky, unaccountable even to the Colonel. A walk is always a risk.

Furthermore, thickets and woods and ravines attend the Wall at many points, rendering it inaccessible. Houses are concentrated along the River as it flows through the center of the Town; a few paces beyond these areas, the paths might stop short or be swallowed in a patch of brambles. I am left with the choice either to forge past these obstacles or to return by the route I had come.

I begin my investigations along the western edge of the Town, that is, from the Gatehouse at the Gate in the west, circling clockwise around the Town. North from the Gate extend fields deep to the waist in wild grain. There are few obstructions on the paths that thread through the grasses. Birds resembling skylarks have built their nests in the fields; they fly up from the weeds to gyre the skies in search of food. Beasts, their heads and backs floating in this sea of grasses, sweep the landscape for edible green buds.

Further along the Wall, toward the south, I encounter the remains of what must once have been army barracks. Plain, unadorned two-story structures in rows of three. Beyond these is a cluster of small houses. Trees stand between the structures, and a low stone wall circumscribes the compound. Everything is deep in weeds. No one is in sight. The fields, it would seem, served as training grounds. I see trenches and a masonry flag stand.

Perhaps the same military men, now retired to the Official Residences where I have my room, were at one time quar-tered in these buildings. I am in a quandary as to the circumstances that warranted their transfer to the Western Hill, thus leaving the barracks to ruin.

Toward the east, the rolling fields come to an end and the Woods begin. They begin gradually, bushes rising in patches amongst intertwining tree trunks, the branches reaching to a height between my shoulders and head. Beneath, the undergrowth is dotted with tiny grassflowers. As the ground slopes, the trees increase in number, variety, and scale. If not for the random twittering of birds, all would be quiet.

As I head up a narrow brush path, the trees grow thick, the high branches coming together to form a forest roof, obscuring my view of the Wall. I take a southbound trail back into Town, cross the Old Bridge, and go home.

So it is that even with the advent of autumn, I can trace only the vaguest outline of the Town.

In the most general terms, the land is laid out east to west, abutted by the North Wood and Southern Hill. The eastern slope of the Southern Hill breaks into crags that extend along the base of the Wall. To the east of the Town spreads a forest, more dark and dense than the North Wood. Few roads penetrate this wilderness, except for a footpath along the river-bank that leads to the East Gate and adjoins sections of the Wall. The East Gate, as the Gatekeeper had said, is cemented in solidly, and none may pass through.

The River rushes down in a torrent from the Eastern Ridge, passes under the Wall, suddenly appears next to the East Gate, and flows due west through the middle of the Town under three bridges: the East Bridge, the Old Bridge, and the West Bridge. The Old Bridge is not only the most ancient but also the largest and most handsome. The West Bridge marks a turning point in the River. It shifts dramatically to the south, flowing back first slightly eastward. At the Southern Hill, the River cuts a deep Gorge.

The River does not exit under the Wall to the south. Rather it forms a Pool at the Wall and is swallowed into some vast cavity beneath the surface. According to the Colonel, beyond the Wall lies a plain of limestone boulders, which stand vigil over countless veins of underground water.

Of course, I continue my dreamreading in the evenings. At six o'clock, I push open the door, have supper with the Librarian, then read old dreams.

In the course of an evening, I read four, perhaps five dreams. My fingers nimbly trace out the labyrinthine seams of light as I grow able to invoke the images and echoes with increasing clarity. I do not understand what dreamreading means, nor by what principle it works, but from the reactions of the Librarian I know that that my efforts are succeeding.

My eyes no longer hurt from the glow of the skulls, and I do not tire so readily.

After I am through reading a skull, the Librarian places it on the counter in line with the skulls previously read that night. The next evening, the counter is empty.

"You are making progress," she says. "The work goes much faster than I expected."

"How many skulls are there?"

"A thousand, perhaps two thousand. Do you wish to see them?"

She leads me into the stacks. It is a huge schoolroom with rows of shelves, each shelf stacked with white beast skulls. It is a graveyard. A chill air of the dead hovers silently.

"How many years will it take me to read all these skulls?"

"You need not read them all," she says. "You need read only as many as you can read.

Those that you do not read, the next Dreamreader will read. The old dreams will sleep."

"And you will assist the next Dreamreader?"

"No, I am here to help you. That is the rule. One assistant for one Dreamreader. When you no longer read, I too must leave the Library."

I do not fully comprehend, but this makes sense. We lean against the wall and gaze at the shelves of white skulls.

"Have you ever been to the Pool in the south?" I ask her.

"Yes, I have. A long time ago. When I was a child, my mother walked with me there.

Most people would not go there, but Mother was different. Why do you ask about the Pool?"

"It intrigues me."

She shakes her head. "It is dangerous. You should stay away. Why would you want to go there?"

"I want to learn everything about this place. If you choose not to guide me, I will go alone."

She stares at me, then exhales deeply.

"Very well. If you will not listen, I must go with you. Please remember, though, I am so afraid of the Pool. There is something malign about it."

"It will be fine," I assure her, "if we are together, and if we are careful."

She shakes her head again. "You have never seen the Pool. You cannot know how frightening it is. The water is cursed. It calls out to people."

"We will not to go too close," I promise, holding her hand. "We will look at it from a distance."

On a dark November afternoon, we set out for the Pool. Dense undergrowth closes in on the road where the River has carved the Gorge in the west slope of the Western Hill. We must change our course to approach from the east, via the far side of the Southern Hill.

The morning rain has left the ground covered with leaves, which dampen our every step.

We pass two beasts, their golden heads swaying as they stride past us, expressionless.

"Winter is near," she explains. "Food is short, and the animals are searching for nuts and berries. Otherwise, they do not go very far from the Town."

We clear the Southern Hill, and there are no more beasts to be seen, nor any road. As we continue west through deserted fields and an abandoned settlement, the sound of the Pool reaches our ears.

It is unearthly, resembling nothing that I know. Different from the thundering of a waterfall, different from the howl of the wind, different from the rumble of a tremor. It may be described as the gasping of a gigantic throat. At times it groans, at times it whines. It breaks off, choking.

"The Pool seems to be snarling," I remark.

She turns to me, disturbed, but says nothing. She parts the overhanging branches with her gloved hands and forges on ahead.

"The path is much worse," she says. "It was not like this. Perhaps we should turn back."

"We have come this far. Let us go as far as we can."

We continue for several minutes over the thicketed moor, guided only by the eerie call of the Pool, when suddenly a vista opens up before us. The wilderness stops and a meadow spreads flat out. The River emerges from the Gorge to the right, then widens as it flows toward where we stand. From the final bend at the edge of the meadow, the water appears to slow and back up, turning a deep sapphire blue, swelling like a snake digesting a small animal. This is the Pool.

We proceed along the River toward the Pool.

"Do not go close," she warns, tugging at my arm. "The surface may seem calm, but below is a whirlpool. The Pool never gives back what it takes."

"How deep is it?"

"I do not know. I have been told the Pool only grows deeper and deeper. The whirlpool is a drill, boring away at the bottom. There was a time when they threw heretics and criminals into it."

"What happened to them?"

"They never came back. Did you hear about the caverns? Beneath the Pool, there are great halls where the lost wander forever in darkness."

The gasps of the Pool resound everywhere, rising like huge clouds of steam. They echo with anguish from the depths.

She finds a piece of wood the size of her palm and throws it into the middle of the Pool.

It floats for a few seconds, then begins to tremble and is pulled below. It does not resurface.

"Do you see?"

We sit in the meadow ten yards from the Pool and eat the bread we have carried in our pockets. The scene is a picture of deceptive repose. The meadow is embroidered in autumn flowers, the trees brilliant with crimson leaves, the Pool a mirror. On its far side are white limestone cliffs, capped by the dark brick heights of the Wall. All is quiet, save for the gasping of the Pool.

"Why must you have this map?" she asks. "Even with a map, you will never leave this Town."

She brushes away the bread crumbs that have fallen on her lap and looks toward the Pool.

"Do you want to leave here?" she asks again.

I shake my head. Do I mean this as a "no", or is it only that I do not know?

"I just want to find out about the Town," I say. "The lay of the land, the history, the people… I want to know who made the rules, what has sway over us. I want even to know what lies beyond."

She slowly rolls her head, then fixes upon my eyes.

"There is no beyond," she says. "Did you not know? We are at the End of the World. We are here forever."

I lie back and gaze up at the sky. Dark and overcast, the only sky I am allowed to see.

The ground beneath me is cold and damp after the morning rain, but the smell of the earth is fresh.

Winter birds take wing from the brambles and fly over the Wall to the south. The clouds sweep in low. Winter readies to lay siege.

Frankfurt, Door, Independent Operants

AS always, consciousness returned to me progressively from the edges of my field of vision. The first things to claim recognition were the bathroom door emerging from the far right and a lamp from the far left, from which my awareness gradually drifted inward like ice flowing together toward the middle of a lake. In the exact center of my visual field was the alarm clock, hands pointing to ten-twenty-six. An alarm clock I received as a memento of somebody's wedding. One of those clever designs. You had to press the red button on the left side of the clock and the black button on the right side simultaneously to stop it from ringing, which was said to preempt the reflex of killing the alarm and falling back to sleep. True, in order to press both left and right buttons simultaneously, I did have to sit upright in bed with the thing in my lap, and by then I had made a step into the waking world.

I repeat myself, I know, but the clock was a thanks-for-coming gift from a wedding.

Whose, I can't remember. But back in my late twenties, there'd been a time when I had a fair number of friends. One year I attended wedding after wedding, whence came this clock. I would never buy a dumb clock like this of my own free will. I happen to be very good at waking up.

As my field of vision came together at the alarm clock, I reflexively picked it up, set it on my lap, and pushed the red and black buttons with my right and left hands. Only then did I realize that it hadn't been ringing to begin with. I hadn't been sleeping, so I hadn't set the alarm.

I put the alarm clock back down and looked around. No noticeable changes in the apartment. Red security-device light still on, empty coffee cup by the edge of the table, the librarian's cigarette lying in a saucer. Marlboro Light, no trace of lipstick. Come to think of it, she hadn't worn any makeup at all.

I ran down my checklist. Of the five pencils in front of me, two were broken, two were worn all the way down, and one was untouched. The notepad was filled with sixteen pages of tiny digits. The middle finger of my right hand tingled, slightly, as it does after a long stint of writing.

Finally, I compared the shuffled data with the laundered data to see that the number of entries under each heading matched, just like the manual recommends, after which I burned the original list in the sink. I put the notepad in a strongbox and transferred it and the tape recorder to the safe. Shuffling accomplished. Then I sat down on the couch, exhausted.

I poured myself two fingers of whiskey, closed my eyes, and drank it in two gulps. The warm feel of alcohol traveled down my throat and spread to every part of my body. I went to the bathroom and brushed my teeth, drank some water, and used the toilet. I returned to the kitchen, resharpened the pencils, and arranged them neatly in a tray. Then I placed the alarm clock by my bed and switched the telephone back to normal. The clock read eleven-fifty-seven. I had a whole day tomorrow ahead of me. I scrambled out of my clothes, dove into bed, and turned off the bedside light. Now for a good twelve-hour sleep, I told myself. Twelve solid hours. Let birds sing, let people go to work.

Somewhere out there, a volcano might blow, Israeli commandos might decimate a Palestinian village. I couldn't stop it. I was going to sleep.

I replayed my usual fantasy of the joys of retirement from Calcutecdom. I'd have plenty of savings, more than enough for an easy life of cello and Greek. Stow the cello in the back of the car and head up to the mountains to practice. Maybe I'd have a mountain retreat, a pretty little cabin where I could read my books, listen to music, watch old movies on video, do some cooking… And it wouldn't be half bad if my longhaired librarian were there with me. I'd cook and she'd eat.

As the menus were unfolding, sleep descended. All at once, as if the sky had fallen. Cello and cabin and cooking now dust to the wind, abandoning me, alone again, asleep like a tuna.

Somebody had drilled a hole in my head and was stuffing it full of something like string.

An awfully long string apparently, because the reel kept unwinding into my head. I was flailing my arms, yanking at it, but try as I might the string kept coming in.

I sat up and ran my hands over my head. But there was no string. No holes either. A bell was ringing. Ringing, ringing, ringing. I grabbed the alarm clock, threw it on my lap, and slapped the red and black buttons with both hands. The ringing didn't stop. The telephone! The clock read four-eighteen. It was dark outside. Four-eighteen a.m.

I got out of bed and picked up the receiver. "Hello?" I said.

No sound came from the other end of the line.

"Hello!" I growled.

Still no answer. No disembodied breathing, no muffled clicks. I fumed and hung up. I grabbed a carton of milk out of the refrigerator and drank whole white gulps before going back to bed.

The phone rang again at four-forty-six.

"Hello," I said.

"Hello," came a woman's voice. "Sorry about the time before. There's a disturbance in the sound field. Sometimes the sound goes away."

"The sound goes away?"

"Yes," she said. "The sound field's slipping. Can you hear me?"

"Loud and clear," I said. It was the granddaughter of that kooky old scientist who'd given me the unicorn skull. The girl in the pink suit.

"Grandfather hasn't come back up. And now, the sound field's starting to break up.Something's gone wrong. No one answers when I call the laboratory. Those INKlings have gotten Grandfather, I just know it."

"Are you sure? Maybe he's gotten all wrapped up in one of his experiments and forgotten to come home. He let you go a whole week sound-removed without noticing, didn't he?"

"It's not like that. Not this time. I can tell. Something's happened to Grandfather. Something is wrong. Anyway, the sound barrier's broken, and the underground sound field's erratic."

"The what's what?"

"The sound barrier, the special audio-signal equipment to keep the INKlings away. They've forced their way through, and we're losing sound. They've got Grandfather for sure!"

"How do you know?"

"They've had their beady little eyes on Grandfather's studies. INKlings. Semiotics. Them. They've been dying to get their hands on his research. They even offered him a deal, but that just made him mad. Please, come quick. You've got to help, please."

I imagined what it would be like coming face to face with an INKling down there. Those creepy subterranean passageways were enough to make my hair stand on end.

"I know you're going to think I'm terrible, but tabulations are my job. Nothing else is in my contract. I've got plenty to worry about as it is. I'd like to help, honest, but fighting INKlings and rescuing your grandfather is a little out of my line. Why don't you call the police or the authorities at the System? They've been trained for this sort of thing."

"I can't call the police. I'd have to tell them everything. If Grandfather's research got out now, it'd be the end of the world."

"The end of the world?"

"Please," she begged. "I need your help. I'm afraid that we'll never get him back. And next they're going to go after you."

"Me? You maybe, but me? I don't know the first thing about your grandfather's research."

"You're the key. Without you the door won't open."

"I have absolutely no idea what you're talking about," I said.

"I can't explain over the phone. Just believe me. This is important. More than anything you've ever done. Really! For your own sake, act while you still can. Before it's too late."

I couldn't believe this was happening to me. "Okay," I gave in, "but while you're at it, you'd better get out of there. It could be dangerous." "Where should I go?"

I gave her directions to an all-night supermarket in Aoyama. "Wait for me at the snack bar. I'll be there by five-thirty."

"I'm scared. Somehow it—"

The sound just died. I shouted into the phone, but there was no reply. Silence floated up from the receiver like smoke from the mouth of a gun. Was the rupture in the sound field spreading? I hung up, stepped into my trousers, threw on a sweatshirt. I did a quick once-over with the shaver, splashed water on my face, combed my hair. My puss was puffy like cheap cheesecake. I wanted sleep. Was that too much to ask? First unicorns, now INKlings—why me?

I threw on a windbreaker, and pocketed my wallet, knife, and loose change. Then, after a moment's thought, I wrapped the unicorn skull in two bath towels, gathered up the fire tongs and the strongbox with the shuffled data, and tossed everything into a Nike sports bag. The apartment was definitely not secure. A pro could break into the place and crack the safe in less time than it takes to wash a sock.

I slipped into my tennis shoes, one of them still dirty, then headed out the door with the bag. There wasn't a soul in the hallway. I decided against the elevator and sidestepped down the stairs. There wasn't a soul in the parking garage either.

It was quiet, too quiet. If they were really after my skull, you'd think they'd have at least one guy staked out. It was almost as if they'd forgotten about me.

I got in the car, set the bag next to me, and started the engine. The time, a little before five. I looked around warily as I pulled out of the garage and headed toward Aoyama.

The streets were deserted, except for taxis and the occasional night-transport truck. I checked the rearview mirror every hundred meters; no sign of anyone tailing me.

Strange how well everything was going. I'd seen every Semiotec trick in the book, and if they were up to something, they weren't subtle about it. They wouldn't hire some bungling gas inspector, they wouldn't forget a lookout. They chose the fastest, most surefire methods, and executed them without mercy. A couple of years ago, they captured five Cal-cutecs and trimmed off the tops of their crania with one buzz of a power saw.

Five Calcutec bodies were found floating in Tokyo Bay minus their skullcaps. When the Semiotecs meant business, they did business. Something didn't make sense here.

I pulled into the Aoyama supermarket parking garage at five-twenty-eight. The sky to the east was getting light. I entered the store carrying my bag. Almost no one was in the place. A young clerk in a striped uniform sat reading a maga-zine; a woman of indeterminate age was buying a cartload of cans and instant food. I turned past the liquor display and went straight to the snack bar.

There were a dozen stools, and she wasn't on any of them. I took a seat on one end and ordered a sandwich and a glass of milk. The milk was so cold I could hardly taste it, the sandwich a soggy ready-made wrapped in plastic. I chewed the sandwich slowly, measuring my sips to make the milk last.

I eyed a poster of Frankfurt on the wall. The season was autumn, the trees along the river blazing with color. An old man in a pointed cap was feeding the swans. A great old stone bridge was on one side, and in the background, the spire of a cathedral. People sat on benches, everyone wore coats, the women had scarves on their heads. A pretty postcard picture. But it gave me the chills. Not because of the cold autumn scene. I always get the chills when I see tall, sharp spires.

I turned my gaze to the poster on the opposite wall. A shiny-faced young man holding a filter-tip was staring obliquely into the distance. Uncanny how models in cigarette ads always have that not-watching-anything, not-thinking-anything look in their eyes.

At six o'clock, the chubby girl still hadn't shown. Unaccountable, especially since this was supposed to be so urgent. I was here; where was she?

I ordered a coffee. I drank it black, slowly.

The supermarket customers gradually increased. Housewives buying the breakfast bread and milk, university students hungry after a long night out, a young woman squeezing a roll of toilet paper, a businessman snapping up three different newspapers, two middle-aged men lugging their golf clubs in to purchase a bottle of whiskey. I love supermarkets.

I waited until half past six. I went out to the car and drove to Shinjuku Station. I walked to the baggage-check counter and asked to leave my Nike sports bag. Fragile, I told the clerk. He attached a red handle with care tag with a cocktail glass printed on it. I watched as he placed the bag on the shelf. He handed me the claim ticket.

I went to a station kiosk. For two hundred sixty yen, I bought an envelope and stamps. I put the claim ticket into the envelope, sealed it, stamped it, and addressed it to a p.o. box I'd been keeping under a fictitious company name. I scribbled express on it and dropped the goods into the post.

Then I got in the car and went home. I showered and tumbled into bed.

At eleven o'clock, I had visitors. Considering the sequence of events, it was about time.

Still, you'd think they could have rung the bell before trying to break the door down. No, they had to come in like an iron wrecking ball, making the floor shake. They could have saved themselves the trouble and wrangled the key out of the superintendent. They could also have saved me a mean repair bill.

While my visitors were rearranging the door, I got dressed and slipped my knife into my pocket. Then, to be on the prudent side, I opened the safe and pushed the erase button on the tape recorder. Next, I got potato salad and a beer from the refrigerator for lunch. I thought about escaping via the emergency rope ladder on the balcony, but why bother?

Running away wouldn't solve anything. Solve what? I didn't even know what the problem was. I needed a reality check.

Nothing but question marks. I finished my potato salad, I finished my beer, and just as I was about to burp, the steel door blew wide open and banged flat down.

Enter one mountain of a man, wearing a loud aloha shirt, khaki army-surplus pants stained with grease, and white tennis shoes the size of scuba-diving flippers. Skinhead, pug snout, a neck as thick as my waist. His eyelids formed gun-metal shells over eyes that bulged molten white. False eyes, I thought immediately, until a flicker of the pupils made them seem human. He must have stood two meters tall, with shoulders so broad that the buttons on his aloha shirt were practically flying off his chest.

The hulk glanced at the wasted door as casually as he might a popped wine cork, then turned his attentions toward me. No complex feelings here. He looked at me like I was another fixture. Would that I were.

He stepped to one side, and behind him there appeared a rather tiny guy. This guy came in at under a meter and a half, a slim, trim figure. He had on a light blue Lacoste shirt, beige chinos, and brown loafers. Had he bought the whole outfit at a nouveau riche children's haberdashery? A gold Rolex gleamed on his wrist, a normal adult model—guess they didn't make kiddie Rolexes—so it looked disproportionately big, like a communicator from Star Trek. I figured him for his late thirties, early forties.

The hulk didn't bother removing his shoes before trudging into the kitchen and swinging around to pull out the chair opposite me. Junior followed presently and quietly took the seat. Big Boy parked his weight on the edge of the sink. He crossed his arms, as thick as normal human thighs, his eyes trained on a point just above my kidneys. I should have escaped while I could have.

Junior barely acknowledged me. He pulled out a pack of cigarettes and a lighter, and placed them on the table. Benson & Hedges and a gold Dupont. If Junior's accoutrements were any indication, the trade imbalance had to have been fabricated by foreign governments. He twirled the lighter between his fingers. Never a dull moment.

I looked around for the Budweiser ashtray I'd gotten from the liquor store, wiped it with my fingers, and set it out in front of the guy. He lit up with a clipped flick, narrowed his eyes, and released a puff of smoke.

Junior didn't say a word, choosing instead to contemplate the lit end of his cigarette. This was where tht Jean-Luc Godard scene would have been titled 1/ regardait le feu de son tabac. My luck that Godard films were no longer fashionable. When the tip of Junior's cigarette had transformed into a goodly increment of ash, he gave it a measured tap, and the ash fell on the table. For him, an ashtray was extraneous,

"About the door," began Junior, in a high, piercing voice. "It was necessary to break it. That's why we broke it. We could have opened it more gentleman-like if we wanted to. But it wasn't necessary. I hope you don't think bad of us."

"There's nothing in the apartment," I said. "Search it, you'll see."

"Search?" pipped the little man. "Search?" Cigarette at his lips, he scratched his palm.

"And what might we be searching for?"

"Well, I don't know, but you must've come here looking for something. Breaking the door down and all."

"Can't say I capisce," he spoke, measuredly. "Surely you must be mistaken. We don't want nothing. We just came for a little chat. That's all. Not looking and not taking. However, if you would care to offer me a Coca-Cola, I'd be happy to oblige."

I fished two cans of Coke from the refrigerator, which I set out on the table along with a couple of glasses.

"I don't suppose he'd drink something, too?" I said, pointing to the hulk behind me.

Junior curled his index finger and Big Boy tiptoed forward to claim a can of Coke. He was amazingly agile for his frame.

"After you're finished drinking, give him your free demonstration," Junior said to Big Boy. "It's a little side show," he said to me.

I turned around to watch the hulk chug the entire can in one go. Then, after upending it to show that it was empty, he pressed the can between his palms. Not the slightest change came over his face as the familiar red can was crushed into a pathetic scrap of metal.

"A little trick, anybody could do," said Junior.

Next, Big Boy held the flattened aluminum toy up with his fingertips. Effortlessly, though a faint shadow now twitched on his lip, he tore the metal into shreds. Some trick.

"He can bend hundred-yen coins, too. Not so many humans alive can do that," said Junior with authority.

I nodded in agreement.

"Ears, he rips 'em right off."

I nodded in agreement.

"Up until three years ago, he was a pro wrestler," Junior explained. "Wasn't a bad wrestler. He was young and fast. Championship material. But you know what he did? He went and injured his knee. And in pro wrestling, you gotta be able to move fast."

I nodded a third agreement.

"Since his untimely injury, I've been looking after him. He's my cousin, you know."

"Average body types don't run in your family?" I queried.

"Care to say that again?" said Junior, glaring at me.

"Just chatting," I said.

Junior collected his thoughts for the next few moments. Then he flicked his cigarette to the floor and ground it out under his shoe. I decided no comment.

"You really oughta relax more. Open up, take things easy. If you don't relax, how're we have gonna have our nice heart-to-heart?" said Junior. "You're still too tense."

"May I get a beer?"

"Certainly. Of course. It's your beer—in your refrigerator—in your apartment. Isn't it?"

"It was my door, too," I added.

"Forget about the door. You keep thinking so much, no wonder you're tense. It was a tacky cheapo door anyway. You make good money, you oughta move someplace with classier doors."

I got my beer.

Junior poured Coke in his glass and waited for the foam to go down before drinking.

Then he spoke. "Forgive the complications. But I wanna explain some things first. We've come to help you."

"By breaking down my door?"

The little man's face turned instantly red. His nostrils flared.

"There you go with that door again. Didn't I tell you to drop it?" he bit his words. Then he turned to Big Boy and repeated the question. "Didn't I?"

The hulk nodded his agreement.

"We're here on a goodwill mission," Junior went on. "You're lost, so we came to give you moral guidance. Well, perhaps lost is not such a nice thing to say. How about confused? Is that better?"

"Lost? Confused?" I said. "I don't have a clue. No idea, no door."

Junior grabbed his gold lighter and threw it hard against the refrigerator, making a dent.

Big Boy picked the lighter off the floor and returned it to its owner. Everything was back to where we were before, except for the dent. Junior drank the rest of his Coke to calm down.

"What's one, two lousy doors? Consider the gravity of the situation. We could service this apartment in no time flat. Let's not hear another word about that door."

My door. It didn't matter how cheap it was. That wasn't the issue. The door stood for something.

"All right, forget about the door," I said. "This commotion could get me thrown out of the building."

"If anyone says anything to you, just give me a call. We got an outreach program that'll make believers out of them. Relax."

I shut up and drank my beer.

"And a free piece of advice," Junior offered. "Anybody over thirty-five really oughta kick the beer habit. Beer's for college students or people doing physical labor. Gives you a paunch. No class at all."

Great advice. I drank my beer.

"But who am I to tell you what to do?" Junior went on. "Everybody has his weak points.

With me, it's smoking and sweets. Especially sweets. Bad for the teeth, leads to diabetes."

He lit another cigarette, and glanced at the dial of his Rolex.

"Well then," Junior cleared his throat. "There's not much time, so let's cut the socializing out. Relaxed a bit?"

"A bit," I said.

"Good. On to the subject at hand," said Junior. "Like I was saying, our purpose in coming here was to help you unravel your confusion. Anything you don't know? Go ahead and ask." Junior made a c'mon-anything-at-all gesture with his hand.

"Okay, just who are you guys?" I had to open my big mouth. "Why are you here? What do you know about what's going on?"

"Smart questions," Junior said, looking over to Big Boy for a show of agreement. "You're pretty sharp. You don't waste words, you get right to the point."

Junior tapped his cigarette into the ashtray. Kind of him.

"Think about it this way. We're here to help you. For the time being, what do you care which organization we belong to. We know lots. We know about the Professor, about the skull, about the shuffled data, about almost everything. We know things you don't know too. Next question?"

"Fine. Did you pay off a gas inspector to steal the skull?"

"Didn't I just tell you?" said the little man. "We don't want the skull, we don't want nothing."

"Well, who did? Who bought off the gas inspector?"

"That's one of the things we don't know," said Junior. "Why don't you tell us?"

"You think I know?" I said. "All I know is I don't need the grief."

"We figured that. You don't know nothing. You're being used."

"So why come here?"

"Like I said, a goodwill courtesy call," said Junior, banging his lighter on the table.

"Thought we'd introduce ourselves. Maybe get together, share a few ideas. Your turn now. What do you think's going on?"

"You want me to speculate?"

"Go right ahead. Let yourself go, free as a bird, vast as the sea. Nobody's gonna stop you."

"All right, I think you guys aren't from either the System or the Factory. You've got a different angle on things. I think you're independent operants, looking to expand your turf. Eyeing Factory territory."

"See?" Junior remarked to his giant cousin. "Didn't I tell you? The man's sharp."

Big Boy nodded.

"Amazingly sharp for someone living in a dump like this. Amazingly sharp for someone whose wife ran out on him."

It had been ages since anyone praised me so highly. I blushed.

"You speculate good," Junior said. "We're going to get our hands on the Professor's research and make a name for us. We got these infowars all figured out. We done our homework. We got the backing. We're ready to move in. We just need a few bits and pieces. That's the nice thing about infowars. Very democratic. Track record counts for nothing. It's survival of the sharpest. Survival in a big way. I mean, who's to say we can't cut the pie? Is Japan a total monopoly state or what? The System monopolizes everything under the info sun, the Factory monopolizes everything in the shadows. They don't know the meaning of competition. What ever happened to free enterprise? Is this unfair or what? All we need is the Professor's research, and you."

"Why me?" I said. "I'm just a terminal worker ant. I don't think about anything but my own work. So if you're thinking of enlisting me—"

"You don't seem to get the picture," said Junior, with a click of his tongue. "We don't wanna enlist you. We just wanna get our hands on you. Next question?"

"Oh, I see," I said. "How about telling me something about the INKlings then."

"INKlings? A sharp guy like you don't know about INKlings? A.k.a. Infra-Nocturnal Kappa. You thought kappa were folktales? They live underground. They hole up in the subways and sewers, eat the city's garbage, and drink gray-water. They don't bother with human beings. Except for a few subway workmen who disappear, that is, heh heh."

"Doesn't the government know about them?"

"Sure, the government knows. The state's not that dumb."

"Then why don't they warn people? Or else drive the INKlings away?"

"First of all," he said, "it'd upset too many people. Wouldn't want that to happen, would you? INKlings swarming right under their feet, people wouldn't like that. Second, forget about exterminating them. What are you gonna do? Send the whole Japanese Self-Defense Force down into the sewers of Tokyo? The swamp down there in the dark is their stomping grounds. It wouldn't be a pretty picture."

"Another thing, the INKlings have set up shop not too far from the Imperial Palace. It's a strategic move, you understand. Any trouble and they crawl up at night and drag people under. Japan would be upside-down, heh. Am I right? That's why the government doesn't mind INKlings and INKlings doesn't mind the government."

"But I thought the Semiotecs had made friends with the INKlings," I broke in.

"A rumor. And even if it was true, it'd only mean one group of INKlings got sweet on the Semiotecs. A temporary engagement, not a lasting marriage. Nothing to worry about."

"But haven't the INKlings kidnapped the Professor?"

"We heard that too. But we don't know for sure. Could be the Professor staged it."

"Why would the Professor do that?"

"The Professor answers to nobody," Junior said, sizing up his lighter from various angles.

"He's the best and he knows it. The Semiotecs know it, the Calcutecs know it. He just plays the in-betweens. That way he can push on, doing what he pleases with his research. One of these days he's gonna break through. That's where you fit in."

"Why would he need me? I don't have any special skills. I'm a perfectly ordinary guy."

"We're trying to figure that one out for ourselves," Junior) admitted, flipping the lighter around in his hands. "We got some ideas. Nothing definite. Anyway, he's been studymgall about you. He's been preparing something for a long time now."

"Oh yeah? So you're waiting for him to put the last piece in place, and then you'll have me and the research."

"On the money," said Junior. "We got some strange weather blowing up. The Factory has sniffed something in the wind and made a move. So we gotta make moves, too."

"What about the System?"

"No, they're slow on the take. But give 'em time. They know the Professor real well."

"What do you mean?"

"The Professor used to work for the System."

"The System?"

"Right, the Professor is an ex-colleague of yours. Of course, he wasn't doing your kind of work. He was in Central Research."

"Central Research?" This was getting too complicated to follow. I was standing in the middle of it all, only I couldn't see a thing.

"This System of yours is big, too big. The right hand never knows what the left hand is doing. Too much information, more than you can keep track of. And the Semiotecs are just as bad. That's why the Professor quit the organization and went out on his own. He's a brain man. He's into psychology and all kinds of other stuff about the head. He's what you call a Renaissance Man. What does he need the System for?"

And I had explained laundering and shuffling to this man? He'd invented the tech! What a joke I was.

"Most of the Calcutec compu-systems around are his design. That's no exaggeration. You're like a worker bee stuffed full of the old man's honey," pronounced the little man.

"Not a very nice metaphor, maybe."

"Don't mind me," I said.

"The minute the Professor quit, who should come knock-ing on his door but scouts from the Factory. But the Professor said no go. He said he had his own windows to wash, which lost him a lotta admirers. He knew too much for the Cal-cutecs, and the Semiotecs had him pegged for a round hole. Anyone who's not for you is against you, right? So when he built his laboratory underground next to the INKlings, it was the Professor against everybody. You been there, I believe?"

I nodded.

"Real nuts but brilliant. Nobody can get near that laboratory. The whole place is crawling with INKlings. The Professor comes and goes. He puts out sound waves to scare the INKlings. Perfect defense. That girl of his and you are the only people who's ever been inside. Goes to show how important you are. So we figure, the Professor's about to throw you in the box and tie things up."

I grunted. This was getting weird. Even if I believed him, I wouldn't believe it.

"Are you telling me that all the experiment data I processed for the Professor was just so he could lure me in?"

"No-o, not at all," said the little man. He cast another quick glance at his watch. "The data was a program. A time bomb. Time comes and— booom! Of course, this is just our guess. Only your Professor knows for sure. Well, I see time's running out, so I think we cut short our little chit-chat. We got ourselves a little appointment after this."

"Wait a second, what's happened to the Professor's granddaughter?"

"Something happened to the kid?" Junior asked innocently. "We don't know nothing about it. Can't watch out for everybody, you know. Had something for the little sweetheart, did you?"

"No," I said. Well, probably not.

Junior stood up from his chair without taking his eyes off me, swept up his lighter and cigarettes from the table and slipped them into his pocket. "I believe it was nice getting to know you. But let me back up and tell you a secret. Right now, we're one step ahead of the Semiotecs. Still, we're small, so if they decide to get their tails in gear, we get crushed; We need to keep them occupied. Capisce?" "I suppose," I said.

"Now if you were in our position, what do you think'd keep them nice and occupied?"

"The System?" was my guess.

"See?" Junior again remarked to Big Boy. "Sharp and to the point. Didn't I tell you?"

Then he looked back at me. "But for that, we need bait. No bait, no bite."

"I don't really feel up to that sort of thing," I said quickly. "We're not asking you how you feel," he said. "We're in a bit of a hurry. So now it's our turn for one little question. In this apartment, what things do you value the most?"

"There's nothing here," I said. "Nothing of any value. It's all cheap stuff."

"We know that. But there's gotta be something, some trinket you don't wanna see destroyed. Cheap or not, it's your life here, eh?"

"Destroyed?" I said. "What do you mean, destroyed?"

"Destroyed, you know… destroyed. Like with the door," said the little man, pointing to the thing lying blown off its twisted hinges. "Destruction."

"What for?"

"Destruction for the sake of destruction. You want an explanation? Why don't you just tell us what you don't want to see destroyed. We want to show them the proper respect."

"Well, the videodeck," I said, giving in. "And the TV. They're kind of expensive and I just bought them. Then there's my collection of whiskeys."

"Anything else?"

"My new suit and my leather jacket. It's a U.S. Air Force bomber jacket with a fur collar."

"Anything else?"

"That's all," I said.

The little man nodded. The big man nodded. Immediately, Big Boy went around opening all the cupboards and closets. He found the Bullworker I sometimes use for exercising, and swung it around behind him to do a full back-press. Very impressive.

He then gripped the shaft like a baseball bat. I leaned forward to see what he was up to.

He went over to the TV, raised the Bullworker, and took a full swing at the picture tube.

Krrblam! Glass shattered everywhere, accompanied by a hundred short sputtering flashes.

"Hey!…" I shouted, clamoring to my feet before Junior slapped his palm flat on the table to silence me.

Next Big Boy lifted the videodeck and pounded it over and over again on a corner of the former TV. Switches went flying, the cord shorted, and a cloud of white smoke rose up into the air like a saved soul. Once the videodeck was good and destroyed, Big Boy tossed the carcass to the floor and pulled a switchblade from his pocket. The blade sprang open. Now he was going through my wardrobe and retailoring close to two-hundred-thousand-yen worth of bomber jacket and Brooks Brothers suit.

"But you said you were going to leave my valuables alone," I cried.

"I never said that. I said we were gonna show them the proper respect. We always start with the best. Our little policy."

Big Boy was bringing new meaning to the word destruction in my cozy, tasteful apartment. I pulled another can of beer out of the refrigerator and sat back to watch the fireworks.