Chapter 10

We worked eleven hours a day. Forget everything you have seen in war movies where the men swan around in cricket sweaters, doing a bit of gardening or gym to cover their escape tunnels, smoking pipes and teasing the Germans. It may have been like that in the officers’ camps but for us, the ‘other ranks’, it was hard, physical work, though it was not nearly as hard for us as for the stripeys.

Each day I saw Jews being killed on the factory site. Some were kicked and beaten to death, others simply collapsed and died in the dirt of exhaustion and hunger. I knew the same was happening in every corner of the camp, in every work detail. These Jews might be able to prolong their lives a little but the outcome was likely to be the same. They weren’t fed enough to survive. Around midday the dreadful cabbage soup arrived. We could barely stomach it, though ours offered some nutrition while the stuff the Jewish prisoners had was little more than stinking water. From time to time we managed to exaggerate the numbers on our work Kommando to get more soup than we needed. We couldn’t give it directly to the Jews but we left it standing around where they could get to it. If the guards or the Kapos saw them eating our soup they kicked it over to stop them. There was usually a beating.

At the Buna-Werke they sucked the life and labour from each exhausted man and when he was spent, he was sent to be killed. I did not know the names then but they went west, either to the original brick-built camp, Auschwitz One, or the vast new wooden sprawl of Auschwitz-Birkenau. There they would be killed sooner rather than later, many immediately on arrival. Behind it all stood the SS and the executives of IG Farben itself. The Kapos, the prisoners put in charge of their fellows, became the focus of my anger. They were evil men and many wore the green triangle of the career criminal. Their survival depended on keeping the rest of the prisoners in line. If they lost their privileged job they were friendless and then they didn’t live long.

People talk about man’s inhumanity to man, but that wasn’t human or inhuman – it was bestial. Love and hate meant nothing there. It was indifference. I felt degraded by each mindless murder I witnessed and could do nothing about. I was living in obscenity.

For the Jewish prisoners anything that could be traded or swallowed had value. It might offer them the chance to live a bit longer. They all had to find a niche, a way of securing a few extra calories a day, or they died. The risks for them were enormous.

We were privileged in comparison, but only in comparison. We argued for the occasional Sunday off and there was a slight easement in our conditions. Not before I got into an unexpected row with one of the senior contractors on the IG Farben site.

A little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. A little knowledge of a language in a place like Auschwitz could be deadly. I had accused one of the managers on site of being a ‘Schwindler’ to his face for making us work seven days a week without a break. He went berserk. I knew I had misjudged the word when the guards were called to take me away.

In the end a translator was called in to mediate, a Scottish soldier with better German than mine. He argued that in English to call someone a ‘swindler’ was a mild criticism, like calling him a rogue. Clearly in German it was much worse. Actually ‘Schwindler’ was mild compared to what I really thought but that plea took the heat out of the row and calmed things down. I had been lucky again.

It was generally hard graft and we were angry that our forced labour could help the German war effort. We complained that the work was in breach of the Geneva Convention. To my surprise the complaint was passed on and we were summoned to an office building on the IG Farben site. I was one of five lads chosen to go and make the case. I was amazed they were prepared to listen at all but when we were ushered into the office and saw that a senior officer was going to preside over the meeting I knew that it didn’t bode well.

He listened to the complaint then he took his Luger pistol from his holster, slammed it on the table and said. ‘That’s my Geneva Convention. You will do what I say.’ We were sent back to work but we were determined to do whatever we could to hinder what was going on.

I was often ordered to make deliveries to the office of one German engineer. He wore a trilby hat and high boots or gaiters when he was out on the site but he was chatty and seemed to like me. We had some plans to subvert the work the Germans were making us do and that connection made the subterfuge easier. That’s where I got to know Paulina, a young Ukrainian who worked there. After Germany attacked the Soviet Union she and many other Ukrainian women had been transported across Europe and press-ganged to work for the Nazis. They had more freedom than the Jewish prisoners. They didn’t wear striped uniforms and they were not there to be exterminated but life was still precarious for them. They had to have courage to help us and Paulina helped us a lot. She came from somewhere on the Black Sea, she was young, had a broad face and wavy blond hair. She tipped us off when special shipments of machinery or components were expected to come in so that we could try and arrange some sort of sabotage.

When it was too tricky to meet in the engineer’s office we’d tie up in a small boiler house. The boiler man was a forced labourer and I’d warn him in advance. He knew what was going on but he teased us anyway, linking his fingers together whilst whispering the words ‘amour, amour’ suggestively.

He had unscrewed a sheet of corrugated iron from the structure behind the boiler so that if the SS came into the shed when we were talking one of us could escape out the back of the building. I never had to.

The information Paulina gave us was vital. We swapped labels on railway trucks hoping they would go to the wrong places. We slipped sand into axle-bearings so they would run hot and wear out. We twisted the blades on cooling fans so that they would vibrate and gradually damage the machinery. We even laid sharp stones under electrical cables in trenches in the hope they would eventually sever the supply. When we were directed to rivet the huge gasometers, we developed a way of peening the rivet head so it looked neatly finished but would work loose in time and cause a leak. I would sneak into the contractors’ yards, find the bottles of oxygen for oxyacetylene welding and use a removable key I had made to open the valves and release the gas. Acetylene could be smelt; oxygen couldn’t. It was the perfect crime. My engineering expertise came in handy for the first time since the desert. I was glad to be of use.

Paulina did more for me than supply information. She managed to get me cooked food to eat on a couple of occasions, better still, she gave it to me on a plate. I don’t know where it came from but I appreciated it. She liked me, that’s as far as it went. There was nothing between us but when she gave me her photograph I kept it safe all the same. I carried it in my uniform and I brought it home with me. I still have it today. She also gave me a simple signet ring with the mysterious initials FD inscribed on it and the date 1943. Even casual gifts were rare in that place and had a human value so I carried that all the way home too.

Much of the sabotage we pulled off wouldn’t have happened without her. They were all slow-burn projects. They had to be. Anything dramatic would be detected and someone would pay for it. It was too risky.

The ground for the buna rubber plant had been broken in April 1941. Heinrich Himmler, the Reichsführer-SS, had promised IG Farben thousands of slave labourers to build it. Not a single batch of buna rubber was ever produced in that plant and I’d like to think we played our part.

The inhumanity was all around. One day I was looking towards the canteen buildings on the IG Farben site when I saw a Jewish prisoner rummaging in a dustbin for something to eat or trade, some mouldy greens perhaps or a cigarette butt or a piece of wire. He was moving slowly. Hunger and exhaustion had blunted his senses to everything other than the need to eat or die.

There was no time to warn him. He didn’t see the female guard in uniform, one of very few on the site, until she was right behind him. She knocked him to the floor with a single blow and stood astride him. It didn’t take much. She picked up a large rock in her leather-gloved hands, raised it above her head and smashed his skull with it.

She wasn’t the only female guard I saw. Someone pointed out a woman in a well-cut uniform in a party walking through the site. Her hard expression disfigured a youthful face. They told me she was Irma Grese, the notorious guard from the Birkenau extermination camp on the other side of the town. Her sadistic acts led to her execution in December 1945.

Some of the SS guards were old or had been injured in combat but I had no sympathy for any of them. They were not the Afrika Korps. They could see what was happening in Auschwitz. There was no hiding it.

On one occasion an SS man came up to me as I was working outside. He had deeply sunken eyes and a combat injury to his arm. He stood by my shoulder and, staring straight ahead, he began to talk as if to himself. He had been a machine gunner on the eastern front and he described a Russian attack that began with the blow of a whistle. There were thousands of them, he said, and no matter how many he mowed down they kept coming. He was reliving it by my side. The barrel of his machine gun soon warped with the heat of endless firing. It was useless. They were unstoppable. He was wounded and perhaps part of his mind had gone. I said nothing. How could anyone sympathise in that place?

At the end of his monologue, he picked himself up and walked off without as much as a goodbye. I saw him again three days later. He looked right through me.

I remember holding the metal pipes so that a blond, fresh-faced twenty-year-old could weld flanges onto them. He was a German civilian worker. These workers were a mystery to us but he intrigued me. I tried to appeal to him as a young man, quizzed him about music, and why the Nazis hated jazz. I thought if I caught him off guard he might speak about his past, reveal something useful. He was already poisoned by hatred. He said the Jews had destroyed his country. There was no meeting of minds but suddenly he stopped welding and sang.

‘Küss mich, bitte bitte küss mich,

Eh’ die letzte Bahn kommt,

Küss mich ohne Pause’

(‘Kiss me, please, please kiss me,

till the last tram comes,

Kiss me without stopping’)

If those innocent lyrics were at odds with that monstrous place he didn’t notice. He went back to his welding.

Another prisoner stood out for me amongst the wise and the accomplished brought down by the Nazis. His name was Victor Perez, a Sephardic Jew born in French Tunisia. In his day he had been a world champion flyweight boxer but he had been arrested in Paris in 1943. As a boy keen on the sport I knew him as ‘Young’ Perez who had come and fought in Britain in the early 1930s. I talked to him just once inside IG Farben and then very briefly. When I told him I knew of his big fight against Johnny King in Manchester he had to stop and think before he could remember. He was a shadow of the handsome young fighter whose photos I had seen. Years later I learnt he had been forced to box on the Appelplatz – the Auschwitz III parade ground – whilst the SS laid bets on the outcome. He was shot by the SS in January 1945.

Our little acts of sabotage weren’t enough for me. The ground we trod on had absorbed much blood. That terrible stench still hung across the camp and mixed with the filth and fumes in the air. The questions were building up.

I thought I had become inured to the brutality of the place. I had to be just to survive. Everyone caught up in Auschwitz had a story, a history, but the scale of it meant each person’s personal tragedy was lost in the mass of it. Then, when I least expected it, two individuals stepped out of the crowd. The collective suffering of thousands became the fate of real people once again. So it was with Hans and Ernst, the two Jewish prisoners who got to me for very different reasons.

I met Hans whilst working on the first floor of a brick building that was slowly taking shape. It was still open to the sky but they had begun installing heavy piping along a corridor. I was out of sight in that passageway but the layout meant I could be easily surprised if a guard came prowling.

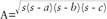

What was I doing? I was scribbling a mathematical formula in chalk on one of the large pipes lined-up waiting to be connected. I was oblivious to my surroundings. It was an idle act but I was trying to salvage something of my pre-war self, the certainties I had known. What I was wrestling to remember was a cumbersome method for calculating the area of a triangle: Heron’s formula.

There I was chalk in hand in a half-finished passageway close to the epicentre of the Nazi killing machine, staring at the chalky letters and symbols on a pipe.

Hans saw I was alone and took his chance. He came straight up and asked me if I had a cigarette. Then he caught sight of my mathematical scrawl. When he spoke it was in German. All he said was ‘I know what that is.’ (‘Ich weiss was das ist.’) The daily jostle for food and survival was momentarily forgotten. The two of us stopped and stared at that strange formula and for a few heartbeats it felt like we were communing with the centuries of human wisdom and ingenuity, the world of decency and learning that had been swept away.

Hans was a Dutch Jew with high cheekbones and a thin face. He was an educated chap, I recognised that the moment I met him. I found out later that his family had run a department store, or something like it, in Amsterdam before the war. I never knew much more about him than that. I’m not even sure Hans was his real name but it was what I called him. Knowing names was dangerous. If they interrogated you that was it, they’d get it out of you somehow and someone would be for the bullet. If I identified myself at all I called myself Ginger.

When my focus returned I realised he was in danger and I shooed him away. If he was seen talking to me he would be for it. He was gone in an instant but those brief moments had made a deep impression on me and I looked out for him from then on.

That meeting with Hans was to be the beginning of the most foolhardy venture I have ever been involved in but first I had troubles of my own to resolve because soon after Hans left, a guard stumbled across the chalked letters. He summoned help. A uniformed delegation appeared and stood around in baffled silence contemplating the mysterious symbols on the pipe. Then the inevitable happened. I was taken to a small glass box of an office on the ground floor for questioning.

There were only two SS officers present and they were convinced my scribble was a secret coded message of some sort, but what did it mean and who was it for?

‘It’s not a code it’s a formula,’ I said. ‘It’s a bit like Pythagoras’ Theorem … only different.’ I knew this was going to be hard to explain. They looked unconvinced. ‘It’s to do with triangles,’ I said, ‘calculating the area of triangles.’ There I was, trying to explain Heron and Pythagoras to the SS. With their broken English and my basic German we weren’t getting very far. My actions didn’t make any sense to them. The truth was it was just one of those weird things I do.

It was a cold day when I met the second of the prisoners who left an indelible mark on my life. My back was aching with the strain of hauling loads of pipes across the site to have flanges welded onto them. The three-storey filtration plant was practically finished. Now the bigger job of installing the equipment inside was underway.

I never really smoked in those days but cigarettes were the only universal currency in Auschwitz. You could almost buy a man’s life with them. They had other uses too.

A number of senior German engineers overseeing the project arrived to review progress. They walked about, rolling and unrolling their plans and taking notes then standing around looking important and talking to each other.

I did what I always did when they were around. I got as close as I could and lit a cigarette with the sole purpose of blowing the smoke in their faces. They didn’t appreciate it much. The other lads followed suit. We had to do it subtly. Too aggressive or obvious about it and there could be trouble, but they got the message.

Smoking was also a way to get cigarettes to the Jewish prisoners without attracting attention. I hated them having to scramble in the dirt for them when I threw the butts away but it was better than doing nothing. Even a cigarette end could be bartered.

I emerged from the filtration plant, leaving the sound of hammering and bright flashes from the welders’ torches behind. I noticed straight away that a young Jewish prisoner had his eye on me. I guessed he was probably waiting to see if I would drop a cigarette. His head was shaved like the others but there was something special about him. He had more expression in his face. He didn’t look like a corpse but I knew he soon would. They all did eventually. I remember the transports of Hungarian Jews arriving. They were big strapping fellers some of them. Within four months they were skin and bone and many of them were already dead.

This lad was around nineteen and somehow different. I noticed straight away that his zebra uniform was thicker than most, not quite so worn out, maybe even cleaner than the others. It made me cautious at first. Perhaps he was one of the favoured few, the Prominente, who had found questionable ways of rising up the camp hierarchy. It didn’t seem likely but I couldn’t be sure.

‘What’s your name?’ I asked.

‘Ernst,’ he replied. ‘What is yours?’

Somehow his manner overcame my caution. There was something likeable about him.

‘Call me Ginger,’ I said. I think I gave him a cigarette and then we parted. That was it.

It was a few days before I saw him again. We didn’t look at each other, that was too dangerous in the open, so we talked as we walked. He was struggling with his English but as soon as I understood what he was trying to tell me it changed everything. He said something like, ‘Me sister in England …’

These simple words stopped me in my tracks. Had I understood him correctly? He had a sister in England? I was astonished. I looked at him. He was tired but he wasn’t as drawn-looking as the others. He explained in a mixture of English and German that his sister had managed to escape to Britain in 1939, one of the last to leave Germany. Her name was Susanne, he said and she had made it to Birmingham. Just hearing the name of a familiar British city on the lips of one of those poor devils was unsettling. A link had been made, I felt closer to him. I was not an emotional man but I realised how much I blotted out just to survive there. His sister was safe in Birmingham and he was stuck in this hateful cauldron.

‘Do you have an address?’ I asked. He said he did but he needed to remember it. I wondered whether he was checking me out. He probably realised he had one chance and he wanted to get it right. I had to wait.

The next time I met him he had his sister’s address clear in his mind. He told me straight away. It was 7 Tixall Road, Birmingham and I memorised it immediately. I said I would try to get a letter to her. That simple promise was the beginning of a mystery that would stretch across almost seven decades.

Ernst had an impish, intelligent face. In the few months I knew him I never saw him get beaten, but it was just a matter of time for most of them. An injury or a beating would hasten his decline.

Back in the camp I thought long and hard before deciding on the best way to make contact with his sister. She might not read English yet. She might not trust me. In the end I decided to do it through my mother who would probably understand how to interpret my obscure messages.

When I put pen to paper I told my mother to write to Susanne and tell her that I was with her brother in the British camp. I gave the impression that he was an English soldier and that he had a wound to his hand and couldn’t write but other than that he was OK. It was a load of rubbish, of course. I think I even created a false regiment for him. Through my mother I told Susanne as directly as I dared that the only way to help him was to send cigarettes, as many as she could afford, to me by post. I said I would try and get them to him a little at a time. I knew it was a long shot but if my letter got through, at the very least Susanne would know Ernst was still alive. It was worth a try.

That letter was written in normal English. Usually I wrote to my mother using a childish code my sister and I had developed.

Those letters were full of references to things on our farm. I’d write about our cattle being sent to the abattoir. To get across the numbers of concentration camp prisoners I referred to the herd then say it was to the power of three or whatever it was. I even tried biblical terminology and references to Moses. It was clumsy stuff but it was the best I could do.

To underline that I was talking about the Jews I referred to Queen Victoria’s prime minister, but without using Disraeli’s name. Alternatively I would mention Epping Town where my mother knew a number of Jews lived. She needed a lot of imagination to get any of it but I learnt later she had grasped what I was trying to do.

I desperately wanted the world to know what was going on. I tried to tell her to pass the information on to the War Office but I couldn’t do it openly so I began referring to a man my parents knew about who had worked at the War Office before 1939. He lived in Ongar and I had often been in the same train to London with him when I was studying. I hinted as clearly as I dared that she should try to contact him. In the end she chose a different method and wrote two letters to the War Office. It was very general information and I don’t know how she phrased it. She wasn’t well but she tried.

I had no idea what the outside world knew about the death camps then. I had been in the army since 1939 and there wasn’t much news reaching us in the desert. In captivity there was even less. Now I think the allies knew a lot about the concentration camps by that time.

We did have some information coming in. There was a radio hidden away inside our camp, E715. I never saw it myself but I was told it was a basic crystal set. One of the lads had put it together, bartering and smuggling the parts with anyone who had contact with the outside world. It was kept well hidden. And it was usually assumed that someone had it secreted away somewhere.

Most of us heard the news from the radio second-hand through a fellow prisoner we nicknamed ‘Stimmt’, probably from a German phrase he liked to repeat, ‘das stimmt’, meaning ‘that’s true’. I think his real name was George O’Mara, a pleasant feller who would trip around the huts passing on what he knew, a sort of whispering town crier.

We saw German newspapers from time to time, particularly when we were using the latrines inside the Buna-Werke. I found a copy of one publication – probably the Völkischer Beobachter – with an edict from the SS printed in it, boasting of their plans for Britain when they were victorious. They said they would govern from Whitehall, execute all prisoners of war and allow their brave soldiers to impregnate English girls with good Aryan blood. Just right for the latrines.

It was chilling propaganda but it only served to enrage me more. Like I said before, I hadn’t joined up for King and country but youthful adventure had now become a moral conflict for me at the very time I could do little about it.

I could move around quite easily between bouts of work. If I put a pipe on my shoulder I could cross the entire building site without anyone asking me questions. We all did it. Occasionally I would come across Ernst.

Once I was in a hut in a contractor’s yard with a couple of other British chaps when he came in. We had been talking for a few minutes when we heard a noise and realised a guard was mooching around. Ernst couldn’t get out in time so he hid at the back behind some upturned tables.

The guard stepped inside, looked around and demanded to know what we were up to. I managed to keep him occupied but I was talking utter rubbish to him in broken German and in the end we went outside leaving Ernst hidden in there. It was a while before he dared to come out. It sounds dramatic now but the British prisoners pulled off tricks like that all the time. He must have been scared but he never mentioned it. The next time we managed to speak, when the Kapos were out of range, all he said was that my German was very good. It wasn’t, but I appreciated his words.

Ernst never told me about his family in any of our furtive meetings. I knew of his sister in England and that was it. The letter I had written seemed unlikely to get through and the address was probably wrong. I didn’t hold out much hope. What with Allied bombing, theft and general wartime disruption I thought it was highly unlikely any cigarettes would arrive.